Biogeography Of South Australia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Biogeography is the study of the

Biogeography is the study of the

/ref> Islands are also ideal locations because they allow scientists to look at habitats that new

Moving on to the 20th century,

Moving on to the 20th century,

Professor Paul Schultz Martin 1928–2010

'. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. January 2011: 33-46 and "a classic treatise in historical biogeography".Adler, Kraig. 2012. ''Contributions to the History of Herpetology, Vol. III''. Contributions to Herpetology Vol. 29. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. 564 pp. Martin applied several disciplines including

A Biogeography of Reptiles and Amphibians in the Gómez Farias Region, Tamaulipas, Mexico

'. Miscellaneous Publications, Museum of Zoology University of Michigan, 101: 1-102. The publication of ''

The publication of ''

Biogeography now incorporates many different fields including but not limited to physical geography, geology, botany and plant biology, zoology, general biology, and modelling. A biogeographer's main focus is on how the environment and humans affect the distribution of species as well as other manifestations of Life such as species or genetic diversity. Biogeography is being applied to biodiversity conservation and planning, projecting global environmental changes on species and biomes, projecting the spread of infectious diseases, invasive species, and for supporting planning for the establishment of crops. Technological evolving and advances have allowed for generating a whole suite of predictor variables for biogeographic analysis, including satellite imaging and processing of the Earth.The New Biogeography and its Niche in Physical Geography. D. WATTS Geography, Vol. 63, No. 4, ANNUAL CONFERENCE 1978 (November 1978), pp. 324–337 Two main types of satellite imaging that are important within modern biogeography are Global Production Efficiency Model (GLO-PEM) and Geographic Information Systems (GIS). GLO-PEM uses satellite-imaging gives "repetitive, spatially contiguous, and time specific observations of vegetation". These observations are on a global scale.Stephen D. Prince and Samuel N. Goward. "Global Primary Production: A Remote Sensing Approach" ''Journal of Biogeography'', Vol. 22, No. 4/5, Terrestrial Ecosystem Interactions with Global Change, Volume 2 (Jul. – Sep., 1995), pp. 815–835 GIS can show certain processes on the earth's surface like whale locations, sea surface temperatures, and bathymetry."Remote Sensing Data and Information." Remote Sensing Data and Information. (accessed April 28, 2014). Current scientists also use coral reefs to delve into the history of biogeography through the fossilized reefs.

Biogeography now incorporates many different fields including but not limited to physical geography, geology, botany and plant biology, zoology, general biology, and modelling. A biogeographer's main focus is on how the environment and humans affect the distribution of species as well as other manifestations of Life such as species or genetic diversity. Biogeography is being applied to biodiversity conservation and planning, projecting global environmental changes on species and biomes, projecting the spread of infectious diseases, invasive species, and for supporting planning for the establishment of crops. Technological evolving and advances have allowed for generating a whole suite of predictor variables for biogeographic analysis, including satellite imaging and processing of the Earth.The New Biogeography and its Niche in Physical Geography. D. WATTS Geography, Vol. 63, No. 4, ANNUAL CONFERENCE 1978 (November 1978), pp. 324–337 Two main types of satellite imaging that are important within modern biogeography are Global Production Efficiency Model (GLO-PEM) and Geographic Information Systems (GIS). GLO-PEM uses satellite-imaging gives "repetitive, spatially contiguous, and time specific observations of vegetation". These observations are on a global scale.Stephen D. Prince and Samuel N. Goward. "Global Primary Production: A Remote Sensing Approach" ''Journal of Biogeography'', Vol. 22, No. 4/5, Terrestrial Ecosystem Interactions with Global Change, Volume 2 (Jul. – Sep., 1995), pp. 815–835 GIS can show certain processes on the earth's surface like whale locations, sea surface temperatures, and bathymetry."Remote Sensing Data and Information." Remote Sensing Data and Information. (accessed April 28, 2014). Current scientists also use coral reefs to delve into the history of biogeography through the fossilized reefs.

Paleobiogeography goes one step further to include

Paleobiogeography goes one step further to include

Historical Biogeography of Neotropical Freshwater Fishes

'. University of California Press, Berkeley. 424 pp. * * Cox, C. B. (2001). The biogeographic regions reconsidered. ''Journal of Biogeography'', 28: 511–523

* Ebach, M.C. (2015). ''Origins of biogeography. The role of biological classification in early plant and animal geography''. Dordrecht: Springer, xiv + 173 pp.

* Lieberman, B. S. (2001). "Paleobiogeography: using fossils to study global change, plate tectonics, and evolution". Kluwer Academic, Plenum Publishing

* Lomolino, M. V., & Brown, J. H. (2004). ''Foundations of biogeography: classic papers with commentaries''. University of Chicago Press

* * * Millington, A., Blumler, M., & Schickhoff, U. (Eds.). (2011). ''The SAGE handbook of biogeography.'' Sage, London

* Nelson, G.J. (1978)

From Candolle to Croizat: Comments on the history of biogeography

''Journal of the History of Biology'', 11: 269–305. * Udvardy, M. D. F. (1975). ''A classification of the biogeographical provinces of the world''. IUCN Occasional Paper no. 18. Morges, Switzerland: IUCN

International Biogeography Society

Systematic & Evolutionary Biogeographical Society

Early Classics in Biogeography, Distribution, and Diversity Studies: To 1950

* ttp://www.wku.edu/%7Esmithch/chronob/homelist.htm Some Biogeographers, Evolutionists and Ecologists: Chrono-Biographical Sketches ; Major journals

''Journal of Biogeography'' homepage

''Global Ecology and Biogeography'' homepage

''Ecography'' homepage

{{Authority control Landscape ecology Physical oceanography Physical geography Biology terminology Environmental terminology Habitat Earth sciences

Biogeography is the study of the

Biogeography is the study of the distribution Distribution may refer to:

Mathematics

*Distribution (mathematics), generalized functions used to formulate solutions of partial differential equations

*Probability distribution, the probability of a particular value or value range of a varia ...

of species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of ...

and ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syst ...

s in geographic space and through geological time

The geologic time scale, or geological time scale, (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochronol ...

. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north po ...

, elevation

The elevation of a geographic location is its height above or below a fixed reference point, most commonly a reference geoid, a mathematical model of the Earth's sea level as an equipotential gravitational surface (see Geodetic datum § ...

, isolation and habitat area

Area is the quantity that expresses the extent of a region on the plane or on a curved surface. The area of a plane region or ''plane area'' refers to the area of a shape or planar lamina, while ''surface area'' refers to the area of an open su ...

.Brown University, "Biogeography." Accessed February 24, 2014. . Phytogeography

Phytogeography (from Greek φυτόν, ''phytón'' = "plant" and γεωγραφία, ''geographía'' = "geography" meaning also distribution) or botanical geography is the branch of biogeography that is concerned with the geographic distribution ...

is the branch of biogeography that studies the distribution of plants. Zoogeography

Zoogeography is the branch of the science of biogeography that is concerned with geographic distribution (present and past) of animal species.

As a multifaceted field of study, zoogeography incorporates methods of molecular biology, genetics, mo ...

is the branch that studies distribution of animals. Mycogeography is the branch that studies distribution of fungi, such as mushrooms

A mushroom or toadstool is the fleshy, spore-bearing fruiting body of a fungus, typically produced above ground, on soil, or on its food source. ''Toadstool'' generally denotes one poisonous to humans.

The standard for the name "mushroom" is th ...

.

Knowledge of spatial variation in the numbers and types of organisms is as vital to us today as it was to our early human ancestors

An ancestor, also known as a forefather, fore-elder or a forebear, is a parent or ( recursively) the parent of an antecedent (i.e., a grandparent, great-grandparent, great-great-grandparent and so forth). ''Ancestor'' is "any person from w ...

, as we adapt to heterogeneous but geographically predictable environments

Environment most often refers to:

__NOTOC__

* Natural environment, all living and non-living things occurring naturally

* Biophysical environment, the physical and biological factors along with their chemical interactions that affect an organism or ...

. Biogeography is an integrative field of inquiry that unites concepts and information from ecology

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overl ...

, evolutionary biology

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes (natural selection, common descent, speciation) that produced the diversity of life on Earth. It is also defined as the study of the history of life fo ...

, taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

, geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ea ...

, physical geography

Physical geography (also known as physiography) is one of the three main branches of geography. Physical geography is the branch of natural science which deals with the processes and patterns in the natural environment such as the atmosphere, ...

, palaeontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

, and climatology

Climatology (from Ancient Greek, Greek , ''klima'', "place, zone"; and , ''wiktionary:-logia, -logia'') or climate science is the scientific study of Earth's climate, typically defined as weather conditions averaged over a period of at least 30 ...

.Dansereau, Pierre. 1957. Biogeography; an ecological perspective. New York: Ronald Press Co.

Modern biogeographic research combines information and ideas from many fields, from the physiological and ecological constraints on organismal dispersal to geological

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Eart ...

and climatological

Climatology (from Greek , ''klima'', "place, zone"; and , ''-logia'') or climate science is the scientific study of Earth's climate, typically defined as weather conditions averaged over a period of at least 30 years. This modern field of study ...

phenomena operating at global spatial scales and evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary time frames.

The short-term interactions within a habitat and species of organisms describe the ecological application of biogeography. Historical biogeography describes the long-term, evolutionary periods of time for broader classifications of organisms.Cox, C Barry, and Peter Moore. Biogeography : an ecological and evolutionary approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publications, 2005. Early scientists, beginning with Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, ...

, contributed to the development of biogeography as a science.

The scientific theory of biogeography grows out of the work of Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 17696 May 1859) was a German polymath, geographer, naturalist, explorer, and proponent of Romantic philosophy and science. He was the younger brother of the Prussian minister, ...

(1769–1859), Francisco Jose de Caldas

Francisco is the Spanish and Portuguese form of the masculine given name '' Franciscus''.

Nicknames

In Spanish, people with the name Francisco are sometimes nicknamed " Paco". San Francisco de Asís was known as ''Pater Comunitatis'' (father o ...

(1768–1816), Hewett Cottrell Watson

Hewett Cottrell Watson (9 May 1804 – 27 July 1881) was a phrenologist, botanist and evolutionary theorist. He was born in Firbeck, near Rotherham, Yorkshire, and died at Thames Ditton, Surrey.

Biography

Watson was the eldest son of Holland ...

(1804–1881), Alphonse de Candolle

Alphonse Louis Pierre Pyramus (or Pyrame) de Candolle (28 October 18064 April 1893) was a French-Swiss botanist, the son of the Swiss botanist Augustin Pyramus de Candolle.

Biography

De Candolle, son of Augustin Pyramus de Candolle, first dev ...

(1806–1893), Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913), Philip Lutley Sclater

Philip Lutley Sclater (4 November 1829 – 27 June 1913) was an England, English lawyer and zoologist. In zoology, he was an expert ornithologist, and identified the main zoogeographic regions of the world. He was Secretary of the Zoological ...

(1829–1913) and other biologists and explorers.

Introduction

The patterns of species distribution across geographical areas can usually be explained through a combination of historical factors such as:speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution withi ...

, extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds ( taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed ...

, continental drift

Continental drift is the hypothesis that the Earth's continents have moved over geologic time relative to each other, thus appearing to have "drifted" across the ocean bed. The idea of continental drift has been subsumed into the science of pla ...

, and glaciation

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate bet ...

. Through observing the geographic distribution of species, we can see associated variations in sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardise ...

, river routes, habitat, and river capture

Stream capture, river capture, river piracy or stream piracy is a geomorphological phenomenon occurring when a stream or river drainage system or watershed is diverted from its own bed, and flows instead down the bed of a neighbouring stream. T ...

. Additionally, this science considers the geographic constraints of landmass

A landmass, or land mass, is a large region or area of land. The term is often used to refer to lands surrounded by an ocean or sea, such as a continent or a large island. In the field of geology, a landmass is a defined section of continen ...

areas and isolation, as well as the available ecosystem energy supplies.

Over periods of ecological

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their biophysical environment, physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community (ecology), community, ecosy ...

changes, biogeography includes the study of plant and animal species in: their past and/or present living '' refugium'' habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

; their interim living sites; and/or their survival locales. As writer David Quammen put it, "...biogeography does more than ask ''Which species?'' and ''Where''. It also asks ''Why?'' and, what is sometimes more crucial, ''Why not?''."

Modern biogeography often employs the use of Geographic Information Systems

A geographic information system (GIS) is a type of database containing geographic data (that is, descriptions of phenomena for which location is relevant), combined with software tools for managing, analyzing, and visualizing those data. In a ...

(GIS), to understand the factors affecting organism distribution, and to predict future trends in organism distribution.

Often mathematical models and GIS are employed to solve ecological problems that have a spatial aspect to them.

Biogeography is most keenly observed on the world's island

An island or isle is a piece of subcontinental land completely surrounded by water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island in a river or a lake island may be ...

s. These habitats are often much more manageable areas of study because they are more condensed than larger ecosystems on the mainland.MacArthur R.H.; Wilson E.O. 1967. ''The theory of island biogeography''/ref> Islands are also ideal locations because they allow scientists to look at habitats that new

invasive species

An invasive species otherwise known as an alien is an introduced organism that becomes overpopulated and harms its new environment. Although most introduced species are neutral or beneficial with respect to other species, invasive species adv ...

have only recently colonized and can observe how they disperse throughout the island and change it. They can then apply their understanding to similar but more complex mainland habitats. Islands are very diverse in their biome

A biome () is a biogeographical unit consisting of a biological community that has formed in response to the physical environment in which they are found and a shared regional climate. Biomes may span more than one continent. Biome is a broader ...

s, ranging from the tropical to arctic climates. This diversity in habitat allows for a wide range of species study in different parts of the world.

One scientist who recognized the importance of these geographic locations was Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, who remarked in his journal "The Zoology of Archipelagoes will be well worth examination". Two chapters in ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'' were devoted to geographical distribution.

History

18th century

The first discoveries that contributed to the development of biogeography as a science began in the mid-18th century, as Europeans explored the world and described the biodiversity of life. During the 18th century most views on the world were shaped around religion and for many natural theologists, the bible.Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a Swedish botanist, zoologist, taxonomist, and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, ...

, in the mid-18th century, initiated the ways to classify organisms through his exploration of undiscovered territories. When he noticed that species were not as perpetual as he believed, he developed the Mountain Explanation to explain the distribution of biodiversity; when Noah's ark landed on Mount Ararat and the waters receded, the animals dispersed throughout different elevations on the mountain. This showed different species in different climates proving species were not constant. Linnaeus' findings set a basis for ecological biogeography. Through his strong beliefs in Christianity, he was inspired to classify the living world, which then gave way to additional accounts of secular views on geographical distribution. He argued that the structure of an animal was very closely related to its physical surroundings. This was important to a George Louis Buffon's rival theory of distribution.

Closely after Linnaeus, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (; 7 September 1707 – 16 April 1788) was a French naturalist, mathematician, cosmologist, and encyclopédiste.

His works influenced the next two generations of naturalists, including two prominent F ...

observed shifts in climate and how species spread across the globe as a result. He was the first to see different groups of organisms in different regions of the world. Buffon saw similarities between some regions which led him to believe that at one point continents were connected and then water separated them and caused differences in species. His hypotheses were described in his work, the 36 volume '' Histoire Naturelle, générale et particulière'', in which he argued that varying geographical regions would have different forms of life. This was inspired by his observations comparing the Old and New World, as he determined distinct variations of species from the two regions. Buffon believed there was a single species creation event, and that different regions of the world were homes for varying species, which is an alternate view than that of Linnaeus. Buffon's law eventually became a principle of biogeography by explaining how similar environments were habitats for comparable types of organisms. Buffon also studied fossils which led him to believe that the earth was over tens of thousands of years old, and that humans had not lived there long in comparison to the age of the earth.

19th century

Following the period of exploration came theAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

in Europe, which attempted to explain the patterns of biodiversity observed by Buffon and Linnaeus. At the birth of the 19th century, Alexander von Humboldt, known as the "founder of plant geography", developed the concept of physique generale to demonstrate the unity of science and how species fit together. As one of the first to contribute empirical data to the science of biogeography through his travel as an explorer, he observed differences in climate and vegetation. The earth was divided into regions which he defined as tropical, temperate, and arctic and within these regions there were similar forms of vegetation. This ultimately enabled him to create the isotherm, which allowed scientists to see patterns of life within different climates. He contributed his observations to findings of botanical geography by previous scientists, and sketched this description of both the biotic and abiotic features of the earth in his book, ''Cosmos

The cosmos (, ) is another name for the Universe. Using the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos, and understandings of the reasons for its existence and significance, are studied in ...

''.

Augustin de Candolle

Augustin Pyramus (or Pyrame) de Candolle (, , ; 4 February 17789 September 1841) was a Swiss botanist. René Louiche Desfontaines launched de Candolle's botanical career by recommending him at a herbarium. Within a couple of years de Candoll ...

contributed to the field of biogeography as he observed species competition and the several differences that influenced the discovery of the diversity of life. He was a Swiss botanist and created the first Laws of Botanical Nomenclature in his work, Prodromus. He discussed plant distribution and his theories eventually had a great impact on Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

, who was inspired to consider species adaptations and evolution after learning about botanical geography. De Candolle was the first to describe the differences between the small-scale and large-scale distribution patterns of organisms around the globe.

Several additional scientists contributed new theories to further develop the concept of biogeography. Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of '' Principles of Geol ...

developed the Theory of Uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

after studying fossils. This theory explained how the world was not created by one sole catastrophic event, but instead from numerous creation events and locations.Lyell, Charles. 1830. Principles of geology, being an attempt to explain the former changes of the Earth's surface, by reference to causes now in operation. London: John Murray. Volume 1. Uniformitarianism also introduced the idea that the Earth was actually significantly older than was previously accepted. Using this knowledge, Lyell concluded that it was possible for species to go extinct. Since he noted that earth's climate changes, he realized that species distribution must also change accordingly. Lyell argued that climate changes complemented vegetation changes, thus connecting the environmental surroundings to varying species. This largely influenced Charles Darwin in his development of the theory of evolution.

Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

was a natural theologist who studied around the world, and most importantly in the Galapagos Islands. Darwin introduced the idea of natural selection, as he theorized against previously accepted ideas that species were static or unchanging. His contributions to biogeography and the theory of evolution were different from those of other explorers of his time, because he developed a mechanism to describe the ways that species changed. His influential ideas include the development of theories regarding the struggle for existence and natural selection. Darwin's theories started a biological segment to biogeography and empirical studies, which enabled future scientists to develop ideas about the geographical distribution of organisms around the globe.

Alfred Russel Wallace studied the distribution of flora and fauna in the Amazon Basin

The Amazon basin is the part of South America drained by the Amazon River and its tributaries. The Amazon drainage basin covers an area of about , or about 35.5 percent of the South American continent. It is located in the countries of Boli ...

and the Malay Archipelago

The Malay Archipelago (Indonesian/ Malay: , tgl, Kapuluang Malay) is the archipelago between mainland Indochina and Australia. It has also been called the " Malay world," " Nusantara", "East Indies", Indo-Australian Archipelago, Spices Arch ...

in the mid-19th century. His research was essential to the further development of biogeography, and he was later nicknamed the "father of Biogeography". Wallace conducted fieldwork researching the habits, breeding and migration tendencies, and feeding behavior of thousands of species. He studied butterfly and bird distributions in comparison to the presence or absence of geographical barriers. His observations led him to conclude that the number of organisms present in a community was dependent on the amount of food resources in the particular habitat. Wallace believed species were dynamic by responding to biotic and abiotic factors. He and Philip Sclater saw biogeography as a source of support for the theory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

as they used Darwin's conclusion to explain how biogeography was similar to a record of species inheritance. Key findings, such as the sharp difference in fauna either side of the Wallace Line

The Wallace Line or Wallace's Line is a faunal boundary line drawn in 1859 by the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace and named by English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley that separates the biogeographical realms of Asia and Wallacea, a tran ...

, and the sharp difference that existed between North and South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the souther ...

prior to their relatively recent faunal interchange

Biotic interchange is the process by which species from one biota invade another biota, usually due to the disappearance of a previously impassable barrier. These dispersal barriers can be physical, climatic, or biological and can include bodies o ...

, can only be understood in this light. Otherwise, the field of biogeography would be seen as a purely descriptive one.

20th and 21st century

Alfred Wegener

Alfred Lothar Wegener (; ; 1 November 1880 – November 1930) was a German climatologist, geologist, geophysicist, meteorologist, and polar researcher.

During his lifetime he was primarily known for his achievements in meteorology and ...

introduced the Theory of Continental Drift

Continental drift is the hypothesis that the Earth's continents have moved over geologic time relative to each other, thus appearing to have "drifted" across the ocean bed. The idea of continental drift has been subsumed into the science of pla ...

in 1912, though it was not widely accepted until the 1960s. This theory was revolutionary because it changed the way that everyone thought about species and their distribution around the globe. The theory explained how continents were formerly joined in one large landmass, Pangea

Pangaea or Pangea () was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 million ...

, and slowly drifted apart due to the movement of the plates below Earth's surface. The evidence for this theory is in the geological similarities between varying locations around the globe, fossil comparisons from different continents, and the jigsaw puzzle shape of the landmasses on Earth. Though Wegener did not know the mechanism of this concept of Continental Drift, this contribution to the study of biogeography was significant in the way that it shed light on the importance of environmental and geographic similarities or differences as a result of climate and other pressures on the planet. Importantly, late in his career Wegener recognised that testing his theory required measurement of continental movement rather than inference from fossils species distributions.

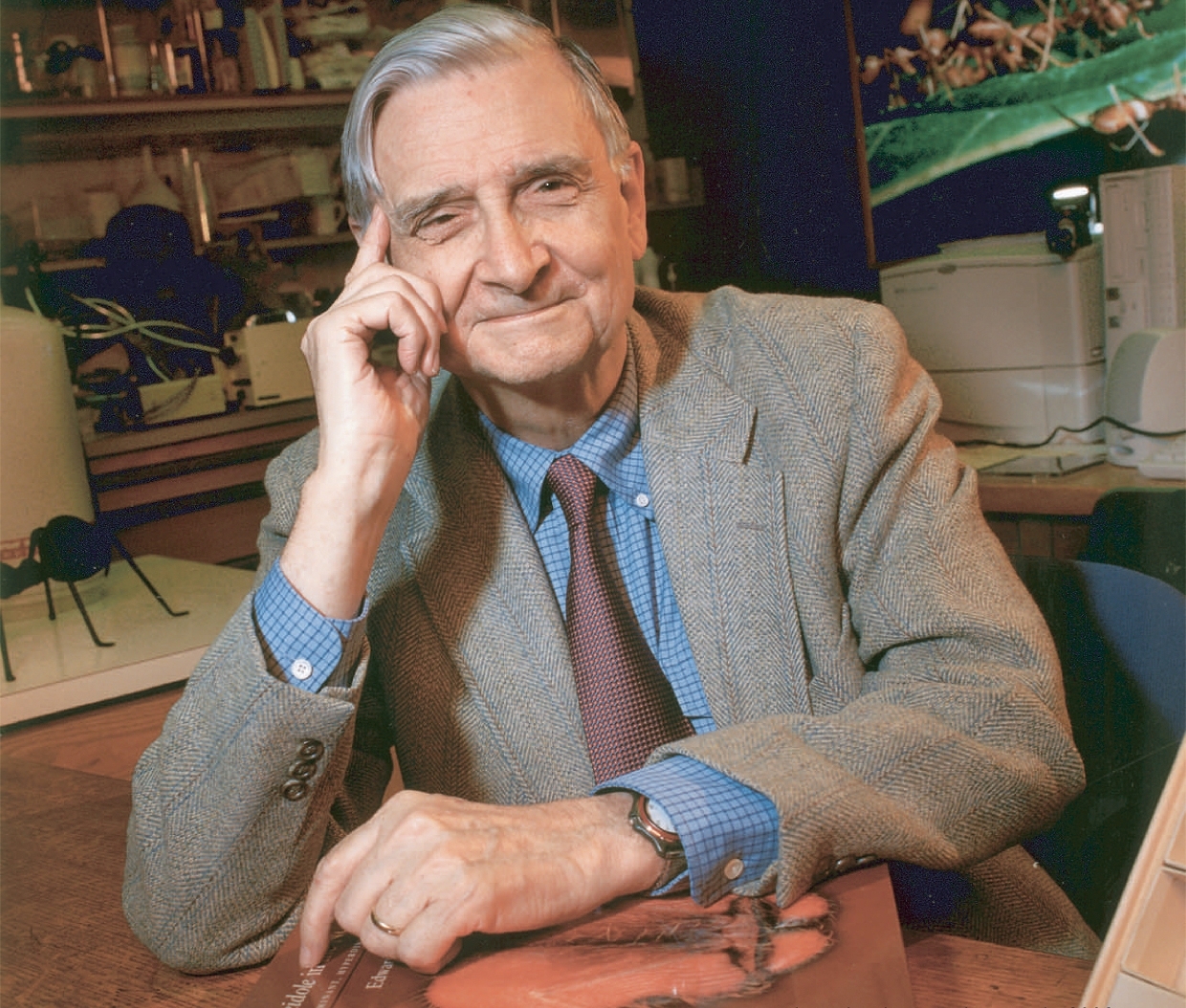

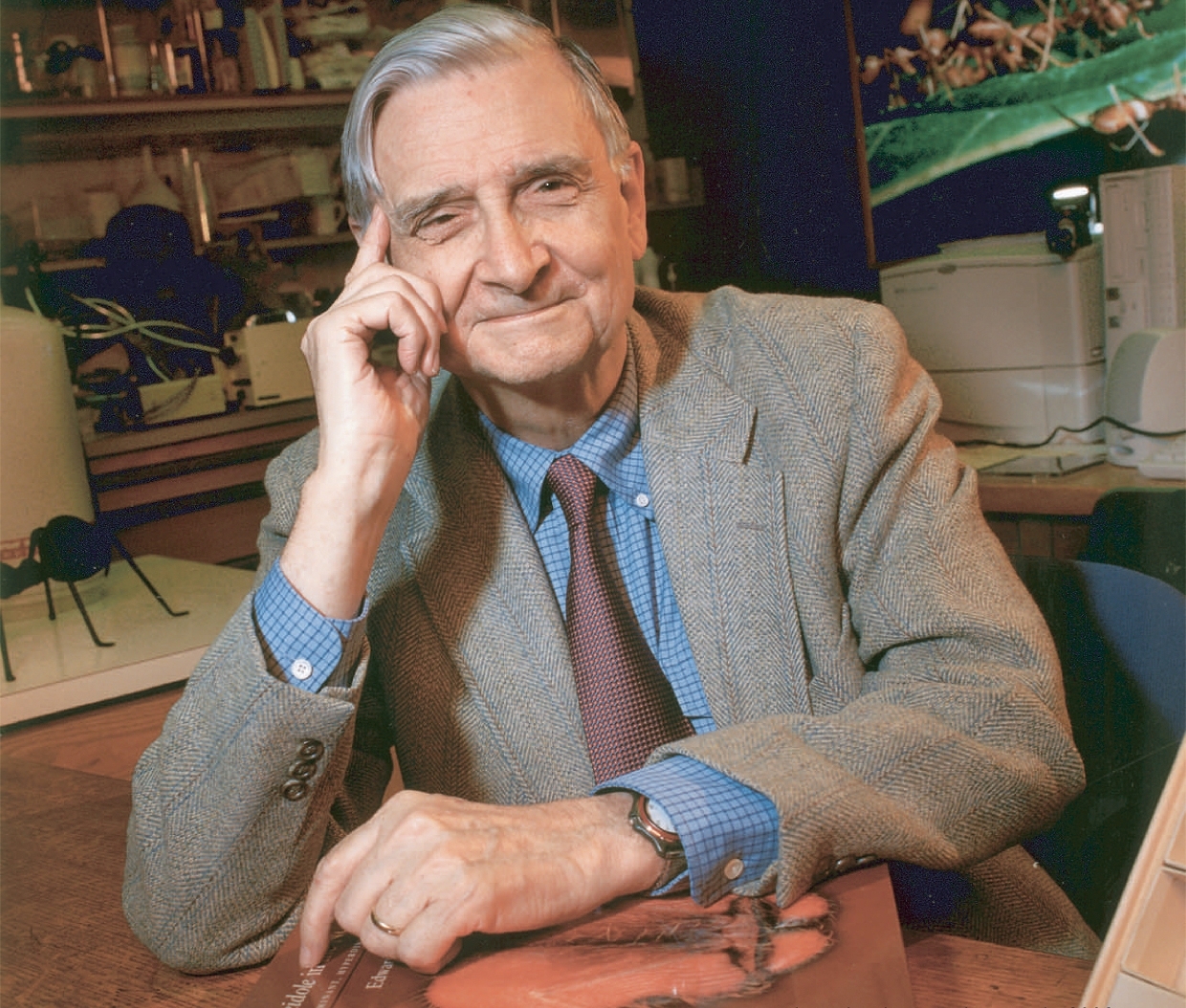

In 1958 paleontologist

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of foss ...

Paul S. Martin published ''A Biogeography of Reptiles and Amphibians in the Gómez Farias Region, Tamaulipas, Mexico'', which has been described as "ground-breaking"Steadman, David W. 2011. Professor Paul Schultz Martin 1928–2010

'. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. January 2011: 33-46 and "a classic treatise in historical biogeography".Adler, Kraig. 2012. ''Contributions to the History of Herpetology, Vol. III''. Contributions to Herpetology Vol. 29. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. 564 pp. Martin applied several disciplines including

ecology

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overl ...

, botany

Botany, also called plant science (or plant sciences), plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "bot ...

, climatology

Climatology (from Ancient Greek, Greek , ''klima'', "place, zone"; and , ''wiktionary:-logia, -logia'') or climate science is the scientific study of Earth's climate, typically defined as weather conditions averaged over a period of at least 30 ...

, geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ea ...

, and Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the '' Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed ...

dispersal routes to examine the herpetofauna of a relatively small and largely undisturbed area, but ecologically complex, situated on the threshold of temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5° to 66.5° N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout t ...

– tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

(nearctic and neotropical) regions, including semiarid lowlands at 70 meters elevation and the northernmost cloud forest

A cloud forest, also called a water forest, primas forest, or tropical montane cloud forest (TMCF), is a generally tropical or subtropical, evergreen, montane, moist forest characterized by a persistent, frequent or seasonal low-level cloud ...

in the western hemisphere at over 2200 meters.Martin, Paul S. 1958. A Biogeography of Reptiles and Amphibians in the Gómez Farias Region, Tamaulipas, Mexico

'. Miscellaneous Publications, Museum of Zoology University of Michigan, 101: 1-102.

The publication of ''

The publication of ''The Theory of Island Biogeography

''The Theory of Island Biogeography'' is a 1967 book by the ecologist Robert MacArthur and the biologist Edward O. Wilson. It is widely regarded as a seminal piece in island biogeography and ecology. The Princeton University Press reprinted the bo ...

'' by Robert MacArthur

Robert Helmer MacArthur (April 7, 1930 – November 1, 1972) was a Canadian-born American ecologist who made a major impact on many areas of community and population ecology.

Early life and education

MacArthur was born in Toronto, Ontario, ...

and E.O. Wilson in 1967 showed that the species richness of an area could be predicted in terms of such factors as habitat area, immigration rate and extinction rate. This added to the long-standing interest in island biogeography Insular biogeography or island biogeography is a field within biogeography that examines the factors that affect the species richness and diversification of isolated natural communities. The theory was originally developed to explain the pattern o ...

. The application of island biogeography theory to habitat fragments spurred the development of the fields of conservation biology

Conservation biology is the study of the conservation of nature and of Earth's biodiversity with the aim of protecting species, their habitats, and ecosystems from excessive rates of extinction and the erosion of biotic interactions. It is an ...

and landscape ecology

Landscape ecology is the science of studying and improving relationships between ecological processes in the environment and particular ecosystems. This is done within a variety of landscape scales, development spatial patterns, and organizati ...

.

Classic biogeography has been expanded by the development of molecular systematics

Molecular phylogenetics () is the branch of phylogeny that analyzes genetic, hereditary molecular differences, predominantly in DNA sequences, to gain information on an organism's evolutionary relationships. From these analyses, it is possible to ...

, creating a new discipline known as phylogeography

Phylogeography is the study of the historical processes that may be responsible for the past to present geographic distributions of genealogical lineages. This is accomplished by considering the geographic distribution of individuals in light of ge ...

. This development allowed scientists to test theories about the origin and dispersal of populations, such as island endemics. For example, while classic biogeographers were able to speculate about the origins of species in the Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands ( haw, Nā Mokupuni o Hawai‘i) are an archipelago of eight major islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the island of Hawaii in the south to northernmost ...

, phylogeography allows them to test theories of relatedness between these populations and putative source populations in Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an ...

and North America.

Biogeography continues as a point of study for many life sciences and geography students worldwide, however it may be under different broader titles within institutions such as ecology or evolutionary biology.

In recent years, one of the most important and consequential developments in biogeography has been to show how multiple organisms, including mammals like monkeys and reptiles like lizards, overcame barriers such as large oceans that many biogeographers formerly believed were impossible to cross. See also Oceanic dispersal

Oceanic dispersal is a type of biological dispersal that occurs when terrestrial organisms transfer from one land mass to another by way of a sea crossing. Island hopping is the crossing of an ocean by a series of shorter journeys between isla ...

.

Modern applications

Paleobiogeography

Paleobiogeography goes one step further to include

Paleobiogeography goes one step further to include paleogeographic

Palaeogeography (or paleogeography) is the study of historical geography, generally physical landscapes. Palaeogeography can also include the study of human or cultural environments. When the focus is specifically on landforms, the term pale ...

data and considerations of plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label= Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large t ...

. Using molecular analyses and corroborated by fossils

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

, it has been possible to demonstrate that perching birds

A passerine () is any bird of the order Passeriformes (; from Latin 'sparrow' and '-shaped'), which includes more than half of all bird species. Sometimes known as perching birds, passerines are distinguished from other orders of birds by th ...

evolved first in the region of Australia or the adjacent Antarctic

The Antarctic ( or , American English also or ; commonly ) is a polar region around Earth's South Pole, opposite the Arctic region around the North Pole. The Antarctic comprises the continent of Antarctica, the Kerguelen Plateau and o ...

(which at that time lay somewhat further north and had a temperate climate). From there, they spread to the other Gondwana

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final st ...

n continents and Southeast Asia – the part of Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pan ...

then closest to their origin of dispersal – in the late Paleogene

The Paleogene ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene; informally Lower Tertiary or Early Tertiary) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of ...

, before achieving a global distribution in the early Neogene

The Neogene ( ), informally Upper Tertiary or Late Tertiary, is a geologic period and system that spans 20.45 million years from the end of the Paleogene Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the present Quaternary Period Mya. ...

. Not knowing that at the time of dispersal, the Indian Ocean was much narrower than it is today, and that South America was closer to the Antarctic, one would be hard pressed to explain the presence of many "ancient" lineages of perching birds in Africa, as well as the mainly South American distribution of the suboscine

The Tyranni (suboscines) are a suborder of passerine birds that includes more than 1,000 species, the large majority of which are South American. It is named after the type genus '' Tyrannus''.

These have a different anatomy of the syrinx mus ...

s.

Paleobiogeography also helps constrain hypotheses on the timing of biogeographic events such as vicariance

Allopatric speciation () – also referred to as geographic speciation, vicariant speciation, or its earlier name the dumbbell model – is a mode of speciation that occurs when biological populations become geographically isolated from ...

and geodispersal In biogeography, geodispersal is the erosion of barriers to gene flow and biological dispersal (Lieberman, 2005.; Albert and Crampton, 2010.). Geodispersal differs from vicariance, which reduces gene flow through the creation of geographic barrier ...

, and provides unique information on the formation of regional biotas. For example, data from species-level phylogenetic and biogeographic studies tell us that the Amazonian fish fauna accumulated in increments over a period of tens of millions of years, principally by means of allopatric speciation, and in an arena extending over most of the area of tropical South America (Albert & Reis 2011). In other words, unlike some of the well-known insular faunas (Galapagos finches

Darwin's finches (also known as the Galápagos finches) are a group of about 18 species of passerine birds. They are well known for their remarkable diversity in beak form and function. They are often classified as the subfamily Geospizinae or ...

, Hawaiian drosophilid flies, African rift lake cichlids

Cichlids are fish from the family Cichlidae in the order Cichliformes. Cichlids were traditionally classed in a suborder, the Labroidei, along with the wrasses ( Labridae), in the order Perciformes, but molecular studies have contradicted this ...

), the species-rich Amazonian ichthyofauna is not the result of recent adaptive radiation

In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is a process in which organisms diversify rapidly from an ancestral species into a multitude of new forms, particularly when a change in the environment makes new resources available, alters biotic int ...

s.Lovejoy, N. R., S. C. Willis, & J. S. Albert (2010) Molecular signatures of Neogene

The Neogene ( ), informally Upper Tertiary or Late Tertiary, is a geologic period and system that spans 20.45 million years from the end of the Paleogene Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the present Quaternary Period Mya. ...

biogeographic events in the Amazon fish fauna. Pp. 405–417 in ''Amazonia, Landscape and Species Evolution'', 1st edition (Hoorn, C. M. and Wesselingh, F.P., eds.). London: Blackwell Publishing.

For freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does in ...

organisms, landscapes are divided naturally into discrete drainage basin

A drainage basin is an area of land where all flowing surface water converges to a single point, such as a river mouth, or flows into another body of water, such as a lake or ocean. A basin is separated from adjacent basins by a perimeter, ...

s by watersheds, episodically isolated and reunited by erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as water flow or wind) that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust, and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is di ...

al processes. In regions like the Amazon Basin

The Amazon basin is the part of South America drained by the Amazon River and its tributaries. The Amazon drainage basin covers an area of about , or about 35.5 percent of the South American continent. It is located in the countries of Boli ...

(or more generally Greater Amazonia, the Amazon basin, Orinoco

The Orinoco () is one of the longest rivers in South America at . Its drainage basin, sometimes known as the Orinoquia, covers , with 76.3 percent of it in Venezuela and the remainder in Colombia. It is the fourth largest river in the wo ...

basin, and Guianas

The Guianas, sometimes called by the Spanish loan-word ''Guayanas'' (''Las Guayanas''), is a region in north-eastern South America which includes the following three territories:

* French Guiana, an overseas department and region of France

* ...

) with an exceptionally low (flat) topographic relief, the many waterways have had a highly reticulated history over geological time

The geologic time scale, or geological time scale, (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochronol ...

. In such a context, stream capture

Stream capture, river capture, river piracy or stream piracy is a geomorphological phenomenon occurring when a stream or river drainage system or watershed is diverted from its own bed, and flows instead down the bed of a neighbouring stream. ...

is an important factor affecting the evolution and distribution of freshwater organisms. Stream capture occurs when an upstream portion of one river drainage is diverted to the downstream portion of an adjacent basin. This can happen as a result of tectonic uplift

Tectonic uplift is the geologic uplift of Earth's surface that is attributed to plate tectonics. While isostatic response is important, an increase in the mean elevation of a region can only occur in response to tectonic processes of crustal t ...

(or subsidence), natural damming created by a landslide

Landslides, also known as landslips, are several forms of mass wasting that may include a wide range of ground movements, such as rockfalls, deep-seated slope failures, mudflows, and debris flows. Landslides occur in a variety of environments, ...

, or headward or lateral erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as water flow or wind) that removes soil, rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust, and then transports it to another location where it is deposited. Erosion is di ...

of the watershed between adjacent basins.

Concepts and fields

Biogeography is a synthetic science, related togeography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, a ...

, biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditar ...

, soil science

Soil science is the study of soil as a natural resource on the surface of the Earth including soil formation, classification and mapping; physical, chemical, biological, and fertility properties of soils; and these properties in relation to ...

, geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ea ...

, climatology

Climatology (from Ancient Greek, Greek , ''klima'', "place, zone"; and , ''wiktionary:-logia, -logia'') or climate science is the scientific study of Earth's climate, typically defined as weather conditions averaged over a period of at least 30 ...

, ecology

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overl ...

and evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

.

Some fundamental concepts in biogeography include:

* allopatric speciation

Allopatric speciation () – also referred to as geographic speciation, vicariant speciation, or its earlier name the dumbbell model – is a mode of speciation that occurs when biological populations become geographically isolated from ...

– the splitting of a species by evolution of geographically isolated populations

* evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

– change in genetic composition of a population

* extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds ( taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed ...

– disappearance of a species

* dispersal – movement of populations away from their point of origin, related to migration

Migration, migratory, or migrate may refer to: Human migration

* Human migration, physical movement by humans from one region to another

** International migration, when peoples cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum l ...

* endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found els ...

areas

* geodispersal In biogeography, geodispersal is the erosion of barriers to gene flow and biological dispersal (Lieberman, 2005.; Albert and Crampton, 2010.). Geodispersal differs from vicariance, which reduces gene flow through the creation of geographic barrier ...

– the erosion of barriers to biotic

Biotics describe living or once living components of a community; for example organisms, such as animals and plants.

Biotic may refer to:

*Life, the condition of living organisms

*Biology, the study of life

* Biotic material, which is derived from ...

dispersal and gene flow, that permit range expansion and the merging of previously isolated biotas

* range

Range may refer to:

Geography

* Range (geographic), a chain of hills or mountains; a somewhat linear, complex mountainous or hilly area (cordillera, sierra)

** Mountain range, a group of mountains bordered by lowlands

* Range, a term used to i ...

and distribution Distribution may refer to:

Mathematics

*Distribution (mathematics), generalized functions used to formulate solutions of partial differential equations

*Probability distribution, the probability of a particular value or value range of a varia ...

* vicariance

Allopatric speciation () – also referred to as geographic speciation, vicariant speciation, or its earlier name the dumbbell model – is a mode of speciation that occurs when biological populations become geographically isolated from ...

– the formation of barriers to biotic dispersal and gene flow, that tend to subdivide species and biotas, leading to speciation and extinction; vicariance biogeography

Allopatric speciation () – also referred to as geographic speciation, vicariant speciation, or its earlier name the dumbbell model – is a mode of speciation that occurs when biological populations become geographically isolated from ...

is the field that studies these patterns

Comparative biogeography

The study of comparative biogeography can follow two main lines of investigation: *Systematic biogeography

Systematic may refer to:

Science

* Short for systematic error

* Systematic fault

* Systematic bias, errors that are not determined by chance but are introduced by an inaccuracy (involving either the observation or measurement process) inhere ...

, the study of biotic area relationships, their distribution, and hierarchical classification

* Evolutionary biogeography

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation te ...

, the proposal of evolutionary mechanisms responsible for organismal distributions. Possible mechanisms include widespread taxa disrupted by continental break-up or individual episodes of long-distance movement.

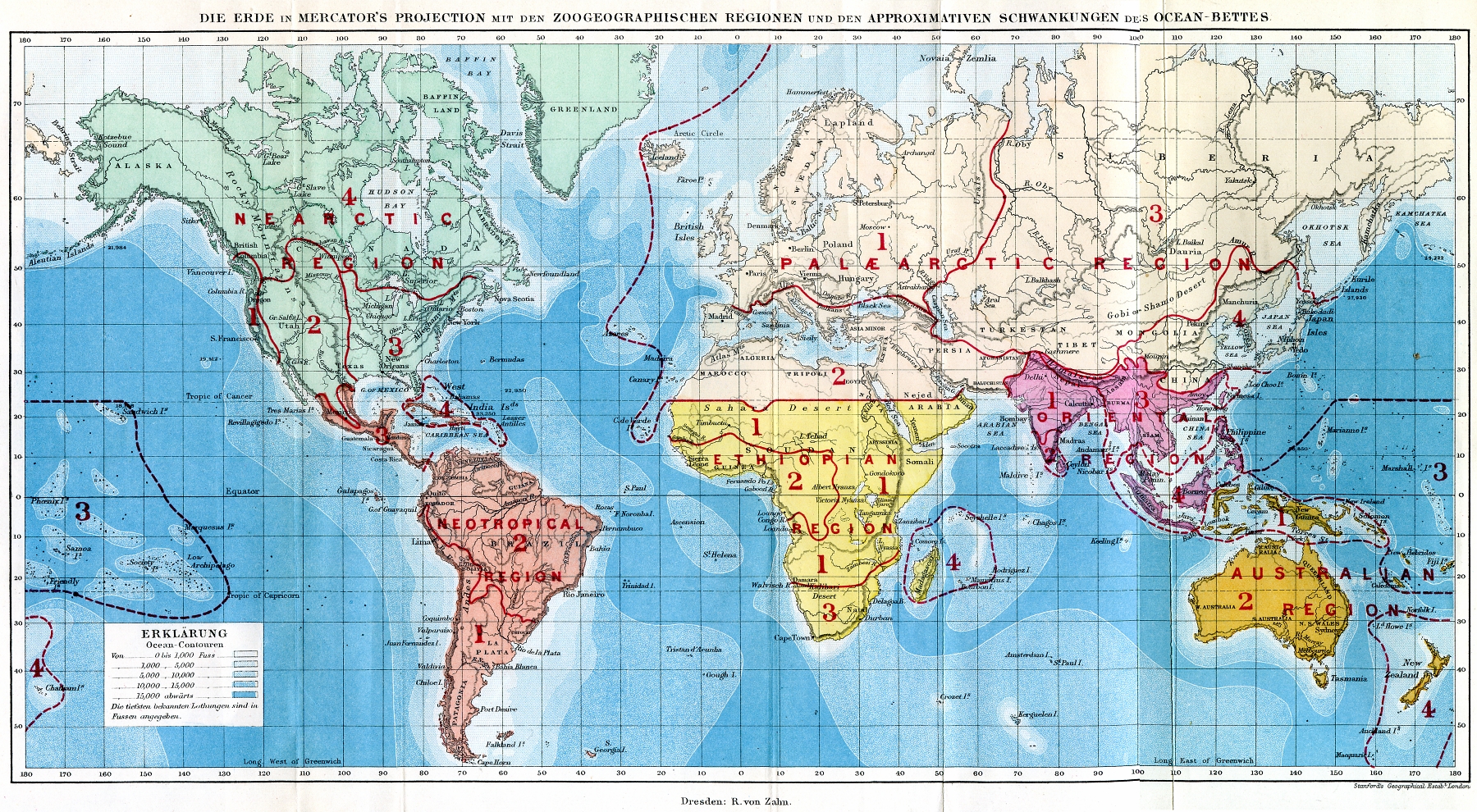

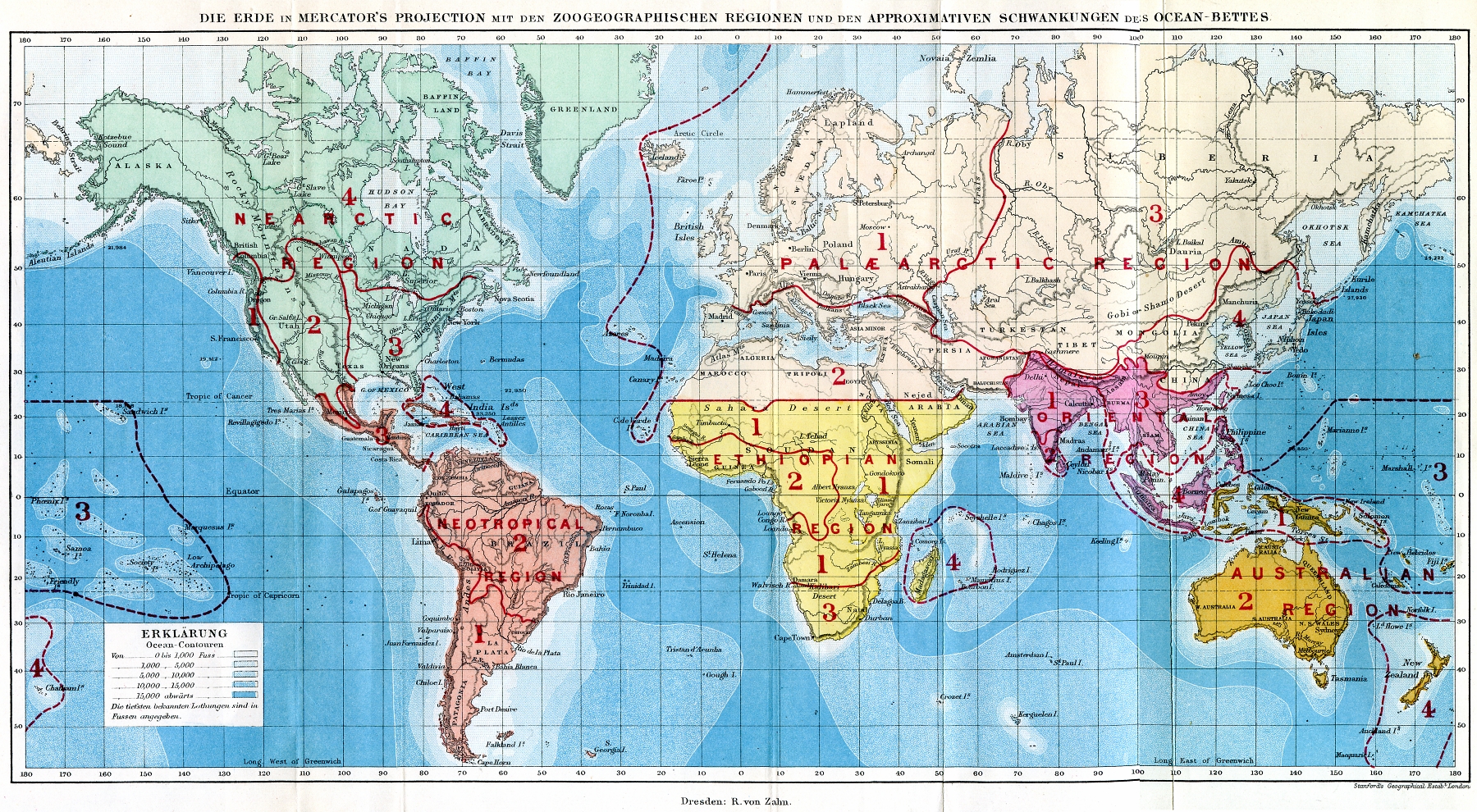

Biogeographic regionalisations

There are many types of biogeographic units used in biogeographicregionalisation

Regionalisation is the tendency to form decentralised regions.

Regionalisation or land classification can be observed in various disciplines:

*In agriculture, see Agricultural Land Classification.

*In biogeography, see Biogeography#Biogeogr ...

schemes, as there are many criteria (species composition, physiognomy

Physiognomy (from the Greek , , meaning "nature", and , meaning "judge" or "interpreter") is the practice of assessing a person's character or personality from their outer appearance—especially the face. The term can also refer to the general ...

, ecological aspects) and hierarchization schemes: biogeographic realm

A biogeographic realm or ecozone is the broadest biogeographic division of Earth's land surface, based on distributional patterns of terrestrial organisms. They are subdivided into bioregions, which are further subdivided into ecoregions.

D ...

s (ecozones), bioregion

A bioregion is an ecologically and geographically defined area that is smaller than a biogeographic realm, but larger than an ecoregion or an ecosystem, in the World Wide Fund for Nature classification scheme. There is also an attempt to use th ...

s (''sensu stricto''), ecoregion

An ecoregion (ecological region) or ecozone (ecological zone) is an ecologically and geographically defined area that is smaller than a bioregion, which in turn is smaller than a biogeographic realm. Ecoregions cover relatively large areas o ...

s, zoogeographical region

Zoogeography is the branch of the science of biogeography that is concerned with geographic distribution (present and past) of animal species.

As a multifaceted field of study, zoogeography incorporates methods of molecular biology, genetics, mo ...

s, floristic region

A phytochorion, in phytogeography, is a geographic area with a relatively uniform composition of plant species. Adjacent phytochoria do not usually have a sharp boundary, but rather a soft one, a transitional area in which many species from both re ...

s, vegetation

Vegetation is an assemblage of plant species and the ground cover they provide. It is a general term, without specific reference to particular taxa, life forms, structure, spatial extent, or any other specific botanical or geographic charact ...

types, biome

A biome () is a biogeographical unit consisting of a biological community that has formed in response to the physical environment in which they are found and a shared regional climate. Biomes may span more than one continent. Biome is a broader ...

s, etc.

The terms biogeographic unit, biogeographic area or bioregion

A bioregion is an ecologically and geographically defined area that is smaller than a biogeographic realm, but larger than an ecoregion or an ecosystem, in the World Wide Fund for Nature classification scheme. There is also an attempt to use th ...

''sensu lato'', can be used for these categories, regardless of rank.

In 2008, an International Code of Area Nomenclature The International Code of Area Nomenclature (ICAN) was proposed by a group of few biogeographers to provide a universal naming system or nomenclature for areas of endemism used in contemporary biogeography. There are other proposals to palaeobioge ...

was proposed for biogeography.Morrone, J. J. (2015). Biogeographical regionalisation of the world: a reappraisal. ''Australian Systematic Botany'' 28: 81–90, .

See also

*Allen's rule

Allen's rule is an ecogeographical rule formulated by Joel Asaph Allen in 1877, broadly stating that animals adapted to cold climates have thicker limbs and bodily appendages than animals adapted to warm climates. More specifically, it states that ...

* Bergmann's rule

Bergmann's rule is an ecogeographical rule that states that within a broadly distributed taxonomic clade, populations and species of larger size are found in colder environments, while populations and species of smaller size are found in warmer ...

* Biogeographic realm

A biogeographic realm or ecozone is the broadest biogeographic division of Earth's land surface, based on distributional patterns of terrestrial organisms. They are subdivided into bioregions, which are further subdivided into ecoregions.

D ...

* Bibliography of biology

This bibliography of biology is a list of notable works, organized by subdiscipline, on the subject of biology.

Biology is a natural science concerned with the study of life and living organisms, including their structure, function, growth, orig ...

* Biogeography-based optimization

* Center of origin

A center of origin is a geographical area where a group of organisms, either domesticated or wild, first developed its distinctive properties. They are also considered centers of diversity. Centers of origin were first identified in 1924 by Ni ...

* Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography

''Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography'', abbreviated CATMOG, is a series of 59 short publications, each focused on an individual method or theory in geography.

Background and impact

''Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography'' were p ...

* Distance decay Distance decay is a geographical term which describes the effect of distance on cultural or spatial interactions. The distance decay effect states that the interaction between two locales declines as the distance between them increases. Once the di ...

* Ecological land classification Ecological classification or ecological typology is the classification of land or water into geographical units that represent variation in one or more ecological features. Traditional approaches focus on geology, topography, biogeography, soils, v ...

* Geobiology

Geobiology is a field of scientific research that explores the interactions between the physical Earth and the biosphere. It is a relatively young field, and its borders are fluid. There is considerable overlap with the fields of ecology, evolutio ...

* Macroecology

Macroecology is the subfield of ecology that deals with the study of relationships between organisms and their environment at large spatial scales to characterise and explain statistical patterns of abundance, distribution and diversity. The term ...

* Marine ecoregions

A marine ecoregion is an ecoregion, or ecological region, of the oceans and seas identified and defined based on biogeographic characteristics.

Introduction

A more complete definition describes them as “Areas of relatively homogeneous species ...

* Max Carl Wilhelm Weber

Max Carl Wilhelm Weber van Bosse or Max Wilhelm Carl Weber (5 December 1852, in Bonn – 7 February 1937, in Eerbeek) was a German- Dutch zoologist and biogeographer.

Weber studied at the University of Bonn, then at the Humboldt University ...

* Miklos Udvardy

Miklos Dezso Ferenc Udvardy (March 23, 1919 – January 27, 1998) was a Hungarian-American biologist and university instructor. He contributed to a wide variety of disciplines, such as biogeography, evolutionary biology, ornithology, and vege ...

* Phytochorion

A phytochorion, in phytogeography, is a geographic area with a relatively uniform composition of plant species. Adjacent phytochoria do not usually have a sharp boundary, but rather a soft one, a transitional area in which many species from both r ...

– ''Plant region''

* Sky island

Sky islands are isolated mountains surrounded by radically different lowland environments. The term originally referred to those found on the Mexican Plateau, and has extended to similarly isolated high-elevation forests. The isolation has ...

* Systematic and evolutionary biogeography association

Notes and references

Further reading

* Albert, J. S., & R. E. Reis (2011).Historical Biogeography of Neotropical Freshwater Fishes

'. University of California Press, Berkeley. 424 pp. * * Cox, C. B. (2001). The biogeographic regions reconsidered. ''Journal of Biogeography'', 28: 511–523

* Ebach, M.C. (2015). ''Origins of biogeography. The role of biological classification in early plant and animal geography''. Dordrecht: Springer, xiv + 173 pp.

* Lieberman, B. S. (2001). "Paleobiogeography: using fossils to study global change, plate tectonics, and evolution". Kluwer Academic, Plenum Publishing

* Lomolino, M. V., & Brown, J. H. (2004). ''Foundations of biogeography: classic papers with commentaries''. University of Chicago Press

* * * Millington, A., Blumler, M., & Schickhoff, U. (Eds.). (2011). ''The SAGE handbook of biogeography.'' Sage, London

* Nelson, G.J. (1978)

From Candolle to Croizat: Comments on the history of biogeography

''Journal of the History of Biology'', 11: 269–305. * Udvardy, M. D. F. (1975). ''A classification of the biogeographical provinces of the world''. IUCN Occasional Paper no. 18. Morges, Switzerland: IUCN

External links

International Biogeography Society

Systematic & Evolutionary Biogeographical Society

Early Classics in Biogeography, Distribution, and Diversity Studies: To 1950

* ttp://www.wku.edu/%7Esmithch/chronob/homelist.htm Some Biogeographers, Evolutionists and Ecologists: Chrono-Biographical Sketches ; Major journals

''Journal of Biogeography'' homepage

''Global Ecology and Biogeography'' homepage

''Ecography'' homepage

{{Authority control Landscape ecology Physical oceanography Physical geography Biology terminology Environmental terminology Habitat Earth sciences