Wake Island ( mh, Ānen Kio, translation=island of the

kio flower; also known as Wake Atoll) is a

coral atoll in the western Pacific Ocean in the northeastern area of the

Micronesia subregion, east of

Guam, west of

Honolulu, southeast of

Tokyo and north of

Majuro. The island is an

unorganized,

unincorporated territory belonging to (but not a part of) the

United States that is also claimed by the

Republic of the Marshall Islands. Wake Island is one of the most isolated islands in the world. The nearest inhabited island is

Utirik Atoll in the Marshall Islands, to the southeast.

The United States took possession of Wake Island in 1899. One of 14 U.S.

insular areas, Wake Island is administered by the

United States Air Force under an agreement with the

U.S. Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the mana ...

. The center of activity on the atoll is at

Wake Island Airfield

Wake Island Airfield is a military air base located on Wake Island, which is known for the Battle of Wake Island during World War II. It is owned by the U.S. Air Force and operated by the 611th Air Support Group. The runway can be used for emerg ...

, which is primarily used as a mid-Pacific refueling stop for military aircraft and as an emergency landing area. The runway is the longest strategic runway in the Pacific islands. South of the runway is the Wake Island Launch Center, a

missile launch site. The island has no permanent inhabitants, but approximately 100 people live there at any given time.

On December 8, 1941 (within a few hours of the

attack on Pearl Harbor, Wake Island being on the opposite side of the

International Date Line

The International Date Line (IDL) is an internationally accepted demarcation on the surface of Earth, running between the South and North Poles and serving as the boundary between one calendar day and the next. It passes through the Pacific O ...

),

American forces on Wake Island were attacked by Japanese bombers. This action marked the commencement of the

Battle of Wake Island. On December 11, 1941, Wake Island was the site of the Japanese Empire's first unsuccessful amphibious attack on U.S. territory in World War II when

U.S. Marines

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the Marines, maritime land force military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary warfare, exped ...

, with some

U.S. Navy personnel and civilians on the island, repelled an attempted Japanese invasion. The island fell to overwhelming Japanese forces 12 days later; it remained occupied by Japanese forces until it was surrendered to the U.S. in September 1945 at the end of the war.

The submerged and emergent lands at Wake Island comprise a unit of the

Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument. Wake Island is one of nine insular areas that comprise the

United States Minor Outlying Islands, a statistical designation defined by the

International Organization for Standardization's

ISO 3166-1 code.

Etymology

Wake Island derives its name from British

sea captain

A sea captain, ship's captain, captain, master, or shipmaster, is a high-grade licensed mariner who holds ultimate command and responsibility of a merchant vessel.Aragon and Messner, 2001, p.3. The captain is responsible for the safe and efficie ...

Samuel Wake, who rediscovered the atoll in 1796 while in command of the ''Prince William Henry''. The name is sometimes attributed to Captain William Wake, who also is reported to have discovered the atoll from the ''Prince William Henry'' in 1792.

Geography

Wake is located two-thirds of the way from

Honolulu to

Guam. Honolulu is to the east, and Guam to the west. Midway Atoll is to the northeast. The closest land is the uninhabited

Bokak Atoll

Bokak Atoll ( Marshallese: or , ) or Taongi Atoll is an uninhabited coral atoll in the Ratak Chain of the Marshall Islands, in the North Pacific Ocean. Due to its relative isolation from the main islands in the group, Bokak's flora and fauna has ...

, away in the

Marshall Islands, to the southeast. The atoll is to the west of the

International Date Line

The International Date Line (IDL) is an internationally accepted demarcation on the surface of Earth, running between the South and North Poles and serving as the boundary between one calendar day and the next. It passes through the Pacific O ...

and in the

Wake Island Time Zone {{Short description, UTC+12:00

The Wake Island Time Zone observes standard time by adding twelve hours to Coordinated Universal Time ( UTC+12:00). The clock time in this zone is based on the mean solar time of the 180th degree meridian east of th ...

(

UTC+12), the easternmost time zone in the United States and almost one day ahead of the

50 states

The United States of America is a federal republic consisting of 50 states, a federal district (Washington, D.C., the capital city of the United States), five major territories, and various minor islands. Both the states and the United S ...

.

Although Wake is officially called an island in the singular form, it is geologically an atoll composed of three islets (Wake, Wilkes, and Peale islets) and a

reef surrounding a central lagoon.

Climate

Wake Island lies in the tropical zone, but is subject to periodic

temperate storms during the winter. Sea surface temperatures are warm all year long, reaching above in summer and autumn.

Typhoons occasionally pass over the island.

Typhoons

On October 19, 1940, an unnamed typhoon hit Wake Island with winds. This was the first recorded typhoon to hit the island since observations began in 1935.

impacted Wake on September 16, 1952, with wind speeds reaching . Olive caused major flooding, destroyed approximately 85% of its structures and caused in damage.

On September 16, 1967, at 10:40 pm local time, the eye of

Super Typhoon Sarah passed over the island. Sustained winds in the eyewall were , from the north before the eye and from the south afterward. All non-reinforced structures were demolished. There were no serious injuries, and the majority of the civilian population was evacuated after the storm.

On August 28, 2006, the United States Air Force evacuated all 188 residents and suspended all operations as Category 5

Super Typhoon Ioke headed toward Wake. By August 31 the southwestern eyewall of the storm passed over the island, with winds well over , driving a

storm surge

A storm surge, storm flood, tidal surge, or storm tide is a coastal flood or tsunami-like phenomenon of rising water commonly associated with low-pressure weather systems, such as cyclones. It is measured as the rise in water level above the n ...

and waves directly into the lagoon inflicting major damage. A U.S. Air Force assessment and repair team returned to the island in September 2006 and restored limited function to the airfield and facilities leading ultimately to a full return to normal operations.

Ecology

Wake Island is home to the Wake Atoll National Wildlife Refuge.

Native vegetation communities of Wake Island include scrub, grass, and wetlands. ''

Tournefortia argentia

''Heliotropium arboreum'' is a species of flowering plant in the borage family, Boraginaceae. It is native to tropical Asia including southern China, Madagascar, northern Australia, and most of the atolls and high islands of Micronesia and Polyn ...

'' dominated scrublands exist in association with ''

Scaevola taccada'', ''

Cordia subcordata'', and ''

Pisonia grandis''. Grassland species include ''

Dactyloctenium aegyptium

''Dactyloctenium aegyptium'', or Egyptian crowfoot grass is a member of the family Poaceae native in Africa. The plant mostly grows in heavy soils at damp sites.

Description

This grass creeps and has a straight shoot which are usually about 3 ...

'' and ''

Tribulus cistoides

''Tribulus cistoides'', also called wanglo (in Aruba), the Jamaican feverplant or puncture vine, is a species of flowering plant in the family Zygophyllaceae, which is widely distributed in tropical and subtropical regions. Habitat

Tribulus Cist ...

''. Wetlands are dominated by ''

Sesuvium portulacastrum'', and ''

Pemphis acidula'' is found near intertidal lagoons.

[

The atoll is home to multiple species of land crabs, with '']Coenobita perlatus

''Coenobita perlatus'' is a species of terrestrial hermit crab. It is known as the strawberry hermit crab because of its reddish-orange colours. It is a widespread scavenger across the Indo-Pacific, and wild-caught specimens are traded to hobby ...

'' being especially abundant.[

The atoll, with its surrounding marine waters, has been recognized as an ]Important Bird Area

An Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA) is an area identified using an internationally agreed set of criteria as being globally important for the conservation of bird populations.

IBA was developed and sites are identified by BirdLife Int ...

(IBA) by BirdLife International

BirdLife International is a global partnership of non-governmental organizations that strives to conserve birds and their habitats. BirdLife International's priorities include preventing extinction of bird species, identifying and safeguarding ...

for its sooty tern

The sooty tern (''Onychoprion fuscatus'') is a seabird in the family Laridae. It is a bird of the tropical oceans, returning to land only to breed on islands throughout the equatorial zone.

Taxonomy

The sooty tern was described by Carl Linnaeu ...

colony, with some 200,000 individual birds estimated in 1999.[

Due to human use, several ]invasive species

An invasive species otherwise known as an alien is an introduced organism that becomes overpopulated and harms its new environment. Although most introduced species are neutral or beneficial with respect to other species, invasive species ad ...

have become established on the atoll. Feral cats were introduced in the 1960s as pets and for pest control. Eradication efforts began in earnest in 1996, and were deemed successful in 2008. Two species of rat, '' Rattus exulans'' and '' Rattus tanezumi'', have colonized the island. ''R. tanezumi'' populations were successfully eradicated by 2014, however, ''R. exulans'' persists.Casuarina equisetifolia

''Casuarina equisetifolia'', common names ''Coastal She-oak'' or ''Horsetail She-oak'' (sometimes referred to as the Australian pine tree or whistling pine tree outside Australia), is a she-oak species of the genus ''Casuarina''. The native ...

'' was planted on Wake Island by boy scouts in the 1960s for use as a windbreak. It formed large mono-cultural forests that choked out native vegetation. Concerted efforts to kill the populations began in 2017. Other introduced plant species include '' Cynodon dactylon'' and ''Leucaena leucocephala

''Leucaena leucocephala'' is a small fast-growing Mimosoideae, mimosoid tree native to southern Mexico and northern Central America (Belize and Guatemala) and is now naturalized throughout the tropics including parts of Asia.

Common names inc ...

''. Non-native species of ants are also found on the atoll.[

]

History

Prehistory

The presence of the Polynesian rat on the island suggests that Wake was likely visited by Polynesian or Micronesian voyagers at an early date.

Early European contact

The first recorded discovery of Wake Island was on October 2, 1568, by Spanish explorer and navigator Álvaro de Mendaña de Neyra Álvaro (, , ) is a Spanish, Galician and Portuguese male given name and surname (see Spanish naming customs) of Visigothic origin. Some claim it may be related to the Old Norse name Alfarr, formed of the elements ''alf'' "elf" and ''arr'' "warrio ...

. In 1567, Mendaña and his crew had set off on two ships, ''Los Reyes'' and ''Todos los Santos'', from Callao

Callao () is a Peruvian seaside city and Regions of Peru, region on the Pacific Ocean in the Lima metropolitan area. Callao is Peru's chief seaport and home to its main airport, Jorge Ch√°vez International Airport. Callao municipality consists o ...

, Peru, on an expedition to search for a gold-rich land in the South Pacific as mentioned in Inca tradition. After visiting Tuvalu and the Solomon Islands, the expedition headed north and came upon Wake Island, "a low barren island, judged to be eight leagues in circumference". Since the date – October 2, 1568 – was the eve of the feast of Saint Francis of Assisi

Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, better known as Saint Francis of Assisi ( it, Francesco d'Assisi; – 3 October 1226), was a mystic Italian Catholic friar, founder of the Franciscans, and one of the most venerated figures in Christianit ...

, the captain named the island "San Francisco". The ships were in need of water and the crew was suffering from scurvy, but after circling the island it was determined that Wake was waterless and had "not a cocoanut nor a pandanus

''Pandanus'' is a genus of monocots with some 750 accepted species. They are palm-like, dioecious trees and shrubs native to the Old World tropics and subtropics. The greatest number of species are found in Madagascar and Malaysia. Common names ...

" and, in fact, "there was nothing on it but sea-birds

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted

In biology, adaptation has three related meanings. Firstly, it is the dynamic evolutionary process of natural selection that fits organisms to their environment, enhanc ...

, and sandy places covered with bushes."

In 1796, Captain Samuel Wake of the merchantman

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are u ...

''Prince William Henry'' also came upon Wake Island, naming the atoll for himself. Soon thereafter the 80-ton fur trading merchant brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the ...

''Halcyon'' arrived at Wake and Master Charles William Barkley

Charles William Barkley (1759 – 16 May 1832) was a ship captain and maritime fur trader. He was born in Hertford, England, son of Charles Barkley.[Edward Gardner Edward Gardner may refer to:

* Edward W. Gardner (1867–1932), American balkline and straight rail billiards champion

* Edward Joseph Gardner (1898–1950), U.S. Representative from Ohio

* Ed Gardner (1901–1963), American actor, director and wr ...]

, while in command of the Royal Navy's whaling ship

A whaler or whaling ship is a specialized vessel, designed or adapted for whaling: the catching or processing of whales.

Terminology

The term ''whaler'' is mostly historic. A handful of nations continue with industrial whaling, and one, Japa ...

HMS ''Bellona'', visited an island at , which he judged to be long. The island was "covered with wood, having a very green and rural appearance". This report is considered to be another sighting of Wake Island.

United States Exploring Expedition

On December 20, 1841, the United States Exploring Expedition, commanded by US Navy Lieutenant Charles Wilkes, arrived at Wake on and sent several boats to survey the island. Wilkes described the atoll as "a low coral one, of triangular form and eight feet above the surface. It has a large lagoon in the centre, which was well filled with fish of a variety of species among these were some fine mullet." He also noted that Wake had no fresh water

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does include ...

but was covered with shrubs, "the most abundant of which was the tournefortia." The expedition's naturalist, Titian Peale, noted that "the only remarkable part in the formation of this island is the enormous blocks of coral which have been thrown up by the violence of the sea." Peale collected an egg from a short-tailed albatross and added other specimens, including a Polynesian rat, to the natural history collections of the expedition. Wilkes also reported that "from appearances, the island must be at times submerged, or the sea makes a complete breach over it."

Wreck and salvage of ''Libelle''

Wake Island first received international attention with the wreck of the barque . On the night of March 4, 1866, the 650-ton iron-hulled ''Libelle'', of Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (german: Stadtgemeinde Bremen, ), is the capital of the German state Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (''Freie Hansestadt Bremen''), a two-city-state consis ...

, struck the eastern reef of Wake Island during a gale. Commanded by Captain Anton Tobias, the ship was en route from San Francisco to Hong Kong with a cargo of mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

(quicksilver). After three days of searching and digging on the island for water, the crew was able to recover a water tank from the wrecked ship. Valuable cargo was also recovered and buried on the island, including some of the 1,000 flasks of mercury, as well as coins and precious stones valued at $93,943. After three weeks with a dwindling water supply and no sign of rescue, the passengers and crew decided to leave Wake and attempt to sail to Guam (the center of the then Spanish colony of the Mariana Islands

The Mariana Islands (; also the Marianas; in Chamorro: ''Manislan Mariånas'') are a crescent-shaped archipelago comprising the summits of fifteen longitudinally oriented, mostly dormant volcanic mountains in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, betw ...

) on the two remaining boats from ''Libelle''. The 22 passengers and some of the crew sailed in the longboat under the command of First Mate Rudolf Kausch and the remainder of the crew sailed with Captain Tobias in the gig

Gig or GIG may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Gig'' (Circle Jerks album) (1992)

* ''Gig'' (Northern Pikes album) (1993)

* ''The Gig'', a 1985 film written and directed by Frank D. Gilroy

* GIG, a character in ''Hot Wheels AcceleRacers'' ...

. On April 8, 1866, after 13 days of frequent squalls, short rations and tropical sun, the longboat reached Guam. Unfortunately, the gig, commanded by the captain, was lost at sea.["The wreck of the Libelle and other early European visitors to Wake Island", ''Spennemann, D. H. R.'', Micronesian Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 4:108–123, 2005]

The Spanish governor of the Mariana Islands, Francisco Moscoso y Lara, welcomed and provided aid to the ''Libelle'' shipwreck survivors on Guam. He also ordered the schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

''Ana'', owned and commanded by his son-in-law George H. Johnston, to be dispatched with first mate Kausch to search for the missing gig and then sail on to Wake Island to confirm the shipwreck

A shipwreck is the wreckage of a ship that is located either beached on land or sunken to the bottom of a body of water. Shipwrecking may be intentional or unintentional. Angela Croome reported in January 1999 that there were approximately ...

story and recover the buried treasure. ''Ana'' departed Guam on April 10 and, after two days at Wake Island, found and salvaged the buried coins and precious stones as well as a small quantity of the quicksilver.

Wreck of ''Dashing Wave''

On July 29, 1870, the British tea clipper

A clipper was a type of mid-19th-century merchant sailing vessel, designed for speed. Clippers were generally narrow for their length, small by later 19th century standards, could carry limited bulk freight, and had a large total sail area. "C ...

''Dashing Wave'', under the command of Captain Henry Vandervord, sailed out of Foochoo, China, en route to Sydney. On August 31 "the weather was very thick, and it was blowing a heavy gale from the eastward, attended with violent squalls, and a tremendous sea." At 10:30 p.m. breakers were seen and the ship struck the reef at Wake Island. Overnight the vessel began to break up and at 10:00 a.m. the crew succeeded in launching the longboat over the leeward side

Windward () and leeward () are terms used to describe the direction of the wind. Windward is ''upwind'' from the point of reference, i.e. towards the direction from which the wind is coming; leeward is ''downwind'' from the point of reference ...

. In the chaos of the evacuation, the captain secured a chart

A chart (sometimes known as a graph) is a graphical representation for data visualization, in which "the data is represented by symbols, such as bars in a bar chart, lines in a line chart, or slices in a pie chart". A chart can represent tabu ...

and nautical instruments, but no compass. The crew loaded a case of wine, some bread and two buckets, but no drinking water. Since Wake Island appeared to have neither food nor water, the captain and his 12-man crew quickly departed, crafting a makeshift sail by attaching a blanket to an oar. With no water, each man was allotted a glass of wine per day until a heavy rain shower came on the sixth day. After 31 days of hardship, drifting westward in the longboat, they reached Kosrae (Strong's Island) in the Caroline Islands. Captain Vandervord attributed the loss of ''Dashing Wave'' to the erroneous manner in which Wake Island "is laid down in the charts. It is very low, and not easily seen even on a clear night."

American possession

With the annexation of Hawaii in 1898 and the acquisition of Guam and the Philippines resulting from the conclusion of the Spanish–American War that same year, the United States began to consider unclaimed and uninhabited Wake Island, located approximately halfway between Honolulu and Manila, as a good location for a telegraph cable station and coaling station for refueling warships of the rapidly expanding United States Navy and passing merchant and passenger steamships. On July 4, 1898, United States Army Brigadier General Francis V. Greene

Francis Vinton Greene (June 27, 1850 – May 13, 1921) was a United States Army officer who fought in the Spanish–American War. He came from the Greene family of Rhode Island, noted for its long line of participants in American military history ...

of the 2nd Brigade, Philippine Expeditionary Force

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, Rep√∫blica de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, of the Eighth Army Corps, stopped at Wake Island and raised the United States flag while en route to the Philippines on the steamship liner SS ''China''.

On January 17, 1899, under orders from President William McKinley, Commander

On January 17, 1899, under orders from President William McKinley, Commander Edward D. Taussig

Edward David Taussig (November 20, 1847 January 29, 1921) was a decorated Rear Admiral in the United States Navy. He is best remembered for being the officer to claim Wake Island after the Spanish–American War, as well as accepting the physical r ...

of landed on Wake and formally took possession of the island for the United States. After a 21-gun salute

A 21-gun salute is the most commonly recognized of the customary gun salutes that are performed by the firing of cannons or artillery as a military honor. As naval customs evolved, 21 guns came to be fired for heads of state, or in exceptiona ...

, the flag was raised and a brass plate was affixed to the flagstaff with the following inscription:

Although the proposed Wake Island route for the submarine cable would have been shorter by , the Midway Islands and not Wake Island were chosen as the location for the telegraph cable station between Honolulu and Guam. Rear Admiral Royal Bird Bradford, chief of the U.S. Navy's Bureau of Equipment, stated before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce on January 17, 1902, that "Wake Island seems at times to be swept by the sea. It is only a few feet above the level of the ocean, and if a cable station were established there very expensive works would be required; besides it has no harbor, while the Midway Islands are perfectly habitable and have a fair harbor for vessels of draught."

On June 23, 1902, , commanded by Captain Alfred Croskey and bound for Manila, spotted a ship's boat on the beach as it passed closely by Wake Island. Soon thereafter the boat was launched by Japanese on the island and sailed out to meet the transport. The Japanese told Captain Croskey that they had been put on the island by a schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

from Yokohama in Japan and that they were gathering guano

Guano (Spanish from qu, wanu) is the accumulated excrement of seabirds or bats. As a manure, guano is a highly effective fertilizer due to the high content of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, all key nutrients essential for plant growth. G ...

and drying fish. The captain suspected that they were also engaged in pearl hunting. The Japanese revealed that one of their parties needed medical attention and the captain determined from their descriptions of the symptoms that the illness was most likely beriberi. They informed Captain Croskey that they did not need any provisions or water and that they were expecting the Japanese schooner to return in a month or so. The Japanese declined an offer to be taken on the transport to Manila and were given some medical supplies for the sick man, some tobacco and a few incidentals.

After USAT ''Buford'' reached Manila, Captain Croskey reported on the presence of Japanese at Wake Island. He also learned that USAT Sheridan had a similar encounter at Wake with the Japanese. The incident was brought to the attention of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Charles Darling, who at once informed the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government responsible for the country's fore ...

and suggested that an explanation from the Japanese Government

The Government of Japan consists of legislative, executive and judiciary branches and is based on popular sovereignty. The Government runs under the framework established by the Constitution of Japan, adopted in 1947. It is a unitary state, c ...

was needed. In August 1902, Japanese Minister

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of government w ...

Takahira Kogorō provided a diplomatic note stating that the Japanese Government had "no claim whatever to make on the sovereignty of the island, but that if any subjects are found on the island the Imperial Government expects that they should be properly protected as long as they are engaged in peaceful occupations."

Wake Island was now clearly a territory of the United States, but during this period the island was only occasionally visited by passing American ships. One notable visit occurred in December 1906, when U.S. Army General John J. Pershing

General of the Armies John Joseph Pershing (September 13, 1860 – July 15, 1948), nicknamed "Black Jack", was a senior United States Army officer. He served most famously as the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) on the Wes ...

, later famous as the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces in western Europe during World War I, stopped at Wake on and hoisted a 45-star U.S. flag that was improvised out of sail

A sail is a tensile structure—which is made from fabric or other membrane materials—that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails may ...

canvas

Canvas is an extremely durable plain-woven fabric used for making sails, tents, marquees, backpacks, shelters, as a support for oil painting and for other items for which sturdiness is required, as well as in such fashion objects as handbags ...

.

Feather collecting

With limited fresh water resources, no harbor and no plans for development, Wake Island remained a remote uninhabited Pacific island in the early 20th century. It did, however, have a large seabird population that attracted Japanese feather collecting. The global demand for

With limited fresh water resources, no harbor and no plans for development, Wake Island remained a remote uninhabited Pacific island in the early 20th century. It did, however, have a large seabird population that attracted Japanese feather collecting. The global demand for feather

Feathers are epidermal growths that form a distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on both avian (bird) and some non-avian dinosaurs and other archosaurs. They are the most complex integumentary structures found in vertebrates and a premier ...

s and plumage

Plumage ( "feather") is a layer of feathers that covers a bird and the pattern, colour, and arrangement of those feathers. The pattern and colours of plumage differ between species and subspecies and may vary with age classes. Within species, ...

was driven by the millinery industry and popular European fashion designs for hats, while other demand came from pillow and bedspread manufacturers. Japanese poachers set up camps to harvest feathers on many remote islands in the Central Pacific. The feather trade was primarily focused on Laysan albatross

The Laysan albatross (''Phoebastria immutabilis'') is a large seabird that ranges across the North Pacific. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are home to 99.7% of the population. This small (for its family) gull-like albatross is the second-most ...

, black-footed albatross, masked booby, lesser frigatebird, great frigatebird

The great frigatebird (''Fregata minor'') is a large seabird in the frigatebird family. There are major nesting populations in the tropical Pacific (including the Galapagos Islands) and Indian Oceans, as well as a tiny population in the South At ...

, sooty tern

The sooty tern (''Onychoprion fuscatus'') is a seabird in the family Laridae. It is a bird of the tropical oceans, returning to land only to breed on islands throughout the equatorial zone.

Taxonomy

The sooty tern was described by Carl Linnaeu ...

and other species of tern. On February 6, 1904, Rear Admiral Robley D. Evans arrived at Wake Island on and observed Japanese collecting feathers and catching sharks for their fins. Abandoned feather poaching camps were seen by the crew of the submarine tender in 1922 and in 1923. Although feather collecting and plumage exploitation had been outlawed in the territorial United States, there is no record of any enforcement actions at Wake Island.

Japanese castaways

In January 1908, the Japanese ship ''Toyoshima Maru'', en route from Tateyama, Japan, to the South Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, encountered a heavy storm that disabled the ship and swept the captain and five of the crew overboard. The 36 remaining crew members managed to make landfall on Wake Island, where they endured five months of great hardship, disease and starvation

Starvation is a severe deficiency in caloric energy intake, below the level needed to maintain an organism's life. It is the most extreme form of malnutrition. In humans, prolonged starvation can cause permanent organ damage and eventually, dea ...

. In May 1908, the Brazilian Navy training ship ''Benjamin Constant'', while on a voyage around the world, passed by the island and spotted a tattered red distress flag. Unable to land a boat, the crew executed a challenging three-day rescue operation using rope and cable to bring on board the 20 survivors and transport them to Yokohama.

USS ''Beaver'' strategic survey

In his 1921 book ''Sea-Power in the Pacific: A Study of the American-Japanese Naval Problem'', Hector C. Bywater recommended establishing a well-defended fueling station at Wake Island to provide coal and oil for United States Navy ships engaged in future operations against Japan. On June 19, 1922, the submarine tender landed an investigating party to determine the practicality and feasibility of establishing a naval fueling station on Wake Island. Lt. Cmdr. Sherwood Picking reported that from "a strategic point of view, Wake Island could not be better located, dividing as it does with Midway, the passage from Honolulu to Guam into almost exact thirds." He observed that the boat channel

Channel, channels, channeling, etc., may refer to:

Geography

* Channel (geography), in physical geography, a landform consisting of the outline (banks) of the path of a narrow body of water.

Australia

* Channel Country, region of outback Austral ...

was choked with coral heads

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and secre ...

and that the lagoon was very shallow and not over in depth, and therefore Wake would not be able to serve as a base for surface vessels. Picking suggested clearing the channel to the lagoon for "loaded motor sailing launches" so that parties on shore could receive supplies from passing ships and he strongly recommended that Wake be used as a base for aircraft. Picking stated that "If the long heralded trans-Pacific flight ever takes place, Wake Island should certainly be occupied and used as an intermediate resting and fueling port."

Tanager Expedition

In 1923, a joint expedition by the then Bureau of the Biological Survey (in the U.S. Department of Agriculture), the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum and the United States Navy was organized to conduct a thorough biological reconnaissance of the

In 1923, a joint expedition by the then Bureau of the Biological Survey (in the U.S. Department of Agriculture), the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum and the United States Navy was organized to conduct a thorough biological reconnaissance of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands or Leeward Hawaiian Islands are a series of islands and atolls in the Hawaiian island chain located northwest (in some cases, far to the northwest) of the islands of Kauai and Niihau. Politically, they are all p ...

, then administered by the Biological Survey Bureau as the Hawaiian Islands Bird Reservation

Hawaiian may refer to:

* Native Hawaiians, the current term for the indigenous people of the Hawaiian Islands or their descendants

* Hawaii state residents, regardless of ancestry (only used outside of Hawaii)

* Hawaiian language

Historic uses

* ...

. On February 1, 1923, Secretary of Agriculture

The United States secretary of agriculture is the head of the United States Department of Agriculture. The position carries similar responsibilities to those of agriculture ministers in other governments.

The department includes several organi ...

Henry C. Wallace

Henry Cantwell "Harry" Wallace (May 11, 1866 – October 25, 1924) was an American farmer, journalist, and political activist who served as the Secretary of Agriculture from 1921 to 1924 under Republican presidents Warren G. Harding and Calvin ...

contacted Secretary of Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the sec ...

Edwin Denby to request Navy participation and recommended expanding the expedition to Johnston, Midway and Wake, all islands not administered by the Department of Agriculture. On July 27, 1923, , a World War I minesweeper, brought the Tanager Expedition to Wake Island under the leadership of ornithologist

Ornithology is a branch of zoology that concerns the "methodological study and consequent knowledge of birds with all that relates to them." Several aspects of ornithology differ from related disciplines, due partly to the high visibility and th ...

Alexander Wetmore, and a tent camp was established on the eastern end of Wilkes. From July 27 to August 5, the expedition charted the atoll, made extensive zoological and botanical observations and gathered specimens for the Bishop Museum, while the naval vessel under the command of Lt. Cmdr. Samuel Wilder King

Samuel Wilder King (December 17, 1886March 24, 1959) was the eleventh Territorial Governor of Hawaii and served from 1953 to 1957. He was appointed to the office after the term of Oren E. Long. Previously, King served in the United States House ...

conducted a sounding survey offshore. Other achievements at Wake included examinations of three abandoned Japanese feather poaching camps, scientific observations of the now extinct Wake Island rail and confirmation that Wake Island is an atoll, with a group comprising three islands with a central lagoon. Wetmore named the southwest island for Charles Wilkes, who had led the original pioneering United States Exploring Expedition to Wake in 1841. The northwest island was named for Titian Peale, the chief naturalist of that 1841 expedition.

Pan American Airways and the U.S. Navy

Juan Trippe, president of the world's then-largest airline, Pan American Airways (PAA), wanted to expand globally by offering passenger air service between the United States and China. To cross the Pacific Ocean his planes would need to island-hop, stopping at various points for refueling and maintenance. He first tried to plot the route on his globe but it showed only open sea between Midway and Guam. Next, he went to the New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress ...

to study 19th-century clipper

A clipper was a type of mid-19th-century merchant sailing vessel, designed for speed. Clippers were generally narrow for their length, small by later 19th century standards, could carry limited bulk freight, and had a large total sail area. "C ...

ship log

Log most often refers to:

* Trunk (botany), the stem and main wooden axis of a tree, called logs when cut

** Logging, cutting down trees for logs

** Firewood, logs used for fuel

** Lumber or timber, converted from wood logs

* Logarithm, in mathe ...

s and charts

A chart (sometimes known as a graph) is a graphical representation for data visualization, in which "the data is represented by symbols, such as bars in a bar chart, lines in a line chart, or slices in a pie chart". A chart can represent tabul ...

and he "discovered" a little-known coral atoll named Wake Island. To proceed with his plans at Wake and Midway, Trippe would need to be granted access to each island and approval to construct and operate facilities; however, the islands were not under the jurisdiction of any specific U.S. government entity.

Meanwhile, U.S. Navy military planners and the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government responsible for the country's fore ...

were increasingly alarmed by the Empire of Japan's expansionist attitude and growing belligerence in the Western Pacific. Following World War I, the Council of the League of Nations had granted the South Seas Mandate

The South Seas Mandate, officially the Mandate for the German Possessions in the Pacific Ocean Lying North of the Equator, was a League of Nations mandate in the "South Seas" given to the Empire of Japan by the League of Nations following Wo ...

("Nanyo") to Japan (which had joined the Allied Powers in the First World War) which included the already Japanese-held Micronesia islands north of the equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

that were part of the former colony of German New Guinea of the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

; these include the modern nation/states of Palau, Federated States of Micronesia, Northern Mariana Islands and Marshall Islands. In the 1920s and 1930s, Japan restricted access to its mandated territory

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administ ...

and began to develop harbors and airfields throughout Micronesia in defiance of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, which prohibited both the United States and Japan from expanding military fortifications in the Pacific islands. Now with Trippe's planned Pan American Airways aviation route passing through Wake and Midway, the U.S. Navy and the State Department saw an opportunity to project American air power across the Pacific under the guise of a commercial aviation enterprise. On October 3, 1934, Trippe wrote to the Secretary of the Navy, requesting a five-year lease on Wake Island with an option for four renewals. Given the potential military value of PAA's base development, on November 13, Chief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is the professional head of the United States Navy. The position is a statutory office () held by an admiral who is a military adviser and deputy to the secretary of the Navy. In a separate capacity as a memb ...

Admiral William H. Standley

William Harrison Standley (18 December 1872 – 25 October 1963) was an Admiral (United States), admiral in the United States Navy, who served as Chief of Naval Operations from 1933 to 1937. He also served as the U.S. ambassador to the Soviet ...

ordered a survey of Wake by and on December 29 President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6935, which placed Wake Island and also Johnston, Sand Island at Midway and Kingman Reef under the control of the Department of the Navy. In an attempt to disguise the Navy's military intentions, Rear Admiral Harry E. Yarnell

Admiral Harry Ervin Yarnell (18 October 1875 – 7 July 1959) was an American naval officer whose career spanned over 51 years and three wars, from the Spanish–American War through World War II.

Among his achievements was proving, in 1932 war ga ...

then designated Wake Island as a bird sanctuary.

USS ''Nitro'' arrived at Wake Island on March 8, 1935, and conducted a two-day ground, marine and aerial survey, providing the Navy with strategic observations and complete photographic coverage of the atoll. Four days later, on March 12, Secretary of the Navy Claude A. Swanson

Claude Augustus Swanson (March 31, 1862July 7, 1939) was an American lawyer and Democratic politician from Virginia. He served as U.S. Representative (1893-1906), Governor of Virginia (1906-1910), and U.S. Senator from Virginia (1910-1933), befor ...

formally granted Pan American Airways permission to construct facilities at Wake Island.

Pan American "Flying Clippers" base

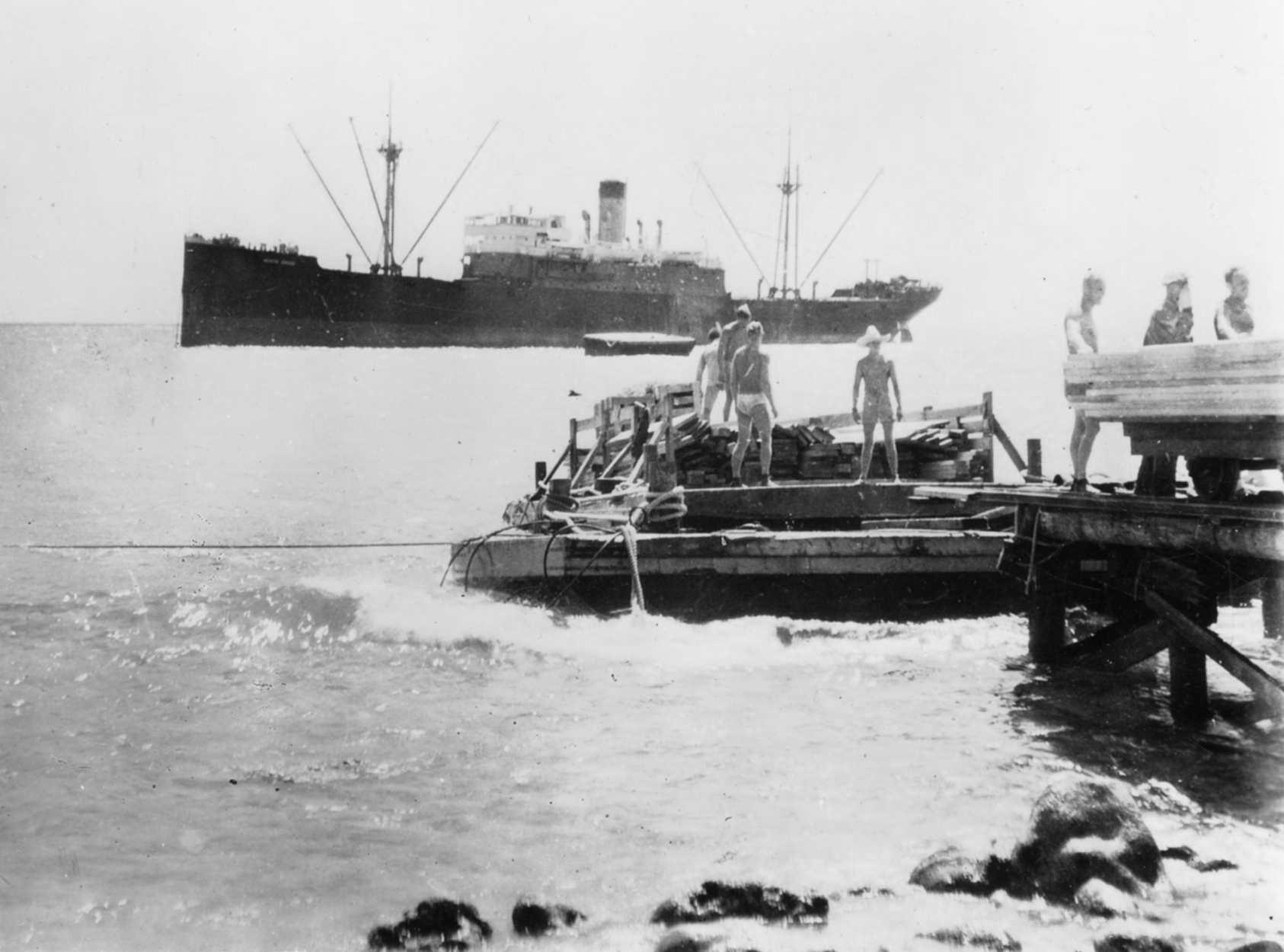

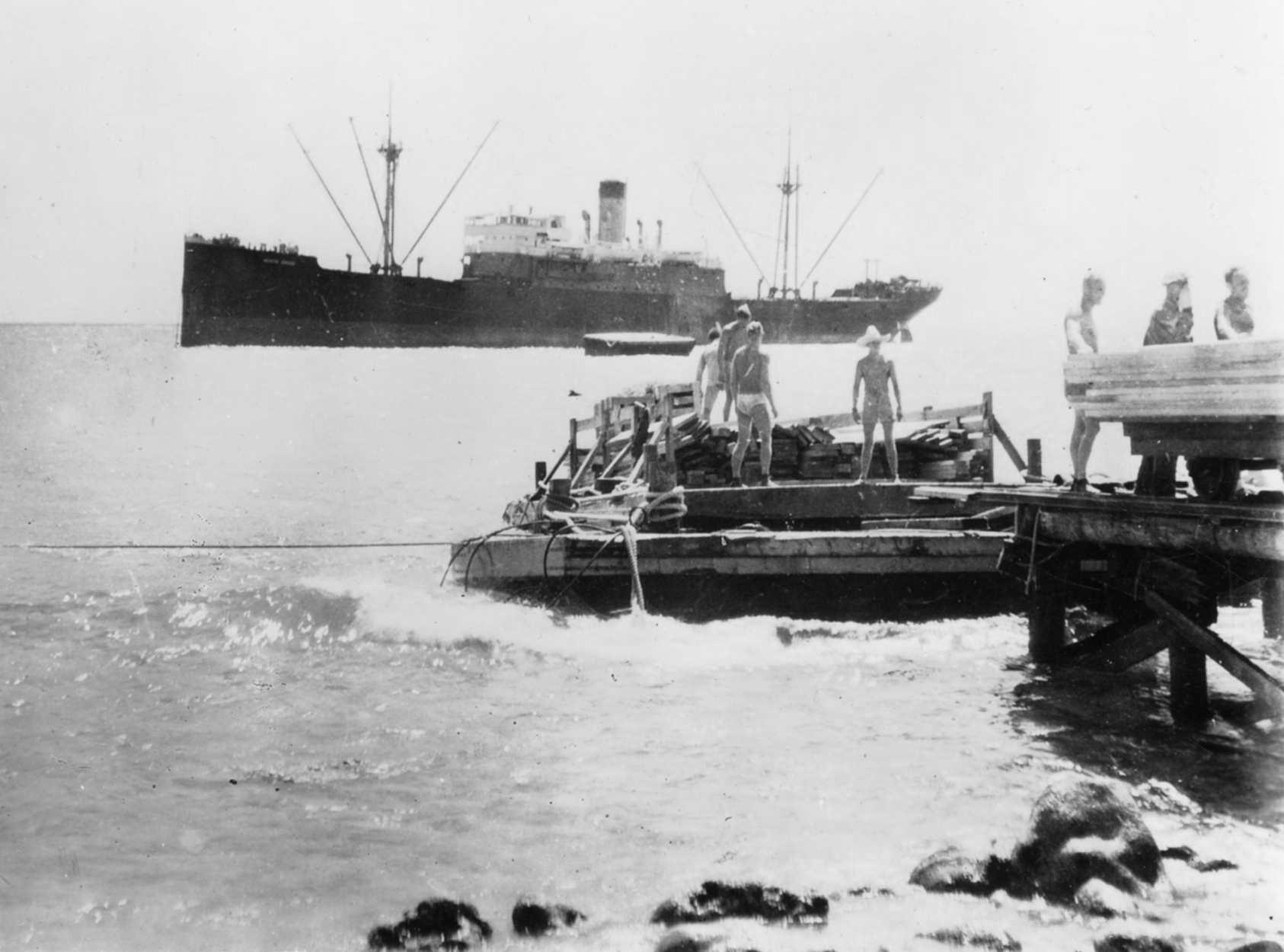

To construct bases in the Pacific, Pan American Airways (PAA) chartered the 6,700-ton freighter SS ''North Haven'', which arrived at Wake Island on May 9, 1935, with construction workers and the necessary materials and equipment to start to build Pan American facilities and to clear the lagoon for a

To construct bases in the Pacific, Pan American Airways (PAA) chartered the 6,700-ton freighter SS ''North Haven'', which arrived at Wake Island on May 9, 1935, with construction workers and the necessary materials and equipment to start to build Pan American facilities and to clear the lagoon for a flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fusela ...

landing area. The atoll's encircling coral reef prevented the ship from entering and anchoring in the shallow lagoon itself. The only suitable location for ferrying supplies and workers ashore was at nearby Wilkes Island; however, the chief engineer of the expedition, Charles R. Russell, determined that Wilkes was too low and at times flooded and that Peale Island was the best site for the Pan American facilities. To offload the ship, cargo was lightered (barged) from ship to shore, carried across Wilkes and then transferred to another barge and towed across the lagoon to Peale Island. By inspiration, someone had earlier loaded railroad track rails onto ''North Haven'', so the men built a narrow-gauge railway

A narrow-gauge railway (narrow-gauge railroad in the US) is a railway with a track gauge narrower than standard-gauge railway, standard . Most narrow-gauge railways are between and .

Since narrow-gauge railways are usually built with Minimum r ...

to make it easier to haul the supplies across Wilkes to the lagoon. The line used a flatbed car pulled by a tractor. On June 12, ''North Haven'' departed for Guam, leaving behind various PAA technicians and a construction crew.

Out in the middle of the lagoon, Bill Mullahey

William Justin Mullahey (1909 – April 15, 1981) was an American airline executive who was a long-time employee of Pan American Airways, helping the company expand its presence across the Pacific. He also played a large role in developing touri ...

, a swimmer from Columbia University, was tasked with blasting hundreds of coral heads from a long, wide, deep landing area for the flying boats.locomotive

A locomotive or engine is a rail transport vehicle that provides the Power (physics), motive power for a train. If a locomotive is capable of carrying a payload, it is usually rather referred to as a multiple unit, Motor coach (rail), motor ...

for the Wilkes Island Railroad was offloaded and the railway track was extended to run from dock to dock. Across the lagoon on Peale workers assembled the Pan American Hotel, a prefabricated structure

Prefabrication is the practice of assembling components of a structure in a factory or other manufacturing site, and transporting complete assemblies or sub-assemblies to the construction site where the structure is to be located. The term is u ...

with 48 rooms and wide porches and verandas. The hotel consisted of two wings built out from a central lobby

Lobby may refer to:

* Lobby (room), an entranceway or foyer in a building

* Lobbying, the action or the group used to influence a viewpoint to politicians

:* Lobbying in the United States, specific to the United States

* Lobby (food), a thick stew ...

with each room having a bathroom with a hot-water shower. The PAA facilities staff included a group of Chamorro Chamorro may refer to:

* Chamorro people, the indigenous people of the Mariana Islands in the Western Pacific

* Chamorro language, an Austronesian language indigenous to The Marianas

* Chamorro Time Zone, the time zone of Guam and the Northern Mari ...

men from Guam who were employed as kitchen helpers, hotel service attendants and laborers.[''Riding the Reef – A Pan American Adventure with Love'', Bert Voortmeyer, Carol Nickisher, Paladwr Press, 2005][''Diesel to Run on Wake Island Line'', Popular Science, April 1936, Vol. 128, No. 4, p. 40] The village on Peale was nicknamed "PAAville" and was the first "permanent" human settlement on Wake.

By October 1936, Pan American Airways was ready to transport

By October 1936, Pan American Airways was ready to transport passenger

A passenger (also abbreviated as pax) is a person who travels in a vehicle, but does not bear any responsibility for the tasks required for that vehicle to arrive at its destination or otherwise operate the vehicle, and is not a steward. The ...

s across the Pacific on its small fleet of three Martin M-130 "Flying Clippers". On October 11, the ''China Clipper'' landed at Wake on a press flight with ten journalists on board. A week later, on October 18, PAA President Juan Trippe and a group of VIP passengers arrived at Wake on the ''Philippine Clipper

Pan Am Flight 1104, trip no. 62100, was a Martin M-130 flying boat nicknamed the ''Philippine Clipper'' that crashed on the morning of January 21, 1943, in Northern California. The aircraft was operated by Pan American Airways and was carrying t ...

'' (NC14715). On October 25, the '' Hawaii Clipper'' (NC14714) landed at Wake with the first paying airline passengers ever to cross the Pacific. In 1937, Wake Island became a regular stop for PAA's international trans-Pacific passenger and airmail service, with two scheduled flights per week, one westbound from Midway and one eastbound from Guam.

Military buildup

On February 14, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8682 to create naval defense areas in the central Pacific territories. The proclamation established "Wake Island Naval Defensive Sea Area", which encompassed the territorial waters between the extreme high-water marks and the three-mile marine boundaries surrounding Wake. "Wake Island Naval Airspace Reservation" was also established to restrict access to the airspace over the naval defense sea area. Only U.S. government ships and aircraft were permitted to enter the naval defense areas at Wake Island unless authorized by the Secretary of the Navy.

Just earlier, in January 1941, the United States Navy began construction of a military base on the atoll. On August 19, the first permanent military garrison, elements of the U.S. Marine Corps' First Marine Defense Battalion

Marine Defense Battalions were United States Marine Corps battalions charged with coastal and air defense of advanced naval bases during World War II. They maintained large anti-ship guns, anti-aircraft guns, searchlights, and small arms to ...

, totaling 449 officers and men, were stationed on the island, commanded by Navy Cmdr.

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

Winfield Scott Cunningham

Winfield Scott Cunningham (February 16, 1900 – March 3, 1986) was the Officer in Charge, Naval Activities, Wake Island when the tiny island was attacked by the Japanese on December 8, 1941. Cunningham commanded the defense of the island again ...

. Also on the island were 68 U.S. Naval

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage of ...

personnel and about 1,221 civilian workers from the American firm Morrison-Knudsen Corp.

World War II

Battle of Wake Island

On December 8, 1941 (December 7 in Hawaii, the day of the attack on Pearl Harbor), at least 27 Japanese Mitsubishi G3M "Nell" medium bombers flown from bases on Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands attacked Wake Island, destroying eight of the 12 Grumman F4F Wildcat fighter aircraft belonging to USMC Fighter Squadron 211 on the ground. The Marine garrison's defensive emplacements were left intact by the raid, which primarily targeted the aircraft.Winfield S. Cunningham

Winfield Scott Cunningham (February 16, 1900 – March 3, 1986) was the Officer in Charge, Naval Activities, Wake Island when the tiny island was attacked by the Japanese on December 8, 1941. Cunningham commanded the defense of the island again ...

, USN was in charge of Wake Island, not Devereux.code breaker

Code Breaker is a cheat device developed by Pelican Accessories, currently available for PlayStation, PlayStation 2, Dreamcast, Game Boy Advance, and Nintendo DS. Along with competing product Action Replay, it is one of the few currently supporte ...

s. This was put together at Pearl Harbor and passed on as part of the message.

Japanese occupation and surrender

The island's Japanese garrison was composed of the IJN 65th Guard Unit (2,000 men), Japan Navy Captain

The island's Japanese garrison was composed of the IJN 65th Guard Unit (2,000 men), Japan Navy Captain Shigematsu Sakaibara

was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, the Japanese garrison commander on Wake Island during World War II, and a convicted war criminal. He was responsible for ordering the Wake Island massacre, in which 98 American civilians were murdere ...

and the IJA IJA may refer to:

* Imperial Japanese Army

* ''International Journal of Astrobiology''

* International Jugglers' Association

* ''International Journal of Audiology''

* International Juridical Association (1931–1942)

{{disambiguation ...

units which became 13th Independent Mixed Regiment (1,939 men) under command of Col. Shigeji Chikamori. Fearing an imminent invasion, the Japanese reinforced Wake Island with more formidable defenses. The American captives were ordered to build a series of bunkers and fortifications on Wake. The Japanese brought in an naval gun which is often incorrectlyGeorge H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushSince around 2000, he has been usually called George H. W. Bush, Bush Senior, Bush 41 or Bush the Elder to distinguish him from his eldest son, George W. Bush, who served as the 43rd president from 2001 to 2009; pr ...

.

After a successful American air raid by

After a successful American air raid by Task Force 14

Task may refer to:

* Task (computing), in computing, a program execution context

* Task (language instruction) refers to a certain type of activity used in language instruction

* Task (project management), an activity that needs to be accomplished ...

on October 5, 1943, Sakaibara ordered the execution of all of the 98 captured Americans who remained on the island. They were taken to the northern end of the island, blindfolded and machine-gunned.sooty tern

The sooty tern (''Onychoprion fuscatus'') is a seabird in the family Laridae. It is a bird of the tropical oceans, returning to land only to breed on islands throughout the equatorial zone.

Taxonomy

The sooty tern was described by Carl Linnaeu ...

colony had received some protection as a source of eggs, the Wake Island rail was hunted to extinction by the starving soldiers. Ultimately about three-quarters of the Japanese garrison perished, and the rest survived only by eating tern eggs, the Polynesian rats introduced by prehistoric voyagers, and what scant amount of vegetables they could grow in makeshift gardens among the coral rubble.

On September 4, 1945, the Japanese garrison surrendered to a detachment of United States Marines under the command of Brigadier General Lawson H. M. Sanderson

Lawson Harry McPhearson Sanderson (July 22, 1895 – June 11, 1973) was an aviation pioneer of the United States Marine Corps with the rank of major general. He is most noted for his effort in development of the dive bombing technique. As comman ...

.

Post-World War II military and commercial airfield

With the end of hostilities with Japan and the increase in international air travel driven in part by wartime advances in

With the end of hostilities with Japan and the increase in international air travel driven in part by wartime advances in aeronautics

Aeronautics is the science or art involved with the study, design, and manufacturing of air flight–capable machines, and the techniques of operating aircraft and rockets within the atmosphere. The British Royal Aeronautical Society identifies ...

, Wake Island became a critical mid-Pacific base for the servicing and refueling of military and commercial aircraft. The United States Navy resumed control of the island, and in October 1945 400 Seabees from the 85th Naval Construction Battalion arrived at Wake to clear the island of the effects of the war and to build basic facilities for a Naval Air Base. The base was completed in March 1946 and on September 24, regular commercial passenger service was resumed by Pan American Airways ( Pan Am). The era of the flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fusela ...

s was nearly over, so Pan Am switched to longer-range, faster and more profitable airplanes that could land on Wake's new coral runway. Other airlines that established transpacific routes through Wake included British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC), Japan Airlines, Philippine Airlines and Transocean Airlines

Transocean Air Lines was established in 1946 as ONAT (Orvis Nelson Air Transport Company) based in Oakland, California. The airline was renamed to Transocean Air Lines the same year. The Transocean name was also used in 1989 by another US-ba ...

. Due to the substantial increase in the number of commercial flights, on July 1, 1947, the Navy transferred administration, operations and maintenance of the facilities at Wake to the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA). In 1949, the CAA upgraded the runway by paving over the coral surface and extending its length to 7,000 feet.

Korean War

In June 1950, the Korean War began with the United States leading United Nations forces against a North Korean invasion of South Korea. In July, the

In June 1950, the Korean War began with the United States leading United Nations forces against a North Korean invasion of South Korea. In July, the Korean Airlift

The Korean Airlift was a military operation during the Korean War by the United States Air Force and other air forces participating in the United Nations action. Begun in 1950 under the command of Major General William H. Tunner, it provided air ...

was started and the Military Air Transport Service

The Military Air Transport Service (MATS) is an inactive Department of Defense Unified Command. Activated on 1 June 1948, MATS was a consolidation of the United States Navy's Naval Air Transport Service (NATS) and the United States Air Force's ...

(MATS) used the airfield and facilities at Wake as a key mid-Pacific refueling stop for its mission of transporting men and supplies to the Korean front. By September, 120 military aircraft were landing at Wake per day. On October 15, U.S. President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

and General MacArthur met at the Wake Island Conference

On October 15, 1950, U.S. President Harry S. Truman and General Douglas MacArthur met on Wake Island to confer about the progress of the Korean War. Truman decided he would meet MacArthur at Wake Island, "so that General MacArthur would not have ...

to discuss progress and war strategy for the Korean Peninsula. They chose to meet at Wake Island because of its close proximity to Korea so that MacArthur would not have to be away from the troops in the field for long.

Missile Impact Location System

From 1958 through 1960 the United States installed the Missile Impact Location System The Missile Impact Location System or Missile Impact Locating System (MILS)Both full names are found in references. is an ocean acoustic system designed to locate the impact position of test missile nose cones at the ocean's surface and then the pos ...

(MILS) in the Navy managed Pacific Missile Range, later the Air Force managed Western Range, to localize the splash downs of test missile nose cones. MILS was developed and installed by the same entities that had completed the first phase of the Atlantic and U.S. West Coast SOSUS systems. A MILS installation, consisting of both a target array for precision location and a broad ocean area system for good positions outside the target area, was installed at Wake as part of the system supporting Intercontinental Ballistic Missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

(ICBM) tests. Other Pacific MILS shore terminals were at the Marine Corps Air Station Kaneohe Bay

Marine Corps Air Station Kaneohe Bay or MCAS Kaneohe Bay is a United States Marine Corps (USMC) airfield located within the Marine Corps Base Hawaii complex, formerly known as Marine Corps Air Facility (MCAF) Kaneohe Bay or Naval Air Station (NAS) ...

supporting Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile (IRBM) tests with impact areas northeast of Hawaii and the other ICBM test support systems at Midway Island

Midway Atoll (colloquial: Midway Islands; haw, Kauihelani, translation=the backbone of heaven; haw, Pihemanu, translation=the loud din of birds, label=none) is a atoll in the North Pacific Ocean. Midway Atoll is an insular area of the Unit ...

and Eniwetok.

Tanker shipwreck and oil spill

On September 6, 1967, Standard Oil of California Standard may refer to:

Symbols

* Colours, standards and guidons, kinds of military signs

* Standard (emblem), a type of a large symbol or emblem used for identification

Norms, conventions or requirements

* Standard (metrology), an object th ...

's 18,000-ton tanker

Tanker may refer to:

Transportation

* Tanker, a tank crewman (US)

* Tanker (ship), a ship designed to carry bulk liquids

** Chemical tanker, a type of tanker designed to transport chemicals in bulk

** Oil tanker, also known as a petroleum ta ...

SS ''R.C. Stoner'' was driven onto the reef at Wake Island by a strong southwesterly wind after the ship failed to moor

Moor or Moors may refer to:

Nature and ecology

* Moorland, a habitat characterized by low-growing vegetation and acidic soils.

Ethnic and religious groups

* Moors, Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, Iberian Peninsula, Sicily, and Malta during ...

to the two buoy

A buoy () is a floating device that can have many purposes. It can be anchored (stationary) or allowed to drift with ocean currents.

Types

Navigational buoys

* Race course marker buoys are used for buoy racing, the most prevalent form of yac ...

s near the harbor entrance. An estimated six million gallons of refined fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil, marine fuel oil (MFO), bun ...

– including 5.7 million gallons of aviation fuel

Aviation fuels are petroleum-based fuels, or petroleum and synthetic fuel blends, used to power aircraft. They have more stringent requirements than fuels used for ground use, such as heating and road transport, and contain additives to enhanc ...

, 168,000 gallons of diesel oil

Diesel fuel , also called diesel oil, is any liquid fuel specifically designed for use in a diesel engine, a type of internal combustion engine in which fuel ignition takes place without a spark as a result of compression of the inlet air and t ...

and 138,600 gallons of bunker C fuel – spilled into the small boat harbor and along the southwestern coast of Wake Island to Peacock Point. Large numbers of fish were killed by the oil spill, and personnel from the FAA and crewmen from the ship cleared the area closest to the spill of dead fish.salvage

Salvage may refer to:

* Marine salvage, the process of rescuing a ship, its cargo and sometimes the crew from peril

* Water salvage, rescuing people from floods.

* Salvage tug, a type of tugboat used to rescue or salvage ships which are in dis ...

team Harbor Clearance Unit Two and Pacific Fleet Salvage Officer Cmdr. John B. Orem flew to Wake to assess the situation, and by September 13 the Navy tugs and , salvage ships and , tanker , and , arrived from Honolulu, Guam and Subic Bay in the Philippines, to assist in the cleanup and removal of the vessel. At the boat harbor the salvage team pumped and skimmed oil, which they burned each evening in nearby pits. Recovery by the Navy salvage team of the ''R.C. Stoner'' and its remaining cargo, however, was hampered by strong winds and heavy seas.knots

A knot is a fastening in rope or interwoven lines.

Knot may also refer to:

Places

* Knot, Nancowry, a village in India

Archaeology

* Knot of Isis (tyet), symbol of welfare/life.

* Minoan snake goddess figurines#Sacral knot

Arts, entertainme ...

, causing widespread damage. The intensity of the storm had the beneficial effect of greatly accelerating the cleanup effort by clearing the harbor and scouring the coast. Oil did remain, however, embedded in the reef's flat crevices and impregnated in the coral. The storm also had broken the wrecked vessel into three sections and, although delayed by rough seas and harassment by blacktip reef shark

The blacktip reef shark (''Carcharhinus melanopterus'') is a species of requiem shark, in the family Carcharhinidae, which can be easily identified by the prominent black tips on its fins (especially on the first dorsal fin and its caudal fin). ...

s, the salvage team used explosives to flatten and sink the remaining portions of the ship that were still above water.

U.S. Air Force assumes control

In the early 1970s, higher-efficiency jet aircraft with longer-range capabilities lessened the use of Wake Island Airfield as a refueling stop, and the number of commercial flights landing at Wake declined sharply. Pan Am had replaced many of its Boeing 707

The Boeing 707 is an American, long-range, narrow-body airliner, the first jetliner developed and produced by Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

Developed from the Boeing 367-80 prototype first flown in 1954, the initial first flew on December 20, ...

s with more efficient 747 747 may refer to:

* 747 (number), a number

* AD 747, a year of the Julian calendar

* 747 BC, a year in the 8th century BC

* Boeing 747, a large commercial jet airliner

Music and film

* 747s (band), an indie band

* ''747'' (album), by country musi ...

s, thus eliminating the need to continue weekly stops at Wake. Other airlines began to eliminate their scheduled flights into Wake. In June 1972 the last scheduled Pan Am passenger flight landed at Wake, and in July Pan Am's last cargo flight departed the island, marking the end of the heyday of Wake Island's commercial aviation history. During this same time period the U.S. military had transitioned to longer-range C-5A

The Lockheed C-5 Galaxy is a large military transport aircraft designed and built by Lockheed, and now maintained and upgraded by its successor, Lockheed Martin. It provides the United States Air Force (USAF) with a heavy intercontinental-ran ...

and C-141 aircraft, leaving the C-130 as the only aircraft that would continue to regularly use the island's airfield. The steady decrease in air traffic control activities at Wake Island was apparent and was expected to continue.

On June 24, 1972, responsibility for the civil administration of Wake Island was transferred from the FAA to the United States Air Force under an agreement between the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of the Air Force. In July, the FAA turned over administration of the island to the Military Airlift Command (MAC), although legal ownership stayed with the Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the mana ...

, and the FAA continued to maintain the air navigation facilities and provide air traffic control services. On December 27, the Chief of Staff of the Air Force (CSAF) General John D. Ryan John or Johnny Ryan may refer to:

Business

*John Ryan (businessman) (born 1950), pioneer of cosmetic surgery and chairman of Doncaster Rovers

*John D. Ryan (industrialist) (1864–1933), American copper mining magnate

*John Ryan (printer) (1761‚Ä ...

directed MAC to phase out en-route support activity at Wake Island effective June 30, 1973. On July 1, 1973, all FAA activities ended and the U.S. Air Force under Pacific Air Forces (PACAF), Detachment 4, 15th Air Base Wing

15 (fifteen) is the natural number following 14 and preceding 16.

Mathematics

15 is:

* A composite number, and the sixth semiprime; its proper divisors being , and .

* A deficient number, a smooth number, a lucky number, a pernicious num ...

assumed control of Wake Island.

In 1973, Wake Island was selected as a launch site for the testing of defensive systems against intercontinental ballistic missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

s under the U.S. Army's ''Project Have Mill''. Air Force personnel on Wake and the Air Force Systems Command

The Air Force Systems Command (AFSC) is an inactive United States Air Force Major Command. It was established in April 1951, being split off from Air Materiel Command. The mission of AFSC was Research and Development for new weapons systems.

Ove ...

(AFSC) Space and Missile Systems Organization

Space Systems Command (SSC) is the United States Space Force's space development, acquisition, launch, and logistics field command. It is headquartered at Los Angeles Air Force Base, California and manages the United States' space launch ...

(SAMSO) provided support to the Army's Advanced Ballistic Missile Defense Agency (ABMDA). A missile launch complex was activated on Wake and, from February 13 to June 22, 1974, seven Athena H missiles were launched from the island to the Roi-Namur Test Range at Kwajalein Atoll

Kwajalein Atoll (; Marshallese: ) is part of the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI). The southernmost and largest island in the atoll is named Kwajalein Island, which its majority English-speaking residents (about 1,000 mostly U.S. civilia ...

.

Vietnam War refugees and ''Operation New Life''

In the spring of 1975, the population of Wake Island consisted of 251 military, government and civilian contract personnel, whose primary mission was to maintain the airfield as a Mid-Pacific emergency runway. With the imminent fall of Saigon to North Vietnamese forces, President

In the spring of 1975, the population of Wake Island consisted of 251 military, government and civilian contract personnel, whose primary mission was to maintain the airfield as a Mid-Pacific emergency runway. With the imminent fall of Saigon to North Vietnamese forces, President Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

ordered American forces to support '' Operation New Life'', the evacuation of refugee

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution. s from Vietnam. The original plans included the Philippines' Subic Bay and Guam as refugee processing centers, but due to the high number of Vietnamese seeking evacuation, Wake Island was selected as an additional location.United States Air Force Security Police

The United States Air Force Security Forces (SF) are the ground combat force and military police service of the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force. USAF Security Forces (SF) were formerly known as Military Police (MP), Air Police (AP), and Se ...

team, processing agents from the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service and various other administrative and support personnel were also on Wake. Potable water

Drinking water is water that is used in drink or food preparation; potable water is water that is safe to be used as drinking water. The amount of drinking water required to maintain good health varies, and depends on physical activity level, ag ...

, food, medical supplies, clothing and other supplies were shipped in.

Bikini Islanders resettlement

On March 20, 1978, Undersecretary James A. Joseph

James A. Joseph (March 12, 1935 – February 17, 2023) was an American diplomat.

Early life

Joseph was born in Plaisance, Louisiana. He earned his bachelor's degree in political science and social studies from Southern University, and master's ...

of the U.S. Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the mana ...

reported that radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or through a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'', such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visi ...

levels from '' Operation Crossroads'' and other atomic tests conducted in the 1940s and 1950s on Bikini Atoll were still too high and those island natives that returned to Bikini would once again have to be relocated. In September 1979 a delegation from the Bikini/ Kili Council came to Wake Island to assess the island's potential as a possible resettlement site. The delegation also traveled to Hawaii (Molokai

Molokai , or Molokai (), is the fifth most populated of the eight major islands that make up the Hawaiian Islands, Hawaiian Islands archipelago in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. It is 38 by 10 miles (61 by 16 km) at its greatest length an ...

and Hilo

Hilo () is a census-designated place (CDP) and the largest settlement in Hawaii County, Hawaii, Hawaii County, Hawaii, United States, which encompasses the Hawaii (island), Island of Hawaii. The population was 44,186 according to the 2020 United ...

), Palmyra Atoll and various atolls in the Marshall Islands including Mili, Knox, Jaluit

Jaluit Atoll ( Marshallese: , , or , ) is a large coral atoll of 91 islands in the Pacific Ocean and forms a legislative district of the Ralik Chain of the Marshall Islands. Its total land area is , and it encloses a lagoon with an area of . Most ...

, Ailinglaplap

Ailinglaplap or Ailinglapalap ( Marshallese: , ) is a coral atoll of 56 islands in the Pacific Ocean, and forms a legislative district of the Ralik Chain in the Marshall Islands. It is located northwest of Jaluit Atoll. Its total land area is on ...

, Erikub

Erikub Atoll ( Marshallese: , ) is an uninhabited coral atoll of fourteen islands in the Pacific Ocean, located in the Ratak Chain of the Marshall Islands. Its total land area is only , but it encloses a lagoon with an area of . It is located sli ...