The Nigerian Civil War (6 July 1967 – 15 January 1970), also known as the Nigerian–Biafran War or the Biafran War, was a

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

fought between

Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

and the

Republic of Biafra

Biafra, officially the Republic of Biafra, was a partially recognised secessionist state in West Africa that declared independence from Nigeria and existed from 1967 until 1970. Its territory consisted of the predominantly Igbo-populated form ...

, a

secessionist

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics lea ...

state which had declared its

independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

from Nigeria in 1967. Nigeria was led by General

Yakubu Gowon

Yakubu Dan-Yumma 'Jack' Gowon (born 19 October 1934) is a retired Nigerian Army general and military leader. As Head of State of Nigeria, Gowon presided over a controversial Nigerian Civil War and delivered the famous "no victor, no vanquish ...

, while

Biafra

Biafra, officially the Republic of Biafra, was a partially recognised secessionist state in West Africa that declared independence from Nigeria and existed from 1967 until 1970. Its territory consisted of the predominantly Igbo-populated form ...

was led by

Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

Chukwuemeka "Emeka" Odumegwu Ojukwu.

Biafra

Biafra, officially the Republic of Biafra, was a partially recognised secessionist state in West Africa that declared independence from Nigeria and existed from 1967 until 1970. Its territory consisted of the predominantly Igbo-populated form ...

represented the nationalist aspirations of the

Igbo ethnic group, whose leadership felt they could no longer coexist with the

federal government

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-governin ...

dominated by the interests of the Muslim

Hausa-Fulanis of Northern Nigeria. The conflict resulted from political, economic, ethnic, cultural and religious tensions which preceded the United Kingdom's formal

decolonization

Decolonization or decolonisation is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. Some scholars of decolonization focus especially on separatism, in ...

of

Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

from 1960 to 1963. Immediate causes of the war in 1966 included

a military coup,

a counter-coup, and

anti-Igbo pogroms in

Northern Nigeria

Northern Nigeria was an autonomous division within Nigeria, distinctly different from the southern part of the country, with independent customs, foreign relations and security structures. In 1962 it acquired the territory of the United Kingd ...

.

Control over the lucrative

oil production

Petroleum is a fossil fuel that can be drawn from beneath the earth's surface. Reservoirs of petroleum was formed through the mixture of plants, algae, and sediments in shallow seas under high pressure. Petroleum is mostly recovered from oil dri ...

in the

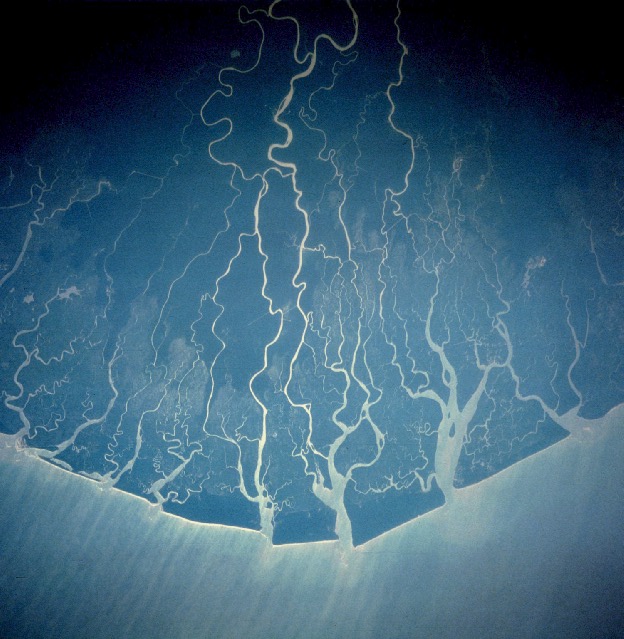

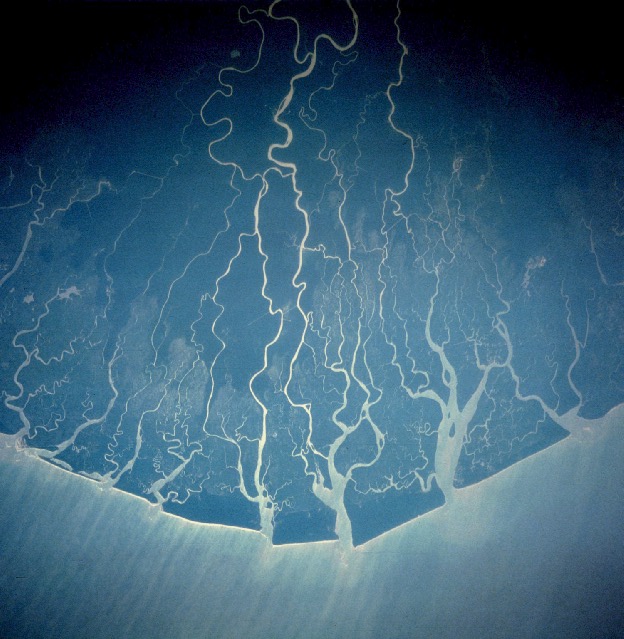

Niger Delta

The Niger Delta is the delta of the Niger River sitting directly on the Gulf of Guinea on the Atlantic Ocean in Nigeria. It is located within nine coastal southern Nigerian states, which include: all six states from the South South geopolitical ...

also played a vital

strategic

Strategy (from Greek στρατηγία ''stratēgia'', "art of troop leader; office of general, command, generalship") is a general plan to achieve one or more long-term or overall goals under conditions of uncertainty. In the sense of the "art ...

role.

Within a year, the Federal Government troops surrounded

Biafra

Biafra, officially the Republic of Biafra, was a partially recognised secessionist state in West Africa that declared independence from Nigeria and existed from 1967 until 1970. Its territory consisted of the predominantly Igbo-populated form ...

, captured coastal oil facilities and the city of

Port Harcourt. A

blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

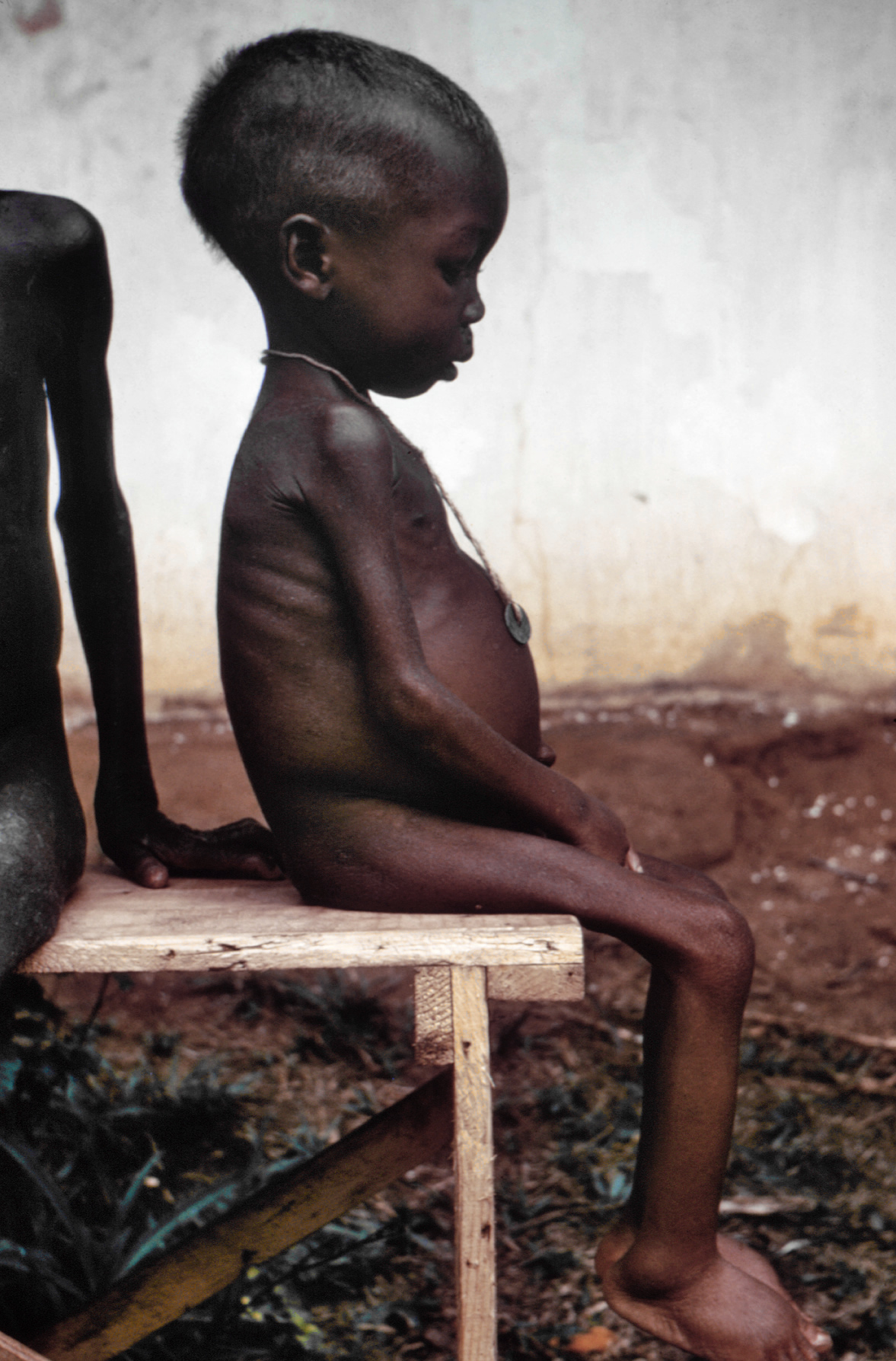

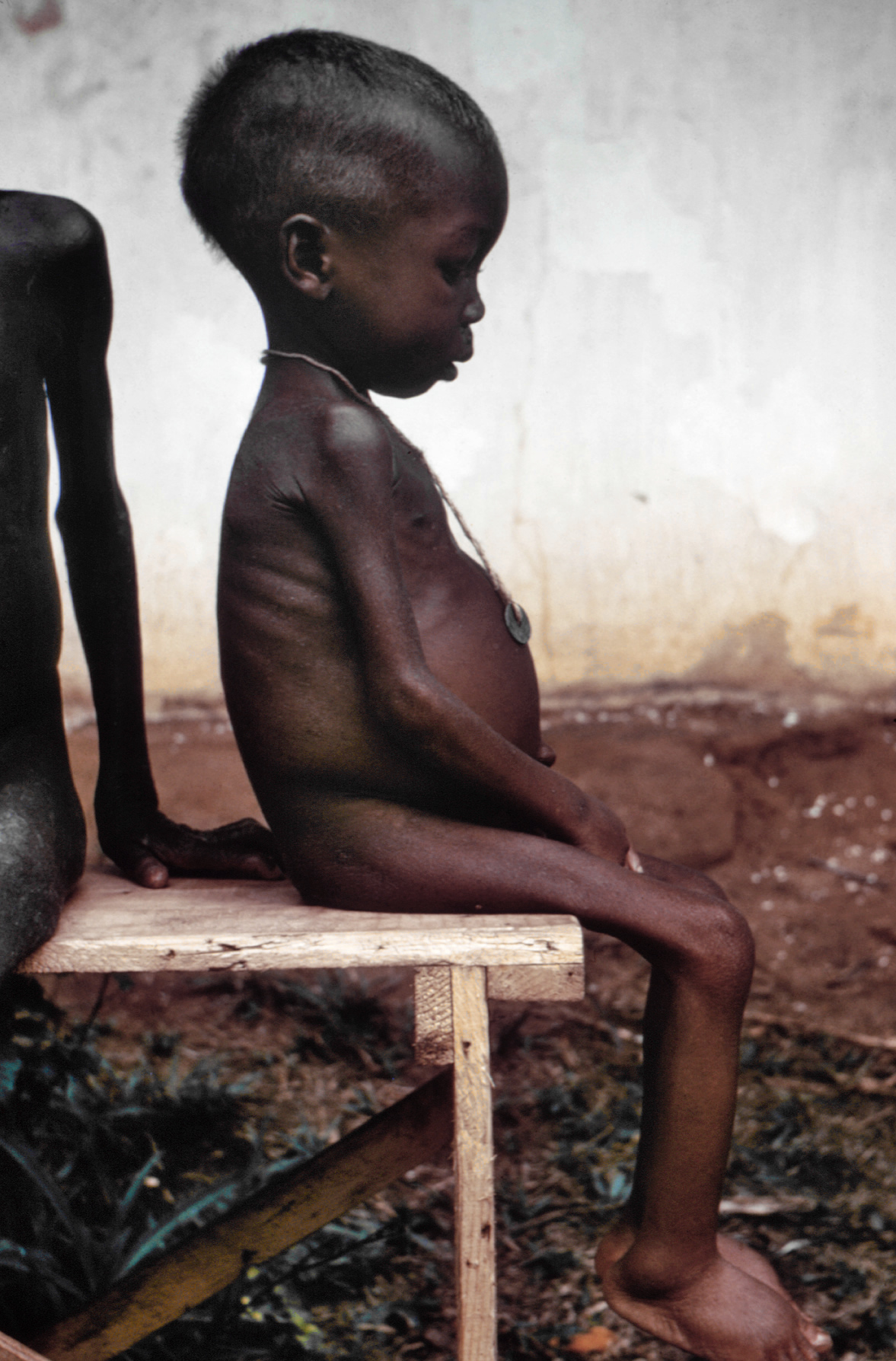

was imposed as a deliberate policy during the ensuing stalemate which led to mass starvation. During the two and half years of the war, there were about 100,000 overall military casualties, while between 500,000 and 2 million Biafran civilians died of starvation.

In mid-1968, images of malnourished and starving Biafran children saturated the mass media of

Western countries

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania. . The plight of the starving Biafrans became a ''

cause célèbre

A cause célèbre (,''Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged'', 12th Edition, 2014. S.v. "cause célèbre". Retrieved November 30, 2018 from https://www.thefreedictionary.com/cause+c%c3%a9l%c3%a8bre ,''Random House Kernerman Webs ...

'' in foreign countries, enabling a significant rise in the funding and prominence of international

non-governmental organizations

A non-governmental organization (NGO) or non-governmental organisation (see spelling differences) is an organization that generally is formed independent from government. They are typically nonprofit entities, and many of them are active in h ...

(NGOs). The

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

and the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

were the main supporters of the Nigerian government, while

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

,

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

(after 1968) and some other countries supported

Biafra

Biafra, officially the Republic of Biafra, was a partially recognised secessionist state in West Africa that declared independence from Nigeria and existed from 1967 until 1970. Its territory consisted of the predominantly Igbo-populated form ...

. The United States' official position was one of neutrality, considering Nigeria as "a responsibility of Britain", but some interpret the refusal to recognize Biafra as favouring the Nigerian government.

Background

Ethnic division

This

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

can be connected to the

colonial amalgamation in 1914 of

Northern protectorate,

Lagos Colony

Lagos Colony was a British colonial possession centred on the port of Lagos in what is now southern Nigeria. Lagos was annexed on 6 August 1861 under the threat of force by Commander Beddingfield of HMS Prometheus who was accompanied by the Ac ...

and

Southern Nigeria protectorate

Southern Nigeria was a British Empire, British protectorate in the coastal areas of modern-day Nigeria formed in 1900 from the union of the Niger Coast Protectorate with territories chartered by the Royal Niger Company below Lokoja on the Niger ...

(later renamed

Eastern Nigeria

The Eastern Region was an administrative region in Nigeria, dating back originally from the division of the colony Southern Nigeria in 1954. Its first capital was Calabar. The capital was later moved to Enugu and the second capital was Umuahia. Th ...

), which was intended for better administration due to the close proximity of these

protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

s . However, the change did not take into consideration the differences in the culture and religions of the people in each area. Competition for political and economic power exacerbated tensions.

Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

gained independence from the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

on 1 October 1960, with a population of 45.2 million made up of more than 300 differing ethnic and cultural groups . When the colony of Nigeria had been created, its three largest ethnic groups were the

Igbo

Igbo may refer to:

* Igbo people, an ethnic group of Nigeria

* Igbo language, their language

* anything related to Igboland, a cultural region in Nigeria

See also

* Ibo (disambiguation)

* Igbo mythology

* Igbo music

* Igbo art

*

* Igbo-Ukwu, a t ...

, who formed about 60–70% of the population in the southeast; the

Hausa-Fulani of the

Sultanate of Sokoto, who formed about 67% of the population in the northern part of the territory; and the

Yoruba

The Yoruba people (, , ) are a West African ethnic group that mainly inhabit parts of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. The areas of these countries primarily inhabited by Yoruba are often collectively referred to as Yorubaland. The Yoruba constitute ...

, who formed about 75% of the population in the Southwestern part.

Although these groups have their own homelands, by the 1960s, the people were dispersed across Nigeria, with all three ethnic groups represented

substantially in major cities . When the war broke out in 1967, there were still 5,000 Igbos in

Lagos

Lagos (Nigerian English: ; ) is the largest city in Nigeria and the List of cities in Africa by population, second most populous city in Africa, with a population of 15.4 million as of 2015 within the city proper. Lagos was the national ca ...

.

The semi-

feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a wa ...

and

Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

Hausa-Fulani in the North were traditionally ruled by a conservative Islamic hierarchy consisting of

emir

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cerem ...

s who in turn owed their ultimate allegiance to the

Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

of Sokoto. This

Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

was regarded as the source of all political power and religious authority.

The

Yoruba

The Yoruba people (, , ) are a West African ethnic group that mainly inhabit parts of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. The areas of these countries primarily inhabited by Yoruba are often collectively referred to as Yorubaland. The Yoruba constitute ...

political system

In political science, a political system means the type of political organization that can be recognized, observed or otherwise declared by a state.

It defines the process for making official government decisions. It usually comprizes the govern ...

in the southwest, like that of the Hausa-Fulani, also consisted of a series of

monarchs

A monarch is a head of stateWebster's II New College DictionarMonarch Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest authority and power in ...

, the

Oba. The Yoruba monarchs, however, were less

autocratic

Autocracy is a system of government in which absolute power over a state is concentrated in the hands of one person, whose decisions are subject neither to external legal restraints nor to regularized mechanisms of popular control (except perh ...

than those in the North. The political and social system of the Yoruba accordingly allowed for greater

upward mobility

Social mobility is the movement of individuals, families, households or other categories of people within or between social strata in a society. It is a change in social status relative to one's current social location within a given society ...

, based on acquired rather than inherited wealth and title.

In contrast to the two other groups, Igbos and the ethnic groups of the

Niger Delta

The Niger Delta is the delta of the Niger River sitting directly on the Gulf of Guinea on the Atlantic Ocean in Nigeria. It is located within nine coastal southern Nigerian states, which include: all six states from the South South geopolitical ...

in the southeast lived mostly in autonomous, democratically organized communities, although there were E''ze'' or monarchs in many of the ancient cities, such as the

Kingdom of Nri

The Kingdom of Nri () was a medieval polity located in what is now Nigeria. The kingdom existed as a sphere of religious and political influence over a third of Igboland, and was administered by a priest-king called an ''Eze Nri''. The ''Eze Nri ...

. At its zenith, the Kingdom controlled most of Igbo land, including influence on the

Anioma people

Anioma people are a subgroup of the Igbo ethnic group in Delta State, Nigeria. They are made up of communities which span across 9 Local government areas and speak different varieties of the Igbo language, including the Enuani language, Ukwuani l ...

,

Arochukwu

Arochukwu Local Government Area, sometimes referred to as Arochuku or Aro Oke-Igbo, is the third largest local government area in Abia State (after Aba and Umuahia) in southeastern Nigeria and homeland of the Igbo subgroup, Aro people.

It is co ...

(which controlled

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in Igbo), and

Onitsha

Onitsha ( or just ''Ọ̀nị̀chà'') is a city located on the eastern bank of the Niger River, in Anambra State, Nigeria. A metropolitan city, Onitsha is known for its river port and as an economic hub for commerce, industry, and education. ...

land. Unlike the other two regions, decisions within the Igbo communities were made by a general assembly in which men and women participated.

The differing

political systems

In political science, a political system means the type of political organization that can be recognized, observed or otherwise declared by a state.

It defines the process for making official government decisions. It usually comprizes the govern ...

and structures reflected and produced divergent customs and values. The Hausa-Fulani commoners, having contact with the political system only through a village head designated by the Emir or one of his subordinates, did not view political leaders as amenable to influence. Political decisions were to be submitted. As with many other

authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

religious and political systems, leadership positions were given to persons willing to be subservient and loyal to superiors. A chief function of this political system in this context was to maintain conservative values, which caused many Hausa-Fulani to view economic and social innovation as subversive or sacrilegious.

In contrast to the Hausa-Fulani, the Igbos and other Biafrans often participated directly in the decisions which affected their lives. They had a lively awareness of the political system and regarded it as an instrument for achieving their personal goals. Status was acquired through the ability to

arbitrate

Arbitration is a form of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) that resolves disputes outside the judiciary courts. The dispute will be decided by one or more persons (the 'arbitrators', 'arbiters' or 'arbitral tribunal'), which renders the ' ...

disputes that might arise in the village, and through acquiring rather than inheriting wealth. The Igbo had been substantially victimized in the

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

; in the year 1790, it was reported that of 20,000 people sold each year from

Bonny, 16,000 were Igbo. With their emphasis upon social achievement and political participation, the Igbo adapted to and challenged colonial rule in innovative ways.

These tradition-derived differences were perpetuated and perhaps enhanced by the

colonial government in Nigeria. In the North, the colonial government found it convenient to

rule indirectly through the Emirs, thus perpetuating rather than changing the

indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

authoritarian political system. Christian

missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

were excluded from the North, and the area thus remained virtually closed to European cultural influence. By contrast the richest of the Igbo often sent their sons to British universities, with the intention of preparing them to work with the British. During the ensuing years, the Northern Emirs maintained their traditional political and religious institutions, while reinforcing their

social structure

In the social sciences, social structure is the aggregate of patterned social arrangements in society that are both emergent from and determinant of the actions of individuals. Likewise, society is believed to be grouped into structurally rel ...

. At the time of independence in 1960, the North was by far the most underdeveloped area in Nigeria. It had an English literacy rate of 2%, as compared to 19.2% in the East (literacy in

Ajami

''Ajam'' ( ar, عجم, ʿajam) is an Arabic word meaning mute, which today refers to someone whose mother tongue is not Arabic. During the Arab conquest of Persia, the term became a racial pejorative. In many languages, including Persian, Tur ...

(local languages in Arabic script), learned in connection with religious education, was much higher). The West also enjoyed a much higher literacy level, as it was the first part of the country to have contact with western education, and established a free primary education program under the pre-independence Western Regional Government.

['' Biafra Story'', Frederick Forsyth, Leo Cooper, 2001 ]

In the West, the missionaries rapidly introduced Western forms of education. Consequently, the Yoruba were the first group in Nigeria to adopt Western bureaucratic social norms. They made up the first classes of African civil servants, doctors, lawyers, and other technicians and professionals.

Missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

were introduced at a later date in Eastern areas because the British experienced

difficulty establishing firm control over the highly autonomous communities. However, the Igbo and other Biafran people actively embraced Western education, and they overwhelmingly came to adopt Christianity. Population pressure in the Igbo homeland, combined with aspirations for monetary wages, drove thousands of Igbos to other parts of Nigeria in search of work. By the 1960s, Igbo political culture was more unified and the region relatively prosperous, with tradesmen and literate elites active not just in the traditionally Igbo East, but throughout Nigeria. By 1966, the traditional ethnic and religious differences between Northerners and the Igbo were exacerbated by new differences in education and economic class.

Politics and economics of federalism

The colonial administration divided Nigeria into three regions—North, West and East—something which exacerbated the already well-developed economic, political, and social differences among Nigeria's different

ethnic groups

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

. The country was divided in such a way that the North had a slightly higher population than the other two regions combined. There were also widespread reports of

fraud

In law, fraud is intentional deception to secure unfair or unlawful gain, or to deprive a victim of a legal right. Fraud can violate civil law (e.g., a fraud victim may sue the fraud perpetrator to avoid the fraud or recover monetary compens ...

during Nigeria's first

census

A census is the procedure of systematically acquiring, recording and calculating information about the members of a given population. This term is used mostly in connection with national population and housing censuses; other common censuses incl ...

, and even today population remains a highly political issue in Nigeria. On this basis, the Northern Region was allocated a majority of the seats in the Federal Legislature established by the colonial authorities. Within each of the three regions the dominant ethnic groups, the Hausa-Fulani, Yoruba, and Igbo, respectively formed political parties that were largely regional and based on ethnic

allegiance

An allegiance is a duty of fidelity said to be owed, or freely committed, by the people, subjects or citizens to their state or sovereign.

Etymology

From Middle English ''ligeaunce'' (see medieval Latin ''ligeantia'', "a liegance"). The ''al ...

s: the

Northern People's Congress

Northern People's Congress (NPC) is a political party in Nigeria. Formed in June 1949, the party held considerable influence in the Northern Region from the 1950s until the military coup of 1966. It was formerly a cultural organization known as J ...

(NPC) in the North; the

Action Group in the West (AG); and the

National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons

The National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) later changed to the National Convention of Nigerian Citizens, was a Nigerian nationalist political party from 1944 to 1966, during the period leading up to independence and immediately ...

(NCNC) in the East. Although these parties were not exclusively

homogeneous

Homogeneity and heterogeneity are concepts often used in the sciences and statistics relating to the uniformity of a substance or organism. A material or image that is homogeneous is uniform in composition or character (i.e. color, shape, siz ...

in terms of their ethnic or regional make-up, the disintegration of Nigeria resulted largely from the fact that these parties were primarily based in one region and one tribe.

The basis of modern Nigeria formed in 1914 when the United Kingdom amalgamated the

Northern

Northern may refer to the following:

Geography

* North, a point in direction

* Northern Europe, the northern part or region of Europe

* Northern Highland, a region of Wisconsin, United States

* Northern Province, Sri Lanka

* Northern Range, a ra ...

and

Southern

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, M ...

protectorates. Beginning with the Northern Protectorate, the

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

implemented a system of

indirect rule

Indirect rule was a system of governance used by the British and others to control parts of their colonial empires, particularly in Africa and Asia, which was done through pre-existing indigenous power structures. Indirect rule was used by variou ...

of which they exerted influence through alliances with local forces. This system worked so well, Colonial Governor

Frederick Lugard

Frederick John Dealtry Lugard, 1st Baron Lugard (22 January 1858 – 11 April 1945), known as Sir Frederick Lugard between 1901 and 1928, was a British soldier, mercenary, explorer of Africa and colonial administrator. He was Governor of Hong ...

successfully lobbied to extend it to the Southern

Protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

through amalgamation. In this way, a foreign and hierarchical system of governance was imposed on the Igbos.

Intellectuals

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking

Critical thinking is the analysis of available facts, evidence, observations, and arguments to form a judgement. The subject is complex; several different definitions exist, ...

began to agitate for greater rights and independence. The size of this intellectual class increased significantly in the 1950s, with the massive expansion of the national education program. During the 1940s and 1950s, the Igbo and Yoruba parties were in the forefront of the campaign for independence from British rule. Northern leaders, fearful that independence would mean political and

economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

domination by the more Westernized elites in the South, preferred the continuation of British rule. As a condition for accepting independence, they demanded that the country continue to be divided into three regions with the North having a clear majority. Igbo and Yoruba leaders, anxious to obtain an independent country at all costs, accepted the Northern demands.

However, the two Southern regions had significant cultural and ideological differences, leading to discord between the two Southern political parties. Firstly, the AG favoured a loose confederacy of regions in the emergent Nigerian nation whereby each region would be in total control of its own distinct territory. The status of Lagos was a sore point for the AG, which did not want Lagos, a Yoruba town situated in Western Nigeria (which was at that time the federal capital and seat of national government) to be designated as the capital of Nigeria, if it meant loss of Yoruba

sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

. The AG insisted that Lagos must be completely recognized as a Yoruba town without any loss of identity, control or autonomy by the Yoruba. Contrary to this position, the NCNC was anxious to declare Lagos, by virtue of it being the "Federal Capital Territory" as "no man's land"—a declaration which as could be expected angered the AG, which offered to help fund the development of another territory in Nigeria as

"Federal Capital Territory" and then threatened secession from Nigeria if it didn't get its way. The threat of secession by the AG was tabled, documented and recorded in numerous constitutional conferences, including the constitutional conference held in London in 1954 with the demand that a right of secession be enshrined in the constitution of the emerging Nigerian nation to allow any part of the emergent nation to opt out of Nigeria, should the need arise. This proposal for inclusion of right of secession by the regions in independent Nigeria by the AG was rejected and resisted by NCNC which vehemently argued for a tightly bound united/unitary structured nation because it viewed the provision of a secession clause as detrimental to the formation of a unitary Nigerian state. In the face of sustained opposition by the

NCNC delegates, later joined by the NPC and backed by threats to view maintenance of the inclusion of secession by the AG as treasonable by the British, the AG was forced to renounce its position of inclusion of the right of secession a part of the Nigerian constitution. Had such a provision been made in the Nigerian constitution, later events which led to the Nigerian/Biafran civil war may have been avoided. The pre-independence alliance between the NCNC and the NPC against the aspirations of the AG would later set the tone for political governance of independent Nigeria by the NCNC/NPC and lead to disaster in later years in Nigeria.

Northern–Southern tension manifested firstly in the 1945 Jos Riot in which 300 Igbo people died

and again on 1 May 1953, as

fighting in the Northern city of Kano. The political parties tended to focus on building power in their own regions, resulting in an incoherent and disunified dynamic in the federal government.

In 1946, the British

divided

Division is one of the four basic operations of arithmetic, the ways that numbers are combined to make new numbers. The other operations are addition, subtraction, and multiplication.

At an elementary level the division of two natural numb ...

the Southern Region into the Western Region and the

Eastern Region. Each government was entitled to collect

royalties

A royalty payment is a payment made by one party to another that owns a particular asset, for the right to ongoing use of that asset. Royalties are typically agreed upon as a percentage of gross or net revenues derived from the use of an asset o ...

from resources extracted within its area. This changed in 1956 when

Shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

** Thin-shell structure

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard ou ...

-

BP found large petroleum deposits in the Eastern region. A Commission led by

Sir Jeremy Raisman and

Ronald Tress

Ronald C Tress, CBE, (11 January 1915 – 28 September 2006) was a British economist.

He studied Economics 1933–36 at University College, Southampton taking a University of London external degree.

Beginning in 1941 he was an economic advise ...

determined that resource royalties would now enter a "Distributable Pools Account" with the money split between different parts of government (50% to region of origin, 20% to federal government, 30% to other regions). To ensure continuing influence, the British government promoted unity in the Northern bloc and secessionist sentiments among and within the two Southern regions. The Nigerian government, following independence, promoted discord in the West with the creation of a new

Mid-Western Region in an area with oil potential. The new constitution of 1946 also proclaimed that "The entire property in and control of all

mineral oils, in, under, or upon any lands, in Nigeria, and of all rivers, streams, and watercourses throughout Nigeria, is and shall be vested in, the Crown." The United Kingdom profited significantly from a fivefold rise in Nigerian exports amidst the post-war economic boom.

Independence and First Republic

Nigeria gained independence on 1 October 1960, and the

First Republic came to be on 1 October 1963. The first prime minister of Nigeria,

Abubakar Tafawa Balewa

Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa (December 1912 – 15 January 1966) was a Nigerian politician who served as the first and only Prime Minister of Nigeria upon independence.

Early life

Abubakar Tafawa Balewa was born in December 1912 in modern-day B ...

, was a northerner and

co-founder

An organizational founder is a person who has undertaken some or all of the formational work needed to create a new organization, whether it is a business, a charitable organization, a governing body, a school, a group of entertainers, or any other ...

of the Northern People's Congress. He formed an alliance with the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons party, and its popular nationalist leader

Nnamdi "Zik" Azikiwe, who became

Governor General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

and then President. The Yoruba-aligned Action Group, the third major party, played the opposition role.

Workers became increasingly aggrieved by low wages and bad conditions, especially when they compared their lot to the lifestyles of

politicians

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

in Lagos. Most wage earners lived in the Lagos area, and many lived in overcrowded dangerous housing. Labour activity including strikes intensified in 1963, culminating in a nationwide general strike in June 1964. Strikers disobeyed an ultimatum to return to work and at one point were dispersed by riot police. Eventually, they did win wage increases. The strike included people from all ethnic groups. Retired Brigadier General H. M. Njoku later wrote that the general strike heavily exacerbated tensions between the Army and ordinary

civilians

Civilians under international humanitarian law are "persons who are not members of the armed forces" and they are not "combatants if they carry arms openly and respect the laws and customs of war". It is slightly different from a non-combatant, b ...

, and put pressure on the Army to take action against a government which was widely perceived as corrupt.

The

1964 elections, which involved heavy campaigning all year, brought ethnic and regional divisions into focus. Resentment of politicians ran high and many campaigners feared for their safety while touring the country. The Army was repeatedly deployed to

Tiv Division, killing hundreds and arresting thousands of

Tiv people

Tiv (or Tiiv) are a Tivoid ethnic group. They constitute approximately 2.4% of Nigeria's total population, and number over 5 million individuals throughout Nigeria and Cameroon.

The Tiv language is spoken by about 5 million people in ...

agitating for self-determination.

[Diamond, ''Class, Ethnicity and Democracy in Nigeria'' (1988), chapter 7: "The 1964 Federal Election Crisis" (pp. 190–247).]

Widespread reports of fraud tarnished the election's legitimacy.

Westerners

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania. especially resented the political domination of the Northern People's Congress, many of whose candidates ran unopposed in the election. Violence spread throughout the country and some began to flee the North and West, some to

Dahomey

The Kingdom of Dahomey () was a West African kingdom located within present-day Benin that existed from approximately 1600 until 1904. Dahomey developed on the Abomey Plateau amongst the Fon people in the early 17th century and became a region ...

. The apparent domination of the political system by the North, and the chaos breaking out across the country, motivated elements within the military to consider decisive action.

In addition to Shell-BP, the British reaped profits from mining and commerce. The British-owned

United Africa Company

The United Africa Company (UAC) was a British company which principally traded in West Africa during the 20th century.

The United Africa Company was formed in 1929 as a result of the merger of The Niger Company, which had been effectively owne ...

alone controlled 41.3% of all Nigeria's foreign trade. At 516,000 barrels per day, Nigeria had become the tenth-biggest oil exporter in the world.

Though the

Nigeria Regiment

The Nigeria Regiment, Royal West African Frontier Force, was formed by the amalgamation of the Northern Nigeria Regiment and the Southern Nigeria Regiment on 1 January 1914. At that time, the regiment consisted of five battalions:

*1st Battalio ...

had fought for the United Kingdom in both the

First

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

and

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

s, the army Nigeria inherited upon

independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

in 1960 was an internal security force designed and trained to assist the police in putting down challenges to authority rather than to fight a war.

[Barua, Pradeep ''The Military Effectiveness of Post-Colonial States'' (2013) p. 20] The Indian historian Pradeep Barua called the Nigerian Army in 1960 "a glorified police force", and even after independence, the Nigerian military retained the role it held under the British in the 1950s.

The Nigerian Army did not conduct field training, and notably lacked heavy weapons.

Before 1948, Nigerians were not allowed to hold officer's commissions, and only in 1948 were certain promising Nigerian recruits allowed to attend

Sandhurst for officer training while at the same time Nigerian NCOs were allowed to become officers if they completed a course in officer training at

Mons Hall or Eaton Hall in England.

[Barua, Pradeep ''The Military Effectiveness of Post-Colonial States'' (2013) p. 22] Despite the reforms, only an average of two Nigerians per year were awarded officers' commissions between 1948–55 and only seven per year from 1955 to 1960.

At the time of independence in 1960, of the 257 officers commanding the Nigeria Regiment which became the Nigerian Army, only 57 were Nigerians.

Using the "

martial race

Martial race was a designation which was created by army officials in British India after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, in which they classified each caste as belonging to one of two categories, the 'martial' caste and the 'non-martial' caste. T ...

s" theory first developed under the

Raj

Raj or RAJ may refer to:

History

* British Raj, the 1858–1947 rule of the British Crown over India

* Company Raj, the 1757–1858 rule of the East India Company in South Asia

* Licence Raj, the Indian system of elaborate licences, regulation ...

in 19th-century

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, the colonial government had decided that peoples from northern Nigeria such as the Hausa, Kiv, and Kanuri were the hard "

martial races

Martial race was a designation which was created by army officials in British India after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, in which they classified each caste as belonging to one of two categories, the 'martial' caste and the 'non-martial' caste. T ...

" whose recruitment was encouraged while the peoples from southern Nigeria such as the Igbos and the Yoruba were viewed as too soft to make for good soldiers and hence their

recruitment

Recruitment is the overall process of identifying, sourcing, screening, shortlisting, and interviewing candidates for jobs (either permanent or temporary) within an organization. Recruitment also is the processes involved in choosing individual ...

was discouraged.

[Barua, Pradeep ''The Military Effectiveness of Post-Colonial States'' (2013) p. 21] As a result, by 1958, men from northern Nigeria made up 62% of the Nigeria Regiment while men from the south and the west made up only 36%.

In 1958, the policy was changed: henceforward men from the north would make up only 50% of the soldiers while men from the southeast and southwest were each to make up 25%. The new policy was retained after independence.

The previously favored northerners whose egos had been stoked by being told by their officers that they were the tough and hardy "martial races" greatly resented the change in recruitment policies, all the more as after independence in 1960 there were opportunities for Nigerian men to serve as officers that had not existed prior to independence.

As men from the southeast and southwest were generally much better educated than men from the north, they were much more likely to be promoted to officers in the newly founded Nigerian Army, which provoked further resentment from the northerners.

At the same time, as a part of Nigerianisation policy, it was government policy to send home the British officers who had been retained after independence, by promoting as many Nigerians as possible until by 1966 there were no more British officers. As part of the Nigerianisation policy, educational standards for officers were drastically lowered with only a high school diploma being necessary for an officer's commission while at the same time Nigerianisation resulted in an extremely youthful officer corps, full of ambitious men who disliked the Sandhurst graduates who served in the high command as blocking further chances for promotion. A group of Igbo officers formed a conspiracy to overthrow the government, seeing the northern prime minister, Sir

Abubakar Tafawa Balewa

Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa (December 1912 – 15 January 1966) was a Nigerian politician who served as the first and only Prime Minister of Nigeria upon independence.

Early life

Abubakar Tafawa Balewa was born in December 1912 in modern-day B ...

, as allegedly plundering the oil wealth of the southeast.

[Barua, Pradeep ''The Military Effectiveness of Post-Colonial States'' (2013) p. 9]

Military coups

On 15 January 1966, Major

Chukuma Kaduna Nzeogwu, Major

Emmanuel Ifeajuna

Emmanuel Arinze Ifeajuna (1935 – 25 September 1967) was a Nigerian army major and high jumper. He was the first Black African to win a gold medal at an international sports event when he won at the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Game ...

, and other junior Army officers (mostly majors and captains) attempted

a coup d'état. The two major political leaders of the north, the Prime Minister, Sir

Abubakar Tafawa Balewa

Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa (December 1912 – 15 January 1966) was a Nigerian politician who served as the first and only Prime Minister of Nigeria upon independence.

Early life

Abubakar Tafawa Balewa was born in December 1912 in modern-day B ...

and the Premier of the northern region, Sir

Ahmadu Bello

Ahmadu Ibrahim Bello, Sardauna of Sokoto (12 June 1910–15 January 1966), knighted as Sir Ahmadu Bello, was a conservative Nigerian statesman who masterminded Northern Nigeria through the independence of Nigeria in 1960 and served as its first a ...

were executed by Major Nzeogwu. Also murdered was Sir Ahmadu Bello's wife and officers of Northern extraction. The President, Sir

Nnamdi Azikiwe

Nnamdi Benjamin Azikiwe, (16 November 1904 – 11 May 1996), usually referred to as "Zik", was a Nigerian statesman and political leader who served as the first President of Nigeria from 1963 to 1966. Considered a driving force behind the n ...

, an Igbo, was on an extended vacation in the West Indies. He did not return until days after the coup. There was widespread suspicion that the Igbo coup plotters had tipped him and other Igbo leaders off regarding the pending coup. In addition to the killings of the Northern political leaders, the Premier of the Western region, Ladoke Akintola and Yoruba senior military officers were also killed. The coup, also referred to as "The Coup of the Five Majors", has been described in some quarters as Nigeria's only revolutionary coup. This was the first coup in the short life of Nigeria's nascent second democracy. Claims of electoral fraud were one of the reasons given by the coup plotters. Besides killing much of Nigeria's elite, the "Majors' Coup" also saw much of the leadership of the Nigerian Federal Army killed with seven officers holding the rank above colonel killed.

Of the seven officers killed, four were northerners, two were from the southeast and one was from the Midwest. Only one was a Igbo.

This coup was, however, not seen as a revolutionary coup by other sections of Nigerians, especially in the Northern and Western sections and by later revisionists of Nigerian coups. Some alleged, mostly from Eastern part of Nigeria, that the majors sought to spring Action Group leader

Obafemi Awolowo

Chief Obafemi Jeremiah Oyeniyi Awolowo (; 6 March 1909 – 9 May 1987) was a Yoruba nationalist and Nigerian statesman who played a key role in Nigeria's independence movement (1957-1960). Awolowo founded the Yoruba nationalist group Egbe Om ...

out of jail and make him head of the new government. Their intention was to dismantle the Northern-dominated power structure but their efforts to take power were unsuccessful.

Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi

Johnson Thomas Umunnakwe Aguiyi-Ironsi (3 March 1924 – 29 July 1966) was the first military head of state of Nigeria. He seized power during the ensuing chaos after the 15 January 1966 military coup, which decapitated the country's leadersh ...

, an Igbo and loyalist head of the

Nigerian Army

The Nigerian Army (NA) is the land force of the Nigerian Armed Forces. It is governed by the Nigerian Army Council (NAC). The Chief of Army Staff is the highest ranking military officer of the Nigerian Army.

History Formation

The Nigerian ...

, suppressed coup operations in the South and he was declared head of state on 16 January after the surrender of the majors.

In the end though, the majors were not in the position to embark on this political goal. While their 15th January coup succeeded in seizing political control in the north, it failed in the south, especially in the Lagos-Ibadan-Abeokuta military district where loyalist troops led by army commander Johnson Aguyi-Ironsi succeeded in crushing the revolt. Apart from Ifeajuna who fled the country after the collapse of their coup, the other two January Majors, and the rest of the military officers involved in the revolt, later surrendered to the loyalist High Command and were subsequently detained as a federal investigation of the event began.

Aguyi-Ironsi suspended the constitution and dissolved parliament. He abolished the regional confederated form of government and pursued unitary policies favoured by the NCNC, having apparently been influenced by NCNC political philosophy. He, however, appointed Colonel

Hassan Katsina

Hassan Usman Katsina (31 March 1933 – 24 July 1995), titled Chiroman Katsina, was the last Governor of Northern Nigeria. He served as Chief of Army Staff during the Nigerian Civil War and later became the Deputy Chief of Staff, Supreme Headqua ...

, son of

Katsina

Katsina, likely from "Tamashek" eaning son or bloodor mazza enwith "inna" otheris a Local Government Area and the capital city of Katsina State, in northern Nigeria. emir

Usman Nagogo

Alhaji Sir Usman Nagogo dan Muhammadu Dikko (1905 – 18 March 1981) was Emir of Katsina (''Sarkin Katsina'') from 19 May 1944, until his death. A Fulani from the Sullubawa Clan, he succeeded his father, Muhammadu Dikko, as Emir, and was suc ...

, to govern the Northern Region, indicating some willingness to maintain cooperation with this bloc. He also preferentially released northern politicians from jail (enabling them to plan his forthcoming overthrow). Aguyi-Ironsi rejected a British offer of military support but promised to protect British interests.

Ironsi fatally did not bring the failed plotters to trial as required by then-military law and as advised by most northern and western officers, rather, coup plotters were maintained in the military on full pay, and some were even promoted while awaiting trial. The coup, despite its failures, was widely seen as primarily benefiting the Igbo peoples, as the plotters received no repercussions for their actions and no significant Igbo political leaders were affected. While those that executed the coup were mostly Northern, most of the known plotters were Igbo and the military and political leadership of Western and Northern regions had been largely bloodily eliminated while the Eastern military/political leadership was largely untouched. However, Ironsi, himself an Igbo, was thought to have made numerous attempts to please Northerners. The other events that also fuelled suspicions of a so-called "Igbo conspiracy" were the killing of Northern leaders, and the killing of the Brigadier-General

Ademulegun's pregnant wife by the coup executioners.

Despite the overwhelming contradictions of the coup being executed by mostly Northern soldiers (such as John Atom Kpera, later military governor of

Benue State

Benue State is one of the North Central states in Nigeria with a population of about 4,253,641 in 2006 census. The state was created in 1976 among the 7 states created at that time.The state derives its name from the Benue River which is th ...

), the killing of Igbo soldier Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur Unegbe by coup executioners, and Ironsi's termination of an Igbo-led coup, the ease by which Ironsi stopped the coup led to suspicion that the Igbo coup plotters planned all along to pave the way for Ironsi to take the reins of power in Nigeria.

Colonel

Odumegwu Ojukwu

Chukwuemeka "Emeka" Odumegwu Ojukwu (4 November 1933 – 26 November 2011) was a Nigerian military officer, statesman and politician who served as the military governor of the Eastern Region of Nigeria in 1966 and the president of the se ...

became military governor of the Eastern Region at this time.

On 24 May 1966, the military government issued Unification Decree #34, which would have replaced the federation with a more centralised system. The Northern bloc found this decree intolerable.

In the face of provocation from the Eastern media which repeatedly showed humiliating posters and cartoons of the slain northern politicians, on the night of 29 July 1966, northern soldiers at Abeokuta barracks mutinied, thus precipitating

a counter-coup, which had already been in the planning stages. Ironsi was on a visit to

Ibadan

Ibadan (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Oyo State, in Nigeria. It is the third-largest city by population in Nigeria after Lagos and Kano, with a total population of 3,649,000 as of 2021, and over 6 million people within its me ...

during their mutiny and there he was killed (along with his host,

Adekunle Fajuyi

Francis Adekunle Fajuyi (26 June 1926 – 29 July 1966) was a Nigerian soldier of Yoruba origin. and the first military governor of the former Western Region, Nigeria.

Originally a teacher and clerk, Fajuyi of Ado Ekiti joined the army in ...

). The counter-coup led to the installation of Lieutenant-Colonel Yakubu Gowon as Supreme Commander of the Nigerian Armed Forces. Gowon was chosen as a compromise candidate. He was a Northerner, a Christian, from a minority tribe, and had a good reputation within the army.

It seems that Gowon immediately faced not only a potential standoff with the East, but secession threats from the Northern and even the Western region. The counter-coup plotters had considered using the opportunity to withdraw from the federation themselves. Ambassadors from the United Kingdom and the United States, however, urged Gowon to maintain control over the whole country. Gowon followed this plan, repealing the Unification Decree, announcing a return to the federal system.

Persecution of Igbo

From June through October 1966,

pogroms in the North killed an estimated 8,000 to 30,000 Igbo, half of them children, and caused more than a million to two million to flee to the Eastern Region. 29 September 1966 became known as 'Black Thursday', as it was considered the worst day of the massacres.

Ethnomusicologist Charles Keil, who was visiting Nigeria in 1966, recounted:

The pogroms I witnessed in Makurdi

Makurdi is the capital of Benue State, located in central Nigeria, and part of the Middle Belt region of central Nigeria. The city is situated on the south bank of the Benue River. In 2016, Makurdi and the surrounding areas had an estimated popula ...

, Nigeria (late Sept. 1966) were foreshadowed by months of intensive anti-Igbo and anti-Eastern conversations among Tiv, Idoma, Hausa and other Northerners resident in Makurdi, and, fitting a pattern replicated in city after city, the massacres were led by the Nigerian army. Before, during and after the slaughter, Col. Gowon could be heard over the radio issuing 'guarantees of safety' to all Easterners, all citizens of Nigeria, but the intent of the soldiers, the only power that counts in Nigeria now or then, was painfully clear. After counting the disembowelled bodies along the Makurdi road I was escorted back to the city by soldiers who apologised for the stench and explained politely that they were doing me and the world a great favour by eliminating Igbos.

The Federal Military Government also laid the groundwork for the economic blockade of the Eastern Region which went into full effect in 1967.

[Stevenson, ''Capitol Gains'' (2014), pp. 314–315. "In fact, the Federation's first response to Biafran secession was to deepen the blockade to include 'a blockade of the East's air and sea ports, a ban on foreign currency transactions, and a halt to all incoming post and telecommunications.' The Federation implemented its blockade so quickly during the war because it was a continuation of the policy from the year before."]

Breakaway

The deluge of refugees in Eastern Nigeria created a difficult situation. Extensive negotiations took place between Ojukwu, representing Eastern Nigeria, and Gowon, representing the Nigerian Federal military government. In the

Aburi Accord

The Aburi Accord or Aburi Declaration was reached at a meeting between 4 and 5 January 1967 in Aburi, Ghana, attended by delegates of both the Federal Government of Nigeria (the Supreme Military Council) and Eastern delegates led by the Eastern ...

, finally signed at Aburi,

Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

, the parties agreed that a looser Nigerian federation would be implemented. Gowon delayed announcement of the agreement and eventually reneged.

On 27 May 1967, Gowon proclaimed the division of Nigeria into twelve states. This decree carved the Eastern Region in three parts:

South Eastern State,

Rivers State

Rivers State, also known as Rivers, is a state in the Niger Delta region of southern Nigeria (Old Eastern Region). Formed in 1967, when it was split from the former Eastern Region, Rivers State borders include: Imo to the north, Abia and Akwa Ib ...

, and

East Central State

East Central State is a former administrative division of Nigeria. It was created on 27 May 1967 from parts of the Eastern Region and existed until 3 February 1976, when it was divided into two states - Anambra and Imo. The area now comprises fi ...

. Now the Igbos, concentrated in the East Central State, would lose control over most of the petroleum, located in the other two areas.

[Uche, "Oil, British Interests and the Nigerian Civil War" (2008), p. 123. "The oil revenue issue, however, came to a head when Gowon, on 27 May 1967, divided the country into twelve states. The Eastern Region was split into three states: South Eastern State, Rivers State and East Central State. This effectively excised the main oil-producing areas from the core Ibo state (East Central State). On 30 May 1967, Ojukwu declared independence and renamed the entire Eastern Region 'the Republic of Biafra'. As part of the effort to get the Biafran leadership to change its mind, the Federal government placed a shipping embargo on the territory."]

The Federal Military Government immediately placed an

embargo

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they m ...

on all shipping to and from Biafra—but not on oil tankers.

Biafra quickly moved to collect oil royalties from oil companies doing business within its borders.

When

Shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

** Thin-shell structure

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard ou ...

-

BP acquiesced to this request at the end of June, the Federal Government extended its blockade to include oil.

The blockade, which most foreign actors accepted, played a decisive role in putting Biafra at a disadvantage from the beginning of the war.

[Heerten & Moses, "The Nigeria–Biafra War" (2014), p. 174. "The FMG's major strategic advantage was not its military force, but its diplomatic status: internationally recognised statehood. That the FMG could argue that it was a sovereign government facing an 'insurgency' was decisive.... Nigeria's secured diplomatic status was also crucial for the most significant development in the war's early stages: the FMG's decision to blockade the secessionist state. To cut off Biafra's lines of communication with the outside world, air and sea ports were blockaded, foreign currency transactions banned, incoming mail and telecommunication blocked and international business obstructed. Even with its limited resources, Nigeria was able to organise a successful blockade without gaping holes or long interruptionsmostly because other governments or companies were ready to acquiesce to Lagos' handling of the matter."]

Although the very young nation had a chronic shortage of weapons to go to war, it was determined to defend itself. Although there was much sympathy in Europe and elsewhere, only five countries (

Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

,

Gabon

Gabon (; ; snq, Ngabu), officially the Gabonese Republic (french: République gabonaise), is a country on the west coast of Central Africa. Located on the equator, it is bordered by Equatorial Guinea to the northwest, Cameroon to the north ...

,

Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire, officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital is Yamoussoukro, in the centre of the country, while its largest city and economic centre is ...

,

Zambia

Zambia (), officially the Republic of Zambia, is a landlocked country at the crossroads of Central Africa, Central, Southern Africa, Southern and East Africa, although it is typically referred to as being in Southern Africa at its most cent ...

, and

Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

) officially recognised the new republic.

The United Kingdom supplied heavy weapons and ammunition to the Nigerian side because of its desire to preserve the country it had created. The Biafra side received arms and ammunition from France, even though the French government denied sponsoring Biafra. An article in ''

Paris Match

''Paris Match'' () is a French-language weekly news magazine. It covers major national and international news along with celebrity lifestyle features.

History and profile

A sports news magazine, ''Match l'intran'' (a play on ''L'Intransigeant' ...

'' of 20 November 1968 claimed that French arms were reaching Biafra through neighbouring countries such as Gabon. The heavy supply of weapons by the United Kingdom was the biggest factor in determining the outcome of the war.

Several peace accords were held, with the most notable one held at

Aburi

Aburi is a town in the Akuapim South Municipal District of the Eastern Region (Ghana), Eastern Region of south Ghana famous for the Aburi Botanical Gardens and the Odwira festival. , Ghana (the

Aburi Accord

The Aburi Accord or Aburi Declaration was reached at a meeting between 4 and 5 January 1967 in Aburi, Ghana, attended by delegates of both the Federal Government of Nigeria (the Supreme Military Council) and Eastern delegates led by the Eastern ...

). There were different accounts of what took place in Aburi. Ojukwu accused the federal government of going back on their promises while the federal government accused Ojukwu of distortion and half-truths.

Ojukwu gained agreement to a

confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

for Nigeria, rather than a federation. He was warned by his advisers that Gowon did not understand the difference and would renege upon the agreement.

When this happened, Ojukwu regarded it as both a failure by Gowon to keep to the spirit of the Aburi agreement and a lack of integrity on the side of the Nigerian Military Government in the negotiations toward a united Nigeria. Gowon's advisers, to the contrary, felt that he had enacted as much as was politically feasible in fulfilment of the spirit of Aburi.

[Ntieyong U. Akpan, ''The Struggle for Secession, 1966–1970: A Personal Account of the Nigerian Civil War''.] The Eastern Region was very ill-equipped for war, outmanned and outgunned by the Nigerians, but had the advantages of fighting in their homeland, support of most Easterners, determination, and use of limited resources.

The UK, which still maintained the highest level of influence over Nigeria's highly valued oil industry through Shell-BP,

and the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

supported the Nigerian government, especially by military supplies.

The Nigerian Army in 1967 was completely unready for war. The Nigerian Army had no training or experience of war on the

operational level

In the field of military theory, the operational level of war (also called operational art, as derived from russian: оперативное искусство, or operational warfare) represents the level of command that connects the details of ...

, still being primarily an internal security force.

Most Nigerian officers were more concerned with their social lives than military training, spending a disproportionate amount of their time on partying, drinking, hunting and playing games.

[Barua, Pradeep ''The Military Effectiveness of Post-Colonial States'' (2013) p. 24] Social status in the Army was extremely important and officers devoted an excessive amount of time to ensure their uniforms were always immaculate while there was a competition to own the most expensive automobiles and homes.

The killings and purges perpetuated during the two coups of 1966 had killed most of the Sandhurst graduates. By July 1966, all of the officers holding the rank above colonel had been either killed or discharged while only 5 officers holding the rank of lieutenant colonel were still alive and on duty.

Almost all of the junior officers had received their commissions after 1960 and most were heavily dependent on the more experienced NCOs to provide the necessary leadership.

The same problems that afflicted the Federal Army also affected the Biafran Army even more whose officer corps was based around former Federal Igbo officers.

[Barua, Pradeep ''The Military Effectiveness of Post-Colonial States'' (2013) p. 17] The shortage of experienced officers was a major problem for the

Biafran Army, made worse by a climate of paranoia and suspicion within Biafra as Ojukwu believed that other former Federal officers were plotting against him.

War

Shortly after extending its blockade to include oil, the Nigerian government launched a "

police action

In military/security studies and international relations, police action is a military action undertaken without a formal declaration of war. Today the term counter-insurgency is more used.

Since World War II, formal declarations of war have bee ...

" to retake the secessionist territory. The war began on the early hours of 6 July 1967 when Nigerian Federal troops

advanced in two columns into Biafra. The Biafra strategy had succeeded: the federal government had started the war, and the East was defending itself. The

Nigerian Army

The Nigerian Army (NA) is the land force of the Nigerian Armed Forces. It is governed by the Nigerian Army Council (NAC). The Chief of Army Staff is the highest ranking military officer of the Nigerian Army.

History Formation

The Nigerian ...

offensive was through the north of Biafra led by Colonel

Mohammed Shuwa

Mohammed Shuwa (1 September 1939 – 2 November 2012) was a Nigerian Army Major General and the first General Officer Commanding of the Nigerian Army's 1st Division. Shuwa commanded the Nigerian Army's 1st Division during the Nigerian Civil Wa ...

and the local military units were formed as the

1st Infantry Division. The division was led mostly by northern officers. After facing unexpectedly fierce resistance and high casualties, the western Nigerian column advanced on the town of

Nsukka

Nsukka is a town and a Local Government Area in Enugu State, Nigeria. Nsukka shares a common border as a town with Edem, Opi (archaeological site), Ede-Oballa, and Obimo.

The postal code of the area is 410001 and 410002 respectively referr ...

, which fell on 14 July, while the eastern column made for Garkem, which was captured on 12 July.

Biafran offensive

The Biafrans responded with an offensive of their own. On 9 August, Biafran forces crossed their western border and the Niger river into the MidWestern state of Nigeria. Passing through the state capital of

Benin City

Benin City is the capital and largest city of Edo State, Edo State, Nigeria. It is the fourth-largest city in Nigeria according to the 2006 census, after Lagos, Kano (city), Kano, and Ibadan, with a population estimate of about 3,500,000 as of ...

, the Biafrans advanced west until 21 August, when they were stopped at Ore in present-day

Ondo State

Ondo State ( yo, Ìpínlẹ̀ Oǹdó) is a state in southwestern Nigeria. It was created on 3 February 1976 from the former Western State. It borders Ekiti State to the north, Kogi State to the northeast, Edo State to the east, Delta State to t ...

, east of the Nigerian capital of Lagos. The Biafran attack was led by Lt. Col. Banjo, a Yoruba man , with the Biafran rank of brigadier. The attack met little resistance and the MidWestern state was easily taken over. This was due to the pre-secession arrangement that all soldiers should return to their regions to stop the spate of killings, in which Igbo soldiers had been major victims.

The Nigerian soldiers who were supposed to defend the MidWestern state were mostly Igbo from that state and, while some were in touch with their Biafran counterparts, others resisted the invasion. General Gowon responded by asking Colonel

Murtala Mohammed

Murtala Ramat Muhammad (8 November 1938 – 13 February 1976) was a Nigerian general who led the 1966 Nigerian counter-coup in overthrowing the Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi military regime and featured prominently during the Nigerian Civil War ...

(who later became head of state in 1975) to form another division (the 2nd Infantry Division) to expel the Biafrans from the MidWestern state, to defend the border of the Western state and to attack Biafra. At the same time, Gowon declared "total war" and announced the Federal government would mobilise the entire population of Nigeria for the war effort. From the summer of 1967 to the spring of 1969, the Federal Army grew from a force of 7,000 to a force of 200,000 men organised in three divisions. Biafra began the war with only 240 soldiers at

Enugu

Enugu ( ; ) is the capital city of Enugu State in Nigeria. It is located in southeastern part of Nigeria. The city had a population of 820,000 according to the 2022 Nigerian census. The name ''Enugu'' is derived from the two Igbo words ''Énú ...

, which grew to two battalions by August 1967, which soon were expanded into two brigades, the 51st and 52nd which became the core of the Biafran Army.

[Barua, Pradeep ''The Military Effectiveness of Post-Colonial States'' (2013) p. 11] By 1969, the Biafrans were to field 90,000 soldiers formed into five undermanned divisions together with a number of independent units.

As Nigerian forces retook the MidWestern state, the Biafran military administrator declared it to be the

Republic of Benin

Benin ( , ; french: Bénin , ff, Benen), officially the Republic of Benin (french: République du Bénin), and formerly Republic of Dahomey, Dahomey, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burki ...

on 19 September, though it ceased to exist the next day. The present country of

Benin

Benin ( , ; french: Bénin , ff, Benen), officially the Republic of Benin (french: République du Bénin), and formerly Dahomey, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the north ...

, west of Nigeria, was still named

Dahomey

The Kingdom of Dahomey () was a West African kingdom located within present-day Benin that existed from approximately 1600 until 1904. Dahomey developed on the Abomey Plateau amongst the Fon people in the early 17th century and became a region ...

at that time.

Although Benin City was retaken by the Nigerians on 22 September, the Biafrans succeeded in their primary objective by tying down as many Nigerian Federal troops as they could. Gen. Gowon also launched an

offensive

Offensive may refer to:

* Offensive, the former name of the Dutch political party Socialist Alternative

* Offensive (military), an attack

* Offensive language

** Fighting words or insulting language, words that by their very utterance inflict inj ...

into Biafra south from the

Niger Delta

The Niger Delta is the delta of the Niger River sitting directly on the Gulf of Guinea on the Atlantic Ocean in Nigeria. It is located within nine coastal southern Nigerian states, which include: all six states from the South South geopolitical ...

to the riverine area, using the bulk of the Lagos Garrison command under Colonel

Benjamin Adekunle

Benjamin Adesanya Maja Adekunle (26 June 1936 – 13 September 2014) was a Nigerian Army Brigadier and Civil War commander.

Early years and background

Adekunle was born in Kaduna. His father was a native of Ogbomosho, while his mother was of the ...

(called the Black Scorpion) to form the 3rd Infantry Division (which was later renamed as the 3rd Marine Commando). As the war continued, the Nigerian Army recruited amongst a wider area, including the

Yoruba

The Yoruba people (, , ) are a West African ethnic group that mainly inhabit parts of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. The areas of these countries primarily inhabited by Yoruba are often collectively referred to as Yorubaland. The Yoruba constitute ...

, Itshekiri, Urhobo, Edo, Ijaw, etc.

Nigerian offensive

The command was divided into two brigades with three battalions each. The 1st Brigade advanced on the axis of the Ogugu–Ogunga–Nsukka road while the 2nd Brigade advanced on the axis of the Gakem–Obudu–Ogoja road. By 10 July 1967, the 1st Brigade had conquered all its assigned territories. By 12 July the 2nd brigade had captured Gakem, Ogudu, and Ogoja. To assist Nigeria, Egypt sent six

Ilyushin Il-28