Beringia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

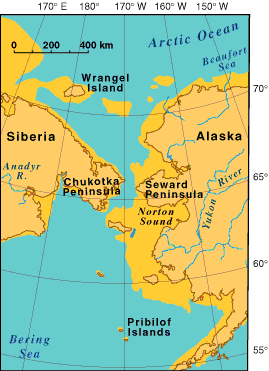

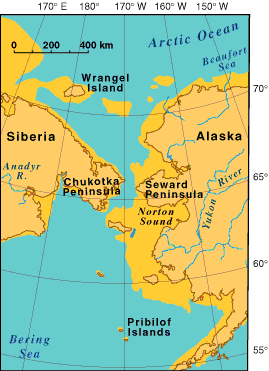

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in

The remains of

The remains of

The last glacial period, commonly referred to as the "Ice Age", spanned 125,000–14,500

The last glacial period, commonly referred to as the "Ice Age", spanned 125,000–14,500

Entering America, Northeast Asia and Beringia Before the Last Glacial Maximum (ed. Madsen DB), pp. 29–61. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press

/ref> Commencing from YBP (

File:ArtemisiaVulgaris.jpg,

The Bering land bridge is a postulated route of

The Bering land bridge is a postulated route of

How primates crossed continents

/ref> By 20 million years ago, evidence in North America shows a further interchange of mammalian species. Some, like the ancient

CBC News: New map of Beringia 'opens your imagination' to what landscape looked like 18,000 years ago

Shared Beringian Heritage Program

Bering Land Bridge National Preserve

includes animation showing the gradual disappearance of the Bering land bridge

Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre

The Fertile Shore

{{Authority control 1930s neologisms Historical geology Ice ages Last Glacial Maximum Pleistocene Paleo-Indian period Natural history of North America Natural history of Asia Prehistory of the Arctic Natural history of Russia Bering Sea Regions of North America North Asia

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

; on the north by 72 degrees north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south by the tip of the Kamchatka Peninsula

The Kamchatka Peninsula (russian: полуостров Камчатка, Poluostrov Kamchatka, ) is a peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of about . The Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk make up the peninsula's eastern and we ...

. It includes the Chukchi Sea, the Bering Sea, the Bering Strait, the Chukchi and Kamchatka Peninsulas in Russia as well as Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and the Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

in Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

.

The area includes land lying on the North American Plate

The North American Plate is a tectonic plate covering most of North America, Cuba, the Bahamas, extreme northeastern Asia, and parts of Iceland and the Azores. With an area of , it is the Earth's second largest tectonic plate, behind the Pacific ...

and Siberian land east of the Chersky Range

The Chersky Range (, ) is a chain of mountains in northeastern Siberia between the Yana River and the Indigirka River. Administratively the area of the range belongs to the Sakha Republic, although a small section in the east is within Magadan ...

. At certain times in prehistory, it formed a land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regression, in which sea leve ...

that was up to wide at its greatest extent and which covered an area as large as British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

and Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

together, totaling approximately . Today, the only land that is visible from the central part of the Bering land bridge are the Diomede Islands

The Diomede Islands (; russian: острова́ Диоми́да, translit=ostrová Diomída), also known in Russia as Gvozdev Islands (russian: острова́ Гво́здева, translit=ostrová Gvozdjeva), consist of two rocky, mesa-like i ...

, the Pribilof Islands

The Pribilof Islands (formerly the Northern Fur Seal Islands; ale, Amiq, russian: Острова Прибылова, Ostrova Pribylova) are a group of four volcanic islands off the coast of mainland Alaska, in the Bering Sea, about north ...

of St. Paul and St. George, St. Lawrence Island

St. Lawrence Island ( ess, Sivuqaq, russian: Остров Святого Лаврентия, Ostrov Svyatogo Lavrentiya) is located west of mainland Alaska in the Bering Sea, just south of the Bering Strait. The village of Gambell, located on t ...

, St. Matthew Island, and King Island.

The term ''Beringia'' was coined by the Swedish botanist Eric Hultén Oskar Eric Gunnar Hultén (18 March 1894 – 1 February 1981) was a Swedish botanist, plant geographer and 20th century explorer of The Arctic. He was born in Halla in Södermanland. He took his licentiate exam 1931 at Stockholm University and ...

in 1937, from the Danish explorer Vitus Bering

Vitus Jonassen Bering (baptised 5 August 1681 – 19 December 1741),All dates are here given in the Julian calendar, which was in use throughout Russia at the time. also known as Ivan Ivanovich Bering, was a Danish cartographer and explorer in ...

. During the ice ages, Beringia, like most of Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

and all of North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and Northeast China

Northeast China or Northeastern China () is a geographical region of China, which is often referred to as "Manchuria" or "Inner Manchuria" by surrounding countries and the West. It usually corresponds specifically to the three provinces east of t ...

, was not glaciated

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as ...

because snowfall was very light. It was a grassland steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate grasslands, ...

, including the land bridge, that stretched for hundreds of kilometres into the continents on either side.

It is believed that a small human population of at most a few thousand arrived in Beringia from eastern Siberia during the Last Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Late Glacial Maximum, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period that ice sheets were at their greatest extent.

Ice sheets covered much of Northern North America, Northern Eur ...

before expanding into the settlement of the Americas

The settlement of the Americas began when Paleolithic hunter-gatherers entered North America from the North Asian Mammoth steppe via the Beringia land bridge, which had formed between northeastern Siberia and western Alaska due to the lowering o ...

sometime after 16,500 years Before Present

Before Present (BP) years, or "years before present", is a time scale used mainly in archaeology, geology and other scientific disciplines to specify when events occurred relative to the origin of practical radiocarbon dating in the 1950s. Becaus ...

(YBP). This would have occurred as the American glaciers blocking the way southward melted, but before the bridge was covered by the sea about 11,000 YBP.

Before European colonization, Beringia was inhabited by the Yupik peoples

The Yupik (plural: Yupiit) (; russian: Юпикские народы) are a group of indigenous or aboriginal peoples of western, southwestern, and southcentral Alaska and the Russian Far East. They are related to the Inuit and Iñupiat. Y ...

on both sides of the straits. This culture remains in the region today along with others. In 2012, the governments of Russia and the United States announced a plan to formally establish "a transboundary area of shared Beringian heritage". Among other things this agreement would establish close ties between the Bering Land Bridge National Preserve and the Cape Krusenstern National Monument

Cape Krusenstern National Monument and the colocated Cape Krusenstern Archeological District is a U.S. National Monument and a National Historic Landmark centered on Cape Krusenstern in northwestern Alaska. The national monument was one of fifte ...

in the United States and Beringia National Park in Russia.

Geography

The remains of

The remains of Late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial Age (geology), age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as Upper Pleistocene from a Stratigraphy, stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division of ...

mammals that had been discovered on the Aleutians

The Aleutian Islands (; ; ale, Unangam Tanangin,”Land of the Aleuts", possibly from Chukchi ''aliat'', "island"), also called the Aleut Islands or Aleutic Islands and known before 1867 as the Catherine Archipelago, are a chain of 14 large vo ...

and islands in the Bering Sea at the close of the nineteenth century indicated that a past land connection might lie beneath the shallow waters between Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

and Chukotka. The underlying mechanism was first thought to be tectonics, but by 1930 changes in the ice mass balance, leading to global sea-level fluctuations were viewed as the cause of the Bering land bridge. In 1937, Eric Hultén Oskar Eric Gunnar Hultén (18 March 1894 – 1 February 1981) was a Swedish botanist, plant geographer and 20th century explorer of The Arctic. He was born in Halla in Södermanland. He took his licentiate exam 1931 at Stockholm University and ...

proposed that around the Aleutians and the Bering Strait region were tundra plants that had originally dispersed from a now-submerged plain between Alaska and Chukotka, which he named Beringia after the Dane Vitus Bering

Vitus Jonassen Bering (baptised 5 August 1681 – 19 December 1741),All dates are here given in the Julian calendar, which was in use throughout Russia at the time. also known as Ivan Ivanovich Bering, was a Danish cartographer and explorer in ...

who had sailed into the strait in 1728. The American arctic geologist David Hopkins redefined Beringia to include portions of Alaska and Northeast Asia. Beringia was later regarded as extending from the Verkhoyansk Mountains

The Verkhoyansk Range (russian: Верхоянский хребет, ''Verkhojanskiy Khrebet''; sah, Үөһээ Дьааҥы сис хайата, ''Üöhee Chaangy sis khaĭata'') is a mountain range in the Sakha Republic, Russia near the settl ...

in the west to the Mackenzie River in the east. The distribution of plants in the genera ''Erythranthe

''Erythranthe'', the monkey-flowers and musk-flowers, is a diverse plant genus with more than 120 members (as of 2022) in the family Phrymaceae. ''Erythranthe'' was originally described as a separate genus, then generally regarded as a section ...

'' and ''Pinus

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden accep ...

'' are good examples of this, as very similar genera members are found in Asia and the Americas.

During the Pleistocene epoch, global cooling led periodically to the expansion of glaciers and the lowering of sea levels. This created land connections in various regions around the globe. Today, the average water depth of the Bering Strait is ; therefore the land bridge opened when the sea level dropped more than below the current level. A reconstruction of the sea-level history of the region indicated that a seaway existed from YBP, a land bridge from YBP, intermittent connection from YBP, a land bridge from YBP, followed by a Holocene sea-level rise that reopened the strait. Post-glacial rebound

Post-glacial rebound (also called isostatic rebound or crustal rebound) is the rise of land masses after the removal of the huge weight of ice sheets during the last glacial period, which had caused isostatic depression. Post-glacial rebound ...

has continued to raise some sections of coast.

During the last glacial period, enough of the earth's water became frozen in the great ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are in Antarctica and Greenland; during the Last Glacial Period at La ...

s covering North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

and Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

to cause a drop in sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardised g ...

s. For thousands of years the sea floors of many interglacial shallow seas were exposed, including those of the Bering Strait, the Chukchi Sea to the north, and the Bering Sea to the south. Other land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regression, in which sea leve ...

s around the world have emerged and disappeared in the same way. Around 14,000 years ago, mainland Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

was linked to both New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

and Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

, the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

became an extension of continental Europe via the dry beds of the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

and North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

, and the dry bed of the South China Sea

The South China Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean. It is bounded in the north by the shores of South China (hence the name), in the west by the Indochinese Peninsula, in the east by the islands of Taiwan and northwestern Phil ...

linked Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

, Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's List ...

, and Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and eas ...

to Indochina

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula or Indochina, is the continental portion of Southeast Asia. It lies east of the Indian subcontinent and south of Mainland China and is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the west an ...

.

Beringian refugium

The last glacial period, commonly referred to as the "Ice Age", spanned 125,000–14,500

The last glacial period, commonly referred to as the "Ice Age", spanned 125,000–14,500YBP

Before Present (BP) years, or "years before present", is a time scale used mainly in archaeology, geology and other scientific disciplines to specify when events occurred relative to the origin of practical radiocarbon dating in the 1950s. Becau ...

and was the most recent glacial period

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betwe ...

within the current ice age

The Late Cenozoic Ice Age,National Academy of Sciences - The National Academies Press - Continental Glaciation through Geologic Times https://www.nap.edu/read/11798/chapter/8#80 or Antarctic Glaciation began 33.9 million years ago at the Eocen ...

, which occurred during the last years of the Pleistocene era. The Ice Age reached its peak during the Last Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Late Glacial Maximum, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period that ice sheets were at their greatest extent.

Ice sheets covered much of Northern North America, Northern Eur ...

, when ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are in Antarctica and Greenland; during the Last Glacial Period at La ...

s began advancing from 33,000YBP and reached their maximum limits 26,500YBP. Deglaciation commenced in the Northern Hemisphere approximately 19,000YBP and in Antarctica approximately 14,500 yearsYBP, which is consistent with evidence that glacial meltwater was the primary source for an abrupt rise in sea level 14,500YBP and the bridge was finally inundated around 11,000 YBP. The fossil evidence from many continents points to the extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

of large animals, termed Pleistocene megafauna

Pleistocene megafauna is the set of large animals that lived on Earth during the Pleistocene epoch. Pleistocene megafauna became extinct during the Quaternary extinction event resulting in substantial changes to ecosystems globally. The role of ...

, near the end of the last glaciation.

During the Ice Age a vast, cold and dry Mammoth steppe

During the Last Glacial Maximum, the mammoth steppe, also known as steppe-tundra, was the Earth's most extensive biome. It spanned from Spain eastward across Eurasia to Canada and from the List of islands in the Arctic Ocean, arctic islands sout ...

stretched from the arctic islands southwards to China, and from Spain eastwards across Eurasia and over the Bering land bridge into Alaska and the Yukon where it was blocked by the Wisconsin glaciation

The Wisconsin Glacial Episode, also called the Wisconsin glaciation, was the most recent glacial period of the North American ice sheet complex. This advance included the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, which nucleated in the northern North American Cord ...

. The land bridge existed because sea-levels were lower because more of the planet's water than today was locked up in glaciers. Therefore, the flora and fauna of Beringia were more related to those of Eurasia rather than North America. Beringia received more moisture and intermittent maritime cloud cover from the north Pacific Ocean than the rest of the Mammoth steppe, including the dry environments on either side of it. This moisture supported a shrub-tundra habitat that provided an ecological refugium for plants and animals. In East Beringia 35,000 YBP, the northern arctic areas experienced temperatures degrees warmer than today but the southern sub-Arctic regions were degrees cooler. During the LGM 22,000 YBP the average summer temperature was degrees cooler than today, with variations of degrees cooler on the Seward Peninsula

The Seward Peninsula is a large peninsula on the western coast of the U.S. state of Alaska whose westernmost point is Cape Prince of Wales. The peninsula projects about into the Bering Sea between Norton Sound, the Bering Strait, the Chukchi ...

to cooler in the Yukon. In the driest and coldest periods of the Late Pleistocene, and possibly during the entire Pleistocene, moisture occurred along a north–south gradient with the south receiving the most cloud cover and moisture due to the air-flow from the North Pacific.

In the Late Pleistocene, Beringia was a mosaic of biological communities.Hoffecker JF, Elias SA. 2007 Human ecology of Beringia. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.Elias SA, Crocker B. 2008 The Bering land bridge: a moisture barrier to the dispersal of steppe-tundra biota? Q. Sci. Rev. 27, 2473–83Brigham-Grette J, Lozhkin AV, Anderson PM, Glushkova OY. 2004 Paleoenvironmental conditions in Western Beringia before and during the Last Glacial Maximum. IEntering America, Northeast Asia and Beringia Before the Last Glacial Maximum (ed. Madsen DB), pp. 29–61. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press

/ref> Commencing from YBP (

MIS

MIS or mis may refer to:

Science and technology

* Management information system

* Marine isotope stage, stages of the Earth's climate

* Maximal independent set, in graph theory

* Metal-insulator-semiconductor, e.g., in MIS capacitor

* Minimally ...

3), steppe–tundra vegetation dominated large parts of Beringia with a rich diversity of grasses and herbs.Sher AV, Kuzmina SA, Kuznetsova TV, Sulerzhitsky LD. 2005 New insights into the Weichselian environment and climate of the East Siberian Arctic, derived from fossil insects, plants, and mammals. Q. Sci. Rev. 24, 533–69. There were patches of shrub tundra with isolated refugia of larch

Larches are deciduous conifers in the genus ''Larix'', of the family Pinaceae (subfamily Laricoideae). Growing from tall, they are native to much of the cooler temperate northern hemisphere, on lowlands in the north and high on mountains furt ...

(''Larix'') and spruce (''Picea'') forests with birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech-oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 30 ...

(''Betula'') and alder

Alders are trees comprising the genus ''Alnus'' in the birch family Betulaceae. The genus comprises about 35 species of monoecious trees and shrubs, a few reaching a large size, distributed throughout the north temperate zone with a few sp ...

(''Alnus'') trees. It has been proposed that the largest and most diverse megafaunal community residing in Beringia at this time could only have been sustained in a highly diverse and productive environment. Analysis at Chukotka on the Siberian edge of the land bridge indicated that from YBP (MIS 3 to MIS 2) the environment was wetter and colder than the steppe–tundra to the east and west, with warming in parts of Beringia from YBP. These changes provided the most likely explanation for mammal migrations after YBP, as the warming provided increased forage for browsers and mixed feeders. Beringia did not block the movement of most dry steppe-adapted large species such as saiga antelope, woolly mammoth, and caballid horses. However, from the west, the woolly rhino

The woolly rhinoceros (''Coelodonta antiquitatis'') is an extinct species of rhinoceros that was common throughout Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene epoch and survived until the end of the last glacial period. The woolly rhinoceros was a me ...

went no further east than the Anadyr River

The Anadyr (russian: Ана́дырь; Yukaghir: Онандырь; ckt, Йъаайваам) is a river in the far northeast of Siberia which flows into the Gulf of Anadyr of the Bering Sea and drains much of the interior of Chukotka Autonomous ...

, and from the east North American camels, the American kiang

The kiang (''Equus kiang'') is the largest of the '' Asinus'' subgenus. It is native to the Tibetan Plateau, where it inhabits montane and alpine grasslands. Its current range is restricted to the plains of the Tibetan plateau; Ladakh; and nort ...

-like equids, the short-faced bear

The Tremarctinae or short-faced bears is a subfamily of Ursidae that contains one living representative, the spectacled bear (''Tremarctos ornatus'') of South America, and several extinct species from four genera: the Florida spectacled bear ('' ...

, bonnet-headed muskoxen, and American badger

The American badger (''Taxidea taxus'') is a North American badger similar in appearance to the European badger, although not closely related. It is found in the western, central, and northeastern United States, northern Mexico, and south-cent ...

did not travel west. At the beginning of the Holocene, some mesic habitat

In ecology, a mesic habitat is a type of habitat with a moderate or well-balanced supply of moisture, e.g., a mesic forest, a temperate hardwood forest, or dry-mesic prairie. Mesic habitats transition to xeric shrublands in a non-linear fashion, ...

-adapted species left the refugium and spread westward into what had become tundra-vegetated northern Asia and eastward into northern North America.

The latest emergence of the land bridge was years ago. However, from YBP the Laurentide Ice Sheet

The Laurentide Ice Sheet was a massive sheet of ice that covered millions of square miles, including most of Canada and a large portion of the Northern United States, multiple times during the Quaternary glacial epochs, from 2.58 million years a ...

fused with the Cordilleran Ice Sheet, which blocked gene flow between Beringia (and Eurasia) and continental North America. The Yukon corridor opened between the receding ice sheets YBP, and this once again allowed gene flow between Eurasia and continental North America until the land bridge was finally closed by rising sea levels YBP. During the Holocene, many mesic-adapted species left the refugium and spread eastward and westward, while at the same time the forest-adapted species spread with the forests up from the south. The arid adapted species were reduced to minor habitats or became extinct.

Beringia constantly transformed its ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syste ...

as the changing climate affected the environment, determining which plants and animals were able to survive. The land mass could be a barrier as well as a bridge: during colder periods, glaciers advanced and precipitation levels dropped. During warmer intervals, clouds, rain and snow altered soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support life. Some scientific definitions distinguish ''dirt'' from ''soil'' by restricting the former te ...

s and drainage patterns. Fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

remains show that spruce, birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech-oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 30 ...

and poplar once grew beyond their northernmost range today, indicating that there were periods when the climate was warmer and wetter. The environmental conditions were not homogenous in Beringia. Recent stable isotope

The term stable isotope has a meaning similar to stable nuclide, but is preferably used when speaking of nuclides of a specific element. Hence, the plural form stable isotopes usually refers to isotopes of the same element. The relative abundanc ...

studies of woolly mammoth

The woolly mammoth (''Mammuthus primigenius'') is an extinct species of mammoth that lived during the Pleistocene until its extinction in the Holocene epoch. It was one of the last in a line of mammoth species, beginning with '' Mammuthus subp ...

bone collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix found in the body's various connective tissues. As the main component of connective tissue, it is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up from 25% to 35% of the whole ...

demonstrate that western Beringia (Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

) was colder and drier than eastern Beringia (Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

and Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

), which was more ecologically diverse. Mastodon

A mastodon ( 'breast' + 'tooth') is any proboscidean belonging to the extinct genus ''Mammut'' (family Mammutidae). Mastodons inhabited North and Central America during the late Miocene or late Pliocene up to their extinction at the end of th ...

s, which depended on shrubs for food, were uncommon in the open dry tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless moun ...

landscape characteristic of Beringia during the colder periods. In this tundra, mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus'', one of the many genera that make up the order of trunked mammals called proboscideans. The various species of mammoth were commonly equipped with long, curved tusks and, ...

s flourished instead.

The extinct pine species ''Pinus matthewsii

''Pinus matthewsii'' is an extinction, extinct species of conifer in the pine family. The species is solely known from the Pliocene sediments exposed at Ch’ijee's Bluff on the Porcupine River near Old Crow, Yukon, Canada.

Type locality

''Pinu ...

'' has been described from Pliocene sediments in the Yukon areas of the refugium.

The paleo-environment changed across time. Below is a gallery of some of the plants that inhabited eastern Beringia before the beginning of the Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togethe ...

.

Artemisia

Artemisia may refer to:

People

* Artemisia I of Caria (fl. 480 BC), queen of Halicarnassus under the First Persian Empire, naval commander during the second Persian invasion of Greece

* Artemisia II of Caria (died 350 BC), queen of Caria under th ...

File:Carex halleriana.jpg, Cyperaceae

The Cyperaceae are a family of graminoid (grass-like), monocotyledonous flowering plants known as sedges. The family is large, with some 5,500 known species described in about 90 genera, the largest being the "true sedges" genus ''Carex'' w ...

(sedges

The Cyperaceae are a family of graminoid (grass-like), monocotyledonous flowering plants known as sedges. The family is large, with some 5,500 known species described in about 90 genera, the largest being the "true sedges" genus ''Carex'' wit ...

)

File:Grassflowers.jpg, Gramineae

Poaceae () or Gramineae () is a large and nearly ubiquitous family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos and the grasses of natural grassland and species cultivated in lawns and ...

(grasses

Poaceae () or Gramineae () is a large and nearly ubiquitous family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos and the grasses of natural grassland and species cultivated in lawns and ...

)

File:Salix-lanata-total.JPG, Salix

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, from the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 400 speciesMabberley, D.J. 1997. The Plant Book, Cambridge University Press #2: Cambridge. of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist so ...

(willow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, from the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 400 speciesMabberley, D.J. 1997. The Plant Book, Cambridge University Press #2: Cambridge. of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist s ...

)

Gray wolf

The earliest ''Canis lupus'' specimen was a fossil tooth discovered atOld Crow, Yukon

Old Crow is a community in the Canadian territory of Yukon.

Located in a periglacial environment, the community is situated on the Porcupine River in the far northern part of the territory. Old Crow is the only Yukon community that cannot be rea ...

, Canada. The specimen was found in sediment dated 1 million YBP, however the geological attribution of this sediment is questioned. Slightly younger specimens were discovered at Cripple Creek Sump, Fairbanks

Fairbanks is a home rule city and the borough seat of the Fairbanks North Star Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. Fairbanks is the largest city in the Interior region of Alaska and the second largest in the state. The 2020 Census put the po ...

, Alaska, in strata dated 810,000 YBP. Both discoveries point to an origin of these wolves in eastern Beringia during the Middle Pleistocene

The Chibanian, widely known by its previous designation of Middle Pleistocene, is an age in the international geologic timescale or a stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. The ...

. Grey wolves suffered a species-wide population bottleneck

A population bottleneck or genetic bottleneck is a sharp reduction in the size of a population due to environmental events such as famines, earthquakes, floods, fires, disease, and droughts; or human activities such as specicide, widespread violen ...

(reduction) approximately 25,000 YBP during the Last Glacial Maximum. This was followed by a single population of modern wolves expanding out of their Beringia refuge to repopulate the wolf's former range, replacing the remaining Late Pleistocene wolf populations across Eurasia and North America as they did so.

Human habitation

The Bering land bridge is a postulated route of

The Bering land bridge is a postulated route of human migration

Human migration is the movement of people from one place to another with intentions of settling, permanently or temporarily, at a new location (geographic region). The movement often occurs over long distances and from one country to another (ex ...

to the Americas from Asia about 20,000 years ago. An open corridor

Corridor or The Corridor may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

Films

* ''The Corridor'' (1968 film), a 1968 Swedish drama film

* ''The Corridor'' (1995 film), a 1995 Lithuanian drama film

* ''The Corridor'' (2010 film), a 2010 Canadia ...

through the ice-covered North American Arctic was too barren to support human migrations before around 12,600 YBP. A study has indicated that the genetic imprints of only 70 of all the individuals who settled and traveled the land bridge into North America are visible in modern descendants. This genetic bottleneck finding is an example of the founder effect

In population genetics, the founder effect is the loss of genetic variation that occurs when a new population is established by a very small number of individuals from a larger population. It was first fully outlined by Ernst Mayr in 1942, using ...

and does not imply that only 70 individuals crossed into North America at the time; rather, the genetic material of these individuals became amplified in North America following isolation from other Asian populations.

Seagoing coastal settlers may also have crossed much earlier, but there is no scientific consensus

Scientific consensus is the generally held judgment, position, and opinion of the majority or the supermajority of scientists in a particular field of study at any particular time.

Consensus is achieved through scholarly communication at confe ...

on this point, and the coastal sites that would offer further information now lie submerged in up to a hundred metres of water offshore. Land animals migrated through Beringia as well, introducing to North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

species that had evolved in Asia, like mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

s such as proboscidea

The Proboscidea (; , ) are a taxonomic order of afrotherian mammals containing one living family (Elephantidae) and several extinct families. First described by J. Illiger in 1811, it encompasses the elephants and their close relatives. From ...

ns and American lion

''Panthera atrox'', better known as the American lion, also called the North American lion, or American cave lion, is an extinct pantherine cat that lived in North America during the Pleistocene epoch and the early Holocene epoch, about 340,0 ...

s, which evolved

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation t ...

into now-extinct endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found elsew ...

North American species. Meanwhile, equids

Equidae (sometimes known as the horse family) is the taxonomic family of horses and related animals, including the extant horses, asses, and zebras, and many other species known only from fossils. All extant species are in the genus '' Equus'', w ...

and camelid

Camelids are members of the biological family Camelidae, the only currently living family in the suborder Tylopoda. The seven extant members of this group are: dromedary camels, Bactrian camels, wild Bactrian camels, llamas, alpacas, vicuñas, ...

s that had evolved in North America (and later became extinct there) migrated into Asia as well at this time.

A 2007 analysis of mtDNA found evidence that a human population lived in genetic isolation on the exposed Beringian landmass during the Last Glacial Maximum for approximately 5,000 years. This population is often referred to as the Beringian Standstill population. A number of other studies, relying on more extensive genomic data, have come to the same conclusion. Genetic and linguistic data demonstrate that at the end of the Last Glacial Maximum

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Late Glacial Maximum, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period that ice sheets were at their greatest extent.

Ice sheets covered much of Northern North America, Northern Eur ...

, as sea levels rose, some members of the Beringian Standstill Population migrated back into eastern Asia while others migrated into the Western Hemisphere, where they became the ancestors of the indigenous people of the Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the antimeridian. The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Politically, the term We ...

. Environmental selection on this Beringian Standstill Population has been suggested for genetic variation in the Fatty Acid Desaturase

A fatty acid desaturase is an enzyme that removes two hydrogen atoms from a fatty acid, creating a carbon/carbon double bond. These desaturases are classified as:

* Delta - indicating that the double bond is created at a fixed position from the ...

gene cluster and the ectodysplasin A receptor

Ectodysplasin A receptor (EDAR) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the EDAR gene. EDAR is a cell surface receptor for ectodysplasin A which plays an important role in the development of ectodermal tissues such as the skin. It is structural ...

gene. Using Y Chromosome data Pinotti et al. have estimated the Beringian Standstill to be less than 4600 years and taking place between 19.5 kya and 15 kya.

Previous connections

Biogeographical

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, i ...

evidence demonstrates previous connections between North America and Asia. Similar dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

fossils occur both in Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

and in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

. For instance the dinosaur ''Saurolophus

''Saurolophus'' (; meaning "lizard crest") is a genus of large hadrosaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous period of Asia and North America, that lived in what is now the Horseshoe Canyon and Nemegt formations about 70 million to 68 million ...

'' was found in both Mongolia and western North America. Relatives of ''Troodon

''Troodon'' ( ; ''Troödon'' in older sources) is a wastebasket taxon and a dubious genus of relatively small, bird-like dinosaurs known definitively from the Campanian age of the Late Cretaceous period (about 77 mya). It includes at least ...

'', ''Triceratops

''Triceratops'' ( ; ) is a genus of herbivore, herbivorous Chasmosaurinae, chasmosaurine Ceratopsidae, ceratopsid dinosaur that first appeared during the late Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous Period (geology), period, about 68 m ...

'', and even ''Tyrannosaurus

''Tyrannosaurus'' is a genus of large theropoda, theropod dinosaur. The species ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' (''rex'' meaning "king" in Latin), often called ''T. rex'' or colloquially ''T-Rex'', is one of the best represented theropods. ''Tyrannosa ...

rex'' all came from Asia.

Fossil evidence indicates an exchange of primates between North America and Asia around 55.8 million years ago./ref> By 20 million years ago, evidence in North America shows a further interchange of mammalian species. Some, like the ancient

saber-toothed cat

Machairodontinae is an extinct subfamily of carnivoran mammals of the family Felidae (true cats). They were found in Asia, Africa, North America, South America, and Europe from the Miocene to the Pleistocene, living from about 16 million until ...

s, have a recurring geographical range: Europe, Africa, Asia, and North America. The only way they could reach the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

was by the Bering land bridge. Had this bridge not existed at that time, the fauna of the world would be very different.

See also

*Ancient Beringian

The Ancient Beringians (AB) is a specific archaeogenetic lineage, based on the genome of an infant found at the Upward Sun River site (dubbed USR1), dated to 11,500 years ago. The AB lineage diverged from the '' Ancestral Native American'' (ANA) ...

* Bering Strait crossing

A Bering Strait crossing is a hypothetical bridge or tunnel that would span the relatively narrow and shallow Bering Strait between the Chukotka Peninsula in Russia and the Seward Peninsula in the U.S. state of Alaska. The crossing would prov ...

* Bluefish Caves

Bluefish Caves is an archaeological site in Yukon, Canada, located southwest of the Vuntut Gwichin community of Old Crow, from which a jaw bone of a Yukon horse has been radiocarbon dated to 24,000 years before present (BP). There are three smal ...

* Little John (archeological site)

* Geologic time scale

The geologic time scale, or geological time scale, (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochrono ...

* Last glacial period

* Paleoshoreline

A paleoshoreline (ancient shoreline) is a shoreline which existed in the geologic past. (''Paleo'' is from an ancient Greek word meaning "old" or "ancient".) A perched coastline is an ancient (fossil) shoreline positioned above the present shor ...

* Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

* Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre

The Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre is a research and exhibition facility located at km 1423 (Mile 886) on the Alaska Highway in Whitehorse, Yukon, which opened in 1997. The focus of the interpretive centre is the story of Beringia, the 3200&n ...

References

Further reading

* Demuth, Bathsheba (2019) '' Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait''. W. W. Norton & Company. . * * * * * Pielou, E. C., ''After the Ice Age: The Return of Life to Glaciated North America'' (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) 1992 *External links

CBC News: New map of Beringia 'opens your imagination' to what landscape looked like 18,000 years ago

Shared Beringian Heritage Program

Bering Land Bridge National Preserve

includes animation showing the gradual disappearance of the Bering land bridge

Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre

The Fertile Shore

{{Authority control 1930s neologisms Historical geology Ice ages Last Glacial Maximum Pleistocene Paleo-Indian period Natural history of North America Natural history of Asia Prehistory of the Arctic Natural history of Russia Bering Sea Regions of North America North Asia