Battle Of The Wilderness on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of the Wilderness was fought on May 5–7, 1864, during the

Grant believed that the eastern and western Union armies were too uncoordinated in their actions, and that the previous practice of conquering and guarding new territories required too many resources. Grant's new strategy was to attack with all forces at the same time, making it difficult for the Confederates to transfer forces from one battlefront to another. His objective was to destroy the Confederate armies rather than conquering territory. The two largest Confederate armies became the two major targets, and they were

Grant believed that the eastern and western Union armies were too uncoordinated in their actions, and that the previous practice of conquering and guarding new territories required too many resources. Grant's new strategy was to attack with all forces at the same time, making it difficult for the Confederates to transfer forces from one battlefront to another. His objective was to destroy the Confederate armies rather than conquering territory. The two largest Confederate armies became the two major targets, and they were

The Wilderness is located south of the Rapidan River in Virginia's Spotsylvania County and Orange County. Its southern border is Spotsylvania Court House, and western border is usually considered the Rapidan River tributary Mine Run. Its eastern border is less definite, causing estimates of the size of the Wilderness to vary. While the maximum area for the Wilderness is to , historians discussing the battles fought there typically use . At the time of the battle, the region was a "patchwork of open areas and vegetation of varying density." Much of the vegetation was a dense second-growth forest consisting of small trees, bushes, shrubs, and

The Wilderness is located south of the Rapidan River in Virginia's Spotsylvania County and Orange County. Its southern border is Spotsylvania Court House, and western border is usually considered the Rapidan River tributary Mine Run. Its eastern border is less definite, causing estimates of the size of the Wilderness to vary. While the maximum area for the Wilderness is to , historians discussing the battles fought there typically use . At the time of the battle, the region was a "patchwork of open areas and vegetation of varying density." Much of the vegetation was a dense second-growth forest consisting of small trees, bushes, shrubs, and

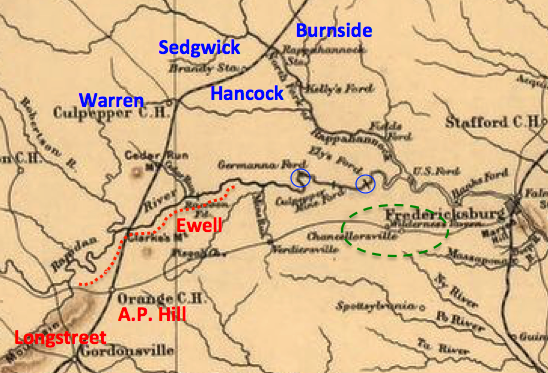

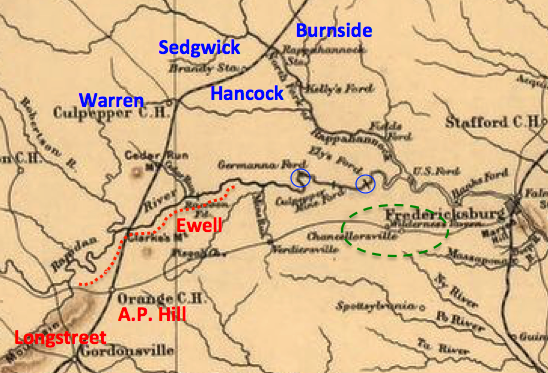

On May 2, Lee met with his generals on Clark Mountain, obtaining a panoramic view of the Union camps. He realized that Grant was getting ready to attack, but did not know the precise route of advance. He predicted (correctly) that Grant would cross to the east of the Confederate fortifications on the Rapidan, using the Germanna and Ely Fords, but he could not be certain.

To retain flexibility of response, Lee had dispersed his Army over a wide area. Longstreet's First Corps was around Gordonsville, from where they had the flexibility to respond by railroad to potential threats to the Shenandoah Valley or to Richmond. Hill's Third Corps was outside Orange Court House. Ewell's Second Corps was near Morton's Ford and Mine Run, northeast of Hill. Stuart's cavalry was scattered further south from Gordonsville to Fredericksburg.

On May 2, Lee met with his generals on Clark Mountain, obtaining a panoramic view of the Union camps. He realized that Grant was getting ready to attack, but did not know the precise route of advance. He predicted (correctly) that Grant would cross to the east of the Confederate fortifications on the Rapidan, using the Germanna and Ely Fords, but he could not be certain.

To retain flexibility of response, Lee had dispersed his Army over a wide area. Longstreet's First Corps was around Gordonsville, from where they had the flexibility to respond by railroad to potential threats to the Shenandoah Valley or to Richmond. Hill's Third Corps was outside Orange Court House. Ewell's Second Corps was near Morton's Ford and Mine Run, northeast of Hill. Stuart's cavalry was scattered further south from Gordonsville to Fredericksburg.

On May 4, 1864, the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River at three places and converged on the Wilderness of Spotsylvania in east central Virginia.

On May 4, 1864, the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River at three places and converged on the Wilderness of Spotsylvania in east central Virginia.

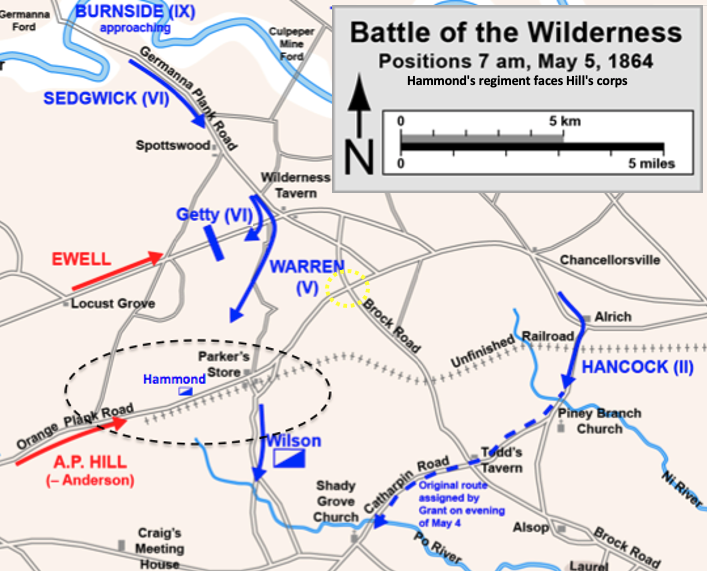

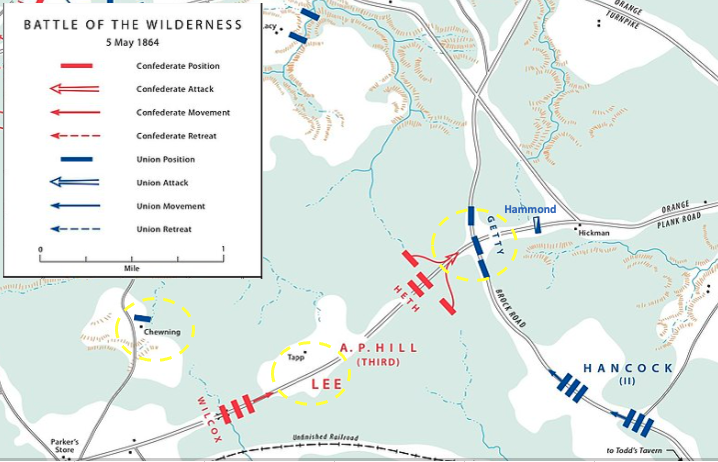

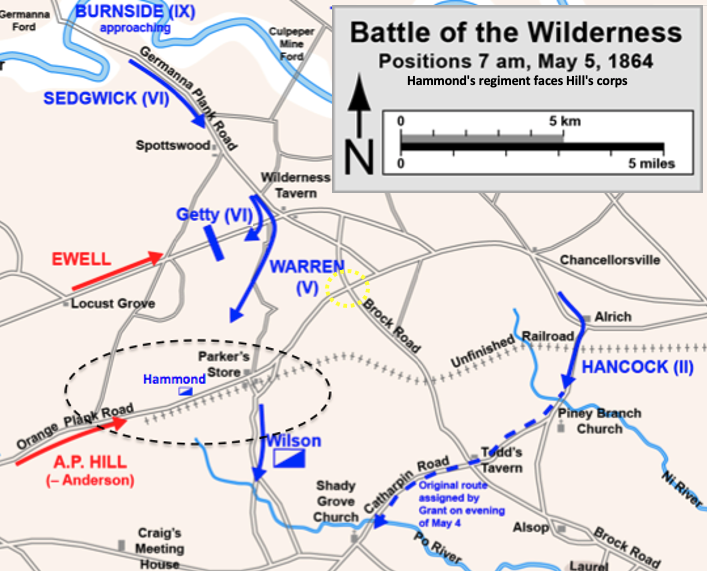

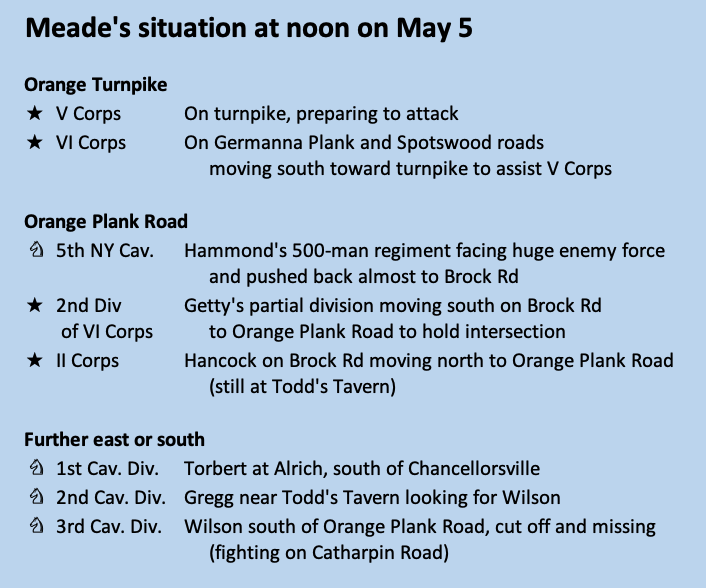

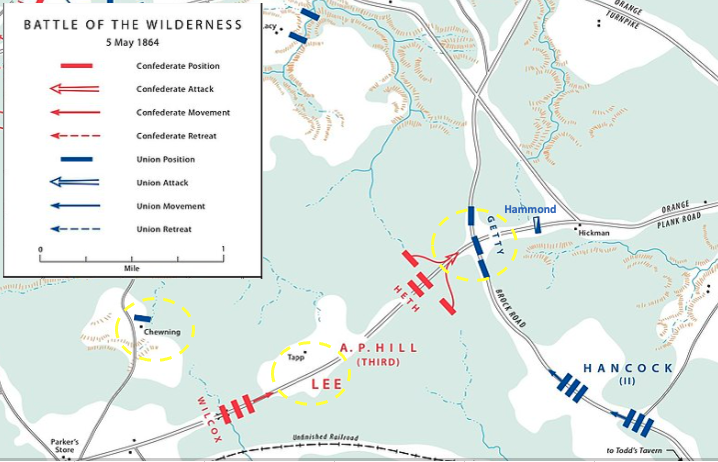

At 5:00 am on May 5, Wilson's Division proceeded southward from Parker's Store. The 5th New York Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John Hammond, was detached and instructed to patrol west of the Parker's Store area until relieved by Warren's V Corps. A probe west on the Orange Plank Road discovered Confederate soldiers. Despite being reinforced, the Union probe was driven back toward Parker's Store. It was soon discovered that they were fighting infantry from most of Hill's Third Corps.

Hammond's total force consisted of only about 500 men. Hammond understood that the dense woods and the large infantry force made fighting on horseback inadvisable. The command fought dismounted and spread out as a skirmish line while utilizing their Spencer repeating rifles. The regiment slowly retreated east, moving toward and beyond Parker's Store on the Orange Plank Road. Once the Confederates advanced east of Parker's Store, the remainder of Wilson's cavalry division was cut off from Meade and Warren's VICorps.

At 5:00 am on May 5, Wilson's Division proceeded southward from Parker's Store. The 5th New York Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John Hammond, was detached and instructed to patrol west of the Parker's Store area until relieved by Warren's V Corps. A probe west on the Orange Plank Road discovered Confederate soldiers. Despite being reinforced, the Union probe was driven back toward Parker's Store. It was soon discovered that they were fighting infantry from most of Hill's Third Corps.

Hammond's total force consisted of only about 500 men. Hammond understood that the dense woods and the large infantry force made fighting on horseback inadvisable. The command fought dismounted and spread out as a skirmish line while utilizing their Spencer repeating rifles. The regiment slowly retreated east, moving toward and beyond Parker's Store on the Orange Plank Road. Once the Confederates advanced east of Parker's Store, the remainder of Wilson's cavalry division was cut off from Meade and Warren's VICorps.

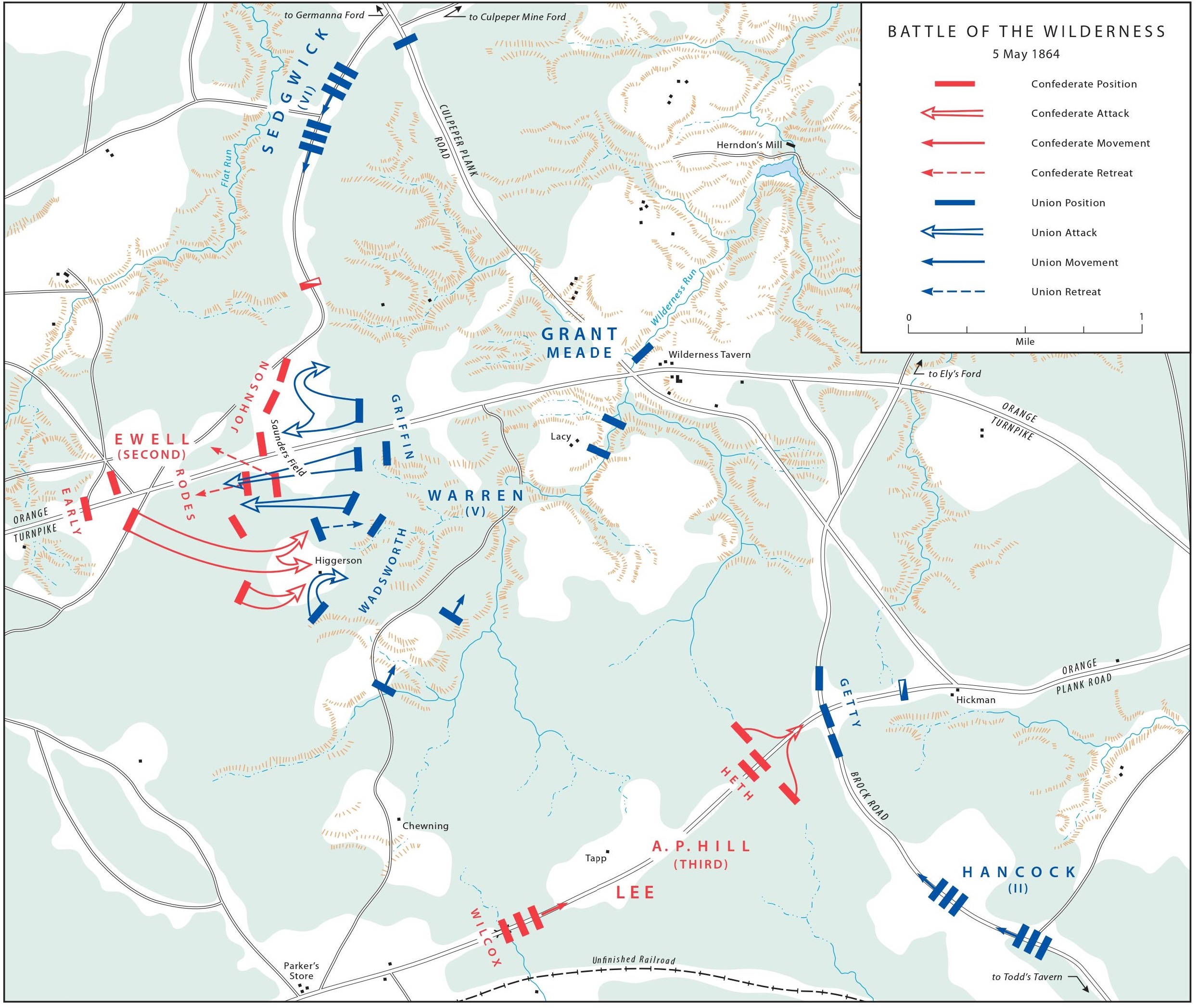

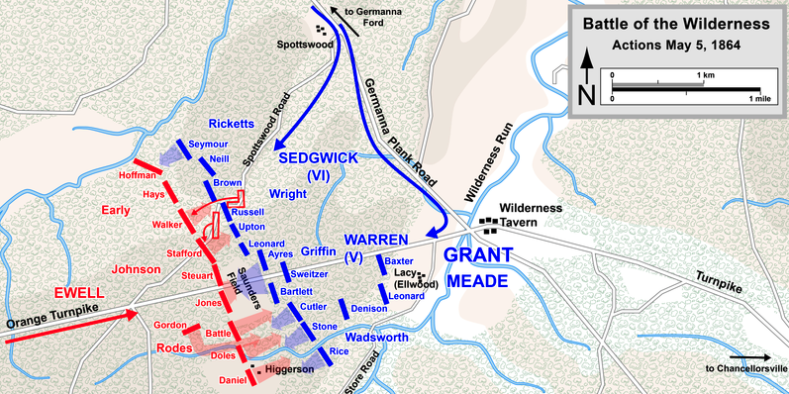

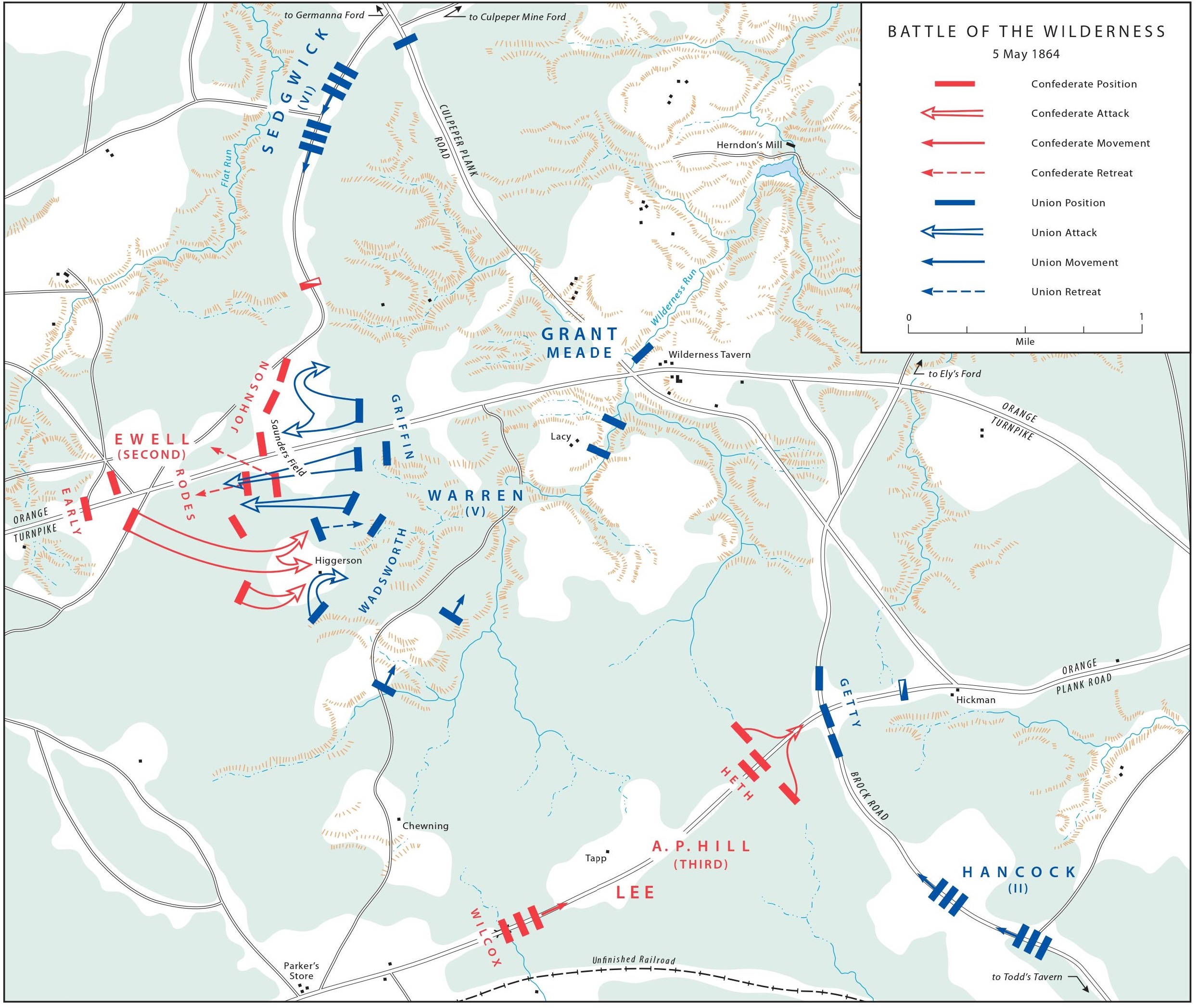

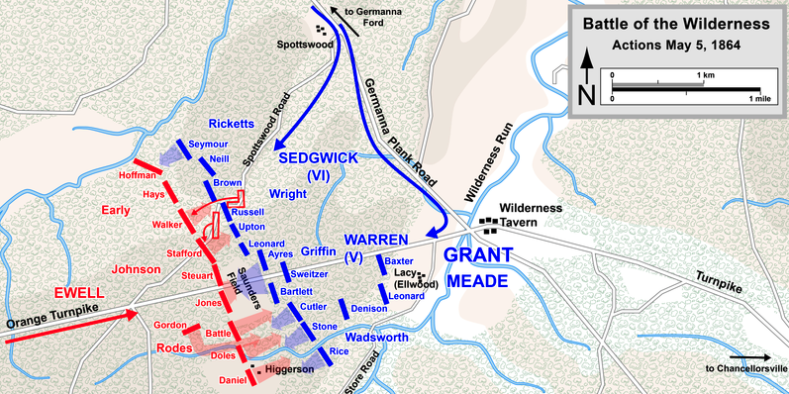

At 6:00am on May 5, Warren's V Corps began moving south over farm lanes toward the Parker's Store. The Confederate infantry was observed in the west near the Orange Turnpike, and Meade was notified. Grant instructed "If any opportunity presents itself of pitching into a part of Lee's army, do so without giving time for disposition." Meade halted his army and directed Warren to attack, assuming that the Confederates were a division and not an entire infantry corps. Hancock was held at Todd's tavern. Although Meade told Grant that the threat was probably a delaying tactic without the intent to give battle, he stopped his entire army—the exact thing Lee wanted him to do. The Confederate force was Ewell's Second Corps, and his men erected earthworks on the western end of the clearing known as Saunders Field. Ewell's instructions from Lee were to not advance too fast, since his corps was out of the reach of Hill's Third Corps—and Longstreet's First Corps was not yet at the battlefield.

At 6:00am on May 5, Warren's V Corps began moving south over farm lanes toward the Parker's Store. The Confederate infantry was observed in the west near the Orange Turnpike, and Meade was notified. Grant instructed "If any opportunity presents itself of pitching into a part of Lee's army, do so without giving time for disposition." Meade halted his army and directed Warren to attack, assuming that the Confederates were a division and not an entire infantry corps. Hancock was held at Todd's tavern. Although Meade told Grant that the threat was probably a delaying tactic without the intent to give battle, he stopped his entire army—the exact thing Lee wanted him to do. The Confederate force was Ewell's Second Corps, and his men erected earthworks on the western end of the clearing known as Saunders Field. Ewell's instructions from Lee were to not advance too fast, since his corps was out of the reach of Hill's Third Corps—and Longstreet's First Corps was not yet at the battlefield.

Warren approached the eastern end of Saunders Field with the division of Brigadier General Charles Griffin along the road on the right and the division of Brigadier General James S. Wadsworth on the left. Brigadier General Samuel W. Crawford's division was too far away on the left near Chewning Farm, and the division of Brigadier General John C. Robinson was in reserve closer to Wilderness Tavern. It took time to align Warren's divisions, and there was some concern about Griffin's northern (right) flank. A major problem was that "once a division left the roads or fields it disappeared utterly, and its commander could not tell whether it was in line with the others...." Brigadier General Horatio Wright's 1st Division from Sedgwick's VI Corps began to move south on the Germanna Plank Road to Spotswood Road to protect Warren's right. Warren requested a delay from attacking to wait for Wright. By 12:00pm, Meade was frustrated by the delay and ordered Warren to attack before Sedgwick's VI Corps could arrive. Warren's troops arrived at Saunders Field around 1:00pm. The Confederate division of Major General Edward Johnson was positioned on the Orange Turnpike west of Sanders Field, and it also guarded the Spotswood Road route of Sedgwick. Behind Johnson and further south was the division of Major General Robert E. Rodes, while the division of Major General Jubal Early waited further west in reserve.

Warren approached the eastern end of Saunders Field with the division of Brigadier General Charles Griffin along the road on the right and the division of Brigadier General James S. Wadsworth on the left. Brigadier General Samuel W. Crawford's division was too far away on the left near Chewning Farm, and the division of Brigadier General John C. Robinson was in reserve closer to Wilderness Tavern. It took time to align Warren's divisions, and there was some concern about Griffin's northern (right) flank. A major problem was that "once a division left the roads or fields it disappeared utterly, and its commander could not tell whether it was in line with the others...." Brigadier General Horatio Wright's 1st Division from Sedgwick's VI Corps began to move south on the Germanna Plank Road to Spotswood Road to protect Warren's right. Warren requested a delay from attacking to wait for Wright. By 12:00pm, Meade was frustrated by the delay and ordered Warren to attack before Sedgwick's VI Corps could arrive. Warren's troops arrived at Saunders Field around 1:00pm. The Confederate division of Major General Edward Johnson was positioned on the Orange Turnpike west of Sanders Field, and it also guarded the Spotswood Road route of Sedgwick. Behind Johnson and further south was the division of Major General Robert E. Rodes, while the division of Major General Jubal Early waited further west in reserve.

By the time the Union line arrived near the enemy, it had numerous gaps and some regiments faced north instead of west. The concerns about Warren's right flank were justified. As Griffin's division advanced, Ayres's brigade held the right but had difficulty maintaining its lines in a "blizzard of lead". They received enfilading fire on their right from the brigade of Confederate

By the time the Union line arrived near the enemy, it had numerous gaps and some regiments faced north instead of west. The concerns about Warren's right flank were justified. As Griffin's division advanced, Ayres's brigade held the right but had difficulty maintaining its lines in a "blizzard of lead". They received enfilading fire on their right from the brigade of Confederate

Visibility was limited near Orange Plank Road, and officers had difficulty controlling men and maintaining formations. Attackers would move blindly and noisily forward, becoming targets for concealed defenders. Unable to duplicate the surprise that was achieved by Ewell on the Turnpike, A.P. Hill's approach was detected from the Chewning farm location of Crawford's 3rd Division of the V Corps. Crawford notified Meade, and his message arrived at Meade's headquarters around 10:15am.

Crawford sent the

Visibility was limited near Orange Plank Road, and officers had difficulty controlling men and maintaining formations. Attackers would move blindly and noisily forward, becoming targets for concealed defenders. Unable to duplicate the surprise that was achieved by Ewell on the Turnpike, A.P. Hill's approach was detected from the Chewning farm location of Crawford's 3rd Division of the V Corps. Crawford notified Meade, and his message arrived at Meade's headquarters around 10:15am.

Crawford sent the

Leaving Hammond's regiment at Parker's Store at 5:00am on May 5, Wilson moved his two brigades south. His Second Brigade led the way, and it was commanded by Colonel George H. Chapman. His First Brigade was commanded by Colonel Timothy M. Bryan. Chapman reached Catharpin Road and moved west beyond Craig's Meeting House, where he found 1,000 men from a Confederate cavalry brigade commanded by Brigadier General Thomas L. Rosser. After initially driving Rosser back, both of Wilson's brigades fled east after finding Hill's infantry on their north side and Rosser's cavalry on the Catharpin Road on their south side. The

Leaving Hammond's regiment at Parker's Store at 5:00am on May 5, Wilson moved his two brigades south. His Second Brigade led the way, and it was commanded by Colonel George H. Chapman. His First Brigade was commanded by Colonel Timothy M. Bryan. Chapman reached Catharpin Road and moved west beyond Craig's Meeting House, where he found 1,000 men from a Confederate cavalry brigade commanded by Brigadier General Thomas L. Rosser. After initially driving Rosser back, both of Wilson's brigades fled east after finding Hill's infantry on their north side and Rosser's cavalry on the Catharpin Road on their south side. The

During the night, Ewell placed his artillery on his extreme left and on both sides of the Orange Turnpike. He also had an abatis in front of his trenchline. He attacked Sedgwick on the north side of the turnpike at 4:45am. His line moved forward and then back on multiple occasions, and some ground was fought over as much as five times.

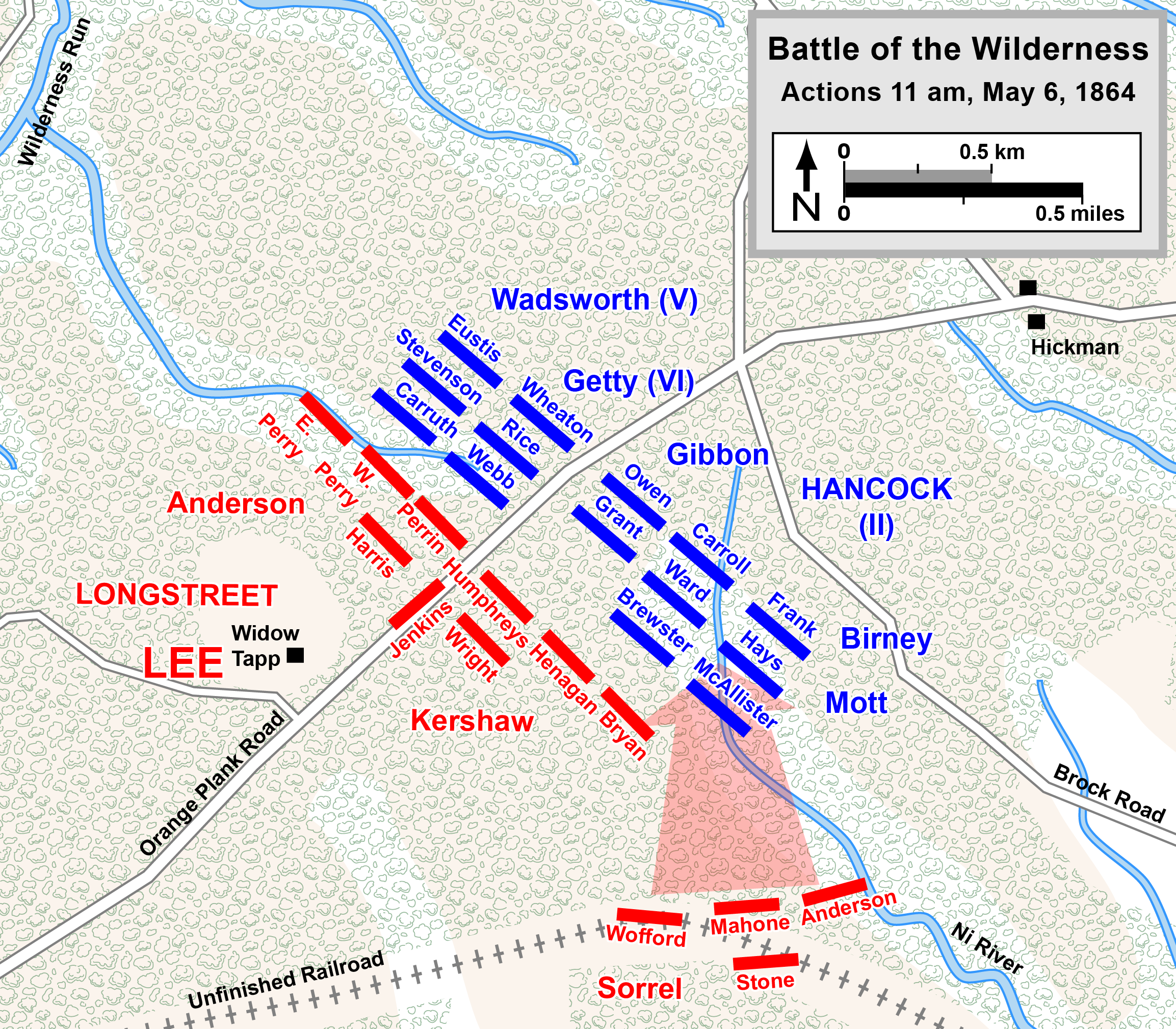

To the south on the Orange Plank Road, Hancock's II Corps with Getty's Division attacked Hill at 5:00am, overwhelming the ill-prepared Third Corps in concert with Wadsworth. Following Hill's orders, Lieutenant Colonel

During the night, Ewell placed his artillery on his extreme left and on both sides of the Orange Turnpike. He also had an abatis in front of his trenchline. He attacked Sedgwick on the north side of the turnpike at 4:45am. His line moved forward and then back on multiple occasions, and some ground was fought over as much as five times.

To the south on the Orange Plank Road, Hancock's II Corps with Getty's Division attacked Hill at 5:00am, overwhelming the ill-prepared Third Corps in concert with Wadsworth. Following Hill's orders, Lieutenant Colonel

Starting from near Poague's guns, Longstreet counterattacked with the divisions of Major General Charles W. Field on the left and Brigadier General Joseph B. Kershaw on the right. A series of attacks by both sides caused the front line to move back and forth between the Widow Tapp farm and Brock Road. The Texans leading the charge north of the road fought gallantly at a heavy price—only 250 of the 800 men emerged unscathed. Field's Division drove back Wadsworth's force on the north side of the Widow Tapp Farm, while Kershaw's Division fought along the road. Although Wadsworth and his brigadier Rice tried to restore order near the front, most of his troops fled to the Lacy House and were done fighting for the remainder of the battle.

At 10:00am, Lee's chief engineer, Major General

Starting from near Poague's guns, Longstreet counterattacked with the divisions of Major General Charles W. Field on the left and Brigadier General Joseph B. Kershaw on the right. A series of attacks by both sides caused the front line to move back and forth between the Widow Tapp farm and Brock Road. The Texans leading the charge north of the road fought gallantly at a heavy price—only 250 of the 800 men emerged unscathed. Field's Division drove back Wadsworth's force on the north side of the Widow Tapp Farm, while Kershaw's Division fought along the road. Although Wadsworth and his brigadier Rice tried to restore order near the front, most of his troops fled to the Lacy House and were done fighting for the remainder of the battle.

At 10:00am, Lee's chief engineer, Major General

At the Orange Turnpike, inconclusive fighting proceeded for most of the day. During the morning, Gordon scouted the Union line and recommended to his division commander, Jubal Early, that he conduct a flanking attack in Sedgwick's right. Early initially dismissed the venture as too risky, and Ewell did not have enough men to attack until 1:00pm when the brigade of Brigadier General

At the Orange Turnpike, inconclusive fighting proceeded for most of the day. During the morning, Gordon scouted the Union line and recommended to his division commander, Jubal Early, that he conduct a flanking attack in Sedgwick's right. Early initially dismissed the venture as too risky, and Ewell did not have enough men to attack until 1:00pm when the brigade of Brigadier General

Custer's First Brigade reached Brock Road about daylight on May 6. Custer extended his right toward Hancock and his left toward Gregg's 2nd Division at Todd's Tavern. Torbert's Second Brigade, commanded by Colonel Thomas Devin, began the trip from Chancellorsville to join Custer's right, bringing a battery. Hancock's infantry was hard pressed by two divisions from Longstreet's corps, but he worried about the location of Longstreet's other two divisions. Although Hancock wanted Custer to move down Brock Road to look for Longstreet's other divisions, Custer was attacked after 8:00am by Rosser's Brigade. The arrival of Devin with his six-gun battery plus two more guns from Gregg turned the fight into Custer's favor, and Rosser backed off.

Hancock still did not know what was behind the Confederate cavalry, and he kept a substantial portion of his corps outside of the fighting with Longstreet in order to protect his left. While Custer was fighting, Gregg was fighting Wickham's Brigade on the Brock Road near Todd's Tavern. This effectively blocked the Union Army from Spotsylvania Court House. Concern after Hancock's left had been turned by Longstreet's surprise attack from the unfinished railroad caused the Union leadership to order the cavalry to withdraw. At 2:30pm Gregg was ordered to withdraw to Piney Branch Church, and Custer and Devin were sent further east back to Catharine Furnace.

Custer's First Brigade reached Brock Road about daylight on May 6. Custer extended his right toward Hancock and his left toward Gregg's 2nd Division at Todd's Tavern. Torbert's Second Brigade, commanded by Colonel Thomas Devin, began the trip from Chancellorsville to join Custer's right, bringing a battery. Hancock's infantry was hard pressed by two divisions from Longstreet's corps, but he worried about the location of Longstreet's other two divisions. Although Hancock wanted Custer to move down Brock Road to look for Longstreet's other divisions, Custer was attacked after 8:00am by Rosser's Brigade. The arrival of Devin with his six-gun battery plus two more guns from Gregg turned the fight into Custer's favor, and Rosser backed off.

Hancock still did not know what was behind the Confederate cavalry, and he kept a substantial portion of his corps outside of the fighting with Longstreet in order to protect his left. While Custer was fighting, Gregg was fighting Wickham's Brigade on the Brock Road near Todd's Tavern. This effectively blocked the Union Army from Spotsylvania Court House. Concern after Hancock's left had been turned by Longstreet's surprise attack from the unfinished railroad caused the Union leadership to order the cavalry to withdraw. At 2:30pm Gregg was ordered to withdraw to Piney Branch Church, and Custer and Devin were sent further east back to Catharine Furnace.

Portions of the Wilderness battlefield are preserved as part of

Portions of the Wilderness battlefield are preserved as part of

Overview of Overland Campaign

- American Battlefield Trust video

Battle of the Wilderness

- American Battlefield Trust

Series of Battle Maps for Wilderness

- Library of Congress

Various Battle of the Wilderness maps

- Library of Congress

Wilderness Map

- Library of Congress

- National Park Service {{DEFAULTSORT:Wilderness Overland Campaign Battles of the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War Inconclusive battles of the American Civil War 1864 in Virginia Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park Battles of the American Civil War in Virginia May 1864 events Battles commanded by Ulysses S. Grant

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

. It was the first battle of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant's 1864 Virginia Overland Campaign against General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nort ...

and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most o ...

. The fighting occurred in a wooded area near Locust Grove, Virginia

Locust Grove is an unincorporated community in eastern Orange County, Virginia, United States. Its ZIP code is 22508, the population of the ZIP Code Tabulation Area was 7,605 at the time of the 2000 census and increased by 60% to 12,696 ...

, about west of Fredericksburg. Both armies suffered heavy casualties, nearly 29,000 in total, a harbinger of a war of attrition by Grant against Lee's army and, eventually, the Confederate capital, Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

. The battle was tactically inconclusive, as Grant disengaged and continued his offensive.

Grant attempted to move quickly through the dense underbrush of the Wilderness of Spotsylvania, but Lee launched two of his corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was first named as such in 1805. The size of a corps varies great ...

on parallel roads to intercept him. On the morning of May 5, the Union V Corps under Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Gouverneur K. Warren attacked the Confederate Second Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell, on the Orange Turnpike. That afternoon the Third Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General A. P. Hill

Ambrose Powell Hill Jr. (November 9, 1825April 2, 1865) was a Confederate general who was killed in the American Civil War. He is usually referred to as A. P. Hill to differentiate him from another, unrelated Confederate general, Daniel Harvey Hi ...

, encountered Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed t ...

George W. Getty's division ( VI Corps) and Major General Winfield S. Hancock's II Corps 2nd Corps, Second Corps, or II Corps may refer to:

France

* 2nd Army Corps (France)

* II Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* II Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French ...

on the Orange Plank Road. Fighting, which ended for the evening because of darkness, was fierce but inconclusive as both sides attempted to maneuver in the dense woods.

At dawn on May 6, Hancock attacked along the Plank Road, driving Hill's Corps back in confusion, but the First Corps of Lieutenant General James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Horse". He served under Lee as a corps ...

arrived in time to prevent the collapse of the Confederate right flank. Longstreet followed up with a surprise flanking attack from an unfinished railroad bed that drove Hancock's men back, but the momentum was lost when Longstreet was wounded by his own men. An evening attack by Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed t ...

John B. Gordon

John Brown Gordon () was an attorney, a slaveholding plantation owner, general in the Confederate States Army, and politician in the postwar years. By the end of the Civil War, he had become "one of Robert E. Lee's most trusted generals."

Af ...

against the Union right flank caused consternation at the Union headquarters, but the lines stabilized and fighting ceased. On May 7, Grant disengaged and moved to the southeast, intending to leave the Wilderness to interpose his army between Lee and Richmond, leading to the Battle of Todd's Tavern and Battle of Spotsylvania Court House.

Background

In the three years since fighting in the American Civil War began in 1861, theUnited States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

(a.k.a. the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

) made little progress against the Confederate Army in the Eastern Theater. The Union Army's most impressive successes came in the Western Theater, especially at the Battle of Vicksburg where nearly 30,000 Confederates surrendered. President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

wanted a military leader who would fight. In March 1864, Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Ulysses S. Grant was summoned from the Western Theater, promoted to lieutenant general, and given command of all the Union armies. Grant was the Union commander at Vicksburg, and also had major victories at Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, Shiloh, and Chattanooga. He chose to make his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

, although Major General George Meade retained formal command of that army. Major General William Tecumseh Sherman succeeded Grant in command of most of the western armies.

Grant believed that the eastern and western Union armies were too uncoordinated in their actions, and that the previous practice of conquering and guarding new territories required too many resources. Grant's new strategy was to attack with all forces at the same time, making it difficult for the Confederates to transfer forces from one battlefront to another. His objective was to destroy the Confederate armies rather than conquering territory. The two largest Confederate armies became the two major targets, and they were

Grant believed that the eastern and western Union armies were too uncoordinated in their actions, and that the previous practice of conquering and guarding new territories required too many resources. Grant's new strategy was to attack with all forces at the same time, making it difficult for the Confederates to transfer forces from one battlefront to another. His objective was to destroy the Confederate armies rather than conquering territory. The two largest Confederate armies became the two major targets, and they were General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nort ...

's Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most o ...

and General Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee. This new strategy pleased President Lincoln.

Grant considered Lee's army "the strongest, best appointed and most confident Army in the South." Lee was a professional soldier who fought in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Second Federal Republic of Mexico, Mexico f ...

. At the beginning of the American Civil War, he rejected an offer to be commander of the United States Army. He was considered a master tactician in individual battles, and had the advantage of fighting mostly on familiar (Virginia) territory. Although the Confederate Army had less resources and men than the Union Army, Lee made good use of railroads to move his forces from one front to another. By the time Grant appeared in the Eastern Theater, the Confederate soldiers knew that his six predecessors all failed against Lee, and believed that Grant's successes in the Western Theater were against inferior opponents.

Grant's plan

Grant's plan for Meade's Army of the Potomac was to move south to confront Lee's army between the Union and Confederate capital cities, Washington and Richmond. At the same time, General Benjamin Butler's Army of the James would approach Richmond,Petersburg

Petersburg, or Petersburgh, may refer to:

Places Australia

*Petersburg, former name of Peterborough, South Australia

Canada

* Petersburg, Ontario

Russia

*Saint Petersburg, sometimes referred to as Petersburg

United States

*Peterborg, U.S. Virg ...

, and Lee from the southeast near the James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Chesapea ...

. Major General Franz Sigel's Army of the Shenandoah would move through the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge- ...

and destroy the rail line, agricultural infrastructure, and granaries used to feed the Confederate armies. Brigadier Generals George Crook and William W. Averell

William Woods Averell (November 5, 1832 – February 3, 1900) was a career United States Army officer and a cavalry general in the American Civil War. He was the only Union general to achieve a major victory against the Confederates in the V ...

would attack the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, and salt and lead mines, in western Virginia before moving east to join Sigel. Sherman would attack Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to t ...

with the similar goal of destroying rail line, resources, and infrastructure used to equip and feed the Confederate armies.

Grant's campaign objective of the destruction of Lee's army coincided with the preferences of both Lincoln and his military chief of staff, Henry Halleck. Grant instructed Meade, "Lee's army will be your objective point. Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also." Although he hoped for a quick, decisive battle, Grant was prepared to fight a war of attrition. Both the Union and Confederate casualties could be high, but the Union had greater resources to replace lost soldiers and equipment. By May 2, Grant had four corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was first named as such in 1805. The size of a corps varies great ...

positioned to begin Meade's portion of Grant's plan against Lee's army. Three of the corps, plus cavalry, comprised Meade's Army of the Potomac. A fourth corps, reporting directly to Grant, added additional firepower. The Rapidan River divided the two foes. A few days later, Grant and Meade would cross the river and begin what became known as the Overland Campaign, and the Battle of the Wilderness was its first battle.

Opposing forces

Union

The Union force in the Battle of the Wilderness was the Army of the Potomac and a separate IX Corps. The Army of the Potomac was commanded by Major General George G. Meade, and Major General Ambrose E. Burnside was commander of the IX Corps. Both Meade and Burnside reported to Grant, who rode with Meade and his army. The II Corps was the largest of the corps, with 28,333 officers and enlisted men present for duty and equipped as of April 30, 1864. At the beginning of the campaign in May, Grant's Union forces totaled 118,700 men and 316 artillery pieces (a.k.a. guns) including Meade's Army of the Potomac and Burnside's IX Corps. *II Corps 2nd Corps, Second Corps, or II Corps may refer to:

France

* 2nd Army Corps (France)

* II Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* II Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French ...

, commanded by Major General Winfield S. Hancock, consisted of four divisions of infantry. This was Meade's premier fighting unit.

* V Corps, commanded by Major General Gouverneur K. Warren, had four divisions of infantry.

* VI Corps had three divisions and was commanded by Major General John Sedgwick.

* Cavalry Corps, newly commanded by Major General Philip Sheridan, had three divisions. The 3rd Division's 5th New York Cavalry Regiment

The 5th New York Cavalry Regiment, also known as the 5th Regiment New York Volunteer Cavalry and nicknamed the "1st Ira Harris Guards", was a cavalry regiment of the Union Army during the American Civil War. The regiment had a good fighting rep ...

was armed with seven-shot Spencer carbines, as was the First Brigade of the 1st Division, known as the Michigan Brigade.

* Additional men in Meade's army that were not part of the four corps were from the provost guard, a small group of guards and orderlies, and portions of the artillery not assigned to a corps.

* IX Corps, commanded by Burnside, consisted of four divisions of infantry, each with its own artillery. Burnside also had reserve artillery and two regiments of cavalry. Only about 6,000 men in the IX Corps were seasoned veterans.

Confederate

The Confederate force in the Battle of the Wilderness was the Army of Northern Virginia, commanded by General Robert E. Lee. Listed below are Lee's three infantry corps and one cavalry corps, which totaled to 66,140 men including staff and men in the artillery. Each corps had three divisions plus artillery except the First Corps, which had only two divisions. The Third Corps was the largest, with 22,675 men plus another 1,910 for artillery. * First Corps was commanded byLieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Horse". He served under Lee as a corps ...

. This was Lee's elite fighting unit.

* Second Corps was commanded by Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell.

* Third Corps was commanded by Lieutenant General Ambrose Powell "A.P." Hill.

* Cavalry Corps was commanded by Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart.

Disposition of forces and movement to battle

Wilderness

The Wilderness is located south of the Rapidan River in Virginia's Spotsylvania County and Orange County. Its southern border is Spotsylvania Court House, and western border is usually considered the Rapidan River tributary Mine Run. Its eastern border is less definite, causing estimates of the size of the Wilderness to vary. While the maximum area for the Wilderness is to , historians discussing the battles fought there typically use . At the time of the battle, the region was a "patchwork of open areas and vegetation of varying density." Much of the vegetation was a dense second-growth forest consisting of small trees, bushes, shrubs, and

The Wilderness is located south of the Rapidan River in Virginia's Spotsylvania County and Orange County. Its southern border is Spotsylvania Court House, and western border is usually considered the Rapidan River tributary Mine Run. Its eastern border is less definite, causing estimates of the size of the Wilderness to vary. While the maximum area for the Wilderness is to , historians discussing the battles fought there typically use . At the time of the battle, the region was a "patchwork of open areas and vegetation of varying density." Much of the vegetation was a dense second-growth forest consisting of small trees, bushes, shrubs, and pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family (biology), family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanic ...

s.

Since clearings were scarce, and the region had only a few narrow winding roads, mounted cavalry fighting was nearly impossible. The dense woods, often filled with smoke, made it difficult to see enemy soldiers. This put attackers at a disadvantage, as soldiers often fired at sounds instead of visual cues. Infantry units had difficulty keeping alignment, and often became lost or were involved in friendly-fire incidents. The Confederates had a better knowledge of the terrain, and it diminished the Union advantage of more manpower. The terrain also diminished the effectiveness of artillery. Grant was aware of how the Wilderness made his advantages in size and artillery less effective, and preferred to move his army further south to fight Lee in open ground.

Lee prepares

On May 2, Lee met with his generals on Clark Mountain, obtaining a panoramic view of the Union camps. He realized that Grant was getting ready to attack, but did not know the precise route of advance. He predicted (correctly) that Grant would cross to the east of the Confederate fortifications on the Rapidan, using the Germanna and Ely Fords, but he could not be certain.

To retain flexibility of response, Lee had dispersed his Army over a wide area. Longstreet's First Corps was around Gordonsville, from where they had the flexibility to respond by railroad to potential threats to the Shenandoah Valley or to Richmond. Hill's Third Corps was outside Orange Court House. Ewell's Second Corps was near Morton's Ford and Mine Run, northeast of Hill. Stuart's cavalry was scattered further south from Gordonsville to Fredericksburg.

On May 2, Lee met with his generals on Clark Mountain, obtaining a panoramic view of the Union camps. He realized that Grant was getting ready to attack, but did not know the precise route of advance. He predicted (correctly) that Grant would cross to the east of the Confederate fortifications on the Rapidan, using the Germanna and Ely Fords, but he could not be certain.

To retain flexibility of response, Lee had dispersed his Army over a wide area. Longstreet's First Corps was around Gordonsville, from where they had the flexibility to respond by railroad to potential threats to the Shenandoah Valley or to Richmond. Hill's Third Corps was outside Orange Court House. Ewell's Second Corps was near Morton's Ford and Mine Run, northeast of Hill. Stuart's cavalry was scattered further south from Gordonsville to Fredericksburg.

Grant crosses the river

On May 4, 1864, the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River at three places and converged on the Wilderness of Spotsylvania in east central Virginia.

On May 4, 1864, the Army of the Potomac crossed the Rapidan River at three places and converged on the Wilderness of Spotsylvania in east central Virginia. Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed t ...

James H. Wilson led his 3rd Cavalry Division across the river at Germanna Ford between 4:00am and 6:00am, and drove off a small group of Confederate cavalry pickets. After engineers placed pontoon bridge

A pontoon bridge (or ponton bridge), also known as a floating bridge, uses floats or shallow- draft boats to support a continuous deck for pedestrian and vehicle travel. The buoyancy of the supports limits the maximum load that they can carry. ...

s, the V Corps (Warren) and later the VI Corps (Sedgwick) crossed safely. Wilson continued south on the Germanna Plank Road toward Wilderness Tavern and the Orange Turnpike. He halted at Wilderness Tavern at noon to wait for the V Corps, and sent scouts to the south and west.

A few miles east, Brigadier General David M. Gregg

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

led his 2nd Cavalry Division across the river at Ely's Ford. They tried to capture the nearby Confederate outpost, but the southerners fled into the darkness. By 9:00am a pontoon bridge was placed across the water, and the II Corps (Hancock) began crossing. Gregg's cavalry moved south to Chancellorsville, where Hancock's men planned to camp. Once Hancock's men began arriving, Gregg moved further south to Alrich near the intersection of the Orange Plank Road and Catharpin Road, where they would protect Hancock and the army's wagons.

The IX Corps (Burnside) remained north of the river near Germanna Ford, with orders to protect the supply train. Although Grant insisted that the army travel light with minimal artillery and supplies, its supply train was 60 to 70 miles (97 to 110 km) long. Meade had an estimated 4,300 wagons, 835 ambulances, and a herd of cattle. The supply train crossed the Rapidan at Ely's and Culpeper Mine Fords. At Culpeper Mine Ford, it was guarded by Brigadier General Alfred T. A. Torbert's 1st Cavalry Division. Grant and Meade gambled that they could move the army quickly enough to avoid being ensnared in the Wilderness, but Meade halted the II and V Corps to allow the wagon train to catch up.

Lee responds

At the Wilderness a year earlier, Lee defeated the Army of the Potomac in the Battle of Chancellorsville despite having an army less than half the size of the Union army. Much of the fighting at that time occurred slightly east of the Union army's current route. Having already secured a victory one year ago in similar circumstances, Lee hoped to fight Grant in the Wilderness. However, Lee needed Longstreet's First Corps to be in position to fight before the battle started. As Grant's plan became clearer to Lee on May 4, Lee arranged his forces to use the advantages of the Wilderness. He needed his Second and Third Corps to delay Grant's army until Longstreet's First Corps could get in place. Ewell's Second Corps was sent east on the Orange Turnpike, reaching Robertson's Tavern at Locust Grove. His lead column camped about from the unsuspecting Union soldiers. Hill was sent east on the Orange Plank Road and stopped at the hamlet of New Verdiersville. Hill had two of his three divisions. The division commanded by Major General Richard H. Anderson was left at Orange Court House to guard the river. These two corps were to avoid battle, if possible, until Longstreet's First Corps arrived. That evening, Lee decided that Ewell and Hill should strike first, preserving the initiative. Longstreet would arrive a day later, or Ewell and Hill could retreat west to Mine Run if necessary. Orders were sent around 8:00pm to move early in the morning.Union cavalry

At Wilderness Tavern, Wilson sent a small force west on the Orange Turnpike. After the head of the V Corps reached Wilderness Tavern around 11:00am, Wilson continued south. He arrived at Parker's Store near the Orange Plank Road at 2:00pm. Scouts were sent south to Catharpin Road and west to Mine Run where they found only small enemy squads. During that time, his squad on the Orange Turnpike skirmished with Confederate soldiers near Robertson's Tavern (Locust Grove). Assuming they were fighting with a small group of Confederate pickets, they withdrew and by evening rejoined the division at Parker's Store. Meade's original plan was to have Torbert's 1st Cavalry Division join Wilson, but he received an erroneous report that the Confederate cavalry was operating in his Army's rear, in the direction of Fredericksburg. He ordered his 1st and 2nd cavalry divisions to move east to deal with that perceived threat, leaving only Wilson's Division to screen for three corps. Wilson had little experience with cavalry, and the 3rd Division was the smallest of the three cavalry divisions. Meade believed that Lee would fight from behind (west of) Mine Run, and aligned his army north to south from Germanna Ford to Shady Grove Church while it spent the night in the Wilderness. This change of plans by the Union leadership did not serve the army well. Not only were the Union forces spending the night in the Wilderness, "lax cavalry patrols" were causing leadership to be unaware of the proximity of Lee's Second Corps (Ewell).Battle May 5

The Battle of the Wilderness had two distinct fronts, the Orange Turnpike and the Orange Plank Road, where most of the fighting was conducted by infantry. Any efforts to bridge the gap between those two fronts did not last long. Most of the cavalry fighting occurred south of the infantry, especially along Catharpin Road and Brock Road.Hammond's cavalry

At 5:00 am on May 5, Wilson's Division proceeded southward from Parker's Store. The 5th New York Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John Hammond, was detached and instructed to patrol west of the Parker's Store area until relieved by Warren's V Corps. A probe west on the Orange Plank Road discovered Confederate soldiers. Despite being reinforced, the Union probe was driven back toward Parker's Store. It was soon discovered that they were fighting infantry from most of Hill's Third Corps.

Hammond's total force consisted of only about 500 men. Hammond understood that the dense woods and the large infantry force made fighting on horseback inadvisable. The command fought dismounted and spread out as a skirmish line while utilizing their Spencer repeating rifles. The regiment slowly retreated east, moving toward and beyond Parker's Store on the Orange Plank Road. Once the Confederates advanced east of Parker's Store, the remainder of Wilson's cavalry division was cut off from Meade and Warren's VICorps.

At 5:00 am on May 5, Wilson's Division proceeded southward from Parker's Store. The 5th New York Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel John Hammond, was detached and instructed to patrol west of the Parker's Store area until relieved by Warren's V Corps. A probe west on the Orange Plank Road discovered Confederate soldiers. Despite being reinforced, the Union probe was driven back toward Parker's Store. It was soon discovered that they were fighting infantry from most of Hill's Third Corps.

Hammond's total force consisted of only about 500 men. Hammond understood that the dense woods and the large infantry force made fighting on horseback inadvisable. The command fought dismounted and spread out as a skirmish line while utilizing their Spencer repeating rifles. The regiment slowly retreated east, moving toward and beyond Parker's Store on the Orange Plank Road. Once the Confederates advanced east of Parker's Store, the remainder of Wilson's cavalry division was cut off from Meade and Warren's VICorps.

Orange Turnpike

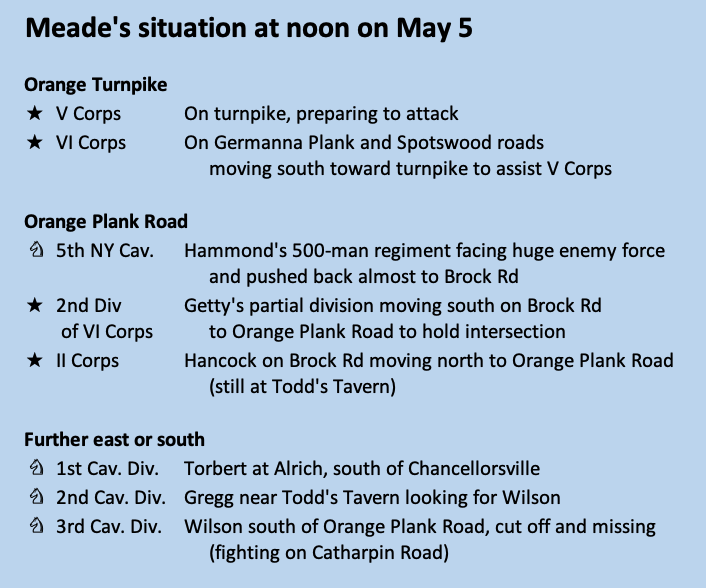

At 6:00am on May 5, Warren's V Corps began moving south over farm lanes toward the Parker's Store. The Confederate infantry was observed in the west near the Orange Turnpike, and Meade was notified. Grant instructed "If any opportunity presents itself of pitching into a part of Lee's army, do so without giving time for disposition." Meade halted his army and directed Warren to attack, assuming that the Confederates were a division and not an entire infantry corps. Hancock was held at Todd's tavern. Although Meade told Grant that the threat was probably a delaying tactic without the intent to give battle, he stopped his entire army—the exact thing Lee wanted him to do. The Confederate force was Ewell's Second Corps, and his men erected earthworks on the western end of the clearing known as Saunders Field. Ewell's instructions from Lee were to not advance too fast, since his corps was out of the reach of Hill's Third Corps—and Longstreet's First Corps was not yet at the battlefield.

At 6:00am on May 5, Warren's V Corps began moving south over farm lanes toward the Parker's Store. The Confederate infantry was observed in the west near the Orange Turnpike, and Meade was notified. Grant instructed "If any opportunity presents itself of pitching into a part of Lee's army, do so without giving time for disposition." Meade halted his army and directed Warren to attack, assuming that the Confederates were a division and not an entire infantry corps. Hancock was held at Todd's tavern. Although Meade told Grant that the threat was probably a delaying tactic without the intent to give battle, he stopped his entire army—the exact thing Lee wanted him to do. The Confederate force was Ewell's Second Corps, and his men erected earthworks on the western end of the clearing known as Saunders Field. Ewell's instructions from Lee were to not advance too fast, since his corps was out of the reach of Hill's Third Corps—and Longstreet's First Corps was not yet at the battlefield.

Warren approached the eastern end of Saunders Field with the division of Brigadier General Charles Griffin along the road on the right and the division of Brigadier General James S. Wadsworth on the left. Brigadier General Samuel W. Crawford's division was too far away on the left near Chewning Farm, and the division of Brigadier General John C. Robinson was in reserve closer to Wilderness Tavern. It took time to align Warren's divisions, and there was some concern about Griffin's northern (right) flank. A major problem was that "once a division left the roads or fields it disappeared utterly, and its commander could not tell whether it was in line with the others...." Brigadier General Horatio Wright's 1st Division from Sedgwick's VI Corps began to move south on the Germanna Plank Road to Spotswood Road to protect Warren's right. Warren requested a delay from attacking to wait for Wright. By 12:00pm, Meade was frustrated by the delay and ordered Warren to attack before Sedgwick's VI Corps could arrive. Warren's troops arrived at Saunders Field around 1:00pm. The Confederate division of Major General Edward Johnson was positioned on the Orange Turnpike west of Sanders Field, and it also guarded the Spotswood Road route of Sedgwick. Behind Johnson and further south was the division of Major General Robert E. Rodes, while the division of Major General Jubal Early waited further west in reserve.

Warren approached the eastern end of Saunders Field with the division of Brigadier General Charles Griffin along the road on the right and the division of Brigadier General James S. Wadsworth on the left. Brigadier General Samuel W. Crawford's division was too far away on the left near Chewning Farm, and the division of Brigadier General John C. Robinson was in reserve closer to Wilderness Tavern. It took time to align Warren's divisions, and there was some concern about Griffin's northern (right) flank. A major problem was that "once a division left the roads or fields it disappeared utterly, and its commander could not tell whether it was in line with the others...." Brigadier General Horatio Wright's 1st Division from Sedgwick's VI Corps began to move south on the Germanna Plank Road to Spotswood Road to protect Warren's right. Warren requested a delay from attacking to wait for Wright. By 12:00pm, Meade was frustrated by the delay and ordered Warren to attack before Sedgwick's VI Corps could arrive. Warren's troops arrived at Saunders Field around 1:00pm. The Confederate division of Major General Edward Johnson was positioned on the Orange Turnpike west of Sanders Field, and it also guarded the Spotswood Road route of Sedgwick. Behind Johnson and further south was the division of Major General Robert E. Rodes, while the division of Major General Jubal Early waited further west in reserve.

Fight at Saunders Field

By the time the Union line arrived near the enemy, it had numerous gaps and some regiments faced north instead of west. The concerns about Warren's right flank were justified. As Griffin's division advanced, Ayres's brigade held the right but had difficulty maintaining its lines in a "blizzard of lead". They received enfilading fire on their right from the brigade of Confederate

By the time the Union line arrived near the enemy, it had numerous gaps and some regiments faced north instead of west. The concerns about Warren's right flank were justified. As Griffin's division advanced, Ayres's brigade held the right but had difficulty maintaining its lines in a "blizzard of lead". They received enfilading fire on their right from the brigade of Confederate Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed t ...

Leroy A. Stafford

Leroy Augustus Stafford Sr. (April 13, 1822 – May 8, 1864), was a brigadier general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War.

Early life

Leroy A. Stafford was born on Greenwood Plantation near Cheneyville, south of Alexandria ...

, causing all but two regiments ( 140th and 146th New York) to retreat east across Saunders Field. On the left of Ayres, the brigade of Brigadier General Joseph J. Bartlett made better progress and overran the position of Confederate Brigadier General John M. Jones, who was killed. However, since Ayres's men were unable to advance, Bartlett's right flank was now exposed to attack and his brigade was forced to flee back across the clearing. Bartlett's horse was shot out from under him and he barely escaped capture.

To the left of Bartlett was Wadsworth's Iron Brigade

The Iron Brigade, also known as The Black Hats, Black Hat Brigade, Iron Brigade of the West, and originally King's Wisconsin Brigade was an infantry brigade in the Union Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War. Although it fought ent ...

, which was composed of regiments from the Midwest and commanded by Brigadier General Lysander Cutler. The Iron Brigade advanced through woods south of Saunders Field and contributed to the collapse of Jones' Brigade while capturing battle flags and taking prisoners. However, the Iron Brigade outdistanced Bartlett's men—exposing the Midwesterner's right flank. The Confederate brigade of Brigadier General George P. Doles attacked the exposed flank, and the Iron Brigade's 6th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment

The 6th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War. It spent most of the war as a part of the famous Iron Brigade in the Army of the Potomac.

Service

The 6th Wisconsin was rai ...

suffered nearly 50 casualties in only a few minutes. Soon the Confederate brigade of Brigadier General John B. Gordon

John Brown Gordon () was an attorney, a slaveholding plantation owner, general in the Confederate States Army, and politician in the postwar years. By the end of the Civil War, he had become "one of Robert E. Lee's most trusted generals."

Af ...

joined in the attack, tearing through the Union line and forcing the Iron Brigade to break and retreat.

Further to the Union left, near the Higgerson farm, the Union brigade of Colonel Roy Stone was ambushed in waist-high swamp water, and the survivors fled northeast to the fields of the Lacy House (a.k.a. Ellwood Manor). One soldier blamed the fiasco on the gap between Stone's Brigade and the Iron Brigade. On Wadsworth's farthest left, the brigade of Brigadier General James C. Rice suffered severe losses when the North Carolina brigade commanded by Brigadier General Junius Daniel got around Rice's unprotected left. The problem was compounded when Stone's Brigade fell back from Rice's right. Rice's survivors were chased by Daniel's men almost back to the Lacy House, where the V Corps artillery was used to slow the pursuing Confederates. A quick fight over the guns resulted in casualties for both sides. Rice's losses were severe, including two of his five regimental commanders wounded.

Further south, Crawford's First Brigade, commanded by Colonel William McCandless, did not reach the fighting in time to help Wadsworth's left. The brigade became surrounded by Confederates and its 7th Pennsylvania Reserve Regiment was captured. Crawford was in danger of the having the remaining portion of his division cut off, so it withdrew toward the Lacy House while the Confederates occupied the Chewning farm. Back at Saunders Field, Warren had ordered an artillery section into Saunders Field to support his attack, but it was captured by Confederate soldiers, who were pinned down and prevented by rifle fire from moving the guns. In the midst of hand-to-hand combat at the guns, the field caught fire and men from both sides were shocked as their wounded comrades burned to death. The first phase of fighting on the Orange Turnpike was over by 2:30pm.

The lead elements of Sedgwick's VI Corps reached Saunders Field around 3:00pm. Wright commanded the renewal of fighting until Sedgwick arrived around 3:30pm. The fighting was now in the woods north of the Turnpike and both sides traded attacks and counterattacks. Ewell held his position for the remainder of the afternoon. During the fray, Confederate Brigadier General Leroy A. Stafford

Leroy Augustus Stafford Sr. (April 13, 1822 – May 8, 1864), was a brigadier general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War.

Early life

Leroy A. Stafford was born on Greenwood Plantation near Cheneyville, south of Alexandria ...

was shot through the shoulder blade, the bullet severing his spine. Despite being paralyzed from the waist down and in agonizing pain, he managed to still urge his troops forward. He died four days later.

Getty and Hancock at Orange Plank Road

Visibility was limited near Orange Plank Road, and officers had difficulty controlling men and maintaining formations. Attackers would move blindly and noisily forward, becoming targets for concealed defenders. Unable to duplicate the surprise that was achieved by Ewell on the Turnpike, A.P. Hill's approach was detected from the Chewning farm location of Crawford's 3rd Division of the V Corps. Crawford notified Meade, and his message arrived at Meade's headquarters around 10:15am.

Crawford sent the

Visibility was limited near Orange Plank Road, and officers had difficulty controlling men and maintaining formations. Attackers would move blindly and noisily forward, becoming targets for concealed defenders. Unable to duplicate the surprise that was achieved by Ewell on the Turnpike, A.P. Hill's approach was detected from the Chewning farm location of Crawford's 3rd Division of the V Corps. Crawford notified Meade, and his message arrived at Meade's headquarters around 10:15am.

Crawford sent the 13th Pennsylvania Reserve Regiment

The Thirteenth Pennsylvania Reserve Regiment, also known as the 42nd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, the 1st Pennsylvania Rifles, Kane's Rifles, or simply the "Bucktails," was a volunteer infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during th ...

(a.k.a. the Bucktails) as skirmishers toward Hill, but Hammond's line was falling apart before the Bucktails arrived near the Orange Plank Road. Crawford did not support his Pennsylvanians, and instead worked to solidify his position at the Chewning Farm and get ready to assist in the Orange Turnpike fighting. By the time this was accomplished, Hammond was beyond helping. Meade's army was in danger if Hill could push Hammond beyond Brock Road and take control of the intersection (Orange Plank and Brock roads). That would cause Warren's VCorps to have large enemy forces on two sides, and Hancock's IICorps could get isolated from the rest of Meade's army.

Although Hancock was not far from the intersection of Orange Plank Road and Brock Road, he would have to move on a twisting road that was a narrow wagon route. The VI Corps lead division of Brigadier General George W. Getty was waiting at Wilderness Tavern, so at 10:30am Meade sent it to defend the important intersection until Hancock could get there. Hammond's 500-man cavalry force, employing repeating carbines and fighting dismounted, succeeded in slowing Hill's approach. However, Hammond's small force was vastly outnumbered and continued to gradually retreat east.

By noon, Hill had the division of Major General Henry Heth past the Widow Tapp farm, and the division of Major General Cadmus M. Wilcox followed near Parker's Store. Hammond was nearly out of ammunition and was eventually pushed back to the vital intersection around noon, but was relieved by Getty's advance brigade just before Hill's forces arrived. Hammond's force moved further east behind Getty, and was done fighting. Because of Hammond's repeating rifles, the Confederate prisoners stated that they believed they had been fighting an entire brigade. Getty's men skirmished briefly with Heth's advance, and held the intersection.

Getty held the intersection for hours waiting for Hancock's II Corps to arrive. By 3:30pm, initial elements of Hancock's corps were arriving, and Meade ordered Getty to assault the Confederate line. Getty attacked at 4:15pm while elements of Hancock's II Corps began arriving shortly thereafter. Getty was reinforced by Hancock's men, while Confederate commander Heth was reinforced by Wilcox's Division. The fighting was fierce, with casualties for the brigade commanded by Brigadier General Alexander Hays particularly high—including Hays who was killed while addressing the 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment

The 63rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Service

The 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry was organized at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in August 1861 and mustered in ...

. Attacks and counterattacks continued into the night as casualties grew while neither side gained an advantage. Getty's Division was relieved by the II Corps after dark, and Getty's horse was killed in the day's fighting.

Wilson at Catharpin Road

Leaving Hammond's regiment at Parker's Store at 5:00am on May 5, Wilson moved his two brigades south. His Second Brigade led the way, and it was commanded by Colonel George H. Chapman. His First Brigade was commanded by Colonel Timothy M. Bryan. Chapman reached Catharpin Road and moved west beyond Craig's Meeting House, where he found 1,000 men from a Confederate cavalry brigade commanded by Brigadier General Thomas L. Rosser. After initially driving Rosser back, both of Wilson's brigades fled east after finding Hill's infantry on their north side and Rosser's cavalry on the Catharpin Road on their south side. The

Leaving Hammond's regiment at Parker's Store at 5:00am on May 5, Wilson moved his two brigades south. His Second Brigade led the way, and it was commanded by Colonel George H. Chapman. His First Brigade was commanded by Colonel Timothy M. Bryan. Chapman reached Catharpin Road and moved west beyond Craig's Meeting House, where he found 1,000 men from a Confederate cavalry brigade commanded by Brigadier General Thomas L. Rosser. After initially driving Rosser back, both of Wilson's brigades fled east after finding Hill's infantry on their north side and Rosser's cavalry on the Catharpin Road on their south side. The 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment

The 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment (also known as the 163rd Pennsylvania Volunteers) was a cavalry regiment of the Union Army during the American Civil War. The regiment was present for 50 battles, beginning with the Battle of Hanover in Pe ...

was the rear guard, and it became surrounded on three sides. The regiment left the road and blended into the woods and a swamp.

While Wilson battled Rosser, Sheridan's other two cavalry divisions were further east. Around noon, Meade notified Sheridan that Wilson had been cut off, and Gregg's 2nd Cavalry Division was sent to explore the Catharpin Road. Gregg found Wilson and confronted Rosser, who was driven back across the Po River bridge. In late afternoon, Gregg also fought Major General Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry division on the Brock Road near Alsop. At nightfall, Rosser sat on the high ground west of the Po River bridge, Lee's men camped near Alsop, and Wilson's exhausted division camped north and east of Todd's Tavern. Wilson was surprised that evening when the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry, thought to be captured, rejoined the division. During the night, Gregg remained at Todd's Tavern, Wilson put Chapman's Brigade on the Brock Road, and the brigade of George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his clas ...

from Torbert's Division began moving to relieve Wilson. While the remaining portion of Torbert's Division was south of Chancellorsville at Alrich, Torbert checked into a hospital and Brigadier General Wesley Merritt assumed command of the division.

Battle May 6

Grant's plan for May 6 was to resume the attacks at 5:00am. Sedgwick and Warren would renew their attack on Ewell at the Orange Turnpike, and Hancock and Getty would attack Hill again on the Orange Plank Road. At the same time, an additional force of men currently stationed around the Lacy House would move south and attack Hill's exposed northern flank. Wadsworth requested leadership of this force, and it consisted of his division plus a fresh brigade from Robinson's division commanded by Brigadier General Henry Baxter. Adding to Wadsworth, two divisions from Burnside's IX Corps were to move through the area between the Turnpike and the Plank Road and move south to flank Hill. Hill's weary men spent the evening of May 5 and the early morning hours of May 6 resting where they had fought—with little line integrity and some regiments separated from their brigades. The men from Heth's Division were generally on the north side of the Orange Plank Road, while the men from Wilcox's Division were mostly on the south side. Although he was aware that Hill's front line along the Orange Plank Road needed to be reformed, Lee chose to allow Hill's men to rest where they were—assuming that Longstreet's First Corps and Hill's remaining division, commanded by Major General Anderson, would arrive in time to relieve Heth and Wilcox. Longstreet's men had marched in 24 hours, but were still from the battlefield. Once Longstreet's men arrived, Lee planned to shift Hill to the left to cover some of the open ground between his divided forces. Longstreet calculated that he had sufficient time to allow his men, tired from marching all day, to rest and the First Corps did not resume marching until 1:00am. Moving cross-country in the dark, they made slow progress and lost their way at times, and by sunrise had not reached their designated position.Attacks begin

During the night, Ewell placed his artillery on his extreme left and on both sides of the Orange Turnpike. He also had an abatis in front of his trenchline. He attacked Sedgwick on the north side of the turnpike at 4:45am. His line moved forward and then back on multiple occasions, and some ground was fought over as much as five times.

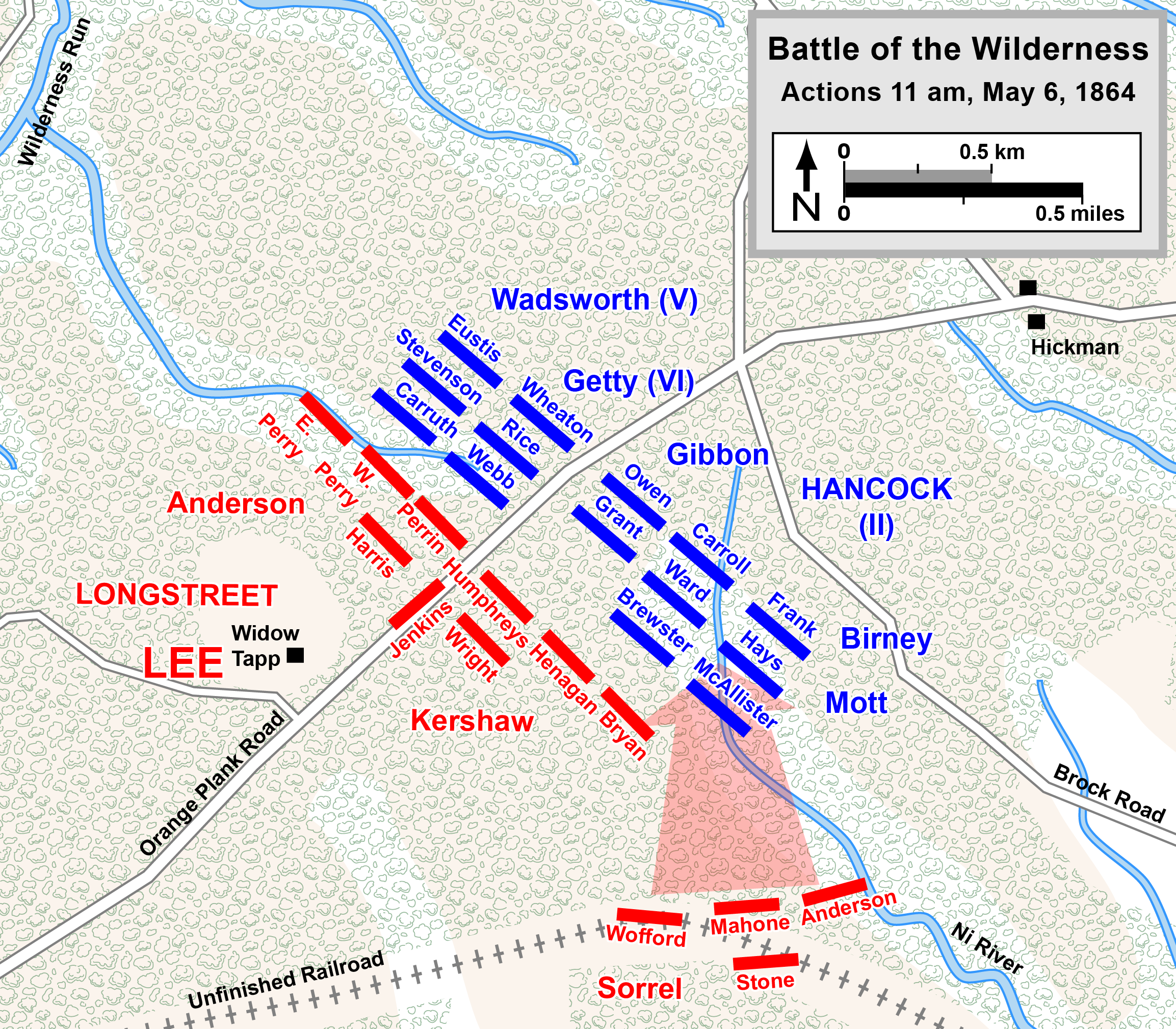

To the south on the Orange Plank Road, Hancock's II Corps with Getty's Division attacked Hill at 5:00am, overwhelming the ill-prepared Third Corps in concert with Wadsworth. Following Hill's orders, Lieutenant Colonel

During the night, Ewell placed his artillery on his extreme left and on both sides of the Orange Turnpike. He also had an abatis in front of his trenchline. He attacked Sedgwick on the north side of the turnpike at 4:45am. His line moved forward and then back on multiple occasions, and some ground was fought over as much as five times.

To the south on the Orange Plank Road, Hancock's II Corps with Getty's Division attacked Hill at 5:00am, overwhelming the ill-prepared Third Corps in concert with Wadsworth. Following Hill's orders, Lieutenant Colonel William T. Poague

William Thomas Poague (December 20, 1835 – September 8, 1914) was a Confederate States Army officer serving in the artillery during the American Civil War. He later served as Treasurer of the Virginia Military Institute.

Early life

Born in R ...

's 12 guns at the Widow Tapp farm fired tirelessly at the road—despite the Confederate soldiers retreating in front of the guns. This slowed the Union advance, but could not stop it.

While Hill's Corps retreated, reinforcements arrived. Longstreet rode ahead of his men and arrived at the battlefield around 6:00am. His men marched east and then turned north, arriving on the Orange Plank Road near Parker's Store where they found men from Hill's Corps retreating. Brigadier General John Gregg's Texas Brigade was the vanguard of Longstreet's column. General Lee, relieved and excited, waved his hat over his head and shouted, "Texans always move them!" Caught up in the excitement, Lee began to move forward behind the advancing brigade. As the Texans realized this, they halted and grabbed the reins of Lee's horse, Traveller

Traveler(s), traveller(s), The Traveler(s), or The Traveller(s) may refer to:

People Generic terms

*One engaged in travel

*Explorer, one who searches for the purpose of discovery of information or resources

*Nomad, a member of a community withou ...

, telling the general that they were concerned for his safety and would only go forward if he moved to a less exposed location. Longstreet was able to convince Lee that he had matters well in hand and the commanding general relented.

Longstreet counterattacks

Starting from near Poague's guns, Longstreet counterattacked with the divisions of Major General Charles W. Field on the left and Brigadier General Joseph B. Kershaw on the right. A series of attacks by both sides caused the front line to move back and forth between the Widow Tapp farm and Brock Road. The Texans leading the charge north of the road fought gallantly at a heavy price—only 250 of the 800 men emerged unscathed. Field's Division drove back Wadsworth's force on the north side of the Widow Tapp Farm, while Kershaw's Division fought along the road. Although Wadsworth and his brigadier Rice tried to restore order near the front, most of his troops fled to the Lacy House and were done fighting for the remainder of the battle.

At 10:00am, Lee's chief engineer, Major General

Starting from near Poague's guns, Longstreet counterattacked with the divisions of Major General Charles W. Field on the left and Brigadier General Joseph B. Kershaw on the right. A series of attacks by both sides caused the front line to move back and forth between the Widow Tapp farm and Brock Road. The Texans leading the charge north of the road fought gallantly at a heavy price—only 250 of the 800 men emerged unscathed. Field's Division drove back Wadsworth's force on the north side of the Widow Tapp Farm, while Kershaw's Division fought along the road. Although Wadsworth and his brigadier Rice tried to restore order near the front, most of his troops fled to the Lacy House and were done fighting for the remainder of the battle.

At 10:00am, Lee's chief engineer, Major General Martin L. Smith

Martin Luther Smith (September 9, 1819 – July 29, 1866) was an American soldier and civil engineer, serving as a major general in the Confederate States Army. Smith was one of the few Northern-born generals to fight for the Confederacy, as he ...

, reported to Longstreet that he had explored an unfinished railroad bed south of the Plank Road and that it offered easy access to the Union left flank. Longstreet assigned his aide, Lieutenant Colonel Moxley Sorrel, to the task of leading three fresh brigades for a surprise attack. An additional brigade, which was reduced in strength from the morning's fighting, volunteered to join them. Sorrel and the senior brigade commander, Brigadier General William Mahone, struck at 11:00am while Longstreet resumed his main attack. The Union line was broken and driven back, Wadsworth was mortally wounded, and Hancock reorganized his line in trenches near the Brock Road. Hancock wrote later that the flanking attack rolled up his line "like a wet blanket."

By noon, a Confederate victory seemed likely. Longstreet rode forward on the Orange Plank Road with several of his officers while another fire caused Mahone's 12th Virginia Infantry Regiment

The 12th Virginia Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment mostly raised in Petersburg, Virginia, for service in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War, but with units from the cities of Norfolk and Richmond, and Greens ...

to become separated from its brigade. An aide suggested that Longstreet was too close to the front, but his advice was disregarded. As the Virginians moved through the woods back to the road, their brigade mistook them for Union soldiers, and the two Confederate forces began shooting at each other. Longstreet's mounted party was caught in the crossfire, and Longstreet was severely wounded in his neck. Brigadier General Micah Jenkins, aide-de-camp Captain Alfred E. Doby and orderly Marcus Baum were killed. Longstreet was able to turn over his command directly to division commander Field and told him to "Press the enemy." Burnside finally arrived on the Confederate northern flank with three brigades, and attacked around 2:00pm. His fighting for the day, beginning against Colonel William F. Perry

William Flank Perry (March 12, 1823 – December 18, 1901) was a Confederate States Army brigadier general during the American Civil War. Before the war, he was a self-taught teacher and lawyer, but never practiced law. Perry was elected Al ...