Battle of Little Blue River on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Little Blue River was fought on October 21, 1864, as part of

At the start of the

At the start of the

After the battle at Lexington, Blunt's forces fell back to the west, Moonlight's brigade serving as the

After the battle at Lexington, Blunt's forces fell back to the west, Moonlight's brigade serving as the

Official casualty numbers are only known for a few units on each side. The 11th and 15th Kansas Cavalries and the 2nd Colorado Cavalry combined had 20 men killed. On the Confederate side, the 3rd Missouri Cavalry Regiment suffered 31 killed and wounded, while a total of three men were killed between Davies's battalion and the 10th Missouri Cavalry Regiment. Among the Union dead was Major Nelson Smith of the 2nd Colorado Cavalry, while Confederate guerrilla leader George Todd was also killed. Todd had led a group of guerrillas during the battle; he was shot in the throat during the final stages of the action. Confederate surgeon William McPheeters reported that 10 wounded Union soldiers were left in Independence, and that civilians reported about 100 more had been taken with the Union troops during the retreat. McPheeters also noted seeing the bodies of dead Union soldiers strewn along the road from the river to Independence. Historian Mark Lause estimates that the Union may have lost up to about 300 men, and the Confederates more. Shelby later described the fight as the beginning of significant difficulties for his division during the campaign.

The day after the battle, Price sent Shelby south of Curtis's main line along the Big Blue River. In the initial stages of the Battle of Byram's Ford, Shelby's men forced their way across the Big Blue River, causing Curtis to order a withdrawal to

Official casualty numbers are only known for a few units on each side. The 11th and 15th Kansas Cavalries and the 2nd Colorado Cavalry combined had 20 men killed. On the Confederate side, the 3rd Missouri Cavalry Regiment suffered 31 killed and wounded, while a total of three men were killed between Davies's battalion and the 10th Missouri Cavalry Regiment. Among the Union dead was Major Nelson Smith of the 2nd Colorado Cavalry, while Confederate guerrilla leader George Todd was also killed. Todd had led a group of guerrillas during the battle; he was shot in the throat during the final stages of the action. Confederate surgeon William McPheeters reported that 10 wounded Union soldiers were left in Independence, and that civilians reported about 100 more had been taken with the Union troops during the retreat. McPheeters also noted seeing the bodies of dead Union soldiers strewn along the road from the river to Independence. Historian Mark Lause estimates that the Union may have lost up to about 300 men, and the Confederates more. Shelby later described the fight as the beginning of significant difficulties for his division during the campaign.

The day after the battle, Price sent Shelby south of Curtis's main line along the Big Blue River. In the initial stages of the Battle of Byram's Ford, Shelby's men forced their way across the Big Blue River, causing Curtis to order a withdrawal to

U.S. National Park Service CWSAC Battle Summary

{{DEFAULTSORT:Little Blue, Action At The Little Blue Little Blue Little Blue Little Blue Jackson County, Missouri Little Blue 1864 in Missouri October 1864 events

Price's Raid

Price's Missouri Expedition (August 29 – December 2, 1864), also known as Price's Raid or Price's Missouri Raid, was an unsuccessful Confederate cavalry raid through Arkansas, Missouri, and Kansas in the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the Am ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

. Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Sterling Price

Major-General Sterling "Old Pap" Price (September 14, 1809 – September 29, 1867) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded infantry in the Western and Trans-Mississippi theaters of the American Civil War. Prior to ...

of the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

led an army into Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

in September 1864 with hopes of challenging Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

control of the state. During the early stages of the campaign, Price abandoned his plan to capture St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

and later his secondary target of Jefferson City

Jefferson City, informally Jeff City, is the capital of Missouri, United States. It had a population of 43,228 at the 2020 census, ranking as the 15th most populous city in the state. It is also the county seat of Cole County and the principa ...

. The Confederates then began moving westwards, brushing aside Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

James G. Blunt's Union force in the Second Battle of Lexington

The Second Battle of Lexington was a minor battle fought during Price's Raid as part of the American Civil War. Hoping to draw Union Army forces away from more important theaters of combat and potentially affect the outcome of the 1864 United ...

on October 19. Two days later, Blunt left part of his command under the authority of Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

Thomas Moonlight

Thomas Moonlight (September 30, 1833February 7, 1899) was a United States politician and soldier. Moonlight served as Governor of Wyoming Territory from 1887 to 1889.

Birth

Moonlight was born in Forfarshire, Scotland. He was baptized on 30 Sep ...

to hold the crossing of the Little Blue River, while the rest of his force fell back to Independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

. On the morning of October 21, Confederate troops attacked Moonlight's line, and parts of Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

John B. Clark Jr.'s brigade forced their way across the river. A series of attacks and counterattack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in "war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objectives typically seek ...

s ensued, neither side gaining a significant advantage.

Meanwhile, Blunt had received permission from Major General Samuel R. Curtis to make a stand at the Little Blue River, and he and Curtis returned to the field with reinforcements that brought total Union strength up to about 2,800 men. More Confederate soldiers from the divisions of Brigadier Generals Joseph O. Shelby and John S. Marmaduke arrived on the field, bringing Confederate strength to about 5,500 men. One regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscript ...

of Confederate cavalry threatened the Union flank

Flank may refer to:

* Flank (anatomy), part of the abdomen

** Flank steak, a cut of beef

** Part of the external anatomy of a horse

* Flank speed, a nautical term

* Flank opening, a chess opening

* A term in Australian rules football

* Th ...

, and Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson

Brigadier-General M. Jeff Thompson (January 22, 1826 – September 5, 1876), nicknamed "Swamp Fox," was a senior officer of the Missouri State Guard who commanded cavalry in the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War. The () ...

's Confederate brigade pressed the Union center. The Union line fell back and the fighting largely ending around 16:00, when the Union troops reached Independence. The Union soldiers later fell back to the Big Blue River, abandoning Independence.

The next day Union soldiers commanded by Major General Alfred Pleasonton

Alfred Pleasonton (June 7, 1824 – February 17, 1897) was a United States Army officer and major general of volunteers in the Union cavalry during the American Civil War. He commanded the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac during the Ge ...

forced their way across the Little Blue River and retook Independence from the Confederates during the Second Battle of Independence. On October 23, the Confederates were defeated by Curtis and Pleasonton at the Battle of Westport

The Battle of Westport, sometimes referred to as the "Gettysburg of the West", was fought on October 23, 1864, in modern Kansas City, Missouri, during the American Civil War. Union forces under Major General Samuel R. Curtis decisively defeate ...

, forcing Price's men to retreat from Missouri.

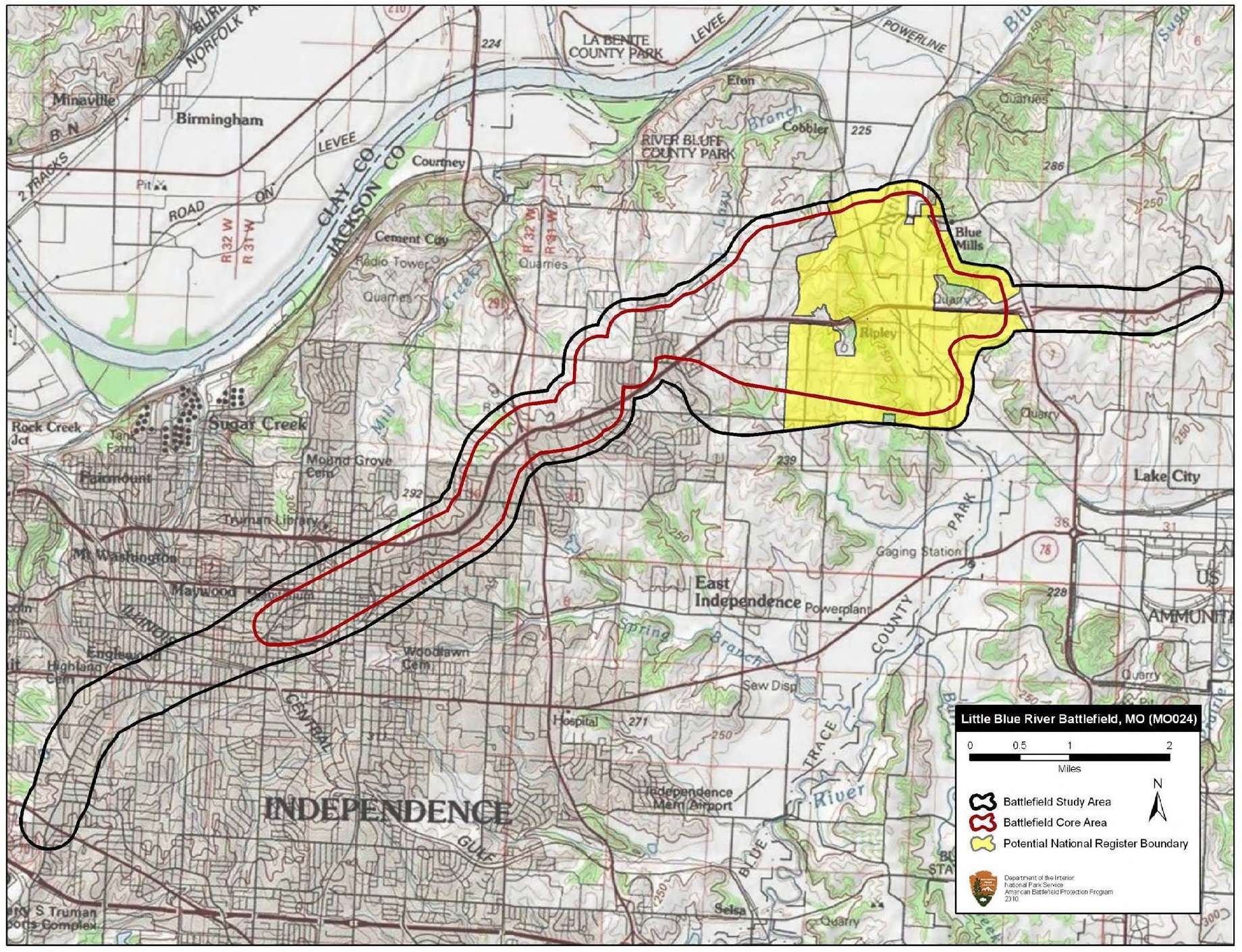

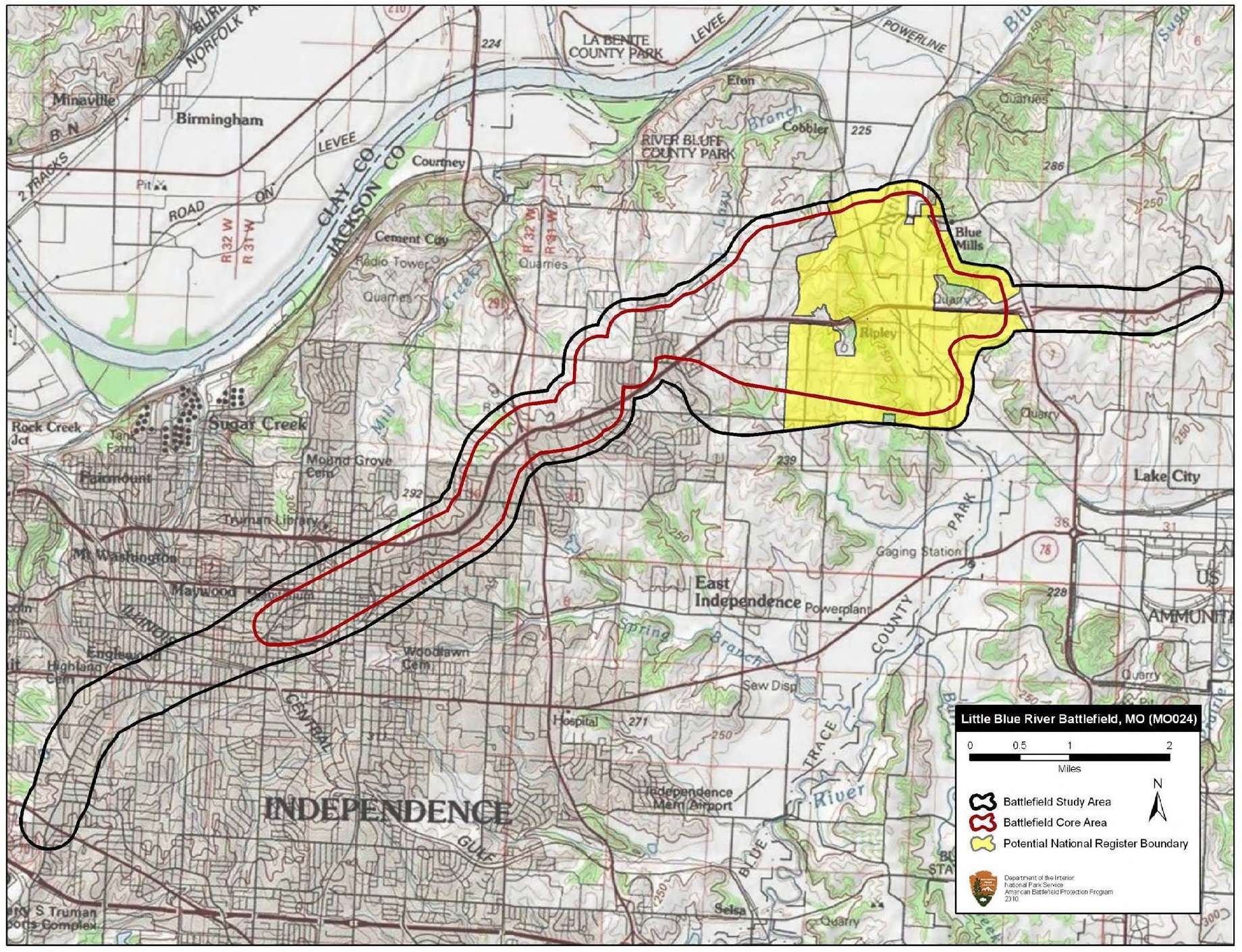

A study published by the American Battlefield Protection Program in 2011 determined that the Little Blue River battlefield was in fragmented condition and was threatened by highway development. It found that part of the site was potentially eligible to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

.

Background

At the start of the

At the start of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

in 1861, the state of Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

was a slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

, but did not secede

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics l ...

. However, the state was politically divided: Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

Claiborne Fox Jackson

Claiborne Fox Jackson (April 4, 1806 – December 6, 1862) was an American politician of the Democratic Party in Missouri. He was elected as the 15th Governor of Missouri, serving from January 3, 1861, until July 31, 1861, when he was for ...

and the Missouri State Guard

The Missouri State Guard (MSG) was a military force established by the Missouri General Assembly on May 11, 1861. While not a formation of the Confederate States Army, the Missouri State Guard fought alongside Confederate troops and, at variou ...

(MSG) supported secession and the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

, while Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

Nathaniel Lyon

Nathaniel Lyon (July 14, 1818 – August 10, 1861) was the first Union general to be killed in the American Civil War. He is noted for his actions in Missouri in 1861, at the beginning of the conflict, to forestall secret secessionist plans of th ...

led Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. It proved essential to th ...

forces in Missouri that remained loyal to the United States and opposed secession. Under Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

Sterling Price

Major-General Sterling "Old Pap" Price (September 14, 1809 – September 29, 1867) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded infantry in the Western and Trans-Mississippi theaters of the American Civil War. Prior to ...

, the MSG defeated Union armies at the battles of Wilson's Creek and Lexington in 1861, but by the end of the year, the secessionist forces were restricted to the southwestern portion of the state by Union reinforcements. Meanwhile, Jackson and a portion of the state legislature voted to secede and join the Confederate States of America, while another element of the legislature voted to reject secession, essentially giving the state two governments. In March 1862, a Confederate defeat at the Battle of Pea Ridge

The Battle of Pea Ridge (March 7–8, 1862), also known as the Battle of Elkhorn Tavern, took place in the American Civil War near Leetown, Arkansas, Leetown, northeast of Fayetteville, Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas. United States, Federal f ...

in Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

gave the Union control of Missouri, and Confederate activity in the state was largely restricted to guerrilla warfare and raids throughout 1862 and 1863.

By the beginning of September 1864, events in the eastern United States, especially the Confederate defeat in the Atlanta campaign, gave incumbent president Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, who supported continuing the war, an edge in the 1864 United States presidential election

The 1864 United States presidential election was the 20th quadrennial presidential election. It was held on Tuesday, November 8, 1864. Near the end of the American Civil War, incumbent President Abraham Lincoln of the National Union Party easily ...

over George B. McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

, who favored ending the war. At this point, the Confederacy had very little chance of winning the war. Meanwhile, in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, the Confederates had defeated Union attackers during the Red River campaign in Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, which took place from March through May. As events east of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

turned against the Confederates, General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

Edmund Kirby Smith

General Edmund Kirby Smith (May 16, 1824March 28, 1893) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded the Trans-Mississippi Department (comprising Arkansas, Missouri, Texas, western Louisiana, Arizona Territory and the Indi ...

, Confederate commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department

The Trans-Mississippi Department was a geographical subdivision of the Confederate States Army comprising Arkansas, Missouri, Texas, western Louisiana, Arizona Territory and the Indian Territory; i.e. all of the Confederacy west of the Mississi ...

, was ordered to transfer the infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

under his command to the fighting in the Eastern

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

*Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air Li ...

and Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

Theaters. This proved to be impossible, as the Union Navy

The Union Navy was the United States Navy (USN) during the American Civil War, when it fought the Confederate States Navy (CSN). The term is sometimes used carelessly to include vessels of war used on the rivers of the interior while they were un ...

controlled the Mississippi River, preventing a large-scale crossing. Despite having limited resources for an offensive, Smith decided that an attack designed to divert Union troops from the principal theaters of combat would have an effect equivalent to the proposed transfer of troops, by decreasing the Confederates' numerical disparity east of the Mississippi. Price and the new Confederate Governor of Missouri, Thomas Caute Reynolds

Thomas Caute Reynolds (October 11, 1821 – March 30, 1887) was the Confederate governor of Missouri from 1862 to 1865, succeeding upon the death of Claiborne F. Jackson after serving as lieutenant governor in exile. In 1864 he returned to the ...

, suggested that an invasion of Missouri would be an effective offensive; Smith approved the plan and appointed Price to command the offensive. Price expected that the offensive would create a popular uprising against Union control of Missouri, divert Union troops away from principal theaters of combat (many of the Union troops previously defending Missouri had been transferred out of the state, leaving the Missouri State Militia as the state's primary defensive force), and aid McClellan's chance of defeating Lincoln in the election.

On September 19, Price's column, named the Army of Missouri

The Army of Missouri was an independent military formation during the American Civil War within the Confederate States Army, created in the fall of 1864 under the command of Maj. Gen. Sterling Price to invade Missouri. Price's Raid was unsuccessfu ...

, entered the state. The army was divided into three divisions, commanded by Major General James F. Fagan and Brigadier Generals John S. Marmaduke and Joseph O. Shelby. Marmaduke's division contained two brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

B ...

s, commanded by Brigadier General John B. Clark Jr. and Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

Thomas R. Freeman; Shelby's division had three brigades under Colonels David Shanks (replaced by Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson

Brigadier-General M. Jeff Thompson (January 22, 1826 – September 5, 1876), nicknamed "Swamp Fox," was a senior officer of the Missouri State Guard who commanded cavalry in the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War. The () ...

after Shanks was killed in action), Sidney D. Jackman, and Charles H. Tyler; and Fagan's division contained four brigades commanded by Brigadier General William L. Cabell and Colonels William F. Slemons, Archibald S. Dobbins

Colonel Archibald Stephenson Dobbins () was an officer of the Confederate army who commanded a cavalry regiment in the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War. Initially refusing to serve under Marmaduke after the Marmaduke-Walker ...

, and Thomas H. McCray

Thomas Hamilton McCray (1828 – Oct. 19, 1891) was an American inventor, a businessman and a Confederate States Army officer during the American Civil War.

Biography

Thomas McCray was born in 1828 near Jonesborough, Tennessee, to Henry and Marth ...

.

Prelude

When the campaign began, Price's force was composed of about 13,000 cavalrymen, but several thousand of these men were poorly armed, and all 14 of the army's cannons were of light caliber for artillery of the war. Countering Price was the UnionDepartment of Missouri

The Department of the Missouri was a command echelon of the United States Army in the 19th century and a sub division of the Military Division of the Missouri that functioned through the Indian Wars.

History

Background

Following the successful ...

, under the command of Major General William S. Rosecrans

William Starke Rosecrans (September 6, 1819March 11, 1898) was an American inventor, coal-oil company executive, diplomat, politician, and U.S. Army officer. He gained fame for his role as a Union general during the American Civil War. He was ...

, who had fewer than 10,000 men on hand. These soldiers, many of whom were militiamen

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

, were dispersed throughout the state. The Department of Missouri was composed of a series of districts and subdistricts charged with guarding specific local areas. While some of the militia organizations were well-trained, others were poorly armed and trained. While some had fought against guerrillas, experience in more traditional warfare was lacking. In late September, the Confederates encountered a small Union force holding Fort Davidson near the town of Pilot Knob. Attacks against the post in the Battle of Pilot Knob

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and forc ...

on September 27 failed, but the Union garrison abandoned the fort that night. Price had suffered hundreds of casualties in the battle, and decided to change his objective from St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

to Jefferson City. Price's army was accompanied by a sizable wagon train

''Wagon Train'' is an American Western series that aired 8 seasons: first on the NBC television network (1957–1962), and then on ABC (1962–1965). ''Wagon Train'' debuted on September 18, 1957, and became number one in the Nielsen ratings ...

, which significantly slowed its movement. The slow progress of the Confederates enabled Union forces to reinforce Jefferson City, whose garrison was increased from 1,000 men to 7,000 between October 1 and October 6. In turn, Price determined that Jefferson City was too strong to attack, and began moving westwards along the course of the Missouri River. The Confederates gathered recruits and supplies during the movement; a side raid against the town of Glasgow on October 15 was successful, as was another raid against Sedalia.

Meanwhile, Union troops commanded by Major General Samuel R. Curtis were withdrawn from their role in suppressing the Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enr ...

; the Kansas State Militia was mobilized. Major General James G. Blunt was also transferred from the Cheyenne conflict and began gathering a combination of Union Army troops and state militiamen at Paola, Kansas

Paola is a city in and the county seat of Miami County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 5,768.

History

Native Americans, then Spanish explorers such as Francisco Vásquez de Coronado in 1541, a ...

, near the Missouri-Kansas state border. George W. Dietzler, a major general in the Kansas State Militia, was appointed as its general-in-chief, although the troops were under Curtis's authority. The Kansas State Militia used a brigade organization, but little detail about the exact breakdown is provided in the ''Official Records of the War of the Rebellion

An official is someone who holds an office (function or mandate, regardless whether it carries an actual working space with it) in an organization or government and participates in the exercise of authority, (either their own or that of their su ...

''. While some of the militia were technically commanded by Blunt, the militia officers serving under Blunt still considered themselves to be part of the militia organization and attempted to adhere to their former command structure. The total strength of the mobilized militia amounted to about 15,000 men.

Dietzler's militia and Blunt's division were grouped under Curtis's command as a new formation known as the Army of the Border The Army of the Border was a Union army during the American Civil War. It was created from units in the Department of Kansas to oppose Sterling Price's Raid in 1864. Samuel R. Curtis was in command of the army throughout its duration.

Major Gener ...

. This army was split into two wings: one commanded by Dietzler and composed of the militia retained under his command, and other being Blunt's force. On October 14, or 15, Blunt moved his command to Hickman Mills, Missouri

Hickman Mills is a neighborhood of Kansas City, Missouri in the Kansas City metropolitan area. There is good access to the Interstate and Federal highway system, with I-435, I-470, and US-71/I-49 running through the area, including the Grandvi ...

, where he formed it into a three-brigade division; one of the brigades was composed of Kansas militia and was led by Colonel Charles W. Blair

Charles White Blair (February 5, 1829 – August 20, 1899) was a lawyer, and Union Army officer who served in three different regiments during the American Civil War. He fought primarily in the Trans-Mississippi Theater and was notable during Pri ...

. The two brigades composed of the Union Army troops were commanded by Colonels Charles R. "Doc" Jennison and Thomas Moonlight

Thomas Moonlight (September 30, 1833February 7, 1899) was a United States politician and soldier. Moonlight served as Governor of Wyoming Territory from 1887 to 1889.

Birth

Moonlight was born in Forfarshire, Scotland. He was baptized on 30 Sep ...

. Blair's command was hampered by his militia units still viewing militia officer William Fishback as their proper commander. Jennison's brigade contained one cavalry regiment and part of another, Moonlight's was composed of one cavalry regiment and parts of two others, and Blair's contained one Union cavalry regiment and three militia units. Each brigade was assigned an artillery battery; Blair's brigade was given an extra artillery section as well. This allotment resulted in Jennison's brigade having five cannons, Moonlight's four, and Blair's eight.

Price halted at Marshall

Marshall may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Marshall, Victoria, a suburb of Geelong, Victoria

Canada

* Marshall, Saskatchewan

* The Marshall, a mountain in British Columbia

Liberia

* Marshall, Liberia

Marshall Islands

* Marshall Islands, an i ...

on October 15, east of Blunt's column. The next day, Curtis moved most of the Kansas militiamen not assigned to Blunt to Kansas City, Missouri, but was prohibited by Thomas Carney

Thomas Carney (August 20, 1824 – July 28, 1888) was the second Governor of Kansas.

Biography

Carney was born in Delaware County, Ohio, to James and Jane (Ostrander) Carney. James died in 1828, leaving a widow and four young sons. Thomas re ...

, the governor of Kansas, from taking them east of the Big Blue River. Curtis had previously promised Carney that the militia would only travel as far as was necessary to protect Kansas. On the 17th, Blunt detached his militia brigade to Kansas City, and then sent his other two brigades to Holden.

On October 18, Blunt's advance guard

The vanguard (also called the advance guard) is the leading part of an advancing military formation. It has a number of functions, including seeking out the enemy and securing ground in advance of the main force.

History

The vanguard derives f ...

, commanded by Moonlight, occupied the town of Lexington, hoping to cooperate with a force commanded by Brigadier General John B. Sanborn to catch and trap Price. However, Sanborn's force was too far south of Lexington to move in concert with Blunt. Additionally, Blunt learned that Price was only away at Waverly; he also received word from Curtis that the political authorities in Kansas would not allow the latter to send more militiamen to Blunt. Blunt then made the decision to reinforce his outer positions and resist the anticipated Confederate advance. Shelby's division attacked the Union line at Lexington on October 19, beginning the Second Battle of Lexington

The Second Battle of Lexington was a minor battle fought during Price's Raid as part of the American Civil War. Hoping to draw Union Army forces away from more important theaters of combat and potentially affect the outcome of the 1864 United ...

, but Blunt's troops held. The Union troops retreated once Price deployed men of Fagan's and Marmaduke's divisions into the fray.

Battle

Moonlight's stand

After the battle at Lexington, Blunt's forces fell back to the west, Moonlight's brigade serving as the

After the battle at Lexington, Blunt's forces fell back to the west, Moonlight's brigade serving as the rear guard

A rearguard is a part of a military force that protects it from attack from the rear, either during an advance or withdrawal. The term can also be used to describe forces protecting lines, such as communication lines, behind an army. Even more ...

. Early on the morning of October 20, Blunt decided to halt and defend a position east of the Little Blue River. Blunt requested reinforcements from Curtis, but the restrictions on the movement of the Kansas Militia prevented Blunt from being reinforced at the Little Blue River. Curtis therefore ordered Blunt to leave a holding force at the Little Blue River and fall back to the Big Blue River. Blunt argued for a stand at the river but complied with his orders, falling back to Independence

Independence is a condition of a person, nation, country, or state in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the statu ...

that evening. The 11th Kansas Cavalry Regiment, supported by four cannons, was left behind to serve as a rear guard under Moonlight's command. The strength of this force amounted to either 400 or 600 men. Two companies of the 11th Kansas Cavalry and the cannons were placed at a bridge over the river with instructions to burn it when the Confederates arrived, while single companies guarded fords, one within either or north of the bridge and the other to the south of the bridge. The remainder of the 11th Kansas Cavalry was held as a reserve. Despite these precautions, other fords closer to the bridge were left unguarded, and the river was shallow enough to be crossed at many points. The defenders simply were not familiar with the terrain, while some of the Missouri Confederates were. Union prisoners informed Price that a stand would be made at the Little Blue.

The Confederates struck at about 07:00 on the morning of October 21, the advance being led by Company D of the 5th Missouri Cavalry Regiment. The Confederate company lost over a third of its strength in a sharp fight with Union skirmishers

Skirmishers are light infantry or light cavalry soldiers deployed as a vanguard, flank guard or rearguard to screen a tactical position or a larger body of friendly troops from enemy advances. They are usually deployed in a skirmish line, an i ...

, who were eventually driven across the bridge. After Confederate pressure grew strong enough that the defenders at the bridge determined that they would not be able to hold out, they set fire to the bridge. Meanwhile, Clark's Confederate brigade arrived, and Marmaduke sent the 4th Missouri Cavalry Regiment to find a ford south of the bridge, while the 10th Missouri Cavalry Regiment found a crossing about halfway between the bridge and the Union company stationed north of it. The northward Union company was outflanked and retreated, later rejoining other parts of their regiment. Clark, in turn, ordered more of his brigade to cross behind the 10th Missouri Cavalry. The ford soon became congested, slowing Confederate movements.

The Union troops holding the burning bridge also retreated, although the Confederates were able to put out the flames, rendering it still usable.

The 11th Kansas Cavalry, with the exception of the isolated company to the south, retreated to a hilltop line marked by a stone wall. Moonlight's four cannons were deployed here as well. The 10th Missouri Cavalry pursued them uphill and attacked, but was repulsed in disarray by the Kansans and the fire from their repeating rifles. Confederate Colonel Colton Greene was able to get his 3rd Missouri Cavalry Regiment across the ford, although the men of the 10th Missouri Cavalry had already routed. Three cannons from Harris's Missouri Battery also crossed, and moved into a position to support Greene. The whole of the 11th Kansas Cavalry Regiment counterattack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in "war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objectives typically seek ...

ed, while the 3rd Missouri Cavalry Regiment was only about 150 men strong. Once the combat reached close quarters, the Confederate artillery was no longer effective, as the risk of accidental friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy/hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while en ...

was too great. Instead, the cannoneers fired blanks in an attempt to mislead the Union troops into thinking they were under heavy artillery fire. The Kansans retreated, and Greene believed that the blank cartridge ruse had been effective. The two sides engaged in a series of counterattacks, neither gaining a significant advantage.

Blunt arrives

Meanwhile, Blunt had been able to get permission from Curtis to fight at the Little Blue River. Blunt then began a return from Independence to the river, bringing his non-militia units and 900 men and six cannons under the command of Colonel James H. Ford. Ford's command consisted of McLain's Colorado Battery, part of the 16th Kansas Cavalry Regiment, and the2nd Colorado Cavalry Regiment

The 2nd Regiment Colorado Cavalry was a cavalry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Service

The 2nd Colorado Cavalry was organized at St. Louis, Missouri, by consolidation of the 2nd Colorado Infantry and 3rd ...

, which were transferred from Curtis's command to Blunt's, becoming a fourth brigade for the latter. The 2nd Colorado Cavalry has previously been sent by Rosecrans to Curtis and McLain's battery had been stationed at Paola until October. Two regiments from Jennison's brigade also accompanied Blunt. Back at the Little Blue River, Clark's brigade had finally gotten across the river. Around 11:00, Moonlight observed some of Shelby's men approaching in support of Clark's brigade. Despite being farther from the battlefield than Fagan's division, Shelby's division was committed to the fighting, as it was considered more reliable. Blunt's command also arrived on the field at about 11:00. By then, Moonlight's force had fallen back to about from the river. Between the commands of Moonlight and Blunt, there were about 2,600 Union men on the field, with the support of 15 cannons. The two regiments from Jennison's brigade supported the Union right, while Ford's men moved to the left. Elements of both Marmaduke's and Shelby's divisions totaling about 5,500 men were present. While numerically inferior, the Union troops had superior firepower. The Union line was held on the left by the 15th Kansas Cavalry Regiment, which was supported by five cannons. The Union line stretched to the north, with the 3rd Wisconsin Cavalry Regiment next to the 15th Kansas Cavalry, followed by the 2nd Colorado Cavalry Regiment, McLain's battery, the 16th Kansas Cavalry Regiment, and the 11th Kansas Cavalry. Four cannons supported the 11th Kansas Cavalry. About one quarter of the Union soldiers were sent to the rear to hold the men's horses. The men from both sides were deployed dismounted.

The increased Union numbers began to put substantial pressure on Greene's regiment. Wood's Missouri Cavalry Battalion arrived to reinforce Greene, and aligned in an orchard. After some fighting and a Union counterattack, the Confederates began to run low on ammunition and started a retreat, which was accompanied by Harris's Battery. Just as the Confederate line was beginning to collapse, the 7th Missouri Cavalry Regiment and Davies's Missouri Cavalry Battalion of Clark's brigade arrived to shore up the line. Additionally, Thompson's brigade of Shelby's division crossed over and deployed to the left of Clark's brigade. After Thompson's men made it across the river, Shelby also fed Jackman's brigade into the fight. Shelby then ordered an assault against the Union line. Most of Jackman's brigade was inexperienced and made little progress, but Nichols's Missouri Cavalry Regiment, which was still mounted, advanced against the Union left flank. Curtis arrived on the battlefield at 13:00, accompanied by two more cannons. There were now about 2,800 Union troops on the field. Curtis noticed Nichols's unit's incursion towards the Union flank, and sent McLain's Battery and two other cannons to counter the threat; as these cannons were taken from other parts of the Union lines, it weakened the Union center.

Shelby took advantage of the weakened Union center by pressing the attack harder. Thompson's men began pushing forward. Complicating matters for the Union soldiers was Curtis's decision to send the wagons containing more ammunition back to Independence. With ammunition running low, Nichols's men threatening one flank, and Thompson pressing the Union center, the Union troops began conducting a fighting withdrawal. Blunt placed Ford in charge of the rear guard, although in practice, Moonlight shared command responsibility with Ford, whose men conducted a rear guard maneuver in which the men deployed in two ranks. The front rank resisted the Confederate pursuit until falling back behind the second rank, after which the process was repeated. During the retreat, McLain's Battery was caught in an exposed position, but was rescued by a counterattack made by elements of the 11th Kansas Cavalry. Later, these elements of the 11th Kansas Cavalry were also stuck in an exposed position and had to be rescued by a charge from the 2nd Colorado Cavalry. The 11th and 16th Kansas Cavalry and McLain's battery made a stand on a ridge east of Independence, the 16th even making a brief counterattack, but this position had become indefensible by around 15:00 and was abandoned. The Confederates had become disorganized and Blunt used a lull in the fighting to begin to form a line at Independence. By 16:00 large-scale fighting had ended. The retreat to Independence had been over . Later that afternoon, Blunt ordered a retreat to the Big Blue River, which was lightly pursued by the Confederates. Some skirmishing occurred within Independence itself during the retreat. A detail of Union soldiers destroyed some army supplies in the town, while civilians within the town took potshots at the retreating Union troopers. It is not known if the civilian gunmen were pro-Confederates, or were under the mistaken belief that the Union soldiers were guerrillas in captured uniforms, or if they were attempting to hamper the destruction of military supplies, hoping to take them themselves. By nightfall, Curtis's men were on the west side of the Big Blue River, and Price's army was in the Independence area.

Aftermath and preservation

Official casualty numbers are only known for a few units on each side. The 11th and 15th Kansas Cavalries and the 2nd Colorado Cavalry combined had 20 men killed. On the Confederate side, the 3rd Missouri Cavalry Regiment suffered 31 killed and wounded, while a total of three men were killed between Davies's battalion and the 10th Missouri Cavalry Regiment. Among the Union dead was Major Nelson Smith of the 2nd Colorado Cavalry, while Confederate guerrilla leader George Todd was also killed. Todd had led a group of guerrillas during the battle; he was shot in the throat during the final stages of the action. Confederate surgeon William McPheeters reported that 10 wounded Union soldiers were left in Independence, and that civilians reported about 100 more had been taken with the Union troops during the retreat. McPheeters also noted seeing the bodies of dead Union soldiers strewn along the road from the river to Independence. Historian Mark Lause estimates that the Union may have lost up to about 300 men, and the Confederates more. Shelby later described the fight as the beginning of significant difficulties for his division during the campaign.

The day after the battle, Price sent Shelby south of Curtis's main line along the Big Blue River. In the initial stages of the Battle of Byram's Ford, Shelby's men forced their way across the Big Blue River, causing Curtis to order a withdrawal to

Official casualty numbers are only known for a few units on each side. The 11th and 15th Kansas Cavalries and the 2nd Colorado Cavalry combined had 20 men killed. On the Confederate side, the 3rd Missouri Cavalry Regiment suffered 31 killed and wounded, while a total of three men were killed between Davies's battalion and the 10th Missouri Cavalry Regiment. Among the Union dead was Major Nelson Smith of the 2nd Colorado Cavalry, while Confederate guerrilla leader George Todd was also killed. Todd had led a group of guerrillas during the battle; he was shot in the throat during the final stages of the action. Confederate surgeon William McPheeters reported that 10 wounded Union soldiers were left in Independence, and that civilians reported about 100 more had been taken with the Union troops during the retreat. McPheeters also noted seeing the bodies of dead Union soldiers strewn along the road from the river to Independence. Historian Mark Lause estimates that the Union may have lost up to about 300 men, and the Confederates more. Shelby later described the fight as the beginning of significant difficulties for his division during the campaign.

The day after the battle, Price sent Shelby south of Curtis's main line along the Big Blue River. In the initial stages of the Battle of Byram's Ford, Shelby's men forced their way across the Big Blue River, causing Curtis to order a withdrawal to Brush Creek

A brush is a common tool with bristles, wire or other filaments. It generally consists of a handle or block to which filaments are affixed in either a parallel or perpendicular orientation, depending on the way the brush is to be gripped durin ...

. Meanwhile, Union cavalry commanded by Major General Alfred Pleasonton

Alfred Pleasonton (June 7, 1824 – February 17, 1897) was a United States Army officer and major general of volunteers in the Union cavalry during the American Civil War. He commanded the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac during the Ge ...

attacked Price's rear guard from the east in the Second Battle of Independence. After pushing across the Little Blue River, Pleasonton's men struck Cabell's Confederate brigade, capturing both men and two cannons, as well as taking the town of Independence. On October 23, Price's men fought the Battle of Westport

The Battle of Westport, sometimes referred to as the "Gettysburg of the West", was fought on October 23, 1864, in modern Kansas City, Missouri, during the American Civil War. Union forces under Major General Samuel R. Curtis decisively defeate ...

, where they were defeated by Curtis's and Pleasonton's commands. The Confederates began retreating through Kansas, before reentering Missouri on October 25. Price's survivors eventually reached Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

via Arkansas and the Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans who held aboriginal title to their land as a sovereign ...

, suffering several defeats along the way. Price lost over two thirds of his men during the campaign.

A study published by the American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) in 2011 determined that the Little Blue River battlefield was fragmented, but that there was still potential for future preservation. The study also noted that the site was threatened by highway construction. The battlefield is not listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic ...

, but the ABPP found that are potentially eligible for listing. At the site, are currently under some form of permanent protection. There is public interpretation at the site but no visitor's center. A driving tour, with interpretative markers, has been established for the battlefields of Little Blue and Second Independence together. The site is part of Freedom's Frontier National Heritage Area and the Civil War Roundtable of Western Missouri acts as a battlefield friends group.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

U.S. National Park Service CWSAC Battle Summary

{{DEFAULTSORT:Little Blue, Action At The Little Blue Little Blue Little Blue Little Blue Jackson County, Missouri Little Blue 1864 in Missouri October 1864 events