Battle of Kennesaw Mountain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Kennesaw Mountain was fought on June 27, 1864, during the Atlanta Campaign of the

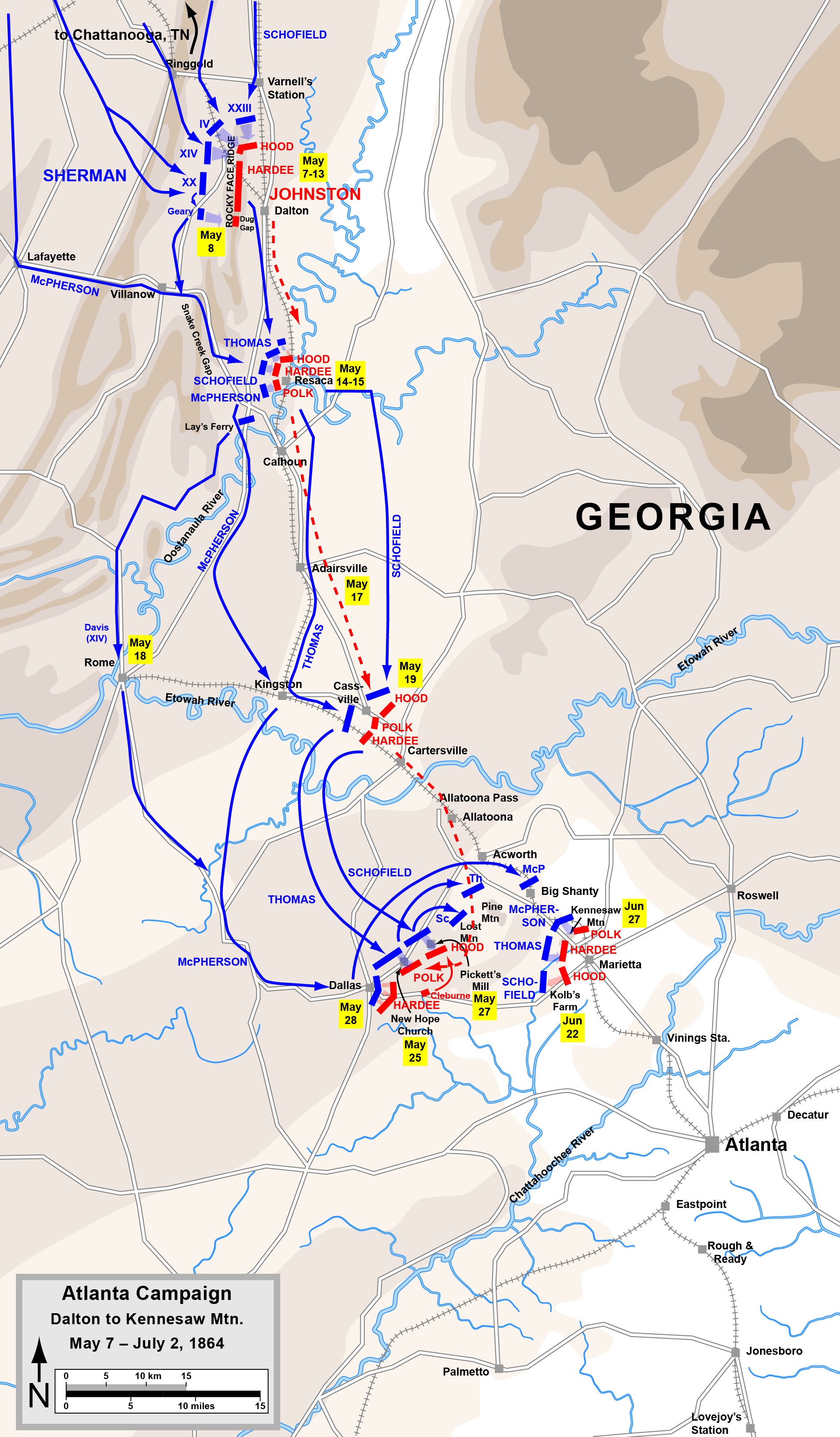

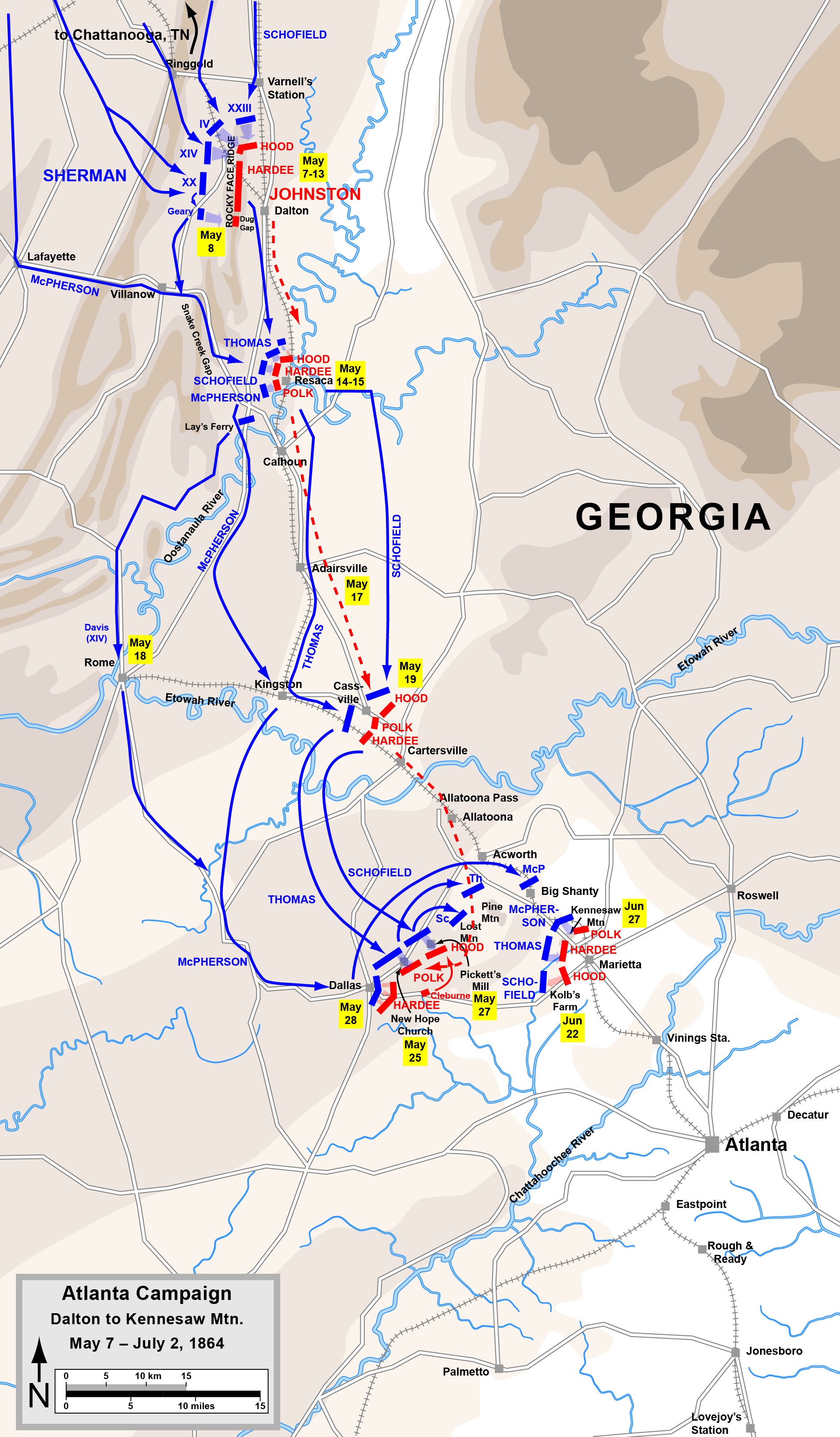

Sherman's campaign began on May 7, as his three armies departed from the vicinity of Chattanooga. He launched demonstration attacks against Johnston's position on the long, high mountain named

Sherman's campaign began on May 7, as his three armies departed from the vicinity of Chattanooga. He launched demonstration attacks against Johnston's position on the long, high mountain named

On the right of Smith's attack, the brigade of Brig. Gen.

On the right of Smith's attack, the brigade of Brig. Gen.

Sherman's armies suffered about 3,000 casualties in comparison to Johnston's 1,000. The Union general was not initially deterred by these losses and he twice asked Thomas to renew the assault. "Our loss is small, compared to some of those

Sherman's armies suffered about 3,000 casualties in comparison to Johnston's 1,000. The Union general was not initially deterred by these losses and he twice asked Thomas to renew the assault. "Our loss is small, compared to some of those

''The Civil War Battlefield Guide''

2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. . * Liddell Hart, B. H. ''Sherman: Soldier, Realist, American''. New York: Da Capo Press, 1993. . First published in 1929 by Dodd, Mead & Co. * Livermore, Thomas L. ''Numbers and Losses in the Civil War in America 1861–65''. Reprinted with errata, Dayton, OH: Morninside House, 1986. . First published 1901 by Houghton Mifflin. * Luvaas, Jay, and Harold W. Nelson, eds. ''Guide to the Atlanta Campaign: Rocky Face Ridge to Kennesaw Mountain''. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2008. . * McDonough, James Lee, and James Pickett Jones. ''War So Terrible: Sherman and Atlanta''. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1987, . * McMurry, Richard M. ''Atlanta 1864: Last Chance for the Confederacy''. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000. . * McPherson, James M. '' Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era''. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. . * Welcher, Frank J. ''The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations''. Vol. 2, ''The Western Theater''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993. .

National Park Service battle description

Battle maps, history articles, and preservation news (

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

. It was the most significant frontal assault launched by Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman against the Confederate Army of Tennessee

The Army of Tennessee was the principal Confederate army operating between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River during the American Civil War. It was formed in late 1862 and fought until the end of the war in 1865, participating in ...

under Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, ending in a tactical defeat for the Union forces. Strategically, however, the battle failed to deliver the result that the Confederacy desperately needed—namely a halt to Sherman's advance on Atlanta.

Sherman's 1864 campaign against Atlanta, Georgia

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,71 ...

, was initially characterized by a series of flanking maneuvers against Johnston, each of which compelled the Confederate army to withdraw from heavily fortified positions with minimal casualties on either side. After two months and of such maneuvering, Sherman's path was blocked by imposing fortifications on Kennesaw Mountain, near Marietta, Georgia

Marietta is a city in and the county seat of Cobb County, Georgia, United States. At the 2020 census, the city had a population of 60,972. The 2019 estimate was 60,867, making it one of Atlanta's largest suburbs. Marietta is the fourth largest ...

, and the Union general chose to change his tactics and ordered a large-scale frontal assault on June 27. Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson feinted against the northern end of Kennesaw Mountain, while his corps under Maj. Gen. John A. Logan assaulted Pigeon Hill on its southwest corner. At the same time, Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas launched strong attacks against Cheatham Hill at the center of the Confederate line. Both attacks were repulsed with heavy losses, but a demonstration by Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield

John McAllister Schofield (September 29, 1831 – March 4, 1906) was an American soldier who held major commands during the American Civil War. He was appointed U.S. Secretary of War (1868–1869) under President Andrew Johnson and later served a ...

achieved a strategic success by threatening the Confederate army's left flank, prompting yet another Confederate withdrawal toward Atlanta and the removal of General Johnston from command of the army.

Background

In March 1864, Ulysses S. Grant was promoted tolieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

and named general in chief of the Union Army. He devised a strategy of multiple, simultaneous offensives against the Confederacy, hoping to prevent any of the rebel armies from reinforcing the others over interior lines. The two most significant of these were by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade's Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the principal Union Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the surrender of the Confede ...

, accompanied by Grant himself, which would attack Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nort ...

's army directly and advance toward the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

; and Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, replacing Grant in his role as commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi, who would advance from Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, it also extends into Marion County, Tennessee, Marion County on its west ...

, to Atlanta.

Both Grant and Sherman initially had objectives to engage with and destroy the two principal armies of the Confederacy, relegating the capture of important enemy cities to a secondary, supporting role. This was a strategy that President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese f ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

had emphasized throughout the war, but Grant was the first general who actively cooperated with it. As their campaigns progressed, however, the political importance of the cities of Richmond and Atlanta began to dominate their strategy. By 1864, Atlanta was a critical target. The city of 20,000 was founded at the intersection of four important railroad lines that supplied the Confederacy and was a military manufacturing arsenal in its own right. Atlanta's nickname of "Gate City of the South" was apt—its capture would open virtually the entire Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the war ...

to Union conquest. Grant's orders to Sherman were to "move against Johnston's Army, to break it up and to get into the interior of the enemy's country as far as you can, inflicting all the damage you can against their War resources."

Sherman's force of about 100,000 men was composed of three subordinate armies: the Army of the Tennessee

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

(Grant's and later Sherman's army of 1862–63) under Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson; the Army of the Cumberland

The Army of the Cumberland was one of the principal Union armies in the Western Theater during the American Civil War. It was originally known as the Army of the Ohio.

History

The origin of the Army of the Cumberland dates back to the creatio ...

under Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas; and the relatively small Army of the Ohio

The Army of the Ohio was the name of two Union armies in the American Civil War. The first army became the Army of the Cumberland and the second army was created in 1863.

History

1st Army of the Ohio

General Orders No. 97 appointed Maj. Gen. ...

(composed of only the XXIII Corps) under Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield

John McAllister Schofield (September 29, 1831 – March 4, 1906) was an American soldier who held major commands during the American Civil War. He was appointed U.S. Secretary of War (1868–1869) under President Andrew Johnson and later served a ...

. Their principal opponent was the Confederate Army of Tennessee

The Army of Tennessee was the principal Confederate army operating between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River during the American Civil War. It was formed in late 1862 and fought until the end of the war in 1865, participating in ...

, commanded by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, who had replaced the unpopular Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was an American army officer during the Second Seminole War and Mexican–American War and Confederate general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, serving in the Wes ...

after his defeat in Chattanooga

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

in November 1863. The 50,000-man army consisted of the infantry corps of Lt. Gens. William J. Hardee

William Joseph Hardee (October 12, 1815November 6, 1873) was a career United States Army, U.S. Army and Confederate States Army officer. For the U.S. Army, he served in the Second Seminole War and in the Mexican–American War, where he was capt ...

, John Bell Hood

John Bell Hood (June 1 or June 29, 1831 – August 30, 1879) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Although brave, Hood's impetuosity led to high losses among his troops as he moved up in rank. Bruce Catton wrote that "the de ...

, and Leonidas Polk

Lieutenant-General Leonidas Polk (April 10, 1806 – June 14, 1864) was a bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Louisiana and founder of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America, which separated from the Episcopal Ch ...

, and a cavalry corps under Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler

Joseph "Fighting Joe" Wheeler (September 10, 1836 – January 25, 1906) was an American military commander and politician. He was a cavalry general in the Confederate States Army in the 1860s during the American Civil War, and then a general in ...

.

Start of the Atlanta campaign

Sherman's campaign began on May 7, as his three armies departed from the vicinity of Chattanooga. He launched demonstration attacks against Johnston's position on the long, high mountain named

Sherman's campaign began on May 7, as his three armies departed from the vicinity of Chattanooga. He launched demonstration attacks against Johnston's position on the long, high mountain named Rocky Face Ridge

The Battle of Rocky Face Ridge was fought May 7–13, 1864, in Whitfield County, Georgia, during the Atlanta Campaign of the American Civil War. The Union army was led by Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman and the Confederate army by G ...

while McPherson's Army of the Tennessee

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

advanced stealthily around Johnston's left flank toward the town of Resaca and Johnston's supply line on the Western & Atlantic Railroad. Unfortunately for Sherman, McPherson encountered a small Confederate force entrenched in the outskirts of Resaca and cautiously pulled back to Snake Creek Gap, squandering the opportunity to trap the Confederate army. As Sherman swung his entire army in the direction of Resaca, Johnston retired to take up positions there. Full scale fighting erupted in the Battle of Resaca

The Battle of Resaca, from May 13 to 15, 1864, formed part of the Atlanta Campaign during the American Civil War, when a Union force under William Tecumseh Sherman engaged the Confederate Army of Tennessee led by Joseph E. Johnston. The batt ...

on May 14–15 but there was no conclusive result and Sherman flanked Johnston for a second time by crossing the Oostanaula River

The Oostanaula River (pronounced "oo-stuh-NA-luh") is a principal tributary of the Coosa River, about long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed April 27, 2011 formed by the co ...

. As Johnston withdrew again, skirmishing erupted at Adairsville on May 17 and more general fighting on Johnston's Cassville line May 18–19. Johnston planned to defeat part of Sherman's force as it approached on multiple routes, but Hood became uncharacteristically cautious and feared encirclement, failing to attack as ordered. Encouraged by Hood and Polk, Johnston ordered another withdrawal, this time across the Etowah River

The Etowah River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed April 27, 2011 waterway that rises northwest of Dahlonega, Georgia, north of Atlanta. On Matthew Carey's 1795 ...

.

Johnston's army took up defensive positions at Allatoona Pass

Allatoona is an unincorporated community in Bartow County, in the U.S. state of Georgia. The community is located along Allatoona Creek, southeast of Cartersville. It was once a small mining community until a dam was erected at the base of t ...

south of Cartersville, but Sherman once again turned Johnston's left as he temporarily abandoned his railroad supply line and advanced on Dallas

Dallas () is the List of municipalities in Texas, third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of metropolitan statistical areas, fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 ...

. Johnston was forced to move from his strong position and meet Sherman's army in the open. Fierce but inconclusive fighting occurred on May 25 at New Hope Church, May 27 at Pickett's Mill

The Battle of Pickett's Mill (May 27, 1864) was fought in Paulding County, Georgia, between Union forces under Major General William Tecumseh Sherman and Confederate forces led by General Joseph E. Johnston during the Atlanta Campaign in the ...

, and May 28 at Dallas

Dallas () is the List of municipalities in Texas, third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of metropolitan statistical areas, fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 ...

. By June 1, heavy rains turned the roads to quagmires and Sherman was forced to return to the railroad to supply his men. Johnston's new line (called the Brushy Mountain Line

The Brushy Mountain Line or Lost Mountain Line was a military fortification line protecting Atlanta during the American Civil War.

It was built in the first days of June 1864, by the Confederate army in Cobb County early in the Atlanta Campaign ...

) was established by June 4 northwest of Marietta, along Lost Mountain, Pine Mountain, and Brush Mountain. On June 14, following eleven days of steady rain, Sherman was ready to move again. While on a personal reconnaissance, he spotted a group of Confederate officers on Pine Mountain and ordered one of his artillery batteries to open fire. Lt. Gen. Leonidas Polk

Lieutenant-General Leonidas Polk (April 10, 1806 – June 14, 1864) was a bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Louisiana and founder of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America, which separated from the Episcopal Ch ...

, the "Fighting Bishop," was killed and Johnston withdrew his men from Pine Mountain, establishing a new line in an arc-shaped defensive position from Kennesaw Mountain to Little Kennesaw Mountain. Hood's corps attempted an unsuccessful attack at Peter Kolb's farm (the Battle of Kolb's Farm

The Battle of Kolb's Farm (June 22, 1864) saw a Confederate corps under Lieutenant General John B. Hood attack parts of two Union corps under Major Generals Joseph Hooker and John Schofield. This action was part of the Atlanta campaign of ...

) south of Little Kennesaw Mountain on June 22. Maj. Gen. William W. Loring succeeded to temporarily command Polk's corps.

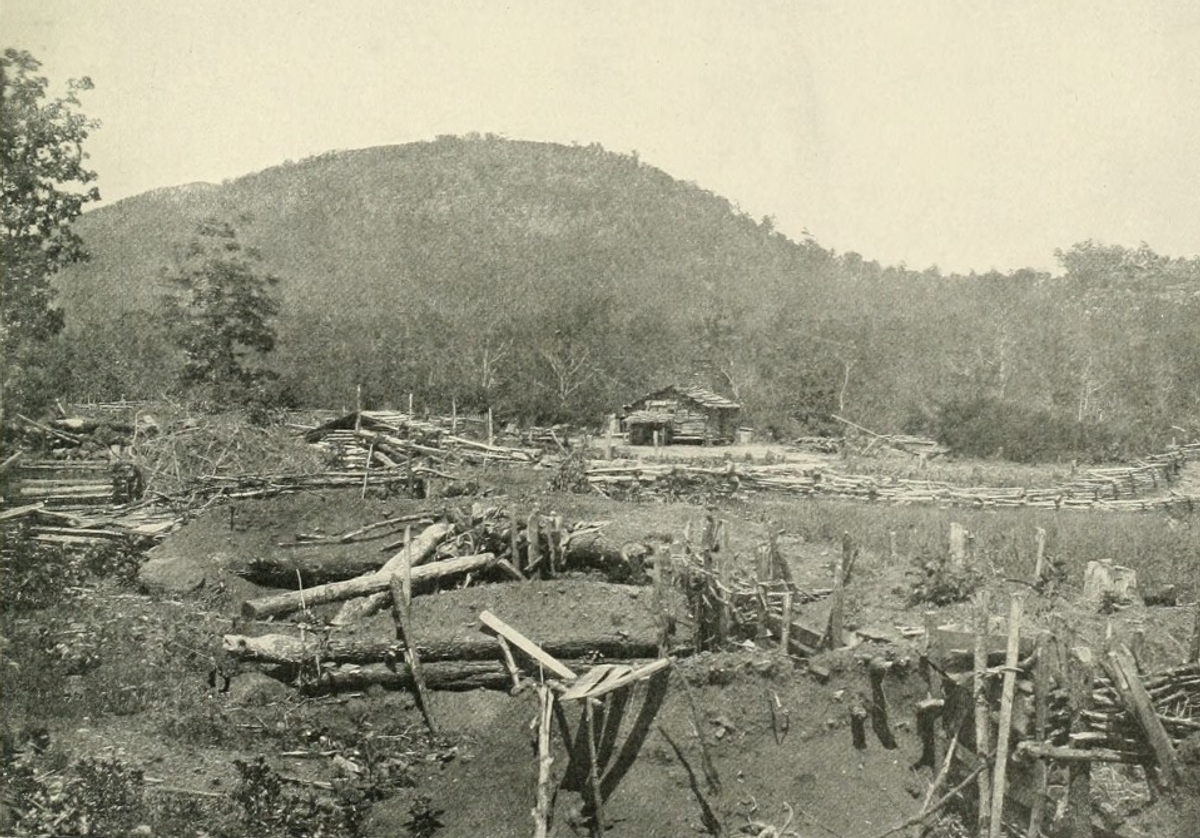

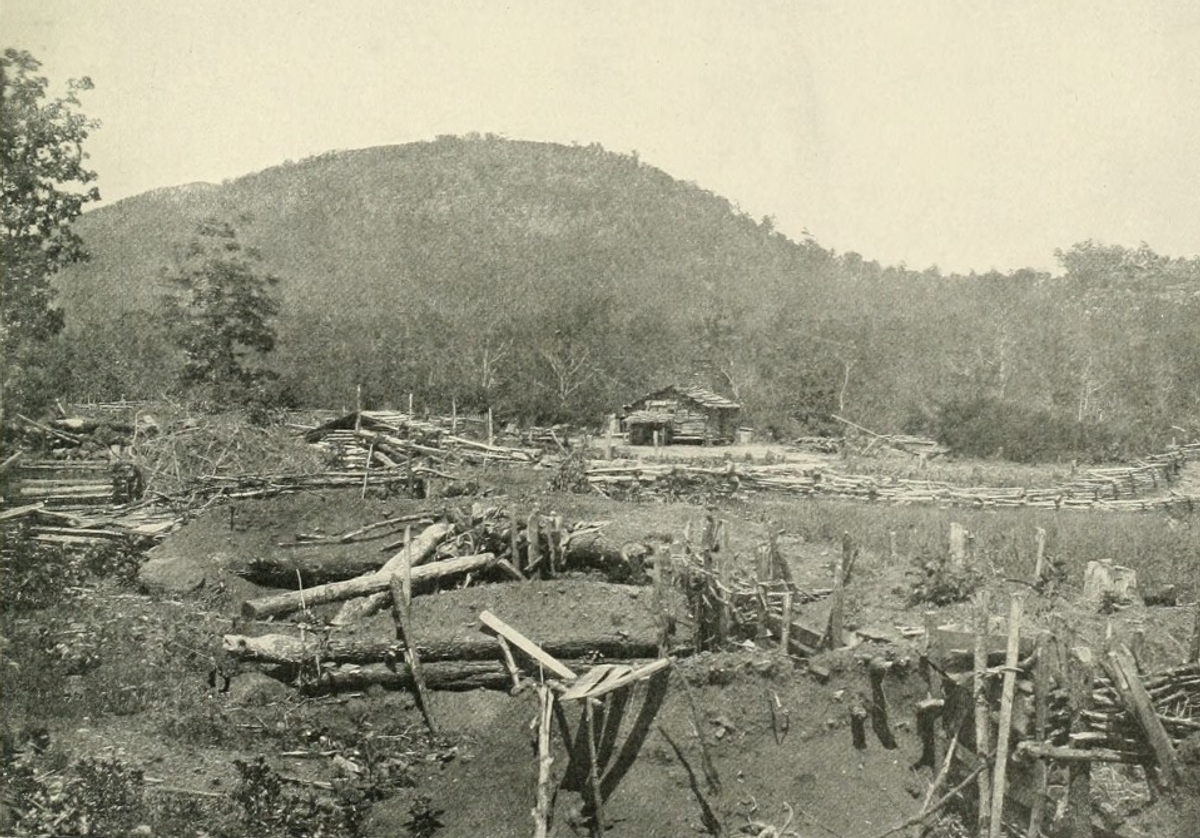

Sherman was in a difficult position, stalled north of Atlanta. He could not continue his strategy of moving around Johnston's flank because of the impassable roads, and his railroad supply line was dominated by Johnston's position on the top of Kennesaw Mountain. He reported to Washington "The whole country is one vast fort, and Johnston must have at least of connected trenches with abatis

An abatis, abattis, or abbattis is a field fortification consisting of an obstacle formed (in the modern era) of the branches of trees laid in a row, with the sharpened tops directed outwards, towards the enemy. The trees are usually interlaced ...

and finished batteries. We gain ground daily, fighting all the time. ... Our lines are now in close contact and the fighting incessant, with a good deal of artillery. As fast as we gain one position the enemy has another all ready. ... Kennesaw ... is the key to the whole country." Sherman decided to break the stalemate by attacking Johnston's position on Kennesaw Mountain. He issued orders on June 24 for an 8 a.m. attack on June 27.

Battle

Sherman's plan was first to induce Johnston to thin out and weaken his line by ordering Schofield to extend his army to the right. Then McPherson was to make a feint on his extreme left—the northern outskirts of Marietta and the northeastern end of Kennesaw Mountain—with his cavalry and a division of infantry, and to make a major assault on the southwestern end of Little Kennesaw Mountain. Meanwhile, Thomas's army was to conduct the principal attack against the Confederate fortifications in the center of their line, and Schofield was to demonstrate on the Confederate left flank and attack somewhere near the Powder Springs Road "as he can with the prospect of success." At 8 a.m. on June 27, Union artillery opened a furious bombardment with over 200 guns on the Confederate works and the Rebel artillery responded in kind. Lt. Col. Joseph S. Fullerton wrote, "Kennesaw smoked and blazed with fire, a volcano as grand as Etna." As the Federal infantry began moving soon afterward, the Confederates quickly determined that much of the wide advance consisted of demonstrations rather than concerted assaults. The first of those assaults began at around 8:30 a.m., with three brigades of Brig. Gen.Morgan L. Smith

Morgan Lewis Smith (March 8, 1822 – December 29, 1874) was a Union brigadier general in the American Civil War

Biography

Smith was born in Oswego County, New York. In 1843 he settled in Indiana, and later had some military experience in the Un ...

's division (Maj. Gen. John A. Logan's XV Corps, Army of the Tennessee) moving against Loring's corps on the southern end of Little Kennesaw Mountain and the spur known as Pigeon Hill near the Burnt Hickory Road. If the attack were successful, capturing Pigeon Hill would isolate Loring's corps on Kennesaw Mountain. All three brigades were disadvantaged by the approach through dense thickets, steep and rocky slopes, and a lack of knowledge of the terrain. About 5,500 Union troops in two columns of regiments moved against about 5,000 Confederate soldiers, well entrenched.

On the right of Smith's attack, the brigade of Brig. Gen.

On the right of Smith's attack, the brigade of Brig. Gen. Joseph A. J. Lightburn

Joseph Andrew Jackson Lightburn (September 21, 1824 – May 17, 1901) was a West Virginia farmer, soldier and Baptist Minister, most famous for his service as a Union general during the American Civil War.

Early life

Lightburn was born in ...

was forced to advance through a knee-deep swamp, and were stopped short of the Confederate breastworks on the southern end of Pigeon Hill by enfilading fire. They were able to overrun the rifle pits in front of the works, but could not pierce the main Confederate line. To their left, the brigades of Col. Charles C. Walcutt and Brig. Gen. Giles A. Smith crossed difficult terrain interrupted by steep cliffs and scattered with huge rocks to approach the Missouri brigade of Brig. Gen. Francis Cockrell

Francis Marion Cockrell (October 1, 1834December 13, 1915) was a Confederate military commander and American politician from the state of Missouri. He served as a United States senator from Missouri for five terms. He was a prominent membe ...

. Some of the troops were able to reach as far as the abatis, but most were not and they were forced to remain stationary, firing behind trees and rocks. When General Logan rode forward to judge their progress, he determined that many of his men were being "uselessly slain" and ordered Walcutt and Smith to withdraw and entrench behind the gorge that separated the lines.

About to the south, Thomas's troops were behind schedule, but began their main attack against Hardee's corps at 9 a.m. Two divisions of the Army of the Cumberland—about 9,000 men under Brig. Gen. John Newton

John Newton (; – 21 December 1807) was an English evangelical Anglican cleric and slavery abolitionist. He had previously been a captain of slave ships and an investor in the slave trade. He served as a sailor in the Royal Navy (after forc ...

(Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard

Oliver Otis Howard (November 8, 1830 – October 26, 1909) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the Civil War. As a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac, Howard lost his right arm while leading his men against ...

's IV Corps) and Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis (Maj. Gen. John M. Palmer's XIV Corps)—advanced in column formation rather than the typical broad line of battle against the Confederate divisions of Maj. Gens. Benjamin F. Cheatham and Patrick R. Cleburne

Major general, Major-General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne ( ; March 16, 1828November 30, 1864) was a senior Officer (armed forces), officer of the Confederate States Army who commanded infantry in the Western Theater of the American Civil War, West ...

, entrenched on what is now known as "Cheatham Hill." On Newton's left, his brigade under Brig. Gen. George D. Wagner attacked through dense undergrowth, but was unable to break through the abatis and fierce rifle fire. On his right, the brigade of Brig. Gen. Charles G. Harker charged the Tennessee brigade of Brig. Gen. Alfred Vaughan and was repulsed. During a second charge, Harker was mortally wounded.

Davis's division, to the right of Newton's, also advanced in column formation. While such a movement offered the opportunity for a quick breakthrough by massing power against a narrow point, it also had the disadvantage of offering a large concentrated target to enemy guns. Their orders were to advance silently, capture the works, and then cheer to give a signal to the reserve divisions to move forward to secure the railroad and cut the Confederate army in two. Col. Daniel McCook

Daniel McCook (June 20, 1798 – July 21, 1863) was an attorney and an officer in the Union army during the American Civil War. He was one of two Ohio brothers who, along with 13 of their sons, became widely known as the “ Fighting McC ...

's brigade advanced down a slope to a creek and then crossed a wheat field to ascend the slope of Cheatham Hill. When they reached within a few yards of the Confederate works, the line halted, crouched, and began firing. But the Confederate counter fire was too strong and McCook's brigade lost two commanders (McCook and his replacement, Col. Oscar F. Harmon), nearly all of its field officers, and a third of its men. McCook was killed on the Confederate parapet as he slashed with his sword and shouted "Surrender, you traitors!" Col. John G. Mitchell's brigade on McCook's right suffered similar losses. After ferocious hand-to-hand fighting, the Union troops dug in across from the Confederates, ending the fighting around 10:45 a.m. Both sides nicknamed this place the "Dead Angle."

To the right of Davis's division, Maj. Gen. John W. Geary

John White Geary (December 30, 1819February 8, 1873) was an American lawyer, politician, Freemason, and a Union general in the American Civil War. He was the final alcalde and first mayor of San Francisco, a governor of the Kansas Territory, and ...

's division of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker

Joseph Hooker (November 13, 1814 – October 31, 1879) was an American Civil War general for the Union, chiefly remembered for his decisive defeat by Confederate General Robert E. Lee at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863.

Hooker had serv ...

's XX Corps advanced, but did not join in Davis's attack. Considerably farther to the right, however, was the site of the only success of the day. Schofield's army had been assigned to demonstrate against the Confederate left and he was able to put two brigades across Olley's Creek without resistance. That movement, along with an advance by Maj. Gen. George Stoneman's cavalry division on Schofield's right, put Union troops within of the Chattahoochee River

The Chattahoochee River forms the southern half of the Alabama and Georgia border, as well as a portion of the Florida - Georgia border. It is a tributary of the Apalachicola River, a relatively short river formed by the confluence of the Chatta ...

, closer to the last river protecting Atlanta than any unit in Johnston's army.

Aftermath

Sherman's armies suffered about 3,000 casualties in comparison to Johnston's 1,000. The Union general was not initially deterred by these losses and he twice asked Thomas to renew the assault. "Our loss is small, compared to some of those

Sherman's armies suffered about 3,000 casualties in comparison to Johnston's 1,000. The Union general was not initially deterred by these losses and he twice asked Thomas to renew the assault. "Our loss is small, compared to some of those attles in the Attles is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Al Attles (born 1936), American basketball player and coach

*Joseph Attles

Joseph Attles (April 7, 1903 – October 29, 1990) was an American character actor of the legitimate thea ...

East." The Rock of Chickamauga replied, however, "One or two more such assaults would use up this army." A few days later Sherman coldly wrote to his wife, "I begin to regard the death and mangling of couple thousand men as a small affair, a kind of morning dash."

Kennesaw Mountain was not Sherman's first large-scale frontal assault of the war, but it was his last. He interrupted his string of successful flanking maneuvers in the Atlanta campaign for the logistical reasons mentioned earlier, but also so that he could keep Johnston guessing about the tactics he would employ in the future. In his report of the battle, Sherman wrote, "I perceived that the enemy and our officers had settled down into a conviction that I would not assault fortified lines. All looked to me to outflank. An army to be efficient, must not settle down to a single mode of offence, but must be prepared to execute any plan which promises success. I wanted, therefore, for the moral effect, to make a successful assault against the enemy behind his breastworks, and resolved to attempt it at that point where success would give the largest fruits of victory."

Kennesaw Mountain is usually considered a significant Union tactical defeat, but Richard M. McMurry wrote, "Tactically Johnston had won a minor defensive triumph on Loring's and Hardee's lines. Schofield's success, however, gave Sherman a great advantage, and the federal commander quickly decided to exploit it." The opposing forces spent five days facing each other at close range, but on July 2, with good summer weather at hand, Sherman sent the Army of the Tennessee and Stoneman's cavalry around the Confederate left flank and Johnston was forced to withdraw from Kennesaw Mountain to prepared positions at Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

.

On July 8, Sherman outflanked Johnston again—for the first time on his right—by sending Schofield to cross the Chattahoochee near the mouth of Sope Creek. The last major geographic barrier to entering Atlanta had been overcome. Alarmed at the imminent danger posed to the city of Atlanta, and frustrated with the strategy of continual withdrawals, Confederate President Jefferson Davis relieved Johnston of command on July 17, replacing him with the aggressive John Bell Hood

John Bell Hood (June 1 or June 29, 1831 – August 30, 1879) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Although brave, Hood's impetuosity led to high losses among his troops as he moved up in rank. Bruce Catton wrote that "the de ...

, who was temporarily promoted to full general. Hood proceeded to attack Sherman in battles at Peachtree Creek (July 20), Atlanta/Decatur (July 22), and Ezra Church (July 28), in all of which he suffered enormous casualties without tactical advantage. Sherman besieged Atlanta for the month of August, but sent almost his entire force swinging to the south to cut off the city's last remaining railroad connection. In the Battle of Jonesboro (August 31 and September 1), Hood attacked again to save his railroad, but was unsuccessful and was forced to evacuate Atlanta. Sherman's men entered the city on September 2 and Sherman telegraphed President Lincoln, "Atlanta is ours, and fairly won." This milestone

A milestone is a numbered marker placed on a route such as a road, railway, railway line, canal or border, boundary. They can indicate the distance to towns, cities, and other places or landmarks; or they can give their position on the rou ...

was arguably one of the key factors enabling Lincoln's reelection in November.

A soldier's perspective

The battle is described from the perspective of Sam Watkins, a volunteer in the 1st Tennessee Infantry Regiment of the Confederate Army, in the book "Company Aytch" (see the section entitled "Dead Angle, on the Kennesaw Line").Battlefield today

The site of the battle is now part of Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park, where both Confederate deliberate trenches on top of the mountain and some Union rifle pits are still visible today. TheCivil War Trust

The American Battlefield Trust is a charitable organization ( 501(c)(3)) whose primary focus is in the preservation of battlefields of the American Civil War, the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 through acquisition of battlefield land. Th ...

, a division of the American Battlefield Trust

The American Battlefield Trust is a charitable organization (501(c)#501(c)(3), 501(c)(3)) whose primary focus is in the preservation of battlefields of the American Civil War, the American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 ...

, and its partners have saved four acres at the battlefield through mid-2018.American Battlefield Trust

The American Battlefield Trust is a charitable organization (501(c)#501(c)(3), 501(c)(3)) whose primary focus is in the preservation of battlefields of the American Civil War, the American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 ...

"Saved Land" webpage. Accessed May 18, 2018.Notes

References

* Bailey, Ronald H., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. ''Battles for Atlanta: Sherman Moves East''. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. . * Castel, Albert. ''Decision in the West: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864''. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1992. . * David J. Eicher, Eicher, David J. ''The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. . * Kennedy, Frances H., ed''The Civil War Battlefield Guide''

2nd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998. . * Liddell Hart, B. H. ''Sherman: Soldier, Realist, American''. New York: Da Capo Press, 1993. . First published in 1929 by Dodd, Mead & Co. * Livermore, Thomas L. ''Numbers and Losses in the Civil War in America 1861–65''. Reprinted with errata, Dayton, OH: Morninside House, 1986. . First published 1901 by Houghton Mifflin. * Luvaas, Jay, and Harold W. Nelson, eds. ''Guide to the Atlanta Campaign: Rocky Face Ridge to Kennesaw Mountain''. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2008. . * McDonough, James Lee, and James Pickett Jones. ''War So Terrible: Sherman and Atlanta''. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1987, . * McMurry, Richard M. ''Atlanta 1864: Last Chance for the Confederacy''. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000. . * McPherson, James M. '' Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era''. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. . * Welcher, Frank J. ''The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations''. Vol. 2, ''The Western Theater''. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993. .

National Park Service battle description

Further reading

* Hess, Earl J. ''Kennesaw Mountain: Sherman, Johnston, and the Atlanta Campaign''. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. . * * Vermilya, Daniel J. ''The Battle of Kennesaw Mountain''. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2014. .External links

Battle maps, history articles, and preservation news (

Civil War Trust

The American Battlefield Trust is a charitable organization ( 501(c)(3)) whose primary focus is in the preservation of battlefields of the American Civil War, the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 through acquisition of battlefield land. Th ...

)

{{authority control

Kennesaw Mountain

Kennesaw Mountain

Kennesaw Mountain

Kennesaw Mountain

Kennesaw Mountain

1864 in Georgia (U.S. state)

June 1864 events