Battle Of Kehl (1796) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

During the Battle of Kehl (23–24 June 1796), a Republican French force under the direction of Jean Charles Abbatucci mounted an amphibious crossing of the

pp. 17–20

The considerable number of territories in the Empire included more than 1,000 entities. Their size and influence varied, from the ''

Everything went according to the French plan, at least for the first six weeks. On 4 June 1796, 11,000 soldiers of the Army of the Sambre-et-Meuse, commanded by

Everything went according to the French plan, at least for the first six weeks. On 4 June 1796, 11,000 soldiers of the Army of the Sambre-et-Meuse, commanded by

''The History of the Campaign of 1796 in Germany and Italy.''

London, 1797. . * Hansard, Thomas C (ed.). ''Hansard's Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, 1803'', Official Report. Vol. 1. London: HMSO, 1803, pp. 249–252 * Haythornthwaite, Philip. ''Austrian Army of the Napoleonic Wars (1): Infantry.'' Oxford, Osprey Publishing, 2012. * Knepper, Thomas P. ''The Rhine.'' Handbook for Environmental Chemistry Series, Part L. New York: Springer, 2006, . * Nafziger, George

''French Troops Destined to Cross the Rhine, 24 June 1796''

US Army Combined Arms Center. Accessed 2 October 2014. * Philippart, John

''Memoires etc. of General Moreau''

London, A.J. Valpy, 1814. * Phipps, Ramsay Weston ''The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume II The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle.'' USA, Pickle Partners Publishing, 2011 923–1933 * Rickard, J

''Combat of Uckerath, 19 June 1796''History of War

Feb 2009 version, accessed 1 March 2015. * Rothenberg, Gunther E. "The Habsburg Army in the Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815)." ''Military Affairs'', 37:1 (Feb 1973), 1–5. * Smith, Digby. ''The Napoleonic Wars Data Book''. London, Greenhill, 1998. * Vann, James Allen. ''The Swabian Kreis: Institutional Growth in the Holy Roman Empire 1648–1715.'' Vol. LII, Studies Presented to International Commission for the History of Representative and Parliamentary Institutions. Bruxelles, 1975. * Volk, Helmut

"Landschaftsgeschichte und Natürlichkeit der Baumarten in der Rheinaue."

''Waldschutzgebiete Baden-Württemberg'', Band 10, pp. 159–167. * Walker, Mack. ''German Home Towns: Community, State, and General Estate, 1648–1871.'' Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1998. * Whaley, Joachim. ''Germany and the Holy Roman Empire: Volume I: Maximilian I to the Peace of Westphalia, 1493–1648''. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2012. * Wilson, Peter Hamish. ''German Armies: War and German Politics 1648–1806.'' London, UCL Press, 1997. . {{DEFAULTSORT:Kehl 1796, Battle of

Rhine

The Rhine ; french: Rhin ; nl, Rijn ; wa, Rén ; li, Rien; rm, label=Sursilvan, Rein, rm, label=Sutsilvan and Surmiran, Ragn, rm, label=Rumantsch Grischun, Vallader and Puter, Rain; it, Reno ; gsw, Rhi(n), including in Alsatian dialect, Al ...

River against a defending force of soldiers from the Swabian Circle

The Circle of Swabia or Swabian Circle (german: Schwäbischer Reichskreis or ''Schwäbischer Kreis'') was an Imperial Circle of the Holy Roman Empire established in 1500 on the territory of the former German stem-duchy of Swabia. However, it d ...

. In this action of the War of the First Coalition

The War of the First Coalition (french: Guerre de la Première Coalition) was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797 initially against the constitutional Kingdom of France and then the French Republic that succ ...

, the French drove the Swabians from their positions in Kehl

Kehl (; gsw, label= Low Alemannic, Kaal) is a town in southwestern Germany in the Ortenaukreis, Baden-Württemberg. It is on the river Rhine, directly opposite the French city of Strasbourg, with which it shares some municipal servicesfor exa ...

and subsequently controlled the bridgehead on both sides of the Rhine.

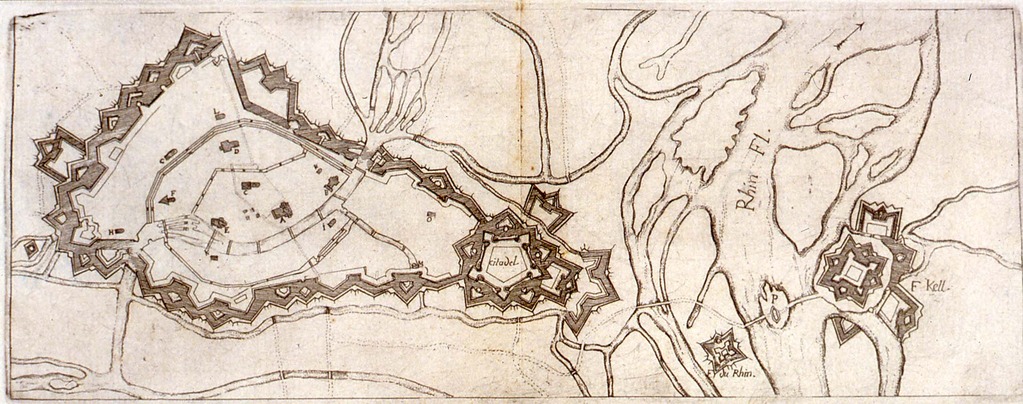

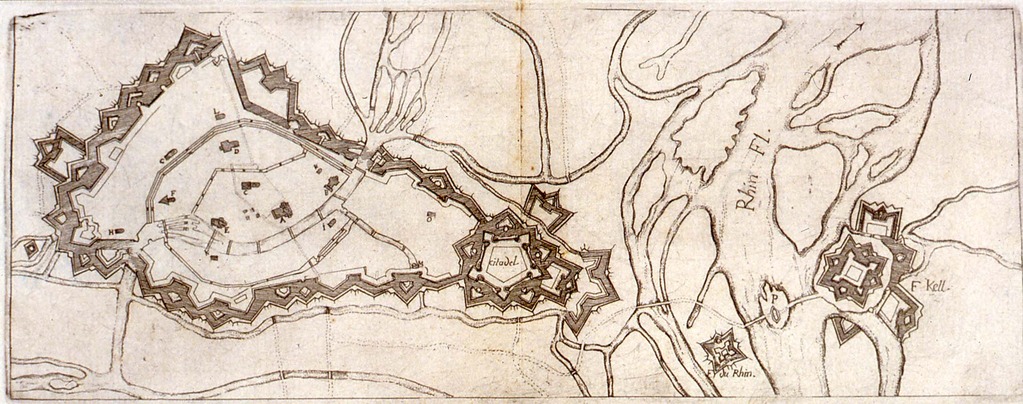

Although separated politically and geographically, the fates of Kehl, a village on the eastern shore of the Rhine in Baden-Durlach

The Margraviate of Baden-Durlach was an early modern territory of the Holy Roman Empire, in the upper Rhine valley, which existed from 1535 to 1771. It was formed when the Margraviate of Baden was split between the sons of Margrave Christopher ...

, and those of the Alsatian city of Strasbourg, on the western shore, were united by the presence of bridges and a series of gates, fortifications and barrage dam

A barrage is a type of low-head, diversion dam which consists of a number of large gates that can be opened or closed to control the amount of water passing through. This allows the structure to regulate and stabilize river water elevation up ...

s that allowed passage across the river. In the 1790s, the Rhine was wild, unpredictable, and difficult to cross, in some places more than four or more times wider than it is in the twenty-first century, even under non-flood conditions. Its channels and tributaries wound through marsh and meadow and created islands of trees and vegetation that were alternately submerged by floods or exposed during the dry seasons.

The fortifications at Kehl and Strasbourg had been constructed by the fortress architect Sébastien le Préstre de Vauban in the seventeenth century. The crossings had been contested before: in 1678 during the French-Dutch war, in 1703

In the Swedish calendar it was a common year starting on Thursday, one day ahead of the Julian and ten days behind the Gregorian calendar.

Events

January–March

* January 9 – The Jamaican town of Port Royal, a center of trade ...

during the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phili ...

and in 1733

Events

January–March

* January 13 – Borommarachathirat V becomes King of Siam (now Thailand) upon the death of King Sanphet IX.

* January 27 – George Frideric Handel's classic opera, ''Orlando'' is performed for the ...

during the War of the Polish Succession

The War of the Polish Succession ( pl, Wojna o sukcesję polską; 1733–35) was a major European conflict sparked by a Polish civil war over the succession to Augustus II of Poland, which the other European powers widened in pursuit of their ...

. Critical to success of the French plan would be the army's ability to cross the Rhine at will. Consequently, control of the crossings at Hüningen, near the Swiss city of Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS) ...

, and at Kehl, would give them ready access to most of southwestern Germany; from there, French armies could sweep north, south, or east, depending on their military goal.

Background

The Rhine Campaign of 1795 (April 1795 to January 1796) opened when two Habsburg Austrian armies under the overall command ofFrançois Sébastien Charles Joseph de Croix, Count of Clerfayt

François Sébastien Charles Joseph de Croix, Count of Clerfayt (14 October 1733 – 21 July 1798),His title is also spelled Count of Clairfayt and Count of Clairfait a Walloon, joined the army of the Habsburg monarchy and soon fought in the Seve ...

defeated an attempt by two Republican French armies to cross the Rhine River and capture the Fortress of Mainz

The Fortress of Mainz was a fortressed garrison town between 1620 and 1918. At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, under the term of the 1815 Peace of Paris, the control of Mainz passed to the German Confederation and became part of a chain of str ...

. At the start of the campaign the French Army of the Sambre and Meuse led by Jean-Baptiste Jourdan

Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, 1st Count Jourdan (29 April 1762 – 23 November 1833), was a French military commander who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. He was made a Marshal of the Empire by Emperor Napoleon I in ...

confronted Clerfayt's Army of the Lower Rhine in the north, while the French Army of Rhine and Moselle under Pichegru lay opposite Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser

Dagobert Sigismund, Count von Wurmser (7 May 1724 – 22 August 1797) was an Austrian field marshal during the French Revolutionary Wars. Although he fought in the Seven Years' War, the War of the Bavarian Succession, and mounted several successf ...

's army in the south. In August, Jourdan crossed and quickly seized Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in ...

. The Army of the Sambre and Meuse advanced south to the Main River

Main rivers () are a statutory type of watercourse in England and Wales, usually larger streams and rivers, but also some smaller watercourses. A main river is designated by being marked as such on a main river map, and can include any structure o ...

, completely isolating Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

. Pichegru's army made a surprise capture of Mannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (german: Universitätsstadt Mannheim), is the second-largest city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg after the state capital of Stuttgart, and Germany's ...

so that both French armies held significant footholds on the east bank of the Rhine. The French fumbled away the promising start to their offensive. Pichegru bungled at least one opportunity to seize Clerfayt's supply base in the Battle of Handschuhsheim

The Battle of Handschuhsheim or Battle of Heidelberg (24 September 1795) saw an 8,000-man force from Habsburg Austria under Peter Vitus von Quosdanovich face 12,000 men from the Republican French army led by Georges Joseph Dufour. Thanks to a d ...

. With Pichegru unexpectedly inactive, Clerfayt massed against Jourdan, beat him at Höchst in October and forced most of the Army of the Sambre and Meuse to retreat to the west bank of the Rhine. About the same time, Wurmser sealed off the French bridgehead at Mannheim. With Jourdan temporarily out of the picture, the Austrians defeated the left wing of the Army of Rhine and Moselle at the Battle of Mainz

The Battle of Mainz (29 October 1795) saw a Habsburg monarchy, Habsburg army led by François Sebastien Charles Joseph de Croix, Count of Clerfayt launch a surprise assault against four divisions of the French ''Army of Rhin-et-Moselle'' direc ...

and moved down the west bank. In November, Clerfayt gave Pichegru a drubbing at Pfeddersheim and successfully wrapped up the siege of Mannheim. In January 1796, Clerfayt concluded an armistice with the French, allowing the Austrians to retain large portions of the west bank. During the campaign Pichegru had entered into negotiations with French Royalists. It is debatable whether Pichegru's treason or bad generalship was the actual cause of the French failure.Theodore Ayrault Dodge

Theodore Ayrault Dodge (May 28, 1842 – October 26, 1909) was an American officer, military historian, and businessman. He fought as a Union officer in the American Civil War; as a writer, he was devoted to both the Civil War and the great gener ...

, ''Warfare in the Age of Napoleon: The Revolutionary Wars Against the First Coalition in Northern Europe and the Italian Campaign, 1789–1797.'' Leonaur Ltd, 2011. pp. 286–287. See also Timothy Blanning, ''The French Revolutionary Wars,'' New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, , pp. 41–59. which lasted until 20 May 1796, when the Austrians announced that it would end on 31 May. This set the stage for continued action during the campaign months of May through October 1796.

Terrain

The Rhine River flows west along the border between the German states and theSwiss Cantons

The 26 cantons of Switzerland (german: Kanton; french: canton ; it, cantone; Sursilvan and Surmiran: ; Vallader and Puter: ; Sutsilvan: ; Rumantsch Grischun: ) are the member states of the Swiss Confederation. The nucleus of the Swiss C ...

. The stretch between Rheinfall, by Schaffhausen

Schaffhausen (; gsw, Schafuuse; french: Schaffhouse; it, Sciaffusa; rm, Schaffusa; en, Shaffhouse) is a town with historic roots, a municipality in northern Switzerland, and the capital of the canton of the same name; it has an estimat ...

and Basel, the High Rhine

The High Rhine (german: Hochrhein) is the name used for the part of the Rhine that flows westbound from Lake Constance to Basel. The High Rhine begins at the outflow of the Rhine from the Untersee in Stein am Rhein and turns into the Upper Rhine ...

cuts through steep hillsides over a gravel bed; in such places as the former rapids at Laufenburg, it moved in torrents. A few miles north and east of Basel, the terrain flattens. The Rhine makes a wide, northerly turn, in what is called the Rhine knee, and enters the so-called Rhine ditch (''Rheingraben''), part of a rift valley

A rift valley is a linear shaped lowland between several highlands or mountain ranges created by the action of a geologic rift. Rifts are formed as a result of the pulling apart of the lithosphere due to extensional tectonics. The linear de ...

bordered by the Black Forest

The Black Forest (german: Schwarzwald ) is a large forested mountain range in the state of Baden-Württemberg in southwest Germany, bounded by the Rhine Valley to the west and south and close to the borders with France and Switzerland. It is ...

on the east and Vosges Mountains

The Vosges ( , ; german: Vogesen ; Franconian and gsw, Vogese) are a range of low mountains in Eastern France, near its border with Germany. Together with the Palatine Forest to the north on the German side of the border, they form a single ...

on the west. In 1796, the plain on both sides of the river, some wide, was dotted with villages and farms. At both far edges of the flood plain, especially on the eastern side, the old mountains created dark shadows on the horizon. Tributaries cut through the hilly terrain of the Black Forest, creating deep defiles in the mountains. The tributaries then wind in rivulets through the flood plain to the river.

The Rhine River itself looked different in the 1790s than it does in the twenty-first century; the passage from Basel to Iffezheim was "corrected" (straightened) between 1817 and 1875. Between 1927 and 1975, a canal was constructed to control the water level. In the 1790s, the river was wild and unpredictable, in some places four or more times wider than the twenty-first century incarnation of the river, even under regular conditions. Its channels wound through marsh and meadow, and created islands of trees and vegetation that were periodically submerged by floods. It was crossable at Kehl, by Strasbourg, and Hüningen, by Basel, where systems of viaducts

A viaduct is a specific type of bridge that consists of a series of arches, piers or columns supporting a long elevated railway or road. Typically a viaduct connects two points of roughly equal elevation, allowing direct overpass across a wide va ...

and causeways

A causeway is a track, road or railway on the upper point of an embankment across "a low, or wet place, or piece of water". It can be constructed of earth, masonry, wood, or concrete. One of the earliest known wooden causeways is the Sweet ...

made access reliable.

Political complications

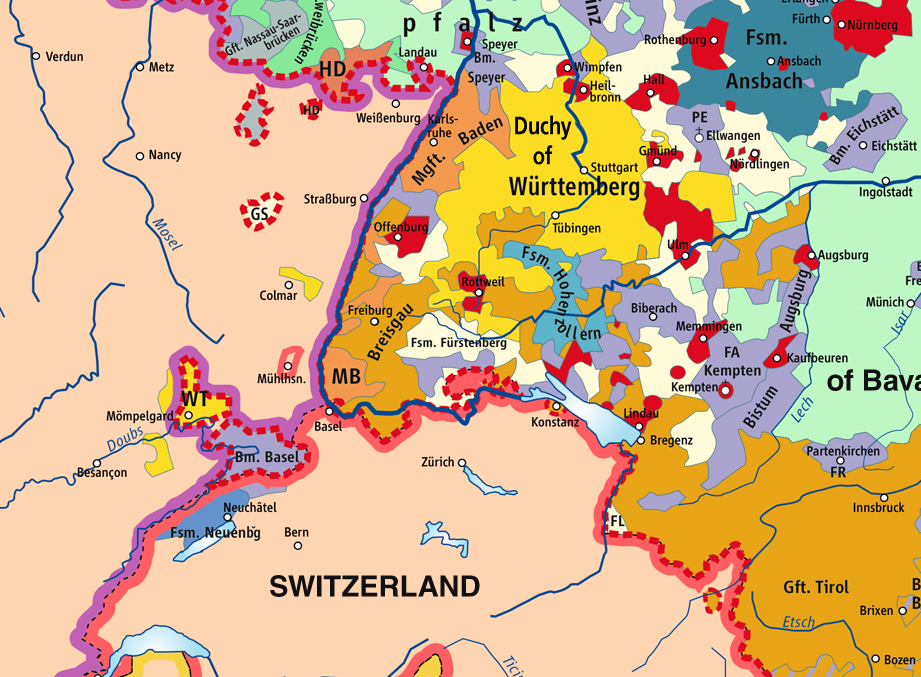

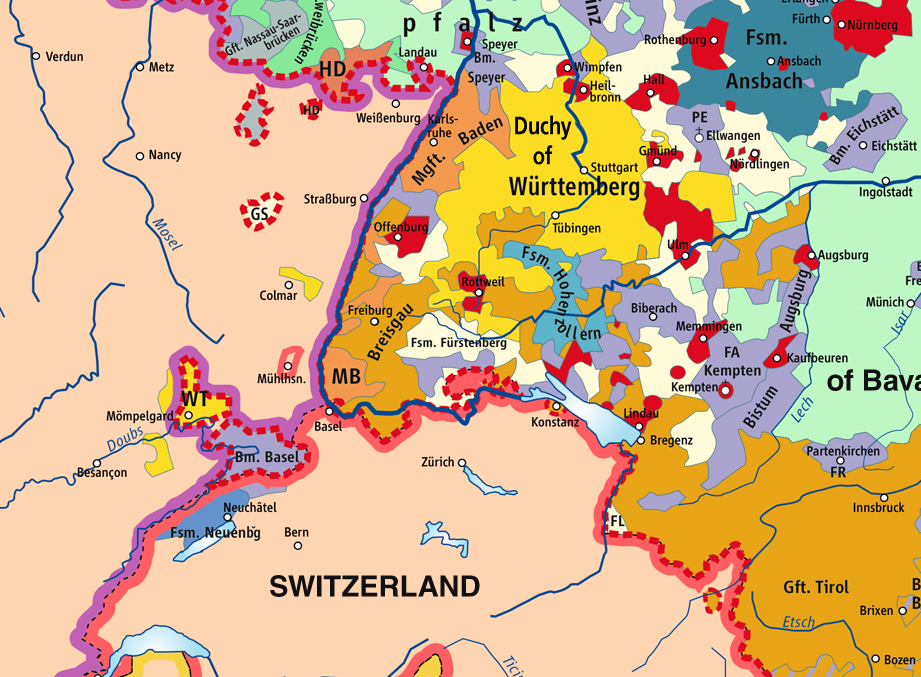

The German-speaking states on the east bank of the Rhine were part of the vast complex of territories incentral Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the ...

called the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

.Joachim Whaley, ''Germany and the Holy Roman Empire: Volume I: Maximilian I to the Peace of Westphalia, 1493–1648 ''(2012)pp. 17–20

The considerable number of territories in the Empire included more than 1,000 entities. Their size and influence varied, from the ''

Kleinstaaterei

In the history of Germany, (, ''"small-state -ery"'') is a German word used, often pejoratively, to denote the territorial fragmentation during the Holy Roman Empire (especially after the end of the Thirty Years' War), and during the ...

'', the little states that covered no more than a few square miles, or included several non-contiguous pieces, to the small and complex territories of the princely Hohenlohe

The House of Hohenlohe () is a German princely dynasty. It ruled an immediate territory within the Holy Roman Empire which was divided between several branches. The Hohenlohes became imperial counts in 1450. The county was divided numerous ti ...

family branches, to such sizable, well-defined territories as the Kingdoms of Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

and Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

. The governance of these many states varied: they included the autonomous free imperial cities

In the Holy Roman Empire, the collective term free and imperial cities (german: Freie und Reichsstädte), briefly worded free imperial city (', la, urbs imperialis libera), was used from the fifteenth century to denote a self-ruling city that ...

, also of different sizes and influence, from the powerful Augsburg

Augsburg (; bar , Augschburg , links=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swabian_German , label=Swabian German, , ) is a city in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, around west of Bavarian capital Munich. It is a university town and regional seat of the '' ...

to the minuscule Weil der Stadt

Weil der Stadt is a town of about 19,000 inhabitants in the Stuttgart Region of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is about west of Stuttgart city centre, in the valley of the River Würm, and is often called the "Gate to the Black For ...

; ecclesiastical territories, also of varying sizes and influence, such as the wealthy Abbey of Reichenau

Reichenau Abbey was a Benedictine monastery on Reichenau Island (known in Latin as Augia Dives). It was founded in 724 by the itinerant Saint Pirmin, who is said to have fled Spain ahead of the Moorish invaders, with patronage that included Char ...

and the powerful Archbishopric of Cologne

The Archdiocese of Cologne ( la, Archidioecesis Coloniensis; german: Erzbistum Köln) is an archdiocese of the Catholic Church in western North Rhine-Westphalia and northern Rhineland-Palatinate in Germany.

History

The Electorate of Colog ...

; and dynastic states such as Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Hohenzollern, two other historical territories, Wür ...

. When viewed on a map, the Empire resembled a " patchwork carpet". Both the Habsburg domains and Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brandenb ...

Prussia also included territories outside the Empire. There were also territories completely surrounded by France that belonged to Württemberg, the Archbishopric of Trier

Trier ( , ; lb, Tréier ), formerly known in English as Trèves ( ;) and Triers (see also names in other languages), is a city on the banks of the Moselle in Germany. It lies in a valley between low vine-covered hills of red sandstone in the ...

, and Hesse-Darmstadt

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt (german: Landgrafschaft Hessen-Darmstadt) was a State of the Holy Roman Empire, ruled by a younger branch of the House of Hesse. It was formed in 1567 following the division of the Landgraviate of Hesse betwee ...

. Among the German-speaking states, the Holy Roman Empire's administrative and legal mechanisms provided a venue to resolve disputes between peasants and landlords, between jurisdictions, and within jurisdictions. Through the organization of imperial circles, also called ''Reichskreise'', groups of states consolidated resources and promoted regional and organizational interests, including economic cooperation and military protection.

Disposition

The armies of theFirst Coalition

The War of the First Coalition (french: Guerre de la Première Coalition) was a set of wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797 initially against the constitutional Kingdom of France and then the French Republic that suc ...

included the contingents and the infantry and cavalry of the various states, amounted to about 125,000 troops (including the three autonomous corps), a sizable force by eighteenth century standards but a moderate force by the standards of the Revolutionary wars. Archduke Charles

Archduke Charles Louis John Joseph Laurentius of Austria, Duke of Teschen (german: link=no, Erzherzog Karl Ludwig Johann Josef Lorenz von Österreich, Herzog von Teschen; 5 September 177130 April 1847) was an Austrian field-marshal, the third s ...

, Duke of Teschen and brother of the Holy Roman Emperor, served as commander-in-chief. In total, Charles’ troops stretched in a line from Switzerland to the North Sea. Habsburg troops comprised the bulk of the army but the thin white line of Habsburg infantry could not cover the territory from Basel to Frankfurt with sufficient depth to resist the pressure of the opposition. Compared to French coverage, Charles had half the number of troops covering a 211-mile front, stretching from Renchen

Renchen ( gsw, label=Low Alemannic, Renche) is a small town in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, part of the district of Ortenau.

Geography

Renchen is located in the foothills of the northern Black Forest at the entrance to the Rench valley at the ...

, near Basel to Bingen. Furthermore, he had concentrated the bulk of his force, commanded by Count Baillet Latour, between Karlsruhe and Darmstadt, where the confluence of the Rhine and the Main

Main may refer to:

Geography

*Main River (disambiguation)

**Most commonly the Main (river) in Germany

* Main, Iran, a village in Fars Province

*"Spanish Main", the Caribbean coasts of mainland Spanish territories in the 16th and 17th centuries

* ...

made an attack most likely, as it offered a gateway into eastern German states and ultimately to Vienna, with good bridges crossing a relatively well-defined river bank. To the north, Wilhelm von Wartensleben’s autonomous corps stretched in a thin line between Mainz and Giessen.

In spring 1796, drafts from the free imperial cities, and other imperial estate

An Imperial State or Imperial Estate ( la, Status Imperii; german: Reichsstand, plural: ') was a part of the Holy Roman Empire with representation and the right to vote in the Imperial Diet ('). Rulers of these Estates were able to exercise si ...

s in the Swabian and Franconian Circles augmented the Habsburg force with perhaps 20,000 men at the most. The militias, most of which were Swabian field hands and day laborers drafted for service in the spring of that year, were untrained and unseasoned. As he gathered his army in March and April, it was largely guess work where they should be placed. In particular, Charles did not like to use the militias in any vital location. Consequently, in May and early June, when the French started to mass troops by Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

and it looked as if the bulk of the French army would cross there—they even engaged the imperial force at Altenkirchen (4 June) and Wetzler and Uckerath (15 June)—Charles felt few qualms placing the 7000-man Swabian militia at the crossing by Kehl.Smith, p. 114.

French plans

An assault into the German states was essential, as far as French commanders understood, not only in terms of war aims, but also in practical terms: theFrench Directory

The Directory (also called Directorate, ) was the governing five-member committee in the French First Republic from 2 November 1795 until 9 November 1799, when it was overthrown by Napoleon Bonaparte in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and replaced ...

believed that war should pay for itself, and did not budget for the feeding of its troops. The French citizen’s army, created by mass conscription of young men and systematically divested of old men who might have tempered the rash impulses of teenagers and young adults, had already made itself unwelcome throughout France. It was an army entirely dependent for support upon the countryside it occupied for provisions and wages. Until 1796, wages were paid in the worthless ''assignat

An assignat () was a monetary instrument, an order to pay, used during the time of the French Revolution, and the French Revolutionary Wars.

France

Assignats were paper money (fiat currency) issued by the Constituent Assembly in France from 1 ...

'' (France's paper currency); after April 1796, although pay was made in metallic value, wages were still in arrears. Throughout that spring and early summer, the French army was in almost constant mutiny: in May 1796, in the border town of Zweibrücken

Zweibrücken (; french: Deux-Ponts, ; Palatinate German: ''Zweebrigge'', ; literally translated as "Two Bridges") is a town in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, on the Schwarzbach river.

Name

The name ''Zweibrücken'' means 'two bridges'; olde ...

, the 74th Demi-brigade revolted. In June, the 17th Demi-brigade was insubordinate (frequently) and in the 84th Demi-brigade, two companies rebelled.

The French faced a formidable obstacle in addition to the Rhine. The Coalition's Army of the Lower Rhine counted 90,000 troops. The 20,000-man right wing under Duke Ferdinand Frederick Augustus of Württemberg

Duke Ferdinand Frederick Augustus of Württemberg (22 October 1763 – 20 January 1834) was a Habsburg Austrian general during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars.

Early life

He was born into the House of Württemberg as the f ...

stood on the east bank of the Rhine behind the Sieg

The Sieg is a river in North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It is a right tributary of the Rhine.

The river is named after the Sicambri. It is in length.

The source is located in the Rothaargebirge mountains. From here t ...

River, observing the French bridgehead at Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in ...

. The garrisons of Mainz Fortress and Ehrenbreitstein Fortress

Ehrenbreitstein Fortress (german: Festung Ehrenbreitstein, ) is a fortress in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate, on the east bank of the Rhine where it is joined by the Moselle, overlooking the town of Koblenz.

Occupying the position of an ...

included 10,000 more. The remainder held the west bank behind the Nahe River. Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser

Dagobert Sigismund, Count von Wurmser (7 May 1724 – 22 August 1797) was an Austrian field marshal during the French Revolutionary Wars. Although he fought in the Seven Years' War, the War of the Bavarian Succession, and mounted several successf ...

, who initially commanded the whole operation, led the 80,000-strong Army of the Upper Rhine. Its right wing occupied Kaiserslautern

Kaiserslautern (; Palatinate German: ''Lautre'') is a city in southwest Germany, located in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate at the edge of the Palatinate Forest. The historic centre dates to the 9th century. It is from Paris, from Frankfu ...

on the west bank while the left wing under Anton Sztáray

Anton Sztáray de Nagy-Mihály ( hu, Nagymihályi Sztáray Antal, 1732 or 1740, Kassa, Hungary – 23 January 1808, Graz, Austrian Empire) was a Hungarian count in the Habsburg military during Austria's Wars with the Ottoman Empire, the French Re ...

, Michael von Fröhlich

Michael, Freiherr von Fröhlich (9 January 1740 – 1814) was a German general officer serving in army of the Austrian Empire, notably during the Wars of the French Revolution.

Service

Fröhlich was born in Marburg in Hesse, Germany, and by ...

and Louis Joseph, Prince of Condé

Louis Joseph de Bourbon (9 August 1736 – 13 May 1818) was Prince of Condé from 1740 to his death. A member of the House of Bourbon, he held the prestigious rank of '' Prince du Sang''.

Youth

Born on 9 August 1736 at Chantilly, Louis J ...

guarded the Rhine from Mannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (german: Universitätsstadt Mannheim), is the second-largest city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg after the state capital of Stuttgart, and Germany's ...

to Switzerland. The original Austrian strategy was to capture Trier

Trier ( , ; lb, Tréier ), formerly known in English as Trèves ( ;) and Triers (see also names in other languages), is a city on the banks of the Moselle in Germany. It lies in a valley between low vine-covered hills of red sandstone in the ...

and to use their position on the Rhine's west bank to strike at each of the French armies in turn. However, after news arrived in Vienna of Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

's successes in northern Italy, Wurmser was sent to Italy with 25,000 reinforcements; the Aulic Council

The Aulic Council ( la, Consilium Aulicum, german: Reichshofrat, literally meaning Court Council of the Empire) was one of the two supreme courts of the Holy Roman Empire, the other being the Imperial Chamber Court. It had not only concurrent juri ...

gave Archduke Charles command over both Austrian armies and ordered him to hold his ground.

On the French side, the 80,000-man Army of Sambre-et-Meuse held the west bank of the Rhine down to the Nahe and then southwest to Sankt Wendel

Sankt Wendel is a town in northeastern Saarland. It is situated on the river Blies 36 km northeast of Saarbrücken, the capital of Saarland, and is named after Saint Wendelin of Trier. According to a survey by the German Association for Ho ...

. On this army's left flank, Jean Baptiste Kléber

Jean may refer to:

People

* Jean (female given name)

* Jean (male given name)

* Jean (surname)

Fictional characters

* Jean Grey, a Marvel Comics character

* Jean Valjean, fictional character in novel ''Les Misérables'' and its adaptations

* ...

had 22,000 troops entrenched at Düsseldorf. The right wing of the Army of the Rhine and Moselle

The Army of the Rhine and Moselle (french: Armée de Rhin-et-Moselle) was one of the field units of the French Revolutionary Army. It was formed on 20 April 1795 by the merger of elements of the Army of the Rhine and the Army of the Moselle.

Th ...

, under Jean Victor Moreau's command, was positioned east of the Rhine from Hüningen (on the border with the French provinces, Switzerland, and the German states) northward, with its center along the Queich

The Queich is a tributary of the Rhine, which rises in the southern part of the Palatinate Forest, and flows through the Upper Rhine valley to its confluence with the Rhine in Germersheim. It is long and is one of the four major drainage syste ...

River near Landau

Landau ( pfl, Landach), officially Landau in der Pfalz, is an autonomous (''kreisfrei'') town surrounded by the Südliche Weinstraße ("Southern Wine Route") district of southern Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It is a university town (since 1990 ...

and its left wing extended west toward Saarbrücken

Saarbrücken (; french: link=no, Sarrebruck ; Rhine Franconian: ''Saarbrigge'' ; lb, Saarbrécken ; lat, Saravipons, lit=The Bridge(s) across the Saar river) is the capital and largest city of the state of Saarland, Germany. Saarbrücken is ...

. Pierre Marie Barthélemy Ferino commanded Moreau's right wing at Hüningen, Louis Desaix

Louis Charles Antoine Desaix () (17 August 176814 June 1800) was a French general and military leader during the French Revolutionary Wars. According to the usage of the time, he took the name ''Louis Charles Antoine Desaix de Veygoux''. He was co ...

commanded the center and Laurent Gouvion Saint-Cyr directed the left wing and included two divisions commanded by Guillaume Philibert Duhesme

Guillaume Philibert, 1st Count Duhesme (7 July 1766 in Mercurey (formerly ''Bourgneuf''), Burgundy – 20 June 1815 near Waterloo) was a French general during the Napoleonic Wars.

Revolution

Duhesme studied law and in 1792 was made colonel ...

, and Alexandre Camille Taponier

Alexandre Camille Taponier (2 February 1749–13 April 1831) commanded an infantry division in several battles during the French Revolutionary Wars. He joined the French Royal Army in 1767. He became a chef de bataillon on 15 October 1793 a ...

. Ferino's wing included three infantry and cavalry divisions under François Antoine Louis Bourcier, and general of division Augustin Tuncq

Augustin Tuncq, born in Conteville (Somme) on 27 August 1746 and died in Paris on 9 February 1800, served in the French military during the reign of the House of Bourbon and was a general of the French Revolutionary Wars. Most notably, he comma ...

, and Henri François Delaborde

Henri-François Delaborde (21 December 17643 February 1833) was a French general in the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars.

Early career

He was the son of a baker of Dijon. In 1783, Delaborde joined the ''Regiment of Condé Dra ...

. Desaix's command included three divisions led by Michel de Beaupuy, Antoine Guillaume Delmas and Charles Antoine Xaintrailles.

The French plan called for its two armies to press against the flanks of the Coalition's northern armies in the German states while simultaneously a third army approached Vienna through Italy. Specifically, Jean-Baptiste Jourdan

Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, 1st Count Jourdan (29 April 1762 – 23 November 1833), was a French military commander who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. He was made a Marshal of the Empire by Emperor Napoleon I in ...

's army would push south from Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second-largest city in ...

, hopefully drawing troops and attention toward themselves, which would allow Moreau’s army an easier crossing of the Rhine and Huningen and Kehl. If all went according to plan, Jourdan’s army could feint toward Mannheim, which would force Charles to reapportion his troops. Once Charles moved the mass of his army to the north, Moreau’s army, which early in the year had been stationed by Speyer

Speyer (, older spelling ''Speier'', French: ''Spire,'' historical English: ''Spires''; pfl, Schbaija) is a city in Rhineland-Palatinate in Germany with approximately 50,000 inhabitants. Located on the left bank of the river Rhine, Speyer li ...

, would move swiftly south to Strasbourg. From there, they could cross the river at Kehl, which was guarded by 7,000-man inexperienced and lightly trained militia—troops recruited that spring from the Swabian circle polities. In the south, by Basel, Ferino’s column was to move speedily across the river and advanced up the Rhine along the Swiss and German shoreline, toward Lake Constance

Lake Constance (german: Bodensee, ) refers to three bodies of water on the Rhine at the northern foot of the Alps: Upper Lake Constance (''Obersee''), Lower Lake Constance (''Untersee''), and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, called the Lak ...

and spread into the southern end of the Black Forest. Ideally, this would encircle and trap Charles and his army as the left wing of Moreau's army swung behind him, and as Jourdan's force cut off his flank with Wartensleben's autonomous corps.An autonomous corps, in the Austrian or Imperial armies, was an armed force under command of an experienced field commander. They usually included two divisions, but probably not more than three, and function with high maneuverability and independent action, hence the name "autonomous corps." Some, called the ''Frei-Corps'', or independent corps, were used as light infantry before the official formation of light infantry in the Habsburg Army in 1798. They provided the Army's skirmishing and scouting function; Frei-Corps were usually raised from the provinces, and often acted independently. See Philip Haythornthwaite, ''Austrian Army of the Napoleonic Wars (1): Infantry.'' Osprey Publishing, 2012, p. 24. Military historians usually maintain that Napoleon solidified the use of the autonomous corps, armies that could function without a great deal of direction, scatter about the countryside, but reform again quickly for battle; this was actually a development that first emerged first in the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

in the Thirteen British Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centur ...

and later in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of ...

, and became widely used in the European military as the size of armies grew in the 1790s and during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. See David Gates, ''The Napoleonic Wars 1803–1815,'' New York, Random House, 2011, Chapter 6.

Feint and a dual-pronged attack

Everything went according to the French plan, at least for the first six weeks. On 4 June 1796, 11,000 soldiers of the Army of the Sambre-et-Meuse, commanded by

Everything went according to the French plan, at least for the first six weeks. On 4 June 1796, 11,000 soldiers of the Army of the Sambre-et-Meuse, commanded by François Lefebvre

François () is a French masculine given name and surname, equivalent to the English name Francis.

People with the given name

* Francis I of France, King of France (), known as "the Father and Restorer of Letters"

* Francis II of France, King o ...

, pushed back a 6,500-man Austrian force at Altenkirchen

Altenkirchen () is a town in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, capital of the district of Altenkirchen. It is located approximately 40 km east of Bonn and 50 km north of Koblenz. Altenkirchen is the seat of the ''Verbandsgemeinde'' ("co ...

. On 6 June, the French placed Ehrenbreitstein

Ehrenbreitstein Fortress (german: Festung Ehrenbreitstein, ) is a fortress in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate, on the east bank of the Rhine where it is joined by the Moselle, overlooking the town of Koblenz.

Occupying the position of an ...

fortress under siege. At Wetzlar

Wetzlar () is a city in the state of Hesse, Germany. It is the twelfth largest city in Hesse with currently 55,371 inhabitants at the beginning of 2019 (including second homes). As an important cultural, industrial and commercial center, the un ...

on the Lahn, Lefebvre ran into Charles' concentration of 36,000 Austrians on 15 June. Casualties were light on both sides, but Jourdan pulled back to Niewied while Kléber retreated toward Düsseldorf. Pál Kray

Baron Paul Kray of Krajova and Topolya (german: Paul Freiherr Kray von Krajova und Topola; hu, Krajovai és Topolyai báró Kray Pál; 5 February 1735 – 19 January 1804), was a soldier, and general in Habsburg service during the Seven ...

, commanding 30,000 Austrian troops, rushed into battle with Kléber's 24,000 at Uckerath, east of Bonn

The federal city of Bonn ( lat, Bonna) is a city on the banks of the Rhine in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, with a population of over 300,000. About south-southeast of Cologne, Bonn is in the southernmost part of the Rhine-Ru ...

on 19 June, prompting the French to continue withdrawal to the north, enticing Kray to follow him. The actions confirmed to Charles that Jourdan intended to cross at the mid-Rhine, and he quickly moved sufficient of his force into place to address this threat.

Responding to the French feint, Charles committed most of his forces on the middle and northern Rhine, leaving only the Swabian militia at the Kehl-Strasbourg crossing, and a minor force commanded by Karl Aloys zu Fürstenberg at Rastatt

Rastatt () is a town with a Baroque core, District of Rastatt, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is located in the Upper Rhine Plain on the Murg river, above its junction with the Rhine and has a population of around 50,000 (2011). Rastatt was an ...

. In addition, a small force of about 5,000 French royalists under the command of the Louis Joseph, Prince of Condé, supposedly covering the Rhine from Switzerland to Freiburg im Breisgau

Freiburg im Breisgau (; abbreviated as Freiburg i. Br. or Freiburg i. B.; Low Alemannic: ''Friburg im Brisgau''), commonly referred to as Freiburg, is an independent city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. With a population of about 230,000 (as o ...

. Once Charles committed his main army to the mid and northern Rhine, however, Moreau executed an about face, and a forced march with most his army and arrived at Strasburg before Charles realized the French had even left Speyer. To accomplish this march rapidly, Moreau left his artillery behind; infantry and cavalry move more swiftly. On 20 June, his troops

A troop is a military sub-subunit, originally a small formation of cavalry, subordinate to a squadron. In many armies a troop is the equivalent element to the infantry section or platoon. Exceptions are the US Cavalry and the King's Troo ...

assaulted the forward posts between Strasbourg and the river, overwhelming the pickets there; the militia withdrew to Kehl, leaving behind their cannons, which solved part of Moreau's artillery problem.

Early in the morning on 24 June, Moreau and 3,000 men embarked in small boats and landed on the islands in the river between Strasbourg and the fortress at Kehl. They dislodged the imperial pickets there who, as one commentator observed "had not the time or address to destroy the bridges which communicate with the right bank of the Rhine; and the progress of the French remaining unimpeded, they crossed the river and suddenly attacked the redoubts of Kehl." Once the French had controlled the fortifications of Strasbourg and the river islands, Moreau’s advance guard, as many as 10,000 French skirmishers, some from the 3rd and 16th Demi-brigades commanded by the 24-year-old General Abbatucci, swarmed across the Kehl bridge and fell upon the several hundred Swabian pickets guarding the crossing. Once the skirmishers had done their jobs, Charles Mathieu Isidore Decaen

Charles Mathieu Isidore Decaen (, 13 April 1769 – 9 September 1832) was a French general who served during the French Revolutionary Wars, as Governor General of Pondicherry and the Isle de France (now Mauritius) and as commander of the Army ...

's and Joseph de Montrichard's infantry of 27,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry followed and secured the bridge. The Swabians were hopelessly outnumbered and could not be reinforced. Most of Charles' Army of the Rhine was stationed further north, by Mannheim, where the river was easier to cross, but too far to support the smaller force at Kehl. The only troops within relative easy distance were the Prince Condé’s émigré army at Freiburg and Karl Aloys zu Fürstenberg's force in Rastatt, neither of which could reach Kehl in time.

A second attack, simultaneous with the crossing at Kehl, occurred at Hüningen near Basel. After crossing unopposed, Ferino advanced in a dual-prong east along the German shore of the Rhine with the 16th and 50th demi-brigade

A ''demi-brigade'' ( en, Half-brigade) is a military formation used by the French Army since the French Revolutionary Wars. The ''Demi-brigade'' amalgamated the various infantry organizations of the French Revolutionary infantry into a single ...

s, the 68th and 50th and 68th line infantry, and six squadrons of cavalry that included the 3rd and 7th Hussars and the 10th Dragoons.

Within a day, Moreau had four divisions across the river at Kehl and another three at Hüningen. Unceremoniously thrust out of Kehl, the Swabian contingent reformed at Renchen on the 28th, where Count Sztáray and Prince von Lotheringen managed to pull the shattered force together and unite the disorganized Swabians with their own 2,000 troops. On 5 July, the two armies met again at Rastatt

Rastatt () is a town with a Baroque core, District of Rastatt, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is located in the Upper Rhine Plain on the Murg river, above its junction with the Rhine and has a population of around 50,000 (2011). Rastatt was an ...

. There, under command of Fürstenberg, the Swabians managed to hold the city until the 19,000 French troops turned both flanks and Fürstenberg opted for a strategic withdrawal. Ferino hurried eastward along the shore of the Rhine, to approach Charles' force from the rear and cut him off from Bavaria; Bourcier's division swung to the north, along the east side of the mountains, hoping to separate the Condé’s émigrés from the main force. Either division presented a danger of flanking the entire Coalition force, either Bourcier's on the west side of the Black Forest, or Ferino's on the east side. The Condé marched north and joined with Fürstenberg and the Swabians at Rastatt.

Aftermath

The immediate personnel losses seemed minor: at Kehl, the French lost about 150 killed, missing or wounded. The Swabian militia lost 700, plus 14 guns and 22 ammunition wagons. Immediately, the French set about securing their defensive position by establishing a pontoon bridge between Kehl and Strasbourg, which allowed Moreau to send his cavalry and captured artillery across the river.Clarke, p. 186. Strategic losses seemed far greater. The French army's ability to cross the Rhine at will gave them an advantage. Charles could not move much of his army away from Mannheim or Karlsruhe, where the French had also formed across the river; loss of the crossings at Hüningen, near the Swiss city of Basel, and the crossing at Kehl, near the Alsatian city of Strasbourg, guaranteed the French ready-access to most of southwestern Germany. From there, Moreau's troops could fan out over the flood plain around Kehl to prevent any approach from Rastadt or Offenburg. To avoid Ferino's flanking maneuver, Charles executed an orderly withdrawal in four columns through the Black Forest, across the Upper Danube valley, and toward Bavaria, trying to maintain consistent contact with all flanks as each column withdrew through the Black Forest and the Upper Danube. By mid-July, the column to which the Swabians were attached encamped near Stuttgart. The third column, which included the Condé’s Corps, retreated through Waldsee toStockach

Stockach is a town in the district of Konstanz, in southern Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

Location

It is situated in the Hegau region, about 5 km northwest of Lake Constance, 13 km north of Radolfzell and 25 km northwest of Konstan ...

, and, eventually Ravensburg

Ravensburg ( Swabian: ''Raveschburg'') is a city in Upper Swabia in Southern Germany, capital of the district of Ravensburg, Baden-Württemberg.

Ravensburg was first mentioned in 1088. In the Middle Ages, it was an Imperial Free City and an im ...

. The fourth Austrian column, the smallest (three battalions and four squadrons) commanded by Ludwig Wolff de la Marselle

Ludwig Wolff de la Marselle or Ludwig Dominik Joseph Regis Wolff de la Marselle (13 March 1747 – 14 October 1804) was a general in Habsburg Austrian service in the French Revolutionary Wars. He was born and died in Mons, Austrian Netherlands (p ...

, retreated the length of the Bodensee’s northern shore, via Überlingen

Überlingen is a German city on the northern shore of Lake Constance (Bodensee) in Baden-Württemberg near the border with Switzerland. After the city of Friedrichshafen, it is the second largest city in the Bodenseekreis (district), and a cent ...

, Meersburg

Meersburg () is a town in Baden-Württemberg in the southwest of Germany. It is on Lake Constance.

It is known for its medieval city. The lower town ("Unterstadt") and upper town ("Oberstadt") are reserved for pedestrians only, and connected by t ...

, Buchhorn

Friedrichshafen ( or ; Low Alemannic: ''Hafe'' or ''Fridrichshafe'') is a city on the northern shoreline of Lake Constance (the ''Bodensee'') in Southern Germany, near the borders of both Switzerland and Austria. It is the district capital (''Krei ...

, and the Austrian city of Bregenz

Bregenz (; gsw, label= Vorarlbergian, Breagaz ) is the capital of Vorarlberg, the westernmost state of Austria. The city lies on the east and southeast shores of Lake Constance, the third-largest freshwater lake in Central Europe, between Swit ...

.

The subsequent territorial losses were significant. Moreau's attack forced Charles to withdraw far enough into Bavaria to align his northern flank in a roughly perpendicular line (north to south) with Wartensleben's autonomous corps. This array protected the Danube valley and denied the French access to Vienna. His own front would prevent Moreau from flanking Wartensleben from the south; similarly, Wartensleben's flank would prevent Jourdan from encircling his own force from the north. Together, he and Wartensleben could resist the French onslaught. However, in the course of this withdrawal, he abandoned most of the Swabian Circle to the French occupation. At the end of July, eight thousand of Charles' men under command of Fröhlich executed a dawn attack on the Swabian camp at Biberach, disarmed the remaining three thousand Swabian troops, and impounded their weapons. The Swabian Circle successfully negotiated with the French for neutrality; during negotiations, there was considerable discussion over how the Swabians would hand over their weapons to the French, but it was moot: the weapons had already been taken by Fröhlich. As Charles withdrew further east, the neutral zone expanded, eventually encompassing most of southern German states and the Ernestine duchies

The Ernestine duchies (), also known as the Saxon duchies (, although the Albertine appanage duchies of Weissenfels, Merseburg and Zeitz were also "Saxon duchies" and adjacent to several Ernestine ones), were a group of small states whose n ...

.

The situation reversed when Charles and Wartensleben's forces reunited to defeat Jourdan's army at the battles of Amberg

Amberg () is a town in Bavaria, Germany. It is located in the Upper Palatinate, roughly halfway between Regensburg and Bayreuth. In 2020, over 42,000 people lived in the town.

History

The town was first mentioned in 1034, at that time under t ...

, Würzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is a city in the region of Franconia in the north of the German state of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the '' Regierungsbezirk'' Lower Franconia. It spans the banks of the Main River.

Würzbur ...

and 2nd Altenkirchen. On 18 September, an Austrian division under Feldmarschall-Leutnant Petrasch stormed the Rhine bridgehead at Kehl, but a French counterattack

A counterattack is a tactic employed in response to an attack, with the term originating in " war games". The general objective is to negate or thwart the advantage gained by the enemy during attack, while the specific objectives typically see ...

drove them out. Even though the French still held the crossing between Kehl and Strasbourg, Petrasch's Austrians controlled the territory leading to the crossing. After battles at Emmendingen

Emmendingen (; Low Alemannic: ''Emmedinge'') is a town in Baden-Württemberg, capital of the district Emmendingen of Germany. It is located at the Elz River, north of Freiburg im Breisgau. The town contains more than 26,000 residents, which ...

(19 October) and Schliengen

Schliengen is a municipality in southwestern Germany in the state of Baden-Württemberg, in the '' Kreis'' (district) of Lörrach. Schliengen's claim to international fame is the Battle of Schliengen (24 October 1796), fought between forces of t ...

(24 October), Moreau withdrew his troops south to Hüningen. Once safe on French soil, the French refused to part with Kehl

Kehl (; gsw, label= Low Alemannic, Kaal) is a town in southwestern Germany in the Ortenaukreis, Baden-Württemberg. It is on the river Rhine, directly opposite the French city of Strasbourg, with which it shares some municipal servicesfor exa ...

or Hüningen, leading to over 100 days of siege at both locations.Philippart, p. 127.

Orders of battle

French

Adjutant General Abbatucci commanding:Smith, p. 115 :Generals of Brigade Decaen,Montrichard

Montrichard () is a town and former commune in the Loir-et-Cher department, Centre-Val de Loire, France. On 1 January 2016, it was merged into the new commune of Montrichard Val de Cher.

During the French Revolution, the commune was known as ' ...

:*3rd Demi-brigade (light) (2nd battalion)The French Army designated two kinds of infantry: ''d'infanterie légère'', or light infantry, to provide skirmishing cover for the troops that followed, principally ''d’infanterie de ligne'', which fought in tight formations. Smith, p. 15.

:*11th Demi-brigade (light) (1st battalion)

:*31st, 56th and 89th Demi-brigade (line) (three battalions each)

Habsburg/Coalition

The Swabian Circle Contingent: :*Infantry Regiments: Württemberg, Baden-Durlach, Fugger, Wolfegg (two battalions each) :*Hohenzollern Royal and Imperial (KürK) Cavalry (four squadrons) :*Württemberg Dragoons (four squadrons) :*two field artillery battalionsNotes and citations

Notes

Citations

Alphabetical listing of sources cited

* Bertaud, Jean Paul, R.R. Palmer (trans). ''The Army of the French Revolution: From Citizen-Soldiers to Instrument of Power.'' Princeton University Press, 1988. . * Blanning, Timothy. ''The French Revolutionary Wars.'' New York, Oxford University Press, 1996. * Clarke, Hewson, ''The History of the War from the Commencement of the French Revolution,'' London, T. Kinnersley, 1816. * Dodge, Theodore Ayrault, ''Warfare in the Age of Napoleon: The Revolutionary Wars Against the First Coalition in Northern Europe and the Italian Campaign, 1789–1797'', USA, Leonaur, 2011. * Gates, David, ''The Napoleonic Wars 1803–1815,'' New York, Random House, 2011. * Graham, Thomas, Baron Lynedoch''The History of the Campaign of 1796 in Germany and Italy.''

London, 1797. . * Hansard, Thomas C (ed.). ''Hansard's Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, 1803'', Official Report. Vol. 1. London: HMSO, 1803, pp. 249–252 * Haythornthwaite, Philip. ''Austrian Army of the Napoleonic Wars (1): Infantry.'' Oxford, Osprey Publishing, 2012. * Knepper, Thomas P. ''The Rhine.'' Handbook for Environmental Chemistry Series, Part L. New York: Springer, 2006, . * Nafziger, George

''French Troops Destined to Cross the Rhine, 24 June 1796''

US Army Combined Arms Center. Accessed 2 October 2014. * Philippart, John

''Memoires etc. of General Moreau''

London, A.J. Valpy, 1814. * Phipps, Ramsay Weston ''The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume II The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle.'' USA, Pickle Partners Publishing, 2011 923–1933 * Rickard, J

''Combat of Uckerath, 19 June 1796''

Feb 2009 version, accessed 1 March 2015. * Rothenberg, Gunther E. "The Habsburg Army in the Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815)." ''Military Affairs'', 37:1 (Feb 1973), 1–5. * Smith, Digby. ''The Napoleonic Wars Data Book''. London, Greenhill, 1998. * Vann, James Allen. ''The Swabian Kreis: Institutional Growth in the Holy Roman Empire 1648–1715.'' Vol. LII, Studies Presented to International Commission for the History of Representative and Parliamentary Institutions. Bruxelles, 1975. * Volk, Helmut

"Landschaftsgeschichte und Natürlichkeit der Baumarten in der Rheinaue."

''Waldschutzgebiete Baden-Württemberg'', Band 10, pp. 159–167. * Walker, Mack. ''German Home Towns: Community, State, and General Estate, 1648–1871.'' Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1998. * Whaley, Joachim. ''Germany and the Holy Roman Empire: Volume I: Maximilian I to the Peace of Westphalia, 1493–1648''. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2012. * Wilson, Peter Hamish. ''German Armies: War and German Politics 1648–1806.'' London, UCL Press, 1997. . {{DEFAULTSORT:Kehl 1796, Battle of

Kehl

Kehl (; gsw, label= Low Alemannic, Kaal) is a town in southwestern Germany in the Ortenaukreis, Baden-Württemberg. It is on the river Rhine, directly opposite the French city of Strasbourg, with which it shares some municipal servicesfor exa ...

Kehl

Kehl (; gsw, label= Low Alemannic, Kaal) is a town in southwestern Germany in the Ortenaukreis, Baden-Württemberg. It is on the river Rhine, directly opposite the French city of Strasbourg, with which it shares some municipal servicesfor exa ...

Kehl

Kehl (; gsw, label= Low Alemannic, Kaal) is a town in southwestern Germany in the Ortenaukreis, Baden-Württemberg. It is on the river Rhine, directly opposite the French city of Strasbourg, with which it shares some municipal servicesfor exa ...

Kehl

Kehl (; gsw, label= Low Alemannic, Kaal) is a town in southwestern Germany in the Ortenaukreis, Baden-Württemberg. It is on the river Rhine, directly opposite the French city of Strasbourg, with which it shares some municipal servicesfor exa ...

Kehl

Kehl (; gsw, label= Low Alemannic, Kaal) is a town in southwestern Germany in the Ortenaukreis, Baden-Württemberg. It is on the river Rhine, directly opposite the French city of Strasbourg, with which it shares some municipal servicesfor exa ...

1796 in the Holy Roman Empire

Kehl

Kehl (; gsw, label= Low Alemannic, Kaal) is a town in southwestern Germany in the Ortenaukreis, Baden-Württemberg. It is on the river Rhine, directly opposite the French city of Strasbourg, with which it shares some municipal servicesfor exa ...