Battle of Chancellorsville on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the

Hooker's army faced Lee across the Rappahannock from its winter quarters in Falmouth and around Fredericksburg. Hooker developed a strategy that was, on paper, superior to those of his predecessors. He planned to send his 10,000 cavalrymen under Maj. Gen. George Stoneman to cross the Rappahannock far upstream and raid deep into the Confederate rear areas, destroying crucial supply depots along the railroad from the Confederate capital in Richmond to Fredericksburg, which would cut Lee's lines of communication and supply.Gallagher, pp. 9–10; Eicher, p. 474; Cullen, pp. 17–18; Welcher, p. 659; Sears, pp. 120–24.

Hooker reasoned that Lee would react to this threat by abandoning his fortified positions on the Rappahannock and withdrawing toward his capital. At that time, Hooker's infantry would cross the Rappahannock in pursuit, attacking Lee when he was moving and vulnerable. Stoneman attempted to execute this turning movement on April 13, but heavy rains made the river crossing site at Sulphur Spring impassable. President Lincoln lamented, "I greatly fear it is another failure already." Hooker was forced to create a new plan for a meeting with Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and general in chief Henry W. Halleck in Aquia on April 19.

Hooker's second plan was to launch both his cavalry and infantry simultaneously in a bold double envelopment of Lee's army. Stoneman's cavalry would make a second attempt at its deep strategic raid, but at the same time, 42,000 men in three corps (V, XI, XII Corps) would stealthily march to cross the Rappahannock upriver at Kelly's Ford. They would then proceed south and cross the Rapidan at Germanna and Ely's Ford, concentrate at the Chancellorsville crossroads, and attack Lee's army from the west.Cullen, p. 17; Gallagher, pp. 10–11; Welcher, p. 659; Sears, pp. 137–38.

While they were under way, 10,000 men in two divisions from the II Corps would cross at the U.S. Ford and join with the V Corps in pushing the Confederates away from the river. The second half of the double envelopment was to come from the east: 40,000 men in two corps (I and VI Corps, under the overall command of John Sedgwick) would cross the Rappahannock below Fredericksburg and threaten to attack Stonewall Jackson's position on the Confederate right flank.

The remaining 25,000 men (III Corps and one division of the II Corps) would remain visible in their camps at Falmouth to divert Confederate attention from the turning movement. Hooker anticipated that Lee would either be forced to retreat, in which case he would be vigorously pursued, or he would be forced to attack the Union Army on unfavorable terrain.

One of the defining characteristics of the battlefield was a dense woodland south of the Rapidan known locally as the "Wilderness of Spotsylvania". The area had once been an open broadleaf forest, but during colonial times the trees were gradually cut down to make charcoal for local pig iron furnaces. When the supply of wood was exhausted, the furnaces were abandoned and secondary forest growth developed, creating a dense mass of brambles, thickets, vines, and low-lying vegetation.Sears, pp. 132, 193–94; Krick, pp. 35–36; Gallagher, pp. 11–13; Cullen, p. 19.

Hooker's army faced Lee across the Rappahannock from its winter quarters in Falmouth and around Fredericksburg. Hooker developed a strategy that was, on paper, superior to those of his predecessors. He planned to send his 10,000 cavalrymen under Maj. Gen. George Stoneman to cross the Rappahannock far upstream and raid deep into the Confederate rear areas, destroying crucial supply depots along the railroad from the Confederate capital in Richmond to Fredericksburg, which would cut Lee's lines of communication and supply.Gallagher, pp. 9–10; Eicher, p. 474; Cullen, pp. 17–18; Welcher, p. 659; Sears, pp. 120–24.

Hooker reasoned that Lee would react to this threat by abandoning his fortified positions on the Rappahannock and withdrawing toward his capital. At that time, Hooker's infantry would cross the Rappahannock in pursuit, attacking Lee when he was moving and vulnerable. Stoneman attempted to execute this turning movement on April 13, but heavy rains made the river crossing site at Sulphur Spring impassable. President Lincoln lamented, "I greatly fear it is another failure already." Hooker was forced to create a new plan for a meeting with Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and general in chief Henry W. Halleck in Aquia on April 19.

Hooker's second plan was to launch both his cavalry and infantry simultaneously in a bold double envelopment of Lee's army. Stoneman's cavalry would make a second attempt at its deep strategic raid, but at the same time, 42,000 men in three corps (V, XI, XII Corps) would stealthily march to cross the Rappahannock upriver at Kelly's Ford. They would then proceed south and cross the Rapidan at Germanna and Ely's Ford, concentrate at the Chancellorsville crossroads, and attack Lee's army from the west.Cullen, p. 17; Gallagher, pp. 10–11; Welcher, p. 659; Sears, pp. 137–38.

While they were under way, 10,000 men in two divisions from the II Corps would cross at the U.S. Ford and join with the V Corps in pushing the Confederates away from the river. The second half of the double envelopment was to come from the east: 40,000 men in two corps (I and VI Corps, under the overall command of John Sedgwick) would cross the Rappahannock below Fredericksburg and threaten to attack Stonewall Jackson's position on the Confederate right flank.

The remaining 25,000 men (III Corps and one division of the II Corps) would remain visible in their camps at Falmouth to divert Confederate attention from the turning movement. Hooker anticipated that Lee would either be forced to retreat, in which case he would be vigorously pursued, or he would be forced to attack the Union Army on unfavorable terrain.

One of the defining characteristics of the battlefield was a dense woodland south of the Rapidan known locally as the "Wilderness of Spotsylvania". The area had once been an open broadleaf forest, but during colonial times the trees were gradually cut down to make charcoal for local pig iron furnaces. When the supply of wood was exhausted, the furnaces were abandoned and secondary forest growth developed, creating a dense mass of brambles, thickets, vines, and low-lying vegetation.Sears, pp. 132, 193–94; Krick, pp. 35–36; Gallagher, pp. 11–13; Cullen, p. 19.

On April 27–28, the initial three corps of the Army of the Potomac began their march under the leadership of Slocum. They crossed the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers as planned and began to concentrate on April 30 around the hamlet of Chancellorsville, which was little more than a single large, brick mansion at the junction of the Orange Turnpike and Orange Plank Road. Built in the early 19th century, it had been used as an inn on the turnpike for many years, but now served as a home for the Frances Chancellor family. Some of the family remained in the house during the battle.Esposito, text for map 84; Gallagher, pp. 13–14; Salmon, p. 175; Sears, pp. 141–58; Krick, p. 32; Eicher, pp. 475, 477; Welcher, pp. 660–61.

Hooker arrived late in the afternoon on April 30 and made the mansion his headquarters. Stoneman's cavalry began on April 30 its second attempt to reach Lee's rear areas. Two divisions of II Corps crossed at U.S. Ford on April 30 without opposition. By dawn on April 29, pontoon bridges spanned the Rappahannock south of Fredericksburg and Sedgwick's force began to cross.

Pleased with the success of the operation so far, and realizing that the Confederates were not vigorously opposing the river crossings, Hooker ordered Sickles to begin the movement of the III Corps from Falmouth the night of April 30 – May 1. By May 1, Hooker had approximately 70,000 men concentrated in and around Chancellorsville.

On April 27–28, the initial three corps of the Army of the Potomac began their march under the leadership of Slocum. They crossed the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers as planned and began to concentrate on April 30 around the hamlet of Chancellorsville, which was little more than a single large, brick mansion at the junction of the Orange Turnpike and Orange Plank Road. Built in the early 19th century, it had been used as an inn on the turnpike for many years, but now served as a home for the Frances Chancellor family. Some of the family remained in the house during the battle.Esposito, text for map 84; Gallagher, pp. 13–14; Salmon, p. 175; Sears, pp. 141–58; Krick, p. 32; Eicher, pp. 475, 477; Welcher, pp. 660–61.

Hooker arrived late in the afternoon on April 30 and made the mansion his headquarters. Stoneman's cavalry began on April 30 its second attempt to reach Lee's rear areas. Two divisions of II Corps crossed at U.S. Ford on April 30 without opposition. By dawn on April 29, pontoon bridges spanned the Rappahannock south of Fredericksburg and Sedgwick's force began to cross.

Pleased with the success of the operation so far, and realizing that the Confederates were not vigorously opposing the river crossings, Hooker ordered Sickles to begin the movement of the III Corps from Falmouth the night of April 30 – May 1. By May 1, Hooker had approximately 70,000 men concentrated in and around Chancellorsville.

In his Fredericksburg headquarters, Lee was initially in the dark about the Union intentions and he suspected that the main column under Slocum was heading towards Gordonsville. Jeb Stuart's cavalry was cut off at first by Stoneman's departure on April 30, but they were soon able to move freely around the army's flanks on their reconnaissance missions after almost all their Union counterparts had left the area.Salmon, pp. 176–77; Gallagher, pp. 16–17; Krick, pp. 39; Salmon, pp. 176–77; Cullen, pp. 21–22; Sears, pp. 187–89.

As Stuart's intelligence information about the Union river crossings began to arrive, Lee did not react as Hooker had anticipated. He decided to violate one of the generally accepted principles of war and divide his force in the face of a superior enemy, hoping that aggressive action would allow him to attack and defeat a portion of Hooker's army before it could be fully concentrated against him. He became convinced that Sedgwick's force would demonstrate against him, but not become a serious threat, so he ordered about 4/5 of his army to meet the challenge from Chancellorsville. He left behind a brigade under Brig. Gen. William Barksdale on heavily fortified Marye's Heights behind Fredericksburg and one division under Maj. Gen.

In his Fredericksburg headquarters, Lee was initially in the dark about the Union intentions and he suspected that the main column under Slocum was heading towards Gordonsville. Jeb Stuart's cavalry was cut off at first by Stoneman's departure on April 30, but they were soon able to move freely around the army's flanks on their reconnaissance missions after almost all their Union counterparts had left the area.Salmon, pp. 176–77; Gallagher, pp. 16–17; Krick, pp. 39; Salmon, pp. 176–77; Cullen, pp. 21–22; Sears, pp. 187–89.

As Stuart's intelligence information about the Union river crossings began to arrive, Lee did not react as Hooker had anticipated. He decided to violate one of the generally accepted principles of war and divide his force in the face of a superior enemy, hoping that aggressive action would allow him to attack and defeat a portion of Hooker's army before it could be fully concentrated against him. He became convinced that Sedgwick's force would demonstrate against him, but not become a serious threat, so he ordered about 4/5 of his army to meet the challenge from Chancellorsville. He left behind a brigade under Brig. Gen. William Barksdale on heavily fortified Marye's Heights behind Fredericksburg and one division under Maj. Gen.

Jackson's men began marching west to join with Anderson before dawn on May 1. Jackson himself met with Anderson near Zoan Church at 8 a.m., finding that McLaws's division had already arrived to join the defensive position. But Stonewall Jackson was not in a defensive mood. He ordered an advance at 11 a.m. along two roads toward Chancellorsville: McLaws's division and the brigade of Brig. Gen. William Mahone on the Turnpike, and Anderson's other brigades and Jackson's arriving units on the Plank Road.Salmon, p. 177; Welcher, p. 663; Gallagher, pp. 17–19; Cullen, pp. 23–25; Sears, pp. 196–202; Krick, p. 40.

At about the same time, Hooker ordered his men to advance on three roads to the east: two divisions of Meade's V Corps (Griffin and Humphreys) on the River Road to uncover Banks's Ford, and the remaining division (Sykes) on the Turnpike; and Slocum's XII Corps on the Plank Road, with Howard's XI Corps in close support. Couch's II Corps was placed in reserve, where it would be soon joined by Sickles's III Corps.

The first shots of the Battle of Chancellorsville were fired at 11:20 a.m. as the armies collided. McLaws's initial attack pushed back Sykes's division. The Union general organized a counterattack that recovered the lost ground. Anderson then sent a brigade under Brig. Gen.

Jackson's men began marching west to join with Anderson before dawn on May 1. Jackson himself met with Anderson near Zoan Church at 8 a.m., finding that McLaws's division had already arrived to join the defensive position. But Stonewall Jackson was not in a defensive mood. He ordered an advance at 11 a.m. along two roads toward Chancellorsville: McLaws's division and the brigade of Brig. Gen. William Mahone on the Turnpike, and Anderson's other brigades and Jackson's arriving units on the Plank Road.Salmon, p. 177; Welcher, p. 663; Gallagher, pp. 17–19; Cullen, pp. 23–25; Sears, pp. 196–202; Krick, p. 40.

At about the same time, Hooker ordered his men to advance on three roads to the east: two divisions of Meade's V Corps (Griffin and Humphreys) on the River Road to uncover Banks's Ford, and the remaining division (Sykes) on the Turnpike; and Slocum's XII Corps on the Plank Road, with Howard's XI Corps in close support. Couch's II Corps was placed in reserve, where it would be soon joined by Sickles's III Corps.

The first shots of the Battle of Chancellorsville were fired at 11:20 a.m. as the armies collided. McLaws's initial attack pushed back Sykes's division. The Union general organized a counterattack that recovered the lost ground. Anderson then sent a brigade under Brig. Gen.

Early on the morning of May 2, Hooker began to realize that Lee's actions on May 1 had not been constrained by the threat of Sedgwick's force at Fredericksburg, so no further deception was needed on that front. He decided to summon the I Corps of Maj. Gen.

Early on the morning of May 2, Hooker began to realize that Lee's actions on May 1 had not been constrained by the threat of Sedgwick's force at Fredericksburg, so no further deception was needed on that front. He decided to summon the I Corps of Maj. Gen.  Significant contributions to the impending Union disaster were the nature of the Union XI Corps and the incompetent performance of its commander, Maj. Gen.

Significant contributions to the impending Union disaster were the nature of the Union XI Corps and the incompetent performance of its commander, Maj. Gen.  Around 5:30 p.m., Jackson turned to Robert Rodes and asked him "General, are you ready?" When Rodes nodded, Jackson replied, "You may go forward then." Most of the men of the XI Corps were encamped and sitting down for supper and had their rifles unloaded and stacked. Their first clue to the impending onslaught was the observation of numerous animals, such as rabbits and foxes, fleeing in their direction out of the western woods. This was followed by the crackle of musket fire, and then the unmistakable scream of the " Rebel Yell".

Two of von Gilsa's regiments, the 153rd Pennsylvania and 54th New York, had been placed up as a heavy skirmish line and the massive Confederate assault rolled completely over them. A few men managed to get off a shot or two before fleeing. The pair of artillery pieces at the very end of the XI Corps line were captured by the Confederates and promptly turned on their former owners. Devens's division collapsed in a matter of minutes, slammed on three sides by almost 30,000 Confederates. Col.

Around 5:30 p.m., Jackson turned to Robert Rodes and asked him "General, are you ready?" When Rodes nodded, Jackson replied, "You may go forward then." Most of the men of the XI Corps were encamped and sitting down for supper and had their rifles unloaded and stacked. Their first clue to the impending onslaught was the observation of numerous animals, such as rabbits and foxes, fleeing in their direction out of the western woods. This was followed by the crackle of musket fire, and then the unmistakable scream of the " Rebel Yell".

Two of von Gilsa's regiments, the 153rd Pennsylvania and 54th New York, had been placed up as a heavy skirmish line and the massive Confederate assault rolled completely over them. A few men managed to get off a shot or two before fleeing. The pair of artillery pieces at the very end of the XI Corps line were captured by the Confederates and promptly turned on their former owners. Devens's division collapsed in a matter of minutes, slammed on three sides by almost 30,000 Confederates. Col.

By nightfall, the Confederate Second Corps had advanced more than 1.25 miles, to within sight of Chancellorsville, but darkness and confusion were taking their toll. The attackers were almost as disorganized as the routed defenders. Although the XI Corps had been defeated, it had retained some coherence as a unit. The corps suffered nearly 2,500 casualties (259 killed, 1,173 wounded, and 994 missing or captured), about one quarter of its strength, including 12 of 23 regimental commanders, which suggests that they fought fiercely during their retreat.Sears, pp. 281, 287, 289–91, 300–302, 488; Welcher, p. 673; Eicher, p. 483; Salmon, p. 180; Krick, pp. 146–48.

Jackson's force was now separated from Lee's men only by Sickles's corps, which had been separated from the main body of the army after its foray attacking Jackson's column earlier in the afternoon. Like everyone else in the Union army, the III Corps had been unaware of Jackson's attack. When he first heard the news, Sickles was skeptical, but finally believed it and decided to pull back to Hazel Grove.

Sickles became increasingly nervous, knowing that his troops were facing an unknown number of Confederates to the west. A patrol of Jackson's troops was driven back by Union gunners, a minor incident that would come to be exaggerated into a heroic repulse of Jackson's entire command. Between 11 p.m. and midnight, Sickles organized an assault north from Hazel Grove toward the Plank Road, but called it off when his men began suffering artillery and rifle friendly fire from the Union XII Corps.

Stonewall Jackson wanted to press his advantage before Hooker and his army could regain their bearings and plan a counterattack, which might still succeed because of the sheer disparity in numbers. He rode out onto the Plank Road that night to determine the feasibility of a night attack by the light of the full moon, traveling beyond the farthest advance of his men. When one of his staff officers warned him about the dangerous position, Jackson replied, "The danger is all over. The enemy is routed. Go back and tell A.P. Hill to press right on."

As he and his staff started to return, they were incorrectly identified as Union cavalry by men of the

By nightfall, the Confederate Second Corps had advanced more than 1.25 miles, to within sight of Chancellorsville, but darkness and confusion were taking their toll. The attackers were almost as disorganized as the routed defenders. Although the XI Corps had been defeated, it had retained some coherence as a unit. The corps suffered nearly 2,500 casualties (259 killed, 1,173 wounded, and 994 missing or captured), about one quarter of its strength, including 12 of 23 regimental commanders, which suggests that they fought fiercely during their retreat.Sears, pp. 281, 287, 289–91, 300–302, 488; Welcher, p. 673; Eicher, p. 483; Salmon, p. 180; Krick, pp. 146–48.

Jackson's force was now separated from Lee's men only by Sickles's corps, which had been separated from the main body of the army after its foray attacking Jackson's column earlier in the afternoon. Like everyone else in the Union army, the III Corps had been unaware of Jackson's attack. When he first heard the news, Sickles was skeptical, but finally believed it and decided to pull back to Hazel Grove.

Sickles became increasingly nervous, knowing that his troops were facing an unknown number of Confederates to the west. A patrol of Jackson's troops was driven back by Union gunners, a minor incident that would come to be exaggerated into a heroic repulse of Jackson's entire command. Between 11 p.m. and midnight, Sickles organized an assault north from Hazel Grove toward the Plank Road, but called it off when his men began suffering artillery and rifle friendly fire from the Union XII Corps.

Stonewall Jackson wanted to press his advantage before Hooker and his army could regain their bearings and plan a counterattack, which might still succeed because of the sheer disparity in numbers. He rode out onto the Plank Road that night to determine the feasibility of a night attack by the light of the full moon, traveling beyond the farthest advance of his men. When one of his staff officers warned him about the dangerous position, Jackson replied, "The danger is all over. The enemy is routed. Go back and tell A.P. Hill to press right on."

As he and his staff started to return, they were incorrectly identified as Union cavalry by men of the

Despite the fame of Stonewall Jackson's victory on May 2, it did not result in a significant military advantage for the Army of Northern Virginia. Howard's XI Corps had been defeated, but the Army of the Potomac remained a potent force and Reynolds's I Corps had arrived overnight, which replaced Howard's losses. About 76,000 Union men faced 43,000 Confederate at the Chancellorsville front. The two halves of Lee's army at Chancellorsville were separated by Sickles's III Corps, which occupied a strong position on high ground at Hazel Grove.Goolrick, 140–42; Esposito, text for map 88; Sears, pp. 312–14, 316–20; Salmon, pp. 181–82; Cullen, pp. 36–39; Welcher, p. 675.

Unless Lee could devise a plan to eject Sickles from Hazel Grove and combine the two halves of his army, he would have little chance of success in assaulting the formidable Union earthworks around Chancellorsville. Fortunately for Lee, Joseph Hooker inadvertently cooperated. Early on May 3, Hooker ordered Sickles to move from Hazel Grove to a new position on the Plank Road. As they were withdrawing, the trailing elements of Sickles's corps were attacked by the Confederate brigade of Brig. Gen.

Despite the fame of Stonewall Jackson's victory on May 2, it did not result in a significant military advantage for the Army of Northern Virginia. Howard's XI Corps had been defeated, but the Army of the Potomac remained a potent force and Reynolds's I Corps had arrived overnight, which replaced Howard's losses. About 76,000 Union men faced 43,000 Confederate at the Chancellorsville front. The two halves of Lee's army at Chancellorsville were separated by Sickles's III Corps, which occupied a strong position on high ground at Hazel Grove.Goolrick, 140–42; Esposito, text for map 88; Sears, pp. 312–14, 316–20; Salmon, pp. 181–82; Cullen, pp. 36–39; Welcher, p. 675.

Unless Lee could devise a plan to eject Sickles from Hazel Grove and combine the two halves of his army, he would have little chance of success in assaulting the formidable Union earthworks around Chancellorsville. Fortunately for Lee, Joseph Hooker inadvertently cooperated. Early on May 3, Hooker ordered Sickles to move from Hazel Grove to a new position on the Plank Road. As they were withdrawing, the trailing elements of Sickles's corps were attacked by the Confederate brigade of Brig. Gen.

1863. Revere, Joseph Warren. Published by C. A. Alvord. division commander Maj. Gen. Hiram Berry was mortally wounded after charging the Confederate line. Next in seniority was General Mott, who was severely wounded; therefore, General Joseph Warren Revere (grandson of Paul Revere) assumed command of the group. As the battle lacked a clear

As Lee was savoring his victory at the Chancellorsville crossroads, he received disturbing news: Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick's force had broken through the Confederate lines at Fredericksburg and was headed toward Chancellorsville. On the night of May 2, in the aftermath of Jackson's flank attack, Hooker had ordered Sedgwick to "cross the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg on the receipt of this order, and at once take up your line of march on the Chancellorsville road until you connect with him. You will attack and destroy any force you may fall in with on the road."Sears, pp. 308–11, 350–51; Welcher, pp. 679–80; Cullen, pp. 41–42; Goolrick, pp. 151–53.

Lee had left a relatively small force at Fredericksburg, ordering Brig. Gen. Jubal Early to "watch the enemy and try to hold him." If he was attacked in "overwhelming numbers," Early was to retreat to Richmond, but if Sedgwick withdrew from his front, he was to join with Lee at Chancellorsville. On the morning of May 2, Early received a garbled message from Lee's staff that caused him to start marching most of his men toward Chancellorsville, but he quickly returned after a warning from Brig. Gen. William Barksdale of a Union advance against Fredericksburg.

At 7 a.m. on May 3, Early was confronted with four Union divisions: Brig. Gen. John Gibbon of the II Corps had crossed the Rappahannock north of town, and three divisions of Sedgwick's VI Corps—Maj. Gen. John Newton and Brig. Gens.

As Lee was savoring his victory at the Chancellorsville crossroads, he received disturbing news: Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick's force had broken through the Confederate lines at Fredericksburg and was headed toward Chancellorsville. On the night of May 2, in the aftermath of Jackson's flank attack, Hooker had ordered Sedgwick to "cross the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg on the receipt of this order, and at once take up your line of march on the Chancellorsville road until you connect with him. You will attack and destroy any force you may fall in with on the road."Sears, pp. 308–11, 350–51; Welcher, pp. 679–80; Cullen, pp. 41–42; Goolrick, pp. 151–53.

Lee had left a relatively small force at Fredericksburg, ordering Brig. Gen. Jubal Early to "watch the enemy and try to hold him." If he was attacked in "overwhelming numbers," Early was to retreat to Richmond, but if Sedgwick withdrew from his front, he was to join with Lee at Chancellorsville. On the morning of May 2, Early received a garbled message from Lee's staff that caused him to start marching most of his men toward Chancellorsville, but he quickly returned after a warning from Brig. Gen. William Barksdale of a Union advance against Fredericksburg.

At 7 a.m. on May 3, Early was confronted with four Union divisions: Brig. Gen. John Gibbon of the II Corps had crossed the Rappahannock north of town, and three divisions of Sedgwick's VI Corps—Maj. Gen. John Newton and Brig. Gens.  By midmorning, two Union attacks against the infamous stone wall on Marye's Heights were repulsed with numerous casualties. A Union party under flag of truce was allowed to approach ostensibly to collect the wounded, but while close to the stone wall, they were able to observe how sparsely the Confederate line was manned. A third Union attack was successful in overrunning the Confederate position. Early was able to organize an effective fighting retreat.Krick, pp. 176–80; Welcher, pp. 680–81; Esposito, text for maps 88–89; Sears, pp. 352–56.

John Sedgwick's road to Chancellorsville was open, but he wasted time in gathering his troops and forming a marching column. His men, led by Brooks's division, followed by Newton and Howe, were delayed for several hours by successive actions against the Alabama brigade of Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox. His final delaying line was a ridge at Salem church, where he was joined by three brigades from McLaws's division and one from Anderson's, bringing the total Confederate strength to about 10,000 men.

Artillery fire was exchanged by both sides in the afternoon and at 5:30 p.m., two brigades of Brooks's division attacked on both sides of the Plank Road. The advance south of the road reached as far as the churchyard, but was driven back. The attack north of the road could not break the Confederate line. Wilcox described the action as "a bloody repulse to the enemy, rendering entirely useless to him his little success of the morning at Fredericksburg." Hooker expressed his disappointment in Sedgwick: "my object in ordering General Sedgwick forward ... Was to relieve me from the position in which I found myself at Chancellorsville. ... In my judgment General Sedgwick did not obey the spirit of my order, and made no sufficient effort to obey it. ... When he did move it was not with sufficient confidence or ability on his part to manoeuvre his troops."

The fighting on May 3, 1863, was some of the most furious anywhere in the civil war. The loss of 21,357 men that day in the three battles, divided equally between the two armies, ranks the fighting only behind the

By midmorning, two Union attacks against the infamous stone wall on Marye's Heights were repulsed with numerous casualties. A Union party under flag of truce was allowed to approach ostensibly to collect the wounded, but while close to the stone wall, they were able to observe how sparsely the Confederate line was manned. A third Union attack was successful in overrunning the Confederate position. Early was able to organize an effective fighting retreat.Krick, pp. 176–80; Welcher, pp. 680–81; Esposito, text for maps 88–89; Sears, pp. 352–56.

John Sedgwick's road to Chancellorsville was open, but he wasted time in gathering his troops and forming a marching column. His men, led by Brooks's division, followed by Newton and Howe, were delayed for several hours by successive actions against the Alabama brigade of Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox. His final delaying line was a ridge at Salem church, where he was joined by three brigades from McLaws's division and one from Anderson's, bringing the total Confederate strength to about 10,000 men.

Artillery fire was exchanged by both sides in the afternoon and at 5:30 p.m., two brigades of Brooks's division attacked on both sides of the Plank Road. The advance south of the road reached as far as the churchyard, but was driven back. The attack north of the road could not break the Confederate line. Wilcox described the action as "a bloody repulse to the enemy, rendering entirely useless to him his little success of the morning at Fredericksburg." Hooker expressed his disappointment in Sedgwick: "my object in ordering General Sedgwick forward ... Was to relieve me from the position in which I found myself at Chancellorsville. ... In my judgment General Sedgwick did not obey the spirit of my order, and made no sufficient effort to obey it. ... When he did move it was not with sufficient confidence or ability on his part to manoeuvre his troops."

The fighting on May 3, 1863, was some of the most furious anywhere in the civil war. The loss of 21,357 men that day in the three battles, divided equally between the two armies, ranks the fighting only behind the

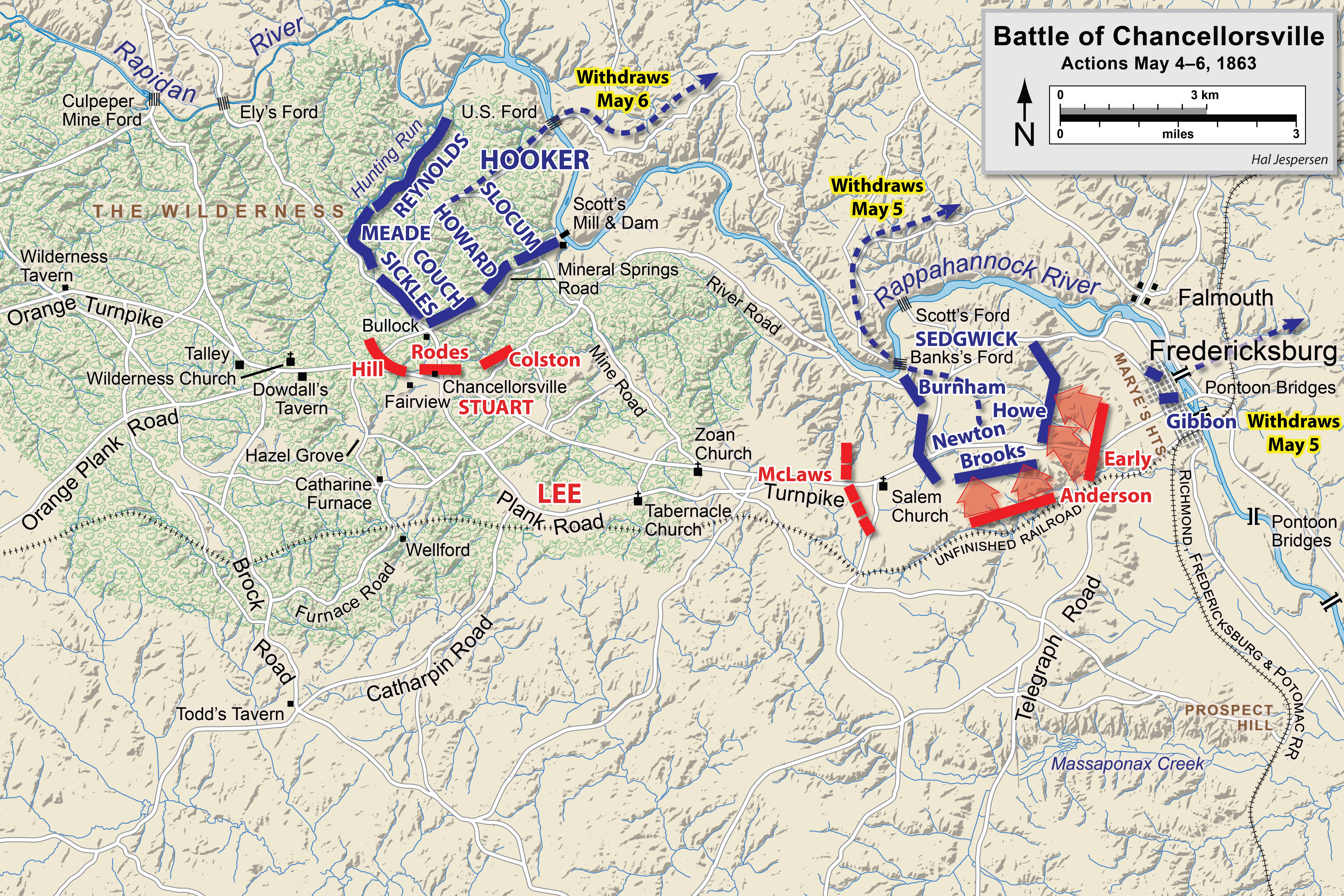

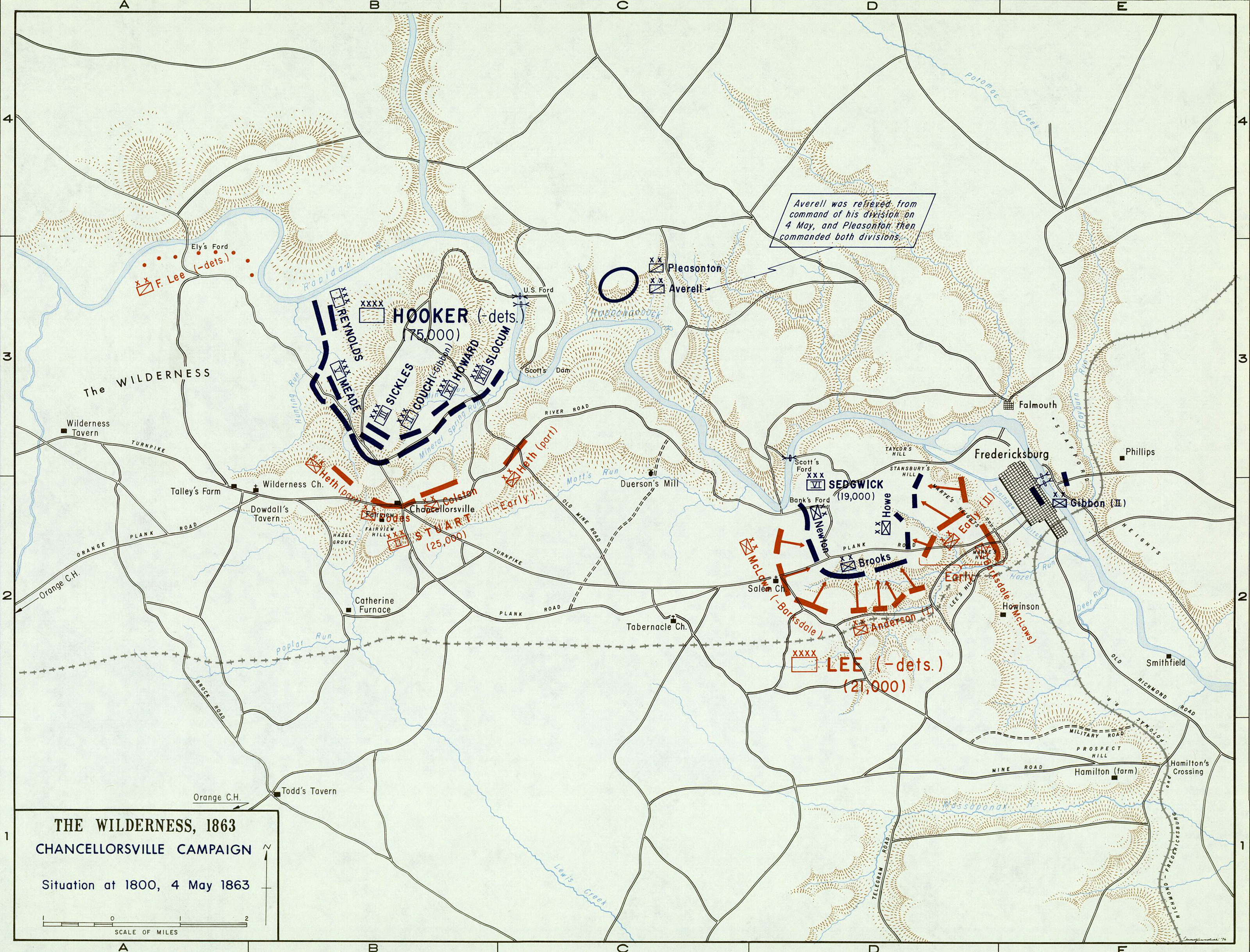

On the evening of May 3 and all day May 4, Hooker remained in his defenses north of Chancellorsville. Lee observed that Hooker was threatening no offensive action, so felt comfortable ordering Anderson's division to join the battle against Sedgwick. He sent orders to Early and McLaws to cooperate in a joint attack, but the orders reached his subordinates after dark, so the attack was planned for May 4.Sears, pp. 390–93; Welcher, pp. 681–82; Cullen, p. 44.

By this time Sedgwick had placed his divisions into a strong defensive position with its flanks anchored on the Rappahannock, three sides of a rectangle extending south of the Plank Road. Early's plan was to drive the Union troops off Marye's Heights and the other high ground west of Fredericksburg. Lee ordered McLaws to engage from the west "to prevent

On the evening of May 3 and all day May 4, Hooker remained in his defenses north of Chancellorsville. Lee observed that Hooker was threatening no offensive action, so felt comfortable ordering Anderson's division to join the battle against Sedgwick. He sent orders to Early and McLaws to cooperate in a joint attack, but the orders reached his subordinates after dark, so the attack was planned for May 4.Sears, pp. 390–93; Welcher, pp. 681–82; Cullen, p. 44.

By this time Sedgwick had placed his divisions into a strong defensive position with its flanks anchored on the Rappahannock, three sides of a rectangle extending south of the Plank Road. Early's plan was to drive the Union troops off Marye's Heights and the other high ground west of Fredericksburg. Lee ordered McLaws to engage from the west "to prevent  It was a difficult operation. Hooker and the artillery crossed first, followed by the infantry beginning at 6 a.m. on May 6. Meade's V Corps served as the rear guard. Rains caused the river to rise and threatened to break the pontoon bridges.

Couch was in command on the south bank after Hooker departed, but he was left with explicit orders not to continue the battle, which he had been tempted to do. The surprise withdrawal frustrated Lee's plan for one final attack against Chancellorsville. He had issued orders for his artillery to bombard the Union line in preparation for another assault, but by the time they were ready Hooker and his men were gone.

The Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. George Stoneman, after a week of ineffectual raiding in central and southern Virginia in which they failed to attack any of the objectives Hooker established, withdrew into Union lines east of Richmond—the peninsula north of the York River, across from Yorktown—on May 7, ending the campaign.

It was a difficult operation. Hooker and the artillery crossed first, followed by the infantry beginning at 6 a.m. on May 6. Meade's V Corps served as the rear guard. Rains caused the river to rise and threatened to break the pontoon bridges.

Couch was in command on the south bank after Hooker departed, but he was left with explicit orders not to continue the battle, which he had been tempted to do. The surprise withdrawal frustrated Lee's plan for one final attack against Chancellorsville. He had issued orders for his artillery to bombard the Union line in preparation for another assault, but by the time they were ready Hooker and his men were gone.

The Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. George Stoneman, after a week of ineffectual raiding in central and southern Virginia in which they failed to attack any of the objectives Hooker established, withdrew into Union lines east of Richmond—the peninsula north of the York River, across from Yorktown—on May 7, ending the campaign.

File:CH00 Battle of Chancellorsville (Map symbols).jpg, Map symbols

File:CH01 Hooker's Flanking March.jpg, Map 1:

Hooker's Flanking March, 27–30 April 1863 File:CH02 Battle of Chancellorsville 1 May 1863.jpg, Map 2:

1 May 1863 (late morning) File:CH03 Battle of Chancellorsville 2 May 1863.jpg, Map 3:

2 May 1863 (early evening) File:CH04 Battle of Chancellorsville 3 May 1863.jpg, Map 4:

3 May 1863 (early morning) File:CH05 Battle of Chancellorsville 4 May 1863.jpg, Map 5:

4 May 1863 (late afternoon)

West Point website

* Fishel, Edwin C. ''The Secret War for the Union: The Untold Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War''. Boston: Mariner Books (Houghton Mifflin Co.), 1996. . * Foote, Shelby. '' The Civil War: A Narrative''. Vol. 2, ''Fredericksburg to Meridian''. New York: Random House, 1958. . * Freeman, Douglas S. ''Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command''. 3 vols. New York: Scribner, 1946. . * Furgurson, Ernest B. ''Chancellorsville 1863: The Souls of the Brave''. New York: Knopf, 1992. . * Gallagher, Gary W. ''The Battle of Chancellorsville''. National Park Service Civil War series. Conshohocken, PA: U.S. National Park Service and Eastern National, 1995. . * Goolrick, William K., and the Editors of Time-Life Books. ''Rebels Resurgent: Fredericksburg to Chancellorsville''. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1985. . * Hebert, Walter H. ''Fighting Joe Hooker''. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999. . * Krick, Robert K

''Chancellorsville—Lee's Greatest Victory''

New York: American Heritage Publishing Co., 1990. . * Livermore, Thomas L. ''Numbers and Losses in the Civil War in America 1861–65''. Reprinted with errata, Dayton, OH: Morninside House, 1986. . First published in 1901 by Houghton Mifflin. * McGowen, Stanley S. "Battle of Chancellorsville." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. . * McPherson, James M. '' Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era''. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. . * Salmon, John S. ''The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide''. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2001. . * Sears, Stephen W. ''Chancellorsville''. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1996. . * Smith, Derek. ''The Gallant Dead: Union & Confederate Generals Killed in the Civil War''. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2005. . * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. . * Wineman, Bradford Alexander.

The Chancellorsville Campaign, January–May 1863

''. Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History, 2013. OCLC: 847739804.

CWSAC Report Update

''The Campaign of Chancellorsville, a Strategic and Tactical Study''

New Haven: Yale University Press, 1910. . * Crane, Stephen. '' The Red Badge of Courage''. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1895. . * Dodge, Theodore A

''The Campaign of Chancellorsville''

Boston: J. R. Osgood & Co., 1881. . * Evans, Clement A., ed

''Confederate Military History: A Library of Confederate States History''

12 vols. Atlanta: Confederate Publishing Company, 1899. . * Tidball, John C. The Artillery Service in the War of the Rebellion, 1861–1865. Westholme Publishing, 2011. . * U.S. War Department

''a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies''. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

''Chancellorsville Staff Ride: Briefing Book''

Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History, 2002. . * Mackowski, Chris, and Kristopher D. White. ''Chancellorsville's Forgotten Front: The Battles of Second Fredericksburg and Salem Church, May 3, 1863''. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2013. . * Mackowski, Chris, and Kristopher D. White. ''The Last Days of Stonewall Jackson: The Mortal Wounding of the Confederacy's Greatest Icon''. Emerging Civil War Series. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2013. . * Mackowski, Chris, and Kristopher D. White. ''That Furious Struggle: Chancellorsville and the High Tide of the Confederacy, May 1–4, 1863''. Emerging Civil War Series. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2014. . * Parsons, Philip W. ''The Union Sixth Army Corps in the Chancellorsville Campaign: A Study of the Engagements of Second Fredericksburg, Salem Church, and Banks's Ford''. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2006. . * Pula, James S. ''Under the Crescent Moon with the XI Corps in the Civil War''. Vol. 1, ''From the Defenses of Washington to Chancellorsville, 1862–1863''. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2017. .

The Battle of Chancellorsville

histories, photos, and preservation news ( Civil War Trust)

Battle of Chancellorsville Virtual TourChancellorsville Campaign in ''Encyclopedia Virginia''Second Battle of Fredericksburg in ''Encyclopedia Virginia''Animated Powerpoint slide presentation of campaignC-SPAN American History TV Tour of Jackson's Flank Attack at Chancellorsville

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Chancellorsville, Battle Of Conflicts in 1863 1863 in Virginia Chancellorsville Campaign Stonewall Jackson Battles of the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War Confederate victories of the American Civil War Spotsylvania County in the American Civil War Battles of the American Civil War in Virginia Conflict sites on the National Register of Historic Places in Virginia American Civil War on the National Register of Historic Places April 1863 events May 1863 events National Battlefields and Military Parks of the United States

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the

The Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, was a major battle of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

(1861–1865), and the principal engagement of the Chancellorsville campaign.

Chancellorsville is known as Lee's "perfect battle" because his risky decision to divide his army in the presence of a much larger enemy force resulted in a significant Confederate victory. The victory, a product of Lee's audacity and Hooker's timid decision-making, was tempered by heavy casualties, including Lt. Gen.

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star rank, three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in ...

Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson. Jackson was hit by friendly fire, requiring his left arm to be amputated. He died of pneumonia eight days later, a loss that Lee likened to losing his right arm.

The two armies faced off against each other at Fredericksburg during the winter of 1862–1863. The Chancellorsville campaign began when Hooker secretly moved the bulk of his army up the left bank of the Rappahannock River, then crossed it on the morning of April 27, 1863. Union cavalry under Maj. Gen. George Stoneman began a long-distance raid against Lee's supply lines at about the same time. This operation was completely ineffectual. Crossing the Rapidan River via Germanna and Ely's Fords, the Federal infantry concentrated near Chancellorsville on April 30. Combined with the Union force facing Fredericksburg, Hooker planned a double envelopment, attacking Lee from both his front and rear.

On May 1, Hooker advanced from Chancellorsville toward Lee, but the Confederate general split his army in the face of superior numbers, leaving a small force at Fredericksburg to deter Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick from advancing, while he attacked Hooker's advance with about four-fifths of his army. Despite the objections of his subordinates, Hooker withdrew his men to the defensive lines around Chancellorsville, ceding the initiative to Lee. On May 2, Lee divided his army again, sending Stonewall Jackson's entire corps on a flanking march that routed the Union XI Corps. While performing a personal reconnaissance in advance of his line, Jackson was wounded by fire after dark from his own men close between the lines, and cavalry commander Maj. Gen. J. E. B. Stuart

James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart (February 6, 1833May 12, 1864) was a United States Army officer from Virginia who became a Confederate States Army general during the American Civil War. He was known to his friends as "Jeb,” from the initials of ...

temporarily replaced him as corps commander.

The fiercest fighting of the battle—and the second bloodiest day of the Civil War—occurred on May 3 as Lee launched multiple attacks against the Union position at Chancellorsville, resulting in heavy losses on both sides and the pulling back of Hooker's main army. That same day, Sedgwick advanced across the Rappahannock River, defeated the small Confederate force at Marye's Heights in the Second Battle of Fredericksburg, and then moved to the west. The Confederates fought a successful delaying action at the Battle of Salem Church. On the 4th Lee turned his back on Hooker and attacked Sedgwick, and drove him back to Banks' Ford, surrounding them on three sides. Sedgwick withdrew across the ford early on May 5. Lee turned back to confront Hooker who withdrew the remainder of his army across U.S. Ford the night of May 5–6.

The campaign ended on May 7 when Stoneman's cavalry reached Union lines east of Richmond. Both armies resumed their previous position across the Rappahannock from each other at Fredericksburg. With the loss of Jackson, Lee reorganized his army, and flush with victory began what was to become the Gettysburg campaign a month later.

Background

Military situation

Union attempts against Richmond

In the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War, the objective of the Union had been to advance and seize the Confederate capital,Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

. In the first two years of the war, four major attempts had failed: the first foundered just miles away from Washington, D.C., at the First Battle of Bull Run (First Manassas) in July 1861. Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan's Peninsula Campaign took an amphibious approach, landing his Army of the Potomac on the Virginia Peninsula in the spring of 1862 and coming within of Richmond before being turned back by Gen. Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nort ...

in the Seven Days Battles.Kennedy, pp. 11–15, 88–112, 118–21, 144–49.

That summer, Maj. Gen. John Pope's Army of Virginia was defeated at the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

. Finally, in December 1862, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside's Army of the Potomac attempted to reach Richmond by way of Fredericksburg, Virginia

Fredericksburg is an independent city located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 27,982. The Bureau of Economic Analysis of the United States Department of Commerce combines the city of Fredericksburg wi ...

, but was defeated at the Battle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat, between the Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnsi ...

.

Shakeup in the Army of the Potomac

In January 1863, the Army of the Potomac, following theBattle of Fredericksburg

The Battle of Fredericksburg was fought December 11–15, 1862, in and around Fredericksburg, Virginia, in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. The combat, between the Union Army of the Potomac commanded by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnsi ...

and the humiliating Mud March, suffered from rising desertions and plunging morale. Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside decided to conduct a mass purge of the Army of the Potomac's leadership, eliminating a number of generals who he felt were responsible for the disaster at Fredericksburg. In reality, he had no power to dismiss anyone without the approval of Congress.Krick, pp. 14–15; Hebert, pp. 165–67, 177; Kennedy, p. 197; Eicher, p. 473; Sears, pp. 21–24, 61; Warner, p. 58.

Predictably, Burnside's purge went nowhere, and he offered President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

his resignation from command of the Army of the Potomac. He even offered to resign entirely from the Army, but the president persuaded him to stay, transferring him to the Western Theater, where he became commander of the Department of the Ohio. Burnside's former command, the IX Corps, was transferred to the Virginia Peninsula, a movement that prompted the Confederates to detach troops from Lee's army under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Horse". He served under Lee as a corps ...

, a decision that would be consequential in the upcoming campaign.

Abraham Lincoln had become convinced that the appropriate objective for his Eastern army was the army of Robert E. Lee, not any geographic features such as a capital city, but he and his generals knew that the most reliable way to bring Lee to a decisive battle was to threaten his capital. Lincoln tried a fifth time with a new general on January 25, 1863—Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, a man with a pugnacious reputation who had performed well in previous subordinate commands.

With Burnside's departure, Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin

William Buel Franklin (February 27, 1823March 8, 1903) was a career United States Army officer and a Union Army general in the American Civil War. He rose to the rank of a corps commander in the Army of the Potomac, fighting in several notable bat ...

left as well. Franklin had been a staunch supporter of George B. McClellan and refused to serve under Hooker, because he disliked him personally and also because he was senior to Hooker in rank. Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner

Edwin Vose Sumner (January 30, 1797March 21, 1863) was a career United States Army officer who became a Union Army general and the oldest field commander of any Army Corps on either side during the American Civil War. His nicknames "Bull" or "Bul ...

stepped down due to old age (he was 65) and poor health. He was reassigned to a command in Missouri, but died before he could assume it. Brig. Gen. Daniel Butterfield was reassigned from command of the V Corps to be Hooker's chief of staff.

Hooker embarked on a much-needed reorganization of the army, doing away with Burnside's grand division system, which had proved unwieldy; he also no longer had sufficient senior officers on hand that he could trust to command multi-corps operations. He organized the cavalry into a separate corps under the command of Brig. Gen. George Stoneman (who had commanded the III Corps at Fredericksburg). But while he concentrated the cavalry into a single organization, he dispersed his artillery battalions to the control of the infantry division commanders, removing the coordinating influence of the army's artillery chief, Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt

Henry Jackson Hunt (September 14, 1819 – February 11, 1889) was Chief of Artillery in the Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War. Considered by his contemporaries the greatest artillery tactician and strategist of the war, he was ...

.

Hooker established a reputation as an outstanding administrator and restored the morale of his soldiers, which had plummeted to a new low under Burnside. Among his changes were fixes to the daily diet of the troops, camp sanitary changes, improvements and accountability of the quartermaster system, addition of and monitoring of company cooks, several hospital reforms, an improved furlough system, orders to stem rising desertion, improved drills, and stronger officer training.

Intelligence and plans

Hooker took advantage of improved military intelligence about the positioning and capabilities of the opposing army, superior to that available to his predecessors in army command. His chief of staff, Butterfield, commissioned Col.George H. Sharpe

George Henry Sharpe (February 26, 1828 – January 13, 1900) was an American lawyer, soldier, United States Secret Service, Secret Service officer, diplomat, politician, and Member of the Board of General Appraisers.

Sharpe was born in 1828, in ...

from the 120th New York Infantry to organize a new Bureau of Military Information in the Army of the Potomac, part of the provost marshal

Provost marshal is a title given to a person in charge of a group of Military Police (MP). The title originated with an older term for MPs, '' provosts'', from the Old French ''prévost'' (Modern French ''prévôt''). While a provost marshal i ...

function under Brig. Gen. Marsena R. Patrick

Marsena Rudolph Patrick (March 15, 1811 – July 27, 1888) was a college president and an officer in the United States Army, serving as a general in the Union Army, Union volunteer forces during the American Civil War. He was the provost marshal fo ...

. Previously, intelligence gatherers, such as Allan Pinkerton and his detective agency, gathered information only by interrogating prisoners, deserters, "contrabands" (slaves), and refugees.Krick, p. 41; Sears, pp. 68–70, 100–102; Fishel, pp. 286–95. The Army of the Potomac was able to call on the services of self-styled "Professor of Aeronautics" Thaddeus S. C. Lowe and his two hydrogen aerostat

An aerostat (, via French) is a lighter-than-air aircraft that gains its lift through the use of a buoyant gas. Aerostats include unpowered balloons and powered airships. A balloon may be free-flying or tethered. The average density of the cra ...

s ''Washington'' and ''Eagle'', which regularly ascended to heights of or more to observe Lee's positions.

The new BMI added other sources including infantry and cavalry reconnaissance, spies, scouts, signal stations, and an aerial balloon corps. As he received the more complete information correlated from these additional sources, Hooker realized that if he were to avoid the bloodbath of direct frontal attacks, which were features of the battles of Antietam and, more recently, Fredericksburg, he could not succeed in his crossing of the Rappahannock "except by stratagem."

Hooker's army faced Lee across the Rappahannock from its winter quarters in Falmouth and around Fredericksburg. Hooker developed a strategy that was, on paper, superior to those of his predecessors. He planned to send his 10,000 cavalrymen under Maj. Gen. George Stoneman to cross the Rappahannock far upstream and raid deep into the Confederate rear areas, destroying crucial supply depots along the railroad from the Confederate capital in Richmond to Fredericksburg, which would cut Lee's lines of communication and supply.Gallagher, pp. 9–10; Eicher, p. 474; Cullen, pp. 17–18; Welcher, p. 659; Sears, pp. 120–24.

Hooker reasoned that Lee would react to this threat by abandoning his fortified positions on the Rappahannock and withdrawing toward his capital. At that time, Hooker's infantry would cross the Rappahannock in pursuit, attacking Lee when he was moving and vulnerable. Stoneman attempted to execute this turning movement on April 13, but heavy rains made the river crossing site at Sulphur Spring impassable. President Lincoln lamented, "I greatly fear it is another failure already." Hooker was forced to create a new plan for a meeting with Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and general in chief Henry W. Halleck in Aquia on April 19.

Hooker's second plan was to launch both his cavalry and infantry simultaneously in a bold double envelopment of Lee's army. Stoneman's cavalry would make a second attempt at its deep strategic raid, but at the same time, 42,000 men in three corps (V, XI, XII Corps) would stealthily march to cross the Rappahannock upriver at Kelly's Ford. They would then proceed south and cross the Rapidan at Germanna and Ely's Ford, concentrate at the Chancellorsville crossroads, and attack Lee's army from the west.Cullen, p. 17; Gallagher, pp. 10–11; Welcher, p. 659; Sears, pp. 137–38.

While they were under way, 10,000 men in two divisions from the II Corps would cross at the U.S. Ford and join with the V Corps in pushing the Confederates away from the river. The second half of the double envelopment was to come from the east: 40,000 men in two corps (I and VI Corps, under the overall command of John Sedgwick) would cross the Rappahannock below Fredericksburg and threaten to attack Stonewall Jackson's position on the Confederate right flank.

The remaining 25,000 men (III Corps and one division of the II Corps) would remain visible in their camps at Falmouth to divert Confederate attention from the turning movement. Hooker anticipated that Lee would either be forced to retreat, in which case he would be vigorously pursued, or he would be forced to attack the Union Army on unfavorable terrain.

One of the defining characteristics of the battlefield was a dense woodland south of the Rapidan known locally as the "Wilderness of Spotsylvania". The area had once been an open broadleaf forest, but during colonial times the trees were gradually cut down to make charcoal for local pig iron furnaces. When the supply of wood was exhausted, the furnaces were abandoned and secondary forest growth developed, creating a dense mass of brambles, thickets, vines, and low-lying vegetation.Sears, pp. 132, 193–94; Krick, pp. 35–36; Gallagher, pp. 11–13; Cullen, p. 19.

Hooker's army faced Lee across the Rappahannock from its winter quarters in Falmouth and around Fredericksburg. Hooker developed a strategy that was, on paper, superior to those of his predecessors. He planned to send his 10,000 cavalrymen under Maj. Gen. George Stoneman to cross the Rappahannock far upstream and raid deep into the Confederate rear areas, destroying crucial supply depots along the railroad from the Confederate capital in Richmond to Fredericksburg, which would cut Lee's lines of communication and supply.Gallagher, pp. 9–10; Eicher, p. 474; Cullen, pp. 17–18; Welcher, p. 659; Sears, pp. 120–24.

Hooker reasoned that Lee would react to this threat by abandoning his fortified positions on the Rappahannock and withdrawing toward his capital. At that time, Hooker's infantry would cross the Rappahannock in pursuit, attacking Lee when he was moving and vulnerable. Stoneman attempted to execute this turning movement on April 13, but heavy rains made the river crossing site at Sulphur Spring impassable. President Lincoln lamented, "I greatly fear it is another failure already." Hooker was forced to create a new plan for a meeting with Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and general in chief Henry W. Halleck in Aquia on April 19.

Hooker's second plan was to launch both his cavalry and infantry simultaneously in a bold double envelopment of Lee's army. Stoneman's cavalry would make a second attempt at its deep strategic raid, but at the same time, 42,000 men in three corps (V, XI, XII Corps) would stealthily march to cross the Rappahannock upriver at Kelly's Ford. They would then proceed south and cross the Rapidan at Germanna and Ely's Ford, concentrate at the Chancellorsville crossroads, and attack Lee's army from the west.Cullen, p. 17; Gallagher, pp. 10–11; Welcher, p. 659; Sears, pp. 137–38.

While they were under way, 10,000 men in two divisions from the II Corps would cross at the U.S. Ford and join with the V Corps in pushing the Confederates away from the river. The second half of the double envelopment was to come from the east: 40,000 men in two corps (I and VI Corps, under the overall command of John Sedgwick) would cross the Rappahannock below Fredericksburg and threaten to attack Stonewall Jackson's position on the Confederate right flank.

The remaining 25,000 men (III Corps and one division of the II Corps) would remain visible in their camps at Falmouth to divert Confederate attention from the turning movement. Hooker anticipated that Lee would either be forced to retreat, in which case he would be vigorously pursued, or he would be forced to attack the Union Army on unfavorable terrain.

One of the defining characteristics of the battlefield was a dense woodland south of the Rapidan known locally as the "Wilderness of Spotsylvania". The area had once been an open broadleaf forest, but during colonial times the trees were gradually cut down to make charcoal for local pig iron furnaces. When the supply of wood was exhausted, the furnaces were abandoned and secondary forest growth developed, creating a dense mass of brambles, thickets, vines, and low-lying vegetation.Sears, pp. 132, 193–94; Krick, pp. 35–36; Gallagher, pp. 11–13; Cullen, p. 19.

Catharine Furnace

Catharine Furnace is a historic blast furnace, iron furnace in Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park, near Chancellorsville, Virginia, Chancellorsville in Spotsylvania County, Virginia. It was built in 1837 and closed down ten year ...

, abandoned in the 1840s, had recently been reactivated to produce iron for the Confederate war effort. This area was largely unsuitable for the deployment of artillery and the control of large infantry formations, which would nullify some of the Union advantage in military power. It was important for Hooker's plan that his men move quickly out of this area and attack Lee in the open ground to the east. There were three primary roads available for this west-to-east movement: the Orange Plank Road, the Orange Turnpike, and the River Road.

The Confederate dispositions were as follows: the Rappahannock line at Fredericksburg was occupied by Longstreet's First Corps division of Lafayette McLaws on Marye's Heights, with Jackson's entire Second Corps to their right. Early's division was at Prospect Hill and the divisions of Rodes, Hill, and Colston extended the Confederate right flank along the river almost to Skinker's Neck. The other division present from Longstreet's Corps, Anderson's, guarded the river crossings on the left flank. Stuart's cavalry was largely in Culpeper County near Kelly's Ford, beyond the infantry's left flank.

Initial movements

April 27–30: Movement to battle

On April 27–28, the initial three corps of the Army of the Potomac began their march under the leadership of Slocum. They crossed the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers as planned and began to concentrate on April 30 around the hamlet of Chancellorsville, which was little more than a single large, brick mansion at the junction of the Orange Turnpike and Orange Plank Road. Built in the early 19th century, it had been used as an inn on the turnpike for many years, but now served as a home for the Frances Chancellor family. Some of the family remained in the house during the battle.Esposito, text for map 84; Gallagher, pp. 13–14; Salmon, p. 175; Sears, pp. 141–58; Krick, p. 32; Eicher, pp. 475, 477; Welcher, pp. 660–61.

Hooker arrived late in the afternoon on April 30 and made the mansion his headquarters. Stoneman's cavalry began on April 30 its second attempt to reach Lee's rear areas. Two divisions of II Corps crossed at U.S. Ford on April 30 without opposition. By dawn on April 29, pontoon bridges spanned the Rappahannock south of Fredericksburg and Sedgwick's force began to cross.

Pleased with the success of the operation so far, and realizing that the Confederates were not vigorously opposing the river crossings, Hooker ordered Sickles to begin the movement of the III Corps from Falmouth the night of April 30 – May 1. By May 1, Hooker had approximately 70,000 men concentrated in and around Chancellorsville.

On April 27–28, the initial three corps of the Army of the Potomac began their march under the leadership of Slocum. They crossed the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers as planned and began to concentrate on April 30 around the hamlet of Chancellorsville, which was little more than a single large, brick mansion at the junction of the Orange Turnpike and Orange Plank Road. Built in the early 19th century, it had been used as an inn on the turnpike for many years, but now served as a home for the Frances Chancellor family. Some of the family remained in the house during the battle.Esposito, text for map 84; Gallagher, pp. 13–14; Salmon, p. 175; Sears, pp. 141–58; Krick, p. 32; Eicher, pp. 475, 477; Welcher, pp. 660–61.

Hooker arrived late in the afternoon on April 30 and made the mansion his headquarters. Stoneman's cavalry began on April 30 its second attempt to reach Lee's rear areas. Two divisions of II Corps crossed at U.S. Ford on April 30 without opposition. By dawn on April 29, pontoon bridges spanned the Rappahannock south of Fredericksburg and Sedgwick's force began to cross.

Pleased with the success of the operation so far, and realizing that the Confederates were not vigorously opposing the river crossings, Hooker ordered Sickles to begin the movement of the III Corps from Falmouth the night of April 30 – May 1. By May 1, Hooker had approximately 70,000 men concentrated in and around Chancellorsville.

In his Fredericksburg headquarters, Lee was initially in the dark about the Union intentions and he suspected that the main column under Slocum was heading towards Gordonsville. Jeb Stuart's cavalry was cut off at first by Stoneman's departure on April 30, but they were soon able to move freely around the army's flanks on their reconnaissance missions after almost all their Union counterparts had left the area.Salmon, pp. 176–77; Gallagher, pp. 16–17; Krick, pp. 39; Salmon, pp. 176–77; Cullen, pp. 21–22; Sears, pp. 187–89.

As Stuart's intelligence information about the Union river crossings began to arrive, Lee did not react as Hooker had anticipated. He decided to violate one of the generally accepted principles of war and divide his force in the face of a superior enemy, hoping that aggressive action would allow him to attack and defeat a portion of Hooker's army before it could be fully concentrated against him. He became convinced that Sedgwick's force would demonstrate against him, but not become a serious threat, so he ordered about 4/5 of his army to meet the challenge from Chancellorsville. He left behind a brigade under Brig. Gen. William Barksdale on heavily fortified Marye's Heights behind Fredericksburg and one division under Maj. Gen.

In his Fredericksburg headquarters, Lee was initially in the dark about the Union intentions and he suspected that the main column under Slocum was heading towards Gordonsville. Jeb Stuart's cavalry was cut off at first by Stoneman's departure on April 30, but they were soon able to move freely around the army's flanks on their reconnaissance missions after almost all their Union counterparts had left the area.Salmon, pp. 176–77; Gallagher, pp. 16–17; Krick, pp. 39; Salmon, pp. 176–77; Cullen, pp. 21–22; Sears, pp. 187–89.

As Stuart's intelligence information about the Union river crossings began to arrive, Lee did not react as Hooker had anticipated. He decided to violate one of the generally accepted principles of war and divide his force in the face of a superior enemy, hoping that aggressive action would allow him to attack and defeat a portion of Hooker's army before it could be fully concentrated against him. He became convinced that Sedgwick's force would demonstrate against him, but not become a serious threat, so he ordered about 4/5 of his army to meet the challenge from Chancellorsville. He left behind a brigade under Brig. Gen. William Barksdale on heavily fortified Marye's Heights behind Fredericksburg and one division under Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was a Virginia lawyer and politician who became a Confederate States of America, Confederate general during the American Civil War. Trained at the United States Military Academy, Early r ...

, on Prospect Hill south of the town.

These roughly 11,000 men and 56 guns would attempt to resist any advance by Sedgwick's 40,000. He ordered Stonewall Jackson to march west and link up with Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson's division, which had pulled back from the river crossings they were guarding and began digging earthworks on a north-south line between the Zoan and Tabernacle churches. McLaws's division was ordered from Fredericksburg to join Anderson. This would amass 40,000 men to confront Hooker's movement east from Chancellorsville. Heavy fog along the Rappahannock masked some of these westward movements and Sedgwick chose to wait until he could determine the enemy's intentions.

Opposing forces

Union

The Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, had 133,868 men and 413 guns organized as follows: * I Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen.John F. Reynolds

John Fulton Reynolds (September 21, 1820 – July 1, 1863)Eicher, pp. 450-51. was a career United States Army officer and a general in the American Civil War. One of the Union Army's most respected senior commanders, he played a key role in commi ...

, with the divisions of Brig. Gens. James S. Wadsworth, John C. Robinson

John Cleveland Robinson (April 10, 1817 – February 18, 1897) had a long and distinguished career in the United States Army, fighting in numerous wars and culminating his career as a Union Army brigadier general of volunteers and brevet major ...

, and Abner Doubleday.

* II Corps 2nd Corps, Second Corps, or II Corps may refer to:

France

* 2nd Army Corps (France)

* II Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* II Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French ...

, commanded by Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch

Darius Nash Couch (July 23, 1822 – February 12, 1897) was an American soldier, businessman, and naturalist. He served as a career U.S. Army officer during the Mexican–American War, the Second Seminole War, and as a general officer in the Uni ...

, with the divisions of Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock and William H. French

William Henry French (January 13, 1815 – May 20, 1881) was a career United States Army officer and a Union Army General officer, General in the American Civil War. He rose to temporarily command a corps within the Army of the Potomac, but was re ...

, and Brig. Gen. John Gibbon.

* III Corps 3rd Corps, Third Corps, III Corps, or 3rd Army Corps may refer to:

France

* 3rd Army Corps (France)

* III Cavalry Corps (Grande Armée), a cavalry unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

* III Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of th ...

, commanded by Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles

Daniel Edgar Sickles (October 20, 1819May 3, 1914) was an American politician, soldier, and diplomat.

Born to a wealthy family in New York City, Sickles was involved in a number of scandals, most notably the 1859 homicide of his wife's lover, U. ...

, with the divisions of Brig. Gen. David B. Birney, and Maj. Gens. Hiram G. Berry

Hiram Gregory Berry (August 27, 1824 – May 3, 1863) was an American politician and general in the Army of the Potomac during the American Civil War.

Birth and early years

Hiram Gregory Berry was born on August 27, 1824 on his parents' farm in t ...

and Amiel W. Whipple

Amiel Weeks Whipple (October 21, 1817 – May 7, 1863)Anderson, TSHA was an American military officer and topographical engineer. He served as a brigadier general in the American Civil War, where he was mortally wounded at the Battle of Chance ...

.

* V Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, with the divisions of Brig. Gens. Charles Griffin and Andrew A. Humphreys

Andrew Atkinson Humphreys (November 2, 1810December 27, 1883), was a career United States Army officer, civil engineer, and a Union General in the American Civil War. He served in senior positions in the Army of the Potomac, including division c ...

, and Maj. Gen. George Sykes.

* VI Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, with the divisions of Brig. Gens. William T. H. Brooks

William Thomas Harbaugh Brooks (January 28, 1821 – July 19, 1870) was a career military officer in the United States Army, serving as a major general during the American Civil War.

Early life

Brooks was born in New Lisbon (now Lisbon), Ohio ...

and Albion P. Howe

Albion Parris Howe (March 13, 1818 – January 25, 1897) was an American officer who served as a Union general in the American Civil War. Howe's contentious relationships with superior officers in the Army of the Potomac eventually led to his bei ...

, Maj. Gen. John Newton, and Col. Hiram Burnham.

* XI Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard

Oliver Otis Howard (November 8, 1830 – October 26, 1909) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the Civil War. As a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac, Howard lost his right arm while leading his men against ...

, with the divisions of Brig. Gen. Charles Devens, Jr., and Adolph von Steinwehr, and Maj. Gen. Carl Schurz

Carl Schurz (; March 2, 1829 – May 14, 1906) was a German revolutionary and an American statesman, journalist, and reformer. He immigrated to the United States after the German revolutions of 1848–1849 and became a prominent member of the new ...

.

* XII Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum

Henry Warner Slocum, Sr. (September 24, 1827 – April 14, 1894), was a Union general during the American Civil War and later served in the United States House of Representatives from New York. During the war, he was one of the youngest major ge ...

, with the divisions of Brig. Gens. Alpheus S. Williams and John W. Geary

John White Geary (December 30, 1819February 8, 1873) was an American lawyer, politician, Freemason, and a Union general in the American Civil War. He was the final alcalde and first mayor of San Francisco, a governor of the Kansas Territory, and ...

.

* Cavalry Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. George Stoneman, with the divisions of Brig. Gens. Alfred Pleasonton, William W. Averell

William Woods Averell (November 5, 1832 – February 3, 1900) was a career United States Army officer and a cavalry general in the American Civil War. He was the only Union general to achieve a major victory against the Confederates in the V ...

, and David M. Gregg

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

.

Confederate

Gen.Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nort ...

's Army of Northern Virginia fielded 60,298 men and 220 guns, organized as follows:

* First Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet

James Longstreet (January 8, 1821January 2, 1904) was one of the foremost Confederate generals of the American Civil War and the principal subordinate to General Robert E. Lee, who called him his "Old War Horse". He served under Lee as a corps ...

. Longstreet and the majority of his corps (the divisions of Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood and Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett, and two artillery battalions) were detached for duty in southeastern Virginia. The divisions present at Chancellorsville were those of Maj. Gens. Lafayette McLaws

Lafayette McLaws ( ; January 15, 1821 – July 24, 1897) was a United States Army officer and a Confederate general in the American Civil War. He served at Antietam and Fredericksburg, where Robert E. Lee praised his defense of Marye's Heights, ...

and Richard H. Anderson.

* Second Corps, commanded by Lt. Gen. Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

, with the divisions of Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill, Brig. Gen. Robert E. Rodes, Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early

Jubal Anderson Early (November 3, 1816 – March 2, 1894) was a Virginia lawyer and politician who became a Confederate States of America, Confederate general during the American Civil War. Trained at the United States Military Academy, Early r ...

, and Brig. Gen. Raleigh E. Colston.

* Cavalry Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. (Stuart's corps had only two brigades at Chancellorsville, those of Brig. Gens. Fitzhugh Lee and W.H.F. "Rooney" Lee. The brigades of Brig. Gens. Wade Hampton and William E. "Grumble" Jones were detached.)

The Chancellorsville campaign was one of the most lopsided clashes of the war, with the Union's effective fighting force more than twice the Confederates', the greatest imbalance during the war in Virginia. Hooker's army was much better supplied and was well-rested after several months of inactivity. Lee's forces, on the other hand, were poorly provisioned and were scattered all over the state of Virginia. Some 15,000 men of Longstreet's Corps had previously been detached and stationed near Norfolk in order to block a potential threat to Richmond from Federal troops stationed at Fort Monroe and Newport News on the Peninsula, as well as at Norfolk and Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include Lowes ...

.Salmon, pp. 168–72; Kennedy, pp. 194–97; Eicher, p. 474; Cullen, p. 16; Sears, pp. 94–95.

In light of the continued Federal inactivity, by late March Longstreet's primary assignment became that of requisitioning provisions for Lee's forces from the farmers and planters of North Carolina and Virginia. As a result of this the two divisions of Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood and Maj. Gen. George Pickett were away from Lee's army and would take a week or more of marching to reach it in an emergency. After nearly a year of campaigning, allowing these troops to slip away from his immediate control was Lee's gravest miscalculation. Although he hoped to be able to call on them, these men would not arrive in time to aid his outnumbered forces.