Battle Of Buffington Island on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of

The

The

On the foggy morning of July 19, a Federal

On the foggy morning of July 19, a Federal

Buffington Island Battlefield Preservation Foundation

Recently 117 acres have been saved by the efforts of th

American Battlefield Trust

* Cahill, Lora Schmidt and Mowery, David L., ''Morgan's Raid Across Ohio: The Civil War Guidebook of the John Hunt Morgan Heritage Trail.'' Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio Historical Society, 2014. . * Duke, Basil Wilson, ''A History of Morgan's Cavalry.'' Cincinnati, Ohio: Miami Printing and Pub. Co., 1867

On-line version

* Horwitz, Lester V., ''The Longest Raid of the Civil War.'' Cincinnati, Ohio: Farmcourt Publishing, Inc., 1999. . * Mowery, David L., ''Morgan's Great Raid: The Remarkable Expedition from Kentucky to Ohio.'' Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2013. .

Buffington Island Battlefield Preservation FoundationBuffington Island Battlefield Memorial Park

- Ohio History Connection

Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation’s Civil War Battlefields

rchivedbr>The Fight to Save Buffington Island Battlefield

rchivedbr>Buffington Island Battlefield Archaeological Project

- Heidelberg University rchived {{authority control National Register of Historic Places in Meigs County, Ohio Geography of Meigs County, Ohio Ohio History Connection Jackson County, West Virginia Meigs County, Ohio Buffington Morgan's Raid

Buffington Island

Buffington Island is an island in the Ohio River in Jackson County, West Virginia near the town of Ravenswood, United States, east of Racine, Ohio. During the American Civil War, the Battle of Buffington Island took place on July 19, 1863, just ...

, also known as the St. Georges Creek Skirmish, was an American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

engagement in Meigs County, Ohio

Meigs County ( ) is a county located in the U.S. state of Ohio. As of the 2020 census, the population was 22,210. Its county seat is Pomeroy. The county is named for Return J. Meigs Jr., the fourth Governor of Ohio.

Geography

According to t ...

, and Jackson County, West Virginia, on July 19, 1863, during Morgan's Raid

Morgan's Raid was a diversionary incursion by Confederate cavalry into the Union states of Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia during the American Civil War. The raid took place from June 11 to July 26, 1863, and is named for the commander ...

. The largest battle in Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

during the war, Buffington Island contributed to the capture of the famed Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

raider, Brig. Gen.

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

John H. Morgan, who was seeking to escape Union army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

pursuers across the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

at a ford opposite Buffington Island.

Delayed overnight, Morgan was almost surrounded by Union cavalry the next day, and the resulting battle ended in a Confederate rout, with over half of the 1,930-man Confederate force being captured. General Morgan and some 700 men escaped, but the daring raid finally ended on July 26 with his surrender after the Battle of Salineville

The Battle of Salineville occurred July 26, 1863, near Salineville, Ohio, during Morgan's Raid in the American Civil War. It was the northernmost military action involving an official command of the Confederate States Army. The Union victory sha ...

. Morgan's Raid was of little military consequence, but it did spread terror among much of the population of southern and eastern Ohio, as well as neighboring Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

.

Background

Hoping to divert the attention of the FederalArmy of the Ohio

The Army of the Ohio was the name of two Union armies in the American Civil War. The first army became the Army of the Cumberland and the second army was created in 1863.

History

1st Army of the Ohio

General Orders No. 97 appointed Maj. Gen. Do ...

from Southern forces in Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

, Brig. Gen. John H. Morgan and 2,460 Confederate cavalrymen, along with a battery of horse artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

, rode west from Sparta, Tennessee

Sparta is a city in and the county seat of White County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 5,001 in 2020.U.S. Census we ...

, on June 11, 1863. Twelve days later, when a second Federal army (the Army of the Cumberland

The Army of the Cumberland was one of the principal Union armies in the Western Theater during the American Civil War. It was originally known as the Army of the Ohio.

History

The origin of the Army of the Cumberland dates back to the creation ...

) began its Tullahoma Campaign, Morgan decided it was time to move northward. His column marched into Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, fighting a series of minor battles, before commandeering two steamships to ferry them across the Ohio River into Indiana (against orders), where, at the Battle of Corydon, Morgan routed the local militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

. With his path now relatively clear, Morgan headed eastward on July 13 past Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

and rode across southern Ohio, stealing horses and supplies along the way.

The Union response was not long in coming, as Maj. Gen.

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Ambrose Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three times Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor ...

, commanding the Department of the Ohio

The Department of the Ohio was an administrative military district created by the United States War Department early in the American Civil War to administer the troops in the Northern states near the Ohio River.

1st Department 1861–1862

Gener ...

, ordered out all available troops, as well as sending several Union Navy

), (official)

, colors = Blue and gold

, colors_label = Colors

, march =

, mascot =

, equipment =

, equipment_label ...

gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

s steaming up the Ohio River to contest any Confederate attempt to reach Kentucky or West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

and safety. Brig. Gen. Edward H. Hobson led several columns of Federal cavalry in pursuit of Morgan's raiders, which by now had been reduced to some 1,930 men. Ohio Governor David Tod

David Tod (February 21, 1805 – November 13, 1868) was an American politician and industrialist from the U.S. state of Ohio. As the 25th governor of Ohio, Tod gained recognition for his forceful and energetic leadership during the American Civi ...

called out the local militia, and volunteers formed companies to protect towns and river crossings throughout the region.

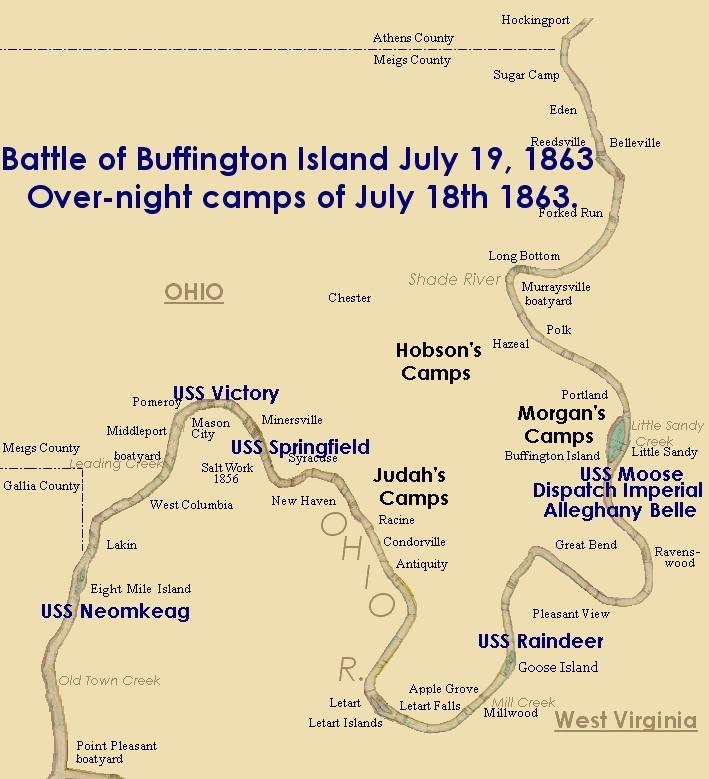

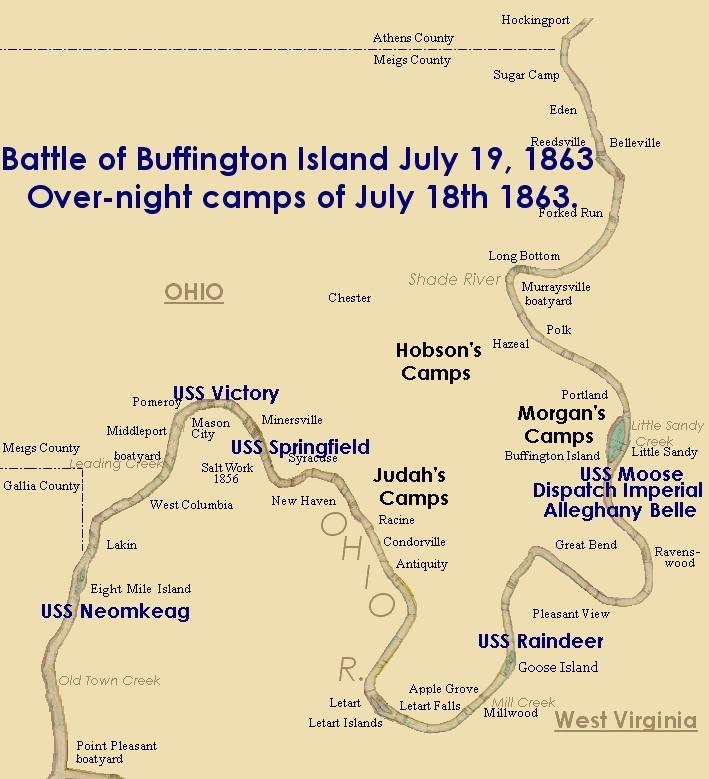

On July 18, Morgan, having split his column earlier, led his reunited force towards Middleport, Ohio

Middleport is a village in Meigs County, Ohio, along the Ohio River. The population was 2,530 at the time of the 2010 census.

History

Middleport was founded during the 1820s, a time of great prosperity and rapidly increasing commerce in Meigs Co ...

, a quiet river town near the Eight Mile Island Ford, where Morgan intended to cross into West Virginia. Running a gauntlet of small arms fire, Morgan's men were denied access to the river and to Middleport itself (which had a ferry), and he headed towards the next ford upstream at Buffington Island

Buffington Island is an island in the Ohio River in Jackson County, West Virginia near the town of Ravenswood, United States, east of Racine, Ohio. During the American Civil War, the Battle of Buffington Island took place on July 19, 1863, just ...

, some 20 miles to the southeast.

Arriving near Buffington Island and the nearby tiny hamlet of Portland, Ohio, towards evening on July 18, Morgan found that the ford was blocked by several hundred local militia ensconced behind hastily constructed earthworks. As a dense fog and darkness settled in, Morgan decided to camp for the night to allow his jaded men and horses to rest. He was concerned that even if he pushed aside the enemy troops, he might lose additional men in the darkness as they tried to navigate the narrow ford. The delay proved to be a fatal mistake.

Fitch's Fleet

The

The US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage of ...

's Mississippi Squadron

Squadron may refer to:

* Squadron (army), a military unit of cavalry, tanks, or equivalent subdivided into troops or tank companies

* Squadron (aviation), a military unit that consists of three or four flights with a total of 12 to 24 aircraft, ...

was involved in Battle of Buffington Island. Morgan had brought field cannons with his column. A heavy river blockade and a means was realized early in the chase while Morgan's column traveled easterly towards Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

. Lt Commander Leroy Fitch's fleet

Fleet may refer to:

Vehicles

*Fishing fleet

*Naval fleet

*Fleet vehicles, a pool of motor vehicles

*Fleet Aircraft, the aircraft manufacturing company

Places

Canada

* Fleet, Alberta, Canada, a hamlet

England

* The Fleet Lagoon, at Chesil Beach ...

included the '' Brilliant'', ''Fairplay

FairPlay is a digital rights management (DRM) technology developed by Apple Inc. It is built into the MP4 multimedia file format as an encrypted AAC audio layer, and was used until April 2009 by the company to protect copyrighted works sold ...

'', ''Moose

The moose (in North America) or elk (in Eurasia) (''Alces alces'') is a member of the New World deer subfamily and is the only species in the genus ''Alces''. It is the largest and heaviest extant species in the deer family. Most adult ma ...

'', ''Reindeer

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subspe ...

'', '' St. Clair'', ''Silver Lake

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

'', '' Springfield'', ''Victory

The term victory (from Latin ''victoria'') originally applied to warfare, and denotes success achieved in personal Duel, combat, after military operations in general or, by extension, in any competition. Success in a military campaign constitu ...

'', ''Naumkeag

Naumkeag is the former country estate of noted New York City lawyer Joseph Hodges Choate and Caroline Dutcher Sterling Choate, located at 5 Prospect Hill Road, Stockbridge, Massachusetts. The estate's centerpiece is a 44-room, Shingle Style ...

'', and '' Queen City'', which were tinclads and gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

s. A few of these steamers lagged behind to zone-up protecting against a possible doubling back of Morgan's column. The forward vessels were each assigned a patrol zone along the Mason, Jackson and Wood counties of West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the Bur ...

by Fitch's instruction. ''Naumkeag'' patrolled from Point Pleasant, West Virginia

Point Pleasant is a city in and the county seat of Mason County, West Virginia, United States, at the confluence of the Ohio and Kanawha Rivers. The population was 4,101 at the 2020 census. It is the principal city of the Point Pleasant, ...

to Eight Mile Island zone and ''Springfield'' guarded from Pomeroy, Ohio

Pomeroy ( ) is a village in and the county seat of Meigs County, Ohio, United States, along the Ohio River 21 miles south of Athens. The population was 1,852 at the 2010 census.

History

Pomeroy was founded in 1804 and named for landowner Samuel ...

towards Letart Islands. ''Victorys cannon balls have been found along Leading Creek, Ohio, its patrol from Middleport, Ohio

Middleport is a village in Meigs County, Ohio, along the Ohio River. The population was 2,530 at the time of the 2010 census.

History

Middleport was founded during the 1820s, a time of great prosperity and rapidly increasing commerce in Meigs Co ...

to Eight Mile Island along the West Virginia river bank. The ''Magnolia'', ''Imperial'', ''Alleghany Belle'', and ''Union'' tinclads and armed packets which were privateers

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

along with others documented under Parkersburg

Parkersburg is a city in and the county seat of Wood County, West Virginia. Located at the confluence of the Ohio and Little Kanawha rivers, it is the state's fourth-largest city and the largest city in the Parkersburg-Marietta-Vienna metro ...

Logistics' command. The Army's "amphibious division" officer, Major General Ambrose E. Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three times Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor ...

at his Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

headquarters, provided intelligence of Morgan's march and turned his flagship, ''Alleghany Belle'', over to Fitch before the battle. The " amphibious division

Division or divider may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

*Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division

Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting ...

" tinclads had four to six large jonboat

A jon boat (or johnboat) is a flat-bottomed boat constructed of aluminum, fiberglass, wood, or polyethelene with one, two, or three seats, usually bench type. They are suitable for fishing, hunting and cruising. The nearly flat hull of a jon bo ...

s (sideboats) used to fire rifles from, for landing to give chase and pickup prisoners.

Fitch's flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

was the gunboat USS ''Moose''. ''Moose'' and Fitch's dispatch privateer, ''Imperial'', were tied up within earshot of the island the night before the battle. It has been written that Fitch had the boilers fired up and shooting its large cannons at the island on first rifle fire, slightly out of range before steam could make way. ''Allegheny Belle'' was a little farther down tied up along the Ohio side. Having heard ''Moose''s cannons, it made steam and soon brought up Burnsides' "amphibious infantry" (M. F. Jenkins 1999).

Continuing upstream after the main battle dissolved into skirmishes, ''Moose'' fired on a Confederate artillery column trying to cross the river above the island at the next shoal crossing. Fitch dispatched ''Imperial'' to recover Confederate field artillery left behind there. All along the river, spotty gunboat and field cannon fire with clusters of rifle fire was heard shooting at Morgan's scouts looking for another possible ford. Meanwhile, Parkersburg

Parkersburg is a city in and the county seat of Wood County, West Virginia. Located at the confluence of the Ohio and Little Kanawha rivers, it is the state's fourth-largest city and the largest city in the Parkersburg-Marietta-Vienna metro ...

logistics terminal had sent a local armed packet with 9th Infantry sentries below Blennerhassett Island

Blennerhassett Island is an island on the Ohio River below the mouth of the Little Kanawha River, near Parkersburg in Wood County, West Virginia, United States.

Historically, Blennerhassett Island was occupied by Native Americans. Nemacolin, ...

on word of the Battle's gunfire some twenty miles below. These paralleled patrols opposite the Belpre, Ohio

Belpre (historically spelled Belpré; pronounced ) is a city in Washington County, Ohio, United States, along the Ohio River near Parkersburg, West Virginia. Its name derives from "Belle Prairie" (French for "beautiful meadow"), the name given ...

, Union Army encampment below the Ohio side of the terminal. This steamboat river harbor and large land debarkations camp blocked Morgan's further attempt to ford the river upstream turning his retreat northerly and away from this Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

area. The local support vessels were busy hauling ammunition

Ammunition (informally ammo) is the material fired, scattered, dropped, or detonated from any weapon or weapon system. Ammunition is both expendable weapons (e.g., bombs, missiles, grenades, land mines) and the component parts of other weap ...

, ration

Rationing is the controlled distribution of scarce resources, goods, services, or an artificial restriction of demand. Rationing controls the size of the ration, which is one's allowed portion of the resources being distributed on a particular ...

s and prisoners. Belpre, Ohio

Belpre (historically spelled Belpré; pronounced ) is a city in Washington County, Ohio, United States, along the Ohio River near Parkersburg, West Virginia. Its name derives from "Belle Prairie" (French for "beautiful meadow"), the name given ...

had a supply receiving dockage and depot.

Battle

On the foggy morning of July 19, a Federal

On the foggy morning of July 19, a Federal brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

Br ...

s under Henry M. Judah (1,100 men) finally caught up with Morgan and attacked his position on the broad flood plain just north of Portland, as another column under Edward Hobson (450 men) arrived on the scene. In the spirited early fighting, Maj. Maj may refer to:

* Major, a rank of commissioned officer in many military forces

* ''Máj'', a romantic Czech poem by Karel Hynek Mácha

* ''Máj'' (literary almanac), a Czech literary almanac published in 1858

* Marshall Islands International Ai ...

Daniel McCook

Daniel McCook (June 20, 1798 – July 21, 1863) was an attorney and an officer in the Union army during the American Civil War. He was one of two Ohio brothers who, along with 13 of their sons, became widely known as the “Fighting McCooks ...

, the 65-year-old patriarch of the famed Fighting McCooks

The Fighting McCooks were members of a family of Ohioans who reached prominence as officers in the Union Army during the American Civil War. Two brothers, Daniel and John McCook, and thirteen of their sons were involved in the army, making the fami ...

, was mortally wounded. In addition, two Union gunboats, the U.S.S. ''Moose'' and the ''Allegheny Belle'', steamed into the narrow channel separating Buffington Island from the flood plain and opened fire on Morgan's men, spraying them with shell fragments. Soon they were joined by a third gunboat. Also brought onto the field were 970 infantrymen under Eliakim Scammon

Eliakim Parker Scammon (December 27, 1816 – December 7, 1894) was a career officer in the United States Army, serving as a Brigadier general (United States), brigadier general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Early life and caree ...

, although this force was not actively engaged. Therefore only 1,550 Federals were engaged with Morgan's exhausted men.

Morgan, his way to the Buffington Island ford now totally blocked, left behind a small rear guard and tried to fight his way northward along the flood plain, hoping to reach yet another ford. It proved to be an exercise in futility, as Morgan's force was split apart by the converging Federal columns and 52 Confederates were killed, with well over one hundred badly wounded in the swirling fighting. Morgan and about 700 men escaped encirclement by following a narrow path through the woods. However, his brother-in-law and second-in-command, Col. Basil W. Duke

Basil Wilson Duke (May 28, 1838 – September 16, 1916) was a Confederate States Army, Confederate general officer during the American Civil War. His most noted service in the war was as second-in-command for his brother-in-law John Hunt Mo ...

, was captured, as were 71 of Morgan's cavalrymen, including his younger brother John Morgan. Duke formally surrendered to Col. Isaac Garrard of the 7th Ohio Cavalry

The 7th Ohio Cavalry Regiment was a regiment of Union cavalry raised in southern Ohio for service during the American Civil War. Nicknamed the "River Regiment" as its men came from nine counties along the Ohio River, it served in the Western The ...

.

Morgan's beleaguered troops soon headed upstream for the unguarded ford opposite Belleville, West Virginia, where over 300 men successfully crossed the Ohio River to avoid capture, most notably Col.

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Adam "Stovepipe" Johnson and famed telegrapher George Ellsworth

George A. Ellsworth (1843–1899), commonly known as "Lightning" Ellsworth, was a Canadian telegrapher who served in the cavalry forces of Brig. Gen. John Hunt Morgan in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. His use of the telegraph ...

. General Morgan, who was halfway across the ford, noted with dismay that his remaining men were trapped on the Ohio side as the Federal gunboats suddenly loomed into view. He wheeled his horse midchannel and rejoined what was left of his column on the Ohio riverbank. Over the next few days, they failed to find a secure place to cross the river, and Morgan's remaining force was captured on July 26 in northern Ohio following the Battle of Salineville

The Battle of Salineville occurred July 26, 1863, near Salineville, Ohio, during Morgan's Raid in the American Civil War. It was the northernmost military action involving an official command of the Confederate States Army. The Union victory sha ...

.

Many of those captured at Buffington Island were taken via steamboat to Cincinnati as prisoners of war, including most of the wounded. Morgan and most of his officers were confined to the Ohio Penitentiary

The Ohio Penitentiary, also known as the Ohio State Penitentiary, was a prison operated from 1834 to 1984 in downtown Columbus, Ohio, in what is now known as the Arena District. The state had built a small prison in Columbus in 1813, but as the ...

in Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

. Morgan, Thomas Hines, and a few others would later escape and return safely to Kentucky.

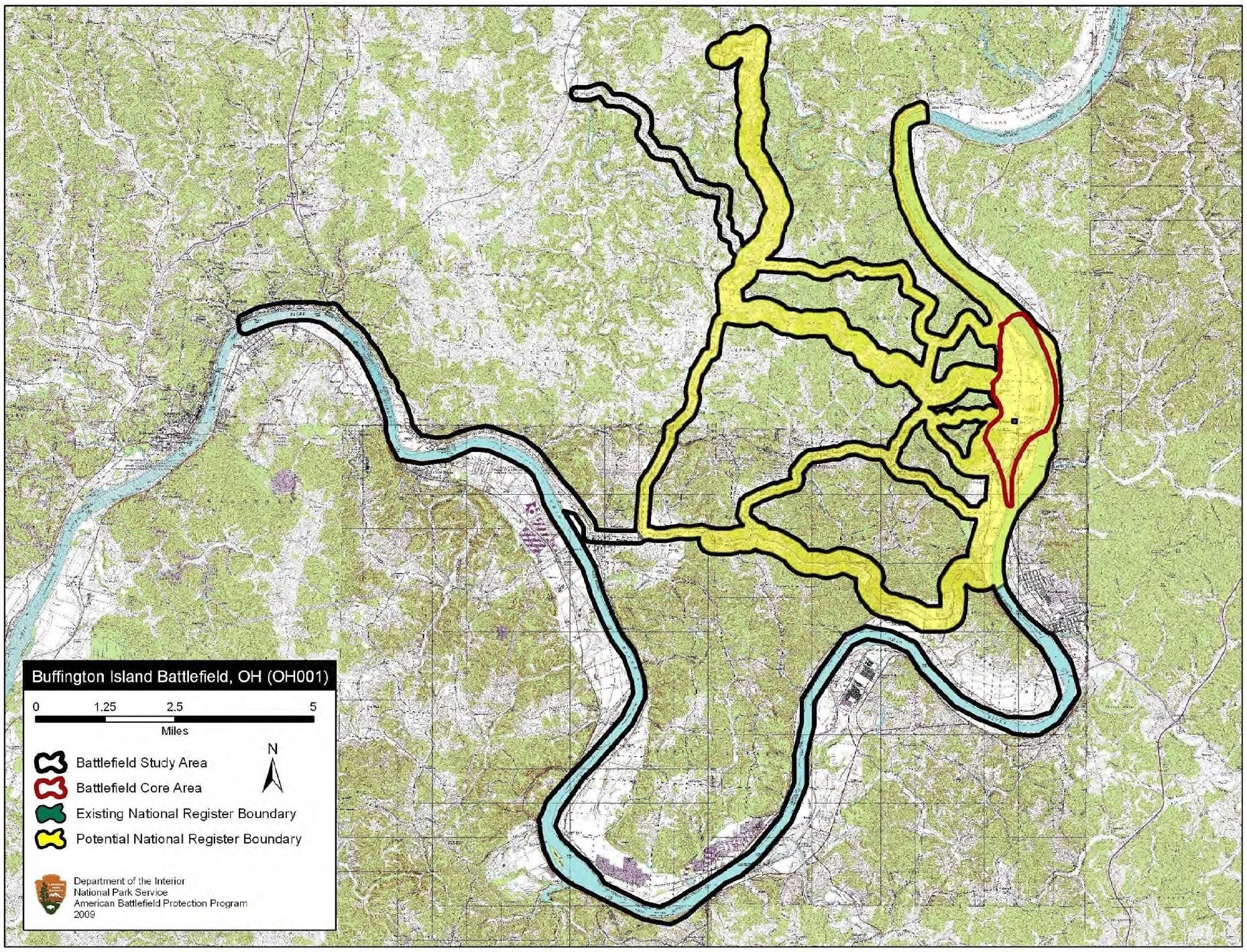

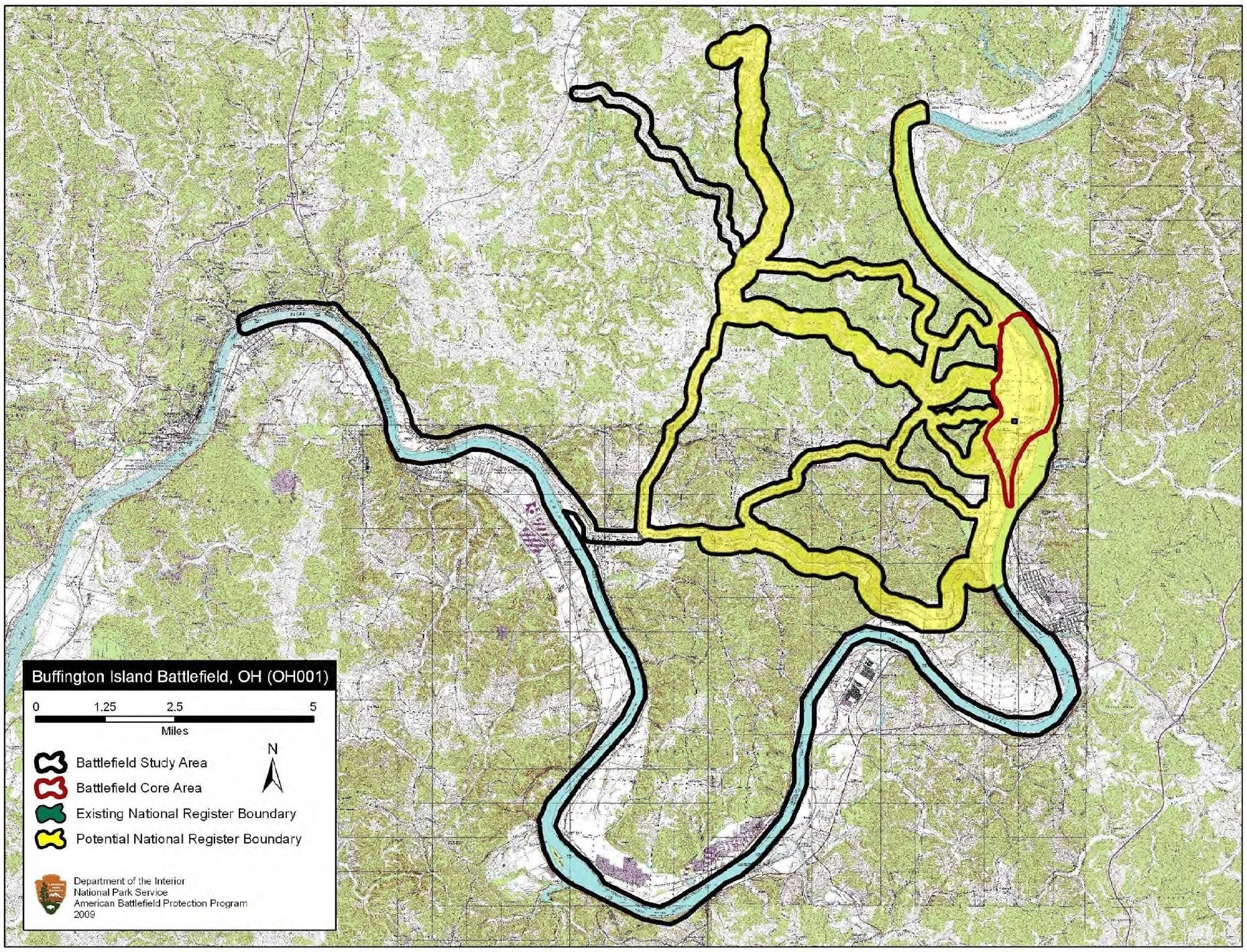

Battlefield preservation

Comparatively little changed on the Buffington Island battlefield in the first century after the fighting; the only substantial difference was the placement of a stoneobelisk

An obelisk (; from grc, ὀβελίσκος ; diminutive of ''obelos'', " spit, nail, pointed pillar") is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. Originally constructed by Anc ...

marking the battle. In 1929, the Ohio Historical Society

Ohio History Connection, formerly The Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society and Ohio Historical Society, is a nonprofit organization incorporated in 1885. Headquartered at the Ohio History Center in Columbus, Ohio, Ohio History Connect ...

took ownership of the property.Owen, Lorrie K., ed. ''Dictionary of Ohio Historic Places''. Vol. 2. St. Clair Shores

St. Clair Shores is a suburban city bordering Lake St. Clair in Macomb County of the U.S. state of Michigan. It forms a part of the Metro Detroit area, and is located about northeast of downtown Detroit. Its population was 59,715 at the 2010 ...

: Somerset, 1999, 985-986. In 1970, the battlefield was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

. Embracing approximately near the river, the designated portion of the battlefield was the county's first location to be recognized as this type of historic site

A historic site or heritage site is an official location where pieces of political, military, cultural, or social history have been preserved due to their cultural heritage value. Historic sites are usually protected by law, and many have been rec ...

. There are threats to the site as gravel mining operations have been allowed. The current organization working to preserve the battlefield is thBuffington Island Battlefield Preservation Foundation

Recently 117 acres have been saved by the efforts of th

American Battlefield Trust

References

Bibliography

* Bennett, B. Kevin and Roth, David, "Battle of Buffington Island," ''Blue & Gray'' magazine, April 1998* Cahill, Lora Schmidt and Mowery, David L., ''Morgan's Raid Across Ohio: The Civil War Guidebook of the John Hunt Morgan Heritage Trail.'' Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio Historical Society, 2014. . * Duke, Basil Wilson, ''A History of Morgan's Cavalry.'' Cincinnati, Ohio: Miami Printing and Pub. Co., 1867

On-line version

* Horwitz, Lester V., ''The Longest Raid of the Civil War.'' Cincinnati, Ohio: Farmcourt Publishing, Inc., 1999. . * Mowery, David L., ''Morgan's Great Raid: The Remarkable Expedition from Kentucky to Ohio.'' Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2013. .

External links

Buffington Island Battlefield Preservation Foundation

- Ohio History Connection

Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation’s Civil War Battlefields

rchivedbr>The Fight to Save Buffington Island Battlefield

rchivedbr>Buffington Island Battlefield Archaeological Project

- Heidelberg University rchived {{authority control National Register of Historic Places in Meigs County, Ohio Geography of Meigs County, Ohio Ohio History Connection Jackson County, West Virginia Meigs County, Ohio Buffington Morgan's Raid

Buffington Island

Buffington Island is an island in the Ohio River in Jackson County, West Virginia near the town of Ravenswood, United States, east of Racine, Ohio. During the American Civil War, the Battle of Buffington Island took place on July 19, 1863, just ...

Buffington Island

Buffington Island is an island in the Ohio River in Jackson County, West Virginia near the town of Ravenswood, United States, east of Racine, Ohio. During the American Civil War, the Battle of Buffington Island took place on July 19, 1863, just ...

Buffington Island

Buffington Island is an island in the Ohio River in Jackson County, West Virginia near the town of Ravenswood, United States, east of Racine, Ohio. During the American Civil War, the Battle of Buffington Island took place on July 19, 1863, just ...

Buffington

1863 in Ohio

1863 in West Virginia

July 1863 events