Battle Of Boston Harbor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The capture of USS ''Chesapeake'', also known as the Battle of Boston Harbor, was fought on 1 June 1813, between the

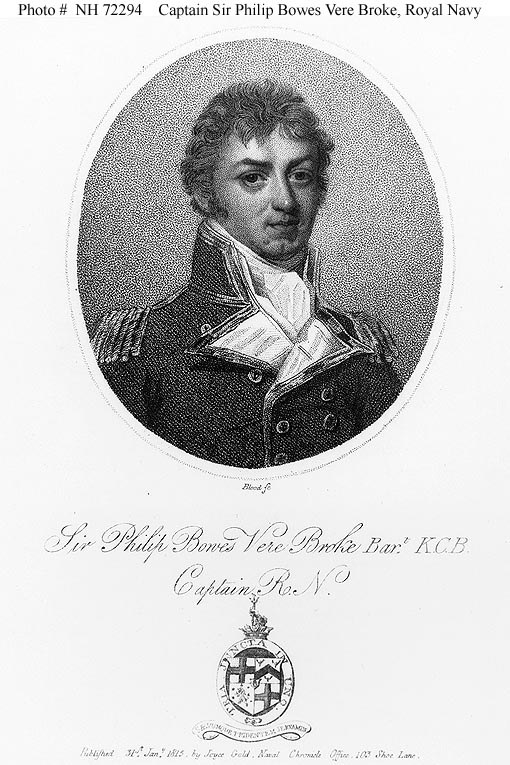

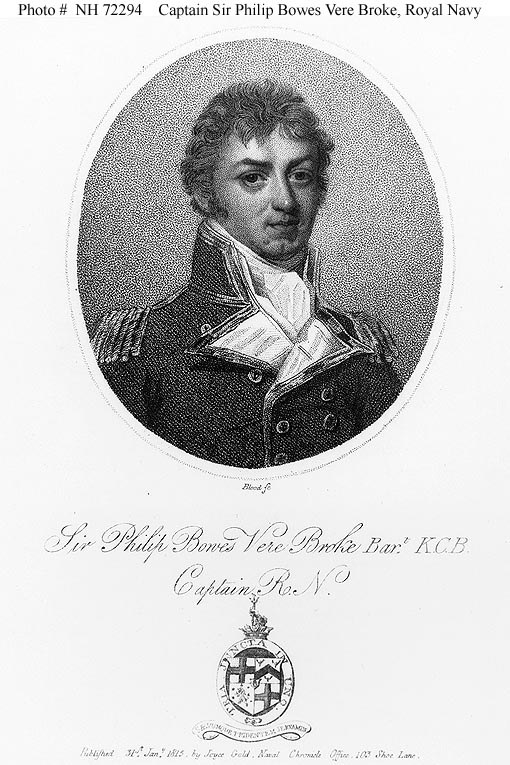

During his long period in command of ''Shannon'', Captain

During his long period in command of ''Shannon'', Captain

Commander Lawrence of the

Commander Lawrence of the

Captain Lawrence did not in fact receive Broke's letter and, according to author Ian W. Toll, it would not have made the slightest difference; Lawrence intended to sail USS ''Chesapeake'' at the first day of favourable weather.Toll 2006, p. 409. The fact that it was not in his nation's interests at this point in the war to be challenging British frigates seems to have not entered into his reasoning. When USS ''President'' had slipped out of harbor, it was to embark on a commerce-raiding mission, which was deemed in the U.S. national interest. Half of the officers and up to one quarter of the crew were new to the ship. In the short time, he was in command of the ''Chesapeake'', Lawrence had twice exercised his crew at the great guns, walking the decks and personally supervising the drill. He also instigated a signal, a bugle call, to call on his crew to board an enemy vessel. Unfortunately the only crew member able to produce a note on the bugle was a "dull-witted" 'loblolly boy' (surgeon's assistant) called William Brown. Lawrence believed that he would win the battle and wrote two quick notes, one to the Secretary of the Navy pronouncing his intentions, and another to his brother in-law asking him to look after Lawrence's wife and children in event of his death.

Bostonians and their neighbours anticipated great results from the celebrated Lawrence and his crew. Local authorities reserved a space at the docks in expectation of accommodating the captured British man-of-war. Also plans were set in motion for a gala victory banquet. As the American warship moved down the harbour, citizens raced to vantage points to witness the fight. Crowds gathered on available heights from Lynn to Malden and from Cohasset to Scituate. A diarist likened the Salem crowds to swarms of bees. The more daring took to boats to follow the ''Chesapeake''. A Boston newspaper reported the bay being covered with civilian craft of all kinds.

HMS ''Shannon'' had been off Boston for 56 days and was running short of provisions, whilst the extended period at sea was wearing the ship down. She would be at a disadvantage facing USS ''Chesapeake'', fresh from harbour and a refit. A boat was despatched carrying the invitation, manned by a Mr Slocum, a discharged American prisoner. The boat had not reached the shore when ''Chesapeake'' was seen underway, sailing out of the harbour. She was flying three American ensigns and a large white flag at the foremast inscribed 'Free Trade and Sailor's Rights'. ''Shannon'' carried 276 officers, seamen and marines of her proper complement, eight recaptured seamen, 22 Irish labourers who had been 48 hours in the ship, of whom only four could speak English, and 24 boys, of whom about 13 were under 12 years of age. Broke had trained his gun crews to fire accurate broadsides into the hulls of enemy vessels, with the aim of killing their gun crews, rather than attempting to disable the enemy ship by firing at the masts and rigging. This was, however, the standard Royal Navy practice of the time, only Broke's efficiency in gunnery training distinguished him in this regard. Lawrence, meanwhile, was confident in his ship, especially since she carried a substantially larger crew. Previous American victories over Royal Navy ships left him expectant of success. Just before the engagement, the American crew gave three cheers.

The two ships were about as close a match in size and force as was possible, given the variations in ship design and armament existing between contemporary navies. USS ''Chesapeake''s (rated at 38 guns) armament of 28 18-pounder long guns was an exact match for HMS ''Shannon''. Measurements proved the ships to be about the same deck length, the only major difference being the ships' complements: ''Chesapeake''s 379 against the ''Shannon''s 330.

* Broke shipped the smaller calibre guns (6-pounder, and 12-pounder carronade) in order that the younger midshipmen and ship's boys had light-weight ordnance that they could practise all aspects of gun laying and firing with.

Captain Lawrence did not in fact receive Broke's letter and, according to author Ian W. Toll, it would not have made the slightest difference; Lawrence intended to sail USS ''Chesapeake'' at the first day of favourable weather.Toll 2006, p. 409. The fact that it was not in his nation's interests at this point in the war to be challenging British frigates seems to have not entered into his reasoning. When USS ''President'' had slipped out of harbor, it was to embark on a commerce-raiding mission, which was deemed in the U.S. national interest. Half of the officers and up to one quarter of the crew were new to the ship. In the short time, he was in command of the ''Chesapeake'', Lawrence had twice exercised his crew at the great guns, walking the decks and personally supervising the drill. He also instigated a signal, a bugle call, to call on his crew to board an enemy vessel. Unfortunately the only crew member able to produce a note on the bugle was a "dull-witted" 'loblolly boy' (surgeon's assistant) called William Brown. Lawrence believed that he would win the battle and wrote two quick notes, one to the Secretary of the Navy pronouncing his intentions, and another to his brother in-law asking him to look after Lawrence's wife and children in event of his death.

Bostonians and their neighbours anticipated great results from the celebrated Lawrence and his crew. Local authorities reserved a space at the docks in expectation of accommodating the captured British man-of-war. Also plans were set in motion for a gala victory banquet. As the American warship moved down the harbour, citizens raced to vantage points to witness the fight. Crowds gathered on available heights from Lynn to Malden and from Cohasset to Scituate. A diarist likened the Salem crowds to swarms of bees. The more daring took to boats to follow the ''Chesapeake''. A Boston newspaper reported the bay being covered with civilian craft of all kinds.

HMS ''Shannon'' had been off Boston for 56 days and was running short of provisions, whilst the extended period at sea was wearing the ship down. She would be at a disadvantage facing USS ''Chesapeake'', fresh from harbour and a refit. A boat was despatched carrying the invitation, manned by a Mr Slocum, a discharged American prisoner. The boat had not reached the shore when ''Chesapeake'' was seen underway, sailing out of the harbour. She was flying three American ensigns and a large white flag at the foremast inscribed 'Free Trade and Sailor's Rights'. ''Shannon'' carried 276 officers, seamen and marines of her proper complement, eight recaptured seamen, 22 Irish labourers who had been 48 hours in the ship, of whom only four could speak English, and 24 boys, of whom about 13 were under 12 years of age. Broke had trained his gun crews to fire accurate broadsides into the hulls of enemy vessels, with the aim of killing their gun crews, rather than attempting to disable the enemy ship by firing at the masts and rigging. This was, however, the standard Royal Navy practice of the time, only Broke's efficiency in gunnery training distinguished him in this regard. Lawrence, meanwhile, was confident in his ship, especially since she carried a substantially larger crew. Previous American victories over Royal Navy ships left him expectant of success. Just before the engagement, the American crew gave three cheers.

The two ships were about as close a match in size and force as was possible, given the variations in ship design and armament existing between contemporary navies. USS ''Chesapeake''s (rated at 38 guns) armament of 28 18-pounder long guns was an exact match for HMS ''Shannon''. Measurements proved the ships to be about the same deck length, the only major difference being the ships' complements: ''Chesapeake''s 379 against the ''Shannon''s 330.

* Broke shipped the smaller calibre guns (6-pounder, and 12-pounder carronade) in order that the younger midshipmen and ship's boys had light-weight ordnance that they could practise all aspects of gun laying and firing with.

As the American ship approached, Broke spoke to his crew, ending with a description of his philosophy of gunnery, "Throw no shot away. Aim every one. Keep cool. Work steadily. Fire into her quarters – maindeck to maindeck, quarterdeck to quarterdeck. Don't try to dismast her. Kill the men and the ship is yours."

The two ships met at half past five in the afternoon, east of the

As the American ship approached, Broke spoke to his crew, ending with a description of his philosophy of gunnery, "Throw no shot away. Aim every one. Keep cool. Work steadily. Fire into her quarters – maindeck to maindeck, quarterdeck to quarterdeck. Don't try to dismast her. Kill the men and the ship is yours."

The two ships met at half past five in the afternoon, east of the  Captain Lawrence realised that his ship's speed would take it past ''Shannon'' and ordered a 'pilot's luff'. This was a small and brief turn to windward which would make the sails shiver and reduce the ship's speed. Just after ''Chesapeake'' began this limited turn away from ''Shannon'', she had her means of manoeuvring entirely disabled as a second round of accurate British fire caused more losses, most critically to the men and officers manning ''Chesapeake''s quarterdeck. Here the helmsmen were killed by a 9-pounder gun that Broke had ordered installed on the

Captain Lawrence realised that his ship's speed would take it past ''Shannon'' and ordered a 'pilot's luff'. This was a small and brief turn to windward which would make the sails shiver and reduce the ship's speed. Just after ''Chesapeake'' began this limited turn away from ''Shannon'', she had her means of manoeuvring entirely disabled as a second round of accurate British fire caused more losses, most critically to the men and officers manning ''Chesapeake''s quarterdeck. Here the helmsmen were killed by a 9-pounder gun that Broke had ordered installed on the  At almost the same time as ''Chesapeake'' lost control of her helm, her fore-

At almost the same time as ''Chesapeake'' lost control of her helm, her fore-

In contrast to the confusion and loss of leadership aboard the American vessel, the British boarding party was being effectively organised. A number of small-arms men rushed aboard ''Chesapeake'', led by Broke, including the

In contrast to the confusion and loss of leadership aboard the American vessel, the British boarding party was being effectively organised. A number of small-arms men rushed aboard ''Chesapeake'', led by Broke, including the

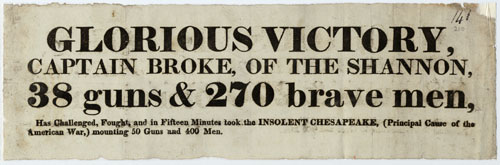

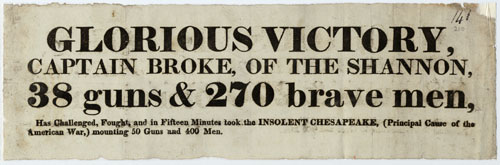

The engagement had lasted just ten minutes according to ''Shannon''s log, or eleven minutes by Lieutenant Wallis' watch. Broke more modestly claimed fifteen minutes in his official despatch. ''Shannon'' had lost 23 men killed, and had 56 wounded. ''Chesapeake'' had about 48 killed, including four lieutenants, the master and many other of her officers, and 99 wounded. ''Shannon'' had been hit by a total of 158 projectiles, ''Chesapeake'' by 362 (these figures include grapeshot). In the time the batteries of both ships were firing, the Americans had been exposed to 44 roundshot, whilst the British had received 10 or 11 in reply (these are figures for shot which would have produced casualties or material damage; some of ''Chesapeake''s shot was fired low, bouncing off ''Shannon''s side at waterline level). Even before being boarded, ''Chesapeake'' had lost the gunnery duel by a considerable margin.

A large cask of un-slaked

The engagement had lasted just ten minutes according to ''Shannon''s log, or eleven minutes by Lieutenant Wallis' watch. Broke more modestly claimed fifteen minutes in his official despatch. ''Shannon'' had lost 23 men killed, and had 56 wounded. ''Chesapeake'' had about 48 killed, including four lieutenants, the master and many other of her officers, and 99 wounded. ''Shannon'' had been hit by a total of 158 projectiles, ''Chesapeake'' by 362 (these figures include grapeshot). In the time the batteries of both ships were firing, the Americans had been exposed to 44 roundshot, whilst the British had received 10 or 11 in reply (these are figures for shot which would have produced casualties or material damage; some of ''Chesapeake''s shot was fired low, bouncing off ''Shannon''s side at waterline level). Even before being boarded, ''Chesapeake'' had lost the gunnery duel by a considerable margin.

A large cask of un-slaked

After the victory, a prize crew was put aboard ''Chesapeake''. The commander of the prize, Lieutenant Falkiner, had a good deal of trouble from the restive Americans, who outnumbered his own men. He had some of the leaders of the unrest transferred to ''Shannon'' in the leg-irons that had, ironically, been shipped aboard ''Chesapeake'' to deal with expected British prisoners. The rest of the American crew were rendered docile by the expedient of a carpenter cutting scuttles (holes) in the maindeck through which two 18-pounder cannon, loaded with grapeshot, were pointed at them.

''Shannon'', commanded by Lieutenant Provo Wallis, escorted her prize into Halifax, arriving there on 6 June. On the entry of the two frigates into the harbour, the naval ships already at anchor manned their yards, bands played martial music and each ship ''Shannon'' passed greeted her with cheers. The 320 American survivors of the battle were interned on Melville Island in 1813, and their ship, taken into British service and renamed HMS ''Chesapeake'', was used to ferry prisoners from Melville Island to England's

After the victory, a prize crew was put aboard ''Chesapeake''. The commander of the prize, Lieutenant Falkiner, had a good deal of trouble from the restive Americans, who outnumbered his own men. He had some of the leaders of the unrest transferred to ''Shannon'' in the leg-irons that had, ironically, been shipped aboard ''Chesapeake'' to deal with expected British prisoners. The rest of the American crew were rendered docile by the expedient of a carpenter cutting scuttles (holes) in the maindeck through which two 18-pounder cannon, loaded with grapeshot, were pointed at them.

''Shannon'', commanded by Lieutenant Provo Wallis, escorted her prize into Halifax, arriving there on 6 June. On the entry of the two frigates into the harbour, the naval ships already at anchor manned their yards, bands played martial music and each ship ''Shannon'' passed greeted her with cheers. The 320 American survivors of the battle were interned on Melville Island in 1813, and their ship, taken into British service and renamed HMS ''Chesapeake'', was used to ferry prisoners from Melville Island to England's  As the first major naval victory in the war of 1812 for the British, the capture raised the morale of the Royal Navy. After setting out on 5 September for a brief cruise under a Captain Teahouse, ''Shannon'' departed for England on 4 October, carrying the recovering Broke. They arrived at Portsmouth on 2 November. After the successful action, Lieutenants Wallis and Falkiner were promoted to the rank of commander, and Messrs. Etough and Smith were made lieutenants. Broke was made a

As the first major naval victory in the war of 1812 for the British, the capture raised the morale of the Royal Navy. After setting out on 5 September for a brief cruise under a Captain Teahouse, ''Shannon'' departed for England on 4 October, carrying the recovering Broke. They arrived at Portsmouth on 2 November. After the successful action, Lieutenants Wallis and Falkiner were promoted to the rank of commander, and Messrs. Etough and Smith were made lieutenants. Broke was made a

online

* * * * * * James, William, and Chamier, Frederick (1837) ''The Naval History of Great Britain, from the Declaration of War by France in 1793, to the Accession of George IV,'' Vol VI. Richard Bentley, London. * Lambert, Andrew (2012) ''The Challenge: Britain Against America in the Naval War of 1812'', Faber and Faber, London. * * * * Pullen, Hugh Francis. ''The Shannon and the Chesapeake'' (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1970) * * * * * Voelcker, Tim (2013) ''Broke of the Shannon: and the War of 1812'', Seaforth Publishing , 9781473831322 *

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

and the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

frigate , as part of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

between the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

. The ''Chesapeake'' was captured in a brief but intense action in which 71 men were killed. This was the only frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

action of the war in which there was no preponderance of force on either side.

At Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, Captain James Lawrence

James Lawrence (October 1, 1781 – June 4, 1813) was an officer of the United States Navy. During the War of 1812, he commanded in a single-ship action against , commanded by Philip Broke. He is probably best known today for his last words, ...

took command of ''Chesapeake'' on 20 May 1813, and on 1 June, put to sea to meet the waiting HMS ''Shannon'', commanded by Captain Philip Broke

Sir Philip Bowes Vere Broke, 1st Baronet (; 9 September 1776 – 2 January 1841) was a distinguished officer in the British Royal Navy. During his lifetime, he was often referred to as "Broke of the ''Shannon''", a reference to his notable comm ...

. Broke had issued a written challenge to ''Chesapeake'' commander, but ''Chesapeake'' had sailed before it was delivered.

''Chesapeake'' suffered heavily in the exchange of gunfire, having her wheel and fore topsail

A topsail ("tops'l") is a sail set above another sail; on square-rigged vessels further sails may be set above topsails.

Square rig

On a square rigged vessel, a topsail is a typically trapezoidal shaped sail rigged above the course sail and ...

halyard

In sailing, a halyard or halliard is a line (rope) that is used to hoist a ladder, sail, flag or yard. The term ''halyard'' comes from the phrase "to haul yards". Halyards, like most other parts of the running rigging, were classically made of n ...

shot away, rendering her unmanoeuvrable. Lawrence himself was mortally wounded and was carried below. The American crew struggled to carry out their captain's last order, "Don't give up the ship!", with the British boarding party quickly overwhelming them. The battle was notably intense but of short duration, lasting ten to fifteen minutes, in which time 226 men were killed or wounded. ''Shannon'' captain was severely injured in fighting on the forecastle, but survived his wounds.

''Chesapeake'' and her crew were taken to Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. The ...

, where the sailors were taken to prisoner-of-war camp

A prisoner-of-war camp (often abbreviated as POW camp) is a site for the containment of enemy fighters captured by a belligerent power in time of war.

There are significant differences among POW camps, internment camps, and military prisons. P ...

s; the ship was repaired and taken into service by the Royal Navy. She was sold at Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, in 1819 and broken up. Surviving timbers were used to build the nearby Chesapeake Mill

The Chesapeake Mill is a watermill in Wickham, Hampshire, England. The flour mill was constructed in 1820 using the timbers of HMS ''Chesapeake'', which had previously been the United States Navy frigate . The ''Chesapeake'' was attacked and bo ...

in Wickham and can be seen and visited to this day. ''Shannon'' survived longer, being broken up in 1859.

Prelude

Philip Broke and his naval gunnery

During his long period in command of ''Shannon'', Captain

During his long period in command of ''Shannon'', Captain Philip Broke

Sir Philip Bowes Vere Broke, 1st Baronet (; 9 September 1776 – 2 January 1841) was a distinguished officer in the British Royal Navy. During his lifetime, he was often referred to as "Broke of the ''Shannon''", a reference to his notable comm ...

of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

introduced many practical refinements to his 'great guns', which were virtually unheard of elsewhere in contemporary naval gunnery

Naval artillery is artillery mounted on a warship, originally used only for naval warfare and then subsequently used for shore bombardment and anti-aircraft roles. The term generally refers to tube-launched projectile-firing weapons and excludes ...

. He had 'dispart sights' fitted to his 18-pounder long guns, which improved aiming as they compensated for the external narrowing of the barrels from the breech to the muzzle. He had adjustable tangent sights that would give accuracy at different ranges. He had the elevating 'quoins' (wedge-shaped pieces of wood placed under the breech) of his long guns grooved to mark various degrees of elevation so that his guns could be reliably levelled to fire horizontally in any state of heeling of the ship under a press of sail. The carronade

A carronade is a short, smoothbore, cast-iron cannon which was used by the Royal Navy. It was first produced by the Carron Company, an ironworks in Falkirk, Scotland, and was used from the mid-18th century to the mid-19th century. Its main func ...

s were similarly treated, but the elevating screws on these cannon were marked in paint. As the decks of contemporary ships curved upwards towards the stern and bows, he cut down the wheels on the "up-slope" side of each cannon's carriage in order that all guns were level with the horizon. He also introduced a system where bearings were incised into the deck next to each gun; fire could then be directed to any bearing independent of the ability of any particular gun crew to see the target. Fire from the whole battery could also be focused on any part of an enemy ship.

Broke drilled his crew to an extremely high standard of naval gunnery; he regularly had them fire at targets, such as floating barrels. Often these drills would be made into competitions to see which gun crew could hit the target first and how fast they could do so. He even had his gun crews fire at targets 'blindfold' to good effect; they were only given the bearing to lay their gun on without being allowed to sight the gun on the target themselves. This constituted a very early example of 'director firing'.

In addition to these gunnery drills, Broke was fond of preparing hypothetical scenarios to test his crew. For example, after all hands had been drummed to quarters, he would inform them of a theoretical attack and see how they would act to defend the ship. Though the use of cutlasses in training was avoided, a method of swordsmanship training called 'singlestick

Singlestick is a martial art that uses a wooden stick as its weapon. It began as a way of training soldiers in the use of backswords (such as the sabre or the cutlass). Canne de combat, a French form of stick fighting, is similar to singlestick p ...

' was regularly practiced. This was a game employing roughly similar cuts, thrusts and parries as were used with the cutlass, but as it was played with wooden sticks with wicker hand guards; hits, although painful, were not often dangerous. It soon developed quickness of eye and wrist. Many of the crew became very expert.

James Lawrence

Commander Lawrence of the

Commander Lawrence of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

returned from a successful war cruise having defeated the sloop HMS ''Peacock''. He was promoted to captain for his victory, and received orders to take command of USS ''Chesapeake''. It was not a command that he particularly wanted. He had hoped for the larger frigate instead. Lawrence travelled to Boston. He found that most of the former crew of ''Chesapeake'' had left over a dispute over prize money and had since been replaced. Lawrence's prior experience of the British Navy worked against him. In his former battle with HMS ''Peacock'', the warship had been bravely fought, but the British gunnery had been nothing less than atrocious. His crew was laden with good seamen; however, they lacked the time working together that was needed to change a collection of good seamen into an efficient fighting crew. Lawrence's assumptions concerning the poor quality of the opposition would leave him over-confident in facing the adversary he was about to encounter.

Issuing a challenge

Eager to engage and defeat one of the American frigates that had already scored a number of victories over the Royal Navy in single-ship confrontations, Broke prepared a challenge. had already slipped out of the harbour under the cover of fog and had evaded the British. ''Constitution'' was undergoing extensive repairs and alterations and would not be ready for sea in the foreseeable future. However, ''Chesapeake'' appeared to be ready to put to sea. Consequently, Broke decided to challenge ''Chesapeake'', which had been refitting inBoston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

harbour under the command of Captain James Lawrence, offering single ship-to-ship combat. Whilst patrolling offshore, ''Shannon'' had intercepted and captured a number of American ships attempting to reach the harbour. After sending two of them off to Halifax, he found that his crew was being dangerously reduced. Broke therefore resorted to burning the rest of the prizes in order to conserve his highly trained crew in anticipation of the battle with ''Chesapeake''. The boats from the burnt prizes were sent into Boston, carrying Broke's oral invitation to Lawrence to come out and engage him. Broke had already sent ''Tenedos'' away in the hope that the more favourable odds would entice the Americans out, but eventually began to despair that ''Chesapeake'' would ever come out of the harbour. He finally decided to send a written challenge. In this he was copying his adversary. Lawrence had earlier in the war, when captain of the sloop of war , sent a written invitation to the captain of the British sloop of war to a single-ship contest. Lawrence's offer had been declined.

Captain Lawrence did not in fact receive Broke's letter and, according to author Ian W. Toll, it would not have made the slightest difference; Lawrence intended to sail USS ''Chesapeake'' at the first day of favourable weather.Toll 2006, p. 409. The fact that it was not in his nation's interests at this point in the war to be challenging British frigates seems to have not entered into his reasoning. When USS ''President'' had slipped out of harbor, it was to embark on a commerce-raiding mission, which was deemed in the U.S. national interest. Half of the officers and up to one quarter of the crew were new to the ship. In the short time, he was in command of the ''Chesapeake'', Lawrence had twice exercised his crew at the great guns, walking the decks and personally supervising the drill. He also instigated a signal, a bugle call, to call on his crew to board an enemy vessel. Unfortunately the only crew member able to produce a note on the bugle was a "dull-witted" 'loblolly boy' (surgeon's assistant) called William Brown. Lawrence believed that he would win the battle and wrote two quick notes, one to the Secretary of the Navy pronouncing his intentions, and another to his brother in-law asking him to look after Lawrence's wife and children in event of his death.

Bostonians and their neighbours anticipated great results from the celebrated Lawrence and his crew. Local authorities reserved a space at the docks in expectation of accommodating the captured British man-of-war. Also plans were set in motion for a gala victory banquet. As the American warship moved down the harbour, citizens raced to vantage points to witness the fight. Crowds gathered on available heights from Lynn to Malden and from Cohasset to Scituate. A diarist likened the Salem crowds to swarms of bees. The more daring took to boats to follow the ''Chesapeake''. A Boston newspaper reported the bay being covered with civilian craft of all kinds.

HMS ''Shannon'' had been off Boston for 56 days and was running short of provisions, whilst the extended period at sea was wearing the ship down. She would be at a disadvantage facing USS ''Chesapeake'', fresh from harbour and a refit. A boat was despatched carrying the invitation, manned by a Mr Slocum, a discharged American prisoner. The boat had not reached the shore when ''Chesapeake'' was seen underway, sailing out of the harbour. She was flying three American ensigns and a large white flag at the foremast inscribed 'Free Trade and Sailor's Rights'. ''Shannon'' carried 276 officers, seamen and marines of her proper complement, eight recaptured seamen, 22 Irish labourers who had been 48 hours in the ship, of whom only four could speak English, and 24 boys, of whom about 13 were under 12 years of age. Broke had trained his gun crews to fire accurate broadsides into the hulls of enemy vessels, with the aim of killing their gun crews, rather than attempting to disable the enemy ship by firing at the masts and rigging. This was, however, the standard Royal Navy practice of the time, only Broke's efficiency in gunnery training distinguished him in this regard. Lawrence, meanwhile, was confident in his ship, especially since she carried a substantially larger crew. Previous American victories over Royal Navy ships left him expectant of success. Just before the engagement, the American crew gave three cheers.

The two ships were about as close a match in size and force as was possible, given the variations in ship design and armament existing between contemporary navies. USS ''Chesapeake''s (rated at 38 guns) armament of 28 18-pounder long guns was an exact match for HMS ''Shannon''. Measurements proved the ships to be about the same deck length, the only major difference being the ships' complements: ''Chesapeake''s 379 against the ''Shannon''s 330.

* Broke shipped the smaller calibre guns (6-pounder, and 12-pounder carronade) in order that the younger midshipmen and ship's boys had light-weight ordnance that they could practise all aspects of gun laying and firing with.

Captain Lawrence did not in fact receive Broke's letter and, according to author Ian W. Toll, it would not have made the slightest difference; Lawrence intended to sail USS ''Chesapeake'' at the first day of favourable weather.Toll 2006, p. 409. The fact that it was not in his nation's interests at this point in the war to be challenging British frigates seems to have not entered into his reasoning. When USS ''President'' had slipped out of harbor, it was to embark on a commerce-raiding mission, which was deemed in the U.S. national interest. Half of the officers and up to one quarter of the crew were new to the ship. In the short time, he was in command of the ''Chesapeake'', Lawrence had twice exercised his crew at the great guns, walking the decks and personally supervising the drill. He also instigated a signal, a bugle call, to call on his crew to board an enemy vessel. Unfortunately the only crew member able to produce a note on the bugle was a "dull-witted" 'loblolly boy' (surgeon's assistant) called William Brown. Lawrence believed that he would win the battle and wrote two quick notes, one to the Secretary of the Navy pronouncing his intentions, and another to his brother in-law asking him to look after Lawrence's wife and children in event of his death.

Bostonians and their neighbours anticipated great results from the celebrated Lawrence and his crew. Local authorities reserved a space at the docks in expectation of accommodating the captured British man-of-war. Also plans were set in motion for a gala victory banquet. As the American warship moved down the harbour, citizens raced to vantage points to witness the fight. Crowds gathered on available heights from Lynn to Malden and from Cohasset to Scituate. A diarist likened the Salem crowds to swarms of bees. The more daring took to boats to follow the ''Chesapeake''. A Boston newspaper reported the bay being covered with civilian craft of all kinds.

HMS ''Shannon'' had been off Boston for 56 days and was running short of provisions, whilst the extended period at sea was wearing the ship down. She would be at a disadvantage facing USS ''Chesapeake'', fresh from harbour and a refit. A boat was despatched carrying the invitation, manned by a Mr Slocum, a discharged American prisoner. The boat had not reached the shore when ''Chesapeake'' was seen underway, sailing out of the harbour. She was flying three American ensigns and a large white flag at the foremast inscribed 'Free Trade and Sailor's Rights'. ''Shannon'' carried 276 officers, seamen and marines of her proper complement, eight recaptured seamen, 22 Irish labourers who had been 48 hours in the ship, of whom only four could speak English, and 24 boys, of whom about 13 were under 12 years of age. Broke had trained his gun crews to fire accurate broadsides into the hulls of enemy vessels, with the aim of killing their gun crews, rather than attempting to disable the enemy ship by firing at the masts and rigging. This was, however, the standard Royal Navy practice of the time, only Broke's efficiency in gunnery training distinguished him in this regard. Lawrence, meanwhile, was confident in his ship, especially since she carried a substantially larger crew. Previous American victories over Royal Navy ships left him expectant of success. Just before the engagement, the American crew gave three cheers.

The two ships were about as close a match in size and force as was possible, given the variations in ship design and armament existing between contemporary navies. USS ''Chesapeake''s (rated at 38 guns) armament of 28 18-pounder long guns was an exact match for HMS ''Shannon''. Measurements proved the ships to be about the same deck length, the only major difference being the ships' complements: ''Chesapeake''s 379 against the ''Shannon''s 330.

* Broke shipped the smaller calibre guns (6-pounder, and 12-pounder carronade) in order that the younger midshipmen and ship's boys had light-weight ordnance that they could practise all aspects of gun laying and firing with.

Battle

Gunnery duel

As the American ship approached, Broke spoke to his crew, ending with a description of his philosophy of gunnery, "Throw no shot away. Aim every one. Keep cool. Work steadily. Fire into her quarters – maindeck to maindeck, quarterdeck to quarterdeck. Don't try to dismast her. Kill the men and the ship is yours."

The two ships met at half past five in the afternoon, east of the

As the American ship approached, Broke spoke to his crew, ending with a description of his philosophy of gunnery, "Throw no shot away. Aim every one. Keep cool. Work steadily. Fire into her quarters – maindeck to maindeck, quarterdeck to quarterdeck. Don't try to dismast her. Kill the men and the ship is yours."

The two ships met at half past five in the afternoon, east of the Boston Light

Boston Light is a lighthouse located on Little Brewster Island in outer Boston Harbor, Massachusetts. The first lighthouse to be built on the site dates back to 1716, and was the first lighthouse to be built in what is now the United States. The c ...

, between Cape Ann

Cape Ann is a rocky peninsula in northeastern Massachusetts, United States on the Atlantic Ocean. It is about northeast of Boston and marks the northern limit of Massachusetts Bay. Cape Ann includes the city of Gloucester and the towns of ...

and Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of mainland Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer mont ...

. ''Shannon'' was flying a weather-worn blue ensign

The Blue Ensign is a flag, one of several British ensigns, used by certain organisations or territories associated or formerly associated with the United Kingdom. It is used either plain or Defacement (flag), defaced with a Heraldic badge, ...

, and her dilapidated outside appearance after a long period at sea suggested that she would be an easy opponent. Observing the ''Chesapeakes many flags, a sailor had questioned Broke: "Mayn't we have three ensigns, sir, like she has?" "No," said Broke, "we've always been an unassuming ship." HMS ''Shannon'' refused to fire upon USS ''Chesapeake'' as she bore down, nor did USS ''Chesapeake'' attempt to rake

Rake may refer to:

* Rake (stock character), a man habituated to immoral conduct

* Rake (theatre), the artificial slope of a theatre stage

Science and technology

* Rake receiver, a radio receiver

* Rake (geology), the angle between a feature on a ...

HMS ''Shannon'', despite having the weather gage

The weather gage (sometimes spelled weather gauge) is the advantageous position of a fighting sailing vessel relative to another. It is also known as "nautical gauge" as it is related to the sea shore. The concept is from the Age of Sail and is now ...

. Lawrence's behaviour that day earned him praise from the British officers for gallantry.

The two ships opened fire just before 18:00 at a range of about , with ''Shannon'' scoring the first hit, striking ''Chesapeake'' on one of her forward gunports with two round shot and a bag of musket balls fired by William Mindham, the gun captain of the aftmost of ''Shannons starboard 18-pounders. ''Chesapeake'' was moving faster than ''Shannon'', and as she ranged down the side of the British ship, the destruction inflicted by the precise and methodical gunnery of the British crew moved aft with the American's forward gun crews suffering the heaviest losses. However, the American crew were well drilled and, despite their losses, returned fire briskly. As ''Chesapeake'' was heeling, many of their shots struck the water or waterline of ''Shannon'' causing little damage, but American carronade fire caused serious damage to ''Shannon''s rigging. In particular, a 32-pound carronade ball struck the piled shot for the ''Shannon''s 12-pounder gun that was stowed in the main chains; the shot was propelled through the timbers to scatter like hail across the gundeck.

Captain Lawrence realised that his ship's speed would take it past ''Shannon'' and ordered a 'pilot's luff'. This was a small and brief turn to windward which would make the sails shiver and reduce the ship's speed. Just after ''Chesapeake'' began this limited turn away from ''Shannon'', she had her means of manoeuvring entirely disabled as a second round of accurate British fire caused more losses, most critically to the men and officers manning ''Chesapeake''s quarterdeck. Here the helmsmen were killed by a 9-pounder gun that Broke had ordered installed on the

Captain Lawrence realised that his ship's speed would take it past ''Shannon'' and ordered a 'pilot's luff'. This was a small and brief turn to windward which would make the sails shiver and reduce the ship's speed. Just after ''Chesapeake'' began this limited turn away from ''Shannon'', she had her means of manoeuvring entirely disabled as a second round of accurate British fire caused more losses, most critically to the men and officers manning ''Chesapeake''s quarterdeck. Here the helmsmen were killed by a 9-pounder gun that Broke had ordered installed on the quarter deck

The quarterdeck is a raised deck behind the main mast of a sailing ship. Traditionally it was where the captain commanded his vessel and where the ship's colours were kept. This led to its use as the main ceremonial and reception area on bo ...

for that very purpose, and the same gun shortly afterwards shot away the wheel itself. Surviving American gun crews did land hits on ''Shannon'' in their second round of fire, especially American carronade fire which swept ''Shannon''s forecastle, killing three men, wounding others and disabling ''Shannon''s forward 9-pounder gun while one round shot demolished ''Shannon''s ship's bell.

At almost the same time as ''Chesapeake'' lost control of her helm, her fore-

At almost the same time as ''Chesapeake'' lost control of her helm, her fore-topsail

A topsail ("tops'l") is a sail set above another sail; on square-rigged vessels further sails may be set above topsails.

Square rig

On a square rigged vessel, a topsail is a typically trapezoidal shaped sail rigged above the course sail and ...

halyard

In sailing, a halyard or halliard is a line (rope) that is used to hoist a ladder, sail, flag or yard. The term ''halyard'' comes from the phrase "to haul yards". Halyards, like most other parts of the running rigging, were classically made of n ...

was shot away, her fore-topsail yard

The yard (symbol: yd) is an English unit of length in both the British imperial and US customary systems of measurement equalling 3 feet or 36 inches. Since 1959 it has been by international agreement standardized as exactly 0.914 ...

then dropped, and she 'luffed up'. Losing her forward momentum, she yawed further into the wind until she was 'in irons', her sails were pressed back against her masts and she then made sternway (went backwards). Her port stern quarter (rear left corner) made contact with ''Shannon''s starboard side, level with the fifth gunport from the bow, and ''Chesapeake'' was caught by the projecting fluke of one of ''Shannon''s anchors, which had been stowed on the gangway. ''Chesapeake''s spanker boom then swung over the deck of the British ship. Mr Stevens, ''Shannon''s boatswain

A boatswain ( , ), bo's'n, bos'n, or bosun, also known as a deck boss, or a qualified member of the deck department, is the most senior rate of the deck department and is responsible for the components of a ship's hull. The boatswain supervi ...

, lashed the boom inboard to keep the two ships together, and lost an arm as he did so.

Trapped against ''Shannon'' at an angle in which few of her guns could fire on the British ship, and unable to manoeuvre away, ''Chesapeake''s stern now became exposed and was swept by raking fire

In naval warfare during the Age of Sail, raking fire was cannon fire directed parallel to the long axis of an enemy ship from ahead (in front of the ship) or astern (behind the ship). Although each shot was directed against a smaller profile ...

. Earlier in the action ''Shannon''s gunnery had devastated ''Chesapeake''s forward gun crews; this destruction was now inflicted on the gun crews in the aft part of the ship. The American ship's situation worsened when a small open cask of musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually d ...

cartridges abaft the mizzen-mast

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the centre-line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, and giving necessary height to a navigation lig ...

blew up. When the smoke cleared, Broke judged the time was right and gave the order to board. Captain Lawrence also gave the order to board, but the frightened bugler aboard ''Chesapeake'', William Brown, failed to sound the call, and only those near Lawrence heard his command. By this time Lawrence was the only officer left on the upper deck, as Lieutenants Ludlow and Ballard had been wounded. Lieutenant Cox, who had brought up men from the lower deck to form a boarding party, reached the quarterdeck only to find that his captain had been badly, indeed mortally, wounded by musket fire. Lawrence was clinging to the binnacle

A binnacle is a waist-high case or stand on the deck of a ship, generally mounted in front of the helmsman, in which navigational instruments are placed for easy and quick reference as well as to protect the delicate instruments. Its traditional p ...

in order to stay upright; Cox, who had served all his sea life with Lawrence, carried him down to the cockpit with the help of two sailors. As he was being taken down Lawrence called out "Tell the men to fire faster! Don't give up the ship!"Padfield 1968, p. 173.

The British board

In contrast to the confusion and loss of leadership aboard the American vessel, the British boarding party was being effectively organised. A number of small-arms men rushed aboard ''Chesapeake'', led by Broke, including the

In contrast to the confusion and loss of leadership aboard the American vessel, the British boarding party was being effectively organised. A number of small-arms men rushed aboard ''Chesapeake'', led by Broke, including the purser

A purser is the person on a ship principally responsible for the handling of money on board. On modern merchant ships, the purser is the officer responsible for all administration (including the ship's cargo and passenger manifests) and supply. ...

, Mr G. Aldham, and the clerk, Mr John Dunn. Aldham and Dunn were killed as they crossed the gangway, but the rest of the party made it onto ''Chesapeake''. Captain Broke, at the head of not more than twenty men, stepped from the rail of the waist-hammock netting onto the muzzle of the port-side carronade of ''Chesapeake'' closest to the stern, and from there he jumped down to her quarterdeck. As the British boarded there were no American officers left on the quarterdeck to organise resistance.

The maindeck of ''Chesapeake'' was almost deserted, having been swept by ''Shannon''s gunfire; the surviving gun crews had either responded to the call for boarders or had taken refuge below. Two American officers, Lieutenant Cox (who had returned from carrying Captain Lawrence down to the surgeon) and Midshipman Russell saw that the aftmost 18-pounders on the port side still bore on ''Shannon''. Working between them, they managed to fire both.

Lieutenant Ludlow, who had been slightly wounded and had gone down to ''Chesapeake''s cockpit for treatment, now returned to the upper decks, rallying some of the American crew as he did so. Lieutenant Budd joined him with a band of men he had led up the fore-hatch. Ludlow led them in a counter-attack which pushed the British back as far as the binnacle

A binnacle is a waist-high case or stand on the deck of a ship, generally mounted in front of the helmsman, in which navigational instruments are placed for easy and quick reference as well as to protect the delicate instruments. Its traditional p ...

. However, a wave of British reinforcements arrived, Ludlow received a mortal wound from a cutlass, and the Americans were again thrown back. James Bulger, one of ''Shannon''s Irishmen, charged into the Americans wielding a boarding pike and shouting Gaelic curses – "And then did I not spit them, beJaysus!" Lacking officers to lead them (Lieutenant Budd had also been wounded by a cutlass) and lacking support from below, the Americans were driven back by the boarders. American resistance then fell apart, with the exception of a band of men on the forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is the phrase " be ...

and those in the tops. A number of the Americans driven from the upper decks jostled each other to get down the main hatchway to the comparative safety of the berth deck. Seeing this, Lt. Cox called to them, "You damned cowardly sons of bitches! What are you jumping below for?" When asked by a nearby midshipman if he should stop them by cutting a few down, Cox replied, "No sir, it is of no use."

Fighting had also been ongoing between the tops

Total Operations Processing System (TOPS) is a computer system for managing railway locomotives and rolling stock, known for many years of use in the United Kingdom.

TOPS was originally developed between the Southern Pacific Railroad (SP), S ...

(platforms at the junction of mast and topmast) of the ships, as rival sharpshooters fired upon their opponents and upon sailors on the exposed decks below. While the ships were locked together, the British marksmen, led by midshipman William Smith, commander of the fore-top, stormed ''Chesapeake''s fore-top over the yard-arm and killed all the Americans there. Following this, the wind tore the two ships apart, and ''Chesapeake'' was blown around the bows of ''Shannon.'' This left the British boarders, about fifty-strong, stranded. However, organised resistance aboard the American ship had almost ceased by this time.

Broke himself led a charge against a number of the Americans who had managed to rally on the forecastle. Three American sailors, probably from the rigging, descended and attacked him. Taken by surprise, he killed the first, but the second hit him with a musket which stunned him, whilst the third sliced open his skull with his sabre, knocking him to the deck. Before the sailor could finish Broke off, the American was bayoneted by a British Marine named John Hill. ''Shannon''s crew rallied to the defence of their captain and carried the forecastle, killing the remaining Americans. Broke sat, dizzied and weak, on a carronade slide, and his head was bound up by William Mindham, who used his own neckerchief. One of ''Shannon''s lieutenants, Provo Wallis

Provo or Provos may refer to:

In geography In the United States

* Provo, Kentucky, an unincorporated community

* Provo, South Dakota, an unincorporated community

* Provo Township, Fall River County, South Dakota

* Provo, Utah, a city

** Provo Pe ...

, believed that Broke's three assailants were probably British deserters. The desperate and violent attempt on Broke's life made by these men may have been motivated by the fact that they faced the death penalty under the Royal Navy's Articles of War

The Articles of War are a set of regulations drawn up to govern the conduct of a country's military and naval forces. The first known usage of the phrase is in Robert Monro's 1637 work ''His expedition with the worthy Scot's regiment called Mac-k ...

as deserters. Meanwhile, ''Shannon''s First Lieutenant, Mr George T. L. Watt, had attempted to hoist the British colours over ''Chesapeake''s, but this was misinterpreted aboard ''Shannon,'' and he was hit in the forehead by grapeshot and killed as he did so.

''Chesapeake'' is taken

The British had cleared the upper decks of American resistance, and most of ''Chesapeake''s crew had taken refuge on the berth deck. A musket or pistol shot from the berth deck killed a British marine, William Young, who was guarding the main hatchway. The furious British crewmen then began firing through the hatchway at the Americans crowded below. Lieutenant Charles Leslie Falkiner of ''Shannon'', the leader of the boarders who had rushed the maindeck, restored order by threatening to blow out the brains of the next person to fire. He then demanded that the Americans send up the man who had killed Young, adding that ''Chesapeake'' was taken and "We have three hundred men aboard. If there is another act of hostility you will be called up on deck one by one – and shot." Falkiner was given command of ''Chesapeake'' as a British prize-vessel. ''Shannon''s midshipmen during the action were Messers, Smith, Leake, Clavering, Raymond, Littlejohn and Samwell. Samwell was the only British officer other than Broke to be wounded in the action; he was to die from an infection of his wounds some weeks later. Mr Etough was the acting master, and conned the ship into the action. Shortly after ''Chesapeake'' had been secured, Broke fainted from loss of blood and was rowed back to ''Shannon'' to be attended to by the ship's surgeon. The engagement had lasted just ten minutes according to ''Shannon''s log, or eleven minutes by Lieutenant Wallis' watch. Broke more modestly claimed fifteen minutes in his official despatch. ''Shannon'' had lost 23 men killed, and had 56 wounded. ''Chesapeake'' had about 48 killed, including four lieutenants, the master and many other of her officers, and 99 wounded. ''Shannon'' had been hit by a total of 158 projectiles, ''Chesapeake'' by 362 (these figures include grapeshot). In the time the batteries of both ships were firing, the Americans had been exposed to 44 roundshot, whilst the British had received 10 or 11 in reply (these are figures for shot which would have produced casualties or material damage; some of ''Chesapeake''s shot was fired low, bouncing off ''Shannon''s side at waterline level). Even before being boarded, ''Chesapeake'' had lost the gunnery duel by a considerable margin.

A large cask of un-slaked

The engagement had lasted just ten minutes according to ''Shannon''s log, or eleven minutes by Lieutenant Wallis' watch. Broke more modestly claimed fifteen minutes in his official despatch. ''Shannon'' had lost 23 men killed, and had 56 wounded. ''Chesapeake'' had about 48 killed, including four lieutenants, the master and many other of her officers, and 99 wounded. ''Shannon'' had been hit by a total of 158 projectiles, ''Chesapeake'' by 362 (these figures include grapeshot). In the time the batteries of both ships were firing, the Americans had been exposed to 44 roundshot, whilst the British had received 10 or 11 in reply (these are figures for shot which would have produced casualties or material damage; some of ''Chesapeake''s shot was fired low, bouncing off ''Shannon''s side at waterline level). Even before being boarded, ''Chesapeake'' had lost the gunnery duel by a considerable margin.

A large cask of un-slaked lime

Lime commonly refers to:

* Lime (fruit), a green citrus fruit

* Lime (material), inorganic materials containing calcium, usually calcium oxide or calcium hydroxide

* Lime (color), a color between yellow and green

Lime may also refer to:

Botany ...

was found open on ''Chesapeake''s forecastle, and another bag of lime was discovered in the fore-top. Some British sailors alleged the intention was to throw handfuls into the eyes of ''Shannon''s men in an unfair and dishonourable manner as they attempted to board, though that was never done by ''Chesapeake''s crew. Historian Albert Gleaves has called the allegation "absurd," noting, "Lime is always carried in ship's stores as a disinfectant, and the fact that it was left on the deck after the ship was cleared for action was probably due to the neglect of a junior, or petty, officer."

Aftermath

After the victory, a prize crew was put aboard ''Chesapeake''. The commander of the prize, Lieutenant Falkiner, had a good deal of trouble from the restive Americans, who outnumbered his own men. He had some of the leaders of the unrest transferred to ''Shannon'' in the leg-irons that had, ironically, been shipped aboard ''Chesapeake'' to deal with expected British prisoners. The rest of the American crew were rendered docile by the expedient of a carpenter cutting scuttles (holes) in the maindeck through which two 18-pounder cannon, loaded with grapeshot, were pointed at them.

''Shannon'', commanded by Lieutenant Provo Wallis, escorted her prize into Halifax, arriving there on 6 June. On the entry of the two frigates into the harbour, the naval ships already at anchor manned their yards, bands played martial music and each ship ''Shannon'' passed greeted her with cheers. The 320 American survivors of the battle were interned on Melville Island in 1813, and their ship, taken into British service and renamed HMS ''Chesapeake'', was used to ferry prisoners from Melville Island to England's

After the victory, a prize crew was put aboard ''Chesapeake''. The commander of the prize, Lieutenant Falkiner, had a good deal of trouble from the restive Americans, who outnumbered his own men. He had some of the leaders of the unrest transferred to ''Shannon'' in the leg-irons that had, ironically, been shipped aboard ''Chesapeake'' to deal with expected British prisoners. The rest of the American crew were rendered docile by the expedient of a carpenter cutting scuttles (holes) in the maindeck through which two 18-pounder cannon, loaded with grapeshot, were pointed at them.

''Shannon'', commanded by Lieutenant Provo Wallis, escorted her prize into Halifax, arriving there on 6 June. On the entry of the two frigates into the harbour, the naval ships already at anchor manned their yards, bands played martial music and each ship ''Shannon'' passed greeted her with cheers. The 320 American survivors of the battle were interned on Melville Island in 1813, and their ship, taken into British service and renamed HMS ''Chesapeake'', was used to ferry prisoners from Melville Island to England's Dartmoor Prison

HM Prison Dartmoor is a Category C men's prison, located in Princetown, high on Dartmoor in the English county of Devon. Its high granite walls dominate this area of the moor. The prison is owned by the Duchy of Cornwall, and is operated by ...

. Many officers were paroled to Halifax, but some began a riot at a performance of a patriotic song about ''Chesapeake''s defeat. Parole restrictions were tightened: beginning in 1814, paroled officers were required to attend a monthly muster on Melville Island, and those who violated their parole were confined to the prison.

Baronet

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

that September. The Court of Common Council

The Court of Common Council is the primary decision-making body of the City of London Corporation. It meets nine times per year. Most of its work is carried out by committees. Elections are held at least every four years. It is largely composed o ...

of London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

awarded him the freedom of the city

The Freedom of the City (or Borough in some parts of the UK) is an honour bestowed by a municipality upon a valued member of the community, or upon a visiting celebrity or dignitary. Arising from the medieval practice of granting respected ...

and a sword worth 100 guineas

The guinea (; commonly abbreviated gn., or gns. in plural) was a coin, minted in United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Great Britain between 1663 and 1814, that contained approximately one-quarter of an ounce of gold. The name came from t ...

. He also received a piece of plate

Plate may refer to:

Cooking

* Plate (dishware), a broad, mainly flat vessel commonly used to serve food

* Plates, tableware, dishes or dishware used for setting a table, serving food and dining

* Plate, the content of such a plate (for example: ...

worth 750 pounds and a cup worth 100 guineas. Captain Lawrence was buried in Halifax with full military honours, six British Naval Officers served as pall bearers. ''Chesapeake'', after active service in the Royal Navy, was eventually sold at Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

, England, for £500 in 1819 and broken up. Some of the timbers of ''Chesapeake'' were used in the construction of the Chesapeake Mill

The Chesapeake Mill is a watermill in Wickham, Hampshire, England. The flour mill was constructed in 1820 using the timbers of HMS ''Chesapeake'', which had previously been the United States Navy frigate . The ''Chesapeake'' was attacked and bo ...

in Wickham, Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

. ''Shannon'' was reduced to a receiving ship

A hulk is a ship that is afloat, but incapable of going to sea. Hulk may be used to describe a ship that has been launched but not completed, an abandoned wreck or shell, or to refer to an old ship that has had its rigging or internal equipmen ...

in 1831, and broken up in 1859.

In the US, the capture was seen as a humiliation, and contributed to popular sentiment against the war. Many New Englanders, now calling the conflict "Madison's war" after James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

, demanded that he resign the presidency.

In a war that reached new lows for historical accuracy sacrificed in the name of patriotic fervour, accounts of ''Shannon''s victory would be ascribed to many reasons. Very few of these took into account that Lawrence had rushed into a fight with an untrained and unprepared crew for what awaited him. Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

would later state this plainly, lambasting former American "history writers" while doing so. In less than 2 minutes ''Shannon''s crew had taken horrible losses and did not break, while ''Chesapeake''s crew did. Unfortunately for Lawrence, he did not meet an average British frigate of this point in the long wars, undermanned and with many men aboard who were not real seamen, but a frigate with a crew at the highest pitch of training, led by an expert in naval gunnery. It has been said of ''Shannon'', that "a more destructive vessel of her force had probably never existed in the history of naval warfare".

Broke never again commanded a ship. The head wound from a cutlass blow, which had exposed the brain, had been very severe accompanied by great blood loss. Therapeutic bleeding, routinely employed at the time, was not performed by ''Shannon''s surgeon Mr Alexander Jack, which was to Broke's advantage. The report of the surgeon described the wound as "a deep cut on the parietal bone, extending from the top of the head ... towards the left ear, he bonepenetrated for at least three inches in length". Broke survived the wound into moderate old age (64 years), though he was debilitated. He suffered, to a greater or lesser extent, from headaches and other neurological problems for the rest of his life. The casualties were heavy. The British lost 23 killed and 56 wounded. The Americans lost 48 killed and 99 wounded. Between the wounded of the ships' two companies, another 23 died of their wounds in the two weeks following the action. Relative to the total number of men participating, this was one of the bloodiest ship-to-ship actions of the age of sail. By comparison, suffered fewer casualties during the whole of the Battle of Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) was a naval engagement between the British Royal Navy and the combined fleets of the French and Spanish Navies during the War of the Third Coalition (August–December 1805) of the Napoleonic Wars (180 ...

. The entire action had lasted, at most, for 15 minutes, speaking to the ferocity of the fighting.

A sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

of HMS ''Shannon'' has been restored and preserved, of the ; she can be seen in a dock at Hartlepool

Hartlepool () is a seaside and port town in County Durham, England. It is the largest settlement and administrative centre of the Borough of Hartlepool. With an estimated population of 90,123, it is the second-largest settlement in County ...

in the North East of England and is the oldest British warship afloat.

In fiction

The capture of USS ''Chesapeake'' by HMS ''Shannon'' features prominently in ''The Fortune of War

''The Fortune of War'' is the sixth historical novel in the Aubrey-Maturin series by British author Patrick O'Brian, first published in 1979. It is set during the War of 1812.

HMS ''Leopard'' made its way to Botany Bay, left its prisoners, ...

'', the sixth book in the Aubrey–Maturin series

The Aubrey–Maturin series is a sequence of nautical historical novels—20 completed and one unfinished—by English author Patrick O'Brian, set during the Napoleonic Wars and centring on the friendship between Captain Jack Aubrey of the Roy ...

of historical fiction

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

novels by Patrick O'Brian

Patrick O'Brian, Order of the British Empire, CBE (12 December 1914 – 2 January 2000), born Richard Patrick Russ, was an English novelist and translator, best known for his Aubrey–Maturin series of sea novels set in the Royal Navy during t ...

, and first published in 1979. The main characters, having escaped Boston as prisoners of war, are on board the ''Shannon'' during the engagement. The battle is described with considerable accuracy by O'Brian, with his fictional characters playing only minor roles in the action.O'Brian, P. (1979) ''The Fortune of War'', Collins, London

The battle is mentioned in chapter 12 of the science fiction novel ''Starship Troopers

''Starship Troopers'' is a military science fiction novel by American writer Robert A. Heinlein. Written in a few weeks in reaction to the US suspending nuclear tests, the story was first published as a two-part serial in ''The Magazine of F ...

'' by Robert A. Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein (; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific accu ...

, and was also referred to in the novel ''Anne of the Island

''Anne of the Island'' is the third book in the ''Anne of Green Gables'' series, written by Lucy Maud Montgomery about Anne Shirley.

''Anne Of the Island'' is the third book of the eight-book sequels written by L. M. Montgomery, about Anne Shirley ...

'' by Lucy Maud Montgomery

Lucy Maud Montgomery (November 30, 1874 – April 24, 1942), published as L. M. Montgomery, was a Canadian author best known for a collection of novels, essays, short stories, and poetry beginning in 1908 with '' Anne of Green Gables''. She ...

.

See also

* USRC ''Surveyor'', captured on the same dayNotes

References

Bibliography

* * * * Brown, Anthony G., and White, Colin (2006) ''The Patrick O'Brian Muster book: persons, animals, ships and cannon in the Aubrey-Maturin sea novels''. McFarland & Co. * Cray, Robert E. "Remembering the USS Chesapeake: The politics of maritime death and impressment." ''Journal of the Early Republic'' (2005) 25#3 pp: 445–474online

* * * * * * James, William, and Chamier, Frederick (1837) ''The Naval History of Great Britain, from the Declaration of War by France in 1793, to the Accession of George IV,'' Vol VI. Richard Bentley, London. * Lambert, Andrew (2012) ''The Challenge: Britain Against America in the Naval War of 1812'', Faber and Faber, London. * * * * Pullen, Hugh Francis. ''The Shannon and the Chesapeake'' (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1970) * * * * * Voelcker, Tim (2013) ''Broke of the Shannon: and the War of 1812'', Seaforth Publishing , 9781473831322 *

External links

{{good articleChesapeake Chesapeake often refers to:

*Chesapeake people, a Native American tribe also known as the Chesepian

* The Chesapeake, a.k.a. Chesapeake Bay

*Delmarva Peninsula, also known as the Chesapeake Peninsula

Chesapeake may also refer to:

Populated plac ...

1813 in the United States

Maritime incidents in 1813

Chesapeake Chesapeake often refers to:

*Chesapeake people, a Native American tribe also known as the Chesepian

* The Chesapeake, a.k.a. Chesapeake Bay

*Delmarva Peninsula, also known as the Chesapeake Peninsula

Chesapeake may also refer to:

Populated plac ...

Military history of Nova Scotia

Chesapeake Chesapeake often refers to:

*Chesapeake people, a Native American tribe also known as the Chesepian

* The Chesapeake, a.k.a. Chesapeake Bay

*Delmarva Peninsula, also known as the Chesapeake Peninsula

Chesapeake may also refer to:

Populated plac ...

Chesapeake Chesapeake often refers to:

*Chesapeake people, a Native American tribe also known as the Chesepian

* The Chesapeake, a.k.a. Chesapeake Bay

*Delmarva Peninsula, also known as the Chesapeake Peninsula

Chesapeake may also refer to:

Populated plac ...

History of the Royal Navy

June 1813 events