Battle of Bloody Brook on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Battle of Bloody Brook was fought on September 28, 1675 (September 18, 1675 OS) between an indigenous war party primarily composed of

Although an anti-Kanienkehaka alliance with the Pocumtuc,

Although an anti-Kanienkehaka alliance with the Pocumtuc,

Even when the Pocumtuc were at full-strength, their Agawam and Norwottuck neighbors were already bargaining their independence with the English through land transactions. However, these agreements are better interpreted as "joint use" agreements, reserving rights for harvesting game, wood, and corn from pre-existing cornfields, and to even set up

Even when the Pocumtuc were at full-strength, their Agawam and Norwottuck neighbors were already bargaining their independence with the English through land transactions. However, these agreements are better interpreted as "joint use" agreements, reserving rights for harvesting game, wood, and corn from pre-existing cornfields, and to even set up

The Wampanoag sachem

The Wampanoag sachem

In September 1675, indigenous warriors were increasingly active in the Connecticut River valley. In early September, indigenous forces conducted two raids the English village of Deerfield at

In September 1675, indigenous warriors were increasingly active in the Connecticut River valley. In early September, indigenous forces conducted two raids the English village of Deerfield at

Mosely and the survivors retired to Deerfield at nightfall, where they were apparently taunted by the victorious warriors. Deerfield was fully abandoned by the English three days after the battle, with Mosely relocating his forces to garrison Hatfield, bringing with him Deerfield's garrison and inhabitants, while Major Treat's troops garrisoned Northampton and Northfield. Metacomet's forces continued their momentum by the sieging and burning Springfield to the ground, leading to the replacement of Major Pynchon by Major Appleton. In light of Bloody Brook and the Connecticut River Campaign, the subsequent Massachusetts's General Court in October 1675 committed several changes to the militia structure- converting all

Mosely and the survivors retired to Deerfield at nightfall, where they were apparently taunted by the victorious warriors. Deerfield was fully abandoned by the English three days after the battle, with Mosely relocating his forces to garrison Hatfield, bringing with him Deerfield's garrison and inhabitants, while Major Treat's troops garrisoned Northampton and Northfield. Metacomet's forces continued their momentum by the sieging and burning Springfield to the ground, leading to the replacement of Major Pynchon by Major Appleton. In light of Bloody Brook and the Connecticut River Campaign, the subsequent Massachusetts's General Court in October 1675 committed several changes to the militia structure- converting all

Pocumtuc was resettled and officially renamed as Deerfield by the English nearly a decade later. In 1691, 150 Pocumtuc refugees returned to their homeland at the invitation of Massachusetts colonial leaders, on the condition that they avoid warfare. English settlers sought a buffer of friendly indigenous people to help guard against French & Indigenous attacks from the north. However, the Pocumtuc were subject to duplicitous deals regarding land rights and tit-for-tat

Pocumtuc was resettled and officially renamed as Deerfield by the English nearly a decade later. In 1691, 150 Pocumtuc refugees returned to their homeland at the invitation of Massachusetts colonial leaders, on the condition that they avoid warfare. English settlers sought a buffer of friendly indigenous people to help guard against French & Indigenous attacks from the north. However, the Pocumtuc were subject to duplicitous deals regarding land rights and tit-for-tat

File:Grave marker near Bloody Brook Monument - South Deerfield, MA - DSC07431.JPG, First known memorial to the Battle of Bloody Brook.

File:Bloody Brook Monument. South Deerfield, MA.JPG, The second monument, completed in 1838.

The most prominent interpretations of Deerfield's colonial history are by the prolific Deerfield historian George Sheldon, whose works were largely written in the backdrop of the " Indian Question". Bruchac argues that Sheldon "used bloody examples from Deerfield’s history as a rhetorical device to paint the Pocumtuck Indians and, by extension, all Native people as inherently dangerous and untrustworthy. He clearly strove to retain his privileged position as an interlocutor of both Native and English history without being bothered by Indian sympathizers."

Historian Barry O'Connell notes that in Sheldon's time, there was a rise in contemporaneous missionaries and social reformers who were examining “not only about Euro-Americans’ treatment of Indians in the past but also about what was being done in the late nineteenth century.” Subsequently, Bruchac argues that Sheldon's writings were influenced by the political climate of his time, in advocating the benefits of Indigenous removal in light of Deerfield's involvement in wars with indigenous peoples.

Contemporaneously, Sheldon was accused by Josiah Temple, his co-author for the History of Northfield, of biased interpretations of indigenous history, and for excluding Dutch and Kanienkehaka testimony in the New York colonial documents, which suggested English involvement in rupturing Pocumtuc/Kanienkehaka diplomatic relations.

Despite the lengthy documentation of diverse interactions between colonial English and indigenous peoples before Bloody Brook, and the many documented visits of Pocumtuc descendants revisiting Deerfield, Sheldon in 1886 surmised Anglo-Pocumtuc history and the Connecticut River Campaign in Deerfield under the framework of the "vanishing Indian":

The most prominent interpretations of Deerfield's colonial history are by the prolific Deerfield historian George Sheldon, whose works were largely written in the backdrop of the " Indian Question". Bruchac argues that Sheldon "used bloody examples from Deerfield’s history as a rhetorical device to paint the Pocumtuck Indians and, by extension, all Native people as inherently dangerous and untrustworthy. He clearly strove to retain his privileged position as an interlocutor of both Native and English history without being bothered by Indian sympathizers."

Historian Barry O'Connell notes that in Sheldon's time, there was a rise in contemporaneous missionaries and social reformers who were examining “not only about Euro-Americans’ treatment of Indians in the past but also about what was being done in the late nineteenth century.” Subsequently, Bruchac argues that Sheldon's writings were influenced by the political climate of his time, in advocating the benefits of Indigenous removal in light of Deerfield's involvement in wars with indigenous peoples.

Contemporaneously, Sheldon was accused by Josiah Temple, his co-author for the History of Northfield, of biased interpretations of indigenous history, and for excluding Dutch and Kanienkehaka testimony in the New York colonial documents, which suggested English involvement in rupturing Pocumtuc/Kanienkehaka diplomatic relations.

Despite the lengthy documentation of diverse interactions between colonial English and indigenous peoples before Bloody Brook, and the many documented visits of Pocumtuc descendants revisiting Deerfield, Sheldon in 1886 surmised Anglo-Pocumtuc history and the Connecticut River Campaign in Deerfield under the framework of the "vanishing Indian":

Bloody Brook Mass Grave

WeRelate: Battle of Bloody Brook

{{DEFAULTSORT:Battle Of Bloody Brook 1675 in Massachusetts 1675 in the Thirteen Colonies Battles in Massachusetts Bloody Brook Conflicts in 1675 Deerfield, Massachusetts English colonization of the Americas History of Franklin County, Massachusetts Bloody Brook

Pocumtuc

The Pocumtuc (also Pocomtuck or Deerfield Indians) were a Native American tribe historically inhabiting western areas of Massachusetts.

Settlements

Their territory was concentrated around the confluence of the Deerfield and Connecticut Rivers ...

warriors and other local indigenous people from the central Connecticut River valley

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges at Long Island ...

, and the English colonial militia of the New England Confederation

The United Colonies of New England, commonly known as the New England Confederation, was a confederal alliance of the New England colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, Saybrook (Connecticut), and New Haven formed in May 1643. Its primary purp ...

and their Mohegan

The Mohegan are an Algonquian Native American tribe historically based in present-day Connecticut. Today the majority of the people are associated with the Mohegan Indian Tribe, a federally recognized tribe living on a reservation in the easte ...

allies during King Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1676 between indigenous inhabitants of New England and New England coloni ...

.

The crop fields of the Pocumtuc and other Connecticut River valley nations were desired by the English, however the Pocumtuc in particular were resistant to ceding their land. The Pocumtuc were the dominant power in the central Connecticut river valley, orchestrating powerful alliances and forcing the English-allied Mohegans into tribute. However, after a 1664 war with the Kanienkehaka (Mohawk) fractured both nations and destabilized the region, the Pocumtuc were compelled to begin selling land.

Subsequently, the Connecticut River valley would represent the western border of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

. However, English involvement in the Pocumtuc-Kanienkehaka war, and subsequent dealings in obtaining Pocumtuc land, contributed to local and region-wide resentment against English inhabitation of New England. Although the English were tolerated, the Pocumtuc Confederacy quickly joined Metacomet's forces at the outbreak of King Philip's War.

In the early stages of King Philip's War, English forces in the Southern Theatre experienced many smaller defeats on the western frontline, which sent the English scrambling to reinforce their settlements in the Connecticut River valley. Looking to act defensively in this Connecticut River campaign, the English set out to gather the considerable amount of corn grown at Pocumtuc ( Deerfield) to feed their garrisons.

Led by Pocumtuc sachem

Sachems and sagamores are paramount chiefs among the Algonquians or other Native American tribes of northeastern North America, including the Iroquois. The two words are anglicizations of cognate terms (c. 1622) from different Eastern Al ...

Sangumachu, the Pocumtuc Confederacy was reinforced by their Nipmuc

The Nipmuc or Nipmuck people are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who historically spoke an Eastern Algonquian language. Their historic territory Nippenet, "the freshwater pond place," is in central Massachusetts and nearby part ...

and Wampanoag

The Wampanoag , also rendered Wôpanâak, are an Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands based in southeastern Massachusetts and historically parts of eastern Rhode Island,Salwen, "Indians of Southern New England and Long Island," p. 17 ...

allies. The Indigenous war party ambushed and annihilated a company of militia escorting a train of wagons carrying the harvest from Pocumtuc to Hadley in the Connecticut River valley, killing at least 58 militia men and 16 teamsters. A short while after, this was followed by an extended battle against waves of pro-English reinforcements.

The battle had a significant impact on English consciousness in the war. This major defeat amongst others elicited aggressive responses by the English, such as a preventive war

A preventive war is a war or a military action which is initiated in order to prevent a belligerent or a neutral party from acquiring a capability for attacking. The party which is being attacked has a latent threat capability or it has shown t ...

against the Narragansett that winter, and the 1676 Peskeompscut Massacre, which ended Indigenous dominance of the Connecticut River valley. Pocumtuc refugees fled to New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

and the Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (''Wabenaki, Wobanaki'', translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner") is a North American First Nations and Native American confederation of four principal Eastern Algonquian nations: the Miꞌkmaq, Maliseet ( ...

. Bloody Brook was particularly commemorated by Euro-American

European Americans (also referred to as Euro-Americans) are Americans of European ancestry. This term includes people who are descended from the first European settlers in the United States as well as people who are descended from more recent Eu ...

residents of Massachusetts in the 1800s.

Background

Context

The centralConnecticut River valley

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges at Long Island ...

was primarily inhabited by agriculturalist eastern Algonquian peoples

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

* Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

*Eastern Air L ...

, namely the Pocumtuc

The Pocumtuc (also Pocomtuck or Deerfield Indians) were a Native American tribe historically inhabiting western areas of Massachusetts.

Settlements

Their territory was concentrated around the confluence of the Deerfield and Connecticut Rivers ...

, Agawam, Woronoco, Norwottuck (Nonotuck), Sokoki

The Missiquoi (or the Missisquoi or the Sokoki) were a historic band of Abenaki Indigenous peoples from present-day southern Quebec and formerly northern Vermont. This Algonquian-speaking group lived along the eastern shore of Lake Champlain at ...

and Quabog. Together, these nations have been antiquatedly referred to as "River Indians", with the first five being sometimes referred to as the Pocumtuc Confederacy.

Although related linguistically, the nations of the central Connecticut River valley operated their trade and diplomacy autonomously, participated in far-reaching intertribal alliances, and transacted agreements that preserved traditional access to natural resources. When relations with their neighbors (such as the English) failed, tribes drew upon existing alliances to seek refuge in friendly villages. Material and social interactions aside, alliances were customarily encoded by the exchange of the spiritually/politically significant wampum

Wampum is a traditional shell bead of the Eastern Woodlands tribes of Native Americans. It includes white shell beads hand-fashioned from the North Atlantic channeled whelk shell and white and purple beads made from the quahog or Western Nort ...

. Among the strongest peoples were the Pocumtuc and Norwottuck, whose independence & extensive alliances limited English settlement in the valley.

Around the time of King Philip's War, the nations were organized into villages of about 500 people, with an approximate total population of 5,000 Indigenous people in the central valley. Pre-contact sites were already cleared and planted with corn

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

on rich alluvial flatlands, which proved desirable to the newly arrived English settlers. Several fortified settlements were of particular importance- the Norwottuck fort, located on a high bluff above the Connecticut River in the Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England; ...

- Hadley- Hatfield triangle, and the Agawam fort on Long Hill just south of Springfield

Springfield may refer to:

* Springfield (toponym), the place name in general

Places and locations Australia

* Springfield, New South Wales (Central Coast)

* Springfield, New South Wales (Snowy Monaro Regional Council)

* Springfield, Queenslan ...

housed some 80 to 100 families combined, with the Pocumtuc fort in present-day Deerfield also being noteworthy.

In contrast, the total population of the seven small English towns spread along the 66 miles of the mid-Connecticut River valley (the western border of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

) was approximately 350 men and women, and roughly 1,100 children.

Tensions between Pocumtuc & English

Pocumtuc dominance

During the 1630s, the Connecticut River valley nations invited the English to the valley for trade. They set up accounts with fur trader and land brokerWilliam Pynchon

William Pynchon (October 11, 1590 – October 29, 1662) was an English colonist and fur trader in North America best known as the founder of Springfield, Massachusetts, USA. He was also a colonial treasurer, original patentee of the Massachu ...

, along with his son John Pynchon, and other associate traders to purchase cloth and other goods in exchange for corn and beaver fur. Wampum beads were also used by colonial settlers as a means of monetary exchange. These connections soon proved fruitful for the English, with bushels of Pocumtuc corn saving the Connecticut Colony from famine in 1638.

The Pocumtuc nation was centered on either side of the sandy banks of the Connecticut river

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges at Long Island ...

in present-day Deerfield and Greenfield

Greenfield or Greenfields may refer to:

Engineering and Business

* Greenfield agreement, an employment agreement for a new organisation

* Greenfield investment, the investment in a structure in an area where no previous facilities exist

* Greenf ...

. Despite their friendly trade relations, the Pocumtuc were respected as a powerful force by the English. The New England Confederation paid particularly close attention to Pocumtuc hostilities against the Mohegans

The Mohegan are an Algonquian Native American tribe historically based in present-day Connecticut. Today the majority of the people are associated with the Mohegan Indian Tribe, a federally recognized tribe living on a reservation in the easte ...

and Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United Sta ...

nations for fear these would impact the English colonies. The Mohegans under their sachem Uncas

Uncas () was a ''sachem'' of the Mohegans who made the Mohegans the leading regional Indian tribe in lower Connecticut, through his alliance with the New England colonists against other Indian tribes.

Early life and family

Uncas was born n ...

had separated from their Indigenous neighbors and aligned themselves with the English in Connecticut. Although an English threat of intervention averted a Pocumtuc invasion in 1648, by the late 1650's the Pocumtuc had weakened the Mohegans to the point of tribute. New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

and Massachusetts colonial leaders feared that the Pocumtuc posed a serious threat to long-term English settlement due to their powerful and extensive alliances.

Kanienkehaka War & decline

Although an anti-Kanienkehaka alliance with the Pocumtuc,

Although an anti-Kanienkehaka alliance with the Pocumtuc, Sokoki

The Missiquoi (or the Missisquoi or the Sokoki) were a historic band of Abenaki Indigenous peoples from present-day southern Quebec and formerly northern Vermont. This Algonquian-speaking group lived along the eastern shore of Lake Champlain at ...

, Pennacook

The Pennacook, also known by the names Penacook and Pennacock, were an Algonquian-speaking Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands who lived in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and southern Maine. They were not a united tribe but a netwo ...

, Kennebec Abenaki, Mohicans

The Mohican ( or , alternate spelling: Mahican) are an Eastern Algonquian Native American tribe that historically spoke an Algonquian language. As part of the Eastern Algonquian family of tribes, they are related to the neighboring Lenape, who ...

, French Jesuit missionaries and the Narragansett was formed in 1650, friendly relations were restored with the Kanienkehaka (Mohawks) by the late 1650's. The English had refused to join this alliance, not only due to fear of Kanienkehaka raids, but also because the eventual desire to lure away the Kanienkehaka and wider Haudenosaunee

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Indigenous confederations in North America, confederacy of First Nations in Canada, First Natio ...

fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

from the New Netherlands

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva P ...

. However, tit-for-tat attacks between the Kanienkehaka and Sokoki was dragging the Sokoki's Pocumtuc allies into war. European intervention included a 1663 letter by John Pynchon writing to the Dutch & Kanienkehaka absolving New England's Pocumtuc Confederacy trading partners, with the Dutch brokering an initial peace accord between the Kanienkehaka and the Connecticut River valley nations in May 1664, with a primary objective freeing Kanienkehaka captives taken by the Sokoki and being held by the Pocumtuc.

Almost simultaneously in May 1664, some of John Pynchon’s primary sub-traders (David Wilton, Henry Clark, Thomas Clarke and Joseph Parsons), rode up from Northampton to deliver a message- if these differences with the Kanienkehaka could not be settled, the English would have no alternative but to force the Pocumtuc to leave the valley. Some of these sub-traders were also present in the ensuing negotiations between Dutch, Kanienkehaka and Mohican emissaries, potentially as translators. Thereafter, the emissaries were escorted out of Pocumtuc territory, and promised to return to provide a wampum tribute to seal the peace. However the Kanienkehaka sachem Saheda and other Kanienkehaka ambassadors were killed a month later in Pocumtuc territory whilst en route to delivering the wampum . A retaliatory Kanienkehaka attack in February 1665 killed the Pocumtuc sachem Onapequin and his family, and destroyed the Pocumtuc fort.

In February 1665, John Winthrop Jr.

John Winthrop the Younger (February 12, 1606 – April 6, 1676) was an List of colonial governors of Connecticut, early governor of the Connecticut Colony, and he played a large role in the merger of several separate settlements into the unif ...

told Roger Williams

Roger Williams (21 September 1603between 27 January and 15 March 1683) was an English-born New England Puritan minister, theologian, and author who founded Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation ...

that the Kanienkehaka had killed Onapequin by mistake and that Pocumtuc had fled to Norwottuck seeking assistance. By July of 1665, Winthrop Jr. reported that a multitude of Indigenous people were at arms, ''“all in a combination from Hudson’s River to Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

,”'' as this incident rippled across the region. Pynchon may have been disinclined to broker peace as in September 1664, the Dutch relinquished New Netherlands

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva P ...

to the English, and subsequently a deal was signed on the 24th of September 1664, between Kanienkehaka & Seneca

Seneca may refer to:

People and language

* Seneca (name), a list of people with either the given name or surname

* Seneca people, one of the six Iroquois tribes of North America

** Seneca language, the language of the Seneca people

Places Extrat ...

authorities and English officials in Fort Amsterdam

Fort Amsterdam was a fort on the southern tip of Manhattan at the confluence of the Hudson and East rivers. It was the administrative headquarters for the Dutch and then English/British rule of the colony of New Netherland and subsequently the ...

(New York), in the aftermath of Saheda's death.

The deal promised no assistance for the Pocumtuc and their Sokoki

The Missiquoi (or the Missisquoi or the Sokoki) were a historic band of Abenaki Indigenous peoples from present-day southern Quebec and formerly northern Vermont. This Algonquian-speaking group lived along the eastern shore of Lake Champlain at ...

and Pennacook

The Pennacook, also known by the names Penacook and Pennacock, were an Algonquian-speaking Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands who lived in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and southern Maine. They were not a united tribe but a netwo ...

allies, along with safe refuge for the Kanienkehaka should they lose a conflict against either three nations. The death of Saheda, in particular, was held up as a reason for English leaders to form a new alliance with the Kanienkehaka and Mohicans against the Connecticut River valley nations. In effect, the deal secured the Kanienkehaka peoples' southern flanks by incorporating the Mohicans in the new alliance, and safeguarded powder and shot sales from New York traders, while securing safe access to the newly acquired lucrative Hudson Valley

The Hudson Valley (also known as the Hudson River Valley) comprises the valley of the Hudson River and its adjacent communities in the U.S. state of New York. The region stretches from the Capital District including Albany and Troy south to ...

fur trade for Pynchon and his sub-traders, and redirecting Kanienkehaka retribution towards the Pocumtuc and their allies.

Before the transfer from Dutch to English administration, Dutch Commissary Gerrit Slichtenhorst heard the Kanienkehaka sachem Cajadogo’s testimony in Fort Orange's Court ( Albany) that John Pynchon and his associates had orchestrated Saheda’s murder: ''. . . the English have told and directed the savages, to fight or kill the Dutch and Mohawks and the English have threatened, if you do not do as we tell you, we shall kill you. They say also, that 40 ships shall come across the sea to make war here and ask for the surrender of this country and if we were not willing to give it up, they intend to kill us all together . . . They say further, that at the time when the messengers of the Mohawks had come to the fort of the Pocumtuc savages to confirm the peace, several Englishmen were in the fort, who rgedthe savages to kill the Mohawks and they are dead now.''Pynchon denied this account, claiming that Clarke and Wilton were at the fort to make peace. New Netherlands Governor

Peter Stuyvesant

Peter Stuyvesant (; in Dutch also ''Pieter'' and ''Petrus'' Stuyvesant, ; 1610 – August 1672)Mooney, James E. "Stuyvesant, Peter" in p.1256 was a Dutch colonial officer who served as the last Dutch director-general of the colony of New Net ...

suspected that the story might have been fabricated to secure a Dutch alliance, but the records are not entirely clear. Regardless, John Pynchon & the English were well positioned to take advantage of this significant reversal in Pocumtuc fortunes. Conversely, English involvement in the Pocumtuc-Kanienkehaka war, interference with indigenous diplomacy, extrajudicial appointments of sachems

Sachems and sagamores are paramount chiefs among the Algonquians or other Native American tribes of northeastern North America, including the Iroquois. The two words are anglicizations of cognate terms (c. 1622) from different Eastern Algon ...

, and subsequent opportunism in obtaining Pocumtuc land left lingering resentments which, compounding with other conflicts in New England, contributed to the outbreak of hostilities in King Philip's War.

Land transactions

Even when the Pocumtuc were at full-strength, their Agawam and Norwottuck neighbors were already bargaining their independence with the English through land transactions. However, these agreements are better interpreted as "joint use" agreements, reserving rights for harvesting game, wood, and corn from pre-existing cornfields, and to even set up

Even when the Pocumtuc were at full-strength, their Agawam and Norwottuck neighbors were already bargaining their independence with the English through land transactions. However, these agreements are better interpreted as "joint use" agreements, reserving rights for harvesting game, wood, and corn from pre-existing cornfields, and to even set up wigwams

A wigwam, wickiup, wetu (Wampanoag), or wiigiwaam (Ojibwe, in syllabics: ) is a semi-permanent domed dwelling formerly used by certain Native American tribes and First Nations people and still used for ceremonial events. The term ''wickiup'' ...

on the town common, with some parcels being "sold" multiple times.

Nevertheless, the Pocumtuc were not as initially inclined to cede land to the English settlers as other nations. However, after the Kanienkehaka War and the destruction of Pocumtuc fort, English settlers from Dedham were empowered by Pynchon to negotiate buy-outs with Pocumtuc survivors. A 1665 survey by Joshua Fisher, drawn up before the land was even sold, appears to preserve usufruct rights, however made no mention of Indigenous presence. This is despite the existing Pocumtuc planting fields, wigwam

A wigwam, wickiup, wetu (Wampanoag), or wiigiwaam (Ojibwe, in syllabics: ) is a semi-permanent domed dwelling formerly used by certain Native American tribes and First Nations people and still used for ceremonial events. The term ''wickiup'' ...

sites, burial grounds, and trails, with Fisher instead depicting 8000 acres of empty land. Noting this, Margaret Bruchac states that "''it’s doubtful that the English actually intended to honor Native rights in the long run''".

A Quabog deed with the English in 1665 reflected this transition, making no provision for continued Indigenous use of the land and resources. It does, however, 'highlight shared tribal interests''wampum

Wampum is a traditional shell bead of the Eastern Woodlands tribes of Native Americans. It includes white shell beads hand-fashioned from the North Atlantic channeled whelk shell and white and purple beads made from the quahog or Western Nort ...

to manufacture at least 100 wampum belts. Bruchac argues that the wampum generated from these sales may have been particularly attractive to the Pocumtuc, in their desire to exchange them as tributes of peace with the Kanienkehaka, contributing to the repair of Pocumtuc-Kanienkehaka relations in subsequent years. This may have been a significant factor behind the shift in the Pocumtuc's strategy, as four subsequent land deeds were signed in quick succession between 1667 and 1674, with at least two directly dealt to John Pynchon also neglecting traditional rights.King Philip's War & Connecticut River Campaign

The Wampanoag sachem

The Wampanoag sachem Metacomet

Metacomet (1638 – August 12, 1676), also known as Pometacom, Metacom, and by his adopted English name King Philip,King Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1676 between indigenous inhabitants of New England and New England coloni ...

raged across the Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island colonies, with the Narragansett joining after the Great Swamp Fight

The Great Swamp Fight or the Great Swamp Massacre was a crucial battle fought during King Philip's War between the colonial militia of New England and the Narragansett people in December 1675. It was fought near the villages of Kingston and W ...

. John Pynchon, now a Major and commander-in-chief of the Connecticut River campaign, had hoped that the Connecticut River valley peoples would not join the war due to a lack of support from the Kanienkehaka (entreating that they "''not to entertain or favor''" the Pocumtuc and their allies), but this was ultimately not a deterrence.

In the aftermath of the Siege of Brookfield in the first few months of King Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1676 between indigenous inhabitants of New England and New England coloni ...

, the New England Confederation raised several companies of English militia and indigenous allies to protect the western border of the colony, as the settlements there were not able to conscript enough men for their defense. In the months of August and September in 1675, several companies from Massachusetts and Connecticut arrived to participate in the Connecticut River Campaign. These included Captain Lathrop from Essex County, Captain Mosely from Mendon, and Captain Beers from Watertown Watertown may refer to:

Places in China

In China, a water town is a type of ancient scenic town known for its waterways.

Places in the United States

*Watertown, Connecticut, a New England town

**Watertown (CDP), Connecticut, the central village ...

of the Massachusetts regiment, which was headed by Captain Appleton from Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line r ...

, and also included Major Treat of Milford Milford may refer to:

Place names Canada

* Milford (Annapolis), Nova Scotia

* Milford (Halifax), Nova Scotia

* Milford, Ontario

England

* Milford, Derbyshire

* Milford, Devon, a place in Devon

* Milford on Sea, Hampshire

* Milford, Shro ...

and Captain Mason of Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

, from the Connecticut regiment

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its capita ...

. These companies were engaged with scouting the border and guarding supplies sent to various garrisons. Some pro-English forces were first sent to Brookfield under Major Willard, then concentrated in the Hadley garrison under Major Pynchon.

By August 16, colonial militia companies had taken to the field to scout out their indigenous counterparts, with no success. Hostilities resulted in the temporary abandonment of both Indigenous and English settlements across central and southern New England. For example, English demands that the neutral Norwottuck disarm soon led to their evacuation from the area on August 24th, slipping past the English encirclement of their fort. Despite a pursuit and skirmish with the English troops under Beers and Lathrop at Hopewell Swamp, the Norwottuck escaped and joined their Pocumtuc allies to the north, with this infringement of sovereignty and attack providing the wider Pocumtuc Confederacy a firm casus belli.

Prelude

Indigenous Raids

In September 1675, indigenous warriors were increasingly active in the Connecticut River valley. In early September, indigenous forces conducted two raids the English village of Deerfield at

In September 1675, indigenous warriors were increasingly active in the Connecticut River valley. In early September, indigenous forces conducted two raids the English village of Deerfield at Pocumtuc

The Pocumtuc (also Pocomtuck or Deerfield Indians) were a Native American tribe historically inhabiting western areas of Massachusetts.

Settlements

Their territory was concentrated around the confluence of the Deerfield and Connecticut Rivers ...

, burning most of the houses, stealing multiple horse-loads of beef and pork, killing one garrison soldier & several horses, then retired to a hill nearby. The initial force likely contained around 60 warriors. When news reached Northampton, part of Lathrop's company along with volunteers from Hadley marched to Deerfield to attack the encampment with the local garrison, but found the site abandoned. The rest of Lathrop's company arrived with Mosely a couple of days later.

One day after the initial raid on Deerfield, a Pocumtuc and Nashaway The Nashaway (or Nashua or Weshacum) were a tribe of Algonquian Indians inhabiting the upstream portions of the Nashua River valley in what is now the northern half of Worcester County, Massachusetts, mainly in the vicinity of Sterling, Lancaster ...

force under Monoco

Monoco (died 1676) was a 17th-century Nashaway sachem (chief), known among the New England Puritans as One-eyed John.

After decades of peaceful coexistence, tensions arose between settlers and natives. The Nashaway attacked the neighboring Engli ...

attacked Northfield Northfield may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Northfield, Aberdeen, Scotland

* Northfield, Edinburgh, Scotland

* Northfield, Birmingham, England

* Northfield (Kettering BC Ward), Northamptonshire, England

United States

* Northfield, Connec ...

, the northernmost English settlement in the Massachusetts Bay Colony's western border, again burning most of the houses and driving away the cattle. Two days later, apparently unaware of the original assault, Beers and 20 of the 36 men in his company were ambushed and killed at Saw Mill Brook by a war party led by Monoco

Monoco (died 1676) was a 17th-century Nashaway sachem (chief), known among the New England Puritans as One-eyed John.

After decades of peaceful coexistence, tensions arose between settlers and natives. The Nashaway attacked the neighboring Engli ...

and Sagamore Sam, during an attempt to bolster the garrison at Northfield.

Major Treat, commander of the mixed English/Indigenous Connecticut regiment

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its capita ...

, having arrived at Hadley's headquarters from Hartford

Hartford is the capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. It is the core city in the Greater Hartford metropolitan area. Census estimates since the ...

mid-September, then marched to Northfield with his 100 troops. Despite a small skirmish, his company buried Beer's company and evacuated the garrison and populace there back to Hadley. After a recruiting trip, Major Treat re-fortified himself in Hadley on either the 25th or 26th of September with more Connecticut colonial troops, with Captain Mason arriving soon after with a company of Mohegan

The Mohegan are an Algonquian Native American tribe historically based in present-day Connecticut. Today the majority of the people are associated with the Mohegan Indian Tribe, a federally recognized tribe living on a reservation in the easte ...

and Pequot

The Pequot () are a Native American people of Connecticut. The modern Pequot are members of the federally recognized Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, four other state-recognized groups in Connecticut including the Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation, or th ...

warriors.

Deciding to go on the defensive by strengthening the garrisons, while also faced with a long term campaign, commanders in Hadley needing to feed ~350 colonial troops, Mohegan & Pequot allies, and refugees looked to Pocumtuc (contemporaneously also referred to as Deerfield), where settlers had managed to cut and stack a considerable quantity of corn. Orders were given to harvest and bag as much grain as could be transported.

Pocumtuc (Deerfield)

At the time of the battle, much of Pocumtuc territory was occupied by English settlers, primarily through multiple purchases of land by John Pynchon and English colonists from Dedham. The Pocumtuc nation tolerated the English occupation of their land, but their relationship evolved over the years, due to English involvement in the Kanienkehaka war and subsequent killing of their sachem Onapequin & the destruction of their fort, and land transactions stimulated by the ensuing destitution excluding traditional rights to the land. Pocumtuc (Deerfield) was on the northwestern border of Massachusetts Bay Colony, and had been inhabited by the English only two years prior to the battle. Captains Lathrop and Mosely took their militia companies north to Deerfield, to load ox carts with the corn and facilitate the eventual evacuation of civilians. While Mosely's company quartered in Deerfield and scouted the surrounding woods, Lathrop’s company, alongside carts driven by local teamsters, set out for the garrison at Hadley on the morning of September 28, 1675. The Pocumtuc sachem Sangumachu led a large war party composed of Pocumtuc, Norwottuck, Woronoco, and other local people from the Connecticut River valley, with Mattawmp, Sagamore Sam,Matoonas Matoonas (? - died 1676 in Boston) (also spelled Matonas) was a sachem of the Nipmuc Indians in the middle of 17th century. He played a significant role in the Native American uprising known as King Philip's War. Early life

Matoonas had originally c ...

and Monoco

Monoco (died 1676) was a 17th-century Nashaway sachem (chief), known among the New England Puritans as One-eyed John.

After decades of peaceful coexistence, tensions arose between settlers and natives. The Nashaway attacked the neighboring Engli ...

("One-Eyed John") leading the Nipmucs, and Anawan, Penchason and Tatason leading the Wampanoag.

Despite Mosely's scouting efforts, the war party crossed the river undetected and surveilled Lathrop's movements, keeping the English completely unaware that any sizeable force was in the area. Unlike the Connecticut Colony, the other colonies of New England did not utilize allied indigenous scouts or warriors until the final stages of the war, under Benjamin Church.

The battle

Ambush

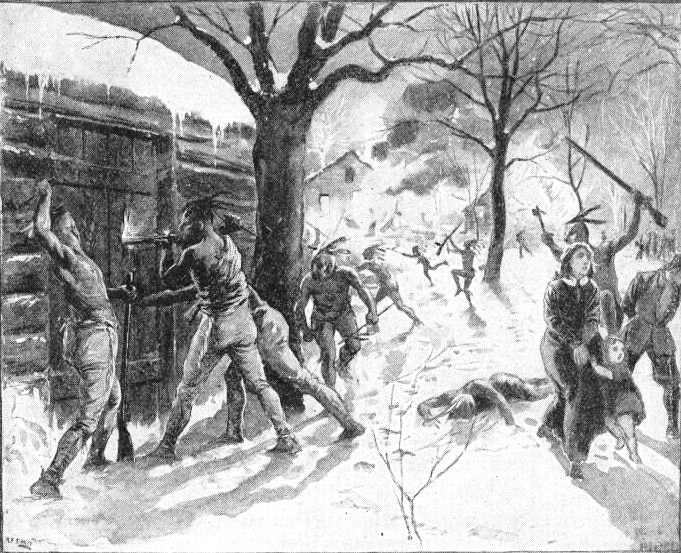

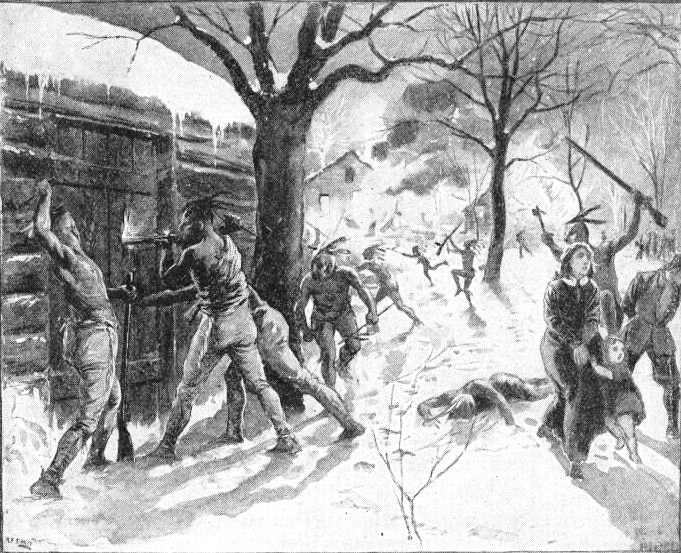

On the 28th of September 1675, a large Pocumtuc, Nipmuc, and Wampanoag force of at least several hundred warriors laid a well-planned and executed ambush on approximately 67 English militia, 17teamster

A teamster is the American term for a truck driver or a person who drives teams of draft animals. Further, the term often refers to a member of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, a labor union in the United States and Canada.

Origi ...

s from Deerfield, and their slow-moving ox carts, as they crossed Muddy Brook. The approximate site of the ambush was a gently flowing stream in a small clearing, bordered by a wet floodplain and surrounded by thickets, roughly from where they set off, in what is today South Deerfield

South Deerfield is a census-designated place (CDP) in Deerfield, Massachusetts, Deerfield, Franklin County, Massachusetts, United States. It is home to the Yankee Candle Company. At the 2010 census, the population of South Deerfield was 1,880.

S ...

. The number of warriors has been suggested to be between 500-700, but the combination of few survivors and poor record keeping makes exaggerations possible.

Apparently no flankers or vanguard

The vanguard (also called the advance guard) is the leading part of an advancing military formation. It has a number of functions, including seeking out the enemy and securing ground in advance of the main force.

History

The vanguard derives fr ...

s were organized, and it was later reported that as the heavy ox carts slowed during the stream crossing, some of the militiamen had laid their weapons in the carts and were picking wild grapes along the trail. This apparent lack of caution may have been due to an overreliance on the scouting of Mosely's company, along with the English perception that Metacomet's forces preferred to attack unsuspecting border towns and garrison houses rather than large companies of English soldiers.

By all accounts, most English participants, including all but one teamster, were dead within minutes of the attack. Deerfield historian Epaphras Hoyt suggests that the main body of English troops had crossed the brook, and were waiting for the slow moving teams of carts to negotiate the rough roads. Once encircling the entire company, the sudden first volley outright killed or disabled much of Lathrop's company.

Reinforcements

Fighting soon continued following the arrival of roughly 70 Massachusetts Bay militia under Captain Mosely from Deerfield, who are said to have repeatedly charged the much larger force in a more extended engagement, moving deep into the woods. Upon an attempted encirclement of Mosely's overextended forces, Mosely ordered aline formation

The line formation is a standard tactical formation which was used in early modern warfare.

It continued the phalanx formation or shield wall of infantry armed with polearms in use during antiquity and the Middle Ages.

The line formation provi ...

to avoid getting flanked, and initiated a cautious retreat. Finally, the arrival of 100 Connecticut colony militia under Major Treat, and 60 Mohegan

The Mohegan are an Algonquian Native American tribe historically based in present-day Connecticut. Today the majority of the people are associated with the Mohegan Indian Tribe, a federally recognized tribe living on a reservation in the easte ...

warriors under Attawamhood from Hadley forced the indigenous war party into retreat, with the battle possibly only ending at nightfall.Aftermath

Combatants

Of the original English party, all but about 10 colonists were killed, including Lathrop. One of the survivors was the chaplain of Captain Lathrop's company, Rev.Hope Atherton

Rev. Hope Atherton (1646–1677) was a colonial clergyman. He was born in Dorchester, Massachusetts. Harvard Class of 1665. He was the minister of Hadley, Massachusetts. He served as a chaplain in the King Philips War and got separated from troops ...

. Of the 17 men from Deerfield, only one survived; eight left widows and 26 children. Nothing in the written record pertains to the killed or wounded among the indigenous forces, nor how they commemorated the battle and their dead. Indigenous losses are suggested to have been heavy as a result of their engagements with Mosely, Major Treat and Attawamhood, although this is speculation- Metacomet's forces tended to carefully conceal their losses.

The next morning, Mosely's company returned to the original battleground to bury Lathrop's men, teamsters and other casualties, where they were apparently being stripped of valuables. Muddy Brook was renamed by the English as 'Bloody Brook' as a consequence of the battle. The mass grave, located along the trail south of the brook, was confirmed by 19th-century exploration.

Lathrop's men may have been contemporaneously referred by Rev. William Hubbard as the "''flower of the County of Essex''" as they mirrored the demographic norm of their society, unlike other contemporary militias which leaned on recruiting criminals and men on the fringes of society. Even so, militia conscription committees such as in Rowley Rowley may refer to:

Places Canada

* Rowley, Alberta

* Rowley Island, Nunavut

United Kingdom

* Rowley, County Durham, a hamlet

* Rowley, East Riding of Yorkshire, England

* Rowley, Shropshire, a location in Shropshire, England

* Rowley Regis, ...

still universally preferred men from non-founding families of towns, and those from the 'wrong side' of religious controversy (such as being anti-Shepard).

King Philip's War

pikemen

A pike is a very long thrusting spear formerly used in European warfare from the Late Middle Ages and most of the Early Modern Period, and were wielded by foot soldiers deployed in pike square formation, until it was largely replaced by bayonet ...

(1/3 of their force) to musketeers

A musketeer (french: mousquetaire) was a type of soldier equipped with a musket. Musketeers were an important part of early modern warfare particularly in Europe as they normally comprised the majority of their infantry. The musketeer was a pre ...

, granting autonomy to local town committees of militia, and codifying the command structure, garrison soldier duties, and regulating the conduct and discipline of active duty soldiers on campaign.

Metacomet's allied forces and their families withdrew to a winter camp in Schaghticoke, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, where Metacomet attempted to encourage the Kanienkehaka to join the war. Fearful of further defeats, colonial forces redeployed their forces from the Connecticut River Campaign and pre-emptively struck the neutral Narragansett in the winter, culminating in the Great Swamp Fight

The Great Swamp Fight or the Great Swamp Massacre was a crucial battle fought during King Philip's War between the colonial militia of New England and the Narragansett people in December 1675. It was fought near the villages of Kingston and W ...

.

Metacomet's fortunes (particularly in the Connecticut River valley) were dashed by the Kanienkehaka, who orchestrated a surprise attack on Metacomet's camp in Schaghticoke, devastating his forces. Kanienkehaka intervention in King Philip's War continued with attacks on anti-English villages and supply lines in Massachusetts. Subsequently, Metacomet re-established his base of operations in the Connecticut River valley.

This attrition compounded the growing dissatisfaction of the Connecticut River valley nations in 1676. Although buffeted by victories such as at Sudbury Sudbury may refer to:

Places Australia

* Sudbury Reef, Queensland

Canada

* Greater Sudbury, Ontario (official name; the city continues to be known simply as Sudbury for most purposes)

** Sudbury (electoral district), one of the city's federal e ...

, the sheer number of Narragansett & Wampanoag from both Schaghticoke and war-torn eastern New England severely strained the resources of the Pocumtuc Confederacy and the Nipmucs. Additionally, the failure of a speedy victory over the western English river towns as promised by Metacomet (typified by repulses at Northampton and Hatfield), the execution of the charismatic Narragansett sachem Canonchet

Canonchet (or Cononchet or Quanonchet, died April 3, 1676) was a Narragansett Sachem and leader of Native American troops during the Great Swamp Fight and King Philip's War. He was a son of Miantonomo.

Canonchet was a leader of the separatist Na ...

, and the redeployment of English forces under Major Savage to the intensifying war in the east, led to initial negotiations with Connecticut colonial authorities. Pending negotiations and Metacomet's visit to the region in response, more indigenous communities moved to fishing spots in large numbers in order to secure their provisions, relaxing their defenses and relying on opportune moments for raiding English personnel and livestock.

This vulnerability led to the final blow for the Pocumtuc Confederacy, in the form of the 1676 Peskeompscut Massacre (present-day Riverside Archeological District

The Riverside Archeological District is a historic archaeological site in Gill and Greenfield, Massachusetts. The site added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1975.

Site description

The Riverside Archeological District encompasses ...

). After a raid on Deerfield's fields dispersed 70 English cattle, Captain William Turner and his men launched a surprise retaliatory night attack at Pesekeompscut fishing village, killing 300 people (mostly women and children). Turner's settler army was routed when neighboring warriors attacked. The massacre was a turning point in King Philip's War, and with Metacomet's death in the same year, this led to the eventual expulsion of most indigenous people from the Connecticut River valley. These refugees would mostly evacuate to Schaghticoke, at the invitation of New York Governor Edmund Andros

Sir Edmund Andros (6 December 1637 – 24 February 1714) was an English colonial administrator in British America. He was the governor of the Dominion of New England during most of its three-year existence. At other times, Andros served ...

.

Further conflict

Pocumtuc was resettled and officially renamed as Deerfield by the English nearly a decade later. In 1691, 150 Pocumtuc refugees returned to their homeland at the invitation of Massachusetts colonial leaders, on the condition that they avoid warfare. English settlers sought a buffer of friendly indigenous people to help guard against French & Indigenous attacks from the north. However, the Pocumtuc were subject to duplicitous deals regarding land rights and tit-for-tat

Pocumtuc was resettled and officially renamed as Deerfield by the English nearly a decade later. In 1691, 150 Pocumtuc refugees returned to their homeland at the invitation of Massachusetts colonial leaders, on the condition that they avoid warfare. English settlers sought a buffer of friendly indigenous people to help guard against French & Indigenous attacks from the north. However, the Pocumtuc were subject to duplicitous deals regarding land rights and tit-for-tat extrajudicial killings

An extrajudicial killing (also known as extrajudicial execution or extralegal killing) is the deliberate killing of a person without the lawful authority granted by a judicial proceeding. It typically refers to government authorities, whether ...

, and would be forcibly expelled from their homeland by Pynchon and Deerfield's English settlers due to prejudice. This was reinforced by an indiscriminate scalp bounty introduced in 1694 targeting all unconfined indigenous people in Massachusetts, which was exploited by Pynchon.

Although dispersed, many Pocumtuc in particular joined the victorious Abenaki

The Abenaki (Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was predom ...

in the north, with many Abenaki warriors of Pocumtuc Confederacy heritage returning to raid Deerfield with allied nations in the subsequent French and Indian wars

The French and Indian Wars were a series of conflicts that occurred in North America between 1688 and 1763, some of which indirectly were related to the European dynastic wars. The title ''French and Indian War'' in the singular is used in the U ...

.

The most prominent of these was a coalition of Kahnawake Mohawk

The Kahnawake Mohawk Territory (french: Territoire Mohawk de Kahnawake, in the Mohawk language, ''Kahnawáˀkye'' in Tuscarora) is a First Nations reserve of the Mohawks of Kahnawá:ke on the south shore of the Saint Lawrence River in Quebec, C ...

, Huron-Wendat, Abenaki

The Abenaki (Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was predom ...

, and French troops

The French Armed Forces (french: Forces armées françaises) encompass the Army, the Navy, the Air and Space Force and the Gendarmerie of the French Republic. The President of France heads the armed forces as Chief of the Armed Forces.

France ...

who sacked Deerfield in 1704 during Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In E ...

. As part of the French and Indian wars

The French and Indian Wars were a series of conflicts that occurred in North America between 1688 and 1763, some of which indirectly were related to the European dynastic wars. The title ''French and Indian War'' in the singular is used in the U ...

, multiple attacks took place during King William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand All ...

(most importantly in 1694), Queen Anne's War (such as 1709), and the 1746 Siege of Fort Massachusetts

The siege of Fort Massachusetts (19-20 August 1746) was a successful siege of Fort Massachusetts (in present-day North Adams, Massachusetts) by a mixed force of more than 1,000 French and Native Americans from New France. The fort, garrisoned by ...

/Bars Fight

"Bars Fight" is a ballad poem written by Lucy Terry about an attack upon two white families by Native Americans on August 21, 1746. The incident occurred in an area of Deerfield called "The Bars", which was a colonial term for a meadow. The p ...

in King George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in t ...

. Separately, an allied coalition under Grey Lock

Gray Lock (or Greylock, born Wawanotewat, Wawanolet, or Wawanolewat), was a Western Abenaki warrior chieftain of Woronoco/Pocumtuck ancestry who came to lead the Missisquoi Abenaki band, and whose direct descendants have led the Missisquoi Aben ...

, an Abenaki chief of Pocumtuc/Woronoco heritage, raided Deerfield in 1724 during Grey Lock's War

The western theatre of Dummer's War in the 1720s in northern New England was referred to as "Grey Lock's War". Grey Lock distinguished himself by conducting guerrilla raids into Vermont and western Massachusetts. He consistently eluded his pursu ...

.

Legacy

Monuments

The first surviving reference to a monument dates to 1728, from a journal by Dudley Woodbridge detailing his passage betweenCambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

and Deerfield. This is the earliest known reference to what is likely the oldest European-style monument to a military engagement in British North America.

The monument consisted of a tabular stone placed on a rectangular brick base. The monument was likely constructed between the 1680s and the early 1700s. By 1815, the original brick foundation Woodbridge described in his journal had disappeared completely; the table stone itself had fractured into two pieces and been moved to make room for a house. Thereafter, the table stone was transferred to the front yard of a private home, a sidewalk, and a nearby barn, until it was reset in its current location on the east side of North Main Street in South Deerfield

South Deerfield is a census-designated place (CDP) in Deerfield, Massachusetts, Deerfield, Franklin County, Massachusetts, United States. It is home to the Yankee Candle Company. At the 2010 census, the population of South Deerfield was 1,880.

S ...

.

The shaped, cut, and polished stone measures wide, long, thick, and was chiseled from local sandstone. Initially neither decorated nor inscribed, sometime between 1815 and 1826, the by then fractured table stone was altered and inscribed:“Grave of Capt. Lathrop and Men Slain by the Indians, 1675.”By 1815, an observer noted that a second monument to replace the “two rough unlettered stones, lying horizontally on the ground” had been considered, but that such efforts had been “ineffectual.” In 1835, the cornerstone for a new monument was laid in front of a 6,000 person crowd in South Deerfield, keynoted by the orator and politician

Edward Everett

Edward Everett (April 11, 1794 – January 15, 1865) was an American politician, Unitarian pastor, educator, diplomat, and orator from Massachusetts. Everett, as a Whig, served as U.S. representative, U.S. senator, the 15th governor of Massa ...

, who stated that “'' is great assembly bears witness to the emotions of a grateful posterity... On this sacred spot''”.

The monument committee eventually succeeded in fundraising the quarrying and design of a obelisk. Overseen by Deerfield historians Epaphrus Hoyt and Stephen West Williams, the monument was dedicated on August 29, 1838, and keynoted by Deerfield Academy

Deerfield Academy is an elite coeducational preparatory school in Deerfield, Massachusetts. Founded in 1797, it is one of the oldest secondary schools in the United States. It is a member of the Eight Schools Association, the Ten Schools Admissi ...

president Luther B. Lincoln. The monument is inscribed:"On this Ground Capt. THOMAS LATHROP and eighty four men under his command, including eighteen teamsters from Deerfield, conveying stores from that town to Hadley, were ambuscaded by about 700 Indians, and the Captain and seventy six men slain, September 18th 1675. ( OS) The soldiers who fell, were described by a contemporary Historian, as “''a choice Company of young men, the very flower of the County of Essex none of whom were ashamed to speak with the enemy in the gate''." "'' And Sanguinetto tells you where the dead'' '' Made the earth wet and turned the unwilling waters red.''" "The Same of the slain is marked by a Stone slab, 21 rods southerly of this monument."

Interpretations

According to Deerfield historians Barbara Mathews and Peter A. Thomas, the contrast between the first initially uninscribed memorial and its monumental replacement reflect the transition from the early English and theirCalvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

beliefs to the ideologies of neoclassical republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

, white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

and patriotism

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and sense of attachment to one's country. This attachment can be a combination of many different feelings, language relating to one's own homeland, including ethnic, cultural, political or histor ...

in the early USA.Anniversaries

Both the 100th anniversary of the start of the American Revolution and the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Bloody Brook were in 1875. The newly formed Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association and citizens of Deerfield organized a day long celebration, with a parade to the monument followed by carriages carrying event guests, dignitaries and local citizenry, and crowds of spectators lining the way. George Davis, President of the Day and one of the original members of the 1838 monument committee, delivered a lengthy address that emphasized an intrinsic link betweenKing Philip’s War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1676 between indigenous inhabitants of New England and New England coloni ...

, the war for Independence, and the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

: ''There have been three great crises in the history of this country. Of two of them this is the great bi-centennial and centennial year. The first was the Indian war of 1675, known as King Philip’s war, which was a war for physical existence; the second was a war of the Revolution, which was a war for national independence; the third was the late war of the rebellion, which was a war for continued national existence.''A second speaker, George Loring of Essex County, informed the thousands listening that the Battle of Bloody Brook's significance was as “''an incident in the infancy of a powerful nation, and one occurring at the critical period of the most important social and civil event known to man, the founding of a free republic on the western continent''.” Recognizing that Irish, eastern European, and other relatively recent newcomers to the Valley lacked genealogical connections to this 17th-century history, Robert R. Bishop urged all to remember that the “''martyred blood at Bloody Brook should inspire us to do deeds of manly, patriotic devotion.''” The 300th year anniversary of Bloody Brook in 1975, according to Mathews and Thomas, reflected a significant change in peoples’ minds about the significance of the monument and the their relationship with history.

The connections that had seemed so clear in 1875 between the nation’s colonial past and the significance of that past to the lives of present-day Americans were actively questioned or under attack... TheCivil Rights Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...andAmerican Indian Movement The American Indian Movement (AIM) is a Native American grassroots movement which was founded in Minneapolis, Minnesota in July 1968, initially centered in urban areas in order to address systemic issues of poverty, discrimination, and police ...s were transforming the political and ideological landscape, in the process leading many Americans to question the triumphal historical narratives they had been taught... Some Deerfield residents did try to hold to tradition and attended a half-hour ceremony at the monument followed by a picnic lunch on the lawn of the nearby South Deerfield Congregational Church. But, as a reporter for the Amherst Record observed: “… ''the attraction has gone out of celebrations, in this eighth decade of the 20th Century. nlythirty five people, most of them crowned with gray or white hair, were on hand''."

Historical interpretation

Early 1800s

Professor Margaret Bruchac argues that during the early 1800s, New England’s Euro-American citizens began embracing commemorative events, such as the anniversaries of the Battle of Bloody Brook, as platforms that served as public performances of the white ownership of history and the Connecticut River valley. Such examples include Edward Everett's address on the 160th anniversary of the Battle of Bloody Brook in 1835, where Everett commemorated the ''“Indian catastrophe''”. Indigenous people had been doomed to fail, he argued, since they belonged to ''“a different variety of the species, speaking a different tongue, suffering all the disadvantages of social and intellectual inferiority.''” In particular, Everett addressed theAmherst College

Amherst College ( ) is a private liberal arts college in Amherst, Massachusetts. Founded in 1821 as an attempt to relocate Williams College by its then-president Zephaniah Swift Moore, Amherst is the third oldest institution of higher educatio ...

students and faculty in the crowd, entreating to "never forget the military struggles that had brought enlightenment and education to Deerfield".

In 1838, Luther B. Lincoln delivered another oration on the same monument site, the very place ''“where their fathers bled to secure to them the rich boon they possess.”'' Bruchac notes the dismissal of the dense evidence of indigenous horticultural industry and diplomatic relations, as well as decades of peaceful coexistence, with Lincoln instead depicting the colonial past as a place where: ''"every tree concealed an Indian; and every Indian’s hand grasped a bloody weapon; on every Indian’s face was pictured the curse of the white man; and in every Indian’s bosom a flame was kindled, to be extinguished only by the death of its victim.''"

Late 1800s

The most prominent interpretations of Deerfield's colonial history are by the prolific Deerfield historian George Sheldon, whose works were largely written in the backdrop of the " Indian Question". Bruchac argues that Sheldon "used bloody examples from Deerfield’s history as a rhetorical device to paint the Pocumtuck Indians and, by extension, all Native people as inherently dangerous and untrustworthy. He clearly strove to retain his privileged position as an interlocutor of both Native and English history without being bothered by Indian sympathizers."

Historian Barry O'Connell notes that in Sheldon's time, there was a rise in contemporaneous missionaries and social reformers who were examining “not only about Euro-Americans’ treatment of Indians in the past but also about what was being done in the late nineteenth century.” Subsequently, Bruchac argues that Sheldon's writings were influenced by the political climate of his time, in advocating the benefits of Indigenous removal in light of Deerfield's involvement in wars with indigenous peoples.

Contemporaneously, Sheldon was accused by Josiah Temple, his co-author for the History of Northfield, of biased interpretations of indigenous history, and for excluding Dutch and Kanienkehaka testimony in the New York colonial documents, which suggested English involvement in rupturing Pocumtuc/Kanienkehaka diplomatic relations.

Despite the lengthy documentation of diverse interactions between colonial English and indigenous peoples before Bloody Brook, and the many documented visits of Pocumtuc descendants revisiting Deerfield, Sheldon in 1886 surmised Anglo-Pocumtuc history and the Connecticut River Campaign in Deerfield under the framework of the "vanishing Indian":

The most prominent interpretations of Deerfield's colonial history are by the prolific Deerfield historian George Sheldon, whose works were largely written in the backdrop of the " Indian Question". Bruchac argues that Sheldon "used bloody examples from Deerfield’s history as a rhetorical device to paint the Pocumtuck Indians and, by extension, all Native people as inherently dangerous and untrustworthy. He clearly strove to retain his privileged position as an interlocutor of both Native and English history without being bothered by Indian sympathizers."

Historian Barry O'Connell notes that in Sheldon's time, there was a rise in contemporaneous missionaries and social reformers who were examining “not only about Euro-Americans’ treatment of Indians in the past but also about what was being done in the late nineteenth century.” Subsequently, Bruchac argues that Sheldon's writings were influenced by the political climate of his time, in advocating the benefits of Indigenous removal in light of Deerfield's involvement in wars with indigenous peoples.

Contemporaneously, Sheldon was accused by Josiah Temple, his co-author for the History of Northfield, of biased interpretations of indigenous history, and for excluding Dutch and Kanienkehaka testimony in the New York colonial documents, which suggested English involvement in rupturing Pocumtuc/Kanienkehaka diplomatic relations.

Despite the lengthy documentation of diverse interactions between colonial English and indigenous peoples before Bloody Brook, and the many documented visits of Pocumtuc descendants revisiting Deerfield, Sheldon in 1886 surmised Anglo-Pocumtuc history and the Connecticut River Campaign in Deerfield under the framework of the "vanishing Indian":"''A feeble remnant'' (after the Kanienkehaka war)'', renouncing their independence, sought the protection of the English . . . The enervated remains of the Pocumtuck Confederation—rebelling against English domination—appeared for a few months in Philip’s War. At its close the few miserable survivors stole away towards the setting sun and were forever lost to sight. Never again do we find in recorded history, a single page relating to the unfortunate Pocumtucks.''"

2000s

In evaluating the historiography of the colonial history of the Connecticut River valley, Bruchac states:I suggest that regional nineteenth-century historians consciously sifted the records to select historical anecdotes that emphasized Indian hostilities for dramatic impact. Their published accounts of colonial events placed white colonists at center stage and positioned indigenous people as natural antagonists and outsiders. Public renditions (monuments, speeches, historical pageantry, etc.) of this history also employed elements of nostalgia and invention. The production of history became, in this way, a method of crafting white cultural heritage by claiming the past as the collective property of non-Native settlers and their descendants. Some historians strove to minimize the influence of Native diplomacy and alliances and to downplay the intelligence of Native leaders. Others, who supported the “vanishing Indian” paradigm, tried to silence Native voices and block the potential for future Native presence by consciously crafting a definitive ending, a tragically poetic moment when all Indians in the region supposedly ceased to exist.Modern-day Deerfield historians Mathews and Thomas (affiliated with

Historic Deerfield

Historic Deerfield is a museum dedicated to the heritage and preservation of Deerfield, Massachusetts, and history of the Connecticut River Valley. Its historic houses, museums, and programs provide visitors with an understanding of New Engla ...

), noting that the 350th year anniversary of the Battle of Bloody Brook is in 2025, emphasize the need to recover and reincorporate ancestral and contemporary Indigenous and Anglo perspectives in order to allow those who interact with sites such as the Bloody Brook memorial to "actively participate in constructing nuanced, intrinsically human-centered, and relevant historical narratives."

References

*External links

Bloody Brook Mass Grave

WeRelate: Battle of Bloody Brook

{{DEFAULTSORT:Battle Of Bloody Brook 1675 in Massachusetts 1675 in the Thirteen Colonies Battles in Massachusetts Bloody Brook Conflicts in 1675 Deerfield, Massachusetts English colonization of the Americas History of Franklin County, Massachusetts Bloody Brook