Bantu Peoples Of South Africa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

South African Bantu-speaking peoples are the majority of black South Africans. Occasionally grouped as

The history of the Bantu-speaking peoples from South Africa has in the past been misunderstood due to the deliberate spreading of false narratives such as ''The Empty Land Myth''. First published by W.A. Holden in the 1860s, this doctrine claims that South Africa had mostly been an unsettled region and that Bantu-speaking peoples had begun to migrate southwards from present day

The history of the Bantu-speaking peoples from South Africa has in the past been misunderstood due to the deliberate spreading of false narratives such as ''The Empty Land Myth''. First published by W.A. Holden in the 1860s, this doctrine claims that South Africa had mostly been an unsettled region and that Bantu-speaking peoples had begun to migrate southwards from present day

After the death of the Mthethwa king Dingiswayo around 1818, at the hands of Zwide, the king of the Ndwandwe, Shaka assumed leadership of the entire Mthethwa alliance. The alliance under his leadership survived Zwide's first assault at the Battle of Gqokli Hill. Within two years he had defeated Zwide at the Battle of Mhlatuze River and broken up the Ndwandwe alliance, some of whom in turn began a murderous campaign against other Nguni communities, resulting in a mass migration of communities fleeing those who are regarded now as Zulu people too. Historians have postulated this as the cause of the Mfecane, a period of mass migration and war in the Southern African interior in the 19th, however this hypothesis is no longer accepted by most historians, and the idea itself of Mfecane/''Difaqane'' has been thoroughly disputed by many scholars, notably by Julian Cobbing.

After the death of the Mthethwa king Dingiswayo around 1818, at the hands of Zwide, the king of the Ndwandwe, Shaka assumed leadership of the entire Mthethwa alliance. The alliance under his leadership survived Zwide's first assault at the Battle of Gqokli Hill. Within two years he had defeated Zwide at the Battle of Mhlatuze River and broken up the Ndwandwe alliance, some of whom in turn began a murderous campaign against other Nguni communities, resulting in a mass migration of communities fleeing those who are regarded now as Zulu people too. Historians have postulated this as the cause of the Mfecane, a period of mass migration and war in the Southern African interior in the 19th, however this hypothesis is no longer accepted by most historians, and the idea itself of Mfecane/''Difaqane'' has been thoroughly disputed by many scholars, notably by Julian Cobbing.

The year 1994 saw the 1994 South African general election, first democratic election in South Africa, the majority of the population, Black South Africans, participating in Elections in South Africa, political national elections for the first time in what ceremonially ended the Apartheid era and also being the first time a political party in South Africa getting legitimately elected as government. The day was ideally hailed as Freedom Day (South Africa), Freedom day and the beginning of progress to the conclusion of Black South Africans existential struggle that began with European colonization in the South African region.

As a consequence of Apartheid policies, black Africans are regarded as a race group in South Africa. These groups (blacks, White South Africans, whites, Coloureds and Indians) still tend to have a strong racial identities, and to classify themselves, and others, as members of these race groups and the classification continues to persist in government policy, to an extent, as a result of attempts at redress such as Black Economic Empowerment and Affirmative action#South Africa, Employment Equity.

The year 1994 saw the 1994 South African general election, first democratic election in South Africa, the majority of the population, Black South Africans, participating in Elections in South Africa, political national elections for the first time in what ceremonially ended the Apartheid era and also being the first time a political party in South Africa getting legitimately elected as government. The day was ideally hailed as Freedom Day (South Africa), Freedom day and the beginning of progress to the conclusion of Black South Africans existential struggle that began with European colonization in the South African region.

As a consequence of Apartheid policies, black Africans are regarded as a race group in South Africa. These groups (blacks, White South Africans, whites, Coloureds and Indians) still tend to have a strong racial identities, and to classify themselves, and others, as members of these race groups and the classification continues to persist in government policy, to an extent, as a result of attempts at redress such as Black Economic Empowerment and Affirmative action#South Africa, Employment Equity.

A constructed script of featural writing system and syllabary, whose developments in 2010 was inspired by ancient ideographic traditions of the Southern African region, and its parent systems being ''Amabheqe'' ideographs and Litema. It was developed for Southern Bantu languages, ''siNtu''. The origins of ''Litema'' ornament (art), ornamental and mural art of Southern Africa stretches centuries back in time, while excavations at Sotho-Tswana archaeological sites have revealed hut floors that have survived the elements for 1500 years, the earliest intact evidence of this art stretches back from the c. 1400s.

A constructed script of featural writing system and syllabary, whose developments in 2010 was inspired by ancient ideographic traditions of the Southern African region, and its parent systems being ''Amabheqe'' ideographs and Litema. It was developed for Southern Bantu languages, ''siNtu''. The origins of ''Litema'' ornament (art), ornamental and mural art of Southern Africa stretches centuries back in time, while excavations at Sotho-Tswana archaeological sites have revealed hut floors that have survived the elements for 1500 years, the earliest intact evidence of this art stretches back from the c. 1400s.

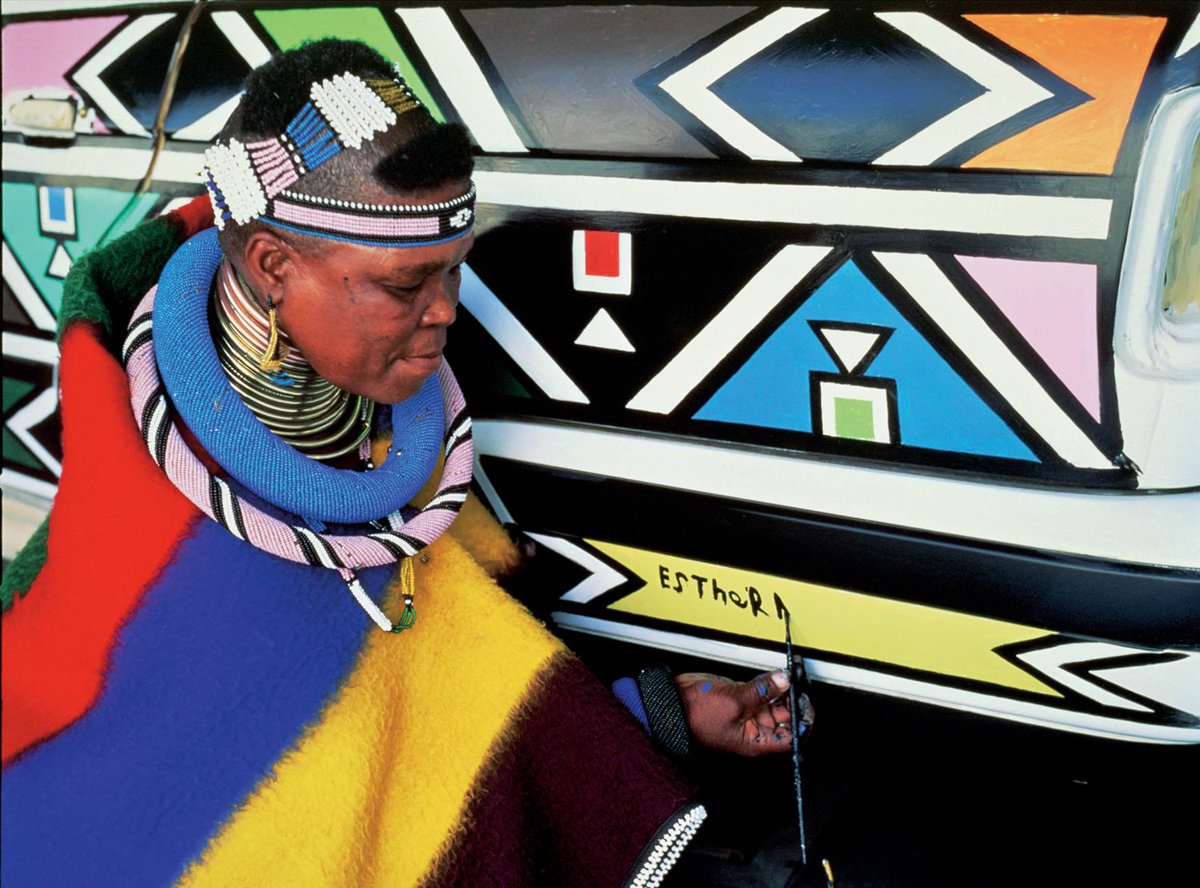

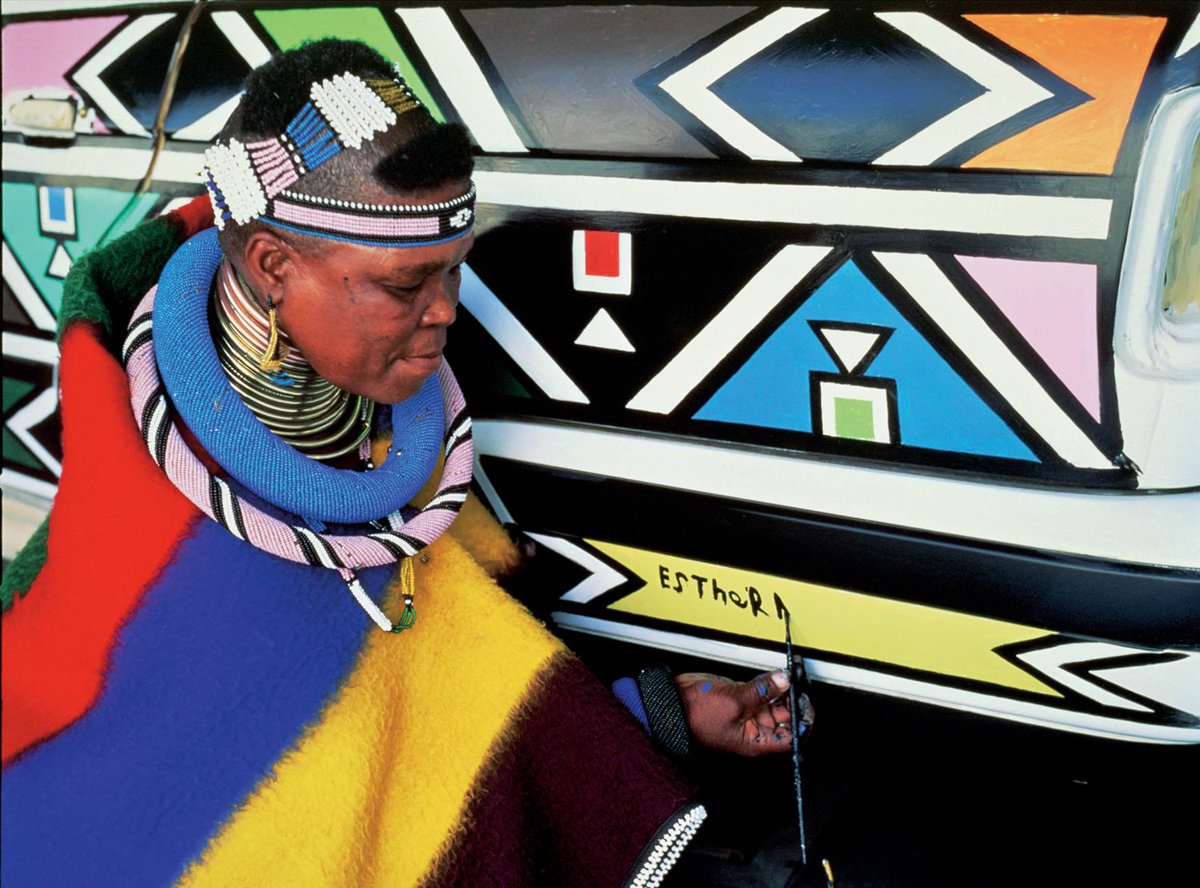

Southern Ndebele prior and during the 18th century primarily used their expressive symbols for communication, it is believed that these paintings are a synthesis of historical Nguni design traditions and Northern Sotho ''ditema'' or ''litema'' tradition(s). They also began to stand for their continuity and cultural resistance to their circumstances during the colonization in the 19th century. These wall paintings done by the women was their secret code to their people, disguised to anyone but the Southern Ndebele. The vibrant symbols and expressions portray communications of personal prayers, self-identification, values, emotions, and marriage, sometimes the male initiation but the ritual was not expressed. Religions have never been a part of the Southern Ndebele's house paintings. The women of the Southern Ndebele are often the tradition carriers and the main developer of the wall art of their home. The tradition and style of house painting is passed down in the families from generation to generation by the mothers. A well-painted home shows the female of the household is a good wife and mother. She is responsible for the painting of the outside gates, front walls, side walls, and usually the interior of her home. One thing that has changed since the beginning of the paintings and the present-day wall art is their styles. In the late 1960s, the new style was evident, what was once a finger-painted creation was now created using bundled twigs with feathers as brushes. The walls are still originally whitewashed, but the outlines and colours have significantly changed.

The patterns and symbols can be seen today with a rich black outline and a vivid colour inside. There are five main colours represented: red and dark red, yellow to gold, a sky blue, green, and sometimes pink, white is always used as the background because it makes the bright patterns stand out more. The geometric patterns and shape are first drawn with the black outline and later filled in with colour. The patterns are grouped together throughout the walls in terms of their basic design structure. Creating the right tools to allow accuracy and freedom becomes a difficult task. The tools can't restrict the painter from creating her art. They have to have tools for the large geometric shapes of flat colour and small brushes for the very small areas, outlines, and sacks. The advancement of tools has allowed faster and more complex designs throughout the Southern Ndebele's homes. Every generation passes it down and little changes become apparent.

Southern Ndebele prior and during the 18th century primarily used their expressive symbols for communication, it is believed that these paintings are a synthesis of historical Nguni design traditions and Northern Sotho ''ditema'' or ''litema'' tradition(s). They also began to stand for their continuity and cultural resistance to their circumstances during the colonization in the 19th century. These wall paintings done by the women was their secret code to their people, disguised to anyone but the Southern Ndebele. The vibrant symbols and expressions portray communications of personal prayers, self-identification, values, emotions, and marriage, sometimes the male initiation but the ritual was not expressed. Religions have never been a part of the Southern Ndebele's house paintings. The women of the Southern Ndebele are often the tradition carriers and the main developer of the wall art of their home. The tradition and style of house painting is passed down in the families from generation to generation by the mothers. A well-painted home shows the female of the household is a good wife and mother. She is responsible for the painting of the outside gates, front walls, side walls, and usually the interior of her home. One thing that has changed since the beginning of the paintings and the present-day wall art is their styles. In the late 1960s, the new style was evident, what was once a finger-painted creation was now created using bundled twigs with feathers as brushes. The walls are still originally whitewashed, but the outlines and colours have significantly changed.

The patterns and symbols can be seen today with a rich black outline and a vivid colour inside. There are five main colours represented: red and dark red, yellow to gold, a sky blue, green, and sometimes pink, white is always used as the background because it makes the bright patterns stand out more. The geometric patterns and shape are first drawn with the black outline and later filled in with colour. The patterns are grouped together throughout the walls in terms of their basic design structure. Creating the right tools to allow accuracy and freedom becomes a difficult task. The tools can't restrict the painter from creating her art. They have to have tools for the large geometric shapes of flat colour and small brushes for the very small areas, outlines, and sacks. The advancement of tools has allowed faster and more complex designs throughout the Southern Ndebele's homes. Every generation passes it down and little changes become apparent.

The most popular sporting code in South Africa and among Black South Africans is Association football with the most notable event having been hosted being the 2010 FIFA World Cup, but before such advent there are historical sports that were popular to the indigenous.

The most popular sporting code in South Africa and among Black South Africans is Association football with the most notable event having been hosted being the 2010 FIFA World Cup, but before such advent there are historical sports that were popular to the indigenous.

Essentially they consumed meat (primarily from Nguni cattle, Nguni sheep (Zulu sheep, Pedi sheep, Swazi sheep), pigs/boars and wild game hunts), vegetables, fruits, cattle and sheep milk, water, and grain beer on occasion. They began to eat the staple product of maize mid-18th century (introduced from Americas, the Americas by Portuguese in the late 17th century via the East African coast), it became favoured for its productiveness which was more than the grains of South African native grasses. There were a number of taboos regarding the consumption of meat. The well known, no meat of dogs, apes, crocodiles or snakes could be eaten. Likewise taboo was the meat of some birds, like owls, crows and vultures, as well as the flesh of certain totem animals. The Gonimbrasia belina, mopane worms are traditionally popular amongst the Tswana, Venda, Southern Ndebele, Northern Sotho and Tsonga people, though they have been successfully commercialized.

South African Bantu language speaking peoples' modern diet is largely still similar to that of their ancestors, but significant difference being in the systems of production and consumption of their food. They do take interest to innovations in foods that come their way while still practicing their very own unique food cuisine popular amongst themselves and those curious alike.

Essentially they consumed meat (primarily from Nguni cattle, Nguni sheep (Zulu sheep, Pedi sheep, Swazi sheep), pigs/boars and wild game hunts), vegetables, fruits, cattle and sheep milk, water, and grain beer on occasion. They began to eat the staple product of maize mid-18th century (introduced from Americas, the Americas by Portuguese in the late 17th century via the East African coast), it became favoured for its productiveness which was more than the grains of South African native grasses. There were a number of taboos regarding the consumption of meat. The well known, no meat of dogs, apes, crocodiles or snakes could be eaten. Likewise taboo was the meat of some birds, like owls, crows and vultures, as well as the flesh of certain totem animals. The Gonimbrasia belina, mopane worms are traditionally popular amongst the Tswana, Venda, Southern Ndebele, Northern Sotho and Tsonga people, though they have been successfully commercialized.

South African Bantu language speaking peoples' modern diet is largely still similar to that of their ancestors, but significant difference being in the systems of production and consumption of their food. They do take interest to innovations in foods that come their way while still practicing their very own unique food cuisine popular amongst themselves and those curious alike.

File:The Venda people's Mbilwe village on a rising slope as photographed in 1920s.png, Venda people's village of Mbilwe, Rondavels as its structures on a rising slope as photographed in 1923, a decade after the Natives Land Act, 1913

File:Herboude iQhugwane naby Dingaanstat-grootingang, a.jpg, A reconstruction in a heritage site of KwaZulu-Natal of the Zulu people's variation of a hut called ''iQhugwane'', which dominated as an indigenous abode during Dingane kaSenzangakhona's reign.

File:Pre-colonial indigenous South African rondavel.png, Tswana people, Bahurutshe people's homestead of veranda Rondavels pre-1822 from the ancient city of Kaditshwene (c.1400s–c.1820s).

File:Bell - Difaqane hutte.png, Early 19th century, South Africa. Bantu-speaking peoples of South Africa's variation of a hut, built on stilts, to protect themselves from lions and other predatory animals.

File:Town of hole in the wall.jpg, Modern usage of the Rondavel, residency near the coastline of Eastern Cape, South Africa.

King Shaka is well known for the many military, social, cultural and political reforms he used to create his highly organized and centralized Zulu Kingdom, Zulu state. The most important of these were the transformation of the Zulu army, army, thanks to innovative tactics and weapons he conceived, and a showdown with the spiritual leadership, limiting the power of traditional healers, and effectively ensuring the subservience of the Zulu church to the state. King Shaka integrated defeated Zulu language, Zulu-speaking tribes into the newly formed Zulu people, Zulu ethnic group, on a basis of full equality, with promotions in the army and civil service being a matter of merit rather than circumstance of birth.Guthrie M., ''Comparative Bantu. Farnboroiugh Vols. 1–4.'', Gregg International Publishers Ltd. 1967

King Shaka is well known for the many military, social, cultural and political reforms he used to create his highly organized and centralized Zulu Kingdom, Zulu state. The most important of these were the transformation of the Zulu army, army, thanks to innovative tactics and weapons he conceived, and a showdown with the spiritual leadership, limiting the power of traditional healers, and effectively ensuring the subservience of the Zulu church to the state. King Shaka integrated defeated Zulu language, Zulu-speaking tribes into the newly formed Zulu people, Zulu ethnic group, on a basis of full equality, with promotions in the army and civil service being a matter of merit rather than circumstance of birth.Guthrie M., ''Comparative Bantu. Farnboroiugh Vols. 1–4.'', Gregg International Publishers Ltd. 1967

Bantu

Bantu may refer to:

*Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

*Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

*Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

*Black Association for Nationali ...

, the term itself is derived from the word for "people" common to many of the Bantu languages

The Bantu languages (English: , Proto-Bantu: *bantʊ̀) are a large family of languages spoken by the Bantu people of Central, Southern, Eastern africa and Southeast Africa. They form the largest branch of the Southern Bantoid languages.

T ...

. The Oxford Dictionary Oxford dictionary may refer to any dictionary published by Oxford University Press, particularly:

Historical dictionaries

* ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'')

* ''Shorter Oxford English Dictionary'', abridgement of the ''OED''

Single-volume d ...

of South African English

South African English (SAfrE, SAfrEng, SAE, en-ZA) is the List of dialects of the English language, set of English language dialects native to South Africans.

History

British Empire, British settlers first arrived in the South African re ...

describes its contemporary usage in a racial context as "obsolescent and offensive" because of its strong association with white

White is the lightness, lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully diffuse reflection, reflect and scattering, scatter all the ...

minority rule with their apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

system. However, Bantu is used without pejorative connotations in other parts of Africa and is still used in South Africa as the group term for the language family.

History

The history of the Bantu-speaking peoples from South Africa has in the past been misunderstood due to the deliberate spreading of false narratives such as ''The Empty Land Myth''. First published by W.A. Holden in the 1860s, this doctrine claims that South Africa had mostly been an unsettled region and that Bantu-speaking peoples had begun to migrate southwards from present day

The history of the Bantu-speaking peoples from South Africa has in the past been misunderstood due to the deliberate spreading of false narratives such as ''The Empty Land Myth''. First published by W.A. Holden in the 1860s, this doctrine claims that South Africa had mostly been an unsettled region and that Bantu-speaking peoples had begun to migrate southwards from present day Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe (), officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country located in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Botswana to the south-west, Zambia to the north, and Mozam ...

at the same time as the Europeans had begun to move northwards from the Cape settlement, despite there being no historical or archaeological evidence to support this theory.

This theory originated in Southern Africa during the period of Colonisation of Africa, historians have noted that this theory had already gained currency among Europeans by the mid-1840s. Its later alternative form of note were conformed around the "1830s concept of Mfecane", trying to hide and ignore the intrusion of Europeans on Bantu lands, by implying that the territory they colonized was devoid of human habitation (as a result of the ''Mfecane''). Modern research has disputed this historiographical narrative. By the 1860s, when Holden was propagating his theory, this turbulent period had resulted in large swathes of South African land falling under the control of either the Boer Republics or British colonials, there was denaturalization accompanied with forced displacement and population transfer of these indigenous peoples from their land, the myth being used as the justification for the capture and settlement of Bantu-speaking peoples's land. The Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa ( nl, Unie van Zuid-Afrika; af, Unie van Suid-Afrika; ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the Cape, Natal, Tran ...

established rural reserves in 1913 and 1936, by legislating the reduction and voiding of ''South African Bantu-speaking peoples's'' land heritage holistically

Holism () is the idea that various systems (e.g. physical, biological, social) should be viewed as wholes, not merely as a collection of parts. The term "holism" was coined by Jan Smuts in his 1926 book ''Holism and Evolution''."holism, n." OED Onl ...

, thereby land relating to Bantu-speaking peoples of South Africa legislatively became reduced into being those reserves. In this context, the Natives Land Act, 1913, limited Black South Africans to 7% of the land in the country. In 1936, through the Native Trust and Land Act, 1936, Union of South Africa's government planned to raise this to 13.6% but subsequently would not.

The National Party (South Africa) government, the Apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

government became the profundity action from the pre-1948 Union of South Africa's government rule, it introduced a series of measures that reshaped the South African society such that Europeans would take themselves as the demographic majority while being a minority group. The creation of false homelands or Bantustans (based on dividing ''South African Bantu language speaking peoples'' by ethnicity) was a central element of this strategy, the Bantustans were eventually made nominally independent, in order to limit ''South African Bantu language speaking peoples'' citizenship to those Bantustans. The Bantustans were meant to reflect an analogy of the various ethnic "-stans" of Western and Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the former ...

such as the Kafiristan, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, etc. But in South Africa, the association with Apartheid discredited the term, and the Apartheid government shifted to the politically appealing but historically deceptive term "ethnic homelands". Meanwhile, the Anti-Apartheid Movement persisted in calling the areas Bantustans, to actively protest the Apartheid governments' political illegitimacy. The fallacy of ''The Empty Land Myth'' also completely omits the existence of the Khoisan

Khoisan , or (), according to the contemporary Khoekhoegowab orthography, is a catch-all term for those indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who do not speak one of the Bantu languages, combining the (formerly "Khoikhoi") and the or ( in ...

(a catch-all term) populations of southern Africa who roamed much of the south western region of South Africa for millennia before any arrival of Europeans in South Africa.

Particularly right-wing nationalists

Right-wing populism, also called national populism and right-wing nationalism, is a political ideology that combines right-wing politics and populist rhetoric and themes. Its rhetoric employs anti-elitist sentiments, opposition to the Establi ...

of European descent, maintain that the theory still holds true, despite there being even more historical and archaeological evidence contrary to the myth, for example the Lydenburg heads, the Bantu-speaking peoples' Kingdom of Mapungubwe (c.1075–c.1220) and Leo Africanus's account of Bantu-speaking peoples of the region. Archaelogical evidence suggests that ''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

'' inhabited the region for over 100,000 years, with sedentary agriculture occurring since at least 100 CE. In the early 16th century, explorer Leo Africanus described the ''Cafri'' ( Kafir's variant) as negroes, and one of five principal population groups in Africa. He identified their geographical heartland as being located in remote Southern Africa, an area which he designated as ''Cafraria''. European cartographers in their 16th and 17th centuries versions of southern African maps, likewise called the southern African region Cafreria. In the late 16th century, Richard Hakluyt, an English writer, in his words describes ''Cafars'' and Gawars, translate to infidels and illiterates (not to be confused with slaves called Cafari, the Malagasy people called Cafres and certain inhabitants of Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the Er ...

known as Cafars), as Bantu-speaking peoples of southern Africa in his work. Historically past names of South Africa in records largely relied upon how European explorers to Africa referred to the indigenous people, in the 16th century the whole coastal region was known in Portuguese cartography as Cafreria, and in French cartography as ''Coste Des Caffres'', which translates to the Coast of ''Caffres'' of the south Limpopo River in 1688, "Cafres or Caffres" being a word derived from an Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

word "Kafir" (meaning "non-believer"). It was also known as the Bantu-speaking peoples' Kingdom of Mutapa (1430–1760) at its peak. During the establishment and the time throughout the 18th century Cape Colony, South Africa was referred to as ''The Country of the Hottentots and Caffria'', ( ''Hottentot'' is a deprecated reference to the Khoisan people of Western Cape, South Africa, while Caffria stemming from Kafir/ Kaffir which is now an offensive racial slur to ''South African Bantu language speaking peoples''). Other than Portuguese cartographers calling present-day South Africa's coast Cafreria in the 16th century, another Cafraria dub directly related to the present-day South African region covered the landscape as presented by a Dutch cartographer Willem Blaeu's work, '' Theatrum Orbis Terrarum'' (1635). The later derivative Kaffraria (obsolete name) became a reference to only the present day Eastern Cape.

Based on prehistorical archaeological evidence of pastoralism and farming in southern Africa, settlements forming part of countless ancient settlements remains related to ''Bantu language speaking peoples'' of Africa, specifically those from sites located in the southernmost region inside the borders of what is now Mozambique

Mozambique (), officially the Republic of Mozambique ( pt, Moçambique or , ; ny, Mozambiki; sw, Msumbiji; ts, Muzambhiki), is a country located in southeastern Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Mala ...

take importance to this article for being the closest, oldest archaeological evidence by distance to the South African border thus far related to South African Bantu–speaking peoples and dated . Ancient settlements remains found thus far similarly based on pastoralism and farming within South Africa were dated .

When the early Portuguese sailors Vasco Da Gama and Bartholomew Dias reached the Cape of Good Hope in the late , a number of Khoe language speakers were found living there and the indigenous population around the Cape primarily consisted of Khoisan groups. Following the establishment of the Dutch Cape Colony, European settlers began arriving in Southern Africa in substantial numbers. Around the 1770s, Trekboer

The Trekboers ( af, Trekboere) were nomadic pastoralists descended from European settlers on the frontiers of the Dutch Cape Colony in Southern Africa. The Trekboers began migrating into the interior from the areas surrounding what is now Ca ...

s from the Cape encountered more Bantu language speakers towards the Great Fish River and frictions eventually arose between the two groups. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, there were two major areas of frictional contact between the white colonialists and the Bantu language speakers in Southern Africa. Firstly, as the Boers moved north inland from the Cape they encountered Xhosa, Basotho, and Tswana peoples. Secondly attempts at coastal settlement was made by the British in two regions now known as the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal (, also referred to as KZN and known as "the garden province") is a province of South Africa that was created in 1994 when the Zulu bantustan of KwaZulu ("Place of the Zulu" in Zulu) and Natal Province were merged. It is loca ...

.

Brief South African colonial-era history through Polities

Xhosa Wars

The longest running military action from the period of colonialism in Africa, which saw a series of nine wars during 1779 till 1879. Involving theXhosa Kingdom

Xhosa may refer to:

* Xhosa people, a nation, and ethnic group, who live in south-central and southeasterly region of South Africa

* Xhosa language

Xhosa (, ) also isiXhosa as an endonym, is a Nguni language and one of the official languages ...

and the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading post ...

, mainly in the present day South African region of Eastern Cape.

(1779–1803): After European invasion of the present day Western Cape, South Africa region, colonialist's frontiersmen in the 18th century started encroaching the land farther inland present-day South African region, encountering more of the indigenous population, conflict of land and cattle grew sparking the first war that set to drive Xhosa people out of Zuurveld by 1781. The second war involved a larger Xhosa territory between the Great Fish River and the Sundays River, the Gqunukhwebe clans of the Xhosa started to penetrate back into the Zuurveld and colonists under Barend Lindeque, allied themselves with Ndlambe, a regent of the Western Xhosas, to repel the Gqunukhwebe. The second war concluded when farms were abandoned due to panic in 1793. In 1799 the third war began with the Xhosa rebellion – discontented Khoekhoe revolted and joined with the Xhosa in the Zuurveld, and started retaking land through farms occupied by colonialist, reaching Oudtshoorn by July 1799. The colonial officials made peace with the Xhosa and Khoe in Zuurveld. In 1801, Graaff-Reinet rebellion started forcing more Khoekhoe desertions and farm abandonment. The commandos could not achieve any result, so in February 1803 a peace was arranged with the Xhosas and Khoekhoes.

(1811–1819): Zuurveld became a buffer zone between the Cape Colony and Xhosa territory, empty of the Boers, the British to the west and the Xhosa to the east. In 1811 the fourth war began when the Xhosa took back the rest of their territory of Zuurveld, conflicts with the settlers followed. Forces under Colonel John Graham drove the Xhosa back beyond the Fish River. The fifth war, the war of Nxele, started after the Battle of Amalinde. This happened after a civil war broke out within the Xhosa Nation when the British-allied chief Ngqika of the Right Hand House allegedly tried to overthrow the Government and become the king of the Xhosas but was defeated. Then Ngqika appealed to the British who seized 23,000 head of cattle from a Xhosa chief. The Xhosa prophet, Nxele (Makhanda) emerged, under the command of Mdushane

The Imidushane clan was founded by one of the greatest Xhosa warriors Prince Mdushane who was the eldest son of Chief Ndlambe, the son of Prince Rharhabe.

The Imidushane are therefore a subgroup within the Xhosa nation and can be found in the Eas ...

, Ndlambe's son, led 6,000 Xhosa force attack in 22 April 1819 to Grahamstown, which was held by 350 troops repulsed Nxele. Nxele was captured and imprisoned on Robben Island. The British pushed the Xhosa further east beyond the Fish River to the Keiskamma River. The resulting empty territory was designated as a buffer zone for loyal Africans' settlements. It came to be known as the "Ceded Territories".

(1834–1879): The Xhosa remained expelled from their territory dubbed "Ceded Territories", that was then settled by Europeans and other African peoples. They were also subjected to territorial expansions from other Africans that were themselves under pressure from the expanding Zulu Kingdom. Nevertheless, the frontier region was seeing increasing amounts of multi-racial issues because Africans and Europeans living and trading throughout the frontier region. The indecision by the Cape Government's policy towards the return of the Xhosa territories did not dissipate Xhosa frustration toward the inability to provide for themselves, hence the Xhosa resorted to frontier cattle-raiding. In response on 11 December 1834, a Cape government commando party killed a chief of high rank, incensing the Xhosa army of 10,000 led by Maqoma, that swept across the frontier into the Cape Colony. A string of defeats by Sir Benjamin d'Urban combining forces under Colonel Sir Harry Smith stopped the Xhosa, most Xhosa chiefs surrendered but the primary leadership Maqoma and Tyali retreated, a treaty was imposed and hostilities finally died down on 17 September 1836. Aftermath the sixth war, a chief believed to be actually the paramount chief or the King of the Gcaleka Xhosa by the Cape Colony, Chief Hintsa ka Khawuta, was shot and killed by George Southey, brother of Richard Southey. The era also saw the rise and fall of Stockenström's treaty system.

The seventh war became a war between the imperial British troops collaborating with the mixed-race "Burgher forces", which were mainly Khoi, Fengu, British settlers and Boer commandos, against the Ngcika assisted by the Ndlambe and Thembu. Tension had been simmering between colonialist farmers and Xhosa raiders, on both sides of the frontier since the dismantlement of Stockenstrom's treaty system. This began when Governor Maitland imposed a new system of treaties on the chiefs without consulting them, while a severe drought forced desperate Xhosa to engage in cattle raids across the frontier to survive. In addition, politician Robert Godlonton continued to use his newspaper the Graham's Town Journal to agitate for 1820 Settlers to annex and settle the land that had been returned to the Xhosa after the previous war. The war concluded after the announcement of the annexation of the country between the Keiskamma and the Kei rivers to the British crown by order of Lord Glenelg. It was not, however, incorporated with the Cape Colony, but made a crown dependency under the name of British Kaffraria Colony with King William's Town as its capital.

Large numbers of Xhosa were displaced across the Keiskamma by Governor Harry Smith, and these refugees supplemented the original inhabitants there, causing overpopulation and hardship. Those Xhosa who remained in the colony were moved to towns and encouraged to adopt European lifestyles. In June 1850 there followed an unusually cold winter, together with an extreme drought. It was at this time that Smith ordered the displacement of large numbers of Xhosa squatters from the Kat River region. The war became known as "Mlanjeni's War", the eighth war, after the prophet Mlanjeni who arose among the homeless Xhosa and preached mobilization, large numbers of Xhosa began leaving the colony's towns and mobilizing in the tribal areas. In February 1852, the British Government decided that Sir Harry Smith's inept rule had been responsible for much of the violence, and ordered him replaced by George Cathcart, who took charge in March. In February 1853 Xhosa chiefs surrendered, the 8th frontier war was the most bitter and brutal in the series of Xhosa wars. It lasted over two years and ended in subjugation of the Ciskei Xhosa.

The cattle-killing movement that began in 1856 to 1858, led Xhosa people to destroy their own means of subsistence in the belief that it would bring about salvation from colonialism through supernatural spirits. First declared by a prophetess Nongqawuse

Nongqawuse (; ''c.'' 1841 – 1898) was the Xhosa people, Xhosa prophet whose prophecies led to a millenarianism, millenarian movement that culminated in the history of the Cape Colony from 1806 to 1870#Xhosa cattle-killing movement and famine (1 ...

no one believed in the prophecy and it was considered absurdity, but more and more people started believing Nongqawuse. The cult grew and built up momentum, sweeping across the eastern Cape. The return of the ancestors was predicted to occur on 18 February 1857, when the day came, the Xhosa nation waited en masse for the momentous events to occur, only to be bitterly disappointed. Famine set in and disease was also spread from the cattle killings, this forced the remainder of the Xhosa nation to seek relief from colonialists.

In 1877 the ninth of the Cape frontier war happened, known as the "Fengu-Gcaleka War", and also the "Ngcayechibi's War" — the name stemming from a headman whose feast was where the initial fight occurred that traces from the conflicts of this war.

Creation of the Zulu Kingdom

Before the early 19th century the indigenous population composition in KwaZulu-Natal region was primarily by many different, largely Nguni-speaking clans and influenced by the two powers of the Mthethwa and the Ndwandwe. In 1816, Shaka acceded to the Zulu throne (at that stage the Zulu was merely one of the many clans). Within a relatively short period of time he had conquered his neighbouring clans and had forged the Zulu into the most important ally of the large Mthethwa clan, which was in competition with the Ndwandwe clan for domination of the northern part of modern-day KwaZulu-Natal. After the death of the Mthethwa king Dingiswayo around 1818, at the hands of Zwide, the king of the Ndwandwe, Shaka assumed leadership of the entire Mthethwa alliance. The alliance under his leadership survived Zwide's first assault at the Battle of Gqokli Hill. Within two years he had defeated Zwide at the Battle of Mhlatuze River and broken up the Ndwandwe alliance, some of whom in turn began a murderous campaign against other Nguni communities, resulting in a mass migration of communities fleeing those who are regarded now as Zulu people too. Historians have postulated this as the cause of the Mfecane, a period of mass migration and war in the Southern African interior in the 19th, however this hypothesis is no longer accepted by most historians, and the idea itself of Mfecane/''Difaqane'' has been thoroughly disputed by many scholars, notably by Julian Cobbing.

After the death of the Mthethwa king Dingiswayo around 1818, at the hands of Zwide, the king of the Ndwandwe, Shaka assumed leadership of the entire Mthethwa alliance. The alliance under his leadership survived Zwide's first assault at the Battle of Gqokli Hill. Within two years he had defeated Zwide at the Battle of Mhlatuze River and broken up the Ndwandwe alliance, some of whom in turn began a murderous campaign against other Nguni communities, resulting in a mass migration of communities fleeing those who are regarded now as Zulu people too. Historians have postulated this as the cause of the Mfecane, a period of mass migration and war in the Southern African interior in the 19th, however this hypothesis is no longer accepted by most historians, and the idea itself of Mfecane/''Difaqane'' has been thoroughly disputed by many scholars, notably by Julian Cobbing.

Pedi Kingdom

The Pedipolity

A polity is an identifiable political entity – a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of institutionalized social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize resources. A polity can be any other group of p ...

under King Thulare (c. 1780–1820) was made up of land that stretched from present-day Rustenburg to the lowveld in the west and as far south as the Vaal River

The Vaal River ( ; Khoemana: ) is the largest tributary of the Orange River in South Africa. The river has its source near Breyten in Mpumalanga province, east of Johannesburg and about north of Ermelo and only about from the Indian Ocea ...

. Pedi power was undermined during the Mfecane, by the Ndwandwe. A period of dislocation followed, after which the polity was re-stabilized under Thulare's son Sekwati.

Sekwati succeeded King Thulare as paramount chief of the Bapedi in the northern Transvaal (Limpopo

Limpopo is the northernmost province of South Africa. It is named after the Limpopo River, which forms the province's western and northern borders. The capital and largest city in the province is Polokwane, while the provincial legislature is ...

). He engaged in maintaining his domain from other indigenous polities, mostly in frequent conflict with Mzilikazi's army who then had established and residing in Mhlahlandlela (present day Centurion, Gauteng) after retreating King Shaka Zulu, Sigidi kaSenzagakhona's forces, before they moved on to found the Mthwakazi, Kingdom of Mthwakazi, the Northern Ndebele people#Hlabezulu Kingdom/ KoMthwakazi, Northern Ndebele Kingdom.

Sekwati was also engaged in struggles over land and labour with the invading colonialists. These disputes over land started in 1845 after the arrival of Boers and their declaring of Ohrigstad in King Sekwati's domain, in 1857 the town was incorporated into the South African Republic, Transvaal Republic and the Lydenburg, Republic of Lydenburg was formed, an agreement was reached that the Steelpoort River was the border between the Pedi and the Republic. The Pedi were well equipped for waging war though, as Sekwati and his heir, Sekhukhune I were able to procure firearms, mostly through migrant labour from the Kimberley, Northern Cape, Kimberley diamond fields and as far as Port Elizabeth. On 16 May 1876, Thomas François Burgers, president of the South African Republic (ZAR), not to be confused with the modern-day Republic of South Africa, caused the First of the Sekhukhune Wars when he declared war against the Bapedi Kingdom, the Burgers' army was defeated on 1 August 1876. The Burgers' government later hired the Lydenburg Volunteer Corps commanded by a German mercenary Conrad von Schlickmann, they were repelled and Conrad was killed in later battles.

On 16 February 1877, the two parties, mediated by Alexander Merensky, signed a peace treaty at Botshabelo. This led to the British annexation of the South African Republic (ZAR) on 12 April 1877 by Sir Theophilus Shepstone, a secretary for native affairs of Natal at that time. The Second of Sekhukhune Wars commenced in 1878 and 1879 with three British attacks that were successfully repelled but Sekhukhune was defeated in November 1879 by Sir Garnet Wolseley's army of twelve thousand, made up of the 2,000 British, Boers and 10,000 Swazis, Swazis joined the war in support of Mampuru II's claim to the Bopedi (Pedi Kingdom) throne. This brought about the Pretoria Convention of 3 August 1881, which stipulated Sekhukhune's release on reasons that his capital was already burned to the ground. Sekhukhune I was murdered by assassination on alleged orders from his half brother Mampuru II due to the existing dispute to the throne, as Mampuru II had been ousted by Sekhukhune before being reinstalled as King of Bopedi by the British after the British invasion of Bopedi. King Mampuru II was then arrested and executed by the treaty restored Boer South African Republic (ZAR) on charges of public violence, revolt and the murder of his half brother. The arrest was also well claimed by others to be because of Mampuru's opposition to the hut tax imposed on black people by the South African Republic (ZAR) in the area.

Mampuru II has been described as one of South Africa's first liberation icons. Potgieter Street in Pretoria and the prison where he was killed was renamed in his honour, in February 2018 a statue of Mampuru was proposed to be erected in Church Square, Pretoria where it will stand opposite one of Paul Kruger who was President of the British's South African Republic (ZAR) at the time of Mampuru's execution. The Pedi paramountcy's power was also cemented by the fact that chiefs of subordinate villages, or kgoro, take their principal wives from the ruling house. This system of cousin marriage resulted in the perpetuation of marriage links between the ruling house and the subordinate groups, and involved the payment of inflated bohadi or bride wealth, mostly in the form of cattle, to the Maroteng house.

Inception of apartheid

The Apartheid government retained and continued on from 1948 with even more officiation and policing on racial oppression of Bantu-speaking peoples of South Africa for 48 years. Decades before the inception of Apartheid there was a Rand Rebellion uprising in 1922 which eventually became an open rebellion against the state, it was against mining companies whose efforts at the time, due to economic situations, were nullifying irrational oppression of natives in the work place. The pogroms and slogans used in the uprising against ''blacks'' by whites articulated that irrationally oppressing ''Bantu-speaking peoples of South Africa'' was much more a social movement in European communities in the 20th century South Africa, before ever becoming government in 1948 which happened through a discriminatory vote by only white, minority people in South Africa, that formed a racist, well resourced and a police state of an illegitimate government for nearly 50 years. In the 1930s, this irrational oppression/discrimination was already well supported by propaganda, ''e.g.'' the Carnegie Commission of Investigation on the Poor White Question in South Africa, it served as the blueprint of Apartheid.Democratic dispensation

A non-racial system franchise known as Cape Qualified Franchise was adhered to from year 1853 in the Cape Colony and the early years of the Cape Province which was later gradually restricted, and eventually abolished, under various National Party (South Africa), National Party and United Party (South Africa), United Party governments. It qualified practice of a local system of multi-racial suffrage. The early Cape constitution which later became known as the Cape Liberal tradition. When the Cape's political system was severely weakened, the movement survived as an increasingly liberal, local opposition against the Apartheid government of the National Party. In the fight against Apartheid, African majority took the lead in the struggle, as effective allies the remaining Cape liberals against the growing National Party, engaged to a degree in collaboration and exchange of ideas with the growing African liberation movements, especially in the early years of the struggle. This is seen through the non-racial values that were successfully propagated by the political ancestors of the African National Congress, and that came to reside at the centre of Constitution of South Africa, South Africa's post-Apartheid Constitution. The year 1994 saw the 1994 South African general election, first democratic election in South Africa, the majority of the population, Black South Africans, participating in Elections in South Africa, political national elections for the first time in what ceremonially ended the Apartheid era and also being the first time a political party in South Africa getting legitimately elected as government. The day was ideally hailed as Freedom Day (South Africa), Freedom day and the beginning of progress to the conclusion of Black South Africans existential struggle that began with European colonization in the South African region.

As a consequence of Apartheid policies, black Africans are regarded as a race group in South Africa. These groups (blacks, White South Africans, whites, Coloureds and Indians) still tend to have a strong racial identities, and to classify themselves, and others, as members of these race groups and the classification continues to persist in government policy, to an extent, as a result of attempts at redress such as Black Economic Empowerment and Affirmative action#South Africa, Employment Equity.

The year 1994 saw the 1994 South African general election, first democratic election in South Africa, the majority of the population, Black South Africans, participating in Elections in South Africa, political national elections for the first time in what ceremonially ended the Apartheid era and also being the first time a political party in South Africa getting legitimately elected as government. The day was ideally hailed as Freedom Day (South Africa), Freedom day and the beginning of progress to the conclusion of Black South Africans existential struggle that began with European colonization in the South African region.

As a consequence of Apartheid policies, black Africans are regarded as a race group in South Africa. These groups (blacks, White South Africans, whites, Coloureds and Indians) still tend to have a strong racial identities, and to classify themselves, and others, as members of these race groups and the classification continues to persist in government policy, to an extent, as a result of attempts at redress such as Black Economic Empowerment and Affirmative action#South Africa, Employment Equity.

Ethnic partitioning

African – ethnic or racial reference in South Africa is a synonym to Ethnic groups in South Africa#Black South Africans, Black South Africans. It is also used to refer to ''expatriate Black people'' from other African countries who are in South Africa. South Africa's Bantu language speaking communities are ''roughly'' classified into four main groups: Nguni people, Nguni, Sotho–Tswana, Venda, Vhavenda and Shangana Tsonga, Shangana–Tsonga, with the Nguni and Basotho-Tswana being the largest groups, as follows: * Nguni people(''Alphabetical''): **Hlubi people **Southern Ndebele people **Swazi people, Swati people **Xhosa people ***Korana people **Zulu people * Tsonga people, Shangana–Tsonga people * Sotho–Tswana people: ** Southern sotho ***Basotho ** Northern Sotho people, Northern Sotho ***BaPedi people **Tswana people, Batswana * Venda people: **Venda people, Vhavenda **Lemba people, Vhalemba (speaking Venda language, Venda)Culture

Black people in South Africa were group-related and their conception of borders based on sufficient land and natural features such as rivers or mountains, which were not by any means fixed. Common among the two powerful divisions, the Nguni and the Sotho–Tswana, are patrilineal societies, in which the leaders formed the socio-political units. Similarly, food acquisition was by pastoralism, agriculture, and hunting. The most important differences are the strongly deviating languages, although both are Southern Bantu languages, and the different settlement types and relationships. In the Nguni settlements villages were usually widely scattered, whereas the Sotho–Tswana often settled in towns.Language and communication

The majority of Bantu languages spoken in South Africa are classified as belonging to one of two groups. The Nguni languages (such as Xhosa language, Xhosa, Zulu language, Zulu, Southern Ndebele people, Ndebele, and Swazi language, Swazi), whose speakers historically occupied mainly the eastern coastal plains, and the Sotho–Tswana languages (such as the Sotho language, Southern Sotho, Tswana language, Tswana, Northern Sotho language, Northern Sotho) and whose speakers historically lived on the interior plateau. The two language groups differ in certain key aspects (especially in the sound systems), with the rest of South African Bantu languages (Venda language, Venda and Tsonga language, Tsonga) showing even more unique aspects. Significant number of Black South Africans are native multilingualism, multilingual, speaking two or more languages as their first language, mainly from languages of South Africa.Ditema syllabary

A constructed script of featural writing system and syllabary, whose developments in 2010 was inspired by ancient ideographic traditions of the Southern African region, and its parent systems being ''Amabheqe'' ideographs and Litema. It was developed for Southern Bantu languages, ''siNtu''. The origins of ''Litema'' ornament (art), ornamental and mural art of Southern Africa stretches centuries back in time, while excavations at Sotho-Tswana archaeological sites have revealed hut floors that have survived the elements for 1500 years, the earliest intact evidence of this art stretches back from the c. 1400s.

A constructed script of featural writing system and syllabary, whose developments in 2010 was inspired by ancient ideographic traditions of the Southern African region, and its parent systems being ''Amabheqe'' ideographs and Litema. It was developed for Southern Bantu languages, ''siNtu''. The origins of ''Litema'' ornament (art), ornamental and mural art of Southern Africa stretches centuries back in time, while excavations at Sotho-Tswana archaeological sites have revealed hut floors that have survived the elements for 1500 years, the earliest intact evidence of this art stretches back from the c. 1400s.

Southern Ndebele paintings

Southern Ndebele prior and during the 18th century primarily used their expressive symbols for communication, it is believed that these paintings are a synthesis of historical Nguni design traditions and Northern Sotho ''ditema'' or ''litema'' tradition(s). They also began to stand for their continuity and cultural resistance to their circumstances during the colonization in the 19th century. These wall paintings done by the women was their secret code to their people, disguised to anyone but the Southern Ndebele. The vibrant symbols and expressions portray communications of personal prayers, self-identification, values, emotions, and marriage, sometimes the male initiation but the ritual was not expressed. Religions have never been a part of the Southern Ndebele's house paintings. The women of the Southern Ndebele are often the tradition carriers and the main developer of the wall art of their home. The tradition and style of house painting is passed down in the families from generation to generation by the mothers. A well-painted home shows the female of the household is a good wife and mother. She is responsible for the painting of the outside gates, front walls, side walls, and usually the interior of her home. One thing that has changed since the beginning of the paintings and the present-day wall art is their styles. In the late 1960s, the new style was evident, what was once a finger-painted creation was now created using bundled twigs with feathers as brushes. The walls are still originally whitewashed, but the outlines and colours have significantly changed.

The patterns and symbols can be seen today with a rich black outline and a vivid colour inside. There are five main colours represented: red and dark red, yellow to gold, a sky blue, green, and sometimes pink, white is always used as the background because it makes the bright patterns stand out more. The geometric patterns and shape are first drawn with the black outline and later filled in with colour. The patterns are grouped together throughout the walls in terms of their basic design structure. Creating the right tools to allow accuracy and freedom becomes a difficult task. The tools can't restrict the painter from creating her art. They have to have tools for the large geometric shapes of flat colour and small brushes for the very small areas, outlines, and sacks. The advancement of tools has allowed faster and more complex designs throughout the Southern Ndebele's homes. Every generation passes it down and little changes become apparent.

Southern Ndebele prior and during the 18th century primarily used their expressive symbols for communication, it is believed that these paintings are a synthesis of historical Nguni design traditions and Northern Sotho ''ditema'' or ''litema'' tradition(s). They also began to stand for their continuity and cultural resistance to their circumstances during the colonization in the 19th century. These wall paintings done by the women was their secret code to their people, disguised to anyone but the Southern Ndebele. The vibrant symbols and expressions portray communications of personal prayers, self-identification, values, emotions, and marriage, sometimes the male initiation but the ritual was not expressed. Religions have never been a part of the Southern Ndebele's house paintings. The women of the Southern Ndebele are often the tradition carriers and the main developer of the wall art of their home. The tradition and style of house painting is passed down in the families from generation to generation by the mothers. A well-painted home shows the female of the household is a good wife and mother. She is responsible for the painting of the outside gates, front walls, side walls, and usually the interior of her home. One thing that has changed since the beginning of the paintings and the present-day wall art is their styles. In the late 1960s, the new style was evident, what was once a finger-painted creation was now created using bundled twigs with feathers as brushes. The walls are still originally whitewashed, but the outlines and colours have significantly changed.

The patterns and symbols can be seen today with a rich black outline and a vivid colour inside. There are five main colours represented: red and dark red, yellow to gold, a sky blue, green, and sometimes pink, white is always used as the background because it makes the bright patterns stand out more. The geometric patterns and shape are first drawn with the black outline and later filled in with colour. The patterns are grouped together throughout the walls in terms of their basic design structure. Creating the right tools to allow accuracy and freedom becomes a difficult task. The tools can't restrict the painter from creating her art. They have to have tools for the large geometric shapes of flat colour and small brushes for the very small areas, outlines, and sacks. The advancement of tools has allowed faster and more complex designs throughout the Southern Ndebele's homes. Every generation passes it down and little changes become apparent.

Traditional sports and martial arts

The most popular sporting code in South Africa and among Black South Africans is Association football with the most notable event having been hosted being the 2010 FIFA World Cup, but before such advent there are historical sports that were popular to the indigenous.

The most popular sporting code in South Africa and among Black South Africans is Association football with the most notable event having been hosted being the 2010 FIFA World Cup, but before such advent there are historical sports that were popular to the indigenous.

Nguni stick-fighting

It is a martial art historically practiced by teenage Nguni herdboys in South Africa. Each combatant is armed with two long, hard sticks, one of which is used for defense and the other for offense with little or no armor used. Although Xhosa styles of fighting may use only two sticks, variations of Nguni stick-fighting throughout Southern Africa incorporate shields as part of the stick-fighting weaponry. Zulu stick-fighting uses an ''isikhwili'', an attacking stick, and ''ubhoko'', a defending stick or an ''ihawu'', a defending shield. The objective is for two opposing warriors to fight each other to establish which of them is the strongest or the "Bull" (Inkunzi). An "induna" or War Captain becomes a referee for each group of warriors, keeps his crew in check and keeps order between fighters. Warriors of similar affiliation did this when engaging in combat with one another. In modern times this usually occurs as a friendly symbolic practice part of the wedding ceremony, where warriors (participants) from the bridegroom's household welcome warriors from the bride's household. Other groups of participants may also be welcomed to join in.Musangwe

A traditional, bare-knuckle, combat sport of Venda people. It resembles bare-knuckle boxing.Chiefdom

It is well documented in the Apartheid legislation, that the white minority, government regime – recreated and used the "traditional" Chiefdom-ships system to be the National Party (South Africa), National Party's power reach, and even increased the Chiefdom-ships' powers over the ''Bantu-speaking peoples of South Africa'' for the Apartheid government's interests. This was after colonial regimes and subsequent South African governments before formalApartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

, had initiated the taking of most of South African land from the indigenous peoples. Most of South African land began being made an exclusive possession of only white minority Europeans in South Africa legislatively by Natives Land Act, 1913, 1913.

Until very recently, South African Bantu-speaking communities were often divided into different clans, not around national federations, but independent groups from some hundreds to thousands of individuals. The smallest unit of the political organizational structure was the household, or kraal, consisting of a man, woman or women, and their children, as well as other relatives living in the same household. The man was the head of the household and often had many wives, and was the family's primary representative. The household and close relations generally played an important role. Households which lived in the same valley or on the same hill in a village were also an organizational unit, managed by a sub-chief.

Chiefdom-ship was largely hereditary, although chiefs were often replaced when not effective. In most clans the eldest son inherited the office of his father. In some clans the office was left to the oldest brother of the deceased chief, and after his death again the next oldest brother. This repeated until the last brother died. Next was the eldest son of the original chieftain; then the oldest one of the brothers as the leader.

The chief was surrounded with a number of trusted friends or advisors, usually relatives like uncles and brothers, rather than influential headmen or personal friends. The degree of the democracy depended on the strength of the chieftain. The more powerful and more influential a chieftain was, the less the influence of his people. Although the leader had much power, he was not above the law. He could be criticized both by advisors as well as by his people, and compensation could be demanded. The people were divided into different clans or tribes which had their own functions, laws, and language.

Time-reliant traditions

Xhosa calendar

Xhosa people historically and traditionally based their agricultural time on reliable star systems. When these traditions are aligned with the Gregorian calendar system the Xhosa year begins in June and ends in May when the Canopus star (in xh, UCanzibe) becomes visible in the Southern hemisphere, this signaled their time for harvesting.Sotho calendar

Sesotho months (in st, Likhoeli) indicate special natural and agricultural events of Southern Africa. Traditionally and historically, being cattle breeders who lived in the semi-arid regions of Southern Africa, a deep understanding of agriculture and the natural world was essential for their survival. Sesotho speaking people generally recognise only two seasons called ''Dihla''. However, names do exist aligned to all four of the traditional Western seasons. The Sotho year begins approximately in August or September, a time when their crops were planted.Traditional holidays

First Fruits

A ceremony of giving the first fruits in a harvest to God, or the gods who are believed to be responsible for the abundance of food in Southern Africa. Traditionally it marked a time of prosperity, in the good harvests experienced after the seasonal agricultural period. It also brought people together, unifying them at a time of merry making and quashing fears of famine. In South Africa the tradition is practiced by Zulu people of KwaZulu-Natal as ''Umkhosi Wokweshwama''.Umkhosi womHlanga

''Umhlanga'' is an annual event that originates from Eswatini in 1940s from the rule of King Sobhuza II, it is an adaptation of a much older ceremony of Umchwasho. In South Africa it was introduced by the Zulu King Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu in 1991 to be later known as ''Umkhosi womHlanga'', as a means to encourage young Zulu girls to delay sexual activity until marriage. All girls are required to undergo a virginity test before they are allowed to participate in a royal dance, they wear a traditional attire, including beadwork, and izigege, izinculuba and imintsha, with anklets, bracelets, necklaces, and colourful sashes. Each sash has appendages of a different colour, which denote whether or not the girl is betrothed. These young women then participate in a traditional dance bare-breasted, while each maiden carries a long reed – the girls take care to choose only the longest and strongest reeds – and then carry them towering above their heads in a slow procession up the hill to the royal Enyokeni Palace. The procession is led by the chief Zulu princess.Historical food acquisition

Food acquisition was primarily limited to types of subsistence agriculture (Slash and burn agriculture, slash and burn and Intensive subsistence farming), pastoral farming and engaging in hunting. Generally women were responsible for Crop agriculture and men went to Herding, herd and hunt except for the Tsonga (and partially the Mpondo). Fishing was relatively of little importance. All Bantu-speaking communities commonly had clear separation between women's and men's tasks. Essentially they consumed meat (primarily from Nguni cattle, Nguni sheep (Zulu sheep, Pedi sheep, Swazi sheep), pigs/boars and wild game hunts), vegetables, fruits, cattle and sheep milk, water, and grain beer on occasion. They began to eat the staple product of maize mid-18th century (introduced from Americas, the Americas by Portuguese in the late 17th century via the East African coast), it became favoured for its productiveness which was more than the grains of South African native grasses. There were a number of taboos regarding the consumption of meat. The well known, no meat of dogs, apes, crocodiles or snakes could be eaten. Likewise taboo was the meat of some birds, like owls, crows and vultures, as well as the flesh of certain totem animals. The Gonimbrasia belina, mopane worms are traditionally popular amongst the Tswana, Venda, Southern Ndebele, Northern Sotho and Tsonga people, though they have been successfully commercialized.

South African Bantu language speaking peoples' modern diet is largely still similar to that of their ancestors, but significant difference being in the systems of production and consumption of their food. They do take interest to innovations in foods that come their way while still practicing their very own unique food cuisine popular amongst themselves and those curious alike.

Essentially they consumed meat (primarily from Nguni cattle, Nguni sheep (Zulu sheep, Pedi sheep, Swazi sheep), pigs/boars and wild game hunts), vegetables, fruits, cattle and sheep milk, water, and grain beer on occasion. They began to eat the staple product of maize mid-18th century (introduced from Americas, the Americas by Portuguese in the late 17th century via the East African coast), it became favoured for its productiveness which was more than the grains of South African native grasses. There were a number of taboos regarding the consumption of meat. The well known, no meat of dogs, apes, crocodiles or snakes could be eaten. Likewise taboo was the meat of some birds, like owls, crows and vultures, as well as the flesh of certain totem animals. The Gonimbrasia belina, mopane worms are traditionally popular amongst the Tswana, Venda, Southern Ndebele, Northern Sotho and Tsonga people, though they have been successfully commercialized.

South African Bantu language speaking peoples' modern diet is largely still similar to that of their ancestors, but significant difference being in the systems of production and consumption of their food. They do take interest to innovations in foods that come their way while still practicing their very own unique food cuisine popular amongst themselves and those curious alike.

Pre-colonial and traditional house types

Historically, communities lived in two different types of houses before this tradition was dominated by one, the Rondavel. The Nguni people usually used the beehive house, a circular structure made of long poles covered with grass. The huts of the Sotho–Tswana people, Venda people and Shangana Tsonga, Shangana–Tsonga people, used the cone and cylinder house type. A cylindrical wall is formed out of vertical posts, which is sealed with mud and cow dung. The roof built from poles tied-together, covered with grass. The floor of both types is compressed earth. The Rondavel itself developed from the general, grass domed African-style hut nearly 3 000 years ago, its first variety, the ''veranda Rondavel'', emerged about 1 000 years ago in southern Africa. Colonial housing styles inspired the rectangular shaping of the Rondavel from the 1870s, this is regarded as the beginning of the Rondavel's westernization that sees this African indigenous invention even today being popularly known as the ''Rondavel'', (a derivative of af, Rondawel), instead of its indigenous name(s). Constraints caused by urbanisation produced a highveld type of style housing, shack-like, structures coalesced with Corrugated galvanised iron, corrugated metal sheeting (introduced during the British colonization), this marked a significant visible change in the southern African region, it attested to the contemporary pressures of ''South African Bantu-speaking peoples's'' realities, especially that of resources.Ideologies

Umvelinqangi

Umvelinqangi according to mainly Xhosa and Zulu people's culture is the ''Most High'' or ''Divine Consciousness'', is the source of all that has been, that is and all that ever will be. It's the inner light of creation. ''Ukukhothama'' (similar to meditation) prior to Colonization/Westernization was a widespread practice in South Africa noticeably by those considered Zulu people now, it was seen as a way of attaining ''oneness'' (in ), with the divine conscious.King Shaka's philosophy

King Shaka is well known for the many military, social, cultural and political reforms he used to create his highly organized and centralized Zulu Kingdom, Zulu state. The most important of these were the transformation of the Zulu army, army, thanks to innovative tactics and weapons he conceived, and a showdown with the spiritual leadership, limiting the power of traditional healers, and effectively ensuring the subservience of the Zulu church to the state. King Shaka integrated defeated Zulu language, Zulu-speaking tribes into the newly formed Zulu people, Zulu ethnic group, on a basis of full equality, with promotions in the army and civil service being a matter of merit rather than circumstance of birth.Guthrie M., ''Comparative Bantu. Farnboroiugh Vols. 1–4.'', Gregg International Publishers Ltd. 1967

King Shaka is well known for the many military, social, cultural and political reforms he used to create his highly organized and centralized Zulu Kingdom, Zulu state. The most important of these were the transformation of the Zulu army, army, thanks to innovative tactics and weapons he conceived, and a showdown with the spiritual leadership, limiting the power of traditional healers, and effectively ensuring the subservience of the Zulu church to the state. King Shaka integrated defeated Zulu language, Zulu-speaking tribes into the newly formed Zulu people, Zulu ethnic group, on a basis of full equality, with promotions in the army and civil service being a matter of merit rather than circumstance of birth.Guthrie M., ''Comparative Bantu. Farnboroiugh Vols. 1–4.'', Gregg International Publishers Ltd. 1967

Black Consciousness Movement

An Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-Apartheid movement that emerged in South Africa in the mid-1960s. BCM attacked what they saw as traditional white values, especially the "condescending" values of White South Africans, white people of Liberalism in South Africa, liberal opinion and emphasised the rejection of white monopoly on truth as a central tenet of their movement. The BCM's policy of perpetually challenging the dialectic of Apartheid South Africa as a means of transforming Black thought into rejecting prevailing opinion or mythology to attain a larger comprehension brought it into direct conflict with the full force of the security apparatus of the Apartheid regime.Ubuntu philosophy

A concept that began to be popularised in the 1950s and became propagated by political thinkers specifically in Southern Africa during the 1960s. Ubuntu asserts that society, not a transcendent being, gives human beings their humanity. An "extroverted communities" aspect is the most visible part of this ideology. There is sincere warmth with which people treat both strangers and members of the community. This overt display of warmth is not merely aesthetic but enables formation of spontaneous communities. The resultant collaborative work within these spontaneous communities transcends the aesthetic and gives functional significance to the value of warmth. It is also implied that Ubuntu is in the ideal of that everyone has different skills and strengths; people are not isolated, and through mutual support they can help each other to complete themselves.South African Bantu-speaking people

Notation of notable people from Black South African hosts renowned, contributors, scholars and professionals from a range of diverse and broad fields, also those who are laureates of national and international recognition and certain individuals from South African monarchs.See also

* Demographics of South Africa * Khoekhoe, Khoi—San people, San peoples * Coloureds * Asian South African * White South AfricanDiaspora

*Northern Ndebele people *Ngoni people *Kololo people *Makololo Chiefs (Malawi) **(Their modern descendants have little connection with the Kololo people apart from their name.) *Relating South African diasporaReferences

Further reading

* Leroy Vail, Vail, Leroy, editor. ''The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa''. London Berkeley: Currey University of California Press, 1989. * B. Khoza (PHD), Makhosi, author. ''Uzalo Isizulu Grammar Textbook''. Cambridge University Press, 2017. {{Ethnic groups in South Africa Bantu-speaking peoples of South Africa Bantu peoples Indigenous peoples of Southern Africa South African people of African descent Ethnic groups in South Africa Society of South Africa Demographics of South Africa,