Banias on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Banias or Banyas ( ar, بانياس الحولة; he, בניאס, label=

In 2022, the Israeli Antiquities Authority discovered a trove of 44 pure gold coins from the early 7th Century CE. While some of the coins were minted by the Byzantine-Roman Emperor

In 2022, the Israeli Antiquities Authority discovered a trove of 44 pure gold coins from the early 7th Century CE. While some of the coins were minted by the Byzantine-Roman Emperor

26

38

/ref> With the decline of Abbasid power in the tenth century, Paneas found itself a provincial backwater in a slowly collapsing empire, as district governors began to exert greater autonomy and used their increasing power to make their positions hereditary. The control of Syria and Paneas passed to the

The Crusaders' arrival in 1099 quickly split the mosaic of semi-independent cities of the Seljuk sultanate of Damascus.

The Crusaders have held the town twice, between 1129–1132 and 1140–1164.Pringle, 2009, p.

The Crusaders' arrival in 1099 quickly split the mosaic of semi-independent cities of the Seljuk sultanate of Damascus.

The Crusaders have held the town twice, between 1129–1132 and 1140–1164.Pringle, 2009, p.

30

/ref> It was called by the Franks Belinas or Caesarea Philippi.Pringle, 2011, pp. 136, 184, 254. From 1126–1129, the town was held by

p. 75-77

In 1200, Sultan Probably at the same time, the city was passed to Al-Mu'azzam's brother, al-'Aziz 'Uthman. For a while it was ruled as the hereditary principality of the dynast and his sons. The fourth prince, al-Sa'id Hasan, surrendered it to

Probably at the same time, the city was passed to Al-Mu'azzam's brother, al-'Aziz 'Uthman. For a while it was ruled as the hereditary principality of the dynast and his sons. The fourth prince, al-Sa'id Hasan, surrendered it to

In 1977, the Banias was declared a nature reserve by the

In 1977, the Banias was declared a nature reserve by the

181183

/ref>Saulcy, 1854, pp

537

538 Eusebius of Caesarea accurately places Dan/Laish in the vicinity of Paneas at the fourth mile on the route to Tyre. Eusebius's identification was confirmed by E Robinson in 1838 and subsequently by archaeological excavations at both Tel Dan and Caesarea Philippi.

308

ff.) * * * *Hindley, Geoffrey. (2004) The Crusades: Islam and Christianity in the Struggle for World Supremacy Carroll & Graf Publishers, * * * *

1534380418

* * * *Ma‘oz, Z.-U. ed., ''Excavations in the Sanctuary of Pan at Caesarea Philippi-Baniyas, 1988-1993'' (Jerusalem, forthcoming). *Ma‘oz, Z.-U., ''Baniyas: The Roman Temples'' (Qazrin: Archaostyle, 2009). *Ma‘oz, Z.-U., ''Baniyas in the Greco-Roman Period: A History Based on the Excavations'' (Qazrin: Archaostyle, 2007). *Ma‘oz, Z.-U., V. Tzaferis, and M. Hartal, “Banias,” in ''The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land'' 1 and 5 (Jerusalem 1993 and 2008), 136-143, 1587-1594. * * * * *

Israel Nature and Parks Authority

Hermon Stream (Banias) Nature Reserve

The Nahal Hermon Reserve (Banias).

''Jewish Encyclopedia''

Cæsarea Philippi

entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

Banias Travel Guide

Photo of fortifications, from 1862

* * {{National parks in the Israeli-occupied territories Hellenistic sites in Syria Archaeological sites in Quneitra Governorate Classical sites on the Golan Heights Coele-Syria Crusade places Former populated places on the Golan Heights Holy cities Jordan River basin Medieval sites on the Golan Heights New Testament cities Pan cult sites Populated places established in the 2nd century BC Ptolemaic Kingdom Roman sites in Syria 3rd-century BC establishments 1967 disestablishments Mount Hermon

Modern Hebrew

Modern Hebrew ( he, עברית חדשה, ''ʿivrít ḥadašá ', , '' lit.'' "Modern Hebrew" or "New Hebrew"), also known as Israeli Hebrew or Israeli, and generally referred to by speakers simply as Hebrew ( ), is the standard form of the He ...

; Judeo-Aramaic

Judaeo-Aramaic languages represent a group of Hebrew-influenced Aramaic and Neo-Aramaic languages.

Early use

Aramaic, like Hebrew, is a Northwest Semitic language, and the two share many features. From the 7th century BCE, Aramaic became th ...

, Medieval Hebrew

Medieval Hebrew was a literary and liturgical language that existed between the 4th and 19th century. It was not commonly used as a spoken language, but mainly in written form by rabbis, scholars and poets. Medieval Hebrew had many features t ...

: פמייס, etc.; grc, Πανεάς) is a site in the Golan Heights

The Golan Heights ( ar, هَضْبَةُ الْجَوْلَانِ, Haḍbatu l-Jawlān or ; he, רמת הגולן, ), or simply the Golan, is a region in the Levant spanning about . The region defined as the Golan Heights differs between d ...

near a natural spring, once associated with the Greek god Pan. It had been inhabited for 2,000 years, until it was abandoned and destroyed following the Six Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

.How modern disputes have reshaped the ancient city of BaniasAeon

The word aeon , also spelled eon (in American and Australian English), originally meant "life", "vital force" or "being", "generation" or "a period of time", though it tended to be translated as "age" in the sense of "ages", "forever", "timel ...

: "In June 1967, the penultimate day of the Six Day War saw Israeli tanks storm into Banias in breach of a UN ceasefire accepted by Syria hours earlier. The Israeli general Moshe Dayan had decided to act unilaterally and take the Golan. The Arab villagers fled to the Syrian Druze village of Majdal Shams higher up the mountain, where they waited. After seven weeks, abandoning hope of return, they dispersed east into Syria. Israeli bulldozers razed their homes to the ground a few months later, bringing to an end two millennia of life in Banias. Only the mosque, the church and the shrines were spared, along with the Ottoman house of the shaykh perched high atop its Roman foundations." It is located at the foot of Mount Hermon, north of the Golan Heights

The Golan Heights ( ar, هَضْبَةُ الْجَوْلَانِ, Haḍbatu l-Jawlān or ; he, רמת הגולן, ), or simply the Golan, is a region in the Levant spanning about . The region defined as the Golan Heights differs between d ...

, in the part of Syria occupied and annexed by Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

. The spring is the source of the Banias River, one of the main tributaries of the Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

. Archaeologists uncovered a shrine dedicated to Pan and related deities, and the remains of an ancient city founded sometime after the conquest by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

and inhabited until 1967

Events

January

* January 1 – Canada begins a year-long celebration of the 100th anniversary of Canadian Confederation, Confederation, featuring the Expo 67 World's Fair.

* January 5

** Spain and Romania sign an agreement in Paris, establ ...

. The ancient city was mentioned in the Gospels of Matthew and Mark

Mark may refer to:

Currency

* Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina

* East German mark, the currency of the German Democratic Republic

* Estonian mark, the currency of Estonia between 1918 and 1927

* F ...

, under the name of Caesarea Philippi, as the place where Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

confirmed Peter's assumption that Jesus was the Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

; the site is today a place of pilgrimage for Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

.

The first mention of the ancient city during the Hellenistic period was in the context of the Battle of Panium, fought around 200–198 BCE, when the name of the region was given as the Panion. Later, Pliny called the city Paneas ( el, Πανειάς). Both names were derived from that of Pan, the god of the wild and companion of the nymph

A nymph ( grc, νύμφη, nýmphē, el, script=Latn, nímfi, label=Modern Greek; , ) in ancient Greek folklore is a minor female nature deity. Different from Greek goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as personifications of nature, are ty ...

s.

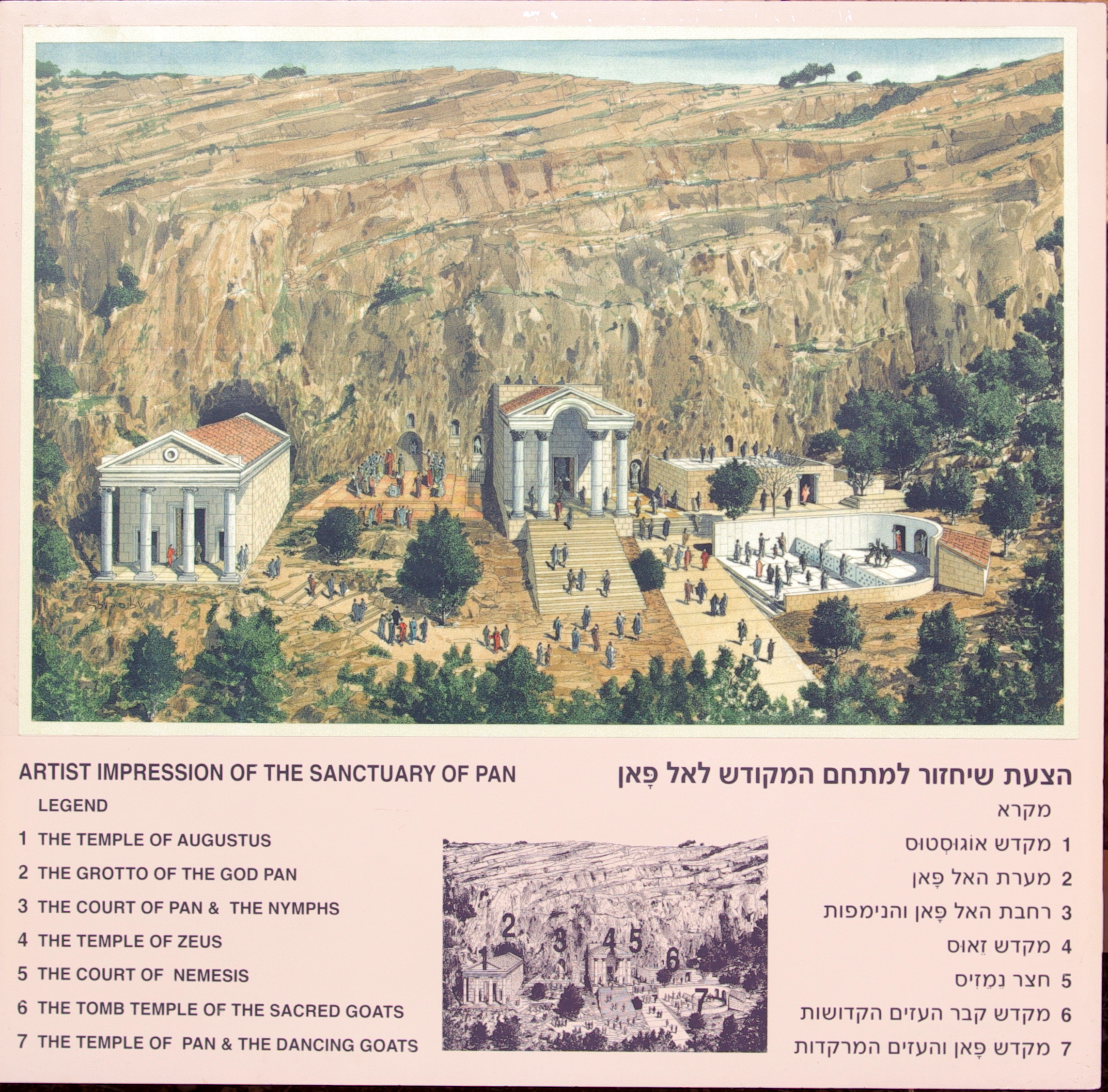

The spring at Banias initially originated in a large cave carved out of a sheer cliff face which was gradually lined with a series of shrines. The ''temenos

A ''temenos'' (Greek: ; plural: , ''temenē''). is a piece of land cut off and assigned as an official domain, especially to kings and chiefs, or a piece of land marked off from common uses and dedicated to a god, such as a sanctuary, holy gro ...

'' (sacred precinct) included in its final phase a temple placed at the mouth of the cave, courtyards for rituals, and niches for statues. It was constructed on an elevated, 80m long natural terrace along the cliff which towered over the north of the city. A four-line inscription at the base of one of the niches relates to Pan and Echo

In audio signal processing and acoustics, an echo is a reflection of sound that arrives at the listener with a delay after the direct sound. The delay is directly proportional to the distance of the reflecting surface from the source and the li ...

, the mountain nymph, and was dated to 87 BCE.

The once very large spring gushed from the limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms wh ...

cave, but an earthquake moved it to the foot of the natural terrace where it now seeps quietly from the bedrock, with a greatly reduced flow. From here the stream, called Nahal Hermon in Hebrew, flows towards what once were the malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or deat ...

-infested Hula marshes.

History

Semitic deity of the spring

The pre-Hellenistic deity associated with the spring of Banias was variously called Ba'al-gad or Ba'al-hermon.Hellenism; association with Pan

Banias was certainly an ancient place of great sanctity, and when Hellenised religious influences began to overlay the region, the cult of its localnumen

Numen (plural numina) is a Latin term for " divinity", "divine presence", or "divine will." The Latin authors defined it as follows:For a more extensive account, refer to Cicero writes of a "divine mind" (''divina mens''), a god "whose numen eve ...

gave place to the worship of Pan, to whom the cave was therefore dedicated.

Paneas ( grc, Πανεάς) was first settled in the Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium i ...

period following Alexander the Great's conquest of the east. The Ptolemaic kings built a cult centre there in the 3rd century BCE.

In the Hellenistic Period the spring was named Panias, for the Arcadian goat-footed god

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

Pan. Pan was revered by the ancient Greeks as the god of isolated rural areas, music, goat herds, hunting, herding, of sexual and spiritual possession, and of victory in battle, since he was said to instill panic among the enemy. The Latin equivalent for Paneas is Fanium.

The spring lies close to the 'way of the sea' mentioned by the Book of Isaiah, along which many armies of Antiquity marched.

In extant sections of the Greek historian Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

's history of 'The Rise of the Roman Empire', a Battle of Panium is mentioned. This battle was fought in ca. 200–198 BCE between the armies of Ptolemaic Egypt and the Seleucid

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the M ...

s of Coele-Syria

Coele-Syria (, also spelt Coele Syria, Coelesyria, Celesyria) alternatively Coelo-Syria or Coelosyria (; grc-gre, Κοίλη Συρία, ''Koílē Syría'', 'Hollow Syria'; lat, Cœlē Syria or ), was a region of Syria (region), Syria in cl ...

, led by Antiochus III

Antiochus III the Great (; grc-gre, Ἀντίoχoς Μέγας ; c. 2413 July 187 BC) was a Greek Hellenistic king and the 6th ruler of the Seleucid Empire, reigning from 222 to 187 BC. He ruled over the region of Syria and large parts of the r ...

. Antiochus's victory cemented Seleucid control over Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

, Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Gali ...

, Samaria

Samaria (; he, שֹׁמְרוֹן, translit=Šōmrōn, ar, السامرة, translit=as-Sāmirah) is the historic and biblical name used for the central region of Palestine, bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The first ...

, and Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous Latin, and the modern-day name of the mountainous south ...

until the Maccabean revolt

The Maccabean Revolt ( he, מרד החשמונאים) was a Jewish rebellion led by the Maccabees against the Seleucid Empire and against Hellenistic influence on Jewish life. The main phase of the revolt lasted from 167–160 BCE and ended ...

. It was these Seleucids who built a pagan temple dedicated to Pan at Paneas.

In 2020, an altar was found with a Greek inscription, in the walls of a church of the 7th century A.D. The inscription writes that the altar was dedicated by Atheneon, son of Sosipatros, from the city of Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

to the god Pan Heliopolitanos.

Phocas

Phocas ( la, Focas; grc-gre, Φωκάς, Phōkás; 5475 October 610) was Eastern Roman emperor from 602 to 610. Initially, a middle-ranking officer in the Eastern Roman army, Phocas rose to prominence as a spokesman for dissatisfied soldie ...

(602-610 CE), most date to the reign of his successor, Emperor Heraclius

Heraclius ( grc-gre, Ἡράκλειος, Hērákleios; c. 575 – 11 February 641), was Eastern Roman emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Africa, led a revolt ...

(610-641). The latest of the coins date to the period of the Arab conquest of the Levant.

Roman and Christian Byzantine periods

Upon Zenodorus's death in 20 BC, the Panion (), including Paneas, was annexed to theHerodian Kingdom of Judea

The Herodian Kingdom of Judea was a client state of the Roman Republic from 37 BCE, when Herod the Great, who had been appointed "King of the Jews" by the Roman Senate in 40/39 BCE, took actual control over the country. When Herod died in 4 BC ...

, a client

Client(s) or The Client may refer to:

* Client (business)

* Client (computing), hardware or software that accesses a remote service on another computer

* Customer or client, a recipient of goods or services in return for monetary or other valuabl ...

of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kingd ...

and Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

. Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

mentions that Herod the Great

Herod I (; ; grc-gre, ; c. 72 – 4 or 1 BCE), also known as Herod the Great, was a History of the Jews in the Roman Empire, Roman Jewish client state, client king of Judea, referred to as the Herodian Kingdom of Judea, Herodian kingdom. He ...

erected a temple of 'white marble' nearby in honor of his patron; it was found in the nearby site of Omrit

Omrit (), or Khirbat ‘Umayrī, is the site of an ancient Roman temple in the Israel–Syria demilitarised zone.

It is believed that Omrit was built by Herod the Great in honor of Augustus around 20 BCE. The site was destroyed in the Galilee ...

.

In 3 BCE, Herod's son, Philip II (also known as Philip the Tetrarch) founded a city which became his administrative capital, known from Josephus and the Gospels of Matthew and Mark

Mark may refer to:

Currency

* Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina

* East German mark, the currency of the German Democratic Republic

* Estonian mark, the currency of Estonia between 1918 and 1927

* F ...

as Caesarea or Caesarea Philippi, to distinguish it from Caesarea Maritima

Caesarea Maritima (; Greek: ''Parálios Kaisáreia''), formerly Strato's Tower, also known as Caesarea Palestinae, was an ancient city in the Sharon plain on the coast of the Mediterranean, now in ruins and included in an Israeli national par ...

and other cities named Caesarea (, ). On the death of Philip II in 34 CE his kingdom was briefly incorporated into the province of Syria, with the city given the autonomy to administer its own revenues, before reverting to his nephew, Herod Agrippa I

Herod Agrippa (Roman name Marcus Julius Agrippa; born around 11–10 BC – in Caesarea), also known as Herod II or Agrippa I (), was a grandson of Herod the Great and King of Judea from AD 41 to 44. He was the father of Herod Agrippa II, the ...

.

The ancient city is mentioned in the Gospels of Matthew and Mark

Mark may refer to:

Currency

* Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark, the currency of Bosnia and Herzegovina

* East German mark, the currency of the German Democratic Republic

* Estonian mark, the currency of Estonia between 1918 and 1927

* F ...

, under the name of Caesarea Philippi, as the place where Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

confirmed Peter's assumption that Jesus was the Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

; the place is today a place of pilgrimage for Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

.

In 61 CE, king Agrippa II

Herod Agrippa II (; AD 27/28 – or 100), officially named Marcus Julius Agrippa and sometimes shortened to Agrippa, was the last ruler from the Herodian dynasty, reigning over territories outside of Judea as a Roman client. Agrippa II fled ...

renamed the administrative capital Neronias in honor of the Roman emperor Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 unt ...

, but this name was discarded several years later, in 68 CE. Agrippa also carried out urban improvements.

In 67 CE, during the First Jewish–Roman War

The First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), sometimes called the Great Jewish Revolt ( he, המרד הגדול '), or The Jewish War, was the first of three major rebellions by the Jews against the Roman Empire, fought in Roman-controlled ...

, Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 – 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Em ...

briefly visited Caesarea Philippi before advancing on Tiberias

Tiberias ( ; he, טְבֶרְיָה, ; ar, طبريا, Ṭabariyyā) is an Israeli city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's F ...

in Galilee.

With the death of Agrippa II around 92 CE came the end of Herodian rule, and the city returned to the province of Syria

Roman Syria was an early Roman province annexed to the Roman Republic in 64 BC by Pompey in the Third Mithridatic War following the defeat of King of Armenia Tigranes the Great.

Following the partition of the Herodian Kingdom of Judea into tetr ...

.

In the late Roman and Byzantine periods the written sources name the city again as Paneas, or more seldom as Caesarea Paneas.

In 361, Emperor Julian the Apostate

Julian ( la, Flavius Claudius Julianus; grc-gre, Ἰουλιανός ; 331 – 26 June 363) was Roman emperor from 361 to 363, as well as a notable philosopher and author in Greek. His rejection of Christianity, and his promotion of Neoplat ...

instigated a religious reformation of the Roman state, in which he supported the restoration of Hellenistic polytheism as the state religion. In Paneas this was achieved by replacing Christian symbols with pagan ones, though the change was short lived.

In the 5th century, following the division of the Empire, the city was part of the Eastern (later Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

) Empire, but was lost to the Arab conquest of the Levant in the 7th century.

Early Muslim period

In 635, Paneas gained favourable terms of surrender from the Muslim army ofKhalid ibn al-Walid

Khalid ibn al-Walid ibn al-Mughira al-Makhzumi (; died 642) was a 7th-century Arab military commander. He initially headed campaigns against Muhammad on behalf of the Quraysh. He later became a Muslim and spent the remainder of his career in ...

after it had defeated Heraclius

Heraclius ( grc-gre, Ἡράκλειος, Hērákleios; c. 575 – 11 February 641), was Eastern Roman emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Africa, led a revolt ...

' forces. In 636, a second, newly formed Byzantine army advancing on Palestine used Paneas as a staging post on the way to confront the Muslim army at the final Battle of Yarmouk

The Battle of the Yarmuk (also spelled Yarmouk) was a major battle between the army of the Byzantine Empire and the Muslim forces of the Rashidun Caliphate. The battle consisted of a series of engagements that lasted for six days in August 636 ...

.

The depopulation of Paneas after the Muslim conquest was rapid, as its traditional markets disappeared. Only 14 of the 173 Byzantine sites in the area show signs of habitation from this period. The Hellenised city thus fell into a precipitous decline. At the council of al-Jabiyah, when the administration of the new territory of the Umar Caliphate was established, Paneas remained the principal city of the district of ''al-Djawlan'' (the Djawlan) in the ''jund'' (military Province) of ''Dimashq'' ( Damascus), due to its strategic military importance on the border with Jund al-Urdunn

Jund al-Urdunn ( ar, جُـنْـد الْأُرْدُنّ, translation: "The military district of Jordan") was one of the five districts of Bilad al-Sham (Islamic Syria) during the early Islamic period. It was established under the Rashidun and ...

, which comprised the Galilee and territories east and north of it.

Around 780 CE the nun Hugeburc visited Caesarea and reported that the town 'had' a church and a great many Christians, but her account does not clarify whether any of those Christians were still living in the town at the time of her visit.

The transfer of the Abbasid Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

capital from Damascus to Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesipho ...

inaugurated the flowering of the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

at the expense of the provinces.Gregorian, 2003, pp.26

38

/ref> With the decline of Abbasid power in the tenth century, Paneas found itself a provincial backwater in a slowly collapsing empire, as district governors began to exert greater autonomy and used their increasing power to make their positions hereditary. The control of Syria and Paneas passed to the

Fatimids

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dyna ...

of Egypt.

At the end of the 9th century Al-Ya'qubi reaffirms that Paneas was still the capital of al-Djawlan in the jund of Dimshq

''Jund Dimashq'' ( ar, جند دمشق) was the largest of the sub-provinces (''ajnad'', sing. ''jund''), into which Syria was divided under the Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties. It was named after its capital and largest city, Damascus ("Dimashq"), ...

, although by then the town was known as Madīnat al-Askat (city of the tribes) with its inhabitants being ''Qays

Qays ʿAylān ( ar, قيس عيلان), often referred to simply as Qays (''Kais'' or ''Ḳays'') were an Arab tribal confederation that branched from the Mudar group. The tribe does not appear to have functioned as a unit in the pre-Islamic e ...

'', mostly of the ''Banu Murra

Banu Murra () was a tribe during the era of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. They participated in the Battle of the Trench.Rodinson, ''Muhammad: Prophet of Islam'', p. 208.

They were members of the Ghatafan tribe

See also

* List of battles of Muh ...

'' with some ''Yamani'' families.

Due to the Byzantine advances under Nicephorus Phocas and John Zimisces into the Abbasid empire, a wave of refugees fled south and augmented the population of Madīnat al-Askat. The city was taken over by an extreme Shī‘ah sect of the Bedouin Qarāmita in 968. In 970 the Fatimids

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dyna ...

again briefly took control, only to lose it again to the Qarāmita. The old population of Banias along with the new refugees formed a Sunni sufi ascetic community. In 975 the Fatimid al-'Aziz wrested control in an attempt to subdue the anti-Fatimid agitation of ''Mahammad b. Ahmad al-Nablusi'' and his followers and to extend Fatimid control into Syria. al-Nabulusi’s school of ''hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

'' was to survive in Banias under the tutelage of Arab scholars such as Abú Ishaq (Ibrahim b. Hatim) and al-Balluti.

Crusader/Ayyubid period

The Crusaders' arrival in 1099 quickly split the mosaic of semi-independent cities of the Seljuk sultanate of Damascus.

The Crusaders have held the town twice, between 1129–1132 and 1140–1164.Pringle, 2009, p.

The Crusaders' arrival in 1099 quickly split the mosaic of semi-independent cities of the Seljuk sultanate of Damascus.

The Crusaders have held the town twice, between 1129–1132 and 1140–1164.Pringle, 2009, p.30

/ref> It was called by the Franks Belinas or Caesarea Philippi.Pringle, 2011, pp. 136, 184, 254. From 1126–1129, the town was held by

Assassins

An assassin is a person who commits targeted murder.

Assassin may also refer to:

Origin of term

* Someone belonging to the medieval Persian Ismaili order of Assassins

Animals and insects

* Assassin bugs, a genus in the family ''Reduviid ...

, and was turned over to the Franks following the purge of the sect from Damascus by Buri. Later on, Shams al-Mulk Isma'il attacked Banias and captured it on 11 December 1132. In 1137, Banias became under the rule of Imad al-Din Zengi

Imad al-Din Zengi ( ar, عماد الدین زنكي; – 14 September 1146), also romanized as Zangi, Zengui, Zenki, and Zanki, was a Turkmen atabeg, who ruled Mosul, Aleppo, Hama, and, later, Edessa. He was the namesake of the Zengid d ...

. In late spring 1140, Mu'in ad-Din Unur

Mu'in ad-Din Unur al-Atabeki ( tr, Muiniddin Üner; died August 28, 1149) was a Seljuk Turkish ruler of Damascus in the mid-12th century.

Origins

Mu'in ad-Din was originally a Mamluk in the army of Toghtekin, the founder of the Burid Dynasty ...

handed Banias to the Crusaders during the reign of King Fulk

Fulk ( la, Fulco, french: Foulque or ''Foulques''; c. 1089/1092 – 13 November 1143), also known as Fulk the Younger, was the count of Anjou (as Fulk V) from 1109 to 1129 and the king of Jerusalem with his wife from 1131 to his death. During t ...

, due to their assistance against Zengi's aggression towards Damascus.

With the arrival of fresh troops to the Holy Land, King Baldwin III of Jerusalem

Baldwin III (1130 – 10 February 1163) was King of Jerusalem from 1143 to 1163. He was the eldest son of Melisende and Fulk of Jerusalem. He became king while still a child, and was at first overshadowed by his mother Melisende, whom he event ...

broke the three-month-old truce of February 1157 by raiding the large flocks that the Turcoman people had pastured in the area. In that year, Banias became the principal centre of Humphrey II of Toron's fiefdom, along with his being the constable

A constable is a person holding a particular office, most commonly in criminal law enforcement. The office of constable can vary significantly in different jurisdictions. A constable is commonly the rank of an officer within the police. Other peop ...

of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem ( la, Regnum Hierosolymitanum; fro, Roiaume de Jherusalem), officially known as the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem or the Frankish Kingdom of Palestine,Example (title of works): was a Crusader state that was establish ...

, after it had first been granted to the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

by Baldwin III. The Knights Hospitaller, having fallen into an ambush, relinquished the fiefdom. On 18 May 1157, Nūr ad-Din began a siege on Banias using mangonels

The mangonel, also called the traction trebuchet, was a type of trebuchet used in Ancient China starting from the Warring States period, and later across Eurasia by the 6th century AD. Unlike the later counterweight trebuchet, the mangonel operat ...

. Humphrey in turn was under attack in Banias and Baldwin III was able to break the siege, only to be ambushed at Jacob's Ford

Daughters of Jacob Bridge ( he, גשר בנות יעקב, ''Gesher Bnot Ya'akov''; ar, جسر بنات يعقوب, ''Jisr Benat Ya'kub''). is a bridge that spans the last natural ford of the Jordan at the southern end of the Hula Basin between ...

in June 1157. The fresh troops arriving from Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

and Tripoli were able to relieve the besieged crusaders.

The Lordship of Banias which was a sub-vassal within the Lordship of Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, was captured by Nūr ad-Din on 18 November 1164. The Franks had built a castle at Hunin (Château Neuf) in 1107 to protect the trade route from Damascus to Tyre. After Nūr ad-Din's ousting of Humphrey of Toron from Banias, Hunin was at the front line securing the border defences against the Muslim garrison at Banias.

Ibn Jubayr

Ibn Jubayr (1 September 1145 – 29 November 1217; ar, ابن جبير), also written Ibn Jubair, Ibn Jobair, and Ibn Djubayr, was an Arab geographer, traveller and poet from al-Andalus. His travel chronicle describes the pilgrimage he made to M ...

, the geographer, traveller and poet from al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the Mus ...

, described Banias:

:This city is a frontier fortress of the Muslims. It is small, but has a castle, round which, under the walls flows a stream. This stream flows out from the town by one of the gates, and turns a mill ... The town has broad arable lands in the adjacent plain. Commanding the town is the fortress, still belonging to the Franks, called Hunin, which lies 3 leagues distant from Banias. The lands in the plain belong half to the Franks and half to the Muslims; and there is here the boundary called ''Hadd al Mukasimah''-"the boundary of the dividing." The Muslims and the Franks apportion the crops equally between them, and their cattle mingle freely without fear of any being stolen.”

After the death of Nūr ad-Din in May 1174, King Amalric I of Jerusalem

Amalric or Amaury I ( la, Amalricus; french: Amaury; 113611 July 1174) was King of Jerusalem from 1163, and Count of Jaffa and Ascalon before his accession. He was the second son of Melisende and Fulk of Jerusalem, and succeeded his older br ...

led the crusader forces in a siege of Banias. The Governor of Damascus allied himself with the crusaders and released all his Frankish prisoners. With the death of Amalric I in July 1174, the crusader border became unstable. In 1177, King Baldwin IV of Jerusalem laid siege to Banias and again the crusader forces withdrew after receiving tribute from Samsan al-Din Ajuk, the Governor of Banias.

In 1179, Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

took personal control of the forces of Banias and created a protective screen across the Hula through Tell al-Qadi. In 1187, Saladin's son al-Afdal was able to send a force of 7,000 horsemen from Banias, that participated in the Battle of Cresson

The Battle of Cresson was a small battle between Frankish and Ayyubid forces on 1 May 1187 at the "Spring of the Cresson." While the exact location of the spring is unknown, it is located in the environs of Nazareth. The conflict was a prelude ...

and the Battle of Hattin. By the end of Saladin's life, Banias was in the territory of al-Afdal, Emir of Damascus, and in the Iqta' of Hussam al-Din Bishara.Humphreys, 1977p. 75-77

In 1200, Sultan

al-Adil I

Al-Adil I ( ar, العادل, in full al-Malik al-Adil Sayf ad-Din Abu-Bakr Ahmed ibn Najm ad-Din Ayyub, ar, الملك العادل سيف الدين أبو بكر بن أيوب, "Ahmed, son of Najm ad-Din Ayyub, father of Bakr, the Just K ...

sent Fakhr al-Din Jaharkas to seize ''Kŭl’at es-Subeibeh'', a fortress located on a high hill above Banias, from Hussam al-Din, and reaffirmed Jaharkas as the holder of the iqta' in 1202. A strong earthquake the same year had its epicenter close to Banias, and the city was partially destroyed. Jaharkas rebuilt the ''burj'' (fortress tower). He took control of other properties - Tibnin, Hunin, Beaufort and Tyron. After his death, these lands were in the hands of Sarim ad-Din Khutluba. Shortly after the start of the Fifth Crusade

The Fifth Crusade (1217–1221) was a campaign in a series of Crusades by Western Europeans to reacquire Jerusalem and the rest of the Holy Land by first conquering Egypt, ruled by the powerful Ayyubid sultanate, led by al-Adil, brother of Sala ...

, Banias was raided by the Franks for three days. Later, Al-Mu'azzam Isa

() (1176 – 1227) was the Ayyubid emir of Damascus from 1218 to 1227. The son of Sultan al-Adil I and nephew of Saladin, founder of the dynasty, al-Mu'azzam was installed by his father as governor of Damascus in 1198 or 1200. After his father' ...

, son of al-Adil, started to dismantle fortifications across Palestine, in order to deny their protection should the Crusaders gain them, by fight or by land exchange. So, in March 1219, Khutluba was forced to relinquish Banias and destroy its fortress. Probably at the same time, the city was passed to Al-Mu'azzam's brother, al-'Aziz 'Uthman. For a while it was ruled as the hereditary principality of the dynast and his sons. The fourth prince, al-Sa'id Hasan, surrendered it to

Probably at the same time, the city was passed to Al-Mu'azzam's brother, al-'Aziz 'Uthman. For a while it was ruled as the hereditary principality of the dynast and his sons. The fourth prince, al-Sa'id Hasan, surrendered it to As-Salih Ayyub

Al-Malik as-Salih Najm al-Din Ayyub (5 November 1205 – 22 November 1249), nickname: Abu al-Futuh ( ar, أبو الفتوح), also known as al-Malik al-Salih, was the Ayyubid Kurdish ruler of Egypt from 1240 to 1249.

Early life

In 1221, as- ...

in 1247. He later tried to retake the land, at the time of An-Nasir Yusuf, but was imprisoned.

In 1252 Banias was attacked by the forces of the Seventh Crusade and took it, but they were driven by the garrison of Subeiba.

Al-Sa'id Hasan of Banias, released by Hulegu during the Mongol invasion of Syria, allied with him, and took part in the Battle of Ain Jalut

The Battle of Ain Jalut (), also spelled Ayn Jalut, was fought between the Bahri Mamluks of Egypt and the Mongol Empire on 3 September 1260 (25 Ramadan 658 AH) in southeastern Galilee in the Jezreel Valley near what is known today as the Sp ...

.

Ottoman period

The traveller J. S. Buckingham described Banias in 1825: "The present town is small, and meanly built, having no place of worship in it; and the inhabitants, who are about 500 in number, are Mohammedans and Metouali, governed by a Moslem Sheikh. In the 1870s, Banias was described as "a village, built of stone, containing about 350 Moslems, situated on a raised table-land at the bottom of the hills of Mount Hermon. The village is surrounded by gardens crowded with fruit-trees. The source of the Jordan is close by, and the water runs in little aqueducts into and under every part of the modern village."Early 20th century

The Syria-Lebanon-Palestine boundary was a product of the post-World War I Anglo-French partition of Ottoman Syria.MacMillan, 2001, pp 392-420 British forces had advanced to a position atTel Hazor

Tel Hazor ( he, תל חצור), also Chatsôr ( he, חָצוֹר), translated in LXX as Hasōr ( grc, Άσώρ), identified at Tell Waqqas / Tell Qedah el-Gul ( ar, تل القدح, Tell el-Qedah), is an archaeological tell at the site of anci ...

against Turkish troops in 1918 and wished to incorporate all the sources of the Jordan River within the British controlled Palestine. Due to the French inability to establish administrative control, the frontier between Syria and Palestine was fluid. Following the Paris Peace Conference of 1919

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, and the unratified and later annulled Treaty of Sèvres

The Treaty of Sèvres (french: Traité de Sèvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

, stemming from the San Remo conference, the 1920 boundary extended the British controlled area to north of the Sykes Picot line, a straight line between the mid point of the Sea of Galilee

The Sea of Galilee ( he, יָם כִּנֶּרֶת, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ar, بحيرة طبريا), also called Lake Tiberias, Kinneret or Kinnereth, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest f ...

and Nahariya

Nahariya ( he, נַהֲרִיָּה, ar, نهاريا) is the northernmost coastal city in Israel. In it had a population of .

Etymology

Nahariya takes its name from the stream of Ga'aton (river is ''nahar'' in Hebrew), which bisects it.

His ...

. In 1920 the French managed to assert authority over the Arab nationalist movement and after the Battle of Maysalun, King Faisal was deposed. The international boundary between Palestine and Syria was finally agreed by Great Britain and France in 1923 in conjunction with the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (french: Traité de Lausanne) was a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–23 and signed in the Palais de Rumine, Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially settled the conf ...

, after Britain had been given a League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

mandate for Palestine

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordan, both of which had been conceded by the Ottoman Empire following the end of World War I in 1918. The mandat ...

in 1922. Banyas (on the Quneitra

Quneitra (also Al Qunaytirah, Qunaitira, or Kuneitra; ar, ٱلْقُنَيْطِرَة or ٱلْقُنَيطْرَة, ''al-Qunayṭrah'' or ''al-Qunayṭirah'' ) is the largely destroyed and abandoned capital of the Quneitra Governorate in sou ...

/Tyre road) was within the French Mandate of Syria. The border was set 750 metres south of the spring.

In 1941, Australian forces occupied Banias in the advance to the Litani during the Syria-Lebanon Campaign; Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exil ...

and Indian forces also invaded Syria in the Battle of Kissoué. Banias's fate in this period was left in a state of limbo since Syria had come under British military control. When Syria was granted independence in April 1946, it refused to recognize the 1923 boundary agreed between Britain and France.

Following the 1948 Arab Israeli War

Events January

* January 1

** The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is inaugurated.

** The Constitution of New Jersey (later subject to amendment) goes into effect.

** The railways of Britain are nationalized, to form Britis ...

, the Banias spring remained in Syrian territory, while the Banias River flowed through the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) into Israel. In 1953, at one of a series of meetings to regularize administration of the DMZs, Syria offered to adjust the armistice lines, and cede to Israel 70% of the DMZ, in exchange for a return to the pre-1946 International border in the Jordan basin area, with Banias water resources returning to Syrian sovereignty. On 26 April, the Israeli cabinet met to consider the Syrian suggestions, with head of Israel's Water Planning Authority, Simha Blass

Simcha Blass (November 27, 1897 – July 18, 1982; he, שמחה בלאס) was a Polish-Israeli engineer and inventor who developed the modern drip irrigation system with his son Yeshayahu.

Biography

Simcha Blass was born in Warsaw, Poland, whic ...

, in attendance. Blass noted that while the land to be ceded to Syria was not suitable for cultivation, the Syrian map did not suit Israel's water development plan. Blass explained that the movement of the International boundary in the area of Banias would affect Israel's water rights. The Israeli cabinet rejected the Syrian proposals but decided to continue the negotiations by making changes to the accord and placing conditions on the Syrian proposals. The Israeli conditions took into account Blass's position over water rights and Syria rejected the Israeli counter-offer.

In September 1953, Israel advanced plans for its National Water Carrier to help irrigate the coastal Sharon Plain

The Sharon plain ( ''HaSharon Arabic: سهل شارون Sahel Sharon'') is the central section of the Israeli coastal plain. The plain lies between the Mediterranean Sea to the west and the Samarian Hills, to the east. It stretches from Nahal ...

and eventually the Negev desert

The Negev or Negeb (; he, הַנֶּגֶב, hanNegév; ar, ٱلنَّقَب, an-Naqab) is a desert and semidesert region of southern Israel. The region's largest city and administrative capital is Beersheba (pop. ), in the north. At its southe ...

by launching a diversion project on a nine-mile (14 km) channel midway between the Huleh Marshes and Sea of Galilee

The Sea of Galilee ( he, יָם כִּנֶּרֶת, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ar, بحيرة طبريا), also called Lake Tiberias, Kinneret or Kinnereth, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest f ...

in the central DMZ to be rapidly constructed. This prompted shelling from Syria and friction with the Eisenhower Administration

Dwight D. Eisenhower's tenure as the 34th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1953, and ended on January 20, 1961. Eisenhower, a Republican from Kansas, took office following a landslide victory ...

; the diversion was moved to the southwest.

The Banias was included in the Jordan Valley Unified Water Plan, which allocated Syria 20 million cubic metres annually from it. The plan was rejected by the Arab League. Instead, at the 2nd Arab summit conference in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo met ...

of January 1964 the League decided that Syria, Lebanon and Jordan would begin a water diversion project. Syria started the construction of canal to divert the flow of the Banias river away from Israel and along the slopes of the Golan toward the Yarmouk River. Lebanon was to construct a canal from the Hasbani River

The Hasbani River ( ar, الحاصباني / ALA-LC: ''al-Ḥāṣbānī''; he, חצבני ''Ḥatzbaní'') or Snir Stream ( he, נחל שניר / ''Nahal Sənir''), is the major tributary of the Jordan River. Local natives in the mid-19th centu ...

to Banias and complete the scheme The project was to divert 20 to 30 million cubic metres of water from the river Jordan tributaries to Syria and Jordan for the development of Syria and Jordan. The diversion plan for the Banias called for a 73 kilometre long canal to be dug 350 metres above sea level, that would link the Banias with the Yarmuk. The canal would carry the Banias's fixed flow plus the overflow from the Hasbani (including water from the Sarid and Wazani). This led to military intervention from Israel, first with tank fire and then, as the Syrians shifted the works further eastward, with airstrikes.

On June 10, 1967, the last day of the Six Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

, the Golani Brigade

The 1st "Golani" Brigade ( he, חֲטִיבַת גּוֹלָנִי) is an Israeli military infantry brigade that is subordinated to the 36th Division and traditionally associated with the Northern Command. It is one of the five infantry brigade ...

captured the village of Banias. Israel's priority on the Syrian front was to take control of the water sources. After the local residents fled to Majdal Shams

Majdal Shams ( ar, مجدل شمس; he, מַגְ'דַל שַׁמְס) is a Druze town in the southern foothills of Mount Hermon, north of the Golan Heights, known as the informal "capital" of the Golan Heights. The majority of residents are S ...

, the village was destroyed by Israeli bulldozers, leaving only the mosque, church and shrines.

Hermon Stream (Banias) Nature Reserve

In 1977, the Banias was declared a nature reserve by the

In 1977, the Banias was declared a nature reserve by the Israel Nature and Parks Authority

The Israel Nature and Parks Authority ( he, רשות הטבע והגנים ''Rashut Hateva Vehaganim''; ar, سلطة الطبيعة والحدائق) is an Israeli government organization that manages nature reserves and national parks in Israel, ...

, named Hermon Stream (Banias) Nature Reserve. It consists of two areas – the springs and the archaeological site, and the waterfall with a hanging trail.

Misidentification as biblical Laish/Dan

While Banias does not appear in theHebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

/''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

, Medieval writers such as Philostorgius, Theodoret

Theodoret of Cyrus or Cyrrhus ( grc-gre, Θεοδώρητος Κύρρου; AD 393 – 458/466) was an influential theologian of the School of Antioch, biblical commentator, and Christian bishop of Cyrrhus (423–457). He played a pi ...

, Benjamin of Tudela

Benjamin of Tudela ( he, בִּנְיָמִין מִטּוּדֶלָה, ; ar, بنيامين التطيلي ''Binyamin al-Tutayli''; Tudela, Kingdom of Navarre, 1130 Castile, 1173) was a medieval Jewish traveler who visited Europe, Asia, and ...

and Samuel ben Samson incorrectly identified it with the biblical city of Dan (also known in the Bible as Laish), now known to be located at Tel Dan. Provan, Long, Longman, 2003, pp181

/ref>Saulcy, 1854, pp

537

538 Eusebius of Caesarea accurately places Dan/Laish in the vicinity of Paneas at the fourth mile on the route to Tyre. Eusebius's identification was confirmed by E Robinson in 1838 and subsequently by archaeological excavations at both Tel Dan and Caesarea Philippi.

Notables from Banias

*Al-Wadin ibn ‘Ata al-Dimashki (d. 764 or 766) - an Arab scholar of theUmayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

era

Further reading

Water issues

*''Water for the Future: The West Bank and Gaza Strip, Israel, and Jordan'' By U.S. National Academy of Sciences, Inc NetLibrary, Jamʻīyah al-ʻIlmīyah al-Malakīyah, Committee on Sustainable Water Supplies for the Middle East, National Research Council, National Academy of Sciences (U.S.) Published by National Academies Press, 1999 , * Allan, John Anthony and Allan, Tony (2001) ''The Middle East Water Question: Hydropolitics and the Global Economy'' I.B.Tauris, *Amery, Hussein A. and Wolf, Aaron T. (2000) ''Water in the Middle East: A Geography of Peace'' University of Texas Press,See also

* Confession of Peter, New Testament event from the region of Caesarea Philippi (Banias) *List of places associated with Jesus

The New Testament narrative of the life of Jesus refers to a number of locations in the Holy Land and a Flight into Egypt. In these accounts the principal locations for the ministry of Jesus were Galilee and Judea, with activities also taking place ...

*Vassals of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Crusader state of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, created in 1099, was divided into a number of smaller seigneuries. According to the 13th-century jurist John of Ibelin, the four highest crown vassals (referred to as barons) in the kingdom pro ...

*Water politics in the Middle East

Water politics in the Middle East deals with control of the water resources of the Middle East, an arid region where issues of the use, supply, control, and allocation of water are of central economic importance. Politically contested watershed ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* al-Athīr, ʻIzz al-Dīn Ibn (Translated 2006) ''The Chronicle of Ibn Al-Athīr for the Crusading Period from Al-Kāmil Fīʼl-taʼrīkh: The Years AH 491-541/1097-1146, the Coming of the Franks And the Muslim Response'' Translated by Donald Sidney Richards Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. * * * * * * *Friedland, Elise A., "Roman Marble Sculpture from the Levant: The Group from the Sanctuary of Pan at Caesarea Philippi (Panias).” PhD Dissertation (University of Michigan 1997). * * * * * (p308

ff.) * * * *Hindley, Geoffrey. (2004) The Crusades: Islam and Christianity in the Struggle for World Supremacy Carroll & Graf Publishers, * * * *

Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

The Jewish War

*

* (pp15

* * * *Ma‘oz, Z.-U. ed., ''Excavations in the Sanctuary of Pan at Caesarea Philippi-Baniyas, 1988-1993'' (Jerusalem, forthcoming). *Ma‘oz, Z.-U., ''Baniyas: The Roman Temples'' (Qazrin: Archaostyle, 2009). *Ma‘oz, Z.-U., ''Baniyas in the Greco-Roman Period: A History Based on the Excavations'' (Qazrin: Archaostyle, 2007). *Ma‘oz, Z.-U., V. Tzaferis, and M. Hartal, “Banias,” in ''The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land'' 1 and 5 (Jerusalem 1993 and 2008), 136-143, 1587-1594. * * * * *

Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

: The Rise of the Roman Empire, Translated by Ian Scott-Kilvert Contributor F. W. Walbank

Frank William Walbank (; 10 December 1909 – 23 October 2008) was a scholar of ancient history, particularly the history of Polybius. He was born in Bingley, Yorkshire, and died in Cambridge.

Walbank attended Bradford Grammar School an ...

, Penguin Classics, 1979

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

* Tzaferis, V., and S. Israeli, ''Paneas, Volume I: The Roman to Early Islamic Periods, Excavations in Areas A, B, E, F, G, and H'' (IAA Reports 37, Jerusalem 2008).

*

External links

Israel Nature and Parks Authority

Hermon Stream (Banias) Nature Reserve

The Nahal Hermon Reserve (Banias).

''Jewish Encyclopedia''

Cæsarea Philippi

entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

Banias Travel Guide

Photo of fortifications, from 1862

* * {{National parks in the Israeli-occupied territories Hellenistic sites in Syria Archaeological sites in Quneitra Governorate Classical sites on the Golan Heights Coele-Syria Crusade places Former populated places on the Golan Heights Holy cities Jordan River basin Medieval sites on the Golan Heights New Testament cities Pan cult sites Populated places established in the 2nd century BC Ptolemaic Kingdom Roman sites in Syria 3rd-century BC establishments 1967 disestablishments Mount Hermon