Bandenbekämpfung on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In German military history, (), also referred to as Nazi security warfare during

In German military history, (), also referred to as Nazi security warfare during

In German military history, (), also referred to as Nazi security warfare during

In German military history, (), also referred to as Nazi security warfare during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, refers to the concept and military doctrine

Military doctrine is the expression of how military forces contribute to campaigns, major operations, battles, and engagements. A military doctrine outlines what military means should be used, how forces should be structured, where forces shou ...

of countering resistance or insurrection in the rear area during wartime with extreme brutality. The doctrine provided a rationale for disregarding the established laws of war

The law of war is a component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war (''jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of hostilities (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territories, ...

and for targeting any number of groups, from armed guerrillas to civilians, as "bandits" or "members of gangs". As applied by the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

and later Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, it became instrumental in the crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are certain serious crimes committed as part of a large-scale attack against civilians. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity can be committed during both peace and war and against a state's own nationals as well as ...

committed by the two regimes, including the Herero and Nama genocide

The Herero and Nama genocide or Namibian genocide, formerly known also as the Herero and Namaqua genocide, was a campaign of ethnic extermination and collective punishment waged against the Herero people, Herero (Ovaherero) and the Nama people, N ...

and the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

.

Historian Alex J. Kay estimates that around one million civilians died as a result of German anti-partisan warfare—excluding actual partisans—among the 13 to 14 million people murdered by the Nazis during World War II.

Background

According to historian and television documentary producer, Christopher Hale, there are indications that the term ''Bandenbekämpfung'' may go back as far as theThirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

. Under the German Empire established by Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (; born ''Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck''; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898) was a German statesman and diplomat who oversaw the unification of Germany and served as ...

in 1871 after the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

—formed as a union of twenty-five German states under the Hohenzollern king of Prussia— Prussian militarism flourished; martial traditions that included the military doctrine of Antoine-Henri Jomini

Antoine-Henri Jomini (; 6 March 177922 March 1869) was a Swiss-French military officer who served as a General officer, general in First French Empire, French and later in Russian Empire, Russian service, and one of the most celebrated writers o ...

's 1837 treatise, ''Summary of the Art of War'', were put into effect. Some of the theories laid out by Jomini contained instructions for intense offensive operations and the necessity of securing one's "lines of operations". German military officers took this to mean as much attention should be given to logistical operations used to fight the war at the rear as those in the front, and certainly entailed security operations. Following Jomini's lead, ''Oberstleutnant'' Albrecht von Boguslawski published lectures entitled ''Der Kleine Krieg'' ("The Small War", a literal translation of ''guerrilla''), which outlined in detail the tactical procedures related to partisan and anti-partisan warfare—likely deliberately written without clear distinctions between combatants and non-combatants. To what extent this contributed to the intensification of unrestrained warfare cannot be known, but Prussian officers like Alfred von Schlieffen

Graf Alfred von Schlieffen (; 28 February 1833 – 4 January 1913) was a German field marshal and strategist who served as chief of the Imperial German General Staff from 1891 to 1906. His name lived on in the 1905–06 " Schlieffen Plan", ...

encouraged their professional soldiers to embrace a dictum advocating that "for every problem, there was a military solution". Helmuth von Moltke the Elder

Helmuth Karl Bernhard Graf von Moltke (; 26 October 180024 April 1891) was a Kingdom of Prussia, Prussian Generalfeldmarschall, field marshal. The chief of staff of the Prussian Army for thirty years, he is regarded as the creator of a new, more ...

, Chief of the Prussian General Staff, added hostage-taking as a means of deterrence to sabotage activities and the employment of collective measures against entire communities, which became the basis for German anti-partisan policies from 1870 and remained as such through 1945.

Franco-Prussian War

Prussian security operations during the Franco-Prussian War included the use of ''Landwehr

''Landwehr'' (), or ''Landeswehr'', is a German language term used in referring to certain national army, armies, or militias found in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Europe. In different context it refers to large-scale, low-strength fo ...

'' reservists, whose duties ranged from guarding railroad lines, to taking hostages, and carrying out reprisals to deter activities of ''francs-tireurs

(; ) were irregular military formations deployed by France during the early stages of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). The term was revived and used by partisans to name two major French Resistance movements set up to fight against Nazi G ...

''. Bismarck wanted all ''francs-tireurs'' hanged or shot, and encouraged his military commanders to burn down villages that housed them. More formal structures like Chief of the Field Railway, a Military Railway Corps, District Commanders, Special Military Courts, intelligence units, and military police of varying duties and nomenclature were integrated into the Prussian system to bolster security operations all along the military's operational lines.

Boxer Rebellion and Herero Wars

Operationally, the first use of tactics later associated with ''Bandenbekämpfung'' occurred inChina

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

following the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, was an anti-foreign, anti-imperialist, and anti-Christian uprising in North China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by the Society of Righteous and Harmonious F ...

(1899–1901), after two German officers went missing. German troops conducted over fifty operations, including burning a village and taking prisoners. Soon after, the infantry received a handbook for "operations against Chinese bandits" (''Banden''). The first full application of ''Bandenbekämpfung'' in practice, was the Herero and Nama genocide

The Herero and Nama genocide or Namibian genocide, formerly known also as the Herero and Namaqua genocide, was a campaign of ethnic extermination and collective punishment waged against the Herero people, Herero (Ovaherero) and the Nama people, N ...

(1904–1908), a campaign of racial extermination and collective punishment that the German Empire undertook in German South West Africa

German South West Africa () was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles.

German rule over this territory was punctuated by ...

(modern-day Namibia

Namibia, officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country on the west coast of Southern Africa. Its borders include the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Angola and Zambia to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south; in the no ...

) against the Herero and Nama people

Nama (in older sources also called Namaqua) are an African ethnic group of South Africa, Namibia and Botswana. They traditionally speak the Khoekhoe language, Nama language of the Khoe languages, Khoe-Kwadi language family, although many Nama ...

. The genocidal campaign against the Herero people was so extreme that an estimated 66–75 percent of the population perished.

World War I

DuringWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the Imperial German Army

The Imperial German Army (1871–1919), officially referred to as the German Army (), was the unified ground and air force of the German Empire. It was established in 1871 with the political unification of Germany under the leadership of Kingdom o ...

ignored many of the commonly-understood European conventions of war when between August and October 1914, some 6,500 French and Belgian citizens were murdered. In 1914, German troops, outraged by alleged civilian "resistance", responded with mass reprisals. Though some incidents stemmed from panic, many were the result of explicit orders. Soldiers even admitted to killing civilians—including women and children—based on vague suspicions of gunfire. On some occasions, attacks against German infantry positions and patrols that may have actually been attributable to "friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy or hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while ...

" were blamed on potential ''francs-tireurs'', who were regarded as bandits and outside the rules of war, eliciting ruthless measures by German forces against civilians and villages suspected of harboring them. These German units "had received orders to show no mercy" and as a result laid waste to towns such as Andenne, Dinant, Tamines, Aarschot, and Rossignol.

Throughout the war, Germany's integrated intelligence, perimeter police, guard network, and border control measures coalesced to define the German military's security operations. Along the Eastern Front sometime in August 1915, Field Marshal Erich von Falkenhayn

Erich Georg Sebastian Anton von Falkenhayn (11 September 1861 – 8 April 1922) was a German general and Ottoman Field Marshal who served as Prussian Minister of War and Chief of the German General Staff during the First World War. Falkenha ...

established the Government General of Warsaw

The General Government of Warsaw () was an administrative civil district created by the German Empire in World War I.Liulevicius, Vejas G. (2000). ''War Land on the Eastern Front: Culture, Identity, and German Occupation in World War I''. Cambri ...

over former Congress Poland

Congress Poland or Congress Kingdom of Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It was established w ...

under General Hans von Beseler and created an infrastructure to support ongoing military operations, including guard posts, patrols, and a security network. Maintaining security meant dealing with Russian prisoners, many of whom tried to sabotage German plans and kill German soldiers, so harsh pacification measures and terror actions were carried out, including brutal reprisals against civilians, who were subsequently labeled as bandits. Before long, similar practices were instituted throughout the Eastern and Western areas of German occupied territory. Repression intensified under Ludendorff and Hindenburg’s “silent dictatorship” beginning in 1916, which interpreted Clausewitz to justify total subjugation of enemy nations.

World War II

During World War II, theGerman Army

The German Army (, 'army') is the land component of the armed forces of Federal Republic of Germany, Germany. The present-day German Army was founded in 1955 as part of the newly formed West German together with the German Navy, ''Marine'' (G ...

policy for deterring partisan or "bandit" activities against its forces was to strike "such terror into the population that it loses all will to resist". Even before the Nazi campaign in the East began, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

had already absolved his soldiers and police from any responsibility for brutality against civilians, expecting them to kill anyone that even "looked askance" at the German forces. Much of the partisan warfare became an exercise of antisemitism, as military commanders like General Anton von Mauchenheim gennant Bechtolsheim exclaimed that whenever an act of sabotage was committed and one killed the Jews from that village, then "one can be certain that one has destroyed the perpetrators, or at least those who stood behind them". Commander of ''Einsatzgruppe B'', Arthur Nebe, expressed a similar opinion when he commented: "Where there’s a partisan, there’s a Jew, and where there’s a Jew, there’s a partisan."

Following the Nazi invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

in 1939 and its reorganisation, security and policing merged with the establishment of ''Bandenbekämpfung'' operations. Aside from the groups assigned to fight partisans, additional manpower was provided by the Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

, the Kripo (criminal police), the SD, and the ''Waffen-SS''. There were a number of SS-led actions implemented against so–called "partisans" in Lemberg, Warsaw, Lublin, Kovel, and other places across Poland.

When the ''Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

'' entered Serbia in 1941, they carried out mass reprisals against alleged "partisans" by executing Jews there. The commander responsible for combating partisan warfare in 1941, General Franz Böhme, reiterated to the German forces, "that rivers of German blood" had been spilled in Serbia during the First World War and the ''Wehrmacht'' should consider any acts of violence there as "avenging these deaths".

During the Battle of Crete

The Battle of Crete (, ), codenamed Operation Mercury (), was a major Axis Powers, Axis Airborne forces, airborne and amphibious assault, amphibious operation during World War II to capture the island of Crete. It began on the morning of 20 May ...

(May 1941), German paratroopers

A paratrooper or military parachutist is a soldier trained to conduct military operations by parachuting directly into an area of operations, usually as part of a large airborne forces unit. Traditionally paratroopers fight only as light inf ...

encountered widespread resistance from the civilian population. This resistance outraged General Kurt Student

Kurt Arthur Benno Student (12 May 1890 – 1 July 1978) was a German general in the Luftwaffe during World War II. An early pioneer of airborne forces, Student was in overall command of developing a paratrooper force to be known as the ''Fallschi ...

, commander of the XI Air Corps, who ordered "revenge operations," consisting of: "1) shootings; 2) forced levies; 3) burning down villages; and 4) extermination of the male population of the entire region". General Student also demanded that "all operations be carried out with great speed, leaving aside all formalities and certainly dispensing with special courts". This contributed to a series of collective punishments against civilians in Kandanos

Kandanos or Kantanos (), also Candanos, is a town and former municipality in the Chania (regional unit), Chania regional unit, Crete, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Kantanos-Selino, of which it is a m ...

, Kondomari, and Alikianos, immediately after Crete fell. During the Axis occupation of Greece

The occupation of Greece by the Axis Powers () began in April 1941 after Nazi Germany Battle of Greece, invaded the Kingdom of Greece in order to assist its ally, Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Italy, in their Greco-Italian War, ongoing war that w ...

, the emergence of armed resistance from 1942 onward invoked mass reprisals in places such as Viannos, Kedros, Mousiotitsa, Kommeno, Lingiades, Kalavryta

Kalavryta () is a town and a municipality in the mountainous east-central part of the regional unit of Achaea, Greece. The town is located on the right bank of the river Vouraikos, south of Aigio, southeast of Patras and northwest of Tripoli, G ...

, Drakeia, Distomo :"Distomo" ''may also refer to a work by Federico García Lorca''

Distomo () is a town in western Boeotia, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Distomo-Arachova-Antikyra, of which it is the seat and a muni ...

, Mesovouno, Pyrgoi, Kaisariani

Kaisariani () is a suburban town and a municipality in the eastern part of the Athens#Athens Urban Area, Athens agglomeration in Greece.

Geography

Kaisariani is located about southeast of Athens city centre, and of the Acropolis of Athens. T ...

and Chortiatis, along with numerous other incidents of smaller scale. Generals whose units also committed war crimes under the guise of ''Bandenbekämpfung'' included Walter Stettner, commander of the 1st Mountain Division in Epirus

Epirus () is a Region#Geographical regions, geographical and historical region, historical region in southeastern Europe, now shared between Greece and Albania. It lies between the Pindus Mountains and the Ionian Sea, stretching from the Bay ...

, and Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller

Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller (29 August 1897 – 20 May 1947) was a general in the Wehrmacht of Nazi Germany during World War II. He led an infantry regiment in the early stages of the war and by 1943 was commander of the 22nd Air Landing Divisio ...

, who led the 22nd Air Landing Division in Crete.

Before invading the Soviet Union for Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along ...

, ''Reichsführer-SS

(, ) was a special title and rank that existed between the years of 1925 and 1945 for the commander of the (SS). ''Reichsführer-SS'' was a title from 1925 to 1933, and from 1934 to 1945 it was the highest Uniforms and insignia of the Schut ...

'' Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician and military leader who was the 4th of the (Protection Squadron; SS), a leading member of the Nazi Party, and one of the most powerful p ...

, and Chief of the SD Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( , ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a German high-ranking SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust. He held the rank of SS-. Many historians regard Heydrich ...

, as well as SS General Heinrich Müller briefed the ''Einsatzgruppen

(, ; also 'task forces') were (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II (1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe. The had an integral role in the imp ...

'' leaders of their responsibility to secure the rear areas—using the euphemism " special treatment"—against potential enemies; this included partisans and anyone deemed a threat by the Nazi functionaries. When Heydrich repeated this directive as an operational order (''Einsatzbefehl''), he stressed that this also meant functionaries of the Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

, Jews, and anyone of position in the communist party. This was part of the SS contribution to prevent acts they considered to be criminal in the newly conquered territories, to maintain control, and to effect the efficient establishment of miniature Nazi governments, constituted by mobile versions of the Reich Security Main Office

The Reich Security Main Office ( , RSHA) was an organization under Heinrich Himmler in his dual capacity as ''Chef der Deutschen Polizei'' (Chief of German Police) and , the head of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS). The organization's stat ...

.

Starting the same day Germany invaded the Soviet Union (22 June 1941), the 12th Infantry Division command issued orders that guerilla warfare combatants were not to be quartered as POWs

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

but were to be "sentenced on the spot by an officer", meaning they were to be summarily shot. To this end, the Nazis welcomed partisan warfare since in the mind of Hitler, such circumstances opened up "the possibility of annihilating all opposition".

On 31 July 1941, the 16th Army command were informed that any "Partisan-Battalions" formed behind the front that were not properly uniformed and without appropriate means of identification, "were to be treated as guerrillas, whether they were soldiers or not". Any civilians who provided any assistance whatsoever were to be treated likewise, which historian Omer Bartov

Omer Bartov ( ; born 1954) is an Israeli-American historian. He is the Dean's Professor of Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Brown University, where he has taught since 2000. Bartov is a historian of the Holocaust and is considered a leading au ...

claims "always meant one thing only: death by shooting or hanging". Members of the 18th Panzer Division were instructed likewise on 4 August 1941. Nearly always, these genocidal measures were "camouflaged" in reports by coded formalised language, using terms like ''Aktion'', '' Sonderbehandlung'' (special handling), or ''Umsiedlung'' (relocated).

From September 1941 onwards through the course of World War II, the term ''Bandenbekämpfung'' supplanted ''Partisanenkämpfung'' ( anti-partisan warfare) to become the guiding principle of Nazi Germany's security warfare and occupational policies; largely as a result of Himmler's insistence that for psychological reasons, bandit was somehow preferable. Himmler charged the "''Prinz Eugen''" Division to expressly deal with "partisan revolts". Units like the SS Galizien—who were likewise tasked to deal with partisans—included foreign recruits overseen by experienced German "bandit" fighters well-versed in the "mass murder of unarmed civilians".

In keeping with these extreme measures, the OKW

The (; abbreviated OKW ː kaːˈveArmed Forces High Command) was the supreme military command and control staff of Nazi Germany during World War II, that was directly subordinated to Adolf Hitler. Created in 1938, the OKW replaced the Re ...

issued orders on 13 September 1941, that "Russian soldiers who had been overrun by the German forces and had then reorganised behind the front were to be treated as partisans—that is, to be shot. It was left to the commanders on the spot to decide who belonged to this category." In late 1941, German security divisions, including the 707th, 286th, 403rd, and 221st, conducted operations in Belarus that resulted in the execution of thousands of civilians, predominantly Jews. These actions were officially reported as anti-partisan activities, but the minimal German casualties suggest that these were not genuine combat operations against armed resistance.

''Führer'' Directive 46

In July 1942, Himmler was appointed to lead the security initiatives in rear areas. One of his first actions in this role was the prohibition of the use of "partisan" to describe counter-insurgents. Bandits (''Banden'') was the term chosen to be used by German forces. Hitler insisted that Himmler was "solely responsible" for combating bandits except in districts under military administration; such districts were under the authority of the ''Wehrmacht''. The organisational changes, putting experienced SS killers in charge, and language that criminalised resistance, whether real or imagined, the transformation of security warfare into massacres. The radicalisation of "anti-bandit" warfare saw further impetus in the ''Führer'' Directive 46 of 18 August 1942, where security warfare's aim was defined as "complete extermination". The directive called on the security forces to act with "utter brutality", while providing immunity from prosecution for any acts committed during "bandit-fighting" operations. The directive designated the SS as the organisation responsible for rear-area warfare in areas under civilian administration. In areas under military jurisdiction (the Army Group Rear Areas), the Army High Command had the overall responsibility. The directive declared the entire population of "bandit" (i.e. partisan-controlled) territories as enemy combatants. In practice, this meant that the aims of security warfare was not pacification, but complete destruction and depopulation of "bandit" and "bandit-threatened" territories, turning them into "dead zones" (''Tote Zonen'').Intensification and naming a commissioner

On 23 October 1942, Himmler named SS GeneralErich von dem Bach-Zelewski

The given name Eric, Erich, Erikk, Erik, Erick, Eirik, or Eiríkur is derived from the Old Norse name ''Eiríkr'' (or ''Eríkr'' in Old East Norse due to monophthongization).

The first element, ''ei-'' may be derived from the older Proto-N ...

the "Commissioner for Anti-Bandit Warfare." Bach-Zelewski wasted little time before initiating large-scale operations dedicated to "bandit areas" with an unprecedented degree of violence. Then Himmler transferred SS General Curt von Gottberg to Belorussia to ensure that the ''Bandenbekämpfung'' operations were conducted on a permanent basis, a task which Gottberg carried out with fanatical ruthlessness, declaring the entire population bandits, Jews, Gypsies

{{Infobox ethnic group

, group = Romani people

, image =

, image_caption =

, flag = Roma flag.svg

, flag_caption = Romani flag created in 1933 and accepted at the 1971 World Romani Congress

, ...

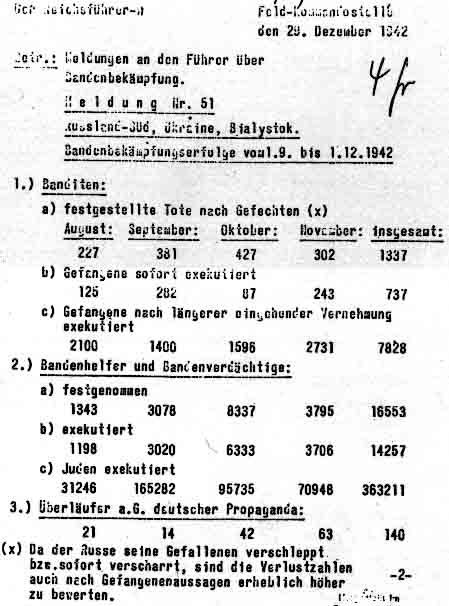

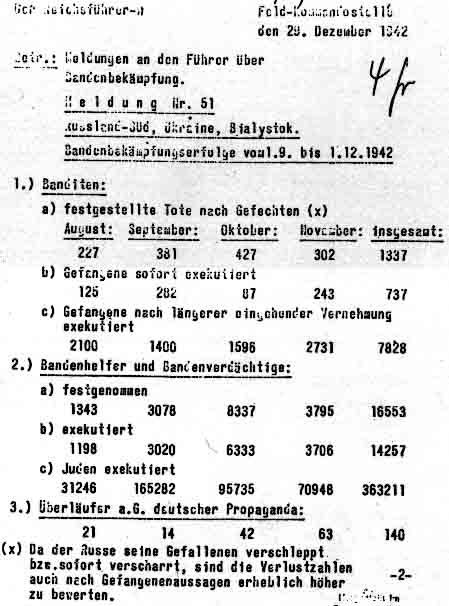

, spies, or bandit sympathisers. During Gottberg's first major operations, Operations Nürnberg and Hamburg, conducted between November through December 1942, he reported 5,000 murdered Jews, another 5,000 bandits or suspects eliminated, and 30 villages burned down.

Also in October 1942—just a couple months prior to Gottberg's exploits—''Reichsmarschall

(; ) was an honorary military rank, specially created for Hermann Göring during World War II, and the highest rank in the . It was senior to the rank of (, equivalent to field marshal, which was previously the highest rank in the ), but ...

'' Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German Nazism, Nazi politician, aviator, military leader, and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which gov ...

had ordered "anti-bandit warfare" in Army Group Rear Area Centre, which was shortly followed by an OKH

The (; abbreviated OKH) was the high command of the Army of Nazi Germany. It was founded in 1935 as part of Adolf Hitler's rearmament of Germany. OKH was ''de facto'' the most important unit within the German war planning until the defeat ...

Directive on 11 November 1942 for "anti-bandit warfare in the East" that announced sentimental considerations as "irresponsible" and instructed the men to shoot or preferably hang bandits, including women. Misgivings from commanders within Army Group Rear that such operations were counterproductive and in poor taste, since women and children were also being murdered, went ignored or resisted from Bach-Zelewski, who frequently "cited the special powers of the ''Reichsführer''." During late November 1942, forty-one "Polish-Jewish bandits" were killed in the forest area of Lubionia, which included "reprisals" against villages in the area. Another action undertaken under the auspices of anti-bandit operations occurred near Lublin in early November 1943; named ''Aktion Erntefest'' (Action Harvest Festival), SS-Police, and ''Waffen-SS'' units, accompanied by members of the Lublin police, rounded up and killed 42,000 Jews.

Over time, the ''Wehrmacht'' acculturated to the large scale anti-bandit operations, as they too came to see the entire population as criminal and complicit in any operation against German troops. Many German Army commanders were unbothered by the fact that these operations fell under the jurisdiction of the SS. Historians Ben Shepherd and Juliette Pattinson note:

As the war dragged on, the occupation's mounting economic rapacity engendered a vicious cycle of further resistance, further German brutality in response, and the erosion of order and stability across occupied Europe. Here, the issue of how occupation strategy shaped the partisan war connects with... how the nature and course of the partisan war was affected by the relationship between the occupied rear and the front line. Indeed, in eastern Europe during World War II, most directly in the Soviet Union, keeping occupied territory pacified was crucial to supplying not just the German front line, but also the German domestic population.Historian Jeff Rutherford claims that "Whilst the ''Wehrmacht'' focused on the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

, SD and other SS formations would combat any resistance movements in the rear. In effect, the German Army willingly ensnared itself in the Nazi machinery of annihilation and extermination by working with the SS to systematically suppress partisan movements and other forms of perceived resistance." To this end, ''Einsatzgruppen'', Order Police

The ''Ordnungspolizei'' (''Orpo'', , meaning "Order Police") were the uniformed police force in Nazi Germany from 1936 to 1945. The Orpo was absorbed into the Nazi monopoly of power after regional police jurisdiction was removed in favour of t ...

, ''SS-Sonderkommandos

The ''Schutzstaffel'' (; ; SS; also stylised with SS runes as ''ᛋᛋ'') was a major paramilitary organisation under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, and later throughout German-occupied Europe during World War II.

It bega ...

'', and army forces—for the most part—worked cooperatively to combat partisans ("bandits"), not only acting as judge, jury, and executioners in the field, but also in plundering "bandit areas"; they laid these areas to waste, seized crops and livestock, enslaved the local population, or murdered them. Anti-bandit operations were characterised by "special cruelty". For instance, Soviet Jews

The history of the Jews in the Soviet Union is inextricably linked to much earlier expansionist policies of the Russian Empire conquering and ruling the eastern half of the European continent already before the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. "Fo ...

were murdered outright under the pretext that they were partisans per Hitler's orders. Historian Timothy Snyder

Timothy David Snyder (born August 18, 1969) is an American historian specializing in the history of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and the Holocaust. He is on leave from his position as the Richard C. Levin, Richar ...

asserts that by the second half of 1942, "German anti-partisan operations were all but indistinguishable from the mass murder of the Jews." Other historians have made similar observations. Omer Bartov argued that under the auspices of destroying their "so-called political and biological enemies", often described as "bandits" or "partisans", the Nazis made no effort "to distinguish between real guerrillas, political suspects, and Jews."

According to historian Erich Haberer, the Nazis' murderous policies toward the Jews provided the victims little choice; driven to "coalesce into small groups to survive in forested areas from where they emerged periodically to forage food in nearby fields and villages, the Germans created their own partisan problem, which, by its very nature, was perceived as banditry." Typically these "heroic and futile acts of resistance" against the Nazi occupiers were often in vain considering the "insurmountable odds" of success, although Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto (, officially , ; ) was the largest of the Nazi ghettos during World War II and the Holocaust. It was established in November 1940 by the Nazi Germany, German authorities within the new General Government territory of Occupat ...

managed to resist for upwards of four months, which historian Patrick Henry notes, was "longer than some national armies" managed. Such activity "worked powerfully against the anti-Semitic stereotype...that Jews would not fight." Correspondingly, there are estimates that 30,000 Jews joined partisan units in Belorussia and western Ukraine alone, while other Jewish partisan groups joined fighters from Bulgaria, Greece, and Yugoslavia, where they assisted in derailing trains, destroying bridges, and carrying out sabotage acts that contributed to the deaths of thousands of German soldiers.

Surging operations from better equipped partisans against Army Group Centre

Army Group Centre () was the name of two distinct strategic German Army Groups that fought on the Eastern Front in World War II. The first Army Group Centre was created during the planning of Operation Barbarossa, Germany's invasion of the So ...

during 1943 intensified to the degree that the 221st Security Division's did not just eliminate "bandits" but laid entire regions where they operated to waste. The scale of this effort must be taken into consideration, as historian Michael Burleigh reports that anti-partisan operations had a significant impact on German operations in the East; namely, since they caused "widespread economic disruption, tied down manpower which could have been deployed elsewhere, and by instilling fear and provoking extreme countermeasures, drove a wedge between occupiers and occupied".

Following the Warsaw Uprising

The Warsaw Uprising (; ), sometimes referred to as the August Uprising (), or the Battle of Warsaw, was a major World War II operation by the Polish resistance movement in World War II, Polish underground resistance to liberate Warsaw from ...

of August 1944, the Nazis intensified their anti-partisan operations in Poland, during which German forces employed their version of anti-partisan tactics by shooting upwards of 120,000 civilians in Warsaw. Ideologically speaking, since partisans represented an immediate existential threat, in that, they were equated with Jews or people under their influence, the systematic murder of anyone associated with them was an expression of the regime's racial antisemitism and was viewed by members of the ''Wehrmacht'' as a "necessity of war". Much of this Nazi mindset in killing partisan "enemies" was not just an immediate expediency but was preemptive warfare against "future" enemies.

Varied application and development

Across western and southern Europe, the implementation of anti-bandit operations was uneven, owing to a constantly evolving set of rules of engagement, command and control disputes at the local level, and the complexity of regional politics with regard to the regime's goals in each respective nation. Historian Jeremy Black sums up the Nazi policy against perceived threats from partisans and the intensification of anti-partisan warfare in the following manner:In 1941, when there was little real partisan threat, the German use of indiscriminate brutality helped accentuate the problem. Subsequently, Soviet success on the front line that winter encouraged partisan resistance, and the Germans responded with increased mass killing...Among the German officers were fanatics who could draw no distinction between partisans and the rest of the population, as well as moderates and self-styled pragmatists, and the last had the most decisive effect on troop conduct. Diversity did not, however, lead to any marked lessening of the institutional ruthlessness that was accentuated by Nazi ideology...A lack of sufficient manpower for the extensive long-term occupation of areas susceptible to the partisans helped lead to a reliance on high-tempo brutality, a correlate of German operations at the front.

Bandit warfare and the Holocaust

Throughout the war in Europe, and especially on the Eastern Front, doctrines like ''Bandenbekämpfung'' amalgamated with the Nazi regime's genocidal plans for the racial reshaping of the Eastern Europe to secure "living space" (''Lebensraum

(, ) is a German concept of expansionism and Völkisch movement, ''Völkisch'' nationalism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' beca ...

'') for Germany. In the first eleven months of the war against the Soviet Union, German forces liquidated in excess of 80,000 alleged partisans. Besides the horrendous treatment of Soviet prisoners, the "anti-partisan" campaign in the East highlights the war’s radicalization and the ''Wehrmacht''s complicity in Nazi crimes, including the death of untold numbers of civilian men, women, and children. Implemented by units of the SS, ''Wehrmacht'', and Order Police, the Nazi regime's bandit fighting efforts across occupied Europe led to mass crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity are certain serious crimes committed as part of a large-scale attack against civilians. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity can be committed during both peace and war and against a state's own nationals as well as ...

and became an instrumental part of the Holocaust.

See also

* German anti-partisan operations in World War II * '' Hitler's Bandit Hunters: The SS and the Nazi Occupation of Europe'' * '' Marching into Darkness: The Wehrmacht and the Holocaust in Belarus'' * Myth of the clean ''Wehrmacht'' * ''Waffen-SS'' in popular cultureReferences

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Army Group Rear Area (Wehrmacht) Military doctrines The Holocaust Holocaust terminology Nazi SS Racially motivated violence German words and phrases Military-related euphemisms Rape of Belgium Herero and Nama genocide Reprisals