Baden-Powell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Baden-Powell returned to South Africa before the

Baden-Powell returned to South Africa before the  A contrary view expressed by historian Thomas Pakenham of Baden-Powell's actions during the siege argued that his success in resisting the Boers was secured at the expense of the lives of the native African soldiers and civilians, including members of his own African garrison. Pakenham claimed that Baden-Powell drastically reduced the rations to the native garrison. However, in 2001, after subsequent research, Pakenham changed this view.

During the siege, the Mafeking Cadet Corps of white boys below fighting age stood guard, carried messages, assisted in hospitals and so on, freeing grown men to fight. Baden-Powell did not form the Cadet Corps himself, and there is no evidence that he took much notice of them during the Siege. However, he was sufficiently impressed with both their courage and the equanimity with which they performed their tasks to use them later as an object lesson in the first chapter of ''Scouting for Boys''.

The siege was lifted on 17 May 1900. Baden-Powell was promoted to

A contrary view expressed by historian Thomas Pakenham of Baden-Powell's actions during the siege argued that his success in resisting the Boers was secured at the expense of the lives of the native African soldiers and civilians, including members of his own African garrison. Pakenham claimed that Baden-Powell drastically reduced the rations to the native garrison. However, in 2001, after subsequent research, Pakenham changed this view.

During the siege, the Mafeking Cadet Corps of white boys below fighting age stood guard, carried messages, assisted in hospitals and so on, freeing grown men to fight. Baden-Powell did not form the Cadet Corps himself, and there is no evidence that he took much notice of them during the Siege. However, he was sufficiently impressed with both their courage and the equanimity with which they performed their tasks to use them later as an object lesson in the first chapter of ''Scouting for Boys''.

The siege was lifted on 17 May 1900. Baden-Powell was promoted to  Baden-Powell was given the role of organising the South African Constabulary, a colonial police force, but during this phase, Baden-Powell was sent to Britain on sick leave, so he was only in command for seven months.

Baden-Powell returned to England to take up the post of Inspector-General of Cavalry in 1903. While holding this position, Baden-Powell was instrumental in reforming reconnaissance training in British cavalry, giving the force an important advantage in scouting ability over continental rivals. Also during this appointment, Baden-Powell selected the location of

Baden-Powell was given the role of organising the South African Constabulary, a colonial police force, but during this phase, Baden-Powell was sent to Britain on sick leave, so he was only in command for seven months.

Baden-Powell returned to England to take up the post of Inspector-General of Cavalry in 1903. While holding this position, Baden-Powell was instrumental in reforming reconnaissance training in British cavalry, giving the force an important advantage in scouting ability over continental rivals. Also during this appointment, Baden-Powell selected the location of

Baden-Powell was also influenced by

Baden-Powell was also influenced by  In 1929, during the

In 1929, during the  Some early Scouting " Thanks Badges" (from 1911) and the Scouting "Medal of Merit" badge had a

Some early Scouting " Thanks Badges" (from 1911) and the Scouting "Medal of Merit" badge had a

Baden-Powell published books and other texts during his years of military service both to finance his life and to generally educate his men.

* 1884: ''Reconnaissance and Scouting''

* 1885: ''Cavalry Instruction''

* 1889: ''Pigsticking or Hoghunting''

* 1896: ''The Downfall of Prempeh''

* 1897: ''The Matabele Campaign''

* 1899: ''Aids to Scouting for N.-C.Os and Men''

* 1900: ''Sport in War''

* 1901: ''Notes and Instructions for the South African Constabulary''

* 1907: ''Sketches in Mafeking and East Africa''

* 1910: ''British Discipline'', Essay 32 of Essays on Duty and Discipline

* 1914: ''Quick Training for War''

Baden-Powell was regarded as an excellent storyteller. During his whole life he told "ripping yarns" to audiences. After having published ''Scouting for Boys'', Baden-Powell kept on writing more handbooks and educative materials for all Scouts, as well as directives for Scout Leaders. In his later years, he also wrote about the Scout movement and his ideas for its future. He spent most of the last two years of his life in Africa, and many of his later books had African themes.

* 1908: ''

Baden-Powell published books and other texts during his years of military service both to finance his life and to generally educate his men.

* 1884: ''Reconnaissance and Scouting''

* 1885: ''Cavalry Instruction''

* 1889: ''Pigsticking or Hoghunting''

* 1896: ''The Downfall of Prempeh''

* 1897: ''The Matabele Campaign''

* 1899: ''Aids to Scouting for N.-C.Os and Men''

* 1900: ''Sport in War''

* 1901: ''Notes and Instructions for the South African Constabulary''

* 1907: ''Sketches in Mafeking and East Africa''

* 1910: ''British Discipline'', Essay 32 of Essays on Duty and Discipline

* 1914: ''Quick Training for War''

Baden-Powell was regarded as an excellent storyteller. During his whole life he told "ripping yarns" to audiences. After having published ''Scouting for Boys'', Baden-Powell kept on writing more handbooks and educative materials for all Scouts, as well as directives for Scout Leaders. In his later years, he also wrote about the Scout movement and his ideas for its future. He spent most of the last two years of his life in Africa, and many of his later books had African themes.

* 1908: ''

In January 1912, Baden-Powell was en route to New York on a Scouting World Tour, on the ocean liner , when he met Olave St Clair Soames. She was 23, while he was 55; they shared the same birthday, 22 February. They became engaged in September of the same year, causing a media sensation due to Baden-Powell's fame. To avoid press intrusion, they married in private on 30 October 1912, at St Peter's Church in

In January 1912, Baden-Powell was en route to New York on a Scouting World Tour, on the ocean liner , when he met Olave St Clair Soames. She was 23, while he was 55; they shared the same birthday, 22 February. They became engaged in September of the same year, causing a media sensation due to Baden-Powell's fame. To avoid press intrusion, they married in private on 30 October 1912, at St Peter's Church in  The couple lived in Pax Hill near Bentley, Hampshire, from about 1919 until 1939. The Bentley house was a gift from her father. After they married, Baden-Powell began to suffer persistent headaches which were considered by his doctor to be

The couple lived in Pax Hill near Bentley, Hampshire, from about 1919 until 1939. The Bentley house was a gift from her father. After they married, Baden-Powell began to suffer persistent headaches which were considered by his doctor to be  Baden-Powell and his wife were parents of Arthur Robert Peter (1913–1962), who succeeded his father in the barony; Heather Grace (1915–1986), who married John Hall King (1913–2004) and had two sons, the elder of whom, Michael, was killed in the sinking of in 1966; and Betty St Clair (1917–2004). When Olave's sister Auriol Davidson (née Soames) died in 1919, Olave and Robert took her three daughters into their family and brought them up as their own children.

Three of Baden-Powell's many biographers comment on his sexuality; the first two (in 1979 and 1986) focused on his relationship with his close friend

Baden-Powell and his wife were parents of Arthur Robert Peter (1913–1962), who succeeded his father in the barony; Heather Grace (1915–1986), who married John Hall King (1913–2004) and had two sons, the elder of whom, Michael, was killed in the sinking of in 1966; and Betty St Clair (1917–2004). When Olave's sister Auriol Davidson (née Soames) died in 1919, Olave and Robert took her three daughters into their family and brought them up as their own children.

Three of Baden-Powell's many biographers comment on his sexuality; the first two (in 1979 and 1986) focused on his relationship with his close friend

* Commissioned

* Commissioned

In 1937 Baden-Powell was appointed to the

In 1937 Baden-Powell was appointed to the

In 1931, Major

In 1931, Major

Lieutenant-General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

Robert Stephenson Smyth Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, ( ; (Commonly pronounced by others as ) 22 February 1857 – 8 January 1941) was a British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gur ...

officer, writer, founder and first Chief Scout A Chief Scout is the principal or head scout for an organization such as the military, colonial administration or expedition or a talent scout in performing, entertainment or creative arts, particularly sport. In sport, a Chief Scout can be the prin ...

of the world-wide Scout Movement

Scouting, also known as the Scout Movement, is a worldwide youth Social movement, movement employing the Scout method, a program of informal education with an emphasis on practical outdoor activities, including camping, woodcraft, aquatics, hik ...

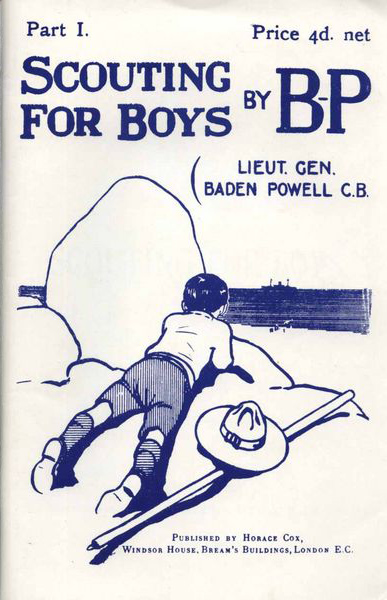

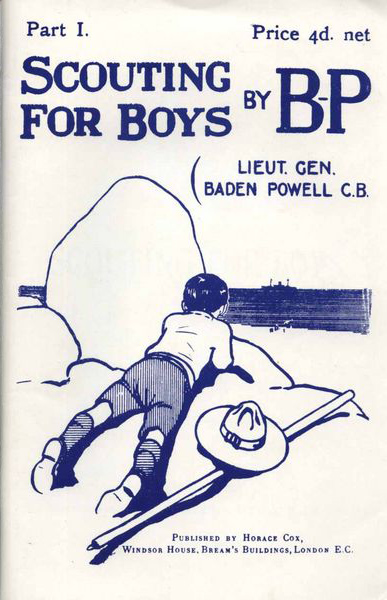

, and founder, with his sister Agnes, of the world-wide Girl Guide / Girl Scout Movement. Baden-Powell authored the first editions of the seminal work ''Scouting for Boys

''Scouting for Boys: A handbook for instruction in good citizenship'' is a book on Boy Scout training, published in various editions since 1908. Early editions were written and illustrated by Robert Baden-Powell with later editions being extens ...

'', which was an inspiration for the Scout Movement.

Educated at Charterhouse School

(God having given, I gave)

, established =

, closed =

, type = Public school Independent day and boarding school

, religion = Church of England

, president ...

, Baden-Powell served in the British Army from 1876 until 1910 in India and Africa. In 1899, during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

in South Africa, Baden-Powell successfully defended the town in the Siege of Mafeking

The siege of Mafeking was a 217-day siege battle for the town of Mafeking (now called Mafikeng) in South Africa during the Second Boer War from October 1899 to May 1900. The siege received considerable attention as Lord Edward Cecil, the son of ...

. Several of his books, written for military reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops ( skirmishe ...

and scout training in his African years, were also read by boys. In August 1907, he held a demonstration camp, the Brownsea Island Scout camp

The Brownsea Island Scout camp was the site of a boys' camping event on Brownsea Island in Poole Harbour, southern England, organised by Lieutenant-General Baden-Powell to test his ideas for the book '' Scouting for Boys''. Boys from different ...

, which is now seen as the beginning of Scouting. Based on his earlier books, particularly ''Aids to Scouting'', he wrote ''Scouting for Boys

''Scouting for Boys: A handbook for instruction in good citizenship'' is a book on Boy Scout training, published in various editions since 1908. Early editions were written and illustrated by Robert Baden-Powell with later editions being extens ...

'', published in 1908 by Sir Arthur Pearson

''Sir'' is a formal honorific address in English for men, derived from Sire in the High Middle Ages. Both are derived from the old French "Sieur" (Lord), brought to England by the French-speaking Normans, and which now exist in French only ...

, for boy readership. In 1910 Baden-Powell retired from the army and formed The Scout Association

The Scout Association is the largest Scouting organisation in the United Kingdom and is the World Organization of the Scout Movement's recognised member for the United Kingdom. Following the origin of Scouting in 1907, the association was f ...

.

The first Scout Rally was held at The Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace was a cast iron and plate glass structure, originally built in Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The exhibition took place from 1 May to 15 October 1851, and more than 14,000 exhibitors from around ...

in 1909. Girls in Scout uniform attended, telling Baden-Powell that they were the "Girl Scouts". In 1910, Baden-Powell and his sister Agnes Baden-Powell

Agnes Smyth Baden-Powell (16 December 1858 – 2 June 1945) was the younger sister of Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, and was most noted for her work in establishing the Girl Guide movement as a female counterpart to her older bro ...

started the Girl Guide and Girl Scout

A Girl Guide or Girl Scout is a member of a section of some Guiding organisations who is between the ages of 10 and 14. Age limits are different in each organisation. The term Girl Scout is used in the United States and several East Asian co ...

organisation. In 1912 he married Olave St Clair Soames. He gave guidance to the Scout and Girl Guide movements until retiring in 1937. Baden-Powell lived his last years in Nyeri

Nyeri is a town situated in the Central Highlands of Kenya. It is the county headquarters of Nyeri County. The town was the central administrative headquarters of the country's former Central Province. Following the dissolution of the former pr ...

, Kenya, where he died and was buried in 1941. His grave is a national monument

A national monument is a monument constructed in order to commemorate something of importance to national heritage, such as a country's founding, independence, war, or the life and death of a historical figure.

The term may also refer to a sp ...

.

Early life

Baden-Powell was a son ofBaden Powell Baden-Powell () is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

Baden-Powell

* The Rev. Prof. Baden Powell (mathematician) (1796–1860), mathematician, clergyman and liberal theologian.

By his first marriage father of:

:* Baden Henry Powell ...

, Savilian Professor of Geometry

The position of Savilian Professor of Geometry was established at the University of Oxford in 1619. It was founded (at the same time as the Savilian Professorship of Astronomy) by Sir Henry Savile, a mathematician and classical scholar who was ...

at Oxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

and Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britai ...

priest, and his third wife, Henrietta Grace Smyth, eldest daughter of Admiral William Henry Smyth

Admiral William Henry Smyth (21 January 1788 – 8 September 1865) was a Royal Navy officer, hydrographer, astronomer and numismatist. He is noted for his involvement in the early history of a number of learned societies, for his hydrographic ...

. After Baden Powell died in 1860, his widow, to identify her children with her late husband's fame, and to set her own children apart from their half-siblings and cousins, styled the family name ''Baden-Powell''. The name was eventually legally changed by Royal Licence on 30 April 1902.

The family of Baden-Powell's father originated in Suffolk. His mother's earliest known Smyth ancestor was a Royalist American colonist; her mother

]

A mother is the female parent of a child. A woman may be considered a mother by virtue of having given birth, by raising a child who may or may not be her biological offspring, or by supplying her ovum for fertilisation in the case of ge ...

's father Thomas Warington was the British Consul (representative), Consul in Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

around 1800.

Baden-Powell was born as Robert Stephenson Smyth Powell at 6 Stanhope Street (now 11 Stanhope Terrace), Paddington

Paddington is an area within the City of Westminster, in Central London. First a medieval parish then a metropolitan borough, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Three important landmarks of the district are Padd ...

, London, on 22 February 1857. He was called Stephe (pronounced "Stevie") by his family. He was named after his godfather, Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson FRS HFRSE FRSA DCL (16 October 1803 – 12 October 1859) was an English civil engineer and designer of locomotives. The only son of George Stephenson, the "Father of Railways", he built on the achievements of his father. ...

, the railway and civil engineer, and his third name was his mother's surname.

Baden-Powell had four older half-siblings from the second of his father's two previous marriages, and was the sixth child of his father's third marriage:

* Warington (1847–1921)

* George (1847–1898)

* Augustus ("Gus") (1849–1863), who was often ill and died young

* Francis

Francis may refer to:

People

*Pope Francis, the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State and Bishop of Rome

* Francis (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Francis (surname)

Places

*Rural ...

("Frank") (1850–1933)

* Henrietta Smyth, 28 October 1851 – 9 March 1854

* John Penrose Smyth, 21 December 1852 – 14 December 1855

* Jessie Smyth 25 November 1855 – 24 July 1856

* B–P (22 February 1857 – 8 January 1941)

* Agnes (1858–1945)

* Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in South Germany, in earlier times on both sides of the Upper Rhine but since the Napoleonic Wars only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Baden originated from the House of Zähringen. Baden ...

(1860–1937)

The three children immediately preceding B–P had all died very young before he was born.

Baden-Powell's father died when he was three. Subsequently, Baden-Powell was raised by his mother, a strong woman who was determined that her children would succeed. In 1933 he said of her "The whole secret of my getting on, lay with my mother."

He attended Rose Hill School, Tunbridge Wells

Royal Tunbridge Wells is a town in Kent, England, southeast of central London. It lies close to the border with East Sussex on the northern edge of the High Weald, whose sandstone geology is exemplified by the rock formation High Rocks. ...

and was given a scholarship to Charterhouse, a prestigious public school named after the ancient Carthusian monastery buildings it occupied in the City of London. However while he was a pupil there, the school moved out to new purpose-built premises in the countryside near Godalming

Godalming is a market town and civil parish in southwest Surrey, England, around southwest of central London. It is in the Borough of Waverley, at the confluence of the Rivers Wey and Ock. The civil parish covers and includes the settleme ...

in Surrey. He played the piano and violin, was an ambidextrous

Ambidexterity is the ability to use both the right and left hand equally well. When referring to objects, the term indicates that the object is equally suitable for right-handed and left-handed people. When referring to humans, it indicates that ...

artist, and enjoyed acting. Holidays were spent on yachting

Yachting is the use of recreational boats and ships called '' yachts'' for racing or cruising. Yachts are distinguished from working ships mainly by their leisure purpose. "Yacht" derives from the Dutch word '' jacht'' ("hunt"). With sailboat ...

or canoeing

Canoeing is an activity which involves paddling a canoe with a single-bladed paddle. Common meanings of the term are limited to when the canoeing is the central purpose of the activity. Broader meanings include when it is combined with other ac ...

expeditions with his brothers. Baden-Powell's first introduction to Scouting skills was through stalking and cooking game while avoiding teachers in the nearby woods, which were strictly out-of-bounds.

Military career

In 1876 Baden-Powell joined the13th Hussars

The 13th Hussars (previously the 13th Light Dragoons) was a cavalry regiment of the British Army established in 1715. It saw service for three centuries including the Napoleonic Wars, the Crimean War and the First World War but then amalgamated w ...

in India with the rank of lieutenant. He enhanced and honed his military scouting skills amidst the Zulu in the early 1880s in the Natal Province

The Province of Natal (), commonly called Natal, was a province of South Africa from May 1910 until May 1994. Its capital was Pietermaritzburg. During this period rural areas inhabited by the black African population of Natal were organized into ...

of South Africa, where his regiment had been posted, and where he was Mentioned in Dispatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches, MiD) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face ...

. Baden-Powell's skills impressed his superiors and in 1890 he was brevetted Major as Military Secretary and senior Aide-de-camp to the Commander-in-Chief and Governor of Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, his uncle General Sir Henry Augustus Smyth. He was posted to Malta for three years, also working as intelligence officer for the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on th ...

for the Director of Military Intelligence. He frequently travelled disguised as a butterfly collector, incorporating plans of military installations into his drawings of butterfly wings. In 1884 he published ''Reconnaissance and Scouting''.

Baden-Powell returned to Africa in 1896, and served in the Second Matabele War

The Second Matabele War, also known as the Matabeleland Rebellion or part of what is now known in Zimbabwe as the First '' Chimurenga'', was fought between 1896 and 1897 in the region later known as Southern Rhodesia, now modern-day Zimbabwe ...

, in the expedition to relieve British South Africa Company

The British South Africa Company (BSAC or BSACo) was chartered in 1889 following the amalgamation of Cecil Rhodes' Central Search Association and the London-based Exploring Company Ltd, which had originally competed to capitalize on the expect ...

personnel under siege in Bulawayo

Bulawayo (, ; Ndebele: ''Bulawayo'') is the second largest city in Zimbabwe, and the largest city in the country's Matabeleland region. The city's population is disputed; the 2022 census listed it at 665,940, while the Bulawayo City Council ...

. This was a formative experience for him not only because he commanded reconnaissance missions into enemy territory in the Matopos Hills, but because many of his later Boy Scout ideas took hold here. It was during this campaign that he first met and befriended the American scout Frederick Russell Burnham

Frederick Russell Burnham DSO (May 11, 1861 – September 1, 1947) was an American scout and world-traveling adventurer. He is known for his service to the British South Africa Company and to the British Army in colonial Africa, and for teac ...

, who introduced Baden-Powell to stories of the American Old West

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of American expansion in mainland North America that began with European colonial ...

and woodcraft (i.e., Scoutcraft

Scoutcraft is a term used to cover a variety of woodcraft knowledge and skills required by people seeking to venture into wild country and sustain themselves independently. The term has been adopted by Scouting organizations to reflect skills and ...

), and here that he was introduced for the first time to the Montana Peaked version of a western cowboy hat, of which Stetson

Stetson is a brand of hat manufactured by the John B. Stetson Company. "Stetson" is also used as a generic trademark to refer to any campaign hat, in particular, in Scouting.

John B. Stetson gained inspiration for his most famous hats when ...

was a prolific manufacturer, and which also came to be known as a campaign hat and the many versatile and practical uses of a neckerchief

A neckerchief (from ''neck'' (n.) + ''kerchief''), sometimes called a necker, kerchief or scarf, is a type of neckwear associated with those working or living outdoors, including farm labourers, cowboys and sailors. It is most commonly still se ...

.

Baden-Powell was accused of illegally executing a prisoner of war in 1896, the Matabele chief Uwini, who had been promised his life would be spared if he surrendered. Uwini was sentenced to be shot by firing squad by a military court, a sentence Baden-Powell confirmed. Baden-Powell was cleared by a military court of inquiry but the colonial civil authorities wanted a civil investigation and trial. Baden-Powell later claimed he was "released without a stain on my character".

After Rhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to th ...

, Baden-Powell served in the Fourth Ashanti War

The Anglo-Ashanti wars were a series of five conflicts that took place between 1824 and 1900 between the Ashanti Empire—in the Akan interior of the Gold Coast—and the British Empire and its African allies. Though the Ashanti emerged victori ...

in Gold Coast. In 1897, at the age of 40, he was brevetted colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

(the youngest colonel in the British Army) and given command of the 5th Dragoon Guards

The 5th (Princess Charlotte of Wales's) Dragoon Guards was a British army cavalry regiment, officially formed in January 1686 as Shrewsbury's Regiment of Horse. Following a number of name changes, it became the 5th (Princess Charlotte of Wales's) ...

in India. A few years later he wrote a small manual, entitled ''Aids to Scouting'', a summary of lectures he had given on the subject of military scouting, much of it a written explanation of the lessons he had learned from Burnham, to help train recruits.

Baden-Powell returned to South Africa before the

Baden-Powell returned to South Africa before the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South ...

. Although instructed to maintain a mobile mounted force on the frontier with the Boer Republics, Baden-Powell amassed stores and established a garrison at Mafeking. The subsequent Siege of Mafeking

The siege of Mafeking was a 217-day siege battle for the town of Mafeking (now called Mafikeng) in South Africa during the Second Boer War from October 1899 to May 1900. The siege received considerable attention as Lord Edward Cecil, the son of ...

lasted 217 days. Although Baden-Powell could have destroyed his stores and had sufficient forces to break out throughout much of the siege, especially since the Boers lacked adequate artillery to shell the town or its forces, he remained in the town to the point of his intended mounted soldiers eating their horses. The town had been surrounded by a Boer army, at times in excess of 8,000 men.

The siege of the small town received much attention from both the Boers and international media because Lord Edward Cecil

Lord Edward Herbert Gascoyne-Cecil (12 July 1867 – 13 December 1918), known as Lord Edward Cecil, was a distinguished and highly decorated English soldier. As colonial administrator in Egypt and advisor to the Liberal government, he helped ...

, the son of the British Prime Minister, was besieged in the town. The garrison held out until relieved, in part thanks to cunning deceptions, many devised by Baden-Powell. Fake minefields were planted and his soldiers pretended to avoid non-existent barbed wire

A close-up view of a barbed wire

Roll of modern agricultural barbed wire

Barbed wire, also known as barb wire, is a type of steel fencing wire constructed with sharp edges or points arranged at intervals along the strands. Its primary use is ...

while moving between trenches. Baden-Powell did much reconnaissance work himself. In one instance, noting that the Boers had not removed the rail line, Baden-Powell loaded an armoured locomotive with sharpshooters and sent it down the rails into the heart of the Boer encampment and back again in a successful attack.

A contrary view expressed by historian Thomas Pakenham of Baden-Powell's actions during the siege argued that his success in resisting the Boers was secured at the expense of the lives of the native African soldiers and civilians, including members of his own African garrison. Pakenham claimed that Baden-Powell drastically reduced the rations to the native garrison. However, in 2001, after subsequent research, Pakenham changed this view.

During the siege, the Mafeking Cadet Corps of white boys below fighting age stood guard, carried messages, assisted in hospitals and so on, freeing grown men to fight. Baden-Powell did not form the Cadet Corps himself, and there is no evidence that he took much notice of them during the Siege. However, he was sufficiently impressed with both their courage and the equanimity with which they performed their tasks to use them later as an object lesson in the first chapter of ''Scouting for Boys''.

The siege was lifted on 17 May 1900. Baden-Powell was promoted to

A contrary view expressed by historian Thomas Pakenham of Baden-Powell's actions during the siege argued that his success in resisting the Boers was secured at the expense of the lives of the native African soldiers and civilians, including members of his own African garrison. Pakenham claimed that Baden-Powell drastically reduced the rations to the native garrison. However, in 2001, after subsequent research, Pakenham changed this view.

During the siege, the Mafeking Cadet Corps of white boys below fighting age stood guard, carried messages, assisted in hospitals and so on, freeing grown men to fight. Baden-Powell did not form the Cadet Corps himself, and there is no evidence that he took much notice of them during the Siege. However, he was sufficiently impressed with both their courage and the equanimity with which they performed their tasks to use them later as an object lesson in the first chapter of ''Scouting for Boys''.

The siege was lifted on 17 May 1900. Baden-Powell was promoted to major-general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

and became a national hero. However, British military commanders were more critical of his performance and even less impressed with his subsequent choices to again allow himself to be besieged. Ultimately, his failure to understand properly the situation, and abandonment of the soldiers, mostly Australian

Australian(s) may refer to:

Australia

* Australia, a country

* Australians, citizens of the Commonwealth of Australia

** European Australians

** Anglo-Celtic Australians, Australians descended principally from British colonists

** Aboriginal ...

s and Rhodesians, at the Battle of Elands River Pakenham claimed led to his being removed from action.

Briefly back in the United Kingdom in October 1901, Baden-Powell was invited to visit King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until Death and state funeral of Edward VII, his death in 1910.

The second chil ...

at Balmoral, the monarch's Scottish retreat, and personally invested as Companion of the Order of the Bath

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a care ...

(CB).

Baden-Powell was given the role of organising the South African Constabulary, a colonial police force, but during this phase, Baden-Powell was sent to Britain on sick leave, so he was only in command for seven months.

Baden-Powell returned to England to take up the post of Inspector-General of Cavalry in 1903. While holding this position, Baden-Powell was instrumental in reforming reconnaissance training in British cavalry, giving the force an important advantage in scouting ability over continental rivals. Also during this appointment, Baden-Powell selected the location of

Baden-Powell was given the role of organising the South African Constabulary, a colonial police force, but during this phase, Baden-Powell was sent to Britain on sick leave, so he was only in command for seven months.

Baden-Powell returned to England to take up the post of Inspector-General of Cavalry in 1903. While holding this position, Baden-Powell was instrumental in reforming reconnaissance training in British cavalry, giving the force an important advantage in scouting ability over continental rivals. Also during this appointment, Baden-Powell selected the location of Catterick Garrison

Catterick Garrison is a major garrison and military town south of Richmond, North Yorkshire, England. It is the largest British Army garrison in the world, with a population of around 13,000 in 2017 and covering over 2,400 acres (about ...

to replace Richmond Castle

Richmond Castle in Richmond, North Yorkshire, England, stands in a commanding position above the River Swale, close to the centre of the town of Richmond. It was originally called Riche Mount, 'the strong hill'. The castle was constructed by Al ...

which was then the Headquarters of the Northumbrian Division. Baden-Powell was a career cavalryman, but realised that cavalry was no match against the machine gun; however, his superiors, Kitchener and French were also career cavalrymen, and still regarded the cavalry as indispensable, with the result that cavalry was used in the First World War with little effect, yet the major item exported from Britain to Flanders during the War was horse fodder.

In 1907 Baden-Powell was promoted to Lieutenant-General but was on the inactive list - possibly at his request, for this was when the Scout Movement was starting to "move", and Baden-Powell had his experimental camp on Brownsea Island (see below).

In October 1907 Baden-Powell was appointed to the command of the Northumbrian Division of the newly formed Territorial Army.

On 19 February 1909 Baden-Powell sailed in the SS ''Aragon'' via Portugal and Spain to South America, for what seems to have been just a holiday, a trip not related to either the Army nor to Scouting. However, the Foreign Intelligence section in the Belfast Newsletter reported that when in March 1909 he visited Santiago de Chile for three days, "He was given a warmer reception than had ever been afforded a foreigner in South America." He sailed back in the RMS Danube by 1 May 1909.

In 1910, aged 53, Baden-Powell retired from the Army. One account has it that Lord Kitchener Lord Kitchener may refer to:

* Earl Kitchener, for the title

* Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener

Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, (; 24 June 1850 – 5 June 1916) was a senior British Army officer and colonial administrator. ...

said that he "could lay his hand on several competent divisional generals but could find no one who could carry on the invaluable work of the Boy Scouts". Baden-Powell wrote that this came from the King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the ...

, which seems more likely, as the King had introduced the King's Scout Award in 1909 and Army officers held a Commission signed by the King, while Kitchener had nothing to do with the Scout Movement.

In 1915, Baden-Powell's book "My Adventures as a Spy" was published, which was interpreted as indicating that he had been active as a spy during that war.

Scouting movement

On his return from Africa in 1903, Baden-Powell found that his military training manual, ''Aids to Scouting'', had become a best-seller, and was being used by teachers and youth organisations, includingCharlotte Mason

Charlotte Maria Shaw Mason (1 January 1842 – 16 January 1923) was a British educator and reformer in England at the turn of the twentieth century. She proposed to base the education of children upon a wide and liberal curriculum. She was ins ...

's House of Education. Following his involvement in the Boys' Brigade

The Boys' Brigade (BB) is an international interdenominational Christian youth organisation, conceived by the Scottish businessman Sir William Alexander Smith to combine drill and fun activities with Christian values. Following its inception ...

as a Brigade Vice-President and Officer in charge of its scouting section, with encouragement from his friend, William Alexander Smith, Baden-Powell decided to re-write ''Aids to Scouting'' to suit a youth readership. In August 1907 he held a camp on Brownsea Island to test out his ideas. About twenty boys attended: eight from local Boys' Brigade companies, and about twelve public school boys, mostly sons of his friends.

Baden-Powell was also influenced by

Baden-Powell was also influenced by Ernest Thompson Seton

Ernest Thompson Seton (born Ernest Evan Thompson August 14, 1860 – October 23, 1946) was an English-born Canadian-American author, wildlife artist, founder of the Woodcraft Indians in 1902 (renamed Woodcraft League of America), and one of ...

, who founded the Woodcraft Indians

Woodcraft League of America, originally called the Woodcraft Indians and League of Woodcraft Indians, is a youth program, established by Ernest Thompson Seton in 1901. Despite the name, the program was created for non- Indian children. At first t ...

. Seton gave Baden-Powell a copy of his book ''The Birch Bark Roll of the Woodcraft Indians'' and they met in 1906. The first book on the Scout Movement, Baden-Powell's ''Scouting for Boys

''Scouting for Boys: A handbook for instruction in good citizenship'' is a book on Boy Scout training, published in various editions since 1908. Early editions were written and illustrated by Robert Baden-Powell with later editions being extens ...

'' was published in six instalments in 1908, and has sold approximately 150 million copies as the fourth best-selling book of the 20th century.

Boys and girls spontaneously formed Scout troops and the Scouting Movement started spontaneously, first as a national, and soon an international phenomenon. A rally of Scouts was held at Crystal Palace

Crystal Palace may refer to:

Places Canada

* Crystal Palace Complex (Dieppe), a former amusement park now a shopping complex in Dieppe, New Brunswick

* Crystal Palace Barracks, London, Ontario

* Crystal Palace (Montreal), an exhibition buildin ...

in London in 1909, at which Baden-Powell met some of the first Girl Scouts

Girl Guides (known as Girl Scouts in the United States and some other countries) is a worldwide movement, originally and largely still designed for girls and women only. The movement began in 1909 when girls requested to join the then-grassroot ...

. The Girl Guides were subsequently formed in 1910 under the auspices of Baden-Powell's sister, Agnes Baden-Powell. In 1912, Baden-Powell started a world tour with a voyage to the Caribbean. Another passenger was Juliette Gordon Low

Juliette Gordon Low (October 31, 1860 – January 17, 1927) was the American founder of Girl Scouts of the USA. Inspired by the work of Lord Baden-Powell, founder of Boy Scouts, she joined the Girl Guide movement in England, forming her own gr ...

, an American who had been running a Guide Company in Scotland, and was returning to the U.S.A. Baden-Powell encouraged her to found the Girl Scouts of the USA

Girl Scouts of the United States of America (GSUSA), commonly referred to as simply Girl Scouts, is a youth organization for girls in the United States and American girls living abroad. Founded by Juliette Gordon Low in 1912, it was organized ...

.

In 1929, during the

In 1929, during the 3rd World Scout Jamboree

The 3rd World Scout Jamboree was held in 1929 at Arrowe Park in Upton, near Birkenhead, Wirral, United Kingdom. As it was commemorating the 21st birthday of ''Scouting for Boys'' and the Scouting movement, it is also known as the Coming of Age ...

, he received as a present a new 20-horsepower Rolls-Royce

Rolls-Royce (always hyphenated) may refer to:

* Rolls-Royce Limited, a British manufacturer of cars and later aero engines, founded in 1906, now defunct

Automobiles

* Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, the current car manufacturing company incorporated ...

car (chassis number GVO-40, registration OU 2938) and an Eccles Caravan

Caravan or caravans may refer to:

Transport and travel

*Caravan (travellers), a group of travellers journeying together

**Caravanserai, a place where a caravan could stop

*Camel train, a convoy using camels as pack animals

*Convoy, a group of veh ...

. This combination well served the Baden-Powells in their further travels around Europe. The caravan was nicknamed Eccles and is now on display at Gilwell Park. The car, nicknamed Jam Roll, was sold after his death by Olave Baden-Powell

Olave St Clair Baden-Powell, Baroness Baden-Powell (''née'' Soames; 22 February 1889 – 25 June 1977) was the first Chief Guide for Britain and the wife of Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, the founder of Scouting and co-founder o ...

in 1945. Jam Roll and Eccles were reunited at Gilwell for the 21st World Scout Jamboree

The 21st World Scout Jamboree was held in July and August 2007, and formed a part of the Scouting 2007 Centenary celebrations of the world Scout Movement. The event was hosted by the United Kingdom, as 2007 marked the 100th anniversary of the found ...

in 2007. It has been purchased on behalf of Scouting and is owned by a charity, B–P Jam Roll Ltd. Funds are being raised to repay the loan that was used to purchase the car.

Baden-Powell also had a positive impact on improvements in youth education. Under his dedicated command the world Scouting Movement grew. By 1922 there were more than a million Scouts in 32 countries; by 1939 the number of Scouts was in excess of 3.3 million.

Some early Scouting " Thanks Badges" (from 1911) and the Scouting "Medal of Merit" badge had a

Some early Scouting " Thanks Badges" (from 1911) and the Scouting "Medal of Merit" badge had a swastika

The swastika (卐 or 卍) is an ancient religious and cultural symbol, predominantly in various Eurasian, as well as some African and American cultures, now also widely recognized for its appropriation by the Nazi Party and by neo-Nazis. I ...

symbol on them. This was undoubtedly influenced by the use by Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British Raj, British India, which inspired much o ...

of the swastika on the jacket of his published books, including ''Kim

Kim or KIM may refer to:

Names

* Kim (given name)

* Kim (surname)

** Kim (Korean surname)

*** Kim family (disambiguation), several dynasties

**** Kim family (North Korea), the rulers of North Korea since Kim Il-sung in 1948

** Kim, Vietnamese ...

'', which was used by Baden-Powell as a basis for the Wolf Cub branch of the Scouting Movement. The swastika had been a symbol for luck in India long before being adopted by the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

in 1920, and when Nazi use of the swastika became more widespread, the Scouts stopped using it.

Nazi Germany banned Scouting, a competitor to the Hitler Youth

The Hitler Youth (german: Hitlerjugend , often abbreviated as HJ, ) was the youth organisation of the Nazi Party in Germany. Its origins date back to 1922 and it received the name ("Hitler Youth, League of German Worker Youth") in July 1926. ...

, in June 1934, seeing it as "a haven for young men opposed to the new State". Based on the regime's view of Scouting as a dangerous espionage organisation, Baden-Powell's name was included in " The Black Book", a 1940 list of people to be detained following the planned conquest of the United Kingdom. A drawing by Baden-Powell depicts Scouts assisting refugees fleeing from the Nazis and Hitler. Tim Jeal, author of the biography '' Baden-Powell'', gives his opinion that "Baden-Powell's distrust of communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society ...

led to his implicit support, through naïveté, of fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and th ...

", an opinion based on two of B-P's diary entries. Baden-Powell met Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

on 2 March 1933, and in his diary described him as "small, stout, human and genial. Told me about Balilla, and workmen's outdoor recreations which he imposed though 'moral force'". On 17 October 1939, Baden-Powell wrote in his diary: "Lay up all day. Read ''Mein Kampf

(; ''My Struggle'' or ''My Battle'') is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for G ...

''. A wonderful book, with good ideas on education, health, propaganda, organisation etc. – and ideals which Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

does not practice himself."

At the 5th World Scout Jamboree

The 5th World Scout Jamboree (Dutch language, Dutch: ''5e Wereldjamboree'') was the World Scout Jamboree where 81-year-old Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, Robert Baden-Powell gave his farewell.

Organizational details

The Jamboree (S ...

in 1937, Baden-Powell gave his farewell to Scouting, and retired from public Scouting life. 22 February, the joint birthday of Robert and Olave Baden-Powell, continues to be marked as Founder's Day by Scouts and World Thinking Day by Guides to remember and celebrate the work of the Chief Scout A Chief Scout is the principal or head scout for an organization such as the military, colonial administration or expedition or a talent scout in performing, entertainment or creative arts, particularly sport. In sport, a Chief Scout can be the prin ...

and Chief Guide of the World.

In his final letter to the Scouts, Baden-Powell wrote:

I have had a most happy life and I want each one of you to have a happy life too. I believe that God put us in this jolly world to be happy and enjoy life. Happiness does not come from being rich, nor merely being successful in your career, nor by self-indulgence. One step towards happiness is to make yourself healthy and strong while you are a boy, so that you can be useful and so you can enjoy life when you are a man. Nature study will show you how full of beautiful and wonderful things God has made the world for you to enjoy. Be contented with what you have got and make the best of it. Look on the bright side of things instead of the gloomy one. But the real way to get happiness is by giving out happiness to other people. Try and leave this world a little better than you found it and when your turn comes to die, you can die happy in feeling that at any rate you have not wasted your time but have done your best. "Be prepared" in this way, to live happy and to die happy – stick to your Scout Promise always – even after you have ceased to be a boy – and God help you to do it.Baden-Powell died on 8 January 1941: his grave is in St Peter's Cemetery in Nyeri, Kenya. His gravestone bears a circle with a dot in the centre "ʘ", which is the trail sign for "Going home", or "I have gone home". His wife Olave moved back to England in 1942, although after she died in 1977, her ashes were taken to Kenya by her grandson

Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, h ...

and interred beside her husband. In 2001 the Kenyan government declared Baden-Powell's grave a National Monument.

Writings and publications

Baden-Powell published books and other texts during his years of military service both to finance his life and to generally educate his men.

* 1884: ''Reconnaissance and Scouting''

* 1885: ''Cavalry Instruction''

* 1889: ''Pigsticking or Hoghunting''

* 1896: ''The Downfall of Prempeh''

* 1897: ''The Matabele Campaign''

* 1899: ''Aids to Scouting for N.-C.Os and Men''

* 1900: ''Sport in War''

* 1901: ''Notes and Instructions for the South African Constabulary''

* 1907: ''Sketches in Mafeking and East Africa''

* 1910: ''British Discipline'', Essay 32 of Essays on Duty and Discipline

* 1914: ''Quick Training for War''

Baden-Powell was regarded as an excellent storyteller. During his whole life he told "ripping yarns" to audiences. After having published ''Scouting for Boys'', Baden-Powell kept on writing more handbooks and educative materials for all Scouts, as well as directives for Scout Leaders. In his later years, he also wrote about the Scout movement and his ideas for its future. He spent most of the last two years of his life in Africa, and many of his later books had African themes.

* 1908: ''

Baden-Powell published books and other texts during his years of military service both to finance his life and to generally educate his men.

* 1884: ''Reconnaissance and Scouting''

* 1885: ''Cavalry Instruction''

* 1889: ''Pigsticking or Hoghunting''

* 1896: ''The Downfall of Prempeh''

* 1897: ''The Matabele Campaign''

* 1899: ''Aids to Scouting for N.-C.Os and Men''

* 1900: ''Sport in War''

* 1901: ''Notes and Instructions for the South African Constabulary''

* 1907: ''Sketches in Mafeking and East Africa''

* 1910: ''British Discipline'', Essay 32 of Essays on Duty and Discipline

* 1914: ''Quick Training for War''

Baden-Powell was regarded as an excellent storyteller. During his whole life he told "ripping yarns" to audiences. After having published ''Scouting for Boys'', Baden-Powell kept on writing more handbooks and educative materials for all Scouts, as well as directives for Scout Leaders. In his later years, he also wrote about the Scout movement and his ideas for its future. He spent most of the last two years of his life in Africa, and many of his later books had African themes.

* 1908: ''Scouting for Boys

''Scouting for Boys: A handbook for instruction in good citizenship'' is a book on Boy Scout training, published in various editions since 1908. Early editions were written and illustrated by Robert Baden-Powell with later editions being extens ...

''

* 1909: The Scout Library No.4 ''Scouting Games''

* 1909: ''Yarns for Boy Scouts''

* 1912: '' The Handbook for the Girl Guides or How Girls Can Help to Build Up the Empire'' (co-authored with Agnes Baden-Powell)

* 1913: ''Boy Scouts Beyond The Sea: My World Tour''

* 1915: ''Indian Memories'' (American title ''Memories of India'')

* 1915: ''My Adventures as a Spy''

* 1916: ''Young Knights of the Empire: Their Code, and Further Scout Yarns''

* 1916: '' The Wolf Cub's Handbook''

* 1918: ''Girl Guiding''

* 1919: ''Aids To Scoutmastership''

* 1921: ''What Scouts Can Do: More Yarns''

* 1921: ''An Old Wolf's Favourites''

* 1922: ''Rovering to Success

''Rovering to Success'' is a life-guide book for Rovers written and illustrated by Robert Baden-Powell and published in two editions from June 1922. It has a theme of paddling a canoe through life. The original edition and printings of second editi ...

''

* 1927: ''Life's Snags and How to Meet Them''

* 1927: ''South African Tour 1926-7''

* 1929: ''Scouting and Youth Movements''

* est 1929: ''Last Message to Scouts

A last is a mechanical form shaped like a human foot. It is used by shoemakers and cordwainers in the manufacture and repair of shoes. Lasts typically come in pairs and have been made from various materials, including hardwoods, cast iron, and ...

''

* 1932: ''He-who-sees-in-the-dark; the Boys' Story of Frederick Burnham, the American Scout''

* 1933: ''Lessons From the Varsity of Life''

* 1934: ''Adventures and Accidents''

* 1935: ''Scouting Round the World''

* 1936: ''Adventuring to Manhood''

* 1937: ''African Adventures''

* 1938: ''Birds and Beasts of Africa''

* 1939: ''Paddle Your Own Canoe''

* 1940: ''More Sketches Of Kenya''

Most of his books (the American editions) are available online.

Compilations and excerpts comprised:

*

*

*

*

Baden-Powell also contributed to various other books, either with an introduction or foreword, or being quoted by the author,

* 1905: ''Ambidexterity'' by John Jackson

* 1930: ''Fifty years against the stream: The story of a school in Kashmir, 1880–1930'' by E.D. Tyndale-Biscoe about the Tyndale Biscoe School

Tyndale Biscoe School is a school in the Sheikh Bagh neighbourhood, in the Lal Chowk area of Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, India. The school was founded in 1880 CE and is one of the oldest schools in Jammu and Kashmir, the oldest being S.P sc ...

A comprehensive bibliography of his original works has been published by Biblioteca Frati Minori Cappuccini.

Art

Baden-Powell's father often sketched caricatures of those present at meetings, while his maternal grandmother was also artistic. Baden-Powell painted or sketched almost every day of his life. Most of his works have a humorous or informative character. His books are scattered with his pen-and-ink sketches, frequently whimsical. He did a large unknown number of pen-and-ink sketches; he always travelled with a sketchpad that he used frequently for pencil sketches and "cartoons" for later water-colour paintings. He also created a few sculptures. There is no catalogue of his works, many of which appear in his books, and twelve paintings hang in the British Scout Headquarters atGilwell Park

Gilwell Park is a camp site and activity centre in East London located in the Sewardstonebury area of Waltham Abbey, within Epping Forest, near the border with Chingford. The site is owned by The Scout Association, is used by Scouting and Gu ...

. There was an exhibition of his work at the Willmer House Museum, Farnham, Surrey, from 11 April – 12 May 1967; a text-only catalogue was produced.

Personal life

In January 1912, Baden-Powell was en route to New York on a Scouting World Tour, on the ocean liner , when he met Olave St Clair Soames. She was 23, while he was 55; they shared the same birthday, 22 February. They became engaged in September of the same year, causing a media sensation due to Baden-Powell's fame. To avoid press intrusion, they married in private on 30 October 1912, at St Peter's Church in

In January 1912, Baden-Powell was en route to New York on a Scouting World Tour, on the ocean liner , when he met Olave St Clair Soames. She was 23, while he was 55; they shared the same birthday, 22 February. They became engaged in September of the same year, causing a media sensation due to Baden-Powell's fame. To avoid press intrusion, they married in private on 30 October 1912, at St Peter's Church in Parkstone

Parkstone is an area of Poole, Dorset. It is divided into 'Lower' and 'Upper' Parkstone. Upper Parkstone - "Up-on-'ill" as it used to be known in local parlance - is so-called because it is largely on higher ground slightly to the north of th ...

. 100,000 Scouts had each donated a penny (1d) to buy Baden-Powell a wedding gift, a 20 h.p. Standard motor-car (not the Rolls-Royce they were presented with in 1929). There is a display about their marriage inside St Peter's Church, Parkstone.

The couple lived in Pax Hill near Bentley, Hampshire, from about 1919 until 1939. The Bentley house was a gift from her father. After they married, Baden-Powell began to suffer persistent headaches which were considered by his doctor to be

The couple lived in Pax Hill near Bentley, Hampshire, from about 1919 until 1939. The Bentley house was a gift from her father. After they married, Baden-Powell began to suffer persistent headaches which were considered by his doctor to be psychosomatic

A somatic symptom disorder, formerly known as a somatoform disorder,(2013) dsm5.org. Retrieved April 8, 2014. is any mental disorder that manifests as physical symptoms that suggest illness or injury, but cannot be explained fully by a general ...

, and which were treated with dream analysis.

In 1939, they moved to a cottage he had commissioned in Nyeri

Nyeri is a town situated in the Central Highlands of Kenya. It is the county headquarters of Nyeri County. The town was the central administrative headquarters of the country's former Central Province. Following the dissolution of the former pr ...

, Kenya, near Mount Kenya

Mount Kenya ( Kikuyu: ''Kĩrĩnyaga'', Kamba, ''Ki Nyaa'') is the highest mountain in Kenya and the second-highest in Africa, after Kilimanjaro. The highest peaks of the mountain are Batian (), Nelion () and Point Lenana (). Mount Kenya is loc ...

, where he had previously been to recuperate. The small one-room house, which he named ''Paxtu'', was located on the grounds of the Outspan Hotel

The Outspan Hotel is in Nyeri, Kenya. It was built up from an old farm by Eric Sherbrooke Walker in the 1920s.

Walker had purchased of Crown Land in Nyeri and in 1928, opened the Outspan Hotel, overlooking the gorge of a river in the Aberdare ...

, owned by Eric Sherbrooke Walker, Baden-Powell's first private secretary and one of the first Scout inspectors. Walker also owned the Treetops Hotel, approximately 10 miles (17 km) out in the Aberdare Mountains, often visited by Baden-Powell and people of the Happy Valley set

The Happy Valley set was a group of hedonistic, largely British and Anglo-Irish aristocrats and adventurers who settled in the "Happy Valley" region of the Wanjohi Valley, near the Aberdare mountain range, in colonial Kenya and Uganda betw ...

. The Paxtu cottage is integrated into the Outspan Hotel buildings and serves as a small Scouting museum.

Baden-Powell and his wife were parents of Arthur Robert Peter (1913–1962), who succeeded his father in the barony; Heather Grace (1915–1986), who married John Hall King (1913–2004) and had two sons, the elder of whom, Michael, was killed in the sinking of in 1966; and Betty St Clair (1917–2004). When Olave's sister Auriol Davidson (née Soames) died in 1919, Olave and Robert took her three daughters into their family and brought them up as their own children.

Three of Baden-Powell's many biographers comment on his sexuality; the first two (in 1979 and 1986) focused on his relationship with his close friend

Baden-Powell and his wife were parents of Arthur Robert Peter (1913–1962), who succeeded his father in the barony; Heather Grace (1915–1986), who married John Hall King (1913–2004) and had two sons, the elder of whom, Michael, was killed in the sinking of in 1966; and Betty St Clair (1917–2004). When Olave's sister Auriol Davidson (née Soames) died in 1919, Olave and Robert took her three daughters into their family and brought them up as their own children.

Three of Baden-Powell's many biographers comment on his sexuality; the first two (in 1979 and 1986) focused on his relationship with his close friend Kenneth McLaren

Kenneth McLaren DSO (sometimes given as "MacLaren"),"Captain Kenneth MacLaren, 13th Hussars, who it will be remembered was for a time adjutant of the regiment, was in July 1899 acting as A.D.C. to General Sir Baker Russell. He was then ordered to ...

. Tim Jeal's later (1989) biography discusses the relationship and finds no evidence that this friendship was of an erotic nature. Jeal then examines Baden-Powell's views on women, his appreciation of the male form, his military relationships, and his marriage, concluding that, in his personal opinion, Baden-Powell was a repressed homosexual. Jeal's arguments and conclusion are dismissed by Procter and Block (2009) as "amateur psychoanalysis", for which there is no physical evidence.

Commissions and promotions

* Commissioned

* Commissioned sub-lieutenant

Sub-lieutenant is usually a junior officer rank, used in armies, navies and air forces.

In most armies, sub-lieutenant is the lowest officer rank. However, in Brazil, it is the highest non-commissioned rank, and in Spain, it is the second hig ...

, 13th Hussars, 11 September 1876 (retroactively granted the rank of lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

from the same date on 17 September 1878)

* Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

, 13th Hussars, 16 May 1883

** Brevet major, British Army, 1890

* Major, 13th Hussars, 1 July 1892

** Brevet lieutenant colonel, British Army, 25 March 1896

* Lieutenant colonel, 13th Hussars, 25 April 1897

** Brevet colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge ...

, British Army, 8 May 1897

** Commanding officer, 5th Dragoon Guards, 1897

* Major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

, 23 May 1900

** Inspector General of Cavalry, British Army

* Lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

, 10 June 1907

Recognition

In 1937 Baden-Powell was appointed to the

In 1937 Baden-Powell was appointed to the Order of Merit

The Order of Merit (french: link=no, Ordre du Mérite) is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by ...

, one of the most exclusive awards in the British honours system

In the United Kingdom and the British Overseas Territories, personal bravery, achievement, or service are rewarded with honours. The honours system consists of three types of award:

*Honours are used to recognise merit in terms of achievement a ...

, and he was also awarded 28 decorations by foreign states, including the Grand Officer of the Portuguese Order of Christ, the Grand Commander of the Greek Order of the Redeemer

The Order of the Redeemer ( el, Τάγμα του Σωτήρος, translit=Tágma tou Sotíros), also known as the Order of the Saviour, is an order of merit of Greece. The Order of the Redeemer is the oldest and highest decoration awarded by the ...

(1920), the Commander of the French Légion d'honneur

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon B ...

(1925), the First Class of the Hungarian Order of Merit (1929), the Grand Cross of the Order of the Dannebrog

The Order of the Dannebrog ( da, Dannebrogordenen) is a Danish order of chivalry instituted in 1671 by Christian V. Until 1808, membership in the order was limited to fifty members of noble or royal rank, who formed a single class known ...

of Denmark, the Grand Cross of the Order of the White Lion

The Order of the White Lion ( cs, Řád Bílého lva) is the highest order of the Czech Republic. It continues a Czechoslovak order of the same name created in 1922 as an award for foreigners (Czechoslovakia had no civilian decoration for its ...

, the Grand Cross of the Order of the Phoenix, and the Order of Polonia Restituta

, image=Polonia Restituta - Commander's Cross pre-1939 w rib.jpg

, image_size=200px

, caption=Commander's Cross of Polonia Restituta

, presenter = the President of Poland

, country =

, type=Five classes

, eligibility=All

, awar ...

.

The Silver Wolf Award was originally worn by Robert Baden-Powell. The Bronze Wolf Award

The Bronze Wolf Award is bestowed by the World Scout Committee (WSC) to acknowledge "outstanding service by an individual to the World Scout Movement". It is the highest honor that can be given a volunteer Scout leader in the world and it is the ...

, the only distinction of the World Organization of the Scout Movement

The World Organization of the Scout Movement (WOSM ) is the largest international Scouting organization. WOSM has 173 members. These members are recognized national Scout organizations, which collectively have around 43 million participants. WOSM ...

, awarded by the World Scout Committee

The World Organization of the Scout Movement (WOSM ) is the largest international Scouting organization. WOSM has 173 members. These members are recognized national Scout organizations, which collectively have around 43 million participants. WOSM ...

for exceptional services to world Scouting, was first awarded to Baden-Powell by a unanimous decision of the then ''International Committee'' on the day of the institution of the Bronze Wolf in Stockholm in 1935. He was also the first recipient of the Silver Buffalo Award

The Silver Buffalo Award is the national-level distinguished service award of the Boy Scouts of America. It is presented for noteworthy and extraordinary service to youth on a national basis, either as part of, or independent of the Scouting pro ...

in 1926, the highest award conferred by the Boy Scouts of America

The Boy Scouts of America (BSA, colloquially the Boy Scouts) is one of the largest scouting organizations and one of the largest List of youth organizations, youth organizations in the United States, with about 1.2 million youth partici ...

.

In 1927, at the Swedish National Jamboree he was awarded by the '' Österreichischer Pfadfinderbund'' with the "''Großes Dankabzeichen des ÖPB''. In 1931 Baden-Powell received the highest award of the First Austrian Republic

The First Austrian Republic (german: Erste Österreichische Republik), officially the Republic of Austria, was created after the signing of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye on 10 September 1919—the settlement after the end of World War I w ...

(''Großes Ehrenzeichen der Republik am Bande'') out of the hands of President Wilhelm Miklas

Wilhelm Miklas (15 October 187220 March 1956) was an Austrian politician who served as President of Austria from 1928 until the ''Anschluss'' to Nazi Germany in 1938.

Early life

Born as the son of a post official in Krems, in the Cisleithani ...

. Baden-Powell was also one of the first and few recipients of the ''Goldene Gemse'', the highest award conferred by the Österreichischer Pfadfinderbund.

In 1931, Major

In 1931, Major Frederick Russell Burnham

Frederick Russell Burnham DSO (May 11, 1861 – September 1, 1947) was an American scout and world-traveling adventurer. He is known for his service to the British South Africa Company and to the British Army in colonial Africa, and for teac ...

dedicated Mount Baden-Powell in California to his old Scouting friend from forty years before. Today, their friendship is honoured in perpetuity with the dedication of the adjoining peak, Mount Burnham

Mount Burnham is one of the highest peaks in the San Gabriel Mountains. It is in the Sheep Mountain Wilderness. It is named for Frederick Russell Burnham the famous American military scout who taught Scoutcraft (then known as ''woodcraft'') to R ...

.

Baden-Powell was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

on numerous occasions, including 10 separate nominations in 1928. He was awarded the Wateler Peace Prize

The Wateler Peace Prize is awarded annually by the Dutch Carnegie Foundation and is named for J.G.D. Wateler who, upon his death on 22 July 1927 "bequeathed his estate to the Dutch State, under the proviso that the annual revenue accruing from it ...

in 1937. In 2002, Baden-Powell was named 13th in the BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

's list of the 100 Greatest Britons

''100 Greatest Britons'' is a television series that was broadcast by the BBC in 2002. It was based on a television poll conducted to determine who the British people at that time considered the greatest Britons in history. The series included ...

following a UK-wide vote. As part of the Scouting 2007 Centenary, Nepal renamed Urkema Peak to Baden-Powell Peak.

In June 2020, following the George Floyd protests

The George Floyd protests were a series of protests and civil unrest against police brutality and racism that began in Minneapolis on May 26, 2020, and largely took place during 2020. The civil unrest and protests began as part of internat ...

in Britain and the removal of the statue of Edward Colston

The statue of Edward Colston is a bronze statue of Bristol-born merchant and trans-Atlantic slave trader, Edward Colston (1636–1721). It was created in 1895 by the Irish sculptor John Cassidy and was formerly erected on a plinth of Portland ...

in Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city i ...

, the Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Council

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole Council is a unitary local authority for the district of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole in England that came into being on 1 April 2019. It was created from the areas that were previously administered ...

(BCP Council) announced that a statue of Baden-Powell on Poole Quay would be removed temporarily for its protection, amid fears for its safety. Police believed it was on a list of monuments to be destroyed or removed, and that it was a target for protestors due to perceptions that Baden-Powell had held homophobic and racist views. The statue had been installed by BCP Council in 2008.

Following opposition to its removal, including from local residents, and past and present scouts, some of whom camped nearby to ensure it stayed in place, BCP Council had the statue boarded up instead. Mark Howell, deputy leader of BCP Council was quoted as saying, "It is our intention that the boarding is removed at the earliest, safe opportunity."

Honours – United Kingdom

Honours – Other countries

Arms

Cultural depictions

*ActorRon Moody

Ron Moody (born Ronald Moodnick; 8 January 1924 – 11 June 2015) was an English actor, composer, singer and writer. He was best known for his portrayal of Fagin in '' Oliver!'' (1968) and its 1983 Broadway revival. Moody earned a Golden Glob ...

portrays Baden-Powell in the 1972-1973 miniseries '' The Edwardians''.

See also

*Baden-Powell's unilens

The unilens monocular is a simple refracting telescope for field use, designed by Robert Baden-Powell. Consisting of only one lens, it is the simplest of all telescopes, and while occupying very little space can still magnify a distant image up to ...

* Scouting memorials

Since the birth and expansion of the Scout movement in the first decade of the 20th century, many Scouting memorials, monuments and gravesites have been erected throughout the world.

Africa

Kenya

* Baden-Powell grave – Wajee Nature Park, Nye ...

Notes

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * *External links