Bacteria Described In 1894 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one

The word ''bacteria'' is the plural of the

The word ''bacteria'' is the plural of the

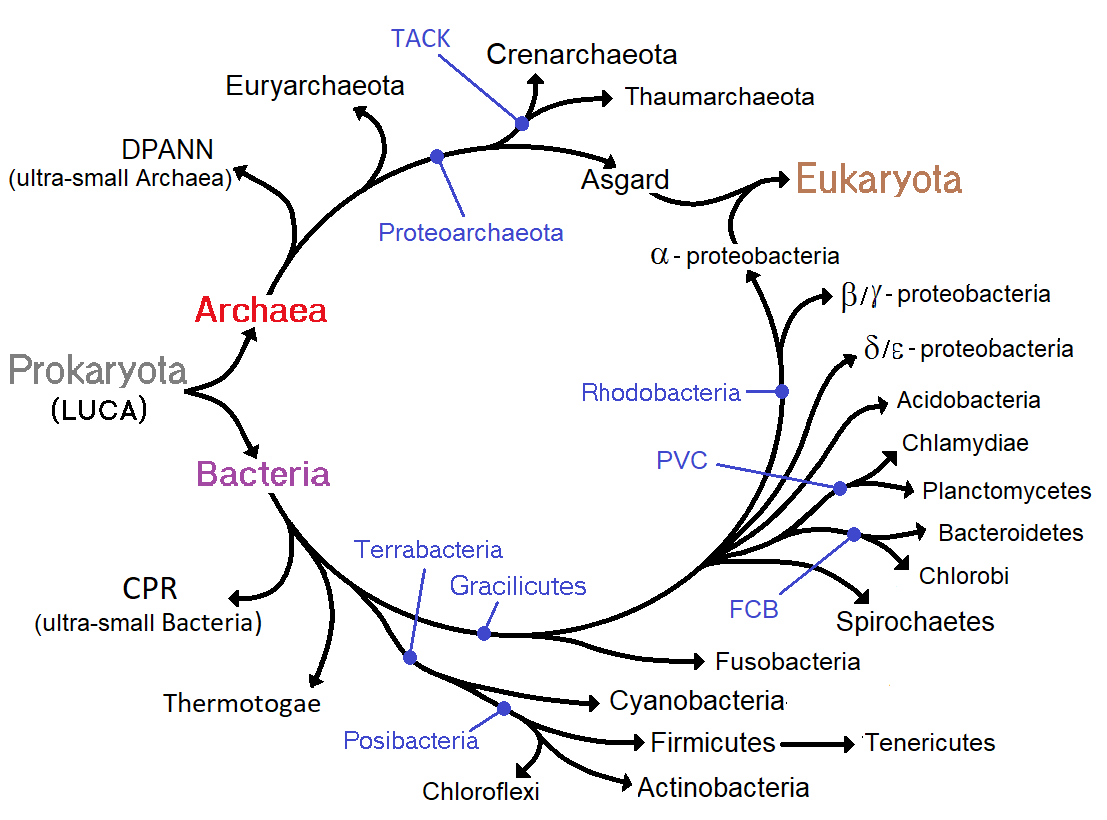

The ancestors of bacteria were unicellular microorganisms that were the first forms of life to appear on Earth, about 4 billion years ago. For about 3 billion years, most organisms were microscopic, and bacteria and archaea were the dominant forms of life. Although bacterial

The ancestors of bacteria were unicellular microorganisms that were the first forms of life to appear on Earth, about 4 billion years ago. For about 3 billion years, most organisms were microscopic, and bacteria and archaea were the dominant forms of life. Although bacterial

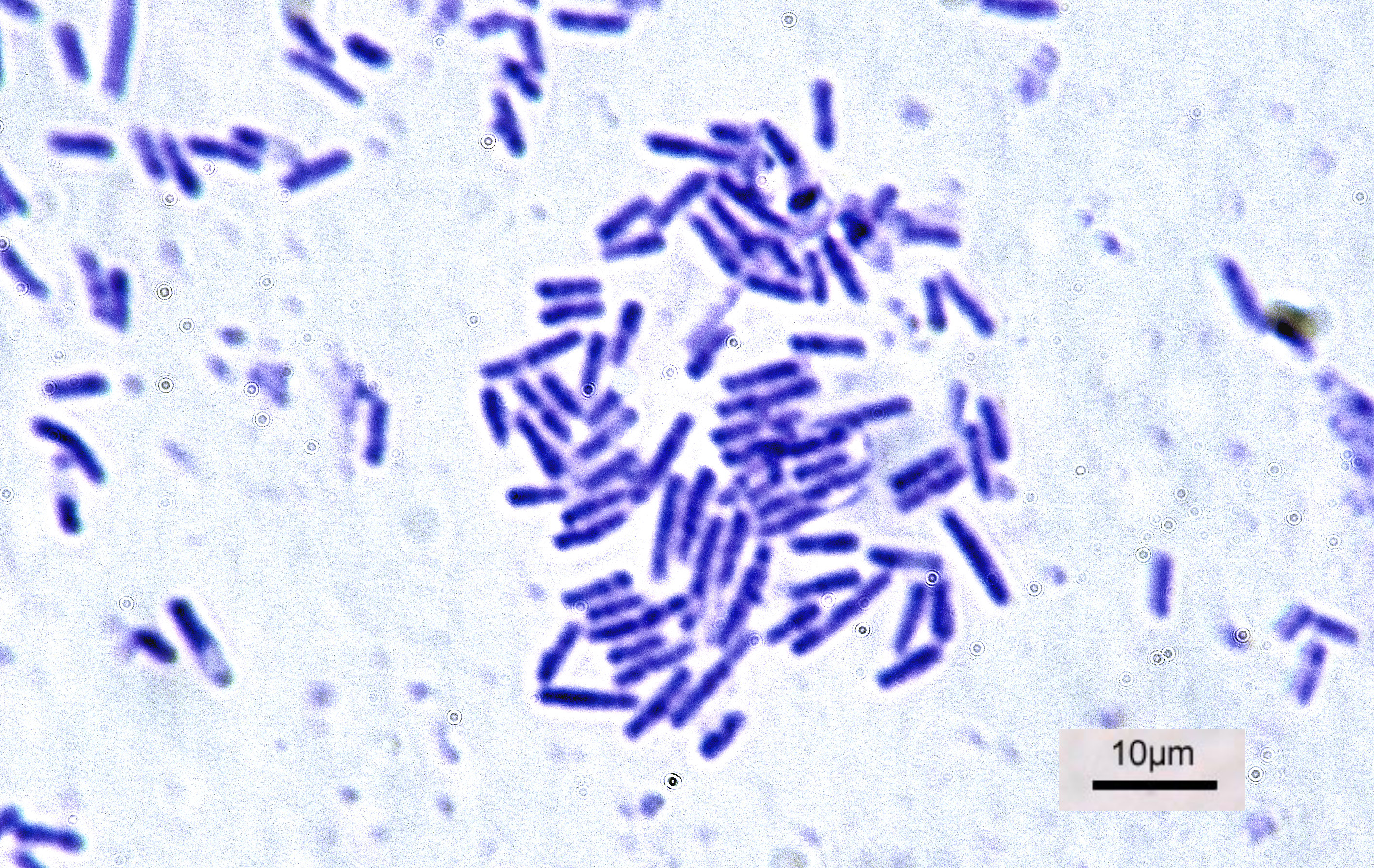

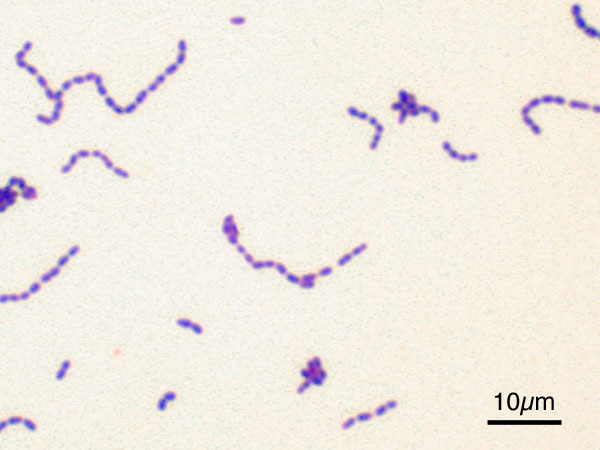

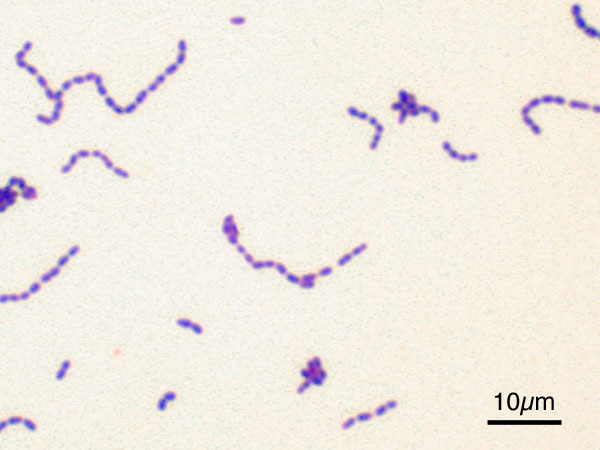

Size. Bacteria display a wide diversity of shapes and sizes. Bacterial cells are about one-tenth the size of eukaryotic cells and are typically 0.5–5.0

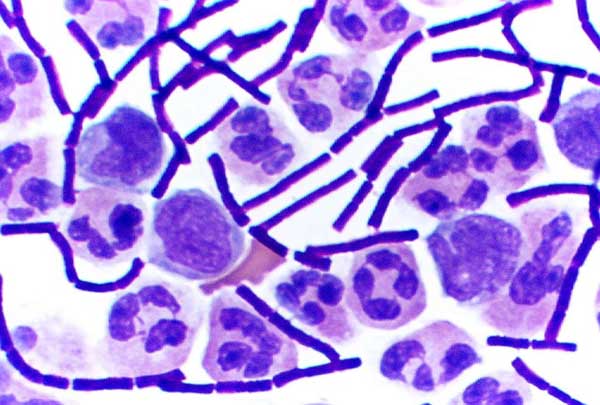

Size. Bacteria display a wide diversity of shapes and sizes. Bacterial cells are about one-tenth the size of eukaryotic cells and are typically 0.5–5.0  Multicellularity. Most bacterial species exist as single cells; others associate in characteristic patterns: ''

Multicellularity. Most bacterial species exist as single cells; others associate in characteristic patterns: ''

Bacteria do not have a membrane-bound nucleus, and their

Bacteria do not have a membrane-bound nucleus, and their

Some

Some

Unlike in multicellular organisms, increases in cell size (cell growth) and reproduction by

Unlike in multicellular organisms, increases in cell size (cell growth) and reproduction by

Most bacteria have a single circular

Most bacteria have a single circular

Many bacteria are Motility, motile (able to move themselves) and do so using a variety of mechanisms. The best studied of these are Flagellum, flagella, long filaments that are turned by a motor at the base to generate propeller-like movement. The bacterial flagellum is made of about 20 proteins, with approximately another 30 proteins required for its regulation and assembly. The flagellum is a rotating structure driven by a reversible motor at the base that uses the

Many bacteria are Motility, motile (able to move themselves) and do so using a variety of mechanisms. The best studied of these are Flagellum, flagella, long filaments that are turned by a motor at the base to generate propeller-like movement. The bacterial flagellum is made of about 20 proteins, with approximately another 30 proteins required for its regulation and assembly. The flagellum is a rotating structure driven by a reversible motor at the base that uses the  Bacteria can use flagella in different ways to generate different kinds of movement. Many bacteria (such as ''Escherichia coli, E. coli'') have two distinct modes of movement: forward movement (swimming) and tumbling. The tumbling allows them to reorient and makes their movement a three-dimensional random walk. Bacterial species differ in the number and arrangement of flagella on their surface; some have a single flagellum (''Flagellum#Flagellar arrangement schemes, monotrichous''), a flagellum at each end (''Flagellum#Flagellar arrangement schemes, amphitrichous''), clusters of flagella at the poles of the cell (''Flagellum#Flagellar arrangement schemes, lophotrichous''), while others have flagella distributed over the entire surface of the cell (''Flagellum#Flagellar arrangement schemes, peritrichous''). The flagella of a unique group of bacteria, the spirochaetes, are found between two membranes in the periplasmic space. They have a distinctive helix, helical body that twists about as it moves.

Two other types of bacterial motion are called twitching motility that relies on a structure called the pilus#Type IV pili, type IV pilus, and Bacterial gliding, gliding motility, that uses other mechanisms. In twitching motility, the rod-like pilus extends out from the cell, binds some substrate, and then retracts, pulling the cell forward.

Motile bacteria are attracted or repelled by certain stimulus (physiology), stimuli in behaviours called ''taxis, taxes'': these include chemotaxis, phototaxis, taxis, energy taxis, and magnetotaxis. In one peculiar group, the myxobacteria, individual bacteria move together to form waves of cells that then differentiate to form fruiting bodies containing spores. The myxobacteria move only when on solid surfaces, unlike ''E. coli'', which is motile in liquid or solid media.

Several ''Listeria'' and ''Shigella'' species move inside host cells by usurping the

Bacteria can use flagella in different ways to generate different kinds of movement. Many bacteria (such as ''Escherichia coli, E. coli'') have two distinct modes of movement: forward movement (swimming) and tumbling. The tumbling allows them to reorient and makes their movement a three-dimensional random walk. Bacterial species differ in the number and arrangement of flagella on their surface; some have a single flagellum (''Flagellum#Flagellar arrangement schemes, monotrichous''), a flagellum at each end (''Flagellum#Flagellar arrangement schemes, amphitrichous''), clusters of flagella at the poles of the cell (''Flagellum#Flagellar arrangement schemes, lophotrichous''), while others have flagella distributed over the entire surface of the cell (''Flagellum#Flagellar arrangement schemes, peritrichous''). The flagella of a unique group of bacteria, the spirochaetes, are found between two membranes in the periplasmic space. They have a distinctive helix, helical body that twists about as it moves.

Two other types of bacterial motion are called twitching motility that relies on a structure called the pilus#Type IV pili, type IV pilus, and Bacterial gliding, gliding motility, that uses other mechanisms. In twitching motility, the rod-like pilus extends out from the cell, binds some substrate, and then retracts, pulling the cell forward.

Motile bacteria are attracted or repelled by certain stimulus (physiology), stimuli in behaviours called ''taxis, taxes'': these include chemotaxis, phototaxis, taxis, energy taxis, and magnetotaxis. In one peculiar group, the myxobacteria, individual bacteria move together to form waves of cells that then differentiate to form fruiting bodies containing spores. The myxobacteria move only when on solid surfaces, unlike ''E. coli'', which is motile in liquid or solid media.

Several ''Listeria'' and ''Shigella'' species move inside host cells by usurping the

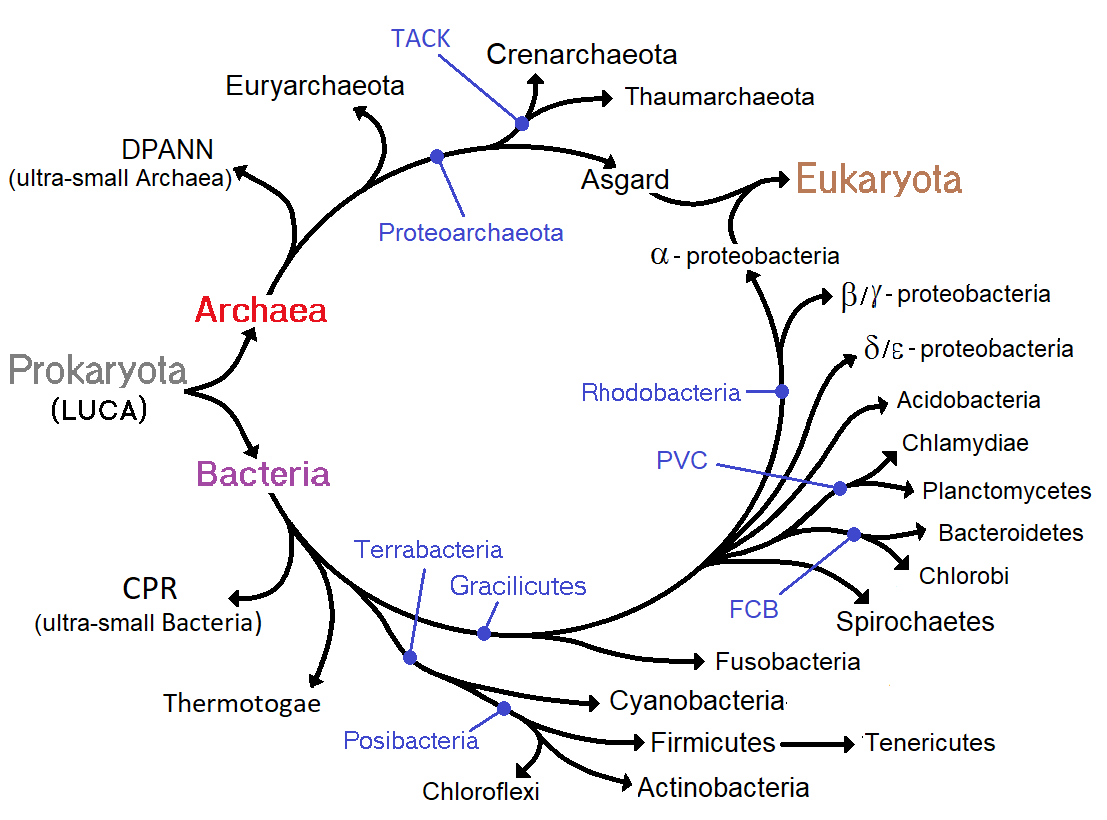

Scientific classification, Classification seeks to describe the diversity of bacterial species by naming and grouping organisms based on similarities. Bacteria can be classified on the basis of cell structure, Cell metabolism, cellular metabolism or on differences in cell components, such as DNA, fatty acids, pigments,

Scientific classification, Classification seeks to describe the diversity of bacterial species by naming and grouping organisms based on similarities. Bacteria can be classified on the basis of cell structure, Cell metabolism, cellular metabolism or on differences in cell components, such as DNA, fatty acids, pigments,

Despite their apparent simplicity, bacteria can form complex associations with other organisms. These symbiosis, symbiotic associations can be divided into parasitism, Mutualism (biology), mutualism and commensalism.

Despite their apparent simplicity, bacteria can form complex associations with other organisms. These symbiosis, symbiotic associations can be divided into parasitism, Mutualism (biology), mutualism and commensalism.

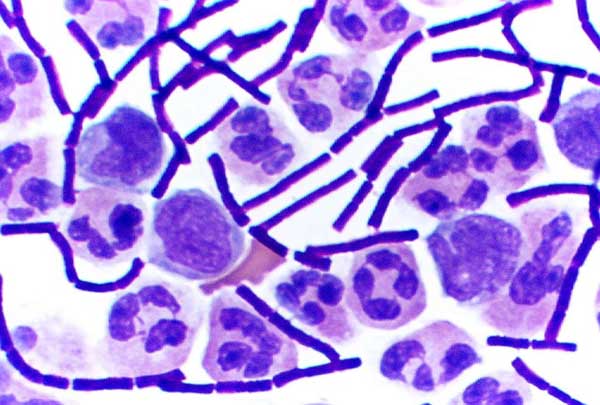

The body is continually exposed to many species of bacteria, including beneficial commensals, which grow on the skin and mucous membranes, and saprophytes, which grow mainly in the soil and in decomposition, decaying matter. The blood and tissue fluids contain nutrients sufficient to sustain the growth of many bacteria. The body has defence mechanisms that enable it to resist microbial invasion of its tissues and give it a natural immune system, immunity or innate immunity, innate resistance against many microorganisms. Unlike some

The body is continually exposed to many species of bacteria, including beneficial commensals, which grow on the skin and mucous membranes, and saprophytes, which grow mainly in the soil and in decomposition, decaying matter. The blood and tissue fluids contain nutrients sufficient to sustain the growth of many bacteria. The body has defence mechanisms that enable it to resist microbial invasion of its tissues and give it a natural immune system, immunity or innate immunity, innate resistance against many microorganisms. Unlike some  Each species of pathogen has a characteristic spectrum of interactions with its human host (biology), hosts. Some organisms, such as ''Staphylococcus'' or ''Streptococcus'', can cause skin infections, pneumonia, meningitis and sepsis, a systemic Inflammation, inflammatory response producing shock (circulatory), shock, massive vasodilator, vasodilation and death. Yet these organisms are also part of the normal human flora and usually exist on the skin or in the nose without causing any disease at all. Other organisms invariably cause disease in humans, such as ''Rickettsia'', which are obligate intracellular parasites able to grow and reproduce only within the cells of other organisms. One species of ''Rickettsia'' causes typhus, while another causes Rocky Mountain spotted fever. ''Chlamydia (bacterium), Chlamydia'', another phylum of obligate intracellular parasites, contains species that can cause pneumonia or urinary tract infection and may be involved in coronary heart disease. Some species, such as ''

Each species of pathogen has a characteristic spectrum of interactions with its human host (biology), hosts. Some organisms, such as ''Staphylococcus'' or ''Streptococcus'', can cause skin infections, pneumonia, meningitis and sepsis, a systemic Inflammation, inflammatory response producing shock (circulatory), shock, massive vasodilator, vasodilation and death. Yet these organisms are also part of the normal human flora and usually exist on the skin or in the nose without causing any disease at all. Other organisms invariably cause disease in humans, such as ''Rickettsia'', which are obligate intracellular parasites able to grow and reproduce only within the cells of other organisms. One species of ''Rickettsia'' causes typhus, while another causes Rocky Mountain spotted fever. ''Chlamydia (bacterium), Chlamydia'', another phylum of obligate intracellular parasites, contains species that can cause pneumonia or urinary tract infection and may be involved in coronary heart disease. Some species, such as ''

On-line text book on bacteriology (2015)

{{Authority control Bacteria, Bacteriology Domains (biology)

biological cell

The cell is the basic structural and functional unit of life forms. Every cell consists of a cytoplasm enclosed within a membrane, and contains many biomolecules such as proteins, DNA and RNA, as well as many small molecules of nutrients and ...

. They constitute a large domain

Domain may refer to:

Mathematics

*Domain of a function, the set of input values for which the (total) function is defined

**Domain of definition of a partial function

**Natural domain of a partial function

**Domain of holomorphy of a function

* Do ...

of prokaryotic

A prokaryote () is a Unicellular organism, single-celled organism that lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek language, Greek wikt:πρό#Ancient Greek, πρό (, 'before') a ...

microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

s. Typically a few micrometre

The micrometre ( international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: μm) or micrometer (American spelling), also commonly known as a micron, is a unit of length in the International System of Unit ...

s in length, bacteria were among the first life forms to appear on Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

, and are present in most of its habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

s. Bacteria inhabit soil, water, acidic hot springs, radioactive waste

Radioactive waste is a type of hazardous waste that contains radioactive material. Radioactive waste is a result of many activities, including nuclear medicine, nuclear research, nuclear power generation, rare-earth mining, and nuclear weapons r ...

, and the deep biosphere

The deep biosphere is the part of the biosphere that resides below the first few meters of the surface. It extends down at least 5 kilometers below the continental surface and 10.5 kilometers below the sea surface, at temperatures that ...

of Earth's crust

Earth's crust is Earth's thin outer shell of rock, referring to less than 1% of Earth's radius and volume. It is the top component of the lithosphere, a division of Earth's layers that includes the crust and the upper part of the mantle. The ...

. Bacteria are vital in many stages of the nutrient cycle

A nutrient cycle (or ecological recycling) is the movement and exchange of inorganic and organic matter back into the production of matter. Energy flow is a unidirectional and noncyclic pathway, whereas the movement of mineral nutrients is cycli ...

by recycling nutrients such as the fixation of nitrogen from the atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A s ...

. The nutrient cycle includes the decomposition

Decomposition or rot is the process by which dead organic substances are broken down into simpler organic or inorganic matter such as carbon dioxide, water, simple sugars and mineral salts. The process is a part of the nutrient cycle and is e ...

of dead bodies

''Dead Bodies'' is a 2003 Irish drama film by Robert Quinn starring Andrew Scott, Katy Davis, Eamonn Owens, Darren Healy and Kelly Reilly. The screenplay was written by Derek Landy.

Plot

Tommy McGann (Scott) gets back together with his ex-girlf ...

; bacteria are responsible for the putrefaction

Putrefaction is the fifth stage of death, following pallor mortis, algor mortis, rigor mortis, and livor mortis. This process references the breaking down of a body of an animal, such as a human, post-mortem. In broad terms, it can be viewed ...

stage in this process. In the biological communities surrounding hydrothermal vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspot ...

s and cold seep

A cold seep (sometimes called a cold vent) is an area of the ocean floor where hydrogen sulfide, methane and other hydrocarbon-rich fluid seepage occurs, often in the form of a brine pool. ''Cold'' does not mean that the temperature of the see ...

s, extremophile

An extremophile (from Latin ' meaning "extreme" and Greek ' () meaning "love") is an organism that is able to live (or in some cases thrive) in extreme environments, i.e. environments that make survival challenging such as due to extreme temper ...

bacteria provide the nutrients needed to sustain life by converting dissolved compounds, such as hydrogen sulphide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is poisonous, corrosive, and flammable, with trace amounts in ambient atmosphere having a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. The unde ...

and methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The relative abundance of methane on Eart ...

, to energy. Bacteria also live in symbiotic

Symbiosis (from Greek , , "living together", from , , "together", and , bíōsis, "living") is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasit ...

and parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has c ...

relationships with plants and animals. Most bacteria have not been characterised and there are many species that cannot be grown in the laboratory. The study of bacteria is known as bacteriology Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classificat ...

, a branch of microbiology

Microbiology () is the scientific study of microorganisms, those being unicellular (single cell), multicellular (cell colony), or acellular (lacking cells). Microbiology encompasses numerous sub-disciplines including virology, bacteriology, prot ...

.

Humans and most other animals carry millions of bacteria. Most are in the gut, and there are many on the skin. Most of the bacteria in and on the body are harmless or rendered so by the protective effects of the immune system

The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as cancer cells and objects such as wood splinte ...

, and many are beneficial, particularly the ones in the gut. However, several species of bacteria are pathogenic

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

and cause infectious disease

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dise ...

s, including cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

, syphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, an ...

, anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The sk ...

, leprosy

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease (HD), is a long-term infection by the bacteria ''Mycobacterium leprae'' or ''Mycobacterium lepromatosis''. Infection can lead to damage of the nerves, respiratory tract, skin, and eyes. This nerve damag ...

, tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

, tetanus

Tetanus, also known as lockjaw, is a bacterial infection caused by ''Clostridium tetani'', and is characterized by muscle spasms. In the most common type, the spasms begin in the jaw and then progress to the rest of the body. Each spasm usually ...

and bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium (''Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as well a ...

. The most common fatal bacterial diseases are respiratory infection

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are infectious diseases involving the respiratory tract. An infection of this type usually is further classified as an upper respiratory tract infection (URI or URTI) or a lower respiratory tract infection (LRI ...

s. Antibiotic

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention of ...

s are used to treat bacterial infections

Pathogenic bacteria are bacteria that can cause disease. This article focuses on the bacteria that are pathogenic to humans. Most species of bacteria are harmless and are often beneficial but others can cause infectious diseases. The number of t ...

and are also used in farming, making antibiotic resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from the effects of antimicrobials. All classes of microbes can evolve resistance. Fungi evolve antifungal resistance. Viruses evolve antiviral resistance. ...

a growing problem. Bacteria are important in sewage treatment

Sewage treatment (or domestic wastewater treatment, municipal wastewater treatment) is a type of wastewater treatment which aims to remove contaminants from sewage to produce an effluent that is suitable for discharge to the surrounding envir ...

and the breakdown of oil spill

An oil spill is the release of a liquid petroleum hydrocarbon into the environment, especially the marine ecosystem, due to human activity, and is a form of pollution. The term is usually given to marine oil spills, where oil is released into th ...

s, the production of cheese

Cheese is a dairy product produced in wide ranges of flavors, textures, and forms by coagulation of the milk protein casein. It comprises proteins and fat from milk, usually the milk of cows, buffalo, goats, or sheep. During production, ...

and yogurt

Yogurt (; , from tr, yoğurt, also spelled yoghurt, yogourt or yoghourt) is a food produced by bacterial Fermentation (food), fermentation of milk. The bacteria used to make yogurt are known as ''yogurt cultures''. Fermentation of sugars in t ...

through fermentation

Fermentation is a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes. In biochemistry, it is narrowly defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. In food ...

, the recovery of gold, palladium, copper and other metals in the mining sector, as well as in biotechnology

Biotechnology is the integration of natural sciences and engineering sciences in order to achieve the application of organisms, cells, parts thereof and molecular analogues for products and services. The term ''biotechnology'' was first used b ...

, and the manufacture of antibiotics and other chemicals.

Once regarded as plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclud ...

s constituting the class ''Schizomycetes'' ("fission fungi"), bacteria are now classified as prokaryotes

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connec ...

. Unlike cells of animals and other eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s, bacterial cells do not contain a nucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucle ...

and rarely harbour membrane-bound

A biological membrane, biomembrane or cell membrane is a selectively permeable membrane that separates the interior of a cell from the external environment or creates intracellular compartments by serving as a boundary between one part of the c ...

organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as organs are to the body, hence ''organelle,'' the ...

s. Although the term ''bacteria'' traditionally included all prokaryotes, the scientific classification

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

changed after the discovery in the 1990s that prokaryotes consist of two very different groups of organisms that evolved

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation t ...

from an ancient common ancestor. These evolutionary domains are called Bacteria and Archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

.

Etymology

The word ''bacteria'' is the plural of the

The word ''bacteria'' is the plural of the New Latin

New Latin (also called Neo-Latin or Modern Latin) is the revival of Literary Latin used in original, scholarly, and scientific works since about 1500. Modern scholarly and technical nomenclature, such as in zoological and botanical taxonomy ...

', which is the latinisation of the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

('), the diminutive

A diminutive is a root word that has been modified to convey a slighter degree of its root meaning, either to convey the smallness of the object or quality named, or to convey a sense of intimacy or endearment. A (abbreviated ) is a word-formati ...

of ('), meaning "staff, cane", because the first ones to be discovered were rod-shaped

A bacillus (), also called a bacilliform bacterium or often just a rod (when the context makes the sense clear), is a rod-shaped bacterium or archaeon. Bacilli are found in many different taxonomic groups of bacteria. However, the name ''Bacillu ...

.

Origin and early evolution

fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s exist, such as stromatolite

Stromatolites () or stromatoliths () are layered sedimentary formations (microbialite) that are created mainly by photosynthetic microorganisms such as cyanobacteria, sulfate-reducing bacteria, and Pseudomonadota (formerly proteobacteria). The ...

s, their lack of distinctive morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

*Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

*Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies, ...

prevents them from being used to examine the history of bacterial evolution, or to date the time of origin of a particular bacterial species. However, gene sequences can be used to reconstruct the bacterial phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

, and these studies indicate that bacteria diverged first from the archaeal/eukaryotic lineage. The most recent common ancestor

In biology and genetic genealogy, the most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as the last common ancestor (LCA) or concestor, of a set of organisms is the most recent individual from which all the organisms of the set are descended. The ...

of bacteria and archaea was probably a hyperthermophile

A hyperthermophile is an organism that thrives in extremely hot environments—from 60 °C (140 °F) upwards. An optimal temperature for the existence of hyperthermophiles is often above 80 °C (176 °F). Hyperthermophiles are often within the doma ...

that lived about 2.5 billion–3.2 billion years ago. The earliest life on land may have been bacteria some 3.22 billion years ago.

Bacteria were also involved in the second great evolutionary divergence, that of the archaea and eukaryotes. Here, eukaryotes resulted from the entering of ancient bacteria into endosymbiotic

An ''endosymbiont'' or ''endobiont'' is any organism that lives within the body or cells of another organism most often, though not always, in a mutualistic relationship.

(The term endosymbiosis is from the Greek: ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" ...

associations with the ancestors of eukaryotic cells, which were themselves possibly related to the Archaea. This involved the engulfment by proto-eukaryotic cells of alphaproteobacteria

Alphaproteobacteria is a class of bacteria in the phylum Pseudomonadota (formerly Proteobacteria). The Magnetococcales and Mariprofundales are considered basal or sister to the Alphaproteobacteria. The Alphaproteobacteria are highly diverse and p ...

l symbionts

Symbiosis (from Greek , , "living together", from , , "together", and , bíōsis, "living") is any type of a close and long-term biological interaction between two different biological organisms, be it mutualistic, commensalistic, or parasit ...

to form either mitochondria

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and Fungus, fungi. Mitochondria have a double lipid bilayer, membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosi ...

or hydrogenosome

A hydrogenosome is a membrane-enclosed organelle found in some anaerobic ciliates, flagellates, and fungi. Hydrogenosomes are highly variable organelles that have presumably evolved from protomitochondria to produce molecular hydrogen and ATP in ...

s, which are still found in all known Eukarya (sometimes in highly reduced form In statistics, and particularly in econometrics, the reduced form of a system of equations is the result of solving the system for the endogenous variables. This gives the latter as functions of the exogenous variables, if any. In econometrics, the ...

, e.g. in ancient "amitochondrial" protozoa). Later, some eukaryotes that already contained mitochondria also engulfed cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria (), also known as Cyanophyta, are a phylum of gram-negative bacteria that obtain energy via photosynthesis. The name ''cyanobacteria'' refers to their color (), which similarly forms the basis of cyanobacteria's common name, blu ...

-like organisms, leading to the formation of chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in ...

s in algae and plants. This is known as primary endosymbiosis

Symbiogenesis (endosymbiotic theory, or serial endosymbiotic theory,) is the leading evolutionary theory of the origin of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic organisms. The theory holds that mitochondria, plastids such as chloroplasts, and possi ...

.

Habitat

Bacteria are ubiquitous, living in every possible habitat on the planet including soil, underwater, deep in Earth's crust and even such extreme environments as acidic hot springs and radioactive waste. There are approximately 2×1030 bacteria on Earth, forming abiomass

Biomass is plant-based material used as a fuel for heat or electricity production. It can be in the form of wood, wood residues, energy crops, agricultural residues, and waste from industry, farms, and households. Some people use the terms bi ...

that is only exceeded by plants. They are abundant in lakes and oceans, in arctic ice, and geothermal springs

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a spring produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow bodies of magma (molten rock) or by circ ...

where they provide the nutrients needed to sustain life by converting dissolved compounds, such as hydrogen sulphide and methane, to energy. They live on and in plants and animals. Most do not cause diseases, are beneficial to their environments, and are essential for life. The soil is a rich source of bacteria and a few grams contain around a thousand million of them. They are all essential to soil ecology, breaking down toxic waste and recycling nutrients. They are even found in the atmosphere and one cubic metre of air holds around one hundred million bacterial cells. The oceans and seas harbour around 3 x 1026 bacteria which provide up to 50% of the oxygen humans breathe. Only around 2% of bacterial species have been fully studied.

Morphology

micrometre

The micrometre ( international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: μm) or micrometer (American spelling), also commonly known as a micron, is a unit of length in the International System of Unit ...

s in length. However, a few species are visible to the unaided eye—for example, ''Thiomargarita namibiensis

''Thiomargarita namibiensis'' is a Gram-negative coccoid bacterium, found in the ocean sediments of the continental shelf of Namibia. It is the second largest bacterium ever discovered, as a rule in diameter, but sometimes attaining . Cells of ...

'' is up to half a millimetre long, ''Epulopiscium fishelsoni

"''Candidatus'' Epulonipiscium" is a genus of Gram-positive bacteria that have a symbiotic relationship with surgeonfish. These bacteria are known for their unusually large size, many ranging from 200–700 μm in length. Until the discovery of ...

'' reaches 0.7 mm, and ''Thiomargarita magnifica

''Thiomargarita magnifica'' is a species of sulfur-oxidizing gammaproteobacteria, found growing underwater on the detached leaves of red mangroves from the Guadeloupe archipelago in the Lesser Antilles. This filament-shaped bacteria is the large ...

'' can reach even 2 cm in length, which is 50 times larger than other known bacteria. Among the smallest bacteria are members of the genus ''Mycoplasma

''Mycoplasma'' is a genus of bacteria that, like the other members of the class ''Mollicutes'', lack a cell wall around their cell membranes. Peptidoglycan (murein) is absent. This characteristic makes them naturally resistant to antibiotics ...

'', which measure only 0.3 micrometres, as small as the largest virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es. Some bacteria may be even smaller, but these ultramicrobacteria

Ultramicrobacteria are bacteria that are smaller than 0.1 μm3 under all growth conditions. This term was coined in 1981, describing cocci in seawater that were less than 0.3 μm in diameter. Ultramicrobacteria have also been recovered from soil a ...

are not well-studied.

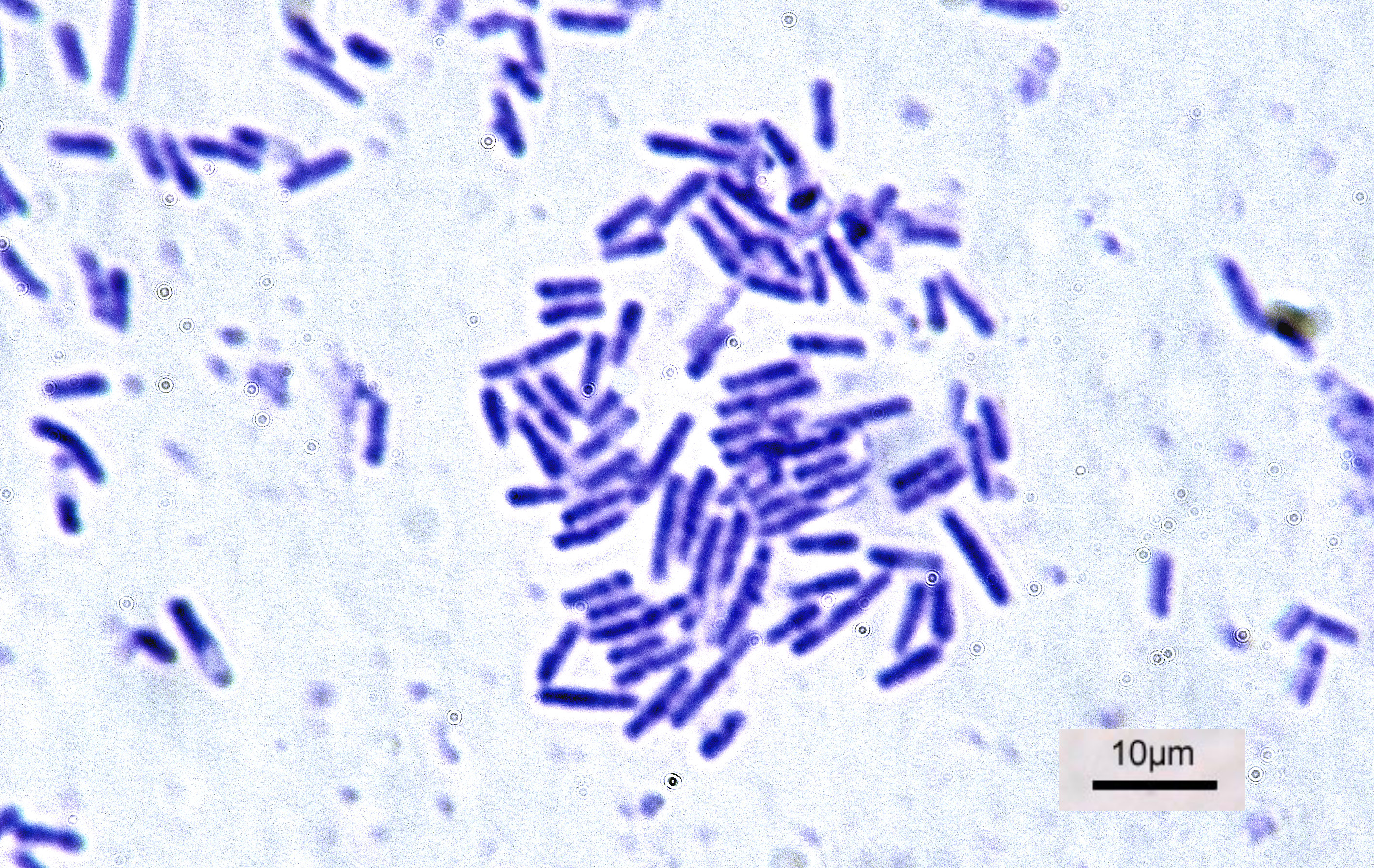

Shape. Most bacterial species are either spherical, called ''cocci

A coccus (plural cocci) is any bacterium or archaeon that has a spherical, ovoid, or generally round shape. Bacteria are categorized based on their shapes into three classes: cocci (spherical-shaped), bacillus (rod-shaped) and spiral ( of whi ...

'' (''singular coccus'', from Greek ''kókkos'', grain, seed), or rod shaped, called ''bacilli

Bacilli is a taxonomic class of bacteria that includes two orders, Bacillales and Lactobacillales, which contain several well-known pathogens such as ''Bacillus anthracis'' (the cause of anthrax). ''Bacilli'' are almost exclusively gram-positive ...

'' (''sing''. bacillus, from Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

''baculus'', stick). Some bacteria, called ''vibrio

''Vibrio'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria, possessing a curved-rod (comma) shape, several species of which can cause foodborne infection, usually associated with eating undercooked seafood. Being highly salt tolerant and unable to survive ...

'', are shaped like slightly curved rods or comma shaped; others can be spiral shaped, called '' spirilla'', or tightly coiled, called ''spirochaetes

A spirochaete () American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, or spirochete is a member of the phylum (biology), phylum Spirochaetota (), (synonym Spirochaetes) which contains distinctive diderm bacteria, diderm (double-membr ...

''. A small number of other unusual shapes have been described, such as star-shaped bacteria. This wide variety of shapes is determined by the bacterial cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mech ...

and cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is compos ...

, and is important because it can influence the ability of bacteria to acquire nutrients, attach to surfaces, swim through liquids and escape predators

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill the ...

.

Neisseria

''Neisseria'' is a large genus of bacteria that colonize the mucosal surfaces of many animals. Of the 11 species that colonize humans, only two are pathogens, '' N. meningitidis'' and ''N. gonorrhoeae''.

''Neisseria'' species are Gram-negativ ...

'' forms diploids (pairs), streptococci

''Streptococcus'' is a genus of gram-positive ' (plural ) or spherical bacteria that belongs to the family Streptococcaceae, within the order Lactobacillales (lactic acid bacteria), in the phylum Bacillota. Cell division in streptococci occurs ...

form chains, and staphylococci

''Staphylococcus'' is a genus of Gram-positive bacteria in the family Staphylococcaceae from the order Bacillales. Under the microscope, they appear spherical (cocci), and form in grape-like clusters. ''Staphylococcus'' species are facultative ...

group together in "bunch of grapes" clusters. Bacteria can also group to form larger multicellular structures, such as the elongated filaments of ''Actinomycetota

The ''Actinomycetota'' (or ''Actinobacteria'') are a phylum of all gram-positive bacteria. They can be terrestrial or aquatic. They are of great economic importance to humans because agriculture and forests depend on their contributions to soi ...

'' species, the aggregates of ''Myxobacteria

The myxobacteria ("slime bacteria") are a group of bacteria that predominantly live in the soil and feed on insoluble organic substances. The myxobacteria have very large genomes relative to other bacteria, e.g. 9–10 million nucleotides except ...

'' species, and the complex hyphae of ''Streptomyces

''Streptomyces'' is the largest genus of Actinomycetota and the type genus of the family Streptomycetaceae. Over 500 species of ''Streptomyces'' bacteria have been described. As with the other Actinomycetota, streptomycetes are gram-positive, ...

'' species. These multicellular structures are often only seen in certain conditions. For example, when starved of amino acids, myxobacteria detect surrounding cells in a process known as quorum sensing

In biology, quorum sensing or quorum signalling (QS) is the ability to detect and respond to cell population density by gene regulation. As one example, QS enables bacteria to restrict the expression of specific genes to the high cell densities at ...

, migrate towards each other, and aggregate to form fruiting bodies up to 500 micrometres long and containing approximately 100,000 bacterial cells. In these fruiting bodies, the bacteria perform separate tasks; for example, about one in ten cells migrate to the top of a fruiting body and differentiate into a specialised dormant state called a myxospore, which is more resistant to drying and other adverse environmental conditions.

Biofilms. Bacteria often attach to surfaces and form dense aggregations called biofilm

A biofilm comprises any syntrophic consortium of microorganisms in which cells stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy extracellular matrix that is composed of extracellular ...

s, and larger formations known as microbial mat

A microbial mat is a multi-layered sheet of microorganisms, mainly bacteria and archaea, or bacteria alone. Microbial mats grow at interfaces between different types of material, mostly on submerged or moist surfaces, but a few survive in deserts. ...

s. These biofilms and mats can range from a few micrometres in thickness to up to half a metre in depth, and may contain multiple species of bacteria, protist

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the exc ...

s and archaea. Bacteria living in biofilms display a complex arrangement of cells and extracellular components, forming secondary structures, such as microcolonies, through which there are networks of channels to enable better diffusion of nutrients. In natural environments, such as soil or the surfaces of plants, the majority of bacteria are bound to surfaces in biofilms. Biofilms are also important in medicine, as these structures are often present during chronic bacterial infections or in infections of implanted medical device

A medical device is any device intended to be used for medical purposes. Significant potential for hazards are inherent when using a device for medical purposes and thus medical devices must be proved safe and effective with reasonable assura ...

s, and bacteria protected within biofilms are much harder to kill than individual isolated bacteria.

Cellular structure

Intracellular structures

The bacterial cell is surrounded by acell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment ( ...

, which is made primarily of phospholipid

Phospholipids, are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s. This membrane encloses the contents of the cell and acts as a barrier to hold nutrients, protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s and other essential components of the cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

within the cell. Unlike eukaryotic cells

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the ...

, bacteria usually lack large membrane-bound structures in their cytoplasm such as a nucleus

Nucleus ( : nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucle ...

, mitochondria

A mitochondrion (; ) is an organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of most Eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and Fungus, fungi. Mitochondria have a double lipid bilayer, membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosi ...

, chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant and algal cells. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll captures the energy from sunlight, converts it, and stores it in ...

s and the other organelles present in eukaryotic cells. However, some bacteria have protein-bound organelles in the cytoplasm which compartmentalize aspects of bacterial metabolism, such as the carboxysome

Carboxysomes are bacterial microcompartments (BMCs) consisting of polyhedral protein shells filled with the enzymes ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO)—the predominant enzyme in carbon fixation and the rate limiting e ...

. Additionally, bacteria have a multi-component cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is compos ...

to control the localisation of proteins and nucleic acids within the cell, and to manage the process of cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell (biology), cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukar ...

.

Many important biochemical

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology an ...

reactions, such as energy generation, occur due to concentration gradients across membranes, creating a potential

Potential generally refers to a currently unrealized ability. The term is used in a wide variety of fields, from physics to the social sciences to indicate things that are in a state where they are able to change in ways ranging from the simple re ...

difference analogous to a battery. The general lack of internal membranes in bacteria means these reactions, such as electron transport

An electron transport chain (ETC) is a series of protein complexes and other molecules that transfer electrons from electron donors to electron acceptors via redox reactions (both reduction and oxidation occurring simultaneously) and couples thi ...

, occur across the cell membrane between the cytoplasm and the outside of the cell or periplasm

The periplasm is a concentrated gel-like matrix in the space between the inner cytoplasmic membrane and the bacterial outer membrane called the ''periplasmic space'' in gram-negative bacteria. Using cryo-electron microscopy it has been found that ...

. However, in many photosynthetic bacteria the plasma membrane is highly folded and fills most of the cell with layers of light-gathering membrane. These light-gathering complexes may even form lipid-enclosed structures called chlorosome

A chlorosome is a photosynthetic antenna complex found in green sulfur bacteria (GSB) and some green filamentous anoxygenic phototrophs (FAP) ( Chloroflexaceae, Oscillochloridaceae; both members of Chloroflexia). They differ from other antenna ...

s in green sulfur bacteria

The green sulfur bacteria are a phylum of obligately anaerobic photoautotrophic bacteria that metabolize sulfur.

Green sulfur bacteria are nonmotile (except ''Chloroherpeton thalassium'', which may glide) and capable of anoxygenic photosynthesi ...

.

Bacteria do not have a membrane-bound nucleus, and their

Bacteria do not have a membrane-bound nucleus, and their gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

tic material is typically a single circular bacterial chromosome

A circular chromosome is a chromosome in bacteria, archaea, mitochondria, and chloroplasts, in the form of a molecule of circular DNA, unlike the linear chromosome of most eukaryotes.

Most prokaryote chromosomes contain a circular DNA molecu ...

of DNA located in the cytoplasm in an irregularly shaped body called the nucleoid

The nucleoid (meaning ''nucleus-like'') is an irregularly shaped region within the prokaryotic cell that contains all or most of the genetic material. The chromosome of a prokaryote is circular, and its length is very large compared to the cell dim ...

. The nucleoid contains the chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

with its associated proteins and RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

. Like all other organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells (cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

s, bacteria contain ribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to ...

s for the production of proteins, but the structure of the bacterial ribosome is different from that of eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s and archaea.

Some bacteria produce intracellular nutrient storage granules, such as glycogen

Glycogen is a multibranched polysaccharide of glucose that serves as a form of energy storage in animals, fungi, and bacteria. The polysaccharide structure represents the main storage form of glucose in the body.

Glycogen functions as one o ...

, polyphosphate

Polyphosphates are salts or esters of polymeric oxyanions formed from tetrahedral PO4 (phosphate) structural units linked together by sharing oxygen atoms. Polyphosphates can adopt linear or a cyclic ring structures. In biology, the polyphosphate e ...

, sulfur

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula ...

or polyhydroxyalkanoates

Polyhydroxyalkanoates or PHAs are polyesters produced in nature by numerous microorganisms, including through bacterial fermentation of sugars or lipids. When produced by bacteria they serve as both a source of energy and as a carbon store. More ...

. Bacteria such as the photosynthetic

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored in c ...

cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria (), also known as Cyanophyta, are a phylum of gram-negative bacteria that obtain energy via photosynthesis. The name ''cyanobacteria'' refers to their color (), which similarly forms the basis of cyanobacteria's common name, blu ...

, produce internal gas vacuoles

Gas vesicles, also known as gas vacuoles, are nanocompartments in certain prokaryotic organisms, which help in buoyancy. Gas vesicles are composed entirely of protein; no lipids or carbohydrates have been detected.

Function

Gas vesicles occur ...

, which they use to regulate their buoyancy, allowing them to move up or down into water layers with different light intensities and nutrient levels.

Extracellular structures

Around the outside of the cell membrane is thecell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer surrounding some types of cells, just outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. It provides the cell with both structural support and protection, and also acts as a filtering mech ...

. Bacterial cell walls are made of peptidoglycan

Peptidoglycan or murein is a unique large macromolecule, a polysaccharide, consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like peptidoglycan layer outside the plasma membrane, the rigid cell wall (murein sacculus) characteristic of most ...

(also called murein), which is made from polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wa ...

chains cross-linked by peptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides.

A ...

s containing D-amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s. Bacterial cell walls are different from the cell walls of plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclud ...

s and fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

, which are made of cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell wall ...

and chitin

Chitin ( C8 H13 O5 N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is probably the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cellulose); an estimated 1 billion tons of chit ...

, respectively. The cell wall of bacteria is also distinct from that of achaea, which do not contain peptidoglycan. The cell wall is essential to the survival of many bacteria, and the antibiotic penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' moulds, principally '' P. chrysogenum'' and '' P. rubens''. Most penicillins in clinical use are synthesised by P. chrysogenum using ...

(produced by a fungus called ''Penicillium

''Penicillium'' () is a genus of ascomycetous fungi that is part of the mycobiome of many species and is of major importance in the natural environment, in food spoilage, and in food and drug production.

Some members of the genus produce pe ...

'') is able to kill bacteria by inhibiting a step in the synthesis of peptidoglycan.

There are broadly speaking two different types of cell wall in bacteria, that classify bacteria into Gram-positive bacteria

In bacteriology, gram-positive bacteria are bacteria that give a positive result in the Gram stain test, which is traditionally used to quickly classify bacteria into two broad categories according to their type of cell wall.

Gram-positive bact ...

and Gram-negative bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. They are characterized by their cell envelopes, which are composed of a thin peptidoglycan cell wall ...

. The names originate from the reaction of cells to the Gram stain

In microbiology and bacteriology, Gram stain (Gram staining or Gram's method), is a method of staining used to classify bacterial species into two large groups: gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative bacteria. The name comes from the Danish ...

, a long-standing test for the classification of bacterial species.

Gram-positive bacteria possess a thick cell wall containing many layers of peptidoglycan and teichoic acid

Teichoic acids (''cf.'' Greek τεῖχος, ''teīkhos'', "wall", to be specific a fortification wall, as opposed to τοῖχος, ''toīkhos'', a regular wall) are bacterial copolymers of glycerol phosphate or ribitol phosphate and carbohydr ...

s. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria have a relatively thin cell wall consisting of a few layers of peptidoglycan surrounded by a second lipid membrane

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes are flat sheets that form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many vir ...

containing lipopolysaccharide

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are large molecules consisting of a lipid and a polysaccharide that are bacterial toxins. They are composed of an O-antigen, an outer core, and an inner core all joined by a covalent bond, and are found in the outer m ...

s and lipoprotein

A lipoprotein is a biochemical assembly whose primary function is to transport hydrophobic lipid (also known as fat) molecules in water, as in blood plasma or other extracellular fluids. They consist of a triglyceride and cholesterol center, sur ...

s. Most bacteria have the Gram-negative cell wall, and only members of the ''Bacillota

The Bacillota (synonym Firmicutes) are a phylum of bacteria, most of which have gram-positive cell wall structure. The renaming of phyla such as Firmicutes in 2021 remains controversial among microbiologists, many of whom continue to use the earl ...

'' group and actinomycetota

The ''Actinomycetota'' (or ''Actinobacteria'') are a phylum of all gram-positive bacteria. They can be terrestrial or aquatic. They are of great economic importance to humans because agriculture and forests depend on their contributions to soi ...

(previously known as the low G+C and high G+C Gram-positive bacteria, respectively) have the alternative Gram-positive arrangement. These differences in structure can produce differences in antibiotic susceptibility; for instance, vancomycin

Vancomycin is a glycopeptide antibiotic medication used to treat a number of bacterial infections. It is recommended intravenously as a treatment for complicated skin infections, bloodstream infections, endocarditis, bone and joint infections, ...

can kill only Gram-positive bacteria and is ineffective against Gram-negative pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

s, such as ''Haemophilus influenzae

''Haemophilus influenzae'' (formerly called Pfeiffer's bacillus or ''Bacillus influenzae'') is a Gram-negative, non-motile, coccobacillary, facultatively anaerobic, capnophilic pathogenic bacterium of the family Pasteurellaceae. The bacteria ...

'' or ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa

''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' is a common encapsulated, gram-negative, aerobic–facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped bacterium that can cause disease in plants and animals, including humans. A species of considerable medical importance, ''P. aerugi ...

''. Some bacteria have cell wall structures that are neither classically Gram-positive or Gram-negative. This includes clinically important bacteria such as mycobacteria

''Mycobacterium'' is a genus of over 190 species in the phylum Actinomycetota, assigned its own family, Mycobacteriaceae. This genus includes pathogens known to cause serious diseases in mammals, including tuberculosis ('' M. tuberculosis'') and ...

which have a thick peptidoglycan cell wall like a Gram-positive bacterium, but also a second outer layer of lipids.

In many bacteria, an S-layer An S-layer (surface layer) is a part of the cell envelope found in almost all archaea, as well as in many types of bacteria.

The S-layers of both archaea and bacteria consists of a monomolecular layer composed of only one (or, in a few cases, two) i ...

of rigidly arrayed protein molecules covers the outside of the cell. This layer provides chemical and physical protection for the cell surface and can act as a macromolecular

A macromolecule is a very large molecule important to biophysical processes, such as a protein or nucleic acid. It is composed of thousands of covalently bonded atoms. Many macromolecules are polymers of smaller molecules called monomers. The ...

diffusion barrier A diffusion barrier is a thin layer (usually micrometres thick) of metal usually placed between two other metals. It is done to act as a barrier to protect either one of the metals from corrupting the other..

Adhesion of a plated metal layer to it ...

. S-layers have diverse functions and are known to act as virulence factors in ''Campylobacter

''Campylobacter'' (meaning "curved bacteria") is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria. ''Campylobacter'' typically appear comma- or s-shaped, and are motile. Some ''Campylobacter'' species can infect humans, sometimes causing campylobacteriosis, a d ...

'' species and contain surface enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

s in ''Bacillus stearothermophilus

''Geobacillus stearothermophilus'' (previously ''Bacillus stearothermophilus'') is a rod-shaped, Gram-positive bacterium and a member of the phylum Bacillota. The bacterium is a thermophile and is widely distributed in soil, hot springs, ocean s ...

''.

Flagella

A flagellum (; ) is a hairlike appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many protists with flagella are termed as flagellates.

A microorganism may have f ...

are rigid protein structures, about 20 nanometres in diameter and up to 20 micrometres in length, that are used for motility

Motility is the ability of an organism to move independently, using metabolic energy.

Definitions

Motility, the ability of an organism to move independently, using metabolic energy, can be contrasted with sessility, the state of organisms th ...

. Flagella are driven by the energy released by the transfer of ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conven ...

s down an electrochemical gradient

An electrochemical gradient is a gradient of electrochemical potential, usually for an ion that can move across a membrane. The gradient consists of two parts, the chemical gradient, or difference in solute concentration across a membrane, and th ...

across the cell membrane.

Fimbriae (sometimes called " attachment pili") are fine filaments of protein, usually 2–10 nanometres in diameter and up to several micrometres in length. They are distributed over the surface of the cell, and resemble fine hairs when seen under the electron microscope

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a hi ...

. Fimbriae are believed to be involved in attachment to solid surfaces or to other cells, and are essential for the virulence of some bacterial pathogens. Pili Pili may refer to:

Common names of plants

* ''Canarium ovatum'', a Philippine tree that is a source of the pili nut

* ''Heteropogon contortus'', a Hawaiian grass used to thatch structures

Places

* Pili, Camarines Sur, is a municipality in the ...

(''sing''. pilus) are cellular appendages, slightly larger than fimbriae, that can transfer genetic material

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main cla ...

between bacterial cells in a process called conjugation

Conjugation or conjugate may refer to:

Linguistics

* Grammatical conjugation, the modification of a verb from its basic form

* Emotive conjugation or Russell's conjugation, the use of loaded language

Mathematics

* Complex conjugation, the chang ...

where they are called conjugation pili or sex pili (see bacterial genetics, below). They can also generate movement where they are called type IV pili

A pilus (Latin for 'hair'; plural: ''pili'') is a hair-like appendage found on the surface of many bacteria and archaea. The terms ''pilus'' and '' fimbria'' (Latin for 'fringe'; plural: ''fimbriae'') can be used interchangeably, although some r ...

.

Glycocalyx

The glycocalyx, also known as the pericellular matrix, is a glycoprotein and glycolipid covering that surrounds the cell membranes of bacteria, epithelial cells, and other cells. In 1970, Martinez-Palomo discovered the cell coating in animal cells ...

is produced by many bacteria to surround their cells, and varies in structural complexity: ranging from a disorganised slime layer

A slime layer in bacteria is an easily removable (e.g. by centrifugation), unorganized layer of extracellular material that surrounds bacteria cells. Specifically, this consists mostly of exopolysaccharides, glycoproteins, and glycolipids. There ...

of extracellular polymeric substance

Extracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) are natural polymers of high molecular weight secreted by microorganisms into their environment. EPSs establish the functional and structural integrity of biofilms, and are considered the fundamental comp ...

s to a highly structured capsule. These structures can protect cells from engulfment by eukaryotic cells such as macrophage

Macrophages (abbreviated as M φ, MΦ or MP) ( el, large eaters, from Greek ''μακρός'' (') = large, ''φαγεῖν'' (') = to eat) are a type of white blood cell of the immune system that engulfs and digests pathogens, such as cancer cel ...

s (part of the human immune system

The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as cancer cells and objects such as wood splinte ...

). They can also act as antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule or molecular structure or any foreign particulate matter or a pollen grain that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response. ...

s and be involved in cell recognition, as well as aiding attachment to surfaces and the formation of biofilms.

The assembly of these extracellular structures is dependent on bacterial secretion system

Bacterial secretion systems are protein complexes present on the cell membranes of bacteria for secretion of substances. Specifically, they are the cellular devices used by pathogenic bacteria to secrete their virulence factors (mainly of protein ...

s. These transfer proteins from the cytoplasm into the periplasm or into the environment around the cell. Many types of secretion systems are known and these structures are often essential for the virulence

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its ability to ca ...

of pathogens, so are intensively studied.

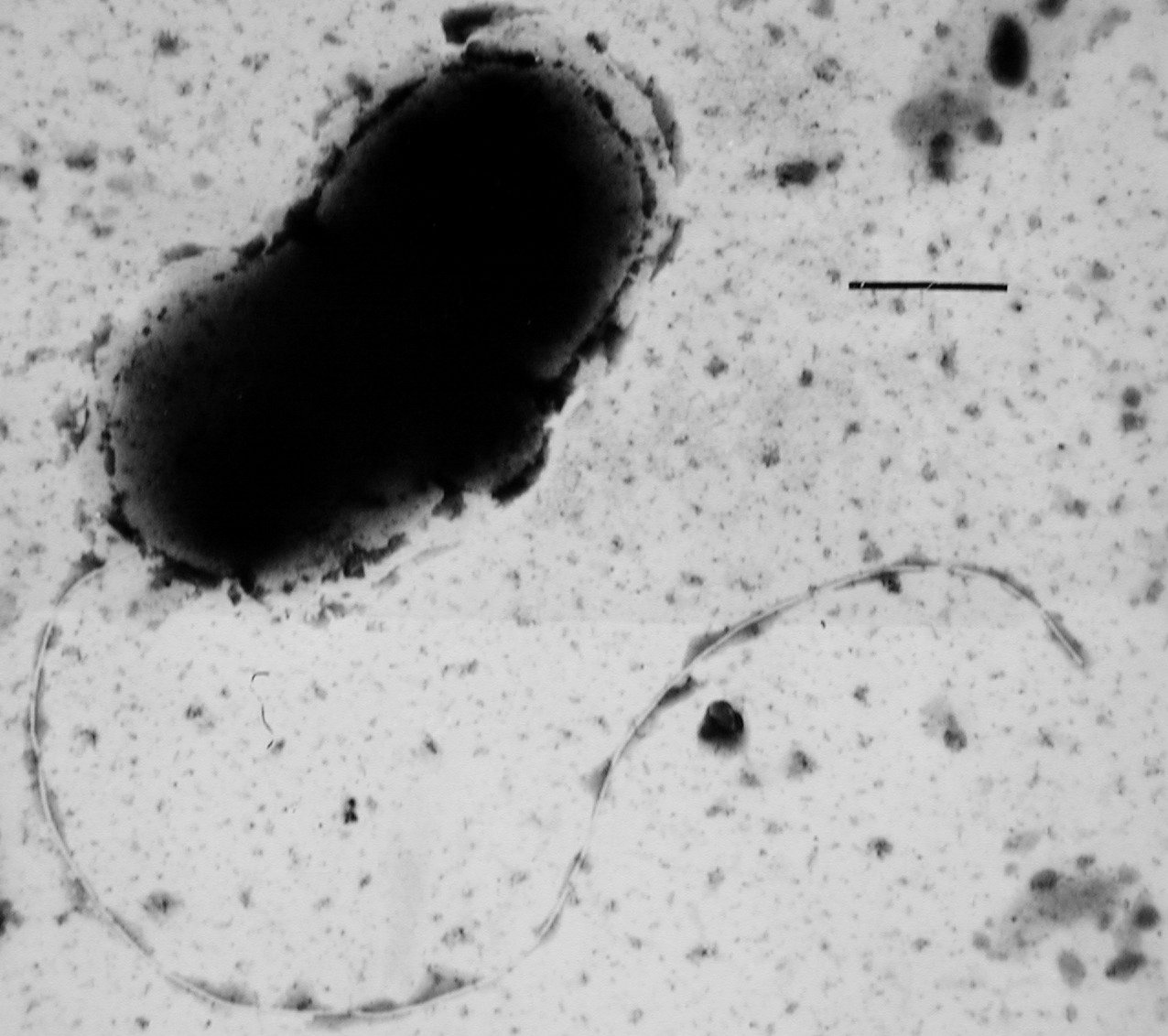

Endospores

Some

Some genera

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nomenclat ...

of Gram-positive bacteria, such as ''Bacillus

''Bacillus'' (Latin "stick") is a genus of Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria, a member of the phylum ''Bacillota'', with 266 named species. The term is also used to describe the shape (rod) of other so-shaped bacteria; and the plural ''Bacilli ...

'', ''Clostridium

''Clostridium'' is a genus of anaerobic, Gram-positive bacteria. Species of ''Clostridium'' inhabit soils and the intestinal tract of animals, including humans. This genus includes several significant human pathogens, including the causative ag ...

'', ''Sporohalobacter

''Sporohalobacter'' are a genus of anaerobic bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. ...

'', ''Anaerobacter

''Anaerobacter'' is a genus of Gram-positive bacteria related to '' Clostridium''. They are anaerobic chemotrophs and are unusual spore-formers as they produce more than one spore per bacterial cell (up to five). They fix nitrogen

Nitrogen ...

'', and '' Heliobacterium'', can form highly resistant, dormant structures called ''endospore

An endospore is a dormant, tough, and non-reproductive structure produced by some bacteria in the phylum Bacillota. The name "endospore" is suggestive of a spore or seed-like form (''endo'' means 'within'), but it is not a true spore (i.e., no ...

s''. Endospores develop within the cytoplasm of the cell; generally a single endospore develops in each cell. Each endospore contains a core of DNA and ribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to ...

s surrounded by a cortex layer and protected by a multilayer rigid coat composed of peptidoglycan and a variety of proteins.

Endospores show no detectable metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

and can survive extreme physical and chemical stresses, such as high levels of UV light

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation i ...

, gamma radiation

A gamma ray, also known as gamma radiation (symbol γ or \gamma), is a penetrating form of electromagnetic radiation arising from the radioactive decay of atomic nuclei. It consists of the shortest wavelength electromagnetic waves, typically s ...

, detergent

A detergent is a surfactant or a mixture of surfactants with cleansing properties when in dilute solutions. There are a large variety of detergents, a common family being the alkylbenzene sulfonates, which are soap-like compounds that are more ...

s, disinfectant

A disinfectant is a chemical substance or compound used to inactivate or destroy microorganisms on inert surfaces. Disinfection does not necessarily kill all microorganisms, especially resistant bacterial spores; it is less effective than st ...

s, heat, freezing, pressure, and desiccation

Desiccation () is the state of extreme dryness, or the process of extreme drying. A desiccant is a hygroscopic (attracts and holds water) substance that induces or sustains such a state in its local vicinity in a moderately sealed container.

...

. In this dormant state, these organisms may remain viable for millions of years, and endospores even allow bacteria to survive exposure to the vacuum

A vacuum is a space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective ''vacuus'' for "vacant" or "void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressure. Physicists often dis ...

and radiation in space, possibly bacteria could be distributed throughout the Universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. Acc ...

by space dust

Cosmic dust, also called extraterrestrial dust, star dust or space dust, is dust which exists in outer space, or has fallen on Earth. Most cosmic dust particles measure between a few molecules and 0.1 mm (100 micrometers). Larger particles are c ...

, meteoroids, asteroids, comets, Small Solar System body, planetoids or via directed panspermia. Endospore-forming bacteria can also cause disease: for example, anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis''. It can occur in four forms: skin, lungs, intestinal, and injection. Symptom onset occurs between one day and more than two months after the infection is contracted. The sk ...

can be contracted by the inhalation of ''Bacillus anthracis'' endospores, and contamination of deep puncture wounds with ''Clostridium tetani'' endospores causes tetanus

Tetanus, also known as lockjaw, is a bacterial infection caused by ''Clostridium tetani'', and is characterized by muscle spasms. In the most common type, the spasms begin in the jaw and then progress to the rest of the body. Each spasm usually ...

, which like botulism is caused by a toxin released by the bacteria that grow from the spores. Clostridioides difficile infection, which is a problem in healthcare settings is also caused by spore-forming bacteria.

Metabolism