Attack on Richard Nixon's motorcade on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An attack on Richard Nixon's motorcade occurred in

Nixon's final stop before Venezuela and

Nixon's final stop before Venezuela and

Nixon arrived, via air, in Caracas on May 13, 1958. According to a U.S. Secret Service report of the incident, a crowd of demonstrators at the airport "purposely disrupted ... hewelcoming ceremony by shouting, blowing whistles, waving derogatory placards, throwing stones, and showering the Nixons with human spittle and chewing tobacco". Reporting for the ''

Nixon arrived, via air, in Caracas on May 13, 1958. According to a U.S. Secret Service report of the incident, a crowd of demonstrators at the airport "purposely disrupted ... hewelcoming ceremony by shouting, blowing whistles, waving derogatory placards, throwing stones, and showering the Nixons with human spittle and chewing tobacco". Reporting for the '' The original itinerary had Nixon moving from the airport to the National Pantheon of Venezuela where he was to lay a wreath at the tomb of

The original itinerary had Nixon moving from the airport to the National Pantheon of Venezuela where he was to lay a wreath at the tomb of

According to U.S. officials at the time, the forces mobilized were being readied to enter Venezuela to "cooperate with the Venezuelan government", though later accounts suggest President Eisenhower was preparing to "invade Venezuela" should Nixon suffer further indignity. Privately, Eisenhower was reportedly furious at the attack on Nixon and, at one point, told his staff "I am about ready to go put my uniform on".

Nixon was shocked after learning about the mobilization and wondered why they were not consulted, but later found out that communications between Caracas and Washington had been cut for a critical period immediately after the riot that afternoon.

In response to the movement of American military forces into the region, Admiral Larrazábal pledged the Nixon party would be "protected fully" thereafter.

According to U.S. officials at the time, the forces mobilized were being readied to enter Venezuela to "cooperate with the Venezuelan government", though later accounts suggest President Eisenhower was preparing to "invade Venezuela" should Nixon suffer further indignity. Privately, Eisenhower was reportedly furious at the attack on Nixon and, at one point, told his staff "I am about ready to go put my uniform on".

Nixon was shocked after learning about the mobilization and wondered why they were not consulted, but later found out that communications between Caracas and Washington had been cut for a critical period immediately after the riot that afternoon.

In response to the movement of American military forces into the region, Admiral Larrazábal pledged the Nixon party would be "protected fully" thereafter.

In Venezuela, all major presidential candidates standing in the 1958 general election denounced the attack except for the incumbent president, Admiral Larrazábal. After Nixon's departure, Larrazábal said that he would have joined the protests if he were a student. Although receiving strong backing by the communists, Larrazábal lost the election to Rómulo Betancourt.

During the 1961 visit of U.S. President John F. Kennedy to Venezuela, anti-American violence also broke out, however, a repeat of the 1958 attack was avoided. President Betancourt pre-deployed significant Venezuelan military forces into Caracas in advance of Kennedy's arrival and ordered the preventive arrest of suspected ringleaders. All of the highway Kennedy was scheduled to travel from the airport, the same highway traveled by Nixon, were closed effective the day before Kennedy's arrival.

A 2013 editorial on the attack published by the

In Venezuela, all major presidential candidates standing in the 1958 general election denounced the attack except for the incumbent president, Admiral Larrazábal. After Nixon's departure, Larrazábal said that he would have joined the protests if he were a student. Although receiving strong backing by the communists, Larrazábal lost the election to Rómulo Betancourt.

During the 1961 visit of U.S. President John F. Kennedy to Venezuela, anti-American violence also broke out, however, a repeat of the 1958 attack was avoided. President Betancourt pre-deployed significant Venezuelan military forces into Caracas in advance of Kennedy's arrival and ordered the preventive arrest of suspected ringleaders. All of the highway Kennedy was scheduled to travel from the airport, the same highway traveled by Nixon, were closed effective the day before Kennedy's arrival.

A 2013 editorial on the attack published by the

Various sources describe the attack as one that nearly led to Nixon's death and, though it is generally agreed he acted with remarkable composure throughout, the incident had a lasting impact on him. In his first book, ''

Various sources describe the attack as one that nearly led to Nixon's death and, though it is generally agreed he acted with remarkable composure throughout, the incident had a lasting impact on him. In his first book, ''

Caracas

Caracas (, ), officially Santiago de León de Caracas, abbreviated as CCS, is the capital and largest city of Venezuela, and the center of the Metropolitan Region of Caracas (or Greater Caracas). Caracas is located along the Guaire River in the ...

, Venezuela, on May 13, 1958, during his goodwill tour of South America, undertaken while Nixon was Vice President of the United States. The attack on Nixon's car was called, at the time, the "most violent attack ever perpetrated on a high American official while on foreign soil." Close to being killed while a couple of his aides were injured in the melee, Nixon ended up unharmed and his entourage managed to reach the U.S. embassy. The visit took place only months after the overthrow in January of Venezuelan dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez, who in 1954 had been awarded the Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements. The decoration is issued to members of the eight ...

and was later granted asylum by the United States, and the incident may have been orchestrated by the Communist Party of Venezuela. U.S. Navy Admiral Arleigh Burke

Arleigh Albert Burke (October 19, 1901 – January 1, 1996) was an admiral of the United States Navy who distinguished himself during World War II and the Korean War, and who served as Chief of Naval Operations during the Eisenhower and Kenne ...

mobilized fleet and Marine units to the region, compelling the Venezuelan government to provide full protection to Nixon for the remainder of the trip.

The attack was denounced by all major Venezuelan presidential candidates standing in that year's election, except for the incumbent leader Admiral Wolfgang Larrazábal

Rear Admiral Wolfgang Enrique Larrazábal Ugueto (; 5 March 1911 – 27 February 2003) was a Venezuelan naval officer and politician. He served as the president of Venezuela following the overthrow of Marcos Pérez Jiménez on 23 January 1 ...

. Nixon was generally applauded in American press reports for his calm and adept handling of the incident and was feted with a "hero's welcome" on his return to the United States. His recollections of the attack form one of the "six crises" explored in his 1962 ''Six Crises

6 is a number, numeral, and glyph.

6 or six may also refer to:

* AD 6, the sixth year of the AD era

* 6 BC, the sixth year before the AD era

* The month of June

Science

* Carbon, the element with atomic number 6

* 6 Hebe, an asteroid

People

...

'' book.

Context

Richard Nixon's carefully planned 1958 tour of South America has been described as one of the "most important United States foreign policy events in post-WWII Latin America". It was undertaken at a time of confused United States intra-hemispheric relations; the role of Latin American states in the emerging American grand strategy of containment was unclear and ill-defined. However, a recent worldwide drop incommodity

In economics, a commodity is an economic good, usually a resource, that has full or substantial fungibility: that is, the market treats instances of the good as equivalent or nearly so with no regard to who produced them.

The price of a comm ...

prices that badly affected South American economies, coupled with increasing Soviet overtures in the western hemisphere, made President of the United States Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

determine that a tour by a major United States functionary was necessary to demonstrate U.S. commitment to the region. Nixon retrospectively wrote that he was uninterested in taking the trip.

The tour was to see Nixon visit every independent country in South America except Brazil and Chile. Brazil had been omitted from the itinerary as Nixon had visited that nation the previous year. The Chilean leadership, meanwhile, were scheduled to be out of the country during the time period of Nixon's visit. Nixon was accompanied on his trip by his wife, Pat Nixon.

Early tour stops

Nixon began his tour in Uruguay, arriving at Carrasco International Airport at 9:00 a.m. on April 28. There, he was greeted by senior Uruguayan officials. According to an Associated Press report at the time, about 40 students protested on the street corner as Nixon's motorcade proceeded into Montevideo. InMontevideo

Montevideo () is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

, Nixon made an unscheduled appearance at the University of the Republic

The University of the Republic ( es, Universidad de la República, sometimes ''UdelaR'') is Uruguay's oldest public university. It is by far the country's largest university, as well as the second largest public university in South America and t ...

and was generally well received by students. According to Nixon, he decided to make the unannounced stop because he felt that average Uruguayans would be receptive towards him, while scheduled and published visits were likely to attract organized demonstrations. This proved to be the case, and when communists arrived and tried to distribute literature, the students tore up the pamphlets.

The visit to Argentina was billed as the major stop of the trip and four days were allotted to the country, instead of the two slated for the other visits. In Buenos Aires, Nixon attended the presidential inauguration of Arturo Frondizi and spoke to several student and organized labor groups.

The first serious trouble on the tour materialized in Lima, Peru. Nixon's scheduled appearance at the University of San Marcos saw a large crowd of student demonstrators awaiting his arrival. In an event foreshadowing his famous visit to the Lincoln Memorial to meet anti-war protesters some years later, Nixon waded directly into the crowd of demonstrators, attended by only two staff members. Over the next few minutes Nixon spoke with the students. However, a second faction of demonstrators soon began stoning the group, hitting one of Nixon's staff in the mouth and grazing the vice-president's neck. The vice-president then withdrew and a later round-table with student leaders was canceled. Returning to his hotel, Nixon and his staff had to push through demonstrators who had encamped outside, during which Nixon was struck in the face. Eisenhower cabled Nixon at his next stop, in Quito

Quito (; qu, Kitu), formally San Francisco de Quito, is the capital and largest city of Ecuador, with an estimated population of 2.8 million in its urban area. It is also the capital of the province of Pichincha. Quito is located in a valley o ...

, Ecuador:

Nixon's final stop before Venezuela and

Nixon's final stop before Venezuela and Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

saw generally receptive crowds. At Bolívar Square in Bogotá

Bogotá (, also , , ), officially Bogotá, Distrito Capital, abbreviated Bogotá, D.C., and formerly known as Santa Fe de Bogotá (; ) during the Spanish period and between 1991 and 2000, is the capital city of Colombia, and one of the larges ...

, he laid a wreath at the statue of Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios (24 July 1783 – 17 December 1830) was a Venezuelan military and political leader who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama and B ...

before a crowd of about 1,000. An Associated Press report noted that there were some hecklers in the audience, but they amounted to "about 80 youths" and observed that "generally ... the Colombian crowds were friendly or enthusiastic".

Tour in Venezuela

Background

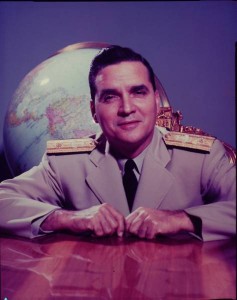

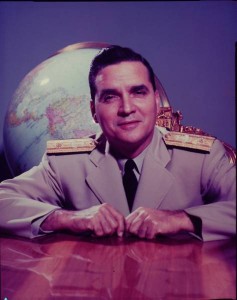

Earlier in 1958, the disliked Venezuelan dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez had been overthrown in a popular uprising and had gone into exile in the United States. A military junta formed a caretaker government to rule the country until new elections could be held. AdmiralWolfgang Larrazábal

Rear Admiral Wolfgang Enrique Larrazábal Ugueto (; 5 March 1911 – 27 February 2003) was a Venezuelan naval officer and politician. He served as the president of Venezuela following the overthrow of Marcos Pérez Jiménez on 23 January 1 ...

, head of the governing junta, had announced his intention to stand in those elections; his candidacy was backed by a coalition of parties, including the Venezuelan Communist Party

The Communist Party of Venezuela ( es, Partido Comunista de Venezuela, PCV) is a communist party and the oldest continuously existing party in Venezuela. It was the main leftist political party in Venezuela from its foundation in 1931 until it ...

. The United States' earlier decision to award Pérez Jiménez the Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements. The decoration is issued to members of the eight ...

on 12 November 1954 and after his overthrow to grant him asylum combined to create a charged atmosphere leading up to Nixon's arrival. The Caracas municipal council even passed a resolution effectively declaring Nixon ''persona non grata

In diplomacy, a ' (Latin: "person not welcome", plural: ') is a status applied by a host country to foreign diplomats to remove their protection of diplomatic immunity from arrest and other types of prosecution.

Diplomacy

Under Article 9 of the ...

''. Prior to Nixon's arrival in Caracas, media reported on rumors that an attempt had been planned on the vice-president's life during his visit. The CIA station chief

The station chief, also called chief of station (COS), is the top U.S. Central Intelligence Agency official stationed in a foreign country, equivalent to a KGB Resident. Often the COS has an office in the American Embassy. The station chief is the ...

in Venezuela, meanwhile, urged that this leg of the trip be canceled.

In an interview conducted after he retired from government service, Robert Amerson, then-press attache to the United States embassy in Venezuela, claims that the demonstrators who disrupted the Venezuela stop on the tour "had been bused down by the professional agitators and organizers" affiliated with the Communist Party of Venezuela. This view was one echoed in a report issued by William P. Snow, acting Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs, who wrote that "the pattern of organization and of slogans in all cases points to Communist inspiration and direction, as do certain of the intelligence reports". Nixon, himself, also blamed Communist instigation. A Universal Newsreel at the time characterized it as "another of the well-planned campaigns of harassment" and a "communist-sparked onslaught". Venezuelan journalist Carlos Rangel

Carlos Rangel (17 September 1929 – 15 January 1988) was a Venezuelan liberal writer, journalist and diplomat.

Background

Carlos Enrique Rangel Guevara was born in Caracas on 17 September 1929. His parents were José Antonio Rangel Báez and ...

has indicated the "Nixon carnival" was organized by the Venezuelan Communist Party as a way of demonstrating that it had the ability to "dominate the streets, that the Caracas masses were ready to be mobilized".

Arrival

Nixon arrived, via air, in Caracas on May 13, 1958. According to a U.S. Secret Service report of the incident, a crowd of demonstrators at the airport "purposely disrupted ... hewelcoming ceremony by shouting, blowing whistles, waving derogatory placards, throwing stones, and showering the Nixons with human spittle and chewing tobacco". Reporting for the ''

Nixon arrived, via air, in Caracas on May 13, 1958. According to a U.S. Secret Service report of the incident, a crowd of demonstrators at the airport "purposely disrupted ... hewelcoming ceremony by shouting, blowing whistles, waving derogatory placards, throwing stones, and showering the Nixons with human spittle and chewing tobacco". Reporting for the ''New York Herald Tribune

The ''New York Herald Tribune'' was a newspaper published between 1924 and 1966. It was created in 1924 when Ogden Mills Reid of the ''New-York Tribune'' acquired the ''New York Herald''. It was regarded as a "writer's newspaper" and competed ...

'', Earl Mazo

Earl Mazo (July 7, 1919 – February 17, 2007) was an American journalist, author, and government official.

Education and early life

Born in Warsaw, Poland, Mazo migrated to the United States as a small child with his parents, Sonia and George ...

wrote that "Venezuelan troops and police seemed to evaporate. The vice-president and the whole official party literally had to fight their way to cars behind a thin but sturdy phalanx of U.S. Secret Service agents".

The original itinerary had Nixon moving from the airport to the National Pantheon of Venezuela where he was to lay a wreath at the tomb of

The original itinerary had Nixon moving from the airport to the National Pantheon of Venezuela where he was to lay a wreath at the tomb of Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios (24 July 1783 – 17 December 1830) was a Venezuelan military and political leader who led what are currently the countries of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama and B ...

. However, a United States naval attache sent ahead with the wreath reported a crowd that had assembled at the Pantheon had attacked him and torn up the wreath. At this point it was decided to proceed directly to the U.S. embassy.

Attack

For the first time on the South America tour, the Nixons traveled in closed-top cars, as opposed to convertibles, a decision later credited with saving their lives. As the Nixons traveled by motorcade through Caracas, the vehicle carrying the vice-president was slowed to a crawl by heavy traffic. A crowd used the stoppage to throng Nixon's vehicle, stoning it and banging the windows with their fists. Nixon was protected by twelve United States Secret Service agents, some of whom were injured in the melee. According to the Secret Service, Venezuelan police declined to intervene to clear the crowd. When the mob began rocking the car back and forth in an attempt to overturn it, U.S. Secret Service agents, believing the vice-president's life was in jeopardy, drew their firearms and prepared to begin shooting into the crowd. In an act described as "the kind of presence of mind for which battlefield commanders win medals", Nixon ordered Secret Service agent-in-charge Jack Sherwood to hold fire and shoot only on his orders; no shots were ultimately fired. Nixon would later recount that Venezuelan Foreign Minister Óscar García Velutini, who was traveling with him, was "close to hysterics" and kept repeating "this is terrible, this is terrible". According to Nixon, Velutini explained the police inaction was because the communists "helped us overthrow Pérez Jiménez and we are trying to find a way to work with them". Nixon's longtime secretary,Rose Mary Woods

Rose Mary Woods (December 26, 1917 – January 22, 2005) was Richard Nixon's secretary from his days in Congress in 1951 through the end of his political career. Before H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman became the operators of Nixon's presi ...

, was injured by flying glass when the windows of the car in which she was riding, following Nixon, were smashed. Vernon Walters

Vernon Anthony Walters (January 3, 1917 – February 10, 2002) was a United States Army officer and a diplomat. Most notably, he served from 1972 to 1976 as Deputy Director of Central Intelligence, from 1985 to 1989 as the United States Ambassa ...

, then a mid-ranking U.S. Army officer serving as Nixon's translator, would end up with a "mouthful of glass", and Velutini was also hit by shards of the limousine's supposedly "shatter-proof" glass.

Two different accounts explain how Nixon's car was ultimately able to escape the mob and continue to the embassy. According to one version of events, the U.S. press corps' flatbed truck, accompanying the motorcade, was used to clear a path through the crowd. In Nixon's remembrance of the incident, Associated Press photographer Hank Griffin at one point had to use his camera to beat back a protester who tried to mount the truck. According to a second account, soldiers of the Venezuelan Army

The Venezuelan Army, officially the National Army of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, Ejército Nacional de la República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is one of the six professional branches of the Armed Forces of Venezuela. Also known ...

arrived and cleared the traffic, thereafter moving the mob back at bayonet

A bayonet (from French ) is a knife, dagger, sword, or spike-shaped weapon designed to fit on the end of the muzzle of a rifle, musket or similar firearm, allowing it to be used as a spear-like weapon.Brayley, Martin, ''Bayonets: An Illustr ...

-point to allow Nixon's car to pass.

Embassy

Shortly after the Nixons arrived at the embassy, the Venezuelan army surrounded and fortified the chancellery, reinforcing the small U.S. Marine guard force. Their assistance had earlier been requested by the U.S. ambassador. That afternoon, members of the ruling junta arrived at the embassy and lunched with Nixon. The next morning, representatives of Venezuela's major labor unions came to the embassy and requested an audience with Nixon, which was granted. The union leaders apologized for events of the preceding day and disclaimed involvement, though, United States Air Force officer Manuel Chavez – at the time attached to the embassy – wrote in 2015 that "they probably were the instigators or at least encouraged the actions".U.S. mobilization

Upon learning of the incident,Chief of Naval Operations

The chief of naval operations (CNO) is the professional head of the United States Navy. The position is a statutory office () held by an admiral who is a military adviser and deputy to the secretary of the Navy. In a separate capacity as a memb ...

Admiral Arleigh Burke

Arleigh Albert Burke (October 19, 1901 – January 1, 1996) was an admiral of the United States Navy who distinguished himself during World War II and the Korean War, and who served as Chief of Naval Operations during the Eisenhower and Kenne ...

ordered the airlift of elements of the 2nd Marine Division

The 2nd Marine Division (2nd MARDIV) is a division of the United States Marine Corps, which forms the ground combat element of the II Marine Expeditionary Force (II MEF). The division is based at Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, North Carolina ...

and the 101st Airborne Division

The 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) ("Screaming Eagles") is a light infantry division of the United States Army that specializes in air assault operations. It can plan, coordinate, and execute multiple battalion-size air assault operati ...

to staging areas in Puerto Rico and Guantánamo Bay

Guantánamo Bay ( es, Bahía de Guantánamo) is a bay in Guantánamo Province at the southeastern end of Cuba. It is the largest harbor on the south side of the island and it is surrounded by steep hills which create an enclave that is cut off ...

, Cuba. The aircraft carrier , along with eight destroyers and two amphibious assault ships, were ordered to put to sea towards Venezuela. The U.S. mobilization was code-named "Operation Poor Richard".

According to U.S. officials at the time, the forces mobilized were being readied to enter Venezuela to "cooperate with the Venezuelan government", though later accounts suggest President Eisenhower was preparing to "invade Venezuela" should Nixon suffer further indignity. Privately, Eisenhower was reportedly furious at the attack on Nixon and, at one point, told his staff "I am about ready to go put my uniform on".

Nixon was shocked after learning about the mobilization and wondered why they were not consulted, but later found out that communications between Caracas and Washington had been cut for a critical period immediately after the riot that afternoon.

In response to the movement of American military forces into the region, Admiral Larrazábal pledged the Nixon party would be "protected fully" thereafter.

According to U.S. officials at the time, the forces mobilized were being readied to enter Venezuela to "cooperate with the Venezuelan government", though later accounts suggest President Eisenhower was preparing to "invade Venezuela" should Nixon suffer further indignity. Privately, Eisenhower was reportedly furious at the attack on Nixon and, at one point, told his staff "I am about ready to go put my uniform on".

Nixon was shocked after learning about the mobilization and wondered why they were not consulted, but later found out that communications between Caracas and Washington had been cut for a critical period immediately after the riot that afternoon.

In response to the movement of American military forces into the region, Admiral Larrazábal pledged the Nixon party would be "protected fully" thereafter.

Return to the United States

Additional activities were canceled, and Nixon departed Caracas the next morning, seven hours early. His motorcade to the airport was protected by a major deployment of Venezuelan Army infantry and armored forces in the capital. Nixon described having taken the same route as before, whose streets were empty and heavily patrolled after the whole area had been tear-gassed.American reaction

Eisenhower ordered that Nixon should receive a "hero's welcome" on his return; all U.S. government employees in Washington, D.C. were given the day off work to turn-out for the arrival of the vice-president. Nixon deplaned before "a cheering crowd of 10,000" that included the congressional leadership and ambassadors from most Latin American countries. Eisenhower personally greeted Nixon at the airport and the two then traveled to the White House along a route lined by 100,000 people. '' Life'' credited Nixon for his "courage" and said "his coolness had been remarkable". According to Pathé News, Nixon reflected "calm, rather than concern." For weeks after the attack, Nixon received standing ovations "wherever he went ... a new high in his life". By contrast, '' The New Republic'' claimed the attack was a hoax set up to help Nixon's chances in the1960 U.S. presidential election

The 1960 United States presidential election was the 44th quadrennial presidential election. It was held on Tuesday, November 8, 1960. In a closely contested election, Democratic United States Senator John F. Kennedy defeated the incumbent Vi ...

.

All twelve agents of Nixon's Secret Service detail received the Decoration for Exceptional Civilian Service from Eisenhower at Nixon's request.

Venezuelan reaction

In Venezuela, all major presidential candidates standing in the 1958 general election denounced the attack except for the incumbent president, Admiral Larrazábal. After Nixon's departure, Larrazábal said that he would have joined the protests if he were a student. Although receiving strong backing by the communists, Larrazábal lost the election to Rómulo Betancourt.

During the 1961 visit of U.S. President John F. Kennedy to Venezuela, anti-American violence also broke out, however, a repeat of the 1958 attack was avoided. President Betancourt pre-deployed significant Venezuelan military forces into Caracas in advance of Kennedy's arrival and ordered the preventive arrest of suspected ringleaders. All of the highway Kennedy was scheduled to travel from the airport, the same highway traveled by Nixon, were closed effective the day before Kennedy's arrival.

A 2013 editorial on the attack published by the

In Venezuela, all major presidential candidates standing in the 1958 general election denounced the attack except for the incumbent president, Admiral Larrazábal. After Nixon's departure, Larrazábal said that he would have joined the protests if he were a student. Although receiving strong backing by the communists, Larrazábal lost the election to Rómulo Betancourt.

During the 1961 visit of U.S. President John F. Kennedy to Venezuela, anti-American violence also broke out, however, a repeat of the 1958 attack was avoided. President Betancourt pre-deployed significant Venezuelan military forces into Caracas in advance of Kennedy's arrival and ordered the preventive arrest of suspected ringleaders. All of the highway Kennedy was scheduled to travel from the airport, the same highway traveled by Nixon, were closed effective the day before Kennedy's arrival.

A 2013 editorial on the attack published by the Bolivarian

Bolivarianism is a mix of panhispanic, socialist and national- patriotic ideals named after Simón Bolívar, the 19th-century Venezuelan general and liberator from the Spanish monarchy then in abeyance, who led the struggle for independence th ...

radio station Alba Ciudad disputed the characterization of the incident, explaining that, "no one forced him ixonto stay on Venezuelan soil, no one had him abducted, no one was blocking him or holding him in the country. To the contrary, people asked him to leave!"

Significance

Pathé News, at the time, described the assault as "the most violent attack ever perpetrated on a high American official while on foreign soil". Various sources describe the attack as one that nearly led to Nixon's death and, though it is generally agreed he acted with remarkable composure throughout, the incident had a lasting impact on him. In his first book, ''

Various sources describe the attack as one that nearly led to Nixon's death and, though it is generally agreed he acted with remarkable composure throughout, the incident had a lasting impact on him. In his first book, ''Six Crises

6 is a number, numeral, and glyph.

6 or six may also refer to:

* AD 6, the sixth year of the AD era

* 6 BC, the sixth year before the AD era

* The month of June

Science

* Carbon, the element with atomic number 6

* 6 Hebe, an asteroid

People

...

'', Nixon wrote of the experience as one of the titular crises with great impact on his life.

Every year on the anniversary of the attack, Nixon would "privately celebrate" with Vernon Walters. Nixon would favor Walters for the rest of his career, eventually appointing him Deputy Director of Central Intelligence. On the eve of Walters' retirement from government service, in 1991, Nixon explained his longtime patronage of the general, writing him that "you and I have faced death together and that gives us a special bond".

The hardening of Nixon's attitude toward Latin America, which he came to "equate with violence and irrationality", has been attributed to his experience of the attack. Some believe this change of mood foreshadowed his subsequent support for covert U.S. actions directed in support of dictatorial regimes in the region. In fact, he would later privately list several nations whose populations, he believed, were too immature for democratic government and would be better administered by authoritarian regimes, specifically citing France, Italy, and all of Latin America "except for Colombia".

The incident has been credited with first making American policymakers aware of growing popular resentment to U.S. policies in Latin America. By the end of 1958, the U.S. National Security Council

The United States National Security Council (NSC) is the principal forum used by the President of the United States for consideration of national security, military, and foreign policy matters. Based in the White House, it is part of the Exe ...

would list "yankeephobia" as a key challenge to U.S. interests in Latin America.

See also

* Eva Perón's "Rainbow Tour" *History of Venezuela (1948–58)

A military dictatorship ruled Venezuela for ten years, from 1948 to 1958. After the 1948 Venezuelan coup d'état brought an end a three-year experiment in democracy ("El Trienio Adeco"), a triumvirate of military personnel controlled the gover ...

Notes

References

{{Richard Nixon Anti-Americanism Richard Nixon 20th century in Caracas 1958 in the United States 1958 in Venezuela Riots and civil disorder in Venezuela United States Secret Service April 1958 events in South America United States–Venezuela relations Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower 1958 riots