Assyrian genocide on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Sayfo or the Seyfo (; see below), also known as the Assyrian genocide, was the mass slaughter and

The Sayfo or the Seyfo (; see below), also known as the Assyrian genocide, was the mass slaughter and

In its

In its

Although the Kurds and Assyrians were well-integrated with each other, Gaunt writes that this integration "led straight into a world marked by violence, raiding, the kidnapping and rape of women, hostage taking, cattle stealing, robbery, plundering, the torching of villages and a state of chronic unrest". Assyrian efforts to maintain their autonomy collided with the Ottoman Empire's nineteenth-century attempts at centralization and modernization to assert control over what had effectively been a stateless region. The first mass violence targeting Assyrians was in the mid-1840s, when Kurdish emir Badr Khan devastated Hakkari and Tur Abdin, killing several thousands. During intertribal feuds, the bulk of the violence was directed at Christian villages under the protection of the opposing tribe.

During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, the Ottoman state armed the Kurds with modern weapons to fight Russia. When the Kurds refused to return the weapons at the end of the war, Assyrians—relying on older weapons—were at a disadvantage and subject to increasing violence. The irregular Hamidiye cavalry were formed in the 1880s from Kurdish tribes loyal to the government; their exemption from civil and military law enabled them to commit acts of violence with impunity. The rise of

Although the Kurds and Assyrians were well-integrated with each other, Gaunt writes that this integration "led straight into a world marked by violence, raiding, the kidnapping and rape of women, hostage taking, cattle stealing, robbery, plundering, the torching of villages and a state of chronic unrest". Assyrian efforts to maintain their autonomy collided with the Ottoman Empire's nineteenth-century attempts at centralization and modernization to assert control over what had effectively been a stateless region. The first mass violence targeting Assyrians was in the mid-1840s, when Kurdish emir Badr Khan devastated Hakkari and Tur Abdin, killing several thousands. During intertribal feuds, the bulk of the violence was directed at Christian villages under the protection of the opposing tribe.

During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, the Ottoman state armed the Kurds with modern weapons to fight Russia. When the Kurds refused to return the weapons at the end of the war, Assyrians—relying on older weapons—were at a disadvantage and subject to increasing violence. The irregular Hamidiye cavalry were formed in the 1880s from Kurdish tribes loyal to the government; their exemption from civil and military law enabled them to commit acts of violence with impunity. The rise of

Before the war, Russia and the Ottoman Empire courted populations in each other's territory to wage guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines. The Ottoman Empire tried to enlist

Before the war, Russia and the Ottoman Empire courted populations in each other's territory to wage guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines. The Ottoman Empire tried to enlist

In May, Assyrian warriors were part of the Russian force which was rushed to relieve the defense of Van; Haydar Bey, the governor of Mosul, was given the power to invade Hakkari. Talaat ordered him to drive the Assyrians out and added, "We should not let them return to their homelands". The ethnic-cleansing operation was coordinated by Enver, Talaat, and military and civilian Ottoman authorities. To legalize the invasion, the districts of Julamerk, Gawar, and Shemdinan were temporarily transferred to Mosul province. The Ottoman army joined local Kurdish tribes against specific targets. Suto Agha of the Kurdish Oramar tribe attacked

In May, Assyrian warriors were part of the Russian force which was rushed to relieve the defense of Van; Haydar Bey, the governor of Mosul, was given the power to invade Hakkari. Talaat ordered him to drive the Assyrians out and added, "We should not let them return to their homelands". The ethnic-cleansing operation was coordinated by Enver, Talaat, and military and civilian Ottoman authorities. To legalize the invasion, the districts of Julamerk, Gawar, and Shemdinan were temporarily transferred to Mosul province. The Ottoman army joined local Kurdish tribes against specific targets. Suto Agha of the Kurdish Oramar tribe attacked

In 1903, Russia estimated that 31,700 Assyrians lived in Persia. Facing attacks from their Kurdish neighbors, the Assyrian villages in the Ottoman–Persian borderlands organized self-defense forces; by the outbreak of World War I, they were well armed. In 1914, before the declaration of war against Russia, Ottoman forces crossed the border into Persia and destroyed Christian villages. Large-scale attacks in late September and October 1914 targeted many Assyrian villages, and the attackers neared Urmia. Due to Ottoman attacks, thousands of Christians living along the border fled to Urmia. Others arrived in Persia after fleeing from the Ottoman side of the border. The November 1914 proclamation of jihad by the Ottoman government inflamed jihadist sentiments in the Ottoman–Persian border area, convincing the local Kurdish population to side with the Ottomans. In November, Persia declared its neutrality; however, it was not respected by the warring parties.

Russia organized units of Assyrian and Armenian volunteers to bolster local Russian forces against Ottoman attack. Assyrians led by Agha Petros declared their support for the Entente, and marched in Urmia. Agha Petros later said that he had been promised by Russian officials that in exchange for their support, they would receive an independent state after the war. Ottoman irregulars in Van province crossed the Persian border, attacking Christian villages in Persia. In response, Persia shut down the Ottoman consulates in

In 1903, Russia estimated that 31,700 Assyrians lived in Persia. Facing attacks from their Kurdish neighbors, the Assyrian villages in the Ottoman–Persian borderlands organized self-defense forces; by the outbreak of World War I, they were well armed. In 1914, before the declaration of war against Russia, Ottoman forces crossed the border into Persia and destroyed Christian villages. Large-scale attacks in late September and October 1914 targeted many Assyrian villages, and the attackers neared Urmia. Due to Ottoman attacks, thousands of Christians living along the border fled to Urmia. Others arrived in Persia after fleeing from the Ottoman side of the border. The November 1914 proclamation of jihad by the Ottoman government inflamed jihadist sentiments in the Ottoman–Persian border area, convincing the local Kurdish population to side with the Ottomans. In November, Persia declared its neutrality; however, it was not respected by the warring parties.

Russia organized units of Assyrian and Armenian volunteers to bolster local Russian forces against Ottoman attack. Assyrians led by Agha Petros declared their support for the Entente, and marched in Urmia. Agha Petros later said that he had been promised by Russian officials that in exchange for their support, they would receive an independent state after the war. Ottoman irregulars in Van province crossed the Persian border, attacking Christian villages in Persia. In response, Persia shut down the Ottoman consulates in

Ottoman troops began attacking Christian villages during their February 1915 retreat, when they were turned back by a Russian counterattack. Facing losses which they blamed on Armenian volunteers and imagining a broad Armenian rebellion, Djevdet ordered massacres of Christian civilians to reduce the potential future strength of volunteer units. Some local Kurdish tribes participated in the killings, but others protected Christian civilians. Some Assyrian villages also engaged in armed resistance when attacked. The Persian Ministry of Foreign Affairs protested the atrocities to the Ottoman government, but lacked the power to prevent them.

Many Christians did not have time to flee during the Russian withdrawal, and 20,000 to 25,000 refugees were stranded in Urmia. Nearly 18,000 Christians sought shelter in the city's Presbyterian and Lazarist missions. Although there was reluctance to attack the missionary compounds, many died of disease. Between February and May (when the Ottoman forces pulled out), there was a campaign of mass execution, looting, kidnapping, and extortion against Christians in Urmia. More than 100 men were arrested at the Lazarist compound, and dozens (including Mar Dinkha, bishop of Tergawer) were executed on 23 and 24 February. Near Urmia, the large Syriac village of Gulpashan was attacked; men were killed, and women and children were abducted and raped.

There were no missionaries in the Salmas valley to protect Christians, although some local Muslims tried to do so. In Dilman, the Persian governor offered shelter to 400 Christians; he was forced to surrender the men to Ottoman forces, however, who executed them in the town square. The Ottoman forces lured Christians to

Ottoman troops began attacking Christian villages during their February 1915 retreat, when they were turned back by a Russian counterattack. Facing losses which they blamed on Armenian volunteers and imagining a broad Armenian rebellion, Djevdet ordered massacres of Christian civilians to reduce the potential future strength of volunteer units. Some local Kurdish tribes participated in the killings, but others protected Christian civilians. Some Assyrian villages also engaged in armed resistance when attacked. The Persian Ministry of Foreign Affairs protested the atrocities to the Ottoman government, but lacked the power to prevent them.

Many Christians did not have time to flee during the Russian withdrawal, and 20,000 to 25,000 refugees were stranded in Urmia. Nearly 18,000 Christians sought shelter in the city's Presbyterian and Lazarist missions. Although there was reluctance to attack the missionary compounds, many died of disease. Between February and May (when the Ottoman forces pulled out), there was a campaign of mass execution, looting, kidnapping, and extortion against Christians in Urmia. More than 100 men were arrested at the Lazarist compound, and dozens (including Mar Dinkha, bishop of Tergawer) were executed on 23 and 24 February. Near Urmia, the large Syriac village of Gulpashan was attacked; men were killed, and women and children were abducted and raped.

There were no missionaries in the Salmas valley to protect Christians, although some local Muslims tried to do so. In Dilman, the Persian governor offered shelter to 400 Christians; he was forced to surrender the men to Ottoman forces, however, who executed them in the town square. The Ottoman forces lured Christians to

Before the war, Siirt and the surrounding area were Christian enclaves populated largely by Chaldean Catholics. Catholic priest estimated that there were 60,000 Christians living in the Siirt district (

Before the war, Siirt and the surrounding area were Christian enclaves populated largely by Chaldean Catholics. Catholic priest estimated that there were 60,000 Christians living in the Siirt district (

Christians in Mardin were largely untouched until May 1915. At the end of May, they heard about the abduction of Christian women and the murder of wealthy Christians elsewhere in Diyarbekir to steal their property. Extortion and violence began in Mardin district, despite the efforts of district governor Hilmi Bey. Hilmi rejected Reshid's demands to arrest Christians in Mardin, saying that they posed no threat to the state. Reshid sent Pirinççizâde Aziz Feyzi to incite anti-Christian violence in April and May, and Feyzi bribed or persuaded the Deşi, Mışkiye, Kiki and Helecan chieftains to join him. Mardin police chief Memduh Bey arrested dozens of men in early June, using torture to extract confessions of treason and disloyalty and extorting money from their families. Reshid appointed a new mayor and officials in Mardin, who organized a 500-man militia to kill. He also urged the central government to depose Hilmi, which it did on 8 June. He was replaced by the equally-resistant Shefik, whom Reshid also tried to depose. The cooperative Ibrahim Bedri was appointed as an official and Reshid used him to carry out his orders, bypassing Shefik. Reshid also replaced Midyat governor Nuri Bey with the hardline Edib Bey in July 1915, after Nuri refused to cooperate with Reshid.

On the night of 26 May, militiamen were caught attempting to plant arms in a Syriac Catholic church in Mardin. Their intent was to cite the supposed discovery of an arms cache as evidence of a Christian rebellion to justify the planned massacres. Mardin's well-to-do Christians were deported in convoys, the first of which left the city on 10 June. Those who refused to convert to Islam were murdered on the road to Diyarbekir. Half of the second convoy, which departed on 12 June, had been massacred before messengers from Diyarbekir announced that the non-Armenians had been pardoned by the sultan; they were subsequently freed. Other convoys from Mardin were targeted for extermination from late June until October. The city's Syriac Orthodox made a deal with authorities and were spared, but the other Christian denominations were decimated.

All Christian denominations were treated the same in the Mardin district countryside. Militia and Kurds attacked the village of Tell Ermen on 1 July, killing men, women, and children indiscriminately in the church after raping the women. The next day, more than 1,000 Syriac Orthodox and Catholics were massacred in Eqsor by militia and Kurds from the Milli, Deşi, Mişkiye, and Helecan tribes. Looting continued for several days before the village was burned down (which could be seen from Mardin). In

Christians in Mardin were largely untouched until May 1915. At the end of May, they heard about the abduction of Christian women and the murder of wealthy Christians elsewhere in Diyarbekir to steal their property. Extortion and violence began in Mardin district, despite the efforts of district governor Hilmi Bey. Hilmi rejected Reshid's demands to arrest Christians in Mardin, saying that they posed no threat to the state. Reshid sent Pirinççizâde Aziz Feyzi to incite anti-Christian violence in April and May, and Feyzi bribed or persuaded the Deşi, Mışkiye, Kiki and Helecan chieftains to join him. Mardin police chief Memduh Bey arrested dozens of men in early June, using torture to extract confessions of treason and disloyalty and extorting money from their families. Reshid appointed a new mayor and officials in Mardin, who organized a 500-man militia to kill. He also urged the central government to depose Hilmi, which it did on 8 June. He was replaced by the equally-resistant Shefik, whom Reshid also tried to depose. The cooperative Ibrahim Bedri was appointed as an official and Reshid used him to carry out his orders, bypassing Shefik. Reshid also replaced Midyat governor Nuri Bey with the hardline Edib Bey in July 1915, after Nuri refused to cooperate with Reshid.

On the night of 26 May, militiamen were caught attempting to plant arms in a Syriac Catholic church in Mardin. Their intent was to cite the supposed discovery of an arms cache as evidence of a Christian rebellion to justify the planned massacres. Mardin's well-to-do Christians were deported in convoys, the first of which left the city on 10 June. Those who refused to convert to Islam were murdered on the road to Diyarbekir. Half of the second convoy, which departed on 12 June, had been massacred before messengers from Diyarbekir announced that the non-Armenians had been pardoned by the sultan; they were subsequently freed. Other convoys from Mardin were targeted for extermination from late June until October. The city's Syriac Orthodox made a deal with authorities and were spared, but the other Christian denominations were decimated.

All Christian denominations were treated the same in the Mardin district countryside. Militia and Kurds attacked the village of Tell Ermen on 1 July, killing men, women, and children indiscriminately in the church after raping the women. The next day, more than 1,000 Syriac Orthodox and Catholics were massacred in Eqsor by militia and Kurds from the Milli, Deşi, Mişkiye, and Helecan tribes. Looting continued for several days before the village was burned down (which could be seen from Mardin). In

In Tur Abdin, some Syriac Christians fought their attempted extermination. This was considered treason by Ottoman officials, who reported massacre victims as rebels. Christians in Midyat considered resistance after hearing about massacres elsewhere, but the local Syriac Orthodox community initially refused to support this. On 21 June, 100 men (mostly Armenians and Protestants) were arrested, tortured for confessions implicating others, and executed outside the city; this panicked the Syriac Orthodox. Local people refused to hand over their arms, attacked government offices, and cut

In Tur Abdin, some Syriac Christians fought their attempted extermination. This was considered treason by Ottoman officials, who reported massacre victims as rebels. Christians in Midyat considered resistance after hearing about massacres elsewhere, but the local Syriac Orthodox community initially refused to support this. On 21 June, 100 men (mostly Armenians and Protestants) were arrested, tortured for confessions implicating others, and executed outside the city; this panicked the Syriac Orthodox. Local people refused to hand over their arms, attacked government offices, and cut

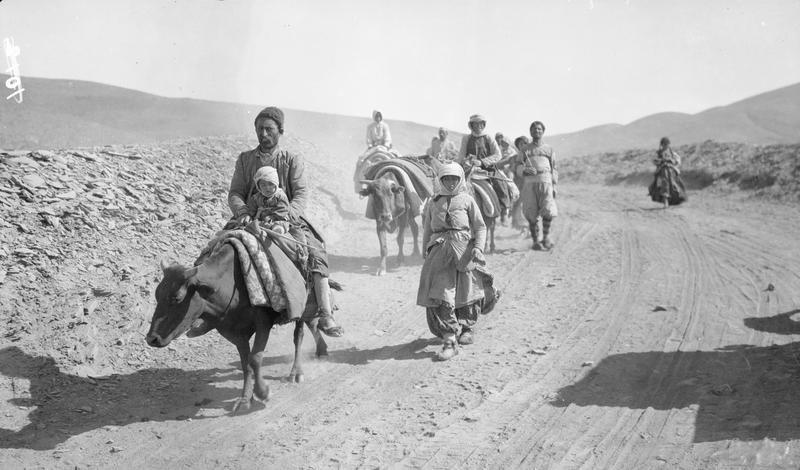

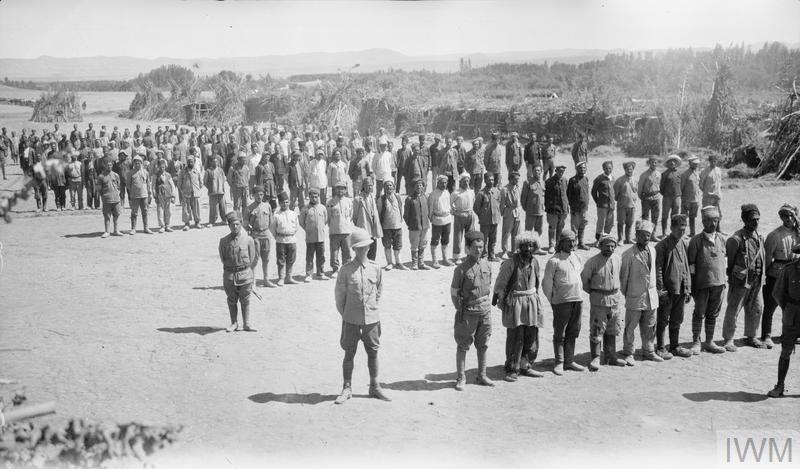

After their expulsion from Hakkari, the Assyrians and their herds were resettled by Russian occupation authorities near Khoy, Salmas and Urmia. Many died during the first winter due to lack of food, shelter, and medical care, and they were resented by local residents for worsening living standards. Assyrian men from Hakkari offered their services to the Russian military; although their knowledge of local terrain was useful, they were poorly disciplined. In 1917, Russia's withdrawal from the war after the Russian Revolution dimmed prospects of a return to Hakkari. About 5,000 Assyrian and Armenian militia policed the area, but they frequently abused their power and killed Muslims without provocation.

From February to July 1918, the region was engulfed by ethnic violence. On 22 February, local Muslims and the Persian governor began an uprising against the Christian militias in Urmia. The better-organized Christians, led by Agha Petros, brutally crushed the uprising; hundreds (possibly thousands) were killed. On 16 March, Mar Shimun and many of his bodyguards were killed by the Kurdish chieftain

After their expulsion from Hakkari, the Assyrians and their herds were resettled by Russian occupation authorities near Khoy, Salmas and Urmia. Many died during the first winter due to lack of food, shelter, and medical care, and they were resented by local residents for worsening living standards. Assyrian men from Hakkari offered their services to the Russian military; although their knowledge of local terrain was useful, they were poorly disciplined. In 1917, Russia's withdrawal from the war after the Russian Revolution dimmed prospects of a return to Hakkari. About 5,000 Assyrian and Armenian militia policed the area, but they frequently abused their power and killed Muslims without provocation.

From February to July 1918, the region was engulfed by ethnic violence. On 22 February, local Muslims and the Persian governor began an uprising against the Christian militias in Urmia. The better-organized Christians, led by Agha Petros, brutally crushed the uprising; hundreds (possibly thousands) were killed. On 16 March, Mar Shimun and many of his bodyguards were killed by the Kurdish chieftain

The Sayfo or the Seyfo (; see below), also known as the Assyrian genocide, was the mass slaughter and

The Sayfo or the Seyfo (; see below), also known as the Assyrian genocide, was the mass slaughter and deportation

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. The term ''expulsion'' is often used as a synonym for deportation, though expulsion is more often used in the context of international law, while deportation ...

of Assyrian / Syriac Christians in southeastern Anatolia and Persia's Azerbaijan province by Ottoman forces and some Kurdish tribes

The following is a list of tribes of Kurdish people, an Iranic ethnic group from the geo-cultural region of Kurdistan in Western Asia.

Iraq

Baghdad Governorate

The following tribes are present in Baghdad Governorate:

* Feyli tribe

Diyala Gover ...

during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

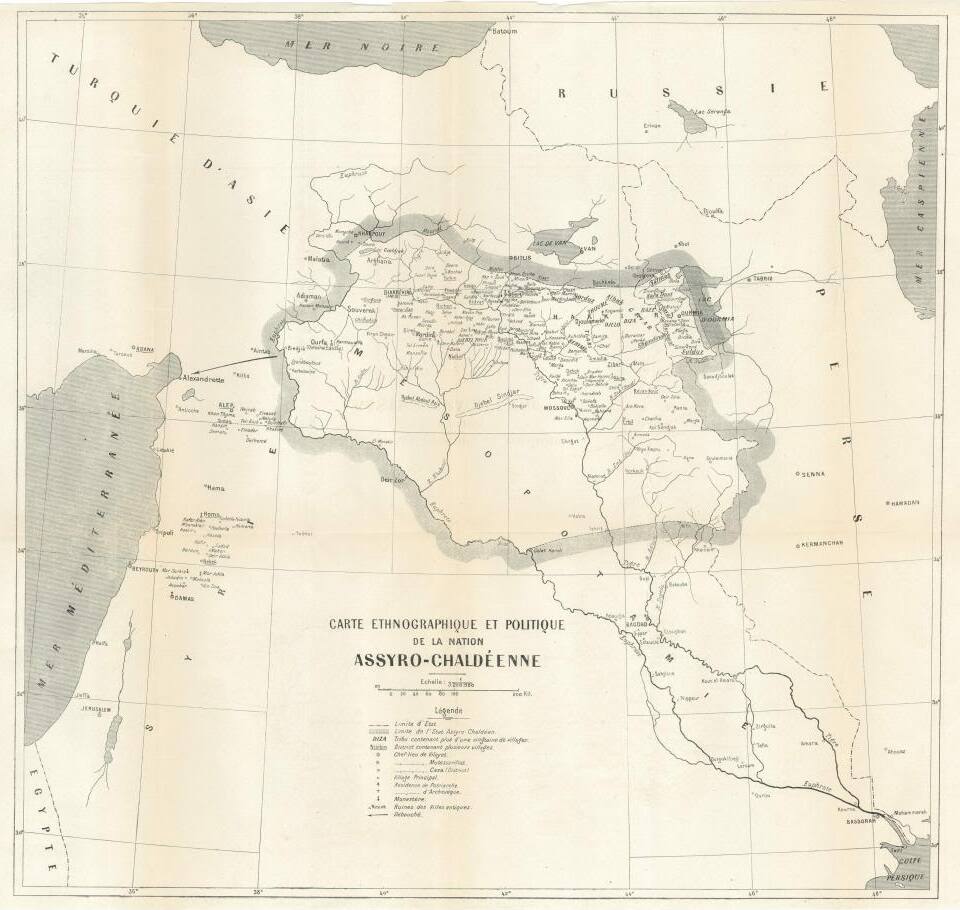

The Assyrians were divided into mutually antagonistic churches, including the Syriac Orthodox Church, the Church of the East, and the Chaldean Catholic Church. Before World War I, they lived in mountainous and remote areas of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

(some of which were effectively stateless). The empire's nineteenth-century centralization efforts led to increased violence and danger for the Assyrians.

Mass killing of Assyrian civilians began during the Ottoman occupation of Azerbaijan from January to May 1915, during which massacres were committed by Ottoman forces and pro-Ottoman Kurds. In Bitlis province, Ottoman troops returning from Persia joined local Kurdish tribes to massacre the local Christian population (including Assyrians). Ottoman forces and Kurds attacked the Assyrian tribes of Hakkari in mid-1915, driving them out by September despite the tribes mounting a coordinated military defense. Governor Mehmed Reshid

Mehmed Reshid ( tr, Mehmet Reşit Şahingiray; 8 February 1873 – 6 February 1919) was an Ottoman physician, official of the Committee of Union and Progress, and governor of the Diyarbekir Vilayet (province) of the Ottoman Empire during World ...

initiated a genocide of all of the Christian communities in Diyarbekir province, including Syriac Christians, facing only sporadic armed resistance in some parts of Tur Abdin. Ottoman Assyrians living farther south, in present-day Iraq and Syria, were not targeted in the genocide.

The Sayfo occurred concurrently with and was closely related to the Armenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was implemented primarily through t ...

, although the Sayfo is considered to have been less systematic. Local actors played a larger role than the Ottoman government

The Ottoman Empire developed over the years as a despotism with the Sultan as the supreme ruler of a centralized government that had an effective control of its provinces, officials and inhabitants. Wealth and rank could be inherited but were j ...

, but the latter also ordered attacks on certain Assyrians. Motives for killing included a perceived lack of loyalty among some Assyrian communities to the Ottoman Empire and the desire to appropriate their land. At the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, the Assyro-Chaldean delegation said that its losses were 250,000 (about half the prewar population); the accuracy of this figure is unknown. They later revised their estimate to 275,000 dead at the Lausanne Conference in 1923. The Sayfo is less studied than the Armenian genocide. Efforts to have it recognized as a genocide began during the 1990s, spearheaded by the Assyrian diaspora

Assyrian may refer to:

* Assyrian people, the indigenous ethnic group of Mesopotamia.

* Assyria, a major Mesopotamian kingdom and empire.

** Early Assyrian Period

** Old Assyrian Period

** Middle Assyrian Empire

** Neo-Assyrian Empire

* Assyrian ...

. Although several countries acknowledge that Assyrians in the Ottoman Empire were victims of a genocide, this assertion is rejected by the Turkish government.

Terminology

There is no universally accepted translation in English for the endonym ''Suryoyo'' or ''Suryoye''. The choice of which term to use, such as ''Assyrian'', ''Syriac'', '' Aramean'', and ''Chaldean'', is often determined by political alignment. The Church of the East was the first to adopt an identity derived from ancientAssyria

Assyria ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the ...

. The Syriac Orthodox Church has officially rejected the use of ''Assyrian'' since 1952, although not all Syriac Orthodox reject Assyrian identity. Since the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

was organized by religion, Ottoman officials referred to populations by their religious affiliation rather than ethnicity. Therefore, according to historian David Gaunt

David Gaunt (born 1944 in London) is a historian and professor at Södertörn University's Centre for Baltic and East European Studies and Member of Academia Europaea. Gaunt's book about the Assyrian genocide

The Sayfo or the Seyfo (; see b ...

, "speaking of an 'Assyrian Genocide' is anachronistic". In Neo-Aramaic, the languages historically spoken by Assyrians, it has been known since 1915 as ''Sayfo'' or ''Seyfo'' (, ), which, since the tenth century, has also meant 'extermination' or 'extinction'. Other terms used by some Assyrians include ''nakba

Clickable map of Mandatory Palestine with the depopulated locations during the 1947–1949 Palestine war.

The Nakba ( ar, النكبة, translit=an-Nakbah, lit=the "disaster", "catastrophe", or "cataclysm"), also known as the Palestinian Ca ...

'' (Arabic for catastrophe) and '' firman'' (Turkish for order, as Assyrians believed that they were killed according to an official decree).

Background

The people now called Assyrian, Chaldean, or Aramean are native toUpper Mesopotamia

Upper Mesopotamia is the name used for the uplands and great outwash plain of northwestern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, in the northern Middle East. Since the early Muslim conquests of the mid-7th century, the region has been ...

and historically spoke Aramaic languages

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated in ...

, and their ancestors converted to Christianity in the first centuries CE. The first major schism in Syriac Christianity dates to 410, when Christians in the Sassanid Empire (Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

) formed the Church of the East to distinguish themselves from the official religion of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

. The West Syriac church (later the Syriac Orthodox Church) was persecuted by Roman rulers for theological differences but remained separate from the Church of the East. The schisms in Syriac Christianity were fueled by political divisions between empires and personal antagonism between clergymen. Middle Eastern Christian communities were devastated by the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were ...

and the Mongol invasions. The Chaldean and Syriac Catholic Churches split from the Church of the East and the Syriac Orthodox Church, respectively, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and entered into full communion with the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. Each church considered the others heretical.

Assyrians in the Ottoman Empire

millet system

In the Ottoman Empire, a millet (; ar, مِلَّة) was an independent court of law pertaining to "personal law" under which a confessional community (a group abiding by the laws of Muslim Sharia, Christian Canon law, or Jewish Halakha) was ...

, the Ottoman Empire recognized religious denominations rather than ethnic groups: Süryaniler / Yakubiler (Syriac Orthodox or Jacobites), Nasturiler (Church of the East or Nestorian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

s), and Keldaniler (Chaldean Catholic Church). Until the nineteenth century, these groups were part of the Armenian millet The Armenian millet ( tr, Ermeni milleti) was the Ottoman millet (autonomous ethnoreligious community) of the Armenian Apostolic Church. It initially included not just Armenians in the Ottoman Empire but members of other Christian churches including ...

. Assyrians in the Ottoman Empire lived in remote, mountainous areas, where they had settled to avoid state control. Although this remoteness enabled Assyrians to avoid military conscription and taxation, it also cemented internal differences and prevented the emergence of a collective identity similar to the Armenian national movement

The Armenian national movement ( hy, Հայ ազգային-ազատագրական շարժում ''Hay azgayin-azatagrakan sharzhum'') included social, cultural, but primarily political and military movements that reached their height during Worl ...

. Unlike the Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, '' hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diasp ...

, Syriac Christians did not control a disproportionate part of Ottoman commerce and did not have significant populations in nearby hostile countries.

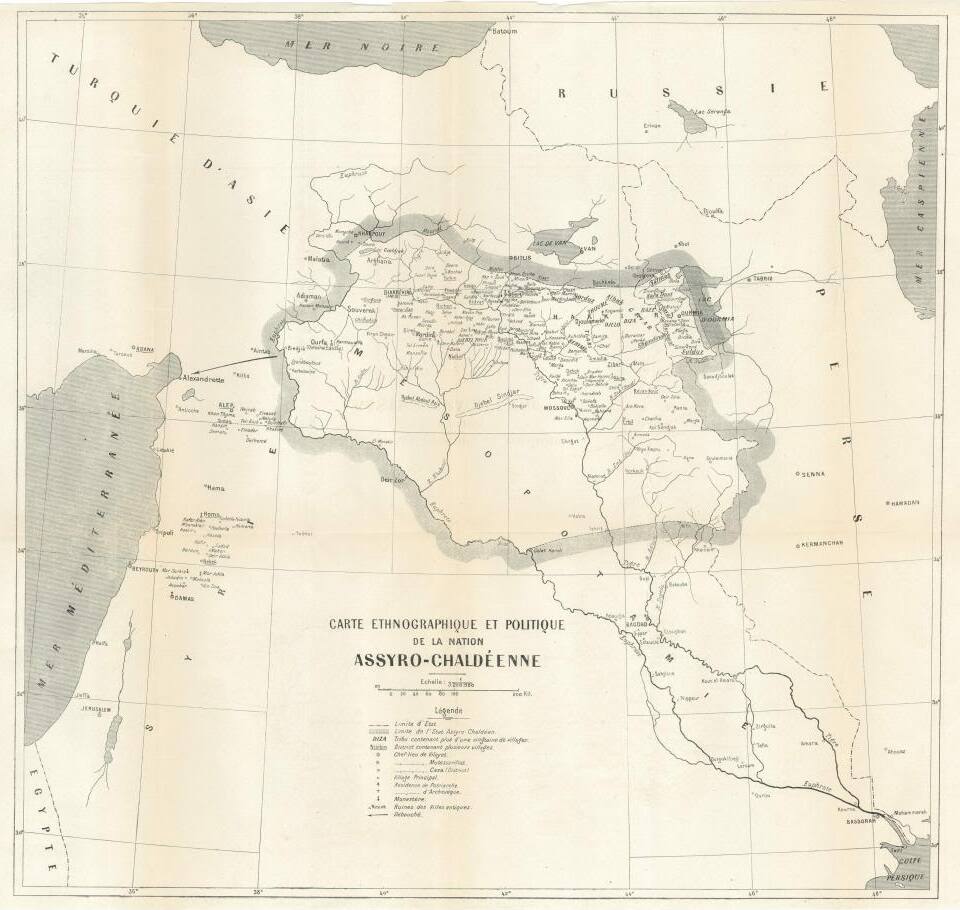

There were no accurate estimates of the prewar Assyrian population, but Gaunt gives a possible figure of 500,000 to 600,000. Midyat, in Diyarbekir province (vilayet

A vilayet ( ota, , "province"), also known by various other names, was a first-order administrative division of the later Ottoman Empire. It was introduced in the Vilayet Law of 21 January 1867, part of the Tanzimat reform movement initiated ...

), was the only town in the Ottoman Empire with an Assyrian majority (Syriac Orthodox, Chaldeans, and Protestants). Syriac Orthodox Christians were concentrated in the hilly rural areas around Midyat, known as Tur Abdin, where they lived in almost 100 villages and worked in agriculture or crafts. Syriac Orthodox culture was centered in two monasteries near Mardin (west of Tur Abdin): Mor Gabriel and Deyrulzafaran. Outside the core area of Syriac settlement, there were also sizable populations in villages and the towns of Urfa

Urfa, officially known as Şanlıurfa () and in ancient times as Edessa, is a city in southeastern Turkey and the capital of Şanlıurfa Province. Urfa is situated on a plain about 80 km east of the Euphrates River. Its climate features ex ...

, Harput

Harpoot ( tr, Harput) or Kharberd ( hy, Խարբերդ, translit=Kharberd) is an ancient town located in the Elazığ Province of Turkey. It now forms a small district of the city of Elazığ. p. 1. In the late Ottoman period, it fell under the ...

, and Adiyaman. Unlike the Syriac population of Tur Abdin, many of these Syriacs spoke non-Aramaic languages.

Under the Qudshanis

Qudshanis, "Kochanis" or "Kochanes" (officially ''Konak'', syr, ܩܘܕܫܢܝܣ, translit=Qūdšānīs , ; ku, Qoçanis, script=Latn), is a small village in the Hakkâri District of Hakkâri Province, Turkey. The village is populated by Kurds ...

-based Patriarch of the Church of the East

The Patriarch of the Church of the East (also known as Patriarch of the East, Patriarch of Babylon, the Catholicose of the East or the Grand Metropolitan of the East) is the patriarch, or leader and head bishop (sometimes referred to as Catholic ...

, Assyrian tribes controlled the Hakkari mountains east of Tur Abdin (adjacent to the Ottoman–Persian border). Hakkari is very mountainous, with peaks reaching and separated by steep gorges; many areas were only accessible by footpaths carved into the mountainsides. The Assyrian tribes sometimes fought each other on behalf of their Kurdish allies. Church of the East settlement began in the east on the western shore of Lake Urmia

Lake Urmia;

az, اۇرمۇ گؤلۆ, script=Arab, italic=no, Urmu gölü;

ku, گۆلائوو رمیەیێ, Gola Ûrmiyeyê;

hy, Ուրմիա լիճ, Urmia lich;

arc, ܝܡܬܐ ܕܐܘܪܡܝܐ is an endorheic salt lake in Iran. The lake is l ...

in Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

; a Chaldean enclave was just north, in Salamas. There was a Chaldean area around Siirt

Siirt ( ar, سِعِرْد, Siʿird; hy, Սղերդ, S'gherd; syr, ܣܥܪܬ, Siirt; ku, Sêrt) is a city in southeastern Turkey and the seat of Siirt Province. The population of the city according to the 2009 census was 129,188.

History

P ...

in Bitlis province (northeast of Tur Abdin and northwest of Hakkari, less mountainous than Hakkari), but most Chaldeans lived farther south in present-day Iraq.

Worsening conflicts

Although the Kurds and Assyrians were well-integrated with each other, Gaunt writes that this integration "led straight into a world marked by violence, raiding, the kidnapping and rape of women, hostage taking, cattle stealing, robbery, plundering, the torching of villages and a state of chronic unrest". Assyrian efforts to maintain their autonomy collided with the Ottoman Empire's nineteenth-century attempts at centralization and modernization to assert control over what had effectively been a stateless region. The first mass violence targeting Assyrians was in the mid-1840s, when Kurdish emir Badr Khan devastated Hakkari and Tur Abdin, killing several thousands. During intertribal feuds, the bulk of the violence was directed at Christian villages under the protection of the opposing tribe.

During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, the Ottoman state armed the Kurds with modern weapons to fight Russia. When the Kurds refused to return the weapons at the end of the war, Assyrians—relying on older weapons—were at a disadvantage and subject to increasing violence. The irregular Hamidiye cavalry were formed in the 1880s from Kurdish tribes loyal to the government; their exemption from civil and military law enabled them to commit acts of violence with impunity. The rise of

Although the Kurds and Assyrians were well-integrated with each other, Gaunt writes that this integration "led straight into a world marked by violence, raiding, the kidnapping and rape of women, hostage taking, cattle stealing, robbery, plundering, the torching of villages and a state of chronic unrest". Assyrian efforts to maintain their autonomy collided with the Ottoman Empire's nineteenth-century attempts at centralization and modernization to assert control over what had effectively been a stateless region. The first mass violence targeting Assyrians was in the mid-1840s, when Kurdish emir Badr Khan devastated Hakkari and Tur Abdin, killing several thousands. During intertribal feuds, the bulk of the violence was directed at Christian villages under the protection of the opposing tribe.

During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, the Ottoman state armed the Kurds with modern weapons to fight Russia. When the Kurds refused to return the weapons at the end of the war, Assyrians—relying on older weapons—were at a disadvantage and subject to increasing violence. The irregular Hamidiye cavalry were formed in the 1880s from Kurdish tribes loyal to the government; their exemption from civil and military law enabled them to commit acts of violence with impunity. The rise of political Islam

Political Islam is any interpretation of Islam as a source of political identity and action. It can refer to a wide range of individuals and/or groups who advocate the formation of state and society according to their understanding of Islamic pri ...

in the form of Kurdish shaikh

Sheikh (pronounced or ; ar, شيخ ' , mostly pronounced , plural ' )—also transliterated sheekh, sheyikh, shaykh, shayk, shekh, shaik and Shaikh, shak—is an honorific title in the Arabic language. It commonly designates a chief of a ...

s also widened the divide between the Assyrians and the Muslim Kurds. Many Assyrians were killed in the 1895 massacres of Diyarbekir. Violence worsened after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II to restore the Ottoman Consti ...

, despite Assyrian hopes that the new government would stop promoting anti-Christian Islamism. In 1908, 12,000 Assyrians were expelled from the Lizan valley by the Kurdish emir of Barwari

Barwari ( syr, ܒܪܘܪ, ku, بهرواری, Berwarî) is a region in the Hakkari mountains in northern Iraq and southeastern Turkey. The region is inhabited by Assyrians and Kurds, and was formerly also home to a number of Jews prior to the ...

. Due to increasing Kurdish attacks which Ottoman authorities did nothing to prevent, Patriarch of the Church of the East Mar Shimun XIX Benyamin

Mar Shimun XIX Benyamin (1887– 3 March 1918) ( syr, ܡܪܝ ܒܢܝܡܝܢ ܫܡܥܘܢ ܥܣܪܝܢ ܘܩܕܡܝܐ) served as the 117th Catholicos-Patriarch of the Church of the East.

Life

He was born in 1887 in the village of Qochanis in the Ha ...

began negotiations with the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

before World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

World War I

Before the war, Russia and the Ottoman Empire courted populations in each other's territory to wage guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines. The Ottoman Empire tried to enlist

Before the war, Russia and the Ottoman Empire courted populations in each other's territory to wage guerrilla warfare behind enemy lines. The Ottoman Empire tried to enlist Caucasian

Caucasian may refer to:

Anthropology

*Anything from the Caucasus region

**

**

** ''Caucasian Exarchate'' (1917–1920), an ecclesiastical exarchate of the Russian Orthodox Church in the Caucasus region

*

*

*

Languages

* Northwest Caucasian l ...

Muslims and Armenians, as well as Assyrians and Azeris

Azerbaijanis (; az, Azərbaycanlılar, ), Azeris ( az, Azərilər, ), or Azerbaijani Turks ( az, Azərbaycan Türkləri, ) are a Turkic people living mainly in northwestern Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan. They are the second-most nume ...

in Persia, and Russia looked to the Armenians, Kurds, and Assyrians living in the Ottoman Empire. Prior to the war, Russia controlled parts of northeastern Persia, including Azerbaijan and Tabriz.

Like other genocides, the Sayfo had a number of causes. The rise of nationalism led to competing Turkish, Kurdish

Kurdish may refer to:

*Kurds or Kurdish people

*Kurdish languages

*Kurdish alphabets

*Kurdistan, the land of the Kurdish people which includes:

**Southern Kurdistan

**Eastern Kurdistan

**Northern Kurdistan

**Western Kurdistan

See also

* Kurd (dis ...

, Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

, and Arab national movements, which contributed to increasing violence in the already conflict-ridden borderlands inhabited by the Assyrians. Historian Donald Bloxham

Donald Bloxham FRHistS is a Professor of Modern History, specialising in genocide, war crimes and other mass atrocities studies. He is the editor of the ''Journal of Holocaust Education''.

He completed his undergraduate studies at Keele and pos ...

emphasizes the negative influence of European powers interfering in the Ottoman Empire under the premise of protecting Ottoman Christians. This imperialism put the Ottoman Christians at risk of retaliatory attacks. In 1912 and 1913, the Ottoman loss in the Balkan Wars triggered an exodus of Muslim refugees from the Balkans. The Committee of Union and Progress

The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى جمعيتی, translit=İttihad ve Terakki Cemiyeti, script=Arab), later the Union and Progress Party ( ota, اتحاد و ترقى فرقهسی, translit=İttihad ve Tera ...

(CUP) government decided to resettle the refugees in eastern Anatolia, on land confiscated from populations deemed disloyal to the empire. There was a direct connection between the deportation of the Christian population and the resettlement of Muslims in the depopulated areas. The goals of the population replacement were to Turkify the Balkan Muslims and end the perceived internal threat from the Christian populations. With local politicians predisposed to violence against non-Muslims, these factors helped generate the preconditions for genocide.

CUP politician Enver Pasha set up the paramilitary Special Organization, which was loyal to himself. Its members, many of whom were convicted criminals released from prison for the task, operated as spies and saboteurs. The Ottoman Empire ordered a full mobilization for war on 24 July 1914, and concluded the German–Ottoman alliance

The Germany-Ottoman Alliance was ratified by the German Empire and the Ottoman Empire on August 2, 1914, shortly after the outbreak of World War I. It was created as part of a joint effort to strengthen and modernize the weak Ottoman military an ...

shortly thereafter. In August 1914, the CUP sent a delegation to an Armenian conference offering an autonomous Armenian region if the Armenian Revolutionary Federation

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation ( hy, Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցութիւն, ՀՅԴ ( classical spelling), abbr. ARF or ARF-D) also known as Dashnaktsutyun (collectively referred to as Dashnaks for short), is an Armenian ...

incited a pro-Ottoman revolt in Russia in the event of war. The Armenians refused; according to Gaunt, a similar offer was probably made to Mar Shimun in Van on 3 August. After returning to Qudshanis, Enver Pasha sent letters urging his followers to "fulfill strictly all their duties to the Turks". The Assyrians in Hakkari (like many other Ottoman subjects) resisted conscription into the Ottoman army during the mobilization, and many fled to Persia in August. Those in Mardin, however, accepted conscription.

Ethnic cleansing of Hakkari

Massacres of lowland Assyrians

In August 1914, Assyrians in nine villages near the border were forced to flee to Persia and their villages were burned after they refused to join the Ottoman army. On 26 October 1914, a few days before the Ottoman Empire entered World War I, Ottoman interior minister Talaat Pasha sent a telegram toDjevdet Bey

Jevdet Bey or Cevdet Tahir Belbez Sait Çetinoğlu"Bir Osmanlı Komutanının Soykırım Güncesi", ''Birikim'', 09.04.2009. (1878 – January 15, 1955)Selcuk Uzun"1915 „Van İsyanı“ ve Vali Cevdet (Belbez) Bey" ''Küyerel'', 30.12.2011. wa ...

, the governor of Van province

Van Province ( tr, Van ili, ku, Parezgêha Wanê, Armenian: Վանի մարզ) is a province in the Eastern Anatolian region of Turkey, between Lake Van and the Iranian border. It is 19,069 km2 in area and had a population of 1,035,418 a ...

(which included Hakkari). In a planned Ottoman attack in Persia, the loyalty of the Hakkari Assyrians was doubted. Talaat ordered the deportation and resettlement of the Assyrians who lived near the Persian border with Muslims farther west; no more than twenty Assyrians would live in each resettlement, destroying their culture, language, and traditional way of life. Gaunt cites this order as the beginning of the Sayfo. The government in Van reported that the order could not be implemented due to the lack of forces to carry it out, and by 5 November the expected Assyrian unrest did not materialize. Assyrians in Julamerk and Gawar were arrested or killed, and Ottoman irregulars attacked Assyrian villages throughout Hakkari in retaliation for their refusal to follow the order. The Assyrians, unaware of the government's role in these events until December 1914, protested to the governor of Van.

The Ottoman garrison in the border town of Bashkale was commanded by Kazim Karabekir

Kazem (also spelled Kadhem, Kadhim, Kazim, Qazim or Cathum; written in ar, كاظم, in Persian language, Persian: کاظِم) means "tolerant", "forgiving", and "having patience" is an Arabic male given name. Although the pronunciation of the ...

, and the local Special Organization branch by . Russian forces captured Bashkale and Sarai in November 1914 and held both for a few days. After their recapture by the Ottomans, the towns' local Christians were punished as collaborators, out of proportion to any actual collaboration. Local Ottoman forces consisting of gendarmerie, Hamidiye irregulars, and Kurdish volunteers were unable to mount attacks on the Assyrian tribes on the highlands, confining their attacks to poorly-armed Christian villages in the plains. Refugees from the area told the Russian army that "nearly the entire male Christian population of Gawar and Bashkale" had been massacred. In May 1915, Ottoman forces retreating from Bashkale massacred hundreds of Armenian women and children before continuing to Siirt.

Preparations for war

Mar Shimun learned about the massacre of Assyrians in lowland areas, and believed that the highland tribes would be next. ViaAgha Petros

Petros Elia of Baz ( syr, ܐܝܠܝܐ ܦܹܛܪܘܼܣ) (April 1880 – 2 February 1932), better known as Agha Petros, was an Assyrian military leader during World War I.

Early years

Petros Elia was from the Lower Baz village, Ottoman Empire in ...

, an Assyrian interpreter for the Russian consulate in Urmia, he contacted the Russian authorities. Shimun traveled to Bashkale to meet Mehmed Shefik Bey, an Ottoman official sent from Mardin to win over the Assyrians for the Ottoman cause, in December 1914. Shefik promised protection and money in exchange for a written promise that the Assyrians would not side with Russia or permit their tribes to take up arms against the Ottoman government. The tribal chiefs considered the offer, but rejected it. In January 1915, Kurds blocked the route from Qudshanis to the Assyrian tribes. The patriarch's sister, Lady Surma, left Qudshanis the following month with 300 men. Early in 1915, the tribes of Hakkari were preparing to defend themselves from a large-scale attack; they decided to send women and children to the area around Chamba in Upper Tyari, leaving only combatants behind. On 10 May, the Assyrian tribes met and declared war (or a general mobilization) against the Ottoman Empire. In June, Mar Shimun traveled to Persia to ask for Russian support. He met with General Fyodor Chernozubov in Moyanjik (in the Salmas valley), who promised support. The patriarch and Agha Petros also met Russian consul Basil Nikitin in Salmas shortly before 21 June, but the promised Russian help never materialized.

In May, Assyrian warriors were part of the Russian force which was rushed to relieve the defense of Van; Haydar Bey, the governor of Mosul, was given the power to invade Hakkari. Talaat ordered him to drive the Assyrians out and added, "We should not let them return to their homelands". The ethnic-cleansing operation was coordinated by Enver, Talaat, and military and civilian Ottoman authorities. To legalize the invasion, the districts of Julamerk, Gawar, and Shemdinan were temporarily transferred to Mosul province. The Ottoman army joined local Kurdish tribes against specific targets. Suto Agha of the Kurdish Oramar tribe attacked

In May, Assyrian warriors were part of the Russian force which was rushed to relieve the defense of Van; Haydar Bey, the governor of Mosul, was given the power to invade Hakkari. Talaat ordered him to drive the Assyrians out and added, "We should not let them return to their homelands". The ethnic-cleansing operation was coordinated by Enver, Talaat, and military and civilian Ottoman authorities. To legalize the invasion, the districts of Julamerk, Gawar, and Shemdinan were temporarily transferred to Mosul province. The Ottoman army joined local Kurdish tribes against specific targets. Suto Agha of the Kurdish Oramar tribe attacked Jilu

Jīlū was a district located in the Hakkari region of upper Mesopotamia in modern-day Turkey.

Before 1915 Jīlū was home to Assyrians and as well as a minority of Kurds. There were 20 Assyrian villages in this district. The area was tradition ...

, Dez, and Baz from the east; Said Agha attacked a valley in Lower Tyari; Ismael Agha targeted Chamba in Upper Tyari, and the Upper Berwar emir attacked Ashita, the Lizan valley, and Lower Tyari from the west.

Invasion of the highlands

The joint encirclement operation was launched on 11 June. The Jilu tribe was attacked at the beginning of the campaign by several Kurdish tribes; the fourth-century church of Mar Zaya, with historic artifacts, was destroyed. Ottoman forces based in Julamerk and Mosul launched a joint attack on Tyari on 23 June. Haydar first attacked the Tyari villages of Ashita and Sarespido; later, an expeditionary force of three thousand Turks and Kurds attacked the mountain pass between Tyari andTkhuma

Prior to World War I, the Tkhuma ( syr, ܬܚܘܡܐ, Tkhūmā "Borderland") were one of five principal and semi-independent Assyrian tribes subject to the spiritual and temporal jurisdiction of the Assyrian Patriarch with the title Mar Shimun. T ...

. Although the Assyrians were victorious in most of the battles, they had unsustainable losses of lives and ammunition and lacked their invaders' German-manufactured rifles, machine guns, and artillery. In July, Mar Shimun sent Malik Khoshaba

Malik Khoshaba Yousip ( syr, ܡܠܟ ܚܕܒܫܒܐ ܝܘܣܦ) was an Assyrian tribal leader (or "malik") of the Tyari tribe (''Bit Tyareh'') who played a significant role in the Assyrian independence movement during World War I.

Early life

Malik Kho ...

and bishop Mar Yalda Yahwallah from Barwari to Tabriz

Tabriz ( fa, تبریز ; ) is a city in northwestern Iran, serving as the capital of East Azerbaijan Province. It is the List of largest cities of Iran, sixth-most-populous city in Iran. In the Quri Chay, Quru River valley in Iran's historic Aze ...

in Persia to request urgent assistance from the Russians. The Kurdish Barzani tribe assisted the Ottoman army and laid waste to Tkhuma, Tyari, Jilu, and Baz. During the campaign, Ottoman forces took no prisoners. Mar Shimun's brother, Hormuz, was arrested while he was studying in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

; in late June, Talaat tried to obtain the surrender of the Assyrian tribes by threatening Hormuz' life if Mar Shimun did not capitulate. The Assyrians refused, and he was killed.

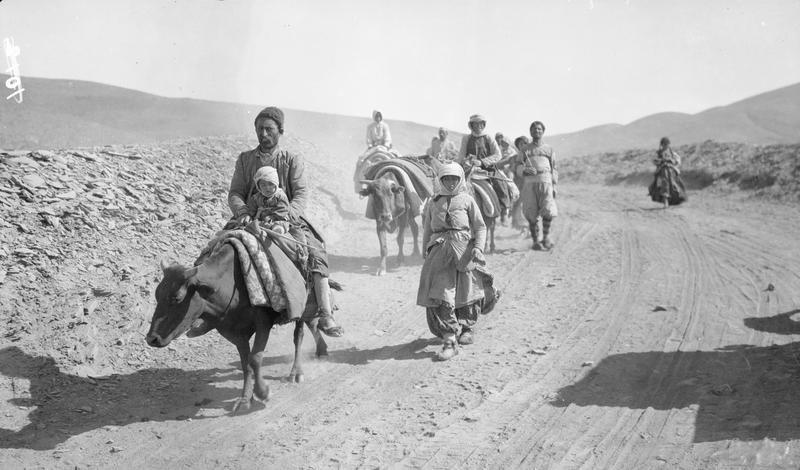

Outnumbered and outgunned, the Assyrians retreated further into the high mountains without food and watched as their homes, farms, and herds were pillaged. They had no other option but fleeing to Persia, which most had done by September. Most of the men joined the Russian army, hoping to return home. During the 1915 fighting, the Assyrians' only strategic objective was defensive; the Ottoman goal was to defeat the Assyrian tribes and prevent their return.

Ottoman occupation of Azerbaijan

In 1903, Russia estimated that 31,700 Assyrians lived in Persia. Facing attacks from their Kurdish neighbors, the Assyrian villages in the Ottoman–Persian borderlands organized self-defense forces; by the outbreak of World War I, they were well armed. In 1914, before the declaration of war against Russia, Ottoman forces crossed the border into Persia and destroyed Christian villages. Large-scale attacks in late September and October 1914 targeted many Assyrian villages, and the attackers neared Urmia. Due to Ottoman attacks, thousands of Christians living along the border fled to Urmia. Others arrived in Persia after fleeing from the Ottoman side of the border. The November 1914 proclamation of jihad by the Ottoman government inflamed jihadist sentiments in the Ottoman–Persian border area, convincing the local Kurdish population to side with the Ottomans. In November, Persia declared its neutrality; however, it was not respected by the warring parties.

Russia organized units of Assyrian and Armenian volunteers to bolster local Russian forces against Ottoman attack. Assyrians led by Agha Petros declared their support for the Entente, and marched in Urmia. Agha Petros later said that he had been promised by Russian officials that in exchange for their support, they would receive an independent state after the war. Ottoman irregulars in Van province crossed the Persian border, attacking Christian villages in Persia. In response, Persia shut down the Ottoman consulates in

In 1903, Russia estimated that 31,700 Assyrians lived in Persia. Facing attacks from their Kurdish neighbors, the Assyrian villages in the Ottoman–Persian borderlands organized self-defense forces; by the outbreak of World War I, they were well armed. In 1914, before the declaration of war against Russia, Ottoman forces crossed the border into Persia and destroyed Christian villages. Large-scale attacks in late September and October 1914 targeted many Assyrian villages, and the attackers neared Urmia. Due to Ottoman attacks, thousands of Christians living along the border fled to Urmia. Others arrived in Persia after fleeing from the Ottoman side of the border. The November 1914 proclamation of jihad by the Ottoman government inflamed jihadist sentiments in the Ottoman–Persian border area, convincing the local Kurdish population to side with the Ottomans. In November, Persia declared its neutrality; however, it was not respected by the warring parties.

Russia organized units of Assyrian and Armenian volunteers to bolster local Russian forces against Ottoman attack. Assyrians led by Agha Petros declared their support for the Entente, and marched in Urmia. Agha Petros later said that he had been promised by Russian officials that in exchange for their support, they would receive an independent state after the war. Ottoman irregulars in Van province crossed the Persian border, attacking Christian villages in Persia. In response, Persia shut down the Ottoman consulates in Khoy

Khoy (Persian and az, خوی; ; ; also Romanized as Khoi), is a city and capital of Khoy County, West Azerbaijan Province, Iran. At the 2012 census, its population was 200,985.

Khoy is located north of the province's capital and largest city ...

, Tabriz, and Urmia and expelled Sunni Muslims. Ottoman authorities retaliated with the expulsion of several thousand Hakkari Assyrians to Persia. Resettled in farming villages, the Assyrians were armed by Russia. The Russian government was aware that the Assyrians and Armenians of Azerbaijan could not stop an Ottoman army, and was indifferent to the danger to which these communities would be exposed in an Ottoman invasion.

On 1 January 1915, Russia abruptly withdrew its forces. Ottoman forces led by Djevdet, Kazim Karabekir, and Ömer Naji occupied Azerbaijan with no opposition. Immediately after the withdrawal of Russian forces, local Muslims committed pogroms against Christians; the Ottoman army also attacked Christian civilians. Over a dozen villages were sacked and, of the large villages, only Gulpashan was left intact. News of the atrocities spread quickly, leading many Armenians and Assyrians to flee to the Russian Caucasus; those north of Urmia had more time to flee. According to several estimates, about 10,000 or 15,000 to 20,000 crossed the border into Russia. Assyrians who had volunteered for the Russian forces were separated from their families, who were often left behind. An estimated 15,000 Ottoman troops reached Urmia by 4 or 5 January, and Dilman on 8 January.

Massacres

Ottoman troops began attacking Christian villages during their February 1915 retreat, when they were turned back by a Russian counterattack. Facing losses which they blamed on Armenian volunteers and imagining a broad Armenian rebellion, Djevdet ordered massacres of Christian civilians to reduce the potential future strength of volunteer units. Some local Kurdish tribes participated in the killings, but others protected Christian civilians. Some Assyrian villages also engaged in armed resistance when attacked. The Persian Ministry of Foreign Affairs protested the atrocities to the Ottoman government, but lacked the power to prevent them.

Many Christians did not have time to flee during the Russian withdrawal, and 20,000 to 25,000 refugees were stranded in Urmia. Nearly 18,000 Christians sought shelter in the city's Presbyterian and Lazarist missions. Although there was reluctance to attack the missionary compounds, many died of disease. Between February and May (when the Ottoman forces pulled out), there was a campaign of mass execution, looting, kidnapping, and extortion against Christians in Urmia. More than 100 men were arrested at the Lazarist compound, and dozens (including Mar Dinkha, bishop of Tergawer) were executed on 23 and 24 February. Near Urmia, the large Syriac village of Gulpashan was attacked; men were killed, and women and children were abducted and raped.

There were no missionaries in the Salmas valley to protect Christians, although some local Muslims tried to do so. In Dilman, the Persian governor offered shelter to 400 Christians; he was forced to surrender the men to Ottoman forces, however, who executed them in the town square. The Ottoman forces lured Christians to

Ottoman troops began attacking Christian villages during their February 1915 retreat, when they were turned back by a Russian counterattack. Facing losses which they blamed on Armenian volunteers and imagining a broad Armenian rebellion, Djevdet ordered massacres of Christian civilians to reduce the potential future strength of volunteer units. Some local Kurdish tribes participated in the killings, but others protected Christian civilians. Some Assyrian villages also engaged in armed resistance when attacked. The Persian Ministry of Foreign Affairs protested the atrocities to the Ottoman government, but lacked the power to prevent them.

Many Christians did not have time to flee during the Russian withdrawal, and 20,000 to 25,000 refugees were stranded in Urmia. Nearly 18,000 Christians sought shelter in the city's Presbyterian and Lazarist missions. Although there was reluctance to attack the missionary compounds, many died of disease. Between February and May (when the Ottoman forces pulled out), there was a campaign of mass execution, looting, kidnapping, and extortion against Christians in Urmia. More than 100 men were arrested at the Lazarist compound, and dozens (including Mar Dinkha, bishop of Tergawer) were executed on 23 and 24 February. Near Urmia, the large Syriac village of Gulpashan was attacked; men were killed, and women and children were abducted and raped.

There were no missionaries in the Salmas valley to protect Christians, although some local Muslims tried to do so. In Dilman, the Persian governor offered shelter to 400 Christians; he was forced to surrender the men to Ottoman forces, however, who executed them in the town square. The Ottoman forces lured Christians to Haftevan

, native_name_lang = fa

, settlement_type = Village

, image_skyline = St. George Church, Haftvan 03.jpg

, imagesize =

, image_alt =

, image_caption = St. George Church, a 13th c ...

(a village south of Dilman) by demanding that they register there, and arrested notable people in Dilman who were brought to the village for execution. Over two days in February, 700 to 800 people (including the entire male Christian population) was murdered in Haftevan. The killings were committed by the Ottoman army (led by Djevdet) and the local Shekak Kurdish tribe, led by Simko Shikak

Simko Shikak. Birth name: Ismail Agha Shikak. born 1887, was a Kurdish chieftain of the Shekak tribe. He was born into a prominent Kurdish feudal family based in Chihriq castle located near the Baranduz river in the Urmia region of northwestern ...

.

In April, Ottoman army commander Halil Pasha arrived in Azerbaijan with reinforcements from Rowanduz

Rawandiz ( ar, رواندز; ku, ڕەواندز, Rewandiz) is a city in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, located in the Erbil Governorate, close to the borders with Iran and Turkey, it is located 10 km to the east from Bekhal Waterfall. The d ...

. Halil and Djevdet ordered the murder of Armenian and Syriac soldiers serving in the Ottoman army, and several hundred were killed. In several other massacres in Azerbaijan in early 1915, hundreds of Christians were killed and women were targeted for kidnapping and rape; seventy villages were destroyed. In May and June, Christians who had fled to the Caucasus returned to find their villages destroyed. Armenian and Assyrian volunteers attacked Muslims in revenge. After retreating from Persia, Ottoman forces—blaming Armenians and Assyrians for their defeat—took revenge against Ottoman Christians. Ottoman atrocities in Persia were widely covered by international media in mid-March 1915, prompting a declaration

Declaration may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''Declaration'' (book), a self-published electronic pamphlet by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri

* ''The Declaration'' (novel), a 2008 children's novel by Gemma Malley

Music ...

on 24 May by Russia, France, and the United Kingdom condemning them. The Blue Book

A blue book or bluebook is an almanac, buyer's guide or other compilation of statistics and information. The term dates back to the 15th century, when large blue velvet-covered books were used for record-keeping by the Parliament of England. The ...

, a collection of eyewitness reports of Ottoman atrocities published by the British government in 1916, devoted 104 of its 684 pages to the Assyrians.

Butcher battalion in Bitlis

A Kurdish rebellion in Bitlis province was suppressed shortly before the outbreak of war in November 1914. The CUP government reversed its previous opposition to the Hamidiye regiments, recruiting them to put down the rebellion. As elsewhere, military requisitions became pillage; in February, labor-battalion recruits began to disappear. In July and August 1915, 2,000 Chaldeans and Syriac Orthodox from Bitlis were among those who fled to the Caucasus when the Russian army retreated from Van. Before the war, Siirt and the surrounding area were Christian enclaves populated largely by Chaldean Catholics. Catholic priest estimated that there were 60,000 Christians living in the Siirt district (

Before the war, Siirt and the surrounding area were Christian enclaves populated largely by Chaldean Catholics. Catholic priest estimated that there were 60,000 Christians living in the Siirt district (sanjak

Sanjaks (liwāʾ) (plural form: alwiyāʾ)

* Armenian: նահանգ (''nahang''; meaning "province")

* Bulgarian: окръг (''okrǔg''; meaning "county", "province", or "region")

* el, Διοίκησις (''dioikēsis'', meaning "province" ...

), including 15,000 Chaldeans and 20,000 Syriac Orthodox. Violence in Siirt began on 9 June with the arrest and execution of Armenian, Syriac Orthodox, and Chaldean clerics and notable residents, including the Chaldean bishop Addai Sher. After retreating from Persia, Djevdet led the siege of Van; he continued to Bitlis province in June with 8,000 soldiers, whom he called the "butcher battalion" ( tr, kassablar taburu). The arrival of these troops in Siirt led to more violence. District governor (mutasarrif

Mutasarrif or mutesarrif ( ota, متصرّف, tr, mutasarrıf) was the title used in the Ottoman Empire and places like post-Ottoman Iraq for the governor of an administrative district. The Ottoman rank of mutasarrif was established as part of a ...

) Serfiçeli Hilmi Bey and Siirt mayor Abdul Ressak were replaced because they did not support the killing. Forty local officials in Siirt organized the massacres.

During the month-long massacre, Christians were killed in the streets or their houses (which were looted). The Chaldean diocese of Siirt was destroyed, including its library of rare manuscripts. The massacre was organized by Bitlis governor Abdülhalik Renda, the chief of police, the mayor, and other prominent local residents. The killing in Siirt was committed by '' çetes'', and the surrounding villages were destroyed by Kurds; many local Kurdish tribes were involved. According to Venezuelan mercenary Rafael de Nogales

Rafael Inchauspe Méndez, known as Rafael de Nogales Méndez (October 14, 1877 in San Cristóbal, Táchira – July 10, 1937 in Panama City) was a Venezuelan soldier, adventurer and writer who served the Ottoman Empire during the World War I, Gr ...

, the massacre was planned as revenge for Ottoman defeats by Russia. De Nogales believed that Halil was trying to assassinate him, since the CUP had disposed of other witnesses. He left Siirt as quickly as he could, passing deportation columns of Syriac and Armenian women and children.

Only 400 people were deported from Siirt; the remainder were killed or kidnapped by Muslims. The deportees (women and children, since the men had been executed) were forced to march west from Siirt towards Mardin or south towards Mosul, assaulted by police. As they passed through, their possessions (including their clothes) were stolen by local Kurds and Turks. Those unable to keep up were killed, and women considered attractive were abducted by police or Kurds, raped, and killed. One site of attacks and robbery by Kurds was the gorge of Wadi Wawela in Sawro kaza

A kaza (, , , plural: , , ; ota, قضا, script=Arab, (; meaning 'borough')

* bg, околия (; meaning 'district'); also Кааза

* el, υποδιοίκησις () or (, which means 'borough' or 'municipality'); also ()

* lad, kaza

, ...

, northeast of Mardin. No deportees reached Mardin, and only 50 to 100 Chaldeans (of an original 7,000 to 8,000) reached Mosul. Three Assyrian villages in Siirt—Dentas, Piroze and Hertevin—survived the Sayfo, existing until 1968 when their residents emigrated.

After leaving Siirt, Djevdet proceeded to Bitlis

Bitlis ( hy, Բաղեշ '; ku, Bidlîs; ota, بتليس) is a city in southeastern Turkey and the capital of Bitlis Province. The city is located at an elevation of 1,545 metres, 15 km from Lake Van, in the steep-sided valley of the Bitlis R ...

and arrived on 25 June. His forces killed men, and the women and girls were enslaved by Turks and Kurds. The Syriac Orthodox Church estimated its Bitlis province losses at 8,500, primarily in Schirwan and Gharzan.

Diyarbekir

The situation for Christians in Diyarbekir province worsened during the winter of 1914–1915; the Saint Ephraim church was vandalized, and four young men from the Syriac village of Qarabash (near Diyarbekir) were hanged for desertion. Syriacs who protested the executions were clubbed by police, and two died. In March, many non-Muslim soldiers were disarmed and transferred to road-building labor battalions. Harsh conditions, mistreatment, and individual murders led to many deaths. On 25 March, CUP founding memberMehmed Reshid

Mehmed Reshid ( tr, Mehmet Reşit Şahingiray; 8 February 1873 – 6 February 1919) was an Ottoman physician, official of the Committee of Union and Progress, and governor of the Diyarbekir Vilayet (province) of the Ottoman Empire during World ...

was appointed governor of Diyarbekir. Chosen for his record of anti-Armenian violence, Reshid brought thirty Special Organization members (mainly Circassians

The Circassians (also referred to as Cherkess or Adyghe; Adyghe and Kabardian: Адыгэхэр, romanized: ''Adıgəxər'') are an indigenous Northwest Caucasian ethnic group and nation native to the historical country-region of Circassia ...

) who were joined by released convicts. Many local officials (kaymakam

Kaymakam, also known by many other romanizations, was a title used by various officials of the Ottoman Empire, including acting grand viziers, governors of provincial sanjaks, and administrators of district kazas. The title has been retained a ...

s and district governors) refused to follow Reshid's orders, and were replaced in May and June 1915. Kurdish confederations were offered rewards to allow their Syriac clients to be killed. Government allies complied (including the Milli

''Milli'' (symbol m) is a unit prefix in the metric system denoting a factor of one thousandth (10−3). Proposed in 1793, and adopted in 1795, the prefix comes from the Latin , meaning ''one thousand'' (the Latin plural is ). Since 1960, the pre ...

and Dekşuri), and many who had supported the anti-CUP 1914 Bedirhan revolt switched sides because the extermination of Christians did not threaten their interests. The Raman tribe

Raman may refer to:

People

*Raman (name)

*C. V. Raman (1888–1970), Indian Nobel Prize-winning physicist

Places

* Raman, Punjab (India)

* Raman, Rawalpindi, Pakistan

* Raman District, Yala Province, Thailand

** Raman Railway Station

* Raman oi ...

became enthusiastic executioners for Reshid, but parts of the Heverkan leadership protected Christians; this limited Reshid's genocide, and allowed pockets of resistance to survive in Tur Abdin. Some Yazidis

Yazidis or Yezidis (; ku, ئێزیدی, translit=Êzidî) are a Kurmanji-speaking endogamous minority group who are indigenous to Kurdistan, a geographical region in Western Asia that includes parts of Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Iran. The ma ...

, who were also persecuted by the government, aided the Christians. The killers in Diyarbekir were typically volunteers organized by local leaders, and the freelance perpetrators took a share of the loot. Some women and children were abducted into local Kurdish or Arab families.

Thousands of Armenians and several hundred Syriacs (including all their clergymen) in Diyarbekir city were arrested, deported, and massacred in June. In the Viranşehir

Viranşehir ( ku, Wêranşar) is a market town serving a cotton-growing area of Şanlıurfa Province, in southeastern Turkey, 93 km east of the city Şanlıurfa and 53 km north-west of Ceylanpınar at the Syrian border. In Late Antiquit ...

kaza, west of Mardin, its Armenians were massacred in late May and June 1915. Syriacs were not killed, but many lost their property and some were deported to Mardin in August. In total, 178 Syriac towns and villages near Diyarbekir were wiped out and most of them razed.

Targeting of non-Armenian Christians

Under Reshid's leadership, a systematic anti-Christian extermination was conducted in Diyarbekir province which included Syriacs and the province's fewGreek Orthodox

The term Greek Orthodox Church ( Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also cal ...

and Greek Catholics The term Greek Catholic Church can refer to a number of Eastern Catholic Churches following the Byzantine (Greek) liturgy, considered collectively or individually.

The terms Greek Catholic, Greek Catholic church or Byzantine Catholic, Byzantine Ca ...

. Reshid knew that his decision to extend the persecution to all Christians in Diyarbekir was against the central government's wishes, and he concealed relevant information from his communications. Unlike the government, Reshid and his Mardin deputy Bedri Bey classified all Aramaic-speaking Christians as Armenians: enemies of the CUP who must be eliminated. Reshid planned to replace Diyarbekir's Christians with selected, approved Muslim settlers to counterbalance the potentially-rebellious Kurds; in practice, however, the areas were resettled by Kurds and the genocide consolidated the province's Kurdish presence. Historian Uğur Ümit Üngör

Uğur Ümit Üngör (born 1980) is a Turkish scholar of genocide and mass violence.

Career

Üngör, who was born in Turkey and raised in Enschede in the Netherlands, earned a doctorate from the University of Amsterdam in 2009,Aram Arkun"Prolific ...

says that in Diyarbekir, "most instances of massacre in which the militia engaged were directly ordered by" Reshid and "all Christian communities of Diyarbekir were equally hit by the genocide, although the Armenians were often particularly singled out for immediate destruction". The priest Jacques Rhétoré estimated that the Syriac Orthodox in Diyarbekir province lost 72 percent of their population, compared to 92 percent of Armenian Catholics and 97 percent of Armenian Apostolic Church

, native_name_lang = hy

, icon = Armenian Apostolic Church logo.svg

, icon_width = 100px

, icon_alt =

, image = Էջմիածնի_Մայր_Տաճար.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, a ...

adherents.

German diplomats noticed that the Ottoman deportations were targeting groups other than Armenians, leading to a complaint from the German government. Austria–Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1 ...

and the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

also protested the violence against non-Armenians. Talaat Pasha telegraphed Reshid on 12 July 1915 that "measures adopted against the Armenians are absolutely not to be extended to other Christians... you are ordered to put an immediate end to these acts". No action was taken against Reshid for exterminating Syriac Christians or assassinating Ottoman officials who disagreed with the massacres, however, and in 1916 he was appointed governor of Ankara. Talaat's telegram may have been sent in response to German and Austrian opposition to the massacres, with no expectation of implementation. The perpetrators began separating Armenians and Syriacs in early July, only killing the former; however, the killing of Syriacs resumed in August and September.

Mardin district

Christians in Mardin were largely untouched until May 1915. At the end of May, they heard about the abduction of Christian women and the murder of wealthy Christians elsewhere in Diyarbekir to steal their property. Extortion and violence began in Mardin district, despite the efforts of district governor Hilmi Bey. Hilmi rejected Reshid's demands to arrest Christians in Mardin, saying that they posed no threat to the state. Reshid sent Pirinççizâde Aziz Feyzi to incite anti-Christian violence in April and May, and Feyzi bribed or persuaded the Deşi, Mışkiye, Kiki and Helecan chieftains to join him. Mardin police chief Memduh Bey arrested dozens of men in early June, using torture to extract confessions of treason and disloyalty and extorting money from their families. Reshid appointed a new mayor and officials in Mardin, who organized a 500-man militia to kill. He also urged the central government to depose Hilmi, which it did on 8 June. He was replaced by the equally-resistant Shefik, whom Reshid also tried to depose. The cooperative Ibrahim Bedri was appointed as an official and Reshid used him to carry out his orders, bypassing Shefik. Reshid also replaced Midyat governor Nuri Bey with the hardline Edib Bey in July 1915, after Nuri refused to cooperate with Reshid.