Arthur Seyß-Inquart on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Arthur Seyss-Inquart (German: Seyß-Inquart, ; 22 July 1892 16 October 1946) was an Austrian

Seyss-Inquart was born in 1892 in Stannern ( cs, Stonařov), a German-speaking village in the neighbourhood of the predominantly German-speaking town of

Seyss-Inquart was born in 1892 in Stannern ( cs, Stonařov), a German-speaking village in the neighbourhood of the predominantly German-speaking town of

In February 1938, Seyss-Inquart was appointed Austrian

In February 1938, Seyss-Inquart was appointed Austrian

Following the capitulation of the

Following the capitulation of the  Seyss-Inquart was an unwavering

Seyss-Inquart was an unwavering

At the

At the

Arthur Seyss-Inquart at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

* * * , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Seyss-Inquart, Arthur 1892 births 1946 deaths 20th-century Chancellors of Austria Austro-Hungarian military personnel of World War I Austrian Ministers of Defence Austrian Nazi lawyers Austrian people of Czech descent Executed Austrian Nazis Austrian people convicted of crimes against humanity Executed Austrian people Austrian Roman Catholics Chancellors of Austria Fascist rulers Foreign Ministers of Germany General Government German nationalists German people convicted of the international crime of aggression Heads of government convicted of war crimes Heads of state convicted of war crimes Holocaust perpetrators in the Netherlands Holocaust perpetrators in Poland Holocaust perpetrators in Austria Holocaust perpetrators in Germany Members of the Reichstag of Nazi Germany Moravian-German people Nazi Germany ministers Nazi Party officials Netherlands in World War II People from Jihlava District People from the Margraviate of Moravia People executed by the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg People executed for crimes against humanity SS-Obergruppenführer World War II political leaders Heads of government who were later imprisoned Christian fascists Austro-Hungarian Army officers

Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

politician who served as Chancellor of Austria

The chancellor of the Republic of Austria () is the head of government of the Republic of Austria. The position corresponds to that of Prime Minister in several other parliamentary democracies.

Current officeholder is Karl Nehammer of the Aus ...

in 1938 for two days before the ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

''. His positions in Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

included "deputy governor to Hans Frank

Hans Michael Frank (23 May 1900 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and lawyer who served as head of the General Government in Nazi-occupied Poland during the Second World War.

Frank was an early member of the German Workers' Party ...

in the General Government of Occupied Poland, and ''Reich commissioner

(, rendered as "Commissioner of the Empire", "Reich Commissioner" or "Imperial Commissioner"), in German history, was an official gubernatorial title used for various public offices during the period of the German Empire and Nazi Germany.

Germ ...

'' for the German-occupied Netherlands

Despite Dutch neutrality, Nazi Germany invaded the Netherlands on 10 May 1940 as part of Fall Gelb (Case Yellow). On 15 May 1940, one day after the bombing of Rotterdam, the Dutch forces surrendered. The Dutch government and the royal family re ...

" including shared responsibility "for the deportation of Dutch Jews and the shooting of hostages".

During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Seyss-Inquart fought for the Austro-Hungarian Army

The Austro-Hungarian Army (, literally "Ground Forces of the Austro-Hungarians"; , literally "Imperial and Royal Army") was the ground force of the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy from 1867 to 1918. It was composed of three parts: the joint arm ...

with distinction. After the war he became a successful lawyer, and went on to join the governments of Chancellors Engelbert Dollfuss

Engelbert Dollfuß (alternatively: ''Dolfuss'', ; 4 October 1892 – 25 July 1934) was an Austrian clerical fascist politician who served as Chancellor of Austria between 1932 and 1934. Having served as Minister for Forests and Agriculture, he ...

and Kurt Schuschnigg

Kurt Alois Josef Johann von Schuschnigg (; 14 December 1897 – 18 November 1977) was an Austrian Fatherland Front politician who was the Chancellor of the Federal State of Austria from the 1934 assassination of his predecessor Engelbert Doll ...

. In 1938, Schuschnigg resigned in the face of a German invasion, and Seyss-Inquart was appointed his successor. The newly installed Nazis proceeded to transfer power to Germany, and Austria subsequently became the German province of Ostmark

Ostmark is a German term meaning either Eastern march when applied to territories or Eastern Mark when applied to currencies.

Ostmark may refer to:

*the medieval March of Austria and its predecessors ''Bavarian Eastern March'' and ''March of Pann ...

, with Seyss-Inquart as its governor (''Reichsstatthalter'').

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, Seyss-Inquart served briefly as the Deputy Governor General in occupied Poland

' ( Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 Octobe ...

and, following the fall of the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

in 1940, he was appointed ''Reichskommissar

(, rendered as "Commissioner of the Empire", "Reich Commissioner" or "Imperial Commissioner"), in German history, was an official gubernatorial title used for various public offices during the period of the German Empire and Nazi Germany.

Ger ...

'' of the occupied Netherlands. He was a member of the ''Schutzstaffel

The ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS; also stylized as ''ᛋᛋ'' with Armanen runes; ; "Protection Squadron") was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, and later throughout German-occupied Europe duri ...

'' (SS) and held the rank of SS-''Obergruppenführer

' (, "senior group leader") was a paramilitary rank in Nazi Germany that was first created in 1932 as a rank of the ''Sturmabteilung'' (SA) and adopted by the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) one year later. Until April 1942, it was the highest commissio ...

''. He instituted a reign of terror, with Dutch civilians subjected to forced labour and the vast majority of Dutch Jews deported and murdered.

At the Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945, Nazi Germany invaded m ...

, Seyss-Inquart was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity, sentenced to death, and executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

.

Early life

Seyss-Inquart was born in 1892 in Stannern ( cs, Stonařov), a German-speaking village in the neighbourhood of the predominantly German-speaking town of

Seyss-Inquart was born in 1892 in Stannern ( cs, Stonařov), a German-speaking village in the neighbourhood of the predominantly German-speaking town of Iglau

Jihlava (; german: Iglau) is a city in the Czech Republic. It has about 50,000 inhabitants. Jihlava is the capital of the Vysočina Region, situated on the Jihlava River on the historical border between Moravia and Bohemia.

Historically, Jihlava ...

( cs, Jihlava). This area constituted a German linguistic island in the midst of a Czech-speaking region; this may have contributed to the outspoken national consciousness of the family, and the young Arthur in particular. Iglau was an important town in Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The m ...

, one of the Czech provinces of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in which there was increasing competition between Germans and Czechs. His parents were the school principal Emil Zajtich (who changed his surname to Seyss-Inquart) and Augusta Hirenbach. His father was Czech and his mother was German.

The family moved to Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

in 1907. Seyss-Inquart later studied law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

at the University of Vienna

The University of Vienna (german: Universität Wien) is a public research university located in Vienna, Austria. It was founded by Duke Rudolph IV in 1365 and is the oldest university in the German-speaking world. With its long and rich hist ...

. At the beginning of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in August 1914 Seyss-Inquart enlisted with the Austrian Army

The Austrian Armed Forces (german: Bundesheer, lit=Federal Army) are the combined military forces of the Republic of Austria.

The military consists of 22,050 active-duty personnel and 125,600 reservists. The military budget is 0.74% of nati ...

and was given a commission with the Tyrolean ''Kaiserjäger'', subsequently serving in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

. He was decorated for bravery on a number of occasions, and while recovering from wounds in 1917, he completed his final examinations for his degree. Seyss-Inquart had five older siblings: Hedwig (born 1881), Richard (born 3 April 1883, became a Roman Catholic priest, but left the priesthood, married in a civil ceremony and became ''Oberregierungsrat'' enior government counseland prison superior by 1940 in the Ostmark

Ostmark is a German term meaning either Eastern march when applied to territories or Eastern Mark when applied to currencies.

Ostmark may refer to:

*the medieval March of Austria and its predecessors ''Bavarian Eastern March'' and ''March of Pann ...

), Irene (born 1885), Henriette (born 1887) and Robert (born 1891).

In 1911, Seyss-Inquart met Gertrud Maschka. The couple married in December 1916 and had three children: Ingeborg Carolina Augusta Seyss-Inquart (born 18 September 1917), Richard Seyss-Inquart (born 22 August 1921) and Dorothea Seyss-Inquart (born 7 May 1928).

Political career and the ''Anschluss''

He went into law after the war and in 1921 set up his own practice. During the early years of theAustrian First Republic

The First Austrian Republic (german: Erste Österreichische Republik), officially the Republic of Austria, was created after the signing of the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye on 10 September 1919—the settlement after the end of World War I w ...

, he was close to the Fatherland Front. A successful lawyer, he was invited to join the cabinet of Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss

Engelbert Dollfuß (alternatively: ''Dolfuss'', ; 4 October 1892 – 25 July 1934) was an Austrian clerical fascist politician who served as Chancellor of Austria between 1932 and 1934. Having served as Minister for Forests and Agriculture, he ...

in 1933. Following Dollfuss' murder in 1934, he became a State Councillor from 1937 under Kurt Schuschnigg

Kurt Alois Josef Johann von Schuschnigg (; 14 December 1897 – 18 November 1977) was an Austrian Fatherland Front politician who was the Chancellor of the Federal State of Austria from the 1934 assassination of his predecessor Engelbert Doll ...

. A keen mountaineer, Seyss-Inquart became the head of the German-Austrian Alpine Club. He later became a devotee of Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

's concepts of racial purity and sponsored various expeditions to Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Taman ...

and other parts of Asia in hopes of proving Aryan racial concepts and theories. He was not initially a member of the Austrian National Socialist party, though he was sympathetic to many of their views and actions. By 1938, however, Seyss-Inquart knew which way the political wind was blowing and became a respectable frontman for the Austrian National Socialists.

In February 1938, Seyss-Inquart was appointed Austrian

In February 1938, Seyss-Inquart was appointed Austrian Minister of the Interior

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergency ...

by Schuschnigg, after Hitler had threatened Schuschnigg with military actions against Austria in the event of non-compliance. On 11 March 1938, faced with a German invasion aimed at preventing a plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

on independence, Schuschnigg resigned as Austrian Chancellor. Under growing pressure from Berlin, President Wilhelm Miklas

Wilhelm Miklas (15 October 187220 March 1956) was an Austrian politician who served as President of Austria from 1928 until the ''Anschluss'' to Nazi Germany in 1938.

Early life

Born as the son of a post official in Krems, in the Cisleithanian ...

reluctantly appointed Seyss-Inquart his successor. On the next day German troops crossed the border of Austria at the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

ed invitation of Seyss-Inquart. This telegram had actually been drafted beforehand and was released after the troops had begun to march, so as to justify the action in the eyes of the international community. Before his triumphant entry into Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, Hitler had planned to leave Austria as a pro-Nazi puppet state headed by Seyss-Inquart. However, the acclamation for the German army from the majority of the Austrian population led Hitler to change course and opt for a full ''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

'', in which Austria was incorporated into Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

as the province of Ostmark

Ostmark is a German term meaning either Eastern march when applied to territories or Eastern Mark when applied to currencies.

Ostmark may refer to:

*the medieval March of Austria and its predecessors ''Bavarian Eastern March'' and ''March of Pann ...

. Only then, on 13 March 1938, did Seyss-Inquart join the Nazi Party.

Head of Ostmark and Southern Poland

Seyss-Inquart drafted the legislative act reducing Austria to a province of Germany and signed it into law on 13 March. With Hitler's approval, he became Governor ('' Reichsstatthalter'') of the newly named Ostmark, thus becoming Hitler's personal representative in Austria. Ernst Kaltenbrunner served as chief minister and Josef Burckel as Commissioner for the Reunion of Austria (concerned with the "Jewish Question"). Seyss-Inquart also received an honorary SS rank of Gruppenführer and in May 1939 he was made a ''Reichsminister

Reichsminister (in German singular and plural; 'minister of the realm') was the title of members of the German Government during two historical periods: during the March revolution of 1848/1849 in the German Reich of that period, and in the mode ...

'' without Portfolio in Hitler's cabinet. Almost as soon as he took office, he ordered the confiscation of Jewish property and sent Jews to concentration camps. Late in his regime, he collaborated in the deportation of Jews from Austria.

Following the invasion of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

, Seyss-Inquart was named as the Chief of Civil Administration for Southern Poland, but did not take up that post before the General Government was created, in which he became Deputy to the Governor General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy ...

Hans Frank

Hans Michael Frank (23 May 1900 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and lawyer who served as head of the General Government in Nazi-occupied Poland during the Second World War.

Frank was an early member of the German Workers' Party ...

, remaining in this position until 18 May 1940. He fully supported the heavy-handed policies put into effect by Frank, including persecution of Jews. He was also aware of the '' Abwehr''s murder of Polish intellectuals.

Reichskommissar in the Netherlands

Following the capitulation of the

Following the capitulation of the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

Seyss-Inquart was appointed ''Reichskommissar

(, rendered as "Commissioner of the Empire", "Reich Commissioner" or "Imperial Commissioner"), in German history, was an official gubernatorial title used for various public offices during the period of the German Empire and Nazi Germany.

Ger ...

'' for the Occupied Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

in May 1940, charged with directing the civil administration, with creating close economic collaboration with Germany and with defending the interests of the Reich

''Reich'' (; ) is a German noun whose meaning is analogous to the meaning of the English word "realm"; this is not to be confused with the German adjective "reich" which means "rich". The terms ' (literally the "realm of an emperor") and ' (lit ...

. In April 1941, he was promoted to SS-''Obergruppenführer

' (, "senior group leader") was a paramilitary rank in Nazi Germany that was first created in 1932 as a rank of the ''Sturmabteilung'' (SA) and adopted by the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) one year later. Until April 1942, it was the highest commissio ...

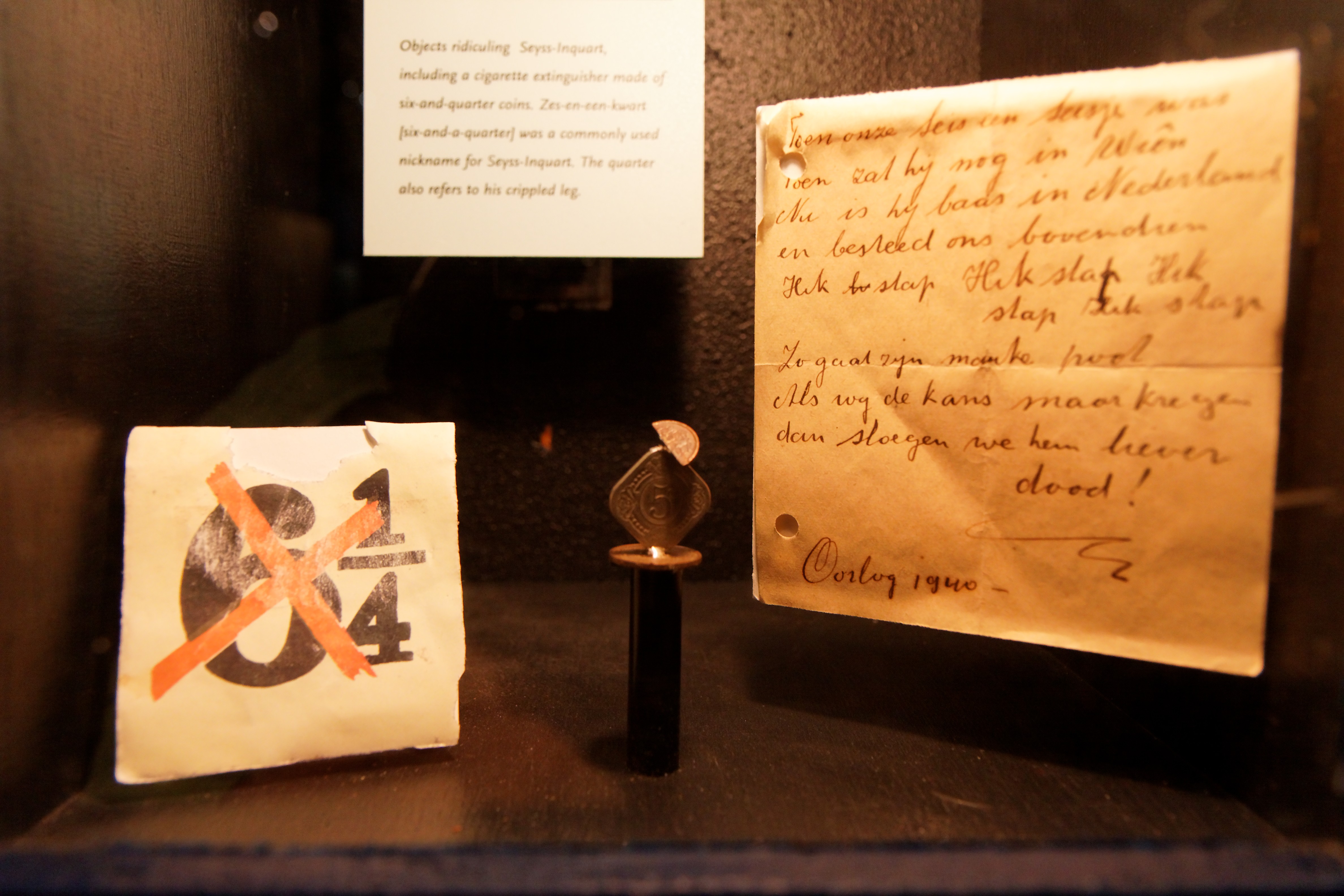

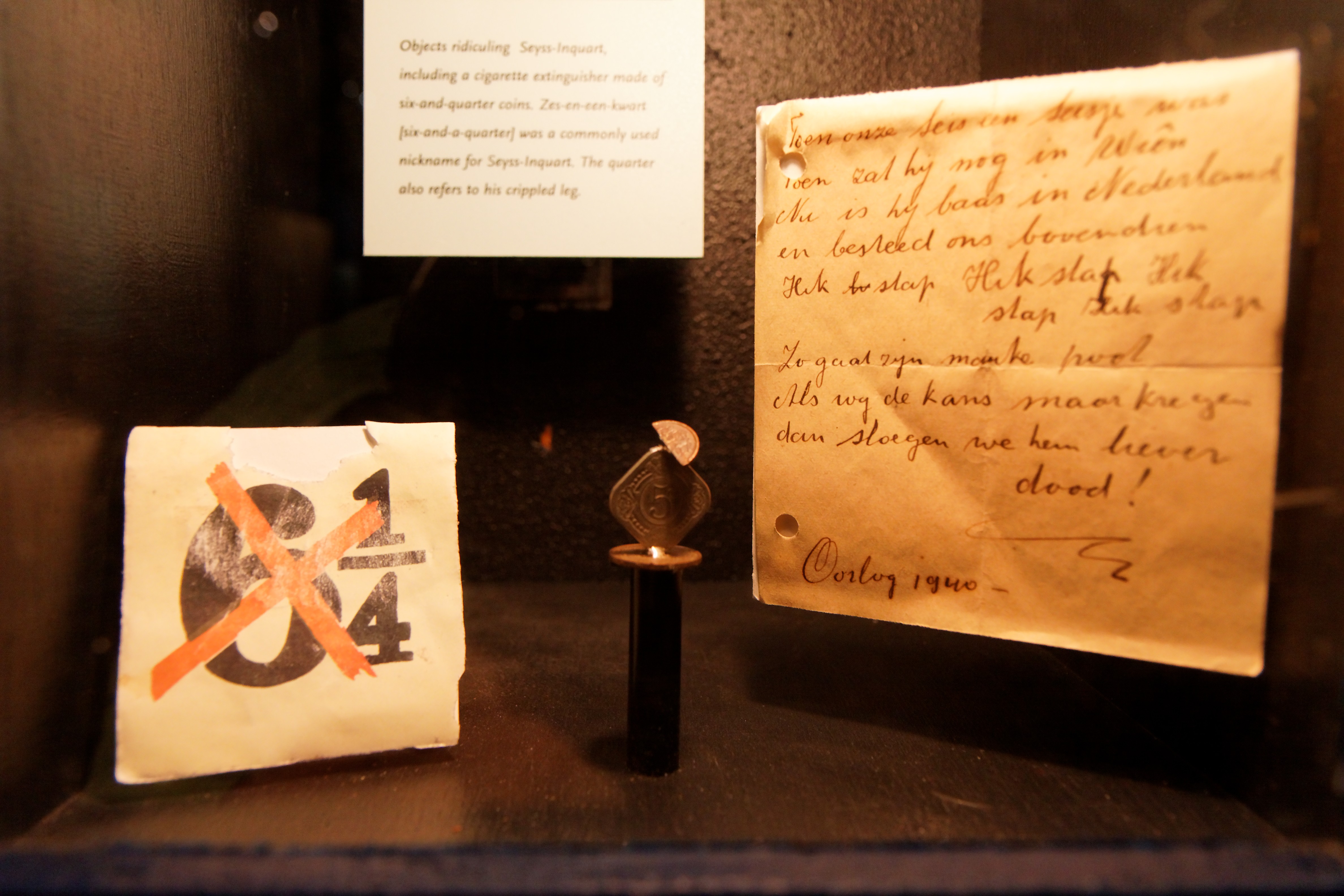

''. Among the Dutch people he was mockingly referred to as "Zes en een kwart" (six and a quarter), a play on his name, and the fact that Seyss-Inquart suffered from a limp. He supported the Dutch NSB and allowed them to create the paramilitary Nederlandse Landwacht, which acted as an auxiliary police force. Other political parties were banned in late 1941 and many former government officials were imprisoned at Sint-Michielsgestel

Sint-Michielsgestel () is a village in the municipality of Sint-Michielsgestel, Netherlands.

Geography

The 120 km long river Dommel flows north from a well near Peer in Belgium. Just north of 's-Hertogenbosch it is joined by the Aa and ...

. The administration of the country was controlled by Seyss-Inquart himself and he answered directly to Hitler. He oversaw the politicization of cultural groups from the ''Nederlandsche Kultuurkamer'' "right down to 'the chessplayers' club", and set up a number of other politicised associations.

He introduced measures to combat resistance, and when there was a widespread strike in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

, Arnhem

Arnhem ( or ; german: Arnheim; South Guelderish: ''Èrnem'') is a city and municipality situated in the eastern part of the Netherlands about 55 km south east of Utrecht. It is the capital of the province of Gelderland, located on both ban ...

and Hilversum in May 1943, special summary court-martial procedures were brought in, and a collective fine of 18 million guilder

Guilder is the English translation of the Dutch and German ''gulden'', originally shortened from Middle High German ''guldin pfenninc'' " gold penny". This was the term that became current in the southern and western parts of the Holy Roman Emp ...

s was imposed. Up until the liberation, Seyss-Inquart authorized about 800 executions, although some reports put the total at over 1,500, including executions under the so-called "Hostage Law", the death of political prisoners who were close to being liberated, the Putten raid

The Putten raid (Dutch: ''Razzia van Putten'') was a civilian raid conducted by Nazi Germany in occupied Netherlands during the Second World War. On 1 October 1944, a total of 602 men – almost the entire male population of the village – were ...

, and the reprisal executions of 117 Dutchmen for the attack on SS and Police Leader Hanns Albin Rauter

Johann Baptist Albin Rauter (4 February 1895 – 24 March 1949) was a high-ranking Austrian-born SS functionary and war criminal during the Nazi era. He was the highest SS and Police Leader in the occupied Netherlands and therefore the leading ...

. Although the majority of Seyss-Inquart's powers were transferred to the military commander in the Netherlands and the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

in July 1944, he remained a force to be reckoned with. It is thought he met with Haj Amin al-Husseini

Mohammed Amin al-Husseini ( ar, محمد أمين الحسيني 1897

– 4 July 1974) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and Muslim leader in Mandatory Palestine.

Al-Husseini was the scion of the al-Husayni family of Jerusalemite Arab notable ...

, an exiled leader of Palestinian Arabs, Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

The Grand Mufti of Jerusalem is the Sunni Muslim cleric in charge of Jerusalem's Islamic holy places, including the Al-Aqsa Mosque. The position was created by the British military government led by Ronald Storrs in 1918.See Islamic Leadershi ...

, somewhere in Germany in 1943.

There were three concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

s in the Netherlands: the smaller KZ Herzogenbusch near Vught

Vught () is a municipality and a town in the southern Netherlands, and lies just south of the industrial and administrative centre of 's-Hertogenbosch. Many commuters live in the municipality, and the town of Vught was once named "Best place to liv ...

, Kamp Amersfoort

Kamp Amersfoort ( nl, Kamp Amersfoort, german: Durchgangslager Amersfoort) was a Nazi concentration camp near the city of Amersfoort, the Netherlands. The official name was "Polizeiliches Durchgangslager Amersfoort", P.D.A. or Amersfoort Police ...

near Amersfoort

Amersfoort () is a city and municipality in the province of Utrecht, Netherlands, about 20 km from the city of Utrecht and 40 km south east of Amsterdam. As of 1 December 2021, the municipality had a population of 158,531, making it the second- ...

, and Westerbork transit camp

Camp Westerbork ( nl, Kamp Westerbork, german: Durchgangslager Westerbork, Drents: ''Börker Kamp; Kamp Westerbörk'' ), also known as Westerbork transit camp, was a Nazi transit camp in the province of Drenthe in the Northeastern Netherlands, d ...

(a "Jewish assembly camp"); there were a number of other camps variously controlled by the military, the police, the SS or Seyss-Inquart's administration. These included a "voluntary labour recruitment" camp at Ommen

Ommen () is a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality and a Hanseatic League, Hanseatic city in the eastern Netherlands. It is located in the Vechte, Vecht valley of the Salland region in Overijssel. Historical records first name Ommen in ...

( Camp Erika). In total around 530,000 Dutch civilians were forced to work for the Germans, of whom 250,000 were sent to factories in Germany. There was an unsuccessful attempt by Seyss-Inquart to send only workers aged 21 to 23 to Germany, and he refused demands in 1944 for a further 250,000 Dutch workers and in that year sent only 12,000 people.

Seyss-Inquart was an unwavering

Seyss-Inquart was an unwavering anti-Semite

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

; within a few months of his arrival in the Netherlands, he took measures to remove Jews from the government, the press and leading positions in industry. Anti-Jewish measures intensified after 1941: approximately 140,000 Jews were registered, a "ghetto" was created in Amsterdam and a transit camp was set up at Westerbork

Camp Westerbork ( nl, Kamp Westerbork, german: Durchgangslager Westerbork, Drents: ''Börker Kamp; Kamp Westerbörk'' ), also known as Westerbork transit camp, was a Nazi transit camp in the province of Drenthe in the Northeastern Netherlands, ...

. Subsequently, in February 1941, 600 Jews were sent to Buchenwald

Buchenwald (; literally 'beech forest') was a Nazi concentration camp established on hill near Weimar, Germany, in July 1937. It was one of the first and the largest of the concentration camps within Germany's 1937 borders. Many actual or sus ...

, a concentration camp located within Germany's borders, and to Mauthausen

Mauthausen was a Nazi concentration camp on a hill above the market town

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regu ...

, located in Upper Austria. Later, the Dutch Jews were sent to Auschwitz, the notorious complex operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland. As Allied forces approached in September 1944, the remaining Jews at Westerbork were removed to Theresienstadt

Theresienstadt Ghetto was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress town of Terezín, in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia ( German-occupied Czechoslovakia). Theresienstadt served as a waystation to the extermination ca ...

, the SS-established concentration camp/ghetto in the Nazi German-occupied region of Czechoslovakia. Of the 140,000 that were registered, only 30,000 Dutch Jews

The history of the Jews in the Netherlands began largely in the 16th century when they began to settle in Amsterdam and other cities. It has continued to the present. During the occupation of the Netherlands by Nazi Germany in May 1940, the J ...

survived the war.

When the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

advanced into the Netherlands in late 1944, the Nazi regime had attempted to enact a scorched earth policy, and some docks and harbours were destroyed. Seyss-Inquart, however, was in agreement with Armaments Minister Albert Speer over the futility of such actions, and with the open connivance of many military commanders, they greatly limited the implementation of the scorched earth orders. At the very end of the " hunger winter" in April 1945, Seyss-Inquart was with difficulty persuaded by the Allies to allow airplanes to drop food for the hungry people of the occupied north-west of the country. Although he knew the war was lost, Seyss-Inquart did not want to surrender.

Before Hitler committed suicide in April 1945, he named a new government headed by Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz in his last will and testament

A will or testament is a legal document that expresses a person's (testator) wishes as to how their property ( estate) is to be distributed after their death and as to which person ( executor) is to manage the property until its final distributi ...

, in which Seyss-Inquart replaced Joachim von Ribbentrop, who had long since fallen out of favour, as Foreign Minister. It was a token of the high regard Hitler felt for his Austrian comrade, at a time when he was rapidly disowning or being abandoned by so many of his other key lieutenants. Unsurprisingly, at such a late stage in the war, Seyss-Inquart failed to achieve anything in his new office.

He remained in his posts until 7 May 1945, when, after a meeting with Dönitz to confirm his rescission of the scorched earth orders, he was arrested on the Elbe Bridge in Hamburg by two soldiers of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers

The Royal Welch Fusiliers ( cy, Ffiwsilwyr Brenhinol Cymreig) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, and part of the Prince of Wales' Division, that was founded in 1689; shortly after the Glorious Revolution. In 1702, it was designated ...

, one of whom was Norman Miller (birth name: Norbert Mueller), a German Jew from Nuremberg who had escaped to Britain at the age of 15 on a ''Kindertransport

The ''Kindertransport'' (German for "children's transport") was an organised rescue effort of children (but not their parents) from Nazi-controlled territory that took place during the nine months prior to the outbreak of the Second World ...

'' just before the war and then returned to Germany as part of the British occupation forces. Miller's entire family had been killed at the Jungfernhof Camp in Riga, Latvia in March 1942. The Anglo-Dutch art dealer Edward Speelman was also involved in Seyss-Inquart's arrest.

Nuremberg trials

At the

At the Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945, Nazi Germany invaded m ...

, Seyss-Inquart was defended by Gustav Steinbauer and faced four charges: conspiracy to commit crimes against peace; planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression; war crimes; and crimes against humanity. During the trial, Gustave Gilbert, an American army psychologist, was allowed to examine the Nazi leaders who were tried at Nuremberg for war crimes. Among other tests, a German version of the Wechsler-Bellevue IQ test

An intelligence quotient (IQ) is a total score derived from a set of standardized tests or subtests designed to assess human intelligence. The abbreviation "IQ" was coined by the psychologist William Stern (psychologist), William Stern for th ...

was administered. Arthur Seyss-Inquart scored 141, the second highest among the defendants, behind Hjalmar Schacht

Hjalmar Schacht (born Horace Greeley Hjalmar Schacht; 22 January 1877 – 3 June 1970, ) was a German economist, banker, centre-right politician, and co-founder in 1918 of the German Democratic Party. He served as the Currency Commissioner ...

.

In his final statement, Seyss-Inquart denied knowledge of various war crimes including the shooting of hostages, and said that while he had moral objections to the deportation of Jews, there must sometimes be justifications for mass evacuations, and pointed to the Allies forcibly resettling millions of Germans after the war. He added that his "conscience was untroubled" as he improved the conditions of the Dutch people while Commissioner. Seyss-Inquart concluded by saying, "My last word is the principle by which I have always acted and to which I will adhere to my last breath: I believe in Germany."

Seyss-Inquart was acquitted of conspiracy, but convicted on all other counts and sentenced to death by hanging. The final judgment against him cited his involvement in harsh suppression of Nazi opponents and atrocities against the Jews during all his billets, but particularly stressed his reign of terror in the Netherlands. It was these atrocities that sent him to the gallows.

Upon hearing of his death sentence, Seyss-Inquart was fatalistic: "Death by hanging... well, in view of the whole situation, I never expected anything different. It's all right."

Before his execution, Seyss-Inquart returned to the Catholic church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, receiving absolution in the sacrament of confession

A confession is a statement – made by a person or by a group of persons – acknowledging some personal fact that the person (or the group) would ostensibly prefer to keep hidden. The term presumes that the speaker is providing information th ...

from prison chaplain Prison religion includes the religious beliefs and practices of prison inmates, usually stemming from or including concepts surrounding their imprisonment and accompanying lifestyle. "Prison Ministry" is a larger concept, including the support of th ...

Father Bruno Spitzl.

He was hanged in Nuremberg Prison on 16 October 1946, at the age of 54, together with nine other Nuremberg defendants. He was the last to mount the scaffold, and his last words

Last words are the final utterances before death. The meaning is sometimes expanded to somewhat earlier utterances.

Last words of famous or infamous people are sometimes recorded (although not always accurately) which became a historical and liter ...

were the following: "I hope that this execution is the last act of the tragedy of the Second World War and that the lesson taken from this world war will be that peace and understanding should exist between peoples. I believe in Germany."

His body, with those of the other nine executed men and that of Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

(who committed suicide the previous day), was cremated at the Ostfriedhof in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and Ha ...

, and their ashes were scattered into the river Isar.

Cultural references

InDoris Orgel

Doris Orgel is an Austrian-born American children's literature author. She was born Doris Adelberg in Vienna, Austria on February 15, 1929. In the 1930s she fled Vienna with her parents due to her Jewish descent. She lives in New York City and ...

's children's novel, ''The Devil in Vienna'', he is the father of Lise, the only Gentile

Gentile () is a word that usually means "someone who is not a Jew". Other groups that claim Israelite heritage, notably Mormons, sometimes use the term ''gentile'' to describe outsiders. More rarely, the term is generally used as a synonym fo ...

friend of its Jewish character Inge Dournenvald, and his only daughter, second born after his son, Heinz. In the Disney Channel movie, ''A Friendship in Vienna

''A Friendship in Vienna'' is a 1988 Disney Channel film based on Doris Orgel's popular children's book

''The Devil in Vienna''. The film starred Jane Alexander, Stephen Macht and Edward Asner and premiered on August 27, 1988.

Plot

Lise Muelle ...

'', based on this novel, he is ''Herr Mueller'', played by John Hartley, the SA officer of that film.

See also

* List of SS-Obergruppenführer *Nazi plunder

Nazi plunder (german: Raubkunst) was the stealing of art and other items which occurred as a result of the organized looting of European countries during the time of the Nazi Party in Germany. The looting of Polish and Jewish property was a k ...

*The Holocaust in the Netherlands

The Holocaust in the Netherlands was part of the European-wide Holocaust organized by Nazi Germany and took place in the German-occupied Netherlands.

In 1939, there were some 140,000 Dutch Jews living in the Netherlands, among them some 24,000 to ...

*Kajetan Mühlmann

Kajetan "Kai" Mühlmann (26 June 1898 – 2 August 1958) was an Austrian art historian who was an officer in the SS and played a major role in the expropriation of art by the Nazis, particularly in Poland and the Netherlands. He worked with Arth ...

*''Anschluss

The (, or , ), also known as the (, en, Annexation of Austria), was the annexation of the Federal State of Austria into the German Reich on 13 March 1938.

The idea of an (a united Austria and Germany that would form a " Greater Germany ...

''

References

Further reading

* * * Graf, Wolfgang: ''Österreichische SS-Generäle. Himmlers verlässliche Vasallen.'' Hermagoras-Verlag, Klagenfurt/Ljubljana/Wien 2012, . * Koll, Johannes: ''Arthur Seyß-Inquart und die deutsche Besatzungspolitik in den Niederlanden (1940–1945)''. Böhlau, Wien . a.2015, . * Koll, Johannes: ''From the Habsburg Empire to the Third Reich: Arthur Seyß-Inquart and National Socialism.'' In:Günter Bischof

Günter Bischof (born 6 October 1953 in Mellau, Vorarlberg) is an Austrian-American historian and university professor. A specialist in 20th century diplomatic history, and a graduate of University of New Orleans, Innsbruck University and Harvard U ...

, Fritz Plasser, Eva Maltschnig (Hrsg.): ''Austrian Lives'' (= Contemporary Austrian Studies, Bd. 21). University of New Orleans Press/Innsbruck University Press, New Orleans/Innsbruck 2012, S. 123–146, .

*

*

* Zebhauser, Helmuth: ''Alpinismus im Hitlerstaat. Gedanken, Erinnerungen, Dokumente.'' Dokumente des Alpinismus, Band 1. Rother, München 1998, .

External links

Arthur Seyss-Inquart at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

* * * , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Seyss-Inquart, Arthur 1892 births 1946 deaths 20th-century Chancellors of Austria Austro-Hungarian military personnel of World War I Austrian Ministers of Defence Austrian Nazi lawyers Austrian people of Czech descent Executed Austrian Nazis Austrian people convicted of crimes against humanity Executed Austrian people Austrian Roman Catholics Chancellors of Austria Fascist rulers Foreign Ministers of Germany General Government German nationalists German people convicted of the international crime of aggression Heads of government convicted of war crimes Heads of state convicted of war crimes Holocaust perpetrators in the Netherlands Holocaust perpetrators in Poland Holocaust perpetrators in Austria Holocaust perpetrators in Germany Members of the Reichstag of Nazi Germany Moravian-German people Nazi Germany ministers Nazi Party officials Netherlands in World War II People from Jihlava District People from the Margraviate of Moravia People executed by the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg People executed for crimes against humanity SS-Obergruppenführer World War II political leaders Heads of government who were later imprisoned Christian fascists Austro-Hungarian Army officers