Argentina during World War II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Before the start of

''Un enigma: la "irracionalidad" Argentina frente a la Segunda Guerra Mundial'', Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe, Vol. 6 Nº 2, jul-dic 1995, Universidad de Tel Aviv

/ref> At the same time, British influence over the Argentine economy was resented by nationalistic groups, while

At the beginning of World War Two, in 1939, Roberto María Ortiz was the

At the beginning of World War Two, in 1939, Roberto María Ortiz was the

On 13 December 1939, the

On 13 December 1939, the

From the beginning of his administration, Ortiz had been suffering from diabetes, and his health continued to deteriorate throughout his presidency. By 3 July 1940, after only two years in office, Ortiz had lost much of his

From the beginning of his administration, Ortiz had been suffering from diabetes, and his health continued to deteriorate throughout his presidency. By 3 July 1940, after only two years in office, Ortiz had lost much of his  On the side of those opposing entry into the war, FORJA was the only political party that supported neutrality throughout the war, seeing it as an opportunity to get rid of what they considered British meddling with the Argentine economy. Starting in 1940, the FORJA faction led by Dellepiane and Del Mazo had drifted away from the organization and rejoined the UCR, while FORJA itself adopted more nationalistic and left-wing ideas, under the leadership of Arturo Jauretche.Scenna, Miguel Ángel (1983). "FORJA, una aventura argentina (De Yrigoyen a Perón)". Buenos Aires:de Belgrano. ISBN 950-577-057-8 Nationalistic sectors of the army also promoted neutrality as a way to oppose the United Kingdom and its economic influence. Notably during this time, a plan was made by the Naval War College to invade the

On the side of those opposing entry into the war, FORJA was the only political party that supported neutrality throughout the war, seeing it as an opportunity to get rid of what they considered British meddling with the Argentine economy. Starting in 1940, the FORJA faction led by Dellepiane and Del Mazo had drifted away from the organization and rejoined the UCR, while FORJA itself adopted more nationalistic and left-wing ideas, under the leadership of Arturo Jauretche.Scenna, Miguel Ángel (1983). "FORJA, una aventura argentina (De Yrigoyen a Perón)". Buenos Aires:de Belgrano. ISBN 950-577-057-8 Nationalistic sectors of the army also promoted neutrality as a way to oppose the United Kingdom and its economic influence. Notably during this time, a plan was made by the Naval War College to invade the

The situation changed dramatically after the Japanese

The situation changed dramatically after the Japanese

The new government proceeded with both progressive and reactionary policies. Maximum prices were established for popular products, rents were reduced, the privileges of the Chadopyff factory were annulled and hospital fees were abolished. On the other hand, the authorities intervened trade unions, closed the Communist newspaper ''La Hora'' and imposed religious education at schools.

The new government proceeded with both progressive and reactionary policies. Maximum prices were established for popular products, rents were reduced, the privileges of the Chadopyff factory were annulled and hospital fees were abolished. On the other hand, the authorities intervened trade unions, closed the Communist newspaper ''La Hora'' and imposed religious education at schools.  The government held diplomatic discussions with the United States, with Argentina requesting aircraft, fuel, ships and military hardware. The Argentine

The government held diplomatic discussions with the United States, with Argentina requesting aircraft, fuel, ships and military hardware. The Argentine

The

The

During World War II, 4,000 Argentines served with all three

During World War II, 4,000 Argentines served with all three

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

in 1939, Argentina had maintained a long tradition of neutrality regarding European wars, which had been upheld and defended by all major political parties since the 19th century. One of the main reasons for this policy was related to Argentina's economic position as one of the world's leading exporters of foodstuffs and agricultural products, to Europe in general and to the United Kingdom in particular. Relations between Britain and Argentina had been strong since the mid-19 century, due to the large volume of trade between both countries, the major presence of British investments particularly in railroads and banking, as well as British immigration, and the policy of neutrality had ensured the food supply of Britain during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

against the German U-boat campaign

The U-boat Campaign from 1914 to 1918 was the World War I naval campaign fought by German U-boats against the trade routes of the Allies. It took place largely in the seas around the British Isles and in the Mediterranean.

The German Empir ...

.Carlos Escudé''Un enigma: la "irracionalidad" Argentina frente a la Segunda Guerra Mundial'', Estudios Interdisciplinarios de América Latina y el Caribe, Vol. 6 Nº 2, jul-dic 1995, Universidad de Tel Aviv

/ref> At the same time, British influence over the Argentine economy was resented by nationalistic groups, while

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

and Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

influence in Argentina was strong and growing mainly due to increased interwar trade and investment, and the presence of numerous immigrants from both countries, which, together with the refusal to break relations with the Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

as the war progressed, furthered the belief that the Argentine government was sympathetic to the German cause. Because of strong divisions and internal disputes between members of the Argentine military

The Armed Forces of the Argentine Republic, in es, Fuerzas Armadas de la República Argentina, are controlled by the Commander-in-Chief (the President) and a civilian Minister of Defense. In addition to the Army, Navy and Air Force, there are ...

, Argentina remained neutral

Neutral or neutrality may refer to:

Mathematics and natural science Biology

* Neutral organisms, in ecology, those that obey the unified neutral theory of biodiversity

Chemistry and physics

* Neutralization (chemistry), a chemical reaction in ...

for most of World War II, despite pressure from the United States to join the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

. However, Argentina eventually gave in to the Allies' pressure, broke relations with the Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

on 26 January 1944,Galasso, pp. 194–196 and declared war on 27 March 1945.Galasso, pp. 248–251

Political and economic background leading to World War II

Before the Great Depression

In 1916, following the enactment of universal and secret male suffrage byconservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

president Roque Saenz Peña, the voting franchise was expanded, and electoral transparency improved, leading to the first truly free presidential elections in the country. As a result of these electoral changes, Hipólito Yrigoyen

Juan Hipólito del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús Yrigoyen (; 12 July 1852 – 3 July 1933) was an Argentine politician of the Radical Civic Union and two-time President of Argentina, who served his first term from 1916 to 1922 and his second ...

, leader of the centrist Radical Civic Union

The Radical Civic Union ( es, Unión Cívica Radical, UCR) is a centrist and social-liberal political party in Argentina. It has been ideologically heterogeneous, ranging from social liberalism to social democracy. The UCR is a member of the S ...

, was elected Elected may refer to:

* "Elected" (song), by Alice Cooper, 1973

* ''Elected'' (EP), by Ayreon, 2008

*The Elected, an American indie rock band

See also

*Election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population ...

President of Argentina

The president of Argentina ( es, Presidente de Argentina), officially known as the president of the Argentine Nation ( es, Presidente de la Nación Argentina), is both head of state and head of government of Argentina. Under the national cons ...

. Under the successive administrations of presidents Hipólito Yrigoyen

Juan Hipólito del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús Yrigoyen (; 12 July 1852 – 3 July 1933) was an Argentine politician of the Radical Civic Union and two-time President of Argentina, who served his first term from 1916 to 1922 and his second ...

(1916–1922) and Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear (1922–1928), Argentina continued the trend of strong economic growth and democratic consolidation that had begun under previous administrations, matching countries such as Canada or Australia in per capita income, while the government enacted social and economic reforms and extended assistance to small farms and businesses. However, beginning in 1928, the second administration of Hipólito Yrigoyen

Juan Hipólito del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús Yrigoyen (; 12 July 1852 – 3 July 1933) was an Argentine politician of the Radical Civic Union and two-time President of Argentina, who served his first term from 1916 to 1922 and his second ...

would face a crippling economic crisis, precipitated by the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. In 1930, Yrigoyen was ousted from power by the military led by José Félix Uriburu, in what became the first military coup

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

in modern Argentine history, marking the beginning of what would be later called the Infamous Decade in Argentina.

1930 military coup

Supported by nationalistic sectors of the military, Uriburu tried to implement major changes to Argentinean politics and government, banning political parties, suspending elections, and suspending the 1853 Constitution, with the aim to reorganizing Argentina alongcorporatist

Corporatism is a collectivist political ideology which advocates the organization of society by corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guild associations, on the basis of their common interests. The ...

and fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

lines. However, Uriburu's policies would face widespread opposition from civil society and from conservative factions of the military, and only a year later, in 1931, he was forced to step down. Thus, in November 1931, the military government called for elections, but only after banning UCR candidates and organizing a system that was broadly recognized as fraudulent

In law, fraud is intentional deception to secure unfair or unlawful gain, or to deprive a victim of a legal right. Fraud can violate civil law (e.g., a fraud victim may sue the fraud perpetrator to avoid the fraud or recover monetary compens ...

. It was under these conditions that General Agustín P. Justo was elected president.

Presidency of Agustín P. Justo

Elected Elected may refer to:

* "Elected" (song), by Alice Cooper, 1973

* ''Elected'' (EP), by Ayreon, 2008

*The Elected, an American indie rock band

See also

*Election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population ...

on 8 November 1931, Agustín P. Justo was supported by a newly created conservative party known as '' Concordancia'', which was born as an alliance between the National Democratic Party, dissident sectors of the Radical Civic Union

The Radical Civic Union ( es, Unión Cívica Radical, UCR) is a centrist and social-liberal political party in Argentina. It has been ideologically heterogeneous, ranging from social liberalism to social democracy. The UCR is a member of the S ...

that had opposed Hipólito Yrigoyen

Juan Hipólito del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús Yrigoyen (; 12 July 1852 – 3 July 1933) was an Argentine politician of the Radical Civic Union and two-time President of Argentina, who served his first term from 1916 to 1922 and his second ...

, and the Independent Socialist Party. Still reeling from the aftermath of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, the government of Agustín P. Justo at first undertook fiscally conservative economic policies, reducing public expenditure and restricting the circulation of currency in an attempt to strengthen the public coffers. However, as in other countries during this period, latter economic policy begun adopting some of the new Keynesian

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output an ...

ideas, and more emphasis was placed on public works and infraestructure, creating the National Office of Public Highways and expanding the road network, creating the Junta Nacional de Granos ( National Grain Board) and the Junta Nacional de Carnes ( National Meat Board), followed soon after, in 1935, by the creation of the Central Bank of the Argentine Republic, under the advice of economist Otto Niemeyer

Sir Otto Ernst Niemeyer (23 November 1883 – 6 February 1971) was a British banker and civil servant. He served as a director of the Bank of England from 1938 to 1952 and a director of the Bank for International Settlements from 1931 to 1965.

...

.

In foreign policy, the most pressing issue of the Justo administration was the restoration of international trade, which had collapsed following the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

.

As a byproduct of Black Tuesday

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange coll ...

and the Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange coll ...

, Great Britain, principal economic partner of Argentina in the 1920s and 1930s, had taken measures to protect the meat supply market in the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

. At the 1932 Imperial Conference negotiations in Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the c ...

, bowing to pressure, mainly from Australia and South Africa, Britain had decided to severely curtail imports of Argentine beef. The plan provoked an immediate outcry in Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

, and the Argentine government dispatched Vice-president Roca and a team of negotiators to London. As a result of these negotiations, on 1 May 1933, the bilateral treaty known as the '' Roca-Runciman Treaty'' was signed between Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

and the United Kingdom, which guaranteed Argentina a beef export quota that was equivalent to the levels sold in 1932, in exchange for Argentina reducing tariffs on almost 350 British goods to 1930 rates and to refrain from imposing duties on coal, strengthening the commercial ties between Argentina and Britain and ensuring a trade surplus

The balance of trade, commercial balance, or net exports (sometimes symbolized as NX), is the difference between the monetary value of a nation's exports and imports over a certain time period. Sometimes a distinction is made between a balanc ...

during the turmoil of the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, but drawing ire from nationalistic sectors and several opposition senators, including the denunciations of liberal Senator Lisandro de la Torre

Lisandro de la Torre (6 December 1868 – 5 January 1939) was an Argentine politician, born in Rosario, Santa Fe. He was considered as a model of ethics in politics. He was a national deputy and senator, a prominent polemicist, and founder ...

, who claimed that Britain received the most benefits from the treaty. Ratified by the Argentine Senate

The Honorable Senate of the Argentine Nation ( es, Honorable Senado de la Nación Argentina) is the upper house of the National Congress of Argentina.

Overview

The National Senate was established by the Argentine Confederation on July 29, 18 ...

, the Roca-Runciman Treaty lasted three years and was renewed for another three years as the Eden-Malbrán Treaty of 1936. Argentina under Justo would also rejoin the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

, and hold State Visits to presidents Getúlio Vargas

Getúlio Dornelles Vargas (; 19 April 1882 – 24 August 1954) was a Brazilian lawyer and politician who served as the 14th and 17th president of Brazil, from 1930 to 1945 and from 1951 to 1954. Due to his long and controversial tenure as Brazi ...

of Brazil and Gabriel Terra

José Luis Gabriel Terra Leivas ( Montevideo, 1 August 1873 - Montevideo, 15 September 1942) was a lawyer and politician of batllista origin in Uruguay, and advisor to all Uruguayan governments on diplomatic, Economic and financial issu ...

of Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

, signing commercial treaties with those nations.

Justo's foreign minister, Carlos Saavedra Lamas

Carlos Saavedra Lamas (November 1, 1878–May 5, 1959) was an Argentine academic and politician, and in 1936, the first Latin American Nobel Peace Prize recipient.

Biography

Born in Buenos Aires, Saavedra Lamas was a descendant of an early Arge ...

would also serve an important role as a mediator in the Chaco War

The Chaco War ( es, link=no, Guerra del Chaco, gn, Cháko ÑorairõBolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

and Paraguay

Paraguay (; ), officially the Republic of Paraguay ( es, República del Paraguay, links=no; gn, Tavakuairetã Paraguái, links=si), is a landlocked country in South America. It is bordered by Argentina to the south and southwest, Brazil to t ...

, helping both countries reach a peace deal, thus winning the 1936 Nobel Peace Prize.

Mounting political tensions

In the aftermath of the 1930 military coup and the subsequent accusations ofelectoral fraud

Electoral fraud, sometimes referred to as election manipulation, voter fraud or vote rigging, involves illegal interference with the process of an election, either by increasing the vote share of a favored candidate, depressing the vote share of ...

against Justo, political tensions in Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

would remain high throughout the 1930s. On 5 April 1931, supporters of deposed president Yrigoyen won the elections for governor in the Province of Buenos Aires, but the government of Uriburu declared the elections invalid. On December, facing uprisings by UCR supporters, Justo decreed a state of siege, and again imprisoned the old Yrigoyen, as well as Alvear, Ricardo Rojas, Honorio Pueyrredón, and other leading figures of the party.

In 1933, attempted revolts continued. Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

, Corrientes

Corrientes (; Guaraní: Taragüí, literally: "Currents") is the capital city of the province of Corrientes, Argentina, located on the eastern shore of the Paraná River, about from Buenos Aires and from Posadas, on National Route 12. It ha ...

, Entre Ríos, and Misiones would be the stage of UCR uprisings, which ended with more than a thousand people being detained. Seriously ill, Yrigoyen was returned to Buenos Aires and kept under house arrest. He died on 3 June, and his burial in La Recoleta Cemetery

La Recoleta Cemetery ( es, Cementerio de la Recoleta) is a cemetery located in the Recoleta neighbourhood of Buenos Aires, Argentina. It contains the graves of notable people, including Eva Perón, presidents of Argentina, Nobel Prize winners, ...

was the occasion of a mass demonstration. In December, during a meeting of the national convention of the UCR, a joint uprising by the military and politicians broke loose in Santa Fe, Rosario

Rosario () is the largest city in the central Argentine province of Santa Fe. The city is located northwest of Buenos Aires, on the west bank of the Paraná River. Rosario is the third-most populous city in the country, and is also the most p ...

, and Paso de los Libres

Paso de los Libres is a city in the east of the province of Corrientes in the Argentine Mesopotamia. It had about 44,000 inhabitants at the , and is the head town of the department of the same name.

The city lies on the right-hand (western) sh ...

. José Benjamin Abalos, who was Yrigoyen's former Minister, and Colonel Roberto Bosch were arrested during the uprising and the organizers and leaders of the party were imprisoned at Martín García. Former President Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear was exiled by the government, while others were detained in the penitentiary in Ushuaia

Ushuaia ( , ) is the capital of Tierra del Fuego, Antártida e Islas del Atlántico Sur Province, Argentina. With a population of nearly 75,000 and a location below the 54th parallel south latitude, Ushuaia claims the title of world's souther ...

.

In 1935, former president Alvear was allowed to return from exile as part of a gentlemen's agreement with Justo, with Alvear promising there would be no more violent rebellions in exchange for Justo promising an end to fraudulent elections. Thus Alvear took on leadership of the UCR party, vowing that the UCR would once again take part in elections and to continue the fight against fraudulent practices. That same year, once again amid accusations of fraud, the Justo administration managed to secure the victory of its candidate Manuel Fresco

Manuel Antonio Justo Pastor Pascual Fresco (June 3, 1888 in Navarro, Buenos Aires – November 17, 1971 in Buenos Aires) was an Argentine doctor and Politician, national deputy and governor of Buenos Aires Province between 1936 and 1940 for the ...

for governor of the Province of Buenos Aires, but it could not avoid the UCR victory of Amadeo Sabattini

Amadeo Tomás Sabattini (May 29, 1892 – February 29, 1960) was an Argentine politician. He served as Governor of Córdoba from May 17, 1936, to May 17, 1940.

Sabattini was born in Buenos Aires to immigrant parents: His mother was Uruguayan, ...

for governor in Córdoba, despite bloody incidents that aimed at disrupting the election. Meanwhile, the province of Santa Fe, under the leadership of opposition Democratic Progressive Party

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is a Taiwanese nationalist and centre-left political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). Controlling both the Republic of China presidency and the unicameral Legislative Yuan, it is the majorit ...

governor Luciano Molinas, was the subject of a federal intervention

Federal intervention () is a power attributed to the federal government of Argentina, by which it takes control of a province in certain extreme cases. Intervention is declared by the President with the assent of the National Congress. Article 6 o ...

by the national government.

In 1937, presidential elections

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The pre ...

were to be held. Alvear, together with his running mate Enrique Mosca campaigned across the country, vowing that "not even fraud could defeat them". Meanwhile, the ruling Concordancia party, nominated lawyer Roberto M. Ortiz, from the dissident anti-Yrigoyen UCR faction, as presidential candidate, with conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

lawmaker Ramón Castillo

Ramón Antonio Castillo Barrionuevo (November 20, 1873 – October 12, 1944) was a conservative Argentine politician who served as President of Argentina from June 27, 1942 to June 4, 1943. He was a leading figure in the period known as ...

, as his running mate. The 1937 presidential elections were held in September. Completely flouting on his promise, Justo kept his political and security forces busy on election day. Amid widespread reports of intimidation, ballot stuffing and voter roll tampering (whereby, according to one observer, "democracy was extended to the hereafter"), Ortiz won the elections handily.

Argentina at the Beginning of World War II

Political Situation at the Beginning of World War II

At the beginning of World War Two, in 1939, Roberto María Ortiz was the

At the beginning of World War Two, in 1939, Roberto María Ortiz was the President of Argentina

The president of Argentina ( es, Presidente de Argentina), officially known as the president of the Argentine Nation ( es, Presidente de la Nación Argentina), is both head of state and head of government of Argentina. Under the national cons ...

. Despite winning the presidency by elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

that were widely recognized as fraudulent by both the government and the opposition, by 1939 the government of Ortiz

Ortiz () is a Spanish-language patronymic surname meaning "son of Orti". "Orti" seems to be disputed in meaning, deriving from either Basque, Latin ''fortis'' meaning "brave, strong", or Latin ''fortunius'' meaning "fortunate". Officials of the ...

had made democratic normalization a priority of its agenda. To achieve this aim, the Ortiz administration resorted to federal interventions, but in the opposite way that these had been used under Justo, intervening those provinces where governors had won by proven fraud (namely San Juan San Juan, Spanish for Saint John, may refer to:

Places Argentina

* San Juan Province, Argentina

* San Juan, Argentina, the capital of that province

* San Juan, Salta, a village in Iruya, Salta Province

* San Juan (Buenos Aires Underground), ...

, Santiago del Estero

Santiago del Estero (, Spanish for ''Saint-James-Upon-The-Lagoon'') is the capital of Santiago del Estero Province in northern Argentina. It has a population of 252,192 inhabitants, () making it the twelfth largest city in the country, with a surf ...

, Catamarca and Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires ( or ; ), officially the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires ( es, link=no, Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires), is the capital and primate city of Argentina. The city is located on the western shore of the Río de la Plata, on South ...

), while respecting the results and autonomy in those provinces with no irregularities, including those where elections had been won by the opposition UCR, such as the cases of Tucumán (October 1938 and March 1939) as well as Córdoba (March 1940). In 1940, legislative elections were held in a clean fashion, giving the opposition UCR a majority in Congress.Luna, Félix.(1985). "Roberto Marcelino Ortiz, reportaje a la Argentina opulenta". Buenos Aires: ed. Sudamericana This policy of democratic restoration would soon put the administration of Ortiz at odds with the more conservative factions of his own ruling Concordancia party, including conservative Vice-president Ramón Castillo

Ramón Antonio Castillo Barrionuevo (November 20, 1873 – October 12, 1944) was a conservative Argentine politician who served as President of Argentina from June 27, 1942 to June 4, 1943. He was a leading figure in the period known as ...

.

The opposition Radical Civic Union

The Radical Civic Union ( es, Unión Cívica Radical, UCR) is a centrist and social-liberal political party in Argentina. It has been ideologically heterogeneous, ranging from social liberalism to social democracy. The UCR is a member of the S ...

, in turn, was divided between FORJA, a political grouping that consisted of hardline supporters of deposed UCR president Hipólito Yrigoyen

Juan Hipólito del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús Yrigoyen (; 12 July 1852 – 3 July 1933) was an Argentine politician of the Radical Civic Union and two-time President of Argentina, who served his first term from 1916 to 1922 and his second ...

(who passed away in 1933) and opposed any form of cooperation with the government, and the majoritarian faction of the UCR under the official leadership of Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear, who, while also remaining in opposition to the government, soon adopted a more conciliary tone to the Ortiz

Ortiz () is a Spanish-language patronymic surname meaning "son of Orti". "Orti" seems to be disputed in meaning, deriving from either Basque, Latin ''fortis'' meaning "brave, strong", or Latin ''fortunius'' meaning "fortunate". Officials of the ...

administration as a result of these changes. The two other major parties, the Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of ...

and the liberal Democratic Progressive Party

The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is a Taiwanese nationalist and centre-left political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). Controlling both the Republic of China presidency and the unicameral Legislative Yuan, it is the majorit ...

would also remain in opposition to the government. Meanwhile, the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engel ...

, also staunchly opposed to the government, initially followed a policy of courting the trade unions, and gave priority to supporting the international stance of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

.

Economically, recovery from the Great Depression had been underway since 1933, but the beginning of the war resulted in changes to the Argentine economy, as imports from Europe were reduced. Thus began a process of import substitution industrialization

Import substitution industrialization (ISI) is a trade and economic policy that advocates replacing foreign imports with domestic production.''A Comprehensive Dictionary of Economics'' p.88, ed. Nelson Brian 2009. It is based on the premise that ...

, which had some antecedents during the Great Depression. This led to a process of internal migration as well, with people living in the countryside or in small villages moving to urban centers.

Beginning of World War II

At the beginning of the Second World War on 1 September 1939, the Argentine government proclaimed its neutrality in the conflict. On 3 September, the diplomatic representatives of the United Kingdom and France informed the Argentine government that their countries had entered a state of war againstNazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. Following the initial policies of other states in the Americas, the government of Ortiz

Ortiz () is a Spanish-language patronymic surname meaning "son of Orti". "Orti" seems to be disputed in meaning, deriving from either Basque, Latin ''fortis'' meaning "brave, strong", or Latin ''fortunius'' meaning "fortunate". Officials of the ...

issued a decree on 4 September 1939, declaring Argentine neutrality in the conflict. To enforce the observance of neutrality, on 14 September 1939, a second presidential decree was issued by Ortiz, creating a special commission integrated by representatives from each ministry, housed on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The enti ...

and chaired by a delegate from this ministry.

Battle of the River Plate

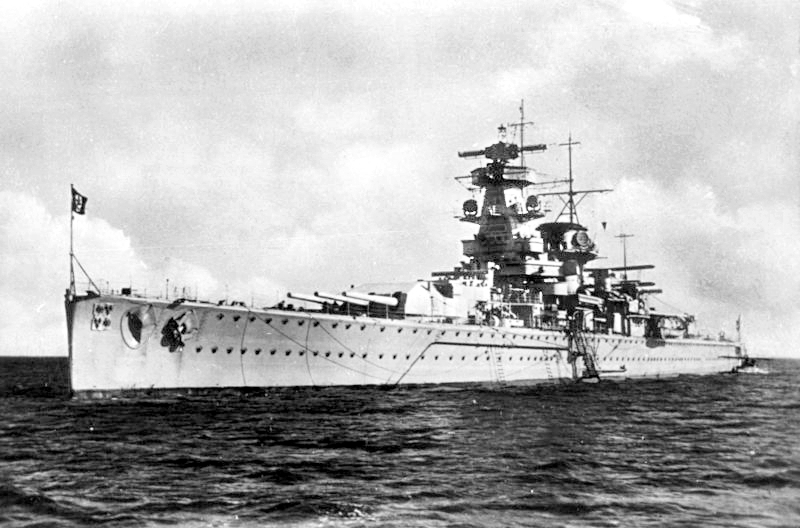

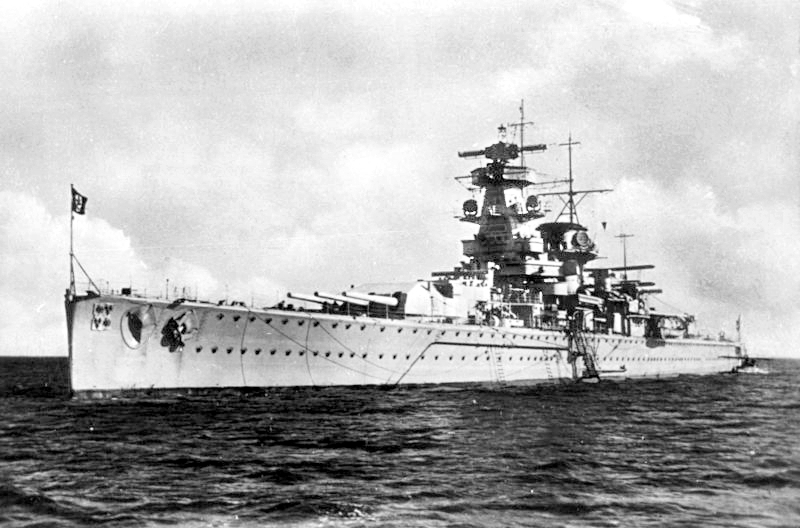

On 13 December 1939, the

On 13 December 1939, the Battle of the River Plate

The Battle of the River Plate was fought in the South Atlantic on 13 December 1939 as the first naval battle of the Second World War. The Kriegsmarine heavy cruiser , commanded by Captain Hans Langsdorff, engaged a Royal Navy squadron, command ...

took place, becoming the first naval engagement of World War II between British and German ships. Taking place in the territorial waters of Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

and close to Argentina, neither the Uruguayan nor the Argentine governments were involved in the battle. During this battle, the German pocket battleship Graf Spee was severely damaged by British ships on the waters of the River Plate estuary. Cornered, the German captain Hans Langsdorff ordered the scuttling of the ship, while the crew were taken under custody and interned by Uruguayan and Argentine authorities. While under custody, Hans Langsdorff would later commit suicide at the Immigrant's Hotel in Buenos Aires, while the crew was eventually released, a dozen of them taking residence in Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

and Uruguay

Uruguay (; ), officially the Oriental Republic of Uruguay ( es, República Oriental del Uruguay), is a country in South America. It shares borders with Argentina to its west and southwest and Brazil to its north and northeast; while bordering ...

.

Aborted attempt to join the Allies

In December 1939, partly as a consequence of theBattle of the River Plate

The Battle of the River Plate was fought in the South Atlantic on 13 December 1939 as the first naval battle of the Second World War. The Kriegsmarine heavy cruiser , commanded by Captain Hans Langsdorff, engaged a Royal Navy squadron, command ...

, the government of Ortiz

Ortiz () is a Spanish-language patronymic surname meaning "son of Orti". "Orti" seems to be disputed in meaning, deriving from either Basque, Latin ''fortis'' meaning "brave, strong", or Latin ''fortunius'' meaning "fortunate". Officials of the ...

came to the conclusion that the worldwide nature of the conflict would eventually make neutrality untenable and impossible to maintain. Thus, Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

José Maria Cantilo was tasked with drafting a proposal, under which Argentina, together with the United States and eventually other Latin American

Latin Americans ( es, Latinoamericanos; pt, Latino-americanos; ) are the citizens of Latin American countries (or people with cultural, ancestral or national origins in Latin America). Latin American countries and their diasporas are multi-e ...

states, would join the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

as "non-belligerent" states, offering economic and diplomatic support to the European Allies. In April 1940, Foreign Affairs Minister Cantilo made a visit to United States ambassador Normal Armour, presenting the Argentine proposal for the United States, Argentina and other Latin American states to join the war together as non-belligerent parties. However, the Argentine proposal suffered from bad timing, as then U.S. President, Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, was in the midst of a challenging and controversial re-election campaign for an unprecedented third term in office. To make things worse, on 12 May 1940, the Argentine proposal was leaked to the press, and was published nationwide by Argentine daily newspaper La Nacion, leading to much confusion in the country, and outrage among nationalist groups, who demanded Ortiz

Ortiz () is a Spanish-language patronymic surname meaning "son of Orti". "Orti" seems to be disputed in meaning, deriving from either Basque, Latin ''fortis'' meaning "brave, strong", or Latin ''fortunius'' meaning "fortunate". Officials of the ...

's resignation. On 13 May, the Argentine government issued a communique acknowledging the existence of the proposal, and on 18 May another communique was issued, clarifying that Argentina would continue to observe the "most strict neutrality" in the conflict.

The leak of this proposal at an early stage of the conflict, together with the perceived diplomatic snub, severely weakened the position of the Ortiz administration and of pro- Allied factions within the Argentine government, intensifying nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

sentiment and opposition to Ortiz in military circles.

Ortiz's resignation and growing divisions

From the beginning of his administration, Ortiz had been suffering from diabetes, and his health continued to deteriorate throughout his presidency. By 3 July 1940, after only two years in office, Ortiz had lost much of his

From the beginning of his administration, Ortiz had been suffering from diabetes, and his health continued to deteriorate throughout his presidency. By 3 July 1940, after only two years in office, Ortiz had lost much of his eyesight

Visual perception is the ability to interpret the surrounding environment through photopic vision (daytime vision), color vision, scotopic vision (night vision), and mesopic vision (twilight vision), using light in the visible spectrum reflect ...

, and thus he requested a temporary leave of absence from his duties as president, being replaced by conservative Vice-president Ramón S. Castillo, who became acting president. During Castillo's tenure, stances towards the war became more complex as the conflict developed. The main political parties, newspapers and intellectuals supported the Allies, yet Castillo maintained neutrality. Meanwhile, Ortiz was in leave of absence and unable to serve as president, but he did not resign from office. The position of Argentina vis-à-vis the war generated disputes between them, with Castillo often prevailing.

Despite several treatments from Argentine ophthalmologists

Ophthalmology ( ) is a surgical subspecialty within medicine that deals with the diagnosis and treatment of eye disorders.

An ophthalmologist is a physician who undergoes subspecialty training in medical and surgical eye care. Following a medic ...

, and the kind gesture of support from President Roosevelt

Roosevelt may refer to:

*Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919), 26th U.S. president

* Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945), 32nd U.S. president

Businesses and organisations

* Roosevelt Hotel (disambiguation)

* Roosevelt & Son, a merchant bank

* Rooseve ...

who sent one of the best ophthalmologists from the United States to provide treatment as well, Ortiz's health got progressively worse, until he finally lost his eyesight completely. On 27 June 1942 he would present his full resignation to the presidency, and vice-president Castillo took office as president to fulfill the remaining two years of his mandate. Only 18 days after his resignation, Ortiz

Ortiz () is a Spanish-language patronymic surname meaning "son of Orti". "Orti" seems to be disputed in meaning, deriving from either Basque, Latin ''fortis'' meaning "brave, strong", or Latin ''fortunius'' meaning "fortunate". Officials of the ...

passed away.

Meanwhile, among civil society and the main political parties, support for the entry of Argentina into the war on the Allied side continued to grow and became widespread as the war progressed. The main advocacy organization for entry into the Allied side was Acción Argentina, founded on 5 June 1940, from a proposal of the Socialist Party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of ...

. The initial manifesto of Acción Argentina was drafted by former president Marcelo T. de Alvear

Máximo Marcelo Torcuato de Alvear Pacheco (4 October 1868 – 23 March 1942), was an Argentine lawyer and politician, who served as President of Argentina, president of Argentina between from 1922 to 1928.

His period of government coincid ...

, and leading members of the organization included major intellectuals, journalists, artists and politicians from a wide ideological spectrum, among them Alicia Moreau de Justo

Alicia Moreau de Justo (October 11, 1885 – May 12, 1986) was an Argentine physician, politician, pacifist and human rights activist. She was a leading figure in feminism and socialism in Argentina. Since the beginning of the 20th century, she ...

, Américo Ghioldi

Américo Ghioldi (May 23, 1899 – December 21, 1985) was an Argentine educator, publisher and prominent Socialist politician.

Life and times

Ghioldi was born and raised in Buenos Aires. He went to become a Professor of Exact Sciences at the Nat ...

, José Aguirre Cámara, Mauricio Yadarola, Rodolfo Fitte, Rafael Pividal, Raúl C. Monsegur, Federico Pinedo, Jorge Bullrich, Alejandro Ceballos, Julio A. Noble, Victoria Ocampo, Emilio Ravignani, Nicolás Repetto

Nicolás Repetto (21 October 1871 – 29 November 1965) was an Argentine physician and leader of the Socialist Party of Argentina.

Biography

Nicolás Repetto was born in Buenos Aires in 1871 and enrolled at the prestigious Colegio Nacional de Bu ...

, Mariano Villar Sáenz Peña and Juan Valmaggia. The organization grew to encompass 300 chapters across the country, and organized political meetings and protests, propaganda posters, leaflets, and even direct actions attempting to expose Nazi activity in the country.

On the side of those opposing entry into the war, FORJA was the only political party that supported neutrality throughout the war, seeing it as an opportunity to get rid of what they considered British meddling with the Argentine economy. Starting in 1940, the FORJA faction led by Dellepiane and Del Mazo had drifted away from the organization and rejoined the UCR, while FORJA itself adopted more nationalistic and left-wing ideas, under the leadership of Arturo Jauretche.Scenna, Miguel Ángel (1983). "FORJA, una aventura argentina (De Yrigoyen a Perón)". Buenos Aires:de Belgrano. ISBN 950-577-057-8 Nationalistic sectors of the army also promoted neutrality as a way to oppose the United Kingdom and its economic influence. Notably during this time, a plan was made by the Naval War College to invade the

On the side of those opposing entry into the war, FORJA was the only political party that supported neutrality throughout the war, seeing it as an opportunity to get rid of what they considered British meddling with the Argentine economy. Starting in 1940, the FORJA faction led by Dellepiane and Del Mazo had drifted away from the organization and rejoined the UCR, while FORJA itself adopted more nationalistic and left-wing ideas, under the leadership of Arturo Jauretche.Scenna, Miguel Ángel (1983). "FORJA, una aventura argentina (De Yrigoyen a Perón)". Buenos Aires:de Belgrano. ISBN 950-577-057-8 Nationalistic sectors of the army also promoted neutrality as a way to oppose the United Kingdom and its economic influence. Notably during this time, a plan was made by the Naval War College to invade the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

, but was never put into operation. On the other hand, the newspaper ''El Pampero'', financed by the German embassy, actively supported Hitler.

Within the Argentine Army

The Argentine Army ( es, Ejército Argentino, EA) is the Army, land force branch of the Armed Forces of the Argentine Republic and the senior military service of Argentina. Under the Argentine Constitution, the president of Argentina is the comman ...

, Germanophile

A Germanophile, Teutonophile, or Teutophile is a person who is fond of German culture, German people and Germany in general, or who exhibits German patriotism in spite of not being either an ethnic German or a German citizen. The love of the ''Ge ...

sentiments were strong among many officers, an influence that predated both world wars, having been steadily growing since 1904. Generally, it did not involve a rejection of democracy but rather an admiration of German military history, which combined with an intense Argentine nationalism

Argentine nationalism refers to the nationalism of Argentine people and Argentine culture. It surged during the War of Independence and the Civil Wars, and strengthened during the 1880s.

There were waves of renewed interest in nationalism in resp ...

influenced the main stance of the army towards the war: maintaining neutrality. The arguments in favor ranged from support for the Argentine military tradition (as the country had been neutral during both World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and the War of the Pacific

The War of the Pacific ( es, link=no, Guerra del Pacífico), also known as the Saltpeter War ( es, link=no, Guerra del salitre) and by multiple other names, was a war between Chile and a Bolivian–Peruvian alliance from 1879 to 1884. Fought ...

), to a rejection of foreign attempts to coerce Argentina into joining a war perceived as a conflict between foreign countries with no Argentine interests at stake, to outright Anglophobia.Galasso, p. 118 Though only a handful of military leaders were actually supporters of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

, and pro-Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

positions in the minority, their true influence inside the army remains difficult to ascertain, as their advocates generally disguised themselves and adopted the arguments of the neutralist camp.

Meanwhile, the Communist Party aligned itself with the diplomatic policies of the Soviet Union. As a result, it supported neutrality and opposed the British influence in Argentina during the early stages of the war, in line with the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

. The launching of Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

and the consequent Soviet entry in the war changed that attitude. Some Trotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a ...

s promoted the fight against the Third Reich as an early step of an international class struggle

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The form ...

.

As for the Castillo administration, there are a number of interpretations for his reasons for staying neutral. One such perspective focuses on the Argentine tradition of neutrality. Others see Castillo as a nationalist, not being influenced by the power structure in Buenos Aires (since he was from Catamarca), so that, with the support of the army, he could simply defy the pressure to join the Allies. A similar interpretation considers instead that Castillo simply had no power to go against the wishes of the army, and if he declared war he would be deposed in a military coup

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

. A third point of view considers that the United States was the sole promoter of Argentina's entry into the war, whereas the United Kingdom benefited from Argentine neutrality as it was a major supplier of beef and wheat. This, however, fails to acknowledge the constant requests to declare war from Anglophile

An Anglophile is a person who admires or loves England, its people, its culture, its language, and/or its various accents.

Etymology

The word is derived from the Latin word ''Anglii'' and Ancient Greek word φίλος ''philos'', meaning "fr ...

factions. Most likely, it was a combination of the desires of the British diplomacy and the Argentine army, which prevailed over the pro-war factions.

Socialist deputy Enrique Dickmann created a commission in the National Congress ''National Congress'' is a term used in the names of various political parties and legislatures .

Political parties

*Ethiopia: Oromo National Congress

*Guyana: People's National Congress (Guyana)

*India: Indian National Congress

*Iraq: Iraqi Nati ...

to investigate a rumored German attempt to seize Patagonia

Patagonia () refers to a geographical region that encompasses the southern end of South America, governed by Argentina and Chile. The region comprises the southern section of the Andes Mountains with lakes, fjords, temperate rainforests, and g ...

and then conquer the rest of the country. The conservative deputy Videla Dorna claimed that the real risk was a similar Communist invasion, and FORJA believed that a German invasion was only a potential risk, whereas British dominance of the Argentine economy was a reality.

A diplomatic mission by the British Lord Willingdon

Freeman Freeman-Thomas, 1st Marquess of Willingdon (12 September 1866 – 12 August 1941), was a British Liberal politician and administrator who served as Governor General of Canada, the 13th since Canadian Confederation, and as Viceroy and ...

arranged commercial treaties whereby Argentina sent thousands of cattle to Britain at no charge, decorated with the Argentine colours and with the phrase "good luck" written on them. ''El Pampero'' and FORJA criticised this arrangement, with Arturo Jauretche and Homero Manzi

Homero Nicolás Manzione Prestera, better known as Homero Manzi (November 1, 1907 – May 3, 1951) was an Argentine tango lyricist, author of various famous tangos.

He was born on November 1 of 1907 in Añatuya (province of Santiago del Estero ...

proclaiming "these are the goods that are not being sent to our needy compatriots in the provinces".

Events following the attack on Pearl Harbour

The situation changed dramatically after the Japanese

The situation changed dramatically after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

and the subsequent American declaration of war upon Japan. During the Third Consultation Meeting of Foreign Ministers of the Americas (1942 Rio Conference

Pan-Americanism is a movement that seeks to create, encourage, and organize relationships, associations and cooperation among the states of the Americas, through diplomatic, political, economic, and social means.

History

Following the indepen ...

), the United States of America tried to get every Latin American country to join the Allies to generate a continent-wide resistance to the Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

. But the government of Castillo, through foreign minister Enrique Ruiz Guiñazu, opposed the American proposal. From that moment onwards, relations between both countries worsened, and American pressure for Argentine entry into the war begun to increase.

Castillo did, however, declare a state of emergency after the attack on Pearl Harbor.Mendelevich, p. 142

Military plots

Castillo's term was due to end in 1944. Initially, it was arranged that Agustín Pedro Justo would run for president for a second time, but after his unexpected death in 1943 Castillo was forced to seek another candidate, finally settling onRobustiano Patrón Costas

Robustiano Patrón Costas (August 5, 1878 – September 24, 1965) was an Argentine politician and businessman who served as Governor of Salta Province. He led the National Democratic Party.

Biography

Patrón Costas was born in Salta to Fra ...

. The army, however, was neither willing to support the electoral fraud that would be necessary to secure Costas's victory, nor to continue conservative policies, nor to risk Costas breaking neutrality. A number of generals reacted by creating a secret organization called the United Officers' Group (GOU) to oust Castillo from power. Future president Juan Perón

Juan Domingo Perón (, , ; 8 October 1895 – 1 July 1974) was an Argentine Army general and politician. After serving in several government positions, including Minister of Labour and Vice President of a military dictatorship, he was elected ...

was a member of this group but did not support an early coup, recommending instead to postpone the overthrowing of the government until the plotters had developed a plan to make necessary reforms. The coup was to take place close to the elections, should the electoral fraud have been confirmed, but it was instead carried out earlier in response rumors of the possible sacking of the minister of war, Pedro Pablo Ramírez.

It is not known for certain whether Patrón Costas would have maintained neutrality or not. But some declarations of support to Britain and his ties with pro-allied factions suggest that had he become president he would have declared war.

The military coup that deposed Castillo took place on 4 June 1943. It is considered the end of the ''Infamous Decade'' and the starting point of the self-styled ''Revolution of '43

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

''. Arturo Rawson

Arturo Rawson (June 4, 1885 – October 8, 1952) was an Argentine politician, military officer, and the provisional President of the Republic from June 4, 1943, to June 6, 1943.

His coup started a series which culminated in the accession to po ...

took power as ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with '' de jure'' ("by l ...

'' president. The nature of the coup was confusing during its first days: German embassy officials burned their documentation fearing a pro-Allied coup, while the United States embassy considered it a pro-Axis coup.

Rawson met with a delegate from the British embassy on 5 June and promised that he would break relations with the Axis powers and declare war within 72 hours. This turn of events enraged the United Officers' Group, as did Rawson's choices for his cabinet. A new coup took place, replacing Rawson with Pedro Pablo Ramírez. Thus, Rawson became the shortest non-interim president in Argentine history.

One of the first measures of the new Ramírez government was to declare Acción Argentina and its pro-Allied advocacy activities illegal.

1943 Military Coup

The new government proceeded with both progressive and reactionary policies. Maximum prices were established for popular products, rents were reduced, the privileges of the Chadopyff factory were annulled and hospital fees were abolished. On the other hand, the authorities intervened trade unions, closed the Communist newspaper ''La Hora'' and imposed religious education at schools.

The new government proceeded with both progressive and reactionary policies. Maximum prices were established for popular products, rents were reduced, the privileges of the Chadopyff factory were annulled and hospital fees were abolished. On the other hand, the authorities intervened trade unions, closed the Communist newspaper ''La Hora'' and imposed religious education at schools. Juan Perón

Juan Domingo Perón (, , ; 8 October 1895 – 1 July 1974) was an Argentine Army general and politician. After serving in several government positions, including Minister of Labour and Vice President of a military dictatorship, he was elected ...

and Edelmiro Julián Farrell, hailing from the Ministry of War, fostered better relations between the state and the unions.

As previously discussed, the Communist Party had aligned itself with the diplomatic policies of the Soviet Union. Following the launching of Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named afte ...

and the consequent Soviet entry in the war, the Communists became pro-war and halted its support for further labour strikes against British factories located in Argentina. This switch redirected workers' support from the Communist Party to Perón and the new government.

As a result, the Communist Party turned against the government, which it viewed as pro-Nazi. Perón countered complaints by declaring that "The excuses they seek are very well known. They say we are 'nazis', I declare we are as far from Nazism as from any other foreign ideology. We are only Argentines and want, above all, the common good for Argentines. We do not want any more electoral fraud

Electoral fraud, sometimes referred to as election manipulation, voter fraud or vote rigging, involves illegal interference with the process of an election, either by increasing the vote share of a favored candidate, depressing the vote share of ...

, nor more lies. We do not want that those who do not work live from those who do".

The government held diplomatic discussions with the United States, with Argentina requesting aircraft, fuel, ships and military hardware. The Argentine

The government held diplomatic discussions with the United States, with Argentina requesting aircraft, fuel, ships and military hardware. The Argentine Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

Segundo Storni argued that, although Argentina refrained from participating in the war, it remained closer to the Allies, sending them food, and that up to then the Axis powers had not taken action against the country to justify a declaration of war. The United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull (October 2, 1871July 23, 1955) was an American politician from Tennessee and the longest-serving U.S. Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years (1933–1944) in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ...

replied that Argentina was the only Latin American country to not have broken relations with the Axis, that Argentine food was sold at lucrative return, and that United States military hardware was intended for countries already at war, some of which were facing more severe fuel shortages than was Argentina. Storni resigned after this rejection. The United States took further measures to increase pressure on Argentina. All Argentine companies suspected of having ties with the Axis powers were blacklisted and boycotted, and the supply of newsprint was limited to pro-Allied newspapers. American exports of electronic appliances, chemical substances and oil production infrastructure were halted. The properties of forty-four Argentine companies were seized, and scheduled loans were halted. Hull wanted to weaken the Argentine government or force its resignation. Torn between diplomatic and economic pressure as opposed to an open declaration of war against Argentina, he opted for the former to avoid disrupting the supply of food to Britain. Nevertheless, he also saw the situation as a chance for the United States to have a greater influence over Argentina than Britain.

The United States also threatened to accuse Argentina of being involved with the coup of Gualberto Villarroel

Gualberto Villarroel López (15 December 1908 – 21 July 1946) was a Bolivian military officer who served as the 39th president of Bolivia from 1943 to 1946. A reformist, sometimes compared with Argentina's Juan Perón, he is nonetheless ...

in Bolivia, and a plot to receive weapons from Germany after the allied refusal, to face the possible threat of invasion either by the United States itself or Brazil acting on their behalf. However, it would be unlikely that Germany would provide such weapons, given their fragile situation in 1944. Ramírez called a new meeting of the GOU, and it was agreed to break diplomatic relations with the Axis powers (albeit without yet a declaration of war) on 26 January 1944.

The break in relations generated unrest within the military, and Ramírez considered removing both the influential Farrell and Perón from the government. However, their faction discovered Ramírez's plan. They broke up the United Officers' Group, to avoid letting the military loyal to Ramírez know they were aware of his plot, and then initiated a coup against him. Edelmiro Julián Farrell became then the new president of Argentina on 24 February.

The United States refused to recognise Farrell as long as he maintained the neutralist policy, which was ratified by Farrell on 2 March, and the United States broke relations with Argentina two days later. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

complained about the harsh policy of the United States against Argentina, pointing out that Argentine supplies were vital to the British war effort and that removing their diplomatic presence from the country would even force Argentina to seek Axis protection. British diplomacy sought to guarantee the supply of Argentine food by signing a treaty covering it, while US diplomatic policy sought to prevent such a treaty. Hull ordered the confiscation of Argentine goods in the United States, suspension of foreign trade with her, prohibited US ships from mooring at Argentine ports, and denounced Argentina as the "nazi headquarters in the Western hemisphere".

According to historian Norberto Galasso

Norberto Galasso (born 28 July 1936 in Buenos Aires) is a historian and essayist from Argentina, who wrote numerous books related about the history of Argentina. His career as historian spans nearly 40 years.

He studied economy in the University o ...

, at this point Washington held talks with Brazil, exploring plans for military intervention. The Brazilian ambassador in Washington is said to have claimed that Buenos Aires could be completely destroyed by the Brazilian Air Force, allowing Argentina to be dominated without the open intervention of the United States, who would support Brazil by providing ships and bombs.

End of the War

The

The Liberation of Paris

The liberation of Paris (french: Libération de Paris) was a military battle that took place during World War II from 19 August 1944 until the German garrison surrendered the French capital on 25 August 1944. Paris had been occupied by Nazi Ger ...

in August 1944 gave new hopes to the pro-Allied factions in Argentina, who saw it as an omen of the possible fall of the Argentine government and called for new elections. The demonstrations in support of Paris soon turned into protests against the government, leading to incidents with the police. It was rumored that some Argentine politicians in Uruguay would create a government in exile

A government in exile (abbreviated as GiE) is a political group that claims to be a country or semi-sovereign state's legitimate government, but is unable to exercise legal power and instead resides in a foreign country. Governments in exile ...

, but the project never came to fruition. President Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

supported Hull's claims about Argentina with similar statements. He also cited Churchill when he stated that history would judge all nations for their role in the war, both belligerents and neutrals.

By early 1945, World War II was nearing its end. The Red Army had captured Warsaw and was closing in on East Prussia, and Berlin itself was under attack. Allied victory was imminent. Perón, the strong man of the Argentine government, foresaw that the Allies would dominate international politics for decades and concluded that although Argentina had successfully resisted the pressure to force it to join the war, remaining neutral until the end of the war would force the country into isolationism

Isolationism is a political philosophy advocating a national foreign policy that opposes involvement in the political affairs, and especially the wars, of other countries. Thus, isolationism fundamentally advocates neutrality and opposes entangl ...

at best or bring about a military attack from the soon to be victorious powers.

Negotiations were eased by the departure of Hull as Secretary of State, replaced by Edward Stettinius Jr.

Edward Reilly Stettinius Jr. (October 22, 1900 – October 31, 1949) was an American businessman who served as United States Secretary of State under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman from 1944 to 1945, and as U.S. Ambassador ...

, who demanded that Argentina hold free elections, declare war against the Axis powers, eradicate all Nazi presence in the country and give its complete cooperation to international organizations. Perón agreed, and German organizations were curtailed, pro-Nazi manifestations were banned, and German goods were seized. The Argentine merchant navy was instructed to ignore the German blockade. These measures eased relations with the United States. When the Allies advanced into Frankfurt, Argentina finally formalized the negotiations. On 27 March, per Decree 6945, Argentina declared war on Japan and, by extension, on Germany, an ally of Japan. FORJA, one of the main proponents of neutrality, distanced itself from the government, but eventually Arturo Jauretche would come to support the government's change of position a year later. Jauretche reasoned that the United States opposed Argentina because of its perceived Nazism by refusing to declare war although neutrality was based instead on Argentine interests; which were no longer at stake with a declaration of war when the country would not actually join the conflict. Jauretche came to believe that Perón's pragmatism was better for the country than his own idealistic perspective of keeping a neutral stance to the end of the war.

A few days later, on 10 April, the United Kingdom, France, the United States, and the other Latin American countries restored diplomatic relations with Argentina. Still, diplomatic hostility against Argentina from the United States resurfaced after the unexpected death of Roosevelt, who was succeeded by Harry S. Truman. Ambassador Spruille Braden

Spruille Braden ( ; March 13, 1894 – January 10, 1978) was an American diplomat, businessman, lobbyist, and member of the Council on Foreign Relations. He served as the ambassador to various Latin American countries, and as Assistant Secretary ...

would organize opposition to the government of Farrell and Perón.

The final Axis defeat in the European Theatre of World War II

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II. It saw heavy fighting across Europe for almost six years, starting with Germany's invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 and ending with the ...

took place a month later and was greeted with demonstrations of joy in Buenos Aires. Similar demonstrations took place in August, after the surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Na ...

, bringing World War II to its final end. Farrell lifted the state of emergency declared by Castillo after the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor.

Argentines in World War II

During World War II, 4,000 Argentines served with all three

During World War II, 4,000 Argentines served with all three British armed services

The British Armed Forces, also known as His Majesty's Armed Forces, are the military forces responsible for the defence of the United Kingdom, its Overseas Territories and the Crown Dependencies. They also promote the UK's wider interests, su ...

, even though Argentina was officially a neutral country during the war. Over 600 Argentine volunteers served with both the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

and the Royal Canadian Air Force