Applications of the Stirling engine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Applications of the

Applications of the

NASA's Stirling MOD 1 powered engineering vehicles were built in partnership with the

NASA's Stirling MOD 1 powered engineering vehicles were built in partnership with the

Placed at the focus of a parabolic mirror, a Stirling engine can convert

Placed at the focus of a parabolic mirror, a Stirling engine can convert

A low temperature difference (LTD, or Low Delta T (LDT)) Stirling engine will run on any low-temperature differential, for example, the difference between the palm of a hand and room temperature, or room temperature and an ice cube. A record of only 0.5 °C temperature differential was achieved in 1990. Usually they are designed in a gamma configuration for simplicity, and without a regenerator, although some have slits in the displacer typically made of foam for partial regeneration. They are typically unpressurized, running at pressure close to 1

A low temperature difference (LTD, or Low Delta T (LDT)) Stirling engine will run on any low-temperature differential, for example, the difference between the palm of a hand and room temperature, or room temperature and an ice cube. A record of only 0.5 °C temperature differential was achieved in 1990. Usually they are designed in a gamma configuration for simplicity, and without a regenerator, although some have slits in the displacer typically made of foam for partial regeneration. They are typically unpressurized, running at pressure close to 1

Applications of the

Applications of the Stirling engine

A Stirling engine is a heat engine that is operated by the cyclic compression and expansion of air or other gas (the ''working fluid'') between different temperatures, resulting in a net conversion of heat energy to mechanical work.

More specif ...

range from mechanical propulsion to heating and cooling to electrical generation systems. A Stirling engine is a heat engine

In thermodynamics and engineering, a heat engine is a system that converts heat to mechanical energy, which can then be used to do mechanical work. It does this by bringing a working substance from a higher state temperature to a lower state ...

operating by cyclic compression and expansion of air or other gas, the "working fluid

For fluid power, a working fluid is a gas or liquid that primarily transfers force, motion, or mechanical energy. In hydraulics, water or hydraulic fluid transfers force between hydraulic components such as hydraulic pumps, hydraulic cylinders, a ...

", at different temperature levels such that there is a net conversion of heat

In thermodynamics, heat is defined as the form of energy crossing the boundary of a thermodynamic system by virtue of a temperature difference across the boundary. A thermodynamic system does not ''contain'' heat. Nevertheless, the term is al ...

to mechanical work

Work may refer to:

* Work (human activity), intentional activity people perform to support themselves, others, or the community

** Manual labour, physical work done by humans

** House work, housework, or homemaking

** Working animal, an animal tr ...

. The Stirling cycle

The Stirling cycle is a thermodynamic cycle that describes the general class of Stirling devices. This includes the original Stirling engine that was invented, developed and patented in 1816 by Robert Stirling with help from his brother, an en ...

heat engine can also be driven in reverse, using a mechanical energy input to drive heat transfer in a reversed direction (i.e. a heat pump, or refrigerator).

There are several design configurations for Stirling engines that can be built (many of which require rotary or sliding seals) which can introduce difficult tradeoffs between friction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other. There are several types of friction:

*Dry friction is a force that opposes the relative lateral motion of t ...

al losses and refrigerant

A refrigerant is a working fluid used in the refrigeration cycle of air conditioning systems and heat pumps where in most cases they undergo a repeated phase transition from a liquid to a gas and back again. Refrigerants are heavily regulated du ...

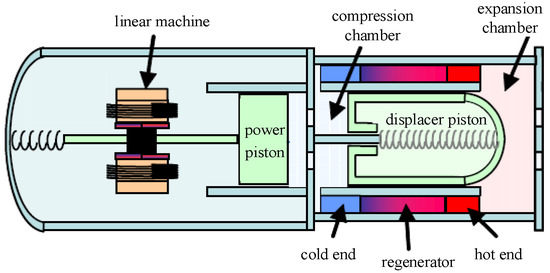

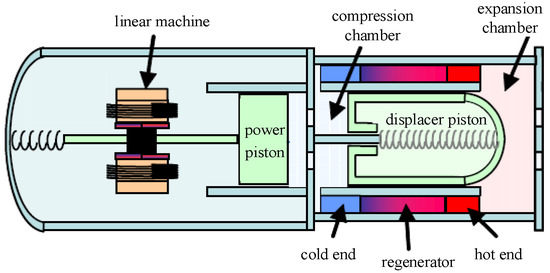

leakage. A free-piston variant of the Stirling engine can be built, which can be completely hermetically sealed, reducing friction losses and completely eliminating refrigerant leakage. For example, a Free Piston Stirling Cooler (FPSC) can convert an electrical energy input into a practical heat pump effect, used for high-efficiency portable refrigerators and freezers. Conversely, a free-piston electrical generator could be built, converting a heat flow into mechanical energy, and then into electricity. In both cases, energy is usually converted from/to electrical energy using magnetic fields in a way that avoids compromising the hermetic seal.

Mechanical output and propulsion

Automotive engines

It is often claimed that the Stirling engine has too low a power/weight ratio, too high a cost, and too long a starting time for automotive applications. They also have complex and expensive heat exchangers. A Stirling cooler must reject twice as much heat as anOtto engine

The Otto engine was a large stationary single-cylinder internal combustion four-stroke engine designed by the German Nicolaus Otto. It was a low-RPM machine, and only fired every other stroke due to the Otto cycle, also designed by Otto.

Types ...

or Diesel engine

The diesel engine, named after Rudolf Diesel, is an internal combustion engine in which ignition of the fuel is caused by the elevated temperature of the air in the cylinder due to mechanical compression; thus, the diesel engine is a so-cal ...

radiator. The heater must be made of stainless steel, exotic alloy, or ceramic to support high heating temperatures needed for high power density, and to contain hydrogen gas that is often used in automotive Stirlings to maximize power. The main difficulties involved in using the Stirling engine in an automotive application are startup time, acceleration response, shutdown time, and weight, not all of which have ready-made solutions.

However, a modified Stirling engine has been introduced that uses concepts taken from a patented internal-combustion engine with a sidewall combustion chamber (US patent 7,387,093) that promises to overcome the deficient power-density and specific-power problems, as well as the slow acceleration-response problem inherent in all Stirling engines. It could be possible to use these in co-generation systems that use waste heat from a conventional piston or gas turbine engine's exhaust and use this either to power the ancillaries (e.g.: the alternator) or even as a turbo-compound

A turbo-compound engine is a reciprocating engine that employs a turbine to recover energy from the exhaust gases. Instead of using that energy to drive a turbocharger as found in many high-power aircraft engines, the energy is instead sent to ...

system that adds power and torque to the crankshaft.

Automobiles exclusively powered by Stirling engines were developed in test projects by NASA, as well as earlier projects by the Ford Motor Company

Ford Motor Company (commonly known as Ford) is an American multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Dearborn, Michigan, United States. It was founded by Henry Ford and incorporated on June 16, 1903. The company sells automobile ...

using engines provided by Philips

Koninklijke Philips N.V. (), commonly shortened to Philips, is a Dutch multinational conglomerate corporation that was founded in Eindhoven in 1891. Since 1997, it has been mostly headquartered in Amsterdam, though the Benelux headquarters i ...

, and by American Motors Corporation

American Motors Corporation (AMC; commonly referred to as American Motors) was an American automobile manufacturing company formed by the merger of Nash-Kelvinator Corporation and Hudson Motor Car Company on May 1, 1954. At the time, it was the ...

(AMC) with several cars equipped with units from Sweden's United Stirling built under a license from Philips. The NASA vehicle test projects were designed by contractors and designated MOD I and MOD II.

NASA's Stirling MOD 1 powered engineering vehicles were built in partnership with the

NASA's Stirling MOD 1 powered engineering vehicles were built in partnership with the United States Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy (DOE) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government that oversees U.S. national energy policy and manages the research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the United States ...

(DOE) and NASA, under contract by AMC's AM General

AM General is an American heavy vehicle and contract automotive manufacturer based in South Bend, Indiana. It is best known for the civilian Hummer and the military Humvee that are assembled in Mishawaka, Indiana. For a relatively brief period, 1 ...

to develop and demonstrate practical alternatives for standard engines. The United Stirling AB's P-40 powered AMC Spirit

The AMC Spirit is a subcompact marketed by American Motors Corporation (AMC) from 1979 until 1983 as a restyled replacement for the Gremlin. The Spirit shared the Gremlin's platform and was offered in two hatchback variations, each with two do ...

was tested extensively for over and achieved average fuel efficiency up to . A 1980 4-door liftback VAM Lerma was also converted to United Stirling P-40 power to demonstrate the Stirling engine to the public and to promote the U.S. government's alternative engine program.

Tests conducted with the 1979 AMC Spirit, as well as a 1977 Opel

Opel Automobile GmbH (), usually shortened to Opel, is a German automobile manufacturer which has been a subsidiary of Stellantis since 16 January 2021. It was owned by the American automaker General Motors from 1929 until 2017 and the PSA Grou ...

and a 1980 AMC Concord

The AMC Concord is a compact car manufactured and marketed by the American Motors Corporation for model years 1978–1983. The Concord was essentially a revision of the AMC Hornet that was discontinued after 1977, but more luxurious, quieter, ro ...

, revealed the Stirling engines "could be developed into an automotive power train for passenger vehicles and that it could produce favorable results." However, progress was achieved with equal-power spark-ignition engines since 1977, and the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) requirements that were to be achieved by automobiles sold in the U.S. were being increased. Moreover, the Stirling engine design continued to exhibit a shortfall in fuel efficiency There were also two major drawbacks for consumers using the Stirling engines: first was the time needed to warm up – because most drivers do not like to wait to start driving; and second was the difficulty in changing the engine's speed – thus limiting driving flexibility on the road and traffic. The process of auto manufacturers converting their existing facilities and tooling for the mass production

Mass production, also known as flow production or continuous production, is the production of substantial amounts of standardized products in a constant flow, including and especially on assembly lines. Together with job production and batc ...

of a completely new design and type of powerplant was also questioned.

The MOD II project in 1980 produced one of the most efficient automotive engines ever made. The engine reached a peak thermal efficiency

In thermodynamics, the thermal efficiency (\eta_) is a dimensionless performance measure of a device that uses thermal energy, such as an internal combustion engine, steam turbine, steam engine, boiler, furnace, refrigerator, ACs etc.

For a h ...

of 38.5%, compared to a modern spark-ignition (gasoline) engine, which has a peak efficiency of 20-25%. The Mod II project replaced the normal spark-ignition engine in a 1985 4-door Chevrolet Celebrity

The Chevrolet Celebrity is a mid-size automobile that was produced by the Chevrolet division of General Motors from the 1982 to 1990 model years. Replacing the Malibu, the Celebrity was initially slotted between the Citation and the Impala wit ...

notchback

A notchback is a design of a car with the rearmost section that is distinct from the passenger compartment and where the back of the passenger compartment is at an angle to the top of what is typically the rear baggage compartment. Notchback cars ...

. In the 1986 MOD II Design Report (Appendix A) the results showed that highway gas mileage was increased from and achieved an urban range of with no change in vehicle gross weight. Startup time in the NASA vehicle was a maximum of 30 seconds, while Ford's research vehicle used an internal electric heater to quickly start the engine, giving a start time of only a few seconds. The high torque output of the Stirling engine at low speed eliminated the need for a torque converter in the transmission resulting in decreased weight and transmission drivetrain losses negating somewhat the weight disadvantage of the Stirling in auto use. This resulted in increased efficiencies being mentioned in the test results.

The experiments indicated that the Stirling engine could improve vehicle operational efficiency by ideally detaching the Stirling from direct power demands, eliminating a direct mechanical linkage as used in most current vehicles. Its prime function used in an extended-range series electric hybrid vehicle would be as a generator providing electricity to drive the electric vehicle traction motors and charging a buffer battery set. In a petro-hydraulic hybrid the Stirling would perform a similar function as in a petro-electric series-hybrid turning a pump charging a hydraulic buffer tank. Although successful in the MOD 1 and MOD 2 phases of the experiments, cutbacks in funding further research and lack of interest by automakers ended possible commercialization of the Automotive Stirling Engine Program.

Electric vehicles

Stirling engines as part of a hybrid electric drive system may be able to bypass the design challenges or disadvantages of a non-hybrid Stirling automobile. In November 2007, a prototypehybrid car

A hybrid vehicle is one that uses two or more distinct types of power, such as submarines that use diesel when surfaced and batteries when submerged. Other means to store energy include pressurized fluid in hydraulic hybrids.

The basic princi ...

using solid biofuel

Biofuel is a fuel that is produced over a short time span from biomass, rather than by the very slow natural processes involved in the formation of fossil fuels, such as oil. According to the United States Energy Information Administration (EIA ...

and a Stirling engine was announced by the Precer project in Sweden.

The ''New Hampshire Union Leader

The ''New Hampshire Union Leader'' is a daily newspaper from Manchester, the largest city in the U.S. state of New Hampshire. On Sundays, it publishes as the ''New Hampshire Sunday News.''

Founded in 1863, the paper was best known for the conse ...

'' reported that Dean Kamen

Dean Lawrence Kamen (born April 5, 1951) is an American engineer, inventor, and businessman. He is known for his invention of the Segway and iBOT, as well as founding the non-profit organization FIRST with Woodie Flowers. Kamen holds over 1,000 ...

developed a series plug-in hybrid

A plug-in hybrid electric vehicle (PHEV) is a hybrid electric vehicle whose battery pack can be recharged by plugging a charging cable into an external electric power source, in addition to internally by its on-board internal combustion engin ...

car using a Ford Think

Think Global was an electric car company located in Bærum, Norway, which manufactured cars under the ''TH!NK'' brand. Production of the Think City was stopped in March 2011 and the company filed for bankruptcy on June 22, 2011, for the fourth t ...

. Called the DEKA Revolt, the car can reach approximately on a single charge of its lithium battery

Lithium battery may refer to:

* Lithium metal battery, a non-rechargeable battery with lithium as an anode

** Rechargeable lithium metal battery, a rechargeable counterpart to the lithium metal battery

* Lithium-ion battery, a rechargeable batt ...

.

Aircraft engines

Robert McConaghy created the first flying Stirling engine-powered aircraft in August 1986. The Beta type engine weighed 360 grams, and produced only 20 Watts of power. The engine was attached to the front of a modified Super Malibu radio control glider with a gross takeoff weight of 1 kg. The best-published test flight lasted 6 minutes and exhibited "barely enough power to make the occasional gentle turn and maintain altitude".Marine engines

The Stirling engine could be well suited for underwater power systems where electrical work or mechanical power is required on an intermittent or continuous level.General Motors

The General Motors Company (GM) is an American multinational automotive manufacturing company headquartered in Detroit, Michigan, United States. It is the largest automaker in the United States and was the largest in the world for 77 years bef ...

has undertaken work on advanced Stirling cycle engines which include thermal storage for underwater applications. United Stirling, in Malmö, Sweden, are developing an experimental four–cylinder engine using hydrogen peroxide as an oxidant in underwater power systems. The SAGA (Submarine Assistance Great Autonomy) submarine became operational in the 1990s and is driven by two Stirling engines supplied with diesel fuel

Diesel fuel , also called diesel oil, is any liquid fuel specifically designed for use in a diesel engine, a type of internal combustion engine in which fuel ignition takes place without a spark as a result of compression of the inlet air and t ...

and liquid oxygen

Liquid oxygen—abbreviated LOx, LOX or Lox in the aerospace, submarine and gas industries—is the liquid form of molecular oxygen. It was used as the oxidizer in the first liquid-fueled rocket invented in 1926 by Robert H. Goddard, an applic ...

. This system also has potential for surface-ship propulsion, as the engine's size is less of a concern, and placing the radiator section in seawater rather than open-air (as a land-based engine would be) allows for it to be smaller.

Swedish shipbuilder Kockums

Saab Kockums AB is a shipyard headquartered in Malmö, Sweden, owned by the Swedish defence company Saab Group. Saab Kockums AB is further operational in Muskö, Docksta, and Karlskrona. While having a history of civil vessel construction, Koc ...

has built 8 successful Stirling powered submarines since the late 1980s.Kockums (a) They carry compressed oxygen to allow fuel combustion submerged, providing heat for the Stirling engine. They are currently used on submarines of the ''Gotland'' and ''Södermanland'' classes. They are the first submarines in the world to feature Stirling air-independent propulsion

Air-independent propulsion (AIP), or air-independent power, is any marine propulsion technology that allows a non-nuclear submarine to operate without access to atmospheric oxygen (by surfacing or using a snorkel). AIP can augment or replace t ...

(AIP), which extends their underwater endurance from a few days to several weeks.

This capability has previously only been available with nuclear-powered submarine

A nuclear submarine is a submarine powered by a nuclear reactor, but not necessarily nuclear-armed. Nuclear submarines have considerable performance advantages over "conventional" (typically diesel-electric) submarines. Nuclear propulsion, ...

s.

The Kockums engine also powers the Japanese ''Sōryū''-class submarine.

Pump engines

Stirling engines can power pumps to move fluids like water, air and gasses. For instance the ST-5 from Stirling Technology Inc. power output of that can run a 3 kW generator or a centrifugal water pump.Electrical power generation

Combined heat and power

In acombined heat and power

Cogeneration or combined heat and power (CHP) is the use of a heat engine or power station to generate electricity and useful heat at the same time.

Cogeneration is a more efficient use of fuel or heat, because otherwise- wasted heat from elect ...

(CHP) system, mechanical or electrical power is generated in the usual way, however, the waste heat given off by the engine is used to supply a secondary heating application. This can be virtually anything that uses low-temperature heat. It is often a pre-existing energy use, such as commercial space heating, residential water heating, or an industrial process.

Thermal power station

A thermal power station is a type of power station in which heat energy is converted to electrical energy. In a steam-generating cycle heat is used to boil water in a large pressure vessel to produce high-pressure steam, which drives a steam ...

s on the electric grid

An electrical grid is an interconnected network for electricity delivery from producers to consumers. Electrical grids vary in size and can cover whole countries or continents. It consists of:Kaplan, S. M. (2009). Smart Grid. Electrical Power ...

use fuel to produce electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described ...

. However, there are large quantities of waste heat produced which often go unused. In other situations, high-grade fuel is burned at high temperatures for a low-temperature application. According to the second law of thermodynamics

The second law of thermodynamics is a physical law based on universal experience concerning heat and energy interconversions. One simple statement of the law is that heat always moves from hotter objects to colder objects (or "downhill"), unless ...

, a heat engine can generate power from this temperature difference. In a CHP system, the high-temperature primary heat enters the Stirling engine heater, then some of the energy is converted to mechanical power in the engine, and the rest passes through to the cooler, where it exits at a low temperature. The "waste" heat actually comes from the engine's main ''cooler'', and possibly from other sources such as the exhaust of the burner, if there is one.

The power produced by the engine can be used to run an industrial or agricultural process, which in turn creates biomass waste refuse that can be used as free fuel for the engine, thus reducing waste removal costs. The overall process can be efficient and cost-effective.

Inspirit Energy, a UK-based company have a gas fired CHP unit called the Inspirit Charger which is on sale in 2016. The floor standing unit generates 3 kW of electrical and 15 kW of thermal energy.

WhisperGen, a New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island country ...

firm with offices in Christchurch

Christchurch ( ; mi, Ōtautahi) is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Canterbury Region. Christchurch lies on the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula on Pegasus Bay. The Avon River ...

, has developed an "AC Micro Combined Heat and Power" Stirling cycle engine. These microCHP

Micro combined heat and power, micro-CHP, µCHP or mCHP is an extension of the idea of cogeneration to the single/multi family home or small office building in the range of up to 50 kW. Usual technologies for the production of heat and power in ...

units are gas-fired central heating boilers that sell unused power back into the electricity grid

An electrical grid is an interconnected network for electricity delivery from producers to consumers. Electrical grids vary in size and can cover whole countries or continents. It consists of:Kaplan, S. M. (2009). Smart Grid. Electrical Power ...

. WhisperGen announced in 2004 that they were producing 80,000 units for the residential market in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and Nor ...

. A 20 unit trial in Germany was conducted in 2006.

Solar power generation

Placed at the focus of a parabolic mirror, a Stirling engine can convert

Placed at the focus of a parabolic mirror, a Stirling engine can convert solar energy

Solar energy is radiant light and heat from the Sun that is harnessed using a range of technologies such as solar power to generate electricity, solar thermal energy (including solar water heating), and solar architecture. It is an essenti ...

to electricity with an efficiency better than non-concentrated photovoltaic cells

A solar cell, or photovoltaic cell, is an electronic device that converts the energy of light directly into electricity by the photovoltaic effect, which is a physical and chemical phenomenon.

, and comparable to concentrated photovoltaics

Concentrator photovoltaics (CPV) (also known as concentration photovoltaics) is a photovoltaic technology that generates electricity from sunlight. Unlike conventional photovoltaic systems, it uses lenses or curved mirrors to focus sunlight onto ...

. On August 11, 2005, Southern California Edison

Southern California Edison (or SCE Corp), the largest subsidiary of Edison International, is the primary electricity supply company for much of Southern California. It provides 15 million people with electricity across a service territory of app ...

announced an agreement with Stirling Energy Systems (SES) to purchase electricity created using over 30,000 Solar Powered Stirling Engines over a twenty-year period sufficient to generate 850 MW of electricity. These systems, on an 8,000 acre (19 km2) solar farm will use mirrors to direct and concentrate sunlight onto the engines which will in turn drive generators. "In January, 2010, four months after breaking ground, Stirling Energy partner company Tessara Solar completed the 1.5 MW Maricopa Solar power plant in Peoria, Arizona

Peoria is a city in Maricopa County, Arizona, Maricopa and Yavapai County, Arizona, Yavapai counties in the U.S. state, state of Arizona. Most of the city is located in Maricopa County, while a portion in the north is in Yavapai County. It is ...

, just outside Phoenix. The power plant is composed of 60 SES SunCatchers." The SunCatcher is described as "a large, tracking, concentrating solar power (CSP) dish collector that generates 25 kilowatts (kW) of electricity in full sun. Each of the 38-foot-diameter collectors contains over 300 curved mirrors (heliostat

A heliostat (from ''helios'', the Greek word for ''sun'', and ''stat'', as in stationary) is a device that includes a mirror, usually a plane mirror, which turns so as to keep reflecting sunlight toward a predetermined target, compensating f ...

s) that focus sunlight onto a power conversion unit, which contains the Stirling engine. The dish uses dual-axis tracking to follow the sun precisely as it moves across the sky." There have been disputes over the project due to concerns of environmental impact on animals living on the site. The Maricopa Solar Plant has been closed.

Nuclear power

There is a potential for nuclear-powered Stirling engines in electric power generation plants. Replacing the steam turbines of nuclear power plants with Stirling engines might simplify the plant, yield greater efficiency, and reduce the radioactive byproducts. A number ofbreeder reactor

A breeder reactor is a nuclear reactor that generates more fissile material than it consumes. Breeder reactors achieve this because their neutron economy is high enough to create more fissile fuel than they use, by irradiation of a fertile mater ...

designs use liquid sodium as a coolant. If the heat is to be employed in a steam plant, a water/sodium heat exchanger is required, which raises some concern if a leak were to occur, as sodium reacts violently with water. A Stirling engine eliminates the need for water anywhere in the cycle. This would have advantages for nuclear installations in dry regions.

United States government labs have developed a modern Stirling engine design known as the Stirling Radioisotope Generator Radioisotope power systems (RPS) are an enabling technology for challenging solar system exploration missions by NASA to destinations where solar energy is weak or intermittent, or where environmental conditions such as dust can limit the ability o ...

for use in space exploration. It is designed to generate electricity for deep space probes on missions lasting decades. The engine uses a single displacer to reduce moving parts and uses high energy acoustics to transfer energy. The heat source is a dry solid nuclear fuel slug, and the heat sink is radiation into free space itself.

Heating and cooling

If supplied with mechanical power, a Stirling engine can function in reverse as aheat pump

A heat pump is a device that can heat a building (or part of a building) by transferring thermal energy from the outside using a refrigeration cycle. Many heat pumps can also operate in the opposite direction, cooling the building by removing h ...

for heating or cooling. In the late 1930s, the Philips Corporation of the Netherlands successfully utilized the Stirling cycle in cryogenic applications. During the Space Shuttle program

The Space Shuttle program was the fourth human spaceflight program carried out by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which accomplished routine transportation for Earth-to-orbit crew and cargo from 1981 to 2011. Its ...

, NASA successfully lofted a Stirling cycle cooler in a form "similar in size and shape to the small domestic

units often used in college dormitories" for use in the Life Science Laboratory. Further research on this unit for domestic use led to a Carnot coefficient-of-performance gain by a factor of three and a weight reduction of 1kg for the unit. Experiments have been performed using wind power driving a Stirling cycle

The Stirling cycle is a thermodynamic cycle that describes the general class of Stirling devices. This includes the original Stirling engine that was invented, developed and patented in 1816 by Robert Stirling with help from his brother, an en ...

heat pump for domestic heating and air conditioning.

Stirling cryocoolers

Any Stirling engine will also work ''in reverse'' as aheat pump

A heat pump is a device that can heat a building (or part of a building) by transferring thermal energy from the outside using a refrigeration cycle. Many heat pumps can also operate in the opposite direction, cooling the building by removing h ...

: when mechanical energy is applied to the shaft, a temperature difference appears between the reservoirs. The essential mechanical components of a Stirling cryocooler are identical to a Stirling engine. In both the engine and the heat pump, heat flows from the expansion space to the compression space; however, input work is required in order for heat to flow "uphill" against a thermal gradient, specifically when the compression space is hotter than the expansion space. The external side of the expansion-space heat exchanger may be placed inside a thermally insulated compartment such as a vacuum flask. Heat is in effect pumped out of this compartment, through the working gas of the cryocooler and into the compression space. The compression space will be above ambient temperature, and so heat will flow out into the environment.

One of their modern uses is in cryogenics

In physics, cryogenics is the production and behaviour of materials at very low temperatures.

The 13th IIR International Congress of Refrigeration (held in Washington DC in 1971) endorsed a universal definition of “cryogenics” and “cr ...

and, to a lesser extent, refrigeration

The term refrigeration refers to the process of removing heat from an enclosed space or substance for the purpose of lowering the temperature.International Dictionary of Refrigeration, http://dictionary.iifiir.org/search.phpASHRAE Terminology, ht ...

. At typical refrigeration temperatures, Stirling coolers are generally not economically competitive with the less expensive mainstream Rankine cooling systems, because they are less energy-efficient. However, below about −40...−30 °C, Rankine cooling is not effective because there are no suitable refrigerants with boiling points this low. Stirling cryocoolers are able to "lift" heat down to −200 °C (73 K), which is sufficient to liquefy air

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing for ...

(specifically the primary constituent gases oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as well ...

, nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at sevent ...

and argon

Argon is a chemical element with the symbol Ar and atomic number 18. It is in group 18 of the periodic table and is a noble gas. Argon is the third-most abundant gas in Earth's atmosphere, at 0.934% (9340 ppmv). It is more than twice as abu ...

). They can go as low as 40–60 K for single-stage machines, depending on the particular design. Two-stage Stirling cryocoolers can reach temperatures of 20 K, sufficient to liquify hydrogen and neon. Cryocoolers for this purpose are more or less competitive with other cryocooler technologies. The coefficient of performance

The coefficient of performance or COP (sometimes CP or CoP) of a heat pump, refrigerator or air conditioning system is a ratio of useful heating or cooling provided to work (energy) required. Higher COPs equate to higher efficiency, lower energy ( ...

at cryogenic temperatures is typically 0.04–0.05 (corresponding to a 4–5% efficiency). Empirically, the devices show a linear trend, typically with the , where ''T''c is the cryogenic temperature. At these temperatures, solid materials have lower specific heat values, so the regenerator must be made from unexpected materials, such as cotton.

The first Stirling-cycle cryocooler was developed at Philips

Koninklijke Philips N.V. (), commonly shortened to Philips, is a Dutch multinational conglomerate corporation that was founded in Eindhoven in 1891. Since 1997, it has been mostly headquartered in Amsterdam, though the Benelux headquarters i ...

in the 1950s and commercialized in such places as liquid air

Liquid air is air that has been cooled to very low temperatures ( cryogenic temperatures), so that it has condensed into a pale blue mobile liquid. To thermally insulate it from room temperature, it is stored in specialized containers ( vacuum in ...

production plants. The Philips Cryogenics business evolved until it was split off in 1990 to form the Stirling Cryogenics BV, The Netherlands. This company is still active in the development and manufacturing of Stirling cryocoolers and cryogenic cooling systems.

A wide variety of smaller Stirling cryocoolers are commercially available for tasks such as the cooling of electronic sensors

A sensor is a device that produces an output signal for the purpose of sensing a physical phenomenon.

In the broadest definition, a sensor is a device, module, machine, or subsystem that detects events or changes in its environment and sends ...

and sometimes microprocessors

A microprocessor is a computer processor where the data processing logic and control is included on a single integrated circuit, or a small number of integrated circuits. The microprocessor contains the arithmetic, logic, and control circu ...

. For this application, Stirling cryocoolers are the highest-performance technology available, due to their ability to lift heat efficiently at very low temperatures. They are silent, vibration-free, can be scaled down to small sizes, and have very high reliability and low maintenance. As of 2009, cryocoolers were considered to be the only widely deployed commercially successful Stirling devices.

Heat pumps

A Stirlingheat pump

A heat pump is a device that can heat a building (or part of a building) by transferring thermal energy from the outside using a refrigeration cycle. Many heat pumps can also operate in the opposite direction, cooling the building by removing h ...

is very similar to a Stirling cryocooler, the main difference being that it usually operates at room temperature. At present, its principal application is to pump heat from the outside of a building to the inside, thus heating it at lowered energy costs.

As with any other Stirling device, heat flow is from the expansion space to the compression space. However, in contrast to the Stirling ''engine'', the expansion space is at a ''lower'' temperature than the compression space, so instead of producing work, an ''input'' of mechanical work is required by the system (in order to satisfy the Second Law of Thermodynamics

The second law of thermodynamics is a physical law based on universal experience concerning heat and energy interconversions. One simple statement of the law is that heat always moves from hotter objects to colder objects (or "downhill"), unless ...

). The mechanical energy input can be supplied by an electrical motor, or an internal combustion engine, for example. When the mechanical work for the heat pump is provided by a second Stirling engine, then the overall system is called a "heat-driven heatpump".

The expansion side of the heat pump is thermally coupled to the heat source, which is often the external environment. The compression side of the Stirling device is placed in the environment to be heated, for example, a building, and heat is "pumped" into it. Typically there will be thermal insulation

Thermal insulation is the reduction of heat transfer (i.e., the transfer of thermal energy between objects of differing temperature) between objects in thermal contact or in range of radiative influence. Thermal insulation can be achieved with s ...

between the two sides so there will be a temperature rise inside the insulated space.

Heat pumps are by far the most energy-efficient types of heating systems, since they "harvest" heat from the environment, rather than only turning their input energy into heat. In accordance with the Second Law of Thermodynamics, heat pumps always require the ''additional input'' of some external energy to "pump" the collected heat "uphill" against a temperature differential.

Compared to conventional heat pumps, Stirling heat pumps often have a higher coefficient of performance

The coefficient of performance or COP (sometimes CP or CoP) of a heat pump, refrigerator or air conditioning system is a ratio of useful heating or cooling provided to work (energy) required. Higher COPs equate to higher efficiency, lower energy ( ...

. Stirling systems have seen limited commercial use; however, use is expected to increase along with market demand for energy conservation, and adoption will likely be accelerated by technological refinements.

Portable refrigeration

The Free Piston Stirling Cooler (FPSC) is a completely sealed heat transfer system that has only two moving parts (a piston and a displacer), and which can usehelium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. It ...

as the working fluid

For fluid power, a working fluid is a gas or liquid that primarily transfers force, motion, or mechanical energy. In hydraulics, water or hydraulic fluid transfers force between hydraulic components such as hydraulic pumps, hydraulic cylinders, a ...

. The piston is typically driven by an oscillating magnetic field that is the source of the power needed to drive the refrigeration cycle. The magnetic drive allows the piston to be driven without requiring any seals, gaskets, O-ring

An O-ring, also known as a packing or a toric joint, is a mechanical gasket in the shape of a torus; it is a loop of elastomer with a round cross-section, designed to be seated in a groove and compressed during assembly between two or more pa ...

s, or other compromises to the hermetically sealed system. Claimed advantages for the system include improved efficiency and cooling capacity, lighter weight, smaller size and better controllability.

The FPSC was invented in 1964 by William Beale (1928-2016), a professor of Mechanical Engineering at Ohio University

Ohio University is a public research university in Athens, Ohio. The first university chartered by an Act of Congress and the first to be chartered in Ohio, the university was chartered in 1787 by the Congress of the Confederation and subseque ...

in Athens, Ohio

Athens is a city and the county seat of Athens County, Ohio. The population was 23,849 at the 2020 census. Located along the Hocking River within Appalachian Ohio about southeast of Columbus, Athens is best known as the home of Ohio Universit ...

. He founded Sunpower Inc., which researches and develops FPSC systems for military, aerospace, industrial, and commercial applications. A FPSC cooler made by Sunpower was used by NASA to cool instrumentation in satellites

A satellite or artificial satellite is an object intentionally placed into orbit in outer space. Except for passive satellites, most satellites have an electricity generation system for equipment on board, such as solar panels or radioisotop ...

. The firm was sold by the Beale family in 2015 to become a unit of Ametek

AMETEK, Inc. is an American multinational conglomerate and global designer and manufacturer of electronic instruments and electromechanical devices with headquarters in the United States and over 220 sites worldwide.

The company was founded in 1 ...

.

Other suppliers of FPSC technology include the Twinbird Corporation of Japan and Global Cooling

Global cooling was a conjecture, especially during the 1970s, of imminent cooling of the Earth culminating in a period of extensive glaciation, due to the cooling effects of aerosols or orbital forcing.

Some press reports in the 1970s specula ...

of the Netherlands, which (like Sunpower) has a research center in Athens, Ohio.

For several years starting around 2004, the Coleman Company

The Coleman Company, Inc. is an American brand of outdoor recreation products, especially camping gear, now owned by Newell Brands. The company's new headquarters are in Chicago, and it has facilities in Wichita, Kansas, and in Texas. There are ...

sold a version of the Twinbird "SC-C925 Portable Freezer Cooler 25L" under its own brand name, but it has since discontinued offering the product. The portable cooler can be operated more than a day, maintaining sub-freezing temperatures while powered by an automotive battery

An automotive battery or car battery is a rechargeable battery that is used to start a motor vehicle. Its main purpose is to provide an electric current to the electric-powered starting motor, which in turn starts the chemically-powered interna ...

. This cooler is still being manufactured, with Global Cooling now coordinating distribution to North America and Europe. Other variants offered by Twinbird include a portable deep freezer (to −80 °C), collapsible coolers, and a model for transporting blood and vaccine

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious or malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verified.

.

Low temperature difference engines

A low temperature difference (LTD, or Low Delta T (LDT)) Stirling engine will run on any low-temperature differential, for example, the difference between the palm of a hand and room temperature, or room temperature and an ice cube. A record of only 0.5 °C temperature differential was achieved in 1990. Usually they are designed in a gamma configuration for simplicity, and without a regenerator, although some have slits in the displacer typically made of foam for partial regeneration. They are typically unpressurized, running at pressure close to 1

A low temperature difference (LTD, or Low Delta T (LDT)) Stirling engine will run on any low-temperature differential, for example, the difference between the palm of a hand and room temperature, or room temperature and an ice cube. A record of only 0.5 °C temperature differential was achieved in 1990. Usually they are designed in a gamma configuration for simplicity, and without a regenerator, although some have slits in the displacer typically made of foam for partial regeneration. They are typically unpressurized, running at pressure close to 1 atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A s ...

. The power produced is less than 1 W, and they are intended for demonstration purposes only. They are sold as toys and educational models.

However, larger (typically 1 m square) low temperature engines have been built for pumping water using direct sunlight with minimal or no magnification.

Other applications

Acoustic Stirling Heat Engine

Los Alamos National Laboratory has developed an "Acoustic Stirling Heat Engine" with no moving parts. It converts heat into intense acoustic power which (quoted from given source) "can be used directly in acoustic refrigerators or pulse-tube refrigerators to provide heat-driven refrigeration with no moving parts, or ... to generate electricity via a linear alternator or other electro-acoustic power transducer".MicroCHP

WhisperGen, (bankruptcy 2012) a New Zealand-based company has developed Stirling engines that can be powered by natural gas or diesel. An agreement has been signed with Mondragon Corporación Cooperativa, a Spanish firm, to produce WhisperGen's microCHP (Combined Heat and Power) and make them available for the domestic market in Europe. Some time agoE.ON UK

E.ON UK is a British energy company and the largest supplier of energy and renewable electricity in the UK, following its acquisition of Npower. It is a subsidiary of E.ON of Germany and one of the Big Six energy suppliers. It was founded in 1 ...

announced a similar initiative for the UK. Domestic Stirling engines would supply the client with hot water, space heating, and a surplus electric power that could be fed back into the electric grid.

Based on the companies' published performance specifications, the off-grid diesel-fueled unit produces combined heat (5.5 kW heat) and electric (800W electric) output, from a unit being fed 0.75 liters of automotive-grade diesel fuel per hour. Whispergen units are claimed to operate as a combined co-generation unit reaching as high as ~80% operating efficiency.

However the preliminary results of an Energy Saving Trust review of the performance of the WhisperGen microCHP units suggested that their advantages were marginal at best in most homes. However another author shows that Stirling engine microgeneration is the most cost effective of various microgeneration technologies in terms of reducing CO2.

Chip cooling

MSI (Taiwan) developed a miniature Stirling engine cooling system for personal computer chips that uses the waste heat from the chip to drive a fan.Desalination

In all thermal power plants there has to be an exhaust ofwaste heat

Waste heat is heat that is produced by a machine, or other process that uses energy, as a byproduct of doing work. All such processes give off some waste heat as a fundamental result of the laws of thermodynamics. Waste heat has lower utility ( ...

. However, there's no reason that the waste heat cannot be diverted to run Stirling engines to pump seawater through reverse osmosis

Reverse osmosis (RO) is a water purification process that uses a partially permeable membrane to separate ions, unwanted molecules and larger particles from drinking water. In reverse osmosis, an applied pressure is used to overcome osmotic pr ...

assemblies except that any additional use of the heat raises the effective heat sink temperature for the thermal power plant resulting in some loss of energy conversion efficiency

Energy conversion efficiency (''η'') is the ratio between the useful output of an energy conversion machine and the input, in energy terms. The input, as well as the useful output may be chemical, electric power, mechanical work, light (radi ...

. In a typical nuclear power plant, two-thirds of the thermal energy produced by the reactor is waste heat. In a Stirling assembly the waste heat has the potential to be used as an additional source of electricity.

References

{{reflist, colwidth=30em Cooling technology Heat pumps Stirling engines Piston engines External combustion engines