Anti-Parliamentary Communist Federation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Anti-Parliamentary Communist Federation (APCF) was a

When Labour formed its first government with

When Labour formed its first government with  Having previously opposed the

Having previously opposed the

The fallout from the

The fallout from the  The remaining members of the APCF disagreed with Aldred's conclusions and maintained the organisation as it was, causing a split within the movement that divided anti-parliamentarists throughout the 1930s. In spite of the APCF's continuation, Aldred claimed that it had, in fact, dissolved following his departure and considered his new organisation - the

The remaining members of the APCF disagreed with Aldred's conclusions and maintained the organisation as it was, causing a split within the movement that divided anti-parliamentarists throughout the 1930s. In spite of the APCF's continuation, Aldred claimed that it had, in fact, dissolved following his departure and considered his new organisation - the

Months after leaders of the CNT joined the Republican government under

Months after leaders of the CNT joined the Republican government under  Despite the APCF's call for unity, its relations with the USM remained hostile, with the two groups competing for recognition as the official representative of the CNT-FAI in Britain, the APCF eventually winning the bid with the support of

Despite the APCF's call for unity, its relations with the USM remained hostile, with the two groups competing for recognition as the official representative of the CNT-FAI in Britain, the APCF eventually winning the bid with the support of

The role of political parties in the labour movement was of particular interest to the APCF, which published in its journal ''Solidarity'' a debate between the

The role of political parties in the labour movement was of particular interest to the APCF, which published in its journal ''Solidarity'' a debate between the

Although the APCF had initially supported the

Although the APCF had initially supported the

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

group in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

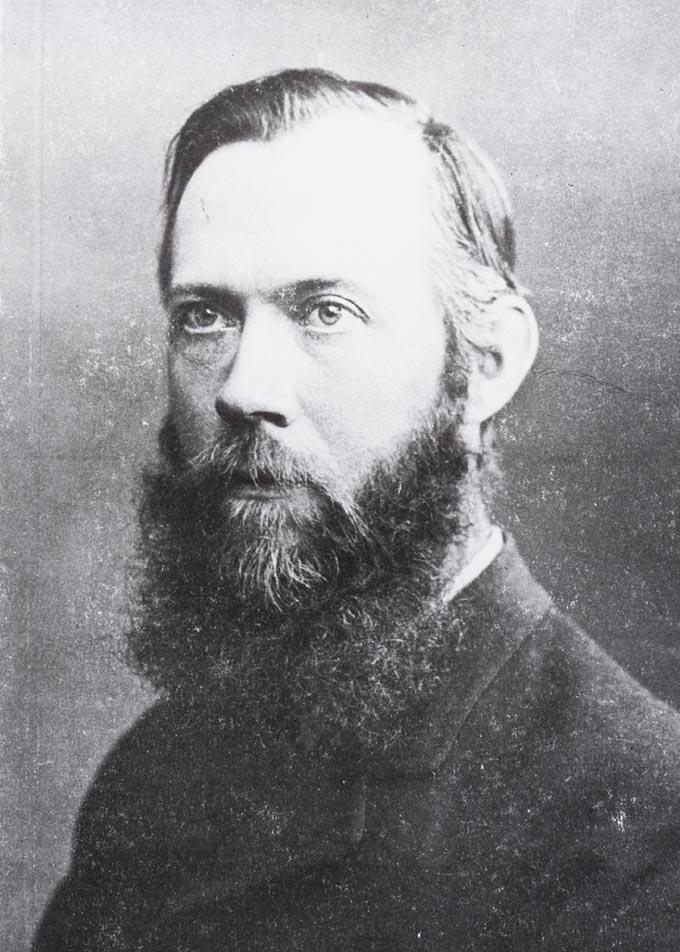

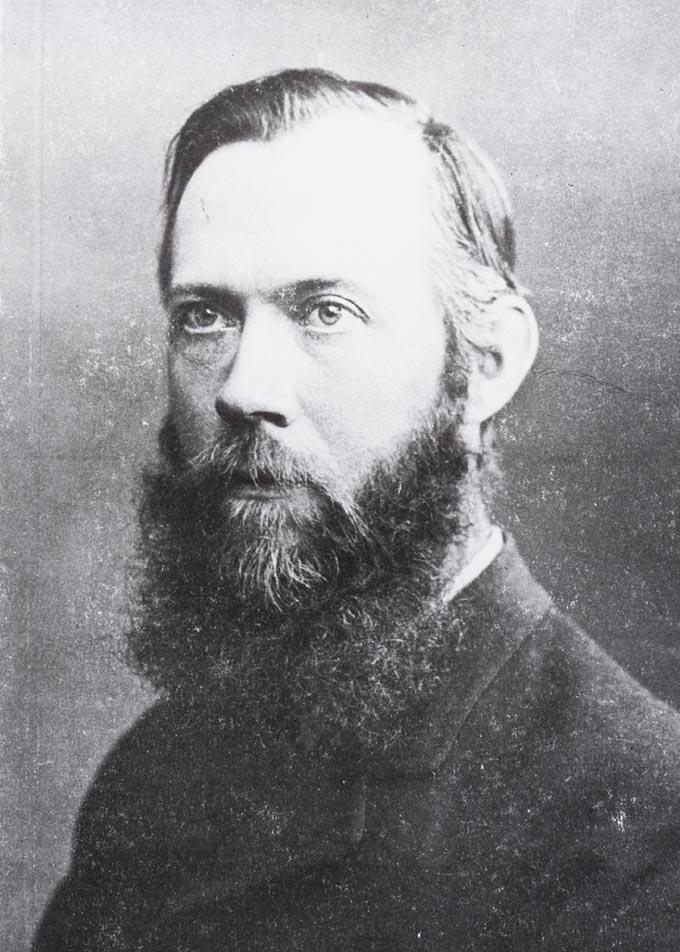

. It was founded by the group around Guy Aldred

Guy Alfred Aldred (often Guy A. Aldred; 5 November 1886 – 16 October 1963) was a British anarcho-communist and a prominent member of the Anti-Parliamentary Communist Federation (APCF). He founded the Bakunin Press publishing house and edited ...

's ''Spur

A spur is a metal tool designed to be worn in pairs on the heels of riding boots for the purpose of directing a horse or other animal to move forward or laterally while riding. It is usually used to refine the riding aids (commands) and to ba ...

'' newspaper – mostly former Communist League

The Communist League (German: ''Bund der Kommunisten)'' was an international political party established on 1 June 1847 in London, England. The organisation was formed through the merger of the League of the Just, headed by Karl Schapper, and t ...

members – in 1921. They included John McGovern.

History

WhenSylvia Pankhurst

Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst (5 May 1882 – 27 September 1960) was a campaigning English feminist and socialist. Committed to organising working-class women in London's East End, and unwilling in 1914 to enter into a wartime political truce with t ...

's Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engel ...

dissolved itself into the newly founded Communist Party of Great Britain

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was the largest communist organisation in Britain and was founded in 1920 through a merger of several smaller Marxist groups. Many miners joined the CPGB in the 1926 general strike. In 1930, the CPGB ...

(CPGB) in January 1921, many libertarian communists refused to join due to the CPGB's policy of parliamentarism

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of t ...

. Guy Aldred

Guy Alfred Aldred (often Guy A. Aldred; 5 November 1886 – 16 October 1963) was a British anarcho-communist and a prominent member of the Anti-Parliamentary Communist Federation (APCF). He founded the Bakunin Press publishing house and edited ...

's Glasgow Communist Group immediately responded by publishing the ''Red Commune'' paper, in which they advocated for anti-parliamentarism in the form of election boycott

An election boycott is the boycotting of an election by a group of voters, each of whom abstains from voting.

Boycotting may be used as a form of political protest where voters feel that electoral fraud is likely, or that the electoral system ...

s and abstentionism

Abstentionism is standing for election to a deliberative assembly while refusing to take up any seats won or otherwise participate in the assembly's business. Abstentionism differs from an election boycott in that abstentionists participate in ...

, inviting fellow libertarian communists to a conference at which the Anti-Parliamentary Communist Federation was established. Rose Witcop was sent as a delegate to the Third Congress of the Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

, where she received an offer of financial backing on the condition that the APCF joined the CPGB and abandoned any anti-parliamentarism, which the Federation refused and cut ties with the International.

During the 1922 United Kingdom general election

The 1922 United Kingdom general election was held on Wednesday 15 November 1922. It was won by the Conservative Party, led by Bonar Law, which gained an overall majority over the Labour Party, led by J. R. Clynes, and a divided Liberal Party. ...

, Aldred stood in Glasgow Shettleston on a platform of abstentionism, in a move that was opposed by anarchists within the APCF, with the Federation refusing to lend official support to the campaign. Aldred came last in the election, with only 470 votes. The APCF subsequently distributed propaganda calling for workers to participate in an election boycott during both the 1923 and 1924 general elections.

After the Communist Workers' Party (CWP) dissolved in June 1924, the APCF became Britain's sole anti-parliamentary communist organisation. This led the British anti-parliamentary movement to move away from the internationalism that had influenced the CWP and focus more on local issues, particularly events happening in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, the headquarters of the APCF. It even rejected the idea of building a new political international

A political international is a transnational organization of political parties having similar ideology or political orientation (e.g. communism, socialism, and Islamism). The international works together on points of agreement to co-ordinate activ ...

, with the Communist Workers' International later complaining that the APCF had made no attempt to contact them.

Opposition to the Labour Party

After theFourth World Congress

Fourth or the fourth may refer to:

* the ordinal form of the number 4

* ''Fourth'' (album), by Soft Machine, 1971

* Fourth (angle), an ancient astronomical subdivision

* Fourth (music), a musical interval

* ''The Fourth'' (1972 film), a Sovie ...

of the Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

decided to advance the tactic of a united front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts and/or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political ...

between the Communists and the Labour Party, the APCF further rejected the International's policy, arguing that the Labour Party was an "anti-working class movement, the last earthwork of reaction."

When Labour formed its first government with

When Labour formed its first government with Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

support, the APCF's changed the masthead of its newspaper the ''Commune'' to "An Organ Of His Majesty's Communist Opposition", indicating their opposition to the Labour government and publishing lengthy criticisms of the new government ministers. Labour's "parliamentarian" policies were further criticised by the APCF as what amounted to a "continuation of capitalism", which the Federation contrasted with several of its own "anti-parliamentarian" policies that were to be implemented for the "overthrow of capitalism". Following the electoral defeat of the Labour government and Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

's resignation as Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

, the APCF published in the ''Commune'' a report of the government's time in office, in which it claimed that the MacDonald ministry had "functioned no differently from any other Capitalist Government".

In their October 1926 issue of ''Commune'', the APCF reviewed the record of MacDonald's first Labour government, highlighting its use of the military to suppress strike action

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to Labor (economics), work. A strike usually takes place in response to grievance (labour), employee grievance ...

s and concluding that it had "functioned no differently from any other Capitalist Government". The APCF also criticised the Labour government's nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

policies as a form of state capitalism

State capitalism is an economic system in which the state undertakes business and commercial (i.e. for-profit) economic activity and where the means of production are nationalized as state-owned enterprises (including the processes of capital a ...

, instead advocating for social ownership

Social ownership is the appropriation of the surplus product, produced by the means of production, or the wealth that comes from it, to society as a whole. It is the defining characteristic of a socialist economic system. It can take the form o ...

as an alternative to state ownership

State ownership, also called government ownership and public ownership, is the ownership of an industry, asset, or enterprise by the state or a public body representing a community, as opposed to an individual or private party. Public ownershi ...

, claiming that workers had "nothing to gain" from nationalised industries. The APCF also targeted attacks against individual members of the Labour Party, such as the Secretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom, British Cabinet government minister, minister in charge of managing the United Kingdom's various British Empire, colonial dependencies.

Histor ...

J. H. Thomas

James Henry Thomas (3 October 1874 – 21 January 1949), sometimes known as Jimmy Thomas or Jim Thomas, was a Welsh trade unionist and Labour (later National Labour) politician. He was involved in a political scandal involving budget leaks. ...

, the jingoistic trade union leader Ben Tillett and the Glaswegian anti-parliamentarist turned politician John Clarke. The APCF also disrupted a number of meetings that hosted Arthur Henderson

Arthur Henderson (13 September 1863 – 20 October 1935) was a British iron moulder and Labour politician. He was the first Labour cabinet minister, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1934 and, uniquely, served three separate terms as Leader of th ...

, who they condemned for his participation in David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

's war government, leading to seventeen people being arrested. The APCF declared that "there exists as much Socialism in the constitution and the activity of the Parliamentary Labour Party

In UK politics, the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) is the parliamentary group of the Labour Party in Parliament, i.e. Labour MPs as a collective body. Commentators on the British Constitution sometimes draw a distinction between the Labour P ...

as there is divinity in the priesthood" and criticised the CPGB for its continued attempts to affiliate with the "anti-Socialist" Labour Party, reiterating its opposition to the Comintern's united front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts and/or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political ...

tactic.

Having previously opposed the

Having previously opposed the National Minority Movement

The National Minority Movement was a British organisation, established in 1924 by the Communist Party of Great Britain, which attempted to organise a radical presence within the existing trade unions. The organization was headed by longtime unio ...

's tactic of working within reformist trade unions, by the time the 1926 general strike broke out, they again opposed the CPGB's collaboration with the General Council General council may refer to:

In education:

* General Council (Scottish university), an advisory body to each of the ancient universities of Scotland

* General Council of the University of St Andrews, the corporate body of all graduates and senio ...

of the Trades Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a national trade union centre

A national trade union center (or national center or central) is a federation or confederation of trade unions in a country. Nearly every country in the world has a national tra ...

(TUC), instead advocating for power to be transferred directly to strike committees and mass meeting

In parliamentary law, a mass meeting is a type of deliberative assembly or popular assembly, which in a publicized or selectively distributed notice known as the call of the meeting - has been announced: (RONR)

*as called to take appropriate acti ...

s. After the TUC called off the strike, the APCF condemned the actions of the TUC's leaders, which they believed had proven their own position that reformist trade unions had become another part of the capitalist system.

The waning of the Revolutions of 1917–1923

The Revolutions of 1917–1923 was a revolutionary wave that included political unrest and armed revolts around the world inspired by the success of the Russian Revolution and the disorder created by the aftermath of World War I. The uprisings ...

, rise and fall of the Labour government and the defeat of the general strike had all contributed to a sense of pessimism regarding the prospects of any coming social revolution. Despite entering a period of decline, the anti-parliamentary communist movement was maintained throughout the late 1920s by the APCF, which continued to uphold the communist programme that it had developed since before the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

had ever taken place. But before long, the APCF suffered a split.

Split

The fallout from the

The fallout from the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

led the APCF to proclaim that the end of capitalism was imminent, as the economic collapse had destroyed the material conditions

Historical materialism is the term used to describe Karl Marx's theory of history. Marx locates historical change in the rise of class societies and the way humans labor together to make their livelihoods. For Marx and his lifetime collaborat ...

that incentivised reformism

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can eve ...

and - by extension - parliamentarism. In the APCF's appeal ''To Anti-parliamentarians'', they argued that concessions could only be granted to the working class during a period of upswing, but following the economic crisis it had become impossible to secure reforms, concluding that "grim necessity will compel the workers to social revolution."

In 1929, Aldred correctly predicted the formation of a National Government by a coalition of Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

's Labour Party and Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

's Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

, to which he responded by declaring that "Anti-Parliamentarism has arrived." The free speech fight

Free speech fights are struggles over free speech, and especially those struggles which involved the Industrial Workers of the World and their attempts to gain awareness for labor issues by organizing workers and urging them to use their collective ...

in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

had also provided an impetus for the split within the APCF, as various different organizations had come together to form a Free Speech Committee, in order to engage in a direct action campaign to re-establish freedom of assembly

Freedom of peaceful assembly, sometimes used interchangeably with the freedom of association, is the individual right or ability of people to come together and collectively express, promote, pursue, and defend their collective or shared ide ...

and freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogni ...

in the city. The Committee eventually evolved into a workers' council

A workers' council or labor council is a form of political and economic organization in which a workplace or municipality is governed by a council made up of workers or their elected delegates. The workers within each council decide on what thei ...

to maintain the unity that had been achieved, but it quickly declined until the council was effectively another front of the APCF. Those that had participated in the movement, including Aldred, became convinced of the necessity to unite the various disparate workers' organisations into a single movement capable of defeating capitalism. They saw the workers' councils as a means of achieving an end to sectarianism

Sectarianism is a political or cultural conflict between two groups which are often related to the form of government which they live under. Prejudice, discrimination, or hatred can arise in these conflicts, depending on the political status quo ...

, as they could allow the participation of all factions "without impeaching the integrity of any", concluding on the necessity of abandoning anti-parliamentary agitation in favour of building a workers' council movement. Arguing that, since parliamentarism itself had collapsed with the establishment of the National Government, it was no longer necessary to propagate anti-parliamentarism, Aldred resigned from the APCF in February 1933.

The remaining members of the APCF disagreed with Aldred's conclusions and maintained the organisation as it was, causing a split within the movement that divided anti-parliamentarists throughout the 1930s. In spite of the APCF's continuation, Aldred claimed that it had, in fact, dissolved following his departure and considered his new organisation - the

The remaining members of the APCF disagreed with Aldred's conclusions and maintained the organisation as it was, causing a split within the movement that divided anti-parliamentarists throughout the 1930s. In spite of the APCF's continuation, Aldred claimed that it had, in fact, dissolved following his departure and considered his new organisation - the United Socialist Movement

The United Socialist Movement (USM) was an anarcho-communist political organisation based in Glasgow. Founded in 1934 after splitting from the Anti-Parliamentary Communist Federation, the USM initially aimed to unite revolutionary socialists int ...

(USM) - to be the APCF's direct successor. The APCF had been in a temporary hiatus, but resumed activities in 1935 with the publication of two pamphlets. One was ''The Bourgeois Role of Bolshevism'' by the Dutch Group of International Communists (GIC), which argued that the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

had from the outset been a bourgeois revolution

Bourgeois revolution is a term used in Marxist theory to refer to a social revolution that aims to destroy a feudal system or its vestiges, establish the rule of the bourgeoisie, and create a bourgeois state. In colonised or subjugated countries ...

, aiming to transform the Russian economy from agrarian feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

to industrial

Industrial may refer to:

Industry

* Industrial archaeology, the study of the history of the industry

* Industrial engineering, engineering dealing with the optimization of complex industrial processes or systems

* Industrial city, a city dominate ...

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for Profit (economics), profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, pric ...

, where the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

had used the mass movement of peasants and workers to seize power and overrule both of them. The other was ''Organizational Questions of the Russian Social Democracy

''Organizational Questions of the Russian Social Democracy'', later republished as ''Leninism or Marxism?'', is a 1904 pamphlet by Rosa Luxemburg, a Marxist living in Germany. In the text, she criticized Vladimir Lenin and the Bolshevik faction of ...

'' by Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg (; ; pl, Róża Luksemburg or ; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary socialist, Marxist philosopher and anti-war activist. Successively, she was a member of the Proletariat party, ...

, which they gave the name ''Leninism or Marxism?'' to. The text criticised Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

's view on the role of democratic centralism

Democratic centralism is a practice in which political decisions reached by voting processes are binding upon all members of the political party. It is mainly associated with Leninism, wherein the party's political vanguard of professional revo ...

in a vanguard party

Vanguardism in the context of Leninist revolutionary struggle, relates to a strategy whereby the most class-conscious and politically "advanced" sections of the proletariat or working class, described as the revolutionary vanguard, form organi ...

to lead a revolution, arguing that revolutionary spontaneity

Revolutionary spontaneity, also known as spontaneism, is a revolutionary socialist tendency that believes the social revolution can and should occur spontaneously from below by the working class itself, without the aid or guidance of a vanguar ...

was the driving force of any labour movement and emphasising that any dictatorship of the proletariat

In Marxist philosophy, the dictatorship of the proletariat is a condition in which the proletariat holds state power. The dictatorship of the proletariat is the intermediate stage between a capitalist economy and a communist economy, whereby the ...

should be a mass movement of the whole working class rather than the work of a minority political party.

Despite the split, the APCF attempted to co-operate with other like-minded groups both in Britain and abroad. After Paul Mattick

Paul Mattick Sr. (March 13, 1904 – February 7, 1981) was a German-American Marxist political writer and social revolutionary, whose thought can be placed within the council communist and left communist traditions.

Throughout his life, Mattic ...

's Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

-based United Workers' Party (UWP) rebuffed Aldred's attempts to unite it with the Communist League of Struggle

The Communist League of Struggle (CLS) was a small communist organization active in the United States during the 1930s. Founded by Albert Weisbord and his wife, Vera Buch, who were veterans of the Left Socialist movement and the Communist Party ...

(CLS), the APCF worked actively to maintain its links with the UWP and their magazine the '' International Council Correspondence''. The APCF came together with the USM, as well as the Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

(ILP) and Revolutionary Socialist Party (RSP), to establish the Socialist Anti-Terror Committee in Glasgow, a short-lived organisation formed in order to oppose the ongoing "Great Terror

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

" in the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. Meanwhile, Aldred's " domineering personality" brought a number of people to resign from the USM, with some joining the APCF. Nevertheless, the APCF's influence within British politics remained small. By this time, a wave of pessimism regarding the revolutionary prospects in Britain and around the world permeated through the weak and isolated anti-parliamentary movement, now confined to merely analyzing political events from the sidelines. European council communist

Council communism is a current of communist thought that emerged in the 1920s. Inspired by the November Revolution, council communism was opposed to state socialism and advocated workers' councils and council democracy. Strong in Germany a ...

ideas began to work their way into the APCF's ideology, which started to pick up decadence theory, on display in their May 1936 issue of ''Advance'', in which one members analyzed the Italian invasion of Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

as a product of Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

's capitalistic need to expand in the face of bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debtor ...

. They also made use of decadence theory in their article ''Capitalism Must Go!'', in which they explained overproduction

In economics, overproduction, oversupply, excess of supply or glut refers to excess of supply over demand of products being offered to the market. This leads to lower prices and/or unsold goods along with the possibility of unemployment.

The de ...

, coupled with a rise in unemployment

Unemployment, according to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), is people above a specified age (usually 15) not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for Work (human activity), w ...

and a reduction in demand, to be the key reason for the Great Depression.

The outbreak of the Spanish Revolution was welcomed by the APCF, not only a key challenge to the rise of fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

, but one which had also caused a resurgence in the activities of the previously declining British anti-parliamentary communist movement.

Spanish Civil War

Although the APCF had previously criticised thereformist

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can eve ...

tendencies displayed by the Spanish labour movement with the Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

victory in 1936 Spanish general election, they declared that the reforms brought by the new government were due to the popular movement that had elected the government to power in the first place, describing the Popular Front as a "capitalist administration" and calling for system change rather than mere regime change. But their views on the Popular Front government changed in the wake of the nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

coup. They had initially analyzed the coup through an anti-parliamentary lens, commenting that: "The uselessness of parliament should be obvious to all ..wherever the ruling class decides that parliament fails to express their desires, parliament will be abolished!" But they swiftly took on a notably constitutionalist

Constitutionalism is "a compound of ideas, attitudes, and patterns of behavior elaborating the principle that the authority of government derives from and is limited by a body of fundamental law".

Political organizations are constitutional ...

approach towards the nascent civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

by focusing on the nationalists' breaking of "international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

" and describing the Popular Front as an "orthodox democratic government". These terms were used in an attempt to coax intervention from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

into the war, with the APCF criticising the British government for refusing to provide aid to the Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 A ...

and for placing an arms embargo

An arms embargo is a restriction or a set of sanctions that applies either solely to weaponry or also to "dual-use technology." An arms embargo may serve one or more purposes:

* to signal disapproval of the behavior of a certain actor

* to maintain ...

on the "legally and democratically constituted government of Spain".

Francisco Largo Caballero

Francisco Largo Caballero (15 October 1869 – 23 March 1946) was a Spanish politician and trade unionist. He was one of the historic leaders of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) and of the Workers' General Union (UGT). In 1936 and 19 ...

, the APCF published a pamphlet by the anarchist Minister of Health A health minister is the member of a country's government typically responsible for protecting and promoting public health and providing welfare and other social security services.

Some governments have separate ministers for mental health.

Coun ...

Federica Montseny

Frederica Montseny i Mañé (; 1905–1994) was a Catalan Anarchism, anarchist and intellectual who served as Ministry of Health (Spain), Minister of Health and Social Assistance in the Government of the Second Spanish Republic, Spanish Republi ...

which defended anarchist collaboration with the republicans, under the cause of the "unity of all anti-fascists

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were ...

". The initial unity of various differing factions under the Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

banner was a source of inspiration to the APCF, who urged the formation of a similar united front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts and/or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political ...

in Britain. The Federation even went as far as to suspend its journal, instead collaborating with the ''Freedom

Freedom is understood as either having the ability to act or change without constraint or to possess the power and resources to fulfill one's purposes unhindered. Freedom is often associated with liberty and autonomy in the sense of "giving on ...

'' newspaper on a joint monthly publication ''Fighting Call''.

Despite the APCF's call for unity, its relations with the USM remained hostile, with the two groups competing for recognition as the official representative of the CNT-FAI in Britain, the APCF eventually winning the bid with the support of

Despite the APCF's call for unity, its relations with the USM remained hostile, with the two groups competing for recognition as the official representative of the CNT-FAI in Britain, the APCF eventually winning the bid with the support of Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

. As a result, the APCF's publications ''Fighting Call'' and ''Advance'' became solely dedicated to publishing material from the CNT-FAI, without criticism, comment or editorial. The feud between the APCF and USM continued when their respective delegates were sent to Spain, with the APCF's delegate Jane Patrick being expelled from the Federation before she even arrived, causing a confrontation between the two groups in Glasgow.

By April 1937, relations between the APCF and USM started to improve, following the resignation of the APCF's Frank Leech, who had frequently prevented their co-operation, going on to found the Glasgow Anarchist Federation (GAF). The following month, the two collaborated on the publication of the ''Barcelona Bulletin'', which published their delegates' accounts of the May Days

The May Days, sometimes also called May Events, refer to a series of clashes between 3 and 8 May 1937 during which factions on the Republican faction of the Spanish Civil War engaged one another in street battles in various parts of Catalonia, ...

in Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

, providing a sympathetic view of the revolutionary faction represented by the anarchists of the CNT-FAI and the Trotskyists of the POUM

The Workers' Party of Marxist Unification ( es, Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, POUM; ca, Partit Obrer d'Unificació Marxista) was a Spanish communist party formed during the Second Spanish Republic, Second Republic and mainly active a ...

. While the USM had long-since revised its position of supporting the Republican government, due to reports from its delegate Ethel MacDonald

Camelia Ethel MacDonald (24 February 1909 – 1 December 1960) was a Glasgow-based Scottish anarchist, activist, and 1937, Spanish Civil War broadcaster on pro-Republican, anti-Fascist Barcelona radio.

Early years

Camelia Ethel McDonald wa ...

, it was only after the May Days that the APCF followed suit. The APCF took the position that the policy of the united anti-fascist front was one of collaboration with capitalism, publishing an article by MacDonald which stated that "Anti-Fascism is the new slogan by which the working class is being betrayed." When MacDonald was arrested and imprisoned by the Catalan government

The Generalitat de Catalunya (; oc, label= Aranese, Generalitat de Catalonha; es, Generalidad de Cataluña), or the Government of Catalonia, is the institutional system by which Catalonia politically organizes its self-government. It is formed ...

, the APCF organised a Defence Committee to secure her release, with MacDonald escaping Spain and returning safely to Glasgow by November 1937, leading the Defence Committee to lend its support to other prisoners and refugees of the war.

Despite the revision of their position towards the republican government, the APCF never quite diverted from its original policies, publishing some articles that supported the government and others that supported the revolutionaries, often both in the same issue of ''Solidarity''. In the second issue of the journal, the APCF published a report from Spain which argued that the civil war could have been avoided entirely "if the workers had taken control and eliminated the government", while also publishing a call for a general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

to force an end to Britain's arms embargo on the Republican government. In a subsequent issue released after the nationalist victory in the war, they published an article by the Friends of Durruti Group

The Friends of Durruti Group (in Spanish, ''Agrupación de los Amigos de Durruti'') was an anarchist group in Spain, named after Buenaventura Durruti. It was founded on 15 March 1937, by Jaime Balius, Félix Martínez (anarchist), Félix Martínez ...

which concluded that "Democracy defeated the Spanish people, not Fascism."

World War II

With the conclusion of the Spanish Civil War, it quickly became apparent that a major global conflict was on the horizon. The APCF's analysis of what becameWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

was one of a military conflict between capitalist nations rivalling for supremacy, rejecting the dominant notion of it being a war of democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose gov ...

against fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

. They called for workers to resist the coming war, claiming that in the making of this war British business interests would "destroy capitalist democracy and every vestige of workers' democracy to ensure the continuity of their capitalism (i.e. their profits)."

When the war broke out, the APCF adopted a revolutionary defeatist position, proclaiming: "Down with Nazism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

and Fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

, but also down with all imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

, British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and French included!" Pointing out that "all the Capitalists are aggressors from the workers' point of view", they called for the destruction of all states that were party to the conflict, including the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

. The APCF later elaborated that they stood for the defeat of the Axis Powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

not by the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

, but by the workers of those countries, while also standing simultaneously for the defeat of the Allies by the workers of their own countries, essentially calling for a world revolution

World revolution is the Marxist concept of overthrowing capitalism in all countries through the conscious revolutionary action of the organized working class. For theorists, these revolutions will not necessarily occur simultaneously, but whe ...

to end the war. Given that since the outbreak of the war the trade unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and Employee ben ...

had been opposing strike action

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to Labor (economics), work. A strike usually takes place in response to grievance (labour), employee grievance ...

, the APCF believed that the creation of new unofficial forms of organisation were necessary, proposing the formation of workers' council

A workers' council or labor council is a form of political and economic organization in which a workplace or municipality is governed by a council made up of workers or their elected delegates. The workers within each council decide on what thei ...

s as an independent and revolutionary alternative to established trade unions and political parties.

In the Winter 1940/41 issue of ''Solidarity'', the APCF argued that "the recent Spanish tragedy n which

N, or n, is the fourteenth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''en'' (pronounced ), plural ''ens''.

History

...

the incensed ruling class repudiated even their own bourgeois legality and unleashed the most bloody butchery of the proletariat the world has ever witnessed" had proven their case of parliamentarism being a dead-end. They criticised the Socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

and Communist Parties

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. A ...

for their respective insistence on the need for a "revolutionary parliament" or "workers' government" to replace the Churchill war ministry

The Churchill war ministry was the United Kingdom's coalition government for most of the Second World War from 10 May 1940 to 23 May 1945. It was led by Winston Churchill, who was appointed Prime Minister by King George VI following the resigna ...

, declaring that "at the first threat of resistance to their will, they would immediately establish a military dictatorship

A military dictatorship is a dictatorship in which the military exerts complete or substantial control over political authority, and the dictator is often a high-ranked military officer.

The reverse situation is to have civilian control of the m ...

and by sheer weight of arms smash any attempt at progressive legislation." The APCF noted that in Britain at the time, parliament was only being consulted after events had already occurred. This led them to adopt the position that Guy Aldred

Guy Alfred Aldred (often Guy A. Aldred; 5 November 1886 – 16 October 1963) was a British anarcho-communist and a prominent member of the Anti-Parliamentary Communist Federation (APCF). He founded the Bakunin Press publishing house and edited ...

had taken when he left the Federation to found the USM: that parliamentarism was obsolete, therefore taking an anti-parliamentary position was no longer necessary. This became the impetus for the APCF changing its name to the Workers' Revolutionary League (WRL) in October 1941.

In order to coordinate resistance to the war effort, the WRL came together with the USM and the GAF to organise the Scottish No-Conscription League, in which the WRL's Willie McDougall served as chair for a time. A conscientious objector from the WRL, William Dick, defended himself in front of a military tribunal

Military justice (also military law) is the legal system (bodies of law and procedure) that governs the conduct of the active-duty personnel of the armed forces of a country. In some nation-states, civil law and military law are distinct bodie ...

in June 1942 on anarcho-pacifist grounds, declaring his moral opposition to war, the state and violence in general, which granted him an unconditional exemption from conscription.

In October 1942, the WRL established one of its main initiatives to combat sectarianism: the Workers' Open Forum, a weekly meeting open to all parties organised on the model of a workers' council. The Forum invited speakers from GAF and the USM, but also from further afield groups such as the Socialist Party of Great Britain

The Socialist Party of Great Britain (SPGB) is a socialist political party in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1904 as a split from the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), it advocates using the ballot box for revolutionary purposes and oppos ...

(SPGB), Socialist Labour Party (SLP), Workers' International League (WIL), Independent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

(ILP), Common Wealth Party

The Common Wealth Party (CW) was a socialist political party in the United Kingdom with parliamentary representation from the middle of the Second World War until the year after its end. Thereafter it continued in being, essentially as a pre ...

(CWP), Peace Pledge Union

The Peace Pledge Union (PPU) is a non-governmental organisation that promotes pacifism, based in the United Kingdom. Its members are signatories to the following pledge: "War is a crime against humanity. I renounce war, and am therefore determine ...

(PPU), as well as a number of secularists

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on secular, naturalistic considerations.

Secularism is most commonly defined as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state, and may be broadened to a sim ...

, Georgists

Georgism, also called in modern times Geoism, and known historically as the single tax movement, is an economic ideology holding that, although people should own the value they produce themselves, the economic rent derived from land—including ...

and industrial unionists. Over time, the WRL's activities became more and more subordinated to the "interests of the Workers' Open Forum."

By the end of the war, the Workers' Revolutionary League had dissolved itself almost entirely into the activities of the Workers' Open Forum, continuing to provide a regular meeting space in Glasgow until the late 1950s. John Taylor Caldwell commented that the closure of the Open Forum marked the end of an era, one in which public speaking

Public speaking, also called oratory or oration, has traditionally meant the act of speaking face to face to a live audience. Today it includes any form of speaking (formally and informally) to an audience, including pre-recorded speech deliver ...

began to die out as audiences left the inner cities for the suburbs. The post–World War II economic expansion

The post–World War II economic expansion, also known as the postwar economic boom or the Golden Age of Capitalism, was a broad period of worldwide economic expansion beginning after World War II and ending with the 1973–1975 recession. The U ...

brought a definitive end to the anti-parliamentary communist movement, as many of the arguments it had made during the early-20th century no longer held weight.

Positions

Anti-Parliamentarism

The APCF continued to propagate its anti-parliamentary principles, arguing that parliament was a fundamental institution of the capitalist system which could only ever serve the interests of the ruling class. It rejected the idea that parliamentarism could serve as a means for thesocialisation

In sociology, socialization or socialisation (see spelling differences) is the process of internalizing the norms and ideologies of society. Socialization encompasses both learning and teaching and is thus "the means by which social and cultur ...

of the means of production

The means of production is a term which describes land, labor and capital that can be used to produce products (such as goods or services); however, the term can also refer to anything that is used to produce products. It can also be used as an ...

, holding instead that this could only be brought about through spontaneous direct action

Direct action originated as a political activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest, in contrast to those actions that appeal to oth ...

by the working class itself, which would eventually result in the dissolution and replacement of institutions (including parliament) with a network of workers' council

A workers' council or labor council is a form of political and economic organization in which a workplace or municipality is governed by a council made up of workers or their elected delegates. The workers within each council decide on what thei ...

s. In an issue of the ''Commune'', the APCF declared that "the parliamentary runner seeks not to emancipate the workers but to elevate himself" and warned that participation in parliamentary politics would inevitably lead to the participant gravitating towards reformism

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can eve ...

, careerism

Careerism is the propensity to pursue career advancement, power, and prestige outside of work performance.

Cultural environment

Cultural factors influence how careerists view their occupational goals. How an individual interprets the term "caree ...

and opportunism

Opportunism is the practice of taking advantage of circumstances – with little regard for principles or with what the consequences are for others. Opportunist actions are expedient actions guided primarily by self-interested motives. The term ...

.

They also argued that parliamentarism was a distraction, in which working class voters were dealt with "the impossible task of discovering honest representatives to play at capitalist legislation, instead of addressing itself to the Socialist education of the masses". To the APCF, parliamentary political activity meant delegating tasks to leaders, where anti-parliamentary political activity meant the working classes themselves directly taking on those tasks, thus parliamentarism had to be opposed as it "empties the proletariat of all power, all authority, all initiative". The APCF therefore rejected the Socialist Party of Great Britain

The Socialist Party of Great Britain (SPGB) is a socialist political party in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1904 as a split from the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), it advocates using the ballot box for revolutionary purposes and oppos ...

(SPGB) assertion of revolutionary parliamentarism, as they believed it would disempower workers by delegating their own tasks to the individuals that ran for election, and labelled all left-wing advocates of parliamentarism as "counter-revolutionaries

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revoluti ...

".

Position on Totalitarianism

The APCF analyzedtotalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

to be a product of capitalism's boom and bust cycles, as when capitalism tended towards monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situati ...

, democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose gov ...

became incompatible with the new monopolistic economy, leading to the institution of dictatorship

A dictatorship is a form of government which is characterized by a leader, or a group of leaders, which holds governmental powers with few to no limitations on them. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship are ...

and the outbreak of war as a means to pacify the working classes. A member of the APCF furthered the position that totalitarianism was a means for capitalism to preserve itself through a period of crisis, stating that "capitalism in crisis cannot afford to indulge in democracy".

The APCF considered that the warring states were all equally capitalist and equally totalitarian, arguing that the needs of wartime were accelerating the development of the democratic powers towards totalitarianism, a position summed up in their statement that "Democratic capitalism can only fight fascist capitalism by itself becoming fascist." This view was supported by Ernst Schneider, a seaman and veteran of the German Revolution

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

that had joined the group following his departure from Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, who stated in 1944 that "under the smokescreen of freeing Europe from "totalitarianism", this very form of monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situati ...

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for Profit (economics), profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, pric ...

is developing everywhere." Schneider went on to predict that nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

was inevitable and that what had previously happened in the Axis states was already developing in the Allied states.

The APCF took the implementation of Defence Regulation 18B

Defence Regulation 18B, often referred to as simply 18B, was one of the Defence Regulations used by the British Government during and before the Second World War. The complete name for the rule was Regulation 18B of the Defence (General) Regula ...

as evidence of their position on the development of totalitarianism in Britain, due particularly to its introduction of conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

. In response, it reprinted some anti-war remarks made by James Connolly

James Connolly ( ga, Séamas Ó Conghaile; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was an Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. Born to Irish parents in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, Connolly left school for working life at the a ...

in 1917: "In the name of freedom from militarism it establishes military rule; battling for progress it abolishes trial by jury; and waging war for enlightened rule it tramples the freedom of the press under the heel of a military despot."

Position on Vanguardism

The role of political parties in the labour movement was of particular interest to the APCF, which published in its journal ''Solidarity'' a debate between the

The role of political parties in the labour movement was of particular interest to the APCF, which published in its journal ''Solidarity'' a debate between the council communists

Council communism is a current of communist thought that emerged in the 1920s. Inspired by the November Revolution, council communism was opposed to state socialism and advocated workers' councils and council democracy. Strong in Germany a ...

Anton Pannekoek

Antonie “Anton” Pannekoek (; 2 January 1873 – 28 April 1960) was a Dutch astronomer, philosopher, Marxist theorist, and socialist revolutionary. He was one of the main theorists of council communism (Dutch: ''radencommunisme'').

Biograp ...

and Paul Mattick

Paul Mattick Sr. (March 13, 1904 – February 7, 1981) was a German-American Marxist political writer and social revolutionary, whose thought can be placed within the council communist and left communist traditions.

Throughout his life, Mattic ...

, who rejected the party form, and the De Leonist Frank Maitland

Frank or Franks may refer to:

People

* Frank (given name)

* Frank (surname)

* Franks (surname)

* Franks, a medieval Germanic people

* Frank, a term in the Muslim world for all western Europeans, particularly during the Crusades - see Farang

Curr ...

, who argued in its favour. The position of the APCF itself lay somewhere between the two, arguing that the development of class consciousness

In Marxism, class consciousness is the set of beliefs that a person holds regarding their social class or economic rank in society, the structure of their class, and their class interests. According to Karl Marx, it is an awareness that is key to ...

could only be organically induced by material conditions rather than by an organisation, while also holding that workers that had already developed class consciousness needed to unite together to lead those that had not. Like Pannekoek's conception of a revolutionary organisation, which the APCF sought to emulate, its goal would not be to seek power for itself but to serve as a propaganda organ to "educate, agitate and enthuse; perhaps even to inspire" the working classes to take self-organised direct action

Direct action originated as a political activist term for economic and political acts in which the actors use their power (e.g. economic or physical) to directly reach certain goals of interest, in contrast to those actions that appeal to oth ...

. In their arguments against vanguardism, the APCF stated:

The APCF took a hardline against sectarianism during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, opening up its journal ''Solidarity'' as a platform to a variety of left-wing positions and personalities, including anarcho-communists

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains res ...

, council communists

Council communism is a current of communist thought that emerged in the 1920s. Inspired by the November Revolution, council communism was opposed to state socialism and advocated workers' councils and council democracy. Strong in Germany a ...

, De Leonists

De Leonism, also known as Marxism-De Leonism, is a Marxist tendency developed by Curaçaoan-American trade union organizer and Marxist theoretician Daniel De Leon. De Leon was an early leader of the first American socialist political party, ...

, Trotskyists

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a re ...

, Marxists

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectic ...

and members of the ILP

''ilp.'' () is the debut album by record producer and musician Kwes. It was released on 14 October 2013 on Warp Records. The release is a follow up to his second EP release '' Meantime''. The record's title ''ilp'' refers literally to the record ...

. The APCF strongly rejected vanguardism

Vanguardism in the context of Leninist revolutionary struggle, relates to a strategy whereby the most class-conscious and politically "advanced" sections of the proletariat or working class, described as the revolutionary vanguard, form organi ...

, which it believed forced revolutionary groups into competition with one another, claiming that as no single group can hold correct positions on every issue or contain all the best elements of the working class, these groups needed to co-operate with each other in an alliance with a commonly agreed-upon programme. This anti-sectarian attitude extended to collaboration with the USM and GAF, with the APCF's Willie McDougall even going out of his way to distribute the USM's ''Word'' and the GAF's '' War Commentary''.

Position on the Soviet Union

Although the APCF had initially supported the

Although the APCF had initially supported the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, by this time accounts of repression were starting to emerge from the country, with its newspaper the ''Commune'' even publishing letters from anarchists reporting that revolutionaries were suffering political persecution

Political repression is the act of a state entity controlling a citizenry by force for political reasons, particularly for the purpose of restricting or preventing the citizenry's ability to take part in the political life of a society, thereby ...

, despite Aldred's own skepticism of such reports. Aldred was criticised for this by Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman (November 21, 1870June 28, 1936) was a Russian-American anarchist and author. He was a leading member of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century, famous for both his political activism and his writing.

B ...

and Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the ...

in their correspondence with the paper, to which Aldred responded by fiercely denouncing them. In May 1925 the APCF re-affirmed its defense of the Soviet Union, but also called on the Comintern to "abandon its opposition to left communism

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left wing of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices espoused by Marxist–Leninists and social democrats. Left communists assert positions which they reg ...

" so that the APCF could unite alongside it.

But as more evidence of state repression accumulated over time, Aldred and the APCF were no longer able to continue ignoring or disputing reports of persecution and finally started to denounce the Bolsheviks. By November 1925, the APCF had denounced the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

as a "counter-revolution

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revoluti ...

" and finally began to display solidarity with its "comrades rotting in Soviet prisons", taking up the defense of Gavril Myasnikov

Gavril Ilyich Myasnikov (russian: Гавриил Ильич Мясников; February 25, 1889, Chistopol, Kazan Governorate – November 16, 1945, Moscow), also transliterated as Gavriil Il'ich Miasnikov, was a Russian communist revolutionary ...

, whose Workers Group had formed a left-communist opposition to the New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

. Aldred later apologised for his earlier unwillingness to believe the allegations and admitted that his skepticism was "most unjust to the imprisoned and persecuted comrades in Soviet Russia". In the ''Commune'' of that month, the APCF denounced the pro-Soviet CPGB as standing for "bureaucracy

The term bureaucracy () refers to a body of non-elected governing officials as well as to an administrative policy-making group. Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments staffed with non-elected offi ...

, capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for Profit (economics), profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, pric ...

and militarism

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mili ...

" and claimed that it had "nothing in common with Communism or the working-class struggle".

Adopting the critical line that had previously been taken up by the Communist Workers' Party (CWP), the APCF held that the Soviet Union was not in fact communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

but a state capitalist

State capitalism is an economic system in which the state undertakes business and commercial (i.e. for-profit) economic activity and where the means of production are nationalized as state-owned enterprises (including the processes of capital ac ...

system, where "The State

A state is a centralized political organization that imposes and enforces rules over a population within a territory. There is no undisputed definition of a state. One widely used definition comes from the German sociologist Max Weber: a "stat ...

..owns the means of production

The means of production is a term which describes land, labor and capital that can be used to produce products (such as goods or services); however, the term can also refer to anything that is used to produce products. It can also be used as an ...

in opposition to the workers themselves." The APCF argued that with the introduction of the New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) () was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 as a temporary expedient. Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, ...

(NEP) "peasant-bourgeois" interests had triumphed over "proletarian-communism", due to a compromise between the two that had been sought by Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

, and concluded that "the interests of the peasants cannot be reconciled with those of the industrial proletariat".

When the activities of Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

's Left Opposition