Anti-American sentiment in Korea on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anti-American sentiments in Korea began with the earliest contact between the two nations and continued after the

Anti-American sentiments in Korea began with the earliest contact between the two nations and continued after the

After the Japanese defeat in World War II the United States set up a self-declared government in Korea which pursued a number of very unpopular policies. In brief, the military government first supported the same Japanese colonial government. Then, it removed the Japanese officials but retained them as advisors. The Koreans, before the Americans had arrived, had developed their own popular-based government, the

After the Japanese defeat in World War II the United States set up a self-declared government in Korea which pursued a number of very unpopular policies. In brief, the military government first supported the same Japanese colonial government. Then, it removed the Japanese officials but retained them as advisors. The Koreans, before the Americans had arrived, had developed their own popular-based government, the

The No Gun Ri Massacre occurred on July 26–29, 1950, early in the

The No Gun Ri Massacre occurred on July 26–29, 1950, early in the

(KOREAN CENTRAL NEWS AGENCY) On November 20, 1982, arsonists fired American Cultural Center in Gwangju ( ko) for the second time. In September 1983, Daegu's American Cultural Center was bombed ( ko). In May 1985 in

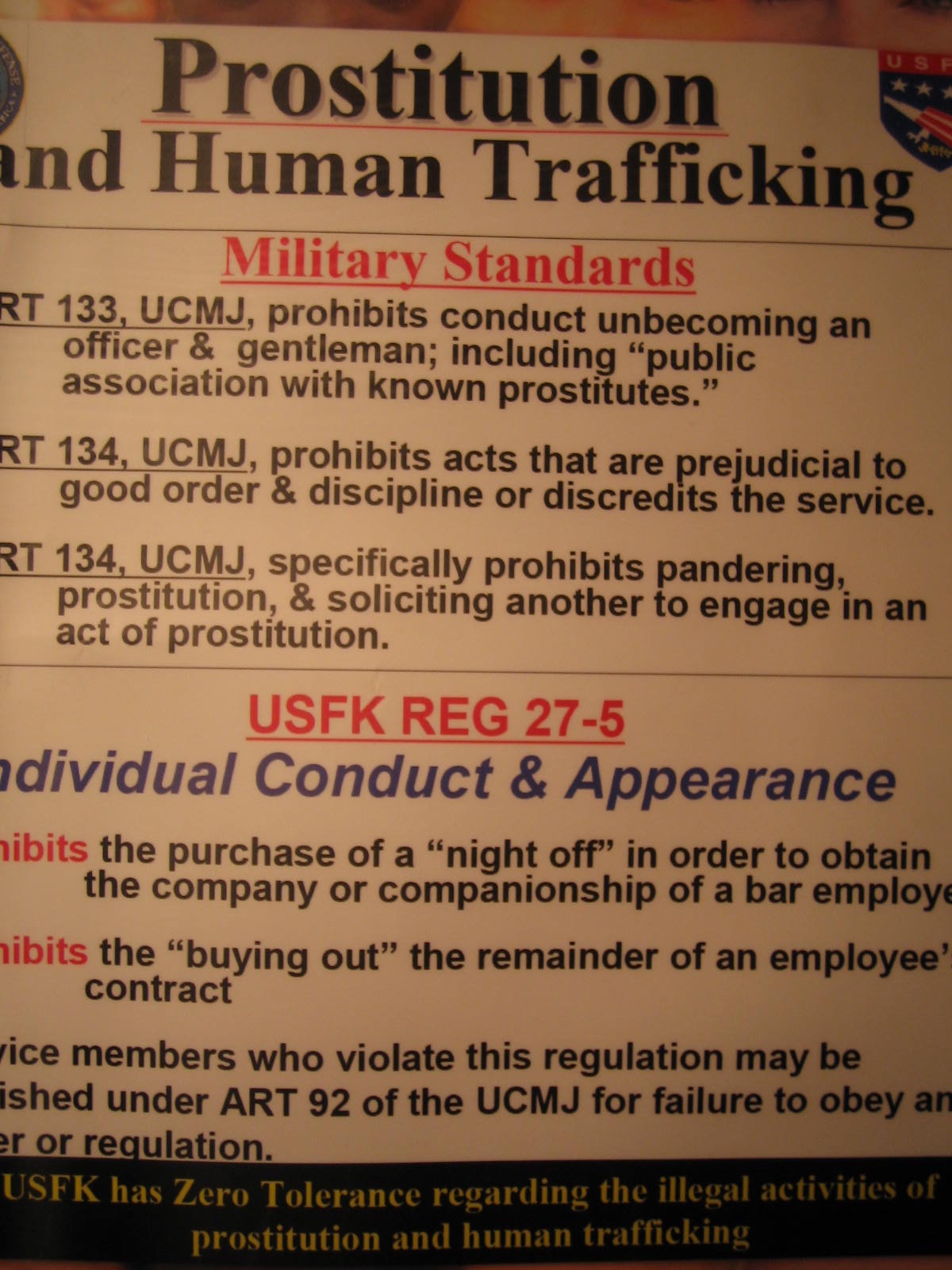

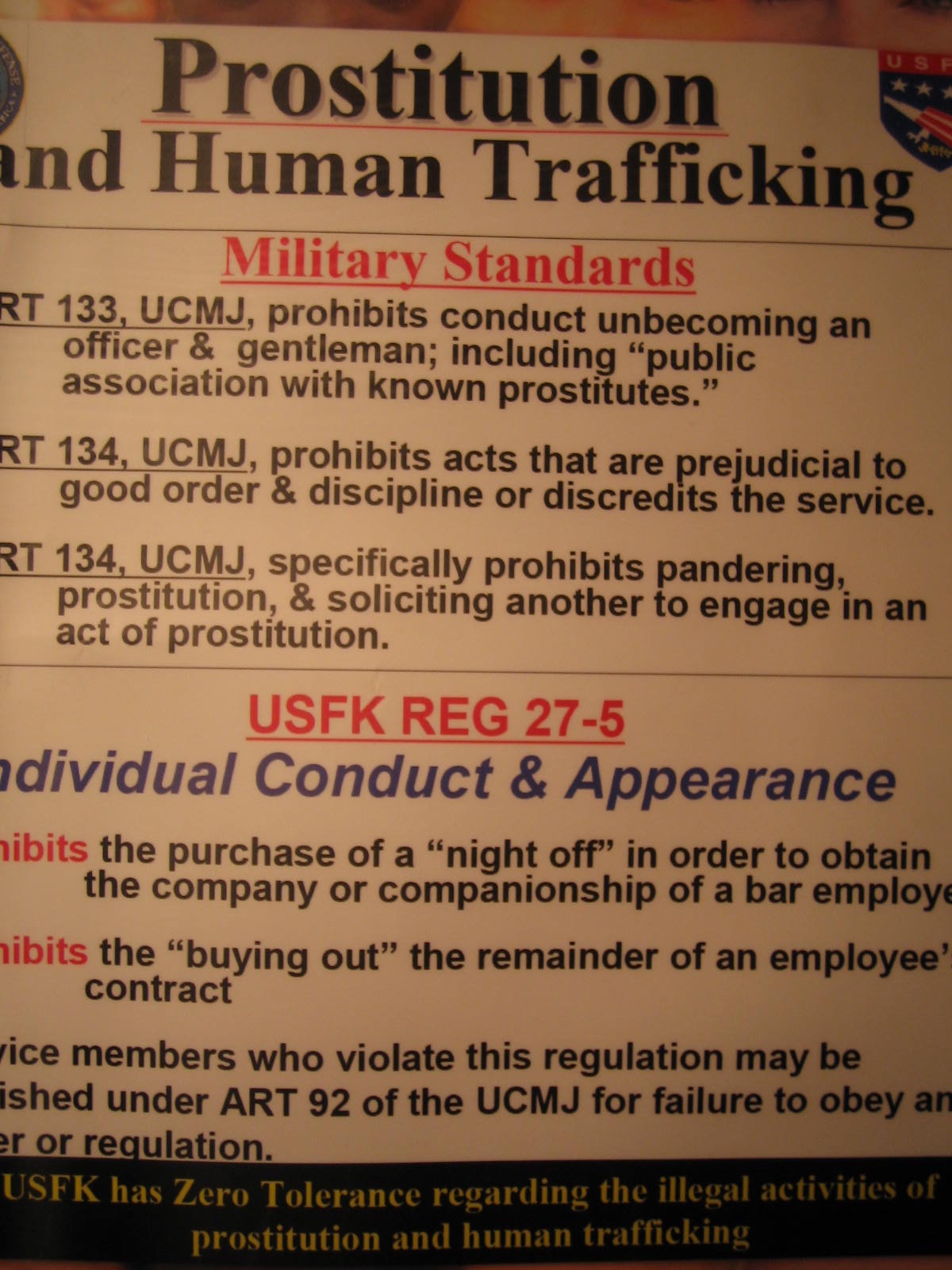

During the early 1990s, former victims of forced prostitution became a symbol of Anti-American nationalism.

Former military prostitutes are seeking compensation and apologies as they claim to have been the biggest sacrifice for the South Korea-United States alliance. Some South Korean women report being encouraged to provide sexual services for American soldiers. As a result of this practice, some women were killed by soldiers or committed suicide. American military police and South Korean officials regularly raided clubs looking for women who were thought to be spreading venereal diseases, locking them up under guard in so-called monkey houses with barred windows. There, the prostitutes were forced to take medications until they were well.

During the early 1990s, former victims of forced prostitution became a symbol of Anti-American nationalism.

Former military prostitutes are seeking compensation and apologies as they claim to have been the biggest sacrifice for the South Korea-United States alliance. Some South Korean women report being encouraged to provide sexual services for American soldiers. As a result of this practice, some women were killed by soldiers or committed suicide. American military police and South Korean officials regularly raided clubs looking for women who were thought to be spreading venereal diseases, locking them up under guard in so-called monkey houses with barred windows. There, the prostitutes were forced to take medications until they were well.

In 2002,

In 2002,

U.S. Ambassador to South Korea Is Hospitalized After Knife Attack

''New York Times'', March 4, 2015. The assailant, Kim Ki-jong, is a member of Uri Madang, a progressive cultural organization opposed to the

South Korea

주한미군범죄근절운동본부

Kenneth L. Markle: Sadistic Murderer or Scapegoat?

(자주민보) – Murdered picture by a US Soldier {{Asia in topic, Anti-American sentiment in

Anti-American sentiments in Korea began with the earliest contact between the two nations and continued after the

Anti-American sentiments in Korea began with the earliest contact between the two nations and continued after the division of Korea

The division of Korea began with the defeat of Japan in World War II. During the war, the Allied leaders considered the question of Korea's future after Japan's surrender in the war. The leaders reached an understanding that Korea would be l ...

. In both North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and T ...

and South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and sharing a land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed by the Yellow Sea, while its eas ...

, anti-Americanism

Anti-Americanism (also called anti-American sentiment) is prejudice, fear, or hatred of the United States, its government, its foreign policy, or Americans in general.

Political scientist Brendon O'Connor at the United States Studies Centr ...

after the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

has focused on the presence and behavior of American military personnel (USFK

United States Forces Korea (USFK) is a sub-unified command of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM). USFK is the joint headquarters for U.S. combat-ready fighting forces and components under the ROK/US Combined Forces Command (CFC) – a ...

), aggravated especially by high-profile crimes by U.S. service members, with various crimes including rape

Rape is a type of sexual assault usually involving sexual intercourse or other forms of sexual penetration carried out against a person without their consent. The act may be carried out by physical force, coercion, abuse of authority, or ...

and assault, among others. The 2002 Yangju highway incident

The Yangju highway incident, also known as the Yangju training accident or Highway 56 Accident, occurred on June 13, 2002, in Yangju, Gyeonggi-do, South Korea. A United States Army armored vehicle-launched bridge, returning to base in Uijeongbu ...

especially ignited Anti-American passions. Anti-American sentiments have served as catalysts for protests such as the Daechuri Protest, which challenged the expansion of the U.S military base, Camp Humphreys

Camp Humphreys ( ko, 캠프 험프리스), also known as United States Army Garrison-Humphreys (USAG-H), is a United States Army garrison located near Anjeong-ri and Pyeongtaek metropolitan areas in South Korea. Camp Humphreys is home to ...

. The ongoing U.S. military presence in South Korea, especially at Yongsan Garrison

Yongsan Garrison ( ko, 용산기지; Hanja: ), meaning "dragon hill garrison," is an area located in the Yongsan District of central Seoul, South Korea. The site served as the headquarters for U.S. military forces stationed in South Korea, known ...

(on a base previously used by the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor o ...

from 1910–1945) in central Seoul

Seoul (; ; ), officially known as the Seoul Special City, is the capital and largest metropolis of South Korea.Before 1972, Seoul was the ''de jure'' capital of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) as stated iArticle 103 of ...

, remains a contentious issue. However, 74% of South Koreans have a favorable view of the U.S., making South Korea one of the most pro-American countries in the world.

While protests have arisen over specific incidents, they are often reflective of deeper historical, anti-Western sentiment

Anti-Western sentiment, also known as Anti-Atlanticism or Westernophobia, refers to broad opposition, bias, or hostility towards the people, culture, or policies of the Western world.

Definition and usage

In many modern cases, anti-Western s ...

. Robert Hathaway, director of the Wilson Center

The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars (or Wilson Center) is a quasi-government entity and think tank which conducts research to inform public policy. Located in the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center in Wash ...

's Asia program, suggests: "the growth of anti-American sentiment in both Japan and South Korea must be seen not simply as a response to American policies and actions, but as reflective of deeper domestic trends and developments within these Asian countries." Korean anti-Americanism after the war was fueled by American military presence and support for authoritarian rule under Park Chung-hee, a fact still evident during the country's democratic transition in the 1980s. Speaking to the Wilson Center, Katharine Moon notes that while the majority of South Koreans support the American alliance "anti-Americanism also represents the collective venting of accumulated grievances that in many instances have lain hidden for decades." Within the last decade, many Korean dramas and films have portrayed Americans in a negative light, which may also contribute to the harboring of anti-American views among Koreans.

Taft–Katsura Agreement

The Taft–Katsura Agreement (Japanese: 桂・タフト協定 Katsura-Tafuto Kyōtei) was a set of notes taken during conversations betweenUnited States Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

and Prime Minister of Japan

The prime minister of Japan (Japanese: 内閣総理大臣, Hepburn: ''Naikaku Sōri-Daijin'') is the head of government of Japan. The prime minister chairs the Cabinet of Japan and has the ability to select and dismiss its Ministers of Sta ...

Katsura Taro Katsura or Katsuura may refer to:

Architecture

*The Katsura imperial villa, one of Japan's most important architectural treasures, and a World Heritage Site

Botany

*Katsura, the common name for Cercidiphyllum, a genus of two species of trees nativ ...

on 29 July 1905. The notes were discovered in 1924; there was never a signed agreement or secret treaty, only a memorandum

A memorandum ( : memoranda; abbr: memo; from the Latin ''memorandum'', "(that) which is to be remembered") is a written message that is typically used in a professional setting. Commonly abbreviated "memo," these messages are usually brief and ...

of a conversation regarding Japanese-American relations

are Americans of Japanese ancestry. Japanese Americans were among the three largest Asian American ethnic communities during the 20th century; but, according to the 2000 census, they have declined in number to constitute the sixth largest Asi ...

.

Some Korean historians have assumed that, in the discussions, the United States recognized Japan's sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal a ...

in Korea; in exchange, Japan recognized the United States's sphere of influence in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

. However, American historians examining official records report no agreement was ever made — the two men discussed current events but came to no new policy or agreement. They both restated the well-known official policies of their own governments. Indeed, Taft was very careful to indicate these were his private opinions and he was not an official representative of the U.S. government (Taft was Secretary of War, not US Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

).

This agreement evoked negative Korean reaction. Some Korean historians (e.g., Ki-baik Lee, author of ''A New History of Korea'') believe that the Taft–Katsura Agreement violated the Korean–American Treaty of Amity and Commerce

Korean Americans are Americans of Korean ancestry (mostly from South Korea). In 2015, the Korean-American community constituted about 0.56% of the United States population, or about 1.82 million people, and was the fifth-largest Asian American ...

signed at Incheon on May 22, 1882, because the Joseon Government considered that treaty constituted a de facto mutual defense treaty while the Americans did not. The Joseon Dynasty

Joseon (; ; Middle Korean: 됴ᇢ〯션〮 Dyǒw syéon or 됴ᇢ〯션〯 Dyǒw syěon), officially the Great Joseon (; ), was the last dynastic kingdom of Korea, lasting just over 500 years. It was founded by Yi Seong-gye in July 1392 and r ...

, however, ended in 1897. In recent years, while the Taft–Katsura Agreement is all but an obscure footnote in history, the Agreement is attacked by some left-leaning Korean activists as an example of how the United States cannot be trusted with regards to Korean security and sovereignty issues.

Pre-Korean War

After the Japanese defeat in World War II the United States set up a self-declared government in Korea which pursued a number of very unpopular policies. In brief, the military government first supported the same Japanese colonial government. Then, it removed the Japanese officials but retained them as advisors. The Koreans, before the Americans had arrived, had developed their own popular-based government, the

After the Japanese defeat in World War II the United States set up a self-declared government in Korea which pursued a number of very unpopular policies. In brief, the military government first supported the same Japanese colonial government. Then, it removed the Japanese officials but retained them as advisors. The Koreans, before the Americans had arrived, had developed their own popular-based government, the People's Republic of Korea

The People's Republic of Korea (PRK) was a short-lived provisional government that was organized at the time of the surrender of the Empire of Japan at the end of World War II. It was proclaimed on 6 September 1945, as Korea was being divided ...

, which is not to be confused with the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, the official name of North Korea. The popular government was ignored, censored, and then eventually outlawed by decree of the U.S. military government. The military government also created an advisory council for which the majority of seats were offered to the nascent Korea Democratic Party

The Korea Democratic Party (, KDP) was the leading opposition party in the first years of the First Republic of Korea. It existed from 1945 to 1949, when it merged with other opposition parties.

The U.S. military government has defined the ...

(KDP) which mainly consisted of large landowners, wealthy businesspeople, and former colonial officials. The military government, and this advisory council, set up elections for a legislature.

The elections were boycotted

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict som ...

and protested throughout the country by the peasantry. The uprising was suppressed with police, U.S. troops and tanks, and declarations of martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

. The only representatives elected that were not of the KDP or its allies were from Jeju-do. Furthermore, the U.S.'s refusal to consult existing popular organizations in the south, as agreed upon at the Moscow Conference, and thus paving the way towards a divided Korea, embittered the majority of Koreans. Finally, pushing for United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

elections that would not be observed by the Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

-controlled north, over legal objections, enshrined a divided Korea, which the majority of Koreans opposed.

No Gun Ri massacre

The No Gun Ri Massacre occurred on July 26–29, 1950, early in the

The No Gun Ri Massacre occurred on July 26–29, 1950, early in the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

, when South Korean refugees were killed by the 7th U.S. Cavalry Regiment

The 7th Cavalry Regiment is a United States Army cavalry regiment formed in 1866. Its official nickname is "Garryowen", after the Ireland, Irish air "Garryowen (air), Garryowen" that was adopted as its march tune.

The regiment participated i ...

(and a U.S. air attack) at a railroad bridge near the village of No Gun Ri (revised Romanization Nogeun-ri

Nogeun-ri, also No Gun Ri, is a village in Hwanggan- myeon, Yeongdong County, North Chungcheong Province in central South Korea. The village was the closest named place to the site of the No Gun Ri Massacre (July 26–29, 1950) during the Korea ...

), southeast of Seoul. In 2005, the South Korean government certified the names of 163 dead or missing (mostly women, children and old men) and 55 wounded. It said many other victims' names were not reported. Survivors generally estimated 400 dead. The U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

cites the number of casualties as "unknown." Along with the My Lai Massacre

My or MY may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* My (radio station), a Malaysian radio station

* Little My, a fictional character in the Moomins universe

* ''My'' (album), by Edyta Górniak

* ''My'' (EP), by Cho Mi-yeon

Business

* Market ...

in Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

, it was one of the largest single massacres of civilians by U.S. forces in the 20th century.

The civilian killings gained widespread attention when the Associated Press published articles in 1999 in which 7th Cavalry veterans corroborated survivors' accounts, articles that later won the Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting. 7th Cavalry veteran Joe Jackman states, "there was kids out there, it didn't matter what it was, eight to 80, blind, crippled or crazy, they shot 'em all." The AP also uncovered warfront orders to fire on refugees, given out of fear of enemy North Korean infiltration. After years of rejecting claims by survivors, the Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a meton ...

conducted an investigation and, in 2001, acknowledged the killings, but referred to the three-day event as "an unfortunate tragedy inherent to war and not a deliberate killing." The U.S. rejected survivors' demands for an apology and compensation. Inconsistencies with the Pentagon's investigation led to Korean War veteran Pete McCloskey (who had been brought in to advise on the report) state, "the government will always lie about embarrassing matters."

South Korean investigators disagreed with Pentagon findings, saying they believed 7th Cavalry troops were ordered to fire on the refugees. The survivors' group called the U.S. report a "whitewash

Whitewash, or calcimine, kalsomine, calsomine, or lime paint is a type of paint made from slaked lime (calcium hydroxide, Ca(OH)2) or chalk calcium carbonate, (CaCO3), sometimes known as "whiting". Various other additives are sometimes used.

...

." Additional archival documents later emerged showing U.S. commanders ordering the shooting of refugees during this period, declassified documents found but not disclosed by Pentagon investigators. Among them was a report by the U.S. ambassador in South Korea in July 1950 that the U.S. military had adopted a theater

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perform ...

-wide policy of firing on approaching refugee groups. Despite demands, the U.S. investigation was not reopened.

Prompted by the exposure of No Gun Ri, survivors of similar alleged incidents in 1950–1951 filed reports with the Seoul government. In 2008 an investigative commission said more than 200 cases of alleged large-scale civilian killings by the U.S. military had been registered, mostly air attacks. More documents detailing refugee 'kill' orders were unearthed at the U.S. national archives and point to the widespread targeting of refugees by commanders well after No Gun Ri massacre. In August 1950 there were orders detailing that refugees crossing the Naktong River be shot. Later in the same month, General Gay ordered artillery units to target civilians on the battlefield. In January 1951, the U.S. 8th Army was detailing all units in Korea that refugees be attacked with all available fire including bombing. In August 1950, 80 civilians are reported to have been killed while seeking sanctuary in a shrine by the village of Kokaan-Ri, near Masan in South Korea. Other survivors recall 400 civilians killed by U.S. naval artillery on the beaches near the port of Pohang in September 1950.

Sinchon Massacre

North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and T ...

claims that US forces massacred 35,000 people at Sinchon between 17 October and 7 December 1950.

The Geneva Conference of 1954

The armistice at the end of the Korean War required that a political conference be pursued where the question of a unified Korea would be addressed. Despite many proposals for independent national elections and a unified, democratic, independent Korea no declaration for a unified Korea was adopted. Some participants and analysts blame the U.S. for obstructing efforts towards unification.American Cultural Center arson

On December 9, 1980, in Gwangju, arsonists protesting theGwangju massacre

The Gwangju Uprising was a popular uprising in the city of Gwangju, South Korea, from May 18 to May 27, 1980, which pitted local, armed citizens against soldiers and police of the South Korean government. The event is sometimes called 5·18 (M ...

, burned the American Cultural Center ( ko).

On March 12, 1982, arsonists set fire to the American Cultural Center in Busan

Busan (), officially known as is South Korea's most populous city after Seoul, with a population of over 3.4 million inhabitants. Formerly romanized as Pusan, it is the economic, cultural and educational center of southeastern South Korea, ...

. They killed one and injured several others. Moon Pu-shik and Kim Hyon-jang were sentenced to death but later commuted to life sentences and then to 20 years.Anniversary of Arson Attack on Pusan "American Cultural-Service" Observed(KOREAN CENTRAL NEWS AGENCY) On November 20, 1982, arsonists fired American Cultural Center in Gwangju ( ko) for the second time. In September 1983, Daegu's American Cultural Center was bombed ( ko). In May 1985 in

Seoul

Seoul (; ; ), officially known as the Seoul Special City, is the capital and largest metropolis of South Korea.Before 1972, Seoul was the ''de jure'' capital of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) as stated iArticle 103 of ...

, American Cultural Center was seized.

On April 23, 2013, in Daegu, two anti-U.S. arsonists mistakenly attacked a cram school called the American Cultural Center.

Military prostitutes

During the early 1990s, former victims of forced prostitution became a symbol of Anti-American nationalism.

Former military prostitutes are seeking compensation and apologies as they claim to have been the biggest sacrifice for the South Korea-United States alliance. Some South Korean women report being encouraged to provide sexual services for American soldiers. As a result of this practice, some women were killed by soldiers or committed suicide. American military police and South Korean officials regularly raided clubs looking for women who were thought to be spreading venereal diseases, locking them up under guard in so-called monkey houses with barred windows. There, the prostitutes were forced to take medications until they were well.

During the early 1990s, former victims of forced prostitution became a symbol of Anti-American nationalism.

Former military prostitutes are seeking compensation and apologies as they claim to have been the biggest sacrifice for the South Korea-United States alliance. Some South Korean women report being encouraged to provide sexual services for American soldiers. As a result of this practice, some women were killed by soldiers or committed suicide. American military police and South Korean officials regularly raided clubs looking for women who were thought to be spreading venereal diseases, locking them up under guard in so-called monkey houses with barred windows. There, the prostitutes were forced to take medications until they were well.

Yun Geum-i murder case

Yun Geum-i murder case was a murder case on October 28, 1992, at a camptown in Dongducheon,Gyeonggi

Gyeonggi-do (, ) is the most populous province in South Korea. Its name, ''Gyeonggi'', means "京 (the capital) and 畿 (the surrounding area)". Thus, ''Gyeonggi-do'' can be translated as "Seoul and the surrounding areas of Seoul". Seoul, the na ...

, South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and sharing a land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed by the Yellow Sea, while its eas ...

. Bar employee Yun Geum-i (), then 26 years old, was murdered by private Kenneth Markle (Kenneth Lee Markle III), a member of the USFK

United States Forces Korea (USFK) is a sub-unified command of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM). USFK is the joint headquarters for U.S. combat-ready fighting forces and components under the ROK/US Combined Forces Command (CFC) – a ...

2nd Division.

This case raised the issue of the U.S. Forces in South Korea as a social problem, and became an opportunity to start an earnest revision movement to U.S.–South Korea Status of Forces Agreement. Private Markle was sentenced to 15 years and he was imprisoned in Cheonan prison on May 17, 1994. He was released on parole

Parole (also known as provisional release or supervised release) is a form of early release of a prison inmate where the prisoner agrees to abide by certain behavioral conditions, including checking-in with their designated parole officers, or ...

on August 14, 2006, and returned to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

.

Yangju highway incident

On June 13, 2002, a U.S. military vehicle fatally injured two 14-year-old South Korean girls, Shin Hyo-sun (신효순) and Shim Mi-seon (심미선), who were walking along a street in Euijeongbu, Gyeonggi-do. The incident provoked anti-American sentiment in South Korea when a U.S military court found the soldiers involved, who were sent back to the United States immediately after the decision, not guilty. This prompted hundreds of thousands of South Koreans to protest against the U.S Army's continued presence.PSY's anti-American performance

In 2002,

In 2002, PSY

Park Jae-sang (, ; born December 31, 1977), known professionally as Psy (stylized in all caps as PSY) (; ; ), is a South Korean singer, rapper, songwriter, and record producer. Psy is known domestically for his humorous videos and stage per ...

and some pop stars participated in an anti-American

Anti-Americanism (also called anti-American sentiment) is prejudice, fear, or hatred of the United States, its government, its foreign policy, or Americans in general.

Political scientist Brendon O'Connor at the United States Studies Centr ...

concert in response to the incident. PSY lifted up a model of a U.S. M2 Bradley

The M2 Bradley, or Bradley IFV, is an American infantry fighting vehicle that is a member of the Bradley Fighting Vehicle family. It is manufactured by BAE Systems Land & Armaments, which was formerly United Defense.

The Bradley is designed ...

armoured vehicle and smashed it, and rapped the song "Dear American". The song was written by a South Korean band to condemn the United States and its military for its role in the Iraq War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Iraq War {{Nobold, {{lang, ar, حرب العراق (Arabic) {{Nobold, {{lang, ku, شەڕی عێراق ( Kurdish)

, partof = the Iraq conflict and the War on terror

, image ...

. The anti-American lyrics saying, "Kill those fucking Yankees who have been torturing Iraqi captives and those who ordered them to torture," and "Kill them all slowly and painfully," as well as "daughters, mothers, daughters-in-law and fathers." In December 2012, he issued an apology to the US Military.

Apolo Ohno 2002 Winter Olympics controversy

InSalt Lake City, Utah

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the Capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Utah, most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Salt Lake County, Utah, Sal ...

, Apolo Anton Ohno

Apolo Anton Ohno (; born May 22, 1982) is an American retired short track speed skating competitor and an eight-time medalist (two gold, two silver, four bronze) in the Winter Olympics. Ohno is the most decorated American at the Winter Olympics ...

emerged as a popular athlete among US fans for reportedly charming them with his cheerful attitude and laid-back style. He became the face of short track speed skating in the US, which was a relatively new and unknown sport at the time, and carried the medal hopes of America in that sport. Ohno medaled in two events, although there was some controversy associated with the results.

In the 1500 m race, Ohno won the gold medal, with a time of 2:18.541. During the 1500 m final race, South Korean Kim Dong-sung

Kim Dong-Sung (Hangul: 김동성, Hanja: 金東聖, born 9 February 1980) is a South Korean former Short track speed skating, short track speed skater. He won a gold medal in 1000m race and silver medal in 5000m relay at the 1998 Winter Olympic ...

was first across the finish line, but was disqualified for blocking Ohno, in what is called cross tracking. Ohno was in second place with three laps remaining, and on his third attempt to pass on the final lap, Kim drifted slightly to the inside where Ohno raised his arms and came out of his crouch to signal that he was blocked. Fourth-place finisher of the same race, Fabio Carta of Italy, showed his disagreement with the decision saying that it was "absurd that the Korean was disqualified." China's Li Jiajun, who moved from bronze to silver, remained neutral saying: "I respect the decision of the referee, I'm not going to say any more." Steven Bradbury of Australia, the 1000 m gold medal winner, also shared his views: "Whether Dong-Sung moved across enough to be called for cross-tracking, I don't know, he obviously moved across a bit. It's the judge's interpretation. A lot of people will say it was right and a lot of people will say it's wrong. I've seen moves like that before that were not called. But I've seen them called too."

"Fucking USA"

" Fucking USA" is aprotest song

A protest song is a song that is associated with a movement for social change and hence part of the broader category of ''topical'' songs (or songs connected to current events). It may be folk, classical, or commercial in genre.

Among social mov ...

written by South Korean singer and activist Yoon Min-suk. Strongly anti-US foreign policy and anti-Bush, the song was written in 2002 at a time when, following the Apolo Ohno Olympic controversy and the Yangju highway incident, anti-American sentiment in South Korea reached record high levels.

''The Host''

The 2006 South Koreanmonster film

A monster movie, monster film, creature feature or giant monster film is a film that focuses on one or more characters struggling to survive attacks by one or more antagonistic monsters, often abnormally large ones. The film may also fall und ...

''The Host'' has been described as anti-American. The film was in part inspired by an incident in 2000 in which a Korean mortician working for the U.S. military in Seoul dumped a large amount of formaldehyde

Formaldehyde ( , ) (systematic name methanal) is a naturally occurring organic compound with the formula and structure . The pure compound is a pungent, colourless gas that polymerises spontaneously into paraformaldehyde (refer to section ...

down the drain. In the film the dumped chemicals engender a horrible mutated monster from the river which menaces the inhabitants of Seoul. The American military situated in South Korea is portrayed as uncaring about the effects their activities have on the locals. The chemical agent used by the American military to combat the monster in the end is named "Agent Yellow" in a thinly-veiled reference to Agent Orange was also used to satirical effect.

The CGI for the film was done by The Orphanage, which also did the CGI of ''The Day After Tomorrow

''The Day After Tomorrow'' is a 2004 American science fiction disaster film directed, co-produced, and co-written by Roland Emmerich. Based on the 1999 book '' The Coming Global Superstorm'' by Art Bell and Whitley Strieber, the film stars De ...

''. The director, Bong Joon-ho, commented on the issue: "It's a stretch to simplify ''The Host'' as an anti-American film, but there is certainly a metaphor and political commentary about the U.S." Because of its themes that can be seen as critical of the United States, the film was actually lauded by North Korean authorities, a rarity for a South Korean blockbuster film.

2008 US beef protest

Between 24 May 2008 and about 18 July 2008 inSeoul

Seoul (; ; ), officially known as the Seoul Special City, is the capital and largest metropolis of South Korea.Before 1972, Seoul was the ''de jure'' capital of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) as stated iArticle 103 of ...

, mass protests were held in Seoul against the importation of American beef.

2015 attack on the USA Ambassador

At about 7:40 a.m. on March 5, 2015,Mark Lippert

Mark William Lippert (born February 28, 1973) is an American diplomat who has worked as the vice president for international affairs at Boeing since 2017. He previously served as the United States Ambassador to South Korea from 2014 to 2017. Prio ...

, United States Ambassador to South Korea

The United States Ambassador to South Korea () is the chief diplomatic representative of the United States accredited to the Republic of Korea. The ambassador's official title is "Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the United States ...

was attacked by a knife-wielding man at a restaurant attached to Sejong Center

Sejong Center for the Performing Arts is the largest arts and cultural complex in Seoul, South Korea. It has an interior area of 53,202m². It is situated in the center of the capital, on Sejongno, a main road that cuts through the capital city o ...

in downtown Seoul, where he was scheduled to give a speech at a meeting of the Korean Council for Reconciliation and Cooperation.Choe Sang-hun & Michael D. ShearU.S. Ambassador to South Korea Is Hospitalized After Knife Attack

''New York Times'', March 4, 2015. The assailant, Kim Ki-jong, is a member of Uri Madang, a progressive cultural organization opposed to the

Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

. He inflicted wounds on Lippert's left arm as well as a four-inch cut on the right side of the ambassador's face, requiring 80 stitches. Lippert underwent surgery at Yonsei University

Yonsei University (; ) is a private research university in Seoul, South Korea. As a member of the " SKY" universities, Yonsei University is deemed one of the three most prestigious institutions in the country. It is particularly respected in th ...

's Severance Hospital

Severance Hospital is a teaching hospital located in Sinchon-dong, Seodaemun District, South Korea. It is one of the oldest and biggest university hospitals in South Korea. It has 2,437 beds and treats approximately 2,500,000 outpatients and 8 ...

in Seoul. While his injuries were not life-threatening, doctors stated that it would take several months for Lippert to regain use of his fingers. A police official said that the knife used in the attack was long and Lippert later reported that the blade penetrated to within 2 cm of his carotid artery. ABC News summarized the immediate aftermath of the attack as follows: "Ambassador Lippert, an Iraq war veteran, defended himself from the attack. Lippert was rushed to a hospital where he was treated for deep cuts to his face, his arm, and his hand. ... ekept his cool throughout the incident."

During the attack and while being subdued by security, Kim screamed that the rival Koreas should be unified and told reporters that he had attacked Lippert to protest the annual United States–South Korean joint military exercises. Kim has a record of militant Korean nationalist activism; he attacked the Japanese ambassador to South Korea in 2010 and was sentenced to a three-year suspended prison term. On September 11, 2015, Kim was sentenced to twelve years in prison for the attack.

See also

*Anti-Americanism

Anti-Americanism (also called anti-American sentiment) is prejudice, fear, or hatred of the United States, its government, its foreign policy, or Americans in general.

Political scientist Brendon O'Connor at the United States Studies Centr ...

* Anti-Japanese sentiment in Korea

* Anti-Korean sentiment in the United States

* Axis of evil

The phrase "axis of evil" was first used by U.S. President George W. Bush and originally referred to Iran, Iraq, and North Korea. It was used in Bush's State of the Union address on January 29, 2002, less than five months after the 9/11 attac ...

* Busan American Cultural Service building arson

The 1982 Busan arson attack or Busan American Council Fire Accidents (Hangeul: 부산 미국문화원 방화사건, Hanja: 釜山美國文化院放火事件) was an anti-American attack against the United States Information Service building in Bus ...

* Demonstrations at Yongsan Garrison

* Korean nationalism

Korean nationalism can be viewed in two different contexts. One encompasses various movements throughout history to maintain a Korean cultural identity, history, and ethnicity (or "race"). This ethnic nationalism was mainly forged in oppositio ...

* Minjung Party

The Progressive Party (), known as the Minjung Party () until June 2020, is a left-wing nationalist political party in South Korea. The party was formed by the merger of the New People's Party and People's United Party on 15 October 2017.

...

* Sinchon Museum of American War Atrocities

The Sinchon Museum of American War Atrocities (Korean: 신천박물관) is a museum dedicated to the Sinchon Massacre, a massacre of North Korean civilians during the Korean War which the North Korean government claims was carried out by South K ...

* United States–North Korea relations

References

External links

*How the World Sees America

''How the World Sees America'' is a video blog run by global correspondent Amar C. Bakshi and sponsored by ''The Washington Post'' and Newsweek Magazine. It features daily articles, which include text and short video clips, about citizens around t ...

videoblogSouth Korea

주한미군범죄근절운동본부

Kenneth L. Markle: Sadistic Murderer or Scapegoat?

(자주민보) – Murdered picture by a US Soldier {{Asia in topic, Anti-American sentiment in

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

Korea–United States relations

Left-wing nationalism in South Korea

Military history of Korea

Murder in South Korea

North Korea–United States relations

Politics of South Korea

South Korea–United States relations

ko:반미주의#대한민국

ko:윤금이 피살 사건

ja:尹今伊殺害事件