Anne Hutchinson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Anne Hutchinson (née Marbury; July 1591 – August 1643) was a

Anne Hutchinson was born Anne Marbury to parents

Anne Hutchinson was born Anne Marbury to parents

Another strong influence on Hutchinson was closer to her home in the nearby town of

Another strong influence on Hutchinson was closer to her home in the nearby town of

The Reverend Zechariah Symmes had sailed to New England on the same ship as the Hutchinsons. In September 1634, he told another minister that he doubted Anne Hutchinson's orthodoxy, based on questions that she asked him following his shipboard sermons. This issue delayed Hutchinson's membership to the Boston church by a week, until a pastoral examination determined that she was sufficiently orthodox to join the church.

In 1635, a difficult situation occurred when senior pastor John Wilson returned from a lengthy trip to England where he had been settling his affairs. Hutchinson was exposed to his teaching for the first time, and she saw a big difference between her own doctrines and his. She found his emphasis on morality and his doctrine of "evidencing justification by sanctification" to be disagreeable. She told her followers that Wilson lacked "the seal of the Spirit." Wilson's theological views were in accord with all of the other ministers in the colony except for Cotton, who stressed "the inevitability of God's will" ("free grace") as opposed to preparation (works). Hutchinson and her allies had become accustomed to Cotton's doctrines, and they began disrupting Wilson's sermons, even finding excuses to leave when Wilson got up to preach or pray.

Thomas Shepard, the minister of Newtown (which later became

The Reverend Zechariah Symmes had sailed to New England on the same ship as the Hutchinsons. In September 1634, he told another minister that he doubted Anne Hutchinson's orthodoxy, based on questions that she asked him following his shipboard sermons. This issue delayed Hutchinson's membership to the Boston church by a week, until a pastoral examination determined that she was sufficiently orthodox to join the church.

In 1635, a difficult situation occurred when senior pastor John Wilson returned from a lengthy trip to England where he had been settling his affairs. Hutchinson was exposed to his teaching for the first time, and she saw a big difference between her own doctrines and his. She found his emphasis on morality and his doctrine of "evidencing justification by sanctification" to be disagreeable. She told her followers that Wilson lacked "the seal of the Spirit." Wilson's theological views were in accord with all of the other ministers in the colony except for Cotton, who stressed "the inevitability of God's will" ("free grace") as opposed to preparation (works). Hutchinson and her allies had become accustomed to Cotton's doctrines, and they began disrupting Wilson's sermons, even finding excuses to leave when Wilson got up to preach or pray.

Thomas Shepard, the minister of Newtown (which later became

By late 1636, as the controversy deepened, Hutchinson and her supporters were accused of two heresies in the Puritan church:

By late 1636, as the controversy deepened, Hutchinson and her supporters were accused of two heresies in the Puritan church:

The remainder of the trial was spent on this last charge. The prosecution intended to demonstrate that Hutchinson had made disparaging remarks about the colony's ministers, and to use the October meeting as their evidence. Six ministers had presented to the court their written versions of the October conference, and Hutchinson agreed with the substance of their statements. Her defence was that she had spoken reluctantly and in private, that she "must either speak false or true in my answers" in the ministerial context of the meeting. In those private meetings, she had cited Proverbs 29:25, "The fear of man bringeth a snare: but whoso putteth his trust in the Lord shall be safe." The court was not interested in her distinction between public and private statements.

At the end of the first day of the trial, Winthrop recorded, "Mrs. Hutchinson, the court you see hath labored to bring you to acknowledge the error of your way that so you might be reduced. The time now grows late. We shall therefore give you a little more time to consider of it and therefore desire that you attend the court again in the morning." The first day had gone fairly well for Hutchinson, who had held her own in a battle of wits with the magistrates. Biographer Eve LaPlante suggests, "Her success before the court may have astonished her judges, but it was no surprise to her. She was confident of herself and her intellectual tools, largely because of the intimacy she felt with God."

The remainder of the trial was spent on this last charge. The prosecution intended to demonstrate that Hutchinson had made disparaging remarks about the colony's ministers, and to use the October meeting as their evidence. Six ministers had presented to the court their written versions of the October conference, and Hutchinson agreed with the substance of their statements. Her defence was that she had spoken reluctantly and in private, that she "must either speak false or true in my answers" in the ministerial context of the meeting. In those private meetings, she had cited Proverbs 29:25, "The fear of man bringeth a snare: but whoso putteth his trust in the Lord shall be safe." The court was not interested in her distinction between public and private statements.

At the end of the first day of the trial, Winthrop recorded, "Mrs. Hutchinson, the court you see hath labored to bring you to acknowledge the error of your way that so you might be reduced. The time now grows late. We shall therefore give you a little more time to consider of it and therefore desire that you attend the court again in the morning." The first day had gone fairly well for Hutchinson, who had held her own in a battle of wits with the magistrates. Biographer Eve LaPlante suggests, "Her success before the court may have astonished her judges, but it was no surprise to her. She was confident of herself and her intellectual tools, largely because of the intimacy she felt with God."

The ministers intended to defend their orthodox doctrine and to examine Hutchinson's theological errors. Ruling elder Thomas Leverett was charged with managing the examination. He called Hutchinson and read the numerous errors with which she had been charged, and a nine-hour interrogation followed in which the ministers delved into some weighty points of theology. At the end of the session, only four of the many errors were covered, and Cotton was put in the uncomfortable position of delivering the admonition to his admirer. He said, "I would speake it to Gods Glory

The ministers intended to defend their orthodox doctrine and to examine Hutchinson's theological errors. Ruling elder Thomas Leverett was charged with managing the examination. He called Hutchinson and read the numerous errors with which she had been charged, and a nine-hour interrogation followed in which the ministers delved into some weighty points of theology. At the end of the session, only four of the many errors were covered, and Cotton was put in the uncomfortable position of delivering the admonition to his admirer. He said, "I would speake it to Gods Glory

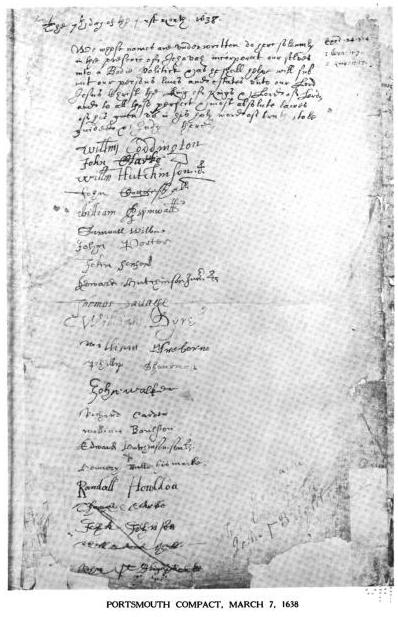

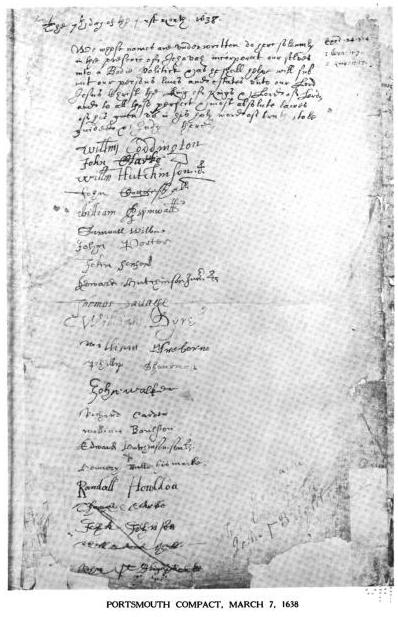

During Hutchinson's imprisonment, several of her supporters prepared to leave the colony and settle elsewhere. One such group of men, including her husband Will, met on 7 March 1638 at the home of wealthy Boston merchant William Coddington. Ultimately, 23 men signed what is known as the

During Hutchinson's imprisonment, several of her supporters prepared to leave the colony and settle elsewhere. One such group of men, including her husband Will, met on 7 March 1638 at the home of wealthy Boston merchant William Coddington. Ultimately, 23 men signed what is known as the

Not long after the settlement of Aquidneck Island, the Massachusetts Bay Colony made some serious threats to annex the island and the entire Narragansett Bay area, causing Hutchinson and other settlers much anxiety. This compelled her to move totally out of the reach of the Bay colony and its sister colonies in

Not long after the settlement of Aquidneck Island, the Massachusetts Bay Colony made some serious threats to annex the island and the entire Narragansett Bay area, causing Hutchinson and other settlers much anxiety. This compelled her to move totally out of the reach of the Bay colony and its sister colonies in

The warriors then dragged the bodies into the house, along with the cattle, and burned the house to the ground. During the attack, Hutchinson's nine-year-old daughter Susanna was out picking blueberries; she was found, according to legend, hidden in the crevice of Split Rock nearby. She is believed to have had red hair, which was unusual to the Indians, and perhaps because of this curiosity her life was spared. She was taken captive, was named "Autumn Leaf" by one account, and lived with the Indians for two to six years (accounts vary) until ransomed back to her family members, most of whom were living in Boston.

The exact date of the Hutchinson massacre is not known. The first definitive record of the occurrence was in John Winthrop's journal, where it was the first entry made for the month of September, though not dated. It took days or even weeks for Winthrop to receive the news, so the event almost certainly occurred in August 1643, and this is the date found in most sources.

The reaction in Massachusetts to Hutchinson's death was harsh. The Reverend

The warriors then dragged the bodies into the house, along with the cattle, and burned the house to the ground. During the attack, Hutchinson's nine-year-old daughter Susanna was out picking blueberries; she was found, according to legend, hidden in the crevice of Split Rock nearby. She is believed to have had red hair, which was unusual to the Indians, and perhaps because of this curiosity her life was spared. She was taken captive, was named "Autumn Leaf" by one account, and lived with the Indians for two to six years (accounts vary) until ransomed back to her family members, most of whom were living in Boston.

The exact date of the Hutchinson massacre is not known. The first definitive record of the occurrence was in John Winthrop's journal, where it was the first entry made for the month of September, though not dated. It took days or even weeks for Winthrop to receive the news, so the event almost certainly occurred in August 1643, and this is the date found in most sources.

The reaction in Massachusetts to Hutchinson's death was harsh. The Reverend

The memorial is featured on the

The memorial is featured on the

In southern New York, Hutchinson's most prominent namesakes are the

In southern New York, Hutchinson's most prominent namesakes are the

The oldest child

The oldest child

A number of Anne Hutchinson's descendants have reached great prominence. Among them are United States Presidents

A number of Anne Hutchinson's descendants have reached great prominence. Among them are United States Presidents

online free

* Bremer, Francis J. ''Anne Hutchinson, Troubler of the Puritan Zion'' (1981) * * The article includes an annotated transcription of Hutchinson's "Immediate Revelation." * * Hall, Timothy D. ''Anne Hutchinson: Puritan Prophet'' (Library of American Biography 2009). * * Stille, Darlene R. ''Anne Hutchinson: Puritan protester'' (2006) for middle and secondary schools

online

* *

Background on the Anne Hutchinson statue; while this source gives a dedication year of 1915, most other sources give the year as 1922.

Hutchinson massacre

Sermon about Hutchinson

The perspective of a modern female minister

Hutchinson marker in Quincy

Hutchinson's connection with Harvard College * Michals, Debra.

"Anne Hutchinson"

National Women's History Museum. 2015. {{DEFAULTSORT:Hutchinson, Anne 1591 births 1643 deaths 17th-century American people 16th-century English women 17th-century American women 17th-century English women 17th-century English people Women in 17th-century warfare Anglican saints American Calvinist and Reformed theologians Colonial American women American midwives American political philosophy American Puritans History of New York City History of the Bronx Kingdom of England emigrants to Massachusetts Bay Colony People of colonial Massachusetts New England Puritanism People of the Province of New York People excommunicated by Christian churches People from Alford, Lincolnshire People from colonial Boston People from the Bronx People of New Netherland People of colonial Rhode Island Colonial American and Indian wars War-related deaths People murdered in New York City Female murder victims Kieft's War Early colonists in America Murder in the Thirteen Colonies Murder in 1643

Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

spiritual advisor, religious reformer, and an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy

The Antinomian Controversy, also known as the Free Grace Controversy, was a religious and political conflict in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. It pitted most of the colony's ministers and magistrates against some adherents of ...

which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

from 1636 to 1638. Her strong religious convictions were at odds with the established Puritan clergy in the Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

area and her popularity and charisma helped create a theological schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

that threatened the Puritan religious community in New England. She was eventually tried and convicted, then banished from the colony with many of her supporters.

Hutchinson was born in Alford, Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

, England, the daughter of Francis Marbury

Francis Marbury (sometimes spelled Merbury) (1555–1611) was a Cambridge-educated English cleric, schoolmaster and playwright. He is best known for being the father of Anne Hutchinson, considered the most famous English woman in colonial Ame ...

, an Anglican cleric and school teacher who gave her a far better education than most other girls received. She lived in London as a young adult, and there married a friend from home, William Hutchinson. The couple moved back to Alford where they began following preacher John Cotton in the nearby port of Boston, Lincolnshire

Boston is a market town and inland port in the borough of the same name in the county of Lincolnshire, England. Boston is north of London, north-east of Peterborough, east of Nottingham, south-east of Lincoln, south-southeast of Hull ...

. Cotton was compelled to emigrate in 1633, and the Hutchinsons followed a year later with their 11 children and soon became well established in the growing settlement of Boston in New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

. Hutchinson was a midwife

A midwife is a health professional who cares for mothers and newborns around childbirth, a specialization known as midwifery.

The education and training for a midwife concentrates extensively on the care of women throughout their lifespan; co ...

and helpful to those needing her assistance, as well as forthcoming with her personal religious understandings. Soon she was hosting women at her house weekly, providing commentary on recent sermons. These meetings became so popular that she began offering meetings for men as well, including the young governor of the colony, Henry Vane.

Hutchison began to accuse the local ministers (except for Cotton and her husband's brother-in-law, John Wheelwright

John Wheelwright (c. 1592–1679) was a Puritan clergyman in England and America, noted for being banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the Antinomian Controversy, and for subsequently establishing the town of Exeter, New Hamp ...

) of preaching a covenant of works

Covenant theology (also known as covenantalism, federal theology, or federalism) is a conceptual overview and interpretive framework for understanding the overall structure of the Bible. It uses the theological concept of a covenant as an orga ...

rather than a covenant of grace

Covenant theology (also known as covenantalism, federal theology, or federalism) is a conceptual overview and interpretive framework for understanding the overall structure of the Bible. It uses the theological concept of a covenant as an organ ...

, and many ministers began to complain about her increasingly blatant accusations, as well as certain unorthodox theological teachings. The situation eventually erupted into what is commonly called the Antinomian Controversy

The Antinomian Controversy, also known as the Free Grace Controversy, was a religious and political conflict in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. It pitted most of the colony's ministers and magistrates against some adherents of ...

, culminating in her 1637 trial, conviction, and banishment from the colony. This was followed by a March 1638 church trial in which she was put out of her congregation.

Hutchinson and many of her supporters established the settlement of Portsmouth, Rhode Island

Portsmouth is a town in Newport County, Rhode Island, United States. The population was 17,871 at the 2020 U.S. census. Portsmouth is the second-oldest municipality in Rhode Island, after Providence; it was one of the four colonies which merged ...

with encouragement from Providence Plantations

Providence Plantations was the first permanent European American settlement in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. It was established by a group of colonists led by Roger Williams and Dr. John Clarke who left Massachusetts Bay ...

founder Roger Williams

Roger Williams (21 September 1603between 27 January and 15 March 1683) was an English-born New England Puritan minister, theologian, and author who founded Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation ...

in what became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations was one of the original Thirteen Colonies established on the east coast of America, bordering the Atlantic Ocean. It was founded by Roger Williams. It was an English colony from 1636 until ...

. After her husband's death a few years later, threats of Massachusetts annexing Rhode Island compelled Hutchinson to move totally outside the reach of Boston into the lands of the Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

. Five of her older surviving children remained in New England or in England, while she settled with her younger children near an ancient landmark, Split Rock, in what later became The Bronx

The Bronx () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the state of New York. It is south of Westchester County; north and east of the New York City borough of Manhattan, across the Harlem River; and north of the New Y ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. Tensions were high at the time with the Siwanoy

The Siwanoy () were an Indigenous American band of Wappinger people, who lived in Long Island Sound along the coasts of what are now The Bronx, Westchester County, New York, and Fairfield County, Connecticut. They were one of the western bands of ...

Indian tribe. In August 1643, Hutchinson, six of her children, and other household members were killed by Siwanoys during Kieft's War

Kieft's War (1643–1645), also known as the Wappinger War, was a conflict between the colonial province of New Netherland and the Wappinger and Lenape Indians in what is now New York and New Jersey. It is named for Director-General of New Nethe ...

. The only survivor was her nine-year-old daughter Susanna, who was taken captive.

Hutchinson is a key figure in the history of religious freedom in England's American colonies and the history of women in ministry, challenging the authority of the ministers. She is honored by Massachusetts with a State House monument calling her a "courageous exponent of civil liberty and religious toleration". She has been called "the most famous—or infamous—English woman in colonial American history".

Life in England

Childhood

Anne Hutchinson was born Anne Marbury to parents

Anne Hutchinson was born Anne Marbury to parents Francis Marbury

Francis Marbury (sometimes spelled Merbury) (1555–1611) was a Cambridge-educated English cleric, schoolmaster and playwright. He is best known for being the father of Anne Hutchinson, considered the most famous English woman in colonial Ame ...

and Bridget Dryden in Alford, Lincolnshire, England, and baptised there on 20 July 1591. Her father was an Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

cleric

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

with strong Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

leanings, who felt strongly that a clergy should be well educated and clashed with his superiors on this issue. Marbury's repeated challenges to the Anglican authorities led to his censure and imprisonment several years before Anne was born. In 1578, he was given a public trial, of which he made a transcript from memory during a period of house arrest. He later used this transcript to educate and amuse his children, he being the hero and the Bishop of London being portrayed as a buffoon.

For his conviction of heresy, Marbury spent two years in Marshalsea

The Marshalsea (1373–1842) was a notorious prison in Southwark, just south of the River Thames. Although it housed a variety of prisoners, including men accused of crimes at sea and political figures charged with sedition, it became known, in ...

Prison on the south side of the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

across from London. In 1580, at the age of 25, he was released and was considered sufficiently reformed to preach and teach. He moved to the remote market town of Alford in Lincolnshire, about north of London. Hutchinson's father was soon appointed curate

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' (''cura'') ''of souls'' of a parish. In this sense, "curate" means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy w ...

(assistant priest) of St Wilfrid's Church, Alford

St Wilfrid's, Alford is the Church of England parish church in Alford, Lincolnshire, England. It is a Grade I listed building.

Background

The church is named after St Wilfrid and is the second church to be built on the site, the earlier bein ...

, and in 1585 he also became the schoolmaster at the Alford Free Grammar School

Free Grammar Schools were schools which usually operated under the jurisdiction of the church in pre-modern England. Education had long been associated with religious institutions since a Cathedral grammar school was established at Canterbury unde ...

, one of many such public schools, free to the poor and begun by Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

. About this time, Marbury married his first wife, Elizabeth Moore, who bore three children, then died. Within a year of his first wife's death, Marbury married Bridget Dryden, about 10 years younger than he and from a prominent Northampton

Northampton () is a market town and civil parish in the East Midlands of England, on the River Nene, north-west of London and south-east of Birmingham. The county town of Northamptonshire, Northampton is one of the largest towns in England; ...

family. Her brother Erasmus was the grandfather of John Dryden

''

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the per ...

, the playwright and Poet Laureate

A poet laureate (plural: poets laureate) is a poet officially appointed by a government or conferring institution, typically expected to compose poems for special events and occasions. Albertino Mussato of Padua and Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch) ...

. Anne was the third of 15 children born to this marriage, 12 of whom survived early childhood. The Marburys lived in Alford for the first 15 years of Anne's life, and she received a better education than most girls of her time, with her father's strong commitment to learning, and she also became intimately familiar with scripture and Christian tenets. Education at that time was offered almost exclusively to boys and men. One possible reason why Marbury taught his daughters may have been that six of his first seven children were girls. Another reason may have been that the ruling class in Elizabethan England

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personific ...

began realising that girls could be schooled, looking to the example of the queen, who spoke six foreign languages.

In 1605 when Hutchinson was 15, her family moved from Alford to the heart of London, where her father was given the position of vicar of St Martin Vintry

St Martin Vintry was a parish church in the Vintry ward of the City of London, England. It was destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666 and never rebuilt.

History

The church stood at what is now the junction of Queen Street and Upper Thames ...

. Here his expression of Puritan views was tolerated, though somewhat muffled, because of a shortage of clergy. Marbury took on additional work in 1608, preaching in the parish of St Pancras, Soper Lane, several miles northwest of the city, travelling there by horseback twice a week. In 1610, he replaced that position with one much closer to home and became rector of St Margaret, New Fish Street, a short walk from St Martin Vintry. He was at a high point in his career, but he died suddenly at the age of 55 in February 1611, when Anne was 19 years old.

Adulthood: following John Cotton

The year after her father's death, Anne Marbury, aged 21, married William Hutchinson, a familiar acquaintance from Alford who was a fabric merchant then working in London. The couple was married atSt Mary Woolnoth

St Mary Woolnoth is an Anglican church in the City of London, located on the corner of Lombard Street and King William Street near Bank junction. The present building is one of the Queen Anne Churches, designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor. The paris ...

Church in London on 9 August 1612, shortly after which they moved back to their hometown of Alford.

Soon they heard about an engaging minister named John Cotton who preached at St Botolph's Church in the large port of Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, about from Alford. Cotton was installed as minister at Boston the year that the Hutchinsons were married, after having been a tutor at Emmanuel College in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

. He was 27 years old, yet he had gained a reputation as one of the leading Puritans in England. Once the Hutchinsons heard Cotton preach, the couple made the trip to Boston as often as possible, enduring the ride by horseback when the weather and circumstances allowed. Cotton's spiritual message was different from that of his fellow Puritans, as he placed less emphasis on one's behaviour to attain God's salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

and more emphasis on the moment of religious conversion "in which mortal man was infused with a divine grace." Anne Hutchinson was attracted to Cotton's theology of "absolute grace", which caused her to question the value of "works" and to view the Holy Spirit

In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is the divine force, quality, and influence of God over the Universe or over his creatures. In Nicene Christianity, the Holy Spirit or Holy Ghost is the third person of the Trinity. In Islam, the Holy Spirit acts as ...

as "indwelling in the elect saint". This allowed her to identify as a "mystic participant in the transcendent power of the Almighty"; such a theology was empowering to women, according to Eve LaPlante, whose status was otherwise determined by their husbands or fathers.

Another strong influence on Hutchinson was closer to her home in the nearby town of

Another strong influence on Hutchinson was closer to her home in the nearby town of Bilsby

Bilsby is a village and civil parish in the East Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England. It lies on the main A1111 road between Alford and Sutton-on-Sea, east of Alford. Thurlby and Asserby are hamlets within Bilsby parish. The censuses s ...

. Her brother-in-law, the young minister John Wheelwright

John Wheelwright (c. 1592–1679) was a Puritan clergyman in England and America, noted for being banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the Antinomian Controversy, and for subsequently establishing the town of Exeter, New Hamp ...

, preached a message like that of Cotton. As reformers, both Cotton and Wheelwright encouraged a sense of religious rebirth among their parishioners, but their weekly sermons did not satisfy the yearnings of some Puritan worshippers. This led to the rise of conventicle

A conventicle originally signified no more than an assembly, and was frequently used by ancient writers for a church. At a semantic level ''conventicle'' is only a good Latinized synonym of the Greek word church, and points to Jesus' promise in M ...

s, which were gatherings of "those who had found grace" to listen to sermon repetitions, discuss and debate scripture, and pray. These gatherings were particularly important to women because they allowed women to assume roles of religious leadership that were otherwise denied them in a male-dominated church hierarchy. Hutchinson was inspired by Cotton and by other women who ran conventicles, and she began holding meetings in her own home, where she reviewed recent sermons with her listeners, and provided her own explanations of the message.

The Puritans wanted to abolish the ceremony of the Church of England and govern their churches based on a consensus of the parishioners. They preferred to eliminate bishops appointed by the monarchs, choose their own church elders (or governors), and provide for a lay leader and two ministers—one a teacher in charge of doctrine, and the other a pastor in charge of people's souls. By 1633, Cotton's inclination toward such Puritan practices had attracted the attention of Archbishop William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Charles I's religious reforms, he was arrested by Parliament in 1640 ...

, who was on a campaign to suppress any preaching and practices that did not conform to the practices of the established Anglican Church

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

. In that year, Cotton was removed from his ministry, and he went into hiding. Threatened with imprisonment, he made a hasty departure for New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

aboard the ship ''Griffin'', taking his pregnant wife with him. During the voyage to the colonies, she gave birth to their child, whom they named Seaborn.

When Cotton left England, Anne Hutchinson described it as a "great trouble unto her," and said that she "could not be at rest" until she followed her minister to New England. Hutchinson believed that the Spirit

Spirit or spirits may refer to:

Liquor and other volatile liquids

* Spirits, a.k.a. liquor, distilled alcoholic drinks

* Spirit or tincture, an extract of plant or animal material dissolved in ethanol

* Volatile (especially flammable) liquids, ...

instructed her to follow Cotton to America, "impressed by the evidence of divine providence". She was well into her 14th pregnancy, however, so she did not travel until after the baby was born. With the intention of soon going to New England, the Hutchinsons allowed their oldest son Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

to sail with Cotton before the remainder of the family made the voyage. In 1634, 43-year-old Anne Hutchinson set sail from England with her 48-year-old husband William and their other ten surviving children, aged about eight months to 19 years. They sailed aboard the ''Griffin'', the same ship that had carried Cotton and their oldest son a year earlier.

Boston

William Hutchinson was successful in his mercantile business and brought a considerable estate with him to New England, arriving in Boston in the late summer of 1634. The Hutchinson family purchased a half-acre lot on the Shawmut Peninsula, now downtown Boston. Here they had a house built, one of the largest on the peninsula, with a timber frame and at least two stories. (The house stood until October 1711, when it was consumed in thegreat fire of Boston

Great may refer to: Descriptions or measurements

* Great, a relative measurement in physical space, see Size

* Greatness, being divine, majestic, superior, majestic, or transcendent

People

* List of people known as "the Great"

*Artel Great (born ...

, after which the Old Corner Bookstore

The Old Corner Bookstore is a historic commercial building located at 283 Washington Street at the corner of School Street in the historic core of Boston, Massachusetts. It was built in 1718 as a residence and apothecary shop, and first became ...

was built on the site.) The Hutchinsons soon were granted Taylor's Island in the Boston harbour, where they grazed their sheep, and they also acquired 600 acres of land at Mount Wollaston, south of Boston in the area that later became Quincy. Once established, William Hutchinson continued to prosper in the cloth trade and made land purchases and investments. He became a town selectman and deputy to the General Court. Anne Hutchinson likewise fit into her new home with ease, devoting many hours to those who were ill or in need. She became an active midwife

A midwife is a health professional who cares for mothers and newborns around childbirth, a specialization known as midwifery.

The education and training for a midwife concentrates extensively on the care of women throughout their lifespan; co ...

, and while tending to women in childbirth, she provided them with spiritual advice. Magistrate John Winthrop

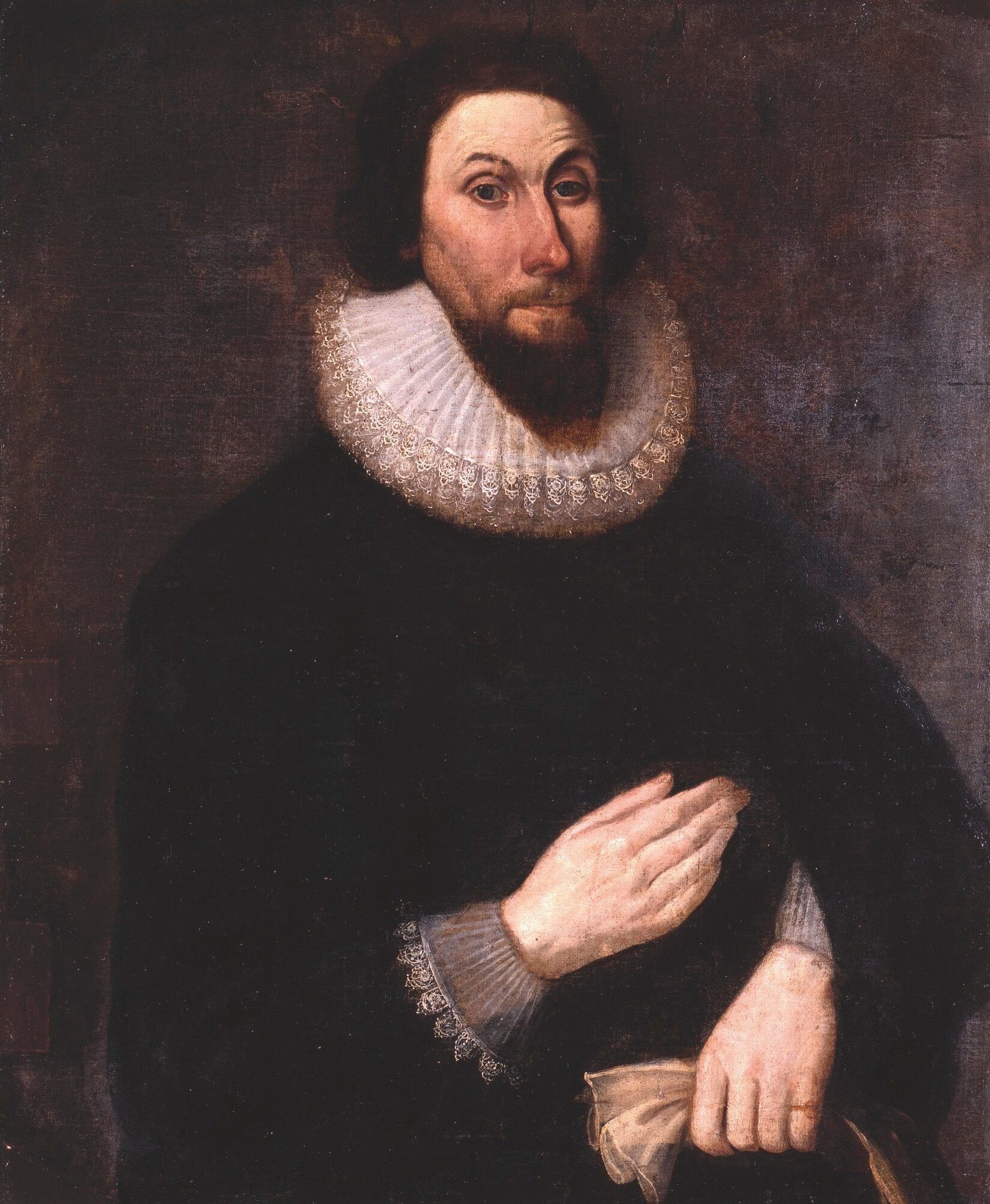

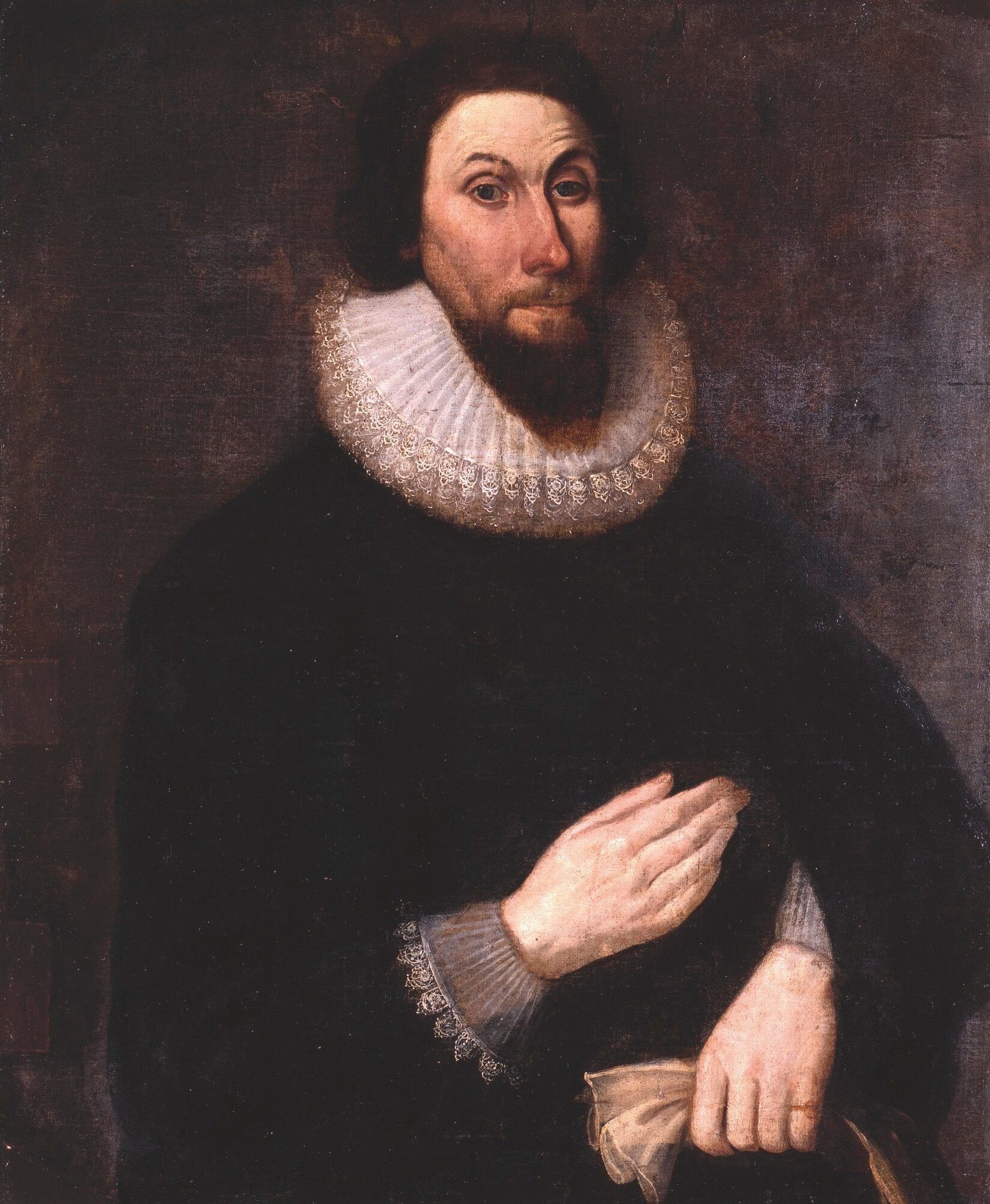

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/88 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led t ...

noted that "her ordinary talke was about the things of the Kingdome of God," and "her usuall conversation was in the way of righteousness and kindnesse."

Boston church

The Hutchinsons became members of theFirst Church in Boston

First Church in Boston is a Unitarian Universalist Church (originally Congregationalist) founded in 1630 by John Winthrop's original Puritan settlement in Boston, Massachusetts. The current building, located on 66 Marlborough Street in the Back ...

, the most important church in the colony. With its location and harbour, Boston was New England's centre of commerce, and its church was characterised by Winthrop as "the most publick, where Seamen and all Strangers came". The church membership had grown from 80 to 120 during Cotton's first four months there. In his journal, Winthrop stated that "more were converted & added to that Churche, than to all the other Churches in the Baye." The historian Michael Winship noted in 2005 that the church seemed to approach the Puritan ideal of a Christian community. Early Massachusetts historian William Hubbard found the church to be "in so flourishing a condition as were scarce any where else to be paralleled." Winship considers it a twist of fate that the colony's most important church also had the most unconventional minister in John Cotton. The more extreme religious views of Hutchinson and Henry Vane, the colony's young governor, did not much stand out because of Cotton's divergence from the theology of his fellow ministers.

Home Bible study group

Hutchinson's visits to women in childbirth led to discussions along the lines of the conventicles in England. She soon began hosting weekly meetings at her home for women who wanted to discuss Cotton's sermons and hear her explanations and elaborations. Her meetings for women became so popular that she had to organise meetings for men, as well, and she was hosting 60 or more people per week. These gatherings brought women, as well as their husbands, "to enquire more seriously after the Lord Jesus Christ." As the meetings continued, Hutchinson began offering her own religious views, stressing that only "an intuition of the Spirit" would lead to one'selection

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

by God, and not good works. Her theological interpretations began diverging from the more legalistic views found among the colony's ministers, and the attendance increased at her meetings and soon included Governor Vane. Her ideas that one's outward behaviour was not necessarily tied to the state of one's soul became attractive to those who might have been more attached to their professions than to their religious state, such as merchants and craftsmen. The colony's ministers became more aware of Hutchinson's meetings, and they contended that such "unauthorised" religious gatherings might confuse the faithful. Hutchinson responded to this with a verse from Titus

Titus Caesar Vespasianus ( ; 30 December 39 – 13 September 81 AD) was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death.

Before becoming emperor, Titus gained renown as a mili ...

, saying that "the elder women should instruct the younger."

Antinomian Controversy

Tensions build

Hutchinson's gatherings were seen as unorthodox by some of the colony's ministers, and differing religious opinions within the colony eventually became public debates. The resulting religious tension erupted into what has traditionally been called the Antinomian Controversy, but has more recently been labelled the Free Grace Controversy. The Reverend Zechariah Symmes had sailed to New England on the same ship as the Hutchinsons. In September 1634, he told another minister that he doubted Anne Hutchinson's orthodoxy, based on questions that she asked him following his shipboard sermons. This issue delayed Hutchinson's membership to the Boston church by a week, until a pastoral examination determined that she was sufficiently orthodox to join the church.

In 1635, a difficult situation occurred when senior pastor John Wilson returned from a lengthy trip to England where he had been settling his affairs. Hutchinson was exposed to his teaching for the first time, and she saw a big difference between her own doctrines and his. She found his emphasis on morality and his doctrine of "evidencing justification by sanctification" to be disagreeable. She told her followers that Wilson lacked "the seal of the Spirit." Wilson's theological views were in accord with all of the other ministers in the colony except for Cotton, who stressed "the inevitability of God's will" ("free grace") as opposed to preparation (works). Hutchinson and her allies had become accustomed to Cotton's doctrines, and they began disrupting Wilson's sermons, even finding excuses to leave when Wilson got up to preach or pray.

Thomas Shepard, the minister of Newtown (which later became

The Reverend Zechariah Symmes had sailed to New England on the same ship as the Hutchinsons. In September 1634, he told another minister that he doubted Anne Hutchinson's orthodoxy, based on questions that she asked him following his shipboard sermons. This issue delayed Hutchinson's membership to the Boston church by a week, until a pastoral examination determined that she was sufficiently orthodox to join the church.

In 1635, a difficult situation occurred when senior pastor John Wilson returned from a lengthy trip to England where he had been settling his affairs. Hutchinson was exposed to his teaching for the first time, and she saw a big difference between her own doctrines and his. She found his emphasis on morality and his doctrine of "evidencing justification by sanctification" to be disagreeable. She told her followers that Wilson lacked "the seal of the Spirit." Wilson's theological views were in accord with all of the other ministers in the colony except for Cotton, who stressed "the inevitability of God's will" ("free grace") as opposed to preparation (works). Hutchinson and her allies had become accustomed to Cotton's doctrines, and they began disrupting Wilson's sermons, even finding excuses to leave when Wilson got up to preach or pray.

Thomas Shepard, the minister of Newtown (which later became Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

), began writing letters to Cotton as early as the spring of 1636. He expressed concern about Cotton's preaching and about some of the unorthodox opinions found among his Boston parishioners. Shepard went even further when he began criticising the Boston opinions to his Newtown congregation during his sermons. In May 1636, the Bostonians received a new ally when the Reverend John Wheelwright

John Wheelwright (c. 1592–1679) was a Puritan clergyman in England and America, noted for being banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the Antinomian Controversy, and for subsequently establishing the town of Exeter, New Hamp ...

arrived from England and aligned himself with Cotton, Hutchinson, and other "free grace" advocates. Wheelwright had been a neighbour of the Hutchinsons in Lincolnshire, and his wife was a sister of Hutchinson's husband. Another boost for the free grace advocates came during the same month, when the young aristocrat Henry Vane was elected as the governor of the colony. Vane was a strong supporter of Hutchinson, yet he also had his own ideas about theology that were considered not only unorthodox, but radical by some.

Hutchinson and the other free grace advocates continued to question the orthodox ministers in the colony. Wheelwright began preaching at Mount Wollaston

Quincy ( ) is a coastal U.S. city in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. It is the largest city in the county and a part of Metropolitan Boston as one of Boston's immediate southern suburbs. Its population in 2020 was 101,636, making ...

, about ten miles south of the Boston meetinghouse, and his sermons began to answer Shepard's criticisms with his own criticism of the covenant of works. This mounting "pulpit aggression" continued throughout the summer, along with the lack of respect shown Boston's Reverend Wilson. Wilson endured these religious differences for several months before deciding that the affronts and errors were serious enough to require a response. He is the one who likely alerted magistrate John Winthrop, one of his parishioners, to take notice. On or shortly after 21 October 1636, Winthrop gave the first public warning of the problem that consumed him and the leadership of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

for much of the next two years. In his journal he wrote, "One Mrs. Hutchinson, a member of the church at Boston, a woman of a ready wit and a bold spirit, brought over with her two dangerous errors: 1. That the person of the Holy Ghost dwells in a justified person. 2. That no sanctification can help to evidence to us our justification." He went on to elaborate these two points, and the Antinomian Controversy began with this journal entry.

Ministerial confrontation

On 25 October 1636, seven ministers gathered at the home of Cotton to confront the developing discord; they held a "private conference" which included Hutchinson and other lay leaders from the Boston church. Some agreement was reached, and Cotton "gave satisfaction to them he other ministers so as he agreed with them all in the point of sanctification, and so did Mr. Wheelwright; so as they all did hold, that sanctification did help to evidence justification." Another issue was that some of the ministers had heard that Hutchinson criticised them during her conventicles for preaching a covenant of works and said they were not able ministers of theNew Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

. Hutchinson responded to this only when prompted, and only to one or two ministers at a time. She believed that her response, which was largely coaxed from her, was private and confidential. A year later, her words were used against her in a trial that resulted in her banishment from the colony.

By late 1636, as the controversy deepened, Hutchinson and her supporters were accused of two heresies in the Puritan church:

By late 1636, as the controversy deepened, Hutchinson and her supporters were accused of two heresies in the Puritan church: antinomianism

Antinomianism (Ancient Greek: ἀντί 'anti''"against" and νόμος 'nomos''"law") is any view which rejects laws or legalism and argues against moral, religious or social norms (Latin: mores), or is at least considered to do so. The term ha ...

and familism

Familialism or familism is an ideology that puts priority to family. The term ''familialism'' has been specifically used for advocating a welfare system wherein it is presumed that families will take responsibility for the care of their members ...

. The word "antinomianism" literally means "against or opposed to the law"; in a theological context, it means "the moral law is not binding upon Christians, who are under the law of grace." According to this view, if one was under the law of grace, then moral law did not apply, allowing one to engage in immoral acts. Familism was named for a 16th-century sect called the Family of Love, and it involved one's perfect union with God under the Holy Spirit, coupled with freedom both from sin and from the responsibility for it. Hutchinson and her supporters were sometimes accused of engaging in immoral behaviour or "free love" in order to discredit them, but such acts were antithetical to their doctrine. Hutchinson, Wheelwright, and Vane all took leading roles as antagonists of the orthodox party, but theologically, it was Cotton's differences of opinion with the colony's other ministers that was at the centre of the controversy.

By winter, the theological schism had become great enough that the General Court called for a day of fasting to help ease the colony's difficulties. During the appointed fast-day on Thursday, 19 January 1637, Wheelwright preached at the Boston church in the afternoon. To the Puritan clergy, his sermon was "censurable and incited mischief", but the free grace advocates were encouraged, and they became more vociferous in their opposition to the "legal" ministers. Governor Vane began challenging the doctrines of the colony's divines, and supporters of Hutchinson refused to serve during the Pequot War

The Pequot War was an armed conflict that took place between 1636 and 1638 in New England between the Pequot tribe and an alliance of the colonists from the Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Saybrook colonies and their allies from the Narragans ...

of 1637 because Wilson was the chaplain of the expedition. Ministers worried that the bold stand of Hutchinson and her supporters began to threaten the "Puritan's holy experiment." Had they succeeded, historian Dunn believes that they would have profoundly changed the thrust of Massachusetts history.

Events of 1637

By March, the political tide began to turn against the free grace advocates. Wheelwright was tried for contempt and sedition that month for his fast-day sermon and was convicted in a close vote, but not yet sentenced. During the election of May 1637, Henry Vane was replaced as governor by John Winthrop; in addition, all the other Boston magistrates who supported Hutchinson and Wheelwright were voted out of office. By the summer of 1637, Vane sailed back to England, never to return. With his departure, the time was ripe for the orthodox party to deal with the remainder of their rivals. The autumn court of 1637 convened on 2 November and sentenced Wheelwright to banishment, ordering him to leave the colony within 14 days. Several of the other supporters of Hutchinson and Wheelwright were tried and given varied sentences. Following these preliminaries, it was Anne Hutchinson's turn to be tried.Civil trial: day 1

Hutchinson was brought to trial on 7 November 1637, with Wheelwright banished and other court business settled. Governor John Winthrop presided over the trial, in which Hutchinson was charged with "traducing landeringthe ministers". Winthrop also presented other charges against her, including the allegation that she "troubled the peace of the commonwealth and churches" by promoting and divulging opinions that had divided the community, and continuing to hold meetings at her home despite a recentsynod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word ''wikt:synod, synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin ...

that had condemned them.

The court, however, found it difficult to charge Hutchinson because she had never spoken her opinions in public, unlike Wheelwright and the other men who had been tried, nor had she ever signed any statements about them. Winthrop's first two lines of prosecution were to portray her as a co-conspirator of others who had openly caused trouble in the colony, and then to fault her for holding conventicles. Question by question, Hutchinson effectively stonewalled him in her responses, and Winthrop was unable to find a way to convert her known membership in a seditious faction into a convictable offence. Deputy governor Thomas Dudley

Thomas Dudley (12 October 157631 July 1653) was a New England colonial magistrate who served several terms as governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Dudley was the chief founder of Newtowne, later Cambridge, Massachusetts, and built the tow ...

had a substantial background in law, and he stepped in to assist the prosecution. Dudley questioned Hutchinson about her conventicles and her association with the other conspirators. With no answer by Hutchinson, he moved on to the charge of her slandering the ministers.

The remainder of the trial was spent on this last charge. The prosecution intended to demonstrate that Hutchinson had made disparaging remarks about the colony's ministers, and to use the October meeting as their evidence. Six ministers had presented to the court their written versions of the October conference, and Hutchinson agreed with the substance of their statements. Her defence was that she had spoken reluctantly and in private, that she "must either speak false or true in my answers" in the ministerial context of the meeting. In those private meetings, she had cited Proverbs 29:25, "The fear of man bringeth a snare: but whoso putteth his trust in the Lord shall be safe." The court was not interested in her distinction between public and private statements.

At the end of the first day of the trial, Winthrop recorded, "Mrs. Hutchinson, the court you see hath labored to bring you to acknowledge the error of your way that so you might be reduced. The time now grows late. We shall therefore give you a little more time to consider of it and therefore desire that you attend the court again in the morning." The first day had gone fairly well for Hutchinson, who had held her own in a battle of wits with the magistrates. Biographer Eve LaPlante suggests, "Her success before the court may have astonished her judges, but it was no surprise to her. She was confident of herself and her intellectual tools, largely because of the intimacy she felt with God."

The remainder of the trial was spent on this last charge. The prosecution intended to demonstrate that Hutchinson had made disparaging remarks about the colony's ministers, and to use the October meeting as their evidence. Six ministers had presented to the court their written versions of the October conference, and Hutchinson agreed with the substance of their statements. Her defence was that she had spoken reluctantly and in private, that she "must either speak false or true in my answers" in the ministerial context of the meeting. In those private meetings, she had cited Proverbs 29:25, "The fear of man bringeth a snare: but whoso putteth his trust in the Lord shall be safe." The court was not interested in her distinction between public and private statements.

At the end of the first day of the trial, Winthrop recorded, "Mrs. Hutchinson, the court you see hath labored to bring you to acknowledge the error of your way that so you might be reduced. The time now grows late. We shall therefore give you a little more time to consider of it and therefore desire that you attend the court again in the morning." The first day had gone fairly well for Hutchinson, who had held her own in a battle of wits with the magistrates. Biographer Eve LaPlante suggests, "Her success before the court may have astonished her judges, but it was no surprise to her. She was confident of herself and her intellectual tools, largely because of the intimacy she felt with God."

Civil trial: day 2

During the morning of the second day of the trial, it appeared that Hutchinson had been given some legal counsel the previous evening, and she had more to say. She continued to criticise the ministers of violating their mandate of confidentiality. She said that they had deceived the court by not telling about her reluctance to share her thoughts with them. She insisted that the ministers testify under oath, which they were hesitant to do. MagistrateSimon Bradstreet

Simon Bradstreet (baptized March 18, 1603/4In the Julian calendar, then in use in England, the year began on March 25. To avoid confusion with dates in the Gregorian calendar, then in use in other parts of Europe, dates between January and Ma ...

said that "she would make the ministers sin if they said something mistaken under oath", but she answered that if they were going to accuse her, "I desire it may be upon oath." As a matter of due process, the ministers would have to be sworn in, but would agree to do so only if the defence witnesses spoke first.

There were three such witnesses, all from the Boston church: deacon John Coggeshall

John Coggeshall Sr. (2 December 1599 – 27 November 1647) was one of the founders of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations and the first President of all four towns in the Colony. He was a successful silk merchant in Essex, Eng ...

, lay leader Thomas Leverett, and minister John Cotton. The first two witnesses made brief statements that had little effect on the court, but Cotton was questioned extensively. When Cotton testified, he tended not to remember many events of the October meeting, and attempted to soften the meaning of statements that Hutchinson was being accused of. He stressed that the ministers were not as upset about any Hutchinson remarks at the end of the October meeting as they appeared to be later. Dudley reiterated that Hutchinson had told the ministers that they were not able ministers of the New Testament; Cotton replied that he did not remember her saying that.

There was more parrying between Cotton and the court, but the exchanges were not picked up in the transcript of the proceedings. Hutchinson asked the court for leave to "give you the ground of what I know to be true." She then addressed the court with her own judgment:

This was the "dramatic high point of the most analyzed event of the free grace controversy", wrote historian Michael Winship. Historians have given a variety of reasons for this statement, including an "exultant impulse", "hysteria", "cracking under the strain of the inquest", and being "possessed of the Spirit". Winship, citing the work of historian Mary Beth Norton

Mary Beth Norton (born 1943) is an American historian, specializing in American colonial history and well known for her work on women's history and the Salem witch trials. She is the Mary Donlon Alger Professor Emeritus of American History at t ...

, suggests that Hutchinson consciously decided to explain why she knew that the divines of the colony were not able ministers of the New Testament. This was "not histrionics, but pedagogy," according to Winship; it was Hutchinson's attempt to teach the Court, and doing so was consistent with her character.

Civil trial: verdict

Hutchinson simplified the task of her opponents, whose prosecution had been somewhat shaky. Her revelation was considered not only seditious, but also incontempt of court

Contempt of court, often referred to simply as "contempt", is the crime of being disobedient to or disrespectful toward a court of law and its officers in the form of behavior that opposes or defies the authority, justice, and dignity of the cour ...

. Cotton was pressed by Dudley on whether or not he supported Hutchinson's revelation; he said that he could find theological justification for it. Cotton may have still been angry over the zeal with which some opponents had come after the dissidents within his congregation. Winthrop was not interested in this quibbling, though; he was using Hutchinson's bold assertions to lead the court in the direction of rewriting history, according to the historical interpretations of Winship. Many of the Puritans had been convinced that there was a single destructive prophetic figure behind all of the difficulties that the colony had been having, and Hutchinson had just become the culprit. Winthrop addressed the court, "if therefore it be the mind of the court, looking at eras the principal cause of all our trouble, that they would now consider what is to be done with her."

The Bostonians made a final effort to slow the proceedings. William Coddington

William Coddington (c. 1601 – 1 November 1678) was an early magistrate of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and later of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. He served as the judge of Portsmouth and Newport, governor of Portsmouth ...

rose, asserting, "I do not see any clear witness against her, and you know it is a rule of the court that no man may be a judge and an accuser too," ending with, "Here is no law of God that she hath broken nor any law of the country that she hath broke, and therefore deserve no censure." The court wanted a sentence but could not proceed until some of the ministers spoke. Three of the ministers were sworn in, and each testified against Hutchinson. Winthrop moved to have her banished; in the ensuing tally, only the Boston deputies voted against conviction. Hutchinson challenged the sentence's legitimacy, saying, "I desire to know wherefore I am banished." Winthrop responded, "The court knows wherefore and is satisfied."

Hutchinson was called a heretic and an instrument of the devil, and was condemned to banishment by the Court "as being a woman not fit for our society". The Puritans sincerely believed that, in banishing Hutchinson, they were protecting God's eternal truth. Winthrop summed up the case with genuine feeling:

Detention

Following her civil trial, Hutchinson was put under house arrest and ordered to be gone by the end of the following March. In the interim, she was not allowed to return home, but was detained at the house of Joseph Weld, brother of the ReverendThomas Weld Thomas Weld may refer to:

* Thomas Welde (1594/5–1661), first minister of the First Church of Roxbury, Massachusetts

* Thomas Weld (of Lulworth) (1750–1810), of Lulworth castle, Catholic philanthropist

* Thomas Weld (cardinal)

Thomas W ...

, located in Roxbury, about two miles from her home in Boston. The distance was not great, yet Hutchinson was rarely able to see her children because of the weather, which was particularly harsh that winter. Winthrop referred to Hutchinson as "the prisoner" and was determined to keep her isolated so that others would not be inspired by her, according to LaPlante. She was frequently visited by various ministers, whose intent, according to LaPlante, was to reform her thinking but also to collect evidence against her. Thomas Shepard was there to "collect errors", and concluded that she was a dangerous woman. Shepard and the other ministers who visited her drafted a list of her theological errors and presented them to the Boston church, which decided that she should stand trial for these views.

Church trial

Hutchinson was called to trial on Thursday, 15 March 1638, weary and in poor health following a four-month detention. The trial took place at her home church in Boston, though many of her supporters were gone. Her husband and other friends had already left the colony to prepare a new place to live. Her only family members present were her oldest sonEdward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

and his wife, her daughter Faith and son-in-law Thomas Savage, and her sister Katherine

Katherine, also spelled Catherine, and Catherina, other variations are feminine Given name, names. They are popular in Christian countries because of their derivation from the name of one of the first Christian saints, Catherine of Alexandria ...

with her husband Richard Scott.

The ministers intended to defend their orthodox doctrine and to examine Hutchinson's theological errors. Ruling elder Thomas Leverett was charged with managing the examination. He called Hutchinson and read the numerous errors with which she had been charged, and a nine-hour interrogation followed in which the ministers delved into some weighty points of theology. At the end of the session, only four of the many errors were covered, and Cotton was put in the uncomfortable position of delivering the admonition to his admirer. He said, "I would speake it to Gods Glory

The ministers intended to defend their orthodox doctrine and to examine Hutchinson's theological errors. Ruling elder Thomas Leverett was charged with managing the examination. He called Hutchinson and read the numerous errors with which she had been charged, and a nine-hour interrogation followed in which the ministers delved into some weighty points of theology. At the end of the session, only four of the many errors were covered, and Cotton was put in the uncomfortable position of delivering the admonition to his admirer. He said, "I would speake it to Gods Glory hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

you have bine an Instrument of doing some good amongst us… he hath given you a sharp apprehension, a ready utterance and abilitie to exprese yourselfe in the Cause of God." The ministers overwhelmingly concluded that Hutchinson's unsound beliefs outweighed all the good which she had done, and that she endangered the spiritual welfare of the community.

Cotton continued,

Here Cotton was making a link between Hutchinson's theological ideas and the more extreme behaviour credited to the antinomians and familists. He concluded:

With this, Hutchinson was instructed to return in one week on the next lecture day.

Cotton had not yet given up on his parishioner. With the permission of the court, Hutchinson was allowed to spend the week at his home, where the recently arrived Reverend John Davenport was also staying. All week, the two ministers worked with her and, under their supervision, she wrote out a formal recantation of her unsound opinions that had formerly brought objection. Hutchinson stood at the next meeting on Thursday, 22 March and read her recantation in a subdued voice to the congregation. She admitted to having been wrong about the soul and spirit, wrong about the resurrection of the body, wrong in prophesying the destruction of the colony, and wrong in her demeanour toward the ministers, and she agreed that sanctification could be evidence of justification (what she called a "covenant of works") "as it flowes from Christ and is witnessed to us by the Spirit". Had the trial ended there, she would likely have remained in good standing with the Boston church, and had the possibility of returning some day.

Wilson explored an accusation made by Shepard at the end of the previous meeting, and new words brought on new assaults. The outcome of her trial was uncertain following the first day's grilling, but her downfall came when she would not acknowledge that she held certain theological errors before her four-month imprisonment. With this, she was accused of lying but, even at this point, Winthrop and a few of the ministers wanted her soul redeemed because of her significant evangelical work before she "set forth her owne stuffe". To these sentiments, Shepard vehemently argued that Hutchinson was a "Notorious Imposter" in whose heart there was never any grace. He admonished the "heinousness of her lying" during a time of supposed humiliation.

Shepard had swayed the proceedings, with Cotton signalling that he had given up on her, and her sentence was presented by Wilson:

Hutchinson was now banished from the colony and removed from the congregation, and her leading supporters had been given three months to leave the colony, including Coddington and Coggeshall, while others were disenfranchised or dismissed from their churches. The court in November had ordered that 58 citizens of Boston and 17 from adjacent towns be disarmed unless they repudiated the "seditious label" given them, and many of these people followed Hutchinson into exile.

Rhode Island

During Hutchinson's imprisonment, several of her supporters prepared to leave the colony and settle elsewhere. One such group of men, including her husband Will, met on 7 March 1638 at the home of wealthy Boston merchant William Coddington. Ultimately, 23 men signed what is known as the

During Hutchinson's imprisonment, several of her supporters prepared to leave the colony and settle elsewhere. One such group of men, including her husband Will, met on 7 March 1638 at the home of wealthy Boston merchant William Coddington. Ultimately, 23 men signed what is known as the Portsmouth Compact

The Portsmouth Compact was a document signed on March 7, 1638 that established the settlement of Portsmouth, which is now a town in the state of Rhode Island. It was the first document in American history that severed both political and religious ...

, forming themselves into a "Bodie Politick" and electing Coddington as their governor, but giving him the Biblical title of "judge". Nineteen of the signers initially planned to move to New Jersey or Long Island, but Roger Williams

Roger Williams (21 September 1603between 27 January and 15 March 1683) was an English-born New England Puritan minister, theologian, and author who founded Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantation ...

convinced them to settle in the area of his Providence Plantations

Providence Plantations was the first permanent European American settlement in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. It was established by a group of colonists led by Roger Williams and Dr. John Clarke who left Massachusetts Bay ...

settlement. Coddington purchased Aquidneck Island

Aquidneck Island, also known as Rhode Island, is an island in Narragansett Bay in the state of Rhode Island. The total land area is , which makes it the largest island in the bay. The 2020 United States Census reported its population as 60,109. T ...

(later named Rhode Island) in the Narragansett Bay

Narragansett Bay is a bay and estuary on the north side of Rhode Island Sound covering , of which is in Rhode Island. The bay forms New England's largest estuary, which functions as an expansive natural harbor and includes a small archipelago. Sma ...

from the Narragansetts

The Narragansett people are an Algonquian American Indian tribe from Rhode Island. Today, Narragansett people are enrolled in the federally recognized Narragansett Indian Tribe. They gained federal recognition in 1983.

The tribe was nearly lan ...

, and the settlement of Pocasset was founded (soon renamed Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

). Anne Hutchinson followed in April, after the conclusion of her church trial.

Hutchinson, her children, and others accompanying her travelled for more than six days by foot in the April snow to get from Boston to Roger Williams' settlement at Providence. They took boats to get to Aquidneck Island, where many men had gone ahead of them to begin constructing houses. In the second week of April, she reunited with her husband, from whom she had been separated for nearly six months.

Final pregnancy

Hutchinson went into labour in May 1638, following the stress of her trial, her imprisonment all winter, and the difficult trip to Aquidneck Island. She delivered what her doctor John Clarke described as a handful of transparent grapes. This is known now as a hydatidiform mole, a condition occurring most often in women over 45, resulting from one or two sperm cells fertilising a blighted egg. Hutchinson had been ill most of the winter, with unusual weakness, throbbing headaches, and bouts of vomiting. Most writers on the subject agree that she had been pregnant during her trial. Historian Emery Battis, citing expert opinion, suggests that she may not have been pregnant at all during that time, but displaying acute symptoms ofmenopause

Menopause, also known as the climacteric, is the time in women's lives when menstrual periods stop permanently, and they are no longer able to bear children. Menopause usually occurs between the age of 47 and 54. Medical professionals often d ...

. The following April after reuniting with her husband, she became pregnant, only to miscarry the hydatidiform mole. A woman could have had severe menopausal symptoms who had undergone a continuous cycle of pregnancies, deliveries, and lactations for 25 years, with the burdens of raising a large family and subjected to the extreme stress of her trials.

The Puritan leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony gloated over Hutchinson's suffering and also that of Mary Dyer

Mary Dyer (born Marie Barrett; c. 1611 – 1 June 1660) was an English and colonial American Puritan turned Quaker who was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony. ...

, a follower who had the premature and stillbirth of a severely deformed infant. The leaders classified the women's misfortunes as the judgement of God. Winthrop wrote, "She brought forth not one, but thirty monstrous births or thereabouts", then continued, "see how the wisdom of God fitted this judgment to her sin every way, for look—as she had vented misshapen opinions, so she must bring forth deformed monsters." Massachusetts continued to persecute Hutchinson's followers who stayed in the Boston area. Laymen were sent from the Boston church to Portsmouth to convince Hutchinson of her errors; she shouted at them, "the Church at Boston? I know no such church, neither will I own it. Call it the whore and strumpet of Boston, but no Church of Christ!"

Dissension in government

Less than a year after Pocasset was settled, it suffered rifts and civil difficulties. Coddington had openly supported Hutchinson following her trial, but he had become autocratic and began to alienate his fellow settlers. Early in 1639, Hutchinson became acquainted withSamuel Gorton

Samuel Gorton (1593–1677) was an early settler and civic leader of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations and President of the towns of Providence and Warwick. He had strong religious beliefs which differed from Puritan theolog ...

, who attacked the legitimacy of the magistrates. On 28 April 1639, Gorton and a dozen other men ejected Coddington from power. Hutchinson may not have supported this rebellion, but her husband was chosen as the new governor. Two days later, over 30 men signed a document forming a new "civil body politic". Winthrop noted in his journal that at Aquidneck,