An Experiment On A Bird In The Air Pump on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump'' is a 1768 oil-on-canvas painting by

In 1659, Robert Boyle commissioned the construction of an air pump, then described as a "pneumatic engine", which is known today as a "

In 1659, Robert Boyle commissioned the construction of an air pump, then described as a "pneumatic engine", which is known today as a "

During his apprenticeship and early career Wright concentrated on portraiture. By 1762, he was an accomplished portrait artist, and his 1764 group portrait ''James Shuttleworth, his Wife and Daughter'' is acknowledged as his first true masterpiece.

During his apprenticeship and early career Wright concentrated on portraiture. By 1762, he was an accomplished portrait artist, and his 1764 group portrait ''James Shuttleworth, his Wife and Daughter'' is acknowledged as his first true masterpiece.

The first of his candlelit masterpieces, ''

The first of his candlelit masterpieces, ''

''An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump'' followed in 1768, the emotionally charged experiment contrasting with the orderly scene from ''The Orrery''. The painting, which measures 72 by 94½ inches (183 by 244 cm), shows a grey

''An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump'' followed in 1768, the emotionally charged experiment contrasting with the orderly scene from ''The Orrery''. The painting, which measures 72 by 94½ inches (183 by 244 cm), shows a grey

The cockatiel would have been a rare bird at the time, "and one whose life would never in reality have been risked in an experiment such as this".Egerton 1998, p. 340. It did not become well known until after it was shown in illustrations to the accounts of the voyages of

The cockatiel would have been a rare bird at the time, "and one whose life would never in reality have been risked in an experiment such as this".Egerton 1998, p. 340. It did not become well known until after it was shown in illustrations to the accounts of the voyages of

The powerful central light source creates a

The powerful central light source creates a

The scientific subjects of Wright's paintings from this time were meant to appeal to the wealthy scientific circles in which he moved. While never a member himself, he had strong connections with the

The scientific subjects of Wright's paintings from this time were meant to appeal to the wealthy scientific circles in which he moved. While never a member himself, he had strong connections with the  Wright exhibited the painting at the Society of Artists exhibition in 1768 and it was re-exhibited before

Wright exhibited the painting at the Society of Artists exhibition in 1768 and it was re-exhibited before

Google books

* * * * * * * * * Waterhouse, Ellis, (4th Edn, 1978) ''Painting in Britain, 1530–1790''. Penguin Books (now Yale History of Art series), *

Zoomable version of the painting from the National Gallery, LondonAn interactive soundscape of the painting

{{DEFAULTSORT:Experiment On A Bird In The Air Pump 1768 paintings Science in art Physics experiments Paintings by Joseph Wright of Derby Historical scientific instruments Collections of the National Gallery, London Birds in art

Joseph Wright of Derby

Joseph Wright (3 September 1734 – 29 August 1797), styled Joseph Wright of Derby, was an English landscape and portrait painter. He has been acclaimed as "the first professional painter to express the spirit of the Industrial Revolution".

Wr ...

, one of a number of candlelit scenes that Wright painted during the 1760s. The painting departed from convention of the time by depicting a scientific subject in the reverential manner formerly reserved for scenes of historical or religious significance. Wright was intimately involved in depicting the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

and the scientific advances of the Enlightenment. While his paintings were recognized as exceptional by his contemporaries, his provincial status and choice of subjects meant the style was never widely imitated. The picture has been owned by the National Gallery

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current Director ...

in London since 1863 and is regarded as a masterpiece of British art.

The painting depicts a natural philosopher

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wo ...

, a forerunner of the modern scientist, recreating one of Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders ...

's air pump

An air pump is a pump for pushing air. Examples include a bicycle pump, pumps that are used to aerate an aquarium or a pond via an airstone; a gas compressor used to power a pneumatic tool, air horn or pipe organ; a bellows used to encourage a ...

experiments, in which a bird is deprived of air, before a varied group of onlookers. The group exhibits a variety of reactions, but for most of the audience scientific curiosity overcomes concern for the bird. The central figure looks out of the picture as if inviting the viewer's participation in the outcome.

Historical background

In 1659, Robert Boyle commissioned the construction of an air pump, then described as a "pneumatic engine", which is known today as a "

In 1659, Robert Boyle commissioned the construction of an air pump, then described as a "pneumatic engine", which is known today as a "vacuum pump

A vacuum pump is a device that draws gas molecules from a sealed volume in order to leave behind a partial vacuum. The job of a vacuum pump is to generate a relative vacuum within a capacity. The first vacuum pump was invented in 1650 by Otto ...

". The air pump was invented by Otto von Guericke

Otto von Guericke ( , , ; spelled Gericke until 1666; November 20, 1602 – May 11, 1686 ; November 30, 1602 – May 21, 1686 ) was a German scientist, inventor, and politician. His pioneering scientific work, the development of experimental me ...

in 1650, though its high cost deterred most contemporary scientists from constructing the apparatus. Boyle, the son of the Earl of Cork

Earl of Cork is a title in the Peerage of Ireland, held in conjunction with the Earldom of Orrery since 1753. It was created in 1620 for Richard Boyle, 1st Baron Boyle. He had already been created Lord Boyle, Baron of Youghal, in the County o ...

, had no such concerns—after its construction, he donated the initial 1659 model to the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

and had a further two redesigned machines built for his personal use. Aside from Boyle's three pumps, there were probably no more than four others in existence during the 1660s: Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists o ...

had one in The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

, Henry Power

Henry Power (1623–1668) was an English physician and experimenter, one of the first elected fellows of the Royal Society.

Life

Power matriculated as a pensioner of Christ's College, Cambridge, in 1641 and graduated a Bachelor of Arts in 1644. ...

may have had one at Halifax, and there may have been pumps at Christ's College, Cambridge

Christ's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college includes the Master, the Fellows of the College, and about 450 undergraduate and 170 graduate students. The college was founded by William Byngham in 1437 as ...

, and the Montmor Academy in Paris. Boyle's pump, which was largely designed to Boyle's specifications and constructed by Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

, was complicated, temperamental, and problematic to operate. Many demonstrations could only be performed with Hooke on hand, and Boyle frequently left critical public displays solely to Hooke—whose dramatic flair matched his technical skill.

Despite the operational and maintenance obstacles, construction of the pump enabled Boyle to conduct a great many experiments on the properties of air, which he later detailed in his ''New Experiments Physico-Mechanicall, Touching the Spring of the Air, and its Effects, (Made, for the Most Part, in a New Pneumatical Engine)''. In the book, he described in great detail 43 experiments he conducted, on occasion assisted by Hooke, on the effect of air on various phenomena. Boyle tested the effects of "rarified" air on combustion, magnetism, sound, and barometers, and examined the effects of increased air pressure

Atmospheric pressure, also known as barometric pressure (after the barometer), is the pressure within the atmosphere of Earth. The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as , which is equivalent to 1013.25 millibars ...

on various substances. He listed two experiments on living creatures: "Experiment 40", which tested the ability of insects to fly under reduced air pressure, and the dramatic "Experiment 41," which demonstrated the reliance of living creatures on air for their survival. In this attempt to discover something "about the account upon which Respiration is so necessary to the Animals, that Nature hath furnish'd with Lungs", Boyle conducted numerous trials during which he placed a large variety of different creatures, including birds, mice, eels, snails and flies, in the vessel of the pump and studied their reactions as the air was removed. Here, he describes an injured lark

Larks are passerine birds of the family Alaudidae. Larks have a cosmopolitan distribution with the largest number of species occurring in Africa. Only a single species, the horned lark, occurs in North America, and only Horsfield's bush lark oc ...

:

By the time Wright painted his picture in 1768, air pumps were a relatively commonplace scientific instrument, and itinerant "lecturers in natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancien ...

"—usually more showmen than scientists—often performed the "animal in the air pump experiment" as the centrepiece of their public demonstration.Elliott 2000, pp. 61–100. These were performed in town halls and other large buildings for a ticket-buying audience, or were booked by societies or for private showings in the homes of the well-off, the setting suggested in both of Wright's demonstration pieces. One of the most notable and respectable of the travelling lecturers was James Ferguson James Ferguson may refer to:

Entertainment

* Jim Ferguson (born 1948), American jazz and classical guitarist

* Jim Ferguson, American guitarist, past member of Lotion

* Jim Ferguson, American movie critic, Board of Directors member for the Broadc ...

FRS, a Scottish astronomer and probable acquaintance of Joseph Wright (both were friends of John Whitehurst

John Whitehurst FRS (10 April 1713 – 18 February 1788), born in Cheshire, England, was a clockmaker and scientist, and made significant early contributions to geology. He was an influential member of the Lunar Society.

Life and work

Whit ...

). Ferguson noted that a "lungs-glass" with a small air-filled bladder inside was often used in place of the animal, as using a living creature was "too shocking to every spectator who has the least degree of humanity".Baird 2003.

The full moon in the picture is significant as meetings of the Lunar Circle (renamed the Lunar Society

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a British dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly between 1765 and 1813 ...

by 1775) were timed to make use of its light when travelling.

Wright met Erasmus Darwin

Erasmus Robert Darwin (12 December 173118 April 1802) was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor, and poet.

His poems ...

in the early 1760s, probably through their common connection of John Whitehurst

John Whitehurst FRS (10 April 1713 – 18 February 1788), born in Cheshire, England, was a clockmaker and scientist, and made significant early contributions to geology. He was an influential member of the Lunar Society.

Life and work

Whit ...

, first consulting Darwin about ill health in 1767 when he stayed in the Darwin household for a week. The energy and vivacity of both Erasmus and Mary (Polly) Darwin impressed Wright. In the 1980s Eric Evans (National Gallery) suggested that Darwin is the figure in the left foreground who holds a watch. As this composed timekeeper is not consistent with Darwin's flamboyant character, it is more likely that this is Dr William Small

William Small (13 October 1734 – 25 February 1775) was a Scottish physician and a professor of natural philosophy at the College of William and Mary in Virginia, where he became an influential mentor for Thomas Jefferson. Early life

William Sm ...

. The attention to timekeeping fits with Dr Small's role as the social secretary for the Lunar Circle. Small returned from Virginia in 1764 and established his practice in Birmingham in 1765, consistent with this being a meeting in 1767. The profile and wig of this figure are consistent with a contemporary portrait of Small by Tilly Kettle

Tilly Kettle (1735–1786) was a portrait painter and the first prominent English portrait painter to operate in India.

Life

He was born in London, the son of a coach painter, in a family that had been members of the Brewers' Company of freem ...

.

Painting

Background

During his apprenticeship and early career Wright concentrated on portraiture. By 1762, he was an accomplished portrait artist, and his 1764 group portrait ''James Shuttleworth, his Wife and Daughter'' is acknowledged as his first true masterpiece.

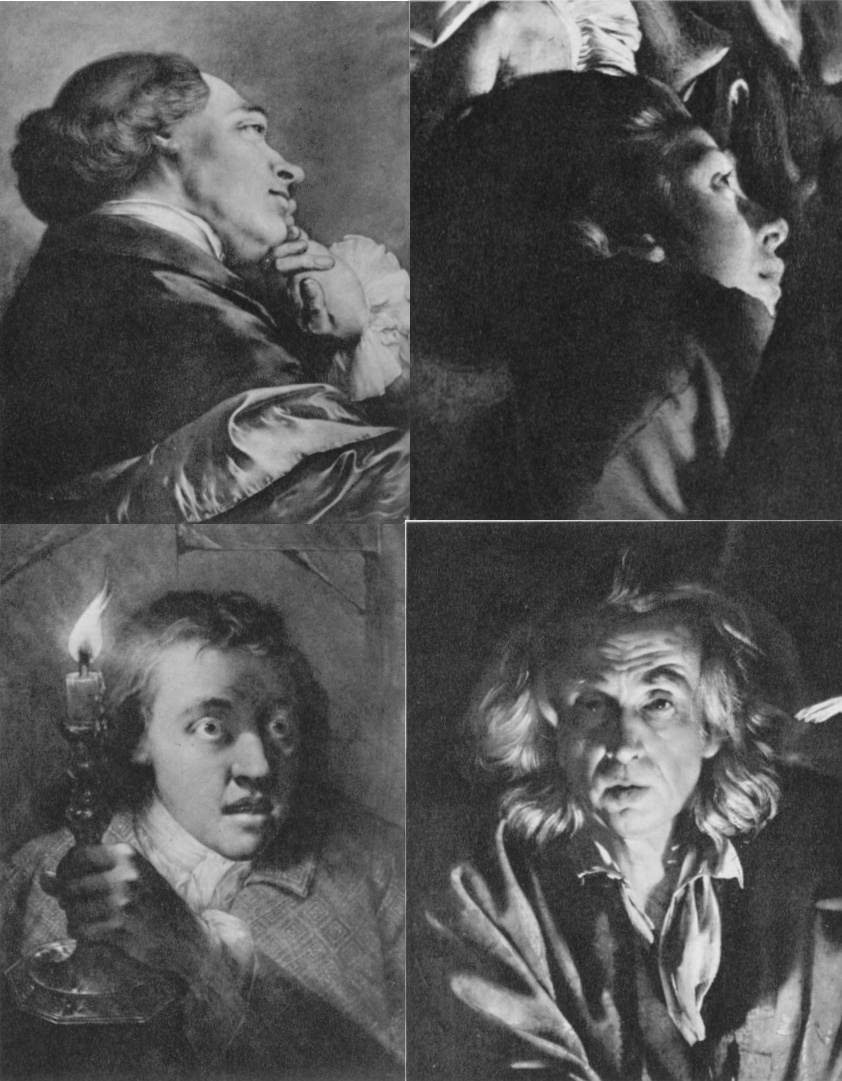

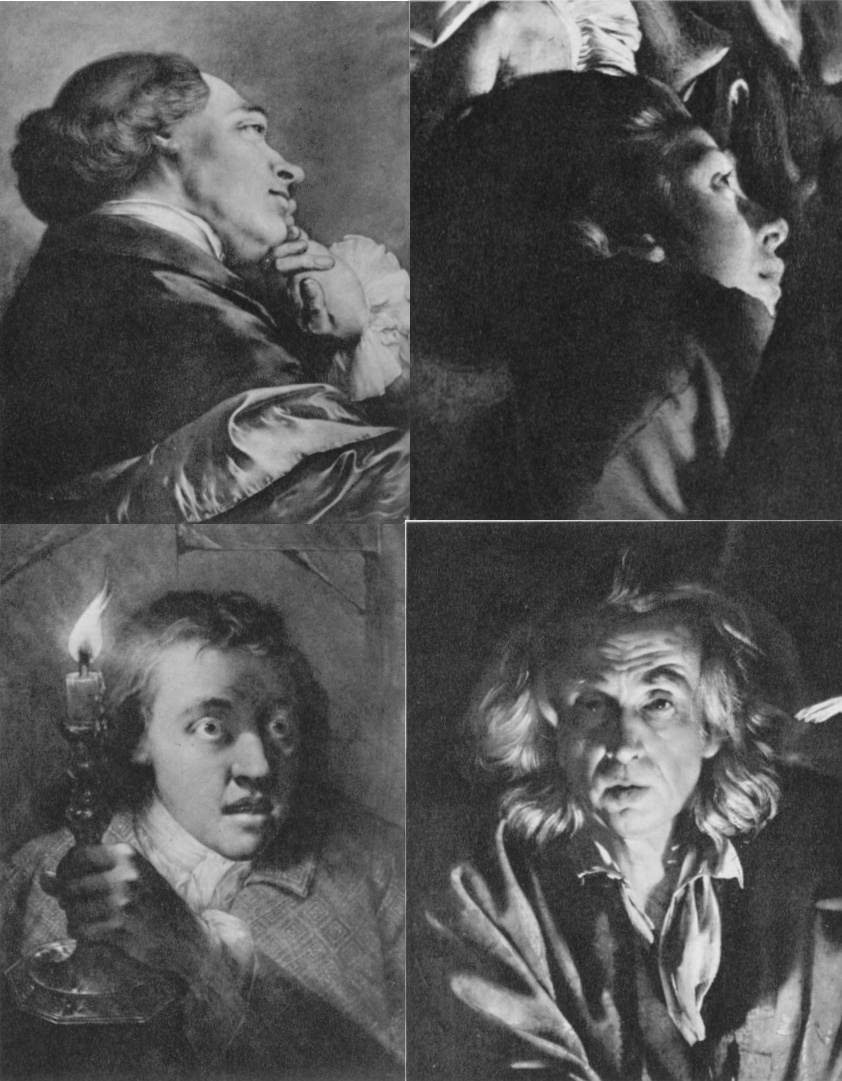

During his apprenticeship and early career Wright concentrated on portraiture. By 1762, he was an accomplished portrait artist, and his 1764 group portrait ''James Shuttleworth, his Wife and Daughter'' is acknowledged as his first true masterpiece. Benedict Nicolson

Lionel Benedict Nicolson (6 August 1914 – 22 May 1978) was a British art historian and author.

Nicolson was the elder son of authors Harold Nicolson and Vita Sackville-West and the brother of writer and politician Nigel. His godmothers ...

suggests that Wright was influenced by the work of Thomas Frye

Thomas Frye (c. 1710 – 3 April 1762) was an Anglo-Irish artist, best known for his portraits in oil and pastel, including some miniatures and his early mezzotint engravings. He was also the patentee of the Bow porcelain factory, London, ...

; in particular by the 18 bust-length mezzotint

Mezzotint is a monochrome printmaking process of the '' intaglio'' family. It was the first printing process that yielded half-tones without using line- or dot-based techniques like hatching, cross-hatching or stipple. Mezzotint achieves tonal ...

s which Frye completed just before his death in 1762. It was perhaps Frye's candlelight images that tempted Wright to experiment with subject pieces. Wright's first attempt, ''A Girl reading a Letter by candlelight with a Young Man looking over her shoulder'' from 1762 or 1763, is a trial in the genre, and is fetching though uncomplicated.

Wright's ''An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump'' forms part of a series of candlelit nocturnes that he produced between 1765 and 1768.

There was a long history of painting candlelit scenes in Western art, although as Wright had not at this date travelled abroad, there remains uncertainty as to what paintings he might have seen in the original, as opposed to prints

In molecular biology, the PRINTS database is a collection of so-called "fingerprints": it provides both a detailed annotation resource for protein families, and a diagnostic tool for newly determined sequences. A fingerprint is a group of conserved ...

. Nicolson, who made studies of both Wright and other candlelight painters such as the 17th-century Utrecht Caravaggisti

Utrecht Caravaggism ( nl, Utrechtse caravaggisten) refers to the work of a group of artists who were from, or had studied in, the Dutch city of Utrecht, and during their stay in Rome during the early seventeenth century had become distinctly infl ...

, thought their paintings, among the largest in the style, those most likely to have influenced Wright. However Judy Egerton wonders if he could have seen any, preferring as influences the far smaller works of the Leiden fijnschilder Godfried Schalcken

Godfried Schalcken (1643 – 16 November 1706) was a Dutch genre and portrait painter. He was noted for his mastery in reproducing the effect of candlelight, and painted in the exquisite and highly polished manner of the Leiden fijnschilders.

L ...

(1643–1706), whose reputation was much greater in the early 18th century than subsequently. He had worked in England from 1692 to 1697, and several of his paintings can be placed in English collections in Wright's day.

Although he was the leading expert writing in English, Nicolson does not suggest that Wright is likely to have known of the 17th-century candlelit narrative religious subjects of Georges de La Tour

Georges de La Tour (13 March 1593 – 30 January 1652) was a French Baroque painter, who spent most of his working life in the Duchy of Lorraine, which was temporarily absorbed into France between 1641 and 1648. He painted mostly religious chia ...

and Trophime Bigot

Trophime Bigot (1579–1650), also known as Théophile Bigot, Teofili Trufemondi, the Candlelight Master (''Maître à la Chandelle''), was a French painter of the Baroque era, active in Rome and his native Provence.

Bigot was born in Arles in 1 ...

, which, in their seriousness, are the closest works to Wright that are lit only by candle. The Dutch painters' works and other candlelit scenes by 18th-century English painters such as Henry Morland (father of George) tended instead to exploit the possibilities of semi-darkness for erotic suggestiveness. Some of Wright's own later candlelit scenes were by no means as serious as his first ones, as seen from their titles: ''Two Boys Fighting Over a Bladder'' and '' Two Girls Dressing a Kitten by Candlelight''.

The first of his candlelit masterpieces, ''

The first of his candlelit masterpieces, ''Three Persons Viewing the Gladiator by Candlelight

''Three Persons Viewing the Gladiator by Candlelight'' is a 1765 painting by Joseph Wright of Derby and now resides in the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool nited Kingdom It depicts three men examining a reproduction of the Borghese Gladiator, a ...

'', was painted in 1765, and showed three men studying a small copy of the "Borghese Gladiator

The ''Borghese Gladiator'' is a Hellenistic life-size marble sculpture portraying a swordsman, created at Ephesus about 100 BC, now on display at the Louvre.

Sculptor

The sculpture is signed on the pedestal by Agasias, son of Dositheus, who i ...

". ''Viewing the Gladiator'' was greatly admired; but his next painting, '' A Philosopher giving that Lecture on the Orrery, in which a Lamp is put in place of the Sun'' (normally known by the shortened form ''A Philosopher Giving a Lecture on the Orrery'' or just ''The Orrery''), caused a greater stir, as it replaced the Classical subject at the centre of the scene with one of a scientific nature. Wright's depiction of the awe produced by scientific "miracles" marked a break with traditions in which the artistic depiction of such wonder was reserved for religious events, since to Wright the marvels of the technological age were as awe-inspiring as the subjects of the great religious paintings.

In both of these works the candlelit setting had a realist justification. Viewing sculpture by candlelight, when the contours showed well and there might even be an impression of movement from the flickering light, was a fashionable practice described by Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as tr ...

. In the orrery demonstration the shadows cast by the lamp representing the sun were an essential part of the display, used to demonstrate eclipse

An eclipse is an astronomical event that occurs when an astronomical object or spacecraft is temporarily obscured, by passing into the shadow of another body or by having another body pass between it and the viewer. This alignment of three c ...

s. But there seems no reason other than heightened drama to stage the air pump experiment in a room lit by a single candle, and in two later paintings of the subject by Charles-Amédée-Philippe van Loo

Charles-Amédée-Philippe van Loo (25 August 1719 – 15 November 1795) was a French painter of allegorical scenes and portraits.

He studied under his father, the painter Jean-Baptiste van Loo, at Turin and Rome, where in 1738 he won the Pr ...

the lighting is normal.

The painting was one of a number of British works challenging the set categories of the rigid, French-dictated hierarchy of genres

A hierarchy of genres is any formalization which ranks different genres in an art form in terms of their prestige and cultural value.

In literature, the epic was considered the highest form, for the reason expressed by Samuel Johns ...

in the late 18th century, as other types of painting aspired to be treated as seriously as the costumed history painting

History painting is a genre in painting defined by its subject matter rather than any artistic style or specific period. History paintings depict a moment in a narrative story, most often (but not exclusively) Greek and Roman mythology and Bible ...

of a Classical or mythological subject. In some respects the ''Orrery'' and ''Air Pump'' subjects resembled conversation pieces

Conversation Pieces is a reworking of the Animated Conversations concept. It consists of a series of five shorts which aired on Channel Four between 1982 and 1983. Each of the 5 shorts were five minutes long.

As AllAboutAardman explains, "in the ...

, then largely a form of middle-class portraiture, though soon to be given new status when Johann Zoffany

Johan Joseph Zoffany (born Johannes Josephus Zaufallij; 13 March 1733 – 11 November 1810) was a German neoclassical painter who was active mainly in England, Italy and India. His works appear in many prominent British collections, includin ...

began to paint the royal family in about 1766. Given their solemn atmosphere however, and as it seems none of the figures are intended to be understood as portraits (even if models may be identified), the paintings can not be regarded as conversation pieces. The 20th-century art historian Ellis Waterhouse

Sir Ellis Kirkham Waterhouse (16 February 1905 – 7 September 1985) was an English art historian and museum director who specialised in Roman baroque and English painting. He was Director of the National Galleries of Scotland (1949–52) a ...

compares these two works to the "''genre serieux''" of contemporary French drama, as defined by Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the '' Encyclopédie'' along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a promi ...

and Pierre Beaumarchais

Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais (; 24 January 1732 – 18 May 1799) was a French polymath. At various times in his life, he was a watchmaker, inventor, playwright, musician, diplomat, spy, publisher, horticulturist, arms dealer, satirist, ...

, a view endorsed by Egerton.

An anonymous review from the time called Wright "a very great and uncommon genius in a peculiar way".Solkin 1994, p. 234. ''The Orrery'' was painted without a commission, probably in the expectation that it would be bought by Washington Shirley, 5th Earl Ferrers, an amateur astronomer who had an orrery

An orrery is a mechanical model of the Solar System that illustrates or predicts the relative positions and motions of the planets and moons, usually according to the heliocentric model. It may also represent the relative sizes of these bodies ...

of his own, and with whom Wright's friend Peter Perez Burdett

Peter Perez Burdett (c. 1734 – 9 September 1793) was an 18th-century cartographer, surveyor, artist, and draughtsman originally from Eastwood in Essex where he inherited a small estate and chose the name ''Perez'' from the birth surname o ...

was staying while in Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands, England. It includes much of the Peak District National Park, the southern end of the Pennine range of hills and part of the National Forest. It borders Greater Manchester to the nor ...

. Figures thought to be portraits of Burdett and Ferrers feature in the painting, Burdett taking notes and Ferrers seated with his son next to the orrery.

Ferrers purchased the painting for £210, but the 6th Earl auctioned it off, and it is now held by Derby Museum and Art Gallery

Derby Museum and Art Gallery is a museum and art gallery in Derby, England. It was established in 1879, along with Derby Central Library, in a new building designed by Richard Knill Freeman and given to Derby by Michael Thomas Bass. The colle ...

.Uglow 2002, p. 123.

Detail

''An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump'' followed in 1768, the emotionally charged experiment contrasting with the orderly scene from ''The Orrery''. The painting, which measures 72 by 94½ inches (183 by 244 cm), shows a grey

''An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump'' followed in 1768, the emotionally charged experiment contrasting with the orderly scene from ''The Orrery''. The painting, which measures 72 by 94½ inches (183 by 244 cm), shows a grey cockatiel

The cockatiel (; ''Nymphicus hollandicus''), also known as weiro (also spelt weero), or quarrion, is a medium-sized parrot that is a member of its own branch of the cockatoo family endemic to Australia. They are prized as household pets and c ...

fluttering in panic as the air is slowly withdrawn from the vessel by the pump. The witnesses display various emotions: one of the girls worriedly watches the fate of the bird, while the other is too upset to observe and is comforted by her father; two gentlemen (one of them dispassionately timing the experiment) and a boy look on with interest, while the young lovers to the left of the painting are absorbed only in each other. The scientist himself looks directly out of the picture, as if challenging the viewer to judge whether the pumping should continue, killing the bird, or whether the air should be replaced and the cockatiel saved.Jones 2003.

Aside from that of the children, little sympathy is directed toward the bird; David Solkin suggests the subjects of the painting show the dispassionate detachment of the evolving scientific society. Individuals are concerned for each other: the father for his children, the young man for the girl, but the distress of the cockatiel elicits only careful study.Solkin 1994, p. 247. To one side of the boy at the rear, the cockatiel's empty cage can be seen on the wall, and to further heighten the drama it is unclear whether the boy is lowering the cage on the pulley to allow the bird to be replaced after the experiment or hoisting the cage back up, certain of its former occupant's death. It has also been suggested that he may be drawing the curtains to block out the light from the full moon.

Jenny Uglow

Jennifer Sheila Uglow (, (accessed 5 February 2008).

(accessed 19 August 2022). born 1947) is an English biographer, hi ...

believes that the boy echoes the figure in the last print of (accessed 19 August 2022). born 1947) is an English biographer, hi ...

William Hogarth

William Hogarth (; 10 November 1697 – 26 October 1764) was an English painter, engraver, pictorial satirist, social critic, editorial cartoonist and occasional writer on art. His work ranges from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like ...

's ''The Four Stages of Cruelty

''The Four Stages of Cruelty'' is a series of four printed engravings published by English artist William Hogarth in 1751. Each print depicts a different stage in the life of the fictional Tom Nero.

Beginning with the torture of a dog as a ch ...

'' by pointing out the arrogance and potential cruelty of experimentation, while David Fraser also sees the compositional similarities with the audience grouped round a central demonstration. The neutral stance of the central character and the uncertain intentions of the boy with the cage were both later ideas: an early study, discovered on the back of a self-portrait, omits the boy and shows the natural philosopher reassuring the girls. In this sketch it is obvious that the bird will survive, and thus the composition lacks the power of the final version.

Wright, who took many of his subjects from English poetry, probably knew the following passage from "The Wanderer" (1729) by Richard Savage:

:So in some Engine, that denies a Vent, :If unrespiring is some Creature pent, :It sickens, droops, and pants, and gasps for Breath, :Sad o'er the Sight swim shad'wy Mists of Death; :If then kind Air pours powerful in again. :New Heats, new Pulses quicken ev'ry Vein; :From the clear'd, lifted, life-rekindled Eye, :Dispers'd, the dark and dampy Vapours fly.

The cockatiel would have been a rare bird at the time, "and one whose life would never in reality have been risked in an experiment such as this".Egerton 1998, p. 340. It did not become well known until after it was shown in illustrations to the accounts of the voyages of

The cockatiel would have been a rare bird at the time, "and one whose life would never in reality have been risked in an experiment such as this".Egerton 1998, p. 340. It did not become well known until after it was shown in illustrations to the accounts of the voyages of Captain Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

in the 1770s. Prior to Cook's voyage, cockatiels had been imported only in small numbers as exotic cage-birds. Wright had painted one in 1762 at the home of William Chase, featuring it both in his portrait of Chase and his wife (''Mr & Mrs William Chase'') and a separate study, ''The Parrot''.Egerton 1990, pp. 58–61. In selecting such a rarity for this scientific sacrifice, Wright not only chose a more dramatic subject than the "lungs-glass", but was perhaps making a statement about the values of society in the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

. The grey plumage of the cockatiel also shows much more effectively in the darkened room than the small dull-coloured bird in Wright's early oil sketch. A resemblance has been pointed out between the group of the bird and the two nearest figures and a type of depiction of the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

found in Early Netherlandish painting

Early Netherlandish painting, traditionally known as the Flemish Primitives, refers to the work of artists active in the Burgundian and Habsburg Netherlands during the 15th- and 16th-century Northern Renaissance period. It flourished especia ...

, where the Holy Spirit

In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is the divine force, quality, and influence of God over the Universe or over his creatures. In Nicene Christianity, the Holy Spirit or Holy Ghost is the third person of the Trinity. In Islam, the Holy Spirit acts as ...

is represented by a dove, to which God the Father

God the Father is a title given to God in Christianity. In mainstream trinity, trinitarian Christianity, God the Father is regarded as the first person of the Trinity, followed by the second person, God the Son Jesus Christ, and the third pers ...

(the philosopher) points, while Christ (the father) gestures in blessing to the viewer.

On the table are various other pieces of equipment that the natural philosopher would have used during his demonstration: a thermometer, candle snuffer and cork, and close to the man seated to the right is a pair of Magdeburg hemispheres

The Magdeburg hemispheres are a pair of large copper hemispheres, with mating rims. They were used to demonstrate the power of atmospheric pressure. When the rims were sealed with grease and the air was pumped out, the sphere contained a vacuum a ...

, which would have been used with the air pump to demonstrate the difference in pressure exerted by the air and a vacuum: when the air was pumped out from between the two hemispheres they were impossible to pull apart. The air pump itself is rendered in exquisite detail, a faithful record of the designs in use at the time. What may be a human skull in the large liquid-filled glass bowl would not have been a normal piece of equipment; William Schupbach suggests that it and the candle, which is presumably lighting the bowl from behind, form a ''vanitas

A ''vanitas'' (Latin for 'vanity') is a symbolic work of art showing the temporality, transience of life, the futility of pleasure, and the certainty of death, often contrasting symbols of wealth and symbols of ephemerality and death. Best-kn ...

''—the two symbols of mortality reflecting the cockatiel's struggle for life.

Style

The powerful central light source creates a

The powerful central light source creates a chiaroscuro

Chiaroscuro ( , ; ), in art, is the use of strong contrasts between light and dark, usually bold contrasts affecting a whole composition. It is also a technical term used by artists and art historians for the use of contrasts of light to achi ...

effect. The light illuminating the scene has been described as "so brilliant it could only be the light of revelation". The single source of light is obscured behind the bowl on the table; some hint of a lamp glass can be seen around the side of the bowl, but David Hockney

David Hockney (born 9 July 1937) is an English painter, draftsman, printmaker, stage designer, and photographer. As an important contributor to the pop art movement of the 1960s, he is considered one of the most influential British artists o ...

has suggested that the bowl itself may contain sulphur, giving a powerful single light source that a candle or oil lamp would not.Hockney 2001, p. 129. In the earlier study a candle holder is visible, and the flame is reflected in the bowl. Hockney believes that many of the Old Master

In art history, "Old Master" (or "old master")Old Masters De ...

s used optical equipment to assist in their painting, and suggests that Wright may have used lenses to transfer the image to paper rather than painting directly from the scene, as he believes the pattern of shadows thrown by the lighting could have been too complicated for Wright to have captured so accurately without assistance. It may be observed, however, that the stand on which the pump is situated casts no shadow on the body of the philosopher, as it could be expected to do.

Wright's ''Air Pump'' was unusual in that it depicted archetypes rather than specific people, though various models for the figures have been suggested. The young lovers may have been based on Thomas Coltman and Mary Barlow, friends of Wright's, whom he later painted in ''Mr and Mrs Thomas Coltman'' (also in the National Gallery) after their marriage in 1769; Erasmus Darwin

Erasmus Robert Darwin (12 December 173118 April 1802) was an English physician. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave-trade abolitionist, inventor, and poet.

His poems ...

has been suggested as the man timing the experiment on the left of the table, and John Warltire, whom Darwin had invited to help with some air pump experiments in real life, as the natural philosopher; but Wright never identified any of the subjects or suggested they were based on real people.

In ''The Orrery'', all the subjects have been identified apart from the philosopher, who has physical similarities to Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, Theology, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosophy, natural philosopher"), widely ...

but differs enough to make positive identification impossible. Nicolson detects the strong influence of Frye throughout the picture. Particularly striking is the similarity between Frye's mezzotint ''Portrait of a Young Man'' of 1760–1761 and the figure of the boy with his head cocked staring intently at the bird. In 1977, Michael Wynne published one of Frye's chalk drawings from around 1760, ''An old man leaning on a staff'', which is so similar to the observer in the right foreground in Wright's picture to make it impossible that Wright had not seen it. There are other hints of Frye's style in the painting: even the figure of the natural philosopher has touches of Frye's ''Figure with Candle''. Though Henry Fuseli

Henry Fuseli ( ; German: Johann Heinrich Füssli ; 7 February 1741 – 17 April 1825) was a Swiss painter, draughtsman and writer on art who spent much of his life in Britain. Many of his works, such as ''The Nightmare'', deal with supernatur ...

would later also develop on the style of Frye's work there is no evidence of him having painted anything similar until the early 1780s. So, although he had already been in England at the time the ''Air Pump'' was produced, it is unlikely that he was an influence on Wright.

Wright's scientific paintings adopted elements from the tradition of history painting

History painting is a genre in painting defined by its subject matter rather than any artistic style or specific period. History paintings depict a moment in a narrative story, most often (but not exclusively) Greek and Roman mythology and Bible ...

but lacked the heroic central action typical of that genre. While ground-breaking, they are regarded as peculiar to Wright, whose unique style has been explained in many ways. Wright's provincial status and ties to the Lunar Society

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a British dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly between 1765 and 1813 ...

, a group of prominent industrialists, scientists and intellectuals who met regularly in Birmingham between 1765 and 1813, have been highlighted, as well as his close association with and sympathy for the advances made in the burgeoning Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

. Other critics have emphasised a desire to capture a snapshot of the society of the day, in the tradition of William Hogarth but with a more neutral stance that lacks the biting satire of Hogarth's work.Solkin 1994, p. 235.

Reception

The scientific subjects of Wright's paintings from this time were meant to appeal to the wealthy scientific circles in which he moved. While never a member himself, he had strong connections with the

The scientific subjects of Wright's paintings from this time were meant to appeal to the wealthy scientific circles in which he moved. While never a member himself, he had strong connections with the Lunar Society

The Lunar Society of Birmingham was a British dinner club and informal learned society of prominent figures in the Midlands Enlightenment, including industrialists, natural philosophers and intellectuals, who met regularly between 1765 and 1813 ...

: he was friends with members John Whitehurst and Erasmus Darwin, as well as Josiah Wedgwood

Josiah Wedgwood (12 July 1730 – 3 January 1795) was an English potter, entrepreneur and abolitionist. Founding the Wedgwood company in 1759, he developed improved pottery bodies by systematic experimentation, and was the leader in the indus ...

, who later commissioned paintings from him.Harrison 2006, p. 317. The inclusion of the moon in the painting was a nod to their monthly meetings, which were held when the moon was full. Like ''The Orrery'', Wright apparently painted ''Air Pump'' without a commission, and the picture was purchased by Dr Benjamin Bates

Benjamin Edward Bates II (13 March 1716 – 12 May 1790) was a British physician, art connoisseur, and socialite. Born into wealth, he was a prominent member of society and was selected to become a member of the Sir Francis Dashwood's Hellfir ...

, who already owned Wright's ''Gladiator''. An Aylesbury physician, patron of the arts and hedonist, Bates was a diehard member of the Hellfire Club. Wright's account book shows a number of prices for the painting: Pd£200 is shown in one place and £210 in another, but Wright had written to Bates asking for £130, stating that the low price "might much injure me in the future sale of my pictures, and when I send you a receipt for the money I shall acknowledge a greater sum." Whether Bates ever paid the full amount is not recorded; Wright only notes in his account book that he received £30 in part payment.Nicolson 1968, p. 235.

Wright exhibited the painting at the Society of Artists exhibition in 1768 and it was re-exhibited before

Wright exhibited the painting at the Society of Artists exhibition in 1768 and it was re-exhibited before Christian VII of Denmark

Christian VII (29 January 1749 – 13 March 1808) was a monarch of the House of Oldenburg who was King of Denmark–Norway and Duke of Schleswig and Holstein from 1766 until his death in 1808. For his motto he chose: "''Gloria ex amore patriae'' ...

in September the same year. Viewers remarked that it was "clever and vigorous", while Gustave Flaubert

Gustave Flaubert ( , , ; 12 December 1821 – 8 May 1880) was a French novelist. Highly influential, he has been considered the leading exponent of literary realism in his country. According to the literary theorist Kornelije Kvas, "in Flauber ...

, who saw it on a visit to England in 1865–66, considered it "charmant de naïveté et profondeur". It was popular enough that a mezzotint was engraved from it by Valentine Green

Valentine Green (3 October 173929 July 1813) was a British mezzotinter and print publisher. Green trained under Robert Hancock, a Worcester engraver, after which he moved to London and began working as a mezzotint engraver. He began to exhibit ...

which was published by John Boydell on 24 June 1769, and initially sold for 15 shillings. This was reprinted throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, in increasingly weak impressions. Ellis Waterhouse called it "one of the wholly original masterpieces of British art".

From Bates, the picture passed to Walter Tyrell; another member of the Tyrell family, Edward, presented it to the National Gallery

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current Director ...

, London, in 1863, after it had failed to sell at an auction at Christie's

Christie's is a British auction house founded in 1766 by James Christie. Its main premises are on King Street, St James's in London, at Rockefeller Center in New York City and at Alexandra House in Hong Kong. It is owned by Groupe Artémi ...

in 1854. The painting was transferred to the Tate Gallery

Tate is an institution that houses, in a network of four art galleries, the United Kingdom's national collection of British art, and international modern and contemporary art. It is not a government institution, but its main sponsor is the U ...

in 1929, although it was actually on loan to Derby Museum and Art Gallery

Derby Museum and Art Gallery is a museum and art gallery in Derby, England. It was established in 1879, along with Derby Central Library, in a new building designed by Richard Knill Freeman and given to Derby by Michael Thomas Bass. The colle ...

between 1912 and 1947. It has been lent out for exhibitions to the National Gallery of Art

The National Gallery of Art, and its attached Sculpture Garden, is a national art museum in Washington, D.C., United States, located on the National Mall, between 3rd and 9th Streets, at Constitution Avenue NW. Open to the public and free of ch ...

in Washington, D.C. in 1976, the National Museum of Fine Arts in Stockholm in 1979–1980, and Paris (Grand Palais

The Grand Palais des Champs-Élysées ( en, Great Palace of the Elysian Fields), commonly known as the Grand Palais (English: Great Palace), is a historic site, exhibition hall and museum complex located at the Champs-Élysées in the 8th ...

), New York (Metropolitan

Metropolitan may refer to:

* Metropolitan area, a region consisting of a densely populated urban core and its less-populated surrounding territories

* Metropolitan borough, a form of local government district in England

* Metropolitan county, a typ ...

) and the Tate in London in 1990. It was reclaimed by the National Gallery from the Tate in 1986. They describe its condition as good, with minor alterations visible on some figures. It was last cleaned in 1974.

The painting is scheduled to be exhibited at the Huntington Library

The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens, known as The Huntington, is a collections-based educational and research institution established by Henry E. Huntington (1850–1927) and Arabella Huntington (c.1851–1924) in San Ma ...

in California between February 12, 2022 and May 30, 2022.

The striking scene has been used as the cover illustration for many books on topics both artistic and scientific. It has even spawned pastiches and parodies: the book cover of ''The Science of Discworld

''The Science of Discworld'' is a 1999 book by novelist Terry Pratchett and popular science writers (and University of Warwick science researchers) Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen. Three sequels, '' The Science of Discworld II: The Globe'', '' The S ...

'', by Terry Pratchett

Sir Terence David John Pratchett (28 April 1948 – 12 March 2015) was an English humourist, satirist, and author of fantasy novels, especially comical works. He is best known for his '' Discworld'' series of 41 novels.

Pratchett's first no ...

, Ian Stewart and Jack Cohen, is a tribute to the painting by artist Paul Kidby

Paul Kidby (born 1964) is an English artist. Many people know him best for his art based on Terry Pratchett's ''Discworld''. He has been included on the sleeve covers since Pratchett's original illustrator, Josh Kirby, died in 2001.Alison Flood ( ...

, who replaces Wright's figures with the book's protagonists. Shelagh Stephenson's play '' An Experiment with an Air Pump'', inspired by the painting, was the joint winner of the 1997 Margaret Ramsay Award and had its premiere at the Royal Exchange Theatre

The Royal Exchange is a grade II listed building in Manchester, England. It is located in the city centre on the land bounded by St Ann's Square, Exchange Street, Market Street, Cross Street and Old Bank Street. The complex includes the Royal ...

, Manchester, in 1998.

Notes

References

* * * * * *Egerton, Judy (1998), National Gallery Catalogues (new series): ''The British School''. catalogue entry pp. 332–343, * * * *Guilding, Ruth, and others, ''William Weddell and the transformation of Newby Hall'', Jeremy Mills Publishing for Leeds Museums and Galleries, 2004, ,Google books

* * * * * * * * * Waterhouse, Ellis, (4th Edn, 1978) ''Painting in Britain, 1530–1790''. Penguin Books (now Yale History of Art series), *

External links

Zoomable version of the painting from the National Gallery, London

{{DEFAULTSORT:Experiment On A Bird In The Air Pump 1768 paintings Science in art Physics experiments Paintings by Joseph Wright of Derby Historical scientific instruments Collections of the National Gallery, London Birds in art