American Ethical Union on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Ethical movement, also referred to as the Ethical Culture movement, Ethical Humanism or simply Ethical Culture, is an

Benny Kraut, Hebrew Union College Press, 1979 Individual chapter organizations are generically referred to as "Ethical Societies", though their names may include "Ethical Society", "Ethical Culture Society", "Society for Ethical Culture", "Ethical Humanist Society", or other variations on the theme of "Ethical". The Ethical movement is an outgrowth of secular moral traditions in the 19th century, principally in Europe and the United States. While some in this movement went on to organize for a secular humanist movement, others attempted to build a secular moral movement that was emphatically "religious" in its approach to developing humanist ethical codes, in the sense of encouraging congregational structures and religious rites and practices. While in the United States, these movements formed as separate education organizations (the

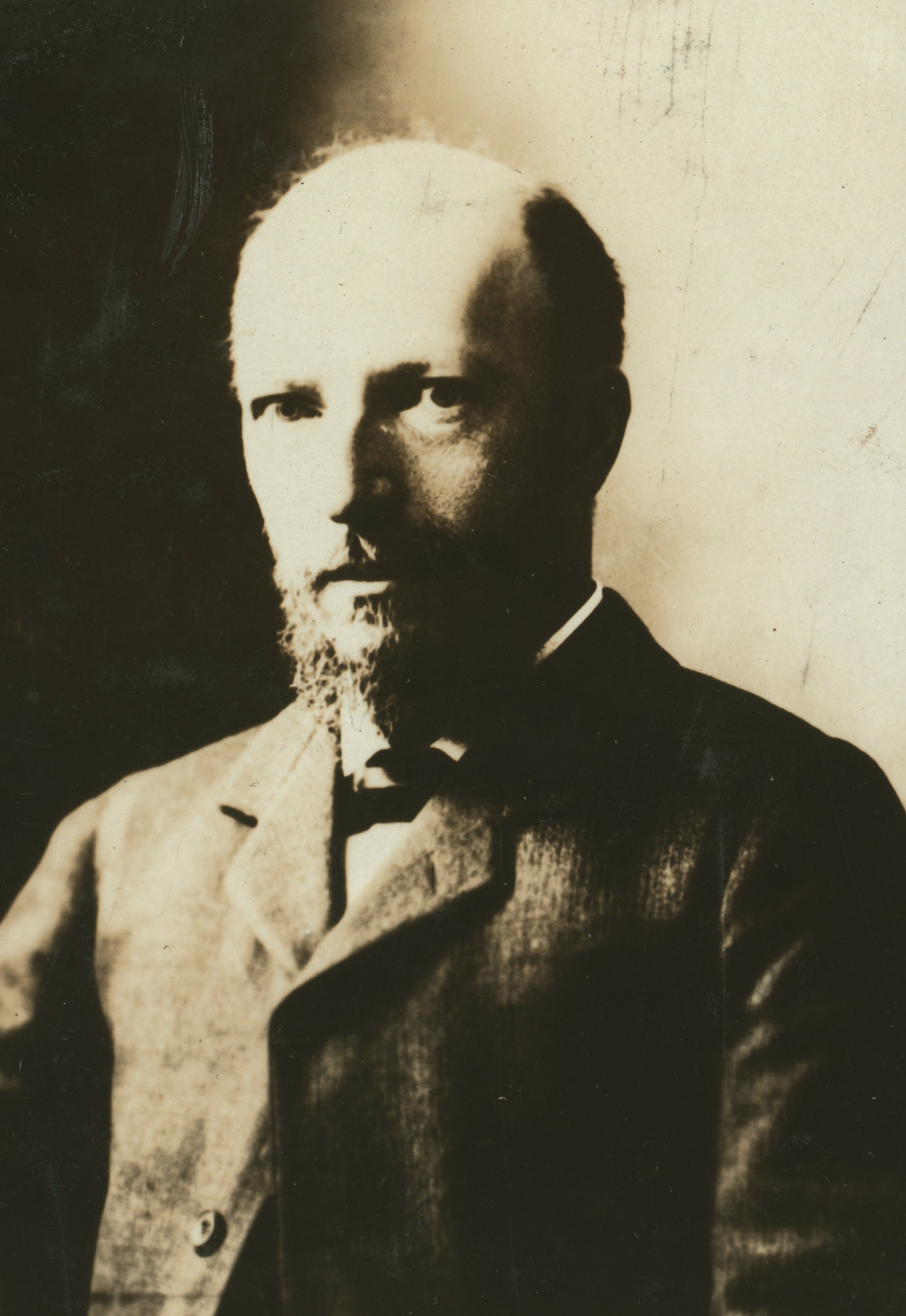

In his youth, Felix Adler was being trained to be a rabbi like his father, Samuel Adler, the rabbi of the

In his youth, Felix Adler was being trained to be a rabbi like his father, Samuel Adler, the rabbi of the  The Adlerian emphasis on "deed not creed" translated into several public service projects. The year after it was founded, the New York society started a kindergarten, a district nursing service and a tenement-house building company. Later they opened the

The Adlerian emphasis on "deed not creed" translated into several public service projects. The year after it was founded, the New York society started a kindergarten, a district nursing service and a tenement-house building company. Later they opened the

In 1885 the ten-year-old American Ethical Culture movement helped to stimulate similar social activity in Great Britain, when American sociologist John Graham Brooks distributed pamphlets by Chicago ethical society leader William Salter to a group of British philosophers, including Bernard Bosanquet,

In 1885 the ten-year-old American Ethical Culture movement helped to stimulate similar social activity in Great Britain, when American sociologist John Graham Brooks distributed pamphlets by Chicago ethical society leader William Salter to a group of British philosophers, including Bernard Bosanquet,

Between 1886 and 1927 seventy-four ethical societies were started in Great Britain, although this rapid growth did not last long. The numbers declined steadily throughout the 1920s and early 30s, until there were only ten societies left in 1934. By 1954 there were only four. The situation became such that in 1971, sociologist Colin Campbell even suggested that one could say, "that when the South Place Ethical Society discussed changing its name to the South Place Humanist society in 1969, the English Ethical movement ceased to exist." The organizations spawned by the 19th century Ethical movement would later live on as the British humanist movement. The South Place Ethical Society eventually changed its name Conway Hall Ethical Society, after

While Ethical Culturists generally share common beliefs about what constitutes ethical behavior and the

While Ethical Culturists generally share common beliefs about what constitutes ethical behavior and the

Horace Traubel, Volume 3, page 31

Functionally, the Ethical Societies were organized in a similar manner to

Functionally, the Ethical Societies were organized in a similar manner to

The Humanist Way: An Introduction to Ethical Humanist Religion

'. A Frederick Ungar book, The Continuum Publishing Company. 205 pages, 1988. * Muzzey, David Saville.

Ethics as a Religion

', 273 pages, 1951, 1967, 1986. * Radest, Howard.

Toward Common Ground: The Story of the Ethical Societies in the United States

'. Ungar, 1969

ethical

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns ma ...

, educational

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty. Vari ...

, and religious

Religion is usually defined as a social system, social-cultural system of designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morality, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sacred site, sanctified places, prophecy, prophecie ...

movement that is usually traced back to Felix Adler (1851–1933).From Reform Judaism to ethical culture: the religious evolution of Felix AdlerBenny Kraut, Hebrew Union College Press, 1979 Individual chapter organizations are generically referred to as "Ethical Societies", though their names may include "Ethical Society", "Ethical Culture Society", "Society for Ethical Culture", "Ethical Humanist Society", or other variations on the theme of "Ethical". The Ethical movement is an outgrowth of secular moral traditions in the 19th century, principally in Europe and the United States. While some in this movement went on to organize for a secular humanist movement, others attempted to build a secular moral movement that was emphatically "religious" in its approach to developing humanist ethical codes, in the sense of encouraging congregational structures and religious rites and practices. While in the United States, these movements formed as separate education organizations (the

American Humanist Association

The American Humanist Association (AHA) is a non-profit organization in the United States that advances secular humanism.

The American Humanist Association was founded in 1941 and currently provides legal assistance to defend the constitutiona ...

and the American Ethical Union

The Ethical movement, also referred to as the Ethical Culture movement, Ethical Humanism or simply Ethical Culture, is an ethical, educational, and religion, religious movement that is usually traced back to Felix Adler (professor), Felix Adler ...

), the American Ethical Union's British equivalents, the South Place Ethical Society

The Conway Hall Ethical Society, formerly the South Place Ethical Society, based in London at Conway Hall, is thought to be the oldest surviving freethought organisation in the world and is the only remaining ethical society in the United King ...

and the British Ethical Union consciously moved away from a congregational model to become Conway Hall

The Conway Hall Ethical Society, formerly the South Place Ethical Society, based in London at Conway Hall, is thought to be the oldest surviving freethought organisation in the world and is the only remaining ethical society in the United King ...

and Humanists UK

Humanists UK, known from 1967 until May 2017 as the British Humanist Association (BHA), is a charitable organisation which promotes secular humanism and aims to represent "people who seek to live good lives without religious or superstitious be ...

respectively. Subsequent "godless" congregational movements include the Sunday Assembly

Sunday Assembly is a non-religious gathering co-founded by Sanderson Jones and Pippa Evans in January 2013 in London, England. The gathering is mostly for non-religious people who want a similar communal experience to a religious church, thoug ...

, whose London chapter has used Conway Hall as a venue since 2013.

At the international level, Ethical Culture and secular humanist groups have always organized jointly; the American Ethical Union and British Ethical Union were founding members of Humanists International

Humanists International (known as the International Humanist and Ethical Union, or IHEU, from 1952–2019) is an international non-governmental organisation championing secularism and human rights, motivated by secular humanist values. Found ...

, whose original name "International Humanist and Ethical Union" reflected the movement's unity.

Ethical Culture is premised on the idea that honoring and living in accordance with ''ethical principles'' is central to what it takes to live meaningful and fulfilling lives, and to creating a world that is good for all. Practitioners of Ethical Culture focus on supporting one another in becoming better people, and on doing good in the world.

History

Background

The Ethical movement was an outgrowth of the general loss of faith among the intellectuals of theVictorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

. A precursor to the doctrines of the Ethical movement can be found in the South Place Ethical Society

The Conway Hall Ethical Society, formerly the South Place Ethical Society, based in London at Conway Hall, is thought to be the oldest surviving freethought organisation in the world and is the only remaining ethical society in the United King ...

, founded in 1793 as the South Place Chapel

The Conway Hall Ethical Society, formerly the South Place Ethical Society, based in London at Conway Hall, is thought to be the oldest surviving freethought organisation in the world and is the only remaining ethical society in the United King ...

on Finsbury Square

Finsbury Square is a square in Finsbury in central London which includes a six-rink grass bowling green. It was developed in 1777 on the site of a previous area of green space to the north of the City of London known as Finsbury Fields, in the pa ...

, on the edge of the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

.

In the early nineteenth century, the chapel became known as "a radical gathering-place". At that point it was a Unitarian chapel, and that movement, like Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

, supported female equality. Under the leadership of Reverend William Johnson Fox

William Johnson Fox (1 March 1786 – 3 June 1864) was an English Unitarian minister, politician, and political orator.

Early life

Fox was born at Uggeshall Farm, Wrentham, near Southwold, Suffolk on 1 March 1786. His parents were strict Calvi ...

(who became minister of the congregation in 1817), it lent its pulpit to activists such as Anna Wheeler, one of the first women to campaign for feminism at public meetings in England, who spoke in 1829 on "Rights of Women." In later decades, the chapel moved away from Unitarianism, changing its name first to the South Place Religious Society, then the South Place Ethical Society (a name it held formally, though it was better known as Conway Hall from 1929) and is now Conway Hall Ethical Society

The Conway Hall Ethical Society, formerly the South Place Ethical Society, based in London at Conway Hall, is thought to be the oldest surviving freethought organisation in the world and is the only remaining ethical society in the United Kin ...

.

The Fellowship of the New Life

The Fellowship of the New Life was a British organisation in the 19th century, most famous for a splinter group, the Fabian Society.

It was founded in 1883, by the Scottish intellectual Thomas Davidson. Fellowship members included the poet Edwa ...

was established in 1883 by the Scottish intellectual Thomas Davidson. Fellowship members included poets Edward Carpenter

Edward Carpenter (29 August 1844 – 28 June 1929) was an English utopian socialist, poet, philosopher, anthologist, an early activist for gay rightsWarren Allen Smith: ''Who's Who in Hell, A Handbook and International Directory for Human ...

and John Davidson, animal rights activist Henry Stephens Salt

Henry Shakespear Stephens Salt (; 20 September 1851 – 19 April 1939) was an English writer and campaigner for social reform in the fields of prisons, schools, economic institutions, and the treatment of animals. He was a noted ethical vegeta ...

, sexologist Havelock Ellis

Henry Havelock Ellis (2 February 1859 – 8 July 1939) was an English physician, eugenicist, writer, progressive intellectual and social reformer who studied human sexuality. He co-wrote the first medical textbook in English on homosexuality in ...

, feminist Edith Lees

Edith Mary Oldham Ellis (née Lees; 9 March 1861 – 14 September 1916) was an English writer and women's rights activist. She was married to the early sexologist Havelock Ellis.

Biography

Ellis was born on 9 March 1861 in Newton, Lancashi ...

(who later married Ellis), novelist Olive Schreiner

Olive Schreiner (24 March 1855 – 11 December 1920) was a South African author, pacifist, anti-war campaigner and intellectual. She is best remembered today for her novel ''The Story of an African Farm'' (1883), which has been highly acclaimed ...

and Edward R. Pease

Edward Reynolds Pease (23 December 1857 – 5 January 1955) was an English writer and a founding member of the Fabian Society.

Early life

Pease was born near Bristol, the son of devout Quakers, Thomas Pease (1816–1884) and Susanna Ann Fr ...

.

Its objective was "The cultivation of a perfect character in each and all." They wanted to transform society by setting an example of clean simplified living for others to follow. Davidson was a major proponent of a structured philosophy about religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatural, ...

, ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns m ...

, and social reform

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary move ...

.

At a meeting on 16 November 1883, a summary of the society's goals was drawn up by Maurice Adams:

Although the Fellowship was a short-lived organization, it spawned the Fabian Society

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation whose purpose is to advance the principles of social democracy and democratic socialism via gradualist and reformist effort in democracies, rather than by revolutionary overthrow. The Fa ...

, which split in 1884 from the Fellowship of the New Life.William A. Knight, ''Memorials of Thomas Davidson: The Wandering Scholar'' (Boston and London: Ginn and Co, 1907). p. 16, 19, 46.

In the United States

In his youth, Felix Adler was being trained to be a rabbi like his father, Samuel Adler, the rabbi of the

In his youth, Felix Adler was being trained to be a rabbi like his father, Samuel Adler, the rabbi of the Reform Jewish

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major Jewish denomination that emphasizes the evolving nature of Judaism, the superiority of its ethical aspects to its ceremonial ones, and belief in a continuous searc ...

Temple Emanu-El in New York. As part of his education, he enrolled at the University of Heidelberg

}

Heidelberg University, officially the Ruprecht Karl University of Heidelberg, (german: Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg; la, Universitas Ruperto Carola Heidelbergensis) is a public research university in Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg, ...

, where he was influenced by neo-Kantian

In late modern continental philosophy, neo-Kantianism (german: Neukantianismus) was a revival of the 18th-century philosophy of Immanuel Kant. The Neo-Kantians sought to develop and clarify Kant's theories, particularly his concept of the "thin ...

philosophy. He was especially drawn to the Kantian ideas that one could not prove the existence or non-existence of deities or immortality and that morality could be established independently of theology.Howard B. Radest. 1969. ''Toward Common Ground: The Story of the Ethical Societies in the United States.'' New York: Fredrick Unger Publishing Co.

During this time he was also exposed to the moral problems caused by the exploitation

Exploitation may refer to:

*Exploitation of natural resources

*Exploitation of labour

** Forced labour

*Exploitation colonialism

*Slavery

** Sexual slavery and other forms

*Oppression

*Psychological manipulation

In arts and entertainment

*Exploi ...

of women and labor. These experiences laid the intellectual groundwork for the Ethical movement. Upon his return from Germany, in 1873, he shared his ethical vision with his father's congregation in the form of a sermon. Due to the negative reaction he elicited it became his first and last sermon as a rabbi in training.Colin Campbell. 1971. ''Towards a Sociology of Irreligion.'' London: MacMillan Press. Instead he took up a professorship at Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach an ...

and in 1876 gave a follow up sermon that led to the 1877 founding of the New York Society for Ethical Culture, which was the first of its kind. By 1886, similar societies had sprouted up in Philadelphia, Chicago and St. Louis.

These societies all adopted the same statement of principles:

*The belief that morality is independent of theology;

*The affirmation that new moral problems have arisen in modern industrial society which have not been adequately dealt with by the world's religions;

*The duty to engage in philanthropy in the advancement of morality;

*The belief that self-reform should go in lock step with social reform;

*The establishment of republican rather than monarchical governance of Ethical societies

*The agreement that educating the young is the most important aim.

In effect, the movement responded to the religious crisis of the time by replacing theology with unadulterated morality. It aimed to "disentangle moral ideas from religious doctrines

Doctrine (from la, Wikt:doctrina, doctrina, meaning "teaching, instruction") is a codification (law), codification of beliefs or a body of teacher, teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given ...

, metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

systems, and ethical theories, and to make them an independent force in personal life and social relations." Adler was also particularly critical of the religious emphasis on creed

A creed, also known as a confession of faith, a symbol, or a statement of faith, is a statement of the shared beliefs of a community (often a religious community) in a form which is structured by subjects which summarize its core tenets.

The ea ...

, believing it to be the source of sectarian

Sectarianism is a political or cultural conflict between two groups which are often related to the form of government which they live under. Prejudice, discrimination, or hatred can arise in these conflicts, depending on the political status quo ...

bigotry

Discrimination is the act of making unjustified distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong. People may be discriminated on the basis of race, gender, age, relig ...

. He therefore attempted to provide a universal fellowship devoid of ritual and ceremony, for those who would otherwise be divided by creeds. For the same reasons the movement also adopted a neutral position on religious beliefs, advocating neither atheism

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no d ...

nor theism

Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of a supreme being or deities. In common parlance, or when contrasted with ''deism'', the term often describes the classical conception of God that is found in monotheism (also referred to ...

, agnosticism

Agnosticism is the view or belief that the existence of God, of the divine or the supernatural is unknown or unknowable. (page 56 in 1967 edition) Another definition provided is the view that "human reason is incapable of providing sufficient ...

nor deism

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin ''deus'', meaning "god") is the Philosophy, philosophical position and Rationalism, rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge, and asserts that Empirical evi ...

.

The Adlerian emphasis on "deed not creed" translated into several public service projects. The year after it was founded, the New York society started a kindergarten, a district nursing service and a tenement-house building company. Later they opened the

The Adlerian emphasis on "deed not creed" translated into several public service projects. The year after it was founded, the New York society started a kindergarten, a district nursing service and a tenement-house building company. Later they opened the Ethical Culture School

Ethical Culture Fieldston School (ECFS), also referred to as Fieldston, is a private independent school in New York City. The school is a member of the Ivy Preparatory School League. The school serves approximately 1,700 students with 480 facul ...

, then called the "Workingman's School," a Sunday school and a summer home for children, and other Ethical societies soon followed suit with similar projects. Unlike the philanthropic efforts of the established religious institutions of the time, the Ethical societies did not attempt to proselytize those they helped. In fact, they rarely attempted to convert anyone. New members had to be sponsored by existing members, and women were not allowed to join at all until 1893. They also resisted formalization, though nevertheless slowly adopted certain traditional practices, like Sunday meetings and life cycle ceremonies, yet did so in a modern humanistic context. In 1893, the four existing societies unified under the umbrella organization, the American Ethical Union (AEU).

After some initial success the movement stagnated until after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. In 1946 efforts were made to revitalize and societies were created in New Jersey and Washington D.C., along with the inauguration of the Encampment for Citizenship

The Encampment for Citizenship (EFC) is a non-profit, non-partisan, non-sectarian organization currently based in California that conducts a residential summer programs with year-round follow-up for young people of widely diverse backgrounds and na ...

. By 1968 there were thirty societies with a total national membership of over 5,500. However, the resuscitated movement differed from its predecessor in a few ways. The newer groups were being created in suburban locales and often to provide alternative Sunday schools

A Sunday school is an educational institution, usually (but not always) Christian in character. Other religions including Buddhism, Islam, and Judaism have also organised Sunday schools in their temples and mosques, particularly in the West.

Su ...

for children, with adult activities as an afterthought.

There was also a greater focus on organization and bureaucracy, along with an inward turn emphasizing the needs of the group members over the more general social issues that had originally concerned Adler. The result was a transformation of American ethical societies into something much more akin to small Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

congregations in which the minister's most pressing concern is to tend to his or her flock.

In the 21st century, the movement continued to revitalize itself through social media and involvement with other Humanist organizations, with mixed success. As of 2014, there were fewer than 10,000 official members of the Ethical movement.Stedman, Chris (1 October 2014). "The original 'atheist church': Why don’t more atheists know about Ethical Culture?" Religion World News. Retrieved from https://religionnews.com/2014/10/01/original-atheist-church-dont-atheists-know-ethical-culture/

In Britain

In 1885 the ten-year-old American Ethical Culture movement helped to stimulate similar social activity in Great Britain, when American sociologist John Graham Brooks distributed pamphlets by Chicago ethical society leader William Salter to a group of British philosophers, including Bernard Bosanquet,

In 1885 the ten-year-old American Ethical Culture movement helped to stimulate similar social activity in Great Britain, when American sociologist John Graham Brooks distributed pamphlets by Chicago ethical society leader William Salter to a group of British philosophers, including Bernard Bosanquet, John Henry Muirhead

John Henry Muirhead (28 April 1855 – 24 May 1940) was a British philosopher best known for having initiated the Muirhead Library of Philosophy in 1890. He became the first person named to the Chair of Philosophy at the University of Birmingham ...

, and John Stuart MacKenzie.

One of Felix Adler's colleagues, Stanton Coit Stanton may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

;Populated places

* Stanton, Derbyshire, near Swadlincote

* Stanton, Gloucestershire

* Stanton, Northumberland

* Stanton, Staffordshire

* Stanton, Suffolk

* New Stanton, Derbyshire

* Stanton by B ...

, visited them in London to discuss the "aims and principles" of their American counterparts. In 1886 the first British ethical society was founded. Coit took over the leadership of South Place for a few years. Ethical societies flourished in Britain. By 1896 the four London societies formed the Union of Ethical Societies, and between 1905 and 1910 there were over fifty societies in Great Britain, seventeen of which were affiliated with the Union. Part of this rapid growth was due to Coit, who left his role as leader of South Place in 1892 after being denied the power and authority he was vying for.

Because he was firmly entrenched in British ethicism, Coit remained in London and formed the West London Ethical Society, which was almost completely under his control. Coit worked quickly to shape the West London society not only around Ethical Culture but also the trappings of religious practice, renaming the society in 1914 to the Ethical Church; he did this because he subscribed to a personal theory of using "theological terms in a humanistic sense" in order to make the Ethical movement appealing to irreligious people with otherwise strong cultural attachments to religion, such as cultural Christians

Cultural Christians are nonreligious persons who adhere to Christian values and appreciate Christian culture. As such, these individuals usually identify themselves as culturally Christians, and are often seen by practicing believers as nomina ...

. Coit transformed his meetings into "services", and their space into something akin to a church. In a series of books Coit also began to argue for the transformation of the Anglican Church

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the ...

into an Ethical Church, while holding up the virtue of ethical ritual. He felt that the Anglican Church was in the unique position to harness the natural moral impulse that stemmed from society itself, as long as the Church replaced theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

with science, abandoned supernatural beliefs, expanded its bible to include a cross-cultural selection of ethical literature and reinterpreted its creeds and liturgy in light of modern ethics and psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Psychology includes the study of conscious and unconscious phenomena, including feelings and thoughts. It is an academic discipline of immense scope, crossing the boundaries betwe ...

. His attempt to reform the Anglican church failed, and ten years after his death in 1944, the Ethical Church building was sold to the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

.

During Stanton Coit's lifetime, the Ethical Church never officially affiliated with the Union of Ethical Societies, nor did South Place. In 1920 the Union of Ethical Societies changed its name to the Ethical Union.I.D. MacKillop. 1986. ''The British Ethical Societies''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Harold Blackham

Harold John Blackham (31 March 1903 – 23 January 2009) was a leading British humanist philosopher, writer and educationalist. He has been described as the "progenitor of modern humanism in Britain".

Biography

Blackham was born in West Br ...

, who had taken over leadership of the London Ethical Church, consciously sought to remove the church-like trappings of the Ethical movement, and advocated a simple creed of humanism that was not akin to a religion. He promoted the merger of the Ethical Union with the Rationalist Press Association

The Rationalist Association, originally the Rationalist Press Association, is an organization in the United Kingdom, founded in 1885 by a group of freethinkers who were unhappy with the increasingly political and decreasingly intellectual tenor ...

and the South Place Ethical Society, and, in 1957, a Humanist Council was set up to explore amalgamation. Although issues over charitable status prevented a full amalgamation, the Ethical Union under Blackham changed its name in 1967 to become the British Humanist Association

Humanists UK, known from 1967 until May 2017 as the British Humanist Association (BHA), is a charitable organisation which promotes secular humanism and aims to represent "people who seek to live good lives without religious or superstitious b ...

– establishing humanism as the principle organizing force for non-religious morals and secularist advocacy in Britain. The BHA was the legal successor body to the Union of Ethical Societies.British Humanist Association: Our History since 1896Between 1886 and 1927 seventy-four ethical societies were started in Great Britain, although this rapid growth did not last long. The numbers declined steadily throughout the 1920s and early 30s, until there were only ten societies left in 1934. By 1954 there were only four. The situation became such that in 1971, sociologist Colin Campbell even suggested that one could say, "that when the South Place Ethical Society discussed changing its name to the South Place Humanist society in 1969, the English Ethical movement ceased to exist." The organizations spawned by the 19th century Ethical movement would later live on as the British humanist movement. The South Place Ethical Society eventually changed its name Conway Hall Ethical Society, after

Moncure D. Conway

Moncure Daniel Conway (March 17, 1832 – November 15, 1907) was an American abolitionist minister and radical writer. At various times Methodist, Unitarian, and a Freethinker, he descended from patriotic and patrician families of Virginia and ...

, and is typically known as simply "Conway Hall". In 2017, the British Humanist Association again changed its name, becoming Humanists UK

Humanists UK, known from 1967 until May 2017 as the British Humanist Association (BHA), is a charitable organisation which promotes secular humanism and aims to represent "people who seek to live good lives without religious or superstitious be ...

. Both organizations are part of Humanists International

Humanists International (known as the International Humanist and Ethical Union, or IHEU, from 1952–2019) is an international non-governmental organisation championing secularism and human rights, motivated by secular humanist values. Found ...

, which had been founded by Harold Blackham in 1952 as the International Humanist and Ethical Union.

Ethical perspective

While Ethical Culturists generally share common beliefs about what constitutes ethical behavior and the

While Ethical Culturists generally share common beliefs about what constitutes ethical behavior and the good

In most contexts, the concept of good denotes the conduct that should be preferred when posed with a choice between possible actions. Good is generally considered to be the opposite of evil and is of interest in the study of ethics, morality, ph ...

, individuals are encouraged to develop their own personal understanding of these ideas. This does not mean that Ethical Culturists condone moral relativism

Moral relativism or ethical relativism (often reformulated as relativist ethics or relativist morality) is used to describe several philosophical positions concerned with the differences in moral judgments across different peoples and cultures. ...

, which would relegate ethics to mere preferences or social conventions. Ethical principles are viewed as being related to deep truths about the way the world works, and hence not arbitrary. However, it is recognized that complexities render the understanding of ethical nuances subject to continued dialogue

Dialogue (sometimes spelled dialog in American English) is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literary and theatrical form that depicts such an exchange. As a philosophical or didactic device, it is c ...

, exploration, and learning.

While the founder of Ethical Culture, Felix Adler, was a transcendentalist, Ethical Culturists may have a variety of understandings as to the theoretical origins of ethics. Key to the founding of Ethical Culture was the observation that too often disputes over religious or philosophical doctrine

Doctrine (from la, doctrina, meaning "teaching, instruction") is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given branch of knowledge or in a belief system ...

s have distracted people from actually living ethically and doing good. Consequently, ''"Deed before creed

A creed, also known as a confession of faith, a symbol, or a statement of faith, is a statement of the shared beliefs of a community (often a religious community) in a form which is structured by subjects which summarize its core tenets.

The ea ...

"'' has long been a motto

A motto (derived from the Latin , 'mutter', by way of Italian , 'word' or 'sentence') is a sentence or phrase expressing a belief or purpose, or the general motivation or intention of an individual, family, social group, or organisation. Mot ...

of the movement.The conservator, Volumes 3-4Horace Traubel, Volume 3, page 31

Organizational model

Functionally, the Ethical Societies were organized in a similar manner to

Functionally, the Ethical Societies were organized in a similar manner to church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* Chris ...

es or synagogue

A synagogue, ', 'house of assembly', or ', "house of prayer"; Yiddish: ''shul'', Ladino: or ' (from synagogue); or ', "community". sometimes referred to as shul, and interchangeably used with the word temple, is a Jewish house of worshi ...

s and are headed by "leaders" as clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

. Their founders had suspected this would be a successful model for spreading secular morality. As a result, an Ethical Society typically would have Sunday morning meetings, offer moral instruction for children and teens, and do charitable work and social action. They may offer a variety of educational and other programs. They conduct wedding

A wedding is a ceremony where two people are united in marriage. Wedding traditions and customs vary greatly between cultures, ethnic groups, religions, countries, and social classes. Most wedding ceremonies involve an exchange of marriage vo ...

s, commitment ceremonies

A wedding is a ceremony where two people are united in marriage. Wedding traditions and customs vary greatly between cultures, ethnic groups, religions, countries, and social classes. Most wedding ceremonies involve an exchange of marriage vo ...

, baby namings, and memorial service

A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect th ...

s.

Individual Ethical Society members may or may not believe in a deity

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greate ...

or regard Ethical Culture as their religion. Felix Adler said "Ethical Culture is religious to those who are religiously minded, and merely ethical to those who are not so minded." The movement does consider itself a religion in the sense that

The Ethical Culture 2003 ethical identity statement states:

Since around 1950 the Ethical Culture movement has been increasingly identified as part of the modern Humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humani ...

movement. Specifically, in 1952, the American Ethical Union

The Ethical movement, also referred to as the Ethical Culture movement, Ethical Humanism or simply Ethical Culture, is an ethical, educational, and religion, religious movement that is usually traced back to Felix Adler (professor), Felix Adler ...

, the national umbrella organization for Ethical Culture societies in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, became one of the founding member organizations of the International Humanist and Ethical Union

Humanists International (known as the International Humanist and Ethical Union, or IHEU, from 1952–2019) is an international non-governmental organisation championing secularism and human rights, motivated by secular humanist values. Found ...

.

In the United Kingdom, the ethical societies consciously rejected the "church model" in the mid-20th century, while still providing services like weddings, funerals, and namings on a secular basis.

Key ideas

While Ethical Culture does not regard its founder's views as necessarily the final word, Adler identified focal ideas that remain important within Ethical Culture. These ideas include: * ''Human Worth and Uniqueness'' – All people are taken to have inherent worth, not dependent on the value of what they do. They are deserving of respect and dignity, and their unique gifts are to be encouraged and celebrated. * ''Eliciting the Best'' – "Always act so as to Elicit the best in others, and thereby yourself" is as close as Ethical Culture comes to having a Golden Rule. * ''Inter-relatedness'' – Adler used the term ''The Ethical Manifold'' to refer to his conception of the universe as made up of myriad unique and indispensable moral agents (individual human beings), each of whom has an inestimable influence on all the others. In other words, we are all interrelated, with each person playing a role in the whole and the whole affecting each person. Our Inter-relatedness is at the heart of ethics. Many Ethical Societies prominently display a sign that says "The Place Where People Meet to Seek the Highest is Holy Ground".Locations

The largest concentration of Ethical Societies is in theNew York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

metropolitan area, including Societies in New York, Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

, the Bronx, Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, Queens, Westchester and Nassau County; and New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

, such as Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipality in Vestland county on the west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the second-largest city in Norway. The municipality covers and is on the peninsula of ...

and Essex Counties, New Jersey.

Ethical Societies exist in several U.S. cities and counties, including Austin, Texas

Austin is the capital city of the U.S. state of Texas, as well as the county seat, seat and largest city of Travis County, Texas, Travis County, with portions extending into Hays County, Texas, Hays and Williamson County, Texas, Williamson co ...

; Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

; Chapel Hill Chapel Hill or Chapelhill may refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Chapel Hill (Antarctica) Australia

*Chapel Hill, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane

*Chapel Hill, South Australia, in the Mount Barker council area

Canada

* Chapel Hill, Ottawa, a neighbo ...

; Asheville, North Carolina

Asheville ( ) is a city in, and the county seat of, Buncombe County, North Carolina. Located at the confluence of the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers, it is the largest city in Western North Carolina, and the state's 11th-most populous cit ...

; Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

; San Jose, California

San Jose, officially San José (; ; ), is a major city in the U.S. state of California that is the cultural, financial, and political center of Silicon Valley and largest city in Northern California by both population and area. With a 2020 popul ...

; Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

; St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

; St. Peters, Missouri

St. Peters is a city in St. Charles County, Missouri, United States. The 2010 census showed the city's population to be 52,575, tied for 10th place in Missouri with Blue Springs.

Interstate 70 passes through the city, providing a major transp ...

; Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

; Lewisburg, Pennsylvania

Lewisburg is a borough in Union County, Pennsylvania, United States, south by southeast of Williamsport and north of Harrisburg. In the past, it was the commercial center for a fertile grain and general farming region. The population was 5,1 ...

, and Vienna, Virginia

Vienna () is a town in Fairfax County, Virginia, United States. As of the 2020 U.S. census, Vienna has a population of 16,473. Significantly more people live in ZIP codes with the Vienna postal addresses (22180, 22181, and 22182), bordered approx ...

.

Ethical Societies also exist outside the U.S. Conway Hall in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

is home to the South Place Ethical Society

The Conway Hall Ethical Society, formerly the South Place Ethical Society, based in London at Conway Hall, is thought to be the oldest surviving freethought organisation in the world and is the only remaining ethical society in the United King ...

, which was founded in 1787.

Structure and events

Ethical societies are typically led by "Leaders". Leaders are trained and certified (the equivalent of ordination) by the American Ethical Union. Societies engage Leaders, in much the same way that Protestant congregations "call" a minister. Not all Ethical societies have a professional Leader. (In typical usage, the Ethical movement uses upper case to distinguish certified professional Leaders from other leaders.) A board of executives handles day-to-day affairs, and committees of members focus on specific activities and involvements of the society. Ethical societies usually hold weekly meetings on Sundays, with the main event of each meeting being the "Platform", which involves a half-hour speech by the Leader of the Ethical Society, a member of the society or by guests.Sunday school

A Sunday school is an educational institution, usually (but not always) Christian in character. Other religions including Buddhism, Islam, and Judaism have also organised Sunday schools in their temples and mosques, particularly in the West.

Su ...

for minors is also held at most ethical societies concurrent with the Platform.

The American Ethical Union holds an annual AEU Assembly bringing together Ethical societies from across the US.

Legal challenges

The tax status of Ethical Societies as religious organizations has been upheld in court cases in Washington, D.C. (1957), and in Austin, Texas (2003). In challenge to a denial of tax-exempt status, the Texas State Appeals Court decided that "the Comptroller's test was unconstitutionally underinclusive and that the Ethical Society should have qualified for the requested tax exemptions... Because the Comptroller's test fails to include the whole range of belief systems that may, in our diverse and pluralistic society, merit the First Amendment's protection..."Advocates

British Prime MinisterRamsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, the first who belonged to the Labour Party, leading minority Labour governments for nine months in 1924 ...

was a strong supporter of the British Ethical movement, having been a Christian earlier in his life. He was a member of the Ethical Church and the Union of Ethical Societies (now Humanists UK

Humanists UK, known from 1967 until May 2017 as the British Humanist Association (BHA), is a charitable organisation which promotes secular humanism and aims to represent "people who seek to live good lives without religious or superstitious be ...

), a regular attender at South Place Ethical Society

The Conway Hall Ethical Society, formerly the South Place Ethical Society, based in London at Conway Hall, is thought to be the oldest surviving freethought organisation in the world and is the only remaining ethical society in the United King ...

. During his time involved with the Ethical movement, he chaired the annual meeting of the Ethical Union on multiple occasions and wrote for Stanton Coit Stanton may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

;Populated places

* Stanton, Derbyshire, near Swadlincote

* Stanton, Gloucestershire

* Stanton, Northumberland

* Stanton, Staffordshire

* Stanton, Suffolk

* New Stanton, Derbyshire

* Stanton by B ...

's ''Ethical World'' journal.

The British critic and mountaineer Leslie Stephen

Sir Leslie Stephen (28 November 1832 – 22 February 1904) was an English author, critic, historian, biographer, and mountaineer, and the father of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell.

Life

Sir Leslie Stephen came from a distinguished intellectua ...

was a prominent supporter of Ethical Culture in the UK, serving multiple terms as President of the West London Ethical Society, and was involved in the creation of the Union of Ethical Societies.

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

was a supporter of Ethical Culture. On the seventy-fifth anniversary of the New York Society for Ethical Culture, in 1951, he noted that the idea of Ethical Culture embodied his personal conception of what is most valuable and enduring in religious idealism. Humanity requires such a belief to survive, Einstein argued. He observed, "Without 'ethical culture' there is no salvation for humanity."

First Lady

First lady is an unofficial title usually used for the wife, and occasionally used for the daughter or other female relative, of a non-monarchical

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state fo ...

Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

was a regular attendee at the New York Society for Ethical Culture at a time when humanism was beginning to coalesce in its modern-day form, and it was there that she developed friendships with the leading humanists and Ethical Culturists of her day. She collaborated with Al Black, Ethical Society leader, in the creation of her nationwide Encampment of Citizenship. She maintained her involvement with the movement as figures on both sides of the Atlantic began to advocate for organizing under the banner of secular humanism

Secular humanism is a philosophy, belief system or life stance that embraces human reason, secular ethics, and philosophical naturalism while specifically rejecting religious dogma, supernaturalism, and superstition as the basis of morality an ...

. She provided a cover endorsement for the first edition of ''Humanism as the Next Step'' (1954) by Lloyd and Mary Morain, saying simply that it was "A significant book."

See also

*Arthur E. Briggs

Arthur Elbert Briggs (April 26, 1881 – July 25, 1969) was a teacher and law school dean who was a Los Angeles City Council member from 1939 to 1941 and the leader of the Ethical Society of Los Angeles in 1953.

Biography

Briggs was born on Ap ...

, Los Angeles City Council member, 1939–41, Ethical Society leader

* British Humanist Association

Humanists UK, known from 1967 until May 2017 as the British Humanist Association (BHA), is a charitable organisation which promotes secular humanism and aims to represent "people who seek to live good lives without religious or superstitious b ...

, which inherited many British ethical societies

* International Moral Education Congress

The International Moral Education Congress was an international academic conference held in Europe six times between 1908 and 1934. It convened because of an interest in moral education by many countries beginning a decade before the inaugural eve ...

* Religious humanism

* Unitarian Universalism

Unitarian Universalism (UU) is a liberal religion characterized by a "free and responsible search for truth and meaning". Unitarian Universalists assert no creed, but instead are unified by their shared search for spiritual growth, guided by a ...

* ''Washington Ethical Society v. District of Columbia

''Washington Ethical Society v. District of Columbia'', 249 F.2d 127 (1957), was a case of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. The Washington Ethical Society functions much like a church, but regards itself as ...

''

References

Sources

*Further reading

* Ericson, Edward L.The Humanist Way: An Introduction to Ethical Humanist Religion

'. A Frederick Ungar book, The Continuum Publishing Company. 205 pages, 1988. * Muzzey, David Saville.

Ethics as a Religion

', 273 pages, 1951, 1967, 1986. * Radest, Howard.

Toward Common Ground: The Story of the Ethical Societies in the United States

'. Ungar, 1969

External links

* {{Authority Control 1877 establishments in the United States Ethics Humanism Nontheism Philosophical movements