Alec Douglas-Home, 14th Earl Of Home on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

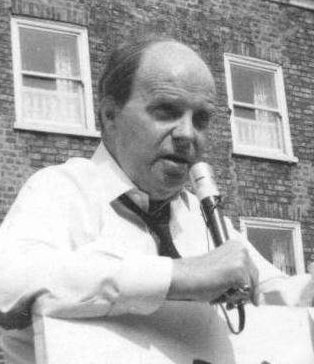

Alexander Frederick Douglas-Home, Baron Home of the Hirsel (; 2 July 1903 – 9 October 1995), styled as Lord Dunglass between 1918 and 1951 and being The 14th Earl of Home from 1951 till 1963, was a British Conservative politician who served as

CricInfo, accessed 13 April 2012 Dunglass began serving in the Territorial Army in 1924 as a

"Home, Alexander Frederick Douglas-, fourteenth earl of Home and Baron Home of the Hirsel (1903–1995)"

''

In July 1951 the 13th earl died. Dunglass succeeded him, inheriting the title of Earl of Home together with the extensive family estates, including the Hirsel, the Douglas-Homes' principal residence. The new Lord Home took his seat in the Lords; a by-election was called to appoint a new MP for Lanark, but it was still pending when Attlee called another general election in October 1951. The Unionists held Lanark, and the national result gave the Conservatives under Churchill a small but working majority of seventeen.

Home was appointed to the new post of Minister of State at the Scottish Office, a middle-ranking position, senior to Under-secretary but junior to James Stuart, the Secretary of State, who was a member of the cabinet. Stuart, previously an influential chief whip, was a confidant of Churchill, and possibly the most powerful Scottish Secretary in any government. Thorpe writes that Home owed his appointment to Stuart's advocacy rather than to any great enthusiasm on the Prime Minister's part (Churchill referred to him as "Home sweet Home").Thorpe (1997), p. 141 In addition to his ministerial position Home was appointed to membership of the

In July 1951 the 13th earl died. Dunglass succeeded him, inheriting the title of Earl of Home together with the extensive family estates, including the Hirsel, the Douglas-Homes' principal residence. The new Lord Home took his seat in the Lords; a by-election was called to appoint a new MP for Lanark, but it was still pending when Attlee called another general election in October 1951. The Unionists held Lanark, and the national result gave the Conservatives under Churchill a small but working majority of seventeen.

Home was appointed to the new post of Minister of State at the Scottish Office, a middle-ranking position, senior to Under-secretary but junior to James Stuart, the Secretary of State, who was a member of the cabinet. Stuart, previously an influential chief whip, was a confidant of Churchill, and possibly the most powerful Scottish Secretary in any government. Thorpe writes that Home owed his appointment to Stuart's advocacy rather than to any great enthusiasm on the Prime Minister's part (Churchill referred to him as "Home sweet Home").Thorpe (1997), p. 141 In addition to his ministerial position Home was appointed to membership of the  Throughout Churchill's second term as Prime Minister (1951–55) Home remained at the Scottish Office, although both Eden at the Foreign Office and Lord Salisbury at the Commonwealth Relations Office invited him to join their ministerial teams. Among the Scottish matters with which he dealt were hydro-electric projects, hill farming, sea transport, road transport, forestry, and the welfare of crofters in the Highlands and the Western Isles. These matters went largely unreported in the British press, but the question of the royal cypher on Post Office pillar boxes became front-page news. Because

Throughout Churchill's second term as Prime Minister (1951–55) Home remained at the Scottish Office, although both Eden at the Foreign Office and Lord Salisbury at the Commonwealth Relations Office invited him to join their ministerial teams. Among the Scottish matters with which he dealt were hydro-electric projects, hill farming, sea transport, road transport, forestry, and the welfare of crofters in the Highlands and the Western Isles. These matters went largely unreported in the British press, but the question of the royal cypher on Post Office pillar boxes became front-page news. Because

Home was generally warmly regarded by colleagues and opponents alike, and there were few politicians who did not respond well to him. One was Attlee, but as their political primes did not overlap this was of minor consequence. More important was Iain Macleod's prickly relationship with Home. Macleod, Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1959–61, was, like Butler, on the liberal wing of the Conservative party; he was convinced, as Home was not, that Britain's colonies in Africa should have majority rule and independence as quickly as possible. Their spheres of influence overlapped in the Central African Federation.

Macleod wished to push ahead with majority rule and independence; Home believed in a more gradual approach to independence, accommodating both white minority and black majority opinions and interests. Macleod disagreed with those who warned that precipitate independence would lead the newly independent nations into "trouble, strife, poverty, dictatorship" and other evils. His reply was, "Would you want the Romans to have stayed on in Britain?"Frankel, P H. "Iain Macleod", ''

Home was generally warmly regarded by colleagues and opponents alike, and there were few politicians who did not respond well to him. One was Attlee, but as their political primes did not overlap this was of minor consequence. More important was Iain Macleod's prickly relationship with Home. Macleod, Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1959–61, was, like Butler, on the liberal wing of the Conservative party; he was convinced, as Home was not, that Britain's colonies in Africa should have majority rule and independence as quickly as possible. Their spheres of influence overlapped in the Central African Federation.

Macleod wished to push ahead with majority rule and independence; Home believed in a more gradual approach to independence, accommodating both white minority and black majority opinions and interests. Macleod disagreed with those who warned that precipitate independence would lead the newly independent nations into "trouble, strife, poverty, dictatorship" and other evils. His reply was, "Would you want the Romans to have stayed on in Britain?"Frankel, P H. "Iain Macleod", ''

After discussions with Lloyd and senior civil servants, Macmillan took the unprecedented step of appointing two Foreign Office cabinet ministers: Home, as Foreign Secretary, in the Lords, and Edward Heath, as Lord Privy Seal and deputy Foreign Secretary, in the Commons. With British application for admission to the European Economic Community (EEC) pending, Heath was given particular responsibility for the EEC negotiations as well as for speaking in the Commons on foreign affairs in general.

The opposition Labour party protested at Home's appointment; its leader, Hugh Gaitskell, said that it was "constitutionally objectionable" for a peer to be in charge of the Foreign Office. Macmillan responded that an accident of birth should not be allowed to deny him the services of "the best man for the job – the man I want at my side".Pike, p. 462 Hurd comments, "Like all such artificial commotions it died down after a time (and indeed was not renewed with any strength nineteen years later when

After discussions with Lloyd and senior civil servants, Macmillan took the unprecedented step of appointing two Foreign Office cabinet ministers: Home, as Foreign Secretary, in the Lords, and Edward Heath, as Lord Privy Seal and deputy Foreign Secretary, in the Commons. With British application for admission to the European Economic Community (EEC) pending, Heath was given particular responsibility for the EEC negotiations as well as for speaking in the Commons on foreign affairs in general.

The opposition Labour party protested at Home's appointment; its leader, Hugh Gaitskell, said that it was "constitutionally objectionable" for a peer to be in charge of the Foreign Office. Macmillan responded that an accident of birth should not be allowed to deny him the services of "the best man for the job – the man I want at my side".Pike, p. 462 Hurd comments, "Like all such artificial commotions it died down after a time (and indeed was not renewed with any strength nineteen years later when

In October 1963, just before the Conservative party's annual conference, Macmillan was taken ill with a prostatic obstruction. The condition was at first thought more serious than it turned out to be, and he announced that he would resign as Prime Minister as soon as a successor was appointed. Three senior politicians were considered likely successors, Butler ( First Secretary of State), Reginald Maudling (Chancellor of the Exchequer) and Lord Hailsham (Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Lords). ''

In October 1963, just before the Conservative party's annual conference, Macmillan was taken ill with a prostatic obstruction. The condition was at first thought more serious than it turned out to be, and he announced that he would resign as Prime Minister as soon as a successor was appointed. Three senior politicians were considered likely successors, Butler ( First Secretary of State), Reginald Maudling (Chancellor of the Exchequer) and Lord Hailsham (Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Lords). ''

"Macleod, Iain Norman (1913–1970)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, January 2011, accessed 21 April 2012 On 19 October Home was able to return to Buckingham Palace to

In international affairs, the most dramatic event during Douglas-Home's premiership was the assassination of John F. Kennedy, which happened about a month after the start of his tenure. Douglas-Home broadcast a tribute on television. He had liked and worked well with Kennedy, and did not develop such a satisfactory relationship with Lyndon Johnson. Their governments had a serious disagreement on the question of British trade with Cuba. Under Douglas-Home the colonies of Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland gained independence, though this was as a result of negotiations led by Macleod under the Macmillan government.

In Britain there was economic prosperity; exports "zoomed", according to ''The Times'', and the economy was growing at an annual rate of four per cent. Douglas-Home made no pretence to economic expertise; he commented that his problems were of two sorts: "The political ones are insoluble and the economic ones are incomprehensible." On another occasion he said, "When I have to read economic documents I have to have a box of matches and start moving them into position to simplify and illustrate the points to myself." He left Maudling in charge at the Treasury, and promoted Heath to a new business and economic portfolio. The latter took the lead in the one substantial piece of domestic legislation of Douglas-Home's premiership, the abolition of resale price maintenance.

The Resale Prices Bill was introduced to deny manufacturers and suppliers the power to stipulate the prices at which their goods must be sold by the retailer. At the time, up to forty per cent of goods sold in Britain were subject to such price fixing, to the detriment of competition and to the disadvantage of the consumer. Douglas-Home, less instinctively liberal on economic matters than Heath, would probably not have sponsored such a proposal unprompted, but he gave Heath his backing, in the face of opposition from some cabinet colleagues, including Butler, Hailsham and Lloyd, and a substantial number of Conservative backbenchers. They believed the change would benefit supermarkets and other large retailers at the expense of proprietors of small shops. The government was forced to make concessions to avoid defeat. Retail price maintenance would continue to be legal for some goods; these included books, on which it remained in force until market forces led to its abandonment in 1995. Manufacturers and suppliers would also be permitted to refuse to supply any retailer who sold their goods at less than cost price, as a loss leader. The bill had a difficult Parliamentary passage during which the Labour party generally abstained, leaving the Conservatives to vote for or against their own government. The bill received the

In international affairs, the most dramatic event during Douglas-Home's premiership was the assassination of John F. Kennedy, which happened about a month after the start of his tenure. Douglas-Home broadcast a tribute on television. He had liked and worked well with Kennedy, and did not develop such a satisfactory relationship with Lyndon Johnson. Their governments had a serious disagreement on the question of British trade with Cuba. Under Douglas-Home the colonies of Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland gained independence, though this was as a result of negotiations led by Macleod under the Macmillan government.

In Britain there was economic prosperity; exports "zoomed", according to ''The Times'', and the economy was growing at an annual rate of four per cent. Douglas-Home made no pretence to economic expertise; he commented that his problems were of two sorts: "The political ones are insoluble and the economic ones are incomprehensible." On another occasion he said, "When I have to read economic documents I have to have a box of matches and start moving them into position to simplify and illustrate the points to myself." He left Maudling in charge at the Treasury, and promoted Heath to a new business and economic portfolio. The latter took the lead in the one substantial piece of domestic legislation of Douglas-Home's premiership, the abolition of resale price maintenance.

The Resale Prices Bill was introduced to deny manufacturers and suppliers the power to stipulate the prices at which their goods must be sold by the retailer. At the time, up to forty per cent of goods sold in Britain were subject to such price fixing, to the detriment of competition and to the disadvantage of the consumer. Douglas-Home, less instinctively liberal on economic matters than Heath, would probably not have sponsored such a proposal unprompted, but he gave Heath his backing, in the face of opposition from some cabinet colleagues, including Butler, Hailsham and Lloyd, and a substantial number of Conservative backbenchers. They believed the change would benefit supermarkets and other large retailers at the expense of proprietors of small shops. The government was forced to make concessions to avoid defeat. Retail price maintenance would continue to be legal for some goods; these included books, on which it remained in force until market forces led to its abandonment in 1995. Manufacturers and suppliers would also be permitted to refuse to supply any retailer who sold their goods at less than cost price, as a loss leader. The bill had a difficult Parliamentary passage during which the Labour party generally abstained, leaving the Conservatives to vote for or against their own government. The bill received the  The term of the Parliament elected in 1959 was due to expire in October 1964. Parliament was dissolved on 25 September and after three weeks of campaigning the 1964 United Kingdom general election took place on 15 October. Douglas-Home's speeches dealt with the future of the nuclear deterrent, while fears of Britain's relative decline in the world, reflected in chronic balance of payment problems, helped the Labour Party's case. The Conservatives under Douglas-Home did much better than widely predicted, but Labour under Wilson won with a narrow majority. Labour won 317 seats, the Conservatives 304 and the Liberals 9.

The term of the Parliament elected in 1959 was due to expire in October 1964. Parliament was dissolved on 25 September and after three weeks of campaigning the 1964 United Kingdom general election took place on 15 October. Douglas-Home's speeches dealt with the future of the nuclear deterrent, while fears of Britain's relative decline in the world, reflected in chronic balance of payment problems, helped the Labour Party's case. The Conservatives under Douglas-Home did much better than widely predicted, but Labour under Wilson won with a narrow majority. Labour won 317 seats, the Conservatives 304 and the Liberals 9.

Determined that the party should abandon the "customary processes of consultation", which had caused such rancour when he was appointed in 1963, Douglas-Home set up an orderly process of secret balloting by Conservative MPs for the election of his immediate and future successors as party leader. In the interests of impartiality the ballot was organised by the 1922 Committee, the backbench Conservative MPs. Douglas-Home announced his resignation as Conservative leader on 22 July 1965. Three candidates stood in the 1965 Conservative Party leadership election: Heath, Maudling and Powell. Heath won with 150 votes (one of them cast by Douglas-Home) to 133 for Maudling and 15 for Powell.

Douglas-Home accepted the foreign affairs portfolio in Heath's shadow cabinet. Many expected this to be a short-lived appointment, a prelude to Douglas-Home's retirement from politics. It came at a difficult time in British foreign relations: events in the

Determined that the party should abandon the "customary processes of consultation", which had caused such rancour when he was appointed in 1963, Douglas-Home set up an orderly process of secret balloting by Conservative MPs for the election of his immediate and future successors as party leader. In the interests of impartiality the ballot was organised by the 1922 Committee, the backbench Conservative MPs. Douglas-Home announced his resignation as Conservative leader on 22 July 1965. Three candidates stood in the 1965 Conservative Party leadership election: Heath, Maudling and Powell. Heath won with 150 votes (one of them cast by Douglas-Home) to 133 for Maudling and 15 for Powell.

Douglas-Home accepted the foreign affairs portfolio in Heath's shadow cabinet. Many expected this to be a short-lived appointment, a prelude to Douglas-Home's retirement from politics. It came at a difficult time in British foreign relations: events in the

Heath invited Douglas-Home to join the cabinet, taking charge of Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs. In earlier centuries it had not been exceptional for a former prime minister to serve in the cabinet of a successor, and even in the previous fifty years Arthur Balfour, Stanley Baldwin, Ramsay MacDonald and Neville Chamberlain had done so. As of 2021, Douglas-Home is the last former premier to have served under a successor. Of Balfour's appointment to

Heath invited Douglas-Home to join the cabinet, taking charge of Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs. In earlier centuries it had not been exceptional for a former prime minister to serve in the cabinet of a successor, and even in the previous fifty years Arthur Balfour, Stanley Baldwin, Ramsay MacDonald and Neville Chamberlain had done so. As of 2021, Douglas-Home is the last former premier to have served under a successor. Of Balfour's appointment to  In east–west relations, Douglas-Home continued his policy of keeping the Soviet Union at bay. In September 1971, after receiving no satisfactory results from negotiations with Gromyko about the flagrant activities of the KGB in Britain, he expelled 105 Soviet diplomats for spying. In addition to the furore arising from this, the Soviets felt that the British government's approach to negotiations on détente in Europe was over-cautious, even sceptical. Gromyko was nonetheless realistic enough to maintain a working relationship with the British government. Within days of the expulsions from London he and Douglas-Home met and discussed the Middle East and disarmament. In this sphere of foreign policy, Douglas-Home was widely judged a success.

In negotiations on the future of Rhodesia Douglas-Home was less successful. He was instrumental in persuading the rebel leader, Ian Smith, to accept proposals for a transition to African majority rule. Douglas-Home set up an independent commission chaired by a senior British judge,

In east–west relations, Douglas-Home continued his policy of keeping the Soviet Union at bay. In September 1971, after receiving no satisfactory results from negotiations with Gromyko about the flagrant activities of the KGB in Britain, he expelled 105 Soviet diplomats for spying. In addition to the furore arising from this, the Soviets felt that the British government's approach to negotiations on détente in Europe was over-cautious, even sceptical. Gromyko was nonetheless realistic enough to maintain a working relationship with the British government. Within days of the expulsions from London he and Douglas-Home met and discussed the Middle East and disarmament. In this sphere of foreign policy, Douglas-Home was widely judged a success.

In negotiations on the future of Rhodesia Douglas-Home was less successful. He was instrumental in persuading the rebel leader, Ian Smith, to accept proposals for a transition to African majority rule. Douglas-Home set up an independent commission chaired by a senior British judge,

At the February 1974 general election the Heath government was narrowly defeated. Douglas-Home, then aged 70, stepped down at the second election of that year, called in October by the minority Labour government in the hope of winning a working majority. He returned to the House of Lords at the end of 1974 when he accepted a life peerage, becoming known as ''Baron Home of

At the February 1974 general election the Heath government was narrowly defeated. Douglas-Home, then aged 70, stepped down at the second election of that year, called in October by the minority Labour government in the hope of winning a working majority. He returned to the House of Lords at the end of 1974 when he accepted a life peerage, becoming known as ''Baron Home of

''The Times'', 10 October 1995 The latter was Home's heir, who became the 15th Earl of Home in 1995. Douglas-Home died at the Hirsel in October 1995 when he was 92, four months after the death of his parliamentary opponent Harold Wilson. Home was buried in Lennel churchyard, Coldstream.

Home's premiership was short and not conspicuous for radical innovation. Hurd remarks, "He was not capable of Macmillan's flights of imagination", but he was an effective practical politician. At the Commonwealth Relations Office and the Foreign Office he played an important role in helping to manage Britain's transition from imperial power to European partner. Both Thorpe and Hurd quote a memo that Macmillan wrote in 1963, intended to help the Queen choose his successor:

Douglas Hurd, once Home's private secretary, and many years later his successor (after seven intermediate holders of the post) as Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary, wrote this personal comment: "The three most courteous men I knew in politics were Lord Home, King Hussein of Jordan, and President

Home's premiership was short and not conspicuous for radical innovation. Hurd remarks, "He was not capable of Macmillan's flights of imagination", but he was an effective practical politician. At the Commonwealth Relations Office and the Foreign Office he played an important role in helping to manage Britain's transition from imperial power to European partner. Both Thorpe and Hurd quote a memo that Macmillan wrote in 1963, intended to help the Queen choose his successor:

Douglas Hurd, once Home's private secretary, and many years later his successor (after seven intermediate holders of the post) as Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary, wrote this personal comment: "The three most courteous men I knew in politics were Lord Home, King Hussein of Jordan, and President

Lord Dunglass (Alec Douglas-Home)

CricketArchive

Prime Ministers in the Post-War world: Alec Douglas-Home

lecture by D. R. Thorpe at Gresham College, 24 May 2007 (available for download as an audio or video file) * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Douglas-Home, Alec 1903 births 1995 deaths 20th-century prime ministers of the United Kingdom Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford British Secretaries of State for Foreign Affairs British Secretaries of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs British sportsperson-politicians Chairmen of the Steering Committee of the Bilderberg Group Home of the Hirsel, Alec Douglas-Home, Baron Conservative Party prime ministers of the United Kingdom Directors of the Bank of Scotland Earls of Home English cricketers of 1919 to 1945 English cricketers English people of Scottish descent Free Foresters cricketers H. D. G. Leveson Gower's XI cricketers Harlequins cricketers Knights of the Thistle Leaders of the Conservative Party (UK) Leaders of the House of Lords Lord Presidents of the Council Marylebone Cricket Club cricketers Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Scottish constituencies Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Members of the Steering Committee of the Bilderberg Group Middlesex cricketers Ministers in the Churchill caretaker government, 1945 Ministers in the Eden government, 1955–1957 Ministers in the third Churchill government, 1951–1955 Oxford University cricketers Parliamentary Private Secretaries to the Prime Minister People associated with Perth and Kinross People educated at Eton College People from Mayfair Politicians awarded knighthoods Presidents of the Marylebone Cricket Club Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom Scottish Conservative Party MPs Scottish Episcopalians UK MPs 1931–1935 UK MPs 1935–1945 UK MPs 1950–1951 UK MPs 1959–1964 UK MPs 1964–1966 UK MPs 1966–1970 UK MPs 1970–1974 UK MPs 1974 Home, E14 UK MPs who were granted peerages Life peers created by Elizabeth II Unionist Party (Scotland) MPs 20th-century British businesspeople Children of peers and peeresses created life peers People educated at Ludgrove School Alec

Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

from October 1963 to October 1964. He is notable for being the last Prime Minister to hold office while being a member of the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

, before renouncing his peerage and taking up a seat in the House of Commons for the remainder of his premiership. His reputation, however, rests more on his two spells as the UK's foreign secretary than on his brief premiership.

Within six years of first entering the House of Commons in 1931, Douglas-Home (then called by the courtesy title Lord Dunglass) became parliamentary aide to Neville Chamberlain, witnessing at first hand Chamberlain's efforts as Prime Minister to preserve peace through appeasement in the two years before the outbreak of the Second World War. In 1940 Dunglass was diagnosed with spinal tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

and was immobilised for two years. By the later stages of the war he had recovered enough to resume his political career, but lost his seat in the general election of 1945. He regained it in 1950, but the following year he left the Commons when, on the death of his father, he inherited the earldom of Home and thereby became a member of the House of Lords. Under the premierships of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

, Anthony Eden and Harold Macmillan he was appointed to a series of increasingly senior posts, including Leader of the House of Lords and Foreign Secretary. In the latter post, which he held from 1960 to 1963, he supported United States resolve in the Cuban Missile Crisis and was the United Kingdom's signatory of the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in August 1963.

In October 1963 Macmillan was taken ill and resigned as Prime Minister. Home was chosen to succeed him. By the 1960s it was generally considered unacceptable for a Prime Minister to sit in the House of Lords, and Home renounced his earldom and successfully stood for election to the House of Commons. The manner of his appointment was controversial, and two of Macmillan's cabinet ministers refused to take office under him. He was criticised by the Labour Party as an aristocrat, out of touch with the problems of ordinary families, and he came over stiffly in television interviews, by contrast with the Labour leader, Harold Wilson. The Conservative Party, in office since 1951, had lost standing as a result of the Profumo affair, a sexual scandal involving a defence minister in 1963, and at the time of Home's appointment as Prime Minister seemed headed for heavy electoral defeat. Home's premiership was the second briefest of the twentieth century, lasting two days short of a year. Among the legislation passed under his government was the abolition of resale price maintenance, bringing costs down for the consumer against the interests of producers of food and other commodities.

After narrow defeat in the general election of 1964 Douglas-Home resigned the leadership of his party, having instituted a new and less secretive method of electing the party leader. From 1970 to 1974 he served in the cabinet of Edward Heath as Secretary of State at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, an expanded version of the post of Foreign Secretary, which he had held earlier. After the defeat of the Heath government in 1974 he returned to the House of Lords as a life peer, and retired from front-line politics.

Early Life and education

Douglas-Home was born on 2 July 1903 at 28 South Street in Mayfair, London, the first of seven children of Lord Dunglass (the eldest son of the 12th Earl of Home) and his wife, the Lady Lilian Lambton (daughter of the 4th Earl of Durham). The boy's first name was customarily abbreviated to "Alec". Among the couple's younger children was the playwright William Douglas-Home. In 1918 the 12th Earl of Home died, Dunglass succeeded him in the earldom, and the courtesy title passed to his son, Alec Douglas-Home, who was styled Lord Dunglass until 1951. The young Lord Dunglass was educated at Ludgrove School, followed byEton College

Eton College () is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI of England, Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. i ...

. At Eton his contemporaries included Cyril Connolly

Cyril Vernon Connolly CBE (10 September 1903 – 26 November 1974) was an English literary critic and writer. He was the editor of the influential literary magazine '' Horizon'' (1940–49) and wrote ''Enemies of Promise'' (1938), which comb ...

, who later described him as:

After Eton, Dunglass went to Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church ( la, Ædes Christi, the temple or house, '' ædēs'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, the college is uniq ...

, where he graduated with a third-class honours BA degree in Modern History in 1925.

Dunglass was a talented sportsman. In addition to representing Eton at fives, he was a capable cricketer at school, club and county level, and was unique among British prime ministers in having played first-class cricket

First-class cricket, along with List A cricket and Twenty20 cricket, is one of the highest-standard forms of cricket. A first-class match is one of three or more days' scheduled duration between two sides of eleven players each and is officiall ...

. Coached by George Hirst

George Herbert Hirst (7 September 1871 – 10 May 1954) was a professional English cricketer who played first-class cricket for Yorkshire County Cricket Club between 1891 and 1921, with a further appearance in 1929. One of the best all-r ...

, he became in ''Wisden'''s phrase "a useful member of the Eton XI" that included Percy Lawrie and Gubby Allen

Sir George Oswald Browning "Gubby" Allen CBE (31 July 190229 November 1989) was a cricketer who captained England in eleven Test matches. In first-class matches, he played for Middlesex and Cambridge University. A fast bowler and hard-hitti ...

. Wisden observed, "In the rain-affected Eton-Harrow match of 1922 he scored 66, despite being hindered by a saturated outfield, and then took 4 for 37 with his medium-paced out-swingers". At first-class level he represented the Oxford University Cricket Club, Middlesex County Cricket Club and Marylebone Cricket Club

Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) is a cricket club founded in 1787 and based since 1814 at Lord's Cricket Ground, which it owns, in St John's Wood, London. The club was formerly the governing body of cricket retaining considerable global influe ...

(MCC). Between 1924 and 1927 he played ten first-class matches, scoring 147 runs at an average of 16.33 with a best score of 37 not out. As a bowler he took 12 wickets at an average of 30.25 with a best of 3 for 43. Three of his first-class games were internationals against Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the List of South American countries by area, second-largest ...

on the MCC "representative" tour of South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

in 1926–27."Sir Alec Douglas-Home"CricInfo, accessed 13 April 2012 Dunglass began serving in the Territorial Army in 1924 as a

lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

in the Lanarkshire Yeomanry, and was promoted to captain in 1928.

Professional career

Member of Parliament (1931–1937)

The courtesy title Lord Dunglass did not carry with it membership of theHouse of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

, and Dunglass was eligible to seek election to the House of Commons. Unlike many aristocratic families, the Douglas-Homes had little history of political service. Uniquely in the family the 11th earl, Dunglass's great-grandfather, had held government office, as Under-Secretary

Undersecretary (or under secretary) is a title for a person who works for and has a lower rank than a secretary (person in charge). It is used in the executive branch of government, with different meanings in different political systems, and is al ...

at the Foreign Office in Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by ...

's 1828–1830 government.Dutton, p. 2 Dunglass's father stood, reluctantly and unsuccessfully, for Parliament before succeeding to the earldom.

Dunglass had shown little interest in politics while at Eton or Oxford. He had not joined the Oxford Union as budding politicians usually did. However, as heir to the family estates he was doubtful about the prospect of life as a country gentleman: "I was always rather discontented with this role and felt it wasn't going to be enough." His biographer David Dutton believes that Dunglass became interested in politics because of the widespread unemployment and poverty in the Scottish lowlands where his family lived. Later in his career, when he had become Prime Minister, Dunglass (by then Sir Alec Douglas-Home) wrote in a memorandum: "I went into politics because I felt that it was a form of public service and that as nearly a generation of politicians had been cut down in the first war those who had anything to give in the way of leadership ought to do so".Hennessy, p. 285 His political thinking was influenced by that of Noel Skelton, a member of the Unionist party (as the Conservatives were called in Scotland between 1912 and 1965). Skelton advocated "a property-owning democracy", based on share-options for workers and industrial democracy. Dunglass was not persuaded by the socialist ideal of public ownership. He shared Skelton's view that "what everybody owns nobody owns".

With Skelton's support Dunglass secured the Unionist candidacy at Coatbridge for the 1929 general election. It was not a seat that the Unionists expected to win, and he lost to his Labour opponent with 9,210 votes to Labour's 16,879. It was, however, valuable experience for Dunglass, who was of a gentle and uncombative disposition and not a natural orator; he began to learn how to deal with hostile audiences and get his message across. When a coalition " National Government" was formed in 1931 to deal with a financial crisis Dunglass was adopted as the pro-coalition Unionist candidate for Lanark. The electorate of the area was mixed, and the constituency was not seen as a safe seat for any party; at the 1929 election Labour had captured it from the Unionists. With the backing of the pro-coalition Liberal party, which supported him rather than fielding its own candidate, Dunglass easily beat the Labour candidate.Dutton, p. 7

Membership of the new House of Commons was overwhelmingly made up of pro-coalition MPs, and there was therefore a large number of eligible members for the government posts to be filled. In Dutton's phrase, "it would have been easy for Dunglass to have languished indefinitely in backbench

In Westminster and other parliamentary systems, a backbencher is a member of parliament (MP) or a legislator who occupies no governmental office and is not a frontbench spokesperson in the Opposition, being instead simply a member of th ...

obscurity." However, Skelton, appointed as Under-secretary at the Scottish Office, offered Dunglass the unpaid post of unofficial parliamentary aide. This was doubly advantageous to Dunglass. Any MP appointed as official Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) to a government minister was privy to the inner workings of government but was expected to maintain a discreet silence in the House of Commons. Dunglass achieved the first without having to observe the second. He made his maiden speech in February 1932 on the subject of economic policy, advocating a cautiously protectionist approach to cheap imports. He countered Labour's objection that this would raise the cost of living, arguing that a tariff "stimulates employment and gives work ndincreases the purchasing power of the people by substituting wages for unemployment benefit."

During four years as Skelton's aide Dunglass was part of a team working on a wide range of issues, from medical services in rural Scotland to land settlements, fisheries, education, and industry. Dunglass was appointed official PPS to Anthony Muirhead, junior minister at the Ministry of Labour

The Ministry of Labour ('' UK''), or Labor ('' US''), also known as the Department of Labour, or Labor, is a government department responsible for setting labour standards, labour dispute mechanisms, employment, workforce participation, training, a ...

, in 1935, and less than a year later became PPS to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Neville Chamberlain.

Chamberlain and war

By the time of Dunglass's appointment Chamberlain was generally seen as the heir to the premiership, and in 1937 the incumbent,Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

, retired, and Chamberlain succeeded him. He retained Dunglass as his PPS, a role described by the biographer D. R. Thorpe as "the right-hand man ... the eyes and ears of Neville Chamberlain", and by Dutton as "liaison officer with the Parliamentary party, transmitting and receiving information and eepinghis master informed of the mood on the government's back benches." This was particularly important for Chamberlain, who was often seen as distant and aloof; Douglas Hurd wrote that he "lacked the personal charm which makes competent administration palatable to wayward colleagues – a gift which his parliamentary private secretary possessed in abundance."Hurd, Dougla"Home, Alexander Frederick Douglas-, fourteenth earl of Home and Baron Home of the Hirsel (1903–1995)"

''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 14 April 2012 Dunglass admired Chamberlain, despite his daunting personality: "I liked him, and I think he liked me. But if one went in at the end of the day for a chat or a gossip, he would be inclined to ask 'What do you want?' He was a very difficult man to get to know."

As Chamberlain's aide Dunglass witnessed at first-hand the Prime Minister's attempts to prevent a second world war through appeasement of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

's Germany. When Chamberlain had his final meeting with Hitler at Munich in September 1938, Dunglass accompanied him. Having gained a short-lived extension of peace by acceding to Hitler's territorial demands at the expense of Czechoslovakia, Chamberlain was welcomed back to London by cheering crowds. Ignoring Dunglass's urging he made an uncharacteristically grandiloquent speech, claiming to have brought back "Peace with Honour" and promising "peace for our time". These words were to haunt him when Hitler's continued aggression made war unavoidable less than a year later. Chamberlain remained prime minister from the outbreak of war in September 1939 until May 1940, when, in Dunglass's words, "he could no longer command support of a majority in the Conservative party". After a vote in the Commons, in which the government's majority fell from more than 200 to 81, Chamberlain made way for Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

. He accepted the non-departmental post of Lord President of the Council in the new coalition government; Dunglass remained as his PPS, having earlier declined the offer of a ministerial post as Under-secretary at the Scottish Office. Although Chamberlain's reputation never recovered from Munich, and his supporters such as R. A. Butler

Richard Austen Butler, Baron Butler of Saffron Walden, (9 December 1902 – 8 March 1982), also known as R. A. Butler and familiarly known from his initials as Rab, was a prominent British Conservative Party politician. ''The Times'' obituary ...

suffered throughout their later careers from the "appeasement" tag, Dunglass largely escaped blame. Nevertheless, Dunglass firmly maintained all his life that the Munich agreement had been vital to the survival of Britain and the defeat of Nazi Germany by giving the UK an extra year to prepare for a war that it could not have contested in 1938. Within months of his leaving the premiership Chamberlain's health began to fail; he resigned from the cabinet, and died after a short illness in November 1940.

Dunglass had volunteered for active military service, seeking to rejoin the Lanarkshire Yeomanry shortly after Chamberlain left Downing Street. The consequent medical examination revealed that Dunglass had a hole in his spine surrounded by tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, ...

in the bone. Without surgery he would have been unable to walk within a matter of months.Thorpe (1997), p. 109 An innovative and hazardous operation was performed in September 1940, lasting six hours, in which the diseased bone in the spine was scraped away and replaced with healthy bone from the patient's shin.

For all of Dunglass's humour and patience, the following two years were a grave trial. He was encased in plaster and kept flat on his back for most of that period. Although buoyed up by the sensitive support of his wife and family, as he later confessed, "I often felt that I would be better dead". Towards the end of 1942 he was released from his plaster jacket and fitted with a spinal brace, and in early 1943 he was mobile for the first time since the operation. During his incapacity he read voraciously; among the works he studied were ''Das Kapital

''Das Kapital'', also known as ''Capital: A Critique of Political Economy'' or sometimes simply ''Capital'' (german: Das Kapital. Kritik der politischen Ökonomie, link=no, ; 1867–1883), is a foundational theoretical text in materialist phi ...

'', and works by Engels and Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

, biographies of nineteenth and twentieth century politicians, and novels by authors from Dostoyevsky to Koestler.

In July 1943 Dunglass attended the House of Commons for the first time since 1940, and began to make a reputation as a backbench member, particularly for his expertise in the field of foreign affairs. He foresaw a post-imperial future for Britain and emphasised the need for strong European ties after the war. In 1944, with the war now turning in the Allies' favour, Dunglass spoke eloquently about the importance of resisting the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

's ambition to dominate eastern Europe. His boldness in publicly urging Churchill not to give in to Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

was widely remarked upon; many, including Churchill himself, observed that some of those once associated with appeasement were determined that it should not be repeated in the face of Russian aggression. Labour left the wartime coalition in May 1945 and Churchill formed a caretaker Conservative government, pending a general election in July. Dunglass was appointed to his first ministerial post: Anthony Eden remained in charge of the Foreign Office, and Dunglass was appointed as one of his two Under-secretaries of State.

Postwar and House of Lords (1945–57)

In 1950, Clement Attlee, the Labour Prime Minister, called a general election. Dunglass was invited to stand once again as Unionist candidate for Lanark. Having been disgusted at personal attacks during the 1945 campaign by Tom Steele, his Labour opponent, Dunglass did not scruple to remind the voters of Lanark that Steele had warmly thanked the Communist Party and its members for helping him take the seat from the Unionists. By 1950, with theCold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

at its height, Steele's association with the communists was a crucial electoral liability. Dunglass regained the seat with one of the smallest majorities in any British constituency: 19,890 to Labour's 19,205. Labour narrowly won the general election, with a majority of five.

In July 1951 the 13th earl died. Dunglass succeeded him, inheriting the title of Earl of Home together with the extensive family estates, including the Hirsel, the Douglas-Homes' principal residence. The new Lord Home took his seat in the Lords; a by-election was called to appoint a new MP for Lanark, but it was still pending when Attlee called another general election in October 1951. The Unionists held Lanark, and the national result gave the Conservatives under Churchill a small but working majority of seventeen.

Home was appointed to the new post of Minister of State at the Scottish Office, a middle-ranking position, senior to Under-secretary but junior to James Stuart, the Secretary of State, who was a member of the cabinet. Stuart, previously an influential chief whip, was a confidant of Churchill, and possibly the most powerful Scottish Secretary in any government. Thorpe writes that Home owed his appointment to Stuart's advocacy rather than to any great enthusiasm on the Prime Minister's part (Churchill referred to him as "Home sweet Home").Thorpe (1997), p. 141 In addition to his ministerial position Home was appointed to membership of the

In July 1951 the 13th earl died. Dunglass succeeded him, inheriting the title of Earl of Home together with the extensive family estates, including the Hirsel, the Douglas-Homes' principal residence. The new Lord Home took his seat in the Lords; a by-election was called to appoint a new MP for Lanark, but it was still pending when Attlee called another general election in October 1951. The Unionists held Lanark, and the national result gave the Conservatives under Churchill a small but working majority of seventeen.

Home was appointed to the new post of Minister of State at the Scottish Office, a middle-ranking position, senior to Under-secretary but junior to James Stuart, the Secretary of State, who was a member of the cabinet. Stuart, previously an influential chief whip, was a confidant of Churchill, and possibly the most powerful Scottish Secretary in any government. Thorpe writes that Home owed his appointment to Stuart's advocacy rather than to any great enthusiasm on the Prime Minister's part (Churchill referred to him as "Home sweet Home").Thorpe (1997), p. 141 In addition to his ministerial position Home was appointed to membership of the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

(PC), an honour granted only selectively to ministers below cabinet rank.

Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

Eli ...

of England was never queen of Scotland, some nationalists maintained when Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

came to the British throne in 1952 that in Scotland she should be styled "Elizabeth I". Churchill said in the House of Commons that considering the "greatness and splendour of Scotland", and the contribution of the Scots to British and world history, "they ought to keep their silliest people in order". Home nevertheless arranged that in Scotland new pillar boxes were decorated with the royal crown instead of the full cypher.

When Eden succeeded Churchill as Prime Minister in 1955 he promoted Home to the cabinet as Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations. At the time of this appointment Home had not been to any of the countries within his ministerial remit, and he quickly arranged to visit Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, India, Pakistan and Ceylon.Dutton, p. 21 He had to deal with the sensitive subject of immigration from and between Commonwealth countries, where a delicate balance had to be struck between resistance in some quarters in Britain and Australia to non-white immigration on the one hand, and on the other the danger of sanctions in India and Pakistan against British commercial interests if discriminatory policies were pursued. In most respects, when Home took up the appointment it seemed to be a relatively uneventful period in the history of the Commonwealth. The upheaval of Indian independence in 1947 was well in the past, and the wave of decolonising of the 1960s was yet to come. However, it fell to Home to maintain Commonwealth unity during the Suez Crisis in 1956, described by Dutton as "the most divisive in its history to date". Australia, New Zealand and South Africa backed the Anglo-French invasion of Egypt to regain control of the Suez Canal. Canada, Ceylon, India and Pakistan opposed it.Thorpe (1997), pp. 178–81

There appeared to be a real danger that Ceylon, India and, particularly, Pakistan might leave the Commonwealth. Home was firm in his support of the invasion, but used his contacts with Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India du ...

, V. K. Krishna Menon, Nan Pandit and others to try to prevent the Commonwealth from breaking up. His relationship with Eden was supportive and relaxed; he felt able, as others did not, to warn Eden of unease about Suez both internationally and among some members of the cabinet. Eden dismissed the latter as the "weak sisters"; the most prominent was Butler, whose perceived hesitancy over Suez on top of his support for appeasement of Hitler damaged his standing within the Conservative party. When the invasion was abandoned under pressure from the US in November 1956, Home worked with the dissenting members of the Commonwealth to build the organisation into what Hurd calls "a modern multiracial Commonwealth".

Macmillan's government

Eden resigned in January 1957. In 1955 he had been the obvious successor to Churchill, but this time there was no clear heir apparent. Leaders of the Conservative party were not elected by ballot of MPs or party members, but emerged after informal soundings within the party, known as "the customary processes of consultation". The chief whip, Edward Heath, canvassed the views of backbench Conservative MPs, and two senior Conservative peers, the Lord President of the Council, Lord Salisbury, and the Lord Chancellor,Lord Kilmuir

David Patrick Maxwell Fyfe, 1st Earl of Kilmuir, (29 May 1900 – 27 January 1967), known as Sir David Maxwell Fyfe from 1942 to 1954 and as Viscount Kilmuir from 1954 to 1962, was a British Conservative politician, lawyer and judge who combine ...

, saw members of the cabinet individually to ascertain their preferences. Only one cabinet colleague supported Butler; the rest, including Home, opted for Macmillan. Churchill, whom the Queen consulted, did the same.Thorpe (1997), p. 189 Macmillan was appointed Prime Minister on 10 January 1957.

In the new administration Home remained at the Commonwealth Relations Office. Much of his time was spent on matters relating to Africa, where the futures of Bechuanaland and the Central African Federation needed to be agreed. Among other matters in which he was involved were the dispute between India and Pakistan over Kashmir, assisted emigration from Britain to Australia, and relations with Archbishop Makarios of Cyprus. The last unexpectedly led to an enhanced cabinet role for Home. Makarios, leader of the militant anti-British and pro-Greek movement, was detained in exile in the Seychelles

Seychelles (, ; ), officially the Republic of Seychelles (french: link=no, République des Seychelles; Creole: ''La Repiblik Sesel''), is an archipelagic state consisting of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city, ...

. Macmillan, with the agreement of Home and most of the cabinet, decided that this imprisonment was doing more harm than good to Britain's position in Cyprus, and ordered Makarios's release. Lord Salisbury strongly dissented from the decision and resigned from the cabinet in March 1957. Macmillan added Salisbury's responsibilities to Home's existing duties, making him Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Lords. The first of these posts was largely honorific, but the leadership of the Lords put Home in charge of getting the government's business through the upper house, and brought him nearer to the centre of power. In Hurd's phrase, "By the imperceptible process characteristic of British politics he found himself month by month, without any particular manoeuvre on his part, becoming an indispensable figure in the government."

Home was generally warmly regarded by colleagues and opponents alike, and there were few politicians who did not respond well to him. One was Attlee, but as their political primes did not overlap this was of minor consequence. More important was Iain Macleod's prickly relationship with Home. Macleod, Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1959–61, was, like Butler, on the liberal wing of the Conservative party; he was convinced, as Home was not, that Britain's colonies in Africa should have majority rule and independence as quickly as possible. Their spheres of influence overlapped in the Central African Federation.

Macleod wished to push ahead with majority rule and independence; Home believed in a more gradual approach to independence, accommodating both white minority and black majority opinions and interests. Macleod disagreed with those who warned that precipitate independence would lead the newly independent nations into "trouble, strife, poverty, dictatorship" and other evils. His reply was, "Would you want the Romans to have stayed on in Britain?"Frankel, P H. "Iain Macleod", ''

Home was generally warmly regarded by colleagues and opponents alike, and there were few politicians who did not respond well to him. One was Attlee, but as their political primes did not overlap this was of minor consequence. More important was Iain Macleod's prickly relationship with Home. Macleod, Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1959–61, was, like Butler, on the liberal wing of the Conservative party; he was convinced, as Home was not, that Britain's colonies in Africa should have majority rule and independence as quickly as possible. Their spheres of influence overlapped in the Central African Federation.

Macleod wished to push ahead with majority rule and independence; Home believed in a more gradual approach to independence, accommodating both white minority and black majority opinions and interests. Macleod disagreed with those who warned that precipitate independence would lead the newly independent nations into "trouble, strife, poverty, dictatorship" and other evils. His reply was, "Would you want the Romans to have stayed on in Britain?"Frankel, P H. "Iain Macleod", ''The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British weekly newspaper printed in demitab format and published digitally. It focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, technology, and culture. Based in London, the newspaper is owned by The Eco ...

'', 23 October 1976, p. 4 He threatened to resign unless he was allowed to release the leading Nyasaland activist Hastings Banda from prison, a move that Home and others thought unwise and liable to provoke distrust of Britain among the white minority in the federation. Macleod had his way, but by that time Home was no longer at the Commonwealth Relations Office.

Foreign Secretary (1960–1963)

In 1960 the Chancellor of the Exchequer,Derick Heathcoat-Amory

Derick Heathcoat-Amory, 1st Viscount Amory, , ( ; 26 December 1899 – 20 January 1981) was a British Conservative politician and member of the House of Lords.

He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1958 and 1960, and later as Chanc ...

, insisted on retiring. Macmillan agreed with Heathcoat-Amory that the best successor at the Treasury would be the current Foreign Secretary, Selwyn Lloyd. In terms of ability and experience the obvious candidate to take over from Lloyd at the Foreign Office was Home, but by 1960 there was an expectation that the Foreign Secretary would be a member of the House of Commons. The post had not been held by a peer since Lord Halifax

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as The Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and The Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a senior British Conservative politician of the 19 ...

in 1938–40; Eden had wished to appoint Salisbury in 1955, but concluded that it would be unacceptable to the Commons.

After discussions with Lloyd and senior civil servants, Macmillan took the unprecedented step of appointing two Foreign Office cabinet ministers: Home, as Foreign Secretary, in the Lords, and Edward Heath, as Lord Privy Seal and deputy Foreign Secretary, in the Commons. With British application for admission to the European Economic Community (EEC) pending, Heath was given particular responsibility for the EEC negotiations as well as for speaking in the Commons on foreign affairs in general.

The opposition Labour party protested at Home's appointment; its leader, Hugh Gaitskell, said that it was "constitutionally objectionable" for a peer to be in charge of the Foreign Office. Macmillan responded that an accident of birth should not be allowed to deny him the services of "the best man for the job – the man I want at my side".Pike, p. 462 Hurd comments, "Like all such artificial commotions it died down after a time (and indeed was not renewed with any strength nineteen years later when

After discussions with Lloyd and senior civil servants, Macmillan took the unprecedented step of appointing two Foreign Office cabinet ministers: Home, as Foreign Secretary, in the Lords, and Edward Heath, as Lord Privy Seal and deputy Foreign Secretary, in the Commons. With British application for admission to the European Economic Community (EEC) pending, Heath was given particular responsibility for the EEC negotiations as well as for speaking in the Commons on foreign affairs in general.

The opposition Labour party protested at Home's appointment; its leader, Hugh Gaitskell, said that it was "constitutionally objectionable" for a peer to be in charge of the Foreign Office. Macmillan responded that an accident of birth should not be allowed to deny him the services of "the best man for the job – the man I want at my side".Pike, p. 462 Hurd comments, "Like all such artificial commotions it died down after a time (and indeed was not renewed with any strength nineteen years later when Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

appointed another peer, Lord Carrington

Peter Alexander Rupert Carington, 6th Baron Carrington, Baron Carington of Upton, (6 June 1919 – 9July 2018), was a British Conservative Party politician and hereditary peer who served as Defence Secretary from 1970 to 1974, Foreign Secretar ...

, to the same post)". The Home–Heath partnership worked well. Despite their different backgrounds and ages – Home an Edwardian

The Edwardian era or Edwardian period of British history spanned the reign of King Edward VII, 1901 to 1910 and is sometimes extended to the start of the First World War. The death of Queen Victoria in January 1901 marked the end of the Victori ...

aristocrat and Heath a lower-middle class meritocrat raised in the inter-war years – the two men respected and liked one another. Home supported Macmillan's ambition to get Britain into the EEC, and was happy to leave the negotiations in Heath's hands.

Home's attention was mainly concentrated on the Cold War, where his forcefully expressed anti-communist beliefs were tempered by a pragmatic approach to dealing with the Soviet Union. His first major problem in this sphere was in 1961 when on the orders of the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

, the Berlin Wall was erected to stop East Germans

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

escaping to West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

via West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under mi ...

. Home wrote to his American counterpart, Dean Rusk, "The prevention of East Berliners getting into West Berlin has never been a ''casus belli'' for us. We are concerned with Western access to Berlin and that is what we must maintain." The governments of West Germany, Britain and the US quickly reached agreement on their joint negotiating position; it remained to persuade President de Gaulle of France to align himself with the allies. During their discussions Macmillan commented that de Gaulle showed "all the rigidity of a poker without its occasional warmth." An agreement was reached, and the allies tacitly recognised that the wall was going to remain in place. The Soviets for their part did not seek to cut off allied access to West Berlin through East German territory.

The following year the Cuban Missile Crisis threatened to turn the Cold War into a nuclear one. Soviet nuclear missiles were brought to Cuba, provocatively close to the US. The American president, John F Kennedy, insisted that they must be removed, and many thought that the world was on the brink of catastrophe with nuclear exchanges between the two super-powers. Despite a public image of unflappable calm, Macmillan was by nature nervous and highly strung. During the missile crisis, Home, whose calm was genuine and innate, strengthened the Prime Minister's resolve, and encouraged him to back up Kennedy's defiance of Soviet threats of nuclear attack. The Lord Chancellor ( Lord Dilhorne), the Attorney General ( Sir John Hobson) and the Solicitor General, ( Sir Peter Rawlinson) privately gave Home their opinion that the American blockade of Cuba was a breach of international law, but he continued to advocate a policy of strong support for Kennedy. When Khrushchev backed down and removed the Soviet missiles from Cuba, Home commented:

The principal landmark of Home's term as Foreign Secretary was also in the sphere of east–west relations: the negotiation and signature of the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1963. He got on well with his American and Soviet counterparts, Rusk and Andrei Gromyko. The latter wrote that whenever he met Home there were "no sudden, still less brilliant, breakthroughs" but "each meeting left a civilised impression that made the next meeting easier." Gromyko concluded that Home added sharpness to British foreign policy. Gromyko, Home and Rusk signed the treaty in Moscow on 5 August 1963."Three Ministers Sign Test Ban Treaty in Moscow", ''The Times'', 6 August 1963, p. 8 After the fear provoked internationally by the Cuban Missile Crisis, the ban on nuclear testing in the atmosphere, in outer space and under water was widely welcomed as a step towards ending the cold war. For the British government the good news from Moscow was doubly welcome for drawing attention away from the Profumo affair, a sexual scandal involving a senior minister, which had left Macmillan's administration looking vulnerable.

Successor to Macmillan

In October 1963, just before the Conservative party's annual conference, Macmillan was taken ill with a prostatic obstruction. The condition was at first thought more serious than it turned out to be, and he announced that he would resign as Prime Minister as soon as a successor was appointed. Three senior politicians were considered likely successors, Butler ( First Secretary of State), Reginald Maudling (Chancellor of the Exchequer) and Lord Hailsham (Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Lords). ''

In October 1963, just before the Conservative party's annual conference, Macmillan was taken ill with a prostatic obstruction. The condition was at first thought more serious than it turned out to be, and he announced that he would resign as Prime Minister as soon as a successor was appointed. Three senior politicians were considered likely successors, Butler ( First Secretary of State), Reginald Maudling (Chancellor of the Exchequer) and Lord Hailsham (Lord President of the Council and Leader of the House of Lords). ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' summed up their support:

In the same article, Home was mentioned in passing as "a fourth hypothetical candidate" on whom the party could compromise if necessary.

It was assumed in the ''Times'' article, and by other commentators, that if Hailsham (or Home) was a candidate he would have to renounce his peerage. This had been made possible for the first time by recent legislation. The last British Prime Minister to sit in the House of Lords was the third Marquess of Salisbury in 1902. By 1923, having to choose between Baldwin and Lord Curzon, George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother ...

decided that "the requirements of the present times" obliged him to appoint a Prime Minister from the Commons. His private secretary recorded that the King "believed he would not be fulfilling his trust were he now to make his selection of Prime Minister from the House of Lords". Similarly, after the resignation of Neville Chamberlain in 1940 there were two likely successors, Churchill and Halifax, but the latter ruled himself out for the premiership on the grounds that his membership of the House of Lords disqualified him. In 1963, therefore, it was well established that the Prime Minister should be a member of the House of Commons. On 10 October Hailsham announced his intention to renounce his viscountcy.

The "customary processes" once again took place. The usual privacy of the consultations was made impossible because they took place during the party conference, and the potential successors made their bids very publicly. Butler had the advantage of giving the party leader's keynote address to the conference in Macmillan's absence, but was widely thought to have wasted the opportunity by delivering an uninspiring speech. Hailsham put off many potential backers by his extrovert, and some thought vulgar, campaigning. Maudling, like Butler, made a speech that failed to impress the conference. Senior Conservative figures such as Lord Woolton and Selwyn Lloyd urged Home to make himself available for consideration.

Having ruled himself out of the race when the news of Macmillan's illness broke, Home angered at least two of his cabinet colleagues by changing his mind. Macmillan quickly came to the view that Home would be the best choice as his successor, and gave him valuable behind-the-scenes backing. He let it be known that if he recovered he would be willing to serve as a member of a Home cabinet. He had earlier favoured Hailsham, but changed his mind when he learned from Lord Harlech

Baron Harlech, of Harlech in the County of Merioneth, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1876 for the Conservative politician John Ormsby-Gore, with remainder to his younger brother William. He had previously ...

, the British ambassador to the US, that the Kennedy administration was uneasy at the prospect of Hailsham as Prime Minister, and from his chief whip that Hailsham, seen as a right-winger, would alienate moderate voters.Thorpe (1997), pp. 303–05

Butler, by contrast, was seen as on the liberal wing of the Conservatives, and his election as leader might split the party. The Lord Chancellor, Lord Dilhorne, conducted a poll of cabinet members, and reported to Macmillan that taking account of first and second preferences there were ten votes for Home, four for Maudling, three for Butler and two for Hailsham.

The appointment of a Prime Minister remained part of the royal prerogative

The royal prerogative is a body of customary authority, privilege and immunity, recognized in common law and, sometimes, in civil law jurisdictions possessing a monarchy, as belonging to the sovereign and which have become widely vested in th ...

, on which the monarch had no constitutional duty to consult an outgoing Prime Minister. Nevertheless, Macmillan advised the Queen that he considered Home the right choice. Little of this was known beyond the senior ranks of the party and the royal secretariat. On 18 October ''The Times'' ran the headline, "The Queen May Send for Mr. Butler Today". ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

'' and ''The Financial Times

The ''Financial Times'' (''FT'') is a British daily newspaper printed in broadsheet and published digitally that focuses on business and economic current affairs. Based in London, England, the paper is owned by a Japanese holding company, Nik ...

'' also predicted that Butler was about to be appointed. The Queen sent for Home the same day. Aware of the divisions within the governing party, she did not appoint him Prime Minister, but invited him to see whether he was able to form a government.

Home's cabinet colleagues Enoch Powell and Iain Macleod, who disapproved of his candidacy, made a last-minute effort to prevent him from taking office by trying to persuade Butler and the other candidates not to take posts in a Home cabinet. Butler, however, believed it to be his duty to serve in the cabinet; he refused to have any part in the conspiracy, and accepted the post of Foreign Secretary.Howard, p. 321 The other candidates followed Butler's lead and only Powell and Macleod held out and refused office under Home. Macleod commented, "One does not expect to have many people with one in the last ditch".Goldsworthy, Davi"Macleod, Iain Norman (1913–1970)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004; online edition, January 2011, accessed 21 April 2012 On 19 October Home was able to return to Buckingham Palace to

kiss hands

To kiss hands is a constitutional term used in the United Kingdom to refer to the formal installation of the prime minister or other Crown-appointed government ministers to their office.

Overview

In the past, the term referred to the requir ...

as Prime Minister.Pike, p. 463 The press was not only wrong-footed by the appointment, but generally highly critical. The pro-Labour ''Daily Mirror

The ''Daily Mirror'' is a British national daily Tabloid journalism, tabloid. Founded in 1903, it is owned by parent company Reach plc. From 1985 to 1987, and from 1997 to 2002, the title on its Masthead (British publishing), masthead was simpl ...

'' said on its front page:

''The Times'', generally pro-Conservative, had backed Butler, and called it "prodigal" of the party to pass over his many talents. The paper praised Home as "an outstandingly successful Foreign Secretary", but doubted his grasp of domestic affairs, his modernising instincts and his suitability "to carry the Conservative Party through a fierce and probably dirty campaign" at the general election due within a year. ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers '' The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the ...

'', liberal in its political outlook, remarked that Home "does not look like the man to impart force and purpose to his Cabinet and the country" and suggested that he seemed too frail politically to be even a stop-gap. ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the ...