Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq;

Yup'ik

The Yup'ik or Yupiaq (sg & pl) and Yupiit or Yupiat (pl), also Central Alaskan Yup'ik, Central Yup'ik, Alaskan Yup'ik ( own name ''Yup'ik'' sg ''Yupiik'' dual ''Yupiit'' pl; russian: Юпики центральной Аляски), are an I ...

: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a

state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

located in the

Western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the We ...

on the northwest extremity of

North America. A

semi-exclave of the U.S., it borders the

Canadian province of

British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

and the

Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

territory to the east; it also shares a

maritime border

A maritime boundary is a conceptual division of the Earth's water surface areas using physiographic or geopolitical criteria. As such, it usually bounds areas of exclusive national rights over mineral and biological resources,VLIZ Maritime Boun ...

with the

Russian Federation

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

's

Chukotka Autonomous Okrug to the west, just across the

Bering Strait. To the north are the

Chukchi and

Beaufort Seas of the

Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

, while the

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contin ...

lies to the south and southwest.

Alaska is by far the

largest U.S. state by area, comprising more total area than the next three largest states (

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

,

California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

, and

Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columb ...

) combined. It represents the

seventh-largest subnational division in the world. It is the

third-least populous and the

most sparsely populated state, but by far the continent's most populous territory located mostly north of the

60th parallel, with a population of 736,081 as of 2020—more than quadruple the combined populations of

Northern Canada and

Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland i ...

.

Approximately half of Alaska's residents live within the

Anchorage metropolitan area

The Anchorage Metropolitan Statistical Area, as defined by the United States Census Bureau, is an area consisting of the Municipality of Anchorage and the Matanuska-Susitna Borough in the south central region of Alaska.

As of the 2010 census, ...

. The state capital of

Juneau

The City and Borough of Juneau, more commonly known simply as Juneau ( ; tli, Dzánti K'ihéeni ), is the capital city of the state of Alaska. Located in the Gastineau Channel and the Alaskan panhandle, it is a unified municipality and the s ...

is the second-

largest city in the United States by area, comprising more territory than the states of

Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the smallest U.S. state by area and the seventh-least populous, with slightly fewer than 1.1 million residents as of 2020, but it ...

and

Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

. The former capital of Alaska,

Sitka

russian: Ситка

, native_name_lang = tli

, settlement_type = Consolidated city-borough

, image_skyline = File:Sitka 84 Elev 135.jpg

, image_caption = Downtown Sitka in 1984

, image_size ...

, is the largest U.S. city by area.

What is now Alaska has been home to various indigenous peoples for thousands of years; it is widely believed that the region served as

the entry point for the initial settlement of North America by way of the

Bering land bridge

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 72 degrees north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south by the tip of ...

. The

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

was the first to actively

colonize

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

the area beginning in the 18th century, eventually establishing

Russian America

Russian America (russian: Русская Америка, Russkaya Amerika) was the name for the Russian Empire's colonial possessions in North America from 1799 to 1867. It consisted mostly of present-day Alaska in the United States, but a ...

, which spanned most of the current state. The expense and logistical difficulty of maintaining this distant possession prompted

its sale to the U.S. in 1867 for

US$

The United States dollar (symbol: $; code: USD; also abbreviated US$ or U.S. Dollar, to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, American dollar, or colloquially buck) is the official ...

7.2 million (equivalent to $ million in ), or approximately two cents per acre ($4.74/km

2). The area went through several administrative changes before becoming organized as a

territory

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

on May 11, 1912. It was admitted as the 49th state of the U.S. on January 3, 1959.

While it has one of the smallest state economies in the country, Alaska's

per capita income is among the highest, owing to a diversified economy dominated by

fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from stocked bodies of water such as ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. Fishing techniques inclu ...

,

natural gas

Natural gas (also called fossil gas or simply gas) is a naturally occurring mixture of gaseous hydrocarbons consisting primarily of methane in addition to various smaller amounts of other higher alkanes. Low levels of trace gases like carbo ...

, and

oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

, all of which it has in abundance.

U.S. Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is the ...

bases and

tourism

Tourism is travel for pleasure or business; also the theory and practice of touring, the business of attracting, accommodating, and entertaining tourists, and the business of operating tours. The World Tourism Organization defines tourism mor ...

are also a significant part of the

economy

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the ...

; more than half the state is federally owned public land, including a multitude of

national forests,

national parks

A national park is a natural park in use for conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or owns. Although individua ...

, and

wildlife refuges

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or ...

.

The

indigenous population

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

of Alaska is proportionally the highest of any U.S. state, at over 15 percent. Close to two dozen native languages are spoken, and Alaskan Natives exercise considerable influence in local and state politics.

Etymology

The name "Alaska" ( rus, Аля́ска, r=Alyáska) was introduced in the

Russian colonial period when it was used to refer to the

Alaska Peninsula. It was derived from an

Aleut-language idiom, , meaning "the mainland" or, more literally, "the object towards which the action of the sea is directed".

[, at pp. 49 (Alaxsxi-x = mainland Alaska), 50 (''alagu-x'' = ''sea''), 508 (''-gi'' = suffix, ''object of its action'').] It is also known as , the "great land", an

Aleut

The Aleuts ( ; russian: Алеуты, Aleuty) are the indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands, which are located between the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. Both the Aleut people and the islands are politically divided between the ...

word that was derived from the same root.

History

Pre-colonization

Numerous indigenous peoples occupied Alaska for thousands of years before the arrival of European peoples to the area. Linguistic and DNA studies done here have provided evidence for the settlement of North America by way of the

Bering land bridge

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 72 degrees north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south by the tip of ...

. At the

Upward Sun River site

The Upward Sun River site, or Xaasaa Na’, is a Late Pleistocene archaeological site associated with the Paleo-Arctic tradition, located in the Tanana River Valley, Alaska. Dated to around 11,500 BP, Upward Sun River is the site of the oldest ...

in the

Tanana Valley

The Tanana Valley is a lowland region in central Alaska in the United States, on the north side of the Alaska Range, where the Tanana River emerges from the mountains. Traditional inhabitants of the valley are Tanana Athabaskans of Alaskan Athab ...

in Alaska, remains of a six-week-old infant were found. The baby's DNA showed that she belonged to a population that was genetically separate from other native groups present elsewhere in the

New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

at the end of the

Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was finally confirmed in ...

. Ben Potter, the

University of Alaska Fairbanks

The University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF or Alaska) is a public land-grant research university in College, Alaska, a suburb of Fairbanks. It is the flagship campus of the University of Alaska system. UAF was established in 1917 and opened for c ...

archaeologist who unearthed the remains at the Upward Sun River site in 2013, named this new group

Ancient Beringians.

The

Tlingit people

The Tlingit ( or ; also spelled Tlinkit) are indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America. Their language is the Tlingit language (natively , pronounced ), developed a society with a

matrilineal

Matrilineality is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage – and which can involve the inheritance ...

kinship system of property inheritance and descent in what is today Southeast Alaska, along with parts of

British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

and the

Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

. Also in Southeast were the

Haida, now well known for their unique arts. The

Tsimshian

The Tsimshian (; tsi, Ts’msyan or Tsm'syen) are an Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Their communities are mostly in coastal British Columbia in Terrace and Prince Rupert, and Metlakatla, Alaska on Annette Island, the only r ...

people came to Alaska from British Columbia in 1887, when President

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

, and later the U.S. Congress, granted them permission to settle on

Annette Island and found the town of

Metlakatla. All three of these peoples, as well as other

indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, experienced

smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

outbreaks from the late 18th through the mid-19th century, with the most devastating

epidemics

An epidemic (from Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics of infectious d ...

occurring in the 1830s and 1860s, resulting in high fatalities and social disruption.

The Aleutian Islands are still home to the

Aleut people

The Aleuts ( ; russian: Алеуты, Aleuty) are the indigenous people of the Aleutian Islands, which are located between the North Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea. Both the Aleut people and the islands are politically divided between th ...

's seafaring society, although they were the first Native Alaskans to be exploited by the Russians. Western and Southwestern Alaska are home to the

Yup'ik

The Yup'ik or Yupiaq (sg & pl) and Yupiit or Yupiat (pl), also Central Alaskan Yup'ik, Central Yup'ik, Alaskan Yup'ik ( own name ''Yup'ik'' sg ''Yupiik'' dual ''Yupiit'' pl; russian: Юпики центральной Аляски), are an I ...

, while their cousins the

Alutiiq ~ Sugpiaq live in what is now Southcentral Alaska. The

Gwich'in people of the northern Interior region are

Athabaskan and primarily known today for their dependence on the caribou within the much-contested

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR or Arctic Refuge) is a national wildlife refuge in northeastern Alaska, United States on traditional Gwich'in lands. It consists of in the Alaska North Slope region. It is the largest national wildli ...

. The North Slope and

Little Diomede Island

Little Diomede Island or “Yesterday Isle” ( ik, Iŋaliq, formerly known as Krusenstern Island, are occupied by the widespread

Inupiat people.

Colonization

Some researchers believe the first Russian settlement in Alaska was established in the 17th century. According to this hypothesis, in 1648 several

koches of

Semyon Dezhnyov

Semyon Ivanovich Dezhnyov ( rus, Семён Ива́нович Дежнёв, p=sʲɪˈmʲɵn ɪˈvanəvʲɪtɕ dʲɪˈʐnʲɵf; sometimes spelled Dezhnyov; c. 1605 – 1673) was a Russian explorer of Siberia and the first European to sail through t ...

's expedition came ashore in Alaska by storm and founded this settlement. This hypothesis is based on the testimony of

Chukchi geographer Nikolai Daurkin, who had visited Alaska in 1764–1765 and who had reported on a village on the Kheuveren River, populated by "bearded men" who "pray to the

icons

An icon () is a religious work of art, most commonly a painting, in the cultures of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Catholic churches. They are not simply artworks; "an icon is a sacred image used in religious devotion". The most c ...

". Some modern researchers associate Kheuveren with

Koyuk River.

The first European vessel to reach Alaska is generally held to be the ''St. Gabriel'' under the authority of the surveyor

M. S. Gvozdev and assistant navigator

I. Fyodorov on August 21, 1732, during an expedition of Siberian Cossack A. F. Shestakov and Russian explorer

Dmitry Pavlutsky Dmitry Ivanovich Pavlutsky (russian: Дмитрий Иванович Павлуцкий; died 21 March 1747) was a Russian polar explorer and leader of military expeditions in Chukotka, best known for his campaigns of genocide against the indigenou ...

(1729–1735). Another European contact with Alaska occurred in 1741, when

Vitus Bering

Vitus Jonassen Bering (baptised 5 August 1681 – 19 December 1741),All dates are here given in the Julian calendar, which was in use throughout Russia at the time. also known as Ivan Ivanovich Bering, was a Danish cartographer and explorer in ...

led an

expedition for the Russian Navy aboard the ''St. Peter''. After his crew returned to Russia with

sea otter pelts judged to be the finest fur in the world, small associations of

fur traders began to sail from the shores of Siberia toward the Aleutian Islands. The first permanent European settlement was founded in 1784.

Between 1774 and 1800,

Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

sent several

expeditions to Alaska to assert its claim over the Pacific Northwest. In 1789, a Spanish settlement and

fort

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

were built in

Nootka Sound

, image = Morning on Nootka Sound.jpg

, image_size = 250px

, alt =

, caption = Clouds over Nootka Sound

, image_bathymetry =

, alt_bathymetry =

, caption_bathymetry = Map of Nootka So ...

. These expeditions gave names to places such as

Valdez,

Bucareli Sound, and

Cordova. Later, the

Russian-American Company

The Russian-American Company Under the High Patronage of His Imperial Majesty (russian: Под высочайшим Его Императорского Величества покровительством Российская-Американс� ...

carried out an expanded colonization program during the early-to-mid-19th century.

Sitka

russian: Ситка

, native_name_lang = tli

, settlement_type = Consolidated city-borough

, image_skyline = File:Sitka 84 Elev 135.jpg

, image_caption = Downtown Sitka in 1984

, image_size ...

, renamed

New Archangel

russian: Ситка

, native_name_lang = tli

, settlement_type = Consolidated city-borough

, image_skyline = File:Sitka 84 Elev 135.jpg

, image_caption = Downtown Sitka in 1984

, image_size ...

from 1804 to 1867, on

Baranof Island

Baranof Island is an island in the northern Alexander Archipelago in the Alaska Panhandle, in Alaska. The name Baranof was given in 1805 by Imperial Russian Navy captain U. F. Lisianski to honor Alexander Andreyevich Baranov. It was called Sh ...

in the

Alexander Archipelago

The Alexander Archipelago (russian: Архипелаг Александра) is a long archipelago (group of islands) in North America lying off the southeastern coast of Alaska. It contains about 1,100 islands, the tops of submerged coastal m ...

in what is now

Southeast Alaska, became the capital of

Russian America

Russian America (russian: Русская Америка, Russkaya Amerika) was the name for the Russian Empire's colonial possessions in North America from 1799 to 1867. It consisted mostly of present-day Alaska in the United States, but a ...

. It remained the capital after the colony was transferred to the United States. The Russians never fully colonized Alaska, and the colony was never very profitable. Evidence of Russian settlement in names and churches survive throughout southeastern Alaska.

William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

, the 24th

United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

, negotiated the

Alaska Purchase

The Alaska Purchase (russian: Продажа Аляски, Prodazha Alyaski, Sale of Alaska) was the United States' acquisition of Alaska from the Russian Empire. Alaska was formally transferred to the United States on October 18, 1867, through a ...

(also known as Seward's Folly) with the Russians in 1867 for $7.2 million. Russia's contemporary ruler

Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East and South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" in the European medieval sense of the ter ...

Alexander II, the

Emperor of the Russian Empire

The emperor or empress of all the Russias or All Russia, ''Imperator Vserossiyskiy'', ''Imperatritsa Vserossiyskaya'' (often titled Tsar or Tsarina/Tsaritsa) was the monarch of the Russian Empire.

The title originated in connection with Russia' ...

,

King of Poland and

Grand Duke of Finland, also planned the sale; the purchase was made on March 30, 1867. Six months later the commissioners arrived in Sitka and the formal transfer was arranged; the formal flag-raising took place at Fort Sitka on October 18, 1867. In the ceremony 250 uniformed U.S. soldiers marched to the governor's house at "Castle Hill", where the Russian troops lowered the Russian flag and the U.S. flag was raised. This event is celebrated as

Alaska Day

Alaska Day (russian: День Аляски) is a legal holiday in the U.S. state of Alaska, observed on October 18. It is the anniversary of the formal transfer of territories in present-day Alaska from the Russian Empire to the United States, ...

, a legal holiday on October 18.

Alaska was loosely governed by the military initially, and was administered as a

district

A district is a type of administrative division that, in some countries, is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or county, counties, several municipality, municipa ...

starting in 1884, with a governor appointed by the United States president. A federal

district court was headquartered in Sitka. For most of Alaska's first decade under the United States flag, Sitka was the only community inhabited by American settlers. They organized a "provisional city government", which was Alaska's first municipal government, but not in a legal sense. Legislation allowing Alaskan communities to legally

incorporate as cities did not come about until 1900, and

home rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

for cities was extremely limited or unavailable until statehood took effect in 1959.

Alaska as an incorporated U.S. territory

Starting in the 1890s and stretching in some places to the early 1910s, gold rushes in Alaska and the nearby

Yukon Territory

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

brought thousands of miners and settlers to Alaska. Alaska was officially incorporated as an organized territory in 1912. Alaska's capital, which had been in

Sitka

russian: Ситка

, native_name_lang = tli

, settlement_type = Consolidated city-borough

, image_skyline = File:Sitka 84 Elev 135.jpg

, image_caption = Downtown Sitka in 1984

, image_size ...

until 1906, was moved north to

Juneau

The City and Borough of Juneau, more commonly known simply as Juneau ( ; tli, Dzánti K'ihéeni ), is the capital city of the state of Alaska. Located in the Gastineau Channel and the Alaskan panhandle, it is a unified municipality and the s ...

. Construction of the

Alaska Governor's Mansion

The Alaska Governor's Mansion, located at 716 Calhoun Avenue in Juneau, Alaska, is the official residence of the governor of Alaska, the first spouse of Alaska, and their families. It was designed by James Knox Taylor. The Governor's Mansion w ...

began that same year. European immigrants from Norway and Sweden also settled in southeast Alaska, where they entered the fishing and logging industries.

During

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, the

Aleutian Islands Campaign focused on

Attu,

Agattu

Agattu ( ale, Angatux̂; russian: Агатту) is an island in Alaska, part of the Near Islands in the western end of the Aleutian Islands. With a land area of Agattu is one of the largest uninhabited islands in the Aleutians. It is the sec ...

and

Kiska

Kiska ( ale, Qisxa, russian: Кыска) is one of the Rat Islands, a group of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. It is about long and varies in width from . It is part of Aleutian Islands Wilderness and as such, special permission is require ...

, all of which were occupied by the

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan, 1947 constitu ...

. During the Japanese occupation, a white American civilian and two

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

personnel were killed at Attu and Kiska respectively, and nearly a total of 50 Aleut civilians and eight sailors were interned in Japan. About half of the Aleuts died during the period of internment.

Unalaska

Unalaska ( ale, Iluulux̂; russian: Уналашка) is the chief center of population in the Aleutian Islands. The city is in the Aleutians West Census Area, a regional component of the Unorganized Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. Unalaska ...

/

Dutch Harbor

Dutch Harbor is a harbor on Amaknak Island in Unalaska, Alaska. It was the location of the Battle of Dutch Harbor in June 1942, and was one of the few sites in the United States to be subjected to aerial bombardment by a foreign power during ...

and

Adak became significant bases for the

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

,

United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

and

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

. The United States

Lend-Lease program involved flying American warplanes through Canada to Fairbanks and then Nome; Soviet pilots took possession of these aircraft, ferrying them to fight the German invasion of the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. The construction of military bases contributed to the population growth of some Alaskan cities.

Statehood

Statehood for Alaska was an important cause of

James Wickersham

James Wickersham (August 24, 1857 – October 24, 1939) was a district judge for Alaska, appointed by U.S. President William McKinley to the Third Judicial District in 1900. He resigned his post in 1908 and was subsequently elected as Alaska ...

early in his tenure as a congressional delegate. Decades later, the statehood movement gained its first real momentum following a territorial referendum in 1946. The Alaska Statehood Committee and Alaska's Constitutional Convention would soon follow. Statehood supporters also found themselves fighting major battles against political foes, mostly in the U.S. Congress but also within Alaska. Statehood was approved by the U.S. Congress on July 7, 1958; Alaska was officially proclaimed a state on January 3, 1959.

Good Friday earthquake

On March 27, 1964, the massive

Good Friday earthquake

The 1964 Alaskan earthquake, also known as the Great Alaskan earthquake and Good Friday earthquake, occurred at 5:36 PM AKST on Good Friday, March 27. killed 133 people and destroyed several villages and portions of large coastal communities, mainly by the resultant

tsunamis

A tsunami ( ; from ja, 津波, lit=harbour wave, ) is a series of waves in a water body caused by the displacement of a large volume of water, generally in an ocean or a large lake. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and other underwater expl ...

and landslides. It was the

second-most-powerful earthquake in recorded history, with a

moment magnitude

The moment magnitude scale (MMS; denoted explicitly with or Mw, and generally implied with use of a single M for magnitude) is a measure of an earthquake's magnitude ("size" or strength) based on its seismic moment. It was defined in a 1979 pape ...

of 9.2 (more than a thousand times as powerful as the

1989 San Francisco earthquake

The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake occurred on California's Central Coast on October 17 at local time. The shock was centered in The Forest of Nisene Marks State Park in Santa Cruz County, approximately northeast of Santa Cruz on a section of ...

). The time of day (5:36 pm), time of year (spring) and location of the

epicenter

The epicenter, epicentre () or epicentrum in seismology is the point on the Earth's surface directly above a hypocenter or focus, the point where an earthquake or an underground explosion originates.

Surface damage

Before the instrumental pe ...

were all cited as factors in potentially sparing thousands of lives, particularly in Anchorage.

Lasting four minutes and thirty-eight seconds, the magnitude 9.2

megathrust earthquake

Megathrust earthquakes occur at convergent plate boundaries, where one tectonic plate is forced underneath another. The earthquakes are caused by slip along the thrust fault that forms the contact between the two plates. These interplate earthqu ...

remains the most powerful earthquake recorded in

North American history, and the second

most powerful earthquake recorded in world history. of fault ruptured at once and moved up to , releasing about 500 years of stress buildup.

Soil liquefaction, fissures, landslides, and other ground failures caused major structural damage in several communities and much damage to property.

Anchorage sustained great destruction or damage to many inadequately

earthquake-engineered houses, buildings, and infrastructure (paved streets, sidewalks, water and sewer mains, electrical systems, and other man-made equipment), particularly in the several landslide zones along

Knik Arm. southwest, some areas near

Kodiak were permanently raised by . Southeast of Anchorage, areas around the head of

Turnagain Arm

Turnagain Arm ( Dena'ina: ''Tutl'uh'') is a waterway into the northwestern part of the Gulf of Alaska. It is one of two narrow branches at the north end of Cook Inlet, the other being Knik Arm. Turnagain is subject to climate extremes and large ti ...

near

Girdwood and

Portage dropped as much as , requiring reconstruction and fill to raise the

Seward Highway

The Seward Highway is a highway in the U.S. state of Alaska that extends from Seward to Anchorage. It was completed in 1951 and runs through the scenic Kenai Peninsula, Chugach National Forest, Turnagain Arm, and Kenai Mountains. The Seward H ...

above the new high

tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide tables ...

mark.

In

Prince William Sound

Prince William Sound ( Sugpiaq: ''Suungaaciq'') is a sound of the Gulf of Alaska on the south coast of the U.S. state of Alaska. It is located on the east side of the Kenai Peninsula. Its largest port is Valdez, at the southern terminus of the T ...

,

Port Valdez

Port Valdez is a fjord of Prince William Sound in Alaska, United States. Its main settlement is Valdez, located near the head of the bay. It marks the southern terminus of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System. The bay is oriented east-west and it ...

suffered a massive underwater landslide, resulting in the deaths of 32 people between the collapse of the

Valdez city harbor and docks, and inside the ship that was docked there at the time. Nearby, a tsunami destroyed the village of

Chenega, killing 23 of the 68 people who lived there; survivors out-ran the wave, climbing to high ground. Post-quake tsunamis severely affected

Whittier,

Seward,

Kodiak, and other Alaskan communities, as well as people and property in

British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

,

Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

,

Oregon

Oregon () is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of its eastern boundary with Idaho. T ...

, and

California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

. Tsunamis also caused damage in

Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only state ...

and

Japan. Evidence of motion directly related to the earthquake was also reported from

Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

and

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

.

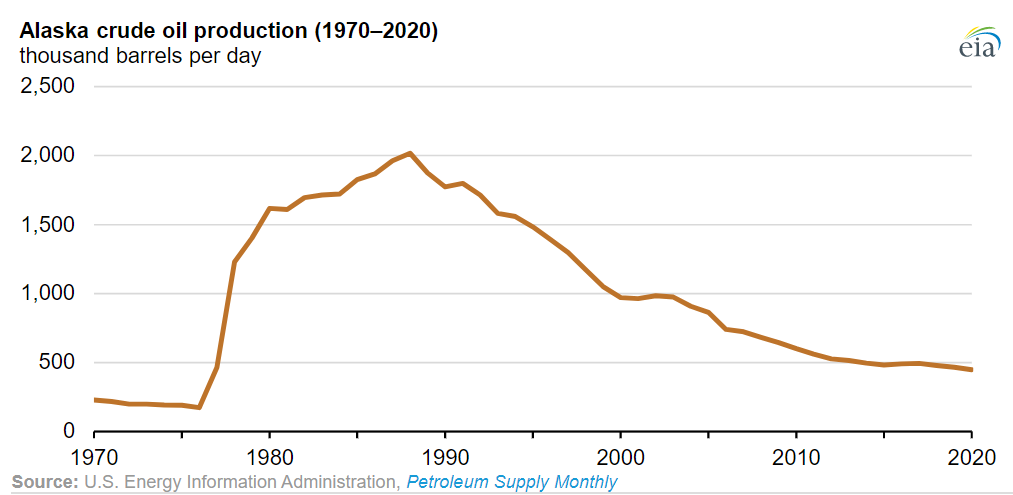

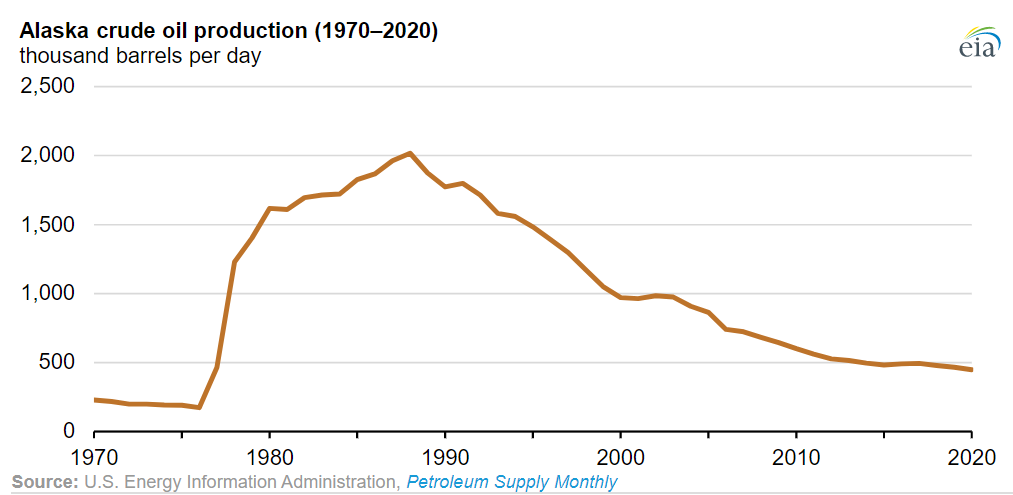

Alaska oil boom

The 1968 discovery of oil at

Prudhoe Bay

Prudhoe Bay is a census-designated place (CDP) located in North Slope Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. As of the 2010 census, the population of the CDP was 2,174 people, up from just five residents in the 2000 census; however, at any give ...

and the 1977 completion of the

Trans-Alaska Pipeline System

The Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) is an oil transportation system spanning Alaska, including the trans-Alaska crude-oil pipeline, 11 pump stations, several hundred miles of feeder pipelines, and the Valdez Marine Terminal. TAPS is one o ...

led to an oil boom. Royalty revenues from oil have funded large state budgets from 1980 onward.

In 1989, the ''

Exxon Valdez

''Oriental Nicety'', formerly ''Exxon Valdez'', ''Exxon Mediterranean'', ''SeaRiver Mediterranean'', ''S/R Mediterranean'', ''Mediterranean'', and ''Dong Fang Ocean'', was an oil tanker that gained notoriety after running aground in Prince Wi ...

'' hit a reef in the

Prince William Sound

Prince William Sound ( Sugpiaq: ''Suungaaciq'') is a sound of the Gulf of Alaska on the south coast of the U.S. state of Alaska. It is located on the east side of the Kenai Peninsula. Its largest port is Valdez, at the southern terminus of the T ...

,

spilling more than of crude oil over of coastline. Today, the battle between philosophies of development and conservation is seen in the contentious debate over oil drilling in the

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR or Arctic Refuge) is a national wildlife refuge in northeastern Alaska, United States on traditional Gwich'in lands. It consists of in the Alaska North Slope region. It is the largest national wildli ...

and the proposed

Pebble Mine.

Geography

Located at the northwest corner of

North America, Alaska is the northernmost and westernmost state in the United States, but also has the most easterly longitude in the United States because the

Aleutian Islands

The Aleutian Islands (; ; ale, Unangam Tanangin,”Land of the Aleuts", possibly from Chukchi ''aliat'', "island"), also called the Aleut Islands or Aleutic Islands and known before 1867 as the Catherine Archipelago, are a chain of 14 large v ...

extend into the

Eastern Hemisphere. Alaska is the only non-

contiguous

Contiguity or contiguous may refer to:

*Contiguous data storage, in computer science

*Contiguity (probability theory)

*Contiguity (psychology)

*Contiguous distribution of species, in biogeography

*Geographic contiguity of territorial land

*Contigu ...

U.S. state on continental North America; about of

British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

(Canada) separates Alaska from

Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

. It is technically part of the

continental U.S., but is sometimes not included in colloquial use; Alaska is not part of the

contiguous U.S., often called

"the Lower 48". The capital city,

Juneau

The City and Borough of Juneau, more commonly known simply as Juneau ( ; tli, Dzánti K'ihéeni ), is the capital city of the state of Alaska. Located in the Gastineau Channel and the Alaskan panhandle, it is a unified municipality and the s ...

, is situated on the mainland of the North American continent but is not connected by road to the rest of the North American highway system.

The state is bordered by Canada's

Yukon

Yukon (; ; formerly called Yukon Territory and also referred to as the Yukon) is the smallest and westernmost of Canada's three territories. It also is the second-least populated province or territory in Canada, with a population of 43,964 as ...

and

British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

to the east (making it the only state to only border a

Canadian territory); the

Gulf of Alaska

The Gulf of Alaska (Tlingit: ''Yéil T'ooch’'') is an arm of the Pacific Ocean defined by the curve of the southern coast of Alaska, stretching from the Alaska Peninsula and Kodiak Island in the west to the Alexander Archipelago in the east ...

and the Pacific Ocean to the south and southwest; the

Bering Sea,

Bering Strait, and

Chukchi Sea to the west; and the Arctic Ocean to the north. Alaska's territorial waters touch Russia's territorial waters in the Bering Strait, as the Russian

Big Diomede Island and Alaskan

Little Diomede Island

Little Diomede Island or “Yesterday Isle” ( ik, Iŋaliq, formerly known as Krusenstern Island, are only apart. Alaska has a longer coastline than all the other U.S. states combined.

At in total area, Alaska is by far the largest state in the United States. Alaska is more than twice the size of the second-largest U.S. state (Texas), and it is larger than the next three largest states (Texas, California, and Montana) combined. Alaska is the seventh

largest subnational division in the world, and if it was an independent nation would be the 16th largest country in the world, as it is larger than

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

.

With its myriad islands, Alaska has nearly of tidal shoreline. The Aleutian Islands chain extends west from the southern tip of the

Alaska Peninsula. Many active

volcano

A volcano is a rupture in the Crust (geology), crust of a Planet#Planetary-mass objects, planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and volcanic gas, gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Ear ...

es are found in the Aleutians and in coastal regions.

Unimak Island

Unimak Island ( ale, Unimax, russian: Унимак) is the largest island in the Aleutian Islands chain of the U.S. state of Alaska.

Geography

It is the easternmost island in the Aleutians and, with an area of , the ninth largest island in the ...

, for example, is home to

Mount Shishaldin

Shishaldin Volcano, or Mount Shishaldin (), is a moderately active volcano on Unimak Island in the Aleutian Islands chain of Alaska in the United States. , which is an occasionally smoldering volcano that rises to above the North Pacific. The chain of volcanoes extends to

Mount Spurr

Mount Spurr ( Dena'ina: ''K'idazq'eni'') is a stratovolcano in the Aleutian Arc of Alaska, named after United States Geological Survey geologist and explorer Josiah Edward Spurr, who led an expedition to the area in 1898. The Alaska Volcano Obse ...

, west of Anchorage on the mainland. Geologists have identified Alaska as part of

Wrangellia, a large region consisting of multiple states and Canadian provinces in the

Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Tho ...

, which is actively undergoing

continent building.

One of the world's largest tides occurs in

Turnagain Arm

Turnagain Arm ( Dena'ina: ''Tutl'uh'') is a waterway into the northwestern part of the Gulf of Alaska. It is one of two narrow branches at the north end of Cook Inlet, the other being Knik Arm. Turnagain is subject to climate extremes and large ti ...

, just south of Anchorage, where tidal differences can be more than .

Alaska has more than three million lakes.

Marshland

A marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous rather than woody plant species.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p Marshes can often be found at ...

s and wetland

permafrost cover (mostly in northern, western and southwest flatlands). Glacier ice covers about of Alaska. The

Bering Glacier

Bering Glacier is a glacier in the U.S. state of Alaska. It currently terminates in Vitus Lake south of Alaska's Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, about from the Gulf of Alaska. Combined with the Bagley Icefield, where the snow that feeds the gl ...

is the largest glacier in North America, covering alone.

Regions

There are no officially defined borders demarcating the various regions of Alaska, but there are six widely accepted regions:

South Central

The most populous region of Alaska, containing

Anchorage, the

Matanuska-Susitna Valley

Matanuska-Susitna Valley () (known locally as the Mat-Su or The Valley) is an area in Southcentral Alaska south of the Alaska Range about north of Anchorage, Alaska.

It is known for the world record sized cabbages and other vegetables displaye ...

and the

Kenai Peninsula

The Kenai Peninsula ( Dena'ina: ''Yaghenen'') is a large peninsula jutting from the coast of Southcentral Alaska. The name Kenai (, ) is derived from the word "Kenaitze" or "Kenaitze Indian Tribe", the name of the Native Athabascan Alaskan trib ...

. Rural, mostly unpopulated areas south of the

Alaska Range

The Alaska Range is a relatively narrow, 600-mile-long (950 km) mountain range in the southcentral region of the U.S. state of Alaska, from Lake Clark at its southwest endSources differ as to the exact delineation of the Alaska Range. ThBoar ...

and west of the

Wrangell Mountains

The Wrangell Mountains are a high mountain range of eastern Alaska in the United States. Much of the range is included in Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park and Preserve. The Wrangell Mountains are almost entirely volcanic in origin, and they i ...

also fall within the definition of South Central, as do the

Prince William Sound

Prince William Sound ( Sugpiaq: ''Suungaaciq'') is a sound of the Gulf of Alaska on the south coast of the U.S. state of Alaska. It is located on the east side of the Kenai Peninsula. Its largest port is Valdez, at the southern terminus of the T ...

area and the communities of

Cordova and

Valdez.

Southeast

Also referred to as the Panhandle or

Inside Passage

The Inside Passage (french: Passage Intérieur) is a coastal route for ships and boats along a network of passages which weave through the islands on the Pacific Northwest coast of the North American Fjordland. The route extends from southeaste ...

, this is the region of Alaska closest to the contiguous states. As such, this was where most of the initial non-indigenous settlement occurred in the years following the

Alaska Purchase

The Alaska Purchase (russian: Продажа Аляски, Prodazha Alyaski, Sale of Alaska) was the United States' acquisition of Alaska from the Russian Empire. Alaska was formally transferred to the United States on October 18, 1867, through a ...

. The region is dominated by the

Alexander Archipelago

The Alexander Archipelago (russian: Архипелаг Александра) is a long archipelago (group of islands) in North America lying off the southeastern coast of Alaska. It contains about 1,100 islands, the tops of submerged coastal m ...

as well as the

Tongass National Forest

The Tongass National Forest () in Southeast Alaska is the largest U.S. National Forest at . Most of its area is temperate rain forest and is remote enough to be home to many species of endangered and rare flora and fauna. The Tongass, which is ...

, the largest national forest in the United States. It contains the state capital

Juneau

The City and Borough of Juneau, more commonly known simply as Juneau ( ; tli, Dzánti K'ihéeni ), is the capital city of the state of Alaska. Located in the Gastineau Channel and the Alaskan panhandle, it is a unified municipality and the s ...

, the former capital

Sitka

russian: Ситка

, native_name_lang = tli

, settlement_type = Consolidated city-borough

, image_skyline = File:Sitka 84 Elev 135.jpg

, image_caption = Downtown Sitka in 1984

, image_size ...

, and

Ketchikan

Ketchikan ( ; tli, Kichx̱áan) is a city in and the borough seat of the Ketchikan Gateway Borough of Alaska. It is the state's southeasternmost major settlement. Downtown Ketchikan is a National Historic District.

With a population at the 20 ...

, at one time Alaska's largest city. The

Alaska Marine Highway

The Alaska Marine Highway (AMH) or the Alaska Marine Highway System (AMHS) is a ferry service operated by the U.S. state of Alaska. It has its headquarters in Ketchikan, Alaska.

The Alaska Marine Highway System operates along the south-central ...

provides a vital surface transportation link throughout the area and country, as only three communities (

Haines,

Hyder and

Skagway

The Municipality and Borough of Skagway is a first-class borough in Alaska on the Alaska Panhandle. As of the 2020 census, the population was 1,240, up from 968 in 2010. The population doubles in the summer tourist season in order to deal with ...

) enjoy direct connections to the contiguous North American road system.

Interior

The Interior is the largest region of Alaska; much of it is uninhabited wilderness.

Fairbanks is the only large city in the region.

Denali National Park and Preserve

Denali National Park and Preserve, formerly known as Mount McKinley National Park, is an American national park and preserve located in Interior Alaska, centered on Denali, the highest mountain in North America. The park and contiguous preserve ...

is located here.

Denali

Denali (; also known as Mount McKinley, its former official name) is the highest mountain peak in North America, with a summit elevation of above sea level. With a topographic prominence of and a topographic isolation of , Denali is the th ...

, formerly Mount McKinley, is the highest mountain in North America, and is also located here.

Southwest

Southwest Alaska is a sparsely inhabited region stretching some inland from the Bering Sea. Most of the population lives along the coast.

Kodiak Island

Kodiak Island ( Alutiiq: ''Qikertaq''), is a large island on the south coast of the U.S. state of Alaska, separated from the Alaska mainland by the Shelikof Strait. The largest island in the Kodiak Archipelago, Kodiak Island is the second la ...

is also located in Southwest. The massive

Yukon–Kuskokwim Delta

The Yukon–Kuskokwim Delta is a river delta located where the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers empty into the Bering Sea on the west coast of the U.S. state of Alaska. At approximately in size, it is one of the largest deltas in the world. It is lar ...

, one of the largest river deltas in the world, is here. Portions of the

Alaska Peninsula are considered part of Southwest, with the remaining portions included with the Aleutian Islands (see below).

North Slope

The North Slope is mostly

tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless mou ...

peppered with small villages. The area is known for its massive reserves of crude oil and contains both the

National Petroleum Reserve–Alaska

The National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska (NPRA) is an area of land on the Alaska North Slope owned by the United States federal government and managed by the Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management (BLM). It lies to the west of the ...

and the

Prudhoe Bay Oil Field

Prudhoe Bay Oil Field is a large oil field on Alaska's North Slope. It is the largest oil field in North America, covering and originally containing approximately of oil. . The city of

Utqiaġvik

Utqiagvik ( ik, Utqiaġvik; , , formerly known as Barrow ()) is the borough seat and largest city of the North Slope Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. Located north of the Arctic Circle, it is one of the northernmost cities and towns in the ...

, formerly known as Barrow, is the northernmost city in the United States and is located here. The

Northwest Arctic area, anchored by

Kotzebue

Kotzebue ( ) or Qikiqtaġruk ( , ) is a city in the Northwest Arctic Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. It is the borough's seat, by far its largest community and the economic and transportation hub of the subregion of Alaska encompassing t ...

and also containing the

Kobuk River

The Kobuk River (''Kuuvak'' in Iñupiaq) (also Kooak, Kowak, Kubuk, Kuvuk, or Putnam)

is a river located in the Arctic region of northwestern Alaska in the United States. It is approximately long. Draining a basin with an area of ,Brabets, T.P. ...

valley, is often regarded as being part of this region. However, the respective

Inupiat of the North Slope and of the Northwest Arctic seldom consider themselves to be one people.

Aleutian Islands

More than 300 small volcanic islands make up this chain, which stretches more than into the Pacific Ocean. Some of these islands fall in the Eastern Hemisphere, but the

International Date Line was drawn west of

180° to keep the whole state, and thus the entire North American continent, within the same legal day. Two of the islands,

Attu and

Kiska

Kiska ( ale, Qisxa, russian: Кыска) is one of the Rat Islands, a group of the Aleutian Islands of Alaska. It is about long and varies in width from . It is part of Aleutian Islands Wilderness and as such, special permission is require ...

, were occupied by Japanese forces during World War II.

Land ownership

According to an October 1998 report by the

United States Bureau of Land Management

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is an agency within the United States Department of the Interior responsible for administering federal lands. Headquartered in Washington DC, and with oversight over , it governs one eighth of the country's la ...

, approximately 65% of Alaska is owned and managed by the

U.S. federal government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fed ...

as public lands, including a multitude of

national forests, national parks, and

national wildlife refuges. Of these, the

Bureau of Land Management manages , or 23.8% of the state. The

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR or Arctic Refuge) is a national wildlife refuge in northeastern Alaska, United States on traditional Gwich'in lands. It consists of in the Alaska North Slope region. It is the largest national wildli ...

is managed by the

United States Fish and Wildlife Service

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS or FWS) is an agency within the United States Department of the Interior dedicated to the management of fish, wildlife, and natural habitats. The mission of the agency is "working with othe ...

. It is the world's largest wildlife refuge, comprising .

Of the remaining land area, the state of Alaska owns , its entitlement under the

Alaska Statehood Act

The Alaska Statehood Act () was a statehood admission law, introduced by Delegate E.L. Bob Bartlett and signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on July 7, 1958, allowing Alaska to become the 49th U.S. state on January 3, 1959. The law was the ...

. A portion of that acreage is occasionally ceded to the organized boroughs presented above, under the statutory provisions pertaining to newly formed boroughs. Smaller portions are set aside for rural subdivisions and other homesteading-related opportunities. These are not very popular due to the often remote and roadless locations. The

University of Alaska, as a

land grant university

A land-grant university (also called land-grant college or land-grant institution) is an institution of higher education in the United States designated by a state to receive the benefits of the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890.

Signed by Abraha ...

, also owns substantial acreage which it manages independently.

Another are owned by 12 regional, and scores of local, Native corporations created under the

Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on December 18, 1971, constituting at the time the largest land claims settlement in United States history. ANCSA was intended to resolve long-standing ...

(ANCSA) of 1971.

Regional Native corporation Doyon, Limited often promotes itself as the largest private landowner in Alaska in advertisements and other communications. Provisions of ANCSA allowing the corporations' land holdings to be sold on the open market starting in 1991 were repealed before they could take effect. Effectively, the corporations hold title (including subsurface title in many cases, a privilege denied to individual Alaskans) but cannot sell the land.

Individual Native allotments can be and are sold on the open market, however.

Various private interests own the remaining land, totaling about one percent of the state. Alaska is, by a large margin, the state with the smallest percentage of private land ownership when Native corporation holdings are excluded.

Alaska Heritage Resources Survey

The Alaska Heritage Resources Survey (AHRS) is a restricted

inventory of all reported

historic

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

and

prehistoric sites within the U.S. state of Alaska; it is maintained by the Office of History and Archaeology. The survey's inventory of cultural resources includes objects, structures, buildings, sites, districts, and travel ways, with a general provision that they are more than fifty years old. , more than 35,000 sites have been reported.

Cities, towns and boroughs

Alaska is not divided into

counties

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesChambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

, as most of the other U.S. states, but it is divided into ''

boroughs

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

In the Middle A ...

''. Delegates to the

Alaska Constitutional Convention

The Constitution of the State of Alaska was ratified on April 4, 1956 and took effect with Alaska's admission to the United States as a U.S. state on January 3, 1959.

History and background

The statehood movement

In the 1940s, the movement for ...

wanted to avoid the pitfalls of the traditional county system and adopted their own unique model. Many of the more densely populated parts of the state are part of Alaska's 16 boroughs, which function somewhat similarly to counties in other states. However, unlike county-equivalents in the other 49 states, the boroughs do not cover the entire land area of the state. The area not part of any borough is referred to as the

Unorganized Borough

The Unorganized Borough is composed of the portions of the U.S. state of Alaska which are not contained in any of its 19 organized boroughs. While referred to as the "Unorganized Borough," it is not a borough itself, as it forgoes that level of ...

.

The Unorganized Borough has no government of its own, but the

U.S. Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau (USCB), officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System, responsible for producing data about the American people and economy. The Census Bureau is part of the ...

in cooperation with the state divided the Unorganized Borough into 11

census areas solely for the purposes of statistical analysis and presentation. A ''recording district'' is a mechanism for management of the

public record

Public records are documents or pieces of information that are not considered confidential and generally pertain to the conduct of government.

For example, in California, when a couple fills out a marriage license application, they have the opti ...

in Alaska. The state is divided into 34 recording districts which are centrally administered under a state

recorder

Recorder or The Recorder may refer to:

Newspapers

* ''Indianapolis Recorder'', a weekly newspaper

* ''The Recorder'' (Massachusetts newspaper), a daily newspaper published in Greenfield, Massachusetts, US

* ''The Recorder'' (Port Pirie), a news ...

. All recording districts use the same acceptance criteria, fee schedule, etc., for accepting documents into the public record.

Whereas many U.S. states use a three-tiered system of decentralization—state/county/township—most of Alaska uses only two tiers—state/borough. Owing to the low population density, most of the land is located in the

Unorganized Borough

The Unorganized Borough is composed of the portions of the U.S. state of Alaska which are not contained in any of its 19 organized boroughs. While referred to as the "Unorganized Borough," it is not a borough itself, as it forgoes that level of ...

. As the name implies, it has no intermediate borough government but is administered directly by the state government. In 2000, 57.71% of Alaska's area has this status, with 13.05% of the population.

Anchorage merged the city government with the Greater Anchorage Area Borough in 1975 to form the Municipality of Anchorage, containing the city proper and the communities of Eagle River, Chugiak, Peters Creek, Girdwood, Bird, and Indian. Fairbanks has a separate borough (the

Fairbanks North Star Borough) and municipality (the City of Fairbanks).

The state's most populous city is

Anchorage, home to 291,247 people in 2020.

The richest

location in Alaska by per capita income is

Denali

Denali (; also known as Mount McKinley, its former official name) is the highest mountain peak in North America, with a summit elevation of above sea level. With a topographic prominence of and a topographic isolation of , Denali is the th ...

($42,245).

Yakutat City

The City and Borough of Yakutat (, ;

Tlingit: ''Yaakwdáat''; russian: Якутат) is a borough

in the U.S. state of Alaska and the name of a former city within it. The name in Tlingit is ''Yaakwdáat'' (meaning "the place where canoe ...

, Sitka, Juneau, and Anchorage are the four

largest cities in the U.S. by area.

Cities and census-designated places (by population)

As reflected in the

2020 United States census

The United States census of 2020 was the twenty-fourth decennial United States census. Census Day, the reference day used for the census, was April 1, 2020. Other than a pilot study during the 2000 census, this was the first U.S. census to of ...

, Alaska has a total of 355 incorporated cities and

census-designated place

A census-designated place (CDP) is a Place (United States Census Bureau), concentration of population defined by the United States Census Bureau for statistical purposes only.

CDPs have been used in each decennial census since 1980 as the count ...

s (CDPs).

[

] The tally of cities includes four unified municipalities, essentially the equivalent of a

consolidated city–county. The majority of these communities are located in the rural expanse of Alaska known as "

The Bush

"The bush" is a term mostly used in the English vernacular of Australia and New Zealand where it is largely synonymous with '' backwoods'' or ''hinterland'', referring to a natural undeveloped area. The fauna and flora contained within this a ...

" and are unconnected to that contiguous North American road network. The table at the bottom of this section lists about the 100 largest cities and census-designated places in Alaska, in population order.

Of Alaska's 2020 U.S. census population figure of 733,391, 16,655 people, or 2.27% of the population, did not live in an incorporated city or census-designated place.

Approximately three-quarters of that figure were people who live in urban and suburban neighborhoods on the outskirts of the city limits of Ketchikan, Kodiak, Palmer and Wasilla. CDPs have not been established for these areas by the United States Census Bureau, except that seven CDPs were established for the Ketchikan-area neighborhoods in the

1980 Census

The United States census of 1980, conducted by the Census Bureau, determined the resident population of the United States to be 226,545,805, an increase of 11.4 percent over the 203,184,772 persons enumerated during the 1970 census. It was th ...

(Clover Pass, Herring Cove, Ketchikan East, Mountain Point, North

Tongass Highway

Alaska Route 7 (abbreviated as AK-7) is a state highway in the Alaska Panhandle of the U.S. state of Alaska. It consists of four unconnected pieces, serving some of the Panhandle communities at which the Alaska Marine Highway ferries stop, and co ...

,

Pennock Island and

Saxman East), but have not been used since. The remaining population was scattered throughout Alaska, both within organized boroughs and in the Unorganized Borough, in largely remote areas.

Climate

The climate in south and southeastern Alaska is a mid-latitude

oceanic climate (

Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, notabl ...

: ''Cfb''), and a subarctic oceanic climate (Köppen ''Cfc'') in the northern parts. On an annual basis, the southeast is both the wettest and warmest part of Alaska with milder temperatures in the winter and high precipitation throughout the year. Juneau averages over of precipitation a year, and

Ketchikan

Ketchikan ( ; tli, Kichx̱áan) is a city in and the borough seat of the Ketchikan Gateway Borough of Alaska. It is the state's southeasternmost major settlement. Downtown Ketchikan is a National Historic District.

With a population at the 20 ...

averages over . This is also the only region in Alaska in which the average daytime high temperature is above freezing during the winter months.

The climate of

Anchorage and south central Alaska is mild by Alaskan standards due to the region's proximity to the seacoast. While the area gets less rain than southeast Alaska, it gets more snow, and days tend to be clearer. On average,

Anchorage receives of precipitation a year, with around of snow, although there are areas in the south central which receive far more snow. It is a subarctic climate (

Köppen: ''Dfc'') due to its brief, cool summers.

The climate of

western Alaska is determined in large part by the

Bering Sea and the

Gulf of Alaska

The Gulf of Alaska (Tlingit: ''Yéil T'ooch’'') is an arm of the Pacific Ocean defined by the curve of the southern coast of Alaska, stretching from the Alaska Peninsula and Kodiak Island in the west to the Alexander Archipelago in the east ...

. It is a subarctic oceanic climate in the southwest and a continental subarctic climate farther north. The temperature is somewhat moderate considering how far north the area is. This region has a tremendous amount of variety in precipitation. An area stretching from the northern side of the Seward Peninsula to the

Kobuk River

The Kobuk River (''Kuuvak'' in Iñupiaq) (also Kooak, Kowak, Kubuk, Kuvuk, or Putnam)

is a river located in the Arctic region of northwestern Alaska in the United States. It is approximately long. Draining a basin with an area of ,Brabets, T.P. ...

valley (i.e., the region around

Kotzebue Sound

Kotzebue Sound (russian: Залив Коцебу) is an arm of the Chukchi Sea in the western region of the U.S. state of Alaska. It is on the north side of the Seward Peninsula and bounded on the east by the Baldwin Peninsula. It is long and wi ...

) is technically a

desert, with portions receiving less than of precipitation annually. On the other extreme, some locations between

Dillingham and

Bethel average around of precipitation.

The climate of the interior of Alaska is subarctic. Some of the highest and lowest temperatures in Alaska occur around the area near

Fairbanks. The summers may have temperatures reaching into the 90s °F (the low-to-mid 30s °C), while in the winter, the temperature can fall below . Precipitation is sparse in the Interior, often less than a year, but what precipitation falls in the winter tends to stay the entire winter.

The highest and lowest recorded temperatures in Alaska are both in the Interior. The highest is in

Fort Yukon

Fort Yukon (''Gwichyaa Zheh'' in Gwich'in) is a city in the Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area in the U.S. state of Alaska, straddling the Arctic Circle. The population, predominantly Gwich'in Alaska Natives, was 583 at the 2010 census, down from 595 ...

(which is just inside the arctic circle) on June 27, 1915,

making Alaska tied with Hawaii as the state with the lowest high temperature in the United States. The lowest official Alaska temperature is in

Prospect Creek on January 23, 1971,

one degree above the lowest temperature recorded in continental North America (in

Snag, Yukon, Canada).

The climate in the extreme north of Alaska is

Arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenland), Finland, Iceland, N ...

(

Köppen: ''ET'') with long, very cold winters and short, cool summers. Even in July, the average low temperature in

Utqiaġvik

Utqiagvik ( ik, Utqiaġvik; , , formerly known as Barrow ()) is the borough seat and largest city of the North Slope Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. Located north of the Arctic Circle, it is one of the northernmost cities and towns in the ...

is . Precipitation is light in this part of Alaska, with many places averaging less than per year, mostly as snow which stays on the ground almost the entire year.

Demographics

The

United States Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau (USCB), officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System, responsible for producing data about the American people and economy. The Census Bureau is part of t ...

found in the

2020 United States census

The United States census of 2020 was the twenty-fourth decennial United States census. Census Day, the reference day used for the census, was April 1, 2020. Other than a pilot study during the 2000 census, this was the first U.S. census to of ...

that the population of Alaska was 736,081 on April 1, 2020, a 3.6% increase since the

2010 United States census

The United States census of 2010 was the twenty-third United States national census. National Census Day, the reference day used for the census, was April 1, 2010. The census was taken via mail-in citizen self-reporting, with enumerators servi ...

.

According to the 2010 United States census, the U.S. state of Alaska had a population of 710,231, increasing from 626,932 at the 2000 U.S. census.

In 2010, Alaska ranked as the 47th state by population, ahead of

North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the indigenous Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north and by the U.S. states of Minnesota to the east, So ...

,

Vermont

Vermont () is a state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to ...

, and

Wyoming

Wyoming () is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the southwest, and Colorado to the s ...