Ai Khanoum on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ai-Khanoum (, meaning ''Lady Moon''; uz, Oyxonim) is the

Based on ceramic data gathered at the site, it is likely that Ai-Khanoum was expanded in stages. The first stage would have begun under one of the first rulers of the

Based on ceramic data gathered at the site, it is likely that Ai-Khanoum was expanded in stages. The first stage would have begun under one of the first rulers of the  Although the first assault led to the end of Hellenistic rule in the city, Ai-Khanoum continued to be inhabited; it remains unknown whether this reoccupation was effected by Greco-Bactrian survivors or nomadic invaders. During this time, public buildings such as the palace and sanctuary were repurposed as residential dwellings, and the city maintained some semblance of normality: some sort of authority, possibly cultish in origin, encouraged the inhabitants to reuse the raw

Although the first assault led to the end of Hellenistic rule in the city, Ai-Khanoum continued to be inhabited; it remains unknown whether this reoccupation was effected by Greco-Bactrian survivors or nomadic invaders. During this time, public buildings such as the palace and sanctuary were repurposed as residential dwellings, and the city maintained some semblance of normality: some sort of authority, possibly cultish in origin, encouraged the inhabitants to reuse the raw

In 1961, the King of Afghanistan,

In 1961, the King of Afghanistan,

As the large dwellings at Ai-Khanoum, including those in the palace, have little in common with the traditional Greek ''

As the large dwellings at Ai-Khanoum, including those in the palace, have little in common with the traditional Greek ''

From the beginning of the excavation, the Persian and

From the beginning of the excavation, the Persian and

archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

site of a Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

city in Takhar Province

Takhar (Dari , Farsi/Pashto: ) is one of the thirty-four provinces of Afghanistan, located in the northeast of the country next to Tajikistan. It is surrounded by Badakhshan in the east, Panjshir in the south, and Baghlan and Kunduz in the w ...

, Afghanistan. The city, whose original name is unknown, was probably founded by an early ruler of the Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

and served as a military and economic centre for the rulers of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

The Bactrian Kingdom, known to historians as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom or simply Greco-Bactria, was a Hellenistic-era Greek state, and along with the Indo-Greek Kingdom, the easternmost part of the Hellenistic world in Central Asia and the Ind ...

until its destruction BC. Rediscovered in 1961, the ruins of the city were excavated by a French team of archaeologists until the outbreak of conflict in Afghanistan in the late 1970s.

The city was probably founded between 300 and 285 BC by an official acting on the orders of Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

or his son Antiochus I Soter, the first two rulers of the Seleucid dynasty

The Seleucid dynasty or the Seleucidae (from el, Σελευκίδαι, ') was a Macedonian Greek royal family, founded by Seleucus I Nicator, which ruled the Seleucid Empire centered in the Near East and regions of the Asian part of the earl ...

. It was originally thought to have been founded by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, quite possibly as Alexandria Oxiana, but this theory is now considered unlikely. There is a possibility that the site was known to the earlier Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

, who established a small fort nearby. Located at the confluence of the Amu Darya

The Amu Darya, tk, Amyderýa/ uz, Amudaryo// tg, Амударё, Amudaryo ps, , tr, Ceyhun / Amu Derya grc, Ὦξος, Ôxos (also called the Amu, Amo River and historically known by its Latin name or Greek ) is a major river in Central Asi ...

( Oxus) and Kokcha rivers, surrounded by well-irrigated farmland, Ai-Khanoum itself was divided between a lower town and a acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens, ...

. Although not situated on a major trade route

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over bodies of water. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a sing ...

, Ai-Khanoum controlled access to both mining in the Hindu Kush

The Hindu Kush is an mountain range in Central and South Asia to the west of the Himalayas. It stretches from central and western Afghanistan, Quote: "The Hindu Kush mountains run along the Afghan border with the North-West Frontier Province ...

and strategically important choke point

In military strategy, a choke point (or chokepoint) is a geographical feature on land such as a valley, defile or bridge, or maritime passage through a critical waterway such as a strait, which an armed force is forced to pass through in order ...

s. Extensive fortifications

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''face ...

, which were continuously maintained, upgraded, and rebuilt, surrounded the city.

Ai-Khanoum, which may have initially grown in population because of royal patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

and the presence of a mint

MiNT is Now TOS (MiNT) is a free software alternative operating system kernel for the Atari ST system and its successors. It is a multi-tasking alternative to TOS and MagiC. Together with the free system components fVDI device drivers, XaAE ...

in the city, lost some importance through the secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics l ...

of the Greco-Bactrians under Diodotus I ( BC). Seleucid construction programmes were halted, and the city probably became primarily military in function; it may have been a conflict zone during the invasion of Antiochus III

Antiochus III the Great (; grc-gre, Ἀντίoχoς Μέγας ; c. 2413 July 187 BC) was a Greek Hellenistic king and the 6th ruler of the Seleucid Empire, reigning from 222 to 187 BC. He ruled over the region of Syria and large parts of the r ...

( BC). Ai-Khanoum began to grow once more under Euthydemus I and his successor Demetrius I, who began to assert control over the northwest Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographical region in Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian Ocean from the Himalayas. Geopolitically, it includes the countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, In ...

. Many of the present ruins date from the time of Eucratides I, who substantially redeveloped the city and who may have renamed it Eucratideia, after himself. Soon after his death BC, the Greco-Bactrian kingdom collapsed—Ai-Khanoum was captured by Saka

The Saka ( Old Persian: ; Kharoṣṭhī: ; Ancient Egyptian: , ; , old , mod. , ), Shaka (Sanskrit ( Brāhmī): , , ; Sanskrit (Devanāgarī): , ), or Sacae (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples who histo ...

invaders and was generally abandoned, although parts of the city were sporadically occupied until the 2nd century AD. Hellenistic culture in the region would persist longer only in the Indo-Greek kingdoms.

While on a hunting trip in 1961, the King of Afghanistan, Mohammed Zahir Shah

Mohammed Zahir Shah (Pashto/Dari: , 15 October 1914 – 23 July 2007) was the last king of Afghanistan, reigning from 8 November 1933 until he was deposed on 17 July 1973. Serving for 40 years, Zahir was the longest-serving ruler of Afghanistan ...

, rediscovered the city. An archaeological delegation, led by Paul Bernard, subsequently investigated the site. Bernard and his team unearthed the remains of a huge palace in the lower town, along with a large gymnasium, a theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perfor ...

capable of holding 6,000 spectators, an arsenal

An arsenal is a place where arms and ammunition are made, maintained and repaired, stored, or issued, in any combination, whether privately or publicly owned. Arsenal and armoury (British English) or armory (American English) are mostl ...

, and two sanctuaries. Several inscriptions were found, along with coins

A coin is a small, flat (usually depending on the country or value), round piece of metal or plastic used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order t ...

, artefacts, and ceramics

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcelain ...

. The onset of the Soviet-Afghan War in the late 1970s halted scholarly progress, and during the following conflicts in Afghanistan, the site was extensively looted.

History

Ancient

The precise date of Ai-Khanoum's founding is unknown. The northernmost outpost of theIndus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley Civilisation (IVC), also known as the Indus Civilisation was a Bronze Age civilisation in the northwestern regions of South Asia, lasting from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE, and in its mature form 2600 BCE to 1900& ...

had been established at Shortugai, around north of Ai-Khanoum, during the late third millennium BC. Shortugai, which existed for several centuries, traded with its southern neighbours and constructed the first irrigation systems in the area. A thousand years later, the area fell under the control of the Persian Achaemenids

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest emp ...

, who established a satrapy (administrative province) centred on Bactra (present-day Balkh

), named for its green-tiled ''Gonbad'' ( prs, گُنبَد, dome), in July 2001

, pushpin_map=Afghanistan#Bactria#West Asia

, pushpin_relief=yes

, pushpin_label_position=bottom

, pushpin_mapsize=300

, pushpin_map_caption=Location in Afghanistan ...

), and expanded eastwards by conquering the Indus Valley. To assert control over the local region, they founded a fort named Kohna Qala on a ford of the Oxus

The Amu Darya, tk, Amyderýa/ uz, Amudaryo// tg, Амударё, Amudaryo ps, , tr, Ceyhun / Amu Derya grc, Ὦξος, Ôxos (also called the Amu, Amo River and historically known by its Latin name or Greek ) is a major river in Central Asi ...

, around north of the later city. Although scholars have speculated that a small Achaemenid garrison may have been placed at the confluence, there is no consensus that a settlement was established at Ai-Khanoum prior to the arrival of the Greco-Macedonians under Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

BC.

Historians have disputed who ordered the transformation of this small settlement into the major city it became. Initially, Ai-Khanoum was identified as Alexandria Oxiana, one of the cities founded by Alexander. There are considerable difficulties with identifying these cities, as the sources disagree; and the authors may have inadvertently referred to the same Alexandria as being at two different cities. As well as Ai-Khanoum, Alexandria Oxiana has been variously interpreted as being Alexandria in Sogdiana, Alexandria near Bactra, or as Termez

Termez ( uz, Termiz/Термиз; fa, ترمذ ''Termez, Tirmiz''; ar, ترمذ ''Tirmidh''; russian: Термез; Ancient Greek: ''Tàrmita'', ''Thàrmis'', ) is the capital of Surxondaryo Region in southern Uzbekistan. Administratively, it i ...

. As there is a lack of distinct identifying features (such as artwork, sculpture, or inscriptions) associating Alexander with the city, it remains unlikely that he did more than replace an Achaemenid garrison on the site, if it existed, with a Greek one.

Based on ceramic data gathered at the site, it is likely that Ai-Khanoum was expanded in stages. The first stage would have begun under one of the first rulers of the

Based on ceramic data gathered at the site, it is likely that Ai-Khanoum was expanded in stages. The first stage would have begun under one of the first rulers of the Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

– either the empire's founder Seleucus I Nicator

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

or his son and successor Antiochus I Soter. Seleucus established a cohesive Central Asian policy, which "went beyond the limited, ad hoc military and political aims of Alexander", according to historian Frank Holt. After the Seleucid–Mauryan war, Seleucus ceded the Indus Valley

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

to Chandragupta Maurya

Chandragupta Maurya (350-295 BCE) was a ruler in Ancient India who expanded a geographically-extensive kingdom based in Magadha and founded the Maurya dynasty. He reigned from 320 BCE to 298 BCE. The Maurya kingdom expanded to become an emp ...

, in return for a pact of friendship and 500 war elephants

A war elephant was an elephant that was trained and guided by humans for combat. The war elephant's main use was to charge the enemy, break their ranks and instill terror and fear. Elephantry is a term for specific military units using elepha ...

; he thus sought the sustained economic and military development of Bactria, which was now the headquarters of the Seleucids in the East.

Antiochus, who had a personal connection to the region through his mother, Apama

Apama ( grc, Ἀπάμα, Apáma), sometimes known as Apama I or Apame I, was a Sogdian noblewoman and the wife of the first ruler of the Seleucid Empire, Seleucus I Nicator. They Susa weddings, married at Susa in 324 BC. According to Arrian, Apa ...

, the daughter of the Sogdia

Sogdia ( Sogdian: ) or Sogdiana was an ancient Iranian civilization between the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, and in present-day Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Sogdiana was also a province of the Achaemenid Emp ...

n warlord Spitamenes, continued the policies of his father. Several of Ai-Khanoum's key buildings, including the heroön (hero's shrine), the northern fortifications, and a shrine, were constructed under his reign. It is likely that a mint

MiNT is Now TOS (MiNT) is a free software alternative operating system kernel for the Atari ST system and its successors. It is a multi-tasking alternative to TOS and MagiC. Together with the free system components fVDI device drivers, XaAE ...

was opened in Ai-Khanoum in around 285 BC, both because of the metal deposits near the city and a growing Seleucid interest in eastern Bactria, which suggests that this mint spurred the growth of the city as a royal foundation. Around one-third of the bronze coins found in the city were issued in the period following Antiochus' accession in 281 BC, an indication that he continued to spend money on the city. Under his successor Antiochus II, who came to the throne in 261 BC, the mint continued to strike valuable coins, and the ramparts were bolstered with a buttress and brick linings.

The city's development was greatly slowed when Diodotus I, governor of the eastern provinces, seceded from the Seleucids and founded the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

The Bactrian Kingdom, known to historians as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom or simply Greco-Bactria, was a Hellenistic-era Greek state, and along with the Indo-Greek Kingdom, the easternmost part of the Hellenistic world in Central Asia and the Ind ...

. Although Ai-Khanoum's temple and sanctuary were reconstructed under Diodotus, possibly to enhance religious legitimacy, most Seleucid construction programmes were not continued. Bertille Lyonnet theorises that during this time Ai-Khanoum was merely "a military stronghold with administrative functions". The Seleucid

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

emperor Antiochus III

Antiochus III the Great (; grc-gre, Ἀντίoχoς Μέγας ; c. 2413 July 187 BC) was a Greek Hellenistic king and the 6th ruler of the Seleucid Empire, reigning from 222 to 187 BC. He ruled over the region of Syria and large parts of the r ...

invaded the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom in 209 BC, defeating its ruler Euthydemus I at the Battle of the Arius and unsuccessfully besieging Bactra, Euthydemus' capital. Although there is no evidence that Ai-Khanoum was itself attacked by the invaders, Antiochus may have conducted operations near the city, or even minted his currency there. He may have also brought new settlers to the region. The later conquests of Euthydemus and his successor Demetrius I were also beneficial for the city, as the population increased and many public buildings were reconstructed. The improvement in the city's fortunes can be seen through innovations in the manufacturing and sophistication of pottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and ...

—Achaemenid styles were replaced with more varied shapes, some of which were reminiscent of Megarian

Megara (; el, Μέγαρα, ) is a historic town and a municipality in West Attica, Greece. It lies in the northern section of the Isthmus of Corinth opposite the island of Salamis, which belonged to Megara in archaic times, before being taken ...

bowls.

The city's zenith came during the rule of Eucratides I in the mid-second century BC, who probably made it his capital, naming it Eucratideia. During his reign, the palace

A palace is a grand residence, especially a royal residence, or the home of a head of state or some other high-ranking dignitary, such as a bishop or archbishop. The word is derived from the Latin name palātium, for Palatine Hill in Rome which ...

and gymnasium were constructed, the main sanctuary and heroön were rebuilt, and the theatre

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The perfor ...

was certainly active. He probably sponsored Mediterranean artists to place himself on a par with other major Hellenistic kings, the status of his capital city thus being comparable to that of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

, Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

, or Pergamum

Pergamon or Pergamum ( or ; grc-gre, Πέργαμον), also referred to by its modern Greek form Pergamos (), was a rich and powerful ancient Greek city in Mysia. It is located from the modern coastline of the Aegean Sea on a promontory on th ...

. The treasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be state or royal property, church treasure or i ...

was found to house substantial quantities of the loot from his campaigns in India against the Indo-Greek

The Indo-Greek Kingdom, or Graeco-Indian Kingdom, also known historically as the Yavana Kingdom (Yavanarajya), was a Hellenistic-era Greek kingdom covering various parts of Afghanistan and the northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent ( ...

King Menander. It is likely that Ai-Khanoum was already under attack by nomadic tribes when Eucratides was assassinated in around 144 BC. This invasion was probably carried out by Saka

The Saka ( Old Persian: ; Kharoṣṭhī: ; Ancient Egyptian: , ; , old , mod. , ), Shaka (Sanskrit ( Brāhmī): , , ; Sanskrit (Devanāgarī): , ), or Sacae (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples who histo ...

tribes driven south by the Yuezhi

The Yuezhi (;) were an ancient people first described in Chinese histories as nomadic pastoralists living in an arid grassland area in the western part of the modern Chinese province of Gansu, during the 1st millennium BC. After a major defeat ...

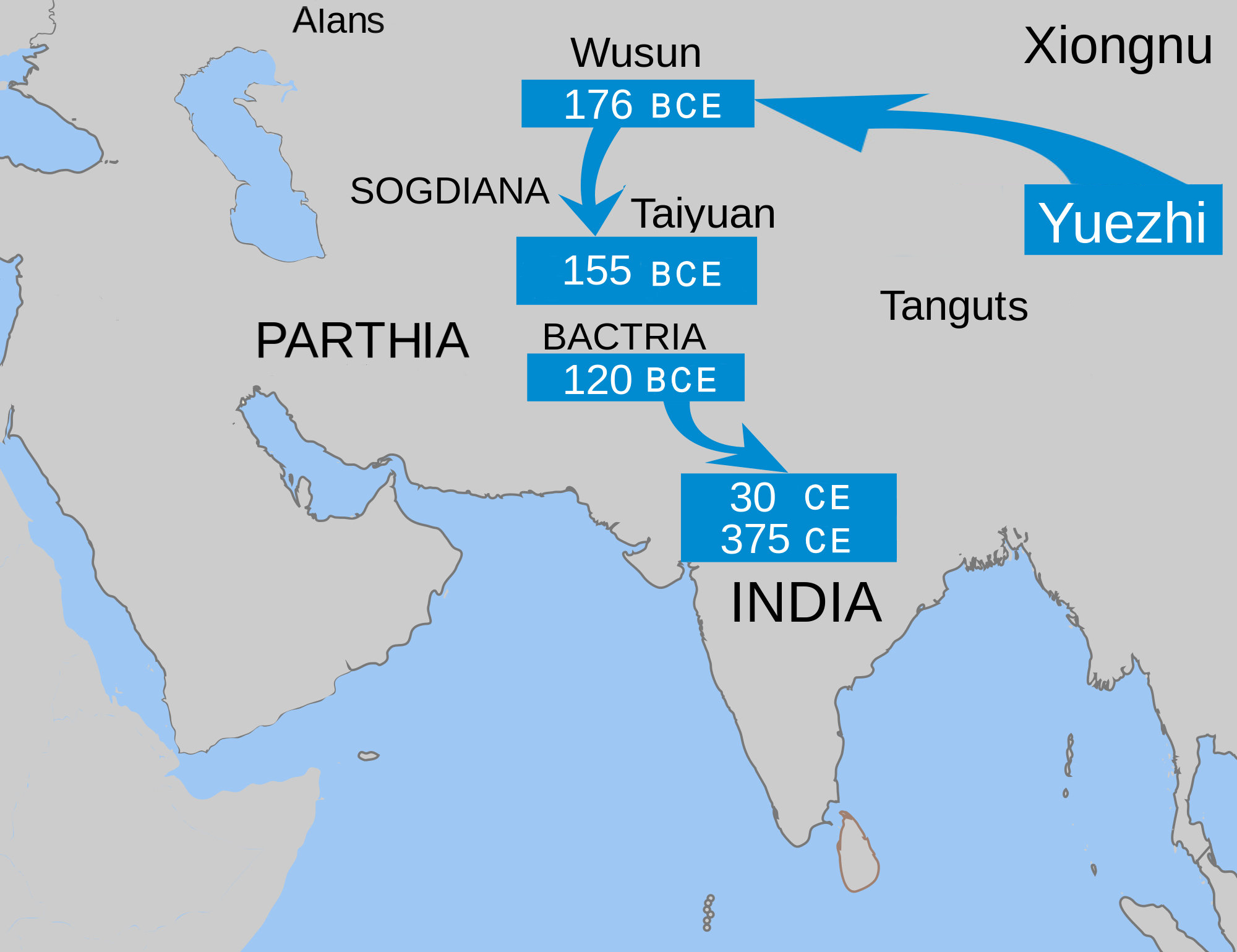

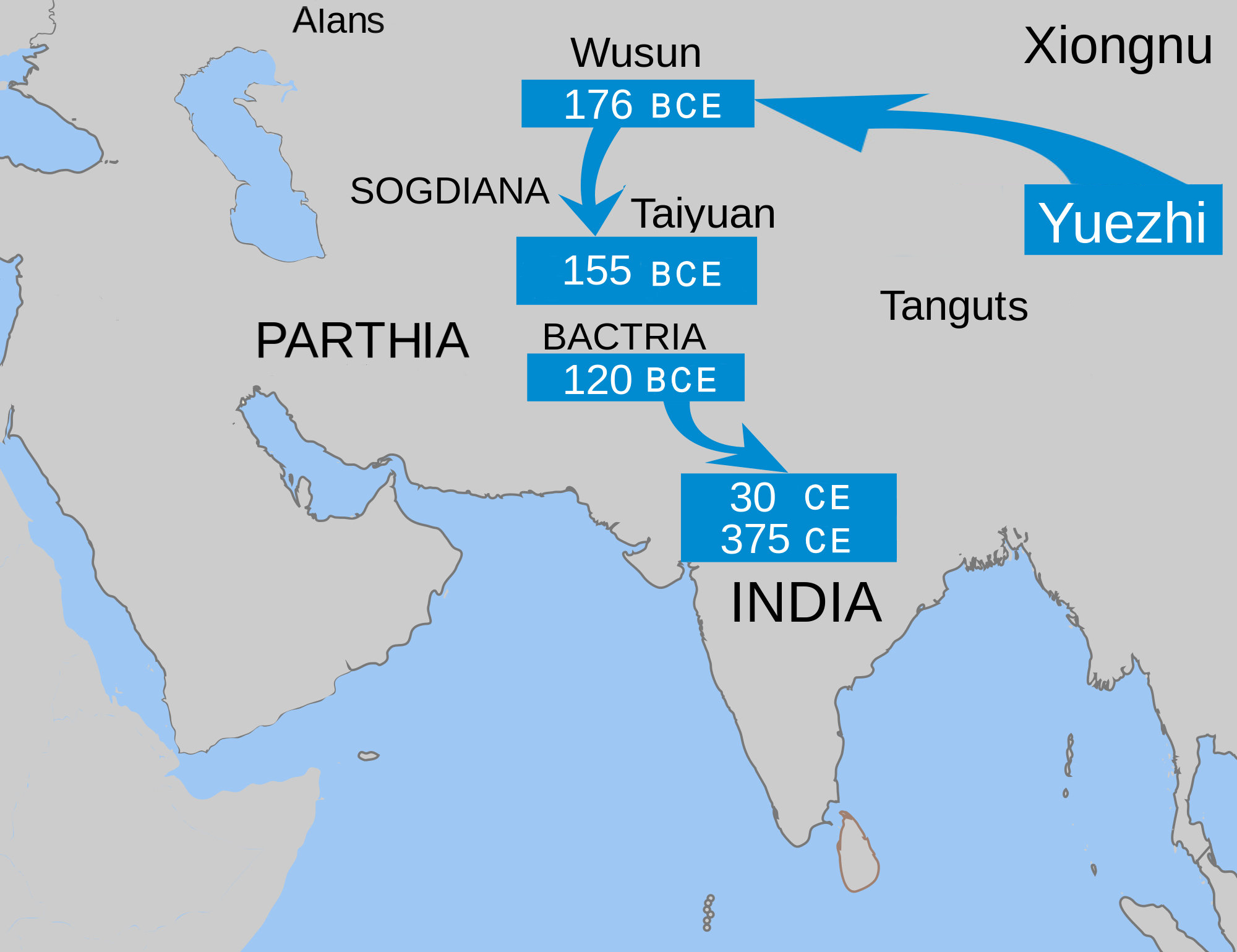

peoples, who in turn formed a second wave of invaders, in around 130 BC. The treasury complex shows signs of having been plundered in two assaults, fifteen years apart.

Although the first assault led to the end of Hellenistic rule in the city, Ai-Khanoum continued to be inhabited; it remains unknown whether this reoccupation was effected by Greco-Bactrian survivors or nomadic invaders. During this time, public buildings such as the palace and sanctuary were repurposed as residential dwellings, and the city maintained some semblance of normality: some sort of authority, possibly cultish in origin, encouraged the inhabitants to reuse the raw

Although the first assault led to the end of Hellenistic rule in the city, Ai-Khanoum continued to be inhabited; it remains unknown whether this reoccupation was effected by Greco-Bactrian survivors or nomadic invaders. During this time, public buildings such as the palace and sanctuary were repurposed as residential dwellings, and the city maintained some semblance of normality: some sort of authority, possibly cultish in origin, encouraged the inhabitants to reuse the raw building material

Building material is material used for construction. Many naturally occurring substances, such as clay, rocks, sand, wood, and even twigs and leaves, have been used to construct buildings. Apart from naturally occurring materials, many man- ...

s now freely available in the city for their own ends, whether for construction or trade. A silver ingot engraved with runic

Runes are the letters in a set of related alphabets known as runic alphabets native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were used to write various Germanic languages (with some exceptions) before they adopted the Latin alphabet, and for specialised ...

letters and buried in a treasury room provides support for the theory that the Saka occupied the city, with tombs containing typical nomadic

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the popu ...

grave goods

Grave goods, in archaeology and anthropology, are the items buried along with the body.

They are usually personal possessions, supplies to smooth the deceased's journey into the afterlife or offerings to the gods. Grave goods may be classed as a ...

also being dug into the acropolis and the gymnasium. The reoccupation of the city was soon terminated by a huge fire. It is unknown when the final occupants of Ai-Khanoum abandoned the city. The final signs of any habitation date from the 2nd century AD; by this time, more than of earth had accumulated in the palace.

Modern

In March 1838, a British soldier-explorer named John Wood was travelling in Badakshan as a representative of theEast India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Sou ...

. He was informed by his guides of the existence of an ancient city in the area, which the natives called ''Babarrah''. All his inquiries were rebuffed by the local inhabitants, and the chance of rediscovery was lost, as Wood wrote in an account:

In 1961, the King of Afghanistan,

In 1961, the King of Afghanistan, Mohammed Zahir Shah

Mohammed Zahir Shah (Pashto/Dari: , 15 October 1914 – 23 July 2007) was the last king of Afghanistan, reigning from 8 November 1933 until he was deposed on 17 July 1973. Serving for 40 years, Zahir was the longest-serving ruler of Afghanistan ...

, was on a hunting expedition when he noticed the still-visible outline of the city from a hillside. He called in the French Archaeological Delegation in Afghanistan (DAFA), who had been excavating sites in the country since 1923. The excavation was led first by Daniel Schlumberger, and then by Paul Bernard. As the city had never been resettled after its abandonment, the ruins lay close to the surface and were easy to excavate. At other sites in the region, successive generations built upon the foundations of their predecessors, leaving the Hellenistic construction layer as much as below the ground.

Nevertheless, the excavation of Ai-Khanoum proved problematic and complex. The city's immense size meant that DAFA's small team had to focus their attention on key areas, especially when the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs

The Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs () is the ministry of the Government of France that handles France's foreign relations. Since 1855, its headquarters have been located at 37 Quai d'Orsay, close to the National Assembly. The term Qu ...

decreased its funding in the mid-1970s. The inaccessibility of the city's acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens, ...

and the roughness of its terrain meant that any excavation there was much more difficult than on the lower level, leading to it being studied much less than the lower city. Despite these and other constraints, DAFA did not compromise on scientific rigour or procedure. In 1974, the remit of the mission was expanded to include paleogeographical and archaeological surveys of the surrounding areas; building upon these successful surveys, further fieldwork was also planned.

All archaeological work was stopped in 1978, when the Saur Revolution

The Saur Revolution or Sowr Revolution ( ps, د ثور انقلاب; prs, إنقلاب ثور), also known as the April Revolution or the April Coup, was staged on 27–28 April 1978 (, ) by the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) ...

sparked the Soviet-Afghan War and triggered the still-ongoing political instability in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

. During the warfare, the site was comprehensively looted, and several important artefacts were sold on the antiquities market to private collectors. The systematic looting

Looting is the act of stealing, or the taking of goods by force, typically in the midst of a military, political, or other social crisis, such as war, natural disasters (where law and civil enforcement are temporarily ineffective), or rioting. ...

of the northern part of the lower city appears to have been carried out through the digging of hundreds of holes. Although this suggests that the looters expected to find artefacts in an area DAFA had not excavated, the archaeological integrity of the site has been compromised. Although similar holes were found in the gymnasium complex, the palace complex perhaps suffered the greatest damage: the walls were used as a quarry for building materials (in some places even the deepest foundations were gutted), while the small quantities of limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms w ...

at the site, primarily found as decoration or capitals

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used fo ...

, were consumed in lime kiln

A lime kiln is a kiln used for the calcination of limestone ( calcium carbonate) to produce the form of lime called quicklime (calcium oxide). The chemical equation for this reaction is

: CaCO3 + heat → CaO + CO2

This reaction can take pla ...

s. The Northern Alliance built a gun battery atop the acropolis, further destabilizing the site.

Site

Location and layout

The city of Ai-Khanoum was founded at the southwest corner of a plain in the region ofBactria

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, sou ...

, at the confluence

In geography, a confluence (also: ''conflux'') occurs where two or more flowing bodies of water join to form a single channel. A confluence can occur in several configurations: at the point where a tributary joins a larger river (main stem); o ...

of the Oxus (modern Amu Darya) and Kokcha rivers. The plain, which covered an area of around , was triangular, being bounded by the rivers on two sides and the mountains of the eastern Hindu Kush

The Hindu Kush is an mountain range in Central and South Asia to the west of the Himalayas. It stretches from central and western Afghanistan, Quote: "The Hindu Kush mountains run along the Afghan border with the North-West Frontier Province ...

on the third. The loess

Loess (, ; from german: Löss ) is a clastic, predominantly silt-sized sediment that is formed by the accumulation of wind-blown dust. Ten percent of Earth's land area is covered by loess or similar deposits.

Loess is a periglacial or aeoli ...

soil of the plain was naturally suitable for agriculture; the proximity to the rivers allowed for the construction of irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow crops, landscape plants, and lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,000 years and has been devel ...

canals; and the nearby highlands provided herders with large areas of summer pasturage. The area was also rich in minerals: mines on the upper Kokcha in Badakshan were the only sources of lapis lazuli

Lapis lazuli (; ), or lapis for short, is a deep-blue metamorphic rock used as a semi-precious stone that has been prized since antiquity for its intense color.

As early as the 7th millennium BC, lapis lazuli was mined in the Sar-i Sang mine ...

in the world, as well as producing copper, iron, lead, and rubies. The city was downstream from the confluence of the Oxus and Qizilsu, a tributary whose valley provided access to the mineral-rich Western Pamirs and Chinese Turkestan, but also formed a natural corridor for any potential northern invaders. Ai-Khanoum therefore served as a strategically important bulwark, despite not controlling a major crossing of the Oxus or any other large trade route.

Reflecting the city's strategic importance, its founders built Ai-Khanoum to a high defensive standard. To the south and west lay the Kokcha and Oxus, respectively – both riverbanks were steep cliffs more than high, which presented a challenge to any amphibious assault. Meanwhile, any eastward approach was protected by a natural acropolis, around in height, which stretched about north from the Kokcha. This plateau also included a small citadel at its southeast corner – protected by the -high cliffs on two sides, and a small moat on the third; this fort served as the defensive headquarters of Ai-Khanoum.

These natural defences were reinforced by walls that completely enclosed Ai-Khanoum's city and acropolis. The northern ramparts, which were not assisted by any natural features, were built to be particularly strong: the -high and -thick walls were built out of solid mud brick

A mudbrick or mud-brick is an air-dried brick, made of a mixture of loam, mud, sand and water mixed with a binding material such as rice husks or straw. Mudbricks are known from 9000 BCE, though since 4000 BCE, bricks have also been f ...

s and protected by large towers and a steep ditch

A ditch is a small to moderate divot created to channel water. A ditch can be used for drainage, to drain water from low-lying areas, alongside roadways or fields, or to channel water from a more distant source for plant irrigation. Ditches ar ...

. The size of these ramparts allowed a few defending soldiers to nullify siege engine

A siege engine is a device that is designed to break or circumvent heavy castle doors, thick city walls and other fortifications in siege warfare. Some are immobile, constructed in place to attack enemy fortifications from a distance, while oth ...

s and engage an attacking force with minimal casualties; the large scale also reflects the low confidence of the Greek architects in the strength of mud-brick walls. The main gate of the city was set in the northern rampart, which also guarded the canal that supplied water to the city's centre.

From the main gate, a street ran southwards in a straight line along the base of the acropolis and continued through the lower city to the southern riverbank – a distance of about . Apart from the southern zone, which housed large dwellings organised in three blocks, the lower town was unplanned; this distinguishes Ai-Khanoum from other Hellenistic foundations of the Near East, such as Seleucia on the Tigris

Seleucia (; grc-gre, Σελεύκεια), also known as or , was a major Mesopotamian city of the Seleucid empire. It stood on the west bank of the Tigris River, within the present-day Baghdad Governorate in Iraq.

Name

Seleucia ( grc-gre, ...

, which tended to be built according to the Hippodamian

Hippodamus of Miletus (; Greek: Ἱππόδαμος ὁ Μιλήσιος, ''Hippodamos ho Milesios''; 498 – 408 BC) was an ancient Greek architect, urban planner, physician, mathematician, meteorologist and philosopher, who is considered to ...

grid plan

In urban planning, the grid plan, grid street plan, or gridiron plan is a type of city plan in which streets run at right angles to each other, forming a grid.

Two inherent characteristics of the grid plan, frequent intersections and orthogon ...

. It was also the subject of a major redevelopment during the early second century BC, which resulted in slight disunity of the orientations of some major buildings (the palace, for example, is at an angle to the older main street). Ai-Khanoum was built predominantly using unbaked bricks, with baked bricks and stone used much less often.

Palace complex

The palace complex was large, measuring about , and occupying around a third of the lower town. The size and intricacy of the complex, which was built on the order of Eucratides I, would have served as a demonstration of the ruler's power and wealth; Bernard commented that it "simultaneously served three functions: it was a state structure, a residence, and a treasury". A huge plaza, in area, lay to the south of the palace and may have been used formilitary parade

A military parade is a formation of soldiers whose movement is restricted by close-order manoeuvering known as drilling or marching. The military parade is now almost entirely ceremonial, though soldiers from time immemorial up until the la ...

s, drills, or simply as garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mili ...

quarters. The palace itself was accessed through a gateway known as the Main Propylaea

In ancient Greek architecture, a propylaea, propylea or propylaia (; Greek: προπύλαια) is a monumental gateway. They are seen as a partition, specifically for separating the secular and religious pieces of a city. The prototypical Gr ...

, which opened on the west side of the main street; the propylaea itself had been built by an earlier ruler and was reconstructed under Eucratides. Encompassing a wide portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cul ...

in between two adjoining porches, the roof of the structure was noted for its palmette

The palmette is a motif in decorative art which, in its most characteristic expression, resembles the fan-shaped leaves of a palm tree. It has a far-reaching history, originating in ancient Egypt with a subsequent development through the art ...

antefix

An antefix (from Latin ', to fasten before) is a vertical block which terminates and conceals the covering tiles of a tiled roof (see imbrex and tegula, monk and nun). It also serves to protect the join from the elements. In grand buildings, th ...

es. It allowed access to a curved road that ran towards the palace's courtyard

A courtyard or court is a circumscribed area, often surrounded by a building or complex, that is open to the sky.

Courtyards are common elements in both Western and Eastern building patterns and have been used by both ancient and contemporary ...

.

This rectangular courtyard, which measured and served as the main entrance to the palace, was entered from the curved road through another propylaeum. The courtyard was bordered by 118 Corinthian columns. The columns of the north, east, and west colonnades were high, while those of the south colonnade were almost tall, forming a Rhodian peristyle

In ancient Greek and Roman architecture, a peristyle (; from Greek ) is a continuous porch formed by a row of columns surrounding the perimeter of a building or a courtyard. Tetrastoön ( grc, τετράστῳον or τετράστοον, lit=f ...

. The palace was entered through a hypostyle

In architecture, a hypostyle () hall has a roof which is supported by columns.

Etymology

The term ''hypostyle'' comes from the ancient Greek ὑπόστυλος ''hypóstȳlos'' meaning "under columns" (where ὑπό ''hypó'' means below or un ...

behind the southern portico; this vestibule, similar in style to a Persian ''iwan

An iwan ( fa, ایوان , ar, إيوان , also spelled ivan) is a rectangular hall or space, usually vaulted, walled on three sides, with one end entirely open. The formal gateway to the iwan is called , a Persian term for a portal projectin ...

'', was supported by eighteen columns, ornamented slightly differently from those in the courtyard. On the southern side of the hypostyle, a door opened onto a large reception room ornamented with decorations including wooden sconces, painted protome

A protome (Greek προτομή) is a type of adornment that takes the form of the head and upper torso of either a human or an animal.

History

Protomes were often used to decorate ancient Greek architecture, sculpture, and pottery. Protomes we ...

s of lion

The lion (''Panthera leo'') is a large cat of the genus '' Panthera'' native to Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body; short, rounded head; round ears; and a hairy tuft at the end of its tail. It is sexually dimorphic; adu ...

s, and geometrical art; this room was probably enclosed, as it had no drainage system, and allowed access to the other areas of the palace through doors on every side.

The palace was divided into three zones, each serving different functions, and linked by a network of courtyards and long corridors, which were carefully placed, allowing both seclusion and easy access for royalty and highly ranked officials. South of the reception area lay a suite of rooms that would have served as the administrative quarters, consisting of a quadrangular

Quadrangle or The Quadrangle may refer to:

Architecture

*Quadrangle (architecture), a courtyard surrounded by a building or several buildings, often at a college

Various specific quadrangles, often called "the quad" or "the quadrangle":

North A ...

block of two pairs of units separated from each other by corridors meeting at right angle

In geometry and trigonometry, a right angle is an angle of exactly 90 degrees or radians corresponding to a quarter turn. If a ray is placed so that its endpoint is on a line and the adjacent angles are equal, then they are right angles. Th ...

s; the eastern pair were used as audience halls, while the western pair possibly functioned as chancelleries. The entrances to the chambers from the encircling corridors were offset, meaning that, in theory, two separate groups could have entered the complex, been allowed an audience, received a decision, and left, without seeing each other.

West of the administrative quarter, on the southwestern side of the palace, lay two units that were identified, by the presence of bathrooms

A bathroom or washroom is a room, typically in a home or other residential building, that contains either a bathtub or a shower (or both). The inclusion of a wash basin is common. In some parts of the world e.g. India, a toilet is typically i ...

, as residential in purpose. In layout, the structures were similar to other residences excavated in the city, with a small courtyard to the north and living quarters to the south. The larger of the units, which contained other features such as a small ''iwan'' behind the courtyard, lay to the west and was separated from its smaller neighbour by an isolating corridor. The three-room bathrooms lay to the rear of the units and were tiled with limestone slabs and pebble

A pebble is a clast of rock with a particle size of based on the Udden-Wentworth scale of sedimentology. Pebbles are generally considered larger than granules ( in diameter) and smaller than cobbles ( in diameter). A rock made predomina ...

mosaic

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly pop ...

s of palmettes and marine animals, continuing an existing tradition of Hellenistic art. Based on the more private nature of the western unit, scholars have speculated that it was intended for the sovereign's family, as contrasted with the eastern unit, which was probably intended for the monarch himself and his intimate companions. North of the residential units lay a small courtyard, which was connected to a small library

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vi ...

in the treasury.

Treasury

The treasury building, on the western side of the palace courtyard, from which it could be entered, constituted the third zone. This building was of late construction, as the treasury itself was likely previously located in buildings east of the courtyard. In its latest form, the treasury building was composed of twenty-one rooms grouped around a square courtyard of approximately on a side. The thirteen rooms on the southern, eastern, and western sides opened directly onto this courtyard, while the eight storage rooms to the north were accessed from doors on an east–west corridor. The complex housed the inventory of the palace in vases labelled in Greek, including gemstones and lapis lazuli from the Badakshan mines, ivory,olive oil

Olive oil is a liquid fat obtained from olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea''; family Oleaceae), a traditional tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin, produced by pressing whole olives and extracting the oil. It is commonly used in cooking: ...

, incense, a cash reserve, and other valuables.

Many of the vase labels, which were either written with ink or inscribed post- firing, describe monetary transactions: for example, one attests that an official named Zenon had transferred 500 drachma

The drachma ( el, δραχμή , ; pl. ''drachmae'' or ''drachmas'') was the currency used in Greece during several periods in its history:

# An ancient Greek currency unit issued by many Greek city states during a period of ten centuries, fr ...

s to two employees named Oxèboakès and Oxybazos, who were responsible for depositing the sum in the vase and sealing it. Some of the other vases indicate transportation of luxury good

In economics, a luxury good (or upmarket good) is a good for which demand increases more than what is proportional as income rises, so that expenditures on the good become a greater proportion of overall spending. Luxury goods are in contrast t ...

s, such as incense from the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, or olive oil from the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

. Because of the perishable nature of the oil inside it, one of these vases is inscribed with the regnal year of the monarch (Year 24). Combined with other inscriptions in the treasury, and the identification of the ruling monarch as Eucratides I, the date of Ai-Khanoum's fall has been dated with fair certainty to around 145 BC. Several items in the treasury are likely to have been loot brought back by Eucratides from his Indian conquests: these include Indian agate

Agate () is a common rock formation, consisting of chalcedony and quartz as its primary components, with a wide variety of colors. Agates are primarily formed within volcanic and metamorphic rocks. The ornamental use of agate was common in Anci ...

s and jewellery, offerings from Buddhist

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

stupa

A stupa ( sa, स्तूप, lit=heap, ) is a mound-like or hemispherical structure containing relics (such as ''śarīra'' – typically the remains of Buddhist monks or nuns) that is used as a place of meditation.

In Buddhism, circum ...

s, and a disc of mother-of-pearl

Nacre ( , ), also known as mother of pearl, is an organicinorganic composite material produced by some molluscs as an inner shell layer; it is also the material of which pearls are composed. It is strong, resilient, and iridescent.

Nacre is ...

plates depicting a scene from Hindu mythology

Hindu mythology is the body of myths and literature attributed to, and espoused by, the adherents of the Hindu religion, found in Hindu texts such as the Vedic literature, epics like ''Mahabharata'' and ''Ramayana'', the Puranas, and ...

. This disc, which was decorated with polychrome

Polychrome is the "practice of decorating architectural elements, sculpture, etc., in a variety of colors." The term is used to refer to certain styles of architecture, pottery or sculpture in multiple colors.

Ancient Egypt

Colossal statu ...

glass paste and gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

thread, most probably represents the meeting of Dushyanta

Dushyanta ( sa, दुष्यन्त, translit=Duṣyanta) is a king of the Chandravamsha (Lunar) dynasty featured in Hindu literature. He is the husband of Shakuntala and the father of Bharata. He appears in the Mahabharata and in Kalidas ...

and Shakuntala

Shakuntala (Sanskrit: ''Śakuntalā'') is the wife of Dushyanta and the mother of Emperor Bharata. Her story is told in the ''Adi Parva'' of the ancient Indian epic ''Mahabharata'' and dramatized by many writers, the most famous adaption bei ...

.

The library was located at the south of the treasury near the residential quarters. Its function was identified through the discovery of two literary fragments, one on papyrus and the other on parchment; the organic writing material

Writing material refers to the materials that provide the surfaces on which humans use writing instruments to inscribe writings. The same materials can also be used for symbolic or representational drawings. Building material on which writings or ...

had decomposed, but through a process similar to decalcomania

Decalcomania (from french: décalcomanie) is a decorative technique by which engravings and prints may be transferred to pottery or other materials.

A shortened version of the term is used for a mass-produced commodity art transfer or product l ...

, the letters had been engraved on fine earth formed from mudbrick decomposition. The parchment constituted an unknown theatrical work, most probably a trimetrical tragedy

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, τραγῳδία, ''tragōidia'', ''tragōidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a main character. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy ...

, possibly involving Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, myth, Dionysus (; grc, wikt:Διόνυσος, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstas ...

, a figure known for travelling to India and the East. On the other hand, the papyrus was a philosophical dialogue discussing the theory of forms

The theory of Forms or theory of Ideas is a philosophical theory, fuzzy concept, or world-view, attributed to Plato, that the physical world is not as real or true as timeless, absolute, unchangeable ideas. According to this theory, ideas in th ...

of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, which some have considered a lost work by Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

. It is also possible, conversely, that the text was written by a Greco-Bactrian philosopher in Ai-Khanoum.

Private housing

A residential zone was situated in the area south of the palatial complex. This consisted of rows of blocks of large aristocratic houses, separated by streets at right angles to the main north–south road. The DAFA archaeologists chose to excavate a house near the end of the fourth row from the palace, close to the confluence of the two rivers. This house, in area, showed evidence of three older architectural stages dating back half a century to BC; it consisted of a large courtyard to the north, and the main building to the south, separated by a large porch with two columns. The main building comprised a central reception room, encircled by a corridor which provided access to the bath complex, kitchen, and other rooms. Another house, located outside the northern rampart, was partially excavated in 1973; the archaeologists were only able to study the central part of the main building and part of the western side in detail. This extramural dwelling was much larger than the one inside the city, covering an area of . With a large courtyard to the north and buildings to the south, it had a similar layout to the urban house, although its main building was divided by an east–west corridor into two halves—the northern section formed the living quarters, with a central reception room, while the southern section included the service quarters and bath complex. Fragments of columns found at the site indicate a height of nearly . As the large dwellings at Ai-Khanoum, including those in the palace, have little in common with the traditional Greek ''

As the large dwellings at Ai-Khanoum, including those in the palace, have little in common with the traditional Greek ''oikos

The ancient Greek word ''oikos'' (ancient Greek: , plural: ; English prefix: eco- for ecology and economics) refers to three related but distinct concepts: the family, the family's property, and the house. Its meaning shifts even within texts.

The ...

'', scholars have theorised as to their origin. The prevailing hypothesis suggests an Iranian origin, similar styles being visible at Parthian Nisa and Dilberjin Tepe under the Kushan Empire

The Kushan Empire ( grc, Βασιλεία Κοσσανῶν; xbc, Κυϸανο, ; sa, कुषाण वंश; Brahmi: , '; BHS: ; xpr, 𐭊𐭅𐭔𐭍 𐭇𐭔𐭕𐭓, ; zh, 貴霜 ) was a syncretic empire, formed by the Yuezhi, ...

. Other types of housing are also present in the city, including smaller houses for people of lower status.

Religious structures

The excavators discovered threetemple

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

s at Ai-Khanoum—a large sanctuary

A sanctuary, in its original meaning, is a sacred place, such as a shrine. By the use of such places as a haven, by extension the term has come to be used for any place of safety. This secondary use can be categorized into human sanctuary, a sa ...

on the main street near the palace, a smaller temple in a similar style outside the northern wall, and an open-air podium

A podium (plural podiums or podia) is a platform used to raise something to a short distance above its surroundings. It derives from the Greek ''πόδι'' (foot). In architecture a building can rest on a large podium. Podiums can also be use ...

on the acropolis. The large sanctuary, often called the Temple with Indented Niches, was located prominently in the lower city, between the main street and the palace, and it consisted of a square edifice upon a -high podium, surrounded by an open area. It was constructed by the early Diodotids on the site of a very early Seleucid structure, which had been established shortly after the city's foundation. The eponymous indented niches were situated on the -high temple walls—one was on each side of the front entrance, while each of the other sides was sculpted with four more. The courtyard was enclosed on three sides by buildings. To the southwest, there was a wooden colonnade

In classical architecture, a colonnade is a long sequence of columns joined by their entablature, often free-standing, or part of a building. Paired or multiple pairs of columns are normally employed in a colonnade which can be straight or cur ...

with Oriental

The Orient is a term for the East in relation to Europe, traditionally comprising anything belonging to the Eastern world. It is the antonym of '' Occident'', the Western World. In English, it is largely a metonym for, and coterminous with, the ...

pedestal

A pedestal (from French ''piédestal'', Italian ''piedistallo'' 'foot of a stall') or plinth is a support at the bottom of a statue, vase, column, or certain altars. Smaller pedestals, especially if round in shape, may be called socles. In ...

s; to the southeast was a series of small rooms and porticoes adjoining a porch with columns of the distyle in antis

In classical architecture, distyle in antis denotes a temple with the side walls extending to the front of the porch and terminating with two antae, the pediment being supported by two pilasters or sometimes caryatids. This is the earliest type o ...

style, which formed the entrance from the main street; and an altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in pagan ...

was situated in the northeast wall.

From the beginning of the excavation, the Persian and

From the beginning of the excavation, the Persian and Achaemenid

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, wikt:𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎶, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an History of Iran#Classical antiquity, ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Bas ...

elements of the temple's architecture were remarked upon. The identifying "indented niches", along with the building's three-stepped platform, were common features of Mesopotamian architecture

The architecture of Mesopotamia is ancient architecture of the region of the Tigris– Euphrates river system (also known as Mesopotamia), encompassing several distinct cultures and spanning a period from the 10th millennium BC (when the first pe ...

and successor styles. Many artefacts were found at the temple, including libation

A libation is a ritual pouring of a liquid, or grains such as rice, as an offering to a deity or spirit, or in memory of the dead. It was common in many religions of antiquity and continues to be offered in cultures today.

Various substanc ...

vessels (common to both Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the fo ...

n religious practices), ivory furniture and figurine

A figurine (a diminutive form of the word ''figure'') or statuette is a small, three-dimensional sculpture that represents a human, deity or animal, or, in practice, a pair or small group of them. Figurines have been made in many media, with clay ...

s, terracottas, and a singular medallion (''pictured''). This disc, which depicts the Greek goddess Cybele

Cybele ( ; Phrygian language, Phrygian: ''Matar Kubileya/Kubeleya'' "Kubileya/Kubeleya Mother", perhaps "Mountain Mother"; Lydian language, Lydian ''Kuvava''; el, Κυβέλη ''Kybele'', ''Kybebe'', ''Kybelis'') is an Anatolian mother godde ...

accompanied by Nike in a chariot drawn by lions, was described as "remarkable" by the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

on account of its "hybrid Greek and Oriental imagery". Made of silver, the disk combines components of Greek culture, such as the chlamys

The chlamys ( Ancient Greek: χλαμύς : chlamýs, genitive: χλαμύδος : chlamydos) was a type of an ancient Greek cloak.motifs such as the fixed pose of the figures and the

The archaeologists unearthed the base of a

The archaeologists unearthed the base of a

A gymnasium was located along the western ramparts. In its final architectural phase, it covered an area of , divided between a southern courtyard and a northern complex, and was accessible from both the palace district and a street running behind the riverside fortifications. There were three doors allowing entrance from the courtyard to a corridor which encircled the main complex. This comprised long rectangular rooms surrounding a square central courtyard, entered through four exedrae, one on each side; the exedra on the northern side contained a small plinth bearing an inscribed dedication and a statue. The inscription was addressed to

A gymnasium was located along the western ramparts. In its final architectural phase, it covered an area of , divided between a southern courtyard and a northern complex, and was accessible from both the palace district and a street running behind the riverside fortifications. There were three doors allowing entrance from the courtyard to a corridor which encircled the main complex. This comprised long rectangular rooms surrounding a square central courtyard, entered through four exedrae, one on each side; the exedra on the northern side contained a small plinth bearing an inscribed dedication and a statue. The inscription was addressed to

The excavations of Ai-Khanoum yielded three

The excavations of Ai-Khanoum yielded three  ) during the coining process. At Ai-Khanoum, bricks bearing the same mark were found in the heroön, one of the oldest structures in the city. Therefore, it is considered probable that Ai-Khanoum was the site of the primary Seleucid mint during Antiochus'

) during the coining process. At Ai-Khanoum, bricks bearing the same mark were found in the heroön, one of the oldest structures in the city. Therefore, it is considered probable that Ai-Khanoum was the site of the primary Seleucid mint during Antiochus'

Some items found at Ai-Khanoum, such as Greek olive oil in the treasury or the Mediterranean plater mouldings on Greco-Bactrian artwork, would suggest the existence of large-scale trading networks, but such findings are few, while the Indian art in the treasury seems to have simply been

Some items found at Ai-Khanoum, such as Greek olive oil in the treasury or the Mediterranean plater mouldings on Greco-Bactrian artwork, would suggest the existence of large-scale trading networks, but such findings are few, while the Indian art in the treasury seems to have simply been

crescent

A crescent shape (, ) is a symbol or emblem used to represent the lunar phase in the first quarter (the "sickle moon"), or by extension a symbol representing the Moon itself.

In Hinduism, Lord Shiva is often shown wearing a crescent moon on his ...

moon.

The small fragments that remain of the cult statue

In the practice of religion, a cult image is a human-made object that is venerated or worshipped for the deity, spirit or daemon that it embodies or represents. In several traditions, including the ancient religions of Egypt, Greece and Ro ...

, which would have stood at the centre of the temple, show that it was sculpted according to the Greek tradition; a small portion of the left foot has survived and displays a thunderbolt, a common motif of Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label= genitive Boeotian Aeolic and Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label= genitive el, Δίας, ''Días'' () is the sky and thunder god in ancient Greek relig ...

. Based on the apparent dissonance between the Greek statue and the Oriental temple it was located in, scholars have posited the syncretism

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the theology and mythology of religion, thu ...

of Zeus and a Bactrian deity such as Ahura Mazda

Ahura Mazda (; ae, , translit=Ahura Mazdā; ), also known as Oromasdes, Ohrmazd, Ahuramazda, Hoormazd, Hormazd, Hormaz and Hurmuz, is the creator deity in Zoroastrianism. He is the first and most frequently invoked spirit in the ''Yasna'' ...

, Mithra

Mithra ( ae, ''Miθra'', peo, 𐎷𐎰𐎼 ''Miça'') commonly known as Mehr, is the Iranian deity of covenant, light, oath, justice and the sun. In addition to being the divinity of contracts, Mithra is also a judicial figure, an all-seein ...

, or a deity representing the Oxus.

The DAFA archaeologists were only able to perform superficial studies of the other two religious structures. The temple outside the northern wall, which had succeeded a simpler and smaller structure on the site, somewhat resembled the grand central sanctuary in architecture with niches in the walls, but featured, instead of a cult image, three chapel

A chapel is a Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. Firstly, smaller spaces inside a church that have their own altar are often called chapels; the Lady chapel is a common type ...

s for worship. The podium on the acropolis was oriented towards the east, provoking suggestions that it was used as a sacrificial

Sacrifice is the offering of material possessions or the lives of animals or humans to a deity as an act of propitiation or worship. Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks, and possibly exis ...

platform for worship of the rising sun, as similar platforms have been found in the region. As the acropolis was primarily military, with only a few small residences, scholars have suggested that it was used as a ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished ...

quarter for native Bactrian soldiers; the validity of this segregationary hypothesis continues to be debated.

Heroön of Kineas

One of the most-studied monuments in the city is a small heroön, located just north of the palace in the lower town. This shrine, which was constructed on a three-stepped platform, consisted of a distyle in antispronaos

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cult ...

, and a narrow cella

A cella (from Latin for small chamber) or naos (from the Greek ναός, "temple") is the inner chamber of an ancient Greek or Roman temple in classical antiquity. Its enclosure within walls has given rise to extended meanings, of a hermit's or ...

. Four coffins—two wooden and two stone—were found underneath the platform. Burials were generally not allowed within the walls of Greek cities—hence Ai-Khanoum's necropolis being located outside the northern ramparts—but special exemptions were made for prominent citizens, especially city founders. Since the shrine predated every other structure in the lower city, it reasonably may be supposed that the person the heroön was built to honour was either the city's founder or an extremely notable early citizen. The most prominent of the coffins, which was also the earliest, was linked to the upper temple by an opening and conduit down which offerings could be poured. As the builders had not endowed any of the other sarcophagi

A sarcophagus (plural sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Greek ...

with such a feature, this coffin would likely have housed the remains of that eminent citizen, while the others were reserved for family members. The general scholarly consensus is thus that this man, known from an inscription to have been named Kineas, was the Seleucid ''epistates An ( gr, ἐπιστάτης, plural ἐπιστάται, ) in ancient Greece was any sort of superintendent or overseer. In the Hellenistic kingdoms generally, an is always connected with a subject district (a regional assembly), where the , as ...

'' or ''oikistes

The ''oikistes'' ( gr, οἰκιστής), often anglicized

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something ...

'' who governed the first settlers of Ai-Khanoum.

The archaeologists unearthed the base of a

The archaeologists unearthed the base of a stele

A stele ( ),Anglicized plural steles ( ); Greek plural stelai ( ), from Greek language, Greek , ''stēlē''. The Greek plural is written , ''stēlai'', but this is only rarely encountered in English. or occasionally stela (plural ''stelas'' or ...

placed in a prominent position in the pronaos. Engraved upon it were the last five lines of a series of maxims, originally displayed at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), in ancient times was a sacred precinct that served as the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The orac ...

—only small and barely legible fragments of the upright portion of the stele, which would have been inscribed with the first 145 maxims, survive. An epigram

An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, and sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word is derived from the Greek "inscription" from "to write on, to inscribe", and the literary device has been employed for over two mill ...

was inscribed adjacent to the maxims, commemorating a man named Klearchos, who had copied the maxims from the Delphic sanctuary:

In 1968, Louis Robert, a French historian, proposed that the Klearchos named in the inscription was the philosopher Clearchus of Soli Clearchus of Soli ( el, Kλέαρχoς ὁ Σολεύς, ''Klearkhos ho Soleus'') was a Greek philosopher of the 4th–3rd century BCE, belonging to Aristotle's Peripatetic school. He was born in Soli in Cyprus.

He wrote extensively on eastern cul ...

. This identification was founded on the fact that the philosopher Clearchus had written extensively on the morals and cultures of barbarian and Oriental cultures. Robert proposed that on a journey to research his literary subjects in more detail, Clearchus had stopped at Ai-Khanoum and set up his stele there. This theory was accepted as fact, and was often cited as an example of the purely Greek nature of Ai-Khanoum, and of the interconnected nature of the Hellenistic world. Later historians have dismissed Robert's hypothesis: Jeffrey Lerner noted that there is no evidence to support the assumption that Clearchus travelled to the eastern regions for research, as opposed to simply using a reference source; following Lerner, Rachel Mairs observed, knowing the philosopher's approximate date of death, that the placement of the stele in the sanctuary would have been a generation after the presumed journey; Shane Wallace, meanwhile, has noted that Klearchus was not an uncommon name, and so Robert's identification was improbable at best. All three propose instead that this Klearchus was a resident of Ai-Khanoum.

Despite the refutation of Robert's theory, the stele still maintains its importance in modern analyses. The text of the epigram is poetic in its composition and vocabulary, echoing well-known Greek works such as Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

's ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Iliad'', ...

'', Pindar

Pindar (; grc-gre, Πίνδαρος , ; la, Pindarus; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar ...

's odes, and possibly even Apollonius' ''Argonautica

The ''Argonautica'' ( el, Ἀργοναυτικά , translit=Argonautika) is a Greek epic poem written by Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. The only surviving Hellenistic epic, the ''Argonautica'' tells the myth of the voyage of Jas ...

''. Mairs and Wallace have attributed the inscription and placing of the stele to "the first Bactrian-born generation" in the middle or late second century BC; they propose that this generation sought to define themselves as part of the wider Greek world by giving Ai-Khanoum legitimacy

Legitimacy, from the Latin ''legitimare'' meaning "to make lawful", may refer to:

* Legitimacy (criminal law)

* Legitimacy (family law)

* Legitimacy (political)

See also

* Bastard (law of England and Wales)

* Illegitimacy in fiction

* Legit (d ...

in the eyes of Delphi, itself a symbol of Hellenic unity.

The poem also shares thematic elements with the Buddhist Edicts of Ashoka

The Edicts of Ashoka are a collection of more than thirty inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka, as well as boulders and cave walls, attributed to Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya Empire who reigned from 268 BCE to 232 BCE. Ashoka used the exp ...

(inscribed in 260–232 BC); and Valeri Yailenko has proposed that it may have inspired them, suggesting a contribution of Hellenistic philosophy to the development of Buddhist moral precepts.

Other buildings

A gymnasium was located along the western ramparts. In its final architectural phase, it covered an area of , divided between a southern courtyard and a northern complex, and was accessible from both the palace district and a street running behind the riverside fortifications. There were three doors allowing entrance from the courtyard to a corridor which encircled the main complex. This comprised long rectangular rooms surrounding a square central courtyard, entered through four exedrae, one on each side; the exedra on the northern side contained a small plinth bearing an inscribed dedication and a statue. The inscription was addressed to

A gymnasium was located along the western ramparts. In its final architectural phase, it covered an area of , divided between a southern courtyard and a northern complex, and was accessible from both the palace district and a street running behind the riverside fortifications. There were three doors allowing entrance from the courtyard to a corridor which encircled the main complex. This comprised long rectangular rooms surrounding a square central courtyard, entered through four exedrae, one on each side; the exedra on the northern side contained a small plinth bearing an inscribed dedication and a statue. The inscription was addressed to Hermes