Adyghe verbs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In Adyghe, like all Northwest Caucasian languages, the verb is the most inflected part of speech. Verbs are typically

The verbs in simple past tense are formed by adding -aгъ /-aːʁ/. In intransitive verbs it indicates that the action took place, but with no indication as to the duration, instant nor completeness of the action. In transitive verbs it conveys more specific information with regards to completeness of the action, and therefore they indicate some certainty as to the outcome of the action.

Examples :

* кӏо /kʷʼa/ go → кӏуагъ /kʷʼaːʁ/ (s)he went

* къакӏу /qaːkʷʼ/ come → къэкӏуагъ /qakʷʼaːʁ/ (s)he came

* шхэ /ʃxa/ eat! → шхагъ /ʃxaːʁ/ (s)he ate

* ӏо /ʔʷa/ say → ыӏуагъ /jəʔʷaːʁ/ (s)he said

* еплъ /japɬ/ look at → еплъыгъ /japɬəʁ/ (s)he looked at

* шхы /ʃxə/ eat it → ышхыгъ /jəʃxəʁ/ (s)he ate it

Circassian double past and its counterparts in other West Caucasian languages

/ref> Examples : * кӏо /kʷʼa/ go → кӏогъагъ /kʷʼaʁaːʁ/ (s)he had gone * къакӏу /qaːkʷʼ/ come → къэкӏогъагъ /qakʷʼaʁaːʁ/ (s)he had come * шхэ /ʃxa/ eat! → шхэгъагъ /maʃxaʁaːʁ/ (s)he had eaten * ӏо /ʔʷa/ say → ыӏогъагъ /jəʔʷaʁaːʁ/ (s)he had said * еплъ /japɬ/ look at → еплъыгъагъ /japɬəʁaːʁ/ (s)he had looked * шхы /ʃxə/ eat it → ышхыгъагъ /jəʃxəʁaːʁ/ (s)he had eaten

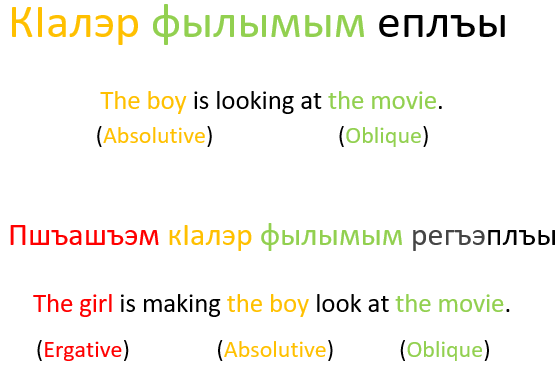

In a sentence with an intransitive bivalent verb :

* The subject is in the absolutive case.

* The indirect object is in the oblique case.

This indicates that the subject is changing by doing the verb.

Examples :

* кӏалэр егупшысэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jaɡʷəpʃəsa/ the boy is thinking of.

* кӏалэр ео /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jawa/ the boy is playing a.

* кӏалэр еджэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jad͡ʒa/ the boy is reading a.

* кӏалэр еплъы /t͡ʃʼaːɮar maːpɬa/ the boy is looking at.

* кӏалэр еупчӏы /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jawt͡ʂʼə/ the boy is asking a.

* кӏалэр елӏыкӏы /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jaɬʼət͡ʃʼə/ the boy is dying of.

* кӏалэр ебэу /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jabawə/ the boy is kissing a.

:

:

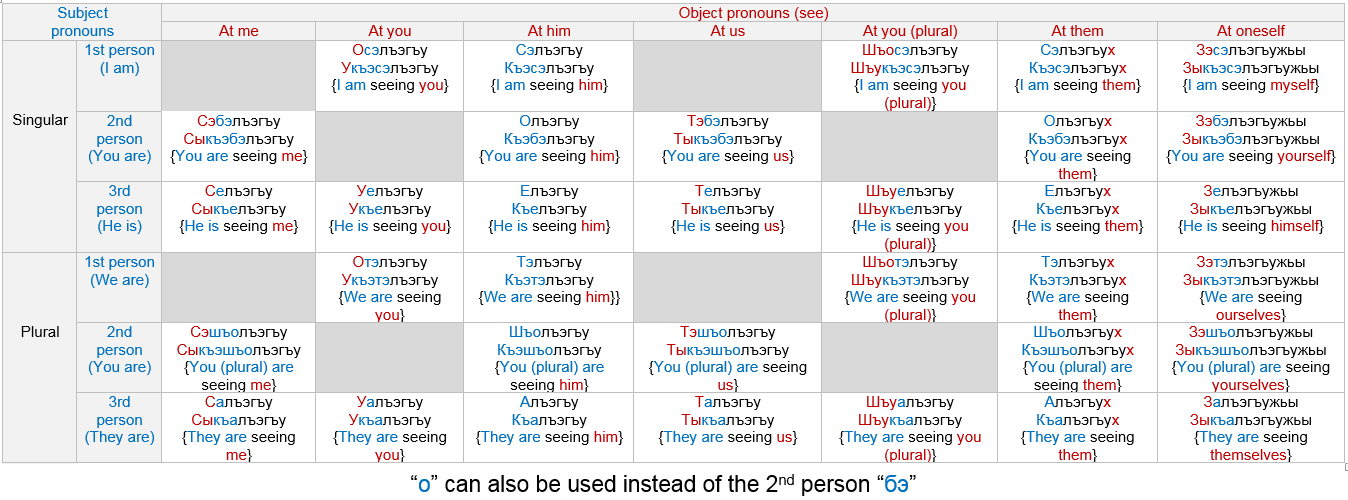

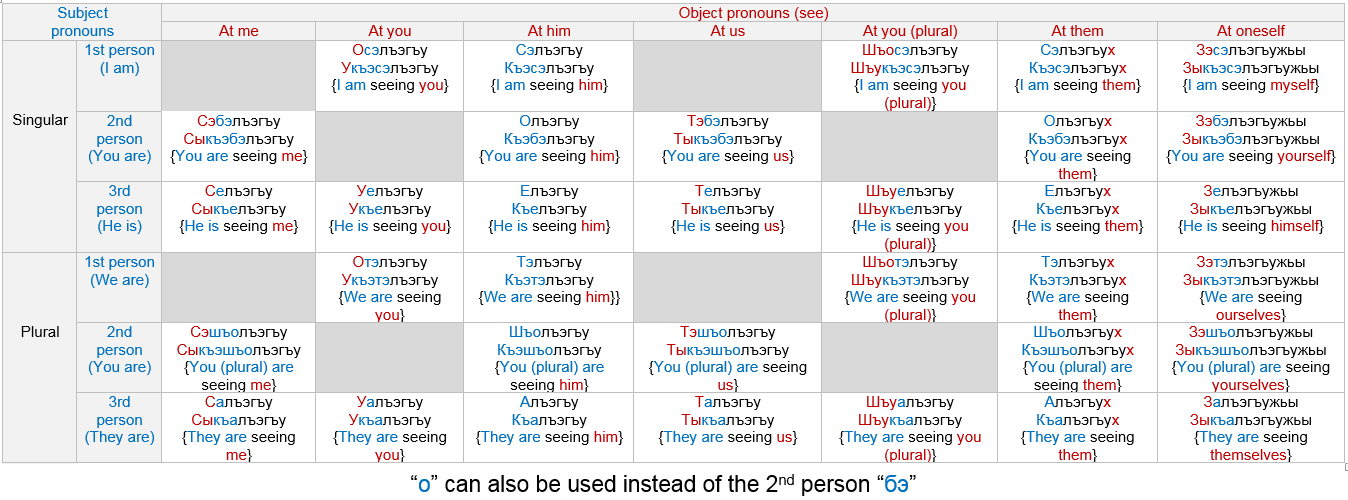

The conjugation of the intransitive bivalent verb еплъын /japɬən/ "to look at":

In a sentence with an intransitive bivalent verb :

* The subject is in the absolutive case.

* The indirect object is in the oblique case.

This indicates that the subject is changing by doing the verb.

Examples :

* кӏалэр егупшысэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jaɡʷəpʃəsa/ the boy is thinking of.

* кӏалэр ео /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jawa/ the boy is playing a.

* кӏалэр еджэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jad͡ʒa/ the boy is reading a.

* кӏалэр еплъы /t͡ʃʼaːɮar maːpɬa/ the boy is looking at.

* кӏалэр еупчӏы /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jawt͡ʂʼə/ the boy is asking a.

* кӏалэр елӏыкӏы /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jaɬʼət͡ʃʼə/ the boy is dying of.

* кӏалэр ебэу /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jabawə/ the boy is kissing a.

:

:

The conjugation of the intransitive bivalent verb еплъын /japɬən/ "to look at":

:

:

:

:

In a sentence with a transitive bivalent verbs:

*The subject is in ergative case.

*The direct object is in absolutive case.

This indicates that the subject causes change to the object.

Examples :

* кӏалэм елъэгъу /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaɬaʁʷə/ the boy is seeing a.

* кӏалэм ешхы /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaʃxə/ the boy is eating it.

* кӏалэм егъакӏо /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaʁaːkʷʼa/ the boy is making someone go.

* кӏалэм екъутэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaqʷəta/ the boy is destroying the.

* кӏалэм еукӏы /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jawt͡ʃʼə/ the boy is killing a.

* кӏалэм едзы /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jad͡zə/ the boy is throwing a.

:

:

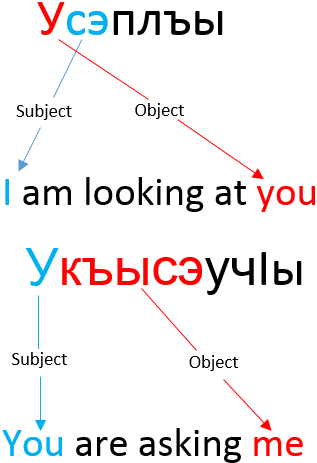

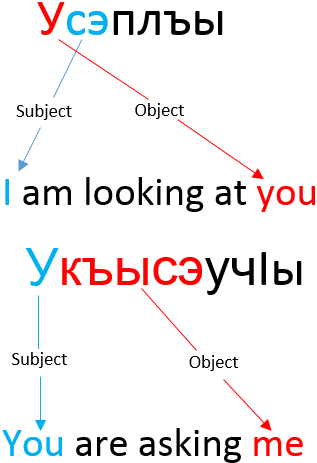

In transitive verbs the left prefix pronoun is the object while the right prefix pronoun is the subject, for example in осэгъакӏо "I am making you go", the left prefix pronoun о "you" is the object while the right prefix pronoun сэ "I" is the subject.

The conjugation of the transitive bivalent verb ылъэгъун /əɬaʁʷən/ "to see it":

In a sentence with a transitive bivalent verbs:

*The subject is in ergative case.

*The direct object is in absolutive case.

This indicates that the subject causes change to the object.

Examples :

* кӏалэм елъэгъу /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaɬaʁʷə/ the boy is seeing a.

* кӏалэм ешхы /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaʃxə/ the boy is eating it.

* кӏалэм егъакӏо /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaʁaːkʷʼa/ the boy is making someone go.

* кӏалэм екъутэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaqʷəta/ the boy is destroying the.

* кӏалэм еукӏы /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jawt͡ʃʼə/ the boy is killing a.

* кӏалэм едзы /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jad͡zə/ the boy is throwing a.

:

:

In transitive verbs the left prefix pronoun is the object while the right prefix pronoun is the subject, for example in осэгъакӏо "I am making you go", the left prefix pronoun о "you" is the object while the right prefix pronoun сэ "I" is the subject.

The conjugation of the transitive bivalent verb ылъэгъун /əɬaʁʷən/ "to see it":

:

:

:

:

Trivalent verbs require three

Trivalent verbs require three

These verbs are formed by adding the

These verbs are formed by adding the  The conjugation of the trivalent verb with an intransitive origin:

*The first prefix indicates the direct object (absolutive).

*The second prefix indicates the indirect object (oblique).

*The third prefix indicates the subject (ergative).

The conjugation of the trivalent verb with an intransitive origin:

*The first prefix indicates the direct object (absolutive).

*The second prefix indicates the indirect object (oblique).

*The third prefix indicates the subject (ergative).

File:AbsolutiveDitransitiveVerbExampleSeeMe.png, indirect object (me)

File:AbsolutiveDitransitiveVerbExampleSeeYou.png, indirect object (you)

File:AbsolutiveDitransitiveVerbExampleSeeHim.png, indirect object (him)

File:AbsolutiveDitransitiveVerbExampleSeeUs.png, indirect object (us)

File:AbsolutiveDitransitiveVerbExampleSeeYouPlural.png, indirect object (you plural)

File:AbsolutiveDitransitiveVerbExampleSeeThem.png, indirect object (them)

These verbs can be formed by adding the

These verbs can be formed by adding the  The conjugation of the trivalent verb with a transitive origin:

*The first prefix indicates the indirect object (oblique).

*The second prefix indicates the direct object (absolutive).

*The third prefix indicates the subject (ergative).

The conjugation of the trivalent verb with a transitive origin:

*The first prefix indicates the indirect object (oblique).

*The second prefix indicates the direct object (absolutive).

*The third prefix indicates the subject (ergative).

File:ErgativeDitransitiveVerbExampleSeeMe.png, direct object (me)

File:ErgativeDitransitiveVerbExampleSeeYou.png, direct object (you)

File:ErgativeDitransitiveVerbExampleSeeHim.png, direct object (him)

File:ErgativeDitransitiveVerbExampleSeeUs.png, direct object (us)

File:ErgativeDitransitiveVerbExampleSeeYouPlural.png, direct object (you plural)

File:ErgativeDitransitiveVerbExampleSeeThem.png, direct object (them)

:

:

Here is the positional conjugation of some steady-state verbs, showing how the root changes the indicated position:

:

:

:

:

Here is the positional conjugation of some steady-state verbs, showing how the root changes the indicated position:

:

:

The Cislocative prefix (marked as къы~ /q~/) is a type of verbal deixis that designates orientation towards the deictic center (origo), in the simplest case towards the speaker. In Adyghe, verbs by default are andative (Indicating motion away from something) while verbs that have къы~ are venitive (Indicating motion to or toward a thing).

For example:

* макӏо /maːkʷ'a/ (s)he goes → къакӏо /qaːkʷ'a/ (s)he comes

* мачъэ /maːt͡ʂa/ (s)he runs (there) → къачъэ /qaːt͡ʂa/ (s)he runs (here)

* маплъэ /maːpɬa/ (s)he looks (there) → къаплъэ /qaːpɬa/ (s)he looks (here)

* ехьэ /jaħa/ (s)he goes in → къехьэ /qajħa/ (s)he comes in

* ехьы /jaħə/ (s)he takes to → къехьы /qajħə/ (s)he brings

* нэсы /nasən/ (s)he reaches → къэсы /qasə/ (s)he arrives

:

:

When speaking to someone, the prefix къэ~ /qa~/ can be used to indicate that the verb is directed at him, for example :

* сэкӏо /sakʷ'a/ "I go" → сыкъакӏо /səqaːkʷ'a/ "I come"

* сэчъэ /sat͡ʂa/ "I run" → сыкъачъэ /səqaːt͡ʂa/ "I run toward you"

* сэплъэ /sapɬa/ "I look" → сыкъаплъэ /səqaːpɬa/ "I look toward you"

* техьэ /tajħa/ "we enter" → тыкъехьэ /təqajħa/ "we enter" (in case the listener is inside the house)

* тынэсы /tənasən/ "we reach" → тыкъэсы /təqasə/ "we arrive"

:

:

In

Verbs by language Adyghe language

head final

In linguistics, head directionality is a proposed parameter that classifies languages according to whether they are head-initial (the head of a phrase precedes its complements) or head-final (the head follows its complements). The head is the ...

and are conjugated for tense, person, number, etc. Some of Circassian verbs can be morphologically simple, some of them consist only of one morpheme, like: кӏо "go", штэ "take". However, generally, Circassian verbs are characterized as structurally and semantically difficult entities. Morphological structure of a Circassian verb includes affixes (prefixes, suffixes) which are specific to the language. Verbs' affixes express meaning of subject, direct or indirect object, adverbial, singular or plural form, negative form, mood, direction, mutuality, compatibility and reflexivity, which, as a result, creates a complex verb, that consists of many morphemes and semantically expresses a sentence. For example: уакъыдэсэгъэгущыӏэжьы "I am forcing you to talk to them again" consists of the following morphemes: у-а-къы-дэ-сэ-гъэ-гущыӏэ-жьы, with the following meanings: "you (у) with them (а) from there (къы) together (дэ) I (сэ) am forcing (гъэ) to speak (гущыӏэн) again (жьы)".

Tense

Adyghe verbs have several forms to express different tenses, here are some of them:

Pluperfect

The pluperfect (shortening of plusquamperfect), usually called past perfect in English, is a type of verb form, generally treated as a grammatical tense in certain languages, relating to an action that occurred prior to an aforementioned time i ...

/ Discontinuous past Discontinuous past is a category of past tense of verbs argued to exist in some languages which have a meaning roughly characterizable as "past and not present" or "past with no present relevance". The phrase "discontinuous past" was first used in ...

The tense ~гъагъ /~ʁaːʁ/ can be used for both past perfect (pluperfect) and discontinuous past:

* Past perfect: It indicates that the action took place formerly at some certain time, putting emphasis only on the fact that the action took place (not the duration)

* Past perfect 2: It expresses the idea that one action occurred before another action or event in the past.

* Discontinuous past: It carries an implication that the result of the event described no longer holds. This tense expresses the following meanings: remote past, anti resultative (‘cancelled’ result), experiential and irrealis conditional./ref> Examples : * кӏо /kʷʼa/ go → кӏогъагъ /kʷʼaʁaːʁ/ (s)he had gone * къакӏу /qaːkʷʼ/ come → къэкӏогъагъ /qakʷʼaʁaːʁ/ (s)he had come * шхэ /ʃxa/ eat! → шхэгъагъ /maʃxaʁaːʁ/ (s)he had eaten * ӏо /ʔʷa/ say → ыӏогъагъ /jəʔʷaʁaːʁ/ (s)he had said * еплъ /japɬ/ look at → еплъыгъагъ /japɬəʁaːʁ/ (s)he had looked * шхы /ʃxə/ eat it → ышхыгъагъ /jəʃxəʁaːʁ/ (s)he had eaten

Present tense

The present tense in Adyghe has no additional suffixes, but in dynamic verbs, the pronoun prefix's vowels change form ы to э or е, for instance, сышхыгъ "I ate" becomes сэшхы "I eat" (сы → сэ), ылъэгъугъ "(s)he saw" becomes елъэгъу "(s)he sees" (ы → е). Examples : * кӏо /kʷʼa/ go → макӏо /makʷʼa/ (s)he goes * къакӏу /qaːkʷʼ/ come → къакӏо /qakʷʼa/ (s)he comes * шхэ /ʃxa/ eat! → машхэ /maʃxaʁ/ (s)he eats * ӏо /ʔʷa/ say → еӏо /jəʔʷa/ (s)he says * еплъ /japɬ/ look at → еплъы /japɬə/ (s)he looks at * шхы /ʃxə/ eat it → ешхы /jəʃxə/ (s)he eats itFuture tense

The future tense is normally indicated by the suffix ~(э)щт /~(a)ɕt/ (close to future simple). This tense usually expresses some certainty. Examples : * макӏо /maːkʷʼa/ (s)he is going → кӏощт /kʷʼaɕt/ (s)he will go * къакӏо /qaːkʷʼa/ (s)he is coming → къэкӏощт /qakʷʼaɕt/ (s)he will come * машхэ /maːʃxa/ (s)he is eating → шхэщт /ʃxaɕt/ (s)he will eat * еӏо /jaʔʷa/ (s)he says → ыӏощт /jəʔʷaɕt/ (s)he will say * еплъы /jajapɬə/ (s)he looks at → еплъыщт /japɬəɕt/ (s)he will look at * ешхы /jaʃxə/ (s)he eats it → ышхыщт /jəʃxəaɕt/ (s)he will eat it

Imperfect tense

The imperfect (abbreviated ) is a verb form that combines past tense (reference to a past time) and imperfective aspect (reference to a continuing or repeated event or state). It can have meanings similar to the English "was walking" or "used to w ...

The imperfect tense is formed with the additional suffix ~щтыгъ /~ɕtəʁ/ to the verb. It can have meanings similar to the English "was walking" or "used to walk".

Examples :

* кӏо /kʷʼa/ go → кӏощтыгъ /makʷʼaɕtəʁ/ (s)he was going.

* къакӏу /qaːkʷʼ/ come → къэкӏощтыгъ /qakʷʼaɕtəʁ/ (s)he was coming .

* шхэ /ʃxa/ eat! → шхэщтыгъ /maʃxaɕtəʁ/ (s)he was eating.

* ӏо /ʔʷa/ say → ыӏощтыгъ /jəʔʷaɕtəʁ/ (s)he was saying.

* еплъ /japɬ/ look at → еплъыщтыгъ /japɬəɕtəʁ/ (s)he was looking at.

* шхы /ʃxə/ eat it → ышхыщтыгъ /jəʃxəɕtəʁ/ (s)he was eating it.

This suffix can also be used to express an action that someone used to do in the past.

Conditional perfect

TheConditional perfect The conditional perfect is a grammatical construction that combines the conditional mood with perfect aspect. A typical example is the English ''would have written''.Gail Stein, ''Webster's New World Spanish Grammar Handbook'', John Wiley & Sons, 2 ...

is indicated by the suffix ~щтыгъ /ɕtəʁ/ as well.

Examples :

* кӏо /kʷʼa/ go → кӏощтыгъ /makʷʼaɕtəʁ/ (s)he would have gone.

* къакӏу /qaːkʷʼ/ come → къэкӏощтыгъ /qakʷʼaɕtəʁ/ (s)he would have come

* шхэ /ʃxa/ eat! → шхэщтыгъ /maʃxaɕtəʁ/ (s)he would have eaten.

* ӏо /ʔʷa/ say → ыӏощтыгъ /jəʔʷaɕtəʁ/ (s)he would have said.

* еплъ /japɬ/ look at → еплъыщтыгъ /japɬəɕtəʁ/ (s)he would have looked at

* шхы /ʃxə/ eat it → ышхыщтыгъ /jəʃxəɕtəʁ/ (s)he would have eaten it.

Future perfect

Thefuture perfect

The future perfect is a verb form or construction used to describe an event that is expected or planned to happen before a time of reference in the future, such as ''will have finished'' in the English sentence "I will have finished by tomorrow." ...

tense is indicated by adding the suffix ~гъэщт or ~гъагъэщт. This tense indicates action that will be finished or expected to be finished at a certain time in the future.

Examples :

* кӏо /kʷʼa/ go → кӏогъэщт /makʷʼaʁaɕt/ (s)he will have gone.

* къакӏу /qaːkʷʼ/ come → къэкӏогъэщт /qakʷʼaʁaɕt/ (s)he will have come.

* шӏы /ʃʼə/ do it → ышӏыгъагъэщт /ət͡ʃʼəʁaːʁaɕt/ (s)he will have done it.

* ӏо /ʔʷa/ say → ыӏогъэщт /jəʔʷaʁaɕt/ (s)he will have said it.

* еплъ /japɬ/ look at → еплъыгъэщт /japɬəʁaɕt/ (s)he will have looked at.

* шхы /ʃxə/ eat it → ышхыгъэщт /jəʃxəʁaɕt/ (s)he will have eaten it.

Transitivity

In Circassian the verb being transitive orintransitive

In grammar, an intransitive verb is a verb whose context does not entail a direct object. That lack of transitivity distinguishes intransitive verbs from transitive verbs, which entail one or more objects. Additionally, intransitive verbs are ...

is of major importance in accounting for the contrast between the two cases ergative and absolutive. The division into transitive and intransitive verbs is an important distinction because each group functions a bit differently in some grammatical aspects of the language. Each group for example has its own arrangement of prefixes and conjunctions. Circassian is an ergative–absolutive language, which means it is a language in which the subject of intransitive verbs, behave like the object of transitive verbs. This is unlike nominative–accusative languages, such as English and most other European languages, where the subject of an intransitive verb (e.g. "She" in the sentence "She walks.") behaves grammatically like the agent of a transitive verb (e.g. "She" in the sentence "She finds it.")

Intransitive verbs in Circassian are verbs that have a subject in the absolutive case. The common definition of an intransitive verb is a verb that does not allow an object, and we see this in Indo-European, Turkic and other languages. This is problematic in the Circassian languages, because in Circassian, there is a number of verbs with transitive semantics but morphological features and syntactic behavior according to the intransitive pattern. Thus in Circassian, intransitive verbs can either have or not have objects.

Examples of intransitive verbs that have no objects:

* кӏон "to go"

* чъэн "to run"

* шхэн "to eat"

* гущыӏн "to talk"

* тхэн "to write"

* быбын "to fly"

* чъыен "to sleep"

* лӏэн "to die"

* пкӏэн "to jump"

* хъонэн "to curse"

* хъун "to happen"

* стын "to burn up"

* сымэджэн "to get sick"

* лъэӏон "to prey; to beg"

* тхъэжьын "to be happy"

Examples of intransitive verbs that have indirect objects:

* ебэун "to kiss"

* еплъын "to look at"

* елъэӏун "to beg to"

* еджэн "to read"

* есын "to swim"

* еон "to hit"

* ешъутырын "to kick"

* еӏункӏын "to push"

* ецэкъэн "to bite"

* еупчӏын "to ask"

* ешъон "to drink"

* ежэн "to wait"

* дэгущыӏэн "to speak with"

* ехъонын "to curse someone"

Transitive verbs in Circassian are verbs that have a subject in the ergative case. Unlike intransitive verbs, transitive verbs always need to have an object. Most transitive verbs have one object, but there are some that have two objects or several.

Examples of transitive verbs with a direct object:

* укӏын "to kill"

* шхын "to eat it"

* ӏыгъэн "to hold"

* дзын "to throw"

* лъэгъун "to see"

* хьын "to carry"

* шӏэн "to know"

* шӏын "to do"

* шӏыжьын "to fix"

* гъэшхэн "to feed"

* щэн "to lead someone"

* тхьалэн "to strangle"

* гурыӏон "to understand"

* убытын "to catch; to hug"

* штэн "to lift; to take"

* екъутэн "to break"

Examples of transitive verbs with two objects:

* ӏон "to say"

* ӏотэн "to tell"

* щэн "to sell"

* етын "to give to"

* тедзэн "to throw at"

* егъэлъэгъун "to show it to"

The absolutive case

In grammar, the absolutive case (abbreviated ) is the case of nouns in ergative–absolutive languages that would generally be the subjects of intransitive verbs or the objects of transitive verbs in the translational equivalents of nominativ ...

in Adyghe serves to mark the noun that its state changes by the verb (i.e. created, altered, moved or ended), for instance, in the English sentence "The man is dying", the man's state is changing (ending) by dying, so the man will get the absolutive case mark in Adyghe.

An example with an object will be "The man is stabbing its victim", here the man's state is changing because he is moving (likely his hands) to stab, so in this case the word man will get the absolutive case mark, the verb "stab" does not indicate what happens to the victim (getting hurt; getting killed; etc.), it just expresses the attacker's movement of assault.

Another example will be "The boy said the comforting sentence to the girl", here the sentence's state is changing (created) by being uttered by the boy and coming to existence, so sentence will get the absolutive case mark, it is important to notice that the boy's state is not changing, the verb "said" does not express how the boy uttered the sentence (moving lips or tongue; shouting; etc.).

In intransitive verbs the subject gets the absolutive case indicating that the subject is changing its state.

In transitive verbs the subject gets the ergative case indicating that the subject causes change to the direct object's state which gets the absolutive case.

For example, both the intransitive verb егъуин /jaʁʷəjən/ and the transitive verb дзын /d͡zən/ mean "to throw".

* егъуин expresses the motion the thrower (subject) does to throw something, without indicating what is being thrown, so the thrower (subject) gets the absolutive case.

* дзын expresses the movement of the object that was thrown (motion in air), without indicating the target, so the thing that is being throws (object) gets the absolutive case.

:

:

Another example is еон /jawan/ "to hit" and укӏын /wət͡ʃʼən/ "to kill".

* еон describes the movement of the hitter (subject) and there is no indication of what happens to the target (object), so the subjects gets the absolutive case because it is the one that changes (by moving).

* укӏын describes a person dying (object) by getting killed and there is no indication of how the killer does it, so the object gets the absolutive case because it is the one that changes (by ending).

:

:

Stative and dynamic verbs

Dynamic verbs express (process of) actions that are taking place while steady-state verbs express the condition and the state of the subject. For example, in Adyghe, there are two verbs for "standing", one is a dynamic verb and the other is a steady-state verb: *steady-state: The verb щыт /ɕət/ expresses someone in a standing state. *dynamic: The verb къэтэджын /qatad͡ʒən/ expresses the process of someone moving its body to stand up from a sitting state or a lying state. Examples of dynamic verbs: * ар макӏо - "(s)he is going". * ар мэчъые - "(s)he is sleeping". * ар еджэ - "(s)he is reading it". * ащ еукӏы - "(s)he is killing it". * ащ елъэгъу - "(s)he sees it". * ащ еӏо - "(s)he says it". Examples of steady state verbs: * ар щыс - "(s)he is sitting". * ар тет- "(s)he is standing on". * ар цӏыф - "(s)he is a person". * ар щыӏ - "(s)he exists". * ар илъ - "(s)he is lying inside". * ар фай - "(s)he wants". * ащ иӏ - "(s)he has". * ащ икӏас - "(s)he likes". : : :Verb valency

Verb valency

In linguistics, valency or valence is the number and type of arguments controlled by a predicate, content verbs being typical predicates. Valency is related, though not identical, to subcategorization and transitivity, which count only object ...

is the number of arguments

An argument is a statement or group of statements called premises intended to determine the degree of truth or acceptability of another statement called conclusion. Arguments can be studied from three main perspectives: the logical, the dialectic ...

controlled by a verbal predicate. Verbs in Adyghe can be monovalent (e.g. I am sitting), bivalent (e.g. I am hitting an enemy), trivalent (e.g. I am giving a book to a friend), possibly also quadrivalent (e.g. I am telling the news to someone with my friend).

For example, the verb макӏо /maːkʷʼa/ "(s)he is going" has one argument, the verb ео /jawa/ "(s)he is hitting it" has two arguments, the verb реӏо /rajʔʷa/ "(s)he is saying it to him/her" has three arguments.

Monovalent verbs

Monovalent verbs can only be intransitive having oneargument

An argument is a statement or group of statements called premises intended to determine the degree of truth or acceptability of another statement called conclusion. Arguments can be studied from three main perspectives: the logical, the dialectic ...

, an absolutive subject with no objects

Object may refer to:

General meanings

* Object (philosophy), a thing, being, or concept

** Object (abstract), an object which does not exist at any particular time or place

** Physical object, an identifiable collection of matter

* Goal, an ai ...

.

Examples :

* кӏалэр макӏо /t͡ʃʼaːɮar maːkʷʼa/ the boy is going.

* кӏалэр мачъэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮar maːt͡ʂa/ the boy is running.

* кӏалэр машхэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮar maːʃxa/ the boy is eating.

* кӏалэр маплъэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮar maːpɬa/ the boy is looking.

* кӏалэр мэгущыӏэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮar maɡʷəɕaːʔa/ the boy is speaking.

* кӏалэр малӏэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮar maːɬʼa/ the boy is dying.

:

:

:

Bivalent verbs

Bivalent verbs in Adyghe can be either intransitive or transitive.Intransitive bivalent verbs

In a sentence with an intransitive bivalent verb :

* The subject is in the absolutive case.

* The indirect object is in the oblique case.

This indicates that the subject is changing by doing the verb.

Examples :

* кӏалэр егупшысэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jaɡʷəpʃəsa/ the boy is thinking of.

* кӏалэр ео /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jawa/ the boy is playing a.

* кӏалэр еджэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jad͡ʒa/ the boy is reading a.

* кӏалэр еплъы /t͡ʃʼaːɮar maːpɬa/ the boy is looking at.

* кӏалэр еупчӏы /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jawt͡ʂʼə/ the boy is asking a.

* кӏалэр елӏыкӏы /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jaɬʼət͡ʃʼə/ the boy is dying of.

* кӏалэр ебэу /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jabawə/ the boy is kissing a.

:

:

The conjugation of the intransitive bivalent verb еплъын /japɬən/ "to look at":

In a sentence with an intransitive bivalent verb :

* The subject is in the absolutive case.

* The indirect object is in the oblique case.

This indicates that the subject is changing by doing the verb.

Examples :

* кӏалэр егупшысэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jaɡʷəpʃəsa/ the boy is thinking of.

* кӏалэр ео /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jawa/ the boy is playing a.

* кӏалэр еджэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jad͡ʒa/ the boy is reading a.

* кӏалэр еплъы /t͡ʃʼaːɮar maːpɬa/ the boy is looking at.

* кӏалэр еупчӏы /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jawt͡ʂʼə/ the boy is asking a.

* кӏалэр елӏыкӏы /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jaɬʼət͡ʃʼə/ the boy is dying of.

* кӏалэр ебэу /t͡ʃʼaːɮar jabawə/ the boy is kissing a.

:

:

The conjugation of the intransitive bivalent verb еплъын /japɬən/ "to look at":

:

:

:

:

Transitive bivalent verbs

In a sentence with a transitive bivalent verbs:

*The subject is in ergative case.

*The direct object is in absolutive case.

This indicates that the subject causes change to the object.

Examples :

* кӏалэм елъэгъу /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaɬaʁʷə/ the boy is seeing a.

* кӏалэм ешхы /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaʃxə/ the boy is eating it.

* кӏалэм егъакӏо /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaʁaːkʷʼa/ the boy is making someone go.

* кӏалэм екъутэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaqʷəta/ the boy is destroying the.

* кӏалэм еукӏы /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jawt͡ʃʼə/ the boy is killing a.

* кӏалэм едзы /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jad͡zə/ the boy is throwing a.

:

:

In transitive verbs the left prefix pronoun is the object while the right prefix pronoun is the subject, for example in осэгъакӏо "I am making you go", the left prefix pronoun о "you" is the object while the right prefix pronoun сэ "I" is the subject.

The conjugation of the transitive bivalent verb ылъэгъун /əɬaʁʷən/ "to see it":

In a sentence with a transitive bivalent verbs:

*The subject is in ergative case.

*The direct object is in absolutive case.

This indicates that the subject causes change to the object.

Examples :

* кӏалэм елъэгъу /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaɬaʁʷə/ the boy is seeing a.

* кӏалэм ешхы /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaʃxə/ the boy is eating it.

* кӏалэм егъакӏо /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaʁaːkʷʼa/ the boy is making someone go.

* кӏалэм екъутэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jaqʷəta/ the boy is destroying the.

* кӏалэм еукӏы /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jawt͡ʃʼə/ the boy is killing a.

* кӏалэм едзы /t͡ʃʼaːɮam jad͡zə/ the boy is throwing a.

:

:

In transitive verbs the left prefix pronoun is the object while the right prefix pronoun is the subject, for example in осэгъакӏо "I am making you go", the left prefix pronoun о "you" is the object while the right prefix pronoun сэ "I" is the subject.

The conjugation of the transitive bivalent verb ылъэгъун /əɬaʁʷən/ "to see it":

:

:

:

:

Trivalent verbs

Trivalent verbs require three

Trivalent verbs require three arguments

An argument is a statement or group of statements called premises intended to determine the degree of truth or acceptability of another statement called conclusion. Arguments can be studied from three main perspectives: the logical, the dialectic ...

: a subject, a direct object

Object may refer to:

General meanings

* Object (philosophy), a thing, being, or concept

** Object (abstract), an object which does not exist at any particular time or place

** Physical object, an identifiable collection of matter

* Goal, an ...

and an indirect object:

*The subject is in ergative case.

*The direct object is in absolutive case.

*The indirect object is in oblique case.

Most trivalent verbs in Adyghe are created by adding the causative

In linguistics, a causative ( abbreviated ) is a valency-increasing operationPayne, Thomas E. (1997). Describing morphosyntax: A guide for field linguists'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 173–186. that indicates that a subject either ...

prefix (гъэ~) to bivalent verbs. The causative prefix increases the valency of the verb by one and forms a transitive, thus bivalent verbs become trivalent. Intransitive bivalent verbs that become trivalent have different conjunction than transitive bivalent verbs that become trivalent, thus we end up with two types of trivalent verbs.

To form a trivalent verb one must take a bivalent verb (either intransitive or transitive), add the causative prefix -гъэ /-ʁa/ and the subject's pronoun prefix to the right.

Examples of intransitive verbs:

*ео /jawa/ "(s)he is hitting him/it" → ебэгъао /jabaʁaːwa/ "You are making him hit him/it".

*уеджэ /wajd͡ʒa/ "you are reading it" → уесэгъаджэ /wajsaʁaːd͡ʒa/ "I am making you read it".

*усэплъы /wsapɬə/ "I am looking at you" → усэзэгъэплъы /wsazaʁapɬə/ "I am making myself look at you".

*укъысэупчӏы /wqəsawt͡ʂʼə/ "you are asking me" → укъысегъэупчӏы /wqəsajʁawt͡ʂʼə/ "(s)he is making you ask me".

Examples of transitive verbs:

*едзы /jad͡zə/ "(s)he is throwing him/it" → ебэгъэдзы /jabaʁad͡zə/ "You are making him throw him/it".

*ошхы /waʃxə/ "you are eating it" → осэгъэшхы /wasaʁaʃxə/ "I am making you eat it".

*осэлъэгъу /wasaɬaʁʷə/ "I am seeing you" → осэзэгъэлъэгъу /wasazaʁaɬaʁʷə/ "I am making myself see you".

*сэбэукӏы /sabawt͡ʃʼə/ "you are killing me" → сэуегъэукӏы /sawajʁawt͡ʃʼə/ "(s)he is making you kill me".

Intransitive verbs to trivalent

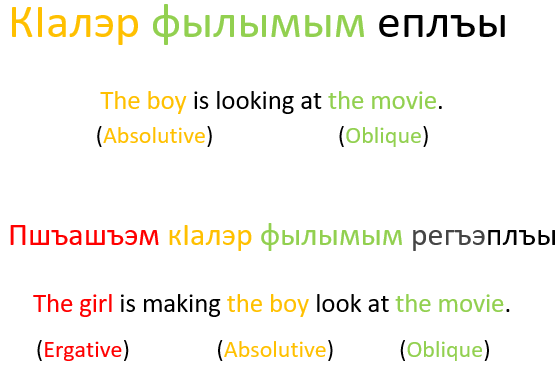

These verbs are formed by adding the

These verbs are formed by adding the causative

In linguistics, a causative ( abbreviated ) is a valency-increasing operationPayne, Thomas E. (1997). Describing morphosyntax: A guide for field linguists'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 173–186. that indicates that a subject either ...

prefix to intransitive bivalent verbs, increasing their valency and making them transitive.

Examples :

* кӏалэм регъаджэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮam rajʁaːd͡ʒa/ the boy is making him read it.

* кӏалэм регъэплъы /t͡ʃʼaːɮam rajʁapɬə/ the boy is making him watch it.

* кӏалэм регъэджыджэхы /t͡ʃʼaːɮam rajʁad͡ʒəd͡ʒaxə/ the boy is making him roll down it.

:

:

:

The conjugation of the trivalent verb with an intransitive origin:

*The first prefix indicates the direct object (absolutive).

*The second prefix indicates the indirect object (oblique).

*The third prefix indicates the subject (ergative).

The conjugation of the trivalent verb with an intransitive origin:

*The first prefix indicates the direct object (absolutive).

*The second prefix indicates the indirect object (oblique).

*The third prefix indicates the subject (ergative).

Transitive verbs to trivalent

These verbs can be formed by adding the

These verbs can be formed by adding the causative

In linguistics, a causative ( abbreviated ) is a valency-increasing operationPayne, Thomas E. (1997). Describing morphosyntax: A guide for field linguists'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 173–186. that indicates that a subject either ...

prefix to transitive bivalent verbs. There are some exceptional transitive verbs that are trivalent by default without any increasing valency prefixes such as етын "to give".

Examples :

* кӏалэм реӏо /t͡ʃʼaːɮam rajʔʷa/ the boy is saying it to him.

* кӏалэм реты /t͡ʃʼaːɮam rajʔʷa/ the boy is giving it to him.

* кӏалэм редзы /t͡ʃʼaːɮam rajd͡zə/ the boy is signing it on something.

* кӏалэм къыӏепхъуатэ /t͡ʃʼaːɮam qəʔajpχʷaːta/ the boy snatches it from him.

*уесэубытэ /wajsawbəta/ "I am holding you forcefully in it".

*уесэӏуатэ /wajsaʔʷaːta/ "I snitching you to him".

*уесэты /wajsatə/ "I am giving you to him".

*уесэгъэлъэгъу /wesaʁaɬaʁʷə/ "I am making him see you".

:

:

:

The conjugation of the trivalent verb with a transitive origin:

*The first prefix indicates the indirect object (oblique).

*The second prefix indicates the direct object (absolutive).

*The third prefix indicates the subject (ergative).

The conjugation of the trivalent verb with a transitive origin:

*The first prefix indicates the indirect object (oblique).

*The second prefix indicates the direct object (absolutive).

*The third prefix indicates the subject (ergative).

Infinitives

Adyghe infinitives are created by suffixing -н to verbs. For example: :кӏон "to go". :чъыен "to sleep". :гущыӏэн "to talk". Along with roots, verbs already inflected can be conjugated, such as with person: :ошхэ /waʃxa/ "you are eating" → ушхэн /wəʃxan/ "(for) you (to) eat" Also, due to the interchangeability of nouns and verbs, infinitives can be constructed from nouns, resulting in verbs that describe the state of being the suffixed word. :фабэ "hot" → фэбэн "to be hot". :чэщы "night" → чэщын "to be night". :дахэ "pretty" → дэхэн "to be pretty". : : :For the future tense, the suffix ~нэу is added. : :Morphology

In Circassian, morphology is the most important part of the grammar. A Circassian word, besides that it has its own lexical meaning, sometimes, by the set of morphemes it is built of and by their aggregate grammatical meanings, can reproduce a sentence. For example, a verb by its set of morphemes can express subject's and object's person, place, time, manner of action, negative, and other types of grammatical categories. Negative formPrefixes

In Adyghe, most verbal prefixes either express direction (on, under, etc.) or valency increasing (for, with, etc.).Negative form

In Circassian, negative form of a word can be expressed with two different morphemes, each being suited for different situations. Negative form can be expressed with the infix ~мы~. For example: :кӏо "go" → умыкӏу "don't go". :шхы "go" → умышх "don't eat". :шъучъый "sleep (pl.)" → шъумычъый "don't sleep (pl.)". Negative form can also be expressed with the suffix ~эп, which usually goes after the suffixes of time-tenses. For example: :кӏуагъ "(s)he went" → кӏуагъэп "(s)he didn't go". :машхэ "(s)he is eating" → машхэрэп "(s)he is not eating". :еджэщт "(s)he will read" → еджэщтэп "(s)he will not read".Causative

The suffix гъэ~ designates causation. It expresses the idea of enforcement or allowance. It can also be described as making the object do something. for example: :фабэ "hot" → егъэфабэ "(s)he heats it". :чъыӏэ "cold" → егъэучъыӏы "(s)he colds it". :макӏо "(s)he is going" → егъакӏо "(s)he is making him go; (s)he sends him". :еджэ "(s)he studies; (s)he reads" → регъаджэ "(s)he teaches; (s)he makes him read". Examples: :кӏалэм ишы тучаным егъакӏо - "the boy sends his brother to the shop". :пшъашъэм итхылъ сэ сыригъэджагъ - "the girl allowed me to read her book".Comitative

The prefix д~ designates action performed with somebody else, or stay/sojourn with somebody. :чӏэс "(s)he is sitting under" → дэчӏэс "(s)he is sitting under with him". :макӏо "(s)he is going" → дакӏо "(s)he is going with him". :еплъы "(s)he is looking at it" → деплъы "(s)he is looking at it with him". Examples: :кӏалэр пшъашъэм дэгущыӏэ - "the boy talking with the girl". :кӏэлэцӏыкӏухэр зэдэджэгух - "the kids are playing together". :сэрэ сишырэ тучанэм тызэдакӏо - "me and my brother are going to the shop together".Benefactive

The prefix ф~ designates action performed to please somebody, for somebody's sake or in somebody's interests. :чӏэс "(s)he is sitting under" → фэчӏэс "(s)he is sitting under for him". :макӏо "(s)he is going" → факӏо "(s)he is going for him". :еплъы "(s)he is looking at it" → феплъы "(s)he is looking at it for him". Examples: :кӏалэр пшъашъэм факӏо тучаным - "the boy is going to the shop for the girl". :кӏалэм псы лӏым фехьы - "the boy is bringing water to the man". :къэсфэщэф зыгорэ сешъонэу - "buy for me something to drink".Malefactive

The prefix шӏу~ designates action done against somebody's interest or will. The prefix also strongly indicates taking something away from someone by doing the action or taking a certain opportunity away from somebody else by doing the action. :ехьы "(s)he is carrying it" → шӏуехьы "(s)he is taking it away from him". :етыгъу "(s)he is stealing it" → шӏуетыгъу "(s)he is stealing it from him". :ештэ "(s)he is taking it" → шӏуештэ "(s)he is taking it away from him". :ешхы "(s)he is eating" → шӏуешхы "(s)he is consuming his food or property or resources". Examples: :сичӏыгу къэсшӏуахьыгъ - "they took my land away from me". :мощ итхьэматэ шӏосыукӏыщт - "I will take his leader's life away from him". :сянэ симашинэ къэсшӏодищыгъ - "my mother took my car out (against my interest)". :кӏалэм шӏуешхы пшъашъэм ишхын - "the boy is eating the girl's food (against her will)".Suffixes

Frequentative

The verbal suffix ~жь (~ʑ) designates recurrence/repetition of action. :ехьы "(s)he is carrying it" → ехьыжьы "(s)he is taking it again". :етыгъу "(s)he is stealing it" → етыгъужьы "(s)he is stealing it again". :ештэ "(s)he is taking it" → ештэжьы "(s)he is taking it again". :ешхы "(s)he is eating" → ешхыжьы "(s)he is eating again". Examples: :лӏым иӏофы ешӏыжьы - "the old man is doing his job again". :хым сыкӏожьынэу сыфай - "I want to return to the sea". :кӏалэр фылымым еплъыжьы - "the boy re-watches the movie". This verbal suffix can also be used to designates continuum, meaning, an action that was paused in the past and is being continued. Examples: :лӏым иӏофы ешӏыжьы - "the old man continues his work". :кӏалэр фылымым еплъыжьыгъ - "the boy finished watching the movie". :экзамыным сыфеджэжьыгъ - "I finished studying for the exam".Duration

The verbal suffix ~эу (~aw) designates action that takes place during other actions. :ехьы "(s)he is carrying it" → ехьэу "while (s)he is taking it". :етыгъу "(s)he is stealing it" → етыгъоу "while (s)he is stealing it". :ештэ "(s)he is taking it" → ештэу "while (s)he is taking it". :ешхы "(s)he is eating" → ешхэу "while (s)he is eating". Examples: :сянэ тиунэ ытхьэкӏэу унэм сыкъихьэжьыгъ - "I came home while my mother was washing the house". :сыкӏоу сылъэгъугъ кӏалэр - "while I was going, I saw the boy". :шхын щыӏэу къычӏэкӏыгъ - "it turned out that there was food".Capability

The verbal suffix ~шъу (~ʃʷə) designates the ability to perform the indicated action. :ехьы "(s)he is carrying it" → ехьышъу "(s)he is capable of carries it". :етыгъу "(s)he is stealing it" → етыгъушъу "(s)he is capable of stealing it". :ештэ "(s)he is taking it" → ештэшъу "(s)he is capable of taking it". :ешхы "(s)he is eating" → ешхышъу "(s)he is capable of eating". Examples: :лӏыжъыр мэчъэшъу - "the old man is capable of running". :экзамыным сыфеджэшъу - "I can study for the exam". :фылымым сеплъышъугъэп - "I could not watch the movie".Manner

The verbal suffix ~акӏэ (~aːt͡ʃʼa) expresses the manner in which the verb was done. It turns the verb into a noun. :ехьы "(s)he is carrying it" → ехьакӏэ "the manner in which (s)he carries it". :макӏо "(s)he is going" → кӏуакӏэ "the manner in which (s)he is going". :ештэ "(s)he is taking it" → ештакӏэ "the manner in which (s)he is talking it". :ешхы "(s)he is eating" → ешхакӏэ "the manner in which (s)he is eating". Examples: :пшъашъэм икӏуакӏэ дахэ - "the manner in which the girl goes is beautiful". :кӏалэм иеджакӏэ дэгъоп - "the manner in which the boy studies is not good". :унэм ишӏыкӏэ тэрэзыр - "the right way to build the house". A similar expression can be expressed by adding the prefix зэрэ~ /zara~/ and a noun case to the verb, but this behaves differently than the previous one. :ехьы "(s)he is carrying it" → зэрихьрэ "the way (s)he carries it". :макӏо "(s)he is going" → зэрэкӏорэ "the way (s)he is going". :ештэ "(s)he is taking it" → зэриштэрэ "the way (s)he is talking it". :ешхы "(s)he is eating" → зэришхырэ "the way(s)he is eating". Examples: :пшъашъэр зэракӏорэр дахэ - "the way the girl goes is beautiful". :кӏалэр зэреджэрэр дэгъоп - "the way the boy studies is not good". :унэр тэрэзкӏэ зэрашӏырэр - "the right way to build the house".

Imperative mood

The imperative mood is a grammatical mood that forms a command or request.

The imperative mood is used to demand or require that an action be performed. It is usually found only in the present tense, second person. To form the imperative mood, ...

The imperative mood of the second person singular has no additional affixes:

*штэ /ʃta/ "take"

*кӏо /kʷʼa/ "go"

*тхы /txə/ "write"

*шхэ /ʃxa/ "eat"

When addressing to several people, The prefix шъу- /ʃʷə-/ is added:

*шъушт /ʃʷəʃt/ "take (said to plural)"

*шъукӏу /ʃʷəkʷʼ/ "go (said to plural)"

*шъутх /ʃʷətx/ "write (said to plural)"

*шъушх /ʃʷəʃx/ "eat (said to plural)"

Positional conjugation

In Adyghe, the positional prefixes are expressing being in different positions and places and can also express the direction of the verb. Here is the positional conjugation of some dynamic verbs, showing how the prefix changes the indicated direction of the verb: :

:

Here is the positional conjugation of some steady-state verbs, showing how the root changes the indicated position:

:

:

:

:

Here is the positional conjugation of some steady-state verbs, showing how the root changes the indicated position:

:

:

Direction

In Adyghe verbs indicate the direction they are directed at. They can indicate the direction from different points of view by adding the fitting prefixes or changing the right vowels.Towards and off

In Adyghe, the positional conjugation prefixes in the transitive verbs are indicating the direction of the verb. According to the verb's vowels, it can be described if the verb is done toward the indicated direction or off it. Usually high vowels (е /aj/ or э /a/) designates that the verb is done towards the indicated direction while low vowels (ы /ə/) designates that the verb is done off the indicated direction. For example: * The word пкӏэн /pt͡ʃʼan/ "to jump" : : : * The word дзын /d͡zən/ "to throw" : : : * The word плъэн /pɬan/ "to look at" : : : * The word тӏэрэн /tʼaran/ "to drop" : : :intransitive

In grammar, an intransitive verb is a verb whose context does not entail a direct object. That lack of transitivity distinguishes intransitive verbs from transitive verbs, which entail one or more objects. Additionally, intransitive verbs are ...

verbs, it can also be used to exchange the subject and the object in a sentence, for example :

* сыфэд /səfad/ "I am like him" → къысфэд /qəsfad/ "(s)he like me"

* сыдакӏо /sədaːkʷʼa/ "I am going with him" → къыздакӏо /qəzdaːkʷʼa/ "(s)he is coming with me"

* сыфэлажьэ /sfaɮaːʑa/ "I am working for him" → къысфэлажьэ /qəsfaɮaːʑa/ "(s)he is working for me"

* удашхэ /wədaːʃxa/ "you are eating with him" → къыбдашхэ /qəbdaːʃxa/ "(s)he is eating with you"

* сыфэлажьэ /sfaɮaːʑa/ "I am working for him" → къысфэлажьэ /qəsfaɮaːʑa/ "(s)he is working for me"

* усэплъы /wsapɬə/ "I am looking at you" → укъысэплъы /wəqəsapɬə/ "you are looking at me"

* уеплъы /wajpɬə/ "you are looking at him" → къыоплъы /qəwapɬə/ "(s)he is looking at you"

:

:

:{,

, -

, кӏалэр , , пшъашъэм , , еплъа , , е , , кӏалэм , , пшъашъэр , , къеплъа?

, -

, кӏалэ-р , , пшъашъэ-м , , еплъ-а , , е , , кӏалэ-м , , пшъашъэ-р , , къ-еплъ-а?

, -

, , , , , , , , , , , , , {{IPA, qajpɬaː]

, -

, boy (abs.) , , girl (erg.) , , is (s)he looking at it? , , or , , boy (erg.) , , girl (abs.) , , is (s)he looking at it?

, -

, colspan=7, "Is the boy looking at the girl or is the girl looking at the boy?"

References

Bibliography

*Mukhadin Kumakhov & Karina Vamling, Circassian Clause StructureVerbs by language Adyghe language