Adrian Scrope on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In 1624, he married Mary Waller, sister of the poet and

In 1624, he married Mary Waller, sister of the poet and

Scrope spent little time in Scotland and played no part in the struggle for power that ended with

Scrope spent little time in Scotland and played no part in the struggle for power that ended with

Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Adrian Scrope, also spelt Scroope, 12 January 1601 to 17 October 1660, was a Parliamentarian soldier during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, then separate entities united in a pers ...

, and one of those who signed the death warrant

An execution warrant (also called death warrant or black warrant) is a writ that authorizes the execution of a condemned person. An execution warrant is not to be confused with a " license to kill", which operates like an arrest warrant bu ...

for Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742β814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226β1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

in January 1649. Despite being promised immunity after the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

in 1660, he was condemned as a regicide

Regicide is the purposeful killing of a monarch or sovereign of a polity and is often associated with the usurpation of power. A regicide can also be the person responsible for the killing. The word comes from the Latin roots of ''regis'' ...

and executed in October.

A wealthy landowner from Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (), abbreviated Bucks, is a ceremonial county in South East England that borders Greater London to the south-east, Berkshire to the south, Oxfordshire to the west, Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-ea ...

, Scrope was a relative of the Parliamentarian leader John Hampden

John Hampden (24 June 1643) was an English landowner and politician whose opposition to arbitrary taxes imposed by Charles I made him a national figure. An ally of Parliamentarian leader John Pym, and cousin to Oliver Cromwell, he was one of th ...

and fought in both the First

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

and Second English Civil War

The Second English Civil War took place between February to August 1648 in Kingdom of England, England and Wales. It forms part of the series of conflicts known collectively as the 1639-1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which include the 1641β ...

s. Appointed by Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

as head of security during the trial of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742β814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226β1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, he was present on each day and signed the death warrant. However, he largely avoided taking part in the political struggles of the Protectorate

The Protectorate, officially the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, refers to the period from 16 December 1653 to 25 May 1659 during which England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland and associated territories were joined together in the Com ...

or the Restoration of Charles II.

Initially released in June 1660 after paying a fine, he was re-arrested in August, tried for treason and found guilty, primarily due to a claim he refused to condemn the execution of Charles I, even after the Restoration. He was executed at Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Clockwise from north these are: the east side of Trafalgar Square leading to St Martin's Place and then Charing Cross Road; the Strand leading to the City; ...

, London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, on 17 October 1660.

Personal details

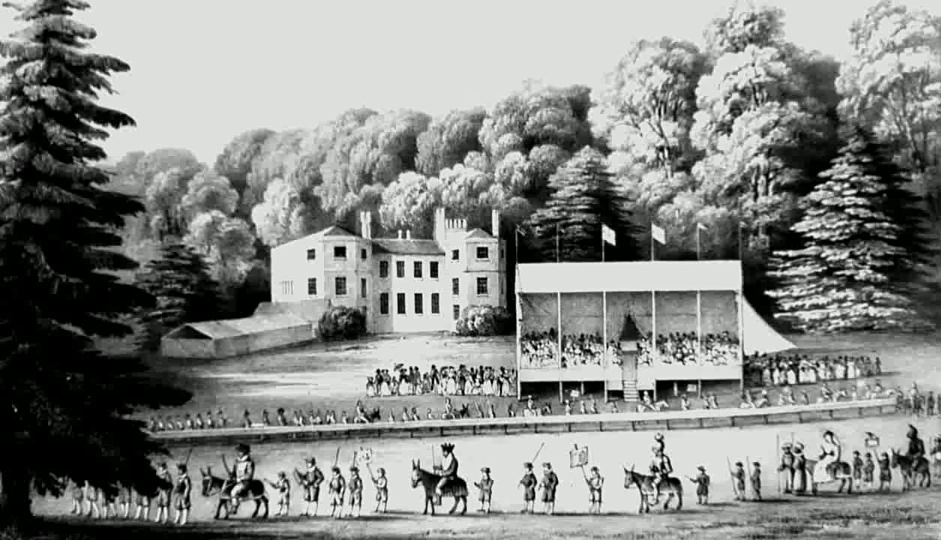

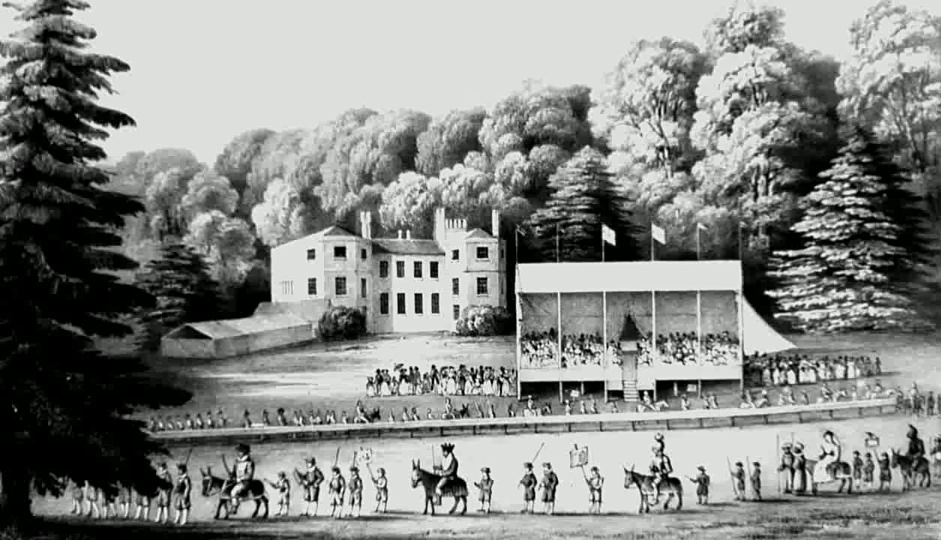

Adrian Scrope was born atWormsley Park

Wormsley is a private estate of Mark Getty and his family, set in of rolling countryside in the Chiltern Hills of Buckinghamshire (formerly Oxfordshire), England. It is also the home of Garsington Opera. Acquired by Sir Paul Getty in 1985, the e ...

, Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (), abbreviated Bucks, is a ceremonial county in South East England that borders Greater London to the south-east, Berkshire to the south, Oxfordshire to the west, Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-ea ...

and baptised on 12 January 1601, only son of Sir Robert Scrope (1569-1630) and Margaret Cornwall (1573-1633). The family were a cadet branch of the Scropes of Bolton.

In 1624, he married Mary Waller, sister of the poet and

In 1624, he married Mary Waller, sister of the poet and Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

conspirator Edmund Waller

Edmund Waller, FRS (3 March 1606 β 21 October 1687) was an English poet and politician who was Member of Parliament for various constituencies between 1624 and 1687, and one of the longest serving members of the English House of Commons.

S ...

. They had at least eight children, and probably more: Edmund (1626-1658); Robert (1628-bef. 1661); Margaret (1) (b. ca. 1630-1631; d. bef. 6 Feb 1639/40); Anne (bp. 3 June 1633); Thomas (bp. 11 Sep 1634; d. bef. Will probate 1 Aug 1704), heir of Wormsley estate; Mary (bp. 28 June 1636); Margaret (2) (bp. 6 Feb 1639/40) and Elizabeth (b. 1655; bur. 4 Aug 1738). The fact that his youngest daughter Elizabeth isn't mentioned in ''Pedigrees,'' coupled with the large gap between the births of Margaret (2) and Elizabeth, suggests that there may have been additional children.

His youngest daughter Elizabeth married Jonathan Blagrave (1652-1698), who was a Prebendary

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of the ...

of Worcester Cathedral

Worcester Cathedral is an Anglican cathedral in Worcester, in Worcestershire

Worcestershire ( , ; written abbreviation: Worcs) is a county in the West Midlands of England. The area that is now Worcestershire was absorbed into the unified ...

and related to another regicide

Regicide is the purposeful killing of a monarch or sovereign of a polity and is often associated with the usurpation of power. A regicide can also be the person responsible for the killing. The word comes from the Latin roots of ''regis'' ...

, Daniel Blagrave. On her death in 1738, she was buried in St Mary's Collegiate Church, Youghal where her memorial can still be seen. It names her father as "Colonel Adrian Scrope, of Warmesley in the County of Oxford"; as with many of those which refer to the regicides, it was deliberately defaced and broken in two at some point.

Career

Scrope graduated fromHart Hall, Oxford

Hertford College ( ), previously known as Magdalen Hall, is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. It is located on Catte Street in the centre of Oxford, directly opposite the main gate to the Bodleian Library. The colleg ...

on 7 November 1617, and as was then common studied law at the Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court exclusively entitled to call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple, Gray's Inn an ...

until 1619. There are few details of his career prior to the outbreak of the First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the Anglo ...

in August 1642; he was related to the Parliamentarian leader John Hampden

John Hampden (24 June 1643) was an English landowner and politician whose opposition to arbitrary taxes imposed by Charles I made him a national figure. An ally of Parliamentarian leader John Pym, and cousin to Oliver Cromwell, he was one of th ...

and like many of the Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (), abbreviated Bucks, is a ceremonial county in South East England that borders Greater London to the south-east, Berkshire to the south, Oxfordshire to the west, Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-ea ...

gentry joined the army of Parliament, raising a troop of horse for the Earl of Essex

Earl of Essex is a title in the Peerage of England which was first created in the 12th century by King Stephen of England. The title has been recreated eight times from its original inception, beginning with a new first Earl upon each new cre ...

and fighting at Edgehill.

In 1644, he joined Sir Robert Pye's cavalry regiment, fighting at Lostwithiel

Lostwithiel (; kw, Lostwydhyel) is a civil parish and small town in Cornwall, England, United Kingdom at the head of the estuary of the River Fowey. According to the 2001 census it had a population of 2,739, increasing to 2,899 at the 2011 c ...

and the Second Battle of Newbury

The Second Battle of Newbury was a battle of the First English Civil War fought on 27 October 1644, in Speen, adjoining Newbury in Berkshire. The battle was fought close to the site of the First Battle of Newbury, which took place in la ...

, before transferring to the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

in 1645 as a major in Colonel Richard Graves' regiment. Although the regiment was part of the force sent to relieve Taunton

Taunton () is the county town of Somerset, England, with a 2011 population of 69,570. Its thousand-year history includes a 10th-century monastic foundation, Taunton Castle, which later became a priory. The Normans built a castle owned by the ...

and missed the Battle of Naseby

The Battle of Naseby took place on 14 June 1645 during the First English Civil War, near the village of Naseby in Northamptonshire. The Parliamentarian New Model Army, commanded by Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell, destroyed the main ...

, he took part in the South-Western campaign, where it fought at Langport

Langport is a small town and civil parish in Somerset, England, west of Somerton in the South Somerset district. The parish, which covers only part of the town, has a population of 1,081. Langport is contiguous with Huish Episcopi, a separate ...

and Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

.

Just before the Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

capital of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

surrendered in June 1646, Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742β814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226β1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

escaped to join the Scottish Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, CΓΉmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from ''Covenan ...

army outside Newark

Newark most commonly refers to:

* Newark, New Jersey, city in the United States

* Newark Liberty International Airport, New Jersey; a major air hub in the New York metropolitan area

Newark may also refer to:

Places Canada

* Niagara-on-the ...

. In March 1647, the Scots handed him over to Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

in return for Β£400,000 and Graves' regiment escorted him to Holdenby House

Holdenby House is a historic country house in Northamptonshire, traditionally pronounced, and sometimes spelt, Holmby. The house is situated in the parish of Holdenby, six miles (10 km) northwest of Northampton and close to Althorp. It is a ...

in Northamptonshire

Northamptonshire (; abbreviated Northants.) is a county in the East Midlands of England. In 2015, it had a population of 723,000. The county is administered by

two unitary authorities: North Northamptonshire and West Northamptonshire. It is ...

. In the struggle for control between Parliamentary moderates and the Army Council, Graves supported Parliament; when Cornet George Joyce

Cornet George Joyce (born 1618) was a low-ranking officer in the Parliamentary New Model Army during the English Civil War.

Between 2 and 5 June 1647, while the New Model Army was assembling for rendezvous at the behest of the recently formed ...

arrived at Holmby and took charge of the king on behalf of the Council, Scrope replaced Graves as colonel.

By early 1648, Scrope was based in Blandford

Blandford Forum ( ), commonly Blandford, is a market town in Dorset, England, sited by the River Stour about northwest of Poole. It was the administrative headquarters of North Dorset District until April 2019, when this was abolished and ...

keeping order in Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset (unitary authority), Dors ...

, home base of Denzil Holles, the Army's leading Parliamentary opponent, before an alliance of English and Scots Royalists and Presbyterians led to the Second English Civil War

The Second English Civil War took place between February to August 1648 in Kingdom of England, England and Wales. It forms part of the series of conflicts known collectively as the 1639-1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which include the 1641β ...

in June. Scrope was sent to help Thomas Fairfax

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron (17 January 161212 November 1671), also known as Sir Thomas Fairfax, was an English politician, general and Parliamentary commander-in-chief during the English Civil War. An adept and talented command ...

suppress the revolt in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

and Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

, before being detached from the Siege of Colchester

The siege of Colchester occurred in the summer of 1648 when the English Civil War reignited in several areas of Britain. Colchester found itself in the thick of the unrest when a Royalist army on its way through East Anglia to raise suppo ...

to put down another rising in Cambridgeshire

Cambridgeshire (abbreviated Cambs.) is a Counties of England, county in the East of England, bordering Lincolnshire to the north, Norfolk to the north-east, Suffolk to the east, Essex and Hertfordshire to the south, and Bedfordshire and North ...

, led by Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland

Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland (baptised 15 August 1590, died 9 March 1649), was an English courtier and politician executed by Parliament after being captured fighting for the Royalists during the Second English Civil War. Younger brother of ...

. On 10 July, he took Holland prisoner at the Battle of St Neots

The Battle of St Neots on 10 July 1648 was a skirmish during the Second English Civil War at St Neots in Cambridgeshire. A Royalist force led by the Earl of Holland and Colonel John Dalbier was defeated by 100 veteran troops from the New M ...

; although Parliament voted for banishment, the Army insisted on his execution in March 1649.

Just before the Second Civil War ended, Scrope was sent to Yarmouth after reports the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers ...

was attempting to land there. Although this did not take place, it is suggested Yarmouth was the location of a meeting held around this time where Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

proposed the trial and execution of Charles I. It is not clear whether Scrope attended but shortly afterwards he became a member of the Army Council; he supported Pride's Purge

Pride's Purge is the name commonly given to an event that took place on 6 December 1648, when soldiers prevented members of Parliament considered hostile to the New Model Army from entering the House of Commons of England.

Despite defeat in the ...

in December 1648, was appointed one of the judges at trial of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742β814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226β1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

, and voted for his execution on 30 January 1649.

In April 1649, continuing unrest within the army led to a series of mutinies. Then based at Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of Wil ...

, in May Scrope's regiment was selected to take part in the reconquest of Ireland; joined by Henry Ireton

Henry Ireton ((baptised) 3 November 1611 β 26 November 1651) was an English general in the Parliamentarian army during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and the son-in-law of Oliver Cromwell. He died of disease outside Limerick in November 16 ...

's unit, they refused to go. Only eighty men remained loyal to Scrope, the rest elected new officers, fortified their positions within the town, and published a pamphlet with their demands. The units from Salisbury attempted to link up with colleagues elsewhere, posing a serious threat to the regime; Cromwell and Fairfax put down the mutiny at Burford

Burford () is a town on the River Windrush, in the Cotswolds, Cotswold hills, in the West Oxfordshire district of Oxfordshire, England. It is often referred to as the 'gateway' to the Cotswolds. Burford is located west of Oxford and southeas ...

on 17 May, three ringleaders were shot and the regiments concerned dissolved, including Scrope's.

His inability to pacify the mutineers and general unpopularity with the troops ended Scrope's active military career. In October, he was appointed governor of Bristol Castle

Bristol Castle was a Norman castle built for the defence of Bristol. Remains can be seen today in Castle Park near the Broadmead Shopping Centre, including the sally port. Built during the reign of William the Conqueror, and later owned by Rob ...

, a position he retained until June 1655 when it was demolished as part of a scheme for reducing the number of garrisons in England. In August, he was appointed to the newly formed Council of Scotland, a body established by Cromwell to administer the country following its incorporation into the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

. Edmund Ludlow

Edmund Ludlow (c. 1617β1692) was an English parliamentarian, best known for his involvement in the execution of Charles I, and for his ''Memoirs'', which were published posthumously in a rewritten form and which have become a major source f ...

, another regicide who became an opponent of Cromwell, claimed this was to offset George Monck

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle JP KG PC (6 December 1608 β 3 January 1670) was an English soldier, who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support was cruc ...

, the ambitious military commander.

Execution

Scrope spent little time in Scotland and played no part in the struggle for power that ended with

Scrope spent little time in Scotland and played no part in the struggle for power that ended with The Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

of Charles II in May 1660. He complied with the proclamation issued by Charles II on 4 June 1660, requiring the regicides to surrender within fourteen days "upon pain of being excepted from pardon". After a lengthy debate, on 9 June the Commons ruled he be discharged after paying a fine, a considerably lighter sentence than that imposed on the other prisoners.

However, on 23 July the Lords passed a motion excluding him from the Indemnity and Oblivion Act

The Indemnity and Oblivion Act 1660 was an Act of the Parliament of England (12 Cha. II c. 11), the long title of which is "An Act of Free and General Pardon, Indemnity, and Oblivion". This act was a general pardon for everyone who had committe ...

along with all the regicides; Scrope was clearly viewed with some sympathy, as on 1 August the High Sheriff of Oxfordshire

The High Sheriff of Oxfordshire, in common with other counties, was originally the King's representative on taxation upholding the law in Saxon times. The word Sheriff evolved from 'shire-reeve'.

The title of High Sheriff is therefore much olde ...

was summoned to explain why he had failed to arrest him. What sealed his fate was the allegation by Sir Richard Browne, a Parliamentarian moderate excluded in 1648 and now MP for the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

, that in a recent conversation Scrope refused to denounce the execution. As a result, on 28 August the Commons agreed to put him on trial.

At the proceedings on 12 October, Scrope claimed he acted as instructed by Parliament but admitted to an 'error of judgement'. While the presiding judge, Sir Orlando Bridgeman, agreed he was "not such a person as some of the rest", Browne's evidence meant he was condemned to death. On 17 October, he was hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under Edward III of England, King Edward III (1327β1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the rei ...

at Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Clockwise from north these are: the east side of Trafalgar Square leading to St Martin's Place and then Charing Cross Road; the Strand leading to the City; ...

, along with Thomas Scot

Thomas Scot (or Scott; died 17 October 1660) was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1645 and 1660. He was executed as one of the regicides of King Charles I.

Early life

Scot was educated at Westmi ...

, Gregory Clement

Gregory Clement (1594β1660) was an Kingdom of England, English Member of Parliament (MP) and one of the regicides of King Charles I of England, Charles I.

Biography

Clement was baptised at St Andrew's, Plymouth on 21 November 1594. His father, ...

and John Jones Maesygarnedd

John Jones Maesygarnedd (c. 1597 β 17 October 1660) was a Welsh military leader and politician, known as one of the regicides of King Charles I following the English Civil War. A brother-in-law of Oliver Cromwell, Jones was a Parliamentarian ...

; as a special favour, his body was returned to his family for burial, rather than being put on display.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Scrope, Adrian 1601 births 1660 deaths English army officers Military personnel from Buckinghamshire Alumni of Hart Hall, Oxford Executed regicides of Charles I People executed by Stuart England by hanging, drawing and quartering Executed English people People executed under the Stuarts for treason against England Parliamentarian military personnel of the English Civil War