Action Of 19 August 1916 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The action of 19 August 1916 was one of two attempts in 1916 by the German

The German force had received reassurances about Jellicoe's position, when a Zeppelin spotted the Grand Fleet heading north away from Scheer, at the time it had been avoiding the possible minefield. Zeppelin L 13 sighted the Harwich force approximately east-north-east of

The German force had received reassurances about Jellicoe's position, when a Zeppelin spotted the Grand Fleet heading north away from Scheer, at the time it had been avoiding the possible minefield. Zeppelin L 13 sighted the Harwich force approximately east-north-east of

On 13 September, a conference was held between Jellicoe and the Chief of the Admiralty War Staff, Vice-Admiral Sir

On 13 September, a conference was held between Jellicoe and the Chief of the Admiralty War Staff, Vice-Admiral Sir

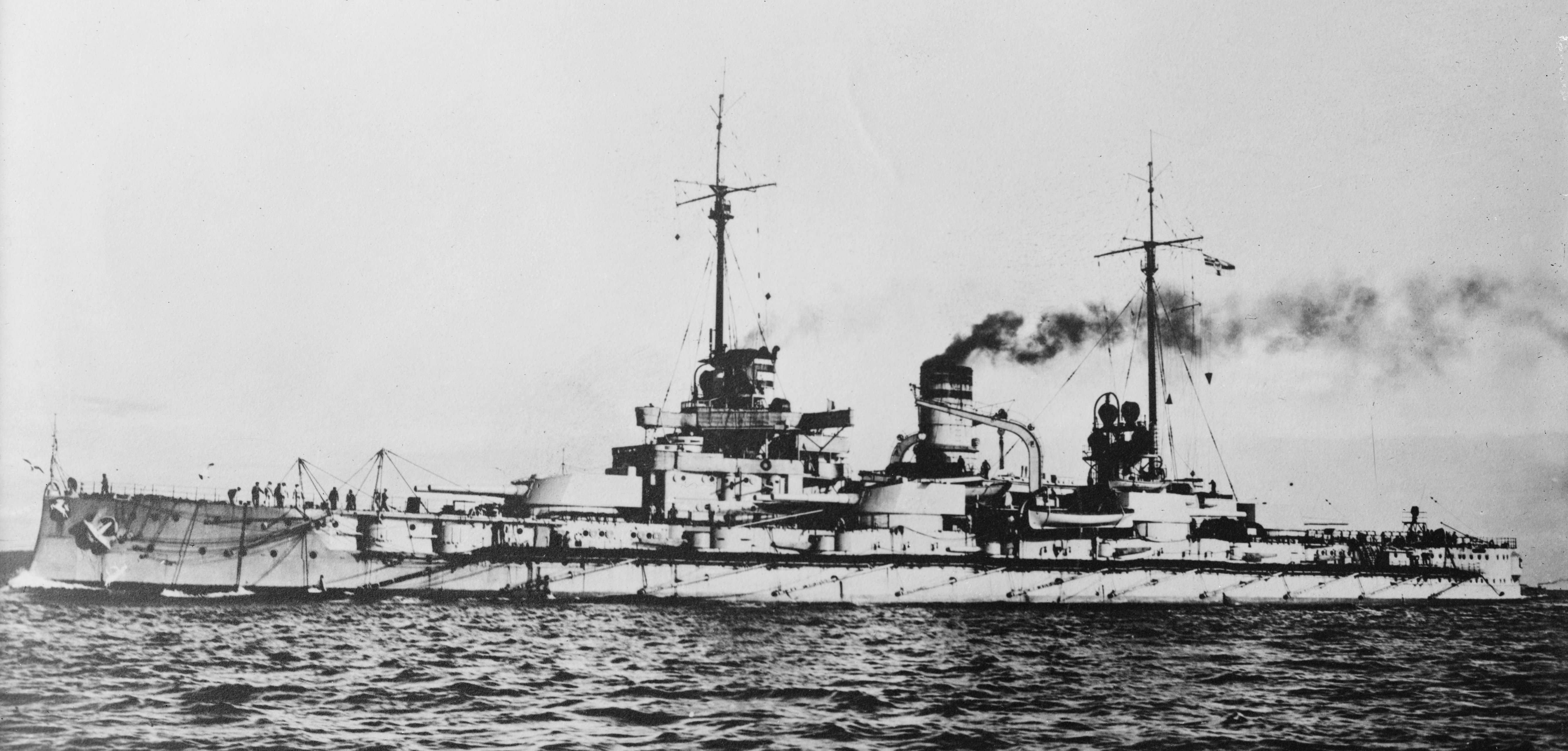

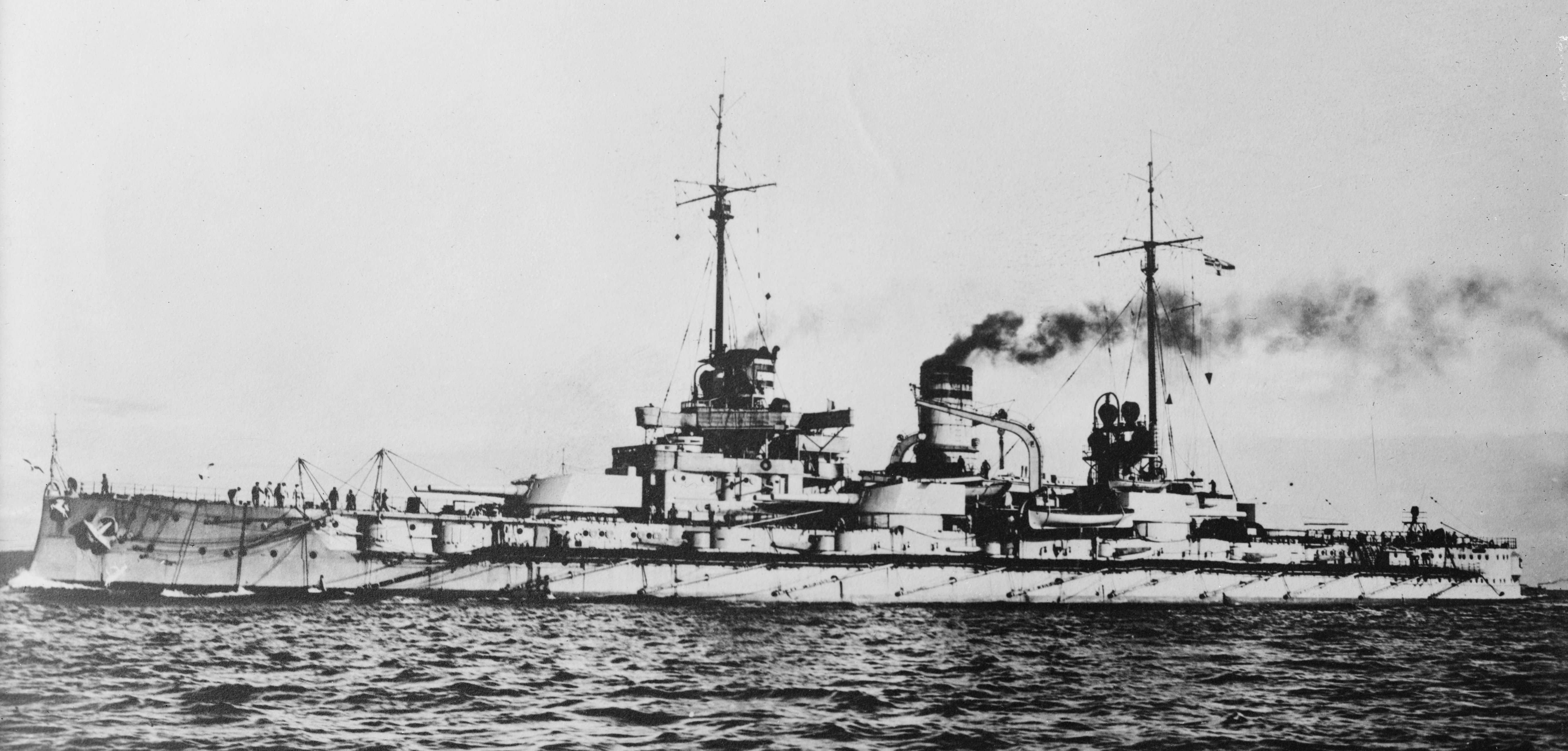

High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

to engage elements of the British Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the ...

, following the mixed results of the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland (german: Skagerrakschlacht, the Battle of the Skagerrak) was a naval battle fought between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy ...

, during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. The lesson of Jutland for Germany had been the vital need for reconnaissance, to avoid the unexpected arrival of the Grand Fleet during a raid. Four Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

s were sent to scout the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

between Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

and Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

for signs of British ships and four more scouted immediately ahead of German ships. Twenty-four German submarines kept watch off the English coast, in the southern North Sea and off the Dogger Bank

Dogger Bank (Dutch: ''Doggersbank'', German: ''Doggerbank'', Danish: ''Doggerbanke'') is a large sandbank in a shallow area of the North Sea about off the east coast of England.

During the last ice age the bank was part of a large landmass ...

.

Background

The Germans claimed victory at theBattle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland (german: Skagerrakschlacht, the Battle of the Skagerrak) was a naval battle fought between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy ...

(31 May to 1 June 1916) yet the commander of the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

, Admiral Reinhard Scheer

Carl Friedrich Heinrich Reinhard Scheer (30 September 1863 – 26 November 1928) was an Admiral in the Imperial German Navy (''Kaiserliche Marine''). Scheer joined the navy in 1879 as an officer cadet and progressed through the ranks, commandin ...

, felt it important that another raid should be mounted as quickly as possible, to maintain morale in his severely battered fleet. It was decided that the raid should follow the pattern of previous ones, with the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

s carrying out a dawn bombardment of an English town, in this case Sunderland

Sunderland () is a port city in Tyne and Wear, England. It is the City of Sunderland's administrative centre and in the Historic counties of England, historic county of County of Durham, Durham. The city is from Newcastle-upon-Tyne and is on t ...

. Only the battlecruisers and were serviceable after Jutland and the force was bolstered by the battleships , and . The remainder of the High Seas Fleet, comprising 15 dreadnought battleships, was to carry out close support behind. The fleet sailed at 9:00 p.m. on 18 August from the Jade River.

Prelude

Naval Intelligence

Information about the raid was obtained by British Naval Intelligence (Room 40

Room 40, also known as 40 O.B. (old building; officially part of NID25), was the cryptanalysis section of the British Admiralty during the First World War.

The group, which was formed in October 1914, began when Rear-Admiral Henry Oliver, the ...

) through intercepted and decoded radio messages. Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Sir John Jellicoe

Admiral of the Fleet John Rushworth Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, (5 December 1859 – 20 November 1935) was a Royal Navy officer. He fought in the Anglo-Egyptian War and the Boxer Rebellion and commanded the Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutlan ...

, commander of the Grand Fleet, was on leave so had to be recalled urgently and boarded the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

at Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

to meet his fleet in the early hours of 19 August off the River Tay

The River Tay ( gd, Tatha, ; probably from the conjectured Brythonic ''Tausa'', possibly meaning 'silent one' or 'strong one' or, simply, 'flowing') is the longest river in Scotland and the seventh-longest in Great Britain. The Tay originates ...

. In his absence, Admiral Cecil Burney

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Cecil Burney, 1st Baronet, (15 May 1858 – 5 June 1929) was a Royal Navy officer. After seeing action as a junior office in naval brigades during both the Anglo-Egyptian War and the Mahdist War, he commanded a cruiser ...

took the fleet to sea on the afternoon of 18 August. Vice-Admiral David Beatty left the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is the estuary, or firth, of several Scottish rivers including the River Forth. It meets the North Sea with Fife on the north coast and Lothian on the south.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate of ''fjord'', a Norse word meani ...

with his squadron of six battlecruisers to meet the main fleet in the Long Forties

200px, right

Long Forties is a zone of the northern North Sea that is fairly consistently deep.

Extent

Long Forties are between the northeast coasts of Scotland and the southwest coast of Norway, centred about 57°N 0°30′E; compare to th ...

.

The Harwich Force

The Harwich Force originally called Harwich Striking Force was a squadron of the Royal Navy, formed during the First World War and based in Harwich. It played a significant role in the war.

History

After the outbreak of the First World War, a p ...

of twenty destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s and five light cruisers (Commodore

Commodore may refer to:

Ranks

* Commodore (rank), a naval rank

** Commodore (Royal Navy), in the United Kingdom

** Commodore (United States)

** Commodore (Canada)

** Commodore (Finland)

** Commodore (Germany) or ''Kommodore''

* Air commodore ...

Reginald Tyrwhitt

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Reginald Yorke Tyrwhitt, 1st Baronet, (; 10 May 1870 – 30 May 1951) was a Royal Navy officer. During the First World War he served as commander of the Harwich Force. He led a supporting naval force of 31 destroyers a ...

) was ordered out, as were 25 British submarines which were stationed in likely areas to intercept German ships. The battlecruisers together with the 5th Battle Squadron of five fast battleships were stationed ahead of the main fleet to scout for the High Seas Fleet. The British moved south seeking the German fleet but suffered the loss of one of the light cruisers screening the battlecruiser group, , which was hit by three torpedoes from submarine at 6:00 a.m. and sunk.

Grand Fleet

At 6:15 a.m. Jellicoe received information from theAdmiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

that one hour earlier the enemy had been to his south east. The loss of ''Nottingham'' caused him to first head north for fear of endangering his other ships. No torpedo tracks or submarines had been seen, making it unclear whether the cause had been a submarine or a mine. He did not resume a south-easterly course until 9:00 a.m. when William Goodenough

Admiral Sir William Edmund Goodenough (2 June 1867 – 30 January 1945) was a senior Royal Navy officer of World War I. He was the son of James Graham Goodenough.

Naval career

Goodenough joined the Royal Navy in 1882. He was appointed Command ...

, commanding the light cruisers, advised that the cause had been a submarine attack. Further information from the Admiralty indicated that the battlecruisers would be within of the main German fleet by 2:00 p.m. and Jellicoe increased to maximum speed. Weather conditions were good and there was still plenty of time for a fleet engagement before dark.

High Seas Fleet

The German force had received reassurances about Jellicoe's position, when a Zeppelin spotted the Grand Fleet heading north away from Scheer, at the time it had been avoiding the possible minefield. Zeppelin L 13 sighted the Harwich force approximately east-north-east of

The German force had received reassurances about Jellicoe's position, when a Zeppelin spotted the Grand Fleet heading north away from Scheer, at the time it had been avoiding the possible minefield. Zeppelin L 13 sighted the Harwich force approximately east-north-east of Cromer

Cromer ( ) is a coastal town and civil parish on the north coast of the English county of Norfolk. It is north of Norwich, north-northeast of London and east of Sheringham on the North Sea coastline.

The local government authorities are Nor ...

, mistakenly identifying the cruisers as battleships. This was the sort of target Scheer was seeking, so he changed course at 12:15 p.m. also to the south-east and away from the approaching British fleet. No further reports were received from Zeppelins about the British fleet but it was spotted by a U-boat north of Scheer. The High Seas Fleet turned for home at 2:35 p.m. abandoning this potential target. By 4:00 p.m. Jellicoe had been advised that Scheer had abandoned the operation and so turned north himself.

Other engagements

A second cruiser attached to the battlecruiser squadron, , was hit by two torpedoes from at ''Falmouth'' managed to raise steam and made slowly forHumber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal rivers Ouse and Trent. From there to the North Sea, it forms part of the boundary between th ...

, escorted by four destroyers; in the early hours a tug arrived and took the ship in tow. Taking the shortest route to the Humber put the ship on a bearing which took it along the Flamborough Head U-boat line. At noon, the ship, now escorted by eight destroyers, was hit by two torpedoes fired by ( Otto Schultze

Otto Schultze (11 May 1884 – 22 January 1966) was a '' Generaladmiral'' with the '' Kriegsmarine'' during World War II and a recipient of the ''Pour le Mérite'' during World War I. The ''Pour le Mérite'' was the Kingdom of Prussia's highest ...

). ''Falmouth'' remained afloat for another eight hours then sank south of Flamborough Head. By the Harwich force had sighted German ships but was too far behind to attack before nightfall and abandoned the chase. The British submarine (Lieutenant-Commander R. R. Turner) managed to hit the German battleship north of Terschelling at on 19 August but the ship was able to reach port.

Aftermath

On 13 September, a conference was held between Jellicoe and the Chief of the Admiralty War Staff, Vice-Admiral Sir

On 13 September, a conference was held between Jellicoe and the Chief of the Admiralty War Staff, Vice-Admiral Sir Henry Oliver

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Henry Francis Oliver, (22 January 1865 – 15 October 1965) was a Royal Navy officer. After serving in the Second Boer War as a navigating officer in a cruiser on the Cape of Good Hope and West Coast of Africa Station ...

, on ''Iron Duke'' to discuss recent events. It was provisionally decided that it was unsafe to conduct fleet operations south of latitude 55.5° North (approximately level with Horns reef

Horns Rev is a shallow sandy reef of glacial deposits in the eastern North Sea, about off the westernmost point of Denmark, Blåvands Huk.

and where the battle of Jutland had taken place). Jellicoe took the view that a destroyer shortage precluded operations further south but that it was feasible to operate west of Longitude 4° East should there be a good opportunity of engaging the German fleet in daylight. The fleet should not sail further south than the Dogger Bank until a complete destroyer screen was available, except in exceptional circumstances, such as the chance to engage the High Seas Fleet with a tactical advantage or to intercept a German invasion fleet. On 23 September the Admiralty endorsed the conclusions of the meeting due to the effect of submarines and mines on surface ship operations. Scheer was unimpressed by the Zeppelin reconnaissance, only three had spotted anything and of their seven reports four had been wrong.

This was the last occasion on which the German fleet travelled so far west into the North Sea. On 6 October, the German government resumed attacks against merchant vessels by submarine, which meant the U-boat fleet was no longer available for combined attacks against surface vessels. From 18 to 19 October, Scheer led a brief sortie into the North Sea of which British intelligence gave advance warning; the Grand Fleet declined to prepare an ambush, staying in port with steam raised, ready to sail. The German sortie was abandoned after a few hours when was hit by a torpedo fired by (Lieutenant-Commander J. de B. Jessop) and it was feared other submarines might be in the area. Scheer suffered further difficulties when in November he sailed with ''Moltke'' and a division of dreadnoughts to rescue and , which had been stranded, on the Danish coast. British submarine (Commander Noel Laurence

Admiral Sir Noel Frank Laurence (27 December 1882 – 26 January 1970) was a notable Royal Navy submarine commander during the First World War.

Early life

Laurence was born in 1882 in Kent, the son of Frederic Laurence, . He joined the Royal Na ...

) managed to hit the battleships and . The failure of these operations reinforced the belief, created at Jutland, that the risks were too great for such tactics, because of the danger from submarines and mines.

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * *Further reading

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:19160819 Conflicts in 1916 Naval battles of World War I involving Germany Naval battles of World War I involving the United Kingdom North Sea operations of World War I August 1916 events