Abraham Lincoln's patent on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Abraham Lincoln's patent relates to an

The invention stemmed from Lincoln's experiences ferrying travelers and carrying freight on the

The invention stemmed from Lincoln's experiences ferrying travelers and carrying freight on the

Lincoln labeled his invention ''Buoying Vessels Over Shoals'' and it was used to get them over shoals. He envisioned a system of waterproof fabric bladders that could be inflated when necessary to help ease a stuck steamboat over such obstacles. When crew members knew their ship was stuck, or at risk of hitting a shallow, Lincoln's invention could be activated, which would inflate accordion-shaped air chambers along the sides of the watercraft to lift it above the water's surface, providing enough clearance to avoid a disaster. As part of the research process, Lincoln designed a scale model of a ship outfitted with the device. This model (built and assembled with the assistance of a mechanic from Springfield named Walter Davis) that was originally taken to the

Lincoln labeled his invention ''Buoying Vessels Over Shoals'' and it was used to get them over shoals. He envisioned a system of waterproof fabric bladders that could be inflated when necessary to help ease a stuck steamboat over such obstacles. When crew members knew their ship was stuck, or at risk of hitting a shallow, Lincoln's invention could be activated, which would inflate accordion-shaped air chambers along the sides of the watercraft to lift it above the water's surface, providing enough clearance to avoid a disaster. As part of the research process, Lincoln designed a scale model of a ship outfitted with the device. This model (built and assembled with the assistance of a mechanic from Springfield named Walter Davis) that was originally taken to the

Lincoln admired the patent law system because of the reciprocal benefits it furnished both the inventor and society. In 1859 he noted that the patent system ". . . has secured to the inventor, for a limited time, the exclusive use of his invention; and thereby added to the interest of genius in the discovery and production of new and useful things." He described the discovery of America as the most important development in the world's history, followed second by the technology of printing and third by patent laws.

Lincoln was himself a patent lawyer. He won an unreported

Lincoln admired the patent law system because of the reciprocal benefits it furnished both the inventor and society. In 1859 he noted that the patent system ". . . has secured to the inventor, for a limited time, the exclusive use of his invention; and thereby added to the interest of genius in the discovery and production of new and useful things." He described the discovery of America as the most important development in the world's history, followed second by the technology of printing and third by patent laws.

Lincoln was himself a patent lawyer. He won an unreported

Abraham Lincoln's Patent Model at the Smithsonian department of maritime history

{{Abraham Lincoln

invention

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an ...

to buoy and lift boats over shoal

In oceanography, geomorphology, and geoscience, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material and rises from the bed of a body of water to near the surface. It ...

s and obstructions in a river. Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

conceived the invention when on two occasions the boat on which he traveled got hung up on obstructions. Lincoln's device was composed of large bellows

A bellows or pair of bellows is a device constructed to furnish a strong blast of air. The simplest type consists of a flexible bag comprising a pair of rigid boards with handles joined by flexible leather sides enclosing an approximately airtig ...

attached to the sides of a boat that were expandable due to air chambers. Filed on March 10, 1849, Lincoln's patent was issued as Patent No. 6,469 later that year, on May 22. His successful patent application led to his drafting and delivering two lectures on the subject of patents while he was president.

Lincoln was at times a patent attorney

A patent attorney is an attorney who has the specialized qualifications necessary for representing clients in obtaining patents and acting in all matters and procedures relating to patent law and practice, such as filing patent applications and op ...

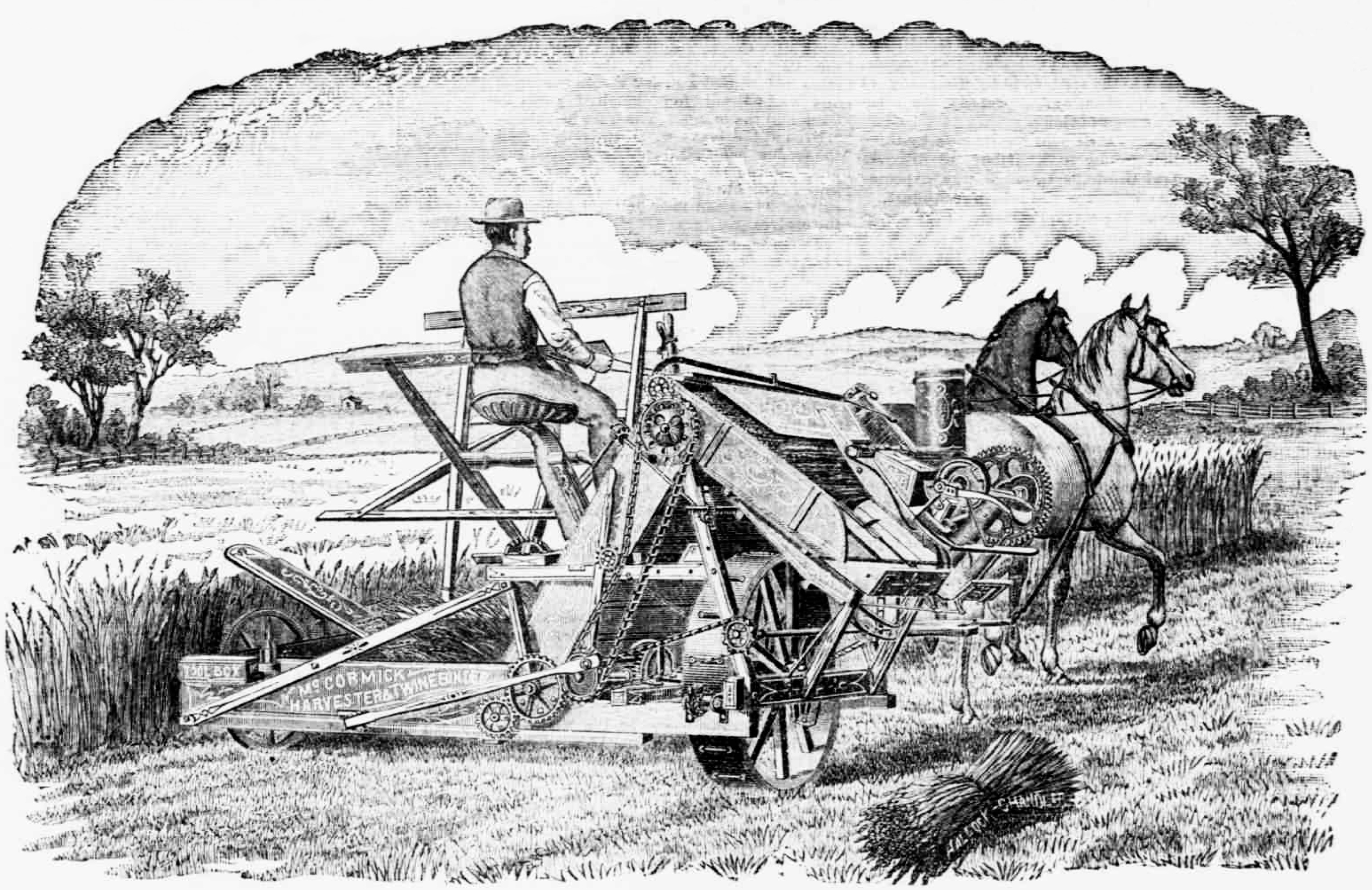

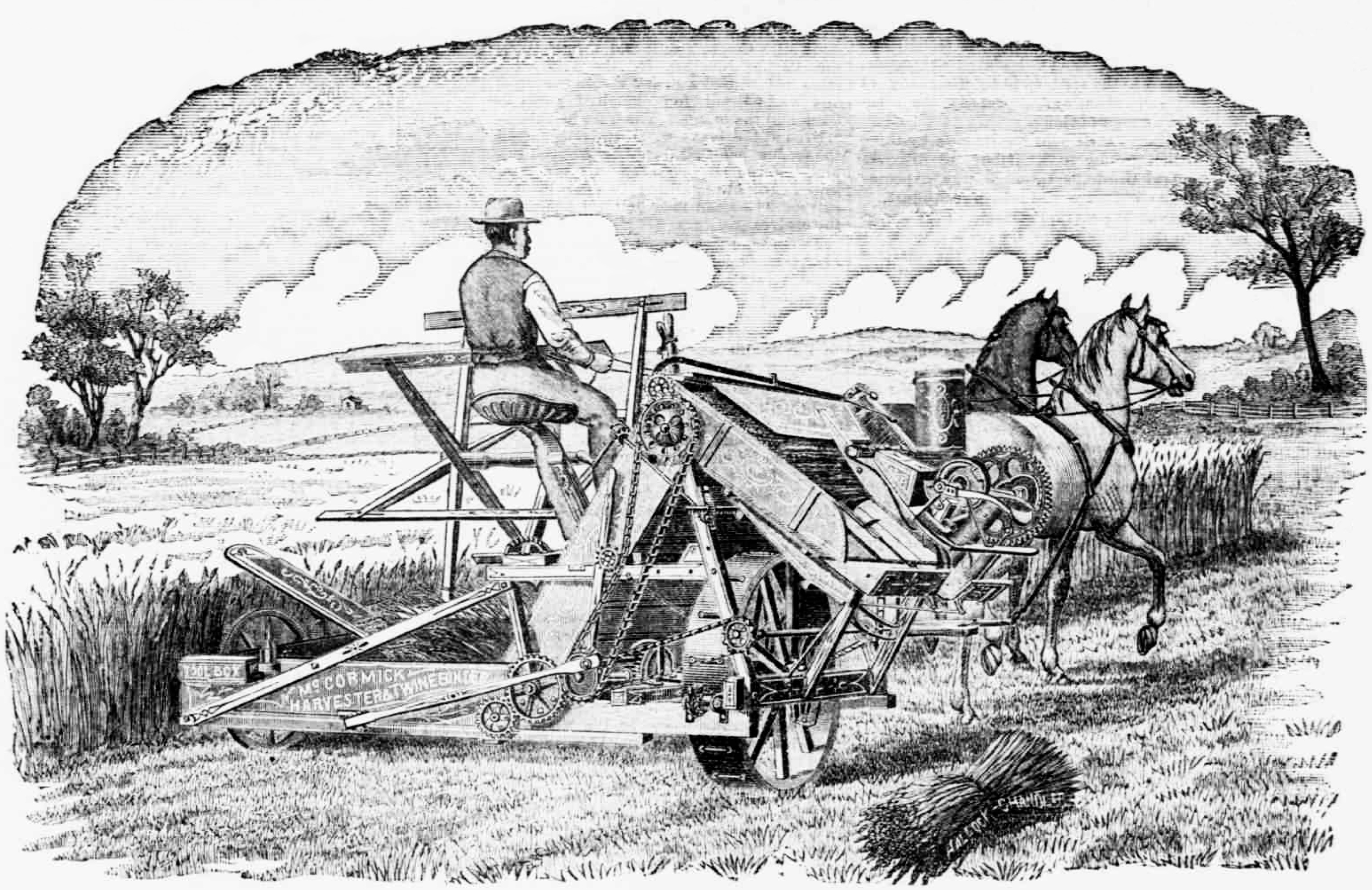

and was familiar with the patent application process as well as patent lawsuit proceedings. Among his notable patent law experiences as a result of his patent was litigation over the mechanical reaper

A reaper is a farm implement or person that reaps (cuts and often also gathers) crops at harvest when they are ripe. Usually the crop involved is a cereal grass. The first documented reaping machines were Gallic reapers that were used in Roma ...

; both he and his future Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's management helped organize ...

, provided counsel

A counsel or a counsellor at law is a person who gives advice and deals with various issues, particularly in legal matters. It is a title often used interchangeably with the title of ''lawyer''.

The word ''counsel'' can also mean advice given ...

for John Henry Manny

John Henry Manny (1825–1856) was the inventor of the Manny Reaper, one of various makes of reaper used to harvest grain in the 19th century. Cyrus McCormick III, in his ''Century of the Reaper'', called Manny "the most brilliant and successful ...

, an inventor. The original documentation of Lincoln's patent was rediscovered in 1997.

Background

The invention stemmed from Lincoln's experiences ferrying travelers and carrying freight on the

The invention stemmed from Lincoln's experiences ferrying travelers and carrying freight on the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

and some midwestern

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States. ...

rivers. In 1860, Lincoln wrote his autobiography and recounted that while in his late teens he took a flatboat

A flatboat (or broadhorn) was a rectangular flat-bottomed boat with square ends used to transport freight and passengers on inland waterways in the United States. The flatboat could be any size, but essentially it was a large, sturdy tub with a ...

down the Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

and Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

s from his home in Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

to while employed as a hired hand. The son of the boat owner kept him company and the two went out on this new undertaking without any other helpers.

Lincoln made an additional trip a few years later after moving to Macon County, Illinois, on another flatboat that went from Beardstown, Illinois

Beardstown is a city in Cass County, Illinois, United States. The population was 5,951 at the 2020 census. The public schools are in Beardstown Community Unit School District 15.

Geography

Beardstown is located at (40.012189, -90.428711) on ...

, to New Orleans. John D. Johnston (Lincoln's stepmother's son) and John Hanks John Hanks (February 9, 1802 – July 1, 1889) was Abraham Lincoln's first cousin, once removed, his mother's cousin. He was the son of William, Nancy Hanks Lincoln's uncle and grandson of Joseph Hanks.

Early years and marriage

John Hanks was b ...

were hired as additional laborers by Denton Offutt

Denton Offutt was a 19th-century American general store operator who hired future President Abraham Lincoln for his first job as an adult in New Salem, Illinois.

After Lincoln and his family had moved there from Indiana in 1830, he was hired by ...

to take a flatboat of merchandise down the Sangamon River to New Orleans. Before Offutt's boat could reach the Illinois River

The Illinois River ( mia, Inoka Siipiiwi) is a principal tributary of the Mississippi River and is approximately long. Located in the U.S. state of Illinois, it has a drainage basin of . The Illinois River begins at the confluence of the ...

, it got hung up on a milldam

A mill dam (International English) or milldam (US) is a dam constructed on a waterway to create a mill pond.

Water passing through a dam's spillway is used to turn a water wheel and provide energy to the many varieties of watermill. By raising t ...

at the Old Sangamon town seven miles northwest of Springfield. Lincoln took action, unloading some cargo to right the boat, then drilling a hole in the bow with a large auger

Auger may refer to:

Engineering

* Wood auger, a drill for making holes in wood (or in the ground)

** Auger bit, a drill bit

* Auger conveyor, a device for moving material by means of a rotating helical flighting

* Auger (platform), the world's f ...

borrowed from the local cooperage. After the water drained, he replugged the hole. With local help, he then portage

Portage or portaging (Canada: ; ) is the practice of carrying water craft or cargo over land, either around an obstacle in a river, or between two bodies of water. A path where items are regularly carried between bodies of water is also called a ...

d the empty boat over the dam, and was able to complete the trip to New Orleans.

Lincoln started his political career in New Salem. Near the top of his agenda was improvement of navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation ...

on the Sangamon River. Lincoln's law partner and biographer, William H. Herndon

William Henry Herndon (December 25, 1818 – March 18, 1891) was a law partner and biographer of President Abraham Lincoln. He was an early member of the new Republican Party and was elected mayor of Springfield, Illinois.

Early life

Herndon ...

, also reports an additional incident in 1848: a boat Lincoln came to from his steamboat was stranded on a shoal

In oceanography, geomorphology, and geoscience, a shoal is a natural submerged ridge, bank, or bar that consists of, or is covered by, sand or other unconsolidated material and rises from the bed of a body of water to near the surface. It ...

. The boat's captain ordered his crew to gather together all the empty barrels, boxes, and loose planks and force these objects under the sides of the steamboat to buoy it over the shallow water. The boat gradually swung clear and was dislodged after much manual exertion. This event, along with the Offutt's boat/milldam incident, prompted Lincoln to start thinking about how to lift vessels over river obstructions and shoals. He eventually came up with an invention to achieve this, which involved flotation bladders.

Patent

Lincoln labeled his invention ''Buoying Vessels Over Shoals'' and it was used to get them over shoals. He envisioned a system of waterproof fabric bladders that could be inflated when necessary to help ease a stuck steamboat over such obstacles. When crew members knew their ship was stuck, or at risk of hitting a shallow, Lincoln's invention could be activated, which would inflate accordion-shaped air chambers along the sides of the watercraft to lift it above the water's surface, providing enough clearance to avoid a disaster. As part of the research process, Lincoln designed a scale model of a ship outfitted with the device. This model (built and assembled with the assistance of a mechanic from Springfield named Walter Davis) that was originally taken to the

Lincoln labeled his invention ''Buoying Vessels Over Shoals'' and it was used to get them over shoals. He envisioned a system of waterproof fabric bladders that could be inflated when necessary to help ease a stuck steamboat over such obstacles. When crew members knew their ship was stuck, or at risk of hitting a shallow, Lincoln's invention could be activated, which would inflate accordion-shaped air chambers along the sides of the watercraft to lift it above the water's surface, providing enough clearance to avoid a disaster. As part of the research process, Lincoln designed a scale model of a ship outfitted with the device. This model (built and assembled with the assistance of a mechanic from Springfield named Walter Davis) that was originally taken to the United States Patent and Trademark Office

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is an agency in the U.S. Department of Commerce that serves as the national patent office and trademark registration authority for the United States. The USPTO's headquarters are in Alex ...

in Washington is now on display at the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Found ...

. At the time the patent was issued, Lincoln was a congressman. He is the only United States president to be a patentee.

After reporting to Washington for his two-year term in Congress beginning March 1847, Lincoln retained Zenas C. Robbins, patent attorney. Robbins most probably had drawings done by Robert Washington Fenwick, his apprentice artist. Robbins filed the application on March 10, 1849, which was granted as Patent No. 6,469 on May 22, 1849. Lincoln's patent is the result of Offutt's flat-boat experience he had back in 1831.

The device was never produced for practical use and there are doubts as to whether it would have actually worked. Paul Johnston, curator of the maritime history department at the Smithsonian, came to the conclusion that the version Lincoln made was not practical because it required too much force to make it operate as intended.

Lincoln took his four-year-old son Robert Todd to the Old Patent Office Building

Old or OLD may refer to:

Places

* Old, Baranya, Hungary

* Old, Northamptonshire, England

* Old Street station, a railway and tube station in London (station code OLD)

*OLD, IATA code for Old Town Municipal Airport and Seaplane Base, Old Town, ...

in 1847 to the model room to view the displays, sowing one of the youngster's fondest memories. Lincoln himself continued to have a special affinity for the site that covered two city blocks and is a columned structure much like ancient Roman architecture.

Legacy

Lincoln's exposure to the patent system, as an inventor and as a lawyer, engendered deep beliefs in its efficacy. Patent law in the United States has a constitutional foundation which is supported by the country's founders, and was viewed as an indispensable engine for economic development. It led him to draft and deliver two lectures on the subject when he was president. Lincoln had an attraction to machinelike accessories all his life, which some say was hereditary and handed down to him from his father's interest in labor-saving equipment. He made speeches on inventions before he became president. He said in 1858, "Man is not the only animal who labors; but he is the only one who improves his workmanship." Lincoln admired the patent law system because of the reciprocal benefits it furnished both the inventor and society. In 1859 he noted that the patent system ". . . has secured to the inventor, for a limited time, the exclusive use of his invention; and thereby added to the interest of genius in the discovery and production of new and useful things." He described the discovery of America as the most important development in the world's history, followed second by the technology of printing and third by patent laws.

Lincoln was himself a patent lawyer. He won an unreported

Lincoln admired the patent law system because of the reciprocal benefits it furnished both the inventor and society. In 1859 he noted that the patent system ". . . has secured to the inventor, for a limited time, the exclusive use of his invention; and thereby added to the interest of genius in the discovery and production of new and useful things." He described the discovery of America as the most important development in the world's history, followed second by the technology of printing and third by patent laws.

Lincoln was himself a patent lawyer. He won an unreported patent infringement

Patent infringement is the commission of a prohibited act with respect to a patented invention without permission from the patent holder. Permission may typically be granted in the form of a license. The definition of patent infringement may v ...

case for the defendant early in his legal career titled ''Parker v. Hoyt.'' A jury found that his client's waterwheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with a number of blades or bucke ...

did not infringe the intellectual property rights of another. A large professional fee, one of his largest, came from working on the " Reaper Case" of '' McCormick v. Manny'' and being successful with its outcome. He was co-counsel for the defendant with two aggressive and preeminent Pennsylvania patent attorneys, George Harding, and Edwin M. Stanton. Although Lincoln was prepared and well-paid, his co-counsel thought him too naive and unsophisticated to be allowed to present the argument by himself. He went home unheard, however Manny won the case in an opinion authored by Supreme Court Justice John McLean

John McLean (March 11, 1785 – April 4, 1861) was an American jurist and politician who served in the United States Congress, as U.S. Postmaster General, and as a justice of the Ohio and U.S. Supreme Courts. He was often discussed for t ...

. Upon Lincoln's taking office, he offered Harding the opportunity to become Commissioner of Patents, which was refused. He later offered the job and position of the United States Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

to Stanton, who accepted and served. Lincoln's final patent case was ''Dawson v. Ennis''. It occurred between his presidential nomination and the election. His electoral triumph was juxtaposed with a litigation loss for his client.

The original 1846 patent drawing was discovered in the Patent and Trademark Office of the director in 1997. Its only omission is the usually required inventor's signature in a lower corner. The Smithsonian Institution acquired about 10,000 patent models, including Lincoln's. The Engineering Collection includes about 75 maritime inventions; its Maritime Collections holds a replica, the original being deemed too delicate to loan out. The Smithsonian department of maritime history Historical Collections Department retains a duplicate of the original patent papers.

References

Sources

* * * * * * *Further reading

*Parkinson, Robert Henry (September 1946) ''The Patent Case that Lifted Lincoln into a Presidential Candidate'' Abraham Lincoln Quarterly (pages=105–22)External links

* - ''Manner of Buoying Vessels'' - Abraham Lincoln. 1849. (Scan of Lincoln's Patent application)Abraham Lincoln's Patent Model at the Smithsonian department of maritime history

{{Abraham Lincoln

Patent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A ...

Collection of the Smithsonian Institution

American inventions

United States patent law

1849 in the United States

History of patent law

Works by Abraham Lincoln