Abraham Geiger on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

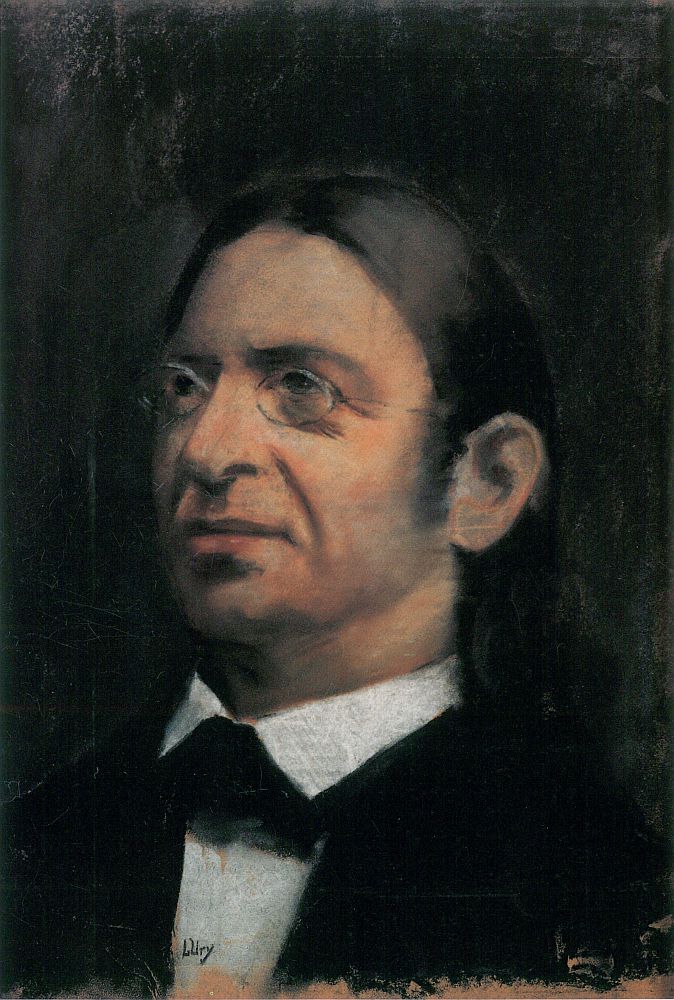

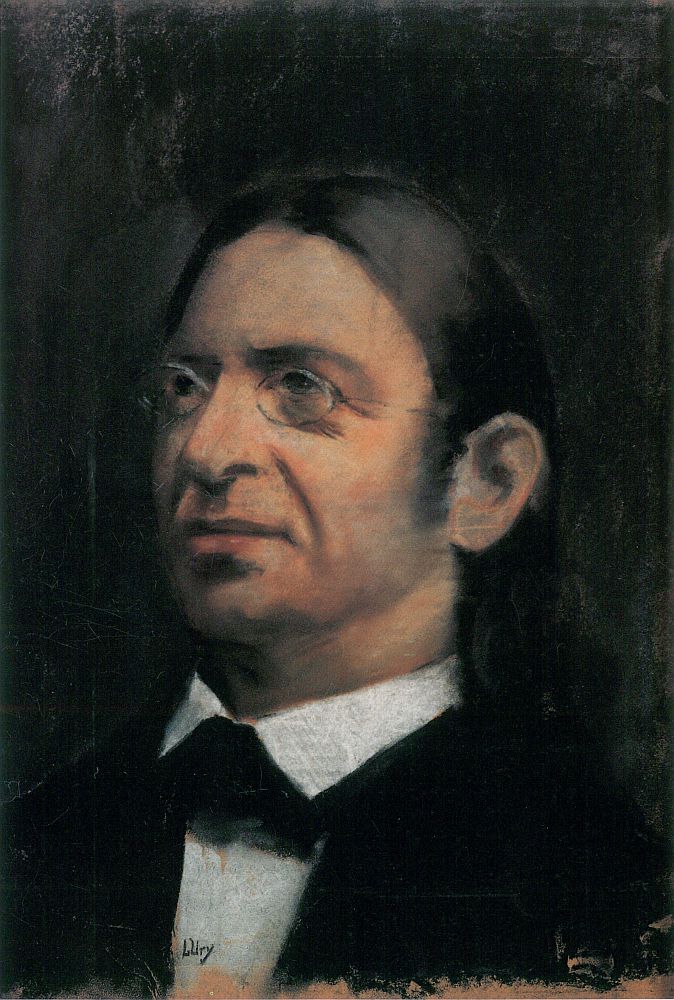

Abraham Geiger (

At this time, no university professorships were available in Germany to Jews; so, Geiger was forced to seek a position as rabbi. He found a position in the Jewish community of

At this time, no university professorships were available in Germany to Jews; so, Geiger was forced to seek a position as rabbi. He found a position in the Jewish community of

In the Germany of the 19th century, Geiger and

In the Germany of the 19th century, Geiger and

Jewish Discovery of Islam

2009 October 24) by

Works by and about Abraham Geiger in University Library JCS Frankfurt am Main: Digital Collections Judaica

Digitized works by Abraham Geiger

at the

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

: ''ʼAvrāhām Gayger''; 24 May 181023 October 1874) was a German rabbi

A rabbi () is a spiritual leader or religious teacher in Judaism. One becomes a rabbi by being ordained by another rabbi – known as ''semikha'' – following a course of study of Jewish history and texts such as the Talmud. The basic form of ...

and scholar, considered the founding father of Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major Jewish denomination that emphasizes the evolving nature of Judaism, the superiority of its ethical aspects to its ceremonial ones, and belief in a continuous searc ...

. Emphasizing Judaism's constant development along history and universalist traits, Geiger sought to re-formulate received forms and design what he regarded as a religion compliant with modern times.

Biography

As a child, Geiger started doubting the traditional understanding of Judaism when his studies in classical history seemed to contradict the biblical claims of divine authority. At the age of seventeen, he began writing his first work, a comparison between the legal style of theMishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; he, מִשְׁנָה, "study by repetition", from the verb ''shanah'' , or "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first major written collection of the Jewish oral traditions which is known as the Oral Torah ...

and Biblical and Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cente ...

ic law. He also worked on a dictionary of Mishnaic (Rabbinic) Hebrew.

Geiger's friends provided him with financial assistance which enabled him to attend the University in Heidelberg, to the great disappointment of his family. His main focus was centered on the areas of philology

Philology () is the study of language in oral and writing, written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defin ...

, Syriac Syriac may refer to:

*Syriac language, an ancient dialect of Middle Aramaic

*Sureth, one of the modern dialects of Syriac spoken in the Nineveh Plains region

* Syriac alphabet

** Syriac (Unicode block)

** Syriac Supplement

* Neo-Aramaic languages a ...

, Hebrew, and classics, but he also attended lectures in philosophy and archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

. After one semester, he transferred to the University of Bonn

The Rhenish Friedrich Wilhelm University of Bonn (german: Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn) is a public research university located in Bonn, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It was founded in its present form as the ( en, Rhine U ...

, where he studied at the same time as Samson Raphael Hirsch

Samson Raphael Hirsch (; June 20, 1808 – December 31, 1888) was a German Orthodox rabbi best known as the intellectual founder of the ''Torah im Derech Eretz'' school of contemporary Orthodox Judaism. Occasionally termed ''neo-Orthodoxy'', his ...

. Hirsch initially formed a friendship with Geiger, and with him organized a society of Jewish students for the stated purpose of practicing homiletics

In religious studies, homiletics ( grc, ὁμιλητικός ''homilētikós'', from ''homilos'', "assembled crowd, throng") is the application of the general principles of rhetoric to the specific art of public preaching. One who practices or ...

, but with the deeper intention of bringing them closer to Jewish values. It was to this society that Geiger preached his first sermon (January 2, 1830). In later years, he and Hirsch became bitter opponents as the leaders of two opposing Jewish movements.

At Bonn, Geiger began an intense study of Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

and the Koran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

, winning a prize for his essay, written originally in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, and later published in German under the title "Was hat Mohammed aus dem Judenthume aufgenommen?" ("What did Mohammed take from Judaism?"). The essay earned Geiger a doctorate at the University of Marburg

The Philipps University of Marburg (german: Philipps-Universität Marburg) was founded in 1527 by Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, which makes it one of Germany's oldest universities and the oldest still operating Protestant university in the wor ...

. It demonstrated that large parts of the Koran were taken from, or based on, rabbinic literature. (On this, see History of the Koran).

This book was Geiger's first step in a much larger intellectual project. Geiger sought to demonstrate Judaism's central influence on Christianity and Islam. He believed that neither movement possessed religious originality, but were simply a vehicle to transmit the Jewish monotheistic belief to the pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

world.

At this time, no university professorships were available in Germany to Jews; so, Geiger was forced to seek a position as rabbi. He found a position in the Jewish community of

At this time, no university professorships were available in Germany to Jews; so, Geiger was forced to seek a position as rabbi. He found a position in the Jewish community of Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden () is a city in central western Germany and the capital of the state of Hesse. , it had 290,955 inhabitants, plus approximately 21,000 United States citizens (mostly associated with the United States Army). The Wiesbaden urban area ...

(1832–1837). There, he continued his academic publications primarily through the scholarly journals he founded and edited, including ''Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift für jüdische Theologie'' (1835–1839) and ''Jüdische Zeitschrift für Wissenschaft und Leben'' (1862–1875). His journals became important vehicles in their day for publishing Jewish scholarship, chiefly historical and theological studies, as well as a discussion of contemporary events.

By that time, Geiger had begun his program of religious reforms, chiefly in the synagogue liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

. For example, he abolished the prayers of mourning for the Temple

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

, believing that since Jews were German citizens, such prayers would appear to be disloyal to the ruling power and could possibly spark anti-Semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

. Geiger was the driving force in convening several synods of reform-minded rabbis with the intention of formulating a program of progressive Judaism. However, unlike Samuel Holdheim

Samuel Holdheim (1806 – 22 August 1860) was a German rabbi and author, and one of the more extreme leaders of the early Reform Movement in Judaism. A pioneer in modern Jewish homiletics, he was often at odds with the Orthodox community.(Histo ...

, he did not want to create a separate community. Rather, his goal was to change Judaism from within.

Reformer

In the Germany of the 19th century, Geiger and

In the Germany of the 19th century, Geiger and Samuel Holdheim

Samuel Holdheim (1806 – 22 August 1860) was a German rabbi and author, and one of the more extreme leaders of the early Reform Movement in Judaism. A pioneer in modern Jewish homiletics, he was often at odds with the Orthodox community.(Histo ...

, along with Israel Jacobson

Israel Jacobson (17 October 1768, Halberstadt – 14 September 1828, Berlin) was a German-Jewish philanthropist and communal organiser. Jacobson pioneered political, educational and religious reforms in the early days of Jewish emancipation, a ...

and Leopold Zunz

Leopold Zunz ( he, יום טוב צונץ—''Yom Tov Tzuntz'', yi, ליפמן צונץ—''Lipmann Zunz''; 10 August 1794 – 17 March 1886) was the founder of academic Judaic Studies (''Wissenschaft des Judentums''), the critical investigation ...

, stood out as the founding fathers of Reform Judaism

Reform Judaism, also known as Liberal Judaism or Progressive Judaism, is a major Jewish denomination that emphasizes the evolving nature of Judaism, the superiority of its ethical aspects to its ceremonial ones, and belief in a continuous searc ...

.

Geiger was a more moderate and scholarly reformer, seeking to found this new branch of Judaism on the scientific study of history, without assuming that any Jewish text was divinely written.

Geiger was not only a scholar and researcher commenting on important subjects and characters in Jewish history – he was also a rabbi responsible for much of the reform doctrine of the mid-19th century. He contributed much of the character to the reform movement that remains today.

Reform historian Michael A. Meyer has stated that, if any one person can be called the founder of Reform Judaism, it must be Geiger.

Much of Geiger's writing has been translated into English from the original German. There have been many biographical and research texts about him, such as the work ''Abraham Geiger and the Jewish Jesus'' by Susannah Heschel

Susannah Heschel (born 15 May 1956) is an American scholar and the Eli M. Black Distinguished Professor of Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College. The author and editor of numerous books and articles, she is a Guggenheim Fellow and the recipient of ...

(1998), which chronicles Geiger's radical contention that the "New Testament" illustrates Jesus was a Pharisee teaching Judaism.

Some of Geiger's studies are included in '' The Origins of The Koran: Classic Essays on Islam's Holy Book'' edited by Ibn Warraq

Ibn Warraq is the pen name of an anonymous author critical of Islam. He is the founder of the Institute for the Secularisation of Islamic Society and used to be a senior research fellow at the Center for Inquiry, focusing on Quranic criticism. ...

. Other works are ''Judaism and Islam'' (1833), and ''An Appeal to My Community'' (1842).

Criticism

Samson Raphael Hirsch

Samson Raphael Hirsch (; June 20, 1808 – December 31, 1888) was a German Orthodox rabbi best known as the intellectual founder of the ''Torah im Derech Eretz'' school of contemporary Orthodox Judaism. Occasionally termed ''neo-Orthodoxy'', his ...

devoted a good many issues of his journal ''Jeschurun'' to criticizing Geiger's reform stance (published in English as ''Hirsch, Collected Writings'').

Some critics also attacked Geiger's opposition to a Jewish national identity; most notably, he was criticized when he refused to intervene on the behalf of the Jews of Damascus accused of ritual murder (a blood libel

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mur ...

) in 1840.

However, Jewish historian Steven Bayme has concluded that Geiger had actually vigorously protested on humanitarian grounds.Bayme, Steven (1997) ''Understanding Jewish History: Texts and Commentaries''. Jersey City, NJ: KTAV. p. 282.

Geiger and Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform Judaism

Geiger's rejection of Orthodox Judaism

To Geiger, Judaism was unique because of its monotheism and ethics. He began to identify less with the "rigidity of Talmudic legalism, developed over centuries of ghettoization inflicted by Christian Intolerance ... in medieval Christendom", that defined and confined the existence ofOrthodox Judaism

Orthodox Judaism is the collective term for the traditionalist and theologically conservative branches of contemporary Judaism. Theologically, it is chiefly defined by regarding the Torah, both Written and Oral, as revealed by God to Moses on M ...

in the 19th century in Germany. He believed that, "the Torah, as well as the Talmud, should be studied critically and from the point of view of the historian, that of evolution and development". As Geiger grew into his adolescence and young adulthood, he began to establish a more liberal approach to, and understanding of, Judaism than his traditional Orthodox Jewish background dictated. He thus rejected Orthodox Jewish tradition in favor of a liberal outlook.

Conservative Judaism's rejection of Geiger

In 1837, Geiger arranged a meeting of reform-minded rabbis in Wiesbaden for the purpose of discussing measures of concern to Judaism, and continued to be a leader of liberal German rabbinical thought through 1846. When he was nominated as a finalist for the position of Chief Rabbi in Breslau in 1838, a heated controversy sparked between conservative and liberal factions within the Jewish community. Orthodox factions accused Geiger of being a Karaite orSadducee

The Sadducees (; he, צְדוּקִים, Ṣədūqīm) were a socio- religious sect of Jewish people who were active in Judea during the Second Temple period, from the second century BCE through the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. Th ...

, and therefore prevented him from being appointed Chief Rabbi. In 1840, however, the Orthodox Rabbi of Breslau died, leading to the secession of the Orthodox faction and the appointment of Geiger as Chief Rabbi.

Throughout his time in Breslau as Chief Rabbi and after, the Positive-Historical School of Rabbi Zecharias Frankel

Zecharias Frankel, also known as Zacharias Frankel (30 September 1801 – 13 February 1875) was a Bohemian-German rabbi and a historian who studied the historical development of Judaism. He was born in Prague and died in Breslau. He was the foun ...

continued to reject Geiger's philosophies. In 1841, he and Frankel clashed at the second Hamburg Temple dispute. When the Jewish Theological Seminary was founded there in 1854, thanks in part to Geiger's efforts, he was not appointed to its faculty, though he had long been at the fore-front of attempts to establish a faculty of Jewish theology. More conservatives regarded Geiger's theological stance as too liberal. Therefore, in 1863, Geiger left Breslau to become a Rabbi of Liberal communities in Frankfurt and, later, Berlin. "Ultimately, in 1871, he was appointed to the faculty of the newly founded Reform rabbinical college in Berlin, Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums

Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums, or Higher Institute for Jewish Studies, was a rabbinical seminary established in Berlin in 1872 and closed down by the Nazi government of Germany in 1942. Upon the order of the government, the name ...

, where he spent his final years."

A new approach to Reform Judaism

Initially, Reform Judaism grew out of some Jews being uninterested in the "strict observances required of Orthodoxy", and an attempt to alter the appearance and ritual of Judaism to mimic German Protestantism. Geiger, however, turned to a more "coherent ideological framework to justify innovations in the liturgy and religious practice". Geiger argued that, "Reform Judaism was not a rejection of earlier Judaism, but a recovery of the Pharisaic halakhic tradition, which is nothing other than the principle of continual further development in accord with the times, the principle of not being slaves to the letter of the Bible, but rather to witness over and over its spirit and its authentic faith-consciousness."See also

*Lazarus Geiger

Lazarus Geiger (21 May 1829 – 29 August 1870) was a German-Jewish philosopher and philologist.

Life

He was born at Frankfurt-on-Main, was destined to commerce, but soon gave himself up to scholarship and studied at Marburg, Bonn and Heidelberg. ...

* History of the Koran

References

Geiger's works

* ''Was hat Mohammed aus dem Judentume aufgenommen?'' Bonn, 1833. : (translated as '' Judaism and Islam: A Prize Essay'', F. M. Young, 1896). * ''Das Judenthum und seine Geschichte von der Zerstörung des zweiten Tempels bis zum Ende des zwölften Jahrhunderts. In zwölf Vorlesungen. Nebst einem Anhange: Offenes Sendschreiben an Herrn Professor Dr. Holtzmann''. Breslau: Schletter, 1865-71. : (translated as ''Judaism and its history: in 2 parts'', Lanham .a. Univ. Press of America, 1985. ). * ''Nachgelassene Schriften''. Reprint of the 1875–1878 ed., published in Berlin by L. Gerschel. Bd 1-5. New York: Arno Press, 1980. * ''Urschrift und uebersetzungen der Bibel in ihrer abhängigkeit von der innern entwickelung des Judenthums''. Breslau: Hainauer, 1857.Secondary literature

*Susannah Heschel

Susannah Heschel (born 15 May 1956) is an American scholar and the Eli M. Black Distinguished Professor of Jewish Studies at Dartmouth College. The author and editor of numerous books and articles, she is a Guggenheim Fellow and the recipient of ...

: ''Abraham Geiger and the Jewish Jesus''. Chicago; London: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1998. (Chicago studies in the history of Judaism). .

* Ludwig Geiger

Ludwig Geiger (born ''Lazarus Abraham Geiger'', also called ''Ludwig Moritz Philipp Geiger''; 5 June 1848 – 9 February 1919) was a German author and historian.

Life

Ludwig Geiger was born at Breslau, Silesia, a son of Abraham Geiger. After st ...

: ''Abraham Geiger. Leben und Werk für ein Judentum in der Moderne''. Berlin: JVB, 2001. .

* Christian Wiese (ed.) ''Jüdische Existenz in der Moderne: Abraham Geiger und die Wissenschaft des Judentums'' (German and English), deGruyter, Berlin 2013,

* Hartmut Bomhoff: ''Abraham Geiger - durch Wissen zum Glauben - Through reason to faith: reform and the science of Judaism''. (Text dt. und engl.). Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin, Centrum Judaicum. Jüdische Miniaturen ; Bd. 45. Berlin: Hentrich und Hentrich 2006.

* Jobst Paul (2006): "Das 'Konvergenz'-Projekt – Humanitätsreligion und Judentum im 19. Jahrhundert". In: Margarete Jäger, Jürgen Link (Hg.): ''Macht – Religion – Politik. Zur Renaissance religiöser Praktiken und Mentalitäten''. Münster 2006.

*

* ''Abraham Geiger and liberal Judaism: The challenge of the 19th century''. Compiled with a biographical introduction by Max Wiener. Translated from the German by Ernst J. Schlochauer. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America 5722.

Footnotes

Attribution * *External links

*Jewish Discovery of Islam

2009 October 24) by

Martin Kramer

Martin Seth Kramer (Hebrew: מרטין קרמר; born September 9, 1954, Washington, D.C.) is an American-Israeli scholar of the Middle East at Tel Aviv University and the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. His focus is on the history an ...

, includes discussion of Geiger.

Works by and about Abraham Geiger in University Library JCS Frankfurt am Main: Digital Collections Judaica

Digitized works by Abraham Geiger

at the

Leo Baeck Institute, New York

The Leo Baeck Institute New York (LBI) is a research institute in New York City dedicated to the study of German-Jewish history and culture, founded in 1955. It is one of three independent research centers founded by a group of German-speaking J ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Geiger, Abraham

1810 births

1874 deaths

Rabbis from Frankfurt

German Reform rabbis

German orientalists

University of Bonn alumni

Historians of Islam

German Jewish theologians

German male non-fiction writers

Rabbis from Wrocław

19th-century German rabbis

Founders of new religious movements