Abelard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Peter Abelard (; french: link=no, Pierre Abélard; la, Petrus Abaelardus or ''Abailardus''; 21 April 1142) was a

Around 1100, Abelard's travels brought him to Paris. Around this time he changed his surname to Abelard, sometimes written Abailard or Abaelardus. The etymological root of Abelard could be the Middle French ('ability'), the Hebrew name ''Abel/Habal'' (breath/vanity/figure in Genesis), the English ''apple'' or the Latin ('to dance'). The name is jokingly referenced as relating to lard, as in excessive ("fatty") learning, in a secondary anecdote referencing

Around 1100, Abelard's travels brought him to Paris. Around this time he changed his surname to Abelard, sometimes written Abailard or Abaelardus. The etymological root of Abelard could be the Middle French ('ability'), the Hebrew name ''Abel/Habal'' (breath/vanity/figure in Genesis), the English ''apple'' or the Latin ('to dance'). The name is jokingly referenced as relating to lard, as in excessive ("fatty") learning, in a secondary anecdote referencing

Héloïse d'Argenteuil lived within the precincts of Notre-Dame, under the care of her uncle, the secular

Héloïse d'Argenteuil lived within the precincts of Notre-Dame, under the care of her uncle, the secular

To appease Fulbert, Abelard proposed a marriage. Héloïse initially opposed marriage, but to appease her worries about Abelard's career prospects as a married philosopher, the couple were married in secret. (At this time, clerical celibacy was becoming the standard at higher levels in the church orders.)

To avoid suspicion of involvement with Abelard, Heloise continued to stay at the house of her uncle. When Fulbert publicly disclosed the marriage, Héloïse vehemently denied it, arousing Fulbert's wrath and abuse. Abelard rescued her by sending her to the convent at

To appease Fulbert, Abelard proposed a marriage. Héloïse initially opposed marriage, but to appease her worries about Abelard's career prospects as a married philosopher, the couple were married in secret. (At this time, clerical celibacy was becoming the standard at higher levels in the church orders.)

To avoid suspicion of involvement with Abelard, Heloise continued to stay at the house of her uncle. When Fulbert publicly disclosed the marriage, Héloïse vehemently denied it, arousing Fulbert's wrath and abuse. Abelard rescued her by sending her to the convent at

Abelard remained at the Paraclete for about five years. His combination of the teaching of secular arts with his profession as a monk was heavily criticized by other men of religion, and Abelard contemplated flight outside Christendom altogether. Abelard therefore decided to leave and find another refuge, accepting sometime between 1126 and 1128 an invitation to preside over the Abbey of

Abelard remained at the Paraclete for about five years. His combination of the teaching of secular arts with his profession as a monk was heavily criticized by other men of religion, and Abelard contemplated flight outside Christendom altogether. Abelard therefore decided to leave and find another refuge, accepting sometime between 1126 and 1128 an invitation to preside over the Abbey of  Lack of success at St. Gildas made Abelard decide to take up public teaching again (although he remained for a few more years, officially, Abbot of St. Gildas). It is not entirely certain what he then did, but given that

Lack of success at St. Gildas made Abelard decide to take up public teaching again (although he remained for a few more years, officially, Abbot of St. Gildas). It is not entirely certain what he then did, but given that

Abelard was first buried at St. Marcel, but his remains were soon carried off secretly to the Paraclete, and given over to the loving care of Héloïse, who in time came herself to rest beside them in 1163.

The bones of the pair were moved more than once afterwards, but they were preserved even through the vicissitudes of the

Abelard was first buried at St. Marcel, but his remains were soon carried off secretly to the Paraclete, and given over to the loving care of Héloïse, who in time came herself to rest beside them in 1163.

The bones of the pair were moved more than once afterwards, but they were preserved even through the vicissitudes of the

Abelard is considered one of the founders of the secular university and pre-Renaissance secular philosophical thought.

Abelard argued for

Abelard is considered one of the founders of the secular university and pre-Renaissance secular philosophical thought.

Abelard argued for

The story of Abelard and Héloïse has proved immensely popular in modern European culture. This story is known almost entirely from a few sources: first, the ''Historia Calamitatum; ''secondly, the seven letters between Abelard and Héloïse which survive (three written by Abelard, and four by Héloïse), and always follow the ''Historia Calamitatum'' in the manuscript tradition; thirdly, four letters between Peter the Venerable and Héloïse (three by Peter, one by Héloïse). They are, in modern times, the best known and most widely translated parts of Abelard's work.

It is unclear quite how the letters of Abelard and Héloïse came to be preserved. There are brief and factual references to their relationship by 12th-century writers including William Godel and

The story of Abelard and Héloïse has proved immensely popular in modern European culture. This story is known almost entirely from a few sources: first, the ''Historia Calamitatum; ''secondly, the seven letters between Abelard and Héloïse which survive (three written by Abelard, and four by Héloïse), and always follow the ''Historia Calamitatum'' in the manuscript tradition; thirdly, four letters between Peter the Venerable and Héloïse (three by Peter, one by Héloïse). They are, in modern times, the best known and most widely translated parts of Abelard's work.

It is unclear quite how the letters of Abelard and Héloïse came to be preserved. There are brief and factual references to their relationship by 12th-century writers including William Godel and

and Theologia 'scholarium' ''. His main work on systematic theology, written between 1120 and 1140, and which appeared in a number of versions under a number of titles (shown in chronological order)

* ''Dialogus inter philosophum, Judaeum, et Christianum'', (Dialogue of a Philosopher with a Jew and a Christian) 1136–1139.

* ''Ethica'' or ''Scito Te Ipsum ''("Ethics" or "Know Yourself"), before 1140.

*

*

New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia: Peter Abelard

Jewish Encyclopedia: Peter Abelard

* ttp://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/history/inourtime/inourtime_20050505.shtml Abelard and Héloïsefrom ''In Our Time''

''The Love Letters of Abelard and Héloïse''

Trans. by Anonymous (1901). * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Abelard, Peter 1070s births 1142 deaths 11th-century Breton people 12th-century Breton people 12th-century French philosophers 12th-century French composers 12th-century French poets 12th-century French Catholic theologians 12th-century Latin writers People from Loire-Atlantique Medieval French theologians Burials at Père Lachaise Cemetery Castrated people Medieval Latin poets French logicians Linguists from France Philosophers of language Scholastic philosophers French Benedictines Benedictine philosophers Christian ethicists Medieval Paris French male poets French classical composers French male classical composers Medieval male composers Empiricists Limbo

medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

French scholastic philosopher, leading logician

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premises ...

, theologian, poet, composer and musician. This source has a detailed description of his philosophical work.

In philosophy he is celebrated for his logical solution to the problem of universals

The problem of universals is an ancient question from metaphysics that has inspired a range of philosophical topics and disputes: Should the properties an object has in common with other objects, such as color and shape, be considered to exist be ...

via nominalism

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are at least two main versions of nominalism. One version denies the existence of universalsthings ...

and conceptualism

In metaphysics, conceptualism is a theory that explains universality of particulars as conceptualized frameworks situated within the thinking mind. Intermediate between nominalism and realism, the conceptualist view approaches the metaphysical co ...

and his pioneering of intent

Intentions are mental states in which the agent commits themselves to a course of action. Having the plan to visit the zoo tomorrow is an example of an intention. The action plan is the ''content'' of the intention while the commitment is the ''a ...

in ethics. Often referred to as the " Descartes of the twelfth century", he is considered a forerunner of Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

, Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aest ...

, and Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, ...

. He is sometimes credited as a chief forerunner of modern empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

.

In history and popular culture, he is best known for his passionate and tragic love affair, and intense philosophical exchange, with his brilliant student and eventual wife, Héloïse d'Argenteuil. He was a defender of women and of their education. After having sent Héloïse to a convent

A convent is a community of monks, nuns, religious brothers or, sisters or priests. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community. The word is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Angl ...

in Brittany to protect her from her abusive uncle who did not want her to pursue this forbidden love, he was castrated

Castration is any action, surgical, chemical, or otherwise, by which an individual loses use of the testicles: the male gonad. Surgical castration is bilateral orchiectomy (excision of both testicles), while chemical castration uses pharmac ...

by men sent by this uncle. Still considering herself as his spouse even though both retired to monasteries after this event, Héloïse publicly defended him when his doctrine was condemned by Pope Innocent II

Pope Innocent II ( la, Innocentius II; died 24 September 1143), born Gregorio Papareschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 February 1130 to his death in 1143. His election as pope was controversial and the fi ...

and Abelard was therefore considered, at that time, a heretic. Among these opinions, Abelard professed the innocence of a woman who commits a sin out of love.

In Catholic theology

Catholic theology is the understanding of Catholic doctrine or teachings, and results from the studies of theologians. It is based on Biblical canon, canonical Catholic Bible, scripture, and sacred tradition, as interpreted authoritatively by ...

, he is best known for his development of the concept of limbo

In Catholic theology, Limbo (Latin '' limbus'', edge or boundary, referring to the edge of Hell) is the afterlife condition of those who die in original sin without being assigned to the Hell of the Damned. Medieval theologians of Western Euro ...

, and his introduction of the moral influence theory of atonement

The moral influence or moral example theory of atonement, developed or most notably propagated by Abelard (1079–1142), is an alternative to Anselm's satisfaction theory of atonement. Abelard focused on changing man's perception of God as not ...

. He is considered (alongside Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

) to be the most significant forerunner of the modern self-reflective autobiographer. He paved the way and set the tone for later epistolary novel

An epistolary novel is a novel written as a series of letters. The term is often extended to cover novels that intersperse documents of other kinds with the letters, most commonly diary entries and newspaper clippings, and sometimes considered ...

s and celebrity tell-alls with his publicly distributed letter, '' The History of My Calamities'', and public correspondence.

In law, Abelard stressed that, because the subjective intention determines the moral value of human action, the legal consequence of an action is related to the person that commits it and not merely to the action. With this doctrine, Abelard created in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

the idea of the individual subject central to modern law. This eventually gave to School of Notre-Dame de Paris (later the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

) a recognition for its expertise in the area of Law (and later led to the creation of a faculty of law

A faculty is a division within a university or college comprising one subject area or a group of related subject areas, possibly also delimited by level (e.g. undergraduate). In American usage such divisions are generally referred to as colleges ...

in Paris).

Life and career

Youth

Abelard, originally called "Pierre le Pallet", was born in Le Pallet, about 10 miles (16 km) east ofNantes

Nantes (, , ; Gallo: or ; ) is a city in Loire-Atlantique on the Loire, from the Atlantic coast. The city is the sixth largest in France, with a population of 314,138 in Nantes proper and a metropolitan area of nearly 1 million inhabita ...

, in the Duchy of Brittany

The Duchy of Brittany ( br, Dugelezh Breizh, ; french: Duché de Bretagne) was a medieval feudal state that existed between approximately 939 and 1547. Its territory covered the northwestern peninsula of Europe, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean ...

, the eldest son of a minor noble French family. As a boy, he learned quickly. His father, a knight called Berenger, encouraged Abelard to study the liberal arts

Liberal arts education (from Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as La ...

, wherein he excelled at the art of dialectic

Dialectic ( grc-gre, διαλεκτική, ''dialektikḗ''; related to dialogue; german: Dialektik), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing ...

(a branch of philosophy). Instead of entering a military career, as his father had done, Abelard became an academic.

During his early academic pursuits, Abelard wandered throughout France, debating and learning, so as (in his own words) "he became such a one as the Peripatetics

The Peripatetic school was a school of philosophy in Ancient Greece. Its teachings derived from its founder, Aristotle (384–322 BC), and ''peripatetic'' is an adjective ascribed to his followers.

The school dates from around 335 BC when Aristo ...

." He first studied in the Loire

The Loire (, also ; ; oc, Léger, ; la, Liger) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world. With a length of , it drains , more than a fifth of France's land, while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhôn ...

area, where the nominalist

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are at least two main versions of nominalism. One version denies the existence of universalsthings th ...

Roscellinus

Roscelin of Compiègne (), better known by his Latinized name Roscellinus Compendiensis or Rucelinus, was a French philosopher and theologian, often regarded as the founder of nominalism.

Biography

Roscellinus was born in Compiègne, France. L ...

of Compiègne

Compiègne (; pcd, Compiène) is a commune in the Oise department in northern France. It is located on the river Oise. Its inhabitants are called ''Compiégnois''.

Administration

Compiègne is the seat of two cantons:

* Compiègne-1 (with ...

, who had been accused of heresy by Anselm, was his teacher during this period.

Rise to fame

Around 1100, Abelard's travels brought him to Paris. Around this time he changed his surname to Abelard, sometimes written Abailard or Abaelardus. The etymological root of Abelard could be the Middle French ('ability'), the Hebrew name ''Abel/Habal'' (breath/vanity/figure in Genesis), the English ''apple'' or the Latin ('to dance'). The name is jokingly referenced as relating to lard, as in excessive ("fatty") learning, in a secondary anecdote referencing

Around 1100, Abelard's travels brought him to Paris. Around this time he changed his surname to Abelard, sometimes written Abailard or Abaelardus. The etymological root of Abelard could be the Middle French ('ability'), the Hebrew name ''Abel/Habal'' (breath/vanity/figure in Genesis), the English ''apple'' or the Latin ('to dance'). The name is jokingly referenced as relating to lard, as in excessive ("fatty") learning, in a secondary anecdote referencing Adelard of Bath

Adelard of Bath ( la, Adelardus Bathensis; 1080? 1142–1152?) was a 12th-century English natural philosopher. He is known both for his original works and for translating many important Arabic and Greek scientific works of astrology, astronom ...

and Peter Abelard (and in which they are confused to be one person).

In the great cathedral school of Notre-Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame de Paris (; meaning "Our Lady of Paris"), referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a Middle Ages#Art and architecture, medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the Seine River), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris ...

(before the construction of the current cathedral there), he studied under Paris archdeacon and Notre-Dame master William of Champeaux, later bishop of Chalons, a disciple of Anselm of Laon

Anselm of Laon ( la, Anselmus; 1117), properly Ansel ('), was a French theologian and founder of a school of scholars who helped to pioneer biblical hermeneutics.

Biography

Born of very humble parents at Laon before the middle of the 11th cent ...

(not to be confused with Saint Anselm

Anselm of Canterbury, OSB (; 1033/4–1109), also called ( it, Anselmo d'Aosta, link=no) after his birthplace and (french: Anselme du Bec, link=no) after his monastery, was an Italian Benedictine monk, abbot, philosopher and theologian of th ...

), a leading proponent of philosophical realism

Philosophical realism is usually not treated as a position of its own but as a stance towards other subject matters. Realism about a certain kind of thing (like numbers or morality) is the thesis that this kind of thing has ''mind-independent e ...

. Retrospectively, Abelard portrays William as having turned from approval to hostility when Abelard proved soon able to defeat his master in argument. This resulted in a long duel that eventually ended in the downfall of the theory of realism which was replaced by Abelard's theory of conceptualism

In metaphysics, conceptualism is a theory that explains universality of particulars as conceptualized frameworks situated within the thinking mind. Intermediate between nominalism and realism, the conceptualist view approaches the metaphysical co ...

/ nominalism

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are at least two main versions of nominalism. One version denies the existence of universalsthings ...

. While Abelard's thought was closer to William's thought than this account might suggest,. William thought Abelard was too arrogant. It was during this time that Abelard would provoke quarrels with both William and Roscellinus.

Against opposition from the metropolitan teacher, Abelard set up his own school, first at Melun

Melun () is a commune in the Seine-et-Marne department in the Île-de-France region, north-central France. It is located on the southeastern outskirts of Paris, about from the centre of the capital. Melun is the prefecture of the Seine-et-Ma ...

, a favoured royal residence, then, around 1102–4, for more direct competition, he moved to Corbeil, nearer Paris. His teaching was notably successful, but the stress taxed his constitution, leading to a nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitt ...

and a trip home to Brittany for several years of recovery.

On his return, after 1108, he found William lecturing at the hermitage of Saint-Victor, just outside the Île de la Cité, and there they once again became rivals, with Abelard challenging William over his theory of universals. Abelard was once more victorious, and Abelard was almost able to attain the position of master at Notre Dame. For a short time, however, William was able to prevent Abelard from lecturing in Paris. Abelard accordingly was forced to resume his school at Melun, which he was then able to move, from , to Paris itself, on the heights of Montagne Sainte-Geneviève

The Montagne Sainte-Geneviève is a hill overlooking the left bank of the Seine in the 5th arrondissement of Paris. It was known to the ancient Romans as .Hilaire Belloc, '' Paris (Methuen & Company, 1900)'' Retrieved June 14, 2016 Atop the Mon ...

, overlooking Notre-Dame.Robertson,

From his success in dialectic, he next turned to theology and in 1113 moved to Laon

Laon () is a city in the Aisne department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

History

Early history

The holy district of Laon, which rises a hundred metres above the otherwise flat Picardy plain, has always held strategic importance. ...

to attend the lectures of Anselm on Biblical exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Biblical works. In modern usage, exegesis can involve critical interpretation ...

and Christian doctrine. Unimpressed by Anselm's teaching, Abelard began to offer his own lectures on the book of Ezekiel. Anselm forbade him to continue this teaching. Abelard returned to Paris where, in around 1115, he became master of the cathedral school of Notre-Dame and a canon of Sens

Sens () is a commune in the Yonne department in Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in north-central France, 120 km from Paris.

Sens is a sub-prefecture and the second city of the department, the sixth in the region. It is crossed by the Yonne an ...

(the cathedral of the archdiocese to which Paris belonged).

Héloïse

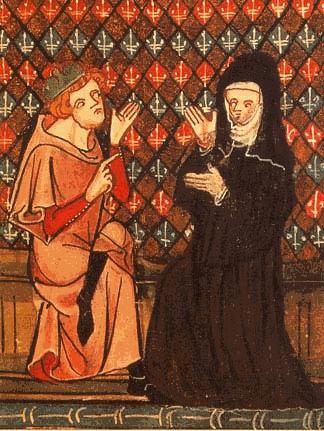

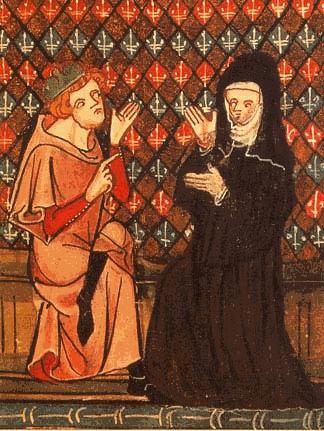

Héloïse d'Argenteuil lived within the precincts of Notre-Dame, under the care of her uncle, the secular

Héloïse d'Argenteuil lived within the precincts of Notre-Dame, under the care of her uncle, the secular canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the conceptual material accepted as official in a fictional universe by its fan base

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western ca ...

Fulbert. She was famous as the most well-educated and intelligent woman in Paris, renowned for her knowledge of classical letters, including not only Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

but also Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

.

At the time Heloise met Abelard, he was surrounded by crowds — supposedly thousands of students — drawn from all countries by the fame of his teaching. Enriched by the offerings of his pupils, and entertained with universal admiration, he came to think of himself as the only undefeated philosopher in the world. But a change in his fortunes was at hand. In his devotion to science, he claimed to have lived a very straight and narrow life, enlivened only by philosophical debate: now, at the height of his fame, he encountered romance.

Upon deciding to pursue Héloïse, Abelard sought a place in Fulbert's house, and by in 1115 or 1116 began an affair. While in his autobiography he describes the relationship as a seduction, Heloise's letters contradict this and instead depict a relationship of equals kindled by mutual attraction. Abelard boasted of his conquest using example phrases in his teaching such as "Peter loves his girl" and writing popular poems and songs of his love that spread throughout the country. Once Fulbert found out, he separated them, but they continued to meet in secret. Héloïse became pregnant and was sent by Abelard to be looked after by his family in Brittany, where she gave birth to a son, whom she named Astrolabe, after the scientific instrument

A scientific instrument is a device or tool used for scientific purposes, including the study of both natural phenomena and theoretical research.

History

Historically, the definition of a scientific instrument has varied, based on usage, laws, a ...

.

Tragic events

To appease Fulbert, Abelard proposed a marriage. Héloïse initially opposed marriage, but to appease her worries about Abelard's career prospects as a married philosopher, the couple were married in secret. (At this time, clerical celibacy was becoming the standard at higher levels in the church orders.)

To avoid suspicion of involvement with Abelard, Heloise continued to stay at the house of her uncle. When Fulbert publicly disclosed the marriage, Héloïse vehemently denied it, arousing Fulbert's wrath and abuse. Abelard rescued her by sending her to the convent at

To appease Fulbert, Abelard proposed a marriage. Héloïse initially opposed marriage, but to appease her worries about Abelard's career prospects as a married philosopher, the couple were married in secret. (At this time, clerical celibacy was becoming the standard at higher levels in the church orders.)

To avoid suspicion of involvement with Abelard, Heloise continued to stay at the house of her uncle. When Fulbert publicly disclosed the marriage, Héloïse vehemently denied it, arousing Fulbert's wrath and abuse. Abelard rescued her by sending her to the convent at Argenteuil

Argenteuil () is a commune in the northwestern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the center of Paris. Argenteuil is a sub-prefecture of the Val-d'Oise department, the seat of the arrondissement of Argenteuil.

Argenteuil is the sec ...

, where she had been brought up, to protect her from her uncle. Héloïse dressed as a nun and shared the nun's life, though she was not consecrated.

Fulbert, infuriated that Heloise had been taken from his house and possibly believing that Abelard had disposed of her at Argenteuil in order to be rid of her, arranged for a band of men to break into Abelard's room one night and castrate

Castration is any action, surgical, chemical, or otherwise, by which an individual loses use of the testicles: the male gonad. Surgical castration is bilateral orchiectomy (excision of both testicles), while chemical castration uses pharmace ...

him. In legal retribution for this vigilante attack, members of the band were punished, and Fulbert, scorned by the public, took temporary leave of his canon duties (he does not appear again in the Paris cartularies for several years).

In shame of his injuries, Abelard retired permanently as a Notre Dame canon, with any career as a priest or ambitions for higher office in the church shattered by his loss of manhood. He effectively hid himself as a monk at the monastery of St. Denis, near Paris, avoiding the questions of his horrified public. Roscellinus

Roscelin of Compiègne (), better known by his Latinized name Roscellinus Compendiensis or Rucelinus, was a French philosopher and theologian, often regarded as the founder of nominalism.

Biography

Roscellinus was born in Compiègne, France. L ...

and Fulk of Deuil ridiculed and belittled Abelard for being castrated.

Upon joining the monastery at St. Denis, Abelard insisted that Héloïse take vows as a nun (she had few other options at the time). Héloïse protested her separation from Abelard, sending numerous letters re-initiating their friendship and demanding answers to theological questions concerning her new vocation.

Astrolabe, son of Abelard and Heloise

Shortly after the birth of their child, Astrolabe, Heloise and Abelard were both cloistered. Their son was thus brought up by Abelard's sister (''soror''), Denise, at Abelard's childhood home in Le Pallet. His name derives from theastrolabe

An astrolabe ( grc, ἀστρολάβος ; ar, ٱلأَسْطُرلاب ; persian, ستارهیاب ) is an ancient astronomical instrument that was a handheld model of the universe. Its various functions also make it an elaborate inclin ...

, a Persian astronomical instrument said to elegantly model the universe and which was popularized in France by Adelard of Bath

Adelard of Bath ( la, Adelardus Bathensis; 1080? 1142–1152?) was a 12th-century English natural philosopher. He is known both for his original works and for translating many important Arabic and Greek scientific works of astrology, astronom ...

. He is mentioned in Abelard's poem to his son, the Carmen Astralabium, and by Abelard's protector, Peter the Venerable

Peter the Venerable ( – 25 December 1156), also known as Peter of Montboissier, was the abbot of the Benedictine abbey of Cluny. He has been honored as a saint, though he was never canonized in the Middle Ages. Since in 1862 Pope Pius IX c ...

of Cluny

Cluny () is a commune in the eastern French department of Saône-et-Loire, in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is northwest of Mâcon.

The town grew up around the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded by Duke William I of Aquitaine in ...

, who wrote to Héloise: "I will gladly do my best to obtain a prebend

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of t ...

in one of the great churches for your Astrolabe, who is also ours for your sake".

'Petrus Astralabius' is recorded at the Cathedral of Nantes in 1150, and the same name appears again later at the Cistercian abbey at Hauterive in what is now Switzerland. Given the extreme eccentricity of the name, it is almost certain these references refer to the same person. Astrolabe is recorded as dying in the Paraclete necrology on 29 or 30 October, year unknown, appearing as "Petrus Astralabius magistri nostri Petri filius".

Later life

In his early forties, Abelard sought to bury himself as a monk of theAbbey of Saint-Denis

The Basilica of Saint-Denis (french: Basilique royale de Saint-Denis, links=no, now formally known as the ) is a large former medieval abbey church and present cathedral in the commune of Saint-Denis, a northern suburb of Paris. The building ...

with his woes out of sight. Finding no respite in the cloister

A cloister (from Latin ''claustrum'', "enclosure") is a covered walk, open gallery, or open arcade running along the walls of buildings and forming a quadrangle or garth. The attachment of a cloister to a cathedral or church, commonly against ...

, and having gradually turned again to study, he gave in to urgent entreaties, and reopened his school at an unknown priory owned by the monastery. His lectures, now framed in a devotional spirit, and with lectures on theology as well as his previous lectures on logic, were once again heard by crowds of students, and his old influence seemed to have returned. Using his studies of the Bible and — in his view — inconsistent writings of the leaders of the church as his basis, he wrote ''Sic et Non

{{Italic title

''Sic et Non'', an early scholasticism, scholastic text whose title translates from Medieval Latin as ''"Yes and No"'', was written by Peter Abelard. In the work, Abelard juxtaposes apparently contradictory quotations from the Churc ...

'' (''Yes and No'').

No sooner had he published his theological lectures (the ''Theologia Summi Boni'') than his adversaries picked up on his rationalistic interpretation of the Trinitarian dogma. Two pupils of Anselm of Laon

Anselm of Laon ( la, Anselmus; 1117), properly Ansel ('), was a French theologian and founder of a school of scholars who helped to pioneer biblical hermeneutics.

Biography

Born of very humble parents at Laon before the middle of the 11th cent ...

, Alberich of Reims

Alberich of Reims ( 1085 – 1141) was a scholar who studied under Anselm of Laon and later became an opponent of Peter Abelard.

He was originally from Reims, but moved to nearby Laon to study under Anselm and his brother Ralph. When Anselm died ...

and Lotulf of Lombardy, instigated proceedings against Abelard, charging him with the heresy of Sabellius

Sabellius (fl. ca. 215) was a third-century priest and theologian who most likely taught in Rome, but may have been a North African from Libya. Basil and others call him a Libyan from Pentapolis, but this seems to rest on the fact that Pentapolis ...

in a provincial synod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word '' synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin word mean ...

held at Soissons

Soissons () is a commune in the northern French department of Aisne, in the region of Hauts-de-France. Located on the river Aisne, about northeast of Paris, it is one of the most ancient towns of France, and is probably the ancient capital o ...

in 1121. Through irregular procedures, they obtained an official condemnation of his teaching, and Abelard was made to burn the ''Theologia'' himself. He was then sentenced to perpetual confinement in a monastery other than his own, but it seems to have been agreed in advance that this sentence would be revoked almost immediately, because after a few days in the convent of St. Medard at Soissons, Abelard returned to St. Denis.

Life in his own monastery proved no more congenial than before. For this Abelard himself was partly responsible. He took a sort of malicious pleasure in irritating the monks. As if for the sake of a joke, he cited Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom ...

to prove that the believed founder of the monastery of St. Denis, Dionysius the Areopagite

Dionysius the Areopagite (; grc-gre, Διονύσιος ὁ Ἀρεοπαγίτης ''Dionysios ho Areopagitēs'') was an Athenian judge at the Areopagus Court in Athens, who lived in the first century. A convert to Christianity, he is venerat ...

had been Bishop of Corinth

The Metropolis of Corinth, Sicyon, Zemenon, Tarsos and Polyphengos ( el, Ιερά Μητρόπολις Κορίνθου, Σικυώνος, Ζεμενού, Ταρσού και Πολυφέγγους) is a metropolitan see of the Church of Greece in ...

, while the other monks relied upon the statement of the Abbot Hilduin

Hilduin (c. 785 – c. 855) was Bishop of Paris, chaplain to Louis I, reforming Abbot of the Abbey of Saint-Denis, and author. He was one of the leading scholars and administrators of the Carolingian Empire.

Background

Hilduin was from a pr ...

that he had been Bishop of Athens

The Archbishopric of Athens ( el, Ιερά Αρχιεπισκοπή Αθηνών) is a Greek Orthodox archiepiscopal see based in the city of Athens, Greece. It is the senior see of Greece, and the seat of the autocephalous Church of Greece. Its ...

. When this historical heresy led to the inevitable persecution, Abelard wrote a letter to the Abbot Adam in which he preferred to the authority of Bede that of Eusebius of Caesarea

Eusebius of Caesarea (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος ; 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus (from the grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος τοῦ Παμφίλου), was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Chris ...

's '' Historia Ecclesiastica'' and St. Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian priest, confessor, theologian, and historian; he is co ...

, according to whom Dionysius, Bishop of Corinth

Dionysius of Corinth, also known as Saint Dionysius, was the bishop of Corinth in about the year 171. His feast day is commemorated on April 8.

Date

The date is established by the fact that he wrote to Pope Soter. Eusebius in his ''Chronicle'' ...

, was distinct from Dionysius the Areopagite, bishop of Athens and founder of the abbey; although, in deference to Bede, he suggested that the Areopagite might also have been bishop of Corinth. Adam accused him of insulting both the monastery and the Kingdom of France (which had Denis as its patron saint); life in the monastery grew intolerable for Abelard, and he was finally allowed to leave.

Abelard initially lodged at St. Ayoul of Provins, where the prior was a friend. Then, after the death of Abbot Adam in March 1122, Abelard was able to gain permission from the new abbot, Suger

Suger (; la, Sugerius; 1081 – 13 January 1151) was a French abbot, statesman, and historian. He once lived at the court of Pope Calixtus II in Maguelonne, France. He later became abbot of St-Denis, and became a close confidant to King Lo ...

, to live "in whatever solitary place he wished". In a deserted place near Nogent-sur-Seine

Nogent-sur-Seine () is a commune in the Aube department in north-central France. The headquarters of The Soufflet Group is located here, as is the Musée Camille Claudel. The large Nogent Nuclear Power Plant is located here.

Population

Pe ...

in Champagne

Champagne (, ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, that demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, ...

, he built a cabin of stubble and reeds, created a simple oratory dedicated to the Trinity, and became a hermit

A hermit, also known as an eremite ( adjectival form: hermitic or eremitic) or solitary, is a person who lives in seclusion. Eremitism plays a role in a variety of religions.

Description

In Christianity, the term was originally applied to a C ...

. When his retreat became known, students flocked from Paris, and covered the wilderness around him with their tents and huts. He began to teach again there. The oratory was rebuilt in wood and stone and rededicated as the Oratory of the Paraclete.

Abelard remained at the Paraclete for about five years. His combination of the teaching of secular arts with his profession as a monk was heavily criticized by other men of religion, and Abelard contemplated flight outside Christendom altogether. Abelard therefore decided to leave and find another refuge, accepting sometime between 1126 and 1128 an invitation to preside over the Abbey of

Abelard remained at the Paraclete for about five years. His combination of the teaching of secular arts with his profession as a monk was heavily criticized by other men of religion, and Abelard contemplated flight outside Christendom altogether. Abelard therefore decided to leave and find another refuge, accepting sometime between 1126 and 1128 an invitation to preside over the Abbey of Saint-Gildas-de-Rhuys

Saint-Gildas-de-Rhuys () is a commune in the Morbihan department of Brittany in north-western France. Inhabitants of Saint-Gildas-de-Rhuys are called in French ''Gildasiens''.

Its French name refers to Saint Gildas, who founded the abbey of Sai ...

on the far-off shore of Lower Brittany. The region was inhospitable, the domain a prey to outlaws, the house itself savage and disorderly. There, too, his relations with the community deteriorated. Lack of success at St. Gildas made Abelard decide to take up public teaching again (although he remained for a few more years, officially, Abbot of St. Gildas). It is not entirely certain what he then did, but given that

Lack of success at St. Gildas made Abelard decide to take up public teaching again (although he remained for a few more years, officially, Abbot of St. Gildas). It is not entirely certain what he then did, but given that John of Salisbury

John of Salisbury (late 1110s – 25 October 1180), who described himself as Johannes Parvus ("John the Little"), was an English author, philosopher, educationalist, diplomat and bishop of Chartres.

Early life and education

Born at Salisbury, E ...

heard Abelard lecture on dialectic in 1136, it is presumed that he returned to Paris and resumed teaching on the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève

The Montagne Sainte-Geneviève is a hill overlooking the left bank of the Seine in the 5th arrondissement of Paris. It was known to the ancient Romans as .Hilaire Belloc, '' Paris (Methuen & Company, 1900)'' Retrieved June 14, 2016 Atop the Mon ...

. His lectures were dominated by logic, at least until 1136, when he produced further drafts of his ''Theologia'' in which he analyzed the sources of belief in the Trinity and praised the pagan philosophers of classical antiquity for their virtues and for their discovery by the use of reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, lang ...

of many fundamental aspects of Christian revelation.

In 1128, Abbot Suger claimed that the convent at Argenteuil, where Héloïse was prioress, belonged to his abbey of St Denis. In 1129 he gained possession and he made no provision for the nuns. When Abelard heard, he transferred Paraclete and its lands to Héloïse and her remaining nuns, making her abbess. He provided the new community with a rule and with a justification of the nun's way of life; in this he emphasized the virtue of literary study. He also provided books of hymns he had composed, and in the early 1130s he and Héloïse composed a collection of their own love letters and religious correspondence containing, amongst other notable pieces, Abelard's most famous letter containing his autobiography, ''Historia Calamitatum

''Historia Calamitatum'' (known in English as ''The Story of My Misfortunes'' or ''The History of My Calamities''), also known as ''Abaelardi ad Amicum Suum Consolatoria,'' is an autobiographical work in Latin by Peter Abelard (1079–1142), a med ...

'' (''The History of My Calamities''). This moved Héloïse to write her first Letter; the first being followed by the two other Letters, in which she finally accepted the part of resignation, which, now as a brother to a sister, Abelard commended to her. Sometime before 1140, Abelard published his masterpiece, ''Ethica'' or '' Scito te ipsum'' (Know Thyself), where he analyzes the idea of sin and that actions are not what a man will be judged for but intentions. During this period, he also wrote '' Dialogus inter Philosophum, Judaeum et Christianum'' (Dialogue between a Philosopher, a Jew, and a Christian), and also '' Expositio in Epistolam ad Romanos'', a commentary on St. Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

's epistle to the Romans, where he expands on the meaning of Christ's life.

Conflicts with Bernard of Clairvaux

After 1136, it is not clear whether Abelard had stopped teaching, or whether he perhaps continued with all except his lectures on logic until as late as 1141. Whatever the exact timing, a process was instigated by William of St-Thierry, who discovered what he considered to be heresies in some of Abelard's teaching. In spring 1140 he wrote to theBishop of Chartres

The oldest known list of bishops of Chartres is found in an 11th-century manuscript of Trinity Abbey, Vendôme. It includes 57 names from Adventus (Saint Aventin) to Aguiertus (Agobert) who died in 1060. The most well-known list is included in the ...

and to Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, O. Cist. ( la, Bernardus Claraevallensis; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templars, and a major leader in the reformation of the Benedictine Order through t ...

, denouncing them. Another, less distinguished, theologian, Thomas of Morigny, also produced at the same time a list of Abelard's supposed heresies, perhaps at Bernard's instigation. Bernard's complaint mainly was that Abelard had applied logic where it is not applicable, and that is illogical.

Amid pressure from Bernard, Abelard challenged Bernard either to withdraw his accusations, or to make them publicly at the important church council at Sens planned for 2 June 1141. In so doing, Abelard put himself into the position of the wronged party and forced Bernard to defend himself from the accusation of slander. Bernard avoided this trap, however: on the eve of the council, he called a private meeting of the assembled bishops and persuaded them to condemn, one by one, each of the heretical propositions he attributed to Abelard. When Abelard appeared at the council the next day, he was presented with a list of condemned propositions imputed to him..

Unable to answer to these propositions, Abelard left the assembly, appealed to the Pope, and set off for Rome, hoping that the Pope would be more supportive. However, this hope was unfounded. On 16 July 1141, Pope Innocent II

Pope Innocent II ( la, Innocentius II; died 24 September 1143), born Gregorio Papareschi, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 February 1130 to his death in 1143. His election as pope was controversial and the fi ...

issued a bull excommunicating

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

Abelard and his followers and imposing perpetual silence on him, and in a second document, he ordered Abelard to be confined in a monastery and his books to be burned. Abelard was saved from this sentence, however, by Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny

Cluny () is a commune in the eastern French department of Saône-et-Loire, in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is northwest of Mâcon.

The town grew up around the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded by Duke William I of Aquitaine in ...

. Abelard had stopped there, on his way to Rome, before the papal condemnation had reached France. Peter persuaded Abelard, already old, to give up his journey and stay at the monastery. Peter managed to arrange a reconciliation with Bernard, to have the sentence of excommunication lifted, and to persuade Innocent that it was enough if Abelard remained under the aegis of Cluny.

Abelard spent his final months at the priory of St. Marcel, near Chalon-sur-Saône

Chalon-sur-Saône (, literally ''Chalon on Saône'') is a city in the Saône-et-Loire department in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in eastern France.

It is a sub-prefecture of the department. It is the largest city in the department; h ...

, before he died on 21 April 1142. He is said to have uttered the last words "I don't know", before expiring. He died from a fever while suffering from a skin disorder, possibly mange

Mange is a type of skin disease caused by parasitic mites. Because various species of mites also infect plants, birds and reptiles, the term "mange", or colloquially "the mange", suggesting poor condition of the skin and fur due to the infectio ...

or scurvy

Scurvy is a deficiency disease, disease resulting from a lack of vitamin C (ascorbic acid). Early symptoms of deficiency include weakness, feeling tired and sore arms and legs. Without treatment, anemia, decreased red blood cells, gum disease, ch ...

. Heloise and Peter of Cluny arranged with the Pope, after Abelard's death, to clear his name of heresy charges.

Disputed resting place/lovers' pilgrimage

Abelard was first buried at St. Marcel, but his remains were soon carried off secretly to the Paraclete, and given over to the loving care of Héloïse, who in time came herself to rest beside them in 1163.

The bones of the pair were moved more than once afterwards, but they were preserved even through the vicissitudes of the

Abelard was first buried at St. Marcel, but his remains were soon carried off secretly to the Paraclete, and given over to the loving care of Héloïse, who in time came herself to rest beside them in 1163.

The bones of the pair were moved more than once afterwards, but they were preserved even through the vicissitudes of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, and now are presumed to lie in the well-known tomb in Père Lachaise Cemetery

Père Lachaise Cemetery (french: Cimetière du Père-Lachaise ; formerly , "East Cemetery") is the largest cemetery in Paris, France (). With more than 3.5 million visitors annually, it is the most visited necropolis in the world. Notable figure ...

in eastern Paris. The transfer of their remains there in 1817 is considered to have considerably contributed to the popularity of that cemetery, at the time still far outside the built-up area of Paris. By tradition, lovers or lovelorn singles leave letters at the crypt, in tribute to the couple or in hope of finding true love.

This second burial remains disputed. The Oratory of the Paraclete claims Abelard and Héloïse are buried there and that what exists in Père-Lachaise is merely a monument, or cenotaph

A cenotaph is an empty tomb or a monument erected in honour of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been reinterred elsewhere. Although the vast majority of cenot ...

. According to Père-Lachaise, the remains of both lovers were transferred from the Oratory in the early 19th century and reburied in the famous crypt on their grounds. Others believe that while Abelard is buried in the tomb at Père-Lachaise, Heloïse's remains are elsewhere.

Health issues

Abelard suffered at least two nervous collapses, the first around 1104–5, cited as due to the stresses of too much study. In his words: "Not long afterward, though, my health broke down under the strain of too much study and I had to return home to Brittany. I was away from France for several years, bitterly missed..." His second documented collapse took place in 1141 at the Council of Sens, where he was accused of heresy and was unable to speak in reply. In the words of Geoffrey of Auxerre: his "memory became very confused, his reason blacked out and his interior sense forsook him." Medieval understanding of mental health precedes development of modern psychiatric diagnosis. No diagnosis besides "ill health" was applied to Abelard at the time. His tendencies towards self-acclaim,grandiosity

In the field of psychology, the term grandiosity refers to an unrealistic sense of superiority, characterized by a sustained view of one's self as better than others, which is expressed by disdainfully criticising them (contempt), overinflating ...

, paranoia

Paranoia is an instinct or thought process that is believed to be heavily influenced by anxiety or fear, often to the point of delusion and irrationality. Paranoid thinking typically includes persecutory beliefs, or beliefs of conspiracy c ...

and shame

Shame is an unpleasant self-conscious emotion often associated with negative self-evaluation; motivation to quit; and feelings of pain, exposure, distrust, powerlessness, and worthlessness.

Definition

Shame is a discrete, basic emotion, d ...

are suggestive of possible latent narcissism

Narcissism is a self-centered personality style characterized as having an excessive interest in one's physical appearance or image and an excessive preoccupation with one's own needs, often at the expense of others.

Narcissism exists on a co ...

(despite his great talents and fame), or – recently conjectured – in keeping with his breakdowns, overwork, loquaciousness and belligerence – mood-related mental health issues such as mania related to bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder, previously known as manic depression, is a mental disorder characterized by periods of Depression (mood), depression and periods of abnormally elevated Mood (psychology), mood that last from days to weeks each. If the elevat ...

.

At the time, some of these characteristics were attributed disparagingly to his Breton heritage, his difficult "indomitable" personality and overwork.

Philosophical thought, and achievements

Philosophy

Abelard is considered one of the founders of the secular university and pre-Renaissance secular philosophical thought.

Abelard argued for

Abelard is considered one of the founders of the secular university and pre-Renaissance secular philosophical thought.

Abelard argued for conceptualism

In metaphysics, conceptualism is a theory that explains universality of particulars as conceptualized frameworks situated within the thinking mind. Intermediate between nominalism and realism, the conceptualist view approaches the metaphysical co ...

in the theory of universals

In metaphysics, a universal is what particular things have in common, namely characteristics or qualities. In other words, universals are repeatable or recurrent entities that can be instantiated or exemplified by many particular things. For exa ...

. (A universal is a quality or property which every individual member of a class of things must possess if the same word is to apply to all the things in that class. Blueness, for example, is an universal property

In mathematics, more specifically in category theory, a universal property is a property that characterizes up to an isomorphism the result of some constructions. Thus, universal properties can be used for defining some objects independently fr ...

possessed by all blue objects.) According to Abelard scholar David Luscombe

David Edward Luscombe (22 July 1938 – 30 August 2021) was a British medievalist. He was professor emeritus of medieval history at the University of Sheffield. He was elected a fellow of the British Academy in 1986. He was also a fellow of the R ...

, "Abelard logically elaborated an independent philosophy of language

In analytic philosophy, philosophy of language investigates the nature of language and the relations between language, language users, and the world. Investigations may include inquiry into the nature of Meaning (philosophy of language), meanin ...

... n whichhe stressed that language itself is not able to demonstrate the truth of things (res) that lie in the domain of physics."

Writing with the influence of his wife Heloise, he stressed that subjective intention determines the moral value of human action. With Heloise, he is the first significant philosopher of the Middle Ages to push for intentionalist ethics before Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, Dominican Order, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino, Italy, Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest who was an influential List of Catholic philo ...

.

He helped establish the philosophical authority of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

, which became firmly established in the half-century after his death. It was at this time that Aristotle's ''Organon

The ''Organon'' ( grc, Ὄργανον, meaning "instrument, tool, organ") is the standard collection of Aristotle's six works on logical analysis and dialectic. The name ''Organon'' was given by Aristotle's followers, the Peripatetics.

The six ...

'' first became available, and gradually all of Aristotle's other surviving works. Before this, the works of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

formed the basis of support for philosophical realism

Philosophical realism is usually not treated as a position of its own but as a stance towards other subject matters. Realism about a certain kind of thing (like numbers or morality) is the thesis that this kind of thing has ''mind-independent e ...

.

Theology

Abelard is considered one of the greatest twelfth-century Catholic philosophers, arguing that God and the universe can and should be known via logic as well as via the emotions. He coined the term "theology" for the religious branch of philosophical tradition. He should not be read as a heretic, as his charges of heresy were dropped and rescinded by the Church after his death, but rather as a cutting-edge philosopher who pushed theology and philosophy to their limits. He is described as "the keenest thinker and boldest theologian of the 12th century"Chambers Biographical Dictionary

''Chambers Biographical Dictionary'' provides concise descriptions of over 18,000 notable figures from Britain and the rest of the world. It was first published in 1897.

The publishers, Chambers Harrap, who were formerly based in Edinburgh, clai ...

, , p. 3; . and as the greatest logician of the Middle Ages. "His genius was evident in all he did"; as the first to use 'theology' in its modern sense, he championed "reason in matters of faith", and "seemed larger than life to his contemporaries: his quick wit, sharp tongue, perfect memory, and boundless arrogance made him unbeatable in debate"--"the force of his personality impressed itself vividly on all with whom he came into contact."

Regarding the unbaptized

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost i ...

who die in infancy

An infant or baby is the very young offspring of human beings. ''Infant'' (from the Latin word ''infans'', meaning 'unable to speak' or 'speechless') is a formal or specialised synonym for the common term ''baby''. The terms may also be used to ...

, Abelard — in ''Commentaria in Epistolam Pauli ad Romanos'' — emphasized the goodness of God and interpreted Augustine

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Afr ...

's "mildest punishment" as the pain of loss at being denied the beatific vision (''carentia visionis Dei''), without hope of obtaining it, but with no additional punishments. His thought contributed to the forming of Limbo of Infants theory in the 12th–13th centuries.

Psychology

Abelard was concerned with the concept of intent and inner life, developing an elementary theory of cognition in his ''Tractabus De Intellectibus'', and later developing the concept that human beings "speak to God with their thoughts". He was one of the developers of theinsanity defense

The insanity defense, also known as the mental disorder defense, is an affirmative defense by excuse in a criminal case, arguing that the defendant is not responsible for their actions due to an episodic psychiatric disease at the time of the ...

, writing in ''Scito te ipsum'', "Of this in small children and of course insane people are untouched...lack ngreason....nothing is counted as sin for them". He spearheaded the idea that mental illness was a natural condition and "debunked the idea that the devil caused insanity", a point of view which Thomas F. Graham argues Abelard was unable to separate himself from objectively to argue more subtly "because of his own mental health."

Law

Abelard stressed that subjective intention determines the moral value of human action and therefore that the legal consequence of an action is related to the person that commits it and not merely to the action. With this doctrine, Abelard created in the Middle Ages the idea of the individual subject central to modern law. This gave to School of Notre-Dame de Paris (later the University of Paris) a recognition for its expertise in the area of Law, even before thefaculty of law

A faculty is a division within a university or college comprising one subject area or a group of related subject areas, possibly also delimited by level (e.g. undergraduate). In American usage such divisions are generally referred to as colleges ...

existed and the school even recognized as an "universitas" and even if Abelard was a logician and a theologian.

The letters of Abelard and Héloïse

The story of Abelard and Héloïse has proved immensely popular in modern European culture. This story is known almost entirely from a few sources: first, the ''Historia Calamitatum; ''secondly, the seven letters between Abelard and Héloïse which survive (three written by Abelard, and four by Héloïse), and always follow the ''Historia Calamitatum'' in the manuscript tradition; thirdly, four letters between Peter the Venerable and Héloïse (three by Peter, one by Héloïse). They are, in modern times, the best known and most widely translated parts of Abelard's work.

It is unclear quite how the letters of Abelard and Héloïse came to be preserved. There are brief and factual references to their relationship by 12th-century writers including William Godel and

The story of Abelard and Héloïse has proved immensely popular in modern European culture. This story is known almost entirely from a few sources: first, the ''Historia Calamitatum; ''secondly, the seven letters between Abelard and Héloïse which survive (three written by Abelard, and four by Héloïse), and always follow the ''Historia Calamitatum'' in the manuscript tradition; thirdly, four letters between Peter the Venerable and Héloïse (three by Peter, one by Héloïse). They are, in modern times, the best known and most widely translated parts of Abelard's work.

It is unclear quite how the letters of Abelard and Héloïse came to be preserved. There are brief and factual references to their relationship by 12th-century writers including William Godel and Walter Map

Walter Map ( la, Gualterius Mappus; 1130 – 1210) was a medieval writer. He wrote '' De nugis curialium'', which takes the form of a series of anecdotes of people and places, offering insights on the history of his time.

Map was a court ...

. While the letters were most likely exchanged by horseman in a public (open letter) fashion readable by others at stops along the way (and thus explaining Heloise's interception of the Historia), it seems unlikely that the letters were widely known outside of their original travel range during the period. Rather, the earliest manuscripts of the letters are dated to the late 13th century. It therefore seems likely that the letters sent between Abelard and Héloïse were kept by Héloïse at the Paraclete along with the 'Letters of Direction', and that more than a century after her death they were brought to Paris and copied.

Shortly after the deaths of Abelard and Heloise, Chrétien de Troyes

Chrétien de Troyes (Modern ; fro, Crestien de Troies ; 1160–1191) was a French poet and trouvère known for his writing on Arthurian subjects, and for first writing of Lancelot, Percival and the Holy Grail. Chrétien's works, including ...

appears influenced by Heloise's letters and Abelard's castration in his depiction of the fisher king in his grail

The Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) was an American lunar science mission in NASA's Discovery Program which used high-quality gravitational field mapping of the Moon to determine its interior structure. The two small spacecraf ...

tales. In the fourteenth century, the story of their love affair was summarised by Jean de Meun

Jean de Meun (or de Meung, ) () was a French author best known for his continuation of the '' Roman de la Rose''.

Life

He was born Jean Clopinel or Jean Chopinel at Meung-sur-Loire. Tradition asserts that he studied at the University of Paris. He ...

in the '' Le Roman de la Rose''.

Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

makes a brief reference in the Wife of Bath's Prologue (lines 677–8) and may base his character of the wife partially on Heloise. Petrarch

Francesco Petrarca (; 20 July 1304 – 18/19 July 1374), commonly anglicized as Petrarch (), was a scholar and poet of early Renaissance Italy, and one of the earliest humanists.

Petrarch's rediscovery of Cicero's letters is often credited ...

owned an early 14th-century manuscript of the couple's letters (and wrote detailed approving notes in the margins).

The first Latin publication of the letters was in Paris in 1616, simultaneously in two editions. These editions gave rise to numerous translations of the letters into European languages – and consequent 18th- and 19th-century interest in the story of the medieval lovers. In the 18th century, the couple were revered as tragic lovers, who endured adversity in life but were united in death. With this reputation, they were the only individuals from the pre-Revolutionary period whose remains were given a place of honour at the newly founded cemetery of Père Lachaise

A name suffix, in the Western English-language naming tradition, follows a person's full name and provides additional information about the person. Post-nominal letters indicate that the individual holds a position, educational degree, accredit ...

in Paris. At this time, they were effectively revered as romantic saints; for some, they were forerunners of modernity, at odds with the ecclesiastical and monastic structures of their day and to be celebrated more for rejecting the traditions of the past than for any particular intellectual achievement.

The ''Historia'' was first published in 1841 by John Caspar Orelli of Turici. Then, in 1849, Victor Cousin

Victor Cousin (; 28 November 179214 January 1867) was a French philosopher. He was the founder of " eclecticism", a briefly influential school of French philosophy that combined elements of German idealism and Scottish Common Sense Realism. ...

published ''Petri Abaelardi opera'', in part based on the two Paris editions of 1616 but also based on the reading of four manuscripts; this became the standard edition of the letters. Soon after, in 1855, Migne printed an expanded version of the 1616 edition under the title ''Opera Petri Abaelardi'', without the name of Héloïse on the title page.

Critical editions of the ''Historia Calamitatum'' and the letters were subsequently published in the 1950s and 1960s. The most well-established documents, and correspondingly those whose authenticity has been disputed the longest, are the series of letters that begin with the Historia Calamitatum (counted as letter 1) and encompass four "personal letters" (numbered 2–5) and "letters of direction" (numbers 6–8).

Most scholars today accept these works as having been written by Héloïse and Abelard themselves. John Benton is the most prominent modern skeptic of these documents. Etienne Gilson, Peter Dronke, Constant Mews, and Mary Ellen Waithe maintain the mainstream view that the letters are genuine, arguing that the skeptical viewpoint is fueled in large part by its advocates' pre-conceived notions.

Lost love letters

More recently, it has been argued that an anonymous series of letters, the ''Epistolae Duorum Amantium'', were in fact written by Héloïse and Abelard during their initial romance (and, thus, before the later and more broadly known series of letters). This argument has been advanced by Constant J. Mews, based on earlier work by Ewad Könsgen. If genuine, these letters represent a significant expansion to the corpus of surviving writing by Héloïse, and thus open several new directions for further scholarship. However, because the attribution "is of necessity based on circumstantial rather than on absolute evidence," it is not accepted by all scholars.Contemporary theology

Novelist and Abelard scholar George Moore referred to Abelard as the "firstprotestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

" prior to Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

. While Abelard conflicted with the Church to point of (later cleared) heresy charges, he never denied his Catholic faith.

Comments from Pope Benedict XVI

During his general audience on 4 November 2009,Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI ( la, Benedictus XVI; it, Benedetto XVI; german: link=no, Benedikt XVI.; born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, , on 16 April 1927) is a retired prelate of the Catholic church who served as the head of the Church and the sovereig ...

talked about Saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Catholic, Eastern Or ...

Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux, O. Cist. ( la, Bernardus Claraevallensis; 109020 August 1153), venerated as Saint Bernard, was an abbot, mystic, co-founder of the Knights Templars, and a major leader in the reformation of the Benedictine Order through t ...

and Peter Abelard to illustrate differences in the monastic

Monasticism (from Ancient Greek , , from , , 'alone'), also referred to as monachism, or monkhood, is a religion, religious way of life in which one renounces world (theology), worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual work. Monastic ...

and scholastic approaches to theology in the 12th century. The Pope recalled that theology is the search for a rational understanding (if possible) of the mysteries of Christian revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Background

Inspiration – such as that bestowed by God on the ...

, which is believed through faith

Faith, derived from Latin ''fides'' and Old French ''feid'', is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or In the context of religion, one can define faith as "belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

Religious people ofte ...

— faith that seeks intelligibility (''fides quaerens intellectum''). But St. Bernard, a representative of monastic theology, emphasized "faith" whereas Abelard, who is a scholastic, stressed "understanding through reason".

For Bernard of Clairvaux, faith is based on the testimony of Scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual pra ...

and on the teaching of the Fathers of the Church

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

. Thus, Bernard found it difficult to agree with Abelard and, in a more general way, with those who would subject the truths of faith to the critical examination of reason — an examination which, in his opinion, posed a grave danger: intellectualism

Intellectualism is the mental perspective that emphasizes the use, the development, and the exercise of the intellect; and also identifies the life of the mind of the intellectual person. (Definition) In the field of philosophy, the term ''inte ...

, the relativizing of truth, and the questioning of the truths of faith themselves. Theology for Bernard could be nourished only in contemplative prayer

Christian mysticism is the tradition of mystical practices and mystical theology within Christianity which "concerns the preparation f the personfor, the consciousness of, and the effect of ..a direct and transformative presence of God" ...

, by the affective union of the heart and mind with God, with only one purpose: to promote the living, intimate experience of God; an aid to loving God ever more and ever better.

According to Pope Benedict XVI, an excessive use of philosophy rendered Abelard's doctrine

Doctrine (from la, doctrina, meaning "teaching, instruction") is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the essence of teachings in a given branch of knowledge or in a belief syste ...

of the Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God th ...

fragile and, thus, his idea of God. In the field of morals, his teaching was vague, as he insisted on considering the intention of the subject as the only basis for describing the goodness or evil of moral acts, thereby ignoring the objective meaning and moral value of the acts, resulting in a dangerous subjectivism

Subjectivism is the doctrine that "our own mental activity is the only unquestionable fact of our experience", instead of shared or communal, and that there is no external or objective truth.

The success of this position is historically attribute ...

. But the Pope recognized the great achievements of Abelard, who made a decisive contribution to the development of scholastic theology, which eventually expressed itself in a more mature and fruitful way during the following century. And some of Abelard's insights should not be underestimated, for example, his affirmation that non-Christian religious traditions already contain some form of preparation for welcoming Christ.