Axons on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An axon (from Greek ἄξων ''áxōn'', axis), or nerve fiber (or nerve fibre: see

Axons are the primary transmission lines of the

Axons are the primary transmission lines of the

The

The

In the nervous system, axons may be

In the nervous system, axons may be

Growing axons move through their environment via the

Growing axons move through their environment via the

,

spelling differences

Despite the various English dialects spoken from country to country and within different regions of the same country, there are only slight regional variations in English orthography, the two most notable variations being British and American ...

), is a long, slender projection of a nerve cell, or neuron

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and placozoa. N ...

, in vertebrates, that typically conducts electrical impulses known as action potential

An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific cell location rapidly rises and falls. This depolarization then causes adjacent locations to similarly depolarize. Action potentials occur in several types of animal cells, ...

s away from the nerve cell body. The function of the axon is to transmit information to different neurons, muscles, and glands. In certain sensory neuron

Sensory neurons, also known as afferent neurons, are neurons in the nervous system, that convert a specific type of stimulus, via their receptors, into action potentials or graded potentials. This process is called sensory transduction. The cell ...

s (pseudounipolar neuron

A pseudounipolar neuron is a type of neuron which has one extension from its cell body. This type of neuron contains an axon that has split into two branches. A single process arises from the cell body and then divides into an axon and a dendrite ...

s), such as those for touch and warmth, the axons are called afferent nerve fiber

Afferent nerve fibers are the axons (nerve fibers) carried by a sensory nerve that relay sensory information from sensory receptors to regions of the brain. Afferent projections ''arrive'' at a particular brain region. Efferent nerve fibers a ...

s and the electrical impulse travels along these from the periphery

Periphery or peripheral may refer to:

Music

*Periphery (band), American progressive metal band

* ''Periphery'' (album), released in 2010 by Periphery

* "Periphery", a song from Fiona Apple's album '' The Idler Wheel...''

Gaming and entertainm ...

to the cell body and from the cell body to the spinal cord along another branch of the same axon. Axon dysfunction can be the cause of many inherited and acquired neurological disorder

A neurological disorder is any disorder of the nervous system. Structural, biochemical or electrical abnormalities in the brain, spinal cord or other nerves can result in a range of symptoms. Examples of symptoms include paralysis, muscle weakn ...

s that affect both the peripheral

A peripheral or peripheral device is an auxiliary device used to put information into and get information out of a computer. The term ''peripheral device'' refers to all hardware components that are attached to a computer and are controlled by the ...

and central neurons. Nerve fibers are classed into three typesgroup A nerve fiber

Group A nerve fibers are one of the three classes of nerve fiber as ''generally classified'' by Erlanger and Gasser. The other two classes are the group B nerve fibers, and the group C nerve fibers. Group A are heavily myelinated, group B ar ...

s, group B nerve fiber

Group B nerve fibers are axons, which are moderately myelinated, which means less myelinated than group A nerve fibers, and more myelinated than group C nerve fibers. Their conduction velocity is 3 to 14 m/s. They are usually general visceral affe ...

s, and group C nerve fiber

Group C nerve fibers are one of three classes of nerve fiber in the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS). The C group fibers are unmyelinated and have a small diameter and low conduction velocity, whereas Groups A ...

s. Groups A and B are myelin

Myelin is a lipid-rich material that surrounds nerve cell axons (the nervous system's "wires") to insulate them and increase the rate at which electrical impulses (called action potentials) are passed along the axon. The myelinated axon can be ...

ated, and group C are unmyelinated. These groups include both sensory fibers and motor fibers. Another classification groups only the sensory fibers as Type I, Type II, Type III, and Type IV.

An axon is one of two types of cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

ic protrusions from the cell body of a neuron; the other type is a dendrite

Dendrites (from Greek δένδρον ''déndron'', "tree"), also dendrons, are branched protoplasmic extensions of a nerve cell that propagate the electrochemical stimulation received from other neural cells to the cell body, or soma, of the n ...

. Axons are distinguished from dendrites by several features, including shape (dendrites often taper while axons usually maintain a constant radius), length (dendrites are restricted to a small region around the cell body while axons can be much longer), and function (dendrites receive signals whereas axons transmit them). Some types of neurons have no axon and transmit signals from their dendrites. In some species, axons can emanate from dendrites known as axon-carrying dendrites. No neuron ever has more than one axon; however in invertebrates such as insects or leeches the axon sometimes consists of several regions that function more or less independently of each other.

Axons are covered by a membrane known as an axolemma

In neuroscience, the axolemma (, and 'axo-' from axon) is the cell membrane of an axon, the branch of a neuron through which signals (action potentials) are transmitted. The axolemma is a three-layered, bilipid membrane. Under standard electron m ...

; the cytoplasm of an axon is called axoplasm

Axoplasm is the cytoplasm within the axon of a neuron (nerve cell). For some neuronal types this can be more than 99% of the total cytoplasm.

Axoplasm has a different composition of organelles and other materials than that found in the neuron's c ...

. Most axons branch, in some cases very profusely. The end branches of an axon are called telodendria

An axon (from Greek ἄξων ''áxōn'', axis), or nerve fiber (or nerve fibre: see spelling differences), is a long, slender projection of a nerve cell, or neuron, in vertebrates, that typically conducts electrical impulses known as action po ...

. The swollen end of a telodendron is known as the axon terminal

Axon terminals (also called synaptic boutons, terminal boutons, or end-feet) are distal terminations of the telodendria (branches) of an axon. An axon, also called a nerve fiber, is a long, slender projection of a nerve cell, or neuron, that condu ...

which joins the dendron or cell body of another neuron forming a synaptic connection. Axons make contact with other cellsusually other neurons but sometimes muscle or gland cellsat junctions called synapses. In some circumstances, the axon of one neuron may form a synapse with the dendrites of the same neuron, resulting in an autapse An autapse is a chemical or electrical synapse from a neuron onto itself. It can also be described as a synapse formed by the axon of a neuron on its own dendrites, ''in vivo'' or ''in vitro''.

History

The term "autapse" was first coined in 1972 ...

. At a synapse, the membrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. B ...

of the axon closely adjoins the membrane of the target cell, and special molecular structures serve to transmit electrical or electrochemical signals across the gap. Some synaptic junctions appear along the length of an axon as it extends; these are called ''en passant'' ("in passing") synapses and can be in the hundreds or even the thousands along one axon. Other synapses appear as terminals at the ends of axonal branches.

A single axon, with all its branches taken together, can innervate

A nerve is an enclosed, cable-like bundle of nerve fibers (called axons) in the peripheral nervous system.

A nerve transmits electrical impulses. It is the basic unit of the peripheral nervous system. A nerve provides a common pathway for the e ...

multiple parts of the brain and generate thousands of synaptic terminals. A bundle of axons make a nerve tract

A nerve tract is a bundle of nerve fibers (axons) connecting nuclei of the central nervous system. In the peripheral nervous system this is known as a nerve, and has associated connective tissue. The main nerve tracts in the central nervous syste ...

in the central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain and spinal cord. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity of all par ...

, and a fascicle

Fascicle or ''fasciculus'' may refer to:

Anatomy and histology

* Muscle fascicle, a bundle of skeletal muscle fibers

* Nerve fascicle, a bundle of axons (nerve fibers)

** Superior longitudinal fasciculus

*** Arcuate fasciculus

** Gracile fas ...

in the peripheral nervous system

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) is one of two components that make up the nervous system of bilateral animals, with the other part being the central nervous system (CNS). The PNS consists of nerves and ganglia, which lie outside the brain ...

. In placental mammals

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguishe ...

the largest white matter

White matter refers to areas of the central nervous system (CNS) that are mainly made up of myelinated axons, also called tracts. Long thought to be passive tissue, white matter affects learning and brain functions, modulating the distribution ...

tract in the brain is the corpus callosum

The corpus callosum (Latin for "tough body"), also callosal commissure, is a wide, thick nerve tract, consisting of a flat bundle of commissural fibers, beneath the cerebral cortex in the brain. The corpus callosum is only found in placental mam ...

, formed of some 200 million axons in the human brain

The human brain is the central organ of the human nervous system, and with the spinal cord makes up the central nervous system. The brain consists of the cerebrum, the brainstem and the cerebellum. It controls most of the activities of the ...

.

Anatomy

nervous system

In biology, the nervous system is the highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its actions and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes th ...

, and as bundles they form nerve

A nerve is an enclosed, cable-like bundle of nerve fibers (called axons) in the peripheral nervous system.

A nerve transmits electrical impulses. It is the basic unit of the peripheral nervous system. A nerve provides a common pathway for the e ...

s. Some axons can extend up to one meter or more while others extend as little as one millimeter. The longest axons in the human body are those of the sciatic nerve

The sciatic nerve, also called the ischiadic nerve, is a large nerve in humans and other vertebrate animals which is the largest branch of the sacral plexus and runs alongside the hip joint and down the lower limb. It is the longest and widest si ...

, which run from the base of the spinal cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue, which extends from the medulla oblongata in the brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone). The backbone encloses the central canal of the spi ...

to the big toe of each foot. The diameter of axons is also variable. Most individual axons are microscopic in diameter (typically about one micrometer Micrometer can mean:

* Micrometer (device), used for accurate measurements by means of a calibrated screw

* American spelling of micrometre

The micrometre ( international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; ...

(µm) across). The largest mammalian axons can reach a diameter of up to 20 µm. The squid giant axon

The squid giant axon is the very large (up to 1.5 mm in diameter; typically around 0.5 mm) axon that controls part of the water jet propulsion system in squid. It was first described by L. W. Williams in 1909, but this discovery was for ...

, which is specialized to conduct signals very rapidly, is close to 1 millimeter in diameter, the size of a small pencil lead. The numbers of axonal telodendria (the branching structures at the end of the axon) can also differ from one nerve fiber to the next. Axons in the central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain and spinal cord. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity of all par ...

(CNS) typically show multiple telodendria, with many synaptic end points. In comparison, the cerebellar granule cell

Cerebellar granule cells form the thick granular layer of the cerebellar cortex and are among the smallest neurons in the brain. (The term granule cell is used for several unrelated types of small neurons in various parts of the brain.) Cereb ...

axon is characterized by a single T-shaped branch node from which two parallel fiber

Parallel is a geometric term of location which may refer to:

Computing

* Parallel algorithm

* Parallel computing

* Parallel metaheuristic

* Parallel (software), a UNIX utility for running programs in parallel

* Parallel Sysplex, a cluster of IBM ...

s extend. Elaborate branching allows for the simultaneous transmission of messages to a large number of target neuron

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and placozoa. N ...

s within a single region of the brain.

There are two types of axons in the nervous system: myelin

Myelin is a lipid-rich material that surrounds nerve cell axons (the nervous system's "wires") to insulate them and increase the rate at which electrical impulses (called action potentials) are passed along the axon. The myelinated axon can be ...

ated and unmyelinated

Myelin is a lipid-rich material that surrounds nerve cell axons (the nervous system's "wires") to insulate them and increase the rate at which electrical impulses (called action potentials) are passed along the axon. The myelinated axon can be l ...

axons. Myelin

Myelin is a lipid-rich material that surrounds nerve cell axons (the nervous system's "wires") to insulate them and increase the rate at which electrical impulses (called action potentials) are passed along the axon. The myelinated axon can be ...

is a layer of a fatty insulating substance, which is formed by two types of glial cells

Glia, also called glial cells (gliocytes) or neuroglia, are non-neuronal cells in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and the peripheral nervous system that do not produce electrical impulses. They maintain homeostasis, form mye ...

: Schwann cell

Schwann cells or neurolemmocytes (named after German physiologist Theodor Schwann) are the principal glia of the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Glial cells function to support neurons and in the PNS, also include satellite cells, olfactory ensh ...

s and oligodendrocyte

Oligodendrocytes (), or oligodendroglia, are a type of neuroglia whose main functions are to provide support and insulation to axons in the central nervous system of jawed vertebrates, equivalent to the function performed by Schwann cells in the ...

s. In the peripheral nervous system

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) is one of two components that make up the nervous system of bilateral animals, with the other part being the central nervous system (CNS). The PNS consists of nerves and ganglia, which lie outside the brain ...

Schwann cells form the myelin sheath of a myelinated axon. Oligodendrocytes form the insulating myelin in the CNS. Along myelinated nerve fibers, gaps in the myelin sheath known as nodes of Ranvier

In neuroscience and anatomy, nodes of Ranvier ( ), also known as myelin-sheath gaps, occur along a myelinated axon where the axolemma is exposed to the extracellular space. Nodes of Ranvier are uninsulated and highly enriched in ion channels, al ...

occur at evenly spaced intervals. The myelination enables an especially rapid mode of electrical impulse propagation called saltatory conduction

In neuroscience, saltatory conduction () is the propagation of action potentials along myelinated axons from one node of Ranvier to the next node, increasing the conduction velocity of action potentials. The uninsulated nodes of Ranvier are th ...

.

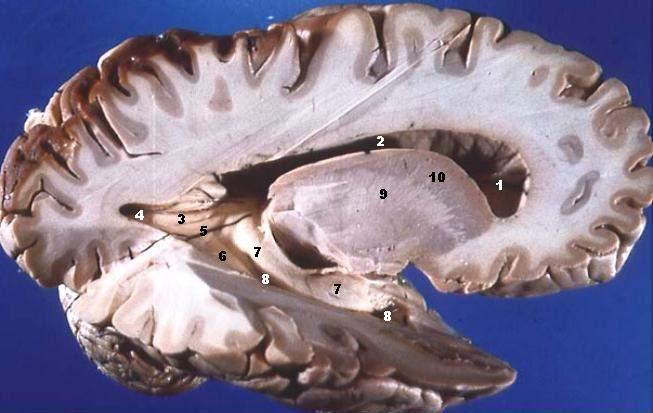

The myelinated axons from the cortical neurons

The cerebral cortex, also known as the cerebral mantle, is the outer layer of neural tissue of the cerebrum of the brain in humans and other mammals. The cerebral cortex mostly consists of the six-layered neocortex, with just 10% consisting of ...

form the bulk of the neural tissue called white matter

White matter refers to areas of the central nervous system (CNS) that are mainly made up of myelinated axons, also called tracts. Long thought to be passive tissue, white matter affects learning and brain functions, modulating the distribution ...

in the brain. The myelin gives the white appearance to the tissue in contrast to the grey matter

Grey matter is a major component of the central nervous system, consisting of neuronal cell bodies, neuropil (dendrites and unmyelinated axons), glial cells (astrocytes and oligodendrocytes), synapses, and capillaries. Grey matter is distingui ...

of the cerebral cortex which contains the neuronal cell bodies. A similar arrangement is seen in the cerebellum

The cerebellum (Latin for "little brain") is a major feature of the hindbrain of all vertebrates. Although usually smaller than the cerebrum, in some animals such as the mormyrid fishes it may be as large as or even larger. In humans, the cerebel ...

. Bundles of myelinated axons make up the nerve tract

A nerve tract is a bundle of nerve fibers (axons) connecting nuclei of the central nervous system. In the peripheral nervous system this is known as a nerve, and has associated connective tissue. The main nerve tracts in the central nervous syste ...

s in the CNS. Where these tracts cross the midline of the brain to connect opposite regions they are called ''commissures''. The largest of these is the corpus callosum

The corpus callosum (Latin for "tough body"), also callosal commissure, is a wide, thick nerve tract, consisting of a flat bundle of commissural fibers, beneath the cerebral cortex in the brain. The corpus callosum is only found in placental mam ...

that connects the two cerebral hemisphere

The vertebrate cerebrum (brain) is formed by two cerebral hemispheres that are separated by a groove, the longitudinal fissure. The brain can thus be described as being divided into left and right cerebral hemispheres. Each of these hemispheres ...

s, and this has around 20 million axons.

The structure of a neuron is seen to consist of two separate functional regions, or compartmentsthe cell body together with the dendrites as one region, and the axonal region as the other.

Axonal region

The axonal region or compartment, includes the axon hillock, the initial segment, the rest of the axon, and the axon telodendria, and axon terminals. It also includes the myelin sheath. TheNissl bodies

Nissl bodies (also called Nissl granules, Nissl substance or tigroid substance) are discrete granular structures in neurons that consist of rough endoplasmic reticulum, a collection of parallel, membrane-bound cisternae studded with ribosomes on t ...

that produce the neuronal proteins are absent in the axonal region. Proteins needed for the growth of the axon, and the removal of waste materials, need a framework for transport. This axonal transport

Axonal transport, also called axoplasmic transport or axoplasmic flow, is a cellular process responsible for movement of mitochondria, lipids, synaptic vesicles, proteins, and other organelles to and from a neuron's cell body, through the cytoplas ...

is provided for in the axoplasm by arrangements of microtubule

Microtubules are polymers of tubulin that form part of the cytoskeleton and provide structure and shape to eukaryotic cells. Microtubules can be as long as 50 micrometres, as wide as 23 to 27 nm and have an inner diameter between 11 an ...

s and intermediate filament

Intermediate filaments (IFs) are cytoskeletal structural components found in the cells of vertebrates, and many invertebrates. Homologues of the IF protein have been noted in an invertebrate, the cephalochordate ''Branchiostoma''.

Intermedia ...

s known as neurofilament

Neurofilaments (NF) are classed as type IV intermediate filaments found in the cytoplasm of neurons. They are protein polymers measuring 10 nm in diameter and many micrometers in length. Together with microtubules (~25 nm) and mi ...

s.

Axon hillock

The

The axon hillock

The axon hillock is a specialized part of the cell body (or soma) of a neuron that connects to the axon. It can be identified using light microscopy from its appearance and location in a neuron and from its sparse distribution of Nissl substance. ...

is the area formed from the cell body of the neuron as it extends to become the axon. It precedes the initial segment. The received action potential

An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific cell location rapidly rises and falls. This depolarization then causes adjacent locations to similarly depolarize. Action potentials occur in several types of animal cells, ...

s that are summed in the neuron are transmitted to the axon hillock for the generation of an action potential from the initial segment.

Axonal initial segment

The axonal initial segment (AIS) is a structurally and functionally separate microdomain of the axon. One function of the initial segment is to separate the main part of an axon from the rest of the neuron; another function is to help initiate action potentials. Both of these functions support neuroncell polarity

Cell polarity refers to spatial differences in shape, structure, and function within a cell. Almost all cell types exhibit some form of polarity, which enables them to carry out specialized functions. Classical examples of polarized cells are desc ...

, in which dendrites (and, in some cases the soma

Soma may refer to:

Businesses and brands

* SOMA (architects), a New York–based firm of architects

* Soma (company), a company that designs eco-friendly water filtration systems

* SOMA Fabrications, a builder of bicycle frames and other bicycle ...

) of a neuron receive input signals at the basal region, and at the apical region the neuron's axon provides output signals.

The axon initial segment is unmyelinated and contains a specialized complex of proteins. It is between approximately 20 and 60 µm in length and functions as the site of action potential initiation. Both the position on the axon and the length of the AIS can change showing a degree of plasticity that can fine-tune the neuronal output. A longer AIS is associated with a greater excitability. Plasticity is also seen in the ability of the AIS to change its distribution and to maintain the activity of neural circuitry at a constant level.

The AIS is highly specialized for the fast conduction of nerve impulses

An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific cell location rapidly rises and falls. This depolarization then causes adjacent locations to similarly depolarize. Action potentials occur in several types of animal cells, ...

. This is achieved by a high concentration of voltage-gated sodium channels

Sodium channels are integral membrane proteins that form ion channels, conducting sodium ions (Na+) through a cell's membrane. They belong to the superfamily of cation channels and can be classified according to the trigger that opens the channel ...

in the initial segment where the action potential is initiated. The ion channels are accompanied by a high number of cell adhesion molecule

Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) are a subset of cell surface proteins that are involved in the binding of cells with other cells or with the extracellular matrix (ECM), in a process called cell adhesion. In essence, CAMs help cells stick to each ...

s and scaffolding proteins that anchor them to the cytoskeleton. Interactions with ankyrin G are important as it is the major organizer in the AIS.

Axonal transport

Theaxoplasm

Axoplasm is the cytoplasm within the axon of a neuron (nerve cell). For some neuronal types this can be more than 99% of the total cytoplasm.

Axoplasm has a different composition of organelles and other materials than that found in the neuron's c ...

is the equivalent of cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

in the cell. Microtubules form in the axoplasm at the axon hillock. They are arranged along the length of the axon, in overlapping sections, and all point in the same directiontowards the axon terminals. This is noted by the positive endings of the microtubules. This overlapping arrangement provides the routes for the transport of different materials from the cell body. Studies on the axoplasm has shown the movement of numerous vesicles of all sizes to be seen along cytoskeletal filamentsthe microtubules, and neurofilament

Neurofilaments (NF) are classed as type IV intermediate filaments found in the cytoplasm of neurons. They are protein polymers measuring 10 nm in diameter and many micrometers in length. Together with microtubules (~25 nm) and mi ...

s, in both directions between the axon and its terminals and the cell body.

Outgoing anterograde transport

Axonal transport, also called axoplasmic transport or axoplasmic flow, is a cellular process responsible for movement of mitochondria, lipids, synaptic vesicles, proteins, and other organelles to and from a neuron's cell body, through the cytopla ...

from the cell body along the axon, carries mitochondria and membrane proteins needed for growth to the axon terminal. Ingoing retrograde transport

Axonal transport, also called axoplasmic transport or axoplasmic flow, is a cellular process responsible for movement of mitochondria, lipids, synaptic vesicles, proteins, and other organelles to and from a neuron's cell body, through the cytoplas ...

carries cell waste materials from the axon terminal to the cell body. Outgoing and ingoing tracks use different sets of motor protein

Motor proteins are a class of molecular motors that can move along the cytoplasm of cells. They convert chemical energy into mechanical work by the hydrolysis of ATP. Flagellar rotation, however, is powered by a proton pump.

Cellular functions ...

s. Outgoing transport is provided by kinesin

A kinesin is a protein belonging to a class of motor proteins found in eukaryotic cells.

Kinesins move along microtubule (MT) filaments and are powered by the hydrolysis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (thus kinesins are ATPases, a type of enzy ...

, and ingoing return traffic is provided by dynein

Dyneins are a family of cytoskeletal motor proteins that move along microtubules in cells. They convert the chemical energy stored in ATP to mechanical work. Dynein transports various cellular cargos, provides forces and displacements importa ...

. Dynein is minus-end directed. There are many forms of kinesin and dynein motor proteins, and each is thought to carry a different cargo. The studies on transport in the axon led to the naming of kinesin.

Myelination

myelin

Myelin is a lipid-rich material that surrounds nerve cell axons (the nervous system's "wires") to insulate them and increase the rate at which electrical impulses (called action potentials) are passed along the axon. The myelinated axon can be ...

ated, or unmyelinated. This is the provision of an insulating layer, called a myelin sheath. The myelin membrane is unique in its relatively high lipid to protein ratio.

In the peripheral nervous system axons are myelinated by glial cells

Glia, also called glial cells (gliocytes) or neuroglia, are non-neuronal cells in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and the peripheral nervous system that do not produce electrical impulses. They maintain homeostasis, form mye ...

known as Schwann cell

Schwann cells or neurolemmocytes (named after German physiologist Theodor Schwann) are the principal glia of the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Glial cells function to support neurons and in the PNS, also include satellite cells, olfactory ensh ...

s. In the central nervous system the myelin sheath is provided by another type of glial cell, the oligodendrocyte

Oligodendrocytes (), or oligodendroglia, are a type of neuroglia whose main functions are to provide support and insulation to axons in the central nervous system of jawed vertebrates, equivalent to the function performed by Schwann cells in the ...

. Schwann cells myelinate a single axon. An oligodendrocyte can myelinate up to 50 axons.

The composition of myelin is different in the two types. In the CNS the major myelin protein is proteolipid protein

Proteolipid protein 1 (PLP1) is a form of myelin proteolipid protein (PLP). Mutations in ''PLP1'' are associated with Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease. It is a 4 transmembrane domain protein which is proposed to bind other copies of itself on the ...

, and in the PNS it is myelin basic protein

Myelin basic protein (MBP) is a protein believed to be important in the process of myelination of nerves in the nervous system. The myelin sheath is a multi-layered membrane, unique to the nervous system, that functions as an insulator to greatly ...

.

Nodes of Ranvier

Nodes of Ranvier

In neuroscience and anatomy, nodes of Ranvier ( ), also known as myelin-sheath gaps, occur along a myelinated axon where the axolemma is exposed to the extracellular space. Nodes of Ranvier are uninsulated and highly enriched in ion channels, al ...

(also known as ''myelin sheath gaps'') are short unmyelinated segments of a myelinated axon, which are found periodically interspersed between segments of the myelin sheath. Therefore, at the point of the node of Ranvier, the axon is reduced in diameter. These nodes are areas where action potentials can be generated. In saltatory conduction

In neuroscience, saltatory conduction () is the propagation of action potentials along myelinated axons from one node of Ranvier to the next node, increasing the conduction velocity of action potentials. The uninsulated nodes of Ranvier are th ...

, electrical currents produced at each node of Ranvier are conducted with little attenuation to the next node in line, where they remain strong enough to generate another action potential. Thus in a myelinated axon, action potentials effectively "jump" from node to node, bypassing the myelinated stretches in between, resulting in a propagation speed much faster than even the fastest unmyelinated axon can sustain.

Axon terminals

An axon can divide into many branches called telodendria (Greek for 'end of tree'). At the end of each telodendron is anaxon terminal

Axon terminals (also called synaptic boutons, terminal boutons, or end-feet) are distal terminations of the telodendria (branches) of an axon. An axon, also called a nerve fiber, is a long, slender projection of a nerve cell, or neuron, that condu ...

(also called a synaptic bouton, or terminal bouton). Axon terminals contain synaptic vesicle

In a neuron, synaptic vesicles (or neurotransmitter vesicles) store various neurotransmitters that are released at the synapse. The release is regulated by a voltage-dependent calcium channel. Vesicles are essential for propagating nerve impulse ...

s that store the neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a synapse. The cell receiving the signal, any main body part or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

Neuro ...

for release at the synapse

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that permits a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or to the target effector cell.

Synapses are essential to the transmission of nervous impulses from ...

. This makes multiple synaptic connections with other neurons possible. Sometimes the axon of a neuron may synapse onto dendrites of the same neuron, when it is known as an autapse An autapse is a chemical or electrical synapse from a neuron onto itself. It can also be described as a synapse formed by the axon of a neuron on its own dendrites, ''in vivo'' or ''in vitro''.

History

The term "autapse" was first coined in 1972 ...

.

Action potentials

Most axons carry signals in the form of action potentials, which are discrete electrochemical impulses that travel rapidly along an axon, starting at the cell body and terminating at points where the axon makes synaptic contact with target cells. The defining characteristic of an action potential is that it is "all-or-nothing"every action potential that an axon generates has essentially the same size and shape. This all-or-nothing characteristic allows action potentials to be transmitted from one end of a long axon to the other without any reduction in size. There are, however, some types of neurons with short axons that carry graded electrochemical signals, of variable amplitude. When an action potential reaches a presynaptic terminal, it activates the synaptic transmission process. The first step is rapid opening of calcium ion channels in the membrane of the axon, allowing calcium ions to flow inward across the membrane. The resulting increase in intracellular calcium concentration causessynaptic vesicle

In a neuron, synaptic vesicles (or neurotransmitter vesicles) store various neurotransmitters that are released at the synapse. The release is regulated by a voltage-dependent calcium channel. Vesicles are essential for propagating nerve impulse ...

s (tiny containers enclosed by a lipid membrane) filled with a neurotransmitter chemical to fuse with the axon's membrane and empty their contents into the extracellular space. The neurotransmitter is released from the presynaptic nerve through exocytosis

Exocytosis () is a form of active transport and bulk transport in which a cell transports molecules (e.g., neurotransmitters and proteins) out of the cell ('' exo-'' + ''cytosis''). As an active transport mechanism, exocytosis requires the use o ...

. The neurotransmitter chemical then diffuses across to receptors located on the membrane of the target cell. The neurotransmitter binds to these receptors and activates them. Depending on the type of receptors that are activated, the effect on the target cell can be to excite the target cell, inhibit it, or alter its metabolism in some way. This entire sequence of events often takes place in less than a thousandth of a second. Afterward, inside the presynaptic terminal, a new set of vesicles is moved into position next to the membrane, ready to be released when the next action potential arrives. The action potential is the final electrical step in the integration of synaptic messages at the scale of the neuron.

Extracellular recordings of action potential propagation in axons has been demonstrated in freely moving animals. While extracellular somatic action potentials have been used to study cellular activity in freely moving animals such as place cells

A place cell is a kind of pyramidal neuron in the hippocampus that becomes active when an animal enters a particular place in its environment, which is known as the place field. Place cells are thought to act collectively as a cognitive represe ...

, axonal activity in both white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

and gray matter

Grey matter is a major component of the central nervous system, consisting of neuronal cell bodies, neuropil (dendrites and unmyelinated axons), glial cells (astrocytes and oligodendrocytes), synapses, and capillaries. Grey matter is distinguis ...

can also be recorded. Extracellular recordings of axon action potential propagation is distinct from somatic action potentials in three ways: 1. The signal has a shorter peak-trough duration (~150μs) than of pyramidal cells (~500μs) or interneurons (~250μs). 2. The voltage change is triphasic. 3. Activity recorded on a tetrode is seen on only one of the four recording wires. In recordings from freely moving rats, axonal signals have been isolated in white matter tracts including the alveus and the corpus callosum as well hippocampal gray matter.

In fact, the generation of action potentials in vivo is sequential in nature, and these sequential spikes constitute the digital codes in the neurons. Although previous studies indicate an axonal origin of a single spike evoked by short-term pulses, physiological signals in vivo trigger the initiation of sequential spikes at the cell bodies of the neurons.

In addition to propagating action potentials to axonal terminals, the axon is able to amplify the action potentials, which makes sure a secure propagation of sequential action potentials toward the axonal terminal. In terms of molecular mechanisms, voltage-gated sodium channel

Sodium channels are integral membrane proteins that form ion channels, conducting sodium ions (Na+) through a cell's membrane. They belong to the superfamily of cation channels and can be classified according to the trigger that opens the channel ...

s in the axons possess lower threshold

Threshold may refer to:

Architecture

* Threshold (door), the sill of a door

Media

* ''Threshold'' (1981 film)

* ''Threshold'' (TV series), an American science fiction drama series produced during 2005-2006

* "Threshold" (''Stargate SG-1''), ...

and shorter refractory period in response to short-term pulses.

Development and growth

Development

The development of the axon to its target, is one of the six major stages in the overalldevelopment of the nervous system

The development of the nervous system, or neural development (neurodevelopment), refers to the processes that generate, shape, and reshape the nervous system of animals, from the earliest stages of embryonic development to adulthood. The fiel ...

. Studies done on cultured hippocampal

The hippocampus (via Latin from Greek , 'seahorse') is a major component of the brain of humans and other vertebrates. Humans and other mammals have two hippocampi, one in each side of the brain. The hippocampus is part of the limbic system, an ...

neurons suggest that neurons initially produce multiple neurite

A neurite or neuronal process refers to any projection from the cell body of a neuron. This projection can be either an axon or a dendrite. The term is frequently used when speaking of immature or developing neurons, especially of cells in culture ...

s that are equivalent, yet only one of these neurites is destined to become the axon. It is unclear whether axon specification precedes axon elongation or vice versa, although recent evidence points to the latter. If an axon that is not fully developed is cut, the polarity can change and other neurites can potentially become the axon. This alteration of polarity only occurs when the axon is cut at least 10 μm shorter than the other neurites. After the incision is made, the longest neurite will become the future axon and all the other neurites, including the original axon, will turn into dendrites. Imposing an external force on a neurite, causing it to elongate, will make it become an axon. Nonetheless, axonal development is achieved through a complex interplay between extracellular signaling, intracellular signaling and cytoskeletal

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is compo ...

dynamics.

Extracellular signaling

The extracellular signals that propagate through theextracellular matrix

In biology, the extracellular matrix (ECM), also called intercellular matrix, is a three-dimensional network consisting of extracellular macromolecules and minerals, such as collagen, enzymes, glycoproteins and hydroxyapatite that provide stru ...

surrounding neurons play a prominent role in axonal development. These signaling molecules include proteins, neurotrophic factors

Neurotrophic factors (NTFs) are a family of biomolecules – nearly all of which are peptides or small proteins – that support the growth, survival, and differentiation of both developing and mature neurons. Most NTFs exert their tro ...

, and extracellular matrix and adhesion molecules.

Netrin

Netrins are a class of proteins involved in axon guidance. They are named after the Sanskrit word "netr", which means "one who guides". Netrins are genetically conserved across nematode worms, fruit flies, frogs, mice, and humans. Structurally, ...

(also known as UNC-6) a secreted protein, functions in axon formation. When the UNC-5

UNC-5 is a receptor for netrins including UNC-6. Netrins are a class of proteins involved in axon guidance. UNC-5 uses repulsion to direct axons while the other netrin receptor UNC-40 attracts axons to the source of netrin production.

Discovery ...

netrin receptor is mutated, several neurites are irregularly projected out of neurons and finally a single axon is extended anteriorly.Neuroglia

Glia, also called glial cells (gliocytes) or neuroglia, are non-neuronal cells in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and the peripheral nervous system that do not produce electrical impulses. They maintain homeostasis, form mye ...

and pioneer neuron

A pioneer neuron is a cell that is a derivative of the preplate in the early stages of corticogenesis of the brain. Pioneer neurons settle in the marginal zone of the cortex and project to sub-cortical levels. In the rat, pioneer neurons are only ...

s express UNC-6 to provide global and local netrin cues for guiding migrations in ''C. elegans'' The neurotrophic factorsnerve growth factor

Nerve growth factor (NGF) is a neurotrophic factor and neuropeptide primarily involved in the regulation of growth, maintenance, proliferation, and survival of certain target neurons. It is perhaps the prototypical growth factor, in that it was on ...

(NGF), brain-derived neurotrophic factor

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), or abrineurin, is a protein found in the and the periphery. that, in humans, is encoded by the ''BDNF'' gene. BDNF is a member of the neurotrophin family of growth factors, which are related to the cano ...

(BDNF) and neurotrophin-3

Neurotrophin-3 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''NTF3'' gene.

The protein encoded by this gene, NT-3, is a neurotrophic factor in the NGF (Nerve Growth Factor) family of neurotrophins. It is a protein growth factor which has activi ...

(NTF3) are also involved in axon development and bind to Trk receptor

Trk receptors are a family of tyrosine kinases that regulates synaptic strength and plasticity in the mammalian nervous system. Trk receptors affect neuronal survival and differentiation through several signaling cascades. However, the activation ...

s.

The ganglioside

A ganglioside is a molecule composed of a glycosphingolipid (ceramide and oligosaccharide) with one or more sialic acids (e.g. ''N''-acetylneuraminic acid, NANA) linked on the sugar chain. NeuNAc, an acetylated derivative of the carbohydrate sia ...

-converting enzyme plasma membrane ganglioside sialidase

Exo-α-sialidase (EC 3.2.1.18, sialidase, neuraminidase; systematic name acetylneuraminyl hydrolase) is a glycoside hydrolase that cleaves the glycosidic linkages of neuraminic acids:

: Hydrolysis of α-(2→3)-, α-(2→6)-, α-(2→8)- glycos ...

(PMGS), which is involved in the activation of TrkA

Tropomyosin receptor kinase A (TrkA), also known as high affinity nerve growth factor receptor, neurotrophic tyrosine kinase receptor type 1, or TRK1-transforming tyrosine kinase protein is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''NTRK1'' gen ...

at the tip of neutrites, is required for the elongation of axons. PMGS asymmetrically distributes to the tip of the neurite that is destined to become the future axon.

Intracellular signaling

During axonal development, the activity ofPI3K

Phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks), also called phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases, are a family of enzymes involved in cellular functions such as cell growth, proliferation, differentiation, motility, survival and intracellular trafficking, which i ...

is increased at the tip of destined axon. Disrupting the activity of PI3K inhibits axonal development. Activation of PI3K results in the production of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate

Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PtdIns(3,4,5)''P''3), abbreviated PIP3, is the product of the class I phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI 3-kinases) phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2). It is a phospholipid th ...

(PtdIns) which can cause significant elongation of a neurite, converting it into an axon. As such, the overexpression of phosphatase

In biochemistry, a phosphatase is an enzyme that uses water to cleave a phosphoric acid Ester, monoester into a phosphate ion and an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol. Because a phosphatase enzyme catalysis, catalyzes the hydrolysis of its Substrate ...

s that dephosphorylate PtdIns leads into the failure of polarization.

Cytoskeletal dynamics

The neurite with the lowestactin

Actin is a family of globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all eukaryotic cells, where it may be present at a concentration of over ...

filament content will become the axon. PGMS concentration and f-actin

Actin is a family of globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all eukaryotic cells, where it may be present at a concentration of over ...

content are inversely correlated; when PGMS becomes enriched at the tip of a neurite, its f-actin content is substantially decreased. In addition, exposure to actin-depolimerizing drugs and toxin B (which inactivates Rho-signaling) causes the formation of multiple axons. Consequently, the interruption of the actin network in a growth cone will promote its neurite to become the axon.

Growth

Growing axons move through their environment via the

Growing axons move through their environment via the growth cone

A growth cone is a large actin-supported extension of a developing or regenerating neurite seeking its synaptic target. It is the growth cone that drives axon growth. Their existence was originally proposed by Spanish histologist Santiago Ramó ...

, which is at the tip of the axon. The growth cone has a broad sheet-like extension called a lamellipodium

The lamellipodium (plural lamellipodia) (from Latin ''lamella'', related to ', "thin sheet", and the Greek radical ''pod-'', "foot") is a cytoskeletal protein actin projection on the leading edge of the cell. It contains a quasi-two-dimensional ...

which contain protrusions called filopodia

Filopodia (singular filopodium) are slender cytoplasmic projections that extend beyond the leading edge of lamellipodia in migrating cells. Within the lamellipodium, actin ribs are known as ''microspikes'', and when they extend beyond the lame ...

. The filopodia are the mechanism by which the entire process adheres to surfaces and explores the surrounding environment. Actin plays a major role in the mobility of this system. Environments with high levels of cell adhesion molecule

Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) are a subset of cell surface proteins that are involved in the binding of cells with other cells or with the extracellular matrix (ECM), in a process called cell adhesion. In essence, CAMs help cells stick to each ...

s (CAMs) create an ideal environment for axonal growth. This seems to provide a "sticky" surface for axons to grow along. Examples of CAMs specific to neural systems include N-CAM

Neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), also called CD56, is a homophilic binding glycoprotein expressed on the surface of neurons, glia and skeletal muscle. Although CD56 is often considered a marker of neural lineage commitment due to its discover ...

, TAG-1an axonal glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as glycos ...

and MAG Mag, MAG or mags may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''MAG'' (video game), 2010

* ''Mag'' (Slovenian magazine), 1995–2010

* '' The Mag'', a British music magazine

Businesses and organisations

* MacKenzie Art Gallery, in Regina, Sask ...

, all of which are part of the immunoglobulin

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

superfamily. Another set of molecules called extracellular matrix

In biology, the extracellular matrix (ECM), also called intercellular matrix, is a three-dimensional network consisting of extracellular macromolecules and minerals, such as collagen, enzymes, glycoproteins and hydroxyapatite that provide stru ...

-adhesion molecule

Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) are a subset of cell surface proteins that are involved in the binding of cells with other cells or with the extracellular matrix (ECM), in a process called cell adhesion. In essence, CAMs help cells stick to each ...

s also provide a sticky substrate for axons to grow along. Examples of these molecules include laminin

Laminins are a family of glycoproteins of the extracellular matrix of all animals. They are major components of the basal lamina (one of the layers of the basement membrane), the protein network foundation for most cells and organs. The laminins ...

, fibronectin

Fibronectin is a high- molecular weight (~500-~600 kDa) glycoprotein of the extracellular matrix that binds to membrane-spanning receptor proteins called integrins. Fibronectin also binds to other extracellular matrix proteins such as collage ...

, tenascin

Tenascins are extracellular matrix glycoproteins. They are abundant in the extracellular matrix of developing vertebrate embryos and they reappear around healing wounds and in the stroma of some tumors.

Types

There are four members of the tenasc ...

, and perlecan

Perlecan (PLC) also known as basement membrane-specific heparan sulfate proteoglycan core protein (HSPG) or heparan sulfate proteoglycan 2 (HSPG2), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''HSPG2'' gene. The HSPG2 gene codes for a 4,391 amin ...

. Some of these are surface bound to cells and thus act as short range attractants or repellents. Others are difusible ligands and thus can have long range effects.

Cells called guidepost cells

Guidepost cells are cells which assist in the subcellular organization of both neural axon growth and migration. They act as intermediate targets for long and complex axonal growths by creating short and easy pathways, leading axon growth cones tow ...

assist in the guidance

Guidance may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Guidance'' (album), by American instrumental rock band Russian Circles

* ''Guidance'' (film), a Canadian comedy film released in 2014

* ''Guidance'' (web series), a 2015–2017 American web series

* "G ...

of neuronal axon growth. These cells that help axon guidance

Axon guidance (also called axon pathfinding) is a subfield of neural development concerning the process by which neurons send out axons to reach their correct targets. Axons often follow very precise paths in the nervous system, and how they mana ...

, are typically other neurons that are sometimes immature. When the axon has completed its growth at its connection to the target, the diameter of the axon can increase by up to five times, depending on the speed of conduction required.

It has also been discovered through research that if the axons of a neuron were damaged, as long as the soma (the cell body of a neuron) is not damaged, the axons would regenerate and remake the synaptic connections with neurons with the help of guidepost cells

Guidepost cells are cells which assist in the subcellular organization of both neural axon growth and migration. They act as intermediate targets for long and complex axonal growths by creating short and easy pathways, leading axon growth cones tow ...

. This is also referred to as neuroregeneration

Neuroregeneration refers to the regrowth or repair of nervous tissues, cells or cell products. Such mechanisms may include generation of new neurons, glia, axons, myelin, or synapses. Neuroregeneration differs between the peripheral nervous syste ...

.

Nogo-A is a type of neurite outgrowth inhibitory component that is present in the central nervous system myelin membranes (found in an axon). It has a crucial role in restricting axonal regeneration in adult mammalian central nervous system. In recent studies, if Nogo-A is blocked and neutralized, it is possible to induce long-distance axonal regeneration which leads to enhancement of functional recovery in rats and mouse spinal cord. This has yet to be done on humans. A recent study has also found that macrophage

Macrophages (abbreviated as M φ, MΦ or MP) ( el, large eaters, from Greek ''μακρός'' (') = large, ''φαγεῖν'' (') = to eat) are a type of white blood cell of the immune system that engulfs and digests pathogens, such as cancer cel ...

s activated through a specific inflammatory pathway activated by the Dectin-1 receptor are capable of promoting axon recovery, also however causing neurotoxicity in the neuron.

Length regulation

Axons vary largely in length from a few micrometers up to meters in some animals. This emphasizes that there must be a cellular length regulation mechanism allowing the neurons both to sense the length of their axons and to control their growth accordingly. It was discovered thatmotor proteins

Motor proteins are a class of molecular motors that can move along the cytoplasm of cells. They convert chemical energy into mechanical work by the hydrolysis of ATP. Flagellar rotation, however, is powered by a proton pump.

Cellular functions ...

play an important role in regulating the length of axons. Based on this observation, researchers developed an explicit model for axonal growth describing how motor proteins could affect the axon length on the molecular level. These studies suggest that motor proteins carry signaling molecules from the soma to the growth cone and vice versa whose concentration oscillates in time with a length-dependent frequency.

Classification

The axons of neurons in the humanperipheral nervous system

The peripheral nervous system (PNS) is one of two components that make up the nervous system of bilateral animals, with the other part being the central nervous system (CNS). The PNS consists of nerves and ganglia, which lie outside the brain ...

can be classified based on their physical features and signal conduction properties. Axons were known to have different thicknesses (from 0.1 to 20 µm) and these differences were thought to relate to the speed at which an action potential could travel along the axonits ''conductance velocity''. Erlanger and Gasser proved this hypothesis, and identified several types of nerve fiber, establishing a relationship between the diameter of an axon and its nerve conduction velocity. They published their findings in 1941 giving the first classification of axons.

Axons are classified in two systems. The first one introduced by Erlanger and Gasser, grouped the fibers into three main groups using the letters A, B, and C. These groups, group A

Group A is a set of motorsport regulations administered by the FIA covering production derived vehicles intended for competition, usually in touring car racing and rallying. In contrast to the short-lived Group B and Group C, Group A vehicles w ...

, group B

Group B was a set of regulations for grand touring (GT) vehicles used in sports car racing and rallying introduced in 1982 by the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). Although permitted to enter a GT class of the World Sportscar ...

, and group C

Group C was a category of sports car racing introduced by the FIA in 1982 and continuing until 1993, with ''Group A'' for touring cars and ''Group B'' for GTs.

It was designed to replace both Group 5 special production cars (closed top touri ...

include both the sensory fibers ( afferents) and the motor fibers ( efferents). The first group A, was subdivided into alpha, beta, gamma, and delta fibersAα, Aβ, Aγ, and Aδ. The motor neurons of the different motor fibers, were the lower motor neuron

Lower motor neurons (LMNs) are motor neurons located in either the anterior grey column, anterior nerve roots (spinal lower motor neurons) or the cranial nerve nuclei of the brainstem and cranial nerves with motor function (cranial nerve lower mo ...

salpha motor neuron

Alpha (α) motor neurons (also called alpha motoneurons), are large, multipolar lower motor neurons of the brainstem and spinal cord. They innervate extrafusal muscle fibers of skeletal muscle and are directly responsible for initiating their con ...

, beta motor neuron

Beta motor neurons (β motor neurons), also called beta motoneurons, are a kind of lower motor neuron, along with alpha motor neurons and gamma motor neurons. Beta motor neurons innervate intrafusal fibers of muscle spindles with collaterals to ex ...

, and gamma motor neuron

A gamma motor neuron (γ motor neuron), also called gamma motoneuron, or fusimotor neuron, is a type of lower motor neuron that takes part in the process of muscle contraction, and represents about 30% of ( Aγ) fibers going to the muscle. Like al ...

having the Aα, Aβ, and Aγ nerve fibers, respectively.

Later findings by other researchers identified two groups of Aa fibers that were sensory fibers. These were then introduced into a system that only included sensory fibers (though some of these were mixed nerves and were also motor fibers). This system refers to the sensory groups as Types and uses Roman numerals: Type Ia, Type Ib, Type II, Type III, and Type IV.

Motor

Lower motor neurons have two kind of fibers:Different

sensory receptors

Sensory neurons, also known as afferent neurons, are neurons in the nervous system, that convert a specific type of stimulus, via their receptors, into action potentials or graded potentials. This process is called sensory transduction. The cell ...

innervate different types of nerve fibers. Proprioceptor

Proprioception ( ), also referred to as kinaesthesia (or kinesthesia), is the sense of self-movement, force, and body position. It is sometimes described as the "sixth sense".

Proprioception is mediated by proprioceptors, mechanosensory neurons ...

s are innervated by type Ia, Ib and II sensory fibers, mechanoreceptor

A mechanoreceptor, also called mechanoceptor, is a sensory receptor that responds to mechanical pressure or distortion. Mechanoreceptors are innervated by sensory neurons that convert mechanical pressure into electrical signals that, in animals, ...

s by type II and III sensory fibers and nociceptor

A nociceptor ("pain receptor" from Latin ''nocere'' 'to harm or hurt') is a sensory neuron that responds to damaging or potentially damaging stimuli by sending "possible threat" signals to the spinal cord and the brain. The brain creates the sens ...

s and thermoreceptors

A thermoreceptor is a non-specialised sense receptor, or more accurately the receptive portion of a sensory neuron, that codes absolute and relative changes in temperature, primarily within the innocuous range. In the mammalian peripheral nervous s ...

by type III and IV sensory fibers.

Autonomic

Theautonomic nervous system

The autonomic nervous system (ANS), formerly referred to as the vegetative nervous system, is a division of the peripheral nervous system that supplies viscera, internal organs, smooth muscle and glands. The autonomic nervous system is a control ...

has two kinds of peripheral fibers:

Clinical significance

In order of degree of severity, injury to a nerve can be described asneurapraxia

Neurapraxia is a disorder of the peripheral nervous system in which there is a temporary loss of motor and sensory function due to blockage of nerve conduction, usually lasting an average of six to eight weeks before full recovery. Neurapraxia is ...

, axonotmesis

Axonotmesis is an injury to the peripheral nerve of one of the extremities of the body. The axons and their myelin sheath are damaged in this kind of injury, but the endoneurium, perineurium and epineurium remain intact. Motor and sensory functions ...

, or neurotmesis

Neurotmesis (in Greek tmesis signifies "to cut") is part of Seddon's classification scheme used to classify nerve damage. It is the most serious nerve injury in the scheme. In this type of injury, both the nerve and the nerve sheath are disrupt ...

.

Concussion

A concussion, also known as a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), is a head injury that temporarily affects brain functioning. Symptoms may include loss of consciousness (LOC); memory loss; headaches; difficulty with thinking, concentration, ...

is considered a mild form of diffuse axonal injury

Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) is a brain injury in which scattered lesions occur over a widespread area in white matter tracts as well as grey matter. DAI is one of the most common and devastating types of traumatic brain injury and is a major cause ...

. Axonal injury can also cause central chromatolysis

Central chromatolysis is a histopathologic change seen in the cell body of a neuron, where the chromatin and cell nucleus are pushed to the cell periphery, in response to axonal injury.Neuropathology - Basic Reactions. University of Vermont. URLh ...

. The dysfunction of axons in the nervous system is one of the major causes of many inherited neurological disorder

A neurological disorder is any disorder of the nervous system. Structural, biochemical or electrical abnormalities in the brain, spinal cord or other nerves can result in a range of symptoms. Examples of symptoms include paralysis, muscle weakn ...

s that affect both peripheral and central neurons.

When an axon is crushed, an active process of axonal degeneration

Wallerian degeneration is an active process of degeneration that results when a nerve fiber is cut or crushed and the part of the axon distal to the injury (i.e. farther from the neuron's cell body) degenerates. A related process of dying back or ...

takes place at the part of the axon furthest from the cell body. This degeneration takes place quickly following the injury, with the part of the axon being sealed off at the membranes and broken down by macrophages. This is known as Wallerian degeneration

Wallerian degeneration is an active process of degeneration that results when a nerve fiber is cut or crushed and the part of the axon distal to the injury (i.e. farther from the neuron's cell body) degenerates. A related process of dying back o ...

.Trauma and Wallerian Degeneration,

University of California, San Francisco

The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is a public land-grant research university in San Francisco, California. It is part of the University of California system and is dedicated entirely to health science and life science. It cond ...

Dying back of an axon can also take place in many neurodegenerative diseases, particularly when axonal transport is impaired, this is known as Wallerian-like degeneration. Studies suggest that the degeneration happens as

a result of the axonal protein NMNAT2

Nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase 2 (NMNAT2) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ''NMNAT2'' gene.

This gene product belongs to the nicotinamide-nucleotide adenylyltransferase (NMNAT) enzyme family, members of which catalyze ...

, being prevented from reaching all of the axon.

Demyelination of axons causes the multitude of neurological symptoms found in the disease multiple sclerosis

Multiple (cerebral) sclerosis (MS), also known as encephalomyelitis disseminata or disseminated sclerosis, is the most common demyelinating disease, in which the insulating covers of nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord are damaged. This d ...

.

Dysmyelination

Myelin is a lipid-rich material that surrounds nerve cell axons (the nervous system's "wires") to Insulator (electricity), insulate them and increase the rate at which electrical impulses (called action potentials) are passed along the axon. The ...

is the abnormal formation of the myelin sheath. This is implicated in several leukodystrophies

Leukodystrophies are a group of usually inherited disorders characterized by degeneration of the white matter in the brain. The word ''leukodystrophy'' comes from the Greek roots ''leuko'', "white", ''dys'', "abnormal" and ''troph'', "growth". Th ...

, and also in schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by continuous or relapsing episodes of psychosis. Major symptoms include hallucinations (typically hearing voices), delusions, and disorganized thinking. Other symptoms include social withdra ...

.

A severe traumatic brain injury

A traumatic brain injury (TBI), also known as an intracranial injury, is an injury to the brain caused by an external force. TBI can be classified based on severity (ranging from mild traumatic brain injury TBI/concussionto severe traumatic b ...

can result in widespread lesions to nerve tracts damaging the axons in a condition known as diffuse axonal injury

Diffuse axonal injury (DAI) is a brain injury in which scattered lesions occur over a widespread area in white matter tracts as well as grey matter. DAI is one of the most common and devastating types of traumatic brain injury and is a major cause ...

. This can lead to a persistent vegetative state

A persistent vegetative state (PVS) or post-coma unresponsiveness (PCU) is a disorder of consciousness in which patients with severe brain damage are in a state of partial arousal rather than true awareness. After four weeks in a vegetative stat ...

. It has been shown in studies on the rat

Rats are various medium-sized, long-tailed rodents. Species of rats are found throughout the order Rodentia, but stereotypical rats are found in the genus ''Rattus''. Other rat genera include ''Neotoma'' ( pack rats), ''Bandicota'' (bandicoot ...

that axonal damage from a single mild traumatic brain injury, can leave a susceptibility to further damage, after repeated mild traumatic brain injuries.

A nerve guidance conduit

A nerve guidance conduit (also referred to as an artificial nerve conduit or artificial nerve graft, as opposed to an autograft) is an artificial means of guiding axonal regrowth to facilitate nerve regeneration and is one of several clinical trea ...

is an artificial means of guiding axon growth to enable neuroregeneration

Neuroregeneration refers to the regrowth or repair of nervous tissues, cells or cell products. Such mechanisms may include generation of new neurons, glia, axons, myelin, or synapses. Neuroregeneration differs between the peripheral nervous syste ...

, and is one of the many treatments used for different kinds of nerve injury

Nerve injury is an injury to nervous tissue. There is no single classification system that can describe all the many variations of nerve injuries. In 1941, Seddon introduced a classification of nerve injuries based on three main types of nerve f ...

.

History

German anatomistOtto Friedrich Karl Deiters

Otto Friedrich Karl Deiters (; 15 November 1834 – 5 December 1863) was a German neuroanatomist. He was born in Bonn, studied at the University of Bonn, and spent most of his professional career in Bonn. He is remembered for his microscopic ...

is generally credited with the discovery of the axon by distinguishing it from the dendrites. Swiss Rüdolf Albert von Kölliker and German Robert Remak

Robert Remak (26 July 1815 – 29 August 1865) was a Jewish Polish-German embryologist, physiologist, and neurologist, born in Posen, Prussia, who discovered that the origin of cells was by the division of pre-existing cells. as well as several ...

were the first to identify and characterize the axon initial segment. Kölliker named the axon in 1896. Louis-Antoine Ranvier

Louis-Antoine Ranvier (2 October 1835 – 22 March 1922) was a French physician, pathologist, anatomist and histologist, who discovered the nodes of Ranvier, regularly spaced discontinuities of the myelin sheath, occurring at varying intervals alon ...

was the first to describe the gaps or nodes found on axons and for this contribution these axonal features are now commonly referred to as the nodes of Ranvier

In neuroscience and anatomy, nodes of Ranvier ( ), also known as myelin-sheath gaps, occur along a myelinated axon where the axolemma is exposed to the extracellular space. Nodes of Ranvier are uninsulated and highly enriched in ion channels, al ...

. Santiago Ramón y Cajal

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (; 1 May 1852 – 17 October 1934) was a Spanish neuroscientist, pathologist, and histologist specializing in neuroanatomy and the central nervous system. He and Camillo Golgi received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Med ...

, a Spanish anatomist, proposed that axons were the output components of neurons, describing their functionality. Joseph Erlanger

Joseph Erlanger (January 5, 1874 – December 5, 1965) was an American physiologist who is best known for his contributions to the field of neuroscience. Together with Herbert Spencer Gasser, he identified several varieties of nerve fiber and es ...

and Herbert Gasser

Herbert Spencer Gasser (July 5, 1888 – May 11, 1963) was an American physiologist, and recipient of the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1944 for his work with action potentials in nerve fibers while on the faculty of Washington Unive ...

earlier developed the classification system for peripheral nerve fibers, based on axonal conduction velocity, myelin

Myelin is a lipid-rich material that surrounds nerve cell axons (the nervous system's "wires") to insulate them and increase the rate at which electrical impulses (called action potentials) are passed along the axon. The myelinated axon can be ...

ation, fiber size etc. Alan Hodgkin

Sir Alan Lloyd Hodgkin (5 February 1914 – 20 December 1998) was an English physiologist and biophysicist who shared the 1963 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Andrew Huxley and John Eccles.

Early life and education

Hodgkin was b ...

and Andrew Huxley

Sir Andrew Fielding Huxley (22 November 191730 May 2012) was an English physiologist and biophysicist. He was born into the prominent Huxley family. After leaving Westminster School in central London, he went to Trinity College, Cambridge on ...

also employed the squid giant axon (1939) and by 1952 they had obtained a full quantitative description of the ionic basis of the action potential, leading to the formulation of the Hodgkin–Huxley model

The Hodgkin–Huxley model, or conductance-based model, is a mathematical model that describes how action potentials in neurons are initiated and propagated. It is a set of nonlinear differential equations that approximates the electrical charact ...

. Hodgkin and Huxley were awarded jointly the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

for this work in 1963. The formulae detailing axonal conductance were extended to vertebrates in the Frankenhaeuser–Huxley equations. The understanding of the biochemical basis for action potential propagation has advanced further, and includes many details about individual ion channel

Ion channels are pore-forming membrane proteins that allow ions to pass through the channel pore. Their functions include establishing a resting membrane potential, shaping action potentials and other electrical signals by gating the flow of io ...

s.

Other animals

The axons ininvertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

s have been extensively studied. The longfin inshore squid

The longfin inshore squid (''Doryteuthis pealeii'') is a species of squid of the family Loliginidae.

Description

This species of squid is often seen with a reddish hue, but like many types of squid can manipulate its color, varying from a deep ...

, often used as a model organism

A model organism (often shortened to model) is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workin ...

has the longest known axon. The giant squid

The giant squid (''Architeuthis dux'') is a species of deep-ocean dwelling squid in the family Architeuthidae. It can grow to a tremendous size, offering an example of abyssal gigantism: recent estimates put the maximum size at around Trace ...

has the largest axon known. Its size ranges from 0.5 (typically) to 1 mm in diameter and is used in the control of its jet propulsion

Jet propulsion is the propulsion of an object in one direction, produced by ejecting a jet of fluid in the opposite direction. By Newton's third law, the moving body is propelled in the opposite direction to the jet. Reaction engines operating o ...

system. The fastest recorded conduction speed of 210 m/s, is found in the ensheathed axons of some pelagic Penaeid shrimp

Penaeidae is a family of marine crustaceans in the suborder Dendrobranchiata, which are often referred to as penaeid shrimp or penaeid prawns. The Penaeidae contain many species of economic importance, such as the tiger prawn, whiteleg shrimp, ...

s and the usual range is between 90 and 200 meters/s ( cf 100–120 m/s for the fastest myelinated vertebrate axon.)

In other cases as seen in rat studies an axon originates from a dendrite; such axons are said to have "dendritic origin". Some axons with dendritic origin similarly have a "proximal" initial segment that starts directly at the axon origin, while others have a "distal" initial segment, discernibly separated from the axon origin. In many species some of the neurons have axons that emanate from the dendrite and not from the cell body, and these are known as axon-carrying dendrites. In many cases, an axon originates at an axon hillock on the soma; such axons are said to have "somatic origin". Some axons with somatic origin have a "proximal" initial segment adjacent the axon hillock, while others have a "distal" initial segment, separated from the soma by an extended axon hillock.

See also

*Electrophysiology