Days after the Szálasi government took power, the capital of Budapest was surrounded by the Soviet

Red Army. German and Hungarian forces tried to hold off the Soviet advance but failed. After fierce fighting, Budapest was taken by the Soviets. A number of pro-German Hungarians retreated to Italy and Germany, where they fought until the end of the war.

In March 1945, Szálasi fled to Germany as the leader of a government in exile, until the surrender of Germany in May 1945.

Independent State of Croatia

On 10 April 1941, the so-called

Independent State of Croatia (''Nezavisna Država Hrvatska'', or NDH), an installed German–Italian puppet state, co-signed the Tripartite Pact. The NDH remained a member of the Axis until the end of Second World War, its forces fighting for Germany even after its territory had been overrun by

Yugoslav Partisans. On 16 April 1941,

Ante Pavelić, a Croatian nationalist and one of the founders of the

Ustaše (''"Croatian Liberation Movement"''), was proclaimed ''

Poglavnik

() was the title used by Ante Pavelić, leader of the World War II Croatian movement Ustaše and of the Independent State of Croatia between 1941 and 1945.

Etymology and usage

The word was first recorded in a 16th-century dictionary compiled ...

'' (leader) of the new regime.

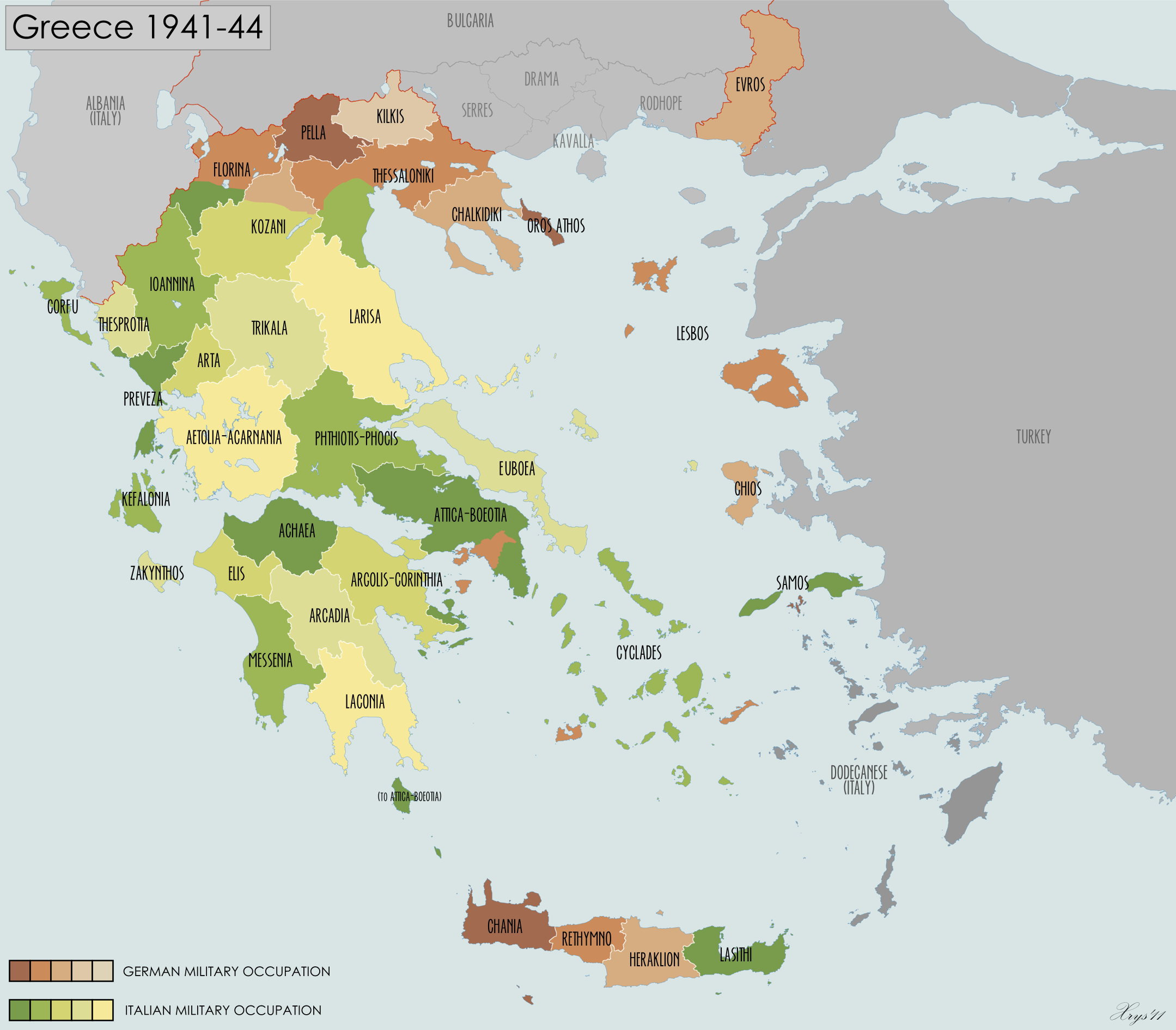

Initially the Ustaše had been heavily influenced by Italy. They were actively supported by Mussolini's

National Fascist Party regime in Italy, which gave the movement training grounds to prepare for war against Yugoslavia, as well as accepting Pavelić as an exile and allowing him to reside in Rome. In 1941 during the Italian invasion of Greece, Mussolini requested that Germany invade Yugoslavia to save the Italian forces in Greece. Hitler reluctantly agreed; Yugoslavia was invaded and the NDH was created. Pavelić led a delegation to Rome and offered the crown of the NDH to an Italian prince of the

House of Savoy

The House of Savoy ( it, Casa Savoia) was a royal dynasty that was established in 1003 in the historical Savoy region. Through gradual expansion, the family grew in power from ruling a small Alpine county north-west of Italy to absolute rule of ...

, who was crowned

Tomislav II. The next day, Pavelić signed the Contracts of Rome with Mussolini, ceding

Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

to Italy and fixing the permanent borders between the NDH and Italy. Italian armed forces were allowed to control all of the coastline of the NDH, effectively giving Italy total control of the Adriatic coastline. When the King of Italy ousted Mussolini from power and Italy capitulated, the NDH became completely under German influence.

The platform of the Ustaše movement proclaimed that Croatians had been oppressed by the Serb-dominated Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and that Croatians deserved to have an independent nation after years of domination by foreign empires. The Ustaše perceived Serbs to be racially inferior to Croats and saw them as infiltrators who were occupying Croatian lands. They saw the extermination and expulsion or deportation of Serbs as necessary to racially purify Croatia. While part of Yugoslavia, many

Croatian nationalists violently opposed the Serb-dominated Yugoslav monarchy, and assassinated

Alexander I of Yugoslavia, together with the

Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization. The regime enjoyed support amongst radical Croatian nationalists. Ustashe forces fought against communist

Yugoslav Partisan guerrilla throughout the war.

Upon coming to power, Pavelić formed the

Croatian Home Guard (''Hrvatsko domobranstvo'') as the official military force of the NDH. Originally authorized at 16,000 men, it grew to a peak fighting force of 130,000. The Croatian Home Guard included an air force and navy, although its navy was restricted in size by the Contracts of Rome. In addition to the Croatian Home Guard, Pavelić was also the supreme commander of the

Ustaše militia, although all NDH military units were generally under the command of the German or Italian formations in their area of operations.

The Ustaše government declared war on the Soviet Union, signed the Anti-Comintern Pact of 1941, and sent troops to Germany's Eastern Front. Ustaše militia were garrisoned in the Balkans, battling the communist partisans.

The Ustaše government applied racial laws on Serbs, Jews, and

Romani people, as well as targeting those opposed to the fascist regime, and after June 1941 deported them to the

Jasenovac concentration camp or to

Nazi concentration camps in Poland. The racial laws were enforced by the Ustaše militia. The exact number of victims of the Ustaše regime is uncertain due to the destruction of documents and varying numbers given by historians. According to the

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., between

320,000 and 340,000 Serbs were killed in the NDH.

[Jasenovac](_blank)

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum web site

Romania

When war erupted in Europe, the economy of the

Kingdom of Romania was already subordinated to the interests of Nazi Germany through a

treaty signed in the spring of 1939. Nevertheless, the country had not totally abandoned pro-British sympathies. Romania had also been allied to the

Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in Ce ...

for most of the interwar era. Following the

invasion of Poland by Germany and the Soviet Union, and the German conquest of France and the

Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

, Romania found itself increasingly isolated; meanwhile, pro-German and pro-Fascist elements began to grow.

The August 1939

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union contained a secret protocol ceding

Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Be ...

, and

Northern Bukovina to the Soviet Union. On June 28, 1940, the Soviet Union

occupied and annexed Bessarabia, as well as part of northern Romania and the

Hertsa region

The Hertsa region, also known as the Hertza region ( uk, Край Герца, Kraj Herca; ro, Ținutul Herța), is a region around the town of Hertsa within Chernivtsi Raion in the southern part of Chernivtsi Oblast in southwestern Ukraine, ne ...

. On 30 August 1940, as a result of the

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

–

Italian arbitrated

Second Vienna Award Romania had to cede

Northern Transylvania

Northern Transylvania ( ro, Transilvania de Nord, hu, Észak-Erdély) was the region of the Kingdom of Romania that during World War II, as a consequence of the August 1940 territorial agreement known as the Second Vienna Award, became part of ...

to Hungary.

Southern Dobruja was ceded to

Bulgaria in September 1940. In an effort to appease the Fascist elements within the country and obtain German protection,

King Carol II appointed the General

Ion Antonescu

Ion Antonescu (; ; – 1 June 1946) was a Romanian military officer and marshal who presided over two successive wartime dictatorships as Prime Minister and ''Conducător'' during most of World War II.

A Romanian Army career officer who made ...

as Prime Minister on September 6, 1940.

Two days later, Antonescu forced the king to abdicate and installed the king's young son

Michael

Michael may refer to:

People

* Michael (given name), a given name

* Michael (surname), including a list of people with the surname Michael

Given name "Michael"

* Michael (archangel), ''first'' of God's archangels in the Jewish, Christian an ...

(Mihai) on the throne, then declared himself ''

Conducător'' ("Leader") with dictatorial powers. The

National Legionary State was proclaimed on 14 September, with the

Iron Guard

The Iron Guard ( ro, Garda de Fier) was a Romanian militant revolutionary fascist movement and political party founded in 1927 by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu as the Legion of the Archangel Michael () or the Legionnaire Movement (). It was strongly ...

ruling together with Antonescu as the sole legal political movement in Romania. Under King Michael I and the military government of Antonescu, Romania signed the

Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive military ...

on November 23, 1940. German troops entered the country on 10 October 1941, officially to train the

Romanian Army. Hitler's directive to the troops on 10 October had stated that "it is necessary to avoid even the slightest semblance of military occupation of Romania". The entrance of German troops in Romania determined Italian dictator

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

to launch an invasion of Greece, starting the

Greco-Italian War. Having secured Hitler's approval in January 1941, Antonescu

ousted the Iron Guard from power.

Romania was subsequently used as a platform for invasions of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. Despite not being involved militarily in the

Invasion of Yugoslavia

The invasion of Yugoslavia, also known as the April War or Operation 25, or ''Projekt 25'' was a German-led attack on the Kingdom of Yugoslavia by the Axis powers which began on 6 April 1941 during World War II. The order for the invasion was p ...

, Romania requested that Hungarian troops not operate in the

Banat. Paulus thus modified the Hungarian plan and kept their troops west of the

Tisza.

Romania joined the German-led invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. Antonescu was the only foreign leader Hitler consulted on military matters and the two would meet no less than ten times throughout the war. Romania re-captured Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina during

Operation Munchen

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Man ...

before conquering further Soviet territory and establishing the

Transnistria Governorate. After the

Siege of Odessa

The siege of Odessa, known to the Soviets as the defence of Odessa, lasted from 8 August until 16 October 1941, during the early phase of Operation Barbarossa, the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II.

Odessa was a port on the ...

, the city became the capital of the Governorate. Romanian troops

fought their way into the Crimea alongside German troops and contributed significantly to the

Siege of Sevastopol. Later, Romanian mountain troops joined the German campaign in the Caucasus, reaching as far as

Nalchik

Nalchik (russian: Нальчик, p=ˈnalʲtɕɪk; Kabardian: //; krc, Нальчик //) is the capital city of the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic, Russia, situated at an altitude of in the foothills of the Caucasus Mountains; about northwe ...

. After suffering devastating losses

at Stalingrad, Romanian officials began secretly negotiating peace conditions with the Allies.

Romania's military industry was small but versatile, able to copy and produce thousands of French, Soviet, German, British, and Czechoslovak weapons systems, as well as producing capable original products. The

Romanian Navy also built sizable warships, such as the minelayer and the submarines and . Hundreds of originally-designed

Romanian Air Force

The Romanian Air Force (RoAF) ( ro, Forțele Aeriene Române) is the air force branch of the Romanian Armed Forces. It has an air force headquarters, an operational command, five airbases and an air defense brigade. Reserve forces include one ai ...

aircraft were also produced, such as the fighter

IAR-80

The IAR 80 was a Romanian World War II low-wing monoplane, all-metal monocoque fighter and ground-attack aircraft. When it first flew, in 1939, it was comparable to contemporary designs being deployed by the airforces of the most advanced milit ...

and the light bomber

IAR-37

The IAR 37 was a 1930s Romanian reconnaissance or light bomber aircraft built by Industria Aeronautică Română.

Development

The IAR 37 prototype was flown for the first time in 1937 to meet a requirement for a tactical bombing and reconnaissan ...

. The country had

built armored fighting vehicles as well, most notably the

Mareșal tank destroyer, that likely influenced the design of the German

Hetzer. Romania had also been a major power in the oil industry since the 1800s. It was one of the largest producers in Europe and the

Ploiești oil refineries provided about 30% of all Axis oil production. British historian

Dennis Deletant

Dennis Deletant (born 5 March 1946) is a British-Romanian historian of the history of Romania. As of 2019, he is Visiting Ion Rațiu Professor of Romanian Studies at Georgetown University and Emeritus Professor of Romanian Studies at the UCL Sc ...

has asserted that Romania's crucial contributions to the Axis war effort, including having the third largest Axis army in Europe and sustaining the German war effort through oil and other materiel, meant that it was "on a par with Italy as a principal ally of Germany and not in the category of a minor Axis satellite". Another British historian, Mark Axworthy, believes that Romania could even be considered to have had the second most important Axis army of Europe, even more so than that of Italy.

Under Antonescu Romania was a fascist dictatorship and a totalitarian state. Between 45,000 and 60,000 Jews were killed in

Bukovina

Bukovinagerman: Bukowina or ; hu, Bukovina; pl, Bukowina; ro, Bucovina; uk, Буковина, ; see also other languages. is a historical region, variously described as part of either Central or Eastern Europe (or both).Klaus Peter BergerT ...

and

Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Be ...

by Romanian and German troops in 1941. According to Wilhelm Filderman at least 150,000 Jews of

Bessarabia and Bukovina, died under the Antonescu regime (both those deported and those who remained). Overall, approximately 250,000 Jews under Romanian jurisdiction died.

By 1943, the tide began to turn. The Soviets pushed further west, retaking Ukraine and eventually launching an

unsuccessful invasion of eastern Romania in the spring of 1944. Romanian troops in the Crimea

helped repulse initial Soviet landings, but eventually all of the peninsula was re-conquered by Soviet forces and the

Romanian Navy evacuated over 100,000 German and Romanian troops, an achievement which earned Romanian Admiral

Horia Macellariu

Horia Macellariu (10 May 1894, Craiova – 11 July 1989, Bucharest) was a Romanian rear admiral, commander of the Royal Romanian Navy's Black Sea Fleet during the Second World War.

Early life

Horia Ion Pompiliu Macellariu was born in Craiova o ...

the

Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (german: Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes), or simply the Knight's Cross (), and its variants, were the highest awards in the military and paramilitary forces of Nazi Germany during World War II.

The Knight' ...

. During the

Jassy-Kishinev Offensive of August 1944, Romania

switched sides on August 23, 1944. Romanian troops then fought alongside the Soviet Army until the end of the war, reaching as far as Czechoslovakia and Austria.

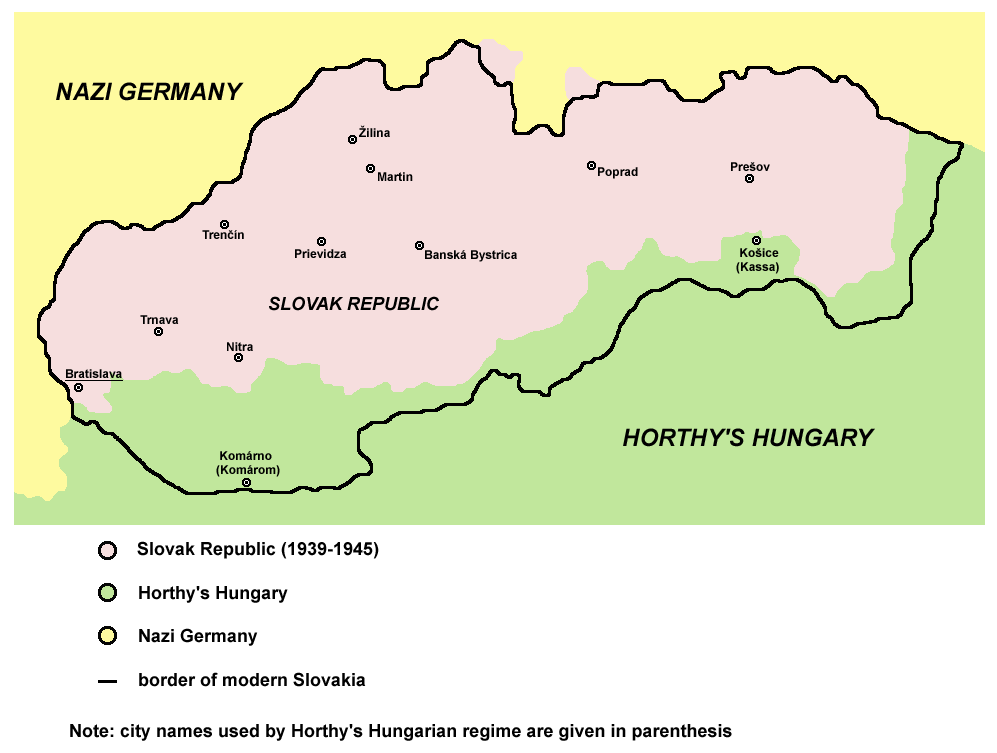

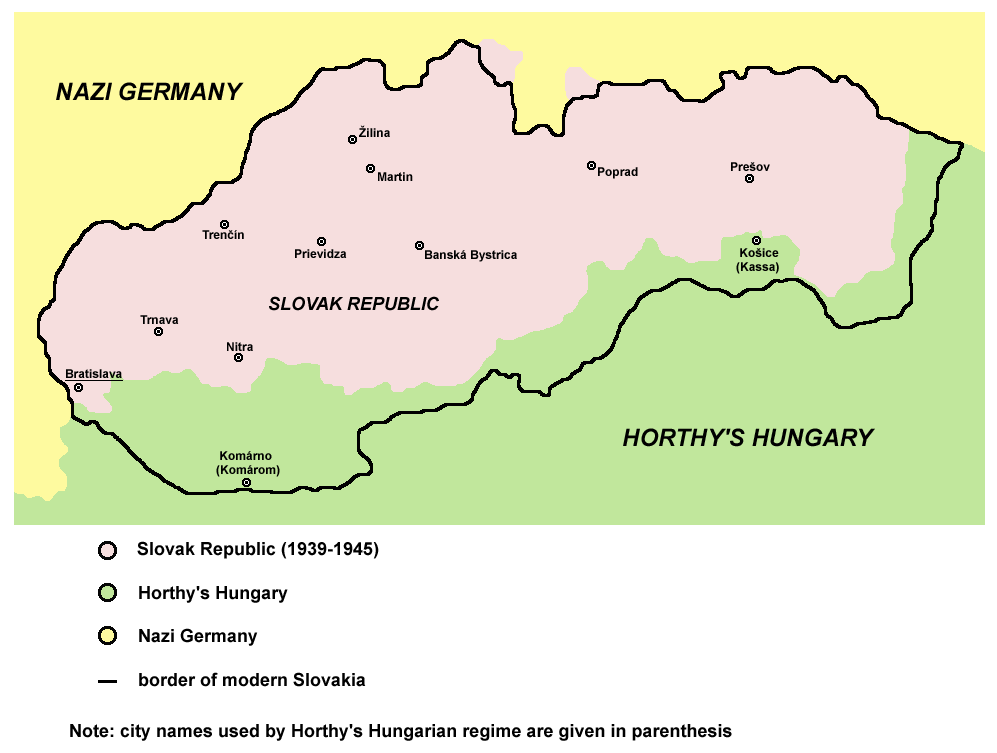

Slovakia

The

Slovak Republic

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

under President

Josef Tiso signed the Tripartite Pact on 24 November 1940.

Slovakia had been closely aligned with Germany almost immediately from its declaration of independence from Czechoslovakia on 14 March 1939. Slovakia entered into a treaty of protection with Germany on 23 March 1939.

Slovak troops joined the German invasion of Poland, having interest in

Spiš and

Orava. Those two regions, along with

Cieszyn Silesia, had been

disputed

Controversy is a state of prolonged public dispute or debate, usually concerning a matter of conflicting opinion or point of view. The word was coined from the Latin ''controversia'', as a composite of ''controversus'' – "turned in an opposite d ...

between Poland and Czechoslovakia since 1918. The Poles fully annexed them following the

Munich Agreement. After the invasion of Poland, Slovakia reclaimed control of those territories.

Slovakia invaded Poland alongside German forces, contributing 50,000 men at this stage of the war.

Slovakia declared war on the Soviet Union in 1941 and signed the revived Anti-Comintern Pact in 1941. Slovak troops fought on Germany's Eastern Front, furnishing Germany with two divisions totaling 80,000 men. Slovakia declared war on the United Kingdom and the United States in 1942.

Slovakia was spared German military occupation until the

Slovak National Uprising, which began on 29 August 1944, and was almost immediately crushed by the Waffen SS and Slovak troops loyal to Josef Tiso.

After the war, Tiso was executed and Slovakia once again became part of Czechoslovakia. The border with Poland was shifted back to the pre-war state. Slovakia and the Czech Republic finally separated into independent states in 1993.

Yugoslavia (two-day membership)

Yugoslavia was largely surrounded by members of the pact and now bordered the German Reich. From late 1940 Hitler sought a non-aggression pact with Yugoslavia. In February 1941, Hitler called for Yugoslavia's accession to the Tripartite Pact, but the Yugoslav government delayed. In March, divisions of the German army arrived at the Bulgarian-Yugoslav border and permission was sought for them to pass through to attack Greece. On 25 March 1941, fearing that Yugoslavia would be invaded otherwise, the Yugoslav government signed the Tripartite Pact with significant reservations. Unlike other Axis powers, Yugoslavia was not obliged to provide military assistance, nor to provide its territory for Axis to move military forces during the war. Less than two days later, after demonstrations in the streets of Belgrade,

Prince Paul and the government were removed from office by a

coup d'état. Seventeen-year-old

King Peter was declared to be of age. The new Yugoslav government under General

Dušan Simović, refused to ratify Yugoslavia's signing of the Tripartite Pact, and started negotiations with Great Britain and Soviet Union. Winston Churchill commented that "Yugoslavia has found its soul"; however, Hitler invaded and quickly took control.

Anti-Comintern Pact signatories

Some countries signed the Anti-Comintern Pact but not the Tripartite Pact. As such their adherence to the Axis may have been less than that of Tripartite Pact signatories. Some of these states were officially at war with members of the Allied powers, others remained neutral in the war and sent only volunteers. Signing the Anti-Comintern Pact was seen as "a

litmus test

Litmus test may refer to:

* Litmus test (chemistry), used to determine the acidity of a chemical solution

* Litmus test (politics), a question that seeks to find the character of a potential candidate by measuring a single indicator

* Litmus Test ...

of loyalty" by the Nazi leadership.

China (Reorganized National Government of China)

During the

Second Sino-Japanese War, Japan advanced from its bases in Manchuria to occupy much of East and Central China. Several Japanese puppet states were organized in areas occupied by the

Imperial Japanese Armed Forces, including the

Provisional Government of the Republic of China at

Beijing, which was formed in 1937, and the

Reformed Government of the Republic of China

The Reformed Government of the Republic of China was a Chinese puppet state created by Japan that existed from 1938 to 1940 during the Second Sino-Japanese War. The regime had little authority or popular support, nor did it receive international ...

at Nanjing, which was formed in 1938. These governments were merged into the

Reorganized National Government of China at Nanjing on 29 March 1940.

Wang Jingwei became head of state. The government was to be run along the same lines as the Nationalist regime and adopted its symbols.

The Nanjing Government had no real power; its main role was to act as a propaganda tool for the Japanese. The Nanjing Government concluded agreements with Japan and Manchukuo, authorising Japanese occupation of China and recognising the independence of Manchukuo under Japanese protection. The Nanjing Government signed the Anti-Comintern Pact of 1941 and declared war on the United States and the United Kingdom on 9 January 1943.

The government had a strained relationship with the Japanese from the beginning. Wang's insistence on his regime being the true Nationalist government of China and in replicating all the symbols of the

Kuomintang led to frequent conflicts with the Japanese, the most prominent being the issue of the regime's flag, which was identical to that of the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

.

The worsening situation for Japan from 1943 onwards meant that the Nanking Army was given a more substantial role in the defence of occupied China than the Japanese had initially envisaged. The army was almost continuously employed against the communist

New Fourth Army. Wang Jingwei died on 10 November 1944, and was succeeded by his deputy,

Chen Gongbo

Chen Gongbo (; Japanese: ''Chin Kōhaku''; October 19, 1892 – June 3, 1946) was a Chinese politician, noted for his role as second (and final) President of the collaborationist Wang Jingwei regime during World War II.

Biography

Chen Gongbo w ...

. Chen had little influence; the real power behind the regime was

Zhou Fohai, the mayor of Shanghai. Wang's death dispelled what little legitimacy the regime had. On 9 September 1945, following the defeat of Japan, the area was surrendered to General

He Yingqin, a nationalist general loyal to

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

. Chen Gongbo was tried and executed in 1946.

Denmark

Denmark was occupied by Germany after April 1940 and never joined the Axis. On 31 May 1939, Denmark and Germany signed a treaty of non-aggression, which did not contain any military obligations for either party. On April 9, Germany

attacked Scandinavia, and the speed of the

German invasion of Denmark prevented King

Christian X and the Danish government from going into exile. They had to accept "protection by the Reich" and the stationing of German forces in exchange for nominal independence. Denmark coordinated its foreign policy with Germany, extending diplomatic recognition to Axis collaborator and puppet regimes, and breaking diplomatic relations with the Allied governments-in-exile. Denmark broke diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and signed the Anti-Comintern Pact in 1941.

However the United States and Britain ignored Denmark and worked with

Henrik Kauffmann Denmark's ambassador in the US when it came to dealings about using

Iceland,

Greenland, and the Danish merchant fleet against Germany.

In 1941 Danish Nazis set up the ''

Frikorps Danmark

Free Corps Denmark ( da, Frikorps Danmark) was a unit of the Waffen-SS during World War II consisting of collaborationist volunteers from Denmark. It was established following an initiative by the National Socialist Workers' Party of Denmark (DNS ...

''. Thousands of volunteers fought and many died as part of the German Army on the Eastern Front. Denmark sold agricultural and industrial products to Germany and made loans for armaments and fortifications. The German presence in Denmark included the construction of part of the

Atlantic Wall

The Atlantic Wall (german: link=no, Atlantikwall) was an extensive system of coastal defences and fortifications built by Nazi Germany between 1942 and 1944 along the coast of continental Europe and Scandinavia as a defence against an anticip ...

fortifications which Denmark paid for and was never reimbursed.

The Danish protectorate government lasted until 29 August 1943, when the cabinet resigned after the

regularly scheduled and largely free election concluding the

Folketing's current term. The Germans imposed

martial law following

Operation Safari

Operation Safari (german: Unternehmen Safari) was a German military operation during World War II aimed at disarming the Danish military. It led to the scuttling of the Royal Danish Navy and the internment of all Danish soldiers. Danish forces su ...

, and Danish collaboration continued on an administrative level, with the Danish bureaucracy functioning under German command. The

Royal Danish Navy scuttled 32 of its larger ships; Germany seized 64 ships and later raised and refitted 15 of the sunken vessels. 13 warships escaped to Sweden and formed a Danish naval flotilla in exile. Sweden allowed formation of a

Danish military brigade in exile; it did not see combat. The

Danish resistance movement

The Danish resistance movements ( da, Den danske modstandsbevægelse) were an underground insurgency to resist the German occupation of Denmark during World War II. Due to the initially lenient arrangements, in which the Nazi occupation autho ...

was active in sabotage and issuing underground newspapers and blacklists of collaborators.

Finland

Although Finland never signed the Tripartite Pact, it fought against the Soviet Union alongside Germany in the 1941-44

Continuation War, during which the official position of the wartime Finnish government was that Finland was a co-belligerent of the Germans whom they described as "brothers-in-arms". Finland did sign the revived Anti-Comintern Pact of November 1941. Finland signed a

peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice, which is an agreement to stop hostilities; a surr ...

with the Allied powers in 1947 which described Finland as having been "an ally of Hitlerite Germany" during the continuation war. As such, Finland was the only democracy to join the Axis.

Finland's relative independence from Germany put it in the most advantageous position of all the minor Axis powers.

Whilst Finland's relationship with Nazi Germany during the Continuation War remains controversial within Finland,

in a 2008 ''

Helsingin Sanomat

''Helsingin Sanomat'', abbreviated ''HS'' and colloquially known as , is the largest subscription newspaper in Finland and the Nordic countries, owned by Sanoma. Except after certain holidays, it is published daily. Its name derives from that of ...

'' survey of 28 Finnish historians 16 agreed that Finland had been an ally of Nazi Germany, with only six disagreeing.

The August 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union contained a secret protocol dividing much of eastern Europe and assigning Finland to the Soviet sphere of influence. After unsuccessfully attempting to force territorial and other concessions on the Finns, the Soviet Union tried to invade Finland in November 1939 during the

Winter War, intending to establish a communist puppet government in Finland. The conflict threatened

Germany's iron-ore supplies and offered the prospect of Allied interference in the region. Despite Finnish resistance, a peace treaty was signed in March 1940, wherein Finland ceded some key territory to the Soviet Union, including the

Karelian Isthmus, containing Finland's second-largest city,

Viipuri, and the critical defensive structure of the

Mannerheim Line

The Mannerheim Line ( fi, Mannerheim-linja, sv, Mannerheimlinjen) was a defensive fortification line on the Karelian Isthmus built by Finland against the Soviet Union. While this was never an officially designated name, during the Winter War it ...

. After this war, Finland sought protection and support from the United Kingdom

[British Foreign Office Archive, 371/24809/461-556.] and non-aligned Sweden, but was thwarted by Soviet and German actions. This resulted in Finland being drawn closer to Germany, first with the intent of enlisting German support as a counterweight to thwart continuing Soviet pressure, and later to help regain lost territories.

In the opening days of Operation Barbarossa, Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union, Finland permitted German planes returning from mine dropping runs over

Kronstadt and

Neva River

The Neva (russian: Нева́, ) is a river in northwestern Russia flowing from Lake Ladoga through the western part of Leningrad Oblast (historical region of Ingria) to the Neva Bay of the Gulf of Finland. Despite its modest length of , it i ...

to refuel at Finnish airfields before returning to bases in

East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label=Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

. In retaliation, the Soviet Union launched a major air offensive against

Finnish Air Force bases and towns, which resulted in a Finnish declaration of war against the Soviet Union on 25 June 1941. The Finnish conflict with the Soviet Union is generally referred to as the

Continuation War.

Finland's main objective was to regain territory lost to the Soviet Union in the Winter War. However, on 10 July 1941, Field Marshal

Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim

Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (, ; 4 June 1867 – 27 January 1951) was a Finnish military leader and statesman. He served as the military leader of the Whites in the Finnish Civil War of 1918, as Regent of Finland (1918–1919), as comma ...

issued an

Order of the Day

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches, MiD) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face ...

that contained a formulation understood internationally as a Finnish territorial interest in Russian

Karelia

Karelia ( Karelian and fi, Karjala, ; rus, Каре́лия, links=y, r=Karélija, p=kɐˈrʲelʲɪjə, historically ''Korjela''; sv, Karelen), the land of the Karelian people, is an area in Northern Europe of historical significance for ...

.

Diplomatic relations between the United Kingdom and Finland were severed on 1 August 1941, after the British

Royal Air Force bombed German forces in the Finnish village and port of

Petsamo Petsamo may refer to:

* Petsamo Province, a province of Finland from 1921 to 1922

* Petsamo, Tampere, a district in Tampere, Finland

* Pechengsky District, Russia, formerly known as Petsamo

* Pechenga (urban-type settlement), Murmansk Oblast, Russi ...

. The United Kingdom repeatedly called on Finland to cease its offensive against the Soviet Union, and declared war on Finland on 6 December 1941, although no other military operations followed. War was never declared between Finland and the United States, though relations were severed between the two countries in 1944 as a result of the

Ryti-Ribbentrop Agreement.

Finland maintained command of

its armed forces and pursued war objectives independently of Germany. Germans and Finns did work closely together during

Operation Silver Fox, a joint offensive against Murmansk. Finland took part in the

Siege of Leningrad

The siege of Leningrad (russian: links=no, translit=Blokada Leningrada, Блокада Ленинграда; german: links=no, Leningrader Blockade; ) was a prolonged military blockade undertaken by the Axis powers against the Soviet city of L ...

. Finland was one of Germany's most important allies in its war with the USSR.

The relationship between Finland and Germany was also affected by the

Ryti-Ribbentrop Agreement, which was presented as a German condition for help with munitions and air support, as the

Soviet offensive coordinated with D-Day threatened Finland with complete occupation. The agreement, signed by President

Risto Ryti but never ratified by the Finnish Parliament, bound Finland not to seek a separate peace.

After Soviet offensives were fought to a standstill, Ryti's successor as president, Marshal

Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim

Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (, ; 4 June 1867 – 27 January 1951) was a Finnish military leader and statesman. He served as the military leader of the Whites in the Finnish Civil War of 1918, as Regent of Finland (1918–1919), as comma ...

, dismissed the agreement and opened secret negotiations with the Soviets, which resulted in a ceasefire on 4 September and the

Moscow Armistice on 19 September 1944. Under the terms of the armistice, Finland was obliged to expel German troops from Finnish territory, which resulted in the

Lapland War.

Manchuria (Manchukuo)

Manchukuo, in the

northeast region of China, had been a Japanese puppet state in

Manchuria since the 1930s. It was nominally ruled by

Puyi, the last

Chinese Emperor

''Huangdi'' (), translated into English as Emperor, was the superlative title held by monarchs of China who ruled various imperial regimes in Chinese history. In traditional Chinese political theory, the emperor was considered the Son of Heaven ...

of the

Qing Dynasty, but was in fact controlled by the Japanese military, in particular the

Kwantung Army. While Manchukuo ostensibly was a state for ethnic

Manchus, the region had a

Han Chinese majority.

Following the

Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, the independence of Manchukuo was proclaimed on 18 February 1932, with Puyi as head of state. He was proclaimed the Emperor of Manchukuo a year later. The new Manchu nation was recognized by 23 of the

League of Nations' 80 members. Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union were among the major powers who recognised Manchukuo. Other countries who recognized the State were the

Dominican Republic,

Costa Rica

Costa Rica (, ; ; literally "Rich Coast"), officially the Republic of Costa Rica ( es, República de Costa Rica), is a country in the Central American region of North America, bordered by Nicaragua to the north, the Caribbean Sea to the no ...

,

El Salvador

El Salvador (; , meaning " The Saviour"), officially the Republic of El Salvador ( es, República de El Salvador), is a country in Central America. It is bordered on the northeast by Honduras, on the northwest by Guatemala, and on the south b ...

, and

Vatican City. Manchukuo was also recognised by the other Japanese allies and puppet states, including Mengjiang, the Burmese government of

Ba Maw,

Thailand, the Wang Jingwei regime, and the Indian government of

Subhas Chandra Bose

Subhas Chandra Bose ( ; 23 January 1897 – 18 August 1945

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*) was an Indian nationalist whose defiance of British authority in India made him a hero among Indians, but his wartime alliances with Nazi Germany and Imperia ...

. The League of Nations later declared in 1934 that Manchuria lawfully remained a part of China. This precipitated Japanese withdrawal from the League. The Manchukuoan state ceased to exist after the

Soviet invasion of Manchuria in 1945.

Manchukuo signed the Anti-Comintern Pact in 1939, but never signed the Tripartite Pact.

Spain

''Caudillo'' Francisco Franco's

''Caudillo'' Francisco Franco's Spanish State

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spani ...

gave moral, economic, and military assistance to the Axis powers, while nominally maintaining neutrality. Franco described Spain as a member of the Axis and signed the

Anti-Comintern Pact in 1941 with Hitler and Mussolini. Members of the ruling

Falange party in Spain held irredentist designs on

Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

. Falangists also supported Spanish colonial acquisition of the

Tangier International Zone,

French Morocco

The French protectorate in Morocco (french: Protectorat français au Maroc; ar, الحماية الفرنسية في المغرب), also known as French Morocco, was the period of French colonial rule in Morocco between 1912 to 1956. The prote ...

and northwestern

French Algeria

French Algeria (french: Alger to 1839, then afterwards; unofficially , ar, الجزائر المستعمرة), also known as Colonial Algeria, was the period of French colonisation of Algeria. French rule in the region began in 1830 with the ...

. In addition, Spain held ambitions on former

Spanish colonies in Latin America. In June 1940 the Spanish government approached Germany to propose an alliance in exchange for Germany recognizing Spain's territorial aims: the annexation of the

Oran Province of

Algeria, the incorporation of all

Morocco, the extension of

Spanish Sahara southward to the twentieth parallel, and the incorporation of

French Cameroons into

Spanish Guinea. Spain invaded and occupied the Tangier International Zone, maintaining its occupation until 1945. The occupation caused a dispute between Britain and Spain in November 1940; Spain conceded to protect British rights in the area and promised not to fortify the area. The Spanish government secretly held expansionist plans towards Portugal that it made known to the German government. In a communiqué with Germany on 26 May 1942, Franco declared that Portugal should be annexed into Spain.

Franco had previously won the

Spanish Civil War with the help of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Both were eager to establish another fascist state in Europe. Spain owed Germany over $212 million for supplies of

matériel

Materiel (; ) refers to supplies, equipment, and weapons in military supply-chain management, and typically supplies and equipment in a commercial supply chain context.

In a military context, the term ''materiel'' refers either to the specific ...

during the Spanish Civil War, and Italian

Corpo Truppe Volontarie

The Corps of Volunteer Troops ( it, Corpo Truppe Volontarie, CTV) was a Fascist Italian expeditionary force of military volunteers, which was sent to Spain to support the Nationalist forces under General Francisco Franco against the Spanish R ...

combat troops had actually fought in Spain on the side of Franco's Nationalists.

When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Franco immediately offered to form a unit of military volunteers to join the invasion. This was accepted by Hitler and, within two weeks, there were more than enough volunteers to form a division – the

Blue Division (''División Azul'') under General

Agustín Muñoz Grandes

Agustín Muñoz Grandes (27 January 1896 – 11 July 1970) was a Spanish general, and politician, vice-president of the Spanish Government and minister with Francisco Franco several times; also known as the commander of the Blue Division between ...

.

The possibility of Spanish intervention in World War II was of concern to the United States, which investigated the activities of Spain's ruling

Falange Espanola Tradicionalista y de las JONS

The Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS; ), frequently shortened to just "FET", was the sole legal party of the Francoist regime in Spain. It was created by General Francisco F ...

in

Latin America, especially

Puerto Rico, where pro-Falange and pro-Franco sentiment was high, even amongst the ruling upper classes. The Falangists promoted the idea of supporting Spain's former colonies in fighting against American domination. Prior to the outbreak of war, support for Franco and the Falange was high in the Philippines. The

Falange Exterior, the international department of the Falange, collaborated with Japanese forces against the

United States Armed Forces and the

Philippine Commonwealth Army in the

Philippines through the

Philippine Falange.

Bilateral Pacts with the Axis Powers

Some countries colluded with Germany, Italy, and Japan without signing either the Anti-Comintern Pact, or the Tripartite Pact. In some cases these bilateral agreements were formalised, in other cases it was less formal. Some of these countries were puppet states established by the Axis Powers themselves.

Burma (Ba Maw government)

The Japanese Army and Burma nationalists, led by

Aung San, seized control of Burma from the United Kingdom during 1942. A

State of Burma was formed on 1 August 1943 under the Burmese nationalist leader

Ba Maw. A treaty of alliance was concluded between the Ba Maw regime and Japan was signed by Ba Maw for Burma and Sawada Renzo for Japan on the same day in which the Ba Maw government pledged itself to provide the Japanese "with every necessary assistance in order to execute a successful military operation in Burma". The Ba Maw government mobilised Burmese society during the war to support the Axis war-effort.

The Ba Maw regime established the Burma Defence Army (later renamed the

Burma National Army), which was commanded by

Aung San which fought alongside the Japanese in the

Burma campaign. The Ba Maw has been described as a state having "independence without sovereignty" and as being effectively a Japanese puppet state.

On 27 March 1945 the Burma National Army revolted against the Japanese.

Thailand

As an ally of Japan during the war that deployed troops to fight on the Japanese side against Allied forces,

Thailand is considered to have been part of the Axis alliance,

or at least "aligned with the Axis powers".

For example, writing in 1945, the American politician

Clare Boothe Luce described Thailand as "undeniably an Axis country" during the war.

waged the

Franco-Thai War in October 1940 to May 1941 to reclaim territory from

French Indochina.

Japanese forces invaded Thailand an hour and a half before the

attack on Pearl Harbor (because of the International Dateline, the local time was on the morning of 8 December 1941). Only hours after the invasion, Prime Minister Field Marshal

Phibunsongkhram

Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram ( th, แปลก พิบูลสงคราม ; alternatively transcribed as ''Pibulsongkram'' or ''Pibulsonggram''; 14 July 1897 – 11 June 1964), locally known as Marshal P. ( th, จอมพล � ...

ordered the cessation of resistance against the Japanese. An outline plan of Japan-Thailand joint military operations, whereby Thai forces would invade Burma to defend the right flank of Japanese forces, was agreed on 14 December 1941.

On 21 December 1941, a military alliance with Japan was signed and on 25 January 1942,

Sang Phathanothai

Sang Phathanothai ( th, สังข์ พัธโนทัย; 1915 – June, 1986) was a Thai politician, union leader, and journalist. He was one of the closest advisors to Field Marshal Phibunsongkhram.

In his early 20s Sang began to ...

read over the radio Thailand's formal declaration of war on the United Kingdom and the United States. The Thai ambassador to the United States,

Mom Rajawongse Seni Pramoj

Mom Rajawongse Seni Pramoj ( th, หม่อมราชวงศ์เสนีย์ ปราโมช, , ; 26 May 190528 July 1997) was three times the Prime Minister of Thailand, a politician in the Democrat Party, lawyer, diplomat and pr ...

, did not deliver his copy of the declaration of war. Therefore, although the British reciprocated by declaring war on Thailand and considered it a hostile country, the United States did not.

The Thais and Japanese agreed that the Burmese

Shan State and

Karenni State were to be under Thai control. The rest of Burma was to be under Japanese control. On 10 May 1942, the Thai

Phayap Army

Phayap Army ( th, กองทัพพายัพ RTGS: Thap Phayap or Payap, ''northwest'') was the Thai force that invaded the Siamese Shan States (present day Shan State, Myanmar) of Burma on 10 May 1942 during the Burma Campaign of World ...

entered Burma's eastern Shan State, which had been claimed by Siamese kingdoms. Three Thai infantry and one cavalry division, spearheaded by armoured reconnaissance groups and supported by the air force, engaged the retreating Chinese 93rd Division.

Kengtung, the main objective, was captured on 27 May. Renewed offensives in June and November saw the Chinese retreat into

Yunnan.

In November 1943 Thailand signed the Greater East Asia Joint Declaration, formally aligning itself with the Axis Powers. The area containing the

Shan States and

Kayah State was annexed by Thailand in 1942, and four northern states of

Malaya

Malaya refers to a number of historical and current political entities related to what is currently Peninsular Malaysia in Southeast Asia:

Political entities

* British Malaya (1826–1957), a loose collection of the British colony of the Straits ...

were also transferred to Thailand by Japan as a reward for Thai co-operation. These areas were ceded back to

Burma and Malaya in 1945.

Thai military losses totalled 5,559 men during the war, of whom about 180 died resisting the Japanese invasion of 8 December 1941, roughly 150 died in action during the fighting in the Shan States, and the rest died of malaria and other diseases.

The

Free Thai Movement ("Seri Thai") was established during these first few months. Parallel Free Thai organizations were also established in the United Kingdom.

The king's aunt, Queen

Rambai Barni

Queen Rambai Barni ( th, รำไพพรรณี, , ), formerly Princess Rambai Barni Svastivatana ( th, รำไพพรรณี สวัสดิวัตน์, ; born 20 December 1904 – 22 May 1984), was the wife and queen con ...

, was the nominal head of the British-based organization, and

Pridi Banomyong, the regent, headed its largest contingent, which was operating within Thailand. Aided by elements of the military, secret airfields and training camps were established, while American

Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branc ...

and British

Force 136

Force 136 was a far eastern branch of the British World War II intelligence organisation, the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Originally set up in 1941 as the India Mission with the cover name of GSI(k), it absorbed what was left of SOE's Or ...

agents slipped in and out of the country.

As the war dragged on, the Thai population came to resent the Japanese presence. In June 1944, Phibun was overthrown in a coup d'état. The new civilian government under

Khuang Aphaiwong

Khuang Aphaiwong (also spelled ''Kuang'', ''Abhaiwong'', or ''Abhaiwongse''; th, ควง อภัยวงศ์, ; 17 May 1902 – 15 March 1968), also known by his noble title Luang Kowit-aphaiwong ( th, หลวงโกวิทอ� ...

attempted to aid the resistance while maintaining cordial relations with the Japanese. After the war, U.S. influence prevented Thailand from being treated as an Axis country, but the British demanded three million tons of rice as reparations and the return of areas annexed from

Malaya

Malaya refers to a number of historical and current political entities related to what is currently Peninsular Malaysia in Southeast Asia:

Political entities

* British Malaya (1826–1957), a loose collection of the British colony of the Straits ...

during the war. Thailand also returned the portions of

British Burma

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and French Indochina that had been annexed. Phibun and a number of his associates were put on trial on charges of having committed war crimes and of collaborating with the Axis powers. However, the charges were dropped due to intense public pressure. Public opinion was favourable to Phibun, as he was thought to have done his best to protect Thai interests.

Soviet Union

In 1939 the Soviet Union considered forming an alliance with either

Britain and France or with Germany. When negotiations with Britain and France failed, they turned to Germany and signed the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in August 1939. Germany was now freed from the risk of war with the Soviets, and was assured a supply of oil. This included a secret protocol whereby territories controlled by

Poland, Finland,

Estonia,

Romania,

Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

and

Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

were divided into

spheres of interest of the parties. The Soviet Union sought to re-annex some of territories that were under control of those states, formerly acquired by the

Russian Empire in the centuries prior and lost to Russia in the

aftermath of World War I

The aftermath of World War I saw drastic political, cultural, economic, and social change across Eurasia, Africa, and even in areas outside those that were directly involved. Four empires collapsed due to the war, old countries were abolished, ne ...

; that included land such as the

Kresy (Western

Belarus and Western Ukraine) region ceded to Poland after losing the

Soviet-Polish War of 1919–1921.

On 1 September, barely a week after the pact had been signed,

Germany invaded Poland. The Soviet Union

invaded Poland from the east on 17 September and on 28 September signed a

secret treaty with Nazi Germany to coordinate fighting against the

Polish resistance. The Soviets targeted intelligence, entrepreneurs and officers with mass arrests, with many victims sent to the

Gulag in Siberia, committing a string of atrocities that culminated in the

Katyn massacre. Soon after the invasion of Poland, the Soviet Union

occupied the Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, and annexed

Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Be ...

and

Northern Bukovina from Romania. The Soviet Union attacked Finland on 30 November 1939, which started the

Winter War. Finnish defenses prevented an all-out invasion, resulting in an

interim peace, but Finland was forced to cede strategically important border areas near

Leningrad.

The Soviet Union provided material support to Germany in the war effort against Western Europe through a pair of commercial agreements,

the first The First may refer to:

* ''The First'' (album), the first Japanese studio album by South Korean boy group Shinee

* ''The First'' (musical), a musical with a book by critic Joel Siegel

* The First (TV channel), an American conservative opinion ne ...

in 1939 and

the second in 1940, which involved exports of raw materials (

phosphates,

chromium

Chromium is a chemical element with the symbol Cr and atomic number 24. It is the first element in group 6. It is a steely-grey, lustrous, hard, and brittle transition metal.

Chromium metal is valued for its high corrosion resistance and hardne ...

and

iron ore

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the fo ...

,

mineral oil, grain, cotton, and rubber). These and other export goods transported through Soviet and occupied Polish territories allowed Germany to circumvent the British naval blockade. In October and November 1940,

German–Soviet talks about the potential of joining the Axis took place in Berlin.

Joseph Stalin later personally countered with a separate proposal in a letter on 25 November that contained several secret protocols, including that "the area south of

Batum and

Baku

Baku (, ; az, Bakı ) is the capital and largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and of the Caucasus region. Baku is located below sea level, which makes it the lowest lying national capital in the world a ...

in the general direction of the

Persian Gulf is recognized as the center of aspirations of the Soviet Union", referring to an area approximating present day Iraq and Iran, and a Soviet claim to Bulgaria. Hitler never responded to Stalin's letter. Shortly thereafter, Hitler issued a secret directive on

the invasion of the Soviet Union. Reasons included the Nazi ideologies of

Lebensraum and

Heim ins Reich

The ''Heim ins Reich'' (; meaning "back home to the Reich") was a foreign policy pursued by Adolf Hitler before and during World War II, beginning in 1938. The aim of Hitler's initiative was to convince all ''Volksdeutsche'' (ethnic Germans) wh ...

Vichy France

The German army entered Paris on 14 June 1940, following the

battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

. Pétain became the last

Prime Minister of the French Third Republic on 16 June 1940. He sued for peace with Germany and on 22 June 1940, the French government

concluded an armistice with Hitler and Mussolini, which came into effect at midnight on 25 June. Under the terms of the agreement, Germany

occupied two-thirds of France, including Paris. Pétain was permitted to keep an "

armistice army

The Armistice Army or Vichy French Army (french: Armée de l'Armistice) was the common name for the armed forces of Vichy France permitted under the Armistice of 22 June 1940 after the French capitulation to Nazi Germany and Italy. It was off ...

" of 100,000 men within the

unoccupied southern zone. This number included neither the army based in the

French colonial empire

The French colonial empire () comprised the overseas colonies, protectorates and mandate territories that came under French rule from the 16th century onward. A distinction is generally made between the "First French Colonial Empire", that exist ...

nor the

French Navy. In Africa the Vichy regime was permitted to maintain 127,000. The French also maintained substantial garrisons at the French-mandate territory of

Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

and

Greater Lebanon, the

French colony of Madagascar, and in

French Somaliland

French Somaliland (french: Côte française des Somalis, lit= French Coast of the Somalis so, Xeebta Soomaaliyeed ee Faransiiska) was a French colony in the Horn of Africa. It existed between 1884 and 1967, at which time it became the French Ter ...

. Some members of the Vichy government pushed for closer cooperation, but they were rebuffed by Pétain. Neither did Hitler accept that France could ever become a full military partner, and constantly prevented the buildup of Vichy's military strength.

After the armistice, relations between the Vichy French and the British quickly worsened. Although the French had told Churchill they would not allow their fleet to be taken by the Germans, the British launched naval attacks intended to prevent the French navy being used, the most notable of which was

the attack on the Algerian harbour of Mers el-Kebir on 3 July 1940. Though Churchill defended his controversial decision to attack the French fleet, the action deteriorated greatly the relations between France and Britain.

German propaganda trumpeted these attacks as an absolute betrayal of the French people by their former allies.

On 10 July 1940, Pétain was given emergency "full powers" by a majority vote of the

French National Assembly

The National Assembly (french: link=no, italics=set, Assemblée nationale; ) is the lower house of the bicameral French Parliament under the Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are known a ...

. The following day approval of the new constitution by the Assembly effectively created the

French State

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

(''l'État Français''), replacing the French Republic with the government unofficially called "Vichy France," after the resort town of

Vichy, where Pétain maintained his seat of government. This continued to be recognised as the lawful government of France by the neutral United States until 1942, while the United Kingdom had recognised

de Gaulle's government-in-exile in London. Racial laws were introduced in France and its colonies and many

foreign Jews in France were deported to Germany.

Albert Lebrun, last President of the Republic, did not resign from the presidential office when he moved to

Vizille

Vizille (; frp, Veselye) is a commune in the Isère department in southeastern France.

Population

Sights

Vizille is the home of the Musée de la Révolution française, a rich depository of archival and rare materials devoted to the French ...

on 10 July 1940. By 25 April 1945, during Pétain's trial, Lebrun argued that he thought he would be able to return to power after the fall of Germany, since he had not resigned.

In September 1940, Vichy France was forced to allow

Japan to occupy French Indochina, a federation of French colonial possessions and protectorates encompassing modern day Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. The Vichy regime continued to administer them under Japanese military occupation.

French Indochina was the base for the Japanese

invasions of Thailand

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

,

Malaya

Malaya refers to a number of historical and current political entities related to what is currently Peninsular Malaysia in Southeast Asia:

Political entities

* British Malaya (1826–1957), a loose collection of the British colony of the Straits ...

, and

the Dutch East Indies. On 26 September 1940, de Gaulle

led an attack by Allied forces on the Vichy port of Dakar in

French West Africa

French West Africa (french: Afrique-Occidentale française, ) was a federation of eight French colonial territories in West Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guinea (now Guinea), Ivory Coast, Upper Volta (now Burki ...

. Forces loyal to Pétain fired on de Gaulle and repulsed the attack after two days of heavy fighting, drawing Vichy France closer to Germany.

During the

Anglo-Iraqi War of May 1941, Vichy France allowed Germany and Italy to use air bases in the

French mandate of Syria

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (french: Mandat pour la Syrie et le Liban; ar, الانتداب الفرنسي على سوريا ولبنان, al-intidāb al-fransi 'ala suriya wa-lubnān) (1923−1946) was a League of Nations mandate foun ...

to support the Iraqi revolt. British and Free French forces attacked later

Syria and Lebanon in June–July 1941, and in 1942 Allied forces

took over French Madagascar. More and more colonies abandoned Vichy, joining the Free French territories of

French Equatorial Africa,

Polynesia,

New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

and others who had sided with de Gaulle

from the start.

In November 1942 Vichy French troops briefly resisted the

landing of Allied troops in French North Africa for two days, until Admiral

François Darlan negotiated a local ceasefire with the Allies. In response to the landings,

German and Italian forces invaded the non-occupied zone in southern France and ended Vichy France as an entity with any kind of autonomy; it then became a puppet government for the occupied territories. In June 1943, the formerly Vichy-loyal colonial authorities in

French North Africa led by

Henri Giraud came to an agreement with the

Free French to merge with their own interim regime with the

French National Committee (''Comité Français National'', CFN) to form a

provisional government in

Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

, known as the

French Committee of National Liberation (''Comité Français de Libération Nationale'', CFLN) initially led by Darlan.

In 1943 the

Milice, a paramilitary force which had been founded by Vichy, was subordinated to the Germans and assisted them in rounding up opponents and Jews, as well as fighting the

French Resistance. The Germans recruited volunteers in units independent of Vichy. Partly as a result of the great animosity of many right-wingers against the pre-war

Front Populaire, volunteers joined the German forces in their anti-communist crusade against the USSR. Almost 7,000 joined ''

Légion des Volontaires Français

The Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism (french: Légion des volontaires français contre le bolchévisme, LVF) was a unit of the German Army during World War II consisting of collaborationist volunteers from France. Officially desi ...

'' (LVF) from 1941 to 1944. The LVF then formed the cadre of the

Waffen-SS Division ''Charlemagne'' in 1944–1945, with a maximum strength of some 7,500. Both the LVF and the ''Division Charlemagne'' fought on the eastern front.

Deprived of any military assets, territory or resources, the members of the Vichy government continued to fulfil their role as German puppets, being quasi-prisoners in the so-called "

Sigmaringen enclave" in a castle in

Baden-Württemberg at the end of the war in May 1945.

Iraq

In April 1941 the

Arab nationalist

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language an ...

Rashīd ʿAlī al-Gaylānī, who was pro-Axis,

seized power in Iraq. British forces responded by deploying to Iraq and in turn removing Rashi Ali from power. During fighting between Iraqi and British forces Axis forces were deployed to Iraq to support the Iraqis.

However, Rashid Ali was never able to conclude a formal alliance with the Axis.

Anti-British sentiments were widespread in Iraq prior to 1941.

Rashid Ali al-Gaylani was appointed

Prime Minister of Iraq

The prime minister of Iraq is the head of government of Iraq. On 27 October 2022, Mohammed Shia' Al Sudani became the incumbent prime minister.

History

The prime minister was originally an appointed office, subsidiary to the head of state, a ...

in 1940. When Italy declared war on Britain, Rashid Ali had maintained ties with the Italians. This angered the British government. In December 1940, as relations with the British worsened, Rashid Ali formally requested weapons and military supplies from Germany.

In January 1941 Rashid Ali was forced to resign as a result of British pressure.

In April 1941 Rashid Ali, on seizing power in a coup, repudiated the

Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1930

The Anglo-Iraqi Treaty of 1930 was a treaty of alliance between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the British-Mandate-controlled administration of the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq. The treaty was between the governments ...

and demanded that the British abandon their military bases and withdraw from the country.

On 9 May 1941,

Mohammad Amin al-Husayni

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mono ...

, the

Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

The Grand Mufti of Jerusalem is the Sunni Muslim cleric in charge of Jerusalem's Islamic holy places, including the Al-Aqsa Mosque. The position was created by the British military government led by Ronald Storrs in 1918.See Islamic Leadership i ...

associate of Ali and in asylum in Iraq, declared

holy war against the British and called on Arabs throughout the Middle East to rise up against British rule. On 25 May 1941, the Germans stepped up offensive operations in the Middle East.

Hitler issued

Order 30: "The Arab Freedom Movement in the Middle East is our natural ally against England. In this connection special importance is attached to the liberation of Iraq ... I have therefore decided to move forward in the Middle East by supporting Iraq. "

Hostilities between the Iraqi and British forces began on 2 May 1941, with heavy fighting at

the RAF air base in

Habbaniyah. The Germans and Italians dispatched aircraft and aircrew to Iraq utilizing Vichy French bases in Syria; this led to Australian, British, Indian and Free French forces

entering and conquering Syria in June and July. With the advance of British and Indian forces on Baghdad, Iraqi military resistance ended by 31 May 1941. Rashid Ali and the Mufti of Jerusalem fled to Iran, then Turkey, Italy, and finally Germany, where Ali was welcomed by Hitler as head of the Iraqi

government-in-exile in Berlin.

Puppet states

Various nominally-independent governments formed out of local sympathisers under varying degrees of German, Italian, and Japanese control were established within the territories that they occupied during the war. Some of these governments declared themselves to be neutral in the conflict with the allies, or never concluded any formal alliance with the Axis powers, but their effective control by the Axis powers rendered them in reality an extension of it and hence part of it. These differed from military authorities and civilian commissioners provided by the occupying power in that they were formed from nationals of the occupied country, and that the supposed legitimacy of the puppet state was recognised by the occupier ''de jure'' if not ''de facto''.

German

The collaborationist administrations of

German-occupied countries in Europe had varying degrees of autonomy, and not all of them qualified as fully recognized

sovereign states. The

General Government

The General Government (german: Generalgouvernement, pl, Generalne Gubernatorstwo, uk, Генеральна губернія), also referred to as the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (german: Generalgouvernement für die be ...

in

occupied Poland was a fully German administration. In

occupied Norway, the

National Government A national government is the government of a nation.

National government or

National Government may also refer to:

* Central government in a unitary state, or a country that does not give significant power to regional divisions

* Federal governme ...

headed by

Vidkun Quisling – whose name

came to symbolize pro-Axis collaboration in several languages – was subordinate to the

Reichskommissariat Norwegen. It was never allowed to have any armed forces, be a recognized military partner, or have autonomy of any kind. In

the occupied Netherlands,

Anton Mussert was given the symbolic title of "Führer of the Netherlands' people". His

National Socialist Movement National Socialist Movement may refer to:

* Nazi Party, a political movement in Germany

* National Socialist Movement (UK, 1962), a British neo-Nazi group

* National Socialist Movement (United Kingdom), a British neo-Nazi group active during the lat ...

formed a cabinet assisting the German administration, but was never recognized as a real Dutch government.

Albania (Albanian Kingdom)

After the Italian armistice, a vacuum of power opened up in

Albania. The Italian occupying forces were rendered largely powerless, as the

National Liberation Movement took control of the south and the National Front (

Balli Kombëtar) took control of the north. Albanians in the Italian army joined the guerrilla forces. In September 1943 the guerrillas moved to take the capital of

Tirana, but

German paratroopers dropped into the city. Soon after the battle, the

German High Command announced that they would recognize the independence of a

greater Albania. They organized an Albanian government, police, and military in collaboration with the Balli Kombëtar. The Germans did not exert heavy control over Albania's administration, but instead attempted to gain popular appeal by giving their political partners what they wanted. Several Balli Kombëtar leaders held positions in the regime. The joint forces incorporated Kosovo, western Macedonia, southern Montenegro, and Presevo into the Albanian state. A High Council of Regency was created to carry out the functions of a head of state, while the government was headed mainly by Albanian conservative politicians. Albania was the only European country occupied by the Axis powers that ended World War II with a larger

Jewish population than before the war. The Albanian government had refused to hand over their Jewish population. They provided Jewish families with forged documents and helped them disperse in the Albanian population.

Albania was completely liberated on November 29, 1944.

Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia

The

Government of National Salvation, also referred to as the Nedić regime, was the second Serbian puppet government, after the

Commissioner Government

The Commissioner Government (, ''Komesarska vlada'') was a short-lived Serbian collaborationist puppet government established in the German-occupied territory of Serbia within the Axis-partitioned Kingdom of Yugoslavia during World War II. It o ...

, established on the

Territory of the (German) Military Commander in Serbia, a German occupied territory.

[ Hehn (1971), pp. 344–73], group=nb during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. It was appointed by the German Military Commander in Serbia and operated from 29 August 1941 to October 1944. Although the Serbian puppet regime had some support, it was unpopular with a majority of Serbs who either joined the Yugoslav Partisans or

Draža Mihailović

Dragoljub "Draža" Mihailović ( sr-Cyrl, Драгољуб Дража Михаиловић; 27 April 1893 – 17 July 1946) was a Yugoslavs, Yugoslav Serb general during World War II. He was the leader of the Chetniks, Chetnik Detachments ...

's

Chetniks

The Chetniks ( sh-Cyrl-Latn, Четници, Četnici, ; sl, Četniki), formally the Chetnik Detachments of the Yugoslav Army, and also the Yugoslav Army in the Homeland and the Ravna Gora Movement, was a Yugoslav royalist and Serbian nationa ...

. The Prime Minister throughout was General

Milan Nedić. The Government of National Salvation was evacuated from Belgrade to

Kitzbühel

Kitzbühel (, also: ; ) is a medieval town situated in the Kitzbühel Alps along the river Kitzbüheler Ache in Tyrol, Austria, about east of the state capital Innsbruck and is the administrative centre of the Kitzbühel district (). Kitzbühel ...

,

Germany in the first week of October 1944 before the German withdrawal from Serbia was complete.

Racial laws were introduced in all occupied territories with immediate effects on Jews and Roma people, as well as causing the imprisonment of those opposed to Nazism. Several concentration camps were formed in Serbia and at the 1942 Anti-Freemason Exhibition in Belgrade the city was pronounced to be free of Jews (Judenfrei). On 1 April 1942, a Serbian Gestapo was formed. An estimated 120,000 people were interned in German-run concentration camps in Nedić's Serbia between 1941 and 1944. However the

Banjica Concentration Camp was jointly run by the German Army and Nedic's regime.

50,000 to 80,000 were killed during this period. Serbia became the second country in Europe, following Estonia, to be proclaimed Judenfrei (free of Jews). Approximately 14,500 Serbian Jews – 90 percent of Serbia's Jewish population of 16,000 – were murdered in World War II.

Nedić was captured by the Americans when they occupied the former territory of Austria, and was subsequently handed over to the Yugoslav communist authorities to act as a witness against war criminals, on the understanding he would be returned to American custody to face trial by the Allies. The Yugoslav authorities refused to return Nedić to United States custody. He died on 4 February 1946 after either jumping or falling out of the window of a Belgrade hospital, under circumstances which remain unclear.

Italy (Italian Social Republic)

Italian Fascist leader

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

formed the Italian Social Republic (''Repubblica Sociale Italiana'' in

Italian) on 23 September 1943, succeeding the Kingdom of Italy as a member of the Axis.

Mussolini had been removed from office and arrested by King Victor Emmanuel III on 25 July 1943. After the Italian armistice, in a

raid led by German paratrooper

Otto Skorzeny, Mussolini was rescued from arrest.