Australian poetry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Australian literature is the written or literary work produced in the area or by the people of the

Australian writers who have obtained international renown include the Nobel-winning author

Australian writers who have obtained international renown include the Nobel-winning author

Writing by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

While his father,

Writing by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

While his father,  Many notable works have been written by non-indigenous Australians on Aboriginal themes. Examples include the poems of

Many notable works have been written by non-indigenous Australians on Aboriginal themes. Examples include the poems of

For centuries before the British settlement of Australia, European writers wrote fictional accounts of an imaginings of a ''Great Southern Land''. In 1642

For centuries before the British settlement of Australia, European writers wrote fictional accounts of an imaginings of a ''Great Southern Land''. In 1642

Commonwealth of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands. With an area of , Australia is the largest country by ...

and its preceding colonies. During its early Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

* Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that i ...

history, Australia was a collection of British colonies; as such, its recognised literary tradition begins with and is linked to the broader tradition of English literature

English literature is literature written in the English language from United Kingdom, its crown dependencies, the Republic of Ireland, the United States, and the countries of the former British Empire. ''The Encyclopaedia Britannica'' defines E ...

. However, the narrative art of Australian writers has, since 1788, introduced the character of a new continent into literature—exploring such themes as Aboriginality

Aboriginal Australian identity, sometimes known as Aboriginality, is the Identity (social science), perception of oneself as Aboriginal Australian, or the recognition by others of that identity. This is often related to the existence of (or the b ...

, ''mateship

Mateship is an Australian cultural idiom that embodies equality, loyalty and friendship. Russel Ward, in ''The Australian Legend'' (1958), once saw the concept as central to the Australian people. ''Mateship'' derives from '' mate'', meaning '' ...

'', egalitarianism

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

, democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

, national identity, migration, Australia's unique location and geography, the complexities of urban living, and " the beauty and the terror" of life in the Australian bush

"The bush" is a term mostly used in the English vernacular of Australia and New Zealand where it is largely synonymous with ''backwoods'' or '' hinterland'', referring to a natural undeveloped area. The fauna and flora contained within this ...

.

Overview

Australian writers who have obtained international renown include the Nobel-winning author

Australian writers who have obtained international renown include the Nobel-winning author Patrick White

Patrick Victor Martindale White (28 May 1912 – 30 September 1990) was a British-born Australian writer who published 12 novels, three short-story collections, and eight plays, from 1935 to 1987.

White's fiction employs humour, florid prose, ...

, as well as authors Christina Stead

Christina Stead (17 July 190231 March 1983) was an Australian novelist and short-story writer acclaimed for her satirical wit and penetrating psychological characterisations. Christina Stead was a committed Marxist, although she was never a me ...

, David Malouf

David George Joseph Malouf AO (; born 20 March 1934) is an Australian poet, novelist, short story writer, playwright and librettist. Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2008, Malouf has lectured at both the University of Quee ...

, Peter Carey, Bradley Trevor Greive

Bradley Trevor Greive (born 22 February 1970) is an Australian author. He has written 24 books which have been translated into 27 different languages, and have been sold in 115 different countries, several of which have appeared in the ''New Y ...

, Thomas Keneally

Thomas Michael Keneally, Officer of the Order of Australia, AO (born 7 October 1935) is an Australian novelist, playwright, essayist, and actor. He is best known for his non-fiction novel ''Schindler's Ark'', the story of Oskar Schindler's rescu ...

, Colleen McCullough

Colleen Margaretta McCullough (; married name Robinson, previously Ion-Robinson; 1 June 193729 January 2015) was an Australian author known for her novels, her most well-known being '' The Thorn Birds'' and '' The Ladies of Missalonghi''.

Lif ...

, Nevil Shute

Nevil Shute Norway (17 January 189912 January 1960) was an English novelist and aeronautical engineer who spent his later years in Australia. He used his full name in his engineering career and Nevil Shute as his pen name, in order to protect ...

and Morris West

Morris Langlo West (26 April 19169 October 1999) was an Australian novelist and playwright, best known for his novels '' The Devil's Advocate'' (1959), '' The Shoes of the Fisherman'' (1963) and ''The Clowns of God'' (1981). His books were pub ...

. Notable contemporary expatriate authors include the feminist Germaine Greer

Germaine Greer (; born 29 January 1939) is an Australian writer and public intellectual, regarded as one of the major voices of the radical feminist movement in the latter half of the 20th century.

Specializing in English and women's literatu ...

, art historian Robert Hughes and humorists Barry Humphries

John Barry Humphries (born 17 February 1934) is an Australian comedian, actor, author and satirist. He is best known for writing and playing his on-stage and television alter egos Dame Edna Everage and Sir Les Patterson. He is also a film pro ...

and Clive James

Clive James (born Vivian Leopold James; 7 October 1939 – 24 November 2019) was an Australian critic, journalist, broadcaster, writer and lyricist who lived and worked in the United Kingdom from 1962 until his death in 2019.Henry Lawson

Henry Archibald Hertzberg Lawson (17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922) was an Australian writer and bush poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial perio ...

, Banjo Paterson

Andrew Barton "Banjo" Paterson, (17 February 18645 February 1941) was an Australian bush poet, journalist and author. He wrote many ballads and poems about Australian life, focusing particularly on the rural and outback areas, including the d ...

, C. J. Dennis

Clarence Michael James Stanislaus Dennis (7 September 1876 – 22 June 1938), better known as C. J. Dennis, was an Australian poet and journalist known for his best-selling verse novel ''The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke'' (1915). Alongside ...

and Dorothea Mackellar

Isobel Marion Dorothea Mackellar, (1 July 1885 – 14 January 1968) was an Australian poet and fiction writer. Her poem '' My Country'' is widely known in Australia, especially its second stanza, which begins: "''I love a sunburnt countr ...

. Dennis wrote in the Australian vernacular, while Mackellar wrote the iconic patriotic poem'' My Country

"My Country" is a poem about Australia, written by Dorothea Mackellar (1885–1968) at the age of 19 while homesick in the United Kingdom. After travelling through Europe extensively with her father during her teenage years, she started ...

''. Lawson and Paterson clashed in the famous "Bulletin Debate

The "''Bulletin'' Debate" was a well-publicised dispute in ''The Bulletin'' magazine between two of Australia's best known writers and poets, Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson. The debate took place via a series of poems about the merits of livin ...

" over the nature of life in Australia with Lawson considered to have the harder edged view of the Bush and Paterson the romantic. Lawson is widely regarded as one of Australia's greatest writers of short stories, while Paterson's poems remain amongst the most popular Australian bush poems. Significant poets of the 20th century included Dame Mary Gilmore

Dame Mary Jean Gilmore (née Cameron; 16 August 18653 December 1962) was an Australian writer and journalist known for her prolific contributions to Australian literature and the broader national discourse. She wrote both prose and poetry.

G ...

, Kenneth Slessor

Kenneth Adolphe Slessor (27 March 190130 June 1971) was an Australian poet, journalist and official war correspondent in World War II. He was one of Australia's leading poets, notable particularly for the absorption of modernist influences int ...

, A. D. Hope

Alec Derwent Hope (21 July 190713 July 2000) was an Australian poet and essayist known for his satirical slant. He was also a critic, teacher and academic. He was referred to in an American journal as "the 20th century's greatest 18th-century ...

and Judith Wright

Judith Arundell Wright (31 May 191525 June 2000) was an Australian poet, environmentalist and campaigner for Aboriginal land rights. She was a recipient of the Christopher Brennan Award.

Biography

Judith Wright was born in Armidale, N ...

. Among the best known contemporary poets are Les Murray and Bruce Dawe

Donald Bruce Dawe (15 February 1930 – 1 April 2020) was an Australian poet and academic. Some critics consider him one of the most influential Australian poets of all time.

, whose poems are often studied in Australian high schools.

Novelists of classic Australian works include Marcus Clarke

Marcus Andrew Hislop Clarke (24 April 1846 – 2 August 1881) was an English-born Australian novelist, journalist, poet, editor, librarian, and playwright. He is best known for his 1874 novel ''For the Term of His Natural Life'', about the con ...

(''For the Term of His Natural Life

''For the Term of His Natural Life'' is a story written by Marcus Clarke and published in ''The Australian Journal'' between 1870 and 1872 (as ''His Natural Life''). It was published as a novel in 1874 and is the best known novelisation of lif ...

''), Miles Franklin

Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin (14 October 187919 September 1954), known as Miles Franklin, was an Australian writer and feminist who is best known for her novel '' My Brilliant Career'', published by Blackwoods of Edinburgh in 1901. While ...

(''My Brilliant Career

''My Brilliant Career'' is a 1901 novel written by Miles Franklin. It is the first of many novels by Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin (1879–1954), one of the major Australian writers of her time. It was written while she was still a teenage ...

''), Henry Handel Richardson

Ethel Florence Lindesay Richardson (3 January 187020 March 1946), known by her pen name Henry Handel Richardson, was an Australian author.

Life

Born in East Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, into a prosperous family that later fell on hard tim ...

(''The Fortunes of Richard Mahony

''The Fortunes of Richard Mahony'' is a three-part novel by Australian writer Ethel Florence Lindesay Richardson under her pen name, Henry Handel Richardson. It consists of ''Australia Felix'' (1917), ''The Way Home'' (1925), and ''Ultima Thule'' ...

''), Joseph Furphy

Joseph Furphy ( Irish: Seosamh Ó Foirbhithe; 26 September 1843 – 13 September 1912) was an Australian author and poet who is widely regarded as the "Father of the Australian novel". He mostly wrote under the pseudonym Tom Collins and is best ...

(''Such Is Life Such Is Life may refer to:

Film

* ''Such Is Life'' (1915 film), an American silent film starring Lon Chaney, Sr.

* ''Such Is Life'' (1924 film), an American silent short film starring Baby Peggy

Diana Serra Cary (born Peggy-Jean Montgomery; O ...

''), Rolf Boldrewood

Thomas Alexander Browne (born Brown, 6 August 1826 – 11 March 1915) was an Australian author who published many of his works under the pseudonym Rolf Boldrewood. He is best known for his 1882 bushranging novel '' Robbery Under Arms''.

Biog ...

(''Robbery Under Arms

''Robbery Under Arms'' is a bushranger novel by Thomas Alexander Browne, published under his pen name Rolf Boldrewood. It was first published in serialised form by ''The Sydney Mail'' between July 1882 and August 1883, then in three volumes i ...

'') and Ruth Park

Rosina Ruth Lucia Park AM (24 August 191714 December 2010) was a New Zealand–born Australian author. Her best known works are the novels '' The Harp in the South'' (1948) and '' Playing Beatie Bow'' (1980), and the children's radio serial '' ...

(''The Harp in the South

''The Harp in the South'' is the debut novel by Australian author Ruth Park. Published in 1948, it portrays the life of a Catholic Irish Australian family living in the Sydney suburb of Surry Hills, which was at that time an inner city slum.

...

''). In terms of children's literature, Norman Lindsay

Norman Alfred William Lindsay (22 February 1879 – 21 November 1969) was an Australian artist, etcher, sculptor, writer, art critic, novelist, cartoonist and amateur boxer. One of the most prolific and popular Australian artists of his genera ...

(''The Magic Pudding

''The Magic Pudding: Being The Adventures of Bunyip Bluegum and his friends Bill Barnacle and Sam Sawnoff'' is a 1918 Australian children's book written and illustrated by Norman Lindsay. It is a comic fantasy, and a classic of Australian childr ...

''), Mem Fox

Merrion Frances "Mem" Fox, AM (born Merrion Frances Partridge; 5 March 1946) is an Australian writer of children's books and an educationalist specialising in literacy. Fox has been semi-retired since 1996, but she still gives seminars and ...

(''Possum Magic

''Possum Magic'' is a 1983 Children's picture book by Australian author Mem Fox, and illustrated by Julie Vivas. It concerns a young female possum, named Hush, who becomes invisible and has a number of adventures. In 2001, a film was made by the ...

''), and May Gibbs

Cecilia May Gibbs MBE (17 January 1877 – 27 November 1969) was an Australian children's author, illustrator, and cartoonist. She is best known for her gumnut babies (also known as "bush babies" or "bush fairies"), and the book '' Snugglepot ...

(''Snugglepot and Cuddlepie

''Snugglepot and Cuddlepie'' is a series of books written by Australian author May Gibbs. The books chronicle the adventures of the eponymous Snugglepot and Cuddlepie. The central story arc concerns Snugglepot and Cuddlepie (who are essentially ...

'') are among the Australian classics, while Melina Marchetta

Carmelina Marchetta (born 25 March 1965) is an Australian writer and teacher. Marchetta is best known as the author of teen novels, '' Looking for Alibrandi'', ''Saving Francesca'' and ''On the Jellicoe Road''. She has twice been awarded the CB ...

('' Looking for Alibrandi'') is a modern YA classic. Eminent Australian playwrights have included Ray Lawler

Raymond Evenor Lawler (born 23 May 1921) is an Australian actor, dramatist, and theatre producer and director. His most notable play was his tenth, '' Summer of the Seventeenth Doll'' (1953), which had its premiere in Melbourne in 1955. The ...

, David Williamson

David Keith Williamson AO (born 24 February 1942) is an Australian dramatist and playwright. He has also written screenplays and teleplays.

Early life

David Williamson was born in Melbourne, Victoria, on 24 February 1942, and was brought up ...

, Alan Seymour

Alan Seymour (6 June 192723 March 2015) was an Australian playwright and author. He is best known for the play ''The One Day of the Year'' (1958). His international reputation rests not only on this early play, but also on his many screenplays, ...

and Nick Enright

Nicholas Paul Enright AM (22 December 1950 – 30 March 2003) was an Australian dramatist, playwright and theatre director.

Early life

Enright was born on 22 December 1950 to a prosperous professional Catholic family in East Maitland, New So ...

. Among prominent short story writers are Steele Rudd

Steele Rudd was the pen name of Arthur Hoey Davis (14 November 1868 – 11 October 1935) an Australian author, best known for his short story collection ''On Our Selection''.

In 2009, as part of the Q150 celebrations, Rudd was named one of the ...

, Henry Lawson

Henry Archibald Hertzberg Lawson (17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922) was an Australian writer and bush poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial perio ...

, Beverley Farmer

Beverley Anne Farmer (also known as B. Christou) (7 February 1941 – 16 April 2018) was an Australian novelist and short story writer.

Personal life

Beverley Farmer was born in Melbourne. She was educated at Mac.Robertson Girls' High School an ...

, Kate Grenville

Catherine Elizabeth Grenville (born 1950) is an Australian author. She has published fifteen books, including fiction, non-fiction, biography, and books about the writing process. In 2001, she won the Orange Prize for ''The Idea of Perfection ...

, and Helen Garner

Helen Garner (née Ford, born 7 November 1942) is an Australian novelist, short-story writer, screenwriter and journalist. Garner's first novel, '' Monkey Grip'', published in 1977, immediately established her as an original voice on the Aust ...

.

Although historically only a small proportion of Australia's population have lived outside the major cities, many of Australia's most distinctive stories and legends originate in the outback

The Outback is a remote, vast, sparsely populated area of Australia. The Outback is more remote than the bush. While often envisaged as being arid, the Outback regions extend from the northern to southern Australian coastlines and encompass a ...

, in the drovers and squatters and people of the barren, dusty plains.

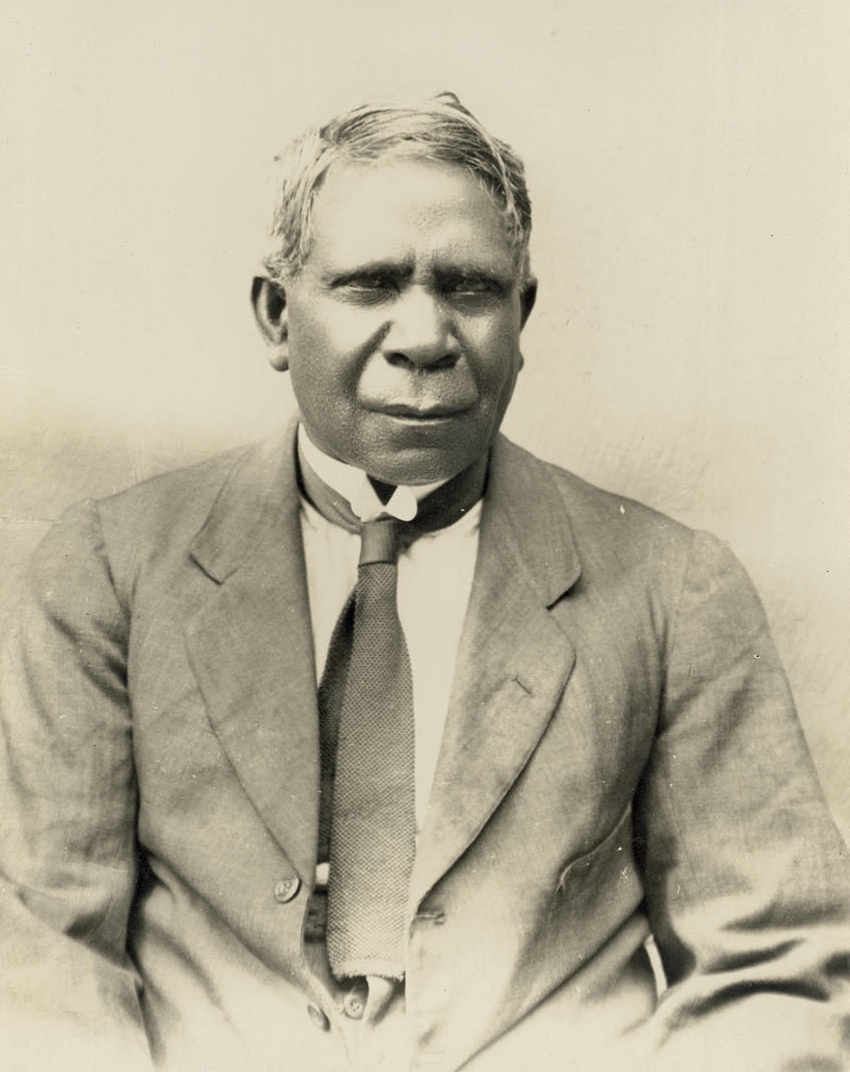

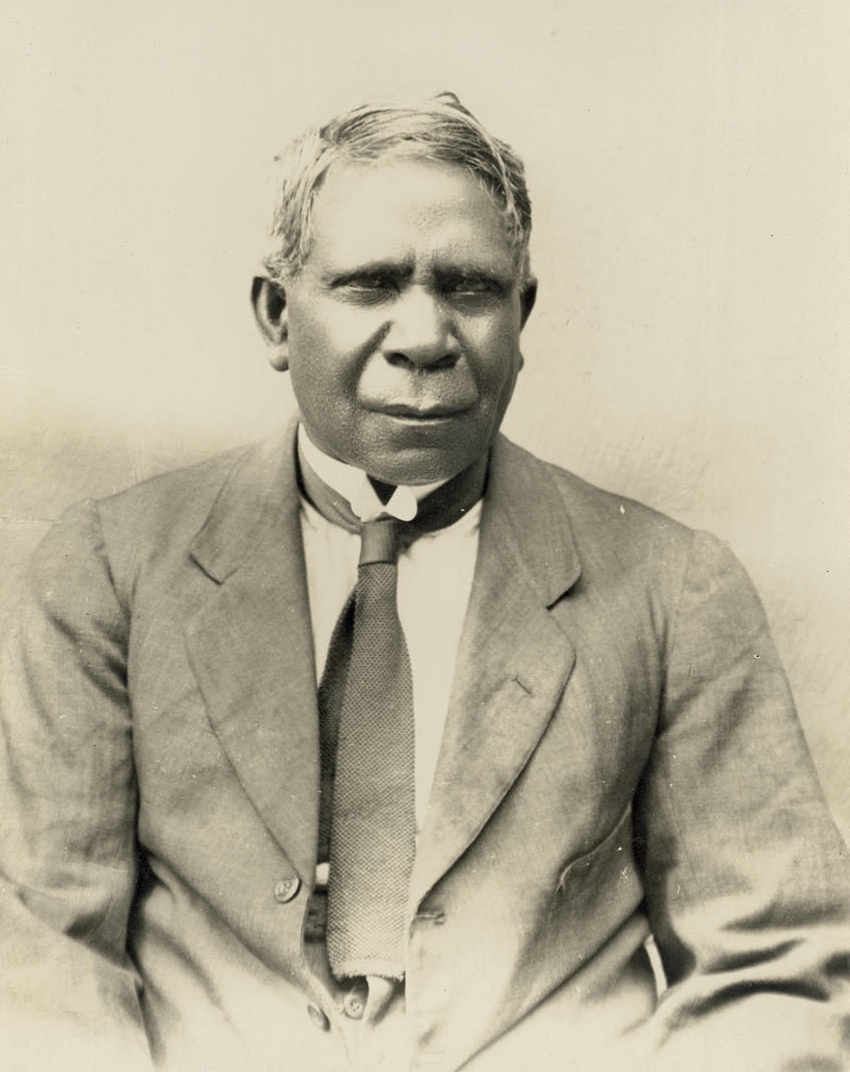

David Unaipon

David Ngunaitponi (28 September 1872 – 7 February 1967), known as David Unaipon, was an Aboriginal Australian man of the Ngarrindjeri people. He was a preacher, inventor and author. Unaipon's contribution to Australian society helped to bre ...

is known as the first Aboriginal author. Oodgeroo Noonuccal

Oodgeroo Noonuccal ( ; born Kathleen Jean Mary Ruska, later Kath Walker (3 November 192016 September 1993) was an Aboriginal Australian political activist, artist and educator, who campaigned for Aboriginal rights. Noonuccal was best known for ...

was the first Aboriginal Australian

Aboriginal Australians are the various Indigenous peoples of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland and many of its islands, such as Tasmania, Fraser Island, Hinchinbrook Island, the Tiwi Islands, and Groote Eylandt, but excluding the T ...

to publish a book of verse. A ground-breaking memoir about the experiences of the Stolen Generations

The Stolen Generations (also known as Stolen Children) were the children of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent who were removed from their families by the Australian federal and state government agencies and church miss ...

can be found in Sally Morgan's '' My Place''.

Charles Bean

Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean (18 November 1879 – 30 August 1968), usually identified as C. E. W. Bean, was Australia's official war correspondent, subsequently its official war historian, who wrote six volumes and edited the remaining six of ...

, Geoffrey Blainey

Geoffrey Norman Blainey (born 11 March 1930) is an Australian historian, academic, best selling author and commentator. He is noted for having written authoritative texts on the economic and social history of Australia, including '' The Tyranny ...

, Robert Hughes, Manning Clark

Charles Manning Hope Clark, (3 March 1915 – 23 May 1991) was an Australian historian and the author of the best-known general history of Australia, his six-volume ''A History of Australia'', published between 1962 and 1987. He has been descri ...

, Claire Wright, and Marcia Langton

Marcia Lynne Langton (born 1951) is an Australian academic. she is the Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor at the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne. Regarded as one of Australia's top intellectuals, L ...

are authors of important Australian histories.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writers and themes

Writing by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

While his father,

Writing by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

While his father, James Unaipon

James Unaipon, born James Ngunaitponi, (c. 1835 – 1907) was an Australian Indigenous preacher of the Warrawaldie (also spelt Waruwaldi) Lakalinyeri of the Ngarrindjeri.

Born James Ngunaitponi, he took the name James Reid in honour of the S ...

(c.1835-1907), contributed to accounts of Aboriginal mythology written by the missionary George Taplin, David Unaipon

David Ngunaitponi (28 September 1872 – 7 February 1967), known as David Unaipon, was an Aboriginal Australian man of the Ngarrindjeri people. He was a preacher, inventor and author. Unaipon's contribution to Australian society helped to bre ...

(1872–1967) provided the first accounts of Aboriginal mythology written by an Aboriginal: '' Legendary Tales of the Aborigines''. For this he is known as the first Aboriginal author. Oodgeroo Noonuccal

Oodgeroo Noonuccal ( ; born Kathleen Jean Mary Ruska, later Kath Walker (3 November 192016 September 1993) was an Aboriginal Australian political activist, artist and educator, who campaigned for Aboriginal rights. Noonuccal was best known for ...

(1920–1993) was a famous Aboriginal poet, writer and rights activist credited with publishing the first Aboriginal book of verse: ''We Are Going

''We Are Going'' (1964) is a collection of poems by Australian writer Oodgeroo Noonuccal. It was published by Jacaranda Press in 1964.

The collection includes 29 poems by the author, from a variety of original sources. This is the first colle ...

'' (1964). Sally Morgan's novel '' My Place'' was considered a breakthrough memoir in terms of bringing indigenous stories to wider notice. Leading Aboriginal activists Marcia Langton

Marcia Lynne Langton (born 1951) is an Australian academic. she is the Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor at the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne. Regarded as one of Australia's top intellectuals, L ...

(First Australians

''First Australians'' is an Australian historical documentary series produced by Blackfella Films over the course of six years, and first aired on SBS TV in October 2008. The documentary is part of a greater project that further consists of ...

, 2008) and Noel Pearson

Noel or Noël may refer to:

Christmas

* , French for Christmas

* Noel is another name for a Christmas carol

Places

* Noel, Missouri, United States, a city

* Noel, Nova Scotia, Canada, a community

*1563 Noël, an asteroid

* Mount Noel, Briti ...

('' Up from the Mission'', 2009) are active contemporary contributors to Australian literature.

The voices of Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples o ...

are being increasingly noticed and include the playwright

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays.

Etymology

The word "play" is from Middle English pleye, from Old English plæġ, pleġa, plæġa ("play, exercise; sport, game; drama, applause"). The word "wright" is an archaic English ...

Jack Davis and Kevin Gilbert. Writers coming to prominence in the 21st century include Kim Scott

Kim Scott (born 18 February 1957) is an Australian novelist of Aboriginal Australian ancestry. He is a descendant of the Noongar people of Western Australia.

Biography

Scott was born in Perth in 1957 and is the eldest of four siblings with ...

, Alexis Wright

Alexis Wright (born 25 November 1950) is a Waanyi (Aboriginal Australian) writer best known for winning the Miles Franklin Award for her 2006 novel '' Carpentaria'' and the 2018 Stella Prize for her "collective memoir" of Leigh Bruce "Tracke ...

, Kate Howarth, Tara June Winch

Tara June Winch (born 1983) is an Australian writer. She is the 2020 winner of the Miles Franklin Award for her book ''The Yield''.

Biography

Tara June Winch was born in Wollongong, New South Wales, Australia in 1983. Her father is from the Wi ...

, Yvette Holt

Yvette Henry Holt (born 1971) is an Aboriginal Australian poet, essayist, academic, researcher and comedian, of the Bidjara, Yiman and Wakaman nations of Queensland. She came to prominence with her first published collection of poetry, ''Anonym ...

and Anita Heiss

Anita Marianne Heiss (born 1968) is an Aboriginal Australian author, poet, cultural activist and social commentator. She is an advocate for Indigenous Australian literature and literacy, through her writing for adults and children and her me ...

. Indigenous authors who have won Australia's high prestige Miles Franklin Award

The Miles Franklin Literary Award is an annual literary prize awarded to "a novel which is of the highest literary merit and presents Australian life in any of its phases". The award was set up according to the will of Miles Franklin (1879– ...

include Kim Scott

Kim Scott (born 18 February 1957) is an Australian novelist of Aboriginal Australian ancestry. He is a descendant of the Noongar people of Western Australia.

Biography

Scott was born in Perth in 1957 and is the eldest of four siblings with ...

who was joint winner (with Thea Astley

Thea Beatrice May Astley (25 August 1925 – 17 August 2004) was an Australian novelist and short story writer. She was a prolific writer who was published for over 40 years from 1958. At the time of her death, she had won more Miles Frankli ...

) in 2000 for '' Benang'' and again in 2011 for ''That Deadman Dance

''That Deadman Dance'' is the third novel by Western Australian author Kim Scott. It was first published in 2010 by Picador (Australia) and by Bloomsbury in the UK, US and Canada in 2012. It won the 2011 Regional Commonwealth Writers' Prize, t ...

.'' Alexis Wright

Alexis Wright (born 25 November 1950) is a Waanyi (Aboriginal Australian) writer best known for winning the Miles Franklin Award for her 2006 novel '' Carpentaria'' and the 2018 Stella Prize for her "collective memoir" of Leigh Bruce "Tracke ...

won the award in 2007 for her novel ''Carpentaria

''Carpentaria acuminata'' (carpentaria palm), the sole species in the genus ''Carpentaria'', is a palm native to tropical coastal regions in the north of Northern Territory, Australia.

It is a slender palm, growing to tall in the garden situ ...

.'' Melissa Lucashenko

Melissa Lucashenko is an Indigenous Australian writer of adult literary fiction and literary non-fiction, who has also written novels for teenagers.

In 2013 at The Walkley Awards, she won the "Feature Writing Long (over 4000 words) Award" for ...

won the award in 2019 for her novel ''Too Much Lip

''Too Much Lip'' (2018) is a novel by Australian author Melissa Lucashenko. It was shortlisted for the 2019 Victorian Premier's Literary Award for Indigenous Writing and the Stella Award. It was the winner of the 2019 Miles Franklin Award.

Pl ...

'', which was also short-listed for the Stella Prize

The Stella Prize is an Australian annual literary award established in 2013 for writing by Australian women in all genres, worth $50,000. It was originally proposed by Australian women writers and publishers in 2011, modelled on the UK's Baileys W ...

for Australian women's writing.

Letters written by notable Aboriginal leaders like Bennelong

Woollarawarre Bennelong ( 1764 – 3 January 1813), also spelt Baneelon, was a senior man of the Eora, an Aboriginal Australian people of the Port Jackson area, at the time of the first British settlement in Australia in 1788. Bennelong ser ...

and Sir Douglas Nicholls

Sir Douglas Ralph Nicholls, (9 December 1906 – 4 June 1988) was a prominent Aboriginal Australian from the Yorta Yorta people. He was a professional athlete, Churches of Christ pastor and church planter, ceremonial officer and a pioneering ...

are also retained as treasures of Australian literature, as is the historic Yirrkala bark petitions

The Yirrkala bark petitions, sent by the Yolngu people, an Aboriginal Australian people of Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory, to the Australian Parliament in 1963, were the first traditional documents prepared by Indigenous Australians that ...

of 1963 which is the first traditional Aboriginal document recognised by the Australian Parliament

The Parliament of Australia (officially the Federal Parliament, also called the Commonwealth Parliament) is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It consists of three elements: the monarch (represented by the governor-gen ...

. AustLit

AustLit: The Australian Literature Resource (also known as AustLit: Australian Literature Gateway; and AustLit: The Resource for Australian Literature), usually referred to simply as AustLit, is an internet-based, non-profit collaboration betwee ...

's BlackWords project provides a comprehensive listing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Writers and Storytellers.

Writing about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

At the point of the first colonization, Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples o ...

had not developed a system of writing, so the first literary accounts of Aboriginal people come from the journals of early European explorers, which contain descriptions of first contact, both violent and friendly. Early accounts by Dutch explorers and by the English buccaneer William Dampier

William Dampier (baptised 5 September 1651; died March 1715) was an English explorer, pirate, privateer, navigator, and naturalist who became the first Englishman to explore parts of what is today Australia, and the first person to circumna ...

wrote of the "natives of New Holland" as being "barbarous savages", but by the time of Captain James Cook and First Fleet marine Watkin Tench

Lieutenant General Watkin Tench (6 October 1758 – 7 May 1833) was a British marine officer who is best known for publishing two books describing his experiences in the First Fleet, which established the first European settlement in Australia ...

(the era of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revol ...

), accounts of Aborigines were more sympathetic and romantic: "these people may truly be said to be in the pure state of nature, and may appear to some to be the most wretched upon the earth; but in reality they are far happier than ... we Europeans", wrote Cook in his journal on 23 August 1770. Many notable works have been written by non-indigenous Australians on Aboriginal themes. Examples include the poems of

Many notable works have been written by non-indigenous Australians on Aboriginal themes. Examples include the poems of Judith Wright

Judith Arundell Wright (31 May 191525 June 2000) was an Australian poet, environmentalist and campaigner for Aboriginal land rights. She was a recipient of the Christopher Brennan Award.

Biography

Judith Wright was born in Armidale, N ...

; ''The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith

''The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith'' is a 1972 Booker Prize-nominated Australian novel by Thomas Keneally, and a 1978 Australian film of the same name directed by Fred Schepisi. The novel is based on the life of bushranger Jimmy Governor, the su ...

'' by Thomas Keneally

Thomas Michael Keneally, Officer of the Order of Australia, AO (born 7 October 1935) is an Australian novelist, playwright, essayist, and actor. He is best known for his non-fiction novel ''Schindler's Ark'', the story of Oskar Schindler's rescu ...

, ''Ilbarana'' by Donald Stuart, and the short story by David Malouf

David George Joseph Malouf AO (; born 20 March 1934) is an Australian poet, novelist, short story writer, playwright and librettist. Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2008, Malouf has lectured at both the University of Quee ...

: "The Only Speaker of his Tongue". Histories covering Indigenous themes include Watkin Tench

Lieutenant General Watkin Tench (6 October 1758 – 7 May 1833) was a British marine officer who is best known for publishing two books describing his experiences in the First Fleet, which established the first European settlement in Australia ...

(Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay et Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson); Roderick J. Flanagan (''The Aborigines of Australia'', 1888); ''The Native Tribes of Central Australia'' by Spencer and Gillen, 1899; the diaries of Donald Thompson on the subject of the Yolngu people of Arnhem Land

Arnhem Land is a historical region of the Northern Territory of Australia, with the term still in use. It is located in the north-eastern corner of the territory and is around from the territory capital, Darwin. In 1623, Dutch East India Company ...

(c.1935-1943); Alan Moorehead

Alan McCrae Moorehead, (22 July 1910 – 29 September 1983) was a war correspondent and author of popular histories, most notably two books on the nineteenth-century exploration of the Nile, ''The White Nile'' (1960) and ''The Blue Nile'' (196 ...

(''The fatal Impact'', 1966); Geoffrey Blainey

Geoffrey Norman Blainey (born 11 March 1930) is an Australian historian, academic, best selling author and commentator. He is noted for having written authoritative texts on the economic and social history of Australia, including '' The Tyranny ...

(''Triumph of the Nomads'', 1975); Henry Reynolds (''The Other Side of the Frontier

''The Other Side of the Frontier'' is a history book published in 1981 by Australian historian Henry Reynolds. It is a study of Aboriginal Australian resistance to the British settlement, or invasion, of Australia from 1788 onwards.

The book ...

'', 1981); and Marcia Langton

Marcia Lynne Langton (born 1951) is an Australian academic. she is the Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor at the Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, University of Melbourne. Regarded as one of Australia's top intellectuals, L ...

(First Australians, 2008). Differing interpretations of Aboriginal history are also the subject of contemporary debate in Australia, notably between the essayists Robert Manne

Robert Michael Manne (born 31 October 1947) is an Emeritus Professor of politics and Vice-Chancellor's Fellow at La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia. He is a leading Australian public intellectual.

Background

Robert Manne was born in Melbo ...

and Keith Windschuttle

Keith Windschuttle (born 1942) is an Australian historian and former board member of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

He was editor of '' Quadrant'' from 2007 to 2015 when he became chair of the board and editor-in-chief. He was the pub ...

.

Early and classic works

For centuries before the British settlement of Australia, European writers wrote fictional accounts of an imaginings of a ''Great Southern Land''. In 1642

For centuries before the British settlement of Australia, European writers wrote fictional accounts of an imaginings of a ''Great Southern Land''. In 1642 Abel Janszoon Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first known European explorer to reach New Z ...

landed in Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

and after examining notches cut at considerable distances on tree trunks, speculated that the newly discovered country must be peopled by giants. Later, the British satirist, Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whigs, then for the Tories), poet, and Anglican cleric who became Dean of St Patrick's Cathedral, ...

, set the land of the Houyhnhnms

Houyhnhnms are a fictional race of intelligent horses described in the last part of Jonathan Swift's satirical 1726 novel ''Gulliver's Travels''. The name is pronounced either or . Swift apparently intended all words of the Houyhnhnm language ...

of Gulliver's Travels

''Gulliver's Travels'', or ''Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships'' is a 1726 prose satire by the Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan ...

to the west of Tasmania. In 1797 the British Romantic

Romantic may refer to:

Genres and eras

* The Romantic era, an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement of the 18th and 19th centuries

** Romantic music, of that era

** Romantic poetry, of that era

** Romanticism in science, of that e ...

poet Robert Southey

Robert Southey ( or ; 12 August 1774 – 21 March 1843) was an English poet of the Romantic school, and Poet Laureate from 1813 until his death. Like the other Lake Poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Southey began as a ...

—then a young Jacobin

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = P ...

—included a section in his collection, "Poems", a selection of poems under the heading, "Botany Bay Eclogues," in which he portrayed the plight and stories of transported convicts in New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

.

Among the first true works of literature produced in Australia were the accounts of the settlement of Sydney by Watkin Tench

Lieutenant General Watkin Tench (6 October 1758 – 7 May 1833) was a British marine officer who is best known for publishing two books describing his experiences in the First Fleet, which established the first European settlement in Australia ...

, a captain of the marines on the First Fleet to arrive in 1788. In 1819, poet, explorer, journalist and politician William Wentworth

William Charles Wentworth (August 179020 March 1872) was an Australian pastoralist, explorer, newspaper editor, lawyer, politician and author, who became one of the wealthiest and most powerful figures of early colonial New South Wales.

Throug ...

published the first book written by an Australian: ''A Statistical, Historical, and Political Description of the Colony of New South Wales and Its Dependent Settlements in Van Diemen's Land, With a Particular Enumeration of the Advantages Which These Colonies Offer for Emigration and Their Superiority in Many Respects Over Those Possessed by the United States of America'', in which he advocated an elected assembly for New South Wales, trial by jury and settlement of Australia by free emigrants rather than convicts

The first novel to be published in Australia was a crime novel, ''Quintus Servinton: A Tale founded upon Incidents of Real Occurrence'' by Henry Savery

Henry Savery (4 August 1791 – 6 February 1842) was a convict transported to Port Arthur, Tasmania, and Australia's first novelist. It is generally agreed that his writing is more important for its historical value than its literary merit.''Q ...

published in Hobart in 1830. Early popular works tended to be the 'ripping yarn' variety, telling tales of derring-do against the new frontier

A frontier is the political and geographical area near or beyond a boundary. A frontier can also be referred to as a "front". The term came from French in the 15th century, with the meaning "borderland"—the region of a country that fronts ...

of the Australian outback

The Outback is a remote, vast, sparsely populated area of Australia. The Outback is more remote than the bush. While often envisaged as being arid, the Outback regions extend from the northern to southern Australian coastlines and encompass a ...

. Writers such as Rolf Boldrewood

Thomas Alexander Browne (born Brown, 6 August 1826 – 11 March 1915) was an Australian author who published many of his works under the pseudonym Rolf Boldrewood. He is best known for his 1882 bushranging novel '' Robbery Under Arms''.

Biog ...

(''Robbery Under Arms

''Robbery Under Arms'' is a bushranger novel by Thomas Alexander Browne, published under his pen name Rolf Boldrewood. It was first published in serialised form by ''The Sydney Mail'' between July 1882 and August 1883, then in three volumes i ...

''), Marcus Clarke

Marcus Andrew Hislop Clarke (24 April 1846 – 2 August 1881) was an English-born Australian novelist, journalist, poet, editor, librarian, and playwright. He is best known for his 1874 novel ''For the Term of His Natural Life'', about the con ...

(''For the Term of His Natural Life

''For the Term of His Natural Life'' is a story written by Marcus Clarke and published in ''The Australian Journal'' between 1870 and 1872 (as ''His Natural Life''). It was published as a novel in 1874 and is the best known novelisation of lif ...

''), Henry Handel Richardson

Ethel Florence Lindesay Richardson (3 January 187020 March 1946), known by her pen name Henry Handel Richardson, was an Australian author.

Life

Born in East Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, into a prosperous family that later fell on hard tim ...

(''The Fortunes of Richard Mahony

''The Fortunes of Richard Mahony'' is a three-part novel by Australian writer Ethel Florence Lindesay Richardson under her pen name, Henry Handel Richardson. It consists of ''Australia Felix'' (1917), ''The Way Home'' (1925), and ''Ultima Thule'' ...

'') and Joseph Furphy

Joseph Furphy ( Irish: Seosamh Ó Foirbhithe; 26 September 1843 – 13 September 1912) was an Australian author and poet who is widely regarded as the "Father of the Australian novel". He mostly wrote under the pseudonym Tom Collins and is best ...

(''Such Is Life Such Is Life may refer to:

Film

* ''Such Is Life'' (1915 film), an American silent film starring Lon Chaney, Sr.

* ''Such Is Life'' (1924 film), an American silent short film starring Baby Peggy

Diana Serra Cary (born Peggy-Jean Montgomery; O ...

'') embodied these stirring ideals in their tales and, particularly the latter, tried to accurately record the vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

language of the common Australian. These novelist

A novelist is an author or writer of novels, though often novelists also write in other genres of both fiction and non-fiction. Some novelists are professional novelists, thus make a living wage, living writing novels and other fiction, while othe ...

s also gave valuable insights into the penal colonies

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer t ...

which helped form the country and also the early rural settlements.

In 1838 ''The Guardian: a tale'' by Anna Maria Bunn was published in Sydney. It was the first Australian novel printed and published in mainland Australia and the first Australian novel written by a woman. It is a Gothic

Gothic or Gothics may refer to:

People and languages

*Goths or Gothic people, the ethnonym of a group of East Germanic tribes

**Gothic language, an extinct East Germanic language spoken by the Goths

**Crimean Gothic, the Gothic language spoken b ...

romance.

Miles Franklin

Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin (14 October 187919 September 1954), known as Miles Franklin, was an Australian writer and feminist who is best known for her novel '' My Brilliant Career'', published by Blackwoods of Edinburgh in 1901. While ...

(''My Brilliant Career

''My Brilliant Career'' is a 1901 novel written by Miles Franklin. It is the first of many novels by Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin (1879–1954), one of the major Australian writers of her time. It was written while she was still a teenage ...

'') and Jeannie Gunn

Jeannie Gunn (pen name, Mrs Aeneas Gunn) (5 June 18709 June 1961) was an Australian novelist, teacher and Returned and Services League of Australia (RSL) volunteer.

Life

Jeannie Taylor was born in Carlton, Melbourne, the last of five childr ...

(''We of the Never Never

''We of the Never Never'' is an autobiographical novel by Jeannie Gunn first published in 1908. Although published as a novel, it is an account of the author's experiences in 1902 at Elsey Station near Mataranka, Northern Territory in which sh ...

'') wrote of lives of European pioneers in the Australian bush from a female perspective. Albert Facey

Albert Barnett Facey (31 August 1894 – 11 February 1982), publishing as A.B. Facey was an Australian writer and World War I veteran, whose main work was his autobiography, '' A Fortunate Life'', now considered a classic of Australian litera ...

wrote of the experiences of the Goldfields and of Gallipoli (''A Fortunate Life

''A Fortunate Life'' is an autobiography by Albert Facey published in 1981, nine months before his death. It chronicles his early life in Western Australia, his experiences as a private during the Gallipoli campaign of World War I and his return ...

''). Ruth Park

Rosina Ruth Lucia Park AM (24 August 191714 December 2010) was a New Zealand–born Australian author. Her best known works are the novels '' The Harp in the South'' (1948) and '' Playing Beatie Bow'' (1980), and the children's radio serial '' ...

wrote of the sectarian divisions of life in impoverished 1940s inner city Sydney (''The Harp in the South

''The Harp in the South'' is the debut novel by Australian author Ruth Park. Published in 1948, it portrays the life of a Catholic Irish Australian family living in the Sydney suburb of Surry Hills, which was at that time an inner city slum.

...

''). The experience of Australian PoWs

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of ...

in the Pacific War is recounted by Nevil Shute

Nevil Shute Norway (17 January 189912 January 1960) was an English novelist and aeronautical engineer who spent his later years in Australia. He used his full name in his engineering career and Nevil Shute as his pen name, in order to protect ...

in ''A Town Like Alice

''A Town Like Alice'' (United States title: ''The Legacy'') is a romance novel by Nevil Shute, published in 1950 when Shute had newly settled in Australia. Jean Paget, a young Englishwoman, becomes romantically interested in a fellow prisoner ...

'' and in the autobiography of Sir Edward Dunlop

Colonel Sir Ernest Edward "Weary" Dunlop, (12 July 1907 – 2 July 1993) was an Australian surgeon who was renowned for his leadership while being held prisoner by the Japanese during World War II.

Early life and family

Dunlop was born in Wa ...

. Alan Moorehead

Alan McCrae Moorehead, (22 July 1910 – 29 September 1983) was a war correspondent and author of popular histories, most notably two books on the nineteenth-century exploration of the Nile, ''The White Nile'' (1960) and ''The Blue Nile'' (196 ...

was an Australian war correspondent and novelist who gained international acclaim.

A number of notable classic works by international writers deal with Australian subjects, among them D. H. Lawrence

David Herbert Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English writer, novelist, poet and essayist. His works reflect on modernity, industrialization, sexuality, emotional health, vitality, spontaneity and instinct. His best-k ...

's ''Kangaroo

Kangaroos are four marsupials from the family Macropodidae (macropods, meaning "large foot"). In common use the term is used to describe the largest species from this family, the red kangaroo, as well as the antilopine kangaroo, eastern ...

''. The journals of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

contain the famous naturalist's first impressions of Australia, gained on his tour aboard the Beagle that inspired his writing of On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

. ''The Wayward Tourist: Mark Twain's Adventures in Australia'' contains the acclaimed American humourist's musings on Australia from his 1895 lecture tour.

In 2012, ''The Age

''The Age'' is a daily newspaper in Melbourne, Australia, that has been published since 1854. Owned and published by Nine Entertainment, ''The Age'' primarily serves Victoria, but copies also sell in Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territo ...

'' reported that Text Publishing was releasing an Australian classics series in 2012, to address a "neglect of Australian literature" by universities and "British dominated" publishing houses—citing out of print Miles Franklin award winners such as David Ireland's ''The Glass Canoe'' and Sumner Locke Elliott

Sumner Locke Elliott (17 October 191724 June 1991) was an Australian (later American) novelist and playwright.

Biography

Elliott was born in Sydney to the writer Sumner Locke and the journalist Henry Logan Elliott. His mother died of eclamp ...

's ''Careful, He Might Hear You'' as key examples.

Children's literature

Ethel Turner

Ethel Turner (24 January 1870 – 8 April 1958) was an English-born Australian novelist and children's literature writer.

Life

She was born Ethel Mary Burwell in Doncaster in England. Her father died when she was two, leaving her mother Sarah J ...

's ''Seven Little Australians

''Seven Little Australians'' is a classic Australian children's literature novel by Ethel Turner, published in 1894. Set mainly in Sydney in the 1880s, it relates the adventures of the seven mischievous Woolcot children, their stern army father ...

'', which relates the adventures of seven mischievous children in Sydney, has been in print since 1894, longer than any other Australian children's novel. ''The Getting of Wisdom

''The Getting of Wisdom'' is a novel by Australian novelist Henry Handel Richardson. It was first published in 1910, and has almost always been in print ever since.

Plot introduction

Henry Handel Richardson was the pseudonym of Ethel Florenc ...

'' (1910) by Henry Handel Richardson

Ethel Florence Lindesay Richardson (3 January 187020 March 1946), known by her pen name Henry Handel Richardson, was an Australian author.

Life

Born in East Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, into a prosperous family that later fell on hard tim ...

, about an unconventional schoolgirl in Melbourne, has enjoyed a similar success and been praised by H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

A generation of leading contemporary international writers who left Australia for Britain and the United States in the 1960s have remained regular and passionate contributors of Australian themed literary works throughout their careers including:

A generation of leading contemporary international writers who left Australia for Britain and the United States in the 1960s have remained regular and passionate contributors of Australian themed literary works throughout their careers including:

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Germaine Greer

Germaine Greer (; born 29 January 1939) is an Australian writer and public intellectual, regarded as one of the major voices of the radical feminist movement in the latter half of the 20th century.

Specializing in English and women's literatu ...

.

Other perennial favourites of Australian children's literature include Dorothy Wall's '' Blinky Bill'', Ethel Pedley

Ethel Charlotte Pedley (19 June 1859 – 6 August 1898) was an English-Australian author and musician. Early life

Ethel Charlotte Pedley was born on 19 June 1859 at Acton, near London. She was the daughter of Frederick Pedley and his wife E ...

's ''Dot and the Kangaroo

''Dot and the Kangaroo'' is an 1899 Australian children's book written by Ethel C. Pedley about a little girl named Dot who gets lost in the Australian outback and is eventually befriended by a kangaroo and several other marsupials. The book wa ...

'', May Gibbs

Cecilia May Gibbs MBE (17 January 1877 – 27 November 1969) was an Australian children's author, illustrator, and cartoonist. She is best known for her gumnut babies (also known as "bush babies" or "bush fairies"), and the book '' Snugglepot ...

' ''Snugglepot and Cuddlepie

''Snugglepot and Cuddlepie'' is a series of books written by Australian author May Gibbs. The books chronicle the adventures of the eponymous Snugglepot and Cuddlepie. The central story arc concerns Snugglepot and Cuddlepie (who are essentially ...

'', Norman Lindsay

Norman Alfred William Lindsay (22 February 1879 – 21 November 1969) was an Australian artist, etcher, sculptor, writer, art critic, novelist, cartoonist and amateur boxer. One of the most prolific and popular Australian artists of his genera ...

's ''The Magic Pudding

''The Magic Pudding: Being The Adventures of Bunyip Bluegum and his friends Bill Barnacle and Sam Sawnoff'' is a 1918 Australian children's book written and illustrated by Norman Lindsay. It is a comic fantasy, and a classic of Australian childr ...

'', Ruth Park

Rosina Ruth Lucia Park AM (24 August 191714 December 2010) was a New Zealand–born Australian author. Her best known works are the novels '' The Harp in the South'' (1948) and '' Playing Beatie Bow'' (1980), and the children's radio serial '' ...

's ''The Muddleheaded Wombat

The Muddle-Headed Wombat is a fictional wombat featured in the radio serials and later in the children's books of the same name written by Australian author Ruth Park. The books are considered classics of Australian children's literature.

History ...

'' and Mem Fox

Merrion Frances "Mem" Fox, AM (born Merrion Frances Partridge; 5 March 1946) is an Australian writer of children's books and an educationalist specialising in literacy. Fox has been semi-retired since 1996, but she still gives seminars and ...

's ''Possum Magic

''Possum Magic'' is a 1983 Children's picture book by Australian author Mem Fox, and illustrated by Julie Vivas. It concerns a young female possum, named Hush, who becomes invisible and has a number of adventures. In 2001, a film was made by the ...

''. These classic works employ anthropomorphism to bring alive the creatures of the Australian bush

"The bush" is a term mostly used in the English vernacular of Australia and New Zealand where it is largely synonymous with ''backwoods'' or '' hinterland'', referring to a natural undeveloped area. The fauna and flora contained within this ...

, thus Bunyip Bluegum of ''The Magic Pudding'' is a koala who leaves his tree in search of adventure, while in ''Dot and the Kangaroo'' a little girl lost in the bush is befriended by a group of marsupials

Marsupials are any members of the mammalian infraclass Marsupialia. All extant marsupials are endemic to Australasia, Wallacea and the Americas. A distinctive characteristic common to most of these species is that the young are carried in a ...

. May Gibbs crafted a story of protagonists modelled on the appearance of young eucalyptus (gum tree

Gum tree is a common name for smooth-barked trees and shrubs in several genera:

*Eucalypteae, particularly:

**''Eucalyptus'', which includes the majority of species of gum trees.

**''Corymbia'', which includes the ghost gums and spotted gums.

**' ...

) nuts and pitted these ''gumnut babies'', Snugglepot and Cuddlepie, against the antagonist Banksia men. Gibbs' influence has lasted through the generations – contemporary children's author Ursula Dubosarsky

Ursula Dubosarsky (born ''Ursula Coleman''; 1961 in Sydney) is an Australian writer of fiction and non-fiction for children and young adults, whose work is characterised by a child's vision and comic voice of both clarity and ambiguity. She ha ...

has cited ''Snugglepot and Cuddlepie'' as one of her favourite books.

In the middle of the twentieth century, children's literature languished, with popular British authors dominating the Australian market. But in the 1960s Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print book ...

published several Australian children's authors, and Angus & Robertson

Angus & Robertson (A&R) is a major Australian bookseller, publisher and printer. As book publishers, A&R has contributed substantially to the promotion and development of Australian literature.Alison, Jennifer (2001). "Publishers and editors: A ...

appointed their first specialist children's editor. The best-known writers to emerge in this period were Hesba Brinsmead

Hesba Fay Brinsmead (''Hesba Fay Hungerford''; 15 March 1922 in Berambing, New South Wales – 24 November 2003 in Murwillumbah) was an Australian author of children's books and an environmentalist.

Biography

Upbringing

Brinsmead's parent ...

, Ivan Southall

Ivan Francis Southall AM, DFC (8 June 192115 November 2008) was an Australian writer best known for young adult fiction. He wrote more than 30 children's books, six books for adults, and at least ten works of history, biography or other non-fi ...

, Colin Thiele

Colin Milton Thiele AC (; 16 November 1920 – 4 September 2006) was an Australian author and educator. He was renowned for his award-winning children's fiction, most notably the novels '' Storm Boy'', '' Blue Fin'', the '' Sun on the Stubble'' ...

, Patricia Wrightson

Patricia Wrightson OBE (19 June 1921 – 15 March 2010) was an Australian writer of several highly regarded and influential children's books. Employing a 'magic realism' style, her books, including the award-winning ''The Nargun and the Stars' ...

, Nan Chauncy

Nan Chauncy (28 May 1900 – 1 May 1970) was a British-born Australian children's writer.

Early life

Chauncy was born Nancen Beryl Masterman in Northwood, Middlesex (now in London), and emigrated to Tasmania, Australia, with her family in 19 ...

, Joan Phipson

Joan Margaret Phipson AM (1912–2003) was an Australian children's writer. She lived on a farm in the Central Tablelands of New South Wales and many of her books evoke the stress and satisfaction of living in the Australian countryside, flood ...

and Eleanor Spence, their works primarily set in the Australian landscape. In 1971, Southall won the Carnegie Medal for ''Josh

Josh is a masculine given name, frequently a diminutive ( hypocorism) of the given names Joshua or Joseph, though since the 1970s, it has increasingly become a full name on its own. It may refer to:

People A–J

* "Josh", an early pseudonym o ...

''. In 1986, Patricia Wrightson received the international Hans Christian Andersen Award

The Hans Christian Andersen Awards are two literary awards given by the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), recognising one living author and one living illustrator for their "lasting contribution to children's literature". The ...

.

The Children's Book Council of Australia

The Children's Book Council of Australia (CBCA) is a not for profit organisation which aims to engage the community with literature for young Australians. The CBCA presents the annual Children's Book of the Year Awards to books of literary merit ...

has presented annual awards for books of literary merit since 1946 and has other awards for outstanding contributions to Australian children's literature. Notable winners and shortlisted works have inspired several well-known Australian films from original novels, including the Silver Brumby series, a collection by Elyne Mitchell

Elyne Mitchell, OAM (née Chauvel, 30 December 1913 – 4 March 2002) was an Australian author noted for the ''Silver Brumby'' series of children's novels. Her nonfiction works draw on family history and culture.

Biography

Sybil Elyne Keith Ch ...

which recount the life and adventures of Thowra, a Snowy Mountains brumby, brumby stallion; ''Storm Boy (novel), Storm Boy'' (1964), by Colin Thiele, about a boy and his pelican and the relationships he has with his father, the pelican, and an outcast Aboriginal man called Fingerbone; the Sydney-based Victorian era time travel adventure ''Playing Beatie Bow (film), Playing Beatie Bow'' (1980) by Ruth Park

Rosina Ruth Lucia Park AM (24 August 191714 December 2010) was a New Zealand–born Australian author. Her best known works are the novels '' The Harp in the South'' (1948) and '' Playing Beatie Bow'' (1980), and the children's radio serial '' ...

; and, for older children and mature readers, Melina Marchetta

Carmelina Marchetta (born 25 March 1965) is an Australian writer and teacher. Marchetta is best known as the author of teen novels, '' Looking for Alibrandi'', ''Saving Francesca'' and ''On the Jellicoe Road''. She has twice been awarded the CB ...

's 1993 novel about a Sydney high school girl '' Looking for Alibrandi''. Robin Klein's ''Came Back to Show You I Could Fly'' is a story about the beautiful relationship between an eleven-year-old boy and an older, drug-addicted girl.

Jackie French, widely described as Australia's most popular children's author, has written about 170 books, including two Children's Book Council of Australia, CBCA Children's Book of the Year Award winners. One of them, the critically acclaimed ''Hitler's Daughter'' (1999), is a "what if?" story that explores mind-provoking issues about what would have happened if Adolf Hitler had had a daughter. French is also the author of the highly praised ''Diary of a Wombat'' (2003), which won awards such as the 2003 COOL Award and 2004 BILBY Award, among others. It was also named an honour book for the Children's Book Council of Australia, CBCA Children's Book of the Year Award: Picture Book, Children's Book of the Year Award for picture books.

Paul Jennings (Australian author), Paul Jennings is a prolific writer of contemporary Australian fiction for young people whose career began with collections of short stories such as ''Unreal (book), Unreal!'' (1985) and ''Unbelievable (book), Unbelievable!'' (1987); many of the stories were adapted as episodes of the award-winning television show ''Round the Twist''.

The world's richest prize in children's literature has been received by two Australians, Sonya Hartnett, who won the 2008 Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award and Shaun Tan, who won in 2011. Hartnett has a long and distinguished career, publishing her first novel at 15. She is known for her dark and often controversial themes. She has won several awards, including the Kathleen Mitchell Award and the Victorian Premier's Award for ''Sleeping Dogs'', Guardian Children's Fiction Prize and the Aurealis Award, Best Young Adult Novel (Australian speculative fiction) for ''Thursday's Child'' and the CBCA Children's Book of the Year Award: Older Readers for ''Forest''. Tan won this for his career contribution to "children's and young adult literature in the broadest sense". Tan has been awarded various literary awards, including the Deutscher Jugendliteraturpreis in 2009 for ''Tales from Outer Suburbia'' and a New York Times Best Illustrated Children's Books award in 2007 for ''The Arrival''. Alongside his numerous literary awards, Tan's adaption of his book ''The Lost Thing'' also won him an Oscar for best animated short film. Other awards Tan has won include a World Fantasy Award for Best Artist, and a Hugo Award for Hugo Award for Best Professional Artist, Best Professional Artist.

Expatriate authors

A generation of leading contemporary international writers who left Australia for Britain and the United States in the 1960s have remained regular and passionate contributors of Australian themed literary works throughout their careers including:

A generation of leading contemporary international writers who left Australia for Britain and the United States in the 1960s have remained regular and passionate contributors of Australian themed literary works throughout their careers including: Clive James

Clive James (born Vivian Leopold James; 7 October 1939 – 24 November 2019) was an Australian critic, journalist, broadcaster, writer and lyricist who lived and worked in the United Kingdom from 1962 until his death in 2019.Robert Hughes,

Grunge Fiction

, ''The Literary Encyclopedia'', 6 November 2008, accessed 9 September 2009 The term "grunge" is from the 1990s-era Grunge, music genre of grunge. The genre was first coined in 1995 following the success of Andrew McGahan's first novel ''Praise'' which had been released in 1991 and became popular with sub-30-year-old readers, a previously under-investigated demographic. Other authors considered to be "grunge lit" include Linda Jaivin, Fiona McGregor and Justine Ettler. Since its invention, the term "grunge lit" has been retrospectively applied to novels written as early as 1977, namely

History has been an important discipline in the development of Australian writing.

History has been an important discipline in the development of Australian writing.

A complicated, multi-faceted relationship to Australia is displayed in much Australian writing, often through writing about landscape. Barbara Baynton's short stories from the late 19th century/early 20th century convey people living in the bush, a landscape that is alive but also threatening and alienating. Kenneth Cook's ''Wake in Fright'' (1961) portrayed the outback as a nightmare with a blazing sun, from which there is no escape.

A complicated, multi-faceted relationship to Australia is displayed in much Australian writing, often through writing about landscape. Barbara Baynton's short stories from the late 19th century/early 20th century convey people living in the bush, a landscape that is alive but also threatening and alienating. Kenneth Cook's ''Wake in Fright'' (1961) portrayed the outback as a nightmare with a blazing sun, from which there is no escape.  What it means to be Australian is another issue that Australian literature explores.

What it means to be Australian is another issue that Australian literature explores.

Poetry played an important part in early Australian literature. The first poet to be published in Australia was Michael Massey Robinson (1744-1826), convict and public servant, whose odes appeared in Sydney Gazette, ''The Sydney Gazette''. Charles Harpur and Henry Kendall (poet), Henry Kendall were the first poets of any consequence.

Poetry played an important part in early Australian literature. The first poet to be published in Australia was Michael Massey Robinson (1744-1826), convict and public servant, whose odes appeared in Sydney Gazette, ''The Sydney Gazette''. Charles Harpur and Henry Kendall (poet), Henry Kendall were the first poets of any consequence.

Other poets who reflected a sense of Australian identity include C J Dennis and Dorothea McKellar. Dennis wrote in the Australian vernacular ("The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke"), while McKellar wrote the iconic patriotic poem "

Other poets who reflected a sense of Australian identity include C J Dennis and Dorothea McKellar. Dennis wrote in the Australian vernacular ("The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke"), while McKellar wrote the iconic patriotic poem " Contemporary Australian poetry is mostly published by small, independent book publishers. However, other kinds of publication, including new media and online journals, spoken word and live events, and public poetry projects are gaining an increasingly vibrant and popular presence. 1992–1999 saw poetry and art collaborations in Sydney and Newcastle buses and ferries, including Artransit from Meuse Press. Some of the more interesting and innovative contributions to Australian poetry have emerged from artist-run galleries in recent years, such as Textbase which had its beginnings as part of the 1st Floor gallery in Fitzroy. In addition, Red Room Company is a major exponent of innovative projects. Bankstown Poetry Slam has become a notable venue for spoken-word poetry and for community intersection with poetry as an art form to be shared. With its roots in Western Sydney it has a strong following from first and second generation Australians, often giving a platform to voices that are more marginalised in mainstream Australian society.

Contemporary Australian poetry is mostly published by small, independent book publishers. However, other kinds of publication, including new media and online journals, spoken word and live events, and public poetry projects are gaining an increasingly vibrant and popular presence. 1992–1999 saw poetry and art collaborations in Sydney and Newcastle buses and ferries, including Artransit from Meuse Press. Some of the more interesting and innovative contributions to Australian poetry have emerged from artist-run galleries in recent years, such as Textbase which had its beginnings as part of the 1st Floor gallery in Fitzroy. In addition, Red Room Company is a major exponent of innovative projects. Bankstown Poetry Slam has become a notable venue for spoken-word poetry and for community intersection with poetry as an art form to be shared. With its roots in Western Sydney it has a strong following from first and second generation Australians, often giving a platform to voices that are more marginalised in mainstream Australian society.

The Australian Poetry Library contains a wide range of Australian poetry as well as critical and contextual material relating to them, such as interviews, photographs and audio/visual recordings. it contains over 42,000 poems, from more than 170 Australian poets. Begun in 2004 by leading Australian poet John Tranter, it is a joint initiative of the University of Sydney and the Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) with funding by the Australian Research Council.

The Australian Poetry Library contains a wide range of Australian poetry as well as critical and contextual material relating to them, such as interviews, photographs and audio/visual recordings. it contains over 42,000 poems, from more than 170 Australian poets. Begun in 2004 by leading Australian poet John Tranter, it is a joint initiative of the University of Sydney and the Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) with funding by the Australian Research Council.

/ref> Two centuries later, the extraordinary circumstances of the foundations of Australian theatre were recounted in ''Our Country's Good'' by Timberlake Wertenbaker: the participants were prisoners watched by sadistic guards and the leading lady was under threat of the death penalty. The play is based on

The Home of Australian Playscripts , AustralianPlays.org

that aims to combine playwright biographies and script information. Scripts are also available there.

Library of Australiana

page a

Project Gutenberg of Australia

Bibliography of Australian Literature to 1954

a

Freeread

"AustLit: The Australian Literature Resource" (2000-)

List of Australian Writers in English

{{Authority control Australian literature, English-language literature

Barry Humphries

John Barry Humphries (born 17 February 1934) is an Australian comedian, actor, author and satirist. He is best known for writing and playing his on-stage and television alter egos Dame Edna Everage and Sir Les Patterson. He is also a film pro ...

, Geoffrey Robertson and Germaine Greer

Germaine Greer (; born 29 January 1939) is an Australian writer and public intellectual, regarded as one of the major voices of the radical feminist movement in the latter half of the 20th century.

Specializing in English and women's literatu ...

. Several of these writers had links to the Sydney Push intellectual sub-culture in Sydney from the late 1940s to the early 1970s; and to ''Oz (magazine), Oz'', a satirical magazine originating in Sydney, and later produced in London (from 1967 to 1973).

After a long media career, Clive James remained as a leading humourist and author based in Britain whose memoir series was rich in reflections on Australian society (including his 2007 book ''Cultural Amnesia (book), Cultural Amnesia''). Robert Hughes has produced a number of historical works on Australia (including ''The Art of Australia'' (1966) and ''The Fatal Shore'' (1987)).

Barry Humphries took his dadaist Absurdist fiction, absurdist theatrical talents and pen to London in the 1960s, becoming an institution on British television and later attaining popularity in the USA. Humphries' outlandish Australian caricatures, including Dame Edna Everage, Barry McKenzie and Les Patterson have starred in books, stage and screen to great acclaim over five decades and his biographer Anne Pender described him in 2010 as the most significant comedian since Charles Chaplin. His own literary works include the Dame Edna biographies ''My Gorgeous Life'' (1989) and ''Handling Edna'' (2010) and the autobiography ''My Life As Me: A Memoir'' (2002). Geoffrey Robertson King's Counsel, KC is a leading international human rights lawyer, academic, author and broadcaster whose books include ''The Justice Game'' (1998) and ''Crimes Against Humanity'' (1999). Leading feminist Germaine Greer, author of ''The Female Eunuch'', has spent much of her career in England but continues to study, critique, condemn and adore her homeland (recent work includes ''Whitefella Jump Up: The Shortest Way to Nationhood'', 2004).

Other contemporary works and authors

Martin Boyd (1893–1972) was a distinguished memoirist, novelist and poet, whose works included social comedies and the serious reflections of a pacifist faced with a time of war. Among his Langton series of novels—''The Cardboard Crown'' (1952), ''A Difficult Young Man'' (1955), ''Outbreak of Love'' (1957)—earned high praise in Britain and the United States, though despite their Australian themes, were largely ignored in Australia.Patrick White

Patrick Victor Martindale White (28 May 1912 – 30 September 1990) was a British-born Australian writer who published 12 novels, three short-story collections, and eight plays, from 1935 to 1987.

White's fiction employs humour, florid prose, ...