Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

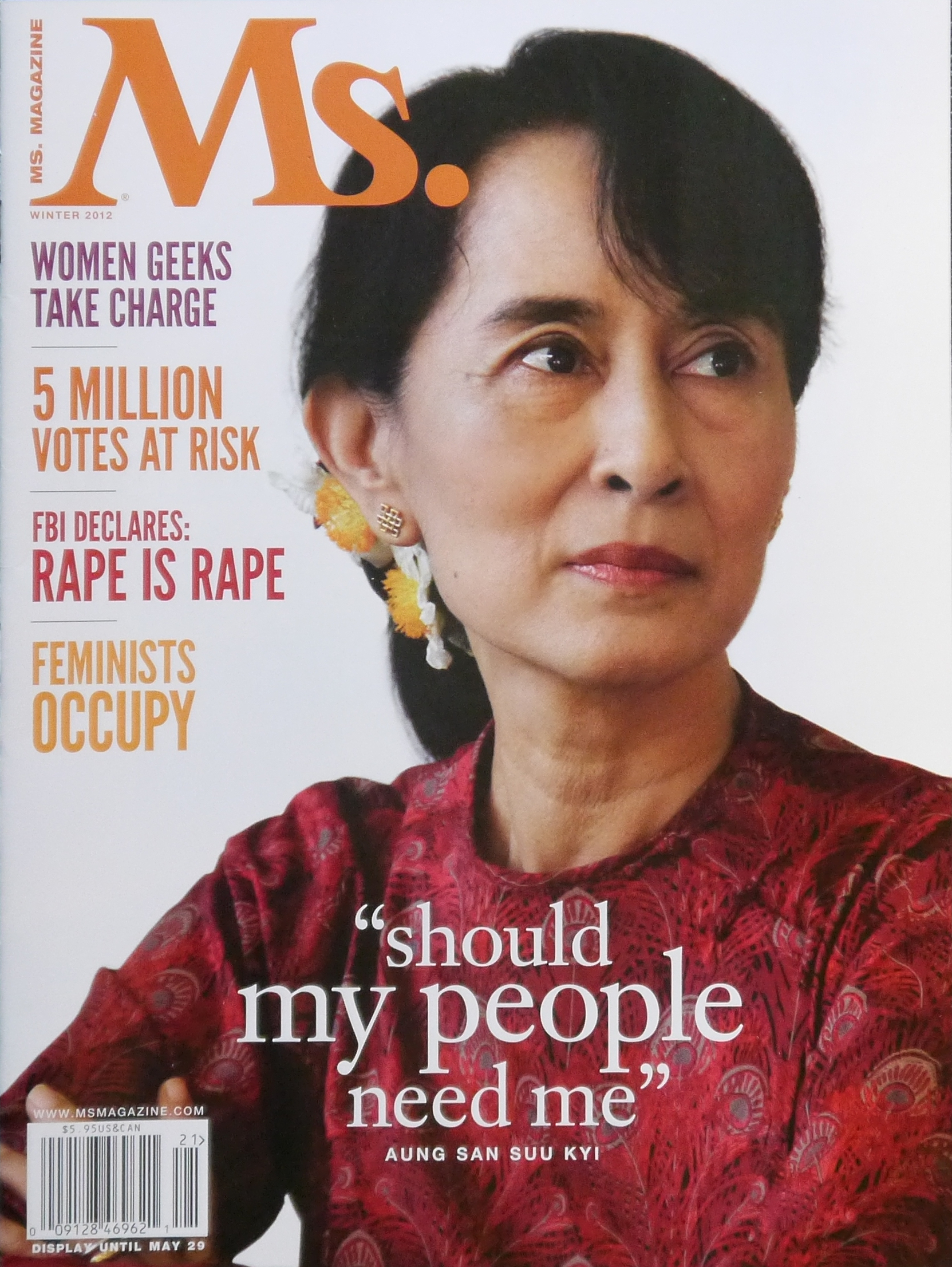

laureate who served as State Counsellor of Myanmar (equivalent to a prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

) and Minister of Foreign Affairs

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between coun ...

from 2016 to 2021. She has served as the chairperson of the National League for Democracy

The National League for Democracy ( my, အမျိုးသား ဒီမိုကရေစီ အဖွဲ့ချုပ်, ; abbr. NLD; Burmese abbr. ဒီချုပ်) is a liberal democratic political party in Myanmar (Burma). It ...

(NLD) since 2011, having been the general secretary from 1988 to 2011. She played a vital role in Myanmar

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

's transition from military junta to partial democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

in the 2010s.

The youngest daughter of Aung San

Aung San (, ; 13 February 191519 July 1947) was a Burmese politician, independence activist and revolutionary. He was instrumental in Myanmar's struggle for independence from British rule, but he was assassinated just six months before his goa ...

, Father of the Nation

The Father of the Nation is an honorific title given to a person considered the driving force behind the establishment of a country, state, or nation. (plural ), also seen as , was a Roman honorific meaning the "Father of the Fatherland", b ...

of modern-day Myanmar, and Khin Kyi, Aung San Suu Kyi was born in Rangoon

Yangon ( my, ရန်ကုန်; ; ), formerly spelled as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar (also known as Burma). Yangon served as the capital of Myanmar until 2006, when the military governme ...

, British Burma. After graduating from the University of Delhi

Delhi University (DU), formally the University of Delhi, is a collegiate central university located in New Delhi, India. It was founded in 1922 by an Act of the Central Legislative Assembly and is recognized as an Institute of Eminence (IoE ...

in 1964 and

St Hugh's College, Oxford

St Hugh's College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford. It is located on a site on St Margaret's Road, to the north of the city centre. It was founded in 1886 by Elizabeth Wordsworth as a women's college, and accep ...

in 1968, she worked at the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizi ...

for three years. She married Michael Aris

Michael Vaillancourt Aris (27 March 1946 – 27 March 1999) was an English historian who wrote and lectured on Bhutanese, Tibetan and Himalayan culture and history. He was the husband of Aung San Suu Kyi, who would later become State Counsello ...

in 1972, with whom she had two children.

Aung San Suu Kyi rose to prominence in the 8888 Uprising

The 8888 Uprising ( my, ၈၈၈၈ အရေးအခင်း), also known as the People Power UprisingYawnghwe (1995), pp. 170 and the 1988 Uprising, was a series of nationwide protests, marches, and riots in Burma (present-day Myanmar) th ...

of 8 August 1988 and became the General Secretary of the NLD, which she had newly formed with the help of several retired army officials who criticized the military junta. In the 1990 elections, NLD won 81% of the seats in Parliament, but the results were nullified, as the military government (the State Peace and Development Council

The State Peace and Development Council ( my, နိုင်ငံတော် အေးချမ်းသာယာရေး နှင့် ဖွံ့ဖြိုးရေး ကောင်စီ ; abbreviated SPDC or , ) was the offi ...

– SPDC) refused to hand over power, resulting in an international outcry. She had been detained before the elections and remained under house arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if ...

for almost 15 of the 21 years from 1989 to 2010, becoming one of the world's most prominent political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their politics, political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, al ...

s. In 1999, ''Time'' magazine named her one of the "Children of Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

" and his spiritual heir to nonviolence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

. She survived an assassination attempt in the 2003 Depayin massacre when at least 70 people associated with the NLD were killed.

Her party boycotted the 2010 elections

The following elections occurred in the year 2010.

{{TOC right

* National electoral calendar 2010

* Local electoral calendar 2010

* 2010 United Nations Security Council election

Africa

* 2010 Burkinabé presidential election

* 2010 Burundian Sen ...

, resulting in a decisive victory for the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party

The Union Solidarity and Development Party ( my, ပြည်ထောင်စုကြံ့ခိုင်ရေးနှင့် ဖွံ့ဖြိုးရေးပါတီ; abbr. USDP) is a political party in Myanmar, registered on ...

(USDP). Aung San Suu Kyi became a Pyithu Hluttaw

The Pyithu Hluttaw ( my, ပြည်သူ့ လွှတ်တော်, ; House of Representatives) is the ''de jure'' lower house of the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, the bicameral legislature of Myanmar (Burma). It consists of 440 members, of wh ...

MP while her party won 43 of the 45 vacant seats in the 2012 by-elections. In the 2015 elections

The following elections were scheduled to occur in the year 2015.

Africa

* 2015 Beninese parliamentary election 26 April 2015

* 2015 Burkinabé general election 29 November 2015

* 2015 Burundian legislative election 29 June 2015

* 2015 Burundi ...

, her party won a landslide victory

A landslide victory is an election result in which the victorious candidate or party wins by an overwhelming margin. The term became popular in the 1800s to describe a victory in which the opposition is "buried", similar to the way in which a geol ...

, taking 86% of the seats in the Assembly of the Union

The Pyidaungsu Hluttaw ( my, ပြည်ထောင်စု လွှတ်တော် lit. Assembly of the Union) is the ''de jure'' national-level bicameral legislature of Myanmar (officially known as the ''Republic of the Union of My ...

—well more than the 67% supermajority

A supermajority, supra-majority, qualified majority, or special majority is a requirement for a proposal to gain a specified level of support which is greater than the threshold of more than one-half used for a simple majority. Supermajority r ...

needed to ensure that its preferred candidates were elected president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese f ...

and second vice president in the presidential electoral college. Although she was prohibited from becoming the president due to a clause in the constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

—her late husband and children are foreign citizens—she assumed the newly created role of State Counsellor of Myanmar, a role akin to a prime minister or a head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, ...

.

When she ascended to the office of state counsellor, Aung San Suu Kyi drew criticism from several countries, organisations and figures over Myanmar's inaction in response to the genocide of the Rohingya people in Rakhine State

Rakhine State (; , , ; formerly known as Arakan State) is a state in Myanmar (Burma). Situated on the western coast, it is bordered by Chin State to the north, Magway Region, Bago Region and Ayeyarwady Region to the east, the Bay of Ben ...

and refusal to acknowledge that Myanmar's military has committed massacres. Under her leadership, Myanmar also drew criticism for prosecutions of journalists. In 2019, Aung San Suu Kyi appeared in the International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice (ICJ; french: Cour internationale de justice, links=no; ), sometimes known as the World Court, is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN). It settles disputes between states in accordanc ...

where she defended the Burmese military against allegations of genocide against the Rohingya

The Rohingya people () are a stateless Indo-Aryan ethnic group who predominantly follow Islam and reside in Rakhine State, Myanmar (previously known as Burma). Before the Rohingya genocide in 2017, when over 740,000 fled to Bangladesh, a ...

.

Aung San Suu Kyi, whose party had won the November 2020 Myanmar general election

General elections were held in Myanmar on 8 November 2020. Voting occurred in all constituencies, excluding seats appointed by or reserved for the military, to elect members to both the upper house - Amyotha Hluttaw (the House of Nationalities ...

, was arrested on 1 February 2021 following a coup d'état that returned the Tatmadaw

Tatmadaw (, , ) is the official name of the armed forces of Myanmar (formerly Burma). It is administered by the Ministry of Defence and composed of the Myanmar Army, the Myanmar Navy and the Myanmar Air Force. Auxiliary services include t ...

(Myanmar Armed Forces) to power and sparked protests across the country. Several charges were filed against her, and on 6 December 2021, she was sentenced to four years in prison on two of them. Later, on 10 January 2022, she was sentenced to an additional four years on another set of charges. By 12 October 2022, she had been convicted to 26 years imprisonment on ten charges in total, including five corruption charges. The United Nations, most European countries, and the United States condemned the arrests, trials, and sentences as politically motivated.

Name

''Aung San Suu Kyi'', like otherBurmese names

Burmese names lack the serial structure of most Western names. The Burmans have no customary matronymic or patronymic system and thus there is no surname at all. In the culture of Myanmar, people can change their name at will, often with no g ...

, includes no surname, but is only a personal name, in her case derived from three relatives: "Aung San

Aung San (, ; 13 February 191519 July 1947) was a Burmese politician, independence activist and revolutionary. He was instrumental in Myanmar's struggle for independence from British rule, but he was assassinated just six months before his goa ...

" from her father, "Suu" from her paternal grandmother, and "Kyi" from her mother Khin Kyi.Aung San Suu Kyi – BiographyNobel Prize Foundation In Myanmar, Aung San Suu Kyi is often referred to as ''Daw'' Aung San Suu Kyi. ''Daw'', literally meaning "aunt", is not part of her name but is an

honorific

An honorific is a title that conveys esteem, courtesy, or respect for position or rank when used in addressing or referring to a person. Sometimes, the term "honorific" is used in a more specific sense to refer to an honorary academic title. It ...

for any older and revered woman, akin to " Madam". She is sometimes addressed as Daw Suu or Amay Suu ("Mother Suu") by her supporters.Aung San Suu Kyi should lead Burma, ''Pravda Online'' 25 September 2007The Next United Nations Secretary-General: Time for a Woman

Equality Now

Equality Now is a non-governmental organization founded in 1992 to advocate for the protection and promotion of the human rights of women and girls. Through a combination of regional partnerships, community mobilization and legal advocacy the or ...

.org November 2005MPs to Suu Kyi: You are the real PM of Burma. ''

The Times of India

''The Times of India'', also known by its abbreviation ''TOI'', is an Indian English language, English-language daily newspaper and digital news media owned and managed by The Times Group. It is the List of newspapers in India by circulation, t ...

'' 13 June 2007Walsh, John (February 2006Letters from Burma

Shinawatra International UniversityDeutsche Welle

Article: Sentence for Burma's Aung San Suu Kyi sparks outrage and cautious hope Quote: The NLD won a convincing majority in elections in 1990, the last remotely fair vote in Burma. That would have made Aung San Suu Kyi the prime minister, but the military leadership immediately nullified the result. Now her party must decide whether to take part in a poll that shows little prospect of being just

Personal life

Aung San Suu Kyi was born on 19 June 1945 in Rangoon (nowYangon

Yangon ( my, ရန်ကုန်; ; ), formerly spelled as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar (also known as Burma). Yangon served as the capital of Myanmar until 2006, when the military government ...

), British Burma. According to Peter Popham, she was born in a small village outside Rangoon called Hmway Saung. Her father, Aung San

Aung San (, ; 13 February 191519 July 1947) was a Burmese politician, independence activist and revolutionary. He was instrumental in Myanmar's struggle for independence from British rule, but he was assassinated just six months before his goa ...

, allied with the Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. Aung San founded the modern Burmese army and negotiated Burma's independence from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

in 1947; he was assassinated by his rivals in the same year. She is a niece of Thakin Than Tun

Thakin Than Tun ( my, သခင် သန်းထွန်း; 1911 – 24 September 1968) was a Burmese politician and leader of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) from 1945 until his assassination in 1968. He was uncle of the former State ...

who was the husband of Khin Khin Gyi, the elder sister of her mother Khin Kyi.

She grew up with her mother, Khin Kyi, and two brothers, Aung San Lin and Aung San Oo

Aung San Oo ( my, အောင်ဆန်းဦး, born in 1943) is a Burmese

engineer who is the elder brother of politician and Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi; the two are the only surviving children of Burmese independence lead ...

, in Rangoon

Yangon ( my, ရန်ကုန်; ; ), formerly spelled as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar (also known as Burma). Yangon served as the capital of Myanmar until 2006, when the military governme ...

. Aung San Lin died at the age of eight when he drowned in an ornamental lake on the grounds of the house. Her elder brother emigrated to San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

, California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the ...

, becoming a United States citizen

Citizenship of the United States is a legal status that entails Americans with specific rights, duties, protections, and benefits in the United States. It serves as a foundation of fundamental rights derived from and protected by the Constitut ...

. After Aung San Lin's death, the family moved to a house by Inya Lake

Inya Lake ( my, အင်းလျားကန်, ''ʔīnyā kǎn'' ; formerly, Lake Victoria) is the largest lake in Yangon, Burma (Myanmar), a popular recreational area for Yangonites, and a famous location for romance in popular culture. Loc ...

where Aung San Suu Kyi met people of various backgrounds, political views, and religions. She was educated in Methodist English High School (now Basic Education High School No. 1 Dagon) for much of her childhood in Burma, where she was noted as having a talent for learning languages. She speaks four languages: Burmese, English, French, and Japanese.Aung San Suu Kyi: A Biography, p. 142 She is a Theravada

''Theravāda'' () ( si, ථේරවාදය, my, ထေရဝါဒ, th, เถรวาท, km, ថេរវាទ, lo, ເຖຣະວາດ, pi, , ) is the most commonly accepted name of Buddhism's oldest existing school. The school' ...

Buddhist.

Aung San Suu Kyi's mother, Khin Kyi, gained prominence as a political figure in the newly formed Burmese government. She was appointed Burmese ambassador to India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

and Nepal

Nepal (; ne, नेपाल ), formerly the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal ( ne,

सङ्घीय लोकतान्त्रिक गणतन्त्र नेपाल ), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is ma ...

in 1960, and Aung San Suu Kyi followed her there. She studied in the Convent of Jesus and Mary School in New Delhi

New Delhi (, , ''Naī Dillī'') is the Capital city, capital of India and a part of the NCT Delhi, National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati B ...

, and graduated from Lady Shri Ram College

Lady Shri Ram College for Women (LSR) is a constituent women's college, affiliated with the University of Delhi, and has a legacy in women's education.

History

Established in 1956 in New Delhi by the late Lala Shri Ram in memory of his wife ...

, a constituent college of the University of Delhi

Delhi University (DU), formally the University of Delhi, is a collegiate central university located in New Delhi, India. It was founded in 1922 by an Act of the Central Legislative Assembly and is recognized as an Institute of Eminence (IoE ...

in New Delhi, with a degree in politics in 1964.A biography of Aung San Suu KyiBurma Campaign.co.uk Retrieved 7 May 2009 Suu Kyi continued her education at

St Hugh's College, Oxford

St Hugh's College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford. It is located on a site on St Margaret's Road, to the north of the city centre. It was founded in 1886 by Elizabeth Wordsworth as a women's college, and accep ...

, obtaining a B.A. degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics in 1967, graduating with a third-class degree

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

that was promoted per tradition to an MA in 1968. After graduating, she lived in New York City with family friend Ma Than E, who was once a popular Burmese pop singer. She worked at the United Nations for three years, primarily on budget matters, writing daily to her future husband, Dr. Michael Aris. On 1 January 1972, Aung San Suu Kyi and Aris, a scholar of Tibetan culture

Tibet developed a distinct culture due to its geographic and climatic conditions. While influenced by neighboring cultures from China, India, and Nepal, the Himalayan region's remoteness and inaccessibility have preserved distinct local ...

and literature, living abroad in Bhutan

Bhutan (; dz, འབྲུག་ཡུལ་, Druk Yul ), officially the Kingdom of Bhutan,), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is situated in the Eastern Himalayas, between China in the north and India in the south. A mountai ...

, were married. The following year, she gave birth to their first son, Alexander Aris, in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

; their second son, Kim, was born in 1977. Between 1985 and 1987, Aung San Suu Kyi was working toward a Master of Philosophy

The Master of Philosophy (MPhil; Latin ' or ') is a postgraduate degree. In the United States, an MPhil typically includes a taught portion and a significant research portion, during which a thesis project is conducted under supervision. An MPhil m ...

degree in Burmese literature as a research student at the School of Oriental and African Studies

SOAS University of London (; the School of Oriental and African Studies) is a public research university in London, England, and a member institution of the federal University of London. Founded in 1916, SOAS is located in the Bloomsbury are ...

(SOAS), University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degre ...

. She was elected as an Honorary Fellow of St Hugh's in 1990. For two years, she was a Fellow at the Indian Institute of Advanced Studies (IIAS) in Shimla

Shimla (; ; also known as Simla, List of renamed Indian cities and states#Himachal Pradesh, the official name until 1972) is the capital and the largest city of the States and union territories of India, northern Indian state of Himachal Prade ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

. She also worked for the government of the Union of Burma.

In 1988, Aung San Suu Kyi returned to Burma to tend for her ailing mother. Aris' visit in Christmas 1995 was the last time that he and Aung San Suu Kyi met, as she remained in Burma and the Burmese dictatorship denied him any further entry visas. Aris was diagnosed with prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is cancer of the prostate. Prostate cancer is the second most common cancerous tumor worldwide and is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality among men. The prostate is a gland in the male reproductive system that su ...

in 1997 which was later found to be terminal. Despite appeals from prominent figures and organizations, including the United States, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan

Kofi Atta Annan (; 8 April 193818 August 2018) was a Ghanaian diplomat who served as the seventh secretary-general of the United Nations from 1997 to 2006. Annan and the UN were the co-recipients of the 2001 Nobel Peace Prize. He was the found ...

and Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

, the Burmese government would not grant Aris a visa, saying that they did not have the facilities to care for him, and instead urged Aung San Suu Kyi to leave the country to visit him. She was at that time temporarily free from house arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if ...

but was unwilling to depart, fearing that she would be refused re-entry if she left, as she did not trust the military junta

A military junta () is a government led by a committee of military leaders. The term ''junta'' means "meeting" or "committee" and originated in the national and local junta organized by the Spanish resistance to Napoleon's invasion of Spain in ...

's assurance that she could return.

Aris died on his 53rd birthday on 27 March 1999. Since 1989, when his wife was first placed under house arrest, he had seen her only five times, the last of which was for Christmas in 1995. She was also separated from her children, who live in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, until 2011.

On 2 May 2008, after Cyclone Nargis

Extremely Severe Cyclonic Storm Nargis ( my, နာဂစ်, ur, نرگس ) was an extremely destructive and deadly tropical cyclone that caused the worst natural disaster in the recorded history of Myanmar during early May 2008. The cyclone ...

hit Burma, Aung San Suu Kyi's dilapidated lakeside bungalow lost its roof and electricity, while the cyclone also left entire villages in the Irrawaddy delta

The Irrawaddy Delta or Ayeyarwady Delta lies in the Irrawaddy Division, the lowest expanse of land in Myanmar that fans out from the limit of tidal influence at Myan Aung to the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea, to the south at the mouth of the ...

submerged. Plans to renovate and repair the house were announced in August 2009. Aung San Suu Kyi was released from house arrest on 13 November 2010.

Political career

Political beginning

Coincidentally, when Aung San Suu Kyi returned to Burma in 1988, the long-time military leader of Burma and head of theruling party

The ruling party or governing party in a democratic parliamentary or presidential system is the political party or coalition holding a majority of elected positions in a parliament, in the case of parliamentary systems, or holding the executi ...

, General Ne Win

Ne Win ( my, နေဝင်း ; 10 July 1910, or 14 or 24 May 1911 – 5 December 2002) was a Burmese politician and military commander who served as Prime Minister of Burma from 1958 to 1960 and 1962 to 1974, and also President of Burma ...

, stepped down. Mass demonstrations for democracy followed that event on 8 August 1988 (8–8–88, a day seen as auspicious), which were violently suppressed in what came to be known as the 8888 Uprising

The 8888 Uprising ( my, ၈၈၈၈ အရေးအခင်း), also known as the People Power UprisingYawnghwe (1995), pp. 170 and the 1988 Uprising, was a series of nationwide protests, marches, and riots in Burma (present-day Myanmar) th ...

. On 26 August 1988, she addressed half a million people at a mass rally in front of the Shwedagon Pagoda

The Shwedagon Pagoda (, ); mnw, ကျာ်ဒဂုၚ်; officially named ''Shwedagon Zedi Daw'' ( my, ရွှေတိဂုံစေတီတော်, , ) and also known as the Great Dagon Pagoda and the Golden Pagoda is a gilded stupa ...

in the capital, calling for a democratic government. However, in September 1988, a new military junta took power.

Influenced by both Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure ...

's philosophy of non-violence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

and also by the Buddhist concepts, Aung San Suu Kyi entered politics to work for democratization, helped found the National League for Democracy

The National League for Democracy ( my, အမျိုးသား ဒီမိုကရေစီ အဖွဲ့ချုပ်, ; abbr. NLD; Burmese abbr. ဒီချုပ်) is a liberal democratic political party in Myanmar (Burma). It ...

on 27 September 1988, but was put under house arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if ...

on 20 July 1989. She was offered freedom if she left the country, but she refused. Despite her philosophy of non-violence, a group of ex-military commanders and senior politicians who joined NLD during the crisis believed that she was too confrontational and left NLD. However, she retained enormous popularity and support among NLD youths with whom she spent most of her time.

During the crisis, the previous democratically elected Prime Minister of Burma, U Nu

Nu ( my, ဦးနု; ; 25 May 1907 – 14 February 1995), commonly known as U Nu also known by the honorific name Thakin Nu, was a leading Burmese statesman and nationalist politician. He was the first Prime Minister of Burma under the pro ...

, initiated to form an interim government and invited opposition leaders to join him. Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi

Rajiv Gandhi (; 20 August 1944 – 21 May 1991) was an Indian politician who served as the sixth prime minister of India from 1984 to 1989. He took office after the 1984 assassination of his mother, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, to bec ...

had signaled his readiness to recognize the interim government. However, Aung San Suu Kyi categorically rejected U Nu's plan by saying "the future of the opposition would be decided by masses of the people". Ex-Brigadier General Aung Gyi

Brigadier General Aung Gyi ( my, အောင်ကြီး ; 16 February 1919 – 25 October 2012) was a Burmese military officer and politician. He was a cofounder of the National League for Democracy and served as president of the party.

...

, another influential politician at the time of the 8888 crisis and the first chairman in the history of the NLD, followed the suit and rejected the plan after Aung San Suu Kyi's refusal. Aung Gyi later accused several NLD members of being communists and resigned from the party.

1990 general election and Nobel Peace Prize

In 1990, the military junta called ageneral election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

, in which the National League for Democracy (NLD) received 59% of the votes, guaranteeing NLD 80% of the parliament seats. Some claim that Aung San Suu Kyi would have assumed the office of Prime Minister. Instead, the results were nullified and the military refused to hand over power, resulting in an international outcry. Aung San Suu Kyi was placed under house arrest at her home on University Avenue () in Rangoon, during which time she was awarded the Sakharov Prize

The Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, commonly known as the Sakharov Prize, is an honorary award for individuals or groups who have dedicated their lives to the defence of human rights and freedom of thought. Named after Russian scientis ...

for Freedom of Thought in 1990, and the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

one year later. Her sons Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

and Kim accepted the Nobel Peace Prize on her behalf. Aung San Suu Kyi used the Nobel Peace Prize's US$1.3 million prize money to establish a health and education trust for the Burmese people. Around this time, Aung San Suu Kyi chose non-violence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

as an expedient political tactic, stating in 2007, "I do not hold to non-violence for moral reasons, but for political and practical reasons."

The decision of the Nobel Committee mentions:Nobel Committee press release. In 1995 Aung San Suu Kyi delivered the keynote address at the Fourth World Conference on Women in

Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

.

1996 attack

On 9 November 1996, themotorcade

A motorcade, or autocade, is a procession of vehicles.

Etymology

The term ''motorcade'' was coined by Lyle Abbot (in 1912 or 1913 when he was automobile editor of the ''Arizona Republican''), and is formed after ''cavalcade'', playing off of ...

that Aung San Suu Kyi was traveling in with other National League for Democracy leaders Tin Oo and Kyi Maung

Colonel Kyi Maung ( my, ကြည်မောင်, ; 20 December 192019 August 2004) was a Burmese Army officer and politician. Originally a member of the military-backed Union Revolutionary Council that seized power in 1962, Kyi Maung resigne ...

, was attacked in Yangon. About 200 men swooped down on the motorcade, wielding metal chains, metal batons, stones and other weapons. The car that Aung San Suu Kyi was in had its rear window smashed, and the car with Tin Oo and Kyi Maung had its rear window and two backdoor windows shattered. It is believed the offenders were members of the Union Solidarity and Development Association

The Union Solidarity and Development Association ( ; abbreviated USDA) was a Burmese political party founded with the active aid of Myanmar's ruling military junta, the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), on 15 September 1993.

H ...

(USDA) who were allegedly paid Ks.500/- (@ USD $0.50) each to participate. The NLD lodged an official complaint with the police, and according to reports the government launched an investigation, but no action was taken. ( Amnesty International 120297)

House arrest

Aung San Suu Kyi was placed underhouse arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if ...

for a total of 15 years over a 21-year period, on numerous occasions, since she began her political career,Moe, Wait (3 August 2009)Suu Kyi Questions Burma's Judiciary, Constitution

. ''

The Irrawaddy

''The Irrawaddy'' () is a news website by the Irrawaddy Publishing Group (IPG), founded in 1990 by Burmese exiles living in Thailand. From its inception, ''The Irrawaddy'' has taken an independent stance on Burmese politics. As a publication p ...

''. during which time she was prevented from meeting her party supporters and international visitors. In an interview, she said that while under house arrest she spent her time reading philosophy, politics and biographies that her husband had sent her. She also passed the time playing the piano and was occasionally allowed visits from foreign diplomats as well as from her personal physician.

Although under house arrest, Aung San Suu Kyi was granted permission to leave Burma under the condition that she never return, which she refused: "As a mother, the greater sacrifice was giving up my sons, but I was always aware of the fact that others had given up more than me. I never forget that my colleagues who are in prison suffer not only physically, but mentally for their families who have no security outside- in the larger prison of Burma under authoritarian rule."

The media were also prevented from visiting Aung San Suu Kyi, as occurred in 1998 when journalist Maurizio Giuliano

Maurizio Giuliano (born 1975) is an Italian United Nations official, traveller, author and journalist. As of 2004 he was, according to the ''Guinness Book of World Records'', the youngest person to have visited all sovereign nations of the world ...

, after photographing her, was stopped by customs officials who then confiscated all his films, tapes and some notes. In contrast, Aung San Suu Kyi did have visits from government representatives, such as during her autumn 1994 house arrest when she met the leader of Burma, General Than Shwe

Than Shwe ( my, သန်းရွှေ, ; born 2 February 1933 or 3 May 1935) is a Burmese strongman politician who was the head of state of Myanmar from 1992 to 2011 as Chairman of the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC).

During thi ...

and General Khin Nyunt

General Khin Nyunt (; ; born 23 October 1939) is a Burmese military officer and politician. He held the office of Chief of Intelligence and was Prime Minister of Myanmar from 25 August 2003 until 18 October 2004.

Early life and education

Kh ...

on 20 September in the first meeting since she had been placed in detention. On several occasions during her house arrest, she had periods of poor health and as a result was hospitalized.

The Burmese government detained and kept Aung San Suu Kyi imprisoned because it viewed her as someone "likely to undermine the community peace and stability" of the country, and used both Article 10(a) and 10(b) of the 1975 State Protection Act (granting the government the power to imprison people for up to five years without a trial), and Section 22 of the "Law to Safeguard the State Against the Dangers of Those Desiring to Cause Subversive Acts" as legal tools against her. She continuously appealed her detention, and many nations and figures continued to call for her release and that of 2,100 other political prisoners in the country. On 12 November 2010, days after the junta-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) won elections conducted after a gap of 20 years, the junta finally agreed to sign orders allowing Aung San Suu Kyi's release, and her house arrest term came to an end on 13 November 2010.

United Nations involvement

The United Nations (UN) has attempted to facilitate dialogue between thejunta

Junta may refer to:

Government and military

* Junta (governing body) (from Spanish), the name of various historical and current governments and governing institutions, including civil ones

** Military junta, one form of junta, government led by ...

and Aung San Suu Kyi. On 6 May 2002, following secret confidence-building negotiations led by the UN, the government released her; a government spokesman said that she was free to move "because we are confident that we can trust each other". Aung San Suu Kyi proclaimed "a new dawn for the country". However, on 30 May 2003 in an incident similar to the 1996 attack on her, a government-sponsored mob attacked her caravan in the northern village of Depayin, murdering and wounding many of her supporters. Aung San Suu Kyi fled the scene with the help of her driver, Kyaw Soe Lin, but was arrested upon reaching Ye-U. The government imprisoned her at Insein Prison

Insein Prison ( my, အင်းစိန်ထောင်) is located in Yangon Division, near Yangon (Rangoon), the old capital of Myanmar (formerly Burma). From 1988 to 2011 it was run by the military junta of Myanmar, named the State Law an ...

in Rangoon. After she underwent a hysterectomy

Hysterectomy is the surgical removal of the uterus. It may also involve removal of the cervix, ovaries ( oophorectomy), Fallopian tubes ( salpingectomy), and other surrounding structures.

Usually performed by a gynecologist, a hysterectomy may ...

in September 2003, the government again placed her under house arrest in Rangoon.

The results from the UN facilitation have been mixed; Razali Ismail

Razali bin Ismail (born 14 April 1939) is a Malaysian diplomat. He is formerly the Chairman of the Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (SUHAKAM) from 2016 to 2019. He was also the 51st President of the United Nations General Assembly from 1996 un ...

, UN special envoy to Burma, met with Aung San Suu Kyi. Ismail resigned from his post the following year, partly because he was denied re-entry to Burma on several occasions. Several years later in 2006, Ibrahim Gambari

Ibrahim Agboola Gambari, (born 24 November 1944), is a Nigerian academic and diplomat who is currently serving as Chief of Staff to the President of Nigeria.

Early life and education

Ibrahim Agboola Gambari was born on 24 November 1944 in Ilor ...

, UN Undersecretary-General (USG) of Department of Political Affairs, met with Aung San Suu Kyi, the first visit by a foreign official since 2004. He also met with her later the same year. On 2 October 2007 Gambari returned to talk to her again after seeing Than Shwe

Than Shwe ( my, သန်းရွှေ, ; born 2 February 1933 or 3 May 1935) is a Burmese strongman politician who was the head of state of Myanmar from 1992 to 2011 as Chairman of the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC).

During thi ...

and other members of the senior leadership in Naypyidaw

Naypyidaw, officially spelled Nay Pyi Taw (; ), is the capital and third-largest city of Myanmar. The city is located at the centre of the Naypyidaw Union Territory. It is unusual among Myanmar's cities, as it is an entirely planned city ou ...

. State television broadcast Aung San Suu Kyi with Gambari, stating that they had met twice. This was Aung San Suu Kyi's first appearance in state media in the four years since her current detention began.

The United Nations Working Group for Arbitrary Detention published an Opinion that Aung San Suu Kyi's deprivation of liberty was arbitrary and in contravention of Article 9 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN committee chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt, ...

1948, and requested that the authorities in Burma set her free, but the authorities ignored the request at that time.Daw Aung San Suu Kyi v. Myanmar, U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, U.N. Doc. E/CN.4/2005/6/Add.1 at 47 (2004). The U.N. report said that according to the Burmese Government's reply, "Daw Aung San Suu Kyi has not been arrested, but has only been taken into protective custody, for her own safety", and while "it could have instituted legal action against her under the country's domestic legislation ... it has preferred to adopt a magnanimous attitude, and is providing her with protection in her own interests". Such claims were rejected by Brig-General Khin Yi, Chief of

Myanmar Police Force

The Myanmar Police Force ( my, မြန်မာနိုင်ငံ ရဲတပ်ဖွဲ့), formerly the People's Police Force (), is the law enforcement agency of Myanmar. It was established in 1964 as an independent department under ...

(MPF). On 18 January 2007, the state-run paper ''New Light of Myanmar

''The New Light of Myanmar'' (, ; formerly ''The New Light of Burma'') is a government-owned newspaper published by the Ministry of Information and based in Yangon, Myanmar.

''The New Light of Myanmar'' is often viewed as propaganda

Propaga ...

'' accused Aung San Suu Kyi of tax evasion

Tax evasion is an illegal attempt to defeat the imposition of taxes by individuals, corporations, trusts, and others. Tax evasion often entails the deliberate misrepresentation of the taxpayer's affairs to the tax authorities to reduce the tax ...

for spending her Nobel Prize money outside the country. The accusation followed the defeat of a US-sponsored United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the Organs of the United Nations, six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international security, international peace and security, recommending the admi ...

resolution condemning Burma as a threat to international security; the resolution was defeated because of strong opposition from China, which has strong ties with the military junta (China later voted against the resolution, along with Russia and South Africa).

In November 2007, it was reported that Aung San Suu Kyi would meet her political allies National League for Democracy along with a government minister. The ruling junta made the official announcement on state TV and radio just hours after UN special envoy Ibrahim Gambari

Ibrahim Agboola Gambari, (born 24 November 1944), is a Nigerian academic and diplomat who is currently serving as Chief of Staff to the President of Nigeria.

Early life and education

Ibrahim Agboola Gambari was born on 24 November 1944 in Ilor ...

ended his second visit to Burma. The NLD confirmed that it had received the invitation to hold talks with Aung San Suu Kyi. However, the process delivered few concrete results.

On 3 July 2009, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon

Ban Ki-moon (; ; born 13 June 1944) is a South Korean politician and diplomat who served as the eighth secretary-general of the United Nations between 2007 and 2016. Prior to his appointment as secretary-general, Ban was his country's Minister ...

went to Burma to pressure the junta into releasing Aung San Suu Kyi and to institute democratic reform. However, on departing from Burma, Ban Ki-moon said he was "disappointed" with the visit after junta leader Than Shwe

Than Shwe ( my, သန်းရွှေ, ; born 2 February 1933 or 3 May 1935) is a Burmese strongman politician who was the head of state of Myanmar from 1992 to 2011 as Chairman of the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC).

During thi ...

refused permission for him to visit Aung San Suu Kyi, citing her ongoing trial. Ban said he was "deeply disappointed that they have missed a very important opportunity".

Periods under detention

* 20 July 1989: Placed under house arrest in Rangoon undermartial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

that allows for detention without charge or trial for three years.

* 10 July 1995: Released from house arrest.

* 23 September 2000: Placed under house arrest.

* 6 May 2002: Released after 19 months.

* 30 May 2003: Arrested following the Depayin massacre, she was held in secret detention for more than three months before being returned to house arrest.

* 25 May 2007: House arrest extended by one year despite a direct appeal from U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan

Kofi Atta Annan (; 8 April 193818 August 2018) was a Ghanaian diplomat who served as the seventh secretary-general of the United Nations from 1997 to 2006. Annan and the UN were the co-recipients of the 2001 Nobel Peace Prize. He was the found ...

to General Than Shwe

Than Shwe ( my, သန်းရွှေ, ; born 2 February 1933 or 3 May 1935) is a Burmese strongman politician who was the head of state of Myanmar from 1992 to 2011 as Chairman of the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC).

During thi ...

.

* 24 October 2007: Reached 12 years under house arrest, solidarity

''Solidarity'' is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration.''Merriam Webster'', http://www.merriam-webster.com/dicti ...

protests held at 12 cities around the world.

* 27 May 2008: House arrest extended for another year, which is illegal under both international law

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for ...

and Burma's own law.

* 11 August 2009: House arrest extended for 18 more months because of "violation" arising from the May 2009 trespass incident.

* 13 November 2010: Released from house arrest.

2007 anti-government protests

Protests led by Buddhist monks began on 19 August 2007 following steep fuel price increases, and continued each day, despite the threat of a crackdown by the military. On 22 September 2007, although still underhouse arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if ...

, Aung San Suu Kyi made a brief public appearance at the gate of her residence in Yangon to accept the blessings of Buddhist monks who were marching in support of human rights. It was reported that she had been moved the following day to Insein Prison

Insein Prison ( my, အင်းစိန်ထောင်) is located in Yangon Division, near Yangon (Rangoon), the old capital of Myanmar (formerly Burma). From 1988 to 2011 it was run by the military junta of Myanmar, named the State Law an ...

(where she had been detained in 2003),Suu Kyi moved to Insein prisonReuters. 25 September 2007Inside Burma's Insein jail

. BBC News. 14 May 2009Security tight amid speculation Suu Kyi jailed

. ''

The Australian

''The Australian'', with its Saturday edition, ''The Weekend Australian'', is a broadsheet newspaper published by News Corp Australia since 14 July 1964.Bruns, Axel. "3.1. The active audience: Transforming journalism from gatekeeping to gatewat ...

''. 28 September 2007Burmese Junta silences the monks. ''Time''. 28 September 2007 but meetings with UN envoy

Ibrahim Gambari

Ibrahim Agboola Gambari, (born 24 November 1944), is a Nigerian academic and diplomat who is currently serving as Chief of Staff to the President of Nigeria.

Early life and education

Ibrahim Agboola Gambari was born on 24 November 1944 in Ilor ...

near her Rangoon home on 30 September and 2 October established that she remained under house arrest.

2009 trespass incident

On 3 May 2009, an American man, identified as John Yettaw, swam across

On 3 May 2009, an American man, identified as John Yettaw, swam across Inya Lake

Inya Lake ( my, အင်းလျားကန်, ''ʔīnyā kǎn'' ; formerly, Lake Victoria) is the largest lake in Yangon, Burma (Myanmar), a popular recreational area for Yangonites, and a famous location for romance in popular culture. Loc ...

to her house uninvited and was arrested when he made his return trip three days later. He had attempted to make a similar trip two years earlier, but for unknown reasons was turned away.James, Randy (20 May 2009)John Yettaw: Suu Kyi's Unwelcome Visitor

. ''Time''. He later claimed at trial that he was motivated by a divine vision requiring him to notify her of an impending terrorist assassination attempt. On 13 May, Aung San Suu Kyi was arrested for violating the terms of her house arrest because the swimmer, who pleaded exhaustion, was allowed to stay in her house for two days before he attempted the swim back. Aung San Suu Kyi was later taken to

Insein Prison

Insein Prison ( my, အင်းစိန်ထောင်) is located in Yangon Division, near Yangon (Rangoon), the old capital of Myanmar (formerly Burma). From 1988 to 2011 it was run by the military junta of Myanmar, named the State Law an ...

, where she could have faced up to five years' confinement for the intrusion. The trial of Aung San Suu Kyi and her two maids began on 18 May and a small number of protesters gathered outside. Diplomats and journalists were barred from attending the trial; however, on one occasion, several diplomats from Russia, Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

and Singapore and journalists were allowed to meet Aung San Suu Kyi. The prosecution had originally planned to call 22 witnesses. It also accused John Yettaw of embarrassing the country.Myanmar Court Charges Suu Kyi, ''The Wall Street Journal'', 22 May 2009 During the ongoing defence case, Aung San Suu Kyi said she was innocent. The defence was allowed to call only one witness (out of four), while the prosecution was permitted to call 14 witnesses. The court rejected two character witnesses, NLD members Tin Oo and Win Tin, and permitted the defence to call only a legal expert. According to one unconfirmed report, the junta was planning to, once again, place her in detention, this time in a military base outside the city. In a separate trial, Yettaw said he swam to Aung San Suu Kyi's house to warn her that her life was "in danger". The national police chief later confirmed that Yettaw was the "main culprit" in the case filed against Aung San Suu Kyi. According to aides, Aung San Suu Kyi spent her 64th birthday in jail sharing

biryani

Biryani () is a mixed rice dish originating among the Muslims of the Indian subcontinent. It is made with Indian spices, rice, and usually some type of meat (chicken, beef, goat, lamb, prawn, fish) or in some cases without any meat, and ...

rice and chocolate cake with her guards.

Her arrest and subsequent trial received worldwide condemnation by the UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon

Ban Ki-moon (; ; born 13 June 1944) is a South Korean politician and diplomat who served as the eighth secretary-general of the United Nations between 2007 and 2016. Prior to his appointment as secretary-general, Ban was his country's Minister ...

, the United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the Organs of the United Nations, six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international security, international peace and security, recommending the admi ...

, Western governments, South Africa, Japan and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations

ASEAN ( , ), officially the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, is a political and economic union of 10 member states in Southeast Asia, which promotes intergovernmental cooperation and facilitates economic, political, security, mi ...

, of which Burma is a member. The Burmese government strongly condemned the statement, as it created an "unsound tradition" and criticised Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

for meddling in its internal affairs. The Burmese Foreign Minister Nyan Win

Nyan Win ( my, ဉာဏ်ဝင်း, ; born 22 January 1953) is the Chief Minister of Bago Region from 2011 to 2016. He won a Regional Hluttaw seat in an uncontested election in 2010, representing Zigon Township, and was appointed Chief Mi ...

was quoted in the state-run newspaper ''New Light of Myanmar'' as saying that the incident "was trumped up to intensify international pressure on Burma by internal and external anti-government elements who do not wish to see the positive changes in those countries' policies toward Burma". Ban responded to an international campaign by flying to Burma to negotiate, but Than Shwe rejected all of his requests.

On 11 August 2009, the trial concluded with Aung San Suu Kyi being sentenced to imprisonment for three years with hard labour. This sentence was commuted by the military rulers to further house arrest of 18 months. On 14 August, US Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

Jim Webb

James Henry Webb Jr. (born February 9, 1946) is an American politician and author. He has served as a United States senator from Virginia, Secretary of the Navy, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Reserve Affairs, Counsel for the United Stat ...

visited Burma, visiting with junta leader Gen. Than Shwe

Than Shwe ( my, သန်းရွှေ, ; born 2 February 1933 or 3 May 1935) is a Burmese strongman politician who was the head of state of Myanmar from 1992 to 2011 as Chairman of the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC).

During thi ...

and later with Aung San Suu Kyi. During the visit, Webb negotiated Yettaw's release and deportation from Burma. Following the verdict of the trial, lawyers of Aung San Suu Kyi said they would appeal against the 18-month sentence. On 18 August, United States President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

asked the country's military leadership to set free all political prisoners, including Aung San Suu Kyi. In her appeal, Aung San Suu Kyi had argued that the conviction was unwarranted. However, her appeal against the August sentence was rejected by a Burmese court on 2 October 2009. Although the court accepted the argument that the 1974 constitution, under which she had been charged, was null and void, it also said the provisions of the 1975 security law, under which she has been kept under house arrest, remained in force. The verdict effectively meant that she would be unable to participate in the elections scheduled to take place in 2010—the first in Burma in two decades. Her lawyer stated that her legal team would pursue a new appeal within 60 days.

Late 2000s: International support for release

IOL. 7 October 2007 Australia and NorthUS House honours Burma's Suu Kyi

BBC News, 18 December 2007. and South America, as well as India, Israel, Japan the Philippines and South Korea. In December 2007, the US House of Representatives voted unanimously 400–0 to award Aung San Suu Kyi the

Congressional Gold Medal

The Congressional Gold Medal is an award bestowed by the United States Congress. It is Congress's highest expression of national appreciation for distinguished achievements and contributions by individuals or institutions. The congressional pract ...

; the Senate concurred on 25 April 2008. On 6 May 2008, President George W. Bush signed legislation awarding Aung San Suu Kyi the Congressional Gold Medal. She is the first recipient in American history to receive the prize while imprisoned. More recently, there has been growing criticism of her detention by Burma's neighbours in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, particularly from Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines and Singapore. At one point Malaysia warned Burma that it faced expulsion from ASEAN as a result of the detention of Aung San Suu Kyi. Other nations including South Africa, Bangladesh and the Maldives also called for her release. The United Nations has urged the country to move towards inclusive national reconciliation, the restoration of democracy, and full respect for human rights. In December 2008, the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Cur ...

passed a resolution condemning the human rights situation in Burma and calling for Aung San Suu Kyi's release—80 countries voting for the resolution, 25 against and 45 abstentions. Other nations, such as China and Russia, are less critical of the regime and prefer to cooperate only on economic matters. Indonesia has urged China to push Burma for reforms. However, Samak Sundaravej

Samak Sundaravej ( th, สมัคร สุนทรเวช, , ; 13 June 1935 – 24 November 2009) was a Thai politician who briefly served as the Prime Minister of Thailand and Minister of Defense in 2008, as well as the leader of the Pe ...

, former Prime Minister of Thailand

The prime minister of Thailand ( th, นายกรัฐมนตรี, , ; literally 'chief minister of state') is the head of government of Thailand. The prime minister is also the chair of the Cabinet of Thailand. The post has existed s ...

, criticised the amount of support for Aung San Suu Kyi, saying that "Europe uses Aung San Suu Kyi as a tool. If it's not related to Aung San Suu Kyi, you can have deeper discussions with Myanmar."

Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making it ...

, however, did not support calls by other ASEAN member states for Myanmar to free Aung San Suu Kyi, state media reported Friday, 14 August 2009. The state-run Việt Nam News

''Việt Nam News'' is an English-language daily print newspaper with offices in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh, published by the Vietnam News Agency, the news service of the government of Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), offici ...

said Vietnam had no criticism of Myanmar's decision 11 August 2009 to place Aung San Suu Kyi under house arrest for the next 18 months, effectively barring her from elections scheduled for 2010. "It is our view that the Aung San Suu Kyi trial is an internal affair of Myanmar", Vietnamese government spokesman Le Dung stated on the website of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The enti ...

. In contrast with other ASEAN member states, Dung said Vietnam has always supported Myanmar and hopes it will continue to implement the "roadmap to democracy

Myanmar's roadmap to democracy ( my, ဒီမိုကရေစီလမ်းပြမြေပုံ ၇ ချက်; officially the Roadmap to Discipline-flourishing Democracy), announced by General Khin Nyunt on 30 August 2003 in state ...

" outlined by its government.

Nobel Peace Prize winners (Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Desmond Mpilo Tutu (7 October 193126 December 2021) was a South African Anglican bishop and theologian, known for his work as an anti-apartheid and human rights activist. He was Bishop of Johannesburg from 1985 to 1986 and then Archbish ...

, the Dalai Lama, Shirin Ebadi

Shirin Ebadi ( fa, شيرين عبادى, Širin Ebādi; born 21 June 1947) is an Iranian political activist, lawyer, a former judge and human rights activist and founder of Defenders of Human Rights Center in Iran. On 10 October 2003, Ebadi wa ...

, Adolfo Pérez Esquivel

Adolfo Pérez Esquivel (born 26 November 1931) is an Argentine activist, community organizer, painter, writer and sculptor. He was the recipient of the 1980 Nobel Peace Prize for his opposition to Argentina's last civil-military dictatorship (1 ...

, Mairead Corrigan

Mairead MaguireFairmichael, p. 28: "Mairead Corrigan, now Mairead Maguire, married her former brother-in-law, Jackie Maguire, and they have two children of their own as well as three by Jackie's previous marriage to Ann Maguire." (born 27 Januar ...

, Rigoberta Menchú

Rigoberta Menchú Tum (; born 9 January 1959) is a K'iche' Guatemalan human rights activist, feminist, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Menchú has dedicated her life to publicizing the rights of Guatemala's Indigenous peoples during and after t ...

, Prof. Elie Wiesel

Elie Wiesel (, born Eliezer Wiesel ''Eliezer Vizel''; September 30, 1928 – July 2, 2016) was a Romanian-born American writer, professor, political activist, Nobel laureate, and Holocaust survivor. He authored 57 books, written mostly in Fr ...

, US President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

, Betty Williams

Elizabeth Williams ( Smyth; 22 May 1943 – 17 March 2020) was a peace activist from Northern Ireland. She was a co-recipient with Mairead Corrigan of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1976 for her work as a cofounder of Community of Peace People, ...

, Jody Williams

Jody Williams (born October 9, 1950) is an American political activist known for her work in banning anti-personnel landmines, her defense of human rights (especially those of women), and her efforts to promote new understandings of securit ...

and former US President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 19 ...

) called for the rulers of Burma to release Aung San Suu Kyi to "create the necessary conditions for a genuine dialogue with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and all concerned parties and ethnic groups to achieve an inclusive national reconciliation with the direct support of the United Nations". Some of the money she received as part of the award helped fund higher education grants to Burmese students through the London-based charity Prospect Burma.

It was announced prior to the 2010 Burmese general election

General elections were held in Myanmar on 2010, in accordance with the new constitution, which was approved in a referendum held in . The election date was announced by the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) on .

The elections were the ...

that Aung San Suu Kyi may be released "so she can organize her party", However, Aung San Suu Kyi was not allowed to run. On 1 October 2010 the government announced that she would be released on 13 November 2010.

US President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

personally advocated the release of all political prisoners, especially Aung San Suu Kyi, during the US-ASEAN

ASEAN ( , ), officially the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, is a Political union, political and economic union of 10 member Sovereign state, states in Southeast Asia, which promotes intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental coo ...

Summit of 2009.

The US Government hoped that successful general elections would be an optimistic indicator of the Burmese government's sincerity towards eventual democracy. The Hatoyama government which spent 2.82 billion yen in 2008, has promised more Japanese foreign aid to encourage Burma to release Aung San Suu Kyi in time for the elections; and to continue moving towards democracy and the rule of law.

In a personal letter to Aung San Suu Kyi, UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown

James Gordon Brown (born 20 February 1951) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 2007 to 2010. He previously served as Chance ...

cautioned the Burmese government of the potential consequences of rigging elections as "condemning Burma to more years of diplomatic isolation and economic stagnation".

Aung San Suu Kyi met with many heads of state and opened a dialog with the Minister of Labor Aung Kyi (not to be confused with Aung San Suu Kyi). She was allowed to meet with senior members of her NLD party at the State House, however these meetings took place under close supervision.

2010 release

On the evening of 13 November 2010, Aung San Suu Kyi was released from house arrest. This was the date her detention had been set to expire according to a court ruling in August 2009 and came six days after a widely criticised

On the evening of 13 November 2010, Aung San Suu Kyi was released from house arrest. This was the date her detention had been set to expire according to a court ruling in August 2009 and came six days after a widely criticised general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

. She appeared in front of a crowd of her supporters, who rushed to her house in Rangoon when nearby barricades were removed by the security forces. Aung San Suu Kyi had been detained for 15 of the past 21 years. The government newspaper ''New Light of Myanmar'' reported the release positively, saying she had been granted a pardon after serving her sentence "in good conduct". ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' suggested that the military government may have released Aung San Suu Kyi because it felt it was in a confident position to control her supporters after the election.

Her son Kim Aris was granted a visa in November 2010 to see his mother shortly after her release, for the first time in 10 years. He visited again on 5 July 2011, to accompany her on a trip to Bagan

Bagan (, ; formerly Pagan) is an ancient city and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in the Mandalay Region of Myanmar. From the 9th to 13th centuries, the city was the capital of the Bagan Kingdom, the first kingdom that unified the regions that wo ...

, her first trip outside Yangon

Yangon ( my, ရန်ကုန်; ; ), formerly spelled as Rangoon, is the capital of the Yangon Region and the largest city of Myanmar (also known as Burma). Yangon served as the capital of Myanmar until 2006, when the military government ...

since 2003. Her son visited again on 8 August 2011, to accompany her on a trip to Pegu

Bago (formerly spelt Pegu; , ), formerly known as Hanthawaddy, is a city and the capital of the Bago Region in Myanmar. It is located north-east of Yangon.

Etymology

The Burmese name Bago (ပဲခူး) is likely derived from the Mon langu ...

, her second trip.

Discussions were held between Aung San Suu Kyi and the Burmese government during 2011, which led to a number of official gestures to meet her demands. In October, around a tenth of Burma's political prisoners were freed in an amnesty and trade unions were legalised.

In November 2011, following a meeting of its leaders, the NLD announced its intention to re-register as a political party to contend 48 by-elections necessitated by the promotion of parliamentarians to ministerial rank. Following the decision, Aung San Suu Kyi held a telephone conference with US President Barack Obama, in which it was agreed that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, diplomat, and former lawyer who served as the 67th United States Secretary of State for President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, as a United States senat ...

would make a visit to Burma, a move received with caution by Burma's ally China. On 1 December 2011, Aung San Suu Kyi met with Hillary Clinton at the residence of the top-ranking US diplomat in Yangon.

On 21 December 2011, Thai Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra

Yingluck Shinawatra ( th, ยิ่งลักษณ์ ชินวัตร, , ; ; born 21 June 1967), nicknamed Pou ( th, ปู, , , meaning "crab"), is a Thai businesswoman, politician and a member of the Pheu Thai Party who became the Pr ...

met Aung San Suu Kyi in Yangoon, marking Aung San Suu Kyi's "first-ever meeting with the leader of a foreign country".

On 5 January 2012, British Foreign Minister William Hague met Aung San Suu Kyi and his Burmese counterpart. This represented a significant visit for Aung San Suu Kyi and Burma. Aung San Suu Kyi studied in the UK and maintains many ties there, whilst Britain is Burma's largest bilateral donor.

During Aung San Suu Kyi's visit to Europe, she visited the Swiss parliament, collected her 1991 Nobel Prize in Oslo and her honorary degree from the University of Oxford.twist in Aung San Suu Kyi's fateArticle: How a Missouri Mormon may have thwarted democracy in Myanmar. By Patrick Winn — GlobalPost Quote: "Suu Kyi has mostly lived under house arrest since 1990 when the country's military junta refused her election to the prime minister's seat. The Nobel Peace Laureate remains backed by a pro-democracy movement-in-exile, many of them also voted into a Myanmar parliament that never was." Published: 21 May 2009 00:48 ETBANGKOK, Thailand

2012 by-elections

In December 2011, there was speculation that Aung San Suu Kyi would run in the 2012 national by-elections to fill vacant seats. On 18 January 2012, Aung San Suu Kyi formally registered to contest aPyithu Hluttaw

The Pyithu Hluttaw ( my, ပြည်သူ့ လွှတ်တော်, ; House of Representatives) is the ''de jure'' lower house of the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, the bicameral legislature of Myanmar (Burma). It consists of 440 members, of wh ...

(lower house) seat in the Kawhmu Township

Kawmhu Township ( my, ကော့မှူး မြို့နယ် ) is a township of Yangon Region, Myanmar. It is located in the southwestern section of the Region. Kawhmu was one of the townships in Yangon Region most affected by Cycl ...

constituency in special parliamentary elections to be held on 1 April 2012. The seat was previously held by Soe Tint, who vacated it after being appointed Construction Deputy Minister, in the 2010 election. She ran against Union Solidarity and Development Party

The Union Solidarity and Development Party ( my, ပြည်ထောင်စုကြံ့ခိုင်ရေးနှင့် ဖွံ့ဖြိုးရေးပါတီ; abbr. USDP) is a political party in Myanmar, registered on ...

candidate Soe Min, a retired army physician and native of Twante Township

Twante Township also Twantay Township ( my, တွံတေး မြို့နယ်, ) is a township in the Yangon Region of Burma (Myanmar). It is located west across the Hlaing River from the city of Yangon. The principal town and administr ...

.

On 3 March 2012, at a large campaign rally in

On 3 March 2012, at a large campaign rally in Mandalay

Mandalay ( or ; ) is the second-largest city in Myanmar, after Yangon. Located on the east bank of the Irrawaddy River, 631km (392 miles) (Road Distance) north of Yangon, the city has a population of 1,225,553 (2014 census).

Mandalay was fo ...

, Aung San Suu Kyi unexpectedly left after 15 minutes, because of exhaustion and airsickness.

In an official campaign speech broadcast on Burmese state television's MRTV on 14 March 2012, Aung San Suu Kyi publicly campaigned for reform of the 2008 Constitution, removal of restrictive laws, more adequate protections for people's democratic rights, and establishment of an independent judiciary. The speech was leaked online a day before it was broadcast. A paragraph in the speech, focusing on the Tatmadaw

Tatmadaw (, , ) is the official name of the armed forces of Myanmar (formerly Burma). It is administered by the Ministry of Defence and composed of the Myanmar Army, the Myanmar Navy and the Myanmar Air Force. Auxiliary services include t ...

's repression by means of law, was censored by authorities.