Augustus Earle on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Augustus Earle (1793–1838) was a British painter. Unlike earlier artists who worked outside

Augustus Earle (1793–1838) was a British painter. Unlike earlier artists who worked outside

A number of the works produced dealt with the subject of

A number of the works produced dealt with the subject of

''Punishing negroes at Cathabouco (Calobouco), Rio de Janeiro''''Negro fandango scene, Campo St. Anna nr. Rio''

an

''Games at Rio de Janeiro, during the Carnival''

Other works included landscapes and a series of portraits.

''Government House, Tristan D'Acunha (i.e. da Cunha)''

which was reproduced in his Narrativ

an

''Flinching a young sea elephant''

''June Park, Van Dieman's (sic) Land, perfect park scenery''

an

''Cape Barathas, (i.e. Barathus) Adventure Bay, Van Dieman's (i.e. Diemen's) Land''

Earle left Hobart for

Augustus Earle, ''A narrative of a nine months' residence in New Zealand in 1827: together with a journal of a residence in Tristan D'Acunha, an island situated between South America and the Cape of Good Hope'' (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman, 1832).Full text

''The Wandering Artist: Augustus Earle's Travels Around The World 1820-29''

a

Augustus Earle at Australian Art

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Earle, Augustus 19th-century English painters English male painters English watercolourists Landscape artists 1790s births 1838 deaths 19th-century Australian painters 19th-century English male artists Australian landscape painters

Augustus Earle (1793–1838) was a British painter. Unlike earlier artists who worked outside

Augustus Earle (1793–1838) was a British painter. Unlike earlier artists who worked outside Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

and were employed on voyages of exploration or worked abroad for wealthy, often aristocratic patrons, Earle was able to operate quite independently - able to combine his lust for travel with an ability to earn a living through art. The body of work he produced during his travels comprises a significant documentary record of the effects of European contact and colonisation during the early nineteenth century.

Life

Early life

Augustus Earle was born inLondon

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

on 1 June 1793. He was the youngest child of an American-born father, James Earle (1761–1796), an artist, and Georgiana Caroline Smyth, daughter of John Carteret Pilkington and former partner (with two children) of Joseph Brewer Palmer Smyth, an American loyalist who spent some years in England. Earle's father James was a member of the prominent American Earle family. The elder of his two sisters was Phoebe Earle (1790–1863), also a professional painter and wife of the artist Denis Dighton, while his older half-sister was Elizabeth Anne Smyth (1787–1838) and his older half-brother was the scientist Admiral William Henry Smyth

Admiral William Henry Smyth (21 January 1788 – 8 September 1865) was a Royal Navy officer, hydrographer, astronomer and numismatist. He is noted for his involvement in the early history of a number of learned societies, for his hydrographic ...

(1788–1865). There is no record of him marrying or having children.

Earle received his artistic training in the Royal Academy and was already exhibiting there at the age of 13. Earle exhibited classical, genre and historical paintings in six Royal Academy exhibitions between 1806 and 1814.

Mediterranean tour

In 1815, at the age of twenty-two, Earle's half-brother, William Henry Smyth had sought and was given permission byLord Exmouth

Viscount Exmouth, of Canonteign in the County of Devon, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom.

History

The title was created in 1816 for the prominent naval officer Edward Pellew, 1st Baron Exmouth. He had already been created a baro ...

to allow Earle passage through the Mediterranean aboard ''Scylla'' that Smyth commanded and which was part of Admiral Exmouth's Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

fleet. Earle thus visited Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

and North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, before returning to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

in 1817. A portfolio of drawings from this voyage is held by the National Gallery of Australia

The National Gallery of Australia (NGA), formerly the Australian National Gallery, is the national art museum of Australia as well as one of the largest art museums in Australia, holding more than 166,000 works of art. Located in Canberra in th ...

, Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

.

To the United States

In March 1818, Earle left England, bound for theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

on the first stage of a journey that would end up taking him around-the-world to South America, Tristan da Cunha

Tristan da Cunha (), colloquially Tristan, is a remote group of volcanic islands in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is the most remote inhabited archipelago in the world, lying approximately from Cape Town in South Africa, from Saint Helena ...

, New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, the Pacific, Asia, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label=Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It incl ...

and St Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

before returning home in late 1829. The first leg of Earle's 1818 voyage took him first to New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, before moving on to Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, where he exhibited two paintings at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts

Pennsylvania (; (Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, Maryl ...

. No artworks are known to have survived from this period.

South America

Continuing his voyage in February 1820, Earle sailed forRio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

, Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

, visiting Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

in June and was resident in Lima

Lima ( ; ), originally founded as Ciudad de Los Reyes (City of The Kings) is the capital and the largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rivers, in the desert zone of t ...

, Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

from July to December. On 10 December 1820, Earle left Lima for Rio de Janeiro aboard HMS ''Hyperion''. During the subsequent three years spent in Rio de Janeiro, Earle produced a large number of sketches and watercolours.

A number of the works produced dealt with the subject of

A number of the works produced dealt with the subject of slavery in Brazil

Slavery in Brazil began long before the first Portuguese settlement was established in 1516, with members of one tribe enslaving captured members of another. Later, colonists were heavily dependent on indigenous labor during the initial phases ...

, includin''Punishing negroes at Cathabouco (Calobouco), Rio de Janeiro''

an

''Games at Rio de Janeiro, during the Carnival''

Other works included landscapes and a series of portraits.

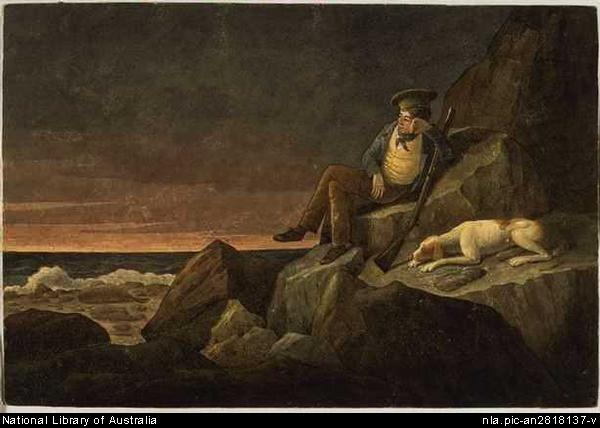

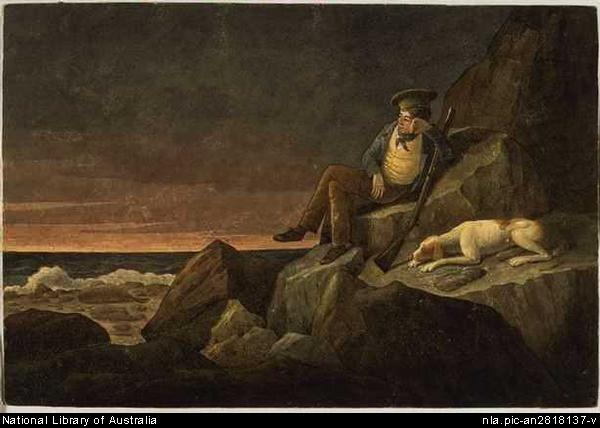

Tristan da Cunha

On 17 February 1824, he left Rio de Janeiro aboard the ageing ship ''Duke of Gloucester'' bound for theCape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is t ...

, and onwards to Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

. Earle's departure was due to a letter containing the 'most flattering offers of introduction to Lord Amherst

Field Marshal Jeffery Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst, (29 January 1717 – 3 August 1797) was a British Army officer and Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in the British Army. Amherst is credited as the architect of Britain's successful campaig ...

, who had just left England to take upon himself the government of India. In the mid-Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

storms forced the ship to anchor off the remote island of Tristan da Cunha. During the ship's stay in the island's waters, Earle went ashore with his dog and a crew member, Thomas Gooch, attracted by the idea that 'this was a spot hitherto unvisited by any artist'. Three days later ''Duke of Gloucester'' inexplicably set sail, leaving Earle and Gooch on the island, which had only six permanent adult inhabitants. In the ensuing eight months of enforced stay on the island, between March and November, Earle became a tutor to several children, and continued to record impressions of the island until his supplies ran out.

Sixteen works survive from the stay on Tristan da Cunha, includin''Government House, Tristan D'Acunha (i.e. da Cunha)''

which was reproduced in his Narrativ

an

''Flinching a young sea elephant''

Australia

Earle was finally rescued on 29 November by the ship , which had stopped off on its voyage toHobart

Hobart ( ; Nuennonne/Palawa kani: ''nipaluna'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian island state of Tasmania. Home to almost half of all Tasmanians, it is the least-populated Australian state capital city, and second-small ...

, Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania used by the British during the European exploration of Australia in the 19th century. A British settlement was established in Van Diemen's Land in 1803 before it became a sepa ...

(in 1856 Van Diemen's Land was renamed Tasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

in honour of Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch seafarer, explorer, and merchant, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first known European explorer to reach New Z ...

) where he landed on 18 January 1825. He remained in Hobart briefly, and only a small number of works survive from this period, his portraits of Captain Richard Brooks and of his wife (1827_1827)hang in the National Gallery of Victoria, includin''June Park, Van Dieman's (sic) Land, perfect park scenery''

an

''Cape Barathas, (i.e. Barathus) Adventure Bay, Van Dieman's (i.e. Diemen's) Land''

Earle left Hobart for

Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

aboard the brig ''Cyprus'', arriving there on 14 May. He soon established a reputation as the colony's first and foremost artist of significance. Upon setting up a small business, Earle received a number of requests for portraits. These commissions came from a number of Sydney's establishment figures and leading families. Throughout this time, Earle also continued to produce a number of watercolour

Watercolor (American English) or watercolour (British English; see spelling differences), also ''aquarelle'' (; from Italian diminutive of Latin ''aqua'' "water"), is a painting method”Watercolor may be as old as art itself, going back to t ...

s which mainly fall into three categories: landscapes, Aboriginal subjects, and a series of views of public and private buildings that record the development of the colony. Earle painted numerous portraits of high-profile colonists including Governor Thomas Brisbane

Major General Sir Thomas Makdougall Brisbane, 1st Baronet, (23 July 1773 – 27 January 1860), was a British Army officer, administrator, and astronomer. Upon the recommendation of the Duke of Wellington, with whom he had served, he was appoint ...

, Governor Ralph Darling

General Sir Ralph Darling, GCH (1772 – 2 April 1858) was a British Army officer who served as Governor of New South Wales from 1825 to 1831. He is popularly described as a tyrant, accused of torturing prisoners and banning theatrical entertain ...

, Captain John Piper and Mrs Piper, with her children. One of his most famous works is a lithographic print entitled ''Portrait of Bungaree

Bungaree, or Boongaree ( – 24 November 1830), was an Aboriginal Australian from the Guringai people of the Broken Bay north of Sydney, who was known as an explorer, entertainer, and Aboriginal community leader.Barani (2013)Significant Aborig ...

, a native of New South Wales, with Fort Macquarie, Sydney Harbour, in background''.

Earle also made several excursions to outlying areas of the colony, travelling north of Sydney via the Hunter River Hunter River may refer to:

*Hunter River (New South Wales), Australia

*Hunter River (Western Australia)

*Hunter River, New Zealand

*Hunter River (Prince Edward Island), Canada

**Hunter River, Prince Edward Island, community on Hunter River, Canada

...

as far as Port Stephens and Port Macquarie

Port Macquarie is a coastal town in the local government area of Port Macquarie-Hastings. It is located on the Mid North Coast of New South Wales, Australia, about north of Sydney, and south of Brisbane. The town is located on the Tasman Sea co ...

and, between April and May 1827, he travelled to the Illawarra

The Illawarra is a coastal region in the Australian state of New South Wales, nestled between the mountains and the sea. It is situated immediately south of Sydney and north of the South Coast region. It encompasses the two cities of Wollongo ...

district south of Sydney. Gaining acceptance within Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

'society' he decided to apply for a land grant, this was denied however, due to his lack of capital.

New Zealand

On 20 October 1827, Earle left Sydney aboard ''Governor Macquarie'' to visit New Zealand, where he had 'hopes of finding something new for my pencil in their peculiar and picturesque style of life'. While Earle was preceded by artists onJames Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

's voyages in the Pacific, including Sydney Parkinson

Sydney Parkinson (c. 1745 – 26 January 1771) was a Scottish botanical illustrator and natural history artist. He was the first European artist to visit Australia, New Zealand and Tahiti. Parkinson was the first Quaker to visit New Zealand.

...

, William Hodges

William Hodges RA (28 October 1744 – 6 March 1797) was an English painter. He was a member of James Cook's second voyage to the Pacific Ocean and is best known for the sketches and paintings of locations he visited on that voyage, inclu ...

and John Webber

John Webber (6 October 1751 – 29 May 1793) was an English artist who accompanied Captain Cook on his third Pacific expedition. He is best known for his images of Australasia, Hawaii and Alaska.

Biography

Webber was born in London, educated ...

, he was the first to take up residence. Earle arrived at Hokianga Harbour

The Hokianga is an area surrounding the Hokianga Harbour, also known as the Hokianga River, a long estuarine drowned valley on the west coast in the north of the North Island of New Zealand.

The original name, still used by local Māori, is ...

on the west coast of the North Island

The North Island, also officially named Te Ika-a-Māui, is one of the two main islands of New Zealand, separated from the larger but much less populous South Island by the Cook Strait. The island's area is , making it the world's 14th-largest ...

, resolving to make his way overland to the Bay of Islands

The Bay of Islands is an area on the east coast of the Far North District of the North Island of New Zealand. It is one of the most popular fishing, sailing and tourist destinations in the country, and has been renowned internationally for its ...

. Setting out with his friend Mr Shand he arrived at Kororareka

Russell, known as Kororāreka in the early 19th century, was the first permanent European settlement and seaport in New Zealand. It is situated in the Bay of Islands, in the far north of the North Island.

History and culture

Māori settle ...

, where he came under the patronage of Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the C ...

chief Te Whareumu

Te Whareumu (died 1828) was the ariki and warrior chief of Ngāti Manu, a hapū within the Ngāpuhi iwi based in the Bay of Islands in New Zealand.

Te Whareumu was the most important chief in the Kororakeka area in his day. He was a warrior c ...

, also known as Shulitea r 'King George' A large number of watercolours and drawings from Earle's New Zealand sojourn remain, covering subjects such as romantic landscapes, Māori culture

Māori culture () is the customs, cultural practices, and beliefs of the indigenous Māori people of New Zealand. It originated from, and is still part of, Polynesians, Eastern Polynesian culture. Māori culture forms a distinctive part of Cul ...

and daily village life, the effects of warfare, portrait studies. He also produced a number of oil painting portraits, along with watercolours, lithographs and pencil sketches. Returning to Hokianga Harbour, he departed from New Zealand for Sydney in April 1828 aboard ''Governor Macquarie''.

To India

Earle then spent close to six months back in Sydney before departing on 12 October 1828, on board the ship ''Rainbow'' bound for India via theCaroline Islands

The Caroline Islands (or the Carolines) are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically, they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in the centra ...

, Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

, one of the Ladrones, Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

, Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

and Pulo-Penang, before disembarking at Madras

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

in India. Although the city of Madras provided a good market for his art Earle's health declined there and he travelled to Pondicherry

Pondicherry (), now known as Puducherry ( French: Pondichéry ʊdʊˈtʃɛɹi(listen), on-dicherry, is the capital and the most populous city of the Union Territory of Puducherry in India. The city is in the Puducherry district on the sout ...

, embarking in the ''Julie'', which was condemned at Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label=Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It incl ...

. After executing panoramic views of the island he returned to England in the Resource in 1830.

Voyage of ''Beagle''

On 28 October 1831 he was engaged by captainRobert FitzRoy

Vice-Admiral Robert FitzRoy (5 July 1805 – 30 April 1865) was an English officer of the Royal Navy and a scientist. He achieved lasting fame as the captain of during Charles Darwin's famous voyage, FitzRoy's second expedition to Tierra de ...

as artist supernumerary with victuals on the second voyage of HMS ''Beagle'', working as topographical artist and draughtsman. He became friends with Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

, and in April and May 1832 they stayed in a cottage at Botafogo

Botafogo (local/standard alternative Brazilian Portuguese pronunciation: ) is a beachfront neighborhood (''bairro'') in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. It is a mostly upper middle class and small commerce community, and is located between the hills of M ...

near Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro ( , , ; literally 'River of January'), or simply Rio, is the capital of the state of the same name, Brazil's third-most populous state, and the second-most populous city in Brazil, after São Paulo. Listed by the GaWC as a b ...

, but problems with his health forced him to leave the ship at Montevideo

Montevideo () is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2011 census, the city proper has a population of 1,319,108 (about one-third of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

in August and return to England. His place on HMS ''Beagle'' was taken over by Conrad Martens

Conrad Martens (21 March 1801 – 21 August 1878) was an English-born landscape painter active on HMS ''Beagle'' from 1833 to 1834. He arrived in Australia in 1835 and painted there until his death in 1878.

Life and work

Conrad Martens' f ...

.

He made paintings from some of his sketches, including ''A Bivouac of Travellers'', which he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1838. This was one of three he made in the Cabbage Tree Forest near Illawarra c. March 1827.

Death

Augustus Earle died, of asthma and debility, in London on 10 December 1838, aged 45.Publications

Augustus Earle, ''A narrative of a nine months' residence in New Zealand in 1827: together with a journal of a residence in Tristan D'Acunha, an island situated between South America and the Cape of Good Hope'' (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman, 1832).

References

*External links

''The Wandering Artist: Augustus Earle's Travels Around The World 1820-29''

a

National Library of Australia

The National Library of Australia (NLA), formerly the Commonwealth National Library and Commonwealth Parliament Library, is the largest reference library in Australia, responsible under the terms of the ''National Library Act 1960'' for "mainta ...

online exhibition

Augustus Earle at Australian Art

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Earle, Augustus 19th-century English painters English male painters English watercolourists Landscape artists 1790s births 1838 deaths 19th-century Australian painters 19th-century English male artists Australian landscape painters