Augusta Savage on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

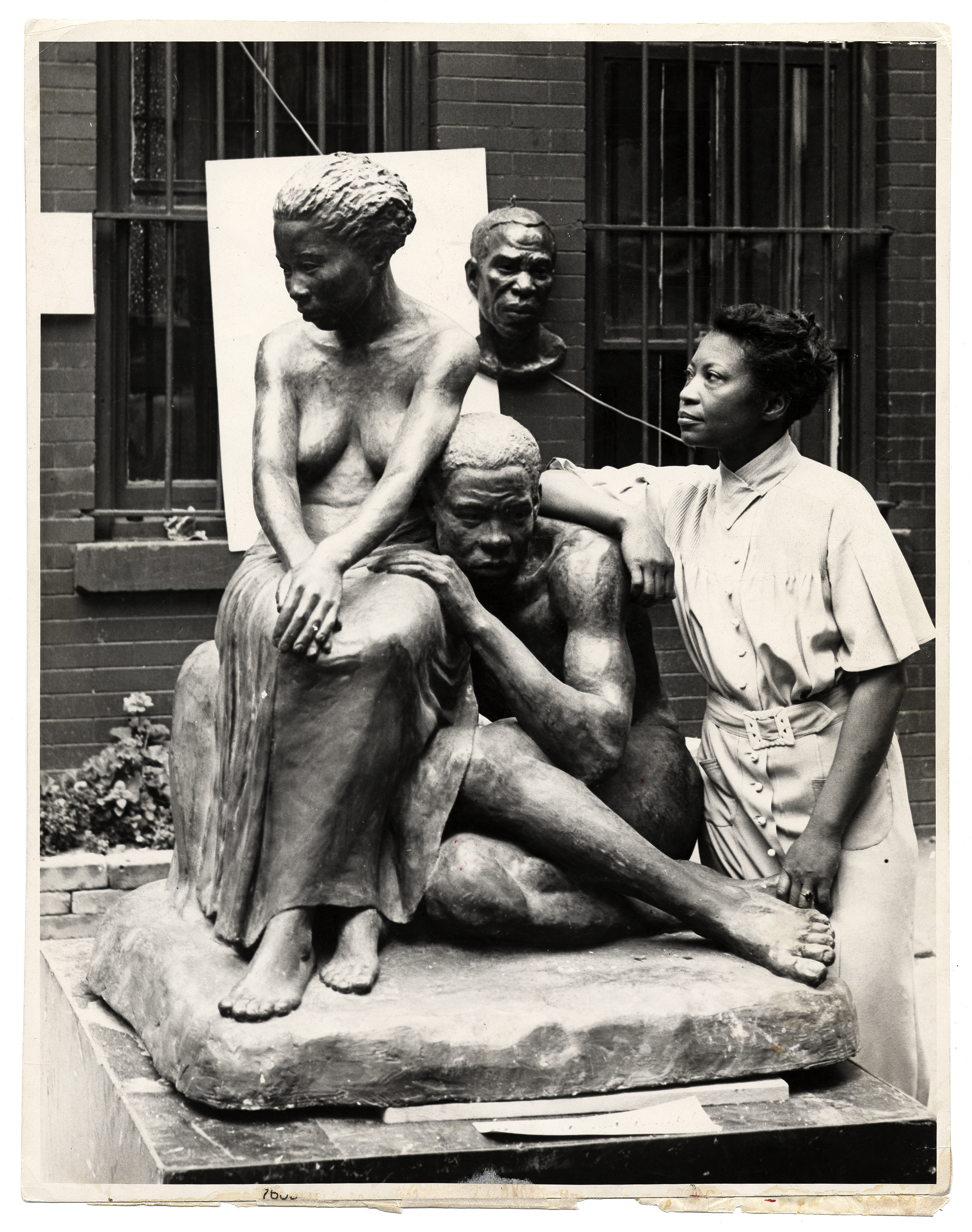

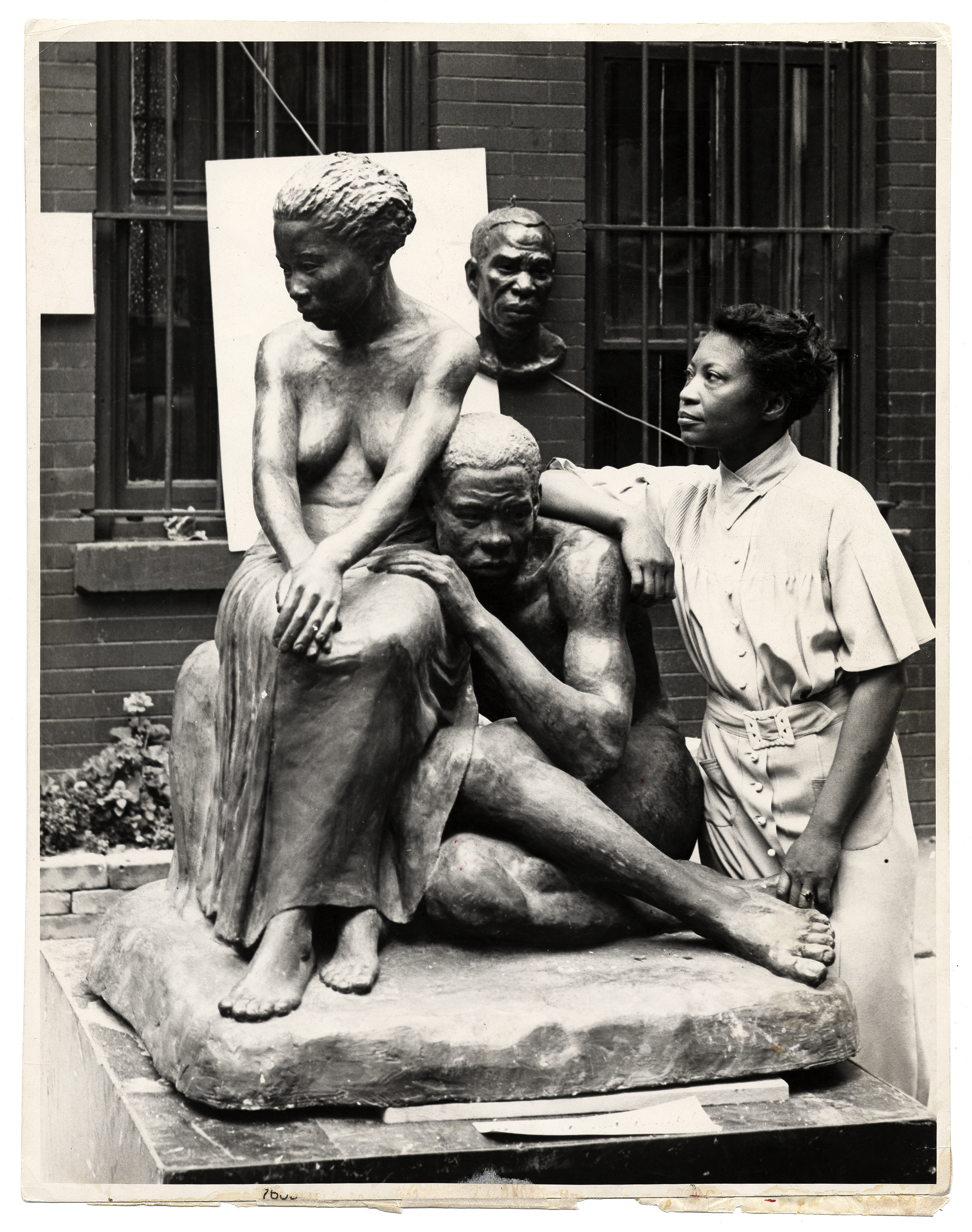

Augusta Savage (born Augusta Christine Fells; February 29, 1892 – March 27, 1962) was an American sculptor associated with the

In 1907, at the age of 15, Augusta Fells married John T. Moore; the two had a daughter, Irene Connie Moore, who was born the following year. John died shortly thereafter. In 1915, after moving to

In 1907, at the age of 15, Augusta Fells married John T. Moore; the two had a daughter, Irene Connie Moore, who was born the following year. John died shortly thereafter. In 1915, after moving to

Savage opened two galleries whose shows were well attended and well reviewed, but few sales resulted and the galleries closed. The last major showing of her work occurred in 1939. Deeply depressed by her financial struggle, Savage moved to a farmhouse in

Savage opened two galleries whose shows were well attended and well reviewed, but few sales resulted and the galleries closed. The last major showing of her work occurred in 1939. Deeply depressed by her financial struggle, Savage moved to a farmhouse in

Augusta Savage: The Woman That Defined 20th Century Sculpture

Gamin

Artnet

Book Rags

Green Cove Spring

Florida Artist Hall of Fame

Augusta Savage

at

Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the t ...

. She was also a teacher whose studio was important to the careers of a generation of artists who would become nationally known. She worked for equal rights for African Americans in the arts.

Early life

Augusta Christine Fells was born inGreen Cove Springs

Green Cove Springs is a city in and the county seat of Clay County, Florida, United States. The population was 5,378 at the 2000 census. As of 2010, the population recorded by the U.S. Census Bureau was 6,908.

The city is named after the porti ...

(near Jacksonville

Jacksonville is a city located on the Atlantic coast of northeast Florida, the most populous city proper in the state and is the List of United States cities by area, largest city by area in the contiguous United States as of 2020. It is the co ...

), Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

, on February 29, 1892, to Edward Fells, a Methodist minister, and Cornelia Murphy. Augusta began making figures as a child, mostly small animals out of the natural red clay of her hometown. Her father was a poor Methodist minister who strongly opposed his daughter's early interest in art. "My father licked me four or five times a week," Savage once recalled, "and almost whipped all the art out of me." This was because he believed her sculpture to be a sinful practice, due to his interpretation of the "graven images" portion of the Bible. She persevered, and the principal of her new high school in West Palm Beach, where her family relocated in 1915, encouraged her talent and allowed her to teach a clay modeling class.Heller, Nancy G., ''Women Artists: An Illustrated History'', Abbeville Press, Publishers, New York 1987 This began a lifelong commitment to teaching, as well as to creating art.

In 1907, at the age of 15, Augusta Fells married John T. Moore; the two had a daughter, Irene Connie Moore, who was born the following year. John died shortly thereafter. In 1915, after moving to

In 1907, at the age of 15, Augusta Fells married John T. Moore; the two had a daughter, Irene Connie Moore, who was born the following year. John died shortly thereafter. In 1915, after moving to West Palm Beach

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sunset, Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic languages, German ...

, she met and married James Savage; she retained the name Savage throughout her life, even after the two divorced in the early 1920s. In 1923, Savage married Robert Lincoln Poston

Robert T. Lincoln Poston (February 25, 1891 – March 16, 1924) was an African-American newspaper editor and journalist, who was an activist in Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). He died at sea as he returned from a UNI ...

, a protégé of Garvey. Poston died of pneumonia aboard a ship while returning from Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

as part of a Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League

The Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) is a black nationalist fraternal organization founded by Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican immigrant to the United States, and Amy Ashwood Garvey. The Pan-African o ...

delegation in 1924.

Education and early career

Savage continued to model clay, and in 1919 was granted a booth at the Palm Beach County Fair where she was awarded a $25 prize and ribbon for most original exhibit. Following this success, she sought commissions for work inJacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville is a city located on the Atlantic coast of northeast Florida, the most populous city proper in the state and is the largest city by area in the contiguous United States as of 2020. It is the seat of Duval County, with which the ...

, before departing for New York City in 1921. She arrived with a letter of recommendation from the Palm Beach County Fair official George Graham Currie for sculptor Solon Borglum

Solon Hannibal de la Mothe Borglum (December 22, 1868 – January 31, 1922) was an American sculptor. He is most noted for his depiction of frontier life, and especially his experience with cowboys and native Americans.

He was awarded the Croix ...

and $4.60. When Borglum discovered that she could not afford tuition at the School of American Sculpture, he encouraged her to apply to Cooper Union

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art (Cooper Union) is a private college at Cooper Square in New York City. Peter Cooper founded the institution in 1859 after learning about the government-supported École Polytechnique in ...

, a scholarship-based school, in New York City where she was admitted in October 1921. She was selected before 142 other men on the waiting list. Her talent and ability impressed the Cooper Union Advisory Council and she was awarded additional funds for room and board after losing the financial support of her job as an apartment caretaker. From 1921 through 1923, she studied under sculptor George Brewster. She completed the four-year degree course in three years.Augusta Savage. By: Kalfatovic, Martin R., American National Biography (from Oxford University Press), 2010

After completing studies at Cooper Union, Savage worked in Manhattan steam laundries to support herself and her family. Her father had been paralyzed by a stroke, and the family's home destroyed by a hurricane. Her family from Florida moved into her small West 137th Street apartment. During this time, she obtained her first commission from the New York Public Library on West 135th Street, a bust of W. E. B. Du Bois. Her outstanding sculpture brought more commissions, including one for a bust of Marcus Garvey

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Sr. (17 August 188710 June 1940) was a Jamaican political activist, publisher, journalist, entrepreneur, and orator. He was the founder and first President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African ...

. Her bust of William Pickens

William Pickens (15 January 1881 – 6 April 1954) was an American orator, educator, journalist, and essayist. He wrote multiple articles and speeches, and penned two autobiographies, first ''The Heir of Slaves'' in 1911 and second ''Bursting Bond ...

Sr., a key figure in the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

, earned praise for depicting an African American in a more humane, neutral way as opposed to stereotypes of the time, as did many of her works.

In the spring of 1923, Savage applied for a summer art program at the Fountainbleau School of Fine Arts in France. She was accepted, however upon finding out that she was black, the American selection committee rescinded the acceptance offer, fearing that the fellow white students would be uncomfortable working alongside a black woman. Savage was deeply upset and questioned the committee, beginning the first of many public fights for equal rights in her life by writing a letter to the ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under publi ...

''. Though appeals were made to the French government to reinstate the award, they had no effect and Savage was unable to study at the school. The incident got press coverage on both sides of the Atlantic, and eventually, the sole supportive committee member sculptor Hermon Atkins MacNeil

Hermon Atkins MacNeil (February 27, 1866 – October 2, 1947) was an American sculptor born in Everett, Massachusetts. He is known for designing the ''Standing Liberty'' quarter, struck by the Mint from 1916-1930; and for sculpting ''Justi ...

– who at one time had shared a studio with African-American artist Henry Ossawa Tanner

Henry Ossawa Tanner (June 21, 1859 – May 25, 1937) was an American artist and the first African-American painter to gain international acclaim. Tanner moved to Paris, France, in 1891 to study at the Académie Julian and gained acclaim in Fren ...

– invited her to study with him. She later cited him as one of her teachers.

In 1923, Savage married Robert Lincoln Poston

Robert T. Lincoln Poston (February 25, 1891 – March 16, 1924) was an African-American newspaper editor and journalist, who was an activist in Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). He died at sea as he returned from a UNI ...

, a protégé of Garvey.Ancestry.com shows Florida Divorce Index dated 1941 for James Savage from Augusta, in Palm Beach County. Poston died of pneumonia aboard a ship while returning from Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

as part of a Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League

The Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL) is a black nationalist fraternal organization founded by Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican immigrant to the United States, and Amy Ashwood Garvey. The Pan-African o ...

delegation in 1924. In 1925, Savage won a scholarship with the help of W.E.B DuBois to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Rome. This scholarship only covered tuition, and after being unable to raise money for travel and living expenses, she was unable to attend. In the 1920s, writer and eccentric Joe Gould became infatuated with Savage. He wrote her "endless letters", telephoned her constantly, and wanted to marry her. Eventually, this infatuation turned into harassment.

Savage won the Otto Kahn Prize in a 1928 exhibition at The Harmon Foundation with her submission ''Head of a Negro''. Yet, she was an outspoken critic of the fetishization of the "negro primitive" aesthetic favored by white patrons at the time. She publicly critiqued the director of The Harmon Foundation, Mary Beattie Brady, for her low standards for Black art and lack of understanding in the area of visual arts in general.

In 1929, with the help of pooled resources from the Urban League

The National Urban League, formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan historic civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of economic and social justice for African Am ...

, Rosenwald Foundation, a Carnegie Foundation grant, and donations from friends and former teachers, Savage was able to travel to France, at age 37. With assistance from the Julius Rosenwald Fund

The Rosenwald Fund (also known as the Rosenwald Foundation, the Julius Rosenwald Fund, and the Julius Rosenwald Foundation) was established in 1917 by Julius Rosenwald and his family for "the well-being of mankind." Rosenwald became part-owner of S ...

, Savage was able to enroll and attend the Académie de la Grande Chaumière

The Académie de la Grande Chaumière is an art school in the Montparnasse district of Paris, France.

History

The school was founded in 1904 by the Catalan painter Claudio Castelucho on the rue de la Grande Chaumière in Paris, near the Acadé ...

, a leading Paris art school. Savage was able to settle into an apartment in Montparnasse and work in the studio of élixBenneteau Desgrois a professor at the school. While the studio was initially encouraging of her work, Savage later wrote that "...the masters are not in sympathy as they all have their own definite ideas and usually wish their pupils to follow their particular method..." and began primarily working on her own in 1930. In Paris, she also studied with the sculptor Charles Despiau

Charles Despiau (November 4, 1874 – October 28, 1946) was a French sculptor.

Early life

Charles-Albert Despiau was born at Mont-de-Marsan, Landes and attended first the École des Arts Décoratifs and later the École nationale supérieure de ...

. She exhibited, and twice won awards, at the Paris Salon

The Salon (french: Salon), or rarely Paris Salon (French: ''Salon de Paris'' ), beginning in 1667 was the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Between 1748 and 1890 it was arguably the greatest annual or biennial art ...

and at one Exposition. She toured France, Belgium, and Germany, researching sculpture in cathedrals and museums.

Later career and teaching

Savage returned to the United States in 1931, energized from her studies and achievements. TheGreat Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

had almost stopped art sales. She pushed on, and in 1934 became the first African-American artist to be elected to the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors

The National Association of Women Artists, Inc. (NAWA) is a United States organization, founded in 1889 to gain recognition for professional women fine artists in an era when that field was strongly male-oriented. It sponsors exhibitions, awards ...

. She launched the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts, located in a basement on West 143rd Street in Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street (Manhattan), 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and 110th Street (Manhattan), ...

, with the help of a grant from the Carnegie Foundation. She opened her studio to anyone who wanted to paint, draw, or sculpt. Her many young students included the future nationally known artists of Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Armstead Lawrence (September 7, 1917 – June 9, 2000) was an American painter known for his portrayal of African-American historical subjects and contemporary life. Lawrence referred to his style as "dynamic cubism", although by his own ...

, Norman Lewis, and Gwendolyn Knight

Gwendolyn Clarine Knight (May 26, 1913 – February 18, 2005) was an American artist who was born in Bridgetown, Barbados, in the West Indies.

Knight painted throughout her life but did not start seriously exhibiting her work until the 1970s. He ...

. Another student was the sociologist Kenneth B. Clark

Kenneth Bancroft Clark (July 24, 1914 – May 1, 2005) and Mamie Phipps Clark (April 18, 1917 – August 11, 1983) were American psychologists who as a married team conducted research among children and were active in the Civil Rights Movement. T ...

, whose later research contributed to the 1954 Supreme Court decision in ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segrega ...

'' that ruled school segregation unconstitutional. In 1937, Savage became the director of the Harlem Community Art Center; 1,500 people of all ages and abilities participated in her workshops, learning from her multi-cultural staff, and showing work around New York City. Funds from the Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; renamed in 1939 as the Work Projects Administration) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to carry out public works projects, i ...

helped, but old struggles of discrimination were revived between Savage and WPA officials who objected to her having a leadership role.

Savage was one of four women and only two African Americans to receive a professional commission from the Board of Design to be included in the 1939 New York World's Fair

The 1939–40 New York World's Fair was a world's fair held at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park in Queens, New York, United States. It was the second-most expensive American world's fair of all time, exceeded only by St. Louis's Louisiana Purchas ...

. Savage was commissioned to create a sculpture showcasing the impact that Black people have had on music. She created ''Lift Every Voice and Sing

"Lift Every Voice and Sing" is a hymn with lyrics by James Weldon Johnson (1871–1938) and set to music by his brother, J. Rosamond Johnson (1873–1954). Written from the context of African Americans in the late 19th century, the hymn is a pray ...

'' (also known as "The Harp"), inspired by the song by James Weldon and Rosamond Johnson. The 16-foot-tall plaster

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for Molding (decorative), moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of ...

sculpture stood in front of the Contemporary Arts Building and was one of the most popular and most photographed work at the fair; small metal souvenir copies were sold, and many postcards of the piece were purchased. The work reinterpreted the musical instrument by featuring 12 singing African-American youth in graduated heights as its strings, with the harp's sounding board transformed into an arm and a hand. In the front, a kneeling young man offered music in his hands. Savage did not have funds to have the piece cast in bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

or to move and store it, and so like other temporary installations, the sculpture was destroyed at the close of the fair.

Savage opened two galleries whose shows were well attended and well reviewed, but few sales resulted and the galleries closed. The last major showing of her work occurred in 1939. Deeply depressed by her financial struggle, Savage moved to a farmhouse in

Savage opened two galleries whose shows were well attended and well reviewed, but few sales resulted and the galleries closed. The last major showing of her work occurred in 1939. Deeply depressed by her financial struggle, Savage moved to a farmhouse in Saugerties, New York

Saugerties () is a town in the northeastern corner of Ulster County, New York. The population was 19,038 at the time of the 2020 Census, a decline from 19,482 in 2010. The village of the same name is located entirely within the town.

Part ...

, in 1945. While in Saugerties, she established close ties with her neighbors and welcomed family and friends from New York City to her rural home. Savage cultivated a garden and sold pigeons, chickens, and eggs. The K-B Products Corporation, the world's largest growers of mushrooms at that time, employed Savage as a laboratory assistant in the company's cancer research facility. She acquired a car and learned to drive to enable her commute. Herman K. Knaust, director of the laboratory, encouraged Savage to pursue her artistic career and provided her with art supplies. Though her art production slowed down, Savage taught art to children in summer camps and sculpted friends and tourists, and explored writing children's stories. Her last commissioned work was for Knaust and was that of the American journalist and author Poultney Bigelow, whose father, John, was U.S. Minister to France during the Civil War. Her few neighbors said that she was always making something with her hands.

Much of her work is in clay or plaster, as she could not often afford bronze. One of her most famous busts is titled ''Gamin'' which is on permanent display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

The Smithsonian American Art Museum (commonly known as SAAM, and formerly the National Museum of American Art) is a museum in Washington, D.C., part of the Smithsonian Institution. Together with its branch museum, the Renwick Gallery, SAAM holds o ...

in Washington, D.C.; a life-sized version is in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art

The Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) is an art museum in Cleveland, Ohio, located in the Wade Park District, in the University Circle neighborhood on the city's east side. Internationally renowned for its substantial holdings of Asian and Egyptian ...

. At the time of its creation, ''Gamin'', which is modeled after a Harlem youth, was voted most popular in an exhibition of over 200 works by black artists. Her style can be described as realistic, expressive, and sensitive. Though her art and influence within the art community are documented, the location of much of her work is unknown.

Savage moved in with her daughter, Irene, in New York City when her health started to decline, she later died of cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

on March 26, 1962. While she died in relative obscurity, Savage is remembered today as a great artist, activist, and arts educator; serving as an inspiration to the many that she taught, helped, and encouraged.

Stalking by Joe Gould

In 1923, at a poetry reading in Harlem, Savage met the Greenwich Village writer Joe Gould.Jill Lepore, ''Joe Gould's Teeth'' (New York: Knopf, 2016) Gould claimed to be working on the longest book ever written, ''The Oral History of Our Time''. He became obsessed with Savage, writing to her constantly, and proposing marriage. This obsession, which seems to have been violent, and may have involved rape, lasted for more than two decades. During those years, Gould was arrested several times for attacking women. He was in and out of psychiatric hospitals, where he was eventually diagnosed as psychopathic. In 1942, when the ''New Yorker'' writer Joseph Mitchell profiled Gould for the magazine, he portrayed him as a harmless eccentric. Gould died in 1957, in a psychiatric hospital, likely after having been lobotomized in 1949. In 1964, in a ''New Yorker'' essay called "Joe Gould's Secret," Mitchell revealed his conviction that ''The Oral History of Our Time'' never existed and had been, all along, a product of Gould's insanity. After the article was published, the writerMillen Brand

Millen Brand (January 19, 1906 – March 19, 1980) was an American writer and poet. His novels, ''The Outward Room'' (1938) and ''Savage Sleep'' (1968), addressed mental health institutions and were bestsellers in their day.

Personal life

B ...

, a friend of Savage's, wrote to Mitchell to tell him that he was wrong, that the ''Oral History'' did exist, reporting that "Joe ould Ould is an English surname and an Arabic name ( ar, ولد). In some Arabic dialects, particularly Hassaniya Arabic, ولد (the patronymic, meaning "son of") is transliterated as Ould. Most Mauritanians have patronymic surnames.

Notable p ...

showed me long sections of the ''Oral History'' that were actually oral history ... the longest stretch of it, running through several composition books and much the longest thing probably that he ever wrote, was his account of Augusta Savage." Brand told Mitchell that Savage had been terrified of Gould but, as a Black woman, was unable to get help from the police. Mitchell never reported any of this, but ''New Yorker'' writer Jill Lepore

Jill Lepore is an American historian and journalist. She is the David Woods Kemper '41 Professor of American History at Harvard University and a staff writer at ''The New Yorker'', where she has contributed since 2005. She writes about American ...

, drawing from evidence in the Millen Brand Papers at Columbia and the Joseph Mitchell papers, then newly deposited at the New York Public Library, told the story in a 2016 book called ''Joe Gould's Teeth'' in which she speculated that Savage left New York in 1939 to escape Gould.

Legacy

The Augusta Fells Savage Institute of Visual Arts, a Baltimore, Maryland, public high school, is named in her honor. In 2001 her home and studio in Saugerties, New York, were listed on the New York State and National Register of Historic Places as the Augusta Savage House and Studio. It is the most significant surviving site associated with the productive life of this renowned artist, teacher, and activist. Her home has been restored to evoke the period when she lived there, and serves to interpret her life and creative vision. In 2007, the City of Green Cove Springs, Florida, nominated her to theFlorida Artist Hall of Fame Florida Artists Hall of Fame recognizes artists who have made significant contributions to art in Florida. It was established by the Florida Legislature in 1986. There is a Florida Artists Hall of Fame Wall on the Plaza Level in the rotunda of the ...

; she was inducted the Spring of 2008. Today, at the actual location of her birth, there is a Community Center named in her honor.

A biography of Savage intended for younger readers has been written by Alan Schroeder. ''In Her Hands: The Story of Sculptor Augusta Savage'' was released in September 2009 by Lee and Low, a New York publishing company.

The papers of Savage are available at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture

The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture is a research library of the New York Public Library (NYPL) and an archive repository for information on people of African descent worldwide. Located at 515 Malcolm X Boulevard (Lenox Avenue) b ...

at New York Public Library.

Works

* Portrait busts of W.E.B. DuBois andMarcus Garvey

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Sr. (17 August 188710 June 1940) was a Jamaican political activist, publisher, journalist, entrepreneur, and orator. He was the founder and first President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African ...

* ''Gamin''

* ''The Tom Tom''

* ''The Abstract Madonna''

* ''Envy''

* ''A Woman of Martinique''

* ''Lift Every Voice and Sing

"Lift Every Voice and Sing" is a hymn with lyrics by James Weldon Johnson (1871–1938) and set to music by his brother, J. Rosamond Johnson (1873–1954). Written from the context of African Americans in the late 19th century, the hymn is a pray ...

'' (also known as ''The Harp'')

* ''Sculptural interpretation of Negro Music''

* ''Gwendolyn Knight'', 1934–35

Individual exhibitions

* Grande Chaumière, Paris, 1929 *Salon d'Automne

The Salon d'Automne (; en, Autumn Salon), or Société du Salon d'automne, is an art exhibition held annually in Paris, France. Since 2011, it is held on the Champs-Élysées, between the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais, in mid-October. The f ...

, Paris, 1930

* Argent Galleries, New York and Art Anderson Gallery, New York, 1932

* Argent Galleries, New York and New York World's Fair, 1939

* New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress ...

, 1988

Selected group exhibitions

* Argent Galleries, New York, 1934 * Argent Galleries, New York, 1938 * ''American Negro Exposition

The American Negro Exposition, also known as the Black World's Fair and the Diamond Jubilee Exposition, was a world's fair held in Chicago from July until September in 1940, to celebrate the 75th anniversary (also known as a diamond jubilee) of t ...

'', Tanner Art Galleries, Chicago, 1940

* Newark Museum

The Newark Museum of Art (formerly known as the Newark Museum), in Newark, Essex County, New Jersey, United States, is the state's largest museum. It holds major collections of American art, decorative arts, contemporary art, and arts of Asia, Af ...

, New Jersey, 1990

* ''Three Generations of African-American Women Sculptors'', Afro-American Historical and Cultural Museum, Philadelphia, 1996

References

Further reading

*Farris, Phoebe, ed. (1999). ''Women Artists of Color : A bio-critical sourcebook to 20th century artists in the Americas''. Greenwood Press. , pp. 272, 339–344. * *Etinde-Crompton, Charlotte, Crompton, Samuel Willard (2019) ''Augusta Savage: Sculptor of the Harlem Renaissance''. *''DailyArt Magazine''Augusta Savage: The Woman That Defined 20th Century Sculpture

External links

Gamin

Artnet

Book Rags

Green Cove Spring

Florida Artist Hall of Fame

Augusta Savage

at

Find a Grave

Find a Grave is a website that allows the public to search and add to an online database of cemetery records. It is owned by Ancestry.com. Its stated mission is "to help people from all over the world work together to find, record and present fin ...

* Profile on NPR Morning edition 7/15/19

{{DEFAULTSORT:Savage, Augusta

African-American sculptors

American women sculptors

1892 births

1962 deaths

Alumni of the Académie de la Grande Chaumière

Cooper Union alumni

People from Green Cove Springs, Florida

Sculptors from Florida

20th-century American sculptors

Harlem Renaissance

Federal Art Project artists

20th-century American women artists

National Association of Women Artists members