Atlantis of the Sands on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Atlantis of the Sands refers to a legendary lost city in the southern deserts of the Arabian Peninsula, thought to have been destroyed by a natural disaster or as a punishment by God. The search for it was popularised by the 1992 book ''Atlantis of the Sands – The Search for the Lost City of Ubar'' by

Atlantis of the Sands refers to a legendary lost city in the southern deserts of the Arabian Peninsula, thought to have been destroyed by a natural disaster or as a punishment by God. The search for it was popularised by the 1992 book ''Atlantis of the Sands – The Search for the Lost City of Ubar'' by

In March 1948 a geological party from Petroleum Development (Oman and Dhofar) Ltd, an associate company of the

In March 1948 a geological party from Petroleum Development (Oman and Dhofar) Ltd, an associate company of the

Atlantis of the Sands refers to a legendary lost city in the southern deserts of the Arabian Peninsula, thought to have been destroyed by a natural disaster or as a punishment by God. The search for it was popularised by the 1992 book ''Atlantis of the Sands – The Search for the Lost City of Ubar'' by

Atlantis of the Sands refers to a legendary lost city in the southern deserts of the Arabian Peninsula, thought to have been destroyed by a natural disaster or as a punishment by God. The search for it was popularised by the 1992 book ''Atlantis of the Sands – The Search for the Lost City of Ubar'' by Ranulph Fiennes

Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes, 3rd Baronet (born 7 March 1944), commonly known as Sir Ranulph Fiennes () and sometimes as Ran Fiennes, is a British explorer, writer and poet, who holds several endurance records.

Fiennes served in the ...

. Apart from the English name, coined by T. E. Lawrence

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918 ...

, the city is commonly also called Ubar, Wabar or Iram.

Introduction

In modern times, the mystery of the lost city ofAtlantis

Atlantis ( grc, Ἀτλαντὶς νῆσος, , island of Atlas) is a fictional island mentioned in an allegory on the hubris of nations in Plato's works '' Timaeus'' and '' Critias'', wherein it represents the antagonist naval power that b ...

has generated a number of books, films, articles, web pages, and two Disney

The Walt Disney Company, commonly known as Disney (), is an American multinational mass media and entertainment conglomerate headquartered at the Walt Disney Studios complex in Burbank, California. Disney was originally founded on October ...

features. On a smaller scale, Arabia has its own legend of a lost city, the so-called "Atlantis of the Sands", which has been the source of debate among historians, archaeologists and explorers, and a degree of controversy that continues to this day.

In February 1992, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' announced a major archaeological discovery in the following terms: "Guided by ancient maps and sharp-eyed surveys from space, archaeologists and explorers have discovered a lost city deep in the sands of Arabia, and they are virtually sure it is Ubar, the fabled entrepôt

An ''entrepôt'' (; ) or transshipment port is a port, city, or trading post where merchandise may be imported, stored, or traded, usually to be exported again. Such cities often sprang up and such ports and trading posts often developed into c ...

of the rich frankincense trade thousands of years ago." When news of this discovery spread quickly around the newspapers of the world, there seemed few people willing or able to challenge the dramatic findings, apart from the Saudi Arabian press.

The discovery was the result of the work of a team of archaeologists led by Nicholas Clapp, which had visited and excavated the site of a Bedouin well at Shisr (18° 15' 47 N" 53° 39' 28" E) in Dhofar

The Dhofar Governorate ( ar, مُحَافَظَة ظُفَار, Muḥāfaẓat Ẓufār) is the largest of the 11 Governorates in the Sultanate of Oman in terms of area. It lies in Southern Oman, on the eastern border with Yemen's Al Mahrah G ...

province, Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

. The conclusion they reached, based on site excavations and an inspection of satellite photographs, was that this was the site of Ubar, or Iram of the Pillars

Iram of the Pillars ( ar, إرَم ذَات ٱلْعِمَاد, ; an alternative translation is ''Iram of the tentpoles''), also called "Irum", "Irem", "Erum", "Ubar", or the "City of the pillars", is considered a lost city, region or tribe men ...

, a name found in the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , s ...

which may be a lost city, a tribe or an area.

Sir Ranulph Fiennes

Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes, 3rd Baronet (born 7 March 1944), commonly known as Sir Ranulph Fiennes () and sometimes as Ran Fiennes, is a British explorer, writer and poet, who holds several endurance records.

Fiennes served in the ...

, another member of the expedition, declared that this was Omanum Emporium of Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

's famous map of Arabia Felix

Arabia Felix (literally: Fertile/Happy Arabia; also Ancient Greek: Εὐδαίμων Ἀραβία, ''Eudaemon Arabia'') was the Latin name previously used by geographers to describe South Arabia, or what is now Yemen.

Etymology

The term Arabia ...

.

A contemporary notice at the entrance to an archaeological site at Shisr in the province of Dhofar, Oman, proclaims: "Welcome to Ubar, the Lost City of Bedouin Legend". However, scholars are divided over whether this really is the site of a legendary lost city of the sands.

Early explorers in Dhofar

In 1930, the explorerBertram Thomas

Bertram Sidney Thomas (13 June 1892 – 27 December 1950) was an English diplomat and explorer who is the first documented Westerner to cross the Rub' al Khali (Empty Quarter). He was also a scientist who practiced craniofacial anthropome ...

had been approaching the southern edge of the Rub' al Khali

The Rub' al KhaliOther standardized transliterations include: / . The ' is the assimilated Arabic definite article, ', which can also be transliterated as '. (; ar, ٱلرُّبْع ٱلْخَالِي (), the "Empty Quarter") is the sand de ...

("The Empty Quarter"). It was Thomas' ambition to be the first European to cross the great sands but, as he began his camel journey, he was told by his Bedouin escorts of a lost city whose wicked people had attracted the wrath of God and had been destroyed. He found no trace of a lost city in the sands, but Thomas later related the story to T. E. Lawrence

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 – 19 May 1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916–1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915–1918 ...

("Lawrence of Arabia"), who regarded Ubar as the "Atlantis of the Sands". Thomas marked on a map the location of a track that was said to lead to the legendary lost city of Ubar and, although he intended to return to follow it, he was never able to.

The story of a lost city in the sands became an explorer's fascination; a few wrote accounts of their travels that perpetuated the tale. T. E. Lawrence planned to search for the location of a lost city somewhere in the sands, telling a fellow traveller that he was convinced that the remains of an Arab civilization were to be found in the desert. He had been told that the Bedu had seen the ruins of the castles of King Ad in the region of Wabar. In his view the best way to explore the sands was by airship, but his plans never came to fruition.

The English explorer Wilfred Thesiger

Sir Wilfred Patrick Thesiger (3 June 1910 – 24 August 2003), also known as Mubarak bin Landan ( ar, مُبَارَك بِن لَنْدَن, ''the blessed one of London'') was a British military officer, explorer, and writer.

Thesiger's trav ...

visited the well at Shisr in the spring of 1946, "where the ruins of a crude stone fort on a rocky eminence marks the position of this famous well." He noted that some shards found there were possibly early Islamic. The well was the only permanent watering place in those parts and, being a necessary watering place for Bedouin raiders, had been the scene of many fierce encounters in the past,

In March 1948 a geological party from Petroleum Development (Oman and Dhofar) Ltd, an associate company of the

In March 1948 a geological party from Petroleum Development (Oman and Dhofar) Ltd, an associate company of the Iraq Petroleum Company

The Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC), formerly known as the Turkish Petroleum Company (TPC), is an oil company that had a virtual monopoly on all oil exploration and production in Iraq between 1925 and 1961. It is jointly owned by some of the worl ...

, carried out a camel-borne survey of Dhofar province. Like Thesiger, the party approached Shisr from the south, along the Wadi Ghudun. Their first sight of Ash Shisur was a white cliff in the distance. As they drew closer, they could see that the cliff was in fact the wall of a ruined fort built above a large quarry-like cave, the entrance of which was obscured by a sand dune.

The fort had been built from the same white rock as the overhanging cliff, giving the impression of a single structure. One of the geologists noted: "There are no houses, tents or people here: only the tumble-down ruin of this pre-Islamic fort." The geologists, without the benefit of modern satellite analysis or archaeological equipment, were unimpressed by the ruin. Shisur, like Ma Shedid a few days before, was a 'difficult water' and their escorts spent the best part of their 3-day stay trying to extract water for their camels from the well.

In 1953, oil man and philanthropist Wendell Phillips

Wendell Phillips (November 29, 1811 – February 2, 1884) was an American abolitionist, advocate for Native Americans, orator, and attorney.

According to George Lewis Ruffin, a Black attorney, Phillips was seen by many Blacks as "the one whi ...

set out to discover Thomas' track but was unable to follow it because of the heavy sands which made further travel by motor transport impossible.

Some 35 years later, Clapp and his team reported uncovering what they described as a large octagonal fortress dating back some 2,000 years beneath the crumbling fort, and described a vast limestone table that lay beneath the main gate which had collapsed into a massive sinkhole around the well. This, some concluded, was the fabled city of Ubar, which was also known as Iram, or at least a city in the region of Ubar, once an important trading post on the incense route from Dhofar to the Mediterranean region.

Some pointed to religious texts to support the theory that the city was destroyed as a punishment by God. Iram, for example, was described in the Qur'an as follows: "Have you not considered how your Lord dealt with 'Aad - ith

The Ith () is a ridge in Germany's Central Uplands which is up to 439 m high. It lies about 40 km southwest of Hanover and, at 22 kilometres, is the longest line of crags in North Germany.

Geography

Location

The Ith is immediatel ...

Iram - who had lofty pillars, The like of which were not produced in (all) the land?" ( Surat al-Fajr: 6–8)

Theories about the location

Dhofar

Bertram Thomas' guide pointed to wide tracks between the dunes and said: "Look, Sahib, there is the way to Ubar. It was great in treasure, with date gardens and a fort of red silver. It now lies beneath the sands of the Ramlat Shu’ait." Thomas also wrote, "on my previous journeys I had heard from other Arabs of the name of this Atlantis of the Sands, but none could tell me of even an approximate location."Rub' al-Khali

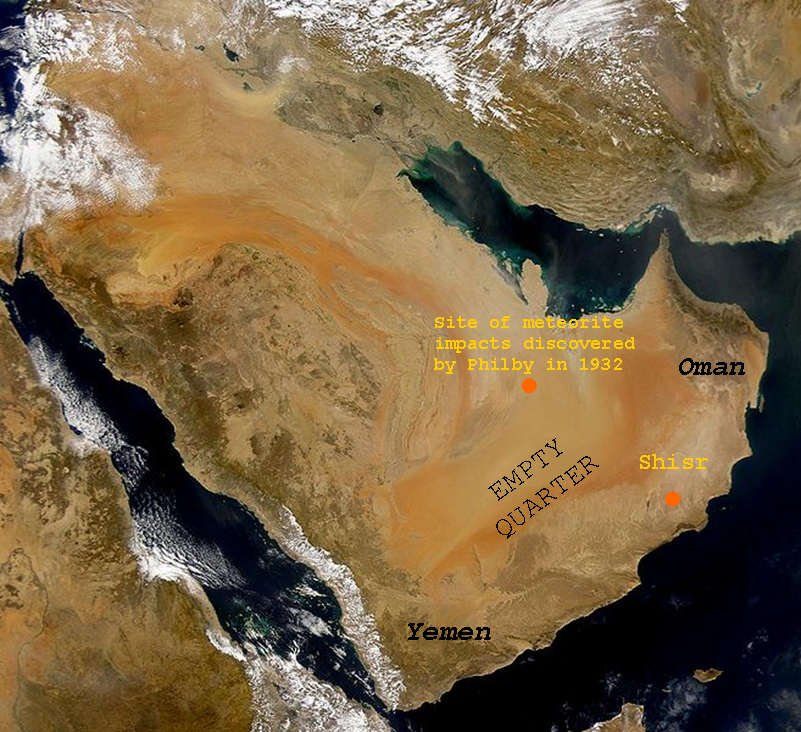

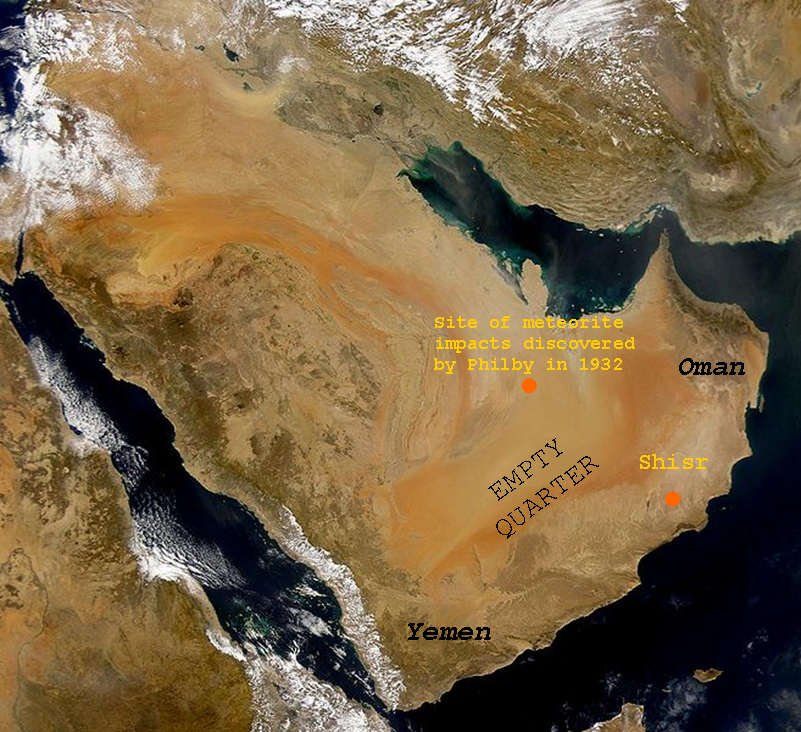

Most tales of the lost city locate it somewhere in theRub' al Khali

The Rub' al KhaliOther standardized transliterations include: / . The ' is the assimilated Arabic definite article, ', which can also be transliterated as '. (; ar, ٱلرُّبْع ٱلْخَالِي (), the "Empty Quarter") is the sand de ...

desert, also known as the Empty Quarter, a vast area of sand dunes covering most of the southern third of the Arabian Peninsula, including most of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the A ...

and parts of Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

, the United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates (UAE; ar, اَلْإِمَارَات الْعَرَبِيَة الْمُتَحِدَة ), or simply the Emirates ( ar, الِْإمَارَات ), is a country in Western Asia ( The Middle East). It is located at t ...

, and Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

.

St. John Philby (who preferred the name "Wabar" for the lost city) was an English adviser to Emir Aziz bin Saud in Riyadh

Riyadh (, ar, الرياض, 'ar-Riyāḍ, lit.: 'The Gardens' Najdi pronunciation: ), formerly known as Hajr al-Yamamah, is the capital and largest city of Saudi Arabia. It is also the capital of the Riyadh Province and the centre of th ...

. He first heard the story of Ubar from his Bedouin guide, who told him about a place of ruined castles where King Ad had stabled his horses and housed his women before being punished for his sinful ways by being destroyed by fire from heaven.

Anxious to seal his reputation as a great explorer, Philby went in search of the lost city of Wabar but, instead of finding ruins, discovered what he described as an extinct volcano half-buried in the sands or, possibly, the remnants of a meteorite impact

An impact event is a collision between astronomical objects causing measurable effects. Impact events have physical consequences and have been found to regularly occur in planetary systems, though the most frequent involve asteroids, comets or m ...

. Modern research has confirmed an ancient impact event as the cause of the depression in the sands.

Geologist H. Stewart Edgell observed that for the "last six thousand years the Empty Quarter has been continuously a sand-dune desert, presenting a hostile environment where no city could have been built."

Shisr

Nicholas Clapp claimed that the discovery of the remains of towers at the Shisr excavation site supported the theory that this was the site of Ubar, the city of 'Ad with "lofty pillars" described in the Qur'an. Thomas dismissed the ruins at the well of Ash Shisur as a "rude" fort which he took to be only a few hundred years old.Omanum Emporium

Ranulph Fiennes

Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes, 3rd Baronet (born 7 March 1944), commonly known as Sir Ranulph Fiennes () and sometimes as Ran Fiennes, is a British explorer, writer and poet, who holds several endurance records.

Fiennes served in the ...

, explorer and adventurer, was a member of Clapp's expedition and speculated that Ubar was identified on ancient maps as "Omanum Emporium". This was a place marked on a map of Arabia compiled by Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importa ...

in about 150 AD.

Others

When the explorerFreya Stark

Dame Freya Madeline Stark (31 January 18939 May 1993), was a British-Italian explorer and travel writer. She wrote more than two dozen books on her travels in the Middle East and Afghanistan as well as several autobiographical works and essays ...

consulted the works of Arab geographers, she found a wide range of opinions as to the location of Wabar: " Yaqut says: "In Yemen is the qaria of Wabar." El-Laith, quoted by Yaqut, puts it between the sands of Yabrin Yabrin is a settlement in Saudi Arabia south of Riyadh, within the Eastern Region. The closest town is Haradh. The area was an abandoned ancient settlement. In the 1940s it began to be resettled by Bedouins mostly with a Dawasir background.

The e ...

and Yemen. Ibn Ishaq… places it between "Sabub (unknown to Yaqut and Hamdani) and the Hadhramaut

Hadhramaut ( ar, حَضْرَمَوْتُ \ حَضْرَمُوتُ, Ḥaḍramawt / Ḥaḍramūt; Hadramautic: 𐩢𐩳𐩧𐩣𐩩, ''Ḥḍrmt'') is a region in South Arabia, comprising eastern Yemen, parts of western Oman and southern Saud ...

". Hamdani, a very reliable man, places it between Najran, Hadhramaut, Shihr

Ash-Shihr ( ar, ٱلشِّحْر, al-Shiḥr), also known as al-Shir or simply Shihr, is a coastal town in Hadhramaut, eastern Yemen.

Ash-Shihr is a walled town located on a sandy beach. There is an anchorage but no docks; boats are used. The mai ...

and Mahra. Yaqut, presumably citing Hamdani, puts it between the boundaries of Shihr and Sanaʽa

Sanaa ( ar, صَنْعَاء, ' , Yemeni Arabic: ; Old South Arabian: 𐩮𐩬𐩲𐩥 ''Ṣnʿw''), also spelled Sana'a or Sana, is the capital and largest city in Yemen and the centre of Sanaa Governorate. The city is not part of the Govern ...

, and then, on the authority of Abu Mundhir between the sands of B.Sa'd (near Yabrin) and Shihr and Mahra. Abu Mundhir puts it between Hadhramaut and Najran."

"With such evidence," Stark concluded, "it seems quite possible for Mr. Thomas and Mr. Philby each to find Wabar in an opposite corner of Arabia."

The Shisr discoveries

Nicholas Clapp's search for Ubar began after he read Thomas' book ''Arabia Felix''. Clapp had just returned from Oman, having helped to stock an oryx sanctuary on the Jiddat al Harassis, and was inspired by Thomas' references to the lost city of Ubar. He began his search for Ubar in the library of theUniversity of California in Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the California St ...

, and found a 2nd-century AD map by the Alexandrian geographer Claudius Ptolemy which showed a place called "Omanum Emporium". He speculated that this might be the location of Ubar, situated on the incense route between Dhofar and the Mediterranean region. Aware that Mayan remains had been identified from aerial photographs, Clapp contacted NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and obtained satellite images of Dhofar. These helped to identify ancient camel tracks hidden beneath the shifting sands of the desert which in turn might identify places of convergence such as wells and ancient cities.

After Clapp's team had visited a number of possible sites for Ubar, they found themselves drawn back to the crumbling ruin at Shisr. Although the fort had been written off as being no more than a few hundred years old by the earlier explorers, Clapp's team began to speculate that the fort had been rebuilt in the 1500s on the remains of a far more ancient site.

Under the direction of Juris Zarins, the team began excavation, and within weeks had unearthed the wall and towers of a fortress dating back more than 2,000 years. Clapp suggested that the evidence was "a convincing match" for the legendary lost city of Ubar. The city's destruction, he postulated, happened between A.D. 300 and 500 as the result of an earthquake which precipitated the collapse of the limestone table; but it was the decline of the incense trade, which led to the decline of the caravan routes through Shisr, that sealed Ubar's fate.

Zarins himself concluded that Shisr did not represent a city called Ubar. In a 1996 interview on the subject of Ubar, he said:

In a more recent paper he suggested that modern Habarut may be the site of Ubar.

By 2007, following further research and excavation, their findings could be summarised as follows:

* A long period of widespread trade through the area of Shisr was indicated by artefacts from Persia, Rome, and Greece being found on the site. More recent work in Oman and Yemen indicated that this fortress was the easternmost remains of a series of desert caravanserais

A caravanserai (or caravansary; ) was a roadside inn where travelers ( caravaners) could rest and recover from the day's journey. Caravanserais supported the flow of commerce, information and people across the network of trade routes covering ...

that supported incense trade.

* As far as the legend of Ubar was concerned, there was no evidence that the city had perished in a sandstorm. Much of the fortress had collapsed into a sinkhole that hosted the well, perhaps undermined by the removal of ground water for irrigation.

* Rather than being a city, interpretation of the evidence suggested that "Ubar" was more likely to have been a region—the "Land of the Iobaritae" identified by Ptolemy. The decline of the region was probably due to a reduction in the frankincense trade caused by the conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity, which did not require incense in the same quantities for its rituals. Also, it became difficult to find local labour to collect the resin. Climatic changes led to desiccation of the area, and sea transport became a more reliable way of transporting goods.

* The archaeological importance of the site was highlighted by satellite imagery that revealed a network of trails, some of which passed underneath sand dunes 100 m tall, which converged on Shisr. Image analysis showed no further evidence of major undocumented sites in this desert region, which might be considered as alternate locations for the Ubar of legend.

Critical reception

The Saudi Arabian press was generally sceptical about the discovery of Ubar in Oman, with Abdullah al Masri, Assistant Under-Secretary of Archaeological Affairs stating that similar sites had been found in Saudi Arabia over the past 15 years. In ''Ashawq al Awsat'' he explained: "The best of these sites was when, in 1975, we uncovered more than one city on the edge of the Empty Quarter, in particular the oasis on Jabreen. Also the name of Ubar is similar to that of Obar, an oasis in eastern Saudi Arabia. We must await further details but so far we have far more important discoveries at Jabreen or Najran." However, Professor Mohammed Bakalla of King Saud University wrote that he would not be surprised if Ad's nation cities were found underneath the Shisr excavation or in the close vicinity. More recent academic opinion is less than convinced about the accuracy of Clapp's findings. One reviewer noted that Clapp himself did not help matters by including a speculative chapter about the king of Ubar in his book, ''The Road to Ubar'', which in his view undermined his narrative authority: "its fictional drama pales next to the gripping real-life story of the Ubar expedition recounted in earlier portions of this volume." The case for Shisr being Omanum Emporium has been questioned by recent research. Nigel Groom commented in an article "Oman and the Emirates in Ptolemy's Map" published in 2007, that Ptolemy's map of Arabia contained many wild distortions. The word "Emporium" in the original Greek meant a place for wholesale trade of commodities carried by sea, and was sometimes an inland city where taxes were collected and trade conducted. Thus the term could be applied to a town that was some distance from the coast. This, Groom suggests, may have been the case with Ptolemy's 'Omanum Emporium'. He suggested that the Hormanus River, the source of which is marked on Ptolemy's map as being north-east of Omanus Emporium, was in fact the Wadi Halfrain which rises some 20 kilometres north east of Izki in modern-day central Oman. Thus, Groom concludes, Omanum Emporium was likely to have been located at Izki, possibly Nizwa, or in their vicinity. H. Stewart Edgell contended that Ubar is essentially mythical and makes arguments against any significant historical role for Shisr beyond that of a small caravanserai. Edgell suggested that the building was small and used by a few families at most. He believed that all the "discovery" of Ubar showed was how easily scientists can succumb to wishful thinking. In an article on the Shisr excavations Professor Barri Jones wrote: "The archaeological integrity of the site should not be allowed to be affected by possible disputes regarding its name." A 2001 report forUNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

states: "The Oasis of Shisr and the entrepots of Khor Rori

Khawr Rawrī ( ar, خور روري) or Khor Rori is a bar-built estuary (or river mouth lagoon) at the mouth of Wādī Darbāt in the Dhofar Governorate, Oman, near Taqah. It is a major breeding ground for birds, and used to act as an important ...

and Al-Balid are outstanding examples of medieval fortified settlements in the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bod ...

region."

Writing about 'Wabbar', Michael Macdonald expressed doubts about the "discovery" since the site was known for decades and Sir Ranulph was stationed there.

See also

*Atlantis in popular culture

The island of Atlantis has often been depicted in literature, television shows, films and works of popular culture.

Fiction

Start of genre fiction

Before 1900 there was an overlap between verse epics dealing with the fall of Atlantis a ...

*Antillia

Antillia (or Antilia) is a phantom island that was reputed, during the 15th-century age of exploration, to lie in the Atlantic Ocean, far to the west of Portugal and Spain. The island also went by the name of Isle of Seven Cities (''Ilha das S ...

*Avalon

Avalon (; la, Insula Avallonis; cy, Ynys Afallon, Ynys Afallach; kw, Enys Avalow; literally meaning "the isle of fruit r appletrees"; also written ''Avallon'' or ''Avilion'' among various other spellings) is a mythical island featured in the ...

*Cantre'r Gwaelod

, also known as or ( en, The Lowland Hundred), is a legendary ancient sunken kingdom said to have occupied a tract of fertile land lying between Ramsey Island and Bardsey Island in what is now Cardigan Bay to the west of Wales. It has been ...

*Brasil (mythical island)

Brasil, also known as Hy-Brasil and several other variants, is a phantom island said to lie in the Atlantic Ocean west of Ireland. Irish myths described it as cloaked in mist except for one day every seven years, when it becomes visible but ...

*Brittia

Brittia (), according to Procopius, was an island known to the inhabitants of the Low Countries under Frankish rule (viz. the North Sea coast of Austrasia), corresponding both to a real island used for burial and a mythological Isle of the Bles ...

*Lemuria (continent)

Lemuria (), or Limuria, was a continent proposed in 1864 by zoologist Philip Sclater, theorized to have sunk beneath the Indian Ocean, later appropriated by occultists in supposed accounts of human origins. The theory was discredited with the dis ...

* Mayda

* Mu (lost continent)

*Mythical place

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narrati ...

*Saint Brendan's Island

Saint Brendan's Island, also known as Saint Brendan's Isle, is a phantom island or mythical island, supposedly situated in the North Atlantic somewhere west of Northern Africa. It is named after Saint Brendan of Clonfert. He and his followers a ...

*Sandy Island, New Caledonia

Sandy Island (sometimes labelled in French , and in Spanish ) is a non-existent island that was charted for over a century as being located near the French territory of New Caledonia between the Chesterfield Islands and Nereus Reef in the ...

*Thule

Thule ( grc-gre, Θούλη, Thoúlē; la, Thūlē) is the most northerly location mentioned in ancient Greek and Roman literature and cartography. Modern interpretations have included Orkney, Shetland, northern Scotland, the island of Saar ...

* Ys

General:

* Doggerland

Doggerland was an area of land, now submerged beneath the North Sea, that connected Britain to continental Europe. It was flooded by rising sea levels around 6500–6200 BCE. The flooded land is known as the Dogger Littoral. Geological sur ...

* Lost lands

Lost lands are islands or continents believed by some to have existed during pre-history, but to have since disappeared as a result of catastrophic geological phenomena.

Legends of lost lands often originated as scholarly or scientific theo ...

* Kumari Kandam

Kumari Kandam is a mythical continent, believed to be lost with an ancient Tamil civilization, supposedly located south of present-day India in the Indian Ocean. Alternative names and spellings include ''Kumarikkandam'' and ''Kumari Nadu''.

...

* Minoan eruption

References

External links

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Atlantis of the Sands: the Search for a Lost City in Southern Arabia Arabian mythology History of the Arabian Peninsula Destroyed cities Mythological populated places One Thousand and One Nights Former populated places in Southwest Asia Archaeological sites in Oman