Atlantic Raid Of June 1796 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Atlantic raid of June 1796 was a short campaign containing three connected minor naval engagements fought in the

At 02:00 in the morning of 8 June, the remaining ships of the French squadron were sailing approximately southeast of the

At 02:00 in the morning of 8 June, the remaining ships of the French squadron were sailing approximately southeast of the

While ''Tamise'' and ''Tribune'' met their fates in the Channel, ''Proserpine'' had continued unmolested to the cruising ground off the

While ''Tamise'' and ''Tribune'' met their fates in the Channel, ''Proserpine'' had continued unmolested to the cruising ground off the ' s sails and damaged the rigging, but Beauclerk's ship continued to gain on ''Proserpine'' until at 21:00 Beauclerk was close enough to open fire with his main broadside. Some damage was done to the sails and rigging of ''Dryad'' in the exchange and at one point the ship's colours were shot away and had to be replaced, but casualties were light. On ''Proserpine'' casualties mounted quickly, and although her sails and rigging remained largely intact, significant damage to the hull and heavy losses among the crew convinced Pevrieux to surrender at 21:45.Woodman, p.79

As in the previous engagements, the French ship had a much larger crew, (346 to 254), although weight of shot ( to ) and size (1059 bm to 924 bm) were more evenly distributed. Casualties displayed the same inequalities as in the earlier engagements, with two killed and seven wounded on ''Dryad'' but 30 killed and 45 wounded on ''Proserpine''.Clowes, p.500 In James' opinion, had Pevrieux opted to use his initial advantage of the

Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

comprising Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

efforts to eliminate a squadron of French frigates

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

operating against British commerce during the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

. Although Royal Navy dominance in the Western Atlantic had been established, French commerce raiders operating on short cruises were having a damaging effect on British trade, and British frigate squadrons regularly patrolled from Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

in search of the raiders. One such squadron comprised the 36-gun frigates HMS ''Unicorn'' and HMS ''Santa Margarita'', patrolling in the vicinity of the Scilly Isles

The Isles of Scilly (; kw, Syllan, ', or ) is an archipelago off the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England. One of the islands, St Agnes, is the most southerly point in Britain, being over further south than the most southerly point of the ...

, which encountered a French squadron comprising the frigates ''Tribune'' and ''Tamise'' and the corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the slo ...

''Légėre''.

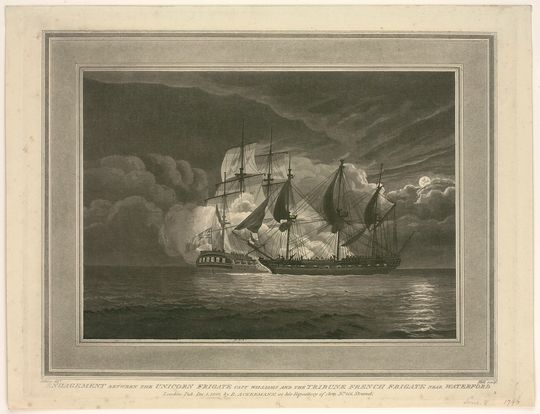

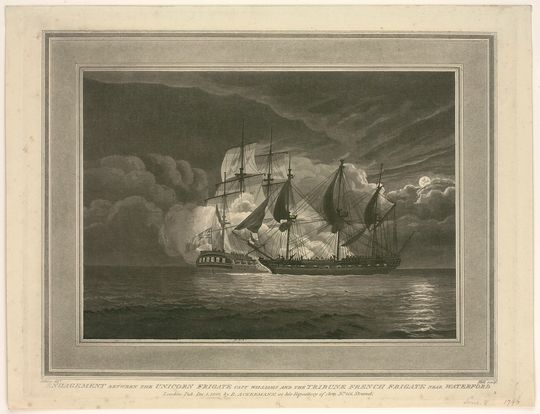

The opposing forces were approximately equal in size, but the French, under orders to operate against commerce, not engage British warships, attempted to retreat. The British frigates pursued closely and over the course of the day gradually overhauled the French squadron. At 16:00 ''Santa Margarita'' caught ''Tamise'' and a furious duel ensued in which the smaller ''Tamise'' was badly damaged and eventually forced to surrender. ''Tribune'' continued its efforts to escape, but was finally caught by ''Unicorn'' at 22:30 and defeated in a second hard-fought engagement. ''Légėre'' took no part in the action and was able to withdraw without becoming embroiled in either conflict.

Five days later the French frigate ''Proserpine'', which had separated from the rest of the squadron after leaving Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

*Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

*Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

**Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Brest, ...

, was searching for her compatriots off Cape Clear in Southern Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

when she was discovered by the patrolling British frigate HMS ''Dryad''. ''Dryad'' successfully chased down ''Proserpine'' and forced the French ship to surrender in an engagement lasting 45 minutes. Nine days later ''Légėre'' was captured without a fight by another British frigate patrol. French casualties in all three engagements were very heavy, while British losses were light. In the aftermath all four captured ships were purchased for service in the Royal Navy.

Background

The first three years of the conflict betweenGreat Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

and the new French Republic

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

in the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

, which began in 1793, had resulted in a series of setbacks for the French Atlantic Fleet, based at the large fortified port of Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

*Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

*Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

**Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Brest, ...

. In 1794 seven French ships of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which depended on the two colum ...

had been lost at the battle of the Glorious First of June

The Glorious First of June (1 June 1794), also known as the Fourth Battle of Ushant, (known in France as the or ) was the first and largest fleet action of the naval conflict between the Kingdom of Great Britain and the First French Republic ...

, and early the following year five more were wrecked by winter storms during the disastrous ''Croisière du Grand Hiver

The ''Croisière du Grand Hiver'' (French "Campaign of the Great Winter") was a French attempt to organise a winter naval campaign in the wake of the Glorious First of June.

Context

The Glorious First of June had ended on a strategic success f ...

'' campaign. In June 1795 three more ships were captured by the British Channel Fleet

The Channel Fleet and originally known as the Channel Squadron was the Royal Navy formation of warships that defended the waters of the English Channel from 1854 to 1909 and 1914 to 1915.

History

Throughout the course of Royal Navy's history the ...

at the Battle of Groix

The Battle of Groix was a large naval engagement which took place near the island of Groix off the Biscay coast of Brittany on 23 June 1795 ( 5 messidor an III) during the French Revolutionary Wars. The battle was fought between elements of the ...

.Gardiner, p.16 With the French fleet consolidating at Brest, the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

instituted a policy of close blockade

A blockade is the act of actively preventing a country or region from receiving or sending out food, supplies, weapons, or communications, and sometimes people, by military force.

A blockade differs from an embargo or sanction, which are le ...

, maintaining a fleet off the port to intercept any efforts by the main French battle fleet to sail. The French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

instead embarked on a strategy of interference with British commerce, the majority of which by necessity passed through the Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

and the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

. This campaign was conducted principally by privateers

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

and small squadrons of frigates

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

operating from Brest and other smaller ports on the French Atlantic and Channel coasts.Gardiner, p.140

The French commerce raiding operations had some success against British trade, and to counteract these attacks the Royal Navy formed squadrons of fast frigates, which patrolled the Channel and Bay of Biscay

The Bay of Biscay (), known in Spain as the Gulf of Biscay ( es, Golfo de Vizcaya, eu, Bizkaiko Golkoa), and in France and some border regions as the Gulf of Gascony (french: Golfe de Gascogne, oc, Golf de Gasconha, br, Pleg-mor Gwaskogn), ...

in search of the French warships.Gardiner, p.51 This resulted in a series of engagements between British and French frigate squadrons, including a notable battle on 23 April 1794,James, p.201 and two actions by a squadron under the command of Commodore Sir Edward Pellew

Admiral Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth, GCB (19 April 1757 – 23 January 1833) was a British naval officer. He fought during the American War of Independence, the French Revolutionary Wars, and the Napoleonic Wars. His younger brother Is ...

on 13 April

Events Pre-1600

*1111 – Henry V is crowned Holy Roman Emperor.

* 1204 – Constantinople falls to the Crusaders of the Fourth Crusade, temporarily ending the Byzantine Empire.

1601–1900

*1612 – In one of the epic samurai ...

and 20 April 1796 fought in the mouth of the Channel.Brenton, p.241 The southern coast of Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, in the Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland ( ga, label=Classical Irish, an Ríoghacht Éireann; ga, label=Modern Irish, an Ríocht Éireann, ) was a monarchy on the island of Ireland that was a client state of England and then of Great Britain. It existed from ...

, a British client state

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite state, ...

, was seen as a particularly vulnerable region due to its proximity to the trade routes and its numerous isolated anchorages in which French ships could shelter. To counteract this threat, a Royal Navy frigate squadron was stationed in Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

under the command of Rear-Admiral Robert Kingsmill. Ships from this squadron patrolled the mouth of the Channel, singly or in pairs, in search of French raiders.Woodman, p.77

On 4 June 1796, a French squadron was dispatched from Brest on a raiding cruise. This force included the 40-gun frigates ''Tribune'' under Franco-American Commodore Jean Moulston, ''Proserpine'' under Captain Etienne Pevrieux and ''Tamise'' under Captain Jean-Baptiste-Alexis Fradin, the latter formerly a Royal Navy ship named HMS ''Thames'' which had been captured in an engagement in the Bay of Biscay by a French frigate squadron in October 1793. With the frigates was the 18-gun corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the slo ...

''Légėre'' under Lieutenant Jean Michel-Martin Carpentier. ''Tamise'' in particular had proven a highly effective commerce raider, recorded as capturing twenty merchant ships since her enforced change of allegiance. ''Proserpine'' separated from the other ships during a period of heavy fog

Fog is a visible aerosol consisting of tiny water droplets or ice crystals suspended in the air at or near the Earth's surface. Reprint from Fog can be considered a type of low-lying cloud usually resembling stratus, and is heavily influ ...

on 7 June, sailing independently to the rendezvous off Cape Clear in Southern Ireland.James, p.328

''Tamise'' and ''Tribune''

At 02:00 in the morning of 8 June, the remaining ships of the French squadron were sailing approximately southeast of the

At 02:00 in the morning of 8 June, the remaining ships of the French squadron were sailing approximately southeast of the Scilly Isles

The Isles of Scilly (; kw, Syllan, ', or ) is an archipelago off the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England. One of the islands, St Agnes, is the most southerly point in Britain, being over further south than the most southerly point of the ...

when sails were sighted distant. This was a small British frigate squadron from Kingsmill's command comprising the 36-gun HMS ''Unicorn'' under Captain Thomas Williams and HMS ''Santa Margarita'' under Captain Thomas Byam Martin

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Thomas Byam Martin, (25 July 1773 – 25 October 1854) was a Royal Navy officer. As captain of fifth-rate HMS ''Fisgard'' he took part in a duel with the French ship ''Immortalité'' and captured her at the Batt ...

, sent to patrol the area in search of French raiders. The British frigates had just seized a Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

merchant ship carrying Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

contraband

Contraband (from Medieval French ''contrebande'' "smuggling") refers to any item that, relating to its nature, is illegal to be possessed or sold. It is used for goods that by their nature are considered too dangerous or offensive in the eyes o ...

from Surinam Surinam may refer to:

* Surinam (Dutch colony) (1667–1954), Dutch plantation colony in Guiana, South America

* Surinam (English colony) (1650–1667), English short-lived colony in South America

* Surinam, alternative spelling for Suriname

...

, which they sent to Cork under a prize crew and immediately set sail to intercept the French, who turned away, sailing in line ahead. ''Tribune'' led the line, a much faster ship than either of her consorts, holding back for mutual support, but as the morning passed and the British ships drew closer and closer ''Légėre'' fell out of the line to windward. Both British frigates passed the corvette at distance, although the smaller vessel remained in sight for sometime, eventually departing to attack a merchant sloop

A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast typically having only one headsail in front of the mast and one mainsail aft of (behind) the mast. Such an arrangement is called a fore-and-aft rig, and can be rigged as a Bermuda rig with triangular sa ...

sailing nearby.

At 13:00 the British frigates were close enough that both ''Tamise'' and ''Tribune'' could open fire with their stern-chasers, inflicting considerable damage to the sails and rigging of the British ships and causing them to fall back despite occasional fire from the British bow-chasers. This tactic bought the French frigates three hours, but at 16:00 it became clear that the slower ''Tamise'' would be overhauled by ''Santa Margarita''; Williams had already instructed Martin to focus on ''Tamise'' as he intended to attack the larger ''Tribune'' himself. Under fire from Martin's ship and wishing to both avoid this conflict and hoping to inflict severe damage on ''Santa Margarita'', Fradin turned away from the former and across the bows of the latter, intending to rake

Rake may refer to:

* Rake (stock character), a man habituated to immoral conduct

* Rake (theatre), the artificial slope of a theatre stage

Science and technology

* Rake receiver, a radio receiver

* Rake (geology), the angle between a feature on a ...

''Santa Margarita''. In response Martin brought his frigate alongside ''Tamise''. Running at speed away from their compatriots, ''Tamise'' and ''Santa Margarita'' exchanged broadside

Broadside or broadsides may refer to:

Naval

* Broadside (naval), terminology for the side of a ship, the battery of cannon on one side of a warship, or their near simultaneous fire on naval warfare

Printing and literature

* Broadside (comic ...

s for 20 minutes until Fradin, his ship badly damaged and his crew suffering heavy casualties, was forced to strike his colours

Striking the colors—meaning lowering the flag (the "colors") that signifies a ship's or garrison's allegiance—is a universally recognized indication of surrender, particularly for ships at sea. For a ship, surrender is dated from the time the ...

.

As ''Tamise'' and ''Santa Margarita'' fought, ''Unicorn'' continued the pursuit of ''Tribune''. Without the need to support the slower ''Tamise'', Moulston was able to spread more sail and ''Tribune'' pulled ahead of her opponent during the afternoon the ships passing Tuskar Rock on the Wexford

Wexford () is the county town of County Wexford, Ireland. Wexford lies on the south side of Wexford Harbour, the estuary of the River Slaney near the southeastern corner of the island of Ireland. The town is linked to Dublin by the M11/N11 N ...

Coast. The French frigate's stern-chasers continued to inflict damage on ''Unicorn''s rigging, at one point snatching away the main topsail and it was only when night fell, and the wind with it, that Williams was able to gain on the French ship through the use of studding sails. At 22:30, following a chase of northwards into St George's Channel

St George's Channel ( cy, Sianel San Siôr, ga, Muir Bhreatan) is a sea channel connecting the Irish Sea to the north and the Celtic Sea to the southwest.

Historically, the name "St George's Channel" was used interchangeably with "Irish Sea" ...

, ''Unicorn'' was finally able to pull alongside ''Tribune''. For 35 minutes the frigates battered at one another from close range. Under cover of smoke, Moulston then attempted to escape by pulling ''Tribune'' back and turning across ''Unicorn''s stern, seeking to rake the British frigate and move to windward. Realising Moulston's intent, Williams hauled his sails around, effectively throwing ''Unicorn'' in reverse. As the British ship sailed suddenly backwards she crossed ''Tribune''s bow, raking the French ship with devastating effect.Woodman, p.78 From this vantage point the fire from ''Unicorn'' succeeded in collapsing the foremast and mainmast on ''Tribune'' and shooting away the mizen topmast, rendering the French ship unmanageable. With no hope of escape and casualties rapidly mounting, the wounded Moulston surrendered to Williams.James, p.330

The engagements were relatively evenly matched: ''Tamise'' and ''Santa Margarita'' carried similar weight of shot ( to ) although ''Tamise'' had seventy more crew members (306 to 237) and ''Santa Margarita'' was slightly more than a third larger (993 bm to 656 bm). Naval historian William James

William James (January 11, 1842 – August 26, 1910) was an American philosopher, historian, and psychologist, and the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States.

James is considered to be a leading thinker of the lat ...

credits ''Santa Margarita''s larger size as giving her the advantage.James, p.329 In the second action, ''Tribune'' also had a much larger crew than ''Unicorn'' (339 to 240) and was substantially larger (916 bm to 791 bm), but ''Unicorn'', equipped with 18-pounder long gun

The 18-pounder long gun was an intermediary calibre piece of naval artillery mounted on warships of the Age of Sail. They were used as main guns on the most typical frigates of the early 19th century, on the second deck of third-rate ships of the ...

s, massed a far larger weight of shot ( to ), which proved decisive. Both engagements saw similar casualty ratios, with ''Tamise'' losing 32 killed and 19 wounded, some of whom later died, and ''Tribune'' suffering 37 killed and 15 wounded, including Moulston, while losses on ''Santa Margarita'' and ''Unicorn'' were two killed and three wounded and none at all respectively.Clowes, p.498–499

''Proserpine''

While ''Tamise'' and ''Tribune'' met their fates in the Channel, ''Proserpine'' had continued unmolested to the cruising ground off the

While ''Tamise'' and ''Tribune'' met their fates in the Channel, ''Proserpine'' had continued unmolested to the cruising ground off the Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

coast. At 01:00 on 13 June, southeast of Cape Clear Island, Pevrieux' crew sighted a sail approaching from the northeast. Pevrieux was searching for Moulston's squadron, and allowed his ship to close with the newcomer before discovering that it was the patrolling 36-gun British frigate HMS ''Dryad'' under Captain Lord Amelius Beauclerk

Admiral (Royal Navy), Admiral Lord Amelius Beauclerk (23 May 1771 – 10 December 1846) was a Royal Navy Officer (armed forces), officer.

Early life

Beauclerk was born on 23 May 1771, the third son of Aubrey Beauclerk, 5th Duke of St Albans ...

.James, p.331 On realising the danger, Pevrieux tacked away from ''Dryad'' and attempted to escape to the southwest. This chase lasted most of the day, Beauclerk gradually gaining on his opponent until Pevrieux opened fire with his stern-chaser guns at 20:00.

Shot from the stern-chasers punched holes in ''Dryad''weather gage

The weather gage (sometimes spelled weather gauge) is the advantageous position of a fighting sailing vessel relative to another. It is also known as "nautical gauge" as it is related to the sea shore. The concept is from the Age of Sail and is now ...

to attack ''Dryad'' directly rather than attempt to escape he might have been able to defeat the British frigate.James, p.332

Aftermath

The last survivor of the squadron, ''Légėre'', remained at sea for another nine days, capturing six merchant ships, before the corvette was intercepted at in the Western Approaches by the frigates HMS ''Apollo'' under CaptainJohn Manley

John Paul Manley (born January 5, 1950) is a Canadian lawyer, businessman, and politician who served as the eighth deputy prime minister of Canada from 2002 to 2003. He served as Liberal Member of Parliament for Ottawa South from 1988 to 2 ...

and HMS ''Doris'' under Captain Charles Jones. All of the captured ships were taken to Britain and were subsequently purchased for the Royal Navy, ''Tamise'' restored as HMS ''Thames'', ''Tribune'' with the same name, ''Proserpine'' as HMS ''Amelia'' as there was already an HMS ''Proserpine'' in service, and ''Légėre'' anglicised as HMS ''Legere''.James, p.333

As the senior captain in the operation, Williams was subsequently knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

, although historian Tom Wareham considered that Martin's fight had been the harder-fought encounter. Wareham also considered that Beauclerk may not have been rewarded as he was already a member of the nobility.Wareham, p.57 Historian James Henderson considered that Martin may not have been honoured for the engagement due to his youth: he was 23 years old at the time of the battle.Henderson, p.74 The first lieutenants

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

on each British ship were promoted to commanders

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

and Commander Joseph Bullen, volunteering on board ''Santa Margarita'', was promoted to post captain

Post-captain is an obsolete alternative form of the rank of Captain (Royal Navy), captain in the Royal Navy.

The term served to distinguish those who were captains by rank from:

* Officers in command of a naval vessel, who were (and still are) ...

. More than five decades later, the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

* Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

* Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

*Admiralty, Tr ...

recognised the actions with the clasps "SANTA MARGARITA 8 JUNE 1796", "UNICORN 8 JUNE 1796" and "DRYAD 13 JUNE 1796" attached to the Naval General Service Medal, awarded upon application to all British participants still living in 1847.

Following the capture of Moulston's squadron there was little activity in the English Channel or Bay of Biscay almost to the end of the year. On 22 August

Events Pre-1600

* 392 – Arbogast has Eugenius elected Western Roman Emperor.

* 851 – Battle of Jengland: Erispoe defeats Charles the Bald near the Breton town of Jengland.

*1138 – Battle of the Standard between Scotland ...

a squadron under Sir John Borlase Warren

Admiral Sir John Borlase Warren, 1st Baronet (2 September 1753 – 27 February 1822) was a British Royal Navy officer, diplomat and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1774 and 1807.

Naval career

Born in Stapleford, Nottinghamsh ...

drove ashore and destroyed the French frigate ''Andromaque'' at the Gironde

Gironde ( US usually, , ; oc, Gironda, ) is the largest department in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region of Southwestern France. Named after the Gironde estuary, a major waterway, its prefecture is Bordeaux. In 2019, it had a population of 1,62 ...

,Brenton, p.242 and on 24 October ''Santa Margarita'' successfully chased down and captured two heavily armed privateers in the same region as the action in June.James, p.359 In December 1796 however, after the British fleet had retired to Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

for the winter, the main French fleet sailed from Brest for the first time since June 1795 on a major operation named the ''Expédition d'Irlande

The French expedition to Ireland, known in French as the ''Expédition d'Irlande'' ("Expedition to Ireland"), was an unsuccessful attempt by the French Republic to assist the outlawed Society of United Irishmen, a popular rebel Irish republica ...

'', a planned invasion of Ireland. Like their winter campaign of two years previously, and for much the same reasons, this ended in disaster with 12 ships wrecked or captured and thousands of soldiers and sailors drowned without a single successful landing.Clowes, pp.298–303

Notes

References

* * * * * * * {{cite book , last = Woodman , first = Richard , author-link = Richard Woodman , year = 2001 , title = The Sea Warriors , publisher = Constable Publishers , location = London , isbn = 1-84119-183-3 Naval battles of the French Revolutionary Wars Conflicts in 1796 Naval battles involving France Naval battles involving Great Britain