Atlantic Puffin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Atlantic puffin ('), also known as the common puffin, is a

The characteristic bright orange bill plates and other facial characteristics develop in the spring. At the close of the breeding season, these special coatings and appendages are shed in a partial moult. This makes the beak appear less broad, the tip less bright, and the base darker grey. The eye ornaments are shed and the eyes appear round. At the same time, the feathers of the head and neck are replaced and the face becomes darker. This winter plumage is seldom seen by humans because when they have left their chicks, the birds head out to sea and do not return to land until the next breeding season. The juvenile bird is similar to the adult in plumage, but altogether duller with a much darker grey face and yellowish-brown beak tip and legs. After fledging, it makes its way to the water and heads out to sea, and does not return to land for several years. In the interim, each year, it will have a broader bill, paler face patches, and brighter legs and beaks.

The Atlantic puffin has a direct flight, typically above the sea surface and higher over the water than most other auks. It mostly moves by paddling along efficiently with its webbed feet and seldom takes to the air. It is typically silent at sea, except for the soft purring sounds it sometimes makes in flight. At the breeding colony, it is quiet above ground, but in its burrow makes a growling sound somewhat resembling a chainsaw being revved up.

The characteristic bright orange bill plates and other facial characteristics develop in the spring. At the close of the breeding season, these special coatings and appendages are shed in a partial moult. This makes the beak appear less broad, the tip less bright, and the base darker grey. The eye ornaments are shed and the eyes appear round. At the same time, the feathers of the head and neck are replaced and the face becomes darker. This winter plumage is seldom seen by humans because when they have left their chicks, the birds head out to sea and do not return to land until the next breeding season. The juvenile bird is similar to the adult in plumage, but altogether duller with a much darker grey face and yellowish-brown beak tip and legs. After fledging, it makes its way to the water and heads out to sea, and does not return to land for several years. In the interim, each year, it will have a broader bill, paler face patches, and brighter legs and beaks.

The Atlantic puffin has a direct flight, typically above the sea surface and higher over the water than most other auks. It mostly moves by paddling along efficiently with its webbed feet and seldom takes to the air. It is typically silent at sea, except for the soft purring sounds it sometimes makes in flight. At the breeding colony, it is quiet above ground, but in its burrow makes a growling sound somewhat resembling a chainsaw being revved up.

Since the Atlantic puffin spends its winters on the open ocean, it is susceptible to human actions and catastrophes such as oil spills. Oiled plumage has a reduced ability to insulate and makes the bird more vulnerable to temperature fluctuations and less buoyant in the water. Many birds die, and others, while attempting to remove the oil by preening, ingest and inhale toxins. This leads to inflammation of the airways and gut and in the longer term, damage to the liver and kidneys. This trauma can contribute to a loss of reproductive success and harm to developing embryos. An oil spill occurring in winter, when the puffins are far out at sea, may affect them less than inshore birds as the crude oil slicks soon get broken up and dispersed by the churning of the waves. When oiled birds get washed up on beaches around Atlantic coasts, only about 1.5% of the dead auks are puffins, but many others may have died far from land and sunk. After the oil tanker shipwreck and oil spill in 1967, few dead puffins were recovered, but the number of puffins breeding in France the following year was reduced to 16% of its previous level.

The Atlantic puffin and other pelagic birds are excellent bioindicators of the environment, as they occupy a high trophic level. Heavy metals and other pollutants are concentrated through the food chain, and as fish are the primary food source for Atlantic puffins, the potential is great for them to bioaccumulate heavy metals such as mercury and arsenic. Measurements can be made on eggs, feathers, or internal organs, and beached bird surveys, accompanied by chemical analysis of feathers, can be effective indicators of

Since the Atlantic puffin spends its winters on the open ocean, it is susceptible to human actions and catastrophes such as oil spills. Oiled plumage has a reduced ability to insulate and makes the bird more vulnerable to temperature fluctuations and less buoyant in the water. Many birds die, and others, while attempting to remove the oil by preening, ingest and inhale toxins. This leads to inflammation of the airways and gut and in the longer term, damage to the liver and kidneys. This trauma can contribute to a loss of reproductive success and harm to developing embryos. An oil spill occurring in winter, when the puffins are far out at sea, may affect them less than inshore birds as the crude oil slicks soon get broken up and dispersed by the churning of the waves. When oiled birds get washed up on beaches around Atlantic coasts, only about 1.5% of the dead auks are puffins, but many others may have died far from land and sunk. After the oil tanker shipwreck and oil spill in 1967, few dead puffins were recovered, but the number of puffins breeding in France the following year was reduced to 16% of its previous level.

The Atlantic puffin and other pelagic birds are excellent bioindicators of the environment, as they occupy a high trophic level. Heavy metals and other pollutants are concentrated through the food chain, and as fish are the primary food source for Atlantic puffins, the potential is great for them to bioaccumulate heavy metals such as mercury and arsenic. Measurements can be made on eggs, feathers, or internal organs, and beached bird surveys, accompanied by chemical analysis of feathers, can be effective indicators of

The Atlantic puffin is the official bird symbol of the province of

The Atlantic puffin is the official bird symbol of the province of

species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

of seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adaptation, adapted to life within the marine ecosystem, marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent ...

in the auk

Auks or alcids are birds of the family Alcidae in the order Charadriiformes. The alcid family includes the Uria, murres, guillemots, Aethia, auklets, puffins, and Brachyramphus, murrelets. The family contains 25 extant or recently extinct speci ...

family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

. It is the only puffin native to the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the ...

; two related species, the tufted puffin and the horned puffin being found in the northeastern Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the cont ...

. The Atlantic puffin breeds in Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

, Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, Britain, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

, Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

, Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the populatio ...

, Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

, and the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

, and as far south as Maine

Maine ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the United States, and the northeasternmost state in the Contiguous United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Provinces and ...

in the west and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

in the east. It is most commonly found in the Westman Islands, Iceland. Although it has a large population and a wide range, the species has declined rapidly, at least in parts of its range, resulting in it being rated as vulnerable by the IUCN

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natural resources. Founded in 1948, IUCN has become the global authority on the status ...

. On land, it has the typical upright stance of an auk. At sea, it swims on the surface and feeds on zooplankton, small fish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

, and crabs, which it catches by diving underwater, using its wings for propulsion.

This puffin has a black crown and back, light grey cheek patches, and a white body and underparts. Its broad, boldly marked red-and-black beak and orange legs contrast with its plumage. It moults while at sea in the winter, and some of the brightly coloured facial characteristics are lost, with colour returning during the spring. The external appearances of the adult male and female are identical, though the male is usually slightly larger. The juvenile has similar plumage, but its cheek patches are dark grey. The juvenile does not have brightly coloured head ornamentation, its bill is narrower and is dark grey with a yellowish-brown tip, and its legs and feet are also dark. Puffins from northern populations are typically larger than in the south and these populations are generally considered a different subspecies.

Spending the autumn and winter in the open ocean of the cold northern seas, the Atlantic puffin returns to coastal areas at the start of the breeding season in late spring. It nests in clifftop colonies, digging a burrow in which a single white egg is laid. Chicks mostly feed on whole fish and grow rapidly. After about 6 weeks, they are fully fledge

Fledging is the stage in a flying animal's life between egg, hatching or birth and becoming capable of flight.

This term is most frequently applied to birds, but is also used for bats. For altricial birds, those that spend more time in vulnera ...

d and make their way at night to the sea. They swim away from the shore and do not return to land for several years.

Colonies are mostly on islands with no terrestrial predators, but adult birds and newly fledged chicks are at risk of attacks from the air by gulls and skuas. Sometimes, a bird such as an Arctic skua or blackback gull can cause a puffin arriving with a beak full of fish to drop all the fish the puffin was holding in its mouth. The puffin's striking appearance, large, colourful bill, waddling gait, and behaviour have given rise to nicknames such as "clown of the sea" or "sea parrot". It is the official bird of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Taxonomy and etymology

The Atlantic puffin is a species of seabird in the order Charadriiformes. It is in the aukfamily

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

, Alcidae, which includes the guillemots, typical auks, murrelets, auklets, puffins, and the razorbill. The rhinoceros auklet (''Cerorhinca monocerata'') and the puffins are closely related, together composing the tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

Fraterculini. The Atlantic puffin is the only species in the genus '' Fratercula'' to occur in the Atlantic Ocean. Two other species are known from the northeast Pacific, the tufted puffin (''Fratercula cirrhata'') and the horned puffin (''Fratercula corniculata''), the latter being the closest relative of the Atlantic puffin.

The generic name ''Fratercula'' comes from the Medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Church, Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. It was also the administrative language in the former Western Roman Empire, Roman Provinces of Mauretania, Numidi ...

''fratercula'', friar, a reference to their black and white plumage, which resembles monastic

Monasticism (; ), also called monachism or monkhood, is a religious way of life in which one renounces worldly pursuits to devote oneself fully to spiritual activities. Monastic life plays an important role in many Christian churches, especially ...

robes. The specific name ''arctica'' refers to the northerly distribution of the bird, being derived from the Greek ἄρκτος (''arktos''), the bear

Bears are carnivoran mammals of the family (biology), family Ursidae (). They are classified as caniforms, or doglike carnivorans. Although only eight species of bears are extant, they are widespread, appearing in a wide variety of habitats ...

, referring to the northerly constellation

A constellation is an area on the celestial sphere in which a group of visible stars forms Asterism (astronomy), a perceived pattern or outline, typically representing an animal, mythological subject, or inanimate object.

The first constellati ...

, the Ursa Major (Great Bear). The vernacular name "puffin" – puffed in the sense of swollen – was originally applied to the fatty, salted meat of young birds of the unrelated species Manx shearwater (''Puffinus puffinus''), which in 1652 was known as the "Manks puffin". It is an Anglo-Norman word (Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman Conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English pe ...

''pophyn'' or ''poffin'') used for the cured carcasses. The Atlantic puffin acquired the name at a much later stage, possibly because of its similar nesting habits,Lee, D. S. & Haney, J. C. (1996) "Manx Shearwater (''Puffinus puffinus'')", in: ''The Birds of North America'', No. 257, (Poole, A. & Gill, F. eds). Philadelphia: The Academy of Natural Sciences, and The American Ornithologists' Union, Washington, DC and it was formally applied to ''Fratercula arctica'' by Pennant in 1768. While the species is also known as the common puffin, "Atlantic puffin" is the English name recommended by the International Ornithological Congress.

The three subspecies generally recognized are:

* ''F. a. arctica''

* ''F. a. grabae''

* ''F. a. naumanni''

The only morphological difference between the three is their size. Body length, wing length, and size of beak all increase at higher latitudes. For example, a puffin from northern Iceland (subspecies ''F. a. naumanii'') weighs about and has a wing length of , while one from the Faroes

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

(subspecies ''F. a. grabae'') weighs and has a wing length of . Individuals from southern Iceland (subspecies ''F. a. arctica'') are intermediate between the other two in size. Ernst Mayr has argued that the differences in size are clinal and are typical of variations found in the peripheral population and that no subspecies should be recognised.

Description

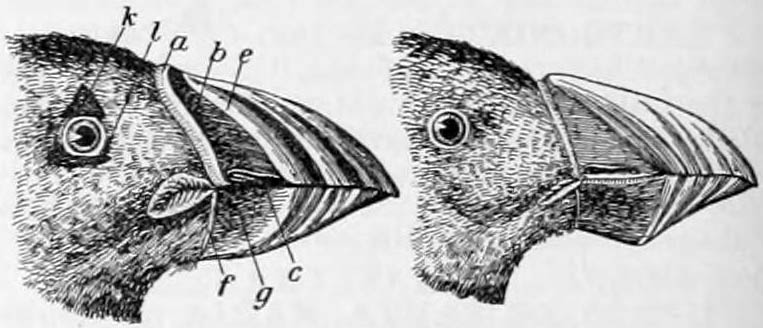

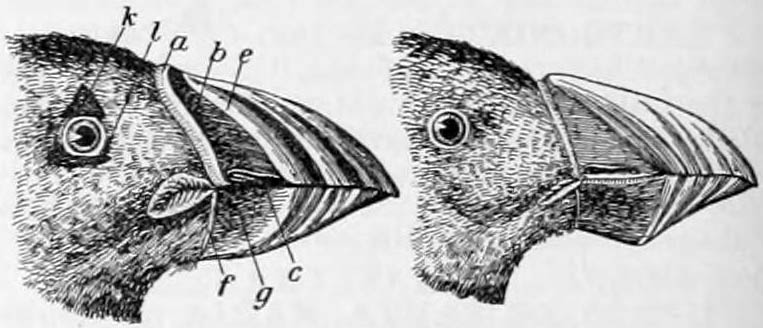

The Atlantic puffin is sturdily built with a thick-set neck and short wings and tail. It is in length from the tip of its stout bill to its blunt-ended tail. Its wingspan is and on land it stands about high. The male is generally slightly larger than the female, but they are coloured alike. The forehead, crown, and nape are glossy black, as are the back, wings, and tail. A broad, black collar extends around the neck and throat. On each side of the head is a large, lozenge-shaped area of very pale grey. These face patches taper to a point and nearly meet at the back of the neck. The shape of the head creates a crease extending from the eye to the hindmost point of each patch, giving the appearance of a grey streak. The eyes look almost triangular because of a small, peaked area of horny blue-grey skin above them and a rectangular patch below. The irises are brown or very dark blue, and each has a red orbital ring. The underparts of the bird, the breast, belly, and under tail coverts, are white. By the end of the breeding season, the black plumage may have lost its shine or even taken on a slightly brown tinge. The legs are short and set well back on the body, giving the bird its upright stance when on land. Both legs and large webbed feet are bright orange, contrasting with the sharp, black claws. The beak is very distinctive. From the side, the beak is broad and triangular, but viewed from above, it is narrow. The half near the tip is orange-red and the half near the head is slate grey. A yellow, chevron-shaped ridge separates the two parts, with a yellow, fleshy strip at the base of the bill. At the joint of the two mandibles is a yellow, wrinkled rosette. The exact proportions of the beak vary with the age of the bird. In an immature individual, the beak has reached its full length, but it is not as broad as that of an adult. With time the bill deepens, the upper edge curves, and a kink develops at its base. As the bird ages, one or more grooves may form on the red portion. The bird has a powerful bite. The characteristic bright orange bill plates and other facial characteristics develop in the spring. At the close of the breeding season, these special coatings and appendages are shed in a partial moult. This makes the beak appear less broad, the tip less bright, and the base darker grey. The eye ornaments are shed and the eyes appear round. At the same time, the feathers of the head and neck are replaced and the face becomes darker. This winter plumage is seldom seen by humans because when they have left their chicks, the birds head out to sea and do not return to land until the next breeding season. The juvenile bird is similar to the adult in plumage, but altogether duller with a much darker grey face and yellowish-brown beak tip and legs. After fledging, it makes its way to the water and heads out to sea, and does not return to land for several years. In the interim, each year, it will have a broader bill, paler face patches, and brighter legs and beaks.

The Atlantic puffin has a direct flight, typically above the sea surface and higher over the water than most other auks. It mostly moves by paddling along efficiently with its webbed feet and seldom takes to the air. It is typically silent at sea, except for the soft purring sounds it sometimes makes in flight. At the breeding colony, it is quiet above ground, but in its burrow makes a growling sound somewhat resembling a chainsaw being revved up.

The characteristic bright orange bill plates and other facial characteristics develop in the spring. At the close of the breeding season, these special coatings and appendages are shed in a partial moult. This makes the beak appear less broad, the tip less bright, and the base darker grey. The eye ornaments are shed and the eyes appear round. At the same time, the feathers of the head and neck are replaced and the face becomes darker. This winter plumage is seldom seen by humans because when they have left their chicks, the birds head out to sea and do not return to land until the next breeding season. The juvenile bird is similar to the adult in plumage, but altogether duller with a much darker grey face and yellowish-brown beak tip and legs. After fledging, it makes its way to the water and heads out to sea, and does not return to land for several years. In the interim, each year, it will have a broader bill, paler face patches, and brighter legs and beaks.

The Atlantic puffin has a direct flight, typically above the sea surface and higher over the water than most other auks. It mostly moves by paddling along efficiently with its webbed feet and seldom takes to the air. It is typically silent at sea, except for the soft purring sounds it sometimes makes in flight. At the breeding colony, it is quiet above ground, but in its burrow makes a growling sound somewhat resembling a chainsaw being revved up.

Distribution

The Atlantic puffin is a bird of the colder waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. It breeds on the coasts of northwest Europe, the Arctic fringes, and eastern North America. More than 90% of the global population is found in Europe (4,770,000–5,780,000 pairs, equalling 9,550,000–11,600,000 adults) and colonies inIceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

alone are home to 60% of the world's Atlantic puffins. The largest colony in the western Atlantic (estimated at more than 260,000 pairs) can be found at the Witless Bay Ecological Reserve, south of St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador. Other major breeding locations include the north and west coasts of Norway, the Faroe Islands, Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

and Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

, the west coast of Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

, and the coasts of Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

. Smaller-sized colonies are also found elsewhere in the British Isles, the Murmansk area of Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

, Novaya Zemlya, Spitzbergen, Labrador, Nova Scotia, and Maine. Islands seem particularly attractive to the birds for breeding as compared to mainland sites, likely to avoid predators.

While at sea, the bird ranges widely across the North Atlantic Ocean, including the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

, and may enter the Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the northernmost of the five major circle of latitude, circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth at about 66° 34' N. Its southern counterpart is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circl ...

. In the summer, its southern limit stretches from northern France to Maine; in the winter, the bird may range as far south as the Mediterranean Sea and North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

. These oceanic waters have such a vast extent of that each bird has more than 1 km2 of range at its disposal, so is seldom seen out at sea. In Maine, light-level geolocators have been attached to the legs of puffins, which store information on their whereabouts. The birds need to be recaptured to access the information, a difficult task. One bird was found to have covered of the ocean in 8 months, traveling northwards to the northern Labrador Sea

The Labrador Sea (; ) is an arm of the North Atlantic Ocean between the Labrador Peninsula and Greenland. The sea is flanked by continental shelf, continental shelves to the southwest, northwest, and northeast. It connects to the north with Baffi ...

then southeastward to the mid-Atlantic before returning to land.

In a long-living bird with a small clutch size, such as the Atlantic puffin, the survival rate of adults is an important factor influencing the success of the species. Only 5% of the ringed puffins that failed to reappear at the colony did so during the breeding season. The rest were lost some time between departing from land in the summer and reappearing the following spring. The birds spend the winter widely spread out in the open ocean, though a tendency exists for individuals from different colonies to overwinter in different areas. Little is known of their behaviour and diet at sea, but no correlation was found between environmental factors, such as temperature variations, and their mortality rate. A combination of the availability of food in winter and summer probably influences the survival of the birds, since individuals starting the winter in poor condition are less likely to survive than those in good condition.

Behaviour

Like many seabirds, the Atlantic puffin spends most of the year far from land in the open ocean and visits coastal areas only to breed. It is a sociable bird, and it usually breeds in large colonies.At sea

Atlantic puffins lead solitary existences when out at sea, and this part of their lives has been little studied, as the task of finding even one bird on the vast ocean is formidable. When at sea, they bob about like a cork, propelling themselves through the water with powerful thrusts of their feet and keeping turned into the wind, even when resting and apparently asleep. They spend much time each day preening to keep their plumage in order and spread oil from their preen glands. Their downy under plumage remains dry and provides thermal insulation. In common with other seabirds, their upper surface is black and underside white. This providescamouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

, with aerial predators unable to locate the birds against the dark, watery background, and underwater attackers fail to notice them as they blend in with the bright sky above the waves.

When it takes off, the Atlantic puffin patters across the surface of the water while vigorously flapping its wings, before launching itself into the air. The size of the wing has adapted to its dual use, both above and below the water, and its surface area is small relative to the bird's weight. To maintain flight, the wings must beat very rapidly at a rate of several times each second. The bird's flight is direct and low over the surface of the water, and it can travel at . Landing is awkward; it either crashes into a wave crest or in calmer water, does a belly flop. While at sea, the Atlantic puffin has its annual moult. Land birds mostly lose their primaries one pair at a time to enable them still to be able to fly, but the puffin sheds all its primaries at one time and dispenses with flight entirely for a month or two. The moult usually takes place between January and March, but young birds may lose their feathers a little later in the year.

Food and feeding

The Atlantic puffin diet consists almost entirely of fish, though examination of its stomach contents shows that it occasionally eats shrimp, other crustaceans,mollusc

Mollusca is a phylum of protostome, protostomic invertebrate animals, whose members are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 76,000 extant taxon, extant species of molluscs are recognized, making it the second-largest animal phylum ...

s, and polychaete worms, especially in more coastal waters. When fishing, it swims underwater using its semi-extended wings as paddles to "fly" through the water and its feet as a rudder. It swims fast and can reach considerable depths and stay submerged for up to a minute. It can eat shallow-bodied fish as long as , but its prey is commonly smaller fish, around long. An adult bird needs to eat an estimated 40 of these per day – sand eels, herring, capelin, and sprats being the most often consumed.

It fishes by sight and can swallow small fish while submerged, but larger specimens are brought to the surface. It can catch several small fish in one dive, holding the first ones in place in its beak with its muscular, grooved tongue while it catches others. The two mandibles are hinged in such a way that they can be held parallel to hold a row of fish in place and these are also retained by inward-facing serrations on the edges of the beak. It copes with the excess salt that it swallows partly through its kidney

In humans, the kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped blood-filtering organ (anatomy), organs that are a multilobar, multipapillary form of mammalian kidneys, usually without signs of external lobulation. They are located on the left and rig ...

s and partly by excretion

Excretion is elimination of metabolic waste, which is an essential process in all organisms. In vertebrates, this is primarily carried out by the lungs, Kidney (vertebrates), kidneys, and skin. This is in contrast with secretion, where the substa ...

through specialised salt glands in its nostrils.

On land

In the spring, mature birds return to land, usually to the colony where they were hatched. Birds that were removed as chicks and released elsewhere were found to show fidelity to their point of liberation. They congregate for a few days on the sea in small groups offshore before returning to the cliff-top nesting sites. Each large puffin colony is divided into subcolonies by physical boundaries such as stands of bracken or gorse. Early arrivals take control of the best locations, the most desirable nesting sites being the densely packed burrows on grassy slopes just above the cliff edge where take-off is most easily accomplished. The birds are usually monogamous, but this is the result of their fidelity to their nesting sites rather than to their mates, and they often return to the same burrows year after year. Later arrivals at the colony may find that all the best nesting sites have already been taken, so are pushed towards the periphery, where they are in greater danger of predation. Younger birds may come ashore a month or more after the mature birds and find no remaining nesting sites. They do not breed until the following year, although if the ground cover surrounding the colony is cut back before these subadults arrive, the number of successfully nesting pairs may be increased. Atlantic puffins are cautious when approaching the colony, and no bird likes to land in a location where other puffins are not already present. They make several circuits of the colony before alighting. On the ground, they spend much time preening, spreading oil from their preen gland, and setting each feather in its correct position with beak or claw. They also spend time standing by their burrow entrances and interacting with passing birds. Dominance is shown by an upright stance, with fluffed chest feathers and a cocked tail, an exaggerated slow walk, head jerking, and gaping. Submissive birds lower their heads and hold their bodies horizontally and scurry past dominant individuals. Birds normally signal their intention to take off by briefly lowering their bodies before running down the slope to gain momentum. If a bird is startled and takes off unexpectedly, panic can spread through the colony with all the birds launching themselves into the air and wheeling around in a great circle. The colony is at its most active in the evening, with birds standing outside their burrows, resting on the turf, or strolling around. Then, the slopes empty for the night as the birds fly out to sea to roost, often choosing to do so at fishing grounds ready for early-morning provisioning. The puffins are energetic burrow engineers and repairers, so the grassy slopes may be undermined by a network of tunnels. This causes the turf to dry out in summer, vegetation to die, and dry soil to be whirled away by the wind. Burrows sometimes collapse, and humans may cause this to happen by walking incautiously across nesting slopes. A colony on Grassholm was lost through erosion when so little soil was left that burrows could not be made. New colonies are very unlikely to start up spontaneously because this gregarious bird only nests where others are already present. Nevertheless, the Audubon Society had success on Eastern Egg Rock Island in Maine, where, after a gap of 90 years, puffins were reintroduced and started breeding again. By 2011, over 120 pairs were nested on the small islet. On theIsle of May

An isle is an island, land surrounded by water. The term is very common in British English. However, there is no clear agreement on what makes an island an isle or its difference, so they are considered synonyms.

Isle may refer to:

Geography

* Is ...

on the other side of the Atlantic, only five pairs of puffins were breeding in 1958, while 20 years later, 10,000 pairs were present.

Reproduction

Having spent the winter alone on the ocean, whether the Atlantic puffin meets its previous partner offshore or whether they encounter each other when they return to their nest of the previous year is unclear. On land, they soon set about improving and clearing out the burrow. Often, one stands outside the entrance while the other excavates, kicking out quantities of soil and grit that showers the partner standing outside. Some birds collect stems and fragments of dry grasses as nesting materials, but others do not bother. Sometimes, a beakful of materials is taken underground, only to be brought out again and discarded. Apart from nest-building, the other way in which the birds restore their bond is by billing. This is a practice in which the pair approaches each other, each wagging their heads from side to side, and then rattling their beaks together. This seems to be an important element of their courtship behaviour because it happens repeatedly, and the birds continue to the bill, to a lesser extent, throughout the breeding season. Atlantic puffins are sexually mature at 4–5 years old. They are colonial nesters, excavating burrows on grassy clifftops or reusing existing holes, and on occasion may nest in crevices and among rocks and scree, in competition with other birds and animals for burrows. They can excavate their own hole or move into a pre-existing system dug by a rabbit, and have been known to peck and drive off the original occupant. Manx shearwaters also nest underground and often live in their own burrows alongside puffins, and their burrowing activities may break through into the puffin's living quarters, resulting in the loss of the egg. They are monogamous (mate for life) and give biparental care to their young. The male spends more time guarding and maintaining the nest, while the female is more involved in incubation and feeding the chick. Egg-laying starts in April in more southerly colonies but seldom occurs before June in Greenland. The female lays a single white egg each year, but if this is lost early in the breeding season, another might be produced. Synchronous laying of eggs is found in Atlantic puffins in adjacent burrows. The egg is large compared to the size of the bird, averaging long by wide and weighing about . The white shell is usually devoid of markings, but soon becomes covered with mud. The incubation responsibilities are shared by both parents. They each have two feather-free brood patches on their undersides, where an enhanced blood supply provides heat for the egg. The parent on incubation duty in the dark nest chamber spends much of its time asleep with its head tucked under its wing, occasionally emerging from the tunnel to flap dust out of its feathers or take a short flight down to the sea. The total incubation time is around 39–45 days. From above ground level, the first evidence that hatching has taken place is the arrival of an adult with a beak-load of fish. For the first few days, the chick may be fed with this beak-to-beak, but later the fish are simply dropped on the floor of the nest beside the chick, which swallows them whole. The chick is covered in fluffy black down, its eyes are open, and it can stand as soon as it is hatched. Initially weighing about , it grows at the rate of per day. Initially, one or the other parent broods it, but as its appetite increases, it is left alone for longer periods. Observations of a nest chamber have been made from an underground hide with a peephole. The chick sleeps much of the time between its parents' visits and also involves itself in bouts of exercise. It rearranges its nesting material, picks up and drops small stones, flaps its immature wings, pulls at protruding root ends, and pushes and strains against the unyielding wall of the burrow. It makes its way towards the entrance or along a side tunnel to defecate. The growing chick seems to anticipate the arrival of an adult, advancing along the burrow just before it arrives, but not emerging into the open air. It retreats to the nest chamber as the adult bird brings in its load of fish. Hunting areas are often located or more offshore from the nest sites, although when feeding their young, the birds venture out only half that distance. Adults bringing fish to their chicks tend to arrive in groups. This is thought to benefit the bird by reducing kleptoparasitism by the Arctic skua, which harasses puffins until they drop their fish loads. Predation by the great skua (''Catharacta skua'') is also reduced by several birds arriving simultaneously. In the Shetland Islands, sand eels (''Ammodytes marinus'') normally form at least 90% of the food fed to chicks. In years when the availability of sand eels was low, breeding success rates fell, with many chicks starving to death. InNorway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

, the herring (''Clupea harengus'') is the mainstay of the diet. When herring numbers dwindled, so did puffin numbers. In Labrador, the puffins seemed more flexible and when the staple forage fish capelin (''Mallotus villosus'') declined in availability, they were able to adapt and feed the chicks on other prey species.

The chicks take from 34 to 50 days to fledge

Fledging is the stage in a flying animal's life between egg, hatching or birth and becoming capable of flight.

This term is most frequently applied to birds, but is also used for bats. For altricial birds, those that spend more time in vulnera ...

, the period depending on the abundance of their food supply. In years of fish shortage, the whole colony may experience a longer fledgling period, but the normal range is 38 to 44 days, by which time chicks have reached about 75% of their mature body weight. The chick may come to the burrow entrance to defecate, but does not usually emerge into the open and seems to have an aversion to light until it is nearly fully fledged. Although the supply of fish by the adults reduces over the last few days spent in the nest, the chick is not abandoned as happens in the Manx shearwater. On occasions, an adult has been observed provisioning a nest even after the chick has departed. During the last few days underground, the chick sheds its down and the juvenile plumage is revealed. Its relatively small beak and its legs and feet are a dark colour, and it lacks the white facial patches of the adult. The chick finally leaves its nest at night, when the risk of predation is at its lowest. When the moment arrives, it emerges from the burrow, usually for the first time, and walks, runs, and flaps its way to the sea. It cannot fly properly yet, so descending a cliff is perilous; when it reaches the water, it paddles out to sea, and maybe away from the shore by daybreak. It does not congregate with others of its kind and does not return to land for 2–3 years.

Predators and parasites

Atlantic puffins are probably safer when out at sea, where the dangers are more often from below the water rather than above; puffins can sometimes be seen putting their heads underwater to peer around for predators. Seals have been known to kill puffins, and large fish may also do so. Most puffin colonies are on small islands, and this is no coincidence, as it avoids predation by ground-basedmammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s such as foxes, rats, stoats, weasels, cats, and dogs. When they come ashore, the birds are still at risk and the main threats come from the sky.

Aerial predators of the Atlantic puffin include the great black-backed gull

The great black-backed gull (''Larus marinus'') is the largest member of the gull family. It is a very aggressive hunter, pirate, and scavenger which breeds on the coasts and islands of the North Atlantic in northern Europe and northeastern Nort ...

(''Larus marinus''), the great skua (''Stercorarius skua''), and similar-sized species, which can catch a bird in flight, or attack one that is unable to escape fast enough on the ground. On detecting danger, puffins take off and fly down to the safety of the sea or retreat into their burrows, but if caught, they defend themselves vigorously with beaks and sharp claws. When the puffins are wheeling around beside the cliffs, a predator concentrating on a single bird becomes very difficult, while any individual isolated on the ground is at greater risk. Smaller gull species such as the herring gull (''L. argentatus'') and the lesser black-backed gull are hardly able to bring down a healthy adult puffin. They stride through the colony taking any eggs that have rolled towards burrow entrances or recently hatched chicks that have ventured too far toward the daylight. They also steal fish from puffins returning to feed their young. Where it nests on the tundra

In physical geography, a tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. There are three regions and associated types of tundra: #Arctic, Arctic, Alpine tundra, Alpine, and #Antarctic ...

in the far north, the Arctic skua (''Stercorarius parasiticus'') is a terrestrial predator, but at lower latitudes, it is a specialised kleptoparasite, concentrating on auks and other seabirds. It harasses puffins while they are airborne, forcing them to drop their catch, which it then snatches up.

Both the guillemot tick '' Ixodes uriae'' and the flea

Flea, the common name for the order (biology), order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by hematophagy, ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult f ...

''Ornithopsylla laetitiae'' (probably originally a rabbit flea) have been recorded from the nests of puffins. Other fleas found on the birds include '' Ceratophyllus borealis'', '' Ceratophyllus gallinae'', ''Ceratophyllus garei'', ''Ceratophyllus vagabunda'', and the common rabbit flea ''Spilopsyllus cuniculi

''Spilopsyllus cuniculi'', the rabbit flea, is a species of flea in the Family (biology), family Pulicidae. It is an external Parasitism, parasite of rabbits and hares and is occasionally found on cats and dogs and also certain seabirds that nest ...

''.

Relationship with humans

Status and conservation

The Atlantic puffin has an extensive range that covers over and Europe, which holds more than 90% of the global population, is home to 4,770,000–5,780,000 pairs (equalling 9,550,000–11,600,000 adults). In 2015, the International Union for Conservation of Nature upgraded its status from "least concern" to "vulnerable". This was caused by a review that revealed a rapid and ongoing population decline in its European range. Trends elsewhere are unknown, although, in 2018, the total global population was estimated at 12–14 million adult individuals. Some of the causes of population decline may be increased predation by gulls and skuas, the introduction of rats, cats, dogs, and foxes onto some islands used for nesting, contamination by toxic residues, drowning in fishing nets, declining food supplies, andclimate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

. On the island of Lundy, the number of puffins decreased from 3,500 pairs in 1939 to 10 pairs in 2000. This was mainly due to the rats that had proliferated on the island and were eating eggs and young chicks. Following the elimination of the rats, populations were expected to recover, and in 2005, a juvenile was seen, believed to be the first chick raised on the island for 30 years. In 2018, BirdLife International reported that the Atlantic puffin was threatened with extinction.

Puffin numbers increased considerably in the late 20th century in the North Sea, including on the Isle of May and the Farne Islands, where numbers increased by about 10% per year. In the 2013 breeding season, nearly 40,000 pairs were recorded on the Farne Islands, a slight increase on the 2008 census and on the previous year's poor season, when some of the burrows flooded. This number is dwarfed by the Icelandic colonies with five million pairs breeding, the Atlantic puffin being the most populous bird on the island. In the Westman Islands, where about half Iceland's puffins breed, the birds were almost driven to extinction by overharvesting around 1900 and a 30-year ban on hunting was put in place. When stocks recovered, a different method of harvesting was used and now hunting is maintained at a sustainable level. Nevertheless, a further hunting ban covering the whole of Iceland was called for in 2011, although the puffin's lack of recent breeding success was being blamed on a diminution in food supply rather than overharvesting. Since 2000, a sharp population decline has been seen in Iceland, Norway, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland. A similar trend has been seen in the United Kingdom, where an increase in 1969–2000 appears to have been reversed. For example, the Fair Isle colony was estimated at 20,200 individuals in 1986, but it had been almost halved by 2012. Based on current trends, the European population will decline an estimated 50–79% between 2000 and 2065.

However, there are more than 43,000 puffins on the island of Skomer, off the coast of Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire ( ; ) is a Principal areas of Wales, county in the South West Wales, south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and otherwise by the sea. Haverfordwest is the largest town and ...

in west Wales, making it one of the most important puffin colonies in Britain; their numbers have been increasing year on year since the elimination of predators on the island.

SOS Puffin is a conservation project at the Scottish Seabird Centre at North Berwick to save the puffins on islands in the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is a firth in Scotland, an inlet of the North Sea that separates Fife to its north and Lothian to its south. Further inland, it becomes the estuary of the River Forth and several other rivers.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate ...

. Puffin numbers on the island of Craigleith, once one of the largest colonies in Scotland with 28,000 pairs, have declined dramatically to just a few thousand due to the invasion of a large introduced plant, the tree mallow (''Lavatera arborea''). This has spread across the island in dense thickets and prevents the puffins from finding suitable sites for burrowing and breeding. The project has the support of over 700 volunteers and progress has been made in cutting back the plants, with puffins returning in greater numbers to breed. Another conservation measure undertaken by the centre is to encourage motorists to check under their cars in late summer before driving off, as young puffins, disoriented by the street lights, may land in the town and take shelter underneath the vehicles.

Project Puffin is an effort initiated in 1973 by Stephen W. Kress of the National Audubon Society to restore Atlantic puffins to nesting islands in the Gulf of Maine. Eastern Egg Rock Island in Muscongus Bay, about from Pemaquid Point, had been occupied by nesting puffins until 1885, when the birds disappeared because of overhunting. Counting on the fact young puffins usually return to breed on the same island where they fledged, a team of biologists and volunteers translocated 10– to 14-day-old nestlings from Great Island in Newfoundland to Eastern Egg Rock. The young were placed into artificial sod burrows and fed with vitamin-fortified fish daily for about one month. Such yearly translocations took place until 1986, with 954 young puffins being moved in total. Each year before fledging, the young were individually tagged. The first adults returned to the island by 1977. Puffin decoys had been installed on the island to fool the puffins into thinking they were part of an established colony. This did not catch on at first, but in 1981, four pairs nested on the island. In 2014, 148 nesting pairs were counted on the island. In addition to demonstrating the feasibility of re-establishing a seabird colony, the project showed the usefulness of using decoys and eventually call recordings and mirrors, to facilitate such re-establishment.

Pollution

marine pollution

Marine pollution occurs when substances used or spread by humans, such as industrial waste, industrial, agricultural pollution, agricultural, and municipal solid waste, residential waste; particle (ecology), particles; noise; excess carbon dioxi ...

by lipophilic

Lipophilicity (from Greek language, Greek λίπος "fat" and :wikt:φίλος, φίλος "friendly") is the ability of a chemical compound to dissolve in fats, oils, lipids, and non-polar solvents such as hexane or toluene. Such compounds are c ...

substances, as well as metals. In fact, these surveys can be used to provide evidence of the adverse effects of a particular pollutant, using fingerprinting techniques to provide evidence suitable for the prosecution of offenders.

Climate change

Climate change may well affect populations of seabirds in the northern Atlantic. The most important demographic may be an increase in the sea surface temperature, which may have benefits for some northerly Atlantic puffin colonies. Breeding success depends on ample supplies of food at the time of maximum demand, as the chick grows. In northern Norway, the main food item fed to the chick is the young herring. The success of the newly hatched fish larvae during the previous year was governed by the water temperature, which controlled plankton abundance, and this, in turn, influenced the growth and survival of the first-year herring. The breeding success of Atlantic puffin colonies has been found to correlate in this way with the water surface temperatures of the previous year. In Maine, on the other side of the Atlantic, shifting fish populations due to changes in sea temperature are being blamed for the lack of availability of the herring, which is the staple diet of the puffins in the area. Some adult birds have become emaciated and died. Others have been provisioning the nest with butterfish (''Peprilus triacanthus''), but these are often too large and deep-bodied for the chick to swallow, causing it to die from starvation. Maine is on the southerly edge of the bird's breeding range, and with changing weather patterns, this may be set to contract northwards.Tourism

Breeding colonies of Atlantic puffins provide an interesting spectacle for bird watchers and tourists. For example, 4000 puffins nest each year on islands off the coast of Maine, and visitors can view them from tour boats that operate during the summers. The Project Puffin Visitor Center in Rockland provides information on the birds and their lives, and on the other conservation projects being undertaken by the National Audubon Society, which runs the center. Views of the colony on Seal Island National Wildlife Refuge can be viewed via live cams during the breeding season. Similar tours operate in Iceland, theHebrides

The Hebrides ( ; , ; ) are the largest archipelago in the United Kingdom, off the west coast of the Scotland, Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Ou ...

, and Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

.

Hunting

Historically, Atlantic puffins were caught and eaten fresh, salted in brine, or smoked and dried. Their feathers were used in bedding and their eggs were eaten, but not to the same extent as those of some other seabirds, being more difficult to extract from the nest. In most countries, Atlantic puffins are now protected by legislation, and in the countries where hunting is still permitted, strict laws preventoverexploitation

Overexploitation, also called overharvesting or ecological overshoot, refers to harvesting a renewable resource to the point of diminishing returns. Continued overexploitation can lead to the destruction of the resource, as it will be unable to ...

. Although calls have been made for an outright ban on hunting puffins in Iceland because of concern over the dwindling number of birds successfully raising chicks, they are still caught and eaten there and on the Faroe Islands.

Traditional means of capture varied across the birds' range, and nets and rods were used in various ingenious ways. In the Faroe Islands, the method of choice was ''fleyg'', with the use of a ''fleygingarstong'', a 3.6-m-long pole with a small net at the end suspended between two rods, somewhat like a very long lacrosse stick. A few dead puffins were strewn around to entice incoming birds to land, and the net was flicked upwards to scoop a bird from the air as it slowed before alighting. Hunters often positioned themselves on cliff tops in stone seats built in small depressions to conceal themselves from puffins flying overhead. Most of the birds caught were subadults, and a skilled hunter could gather 200–300 in a day. Another method of capture, used in St Kilda, involved the use of a flexible pole with a noose on the end. This was pushed along the ground towards the intended target, which advanced to inspect the noose as its curiosity overcame its caution. A flick of the wrist would flip the noose over the victim's head and it was promptly killed before its struggles could alarm other birds nearby.

In culture

The Atlantic puffin is the official bird symbol of the province of

The Atlantic puffin is the official bird symbol of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the populatio ...

, Canada. In August 2007, the Atlantic puffin was unsuccessfully proposed as the official symbol of the Liberal Party of Canada

The Liberal Party of Canada (LPC; , ) is a federal political party in Canada. The party espouses the principles of liberalism,McCall, Christina; Stephen Clarkson"Liberal Party". ''The Canadian Encyclopedia''. and generally sits at the Centrism, ...

by its deputy leader Michael Ignatieff, after he observed a colony of these birds and became fascinated by their behaviour. Værøy Municipality in Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

has an Atlantic puffin as its coat of arms

A coat of arms is a heraldry, heraldic communication design, visual design on an escutcheon (heraldry), escutcheon (i.e., shield), surcoat, or tabard (the last two being outer garments), originating in Europe. The coat of arms on an escutcheon f ...

. Puffins have been given several informal names including "clowns of the sea" and "sea parrots", and juvenile puffins may be called "pufflings".

Several islands have been named after the bird. The island of Lundy in the United Kingdom is reputed to derive its name from the Norse ''lund-ey'' or "puffin island". An alternative explanation has been suggested connected with another meaning of the word "lund" referring to a copse or wooded area. The Vikings

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

might have found the island a useful refuge and restocking point after their depredations on the mainland. The island issued its own coin

A coin is a small object, usually round and flat, used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in order to facilitate trade. They are most often issued by ...

s, and in 1929, its own stamps with denominations in "puffins". Other countries and dependencies that have depicted Atlantic puffins on their stamps include Alderney

Alderney ( ; ; ) is the northernmost of the inhabited Channel Islands. It is part of the Bailiwick of Guernsey, a British Crown Dependencies, Crown dependency. It is long and wide.

The island's area is , making it the third-largest isla ...

, Canada, the Faroe Islands, France, Gibraltar

Gibraltar ( , ) is a British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory and British overseas cities, city located at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, on the Bay of Gibraltar, near the exit of the Mediterranean Sea into the A ...

, Guernsey

Guernsey ( ; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; ) is the second-largest island in the Channel Islands, located west of the Cotentin Peninsula, Normandy. It is the largest island in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, which includes five other inhabited isl ...

, Iceland, Ireland, the Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

, Jersey

Jersey ( ; ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey, is an autonomous and self-governing island territory of the British Islands. Although as a British Crown Dependency it is not a sovereign state, it has its own distinguishing civil and gov ...

, Norway, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

, Russia, Slovenia

Slovenia, officially the Republic of Slovenia, is a country in Central Europe. It borders Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and a short (46.6 km) coastline within the Adriati ...

, St Pierre et Miquelon, and the United Kingdom.

The publisher of paperback

A paperback (softcover, softback) book is one with a thick paper or paperboard cover, also known as wrappers, and often held together with adhesive, glue rather than stitch (textile arts), stitches or Staple (fastener), staples. In contrast, ...

s, Penguin Books

Penguin Books Limited is a Germany, German-owned English publishing, publishing house. It was co-founded in 1935 by Allen Lane with his brothers Richard and John, as a line of the publishers the Bodley Head, only becoming a separate company the ...

, introduced a range of books for children under the Puffin Books

Puffin Books is a longstanding children's imprint of the British publishers Penguin Books. Since the 1960s, it has been among the largest publishers of children's books in the UK and much of the English-speaking world. The imprint now belongs to ...

brand in 1939. At first, these were nonfiction titles, but these were soon followed by a fiction list of well-known authors. The demand was so great that Puffin Book Clubs were introduced in schools to encourage reading, and a children's magazine called ''Puffin Post'' was established.

A tradition exists on the Icelandic island of Heimaey for the children to rescue young puffins, a fact recorded in Bruce McMillan's photo-illustrated children's book '' Nights of the Pufflings'' (1995). The fledglings emerge from the nest and try to make their way to the sea, but sometimes get confused, perhaps by the street lighting, ending up landing in the village. The children collect them and liberate them to the safety of the sea.

Due to being a protected species on Skellig Michael, the production team for the Star Wars sequel trilogy resorted to digitally dressing the puffins (and practically and digitally recreating them for other scenes), resulting in the creation of porgs.

See also

* * * * *References

External links

* * {{Authority control Fratercula Birds of the Arctic Birds of Europe Birds of Iceland Birds of Scandinavia Native birds of Eastern Canada Provincial symbols of Newfoundland and Labrador Birds described in 1758 Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus Articles containing video clips