Astraeus Hygrometricus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Astraeus hygrometricus'', commonly known as the hygroscopic earthstar, the barometer earthstar, or the false earthstar, is a species of

Young specimens of ''A. hygrometricus'' have roughly spherical

Young specimens of ''A. hygrometricus'' have roughly spherical  The

The

Although ''A. hygrometricus'' bears a superficial resemblance to members of the "true earthstars" ''Geastrum'', it may be readily differentiated from most by the hygroscopic nature of its rays. Hygroscopic earthstars include '' G. arenarium'', '' G. corollinum'', '' G. floriforme'', '' G. recolligens'', and '' G. kotlabae''. Unlike ''Geastrum'', the young fruit bodies of ''A. hygrometricus'' do not have a columella (sterile tissue in the gleba, at the base of the spore sac). ''Geastrum'' tends to have its spore sac opening surrounded by a

Although ''A. hygrometricus'' bears a superficial resemblance to members of the "true earthstars" ''Geastrum'', it may be readily differentiated from most by the hygroscopic nature of its rays. Hygroscopic earthstars include '' G. arenarium'', '' G. corollinum'', '' G. floriforme'', '' G. recolligens'', and '' G. kotlabae''. Unlike ''Geastrum'', the young fruit bodies of ''A. hygrometricus'' do not have a columella (sterile tissue in the gleba, at the base of the spore sac). ''Geastrum'' tends to have its spore sac opening surrounded by a

Mushroom

Mushroom

fungus

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from th ...

in the family Diplocystaceae. Young specimens resemble a puffball

Puffballs are a type of fungus featuring a ball-shaped fruit body that bursts on impact, releasing a cloud of dust-like spores when mature. Puffballs belong to the division Basidiomycota and encompass several genera, including ''Calvatia'', ''Ca ...

when unopened. In maturity, the mushroom displays the characteristic earthstar shape that is a result of the outer layer of fruit body

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants that is formed from the Ovary (plants), ovary after flowering plant, flowering.

Fruits are the means by which flowering plants (also known as angiosperms) disseminate their ...

tissue splitting open in a star-like manner. The false earthstar is an ectomycorrhizal

An ectomycorrhiza (from Greek ἐκτός ', "outside", μύκης ', "fungus", and ῥίζα ', "root"; pl. ectomycorrhizas or ectomycorrhizae, abbreviated EcM) is a form of symbiotic relationship that occurs between a fungal symbiont, or mycobi ...

species that grows in association with various trees, especially in sandy soils. ''A. hygrometricus'' was previously thought to have a cosmopolitan distribution

In biogeography, cosmopolitan distribution is the term for the range of a taxon that extends across all or most of the world in appropriate habitats. Such a taxon, usually a species, is said to exhibit cosmopolitanism or cosmopolitism. The ext ...

, though it is now thought to be restricted to Southern Europe, and ''Astraeus'' are common in temperate and tropical regions. Its common name

In biology, a common name of a taxon or organism (also known as a vernacular name, English name, colloquial name, country name, popular name, or farmer's name) is a name that is based on the normal language of everyday life; and is often contrast ...

s refer to the fact that it is hygroscopic

Hygroscopy is the phenomenon of attracting and holding water molecules via either absorption or adsorption from the surrounding environment, which is usually at normal or room temperature. If water molecules become suspended among the substance ...

(water-absorbing), and can open up its rays to expose the spore sac in response to increased humidity, and close them up again in drier conditions. The rays have an irregularly cracked surface, while the spore case is pale brown and smooth with an irregular slit or tear at the top. The gleba

Gleba (, from Latin ''glaeba, glēba'', "lump") is the fleshy spore-bearing inner mass of certain fungi such as the puffball or stinkhorn.

The gleba is a solid mass of spores, generated within an enclosed area within the sporocarp. The continu ...

is white initially, but turns brown and powdery when the spore

In biology, a spore is a unit of sexual or asexual reproduction that may be adapted for dispersal and for survival, often for extended periods of time, in unfavourable conditions. Spores form part of the life cycles of many plants, algae, f ...

s mature. The spores are reddish-brown, roughly spherical with minute warts, measuring 7.5–11 micrometer Micrometer can mean:

* Micrometer (device), used for accurate measurements by means of a calibrated screw

* American spelling of micrometre

The micrometre ( international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; ...

s in diameter.

Despite a similar overall appearance, ''A. hygrometricus'' is not related to the true earthstars of genus ''Geastrum

''Geastrum'' (orthographical variant ''Geaster'') is a genus of puffball-like mushrooms in the family Geastraceae. Many species are known commonly as earthstars.

The name, which comes from ''geo'' meaning ''earth'' and meaning ''star'', refers ...

'', although historically, they have been taxonomically

In biology, taxonomy () is the scientific study of naming, defining ( circumscribing) and classifying groups of biological organisms based on shared characteristics. Organisms are grouped into taxa (singular: taxon) and these groups are given ...

confused. The species was first described by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon

Christiaan Hendrik Persoon (1 February 1761 – 16 November 1836) was a German mycologist who made additions to Linnaeus' mushroom taxonomy.

Early life

Persoon was born in South Africa at the Cape of Good Hope, the third child of an immig ...

in 1801 as ''Geastrum hygrometricus''. In 1885, Andrew P. Morgan proposed that differences in microscopic characteristics warranted the creation of a new genus ''Astraeus

In Greek mythology, Astraeus () or Astraios (Ancient Greek: Ἀστραῖος means "starry"') was an astrological deity. Some also associate him with the winds, as he is the father of the four Anemoi (wind deities), by his wife, Eos.

Etymolog ...

'' distinct from ''Geastrum''; this opinion was not universally accepted by later authorities. Several Asian populations formerly thought to be ''A. hygrometricus'' were renamed in the 2000s once phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

analyses revealed they were unique ''Astraeus'' species, including '' A. asiaticus'' and '' A. odoratus''. Similarly, in 2013, North American populations were divided into '' A. pteridis'', ''A. morganii'', and ''A. smithii'' on the basis of molecular phylogentics. This research suggests that the type specimen of ''Astraeus hygrometricus'' originates in a population restricted to Europe between Southern France and Turkey, with A. telleriae found nearby in Spain and Greece. Research has revealed the presence of several bioactive chemical compounds in ''Astraeus'' fruit bodies. North American field guides typically rate ''A. hygrometricus'' as inedible.

Taxonomy, naming, and phylogeny

Because this species resembles the earthstar fungi of ''Geastrum'', it was placed in that genus by early authors, starting withChristian Hendrik Persoon

Christiaan Hendrik Persoon (1 February 1761 – 16 November 1836) was a German mycologist who made additions to Linnaeus' mushroom taxonomy.

Early life

Persoon was born in South Africa at the Cape of Good Hope, the third child of an imm ...

in 1801 (as ''Geaster'', an alternate spelling of ''Geastrum''). According to the American botanist Andrew P. Morgan, however, the species differed from those of ''Geastrum'' in not having open chambers in the young gleba

Gleba (, from Latin ''glaeba, glēba'', "lump") is the fleshy spore-bearing inner mass of certain fungi such as the puffball or stinkhorn.

The gleba is a solid mass of spores, generated within an enclosed area within the sporocarp. The continu ...

, having larger and branched capillitium threads, not having a true hymenium

The hymenium is the tissue layer on the hymenophore of a fungal fruiting body where the cells develop into basidia or asci, which produce spores. In some species all of the cells of the hymenium develop into basidia or asci, while in others some ...

, and having larger spores. Accordingly, Morgan set Persoon's ''Geaster hygrometricum'' as the type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen ...

of his new genus ''Astraeus'' in 1889. Despite Morgan's publication, some authorities in the following decades continued to classify the species in ''Geastrum''. The New-Zealand based mycologist Gordon Herriot Cunningham

Gordon Herriot Cunningham, CBE, FRS (27 August 1892 – 18 July 1962) was the first New Zealand-based mycologist and plant pathologist. In 1936 he was appointed the first director of the DSIR Plant Diseases Division. Cunningham established the ...

explicitly transferred the species back to the genus ''Geastrum'' in 1944, explaining: The treatment of this species by certain taxonomists well illustrates the pitfalls that lie in wait for those who worship at the shrine ofCunningham's treatment was not followed by later authorities, who largely considered ''Astraeus'' a distinct genus. According to theontogenic Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to the stu ...classification ... The only feature of those outlined in which the species differs from others of ''Geastrum'' is the somewhat primitive hymenium. In the developing plant the glebal cavities are separated by tramal plates so tenuous as to be overlooked by the uncritical worker. Each cavity is filled with basidia somewhat irregularly arranged in clusters (like those of ''Scleroderma Scleroderma is a group of autoimmune diseases that may result in changes to the skin, blood vessels, muscles, and internal organs. The disease can be either localized to the skin or involve other organs, as well. Symptoms may include areas of ...'') and not in the definite palisade of the species which have been studied. This difference disappears as maturity is reached, when plants resemble closely the fructification of any other member of the genus. The taxonomist is then unable to indicate any point of difference by which "''Astraeus''" may be separated from ''Geastrum'', which indicates that the name should be discarded.

taxonomical

In biology, taxonomy () is the scientific study of naming, defining ( circumscribing) and classifying groups of biological organisms based on shared characteristics. Organisms are grouped into taxa (singular: taxon) and these groups are given ...

authority MycoBank

MycoBank is an online database, documenting new mycological names and combinations, eventually combined with descriptions and illustrations. It is run by the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute in Utrecht.

Each novelty, after being screene ...

, synonyms

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are all ...

of ''Astraeus hygrometricus'' include ''Lycoperdon stellatus'' Scop. (1772); ''Geastrum fibrillosum'' Schwein. (1822); ''Geastrum stellatum'' (Scop.) Wettst. (1885); and ''Astraeus stellatus'' E.Fisch. (1900).

''Astraeus hygrometricus'' has been given a number of colloquial names that allude to its hygroscopic behavior, including the "hygrometer earthstar", the "hygroscopic earthstar", the "barometer earthstar", and the "water-measure earthstar". The resemblance to ''Geastrum'' species (also known as true earthstars) accounts for the common name "false earthstar". The specific name Specific name may refer to:

* in Database management systems, a system-assigned name that is unique within a particular database

In taxonomy, either of these two meanings, each with its own set of rules:

* Specific name (botany), the two-part (bino ...

is derived from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

words () 'wet' and () 'measure'. The German Mycological Society

Deutschsprachige Mykologische Gesellschaft (DMykG) e.V. (German-Speaking Mycological Society) has been acknowledged as a non-profit organisation. The society was founded in 1961 as a platform for all scientists of the German-speaking area who are i ...

selected the species as their "Mushroom of the Year" in 2005.

Studies in the 2000s showed that several species from Asian collection sites labelled under the specific epithet

In taxonomy, binomial nomenclature ("two-term naming system"), also called nomenclature ("two-name naming system") or binary nomenclature, is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, bot ...

''hygrometricus'' were actually considerably variable in a number of macroscopic

The macroscopic scale is the length scale on which objects or phenomena are large enough to be visible with the naked eye, without magnifying optical instruments. It is the opposite of microscopic.

Overview

When applied to physical phenomena an ...

and microscopic

The microscopic scale () is the scale of objects and events smaller than those that can easily be seen by the naked eye, requiring a lens (optics), lens or microscope to see them clearly. In physics, the microscopic scale is sometimes regarded a ...

characteristics. Molecular

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioche ...

studies of the DNA sequence

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. Th ...

s of the ITS region of the ribosomal DNA

Ribosomal DNA (rDNA) is a DNA sequence that codes for ribosomal RNA. These sequences regulate transcription initiation and amplification, and contain both transcribed and non-transcribed spacer segments.

In the human genome there are 5 chromos ...

from a number of ''Astraeus'' specimens from around the world have helped to clarify phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

relationships within the genus. Based on these results, two Asian "''hygrometricus''" populations have been described as new species: '' A. asiaticus'' and '' A. odoratus'' (synonymous with Petcharat's ''A. thailandicus'' described in 2003). Preliminary DNA analyses suggests that the European ''A. hygrometricus'' described by Persoon is a different species than the North American version described by Morgan, and that the European population may be divided into two distinct phylotype

In taxonomy, a phylotype is an observed similarity used to classify a group of organisms by their phenetic relationship. This phenetic similarity, particularly in the case of asexual organisms, may reflect the evolutionary relationships. The term ...

s, from France (''A. hygrometricus'') and from the Mediterranean ('' A. telleriae''). A follow-up analysis from 2013 named two new North American species: '' A. morganii'' from the Southern US and Mexico and '' A. smithii'' from the Central and Northern United States, and grouped western US specimens in '' A. pteridis''. A 2010 study identified a Japanese species, previously identified as ''A. hygrometricus'', as genetically distinct; it has yet to be officially named.

A form of the species found in Korea and Japan, ''A. hygrometricus'' var. ''koreanus'', was named by V.J. Stanĕk in 1958; it was later (1976) published as a distinct species—''A. koreanus''—by Hanns Kreisel

Hanns Kreisel (16 July 1931 – 18 January 2017) was a German mycologist and professor emeritus.

He was born in Leipzig in 1931. Kreisel was a professor at the University of Greifswald. His field was the classification of fungi, where he has studi ...

. As pointed out by Fangfuk and colleagues, clarification of the proper name for this taxon must await analysis of ''A. hygrometricus'' var. ''koreanus'' specimens from the type locality in North Korea.

Description

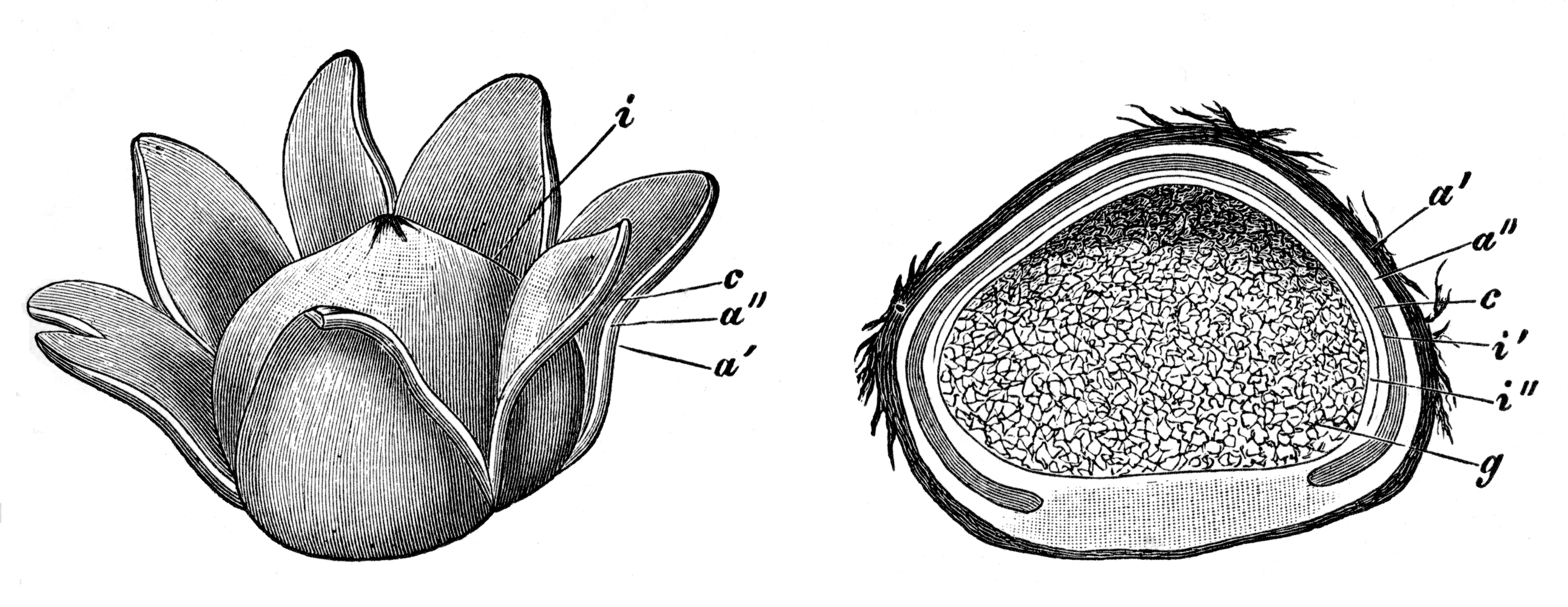

Young specimens of ''A. hygrometricus'' have roughly spherical

Young specimens of ''A. hygrometricus'' have roughly spherical fruit bodies

The sporocarp (also known as fruiting body, fruit body or fruitbody) of fungi is a multicellular structure on which spore-producing structures, such as basidia or asci, are borne. The fruitbody is part of the sexual phase of a fungal life cyc ...

that typically start their development partially embedded in the substrate. A smooth whitish mycelial layer covers the fruit body, and may be partially encrusted with debris. As the fruit body matures, the mycelial layer tears away, and the outer tissue layer, the exoperidium

The peridium is the protective layer that encloses a mass of spores in fungi. This outer covering is a distinctive feature of gasteroid fungi.

Description

Depending on the species, the peridium may vary from being paper-thin to thick and rubber ...

, breaks open in a star-shaped (stellate

Stellate, meaning star-shaped, may refer to:

* Stellate cell

* Stellate ganglion

* Stellate reticulum

* Stellate veins

* Stellate trichomes (hairs) on plants

* Stellate laceration or incision Wound#Open

* Stellate fan-shaped Espalier (one form ...

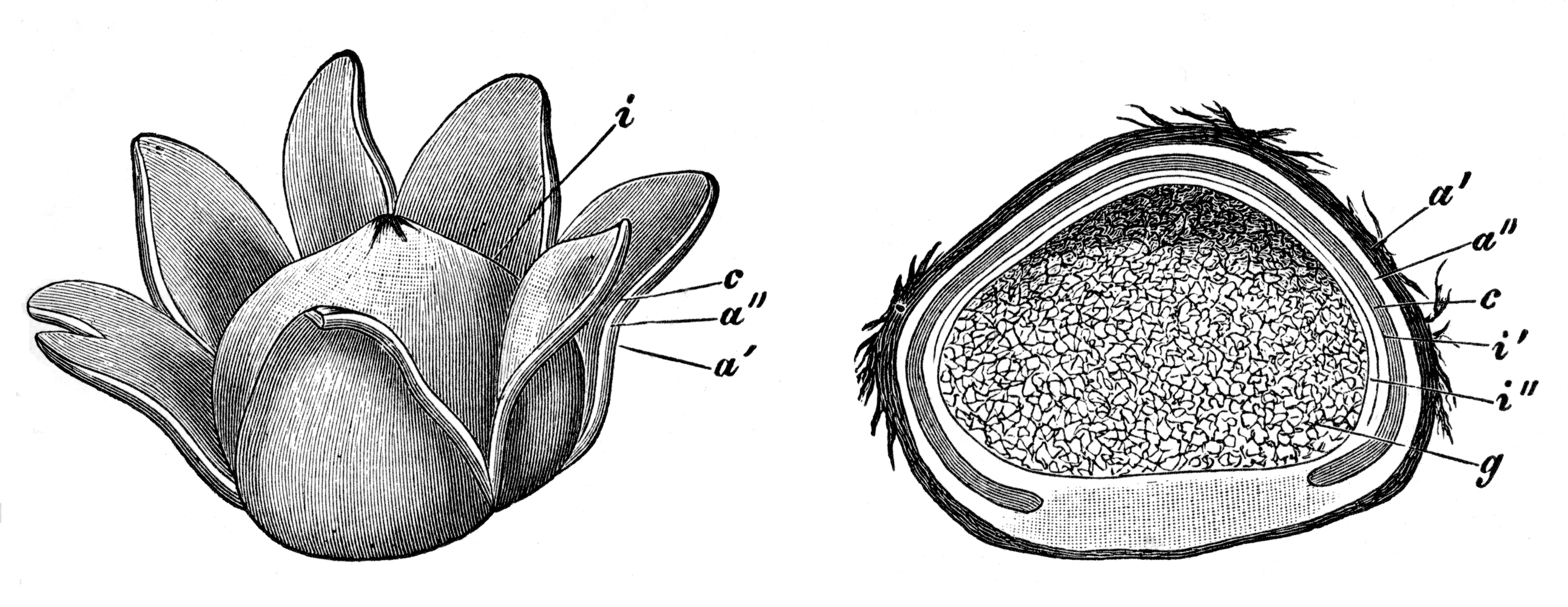

) pattern to form 4–20 irregular "rays". This simultaneously pushes the fruit body above ground to reveal a round spore case enclosed in a thin papery endoperidium. The rays open and close in response to levels of moisture in the environment, opening up in high humidity, and closing when the air is dry. This is possible because the exoperidium is made of several different layers of tissue; the innermost, fibrous layer is hygroscopic

Hygroscopy is the phenomenon of attracting and holding water molecules via either absorption or adsorption from the surrounding environment, which is usually at normal or room temperature. If water molecules become suspended among the substance ...

, and curls or uncurls the entire ray as it loses or gains moisture from its surroundings. This adaptation enables the fruit body to disperse spores at times of optimum moisture, and reduce evaporation during dry periods. Further, dry fruit bodies with the rays curled up may be readily blown about by the wind, allowing them to scatter spores from the pore as they roll.

The fruit body is in diameter from tip to tip when expanded. The exoperidium is thick, and the rays are typically areolate

Lichens are composite organisms made up of multiple species: a fungal partner, one or more photosynthetic partners, and sometimes a basidiomycete yeast. They are regularly grouped by their external appearance – a characteristic known as their ...

(divided into small areas by cracks and crevices) on the upper surface, and are dark grey to black. The spore case is sessile

Sessility, or sessile, may refer to:

* Sessility (motility), organisms which are not able to move about

* Sessility (botany), flowers or leaves that grow directly from the stem or peduncle of a plant

* Sessility (medicine), tumors and polyps that ...

(lacking a stalk), light gray to tan color and broad with a felt-like or scurfy (coated with loose scaly crust) surface; the top of the spore case is opened by an irregular slit, tear or pore. The interior of the spore case, the gleba

Gleba (, from Latin ''glaeba, glēba'', "lump") is the fleshy spore-bearing inner mass of certain fungi such as the puffball or stinkhorn.

The gleba is a solid mass of spores, generated within an enclosed area within the sporocarp. The continu ...

, is white and solid when young, and divided into oval locule

A locule (plural locules) or loculus (plural loculi) (meaning "little place" in Latin) is a small cavity or compartment within an organ or part of an organism (animal, plant, or fungus).

In angiosperms (flowering plants), the term ''locule'' usu ...

s—a characteristic that helps to distinguish it from ''Geastrum''. The gleba becomes brown and powdery as the specimen matures. Small dark hairlike threads (rhizomorph

Mycelial cords are linear aggregations of parallel-oriented hyphae. The mature cords are composed of wide, empty vessel hyphae surrounded by narrower sheathing hyphae. Cords may look similar to plant roots, and also frequently have similar functio ...

s) extend from the base of the fruit body into the substrate. The rhizomorphs are fragile, and often break off after maturity.

The

The spores

In biology, a spore is a unit of sexual or asexual reproduction that may be adapted for dispersal and for survival, often for extended periods of time, in unfavourable conditions. Spores form part of the life cycles of many plants, algae, f ...

are spherical or nearly so, reddish-brown, thick-walled and verrucose (covered with warts and spines). The spores' dimensions are 7–11 µm

The micrometre ( international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: μm) or micrometer (American spelling), also commonly known as a micron, is a unit of length in the International System of Unit ...

; the warts are about 1 µm long. The spores are non-amyloid

Amyloids are aggregates of proteins characterised by a Fibril, fibrillar morphology of 7–13 Nanometer, nm in diameter, a beta sheet (β-sheet) Secondary structure of proteins, secondary structure (known as cross-β) and ability to be Staining, ...

, and will not stain with iodine from Melzer's reagent

Melzer's reagent (also known as Melzer's iodine reagent, Melzer's solution or informally as Melzer's) is a chemical reagent used by mycologists to assist with the identification of fungi, and by phytopathologists for fungi that are plant pathogens ...

. The use of scanning electron microscopy has shown that the spines are 0.90–1.45 µm long, rounded at the tip, narrow, tapered, and sometime joined at the top. The capillitia

Capillitium (pl. capillitia) is a mass of sterile fibers within a fruit body interspersed among spores. It is found in Mycetozoa (slime molds) and gasteroid fungi of the fungal subdivision Agaricomycotina

The subdivision Agaricomycotina, also kn ...

(masses of thread-like sterile fibers dispersed among the spores) are branched, 3.5–6.5 µm in diameter, and hyaline

A hyaline substance is one with a glassy appearance. The word is derived from el, ὑάλινος, translit=hyálinos, lit=transparent, and el, ὕαλος, translit=hýalos, lit=crystal, glass, label=none.

Histopathology

Hyaline cartilage is ...

(translucent). The basidia

A basidium () is a microscopic sporangium (a spore-producing structure) found on the hymenophore of fruiting bodies of basidiomycete fungi which are also called tertiary mycelium, developed from secondary mycelium. Tertiary mycelium is highly-c ...

(spore-bearing cells) are four- to eight-spored, with very short sterigmata

In biology, a sterigma (pl. sterigmata) is a small supporting structure.

It commonly refers to an extension of the basidium (the spore-bearing cells) consisting of a basal filamentous part and a slender projection which carries a spore at the ti ...

. The basidia are arranged in long strings of clusters; individual basidia measure 11–15 by 18–24 µm. The threads of the capillitia arise from the inner surface of the peridium, and are thick-walled, long, interwoven, and branched, measuring 3–5.5 µm thick. The exoperidium (the outer layer of tissue, comprising the rays) is made of four distinct layers of tissue: the mycelial layer contains branched hypha

A hypha (; ) is a long, branching, filamentous structure of a fungus, oomycete, or actinobacterium. In most fungi, hyphae are the main mode of vegetative growth, and are collectively called a mycelium.

Structure

A hypha consists of one or ...

e that are 4–6 μm in diameter; the hyphae of the fibrous layer are 6–8 μm diameter and branched; the collenchyma

The ground tissue of plants includes all tissues that are neither dermal nor vascular. It can be divided into three types based on the nature of the cell walls.

# Parenchyma cells have thin primary walls and usually remain alive after they beco ...

-type layer has branched hyphae of 3–4 μm diameter; the soft layer contains hyphae that are 3–6 μm in diameter.

Edibility

North American sources list ''A. hygrometricus'' as inedible, in some cases because of its toughness. However, they are regularly consumed in Nepal and SouthBengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

, where "local people consume them as delicious food". They are collected from the wild and sold in the markets of India.

A study of a closely related southeast Asian ''Astraeus'' species concluded that the fungus contained an abundance of volatile eight-carbon compounds (including 1-octanol

1-Octanol, also known as octan-1-ol, is the organic compound with the molecular formula CH3(CH2)7OH. It is a fatty alcohol. Many other isomers are also known generically as octanols. 1-Octanol is manufactured for the synthesis of esters for use ...

, 1-octen-3-ol, and 1-octen-3-one

Oct-1-en-3-one (CH2=CHC(=O)(CH2)4CH3), also known as 1-octen-3-one, is the odorant that is responsible for the typical "metallic" smell of metals and blood coming into contact with skin. Oct-1-en-3-one has a strong metallic mushroom-like odor with ...

) that imparted a "mushroom-like, earthy, and pungent odor that was evident as an oily and moss-like smell upon opening the caps". The study's authors further noted that the fruit bodies after cooking have a "roasted, maillard, herbal, and oily flavor". Volatile compounds detected after cooking the mushroom samples included furfural

Furfural is an organic compound with the formula C4H3OCHO. It is a colorless liquid, although commercial samples are often brown. It has an aldehyde group attached to the 2-position of furan. It is a product of the dehydration of sugars, as occurs ...

, benzaldehyde

Benzaldehyde (C6H5CHO) is an organic compound consisting of a benzene ring with a formyl substituent. It is the simplest aromatic aldehyde and one of the most industrially useful.

It is a colorless liquid with a characteristic almond-like odor. ...

, cyclohexenone

Cyclohexenone is an organic compound which is a versatile intermediate used in the synthesis of a variety of chemical products such as pharmaceuticals and fragrances. It is colorless liquid, but commercial samples are often yellow.

Industrially, ...

, and furan

Furan is a heterocyclic organic compound, consisting of a five-membered aromatic ring with four carbon atoms and one oxygen atom. Chemical compounds containing such rings are also referred to as furans.

Furan is a colorless, flammable, highly ...

yl compounds. The regional differences in opinions on edibility are from sources published before it was known that North American and Asian versions of ''A. hygrometricus'' were not always the same; in some cases Asian specimens have been identified as new species, such as ''A. asiaticus'' and ''A. odoratus''.

Similar species

Although ''A. hygrometricus'' bears a superficial resemblance to members of the "true earthstars" ''Geastrum'', it may be readily differentiated from most by the hygroscopic nature of its rays. Hygroscopic earthstars include '' G. arenarium'', '' G. corollinum'', '' G. floriforme'', '' G. recolligens'', and '' G. kotlabae''. Unlike ''Geastrum'', the young fruit bodies of ''A. hygrometricus'' do not have a columella (sterile tissue in the gleba, at the base of the spore sac). ''Geastrum'' tends to have its spore sac opening surrounded by a

Although ''A. hygrometricus'' bears a superficial resemblance to members of the "true earthstars" ''Geastrum'', it may be readily differentiated from most by the hygroscopic nature of its rays. Hygroscopic earthstars include '' G. arenarium'', '' G. corollinum'', '' G. floriforme'', '' G. recolligens'', and '' G. kotlabae''. Unlike ''Geastrum'', the young fruit bodies of ''A. hygrometricus'' do not have a columella (sterile tissue in the gleba, at the base of the spore sac). ''Geastrum'' tends to have its spore sac opening surrounded by a peristome Peristome (from the Greek ''peri'', meaning 'around' or 'about', and ''stoma'', 'mouth') is an anatomical feature that surrounds an opening to an organ or structure. Some plants, fungi, and shelled gastropods have peristomes.

In mosses

In mosses, ...

or a disc, in contrast with the single lacerate slit of ''A. hygrometricus''. There are also several microscopic differences: in ''A. hygrometricus'', the basidia

A basidium () is a microscopic sporangium (a spore-producing structure) found on the hymenophore of fruiting bodies of basidiomycete fungi which are also called tertiary mycelium, developed from secondary mycelium. Tertiary mycelium is highly-c ...

are not arranged in parallel columns, the spores are larger, and the threads of the capillitia are branched and continuous with the hyphae

A hypha (; ) is a long, branching, filamentous structure of a fungus, oomycete, or actinobacterium. In most fungi, hyphae are the main mode of vegetative growth, and are collectively called a mycelium.

Structure

A hypha consists of one or ...

of the peridium. Despite these differences, older specimens can be difficult to distinguish from ''Geastrum'' in the field. One species of ''Geastrum'', '' G. mammosum'', does have thick and brittle rays that are moderately hygroscopic, and could be confused with ''A. hygrometricus''; however, its spores are smaller than ''A. hygrometricus'', typically about 4 µm in diameter.

''Astraeus pteridis

''Astraeus pteridis'', commonly known as the giant hygroscopic earthstar, is a species of false earthstar in the family Diplocystaceae. It was described by American mycologist Cornelius Lott Shear in 1902 under the name ''Scleroderma pteridis' ...

'' is larger, or more when expanded, and often has a more pronounced areolate pattern on the inner surface of the rays. It is found in North America and the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to the African mainland, they are west of Morocc ...

. '' A. asiaticus'' and '' A. odoratus'' are two similar species known from throughout Asia and Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

, respectively. ''A. odoratus'' is distinguished from ''A. hygrometricus'' by a smooth outer mycelial layer with few adhering soil particles, 3–9 broad rays, and a fresh odor similar to moist soil. The spore ornamentation of ''A. odoratus'' is also distinct from ''A. hygrometricus'', with longer and narrower spines that often joined. ''A. asiaticus'' has an outer peridial surface covered with small granules, and a gleba that is purplish-chestnut in color, compared to the smooth peridial surface and brownish gleba of ''A. hygrometricus''. The upper limit of the spore size of ''A. asiaticus'' is larger than that of its more common relative, ranging from 8.75 to 15.2 μm. '' A. koreanus'' (sometimes named as the variety ''A. hygrometricus'' var. ''koreanus''; see Taxonomy) differs from the more common form in its smaller size, paler fruit body, and greater number of rays; microscopically, it has smaller spores (between 6.8 and 9 μm in diameter), and the spines on the spores differ in length and morphology. It is known from Korea and Japan.

Habitat, distribution, and ecology

''Astraeus hygrometricus'' is anectomycorrhizal

An ectomycorrhiza (from Greek ἐκτός ', "outside", μύκης ', "fungus", and ῥίζα ', "root"; pl. ectomycorrhizas or ectomycorrhizae, abbreviated EcM) is a form of symbiotic relationship that occurs between a fungal symbiont, or mycobi ...

fungus and grows in association with a broad range of tree species. The mutualistic association between tree roots and the mycelium

Mycelium (plural mycelia) is a root-like structure of a fungus consisting of a mass of branching, thread-like hyphae. Fungal colonies composed of mycelium are found in and on soil and many other substrate (biology), substrates. A typical single ...

of the fungus helps the trees extract nutrients (particularly phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ear ...

) from the earth; in exchange, the fungus receives carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may or ma ...

s from photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is a process used by plants and other organisms to convert light energy into chemical energy that, through cellular respiration, can later be released to fuel the organism's activities. Some of this chemical energy is stored i ...

. In North America, associations with oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' (; Latin "oak tree") of the beech family, Fagaceae. There are approximately 500 extant species of oaks. The common name "oak" also appears in the names of species in related genera, notably ''L ...

and pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden accep ...

are usual, while in India, it has been noted to grow commonly with chir pine

''Pinus roxburghii'', commonly known as chir pine or longleaf Indian pine, is a species of pine tree native to the Himalayas. It was named after William Roxburgh.

Description

''Pinus roxburghii'' is a large tree reaching with a trunk diameter ...

(''Pinus roxburghii'') and sal

Sal, SAL, or S.A.L. may refer to:

Personal name

* Sal (name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or nickname

Places

* Sal, Cape Verde, an island and municipality

* Sal, Iran, a village in East Azerbaijan Province

* Ca ...

(''Shorea robusta''). The false earthstar is found on the ground in open fields, often scattered or in groups, especially in nutrient-poor, sandy or loam

Loam (in geology and soil science) is soil composed mostly of sand (particle size > ), silt (particle size > ), and a smaller amount of clay (particle size < ). By weight, its mineral composition is about 40–40–20% concentration of sand–sil ...

y soils. It has also been reported to grow on rocks, preferring acid substrates like slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

and granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained (phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies undergro ...

, while avoiding substrates rich in lime

Lime commonly refers to:

* Lime (fruit), a green citrus fruit

* Lime (material), inorganic materials containing calcium, usually calcium oxide or calcium hydroxide

* Lime (color), a color between yellow and green

Lime may also refer to:

Botany ...

. In Nepal, fruit bodies have been collected at elevations of . Fruit bodies typically appear in autumn, although the dry fruit bodies are persistent and may last up to several years. '' Gelatinipulvinella astraeicola'' is a leotiaceous fungus with minute, gelatinous, pulvinate (cushion-shaped) apothecia

An ascocarp, or ascoma (), is the fruiting body ( sporocarp) of an ascomycete phylum fungus. It consists of very tightly interwoven hyphae and millions of embedded asci, each of which typically contains four to eight ascospores. Ascocarps are mo ...

, known to grow only on the inner surface of the rays of dead ''Astraeus'' species, including ''A. hygrometricus''.

The genus has a cosmopolitan distribution

In biogeography, cosmopolitan distribution is the term for the range of a taxon that extends across all or most of the world in appropriate habitats. Such a taxon, usually a species, is said to exhibit cosmopolitanism or cosmopolitism. The ext ...

except for arctic

The Arctic ( or ) is a polar regions of Earth, polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic consists of the Arctic Ocean, adjacent seas, and parts of Canada (Yukon, Northwest Territories, Nunavut), Danish Realm (Greenla ...

, alpine

Alpine may refer to any mountainous region. It may also refer to:

Places Europe

* Alps, a European mountain range

** Alpine states, which overlap with the European range

Australia

* Alpine, New South Wales, a Northern Village

* Alpine National Pa ...

and cold temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5° to 66.5° N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout t ...

regions; it is common in temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5° to 66.5° N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout t ...

and tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

regions of the world. It has been collected in Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, and South America.

Bioactive compounds

polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wa ...

s from a number of species have attracted research interest for their immunomodulatory

Immunotherapy or biological therapy is the treatment of disease by activating or suppressing the immune system. Immunotherapies designed to elicit or amplify an immune response are classified as ''activation immunotherapies,'' while immunotherap ...

and antitumor

Cancer can be treated by surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, hormonal therapy, targeted therapy (including immunotherapy such as monoclonal antibody therapy) and synthetic lethality, most commonly as a series of separate treatments (e.g. ...

properties. Extracts from ''A. hygrometricus'' containing the polysaccharide named AE2 were found to inhibit the growth of several tumor cell lines in laboratory tests, and stimulated the growth of splenocyte A splenocyte can be any one of the different white blood cell types as long as it is situated in the spleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filte ...

s, thymocyte

A Thymocyte is an immune cell present in the thymus, before it undergoes transformation into a T cell. Thymocytes are produced as stem cells in the bone marrow and reach the thymus via the blood. Thymopoiesis describes the process which turns thymo ...

s, and bone marrow

Bone marrow is a semi-solid tissue found within the spongy (also known as cancellous) portions of bones. In birds and mammals, bone marrow is the primary site of new blood cell production (or haematopoiesis). It is composed of hematopoietic ce ...

cells from mice. The extract also stimulated mouse cells associated with the immune system

The immune system is a network of biological processes that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to parasitic worms, as well as cancer cells and objects such as wood splinte ...

; specifically, it enhanced the activity of mouse natural killer cell

Natural killer cells, also known as NK cells or large granular lymphocytes (LGL), are a type of cytotoxic lymphocyte critical to the innate immune system that belong to the rapidly expanding family of known innate lymphoid cells (ILC) and repres ...

s, stimulated macrophage

Macrophages (abbreviated as M φ, MΦ or MP) ( el, large eaters, from Greek ''μακρός'' (') = large, ''φαγεῖν'' (') = to eat) are a type of white blood cell of the immune system that engulfs and digests pathogens, such as cancer cel ...

s to produce nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (nitrogen oxide or nitrogen monoxide) is a colorless gas with the formula . It is one of the principal oxides of nitrogen. Nitric oxide is a free radical: it has an unpaired electron, which is sometimes denoted by a dot in its che ...

, and enhanced production of cytokine

Cytokines are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling. Cytokines are peptides and cannot cross the lipid bilayer of cells to enter the cytoplasm. Cytokines have been shown to be involved in autocrin ...

s. The activation of macrophages by AE2 might be mediated by a mitogen-activated protein kinase

A mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK or MAP kinase) is a type of protein kinase that is specific to the amino acids serine and threonine (i.e., a serine/threonine-specific protein kinase). MAPKs are involved in directing cellular responses to ...

pathway of signal transduction

Signal transduction is the process by which a chemical or physical signal is transmitted through a cell as a series of molecular events, most commonly protein phosphorylation catalyzed by protein kinases, which ultimately results in a cellula ...

. AE2 is made of the simple sugars mannose

Mannose is a sugar monomer of the aldohexose series of carbohydrates. It is a C-2 epimer of glucose. Mannose is important in human metabolism, especially in the glycosylation of certain proteins. Several congenital disorders of glycosylation ...

, glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, using ...

, and fucose

Fucose is a hexose deoxy sugar with the chemical formula C6H12O5. It is found on ''N''-linked glycans on the mammalian, insect and plant cell surface. Fucose is the fundamental sub-unit of the seaweed polysaccharide fucoidan. The α(1→3) link ...

in a 1:2:1 ratio.

In addition to the previously known steroid

A steroid is a biologically active organic compound with four rings arranged in a specific molecular configuration. Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes that alter membrane fluidity; and a ...

compounds ergosta-7,22-diene-3-ol acetate and ergosta-4,6,8-(14),22-tetraene-3-one, three unique triterpenes—derivatives

The derivative of a function is the rate of change of the function's output relative to its input value.

Derivative may also refer to:

In mathematics and economics

* Brzozowski derivative in the theory of formal languages

* Formal derivative, an ...

of 3-hydroxy-lanostane

Lanostane or 4,4,14α-trimethylcholestane is a chemical compound with formula . It is a polycyclic hydrocarbon, specifically a triterpene. It is an isomer of cucurbitane.

The name is applied to two stereoisomers, distinguished by the prefixes 5� ...

—have been isolated from fruit bodies of ''A. hygrometricus''. The compounds, named astrahygrol, 3-''epi''-astrahygrol, and astrahygrone (3-oxo-25''S''-lanost-8-eno-26,22-lactone), have δ-lactone

Lactones are cyclic carboxylic esters, containing a 1-oxacycloalkan-2-one structure (), or analogues having unsaturation or heteroatoms replacing one or more carbon atoms of the ring.

Lactones are formed by intramolecular esterification of the co ...

(a six-membered ring) in the side chain

In organic chemistry and biochemistry, a side chain is a chemical group that is attached to a core part of the molecule called the "main chain" or backbone. The side chain is a hydrocarbon branching element of a molecule that is attached to a l ...

—a chemical feature previously unknown in the basidiomycetes

Basidiomycota () is one of two large divisions that, together with the Ascomycota, constitute the subkingdom Dikarya (often referred to as the "higher fungi") within the kingdom Fungi. Members are known as basidiomycetes. More specifically, Basi ...

. A previously unknown steryl ester (3β, 5α-dihydroxy-(22''E'', 24''R'')-ergosta-7,22-dien-6α-yl palmitate) has been isolated from mycelia

Mycelium (plural mycelia) is a root-like structure of a fungus consisting of a mass of branching, thread-like hyphae. Fungal colonies composed of mycelium are found in and on soil and many other substrates. A typical single spore germinates in ...

grown in liquid culture. The compound has a polyhydroxylated ergostane

Ergostane is a tetracyclic triterpene, also known as 24''S''-methylcholestane. The compound itself has no known uses; however various functionalized analogues are produced by plants and animals. The most important of these are the heavily derivati ...

-type nucleus.

Ethanol extracts of the fruit body are high in antioxidant

Antioxidants are compounds that inhibit oxidation, a chemical reaction that can produce free radicals. This can lead to polymerization and other chain reactions. They are frequently added to industrial products, such as fuels and lubricant ...

activity, and have been shown in laboratory tests to have anti-inflammatory

Anti-inflammatory is the property of a substance or treatment that reduces inflammation or swelling. Anti-inflammatory drugs, also called anti-inflammatories, make up about half of analgesics. These drugs remedy pain by reducing inflammation as o ...

activity comparable to the drug diclofenac

Diclofenac, sold under the brand name Voltaren, among others, is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to treat pain and inflammatory diseases such as gout. It is taken by mouth or rectally in a suppository, used by injection, or ...

. Studies with mouse model

A model organism (often shortened to model) is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the working ...

s have also demonstrated hepatoprotective (liver-protecting) ability, possibly by restoring diminished levels of the antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase

Superoxide dismutase (SOD, ) is an enzyme that alternately catalyzes the dismutation (or partitioning) of the superoxide () radical into ordinary molecular oxygen (O2) and hydrogen peroxide (). Superoxide is produced as a by-product of oxygen me ...

and catalase

Catalase is a common enzyme found in nearly all living organisms exposed to oxygen (such as bacteria, plants, and animals) which catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen. It is a very important enzyme in protecting t ...

caused by experimental exposure to the liver-damaging chemical carbon tetrachloride

Carbon tetrachloride, also known by many other names (such as tetrachloromethane, also IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry, recognised by the IUPAC, carbon tet in the cleaning industry, Halon-104 in firefighting, and Refrigerant-10 in HVAC ...

.

Traditional beliefs

This earthstar has been used intraditional Chinese medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is an alternative medical practice drawn from traditional medicine in China. It has been described as "fraught with pseudoscience", with the majority of its treatments having no logical mechanism of action ...

as a hemostatic

An antihemorrhagic (antihæmorrhagic) agent is a substance that promotes hemostasis (stops bleeding). It may also be known as a hemostatic (also spelled haemostatic) agent.

Antihemorrhagic agents used in medicine have various mechanisms of action: ...

agent; the spore dust is applied externally to stop wound bleeding and reduce chilblain

Chilblains, also known as pernio, is a medical condition in which damage occurs to capillary beds in the skin, most often in the hands or feet, when blood perfuses into the nearby tissue resulting in redness, itching, inflammation, and possibly ...

s. Two India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

n forest tribes, the Baiga and the Bharia of Madhya Pradesh

Madhya Pradesh (, ; meaning 'central province') is a state in central India. Its capital is Bhopal, and the largest city is Indore, with Jabalpur, Ujjain, Gwalior, Sagar, and Rewa being the other major cities. Madhya Pradesh is the seco ...

, have been reported to use the fruit bodies medicinally. The spore mass is blended with mustard seed

Mustard seeds are the small round seeds of various mustard plants. The seeds are usually about in diameter and may be colored from yellowish white to black. They are an important spice in many regional foods and may come from one of three diff ...

oil, and used as a salve

A salve is a medical ointment used to soothe the surface of the body.

Medical uses

Magnesium sulphate paste is used as a drawing salve to treat small boils and infected wounds and to remove 'draw' small splinters. Black ointment, or Ichthyol ...

against burns. The Blackfoot

The Blackfoot Confederacy, ''Niitsitapi'' or ''Siksikaitsitapi'' (ᖹᐟᒧᐧᒣᑯ, meaning "the people" or " Blackfoot-speaking real people"), is a historic collective name for linguistically related groups that make up the Blackfoot or Bla ...

of North America called the fungus "fallen stars", considering them to be stars fallen to the earth during supernatural events.

See also

*Medicinal mushrooms

Medicinal fungi are fungi that contain metabolites or can be induced to produce metabolites through biotechnology to develop prescription drugs. Compounds successfully developed into drugs or under research include antibiotics, anti-cancer drugs, ...

References

External links

{{featured article Boletales Fungi of Asia Fungi of Australia Fungi of Europe Fungi of North America Fungi of Colombia Inedible fungi Medicinal fungi Fungi described in 1801 Taxa named by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon