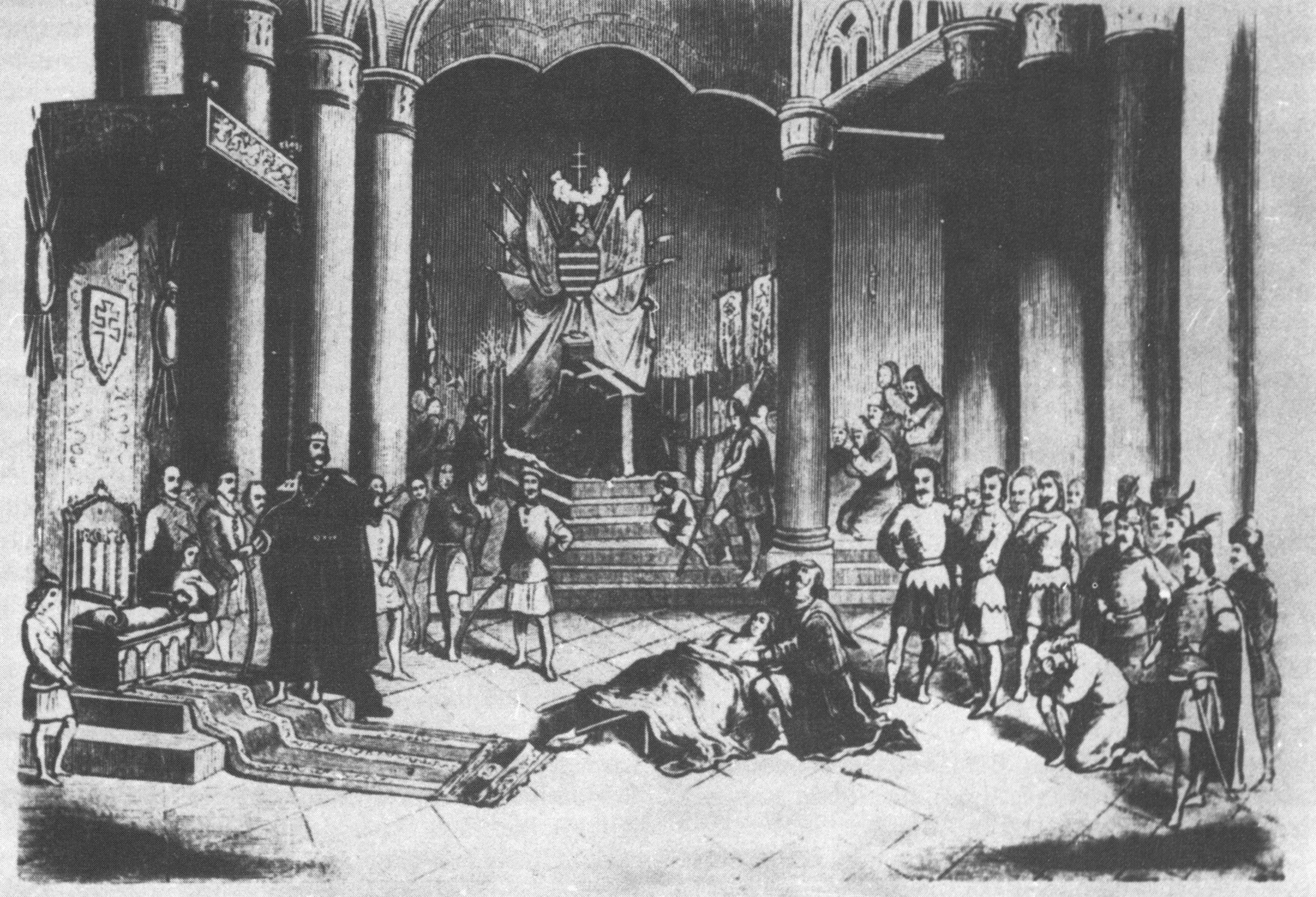

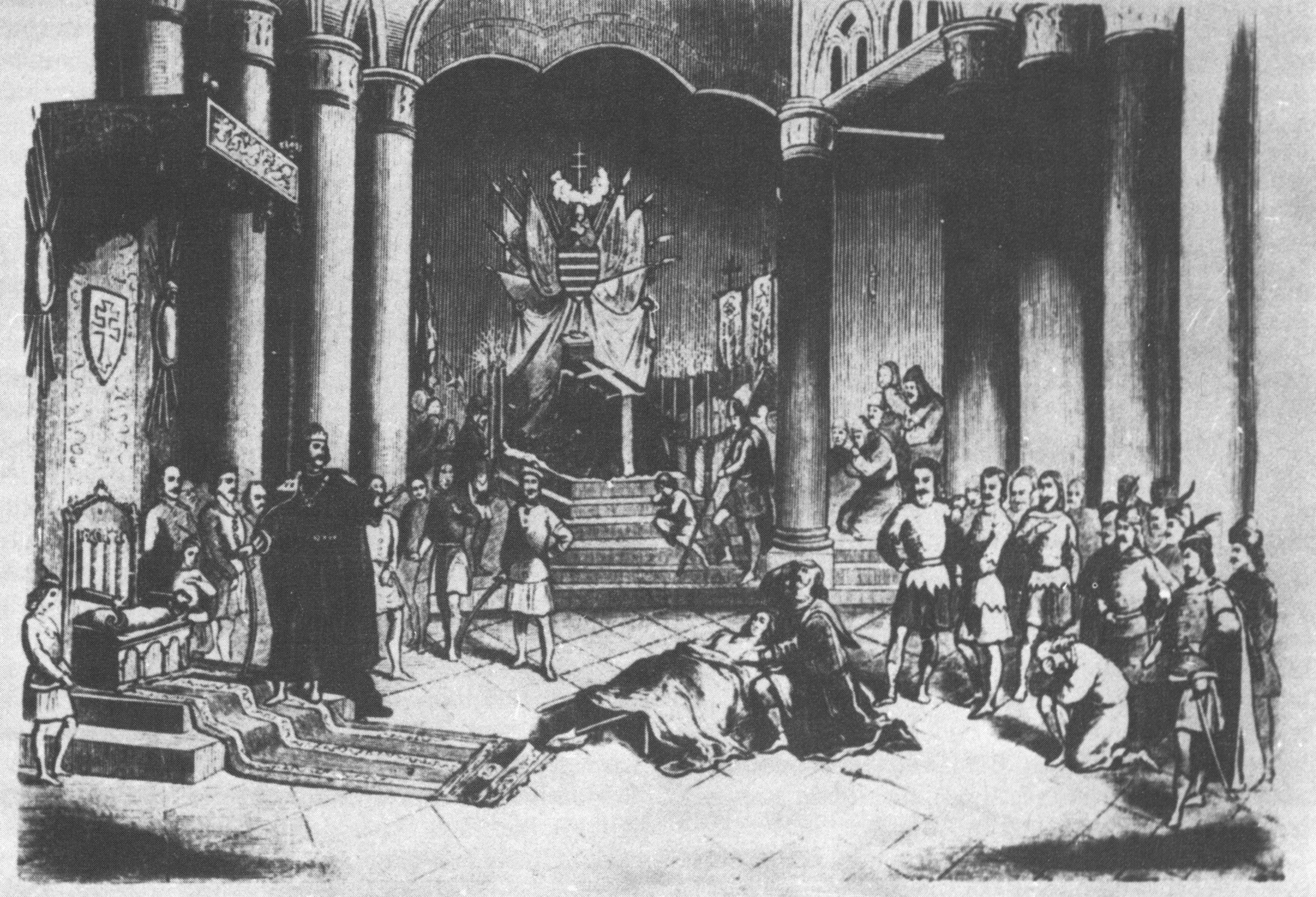

Assassination of Gertrude of Merania on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Andrew II ascended the Hungarian throne in 1205. As queen consort, Gertrude had unusual (but not unprecedented, see Helena of Serbia) influence over governmental affairs.

Andrew II ascended the Hungarian throne in 1205. As queen consort, Gertrude had unusual (but not unprecedented, see Helena of Serbia) influence over governmental affairs.

In order to support his protege Danylo Romanovich against

In order to support his protege Danylo Romanovich against

Only three sources mentions the proper date of the murder. A 15th-century section of a Bavarian source, the Founders of the Monastery of Diessen (''De fundatoribus monasterii Diessenses'') refers the date to 28 September but with the year 1200, and cannot be considered an authentic report. The Annals of the Dominicans of Vienna (''Annales Praedicatorum Vindobonensium'') from the late 13th century preserved the exact date of assassination, 28 September, but without adding the year. Historian László Veszprémy accepted the date as authentic, since the annals also used necrologies as source, which always focused on the specific month and day instead of the year. The ''Aschaffenburgi Psalterium'', which was compiled for

Only three sources mentions the proper date of the murder. A 15th-century section of a Bavarian source, the Founders of the Monastery of Diessen (''De fundatoribus monasterii Diessenses'') refers the date to 28 September but with the year 1200, and cannot be considered an authentic report. The Annals of the Dominicans of Vienna (''Annales Praedicatorum Vindobonensium'') from the late 13th century preserved the exact date of assassination, 28 September, but without adding the year. Historian László Veszprémy accepted the date as authentic, since the annals also used necrologies as source, which always focused on the specific month and day instead of the year. The ''Aschaffenburgi Psalterium'', which was compiled for

According to a royal charter of Duke Stephen from 1270, the lands of Bánk's son-in-law, a certain Simon in Bereg and Szabolcs counties were also confiscated prior to that. Early historiography identified Bánk's son-in-law with Simon Kacsics, however, as historian Gyula Pauler proved, while Simon Kacsics had descendants (his last known offspring was still alive in 1299), Bánk's son-in-law, Simon died without issue prior to 1270. Pauler considered Simon was among the killers, and his involvement caused his father-in-law's political downfall years later. Veszprémy argued there is no record of Simon's active involvement in the murder, according to the unclear term of the medieval legal system. Körmendi emphasized Simon's lands escheated to the crown because of his death without issue and not for his alleged involvement in the assassination.

The participation of John, Archbishop of Esztergom in the conspiracy also arose. His involvement is mentioned by Italian scholar Boncompagno da Signa's tractate ''Rhetorica novissima'',

According to a royal charter of Duke Stephen from 1270, the lands of Bánk's son-in-law, a certain Simon in Bereg and Szabolcs counties were also confiscated prior to that. Early historiography identified Bánk's son-in-law with Simon Kacsics, however, as historian Gyula Pauler proved, while Simon Kacsics had descendants (his last known offspring was still alive in 1299), Bánk's son-in-law, Simon died without issue prior to 1270. Pauler considered Simon was among the killers, and his involvement caused his father-in-law's political downfall years later. Veszprémy argued there is no record of Simon's active involvement in the murder, according to the unclear term of the medieval legal system. Körmendi emphasized Simon's lands escheated to the crown because of his death without issue and not for his alleged involvement in the assassination.

The participation of John, Archbishop of Esztergom in the conspiracy also arose. His involvement is mentioned by Italian scholar Boncompagno da Signa's tractate ''Rhetorica novissima'',

The Annals of Admont (''Annales Admontenses'') and the 15th-century historian

The Annals of Admont (''Annales Admontenses'') and the 15th-century historian

With the beginning of the narration of the Annals of Göttweig, several contemporary and near-contemporary works mark the queen's pro-German attitude as a motive for her assassination. A side note from the Hungarian chronicler Anonymus (see above) strengthens this standpoint. However, as mentioned in the background section, there is no trace of the beneficiary status of the Germans in the sources and royal donations of the time.

The Austrian Rhyming Chronicle is the earliest known work, which preserved the alleged story of that Archbishop Berthold raped Bánk Bár-Kalán's wife, which was the immediate cause of the assassination of the queen, who acted as a

With the beginning of the narration of the Annals of Göttweig, several contemporary and near-contemporary works mark the queen's pro-German attitude as a motive for her assassination. A side note from the Hungarian chronicler Anonymus (see above) strengthens this standpoint. However, as mentioned in the background section, there is no trace of the beneficiary status of the Germans in the sources and royal donations of the time.

The Austrian Rhyming Chronicle is the earliest known work, which preserved the alleged story of that Archbishop Berthold raped Bánk Bár-Kalán's wife, which was the immediate cause of the assassination of the queen, who acted as a

In accordance with her intention, Gertrude was buried in the Pilis Abbey, while certain parts of her body were buried in the monastery of Lelesz. In the latter case, Andrew II ordered that two priests pray for his wife's spiritual salvation. The ruins of her tomb were discovered during the excavations carried out by László Gerevich in the Pilis Abbey between 1967 and 1982. Art historian Imre Takács considered the

In accordance with her intention, Gertrude was buried in the Pilis Abbey, while certain parts of her body were buried in the monastery of Lelesz. In the latter case, Andrew II ordered that two priests pray for his wife's spiritual salvation. The ruins of her tomb were discovered during the excavations carried out by László Gerevich in the Pilis Abbey between 1967 and 1982. Art historian Imre Takács considered the

# The Latest Rhetoric (''Rhetorica novissima''): Boncompagno da Signa's rhetoric textbook, written before 1235, is the earliest work, which contains the story of the letter. Accordingly, King Andrew accused Archbishop John of participating in the murder before the Holy See. However Pope Innocent III, pointing out the correct use of commas, acquitted the archbishop from the charges. These references emphasize the letter's unintended ambiguity and, thus, John's approval of murder. Boncompagno resided in the papal court from 1229 to 1234, it is plausible he heard the story during his stay there.

#

# The Latest Rhetoric (''Rhetorica novissima''): Boncompagno da Signa's rhetoric textbook, written before 1235, is the earliest work, which contains the story of the letter. Accordingly, King Andrew accused Archbishop John of participating in the murder before the Holy See. However Pope Innocent III, pointing out the correct use of commas, acquitted the archbishop from the charges. These references emphasize the letter's unintended ambiguity and, thus, John's approval of murder. Boncompagno resided in the papal court from 1229 to 1234, it is plausible he heard the story during his stay there.

#

Bonfini's chronicle was also translated into German in 1545, which allowed the story of Bánk to spread in the German-speaking territories as well. Poet

Bonfini's chronicle was also translated into German in 1545, which allowed the story of Bánk to spread in the German-speaking territories as well. Poet

Gertrude of Merania

Gertrude of Merania ( 1185 – 28 September 1213) was Queen of Hungary as the first wife of Andrew II from 1205 until her assassination. She was regent during her husband's absence.

Life

She was the daughter of the Bavarian Count Berthold IV ...

, the queen consort of Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

as the first wife of King Andrew II (r. 1205–1235), was assassinated by a group of Hungarian lords on 28 September 1213 in the Pilis Mountains during a royal hunting. Leopold VI, Duke of Austria

Leopold VI (15 October 1176 – 28 July 1230), known as Leopold the Glorious, was Duke of Styria from 1194 and Duke of Austria from 1198 to his death in 1230. He was a member of the House of Babenberg.

Biography

Leopold VI was the younger son of ...

and Gertrude's brother Berthold

Berthold or Berchtold is a Germanic given name and surname. It is derived from two elements, ''berht'' meaning "bright" and ''wald'' meaning "(to) rule". It may refer to:

*Bertholdt Hoover, a fictional List_of_Attack_on_Titan_characters, character ...

, Archbishop of Kalocsa

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdioc ...

were also wounded but survived the attack.

The assassination became one of the most high-profile criminal cases in the history of Hungary

Hungary in its modern (post-1946) borders roughly corresponds to the Great Hungarian Plain (the Pannonian Basin). During the Iron Age, it was located at the crossroads between the cultural spheres of the Celtic tribes (such as the Scordisci, Boi ...

, which has prompted widespread astonishment across Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

in the 13th century. Despite a relatively diverse and large number of domestic and foreign sources, the motivation of the killers is unclear. According to contemporary sources, Gertrude's blatant favoritism towards her German kinsmen and courtiers stirred up discontent among the native lords, which resulted in her murder thereafter. Later tradition says Gertrude's brother Berthold raped the wife of Bánk Bár-Kalán

Bánk of the Bár-Kalán clan ( hu, Bárkalán nembéli Bánk; died after 1222) was an influential nobleman in the Kingdom of Hungary in the first decades of the 13th century. He was Palatine of Hungary between 1212 and 1213, Judge royal from 1221 ...

, one of the lords, who, along with his companions, took revenge on the grievance. This story inspired many subsequent chroniclers and literary works in Hungary and Europe.

Background

Gertrude was born into theHouse of Andechs

The House of Andechs was a feudal line of German princes in the 12th and 13th centuries. The counts of Dießen-Andechs (1100 to 1180) obtained territories in northern Dalmatia on the Adriatic seacoast, where they became Margraves of Istria and ult ...

as the daughter of Berthold, Duke of Merania

Berthold IV (c. 1159 – 12 August 1204), a member of the House of Andechs, was Margrave of Istria and Carniola (as Berthold II). By about 1180/82 he assumed the title of Duke of Merania, referring to the Adriatic seacoast of Kvarner which his ...

. The Duchy of Merania

The Duchy of Merania, it, Ducato di Merania, sl, Vojvodina Meranija, hr, Vojvodina Meranije was a fiefdom of the Holy Roman Empire from 1152 until 1248. The dukes of Merania were recognised as princes of the Empire enjoying imperial immediacy ...

, a fiefdom of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

, laid in the peninsula of Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; ist, Eîstria; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian, Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; formerly in Latin and in Ancient Greek) is the larges ...

and also had nominal suzerainty over the coast of the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to t ...

. Merania was located in the neighborhood of Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

, belonging to Croatia in personal union with Hungary

The Kingdom of Croatia ( la, Regnum Croatiae; hr, Kraljevina Hrvatska, ''Hrvatsko kraljevstvo'', ''Hrvatska zemlja'') entered a personal union with the Kingdom of Hungary in 1102, after a period of rule of kings from the Trpimirović and Svetosl ...

, which was ruled by Emeric

Emerich, Emeric, Emerick and Emerik are given names and surnames. They may refer to:

Given name Pre-modern era

* Saint Emeric of Hungary (c. 1007–1031), son of King Stephen I of Hungary

* Emeric, King of Hungary (1174–1204)

* Emeric Kökénye ...

from 1196 to 1204. His younger brother Andrew constantly rebelled against him. Following a victory against the king, he forced Emeric to cede Croatia and Dalmatia as an appanage to him in 1197. In practice, Andrew administered the provinces as an independent monarch. Although, Emeric defeated his brother after another conspiration in 1199, Andrew was allowed to return to his duchy in 1200. Andrew married Gertrude of Merania sometime between 1200 and 1203; his father-in-law Berthold owned extensive domains in the Holy Roman Empire along the borders of Andrew's duchy. Gertrude's influence and political involvement, already in the years before Andrew's reign as king, are clearly shown by the fact that when Emeric defeated his brother again in 1203, he found it necessary to send Gertrude back to her native land Merania.

Andrew II ascended the Hungarian throne in 1205. As queen consort, Gertrude had unusual (but not unprecedented, see Helena of Serbia) influence over governmental affairs.

Andrew II ascended the Hungarian throne in 1205. As queen consort, Gertrude had unusual (but not unprecedented, see Helena of Serbia) influence over governmental affairs. Theodoric of Apolda Dietrich of Apolda (died 1302) was a German Dominican hagiographer, writing towards the end of the thirteenth century.

He wrote a popular life of Elizabeth of Hungary, including mythical elements such as the sorcerer Klingsor. He also wrote a leng ...

in the hagiography

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian hagiographies migh ...

of Elizabeth of Hungary

Elizabeth of Hungary (german: Heilige Elisabeth von Thüringen, hu, Árpád-házi Szent Erzsébet, sk, Svätá Alžbeta Uhorská; 7 July 1207 – 17 November 1231), also known as Saint Elizabeth of Thuringia, or Saint Elisabeth of Thuringia, ...

emphasizes Gertrude's "masculine characteristics". Two sources testify that Gertrude exercised power during the king's absence on military campaigns. When Andrew II launched a campaign against the Cuman

The Cumans (or Kumans), also known as Polovtsians or Polovtsy (plural only, from the Russian language, Russian Exonym and endonym, exonym ), were a Turkic people, Turkic nomadic people comprising the western branch of the Cuman–Kipchak confede ...

chieftain Gubasel in Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

, Gertrude performed a judicial activity over a lawsuit between Abbot Uros of Pannonhalma and the castle serfs of Pressburg

Bratislava (, also ; ; german: Preßburg/Pressburg ; hu, Pozsony) is the capital and largest city of Slovakia. Officially, the population of the city is about 475,000; however, it is estimated to be more than 660,000 — approximately 140% of ...

(present-day Bratislava, Slovakia) around 1212 or 1213. Another note mentions that when Gertrude was assassinated, the royal seal was lost. Both remarks imply that Gertrude acted as royal governor both times when Andrew led a campaign to Bulgaria and Halych

Halych ( uk, Га́лич ; ro, Halici; pl, Halicz; russian: Га́лич, Galich; german: Halytsch, ''Halitsch'' or ''Galitsch''; yi, העליטש) is a historic city on the Dniester River in western Ukraine. The city gave its name to the P ...

, respectively, which caused resentment among the local elite.

Her blatant favoritism towards her German kinsmen and courtiers stirred up discontent among the native lords. His younger brother Berthold was appointed Archbishop of Kalocsa in 1206 and was made Ban of Croatia

Ban of Croatia ( hr, Hrvatski ban) was the title of local rulers or office holders and after 1102, viceroys of Croatia. From the earliest periods of the Croatian state, some provinces were ruled by bans as a ruler's representative (viceroy) an ...

and Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

in 1209. His another two brothers, Ekbert, Bishop of Bamberg This is a list of bishops and archbishops of the Prince-Bishopric of Bamberg and Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Bamberg in Germany.

__TOC__ Bishops, 1007–1245

* Eberhard I 1007-1040

* Suidger von Morsleben 1040-1046 (Later Pope Clement II)

* Hartw ...

, and Henry II, Margrave of Istria, fled to Hungary in 1208 after they were accused of participating in the murder of Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

, King of the Germans

This is a list of monarchs who ruled over East Francia, and the Kingdom of Germany (''Regnum Teutonicum''), from the division of the Frankish Empire in 843 and the collapse of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 until the collapse of the German Empir ...

. Andrew granted large domains to Bishop Ekbert in the Szepesség region (now Spiš

Spiš (Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

, Slovakia). Andrew's generosity towards his wife's German relatives and courtiers discontented the local lords. According to historian Gyula Kristó

Gyula Kristó (11 July 1939 – 24 January 2004) was a Hungarian historian and medievalist, member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

The Hungarian Academy of Sciences ( hu, Magyar Tudományos Akadémia, MTA) is the most important and pres ...

, the anonymous author

Anonymous works are works, such as art or literature, that have an anonymous, undisclosed, or unknown creator or author. In the case of very old works, the author's name may simply be lost over the course of history and time. There are a number ...

of '' The Deeds of the Hungarians'' referred to the Germans from the Holy Roman Empire when he sarcastically mentioned that " the Romans graze on the goods of Hungary." However there is no source for that Gertrude ever appointed German courtiers in his queenly court. Although it is possible that the 26th article of the Golden Bull of 1222

The Golden Bull of 1222 was a golden bull, or edict, issued by Andrew II of Hungary. King Andrew II was forced by his nobles to accept the Golden Bull (Aranybulla), which was one of the first examples of constitutional limits being placed on the ...

("Hungarian properties cannot be given to foreigners") and the 23th article of the Golden Bull of 1231, which prescribes that foreigners can only get court positions if they stay in Hungary, because such people only "take the country's wealth broad

Broad(s) or The Broad(s) may refer to:

People

* A slang term for a woman.

* Broad (surname), a surname

Places

* Broad Peak, on the border between Pakistan and China, the 12th highest mountain on Earth

* The Broads, a network of mostly na ...

, reflect the negative experiences of Gertrude's favoritism, the few surviving royal donation letters from the period do not prove the mass acquisition of land by the Germans either; the local provost Adolph was granted lands in Szepesség due to the intervention of Gertrude and his brothers in 1209, while a certain Lenguer was granted a small portion in the village Szántó upon the request of Archbishop Berthold. Both donations are considered insignificant gains compared to other acquisitions of the period, the beneficiaries of which were members of the native Hungarian elite. Officials of the queen's court (for instance, its count or head), including the future assassin Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a sur ...

, were in all cases Hungarian magnates.

Assassination

In order to support his protege Danylo Romanovich against

In order to support his protege Danylo Romanovich against Mstislav Mstislavich

Mstislav Mstislavich the Daring (russian: Мстисла́в II Мстисла́вич Удатный, uk, Мстислав Мстиславич Удатний, translit=Mstyslav Mstyslavych Udatnyi; died c. 1228) prince of Tmutarakan and Cherni ...

, Andrew II departed for a new royal campaign against the Principality of Halych in the summer of 1213. During his absence, Hungarian lords captured and murdered Gertrude and many of her courtiers. Late 19th-century Hungarian historian Gyula Pauler was the first scholar, who compiled a professional synthesis, as well as a detailed examination of the circumstances of the murder, based on comprehensive source research and considering the conditions of the era. His findings were unanimously accepted by Hungarian historiography in the following decades.

According to Pauler, Queen Gertrude and her escort, also attending by his brother Archbishop Berthold and the reigning Austrian duke Leopold VI, took part in hunting in the Pilis Hills in late September 1213, when a group of Hungarian lords stormed the queen's tent and assassinated her partly for political reasons, partly because of personal grievances. Among the perpetrators were the queen's former confidant Peter, son of Töre, brothers Simon Kacsics

Simon from the kindred Kacsics ( hu, Kacsics nembeli Simon, hr, Šimun Kačić; died after 1228) was a Hungarian distinguished nobleman from the ''gens'' Kacsics (Kačić). He was one of the leading instigators of Queen Gertrude's assassinatio ...

and Michael Kacsics and a certain Simon, son-in-law of Palatine

A palatine or palatinus (in Latin; plural ''palatini''; cf. derivative spellings below) is a high-level official attached to imperial or royal courts in Europe since Roman times.

Bánk Bár-Kalán. It is possible, as Pauler considered, that the palatine himself and John, Archbishop of Esztergom

John ( hu, János; died November 1223) was a prelate in the Kingdom of Hungary in the 12th and 13th centuries. He was Bishop of Csanád (now Cenad in Romania) between 1198 and 1201, Archbishop of Kalocsa from 1202 to 1205 and Archbishop of Eszter ...

were also involved in the planning of the conspiracy, but they remained in the background at the time of the assassination. Gertrude was brutally slaughtered, while Berthold and Leopold were physically assaulted, but they were released subsequently and managed to flee the scene. Based on new sources and philological considerations, historian Tamás Körmendi reexamined the circumstances of the assassination in his 2014 study.

Date and location

Regarding the year, the contemporary and near-contemporary sources place the assassination in many different years, within a wide range between 1200 and 1218. However, Gertrude was firmly alive in 1211, when she sent her daughter Elizabeth with a substantial dowry to theLandgraviate of Thuringia

The Duchy of Thuringia was an eastern frontier march of the Merovingian kingdom of Austrasia, established about 631 by King Dagobert I after his troops had been defeated by the forces of the Slavic confederation of Samo at the Battle of Wogastis ...

in that year. On the other hand, her widower Andrew II mourned her death in his two surviving royal charters issued in 1214. Most of the narrative sources put the date of the murder to the year 1213. Tamás Körmendi accepted this year, since the majority of these works are the earliest and seemingly most authentic chronicles, including the Annals of Göttweig (''Annales Gotwicenses'') and the Annals of Salzburg (''Annales Salisburgenses''). 1213 is the only year, which appears in works that cannot be compared or related philologically, which makes it beyond doubt that the murder took place at that time.

Only three sources mentions the proper date of the murder. A 15th-century section of a Bavarian source, the Founders of the Monastery of Diessen (''De fundatoribus monasterii Diessenses'') refers the date to 28 September but with the year 1200, and cannot be considered an authentic report. The Annals of the Dominicans of Vienna (''Annales Praedicatorum Vindobonensium'') from the late 13th century preserved the exact date of assassination, 28 September, but without adding the year. Historian László Veszprémy accepted the date as authentic, since the annals also used necrologies as source, which always focused on the specific month and day instead of the year. The ''Aschaffenburgi Psalterium'', which was compiled for

Only three sources mentions the proper date of the murder. A 15th-century section of a Bavarian source, the Founders of the Monastery of Diessen (''De fundatoribus monasterii Diessenses'') refers the date to 28 September but with the year 1200, and cannot be considered an authentic report. The Annals of the Dominicans of Vienna (''Annales Praedicatorum Vindobonensium'') from the late 13th century preserved the exact date of assassination, 28 September, but without adding the year. Historian László Veszprémy accepted the date as authentic, since the annals also used necrologies as source, which always focused on the specific month and day instead of the year. The ''Aschaffenburgi Psalterium'', which was compiled for Gertrude of Aldenberg

Blessed Gertrude of Aldenberg , (c. October 1227 – 13 August 1297) was a German noblewoman and abbess. She was the daughter of Elizabeth of Hungary and of Louis IV, Landgrave of Thuringia. She became a Premonstratensian canoness regular at the ...

, the queen's granddaughter, lists the time of death of various members of the House of Andechs; accordingly Queen Gertrude died on 28 September (the year is not given). The three unrelated sources confirm that the assassination did indeed take place on 28 September 1213.

Based on the narrations of the Austrian Rhyming Chronicle (''Chronicon rhytmicum Austriacum'') and the aforementioned Annals of the Dominicans of Vienna, which write that Gertrude was killed in her "field tent", and the fact that the queen was buried in the Pilis Abbey

Pilis Abbey ( hu, pilisi apátság) was a Cistercian monastery in the Pilis Hills in the Kingdom of Hungary. It was founded in 1184 by monks who came from Acey Abbey in France at the invitation of Béla III of Hungary. It was dedicated to the Vi ...

thereafter, Gyula Pauler claimed the assassination took place in the nearby Pilis royal forest on the occasion of a royal hunting. The subsequent Hungarian historiography accepted the theory without any reservations. Tamás Körmendi emphasized the speculative nature of this data; he emphasized, other sources say that the queen was assassinated either in her palace, bedroom or the royal military camp. The Galician–Volhynian Chronicle

The ''Galician–Volhynian Chronicle'' ( uk, Галицько-Волинський літопис), called "Halicz-Wolyn Chronicle" in Polish historiography, is a prominent benchmark of the Old Ruthenian literature and historiographyKotlyar, M. G ...

writes that Gertrude was murdered in the Premonstratensian

The Order of Canons Regular of Prémontré (), also known as the Premonstratensians, the Norbertines and, in Britain and Ireland, as the White Canons (from the colour of their habit), is a religious order of canons regular of the Catholic Church ...

monastery of Lelesz (present-day Leles, Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

), while accompanying her husband into the royal campaign against Halych. A royal charter from 1214 refers to that "a certain part of her ertrude'sbody" was buried in Lelesz. Pauler argued Andrew II on his way to Halych was caught at Lelesz by the messenger who brought the news of her death, who presented a piece of the queen's corpse as evidence, which was subsequently buried there. In contrast, Körmendi considered the non-transportable pieces of the mutilated queen were quickly buried in the Lelesz monastery, near which the assassination could have taken place, perhaps in the Patak royal forest along the river Bodrog

The Bodrog is a river in eastern Slovakia and north-eastern Hungary. It is a tributary to the river Tisza. The Bodrog is formed by the confluence of the rivers Ondava and Latorica near Zemplín in eastern Slovakia. It crosses the Slovak–Hun ...

.

Perpetrators

Peter, son of Töre, a former confidant of Gertrude, was the only sure participant in the assassination. One of the earliest records, the all three manuscripts of the Annals of Salzburg (its main corpus was written before 1216) contain that element which say the "queen of the Hungarians ..was slaughtered by a certain count Peter". WhenBéla IV

Béla may refer to:

* Béla (crater), an elongated lunar crater

* Béla (given name), a common Hungarian male given name

See also

* Bela (disambiguation)

* Belá (disambiguation)

* Bělá (disambiguation) Bělá, derived from ''bílá'' (''whit ...

(the eldest son of Andrew and Gertrude) donated Peter's former lands to the newly founded the Cistercian

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint ...

Bélakút Abbey, the king states that these estates were confiscated from Peter, who "committed the crime of high treason by murdering our mother".

Subsequent Hungarian royal charters also refer to brothers Simon and Michael Kacsics as leading instigators of Gertrude's assassination. When Duke Béla, gaining power over the royal council, started reclaiming King Andrew's land grants throughout Hungary, he forced his father to confiscate the estates of those noblemen who had plotted against his mother one and a half decade earlier. Accordingly, Simon Kacsics lost his lands and villages in Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

and Nógrád County

Nógrád ( hu, Nógrád megye, ; sk, Novohradská župa) is a counties of Hungary, county ( hu, megye) of Hungary. It sits on the northern edge of Hungary and borders Slovakia.

Description

Nógrád county lies in northern Hungary. It shares bor ...

which were granted by Denis Tomaj

Denis from the kindred Tomaj ( hu, Tomaj nembeli Dénes; died 11 April 1241) was a Hungarian influential baron in the first half of the 13th century, who served as the Palatine of Hungary under King Béla IV from year 1235 to 1241, until his dea ...

and his clan. In his charter, Andrew II referred to Simon's active participation in the murder of his consort. Accordingly, Simon "by a new and unheard-of kind of wickedness and vileness, cruelly and horribly armed for hateful machinations, conspiring with his accomplices: bloodthirsty and treacherous men, to the shame and dishonor of our royal crown, was involved in the death of the well-remembered Queen Gertrude, our dearest consort". The land confiscation in 1228 might be a sign of the subsequent retaliation after an increased role in national politics by princes Béla and Coloman Coloman, es, Colomán (german: Koloman (also Slovak, Czech, Croatian), it, Colomanno, ca, Colomà; hu, Kálmán)

The Germanic origin name Coloman used by Germans since the 9th century.

* Coloman, King of Hungary

* Coloman of Galicia-Lodomeria ...

since the early 1220s, as historian Gyula Pauler argued. Körmendi argued, it is quite unrealistic that Andrew II appointed Simon to baronial dignities after the murder, even his few opportunities for punish the perpetrators, as Pauler had claimed. Accordingly, Simon was not considered among the assassins of Gertrude immediately after the murder. As Simon was mentioned as armed participant in the act, it is presumable that he became a victim of power intrigues and accused of conspiracy purely out of political reasons. Simon's brother, Michael Kacsics is also listed among the perpetrators by a royal charter of Ladislaus IV from 1277, when returned the lands to the sons of the aforementioned Denis Tomaj from Michael's descendants.

Two royal charters of Béla IV narrate that Bánk Bár-Kalán had participated in the assassination. In 1240, Béla IV donated Bánk's former lands, which he had lost for "his sin of high treason", since "he conspired to murder our dearest mother ertrude— he lost all his possessions, not exactly unjustly, for he would have deserved more severe revenge by the judgment that common sense had brought upon him". When Béla granted another landholdings in 1262, the king noted too that those estates escheated to the crown from "our disloyal, Ban Bánk". The fact that Bánk held court positions even after the assassination questions the authenticity of the above accounts, or at least his leading role in the conspiracy. Historian Gyula Pauler considered Bánk managed to survive the subsequent retaliation, because Andrew II was not strong enough to punish one of the most powerful barons, while the main assassin Peter, son of Töre was executed. According to János Karácsonyi, Bánk supported the conspiracy, but he did not mastermind the crime. Historian Erik Fügedi argued Bánk was the most prestigious member of the conspiracy, which in the following decades magnified his role and thus became the executor and chief of the assassination in the later narratives. Tamás Körmendi emphasized the late 19th-century historiography incorrectly considered Andrew II as a weak ruler. Körmendi argued Bánk was accused of involvement in the assassination sometime only between 1222 and 1240. Along with other charged barons – Simon Kacsics, Michael Kacsics and Bánk's son-in-law Simon – it is presumable that Bánk became a victim of power intrigues and political purge, and accused of conspiracy purely out of political reasons, while Peter, son of Töre indeed assassinated the queen.

According to a royal charter of Duke Stephen from 1270, the lands of Bánk's son-in-law, a certain Simon in Bereg and Szabolcs counties were also confiscated prior to that. Early historiography identified Bánk's son-in-law with Simon Kacsics, however, as historian Gyula Pauler proved, while Simon Kacsics had descendants (his last known offspring was still alive in 1299), Bánk's son-in-law, Simon died without issue prior to 1270. Pauler considered Simon was among the killers, and his involvement caused his father-in-law's political downfall years later. Veszprémy argued there is no record of Simon's active involvement in the murder, according to the unclear term of the medieval legal system. Körmendi emphasized Simon's lands escheated to the crown because of his death without issue and not for his alleged involvement in the assassination.

The participation of John, Archbishop of Esztergom in the conspiracy also arose. His involvement is mentioned by Italian scholar Boncompagno da Signa's tractate ''Rhetorica novissima'',

According to a royal charter of Duke Stephen from 1270, the lands of Bánk's son-in-law, a certain Simon in Bereg and Szabolcs counties were also confiscated prior to that. Early historiography identified Bánk's son-in-law with Simon Kacsics, however, as historian Gyula Pauler proved, while Simon Kacsics had descendants (his last known offspring was still alive in 1299), Bánk's son-in-law, Simon died without issue prior to 1270. Pauler considered Simon was among the killers, and his involvement caused his father-in-law's political downfall years later. Veszprémy argued there is no record of Simon's active involvement in the murder, according to the unclear term of the medieval legal system. Körmendi emphasized Simon's lands escheated to the crown because of his death without issue and not for his alleged involvement in the assassination.

The participation of John, Archbishop of Esztergom in the conspiracy also arose. His involvement is mentioned by Italian scholar Boncompagno da Signa's tractate ''Rhetorica novissima'', Alberic of Trois-Fontaines

Alberic of Trois-Fontaines (french: Aubri or ''Aubry de Trois-Fontaines''; la, Albericus Trium Fontium) (died 1252) was a medieval Cistercian chronicler who wrote in Latin. He was a monk of Trois-Fontaines Abbey in the diocese of Châlons-sur-M ...

' ''Chronica'' and Matthew of Paris

Matthew Paris, also known as Matthew of Paris ( la, Matthæus Parisiensis, lit=Matthew the Parisian; c. 1200 – 1259), was an English Benedictine monk, chronicler, artist in illuminated manuscripts and cartographer, based at St Albans Abbey i ...

' ''Chronica Majora

The ''Chronica Majora'' is the seminal work of Matthew Paris, a member of the English Benedictine community of St Albans and long-celebrated historian. The work begins with Creation and contains annals down to the year of Paris' death of 1259. ...

'' and ''Historia Anglorum''. These works unanimously note John's famous phrase in his letter to Hungarian nobles planning the assassination of Gertrude: "''Reginam occidere nolite timere bonum est si omnes consentiunt ego non contradico''", can be roughly translated into "Kill Queen you must not fear will be good if all agree I do not oppose". The meaning is highly dependent on punctuation: either the speaker wishes a queen killed ("Kill Queen, you must not fear, will be good if all agree, I do not oppose") or not ("Kill Queen you must not, fear will be good, if all agree I do not, oppose"). László Veszprémy considered the anecdote first appeared in the Annals of Salzburg after an oral spread among the lower clergymen. On the other hand, Tamás Körmendi argued the ambiguous letter was subscribed as a result of a subsequent insertion. It is possible that Boncompagno heard the story in the Roman Curia and incorporated it into his rhetoric dissertation and textbook (published in 1235, the first written source of John's alleged letter). Both Boncompagno and Alberic mention that Andrew accused John of participating in the murder before the Holy See. However Pope Innocent III

Pope Innocent III ( la, Innocentius III; 1160 or 1161 – 16 July 1216), born Lotario dei Conti di Segni (anglicized as Lothar of Segni), was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1198 to his death in 16 J ...

, pointing out the correct use of commas, acquitted the archbishop from the charges. These references emphasize the letter's unintended ambiguity and, thus, John's approval of murder. Körmendi emphasized the historiographical doubts regarding the authenticity of the letter, as John retained his influence in the upcoming years after the assassination. The historian also argued the preservation of the letter would have been irrational step, moreover the majority of the Hungarian nobility were illiterate during that time.

Witnesses

The various sources mention only four people who were present as eyewitnesses during the assassination, but due to the differing credibility of the sources, it is certain that not all of them were actually present. A group of works (see below) marks Archbishop Berthold, Gertrude's brother as a key figure in the case. However, only the Galician–Volhynian Chronicle states that Berthold was present during the assassination. Despite the doubtful authenticity of the chronicle's report, historian Tamás Körmendi accepted the information on Berthold's presence, since a letter of Pope Innocent III to Archbishop John of Esztergom in January 1214 refers to the physical assault on Berthold. According to the pope's letter, during the rebellion many clergy and monks in theArchdiocese of Kalocsa

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

suffered physical insult and material damage. Innocent instructed John to excommunicate

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

the perpetrators. In addition, the pope also sent a letter to the "dukes of Poland" not to give any refuge to the perpetrators who might flee abroad.

The Annals of Admont (''Annales Admontenses'') and the 15th-century historian

The Annals of Admont (''Annales Admontenses'') and the 15th-century historian Thomas Ebendorfer Thomas Ebendorfer (10 August 1388 – 12 January 1464) was an Austrian historian, professor, and statesman.

Born at Korneuburg District, Haselbach, in Lower Austria, he studied at the University of Vienna, where he received the degree of Master of ...

's Austrian Chronicle (''Chronicon Austriae'') mention the presence of the Austrian duke Leopold VI too. Despite relevant factual errors (e.g. the date), Tamás Körmendi accepted the information of the mid-13th-century annals, since the work provides a very detailed and authentic account of the activities of the Austrian dukes. Accordingly, Leopold arrived to Hungary after his return from Calatrava la Vieja

Calatrava la Vieja (formerly just ''Calatrava'') is a medieval site and original nucleus of the Order of Calatrava. It is now part of the Archaeological Parks (''Parques Arqueológicos'') of the Community of Castile-La Mancha. Situated at ''Carri ...

during the Albigensian Crusade

The Albigensian Crusade or the Cathar Crusade (; 1209–1229) was a military and ideological campaign initiated by Pope Innocent III to eliminate Catharism in Languedoc, southern France. The Crusade was prosecuted primarily by the French crown ...

. The Annals of Admont claims that the assassins intended to kill Leopold too, but Körmendi refused this, considering the monks of the Admont Abbey

Admont Abbey (german: Stift Admont) is a Benedictine monastery located on the Enns River in the town of Admont, Austria. The oldest remaining monastery in Styria, Admont Abbey contains the largest monastic library in the world as well as a lon ...

(its right of patronage

The right of patronage (in Latin ''jus patronatus'' or ''ius patronatus'') in canon law (Catholic Church), Roman Catholic canon law is a set of rights and obligations of someone, known as the patron in connection with a gift of land (benefice). I ...

was possessed by the duke) sought to increase the importance of Leopold.

The continuation of the Royal Chronicle of Cologne (''Chronica regia Coloniensis'') and three other works – Annals of Admont, Rainer of Liége's annals (''Reinerus Leodiensis'') and the Galician–Volhynian Chronicle –, which used its text, claim that Andrew II was present during the assassination of his wife, the Galician–Volhynian Chronicle even states that the real target was actually the king. In contrast, the Annals of Salzburg and four derivative texts refer to the fact that the assassination took place when Andrew II led a campaign into Halych. Körmendi emphasized there is no sign of a nationwide rebellion against the king in 1213 and the subsequent royal charters do not mention that the conspirators attempted to murder Andrew himself. Andrew refers to conspiracies against him in 1209–1210 and 1214 too, but not in 1213.

A single source, the Chronicle of the Anonymus of Leoben (''Chronicon Leobiense'') claims that Gertrude's other brother, Ekbert was the one who forced the wife of a Hungarian lord to commit adultery, which resulted the assassination. The chronicle says Ekbert was present during the crime. It is plausible that the anonymous author confused Ekbert with Berthold. Although Ekbert resided in Hungary for a while, but departed for Austria long before the assassination.

Motivations

With the beginning of the narration of the Annals of Göttweig, several contemporary and near-contemporary works mark the queen's pro-German attitude as a motive for her assassination. A side note from the Hungarian chronicler Anonymus (see above) strengthens this standpoint. However, as mentioned in the background section, there is no trace of the beneficiary status of the Germans in the sources and royal donations of the time.

The Austrian Rhyming Chronicle is the earliest known work, which preserved the alleged story of that Archbishop Berthold raped Bánk Bár-Kalán's wife, which was the immediate cause of the assassination of the queen, who acted as a

With the beginning of the narration of the Annals of Göttweig, several contemporary and near-contemporary works mark the queen's pro-German attitude as a motive for her assassination. A side note from the Hungarian chronicler Anonymus (see above) strengthens this standpoint. However, as mentioned in the background section, there is no trace of the beneficiary status of the Germans in the sources and royal donations of the time.

The Austrian Rhyming Chronicle is the earliest known work, which preserved the alleged story of that Archbishop Berthold raped Bánk Bár-Kalán's wife, which was the immediate cause of the assassination of the queen, who acted as a procuress

Procuring or pandering is the facilitation or provision of a prostitute or other sex worker in the arrangement of a sex act with a customer. A procurer, colloquially called a pimp (if male) or a madam (if female, though the term pimp has still ...

in the adultery. According to this narration, Bánk led the conspirators and stabbed Gertrude with a sword personally. The chronicle was compiled by a Hungarian cleric in Klosterneuburg Abbey, Lower Austria

Lower Austria (german: Niederösterreich; Austro-Bavarian: ''Niedaöstareich'', ''Niedaestareich'') is one of the nine states of Austria, located in the northeastern corner of the country. Since 1986, the capital of Lower Austria has been Sankt P ...

around 1270. The chronicle claims that Béla IV ordered to slaughter all participants of the assassination, after he ascended the Hungarian throne in 1235. Its text was utilized by the Annals of the Dominicans of Vienna at the end of the 13th century. In addition, the annals used other source too, since, unlike the Austrian Rhyming Chronicle, it mentions Bánk's alleged German name ("''Prenger''") and the exact date of the assassination. The 14th-century Illuminated Chronicle

The ''Chronicon Pictum'' (Latin for "illustrated chronicle", English: ''Illuminated Chronicle'' or ''Vienna Illuminated Chronicle'', hu, Képes Krónika, sk, Obrázková kronika, german: Illustrierte Chronik, also referred to as ''Chronica Hung ...

(''Chronicon Pictum'') took over the story too, which then made a decisive contribution to making the story rooted in the Hungarian chronicle and historiographical tradition and, subsequently, the Hungarian-language literature and culture. Other works, which spread this narration too, emphasize the innocence of Gertrude regarding the adultery between Berthold and Bánk's wife.

The Annals of Admont, the Royal Chronicle of Cologne, Rainer of Liége's annals and the Galician–Volhynian Chronicle claim the real target of the assassination was King Andrew II himself. Historian Bálint Hóman

Bálint Hóman (29 December 1885 – 2 June 1951) was a Hungarian scholar and politician who served as Minister of Religion and Education twice: between 1932–1938 and between 1939–1942. He died in prison in 1951 for his support of the fasc ...

assumed the conspirators attempted to oust Andrew from power in order to replace him with his heir, the seven-year-old Béla. However, since Andrew led a campaign to Halych during the assassination, killing the queen certainly would not have caused his downfall. Gertrude's active role in the government as a queen was an unusual phenomenon in Hungary, which could be opposed by a group of barons. Tamás Körmendi does not reject the possibility of personal revenge as a motivation for the assassination. It is possible that Peter, who was considered still the queen's confidant in early 1213, became involved in an undefined personal conflict with Queen Gertrude, but its nature, due to lack of resources, remained obscure.

Aftermath

When Andrew II heard the news of his wife's murder, he interrupted the campaign in Halych and returned to home. He ordered the execution of the murderer, Peter, son of Töre, who was impaled "along with others" in the autumn of 1213, according to the Annals of Marbach (''Annales Marbacenses''). The Annals of Salzburg says that Peter and others were beheaded the night after the assassination. The continuation of Magnus von Reichersberg's chronicle narrates that, Peter was executed along with his wife and entire family the day after the assassination. The Anonymus of Leoben narrates that Peter's lands were also confiscated and Béla IV, now as king, donated Peter's former lands – including the eponymous Pétervárad ("Peter's Castle", present-dayPetrovaradin

Petrovaradin ( sr-cyr, Петроварадин, ) is a historic town in the Serbian province of Vojvodina, now a part of the city of Novi Sad. As of 2011, the urban area has 14,810 inhabitants. Lying on the right bank of the Danube, across from t ...

, part of the agglomeration of Novi Sad

Novi Sad ( sr-Cyrl, Нови Сад, ; hu, Újvidék, ; german: Neusatz; see below for other names) is the second largest city in Serbia and the capital of the autonomous province of Vojvodina. It is located in the southern portion of the Pan ...

, Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

) – to the newly founded the Cistercian Bélakút Abbey, which belonged to the Archdiocese of Kalocsa. A royal charter from 1237 confirms this narration.

According to a mainstream view of the Hungarian historiography, Peter's accomplices, including Palatine Bánk, did not receive severe punishments, due to the current political situation and Andrew's power instability. Only Duke Béla, son of Andrew and Gertrude took revenge after he was appointed Duke of Transylvania

The Duke of Transylvania ( hu, erdélyi herceg; la, dux Transylvaniae) was a title of nobility four times granted to a son or a brother of the Hungarian monarch. The dukes of the first and second creations, Béla (1226–1235) and Stephen ( ...

and started to revise his father's policy. In 1228, he confiscated the estates of Bánk and the Kacsics brothers, who had plotted against his mother. Tamás Körmendi considered they were all victims of power intrigues and political purge, and accused of conspiracy purely out of political reasons.

In accordance with her intention, Gertrude was buried in the Pilis Abbey, while certain parts of her body were buried in the monastery of Lelesz. In the latter case, Andrew II ordered that two priests pray for his wife's spiritual salvation. The ruins of her tomb were discovered during the excavations carried out by László Gerevich in the Pilis Abbey between 1967 and 1982. Art historian Imre Takács considered the

In accordance with her intention, Gertrude was buried in the Pilis Abbey, while certain parts of her body were buried in the monastery of Lelesz. In the latter case, Andrew II ordered that two priests pray for his wife's spiritual salvation. The ruins of her tomb were discovered during the excavations carried out by László Gerevich in the Pilis Abbey between 1967 and 1982. Art historian Imre Takács considered the French Gothic

French Gothic architecture is an architectural style which emerged in France in 1140, and was dominant until the mid-16th century. The most notable examples are the great Gothic cathedrals of France, including Notre-Dame Cathedral, Reims Cathedra ...

style of Gertrude's tomb bears similarities to the drawings of Villard de Honnecourt

Villard de Honnecourt (''Wilars dehonecort'', ''Vilars de Honecourt'') was a 13th-century artist from Picardy in northern France. He is known to history only through a surviving portfolio or "sketchbook" containing about 250 drawings and designs ...

, who spent a considerable time in Hungary in those years, but Takács did not attribute the sculptures to him. It is possible that one of the excavated skeletons (a 30-40 year old woman) is identical with Gertrude's corpse.

Shortly after the death of Gertrude, Andrew II married Yolanda of Courtenay

Yolanda of Courtenay (c. 1200 – June 1233), was a Queen of Hungary as the second wife of King Andrew II of Hungary.

Yolanda was the daughter of Count Peter II of Courtenay and his second wife, Yolanda of Flanders, the sister of Baldwin I ...

in February 1215. The king did not intend for the new wife to have a governmental role, experiencing the previous sharp opposition from the Hungarian elite. When Andrew left Hungary in order to fought in the Fifth Crusade

The Fifth Crusade (1217–1221) was a campaign in a series of Crusades by Western Europeans to reacquire Jerusalem and the rest of the Holy Land by first conquering Egypt, ruled by the powerful Ayyubid sultanate, led by al-Adil, brother of Sala ...

in 1217–1218, he entrusted the regency to Archbishop John and Palatine Julius Kán, instead of Yolanda, who remained passive in political matters throughout her life. Andrew's third wife Beatrice d'Este

Beatrice d'Este (29 June 1475 – 3 January 1497), was Duchess of Bari and Milan by marriage to Ludovico Sforza (known as "il Moro"). She was one of the most important personalities of the time and, despite her short life, she was a major play ...

had a similar concept of role. According to Gyula Kristó, Gertrude's unpopular pro-German attitude negatively affected the portrayal of Blessed Gisela, the consort of the first Hungarian king Saint Stephen I

Pope Stephen I ( la, Stephanus I) was the bishop of Rome from 12 May 254 to his death on 2 August 257.Mann, Horace (1912). "Pope St. Stephen I" in ''The Catholic Encyclopedia''. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company. He was later Canonizati ...

(r. 1000–1038) in the contemporary Hungarian chronicles, which in fact described Gertrude's activity. The ''Illuminated Chronicle'' says that Gisela "determined to appoint as king the queen's brother, Peter the German or rather Venetian, with the intention that Queen Gisela might then according to her desire fulfill all the impulses of her will, and that the kingdom of Hungary might lose its liberty and be subjected without hindrance to the dominion of the Germans". In fact, Gisela had tense relationship with Stephen's nephew and successor Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a sur ...

, the son of the Venetian doge

The Doge of Venice ( ; vec, Doxe de Venexia ; it, Doge di Venezia ; all derived from Latin ', "military leader"), sometimes translated as Duke (compare the Italian '), was the chief magistrate and leader of the Republic of Venice between 726 ...

Otto Orseolo

Otto Orseolo ( it, Ottone Orseolo, also ''Urseolo''; c. 992−1032) was the Doge of Venice from 1008 to 1026. He was the third son of Pietro II Orseolo and Maria Candiano, whom he succeeded at the age of sixteen, becoming the youngest doge in Ven ...

. To avoid persecution, the contemporary chronicles narrated Gertrude's assumed pro-German influence inserted between the events of the 11th century. The death of Gertrude and the "negative experiences" associated with her resulted the decline of a separate queenly court with own courtiers and partisans in the 13th-century Hungary. Even the 1298 laws prescribed that only Hungarian-born barons can hold positions and offices in the queen's court.

Sources

Beside the 14th-century Illuminated Chronicle and six royal charters, approximately 60 medieval external sources – before the era ofRenaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

– refer to the assassination of Queen Gertrude. Among them, only 28 sources contain more information and details beyond the fact of the murder. While Flórián Mátyás was the first scholar, who collected the narrations in the early 20th century, historians László Veszprémy then Tamás Körmendi organized the sources according to content, determining the philological relationship between them and the time of their origin.

Group A – Pro-German attitude

This group contains those narrations which mark Gertrude's favoritism towards her German or Meranian courtiers as the cause of her assassination. These are the earliest sources on the murder, the texts were created within a few years in the territory of the Holy Roman Empire. # Annals of Göttweig (''Annales Gotwicenses''): the earliest foreign record of the assassination, this section written in theBenedictine

, image = Medalla San Benito.PNG

, caption = Design on the obverse side of the Saint Benedict Medal

, abbreviation = OSB

, formation =

, motto = (English: 'Pray and Work')

, foun ...

Göttweig Abbey

Göttweig Abbey (german: Stift Göttweig) is a Benedictine monastery near Krems in Lower Austria. It was founded in 1083 by Altmann, Bishop of Passau.

History

Göttweig Abbey was founded as a monastery of canons regular by Blessed Altmann (c ...

in Lower Austria

Lower Austria (german: Niederösterreich; Austro-Bavarian: ''Niedaöstareich'', ''Niedaestareich'') is one of the nine states of Austria, located in the northeastern corner of the country. Since 1986, the capital of Lower Austria has been Sankt P ...

, around the same time as the assassination. Accordingly, the magnates of Hungary, "uniting their armed and violent hands", murdered Gertrude because of their "hatred towards Germans".

# Annals of Marbach (''Annales Marbacenses''): written in the Augustinian Augustinian may refer to:

*Augustinians, members of religious orders following the Rule of St Augustine

*Augustinianism, the teachings of Augustine of Hippo and his intellectual heirs

*Someone who follows Augustine of Hippo

* Canons Regular of Sain ...

Marbach Abbey in Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

around 1230. Körmendi considered the friars were informed through Cistercians from Hungary via the monks of Neuburg Abbey. The annals write that Gertrude was assassinated because of her "largesse and generosity" towards her German entourage. It narrates that one of the murderers, ''ispán

The ispánRady 2000, p. 19.''Stephen Werbőczy: The Customary Law of the Renowned Kingdom of Hungary in Three Parts (1517)'', p. 450. or countEngel 2001, p. 40.Curta 2006, p. 355. ( hu, ispán, la, comes or comes parochialis, and sk, župan)Kirs ...

'' Peter was impaled "through his belly" by Andrew II. Unidentified others were also captured and executed with different penalties. Körmendi argued this note is one of the most reliable and trustable written sources of the murder.

# Annals of Admont (''Annales Admontenses''): its first continuation (in the period 1140–1257) contains unique elements on the assassination. Accordingly, Gertrude was murdered because of the Hungarians' "hatred towards Germans" in the presence of King Andrew II. The text also emphasizes that Duke Leopold was present during the assassination. It incorrectly put the date of the crime to the end of the year 1211. Regarding the assassination, the text may have been revised and rewritten at least once.

# Royal Chronicle of Cologne (''Chronica regia Coloniensis''): The text, its continuation (written from 1202 to 1220), places the date of the murder to the year 1210. It contains a multi-distorted narration; Andrew was unable to capture a fort with his army. Upon Gertrude's advice, he hired German knights from her entourage, who successfully besieged this fort. The Germans were granted many gifts and positions. The jealous Hungarians intended to assassinate Andrew II, but Gertrude warned her husband. Andrew and his men left the camp, but Gertrude remained, and, thereafter, was brutally slaughtered with spears and stakes. Andrew captured all conspirators, along with their supporters, and ordered to execute them.

# Rainer of Liége's annals (''Reinerus Leodiensis''): the Benedictine author (1157 – after 1230), who continued the annals of the St. James Abbey in Liège, used the same source as the Royal Chronicle of Cologne regarding the assassination. According to the text, Andrew II, the real target, narrowly escaped from the palace, where Gertrude was assassinated.

Group B – Andrew's absence

Veszprémy listed those sources within the group, which refer to Peter, son of Töre as the assassin, mention Andrew departure to the Principality of Halych and Archbishop John's famous letter. Considering the latter as later insertions, Körmendi separated those texts where the prelate's role is appeared. # Annals of Salzburg (''Annales Salisburgenses''): its main corpus was written before 1216. It narrates that while Andrew led a campaign into Halych, the queen was murdered by Peter "as revenge for her sin". Peter himself, along with others, was captured and beheaded the next night. Its other text variant (compiled after 1222) contains John's letter, which is a subsequent insertion. # Continuation of Magnus von Reichersberg's Chronicle: the unidentified author took over the text from the Annals of Salzburg. Accordingly, during the king's absence, Peter and others assassinated the queen. He was executed together with his wife and others. # Annals ofHermann of Altach

Hermann of Altach (1200 or 1201 – 31 July 1275) was a medieval historian. He received his education at the Benedictine monastery of Niederaltaich, where he afterwards made his vows and was appointed custodian of the church. In this capacity he ...

(''Annales Hermanni''): Its author, the Abbot of Niederaltaich, used the text of the Annals of Salzburg. Hermann writes that Gertrude, "the mother of Saint Elizabeth", was assassinated by a certain ''ispán'' Peter, while the Hungarian king led a campaign against the Rus'. Peter and his accompanies were beheaded the next night. The text also contains the story of the letter of the bishop of Esztergom (''sic!

The Latin adverb ''sic'' (; "thus", "just as"; in full: , "thus was it written") inserted after a quoted word or passage indicates that the quoted matter has been transcribed or translated exactly as found in the source text, complete with any e ...

'').

# Chronicle of Osterhofen (''Chronicon Osterhoviense''): the chronicle from the Osterhofen Abbey

Osterhofen Abbey (german: Kloster Osterhofen, also called Altenmarkt Convent german: Altenmarkt- Damenstift) is a former monastery in Bavaria, Germany,

It is located in the Altenmarkt section of Osterhofen, a town to the south of the Danube betwe ...

(written around 1306) contains the same text as in Hermann of Altach's annals.

# Benedictine Annals of Augsburg (''Annales Sanctorum Udalrici et Afrae Augustenses''): compiled by the Benedictine monks of the St. Ulrich's and St. Afra's Abbey

St. Ulrich's and St. Afra's Abbey, Augsburg (german: Kloster Sankt Ulrich und Afra Augsburg) is a former Order of St. Benedict, Benedictine abbey dedicated to Ulrich of Augsburg, Saint Ulrich and Saint Afra in the south of the old city in Augsb ...

in Augsburg

Augsburg (; bar , Augschburg , links=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swabian_German , label=Swabian German, , ) is a city in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, around west of Bavarian capital Munich. It is a university town and regional seat of the ' ...

. It contains the same text as in Hermann of Altach's annals.

# Foundations of Monasteries in Bavaria (''Fundationes monasteriorum Bavariae''): the compilation contains the same text as in Hermann of Altach's annals, but with wrong year (1211). It also mentions the queen's death in an earlier entry, under the year 1200.

# Chronicle of the Anonymus of Leoben (''Chronicon Leobiense''): the unidentified author writes about the assassination twice, under the years 1213 and 1217 (the latter is just a four-word marginal note). It narrates that "the mother of Saint Elizabeth" was murdered by a noble, a certain "Peter of Várad", because the queen's brother Ekbert committed adultery with Peter's wife with Gertrude's knowledge. Subsequently, Béla, the queen's son confiscated Peter's castle and established a Cistercian abbey in its place. The manuscript also mentions "a bishop"'s letter. The untrustworthy text contaminates parallel oral traditions into a single text, but the information of the foundation of Bélakút Abbey is authentic.

Group C – ''Reginam occidere''

These sources only contain the alleged letter of John, Archbishop of Esztergom in connection with the assassination of Queen Gertrude. The story was later also included in a second-hand manuscript of the Annals of Salzburg and its derivative texts (see above). # The Latest Rhetoric (''Rhetorica novissima''): Boncompagno da Signa's rhetoric textbook, written before 1235, is the earliest work, which contains the story of the letter. Accordingly, King Andrew accused Archbishop John of participating in the murder before the Holy See. However Pope Innocent III, pointing out the correct use of commas, acquitted the archbishop from the charges. These references emphasize the letter's unintended ambiguity and, thus, John's approval of murder. Boncompagno resided in the papal court from 1229 to 1234, it is plausible he heard the story during his stay there.

#

# The Latest Rhetoric (''Rhetorica novissima''): Boncompagno da Signa's rhetoric textbook, written before 1235, is the earliest work, which contains the story of the letter. Accordingly, King Andrew accused Archbishop John of participating in the murder before the Holy See. However Pope Innocent III, pointing out the correct use of commas, acquitted the archbishop from the charges. These references emphasize the letter's unintended ambiguity and, thus, John's approval of murder. Boncompagno resided in the papal court from 1229 to 1234, it is plausible he heard the story during his stay there.

# Alberic of Trois-Fontaines

Alberic of Trois-Fontaines (french: Aubri or ''Aubry de Trois-Fontaines''; la, Albericus Trium Fontium) (died 1252) was a medieval Cistercian chronicler who wrote in Latin. He was a monk of Trois-Fontaines Abbey in the diocese of Châlons-sur-M ...

' Chronicle (''Chronica Albrici Monachi Trium Fontium''): the chronicler refers to the history of John's ambiguous letter as "well-known", as a result of which the archbishop was acquitted, "it is said". It is possible that Alberic used oral reports from Cistercian monks.

# Major Chronicle (''Chronica Majora''): it is possible that Matthew of Paris used Boncompagno's rhetoric textbook.

# The History of England (''Historia Anglorum''): Matthew of Paris' other work mentions that the assassins carried out the murder with the approval of the archbishop. The reinterpretation of the letter praises Pope Innocent's ingenuity.

Group D – Bánk's revenge

Those sources belong to this group, where Gertrude's alleged role of procuress in the adulterous affair between her brother and Bánk Bár-Kalán's wife appear. # Austrian Rhyming Chronicle (''Chronicon rhytmicum Austriacum''): it was written by a Hungarian-born cleric in Klosterneuburg Abbey around 1270. According to several German and Austrian historians (e.g.Wilhelm Wattenbach

Wilhelm Wattenbach (22 September 181920 September 1897), was a German historian.

He was born at Rantzau in Holstein. He studied philology at the universities of Bonn, Göttingen and Berlin, and in 1843 he began to work upon the ''Monumenta G ...

and Karl Uhlirz

Karl Uhlirz (13 June 1854, in Vienna – 22 March 1914, in Graz) was an Austrian historian and archivist.

He studied history at the University of Vienna, and from 1877 worked as an employee of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica (diplomatics e ...

), the author used only verbal or oral notifications, while Ernst Klebel argued the Annals of Heiligenkreuz Heiligenkreuz, which means 'Holy Cross' in German, may refer to:

In Austria:

*Heiligenkreuz, Lower Austria, a municipality in Lower Austria

**Heiligenkreuz Abbey in this municipality

*Heiligenkreuz im Lafnitztal, a municipality in Burgenland

*Heil ...

was available to the chronicler. Gerlinde Möser-Mersky considered the author used the lost annals of the Schottenstift

The Schottenstift ( en, Scottish Abbey), formally called Benediktinerabtei unserer Lieben Frau zu den Schotten ( en, Benedictine Abbey of Our Dear Lady of the Scots), is a Catholic Church, Catholic monastery founded in Vienna in 1155 when Henry I ...

in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

. According to Gyula Pauler, the Hungarian cleric witnessed the fall of Bánk Bár-Kalán and the subsequent political purges after Béla IV ascended the Hungarian throne in 1235, and connected these with the retaliation for the assassination of Queen Gertrude. Körmendi considered the author maybe used the mid-13th-century edition of the Hungarian chronicle composition. The Austrian Rhyming Chronicle is the earliest known work, where the Bánk story is appeared: Berthold persuaded the queen, his sister, to help him seduce the wife of Bánk. Gertrude was initially hesitant but, eventually, assisted her brother. In retaliation, Bánk and his confidants conspired against the queen, beheading her at a "field tent". The assassins were held accountable only after Béla was crowned.

# Annals of the Dominicans of Vienna (''Annales Praedicatorum Vindobonensium''): the first work (late 13th century), which provides the exact date of the assassination. Accordingly, Gertrude was murdered in a "field tent" on 28 September, because she helped her brother, the Patriarch of Aquileia

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate (bishop), primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholicism, Independent Catholic Chur ...

(anachronism) to seduce the wife of Bánk, also called Prenger. Körmendi argued the manuscript used the text of the Austrian Rhyming Chronicle, in addition to necrologies.

# World Chronicle (''Weltchronik''): the Austrian chronicler Jans der Enikel

Jans der Enikel (), or Jans der Jansen Enikel (), was a Viennese chronicler and narrative poet of the late 13th century.

He wrote a ''Weltchronik'' () and a ''Fürstenbuch'' (, a history of Vienna), both in Middle High German verse.

Name and ...

(late 13th century) compiled a completely unreliable report in the second appendix of his Middle High German

Middle High German (MHG; german: Mittelhochdeutsch (Mhd.)) is the term for the form of German spoken in the High Middle Ages. It is conventionally dated between 1050 and 1350, developing from Old High German and into Early New High German. High ...

-language universal chronicle

A universal history is a work aiming at the presentation of a history of all of mankind as a whole, coherent unit. A universal chronicle or world chronicle typically traces history from the beginning of written information about the past up to t ...

; following the death of King Stephen (''sic!''), he left behind a widow Gertrude and an heir Béla. The powerful Prangaer family sought to get power over Hungary. Despite their invitation, the bishop of Győr

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

refused to join their cause and clearly warned the conspirators against attempting to assassinate the queen. Despite that, Gertrude was attacked and beheaded, while the child Béla was assaulted but survived. Thereafter, after growing up, Béla ordered to massacre the entire Prangaer kinship. Because of the family name, Gerlinde Möser-Mersky assumed a philological connection between Jans der Enikel's chronicle and the Annals of the Dominicans of Vienna. Körmendi argued both works used a same, now lost source.

# Illuminated Chronicle

The ''Chronicon Pictum'' (Latin for "illustrated chronicle", English: ''Illuminated Chronicle'' or ''Vienna Illuminated Chronicle'', hu, Képes Krónika, sk, Obrázková kronika, german: Illustrierte Chronik, also referred to as ''Chronica Hung ...

(''Chronicon Pictum''): also known as the 14th-century Hungarian chronicle composition, the only medieval chronicle in Hungary (compiled in the 1350s) from the pre-Renaissance era, which narrates the assassination of Queen Gertrude. It incorrectly dates the event to the year 1212. According to Körmendi, the (original) author utilized the narration of the Austrian Rhyming Chronicle, or vica versa. Later, the text of the Illuminated Chronicle was utilized by subsequent Hungarian chronicles and Henry of Mügeln

Henry may refer to:

People

* Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portuga ...

's ''Ungarnchronik''.

# Austrian Chronicle (''Chronicon Austriae''): Thomas Ebendorfer compiled his work between 1449 and 1452. The author incorrectly connected the events of assassination to King Andrew's departure for his participation in the Fifth Crusade in 1217–1218. It also claims that Gertrude was the daughter of the duke of Moravia. According to the historian, Leopold VI was present during the skirmish. Ebendorfer utilized the text of the Illuminated Chronicle supplementing with the narration of the Annals of Admont.

Group D/2 – Gertrude's innocence