Asplenium Montanum on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Asplenium montanum'', commonly known as the mountain spleenwort, is a small fern endemic to the eastern United States. It is found primarily in the

On fertile fronds, from 1 to 15 elliptical or narrow sori can be found on the underside of each pinna. They are 0.5 to 1.5 millimeters long, covered by translucent, pale tan

On fertile fronds, from 1 to 15 elliptical or narrow sori can be found on the underside of each pinna. They are 0.5 to 1.5 millimeters long, covered by translucent, pale tan

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

from Vermont

Vermont () is a state in the northeast New England region of the United States. Vermont is bordered by the states of Massachusetts to the south, New Hampshire to the east, and New York to the west, and the Canadian province of Quebec to ...

to Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, with a few isolated populations in the Ozarks

The Ozarks, also known as the Ozark Mountains, Ozark Highlands or Ozark Plateau, is a physiographic region in the U.S. states of Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma and the extreme southeastern corner of Kansas. The Ozarks cover a significant port ...

and in the Ohio Valley

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illinoi ...

. It grows in small crevices in sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates) ...

cliffs with highly acid soil, where it is usually the only vascular plant

Vascular plants (), also called tracheophytes () or collectively Tracheophyta (), form a large group of land plants ( accepted known species) that have lignified tissues (the xylem) for conducting water and minerals throughout the plant. They al ...

occupying that ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for ...

. It can be recognized by its tufts of dark blue-green, highly divided leaves. The species was first described in 1810 by the botanist Carl Ludwig Willdenow

Carl Ludwig Willdenow (22 August 1765 – 10 July 1812) was a German botanist, pharmacist, and plant taxonomist. He is considered one of the founders of phytogeography, the study of the geographic distribution of plants. Willdenow was als ...

. No subspecies have been described, although a discolored and highly dissected form

Form is the shape, visual appearance, or configuration of an object. In a wider sense, the form is the way something happens.

Form also refers to:

*Form (document), a document (printed or electronic) with spaces in which to write or enter data

...

was reported from the Shawangunk Mountains Shawangunk ( ) may refer to:

In New York

*Shawangunk, New York, a town in Ulster County

*Shawangunk Correctional Facility, in Ulster County

*Shawangunk Grasslands National Wildlife Refuge, in Ulster County

*Shawangunk Kill, a tributary of the Wallk ...

in 1974. ''Asplenium montanum'' is a diploid member of the "Appalachian ''Asplenium'' complex," a group of spleenwort species and hybrids which have formed by reticulate evolution

Reticulate evolution, or network evolution is the origination of a lineage through the partial merging of two ancestor lineages, leading to relationships better described by a phylogenetic network than a bifurcating tree. Reticulate patterns ca ...

. Members of the complex descended from ''A. montanum'' are among the few other vascular plants that can tolerate its typical habitat.

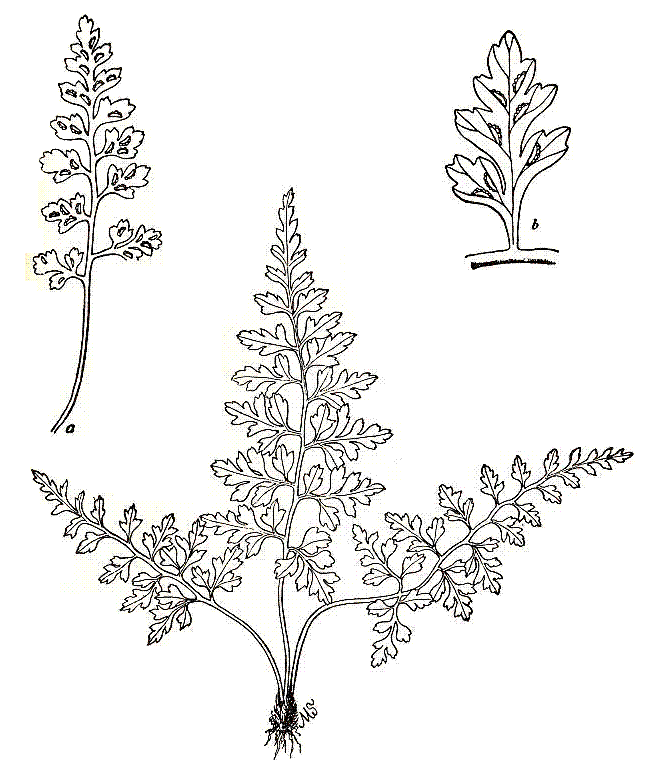

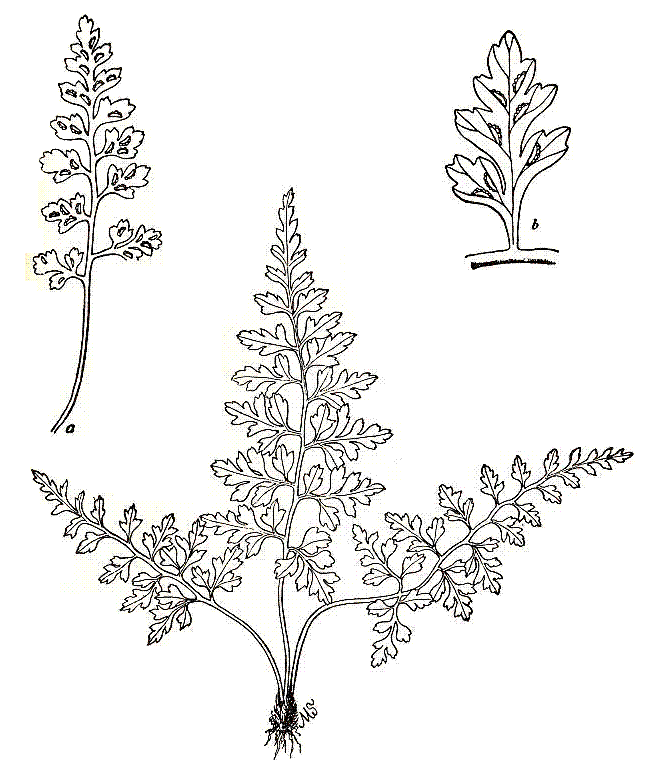

Description

''Asplenium montanum'' is a small,evergreen

In botany, an evergreen is a plant which has foliage that remains green and functional through more than one growing season. This also pertains to plants that retain their foliage only in warm climates, and contrasts with deciduous plants, which ...

fern which grows in tufts. The leaves are bluish-green and highly divided, proceeding from a long and often drooping stalk. ''A. montanum'' is monomorphic, with no difference in form between sterile and fertile fronds.

The horizontal rhizome

In botany and dendrology, a rhizome (; , ) is a modified subterranean plant stem that sends out roots and shoots from its nodes. Rhizomes are also called creeping rootstalks or just rootstalks. Rhizomes develop from axillary buds and grow hori ...

s, which are about 1 millimeter across, may curve upward. They are not branched, but as new plants can form at root tips, a tightly packed cluster of stems may give the appearance of branching. The rhizomes are covered in dark brown, narrowly triangular scales, from long and from 0.2 to 0.4 millimeters across, with untoothed edges. They are strongly clathrate (bearing a lattice-like pattern).

The stipe (the stalk of the leaf, below the blade) is dark brown to purplish-black and shiny at the base, gradually turning dull green as it ascends to the leaf blade. The stipe is from long, and may be from 0.5 to 1.5 times the length of the blade. Dark, narrowly lance-shaped scales and tiny hairs are present only at the very base of the stipe, which is slender and fragile, and lacks wings.

The leaf blade is thick and hairless, and of a dark blue-green color; the rachis

In biology, a rachis (from the grc, ῥάχις [], "backbone, spine") is a main axis or "shaft".

In zoology and microbiology

In vertebrates, ''rachis'' can refer to the series of articulated vertebrae, which encase the spinal cord. In this c ...

(leaf axis), like the stipe, is a dull green, with occasional hairs. The blade is triangular or lance-shaped, with a squared-off or slightly rounded base and a pointed tip. It ranges from long and from wide, occasionally as wide as . The blade varies from pinnate-pinnatifid to bipinnate-pinnatifid; that is, it is cut into lobed pinnae, and sometimes the pinnae themselves are cut into lobed pinnules. There are four to ten pairs of widely spaced pinnae per leaf, each of which is triangular to lance-shaped, with coarse incisions in the edges, which cut them into pinnules or deep lobes, and a rounded to angled base. The pinnules are indented, but not further cut. The longest pinnae are those nearest the base of the leaf, which range from long and from across. The veins in the leaf do not form a meshwork, and are obscure.

indusia

A sorus (pl. sori) is a cluster of sporangia (structures producing and containing spores) in ferns and fungi. A coenosorus (plural coenosori) is a compound sorus composed of multiple, fused sori.

Etymology

This New Latin word is from Ancient Gr ...

with somewhat jagged edges. Each sporangium

A sporangium (; from Late Latin, ) is an enclosure in which spores are formed. It can be composed of a single cell or can be multicellular. Virtually all plants, fungi, and many other lineages form sporangia at some point in their life cy ...

holds 64 spore

In biology, a spore is a unit of sexual or asexual reproduction that may be adapted for dispersal and for survival, often for extended periods of time, in unfavourable conditions. Spores form part of the life cycles of many plants, algae, f ...

s. The species has a chromosome number of 2''n'' = 72 in the sporophyte

A sporophyte () is the diploid multicellular stage in the life cycle of a plant or alga which produces asexual spores. This stage alternates with a multicellular haploid gametophyte phase.

Life cycle

The sporophyte develops from the zygote pr ...

; it is a diploid.

Identification

The dark bluish-green color and the widely spaced, deeply cut and indented pinnae differentiate ''A. montanum'' from most related species. The pinnae of Bradley's spleenwort ( ''A. bradleyi'') are toothed and less deeply cut, and the dark color of the stipe continues partway up the rachis in that species. Wall-rue ( ''A. ruta-muraria'') has a green stipe, and its pinnae have longer stalks and are broadest near the tip. Wherry's spleenwort ( ''A. × wherryi''), a hybrid between Bradley's spleenwort and mountain spleenwort, is intermediate between its parents. When compared with mountain spleenwort, the blade of Wherry's spleenwort is lance-shaped, rather than triangular; the upper parts of the blade are not as deeply cut; and the dark color of the stipe extends to the beginning of the rachis.Taxonomy

This fern was at first identified byAndré Michaux

André Michaux, also styled Andrew Michaud, (8 March 174611 October 1802) was a French botanist and explorer. He is most noted for his study of North American flora. In addition Michaux collected specimens in England, Spain, France, and even Per ...

, in 1803, as black spleenwort (''Asplenium adiantum-nigrum

''Asplenium adiantum-nigrum'' is a common species of fern known by the common name black spleenwort. It is found mostly in Africa, Europe, and Eurasia, but is also native to a few locales in Mexico and the United States.

Description

This splee ...

''). Carl Ludwig Willdenow

Carl Ludwig Willdenow (22 August 1765 – 10 July 1812) was a German botanist, pharmacist, and plant taxonomist. He is considered one of the founders of phytogeography, the study of the geographic distribution of plants. Willdenow was als ...

recognized and described it as a separate species, which he named ''Asplenium montanum'', in 1810. In 1901, John A. Shafer attempted to transfer it to the genus ''Athyrium

''Athyrium'' (lady-fern) is a genus of about 180 species of terrestrial ferns, with a cosmopolitan distribution. It is placed in the family Athyriaceae, in the order Polypodiales.

Its genus name is from Greek '' a-'' ('without') and Latinized G ...

'' as ''Athyrium montanum'', but this name is illegitimate as a later homonym

In linguistics, homonyms are words which are homographs (words that share the same spelling, regardless of pronunciation), or homophones (equivocal words, that share the same pronunciation, regardless of spelling), or both. Using this definition, ...

of ''Athyrium montanum'' (Lam.) Röhl. ex Spreng. The species was segregated from ''Asplenium

''Asplenium'' is a genus of about 700 species of ferns, often treated as the only genus in the family Aspleniaceae, though other authors consider ''Hymenasplenium'' separate, based on molecular phylogenetic analysis of DNA sequences, a different ...

'' as ''Chamaefilix montana'' by Oliver Atkins Farwell

Oliver Atkins Farwell (13 December 1867, Dorchester, Boston

Dorchester (colloquially referred to as Dot) is a Boston neighborhood comprising more than in the City of Boston, Massachusetts, United States. Originally, Dorchester was a separate tow ...

in 1931. The change was not widely accepted and current authorities do not recognize this segregate genus.

A global phylogeny of ''Asplenium'' published in 2020 divided the genus into eleven clades, which were given informal names pending further taxonomic study. ''A. montanum'' belongs to the "''Onopteris'' subclade" of the "''Pleurosorus'' clade". The ''Pleurosorus'' clade has a worldwide distribution; members are generally small and occur on hillsides, often sheltering among rocks in exposed habitats. The ''Onopteris'' subclade has ''Aspidium''-type gametophyte

A gametophyte () is one of the two alternation of generations, alternating multicellular organism, multicellular phases in the life cycles of plants and algae. It is a haploid multicellular organism that develops from a haploid spore that has on ...

s. The closest relatives of ''A. montanum'' within the subclade are '' A. onopteris'' and its allopolyploid descendant, ''A. adiantum-nigrum''.

Varieties

In 1974, Timothy Reeves described an unusual population of ''A. montanum'' from theShawangunk Mountains Shawangunk ( ) may refer to:

In New York

*Shawangunk, New York, a town in Ulster County

*Shawangunk Correctional Facility, in Ulster County

*Shawangunk Grasslands National Wildlife Refuge, in Ulster County

*Shawangunk Kill, a tributary of the Wallk ...

. Having used chromatography

In chemical analysis, chromatography is a laboratory technique for the separation of a mixture into its components. The mixture is dissolved in a fluid solvent (gas or liquid) called the ''mobile phase'', which carries it through a system (a ...

to show that it was not a hybrid

Hybrid may refer to:

Science

* Hybrid (biology), an offspring resulting from cross-breeding

** Hybrid grape, grape varieties produced by cross-breeding two ''Vitis'' species

** Hybridity, the property of a hybrid plant which is a union of two dif ...

, he interpreted it as a new form, ''Asplenium montanum'' forma ''shawangunkense''. In this form, as contrasted with the usual forma ''montanum'', the leaf blade is yellow-green, the fronds continue highly dissected to the apex and do not come to a pointed tip, the fronds are shorter and more highly dissected than usual, and all fronds are sterile.

Hybrids

''Asplenium montanum'' readily forms hybrids with a number of other species in the "Appalachian ''Asplenium'' complex". In 1925,Edgar T. Wherry

Edgar Theodore Wherry (1885–1982) was an American mineralogist, soil scientist and botanist. He had a deep interest in ferns and ''Sarracenia''.

Wherry earned his bachelor's degree in chemistry in 1906 from the University of Pennsylvania. He r ...

noted the similarities between ''A. montanum'', lobed spleenwort ( ''A. pinnatifidum''), and Trudell's spleenwort ( ''A. × trudellii''), and in 1936 concluded that Trudell's spleenwort was a hybrid between the first two. In 1951, Herb Wagner, while reviewing Irene Manton

Irene Manton, FRS FLS (born Irène Manton; 17 April 1904, in Kensington – 13 May 1988) was a British botanist who was Professor of Botany at the University of Leeds. She was noted for study of ferns and algae.

Biography

Irene Manton was th ...

's ''Problems of Cytology and Evolution in the Pteridophyta'', suggested in passing that ''A. pinnatifidum'' itself might represent a hybrid between ''A. montanum'' and the American walking fern, ''Camptosorus rhizophyllus'' (now ''A. rhizophyllum'').

In 1953, he reported preliminary cytological studies on the ''Asplenium''s and suggested that ''A. montanum'' had crossed with ebony spleenwort ( ''A. platyneuron'') to yield Bradley's spleenwort ( ''A. bradleyi''), noting that D. C. Eaton and W. N. Clute had already made tentative suggestions along those lines. He also made chromosome counts of ''A. × trudellii'', which had been classified by some simply as a variety of ''A. pinnatifidum''. As ''A. pinnatifidum'' proved to be a tetraploid

Polyploidy is a condition in which the cells of an organism have more than one pair of ( homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have nuclei (eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes, where each set contains ...

while ''A. montanum'' was a diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

, a hybrid between them would be a triploid

Polyploidy is a condition in which the cells of an organism have more than one pair of ( homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have nuclei ( eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes, where each set contain ...

, and Wagner showed that this was in fact the case for ''A. × trudellii''. His further experiments, published the following year, strongly suggested that both ''A. bradleyi'' and ''A. pinnatifidum'' were allotetraploid

Polyploidy is a condition in which the cells of an organism have more than one pair of ( homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have nuclei (eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes, where each set contains ...

s, the product of hybridization between ''A. montanum'' and another ''Asplenium'' to form a sterile diploid, followed by chromosome doubling that restored fertility.

These cytotaxonomic findings were supported by subsequent chromatographic

In chemical analysis, chromatography is a laboratory technique for the separation of a mixture into its components. The mixture is dissolved in a fluid solvent (gas or liquid) called the ''mobile phase'', which carries it through a system (a ...

studies. ''A. montanum'' was shown to produce a pattern of seven substances chromatographically distinct from those produced by the other diploid members of the Appalachian ''Asplenium'' complex. These substances were present in the chromatograms of all tested hybrids believed to descend from ''A. montanum'' at one or more removes: ''A. bradleyi'', ''A. × gravesii'', ''A. × kentuckiense'', ''A. pinnatifidum'', ''A. × trudellii'', and ''A. × wherryi''. Four of the compounds present in the chromatograms of ''A. montanum'' and its descendants, fluorescing

Fluorescence is the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. It is a form of luminescence. In most cases, the emitted light has a longer wavelength, and therefore a lower photon energy, tha ...

gold-orange under ultraviolet light

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation i ...

, were subsequently identified as the xanthonoids

A xanthonoid is a chemical natural phenolic compound formed from the xanthone backbone. Many members of the Clusiaceae contain xanthonoids.

Xanthonoid biosynthesis in cell cultures of ''Hypericum androsaemum'' involves the presence of a benzophe ...

mangiferin

Mangiferin is a glucosylxanthone (xanthonoid). This molecule is a glucoside of norathyriol.

Natural occurrences

Mangiferin was first isolated from the leaves and bark of ''Mangifera indica'' (the mango tree). It can also be extracted from ...

, isomangiferin, and their ''O''-glucoside

A glucoside is a glycoside that is derived from glucose. Glucosides are common in plants, but rare in animals. Glucose is produced when a glucoside is hydrolysed by purely chemical means, or decomposed by fermentation or enzymes.

The name was o ...

s. The other two were identified as kaempferol

Kaempferol (3,4′,5,7-tetrahydroxyflavone) is a natural flavonol, a type of flavonoid, found in a variety of plants and plant-derived foods including kale, beans, tea, spinach, and broccoli. Kaempferol is a yellow crystalline solid with a meltin ...

derivatives, but could not be more precisely determined due to lack of material; the last was a trace compound which could not be studied. A chloroplast phylogeny has suggested that ''A. montanum'' is the maternal ancestor of ''A. bradleyi''.

The allotetraploid hybrid species derived from ''A. montanum'' can backcross

Backcrossing is a crossing of a hybrid with one of its parents or an individual genetically similar to its parent, to achieve offspring with a genetic identity closer to that of the parent. It is used in horticulture, animal breeding, and product ...

with ''A. montanum'' to form triploid hybrids. The backcross hybrid between ''A. montanum'' and ''A. pinnatifidum'' is ''A. × trudellii'', as suggested by Wherry. He also collected specimens of the backcross hybrid between ''A. montanum'' and ''A. bradleyi'' from a cliff near Blairstown, New Jersey

Blairstown is a township in Warren County, New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, Blairstown's population was 5,704. As of the 2010 United States Census, the township's population was 5,967''A. × wherryi''). The sterile diploid ''A. montanum × platyneuron'', precursor to ''A. bradleyi'', was collected in 1972 at

One of the "Appalachian spleenworts", ''A. montanum'' is found in the

One of the "Appalachian spleenworts", ''A. montanum'' is found in the

Crowder's Mountain

Crowders Mountain is one of two main peaks within Crowders Mountain State Park, the other peak being The Pinnacle. The park is located in the western Piedmont of North Carolina between the cities of Kings Mountain and Gastonia or about west ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

; ''A. montanum × rhizophyllum'', precursor to ''A. pinnatifidum'', has never been found.

Distribution and habitat

One of the "Appalachian spleenworts", ''A. montanum'' is found in the

One of the "Appalachian spleenworts", ''A. montanum'' is found in the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

from Vermont and Massachusetts southwestward to Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia, and to a lesser extent in the Ohio Valley

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illinoi ...

in Ohio, Indiana, and Kentucky. Arkansas populations were discovered in Garland County and Stone County in 2002 and 2008, respectively. One outlying population in Missouri, collected in 1960, is considered historical; it is represented by one specimen collected near Graham Cave and has never been relocated. The site is thought to have been destroyed by road construction. A collection by Farwell from the Keweenaw Peninsula

The Keweenaw Peninsula ( , sometimes locally ) is the northernmost part of Michigan's Upper Peninsula. It projects into Lake Superior and was the site of the first copper boom in the United States, leading to its moniker of "Copper Country." As o ...

of Michigan was considered valid by M. L. Fernald, but is of questionable authenticity; the population has never been relocated.

''Asplenium montanum'' grows on acidic rocks such as sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates) ...

, in crevices into which moisture seeps from within the rock strata. It has been found at altitudes up to . Like the closely related ''A. bradleyi'', ''A. montanum'' requires that the thin soil in its favored crevices be subacid ( pH 4.5–5.0) to (pH 3.5–4.0), and it is intolerant of calcium

Calcium is a chemical element with the symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to ...

. This habitat is unfavorable to most other plants, but its allotetraploid descendants and their backcross hybrids may occur alongside it.

Ecology and conservation

''Asplenium montanum'' is globally secure, but threatened at the edges of its range. It is known only historically from Missouri, andNatureServe

NatureServe, Inc. is a non-profit organization based in Arlington County, Virginia, US, that provides proprietary wildlife conservation-related data, tools, and services to private and government clients, partner organizations, and the public. Nat ...

considers it critically imperiled in Indiana, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont, imperiled in New Jersey, and imperiled to vulnerable in Connecticut and New York. The principal threat to New York populations is rock climbing

Rock climbing is a sport in which participants climb up, across, or down natural rock formations. The goal is to reach the summit of a formation or the endpoint of a usually pre-defined route without falling. Rock climbing is a physically and ...

.

Cultivation

''Asplenium montanum'' may be cultivated outdoors or in aterrarium

A terrarium (plural: terraria or terrariums) is usually a sealable glass container containing soil and plants that can be opened for maintenance to access the plants inside; however, terraria can also be open to the atmosphere. Terraria are ofte ...

. In either case, the soil used should be amended with chips of acidic rock.

Notes and references

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

{{Taxonbar, from=Q4808134 montanum Ferns of the United States Flora of the Appalachian Mountains Flora of the Northeastern United States Flora of the Southeastern United States Ferns of the Americas Plants described in 1810 Taxa named by Carl Ludwig Willdenow