Ashqaluna on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ashkelon or Ashqelon (;

The

The  The main finds were enormous quantities of around 100,000 animal bones and around 20,000

The main finds were enormous quantities of around 100,000 animal bones and around 20,000

The city was originally built on a

The city was originally built on a

Ashkelon was soon rebuilt. Until the conquest of

Ashkelon was soon rebuilt. Until the conquest of

151

/ref> In July 1950, the shrine was destroyed at the instructions of Moshe Dayan in accordance with a 1950s Israeli policy of erasing Muslim historical sites within Israel. Around 2000, a modest marble mosque was constructed on the site by Mohammed Burhanuddin, an Indian Islamic leader of the Dawoodi Bohras.

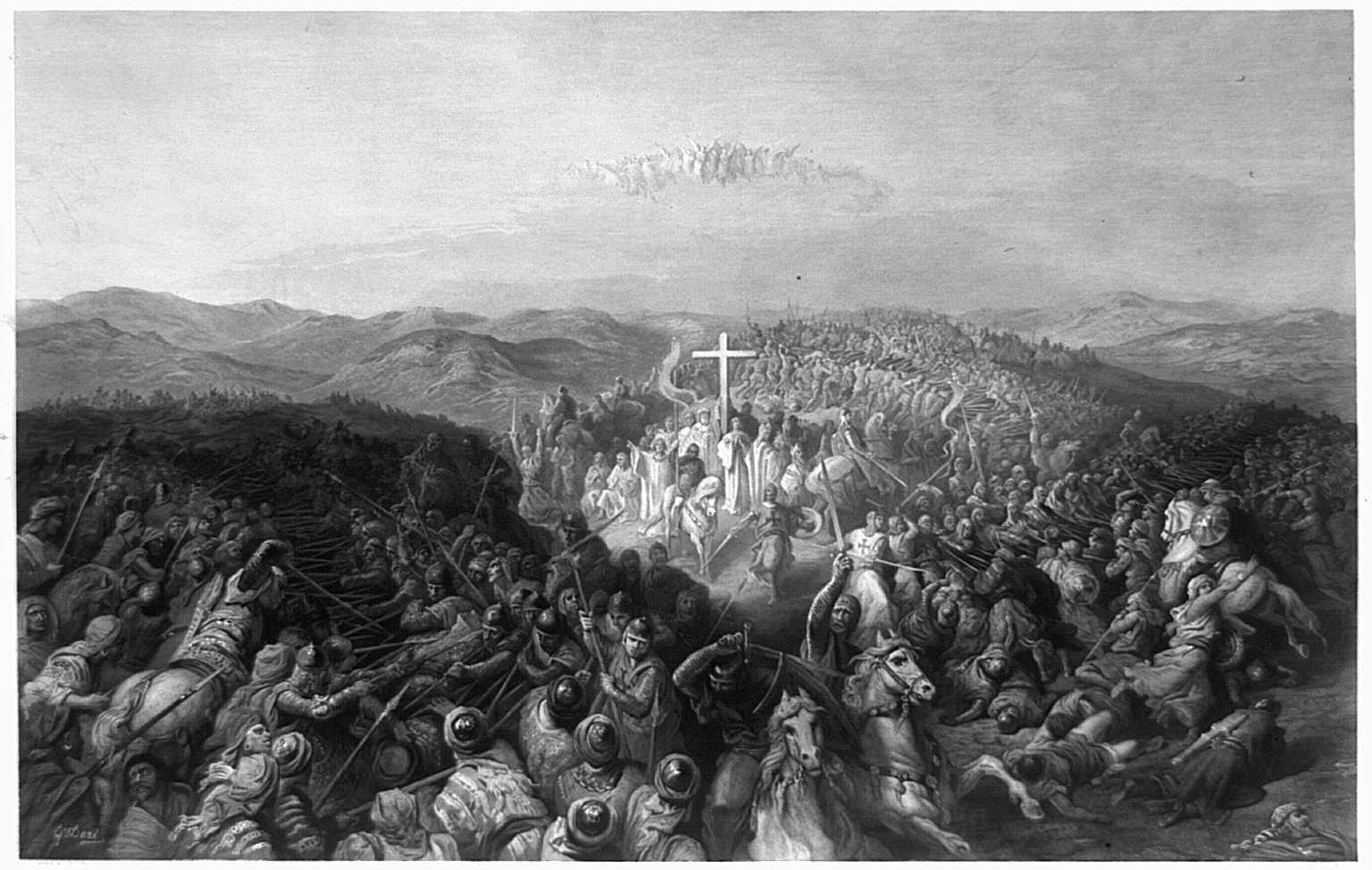

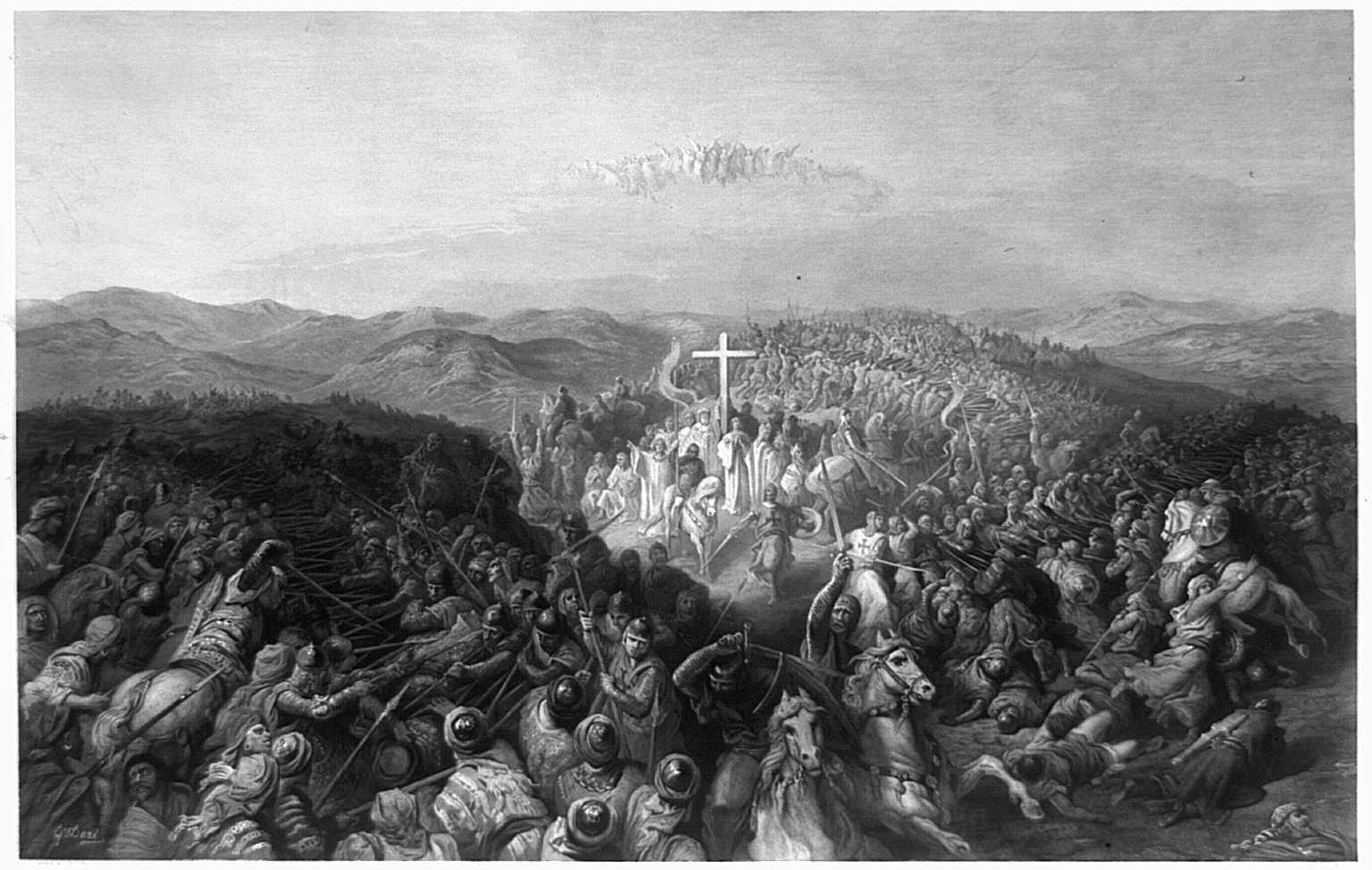

During the Crusades, Asqalan (known to the Crusaders as ''Ascalon'') was an important city due to its location near the coast and between the Crusader states, Crusader States and Egypt. In 1099, shortly after the Siege of Jerusalem (1099), Siege of Jerusalem, a Fatimid army that had been sent to relieve Jerusalem was defeated by a Crusader force at the Battle of Ascalon. The city itself was not captured by the Crusaders because of internal disputes among their leaders. This battle is widely considered to have signified the end of the First Crusade. As a result of military reinforcements from Egypt and a large influx of refugees from areas conquered by the Crusaders, Asqalan became a major Fatimid frontier post. The Fatimids utilized it to launch raids into the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Trade ultimately resumed between Asqalan and Crusader-controlled Jerusalem, though the inhabitants of Asqalan regularly struggled with shortages in food and supplies, necessitating the provision of goods and relief troops to the city from Egypt on several occasions each year. According to William of Tyre, the entire civilian population of the city was included in the Fatimid army registers. The Crusaders' capture of the port city of Tyre, Lebanon, Tyre in 1134 and their construction of a ring of fortresses around the city to neutralize its threat to Jerusalem strategically weakened Asqalan. In 1150 the Fatimids fortified the city with fifty-three towers, as it was their most important frontier fortress. Three years later, after a Siege of Ascalon, seven-month siege, the city was captured by a Crusader army led by King Baldwin III of Jerusalem. The Fatimids secured the head of Husayn from its mausoleum in the city and transported it to their capital Cairo. Ascalon was then added to the County of Jaffa and Ascalon, County of Jaffa to form the County of Jaffa and Ascalon, which became one of the four major seigneuries of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

After the Siege of Jerusalem (1099), Crusader conquest of Jerusalem the six elders of the Karaite Judaism, Karaite Jewish community in Ashkelon contributed to the ransoming of captured Jews and holy relics from Jerusalem's new rulers. The Letter of the Karaite elders of Ascalon, which was sent to the Jewish elders of Alexandria, describes their participation in the ransom effort and the ordeals suffered by many of the freed captives. A few hundred Jews, Karaites and Rabbanites, were living in Ashkelon in the second half of the 12th century, but moved to Jerusalem when the city was destroyed in 1191.

In 1187, Saladin took Ashkelon as part of his conquest of the Crusader states, Crusader States following the Battle of Hattin. In 1191, during the Third Crusade, Saladin demolished the city because of its potential strategic importance to the Christians, but the leader of the Crusade, King Richard I of England, constructed a citadel upon the ruins. Ashkelon subsequently remained part of the diminished territories of Outremer throughout most of the 13th century and Richard, Earl of Cornwall reconstructed and refortified the citadel during 1240–41, as part of the Crusader policy of improving the defences of coastal sites. The Egyptians retook Ashkelon in 1247 during As-Salih Ayyub's conflict with the Crusader States and the city was returned to Muslim rule. The Mamluk dynasty came into power in Egypt in 1250 and the ancient and Middle Ages, medieval history of Ashkelon was brought to an end in 1270, when the Mamluk sultan Baybars ordered the citadel and harbour at the site to be destroyed. As a result of this destruction, the site was abandoned by its inhabitants and fell into disuse.

During the Crusades, Asqalan (known to the Crusaders as ''Ascalon'') was an important city due to its location near the coast and between the Crusader states, Crusader States and Egypt. In 1099, shortly after the Siege of Jerusalem (1099), Siege of Jerusalem, a Fatimid army that had been sent to relieve Jerusalem was defeated by a Crusader force at the Battle of Ascalon. The city itself was not captured by the Crusaders because of internal disputes among their leaders. This battle is widely considered to have signified the end of the First Crusade. As a result of military reinforcements from Egypt and a large influx of refugees from areas conquered by the Crusaders, Asqalan became a major Fatimid frontier post. The Fatimids utilized it to launch raids into the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Trade ultimately resumed between Asqalan and Crusader-controlled Jerusalem, though the inhabitants of Asqalan regularly struggled with shortages in food and supplies, necessitating the provision of goods and relief troops to the city from Egypt on several occasions each year. According to William of Tyre, the entire civilian population of the city was included in the Fatimid army registers. The Crusaders' capture of the port city of Tyre, Lebanon, Tyre in 1134 and their construction of a ring of fortresses around the city to neutralize its threat to Jerusalem strategically weakened Asqalan. In 1150 the Fatimids fortified the city with fifty-three towers, as it was their most important frontier fortress. Three years later, after a Siege of Ascalon, seven-month siege, the city was captured by a Crusader army led by King Baldwin III of Jerusalem. The Fatimids secured the head of Husayn from its mausoleum in the city and transported it to their capital Cairo. Ascalon was then added to the County of Jaffa and Ascalon, County of Jaffa to form the County of Jaffa and Ascalon, which became one of the four major seigneuries of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

After the Siege of Jerusalem (1099), Crusader conquest of Jerusalem the six elders of the Karaite Judaism, Karaite Jewish community in Ashkelon contributed to the ransoming of captured Jews and holy relics from Jerusalem's new rulers. The Letter of the Karaite elders of Ascalon, which was sent to the Jewish elders of Alexandria, describes their participation in the ransom effort and the ordeals suffered by many of the freed captives. A few hundred Jews, Karaites and Rabbanites, were living in Ashkelon in the second half of the 12th century, but moved to Jerusalem when the city was destroyed in 1191.

In 1187, Saladin took Ashkelon as part of his conquest of the Crusader states, Crusader States following the Battle of Hattin. In 1191, during the Third Crusade, Saladin demolished the city because of its potential strategic importance to the Christians, but the leader of the Crusade, King Richard I of England, constructed a citadel upon the ruins. Ashkelon subsequently remained part of the diminished territories of Outremer throughout most of the 13th century and Richard, Earl of Cornwall reconstructed and refortified the citadel during 1240–41, as part of the Crusader policy of improving the defences of coastal sites. The Egyptians retook Ashkelon in 1247 during As-Salih Ayyub's conflict with the Crusader States and the city was returned to Muslim rule. The Mamluk dynasty came into power in Egypt in 1250 and the ancient and Middle Ages, medieval history of Ashkelon was brought to an end in 1270, when the Mamluk sultan Baybars ordered the citadel and harbour at the site to be destroyed. As a result of this destruction, the site was abandoned by its inhabitants and fell into disuse.

In the 1922 census of Palestine, ''Majdal'' had a population of 5,064; 33 Christians and 5,031 Muslims,Barron, 1923, Table V, Sub-district of Gaza, p

In the 1922 census of Palestine, ''Majdal'' had a population of 5,064; 33 Christians and 5,031 Muslims,Barron, 1923, Table V, Sub-district of Gaza, p

8

/ref> increasing in the 1931 census of Palestine, 1931 census to 6,166 Muslims and 41 Christians.Palestine Office of Statistics, Vital Statistical Tables 1922–1945, Table A8. In the Village Statistics, 1945, 1945 statistics Majdal had a population of 9,910; ninety Christians and 9,820 Muslims,Department of Statistics, 1945, p

32

/ref> with a total (urban and rural) of 43,680 dunams of land, according to an official land and population survey. Two thousand two hundred and fifty dunes were public land; all the rest was owned by Arabs.Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. ''Village Statistics, April, 1945.'' Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p

46

/ref> of the dunams, 2,337 were used for citrus and bananas, 2,886 were plantations and irrigable land, 35,442 for cereals, while 1,346 were built-up land. Majdal was especially known for its weaving industry. The town had around 500 looms in 1909. In 1920 a British Government report estimated that there were 550 cotton looms in the town with an annual output worth 30–40 million French franc, francs. But the industry suffered from imports from Europe and by 1927 only 119 weaving establishments remained. The three major fabrics produced were "malak" (silk), 'ikhdari' (bands of red and green) and 'jiljileh' (dark red bands). These were used for festival dresses throughout Southern Palestine. Many other fabrics were produced, some with poetic names such as ''ji'nneh u nar'' ("heaven and hell"), ''nasheq rohoh'' ("breath of the soul") and ''abu mitayn'' ("father of two hundred").

During the 1948 war, the Egyptian army occupied a large part of the Gaza region including Majdal. Over the next few months, the town was subjected to Israeli air-raids and shelling. All but about 1,000 of the town's residents were forced to leave by the time it was captured by Israeli forces as a sequel to Operation Yoav on 4 November 1948. General Yigal Allon ordered the expulsion of the remaining Palestinians but the local commanders did not do so and the Arab population soon recovered to more than 2,500 due mostly to refugees slipping back and also due to the transfer of Palestinians from nearby villages. Most of them were elderly, women, or children. During the next year or so, the Palestinians were held in a confined area surrounded by barbed wire, which became commonly known as the "ghetto".Morris, 2004, pp

During the 1948 war, the Egyptian army occupied a large part of the Gaza region including Majdal. Over the next few months, the town was subjected to Israeli air-raids and shelling. All but about 1,000 of the town's residents were forced to leave by the time it was captured by Israeli forces as a sequel to Operation Yoav on 4 November 1948. General Yigal Allon ordered the expulsion of the remaining Palestinians but the local commanders did not do so and the Arab population soon recovered to more than 2,500 due mostly to refugees slipping back and also due to the transfer of Palestinians from nearby villages. Most of them were elderly, women, or children. During the next year or so, the Palestinians were held in a confined area surrounded by barbed wire, which became commonly known as the "ghetto".Morris, 2004, pp

528

–529. Moshe Dayan and Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion were in favor of expulsion, while Mapam and the Israeli labor union Histadrut objected. The government offered the Palestinians positive inducements to leave, including a favorable currency exchange, but also caused panic through night-time raids. The first group was deported to the

In 1949 and 1950, three immigrant transit camps (ma'abarot) were established alongside Majdal (renamed Migdal) for Jewish refugees from Arab world, Arab countries, Romania and Poland. Northwest of Migdal and the immigrant camps, on the lands of the depopulated Palestinian people, Palestinian village al-Jura, entrepreneur Zvi Segal, one of the signatories of Israel's Declaration of Independence, established the upscale Barnea neighborhood.

A large tract of land south of Barnea was handed over to the trusteeship of the South African Zionist Federation, which established the neighborhood of Afridar. Plans for the city were drawn up in South Africa according to the Garden city movement, garden city model. Migdal was surrounded by a broad ring of orchards. Barnea developed slowly, but Afridar grew rapidly. The first homes, built in 1951, were inhabited by new Jewish immigrants from South Africa and South America, with some native-born Israelis. The first public housing project for residents of the transit camps, the Southern Hills Project (Hageva'ot Hadromiyot) or Zion Hill (Givat Zion), was built in 1952.

Under a plan signed in October 2015, seven new neighborhoods comprising 32,000 housing units, a new stretch of highway, and three new highway interchanges will be built, turning Ashkelon into the sixth-largest city in Israel.

In 1949 and 1950, three immigrant transit camps (ma'abarot) were established alongside Majdal (renamed Migdal) for Jewish refugees from Arab world, Arab countries, Romania and Poland. Northwest of Migdal and the immigrant camps, on the lands of the depopulated Palestinian people, Palestinian village al-Jura, entrepreneur Zvi Segal, one of the signatories of Israel's Declaration of Independence, established the upscale Barnea neighborhood.

A large tract of land south of Barnea was handed over to the trusteeship of the South African Zionist Federation, which established the neighborhood of Afridar. Plans for the city were drawn up in South Africa according to the Garden city movement, garden city model. Migdal was surrounded by a broad ring of orchards. Barnea developed slowly, but Afridar grew rapidly. The first homes, built in 1951, were inhabited by new Jewish immigrants from South Africa and South America, with some native-born Israelis. The first public housing project for residents of the transit camps, the Southern Hills Project (Hageva'ot Hadromiyot) or Zion Hill (Givat Zion), was built in 1952.

Under a plan signed in October 2015, seven new neighborhoods comprising 32,000 housing units, a new stretch of highway, and three new highway interchanges will be built, turning Ashkelon into the sixth-largest city in Israel.

The city has 19 elementary schools, and nine junior high and high schools. The Ashkelon Academic College opened in 1998, and now hosts thousands of students. Harvard University operates an archaeological summer school program in Ashkelon.

The city has 19 elementary schools, and nine junior high and high schools. The Ashkelon Academic College opened in 1998, and now hosts thousands of students. Harvard University operates an archaeological summer school program in Ashkelon.

An 11th-century mosque, Maqam al-Imam al-Husayn, a site of pilgrimage for both Sunnis and Shiites, which had been built under the Fatimids by Badr al-Jamali and where tradition held that the head of Mohammad's grandson Hussein ibn Ali was buried, was blown up by the Israel Defense Forces, IDF under instructions from Moshe Dayan as part of a broader programme to destroy mosques in July 1950.Brief History of Transfer of the Sacred Head of Hussain ibn Ali, From Damascus to Ashkelon to Qahera By: Qazi Dr. Shaikh Abbas Borhany PhD (USA), NDI, Shahadat al A'alamiyyah (Najaf, Iraq), M.A., LLM (Shariah) Member, Ulama Council of Pakistan. Published in ''Daily News'', Karachi, Pakistan on 3 January 200

An 11th-century mosque, Maqam al-Imam al-Husayn, a site of pilgrimage for both Sunnis and Shiites, which had been built under the Fatimids by Badr al-Jamali and where tradition held that the head of Mohammad's grandson Hussein ibn Ali was buried, was blown up by the Israel Defense Forces, IDF under instructions from Moshe Dayan as part of a broader programme to destroy mosques in July 1950.Brief History of Transfer of the Sacred Head of Hussain ibn Ali, From Damascus to Ashkelon to Qahera By: Qazi Dr. Shaikh Abbas Borhany PhD (USA), NDI, Shahadat al A'alamiyyah (Najaf, Iraq), M.A., LLM (Shariah) Member, Ulama Council of Pakistan. Published in ''Daily News'', Karachi, Pakistan on 3 January 200

.Meron Rapoport,

'History Erased,'

''Haaretz'', 5 July 2007. The area was subsequently redeveloped for a local Israeli hospital, Barzilai Medical Center, Barzilai. After the site was re-identified on the hospital grounds, funds from Mohammed Burhanuddin, leader of a Dawoodi Bohra, Shi'a Ismaili sect based in India, were used to construct a marble mosque, which is visited by Shi'ite pilgrims from India and Pakistan.

Ashkelon Khan and Museum contains archaeological finds, among them a replica of Ashkelon's Canaanite silver calf, whose discovery was reported on the front page of ''The New York Times''.

The Outdoor Museum near the municipal cultural center displays two Roman burial coffins made of marble depicting battle and hunting scenes, and famous mythological scenes.

Ashkelon Khan and Museum contains archaeological finds, among them a replica of Ashkelon's Canaanite silver calf, whose discovery was reported on the front page of ''The New York Times''.

The Outdoor Museum near the municipal cultural center displays two Roman burial coffins made of marble depicting battle and hunting scenes, and famous mythological scenes.

Ashkelon and environs is served by the Barzilai Medical Center, established in 1961. It was built in place of Hussein ibn Ali's 11th-century mosque, a center of Muslim pilgrimages, destroyed by the Israel Defense Forces, Israeli army in 1950. Situated from Gaza, the hospital has been the target of numerous Qassam rocket attacks, sometimes as many as 140 over one weekend. The hospital plays a vital role in treating wounded soldiers and terror victims. A new rocket and missile-proof emergency room is under construction.

Ashkelon and environs is served by the Barzilai Medical Center, established in 1961. It was built in place of Hussein ibn Ali's 11th-century mosque, a center of Muslim pilgrimages, destroyed by the Israel Defense Forces, Israeli army in 1950. Situated from Gaza, the hospital has been the target of numerous Qassam rocket attacks, sometimes as many as 140 over one weekend. The hospital plays a vital role in treating wounded soldiers and terror victims. A new rocket and missile-proof emergency room is under construction.

The Ashkelon Sports Arena opened in 1999. The "Jewish Eye" is a Jewish world film festival that takes place annually in Ashkelon. The festival marked its seventh year in 2010. The Breeza Music Festival has been held yearly in and around Ashkelon's amphitheatre since 1992. Most of the musical performances are free. Israel Lacrosse operates substantial youth lacrosse programs in the city and recently hosted the Turkey men's national team in Israel's first home international in 2013.

''Im schwarzen Walfisch zu Askalon'' ("In Ashkelon's Black Whale inn") is a traditional German academic commercium song that describes a drinking binge staged in the ancient city.

The Ashkelon Sports Arena opened in 1999. The "Jewish Eye" is a Jewish world film festival that takes place annually in Ashkelon. The festival marked its seventh year in 2010. The Breeza Music Festival has been held yearly in and around Ashkelon's amphitheatre since 1992. Most of the musical performances are free. Israel Lacrosse operates substantial youth lacrosse programs in the city and recently hosted the Turkey men's national team in Israel's first home international in 2013.

''Im schwarzen Walfisch zu Askalon'' ("In Ashkelon's Black Whale inn") is a traditional German academic commercium song that describes a drinking binge staged in the ancient city.

File:View of the park in Afridar, Ashqelon, Israel.jpg , Park Afridar

File:Night view from Ashqelon.jpg, Night view from Marina

File:–ê—à–∫–µ–ª–æ–Ω.jpg, Beach of Ashqelon

File:–°—Ä–µ–¥–∏–∑–µ–º–Ω–æ–µ –º–æ—Ä–µ - –≤–∏–¥ —Å –ê—à–∫–µ–ª–æ–Ω–∞.jpg, Sea view

File:–£–ª–∏—Ü–∞ –õ–µ—Ç—á–∏–∫–æ–≤.JPG, Ha-Tayassim street

File:מדרחוב אשקלון.jpg, Pedestrian mall, Ashkelon

Ashkelon City Council

"Ashkelon, ancient city of the sea"

''National Geographic (magazine), National Geographic'', January 2001

Ancient Ashkelon

ÄîUniversity of Chicago

English information on Ashkelon

ÄîAshkelon Volunteers

Information and images about the historical Palestinian city of Mijdal and what remains of it today, as Ashkelon's Migdal neighbourhood {{DEFAULTSORT:Ashkelon Ashkelon, Amarna letters locations Ancient sites in Israel Canaanite cities Populated coastal places in Israel Crusade places Hebrew Bible cities Gaza–Israel conflict Medieval sites in Israel Philistine cities Phoenician cities Neolithic settlements Bronze Age sites in Israel Iron Age sites in Israel Cities in Southern District (Israel) Holy cities

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

: , , ; Philistine

The Philistines ( he, פְּלִשְׁתִּים, Pəlīštīm; Koine Greek (LXX): Φυλιστιείμ, romanized: ''Phulistieím'') were an ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan from the 12th century BC until 604 BC, when ...

: ), also known as Ascalon (; Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

: , ; Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

: , ), is a coastal city in the Southern District of Israel on the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

coast, south of Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, ◊™÷µ÷º◊ú÷æ◊ê÷∏◊ë÷¥◊ô◊ë-◊ô÷∏◊§◊ï÷π, translit=Tƒìl- æƒÄvƒ´v-YƒÅf≈ç ; ar, ÿ™ŸéŸÑŸë ÿ£Ÿéÿ®ŸêŸäÿ® ‚Äì ŸäŸéÿߟşéÿß, translit=Tall æAbƒ´b-YƒÅfƒÅ, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

, and north of the border with the Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip (;The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p.761 "Gaza Strip /'gɑːzə/ a strip of territory under the control of the Palestinian National Authority and Hamas, on the SE Mediterranean coast including the town of Gaza.. ...

. The ancient seaport of Ashkelon dates back to the Neolithic Age

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

. In the course of its history, it has been ruled by the Ancient Egyptians, the Canaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: ê§äê§çê§èê§ç ‚Äì ; he, ◊õ÷∞÷º◊Ý÷∑◊¢÷∑◊ü ‚Äì , in pausa ‚Äì ; grc-bib, ŒßŒ±ŒΩŒ±Œ±ŒΩ ‚Äì ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

ites, the Philistines

The Philistines ( he, פְּלִשְׁתִּים, Pəlīštīm; Koine Greek (LXX): Φυλιστιείμ, romanized: ''Phulistieím'') were an ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan from the 12th century BC until 604 BC, when ...

, the Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''mƒÅt A≈°≈°ur''; syc, ÐêШÐòЙ, æƒÅthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

ns, the Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

ns, the Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, oth ...

, the Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

ns, the Hasmoneans, the Romans

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

, the Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian.

...

, the Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

and the Crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

, until it was destroyed by the Mamluks

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') i ...

in 1270.

The modern city was originally located approximately 4 km inland from the ancient site, and was known as al-Majdal or al-Majdal Asqalan (Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

: ''al-Mijdal''; Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

: '' æƒíl-Mƒ´«ßdal''). In 1918, it became part of the British Occupied Enemy Territory Administration

The Occupied Enemy Territory Administration (OETA) was a joint British, French and Arab military administration over Levantine provinces of the former Ottoman Empire between 1917 and 1920, set up on 23 October 1917 following the Sinai and Pale ...

and in 1920 became part of Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, ŸÅŸÑÿ≥ÿ∑ŸäŸÜ ÿߟÑÿߟÜÿ™ÿØÿßÿ®Ÿäÿ© '; he, ◊§÷∏÷º◊ú÷∂◊©÷∞◊Ç◊™÷¥÷º◊ô◊Ý÷∏◊î (◊ê◊¥◊ô) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''‚ÄôEretz Yi≈õrƒÅ‚Äôƒìl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

. Al-Majdal on the eve of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

had 10,000 Arab inhabitants and in October 1948, the city accommodated thousands more refugees from nearby villages. Al-Majdal was the forward position of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) was a British Empire military formation, formed on 10 March 1916 under the command of General Archibald Murray from the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and the Force in Egypt (1914–15), at the beginning of ...

based in Gaza. The town was conquered by Israeli forces on 5 November 1948, by which time most of the Arab population had fled,B. Morris, The transfer of Al Majdal's remaining Palestinians to Gaza, 1950, in ''1948 and After; Israel and the Palestinians

''1948 and After: Israel and the Palestinians'' is a collection of essays by the Israeli historian Benny Morris. The book was first published in hardcover in 1990. It was revised and expanded, (largely on the basis on newly available material) an ...

''. leaving some 2,700 inhabitants, of which 500 were deported by Israeli soldiers in December 1948. Most of the remaining Arabs were deported by 1950. Today, the city's population is almost entirely Jewish.

Migdal was initially repopulated by Jewish immigrants and demobilized soldiers. It was subsequently renamed multiple times, first as Migdal Gaza, Migdal Gad and Migdal Ashkelon, until in 1953 the coastal neighborhood of Afridar was incorporated and the name "Ashkelon" was adopted for the combined town. By 1961, Ashkelon was ranked 18th among Israeli urban centers with a population of 24,000. In the population of Ashkelon was , making it the third-largest city in Israel's Southern District.

Etymology

The name Ashkelon is probablywestern Semitic

The West Semitic languages are a proposed major sub-grouping of ancient Semitic languages. The term was first coined in 1883 by Fritz Hommel.triliteral root

The roots of verbs and most nouns in the Semitic languages are characterized as a sequence of consonants or " radicals" (hence the term consonantal root). Such abstract consonantal roots are used in the formation of actual words by adding the vowel ...

("to weigh" from a Semitic root , akin to Hebrew or Arabic "weight") perhaps attesting to its importance as a center for mercantile activities. Its name appeared in Phoenician and Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

as () and (). ''Scallion

Scallions (also known as spring onions or green onions) are vegetables derived from various species in the genus ''Allium''. Scallions generally have a milder taste than most onions and their close relatives include garlic, shallot, leek, ch ...

'' and ''shallot

The shallot is a botanical variety (a cultivar) of the onion. Until 2010, the (French red) shallot was classified as a separate species, ''Allium ascalonicum''. The taxon was synonymized with ''Allium cepa'' (the common onion) in 2010, as the d ...

'' are derived from ''Ascalonia'', the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

name for Ashkelon.

Archaeology

Beginning in the 1700s the site was visited, and occasionally drawn, by a number of adventurers and tourists. It was also often scavenged for building materials. The first known excavation occurred in 1815. TheLady Hester Stanhope

Lady Hester Lucy Stanhope (12 March 1776 – 23 June 1839) was a British aristocrat, adventurer, antiquarian, and one of the most famous travellers of her age. Her archaeological excavation of Ashkelon in 1815 is considered the first to ...

dug there for two weeks using 150 workers. No real records were kept. In the 1800s some classical pieces from Askelon (though long thought to be from Thessaloniki) were sent to the Ottoman Museum. From 1920 to 1922 John Garstang

John Garstang (5 May 1876 – 12 September 1956) was a British archaeologist of the Ancient Near East, especially Egypt, Sudan, Anatolia and the southern Levant. He was the younger brother of Professor Walter Garstang, FRS, a marine biol ...

and W. J. Phythian-Adams excavated on behalf of the Palestine Exploration Fund

The Palestine Exploration Fund is a British society based in London. It was founded in 1865, shortly after the completion of the Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem, and is the oldest known organization in the world created specifically for the study ...

. They focused on two areas, one Roman and the other Philistine/Canaanite. In the years following, a number of salvage excavations were done by the Israel Antiquities Authority

The Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA, he, רשות העתיקות ; ar, داﺌرة الآثار, before 1990, the Israel Department of Antiquities) is an independent Israeli governmental authority responsible for enforcing the 1978 Law of ...

.

Modern excavation began in 1985 with the Leon Levy Expedition. Between then and 2006 seventeen seasons of work occurred, led by Lawrence Stager of Harvard University. In 2007 the next phase of excavation began under Daniel Master. It continued until 2016.

In the 1997 season a cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-sha ...

table fragment was found, being a lexical list containing both Sumerian and Canaanite language columns. It was found in a Late Bronze Age II context, about 13th century BC.

In 2012 an Iron Age IIA Philistine cemetery was discovered outside the city. In 2013 200 graves were excavated of the estimated 1,200 the cemetery contained. Seven were stone built tombs.

One ostracon and 18 jar handles were recovered inscribed with the Cypro-Minoan script

The Cypro-Minoan syllabary (CM) is an undeciphered syllabary used on the island of Cyprus during the late Bronze Age (c. 1550–1050 BC). The term "Cypro-Minoan" was coined by Arthur Evans in 1909 based on its visual similarity to Linear A on ...

. The ostracon was of local material and dated to 12th to 11th century BC. Five of the jar handles were manufactured in coastal Lebanon, two in Cyprus, and one locally. Fifteen of the handles were found in an Iron I context and the rest in Late Bronze Age context.

History

Ashkelon was the oldest and largest seaport inCanaan

Canaan (; Phoenician: ê§äê§çê§èê§ç ‚Äì ; he, ◊õ÷∞÷º◊Ý÷∑◊¢÷∑◊ü ‚Äì , in pausa ‚Äì ; grc-bib, ŒßŒ±ŒΩŒ±Œ±ŒΩ ‚Äì ;The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus T ...

, part of the pentapolis

A pentapolis (from Greek ''penta-'', 'five' and ''polis'', 'city') is a geographic and/or institutional grouping of five cities. Cities in the ancient world probably formed such groups for political, commercial and military reasons, as happened ...

(a grouping of five cities) of the Philistines

The Philistines ( he, פְּלִשְׁתִּים, Pəlīštīm; Koine Greek (LXX): Φυλιστιείμ, romanized: ''Phulistieím'') were an ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan from the 12th century BC until 604 BC, when ...

, north of Gaza and south of Jaffa

Jaffa, in Hebrew Yafo ( he, יָפוֹ, ) and in Arabic Yafa ( ar, يَافَا) and also called Japho or Joppa, the southern and oldest part of Tel Aviv-Yafo, is an ancient port city in Israel. Jaffa is known for its association with the b ...

.

Neolithic period

The

The Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

site of Ashkelon is located on the Mediterranean coast

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the eas ...

, north of Tel Ashkelon. It is dated by Radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

to 7900 bp (uncalibrated), to the poorly known Pre-Pottery Neolithic C phase of the Neolithic. It was discovered and excavated in 1954 by French archaeologist Jean Perrot

Jean Perrot (1920 – 24 December 2012) was a French archaeologist who specialised in the late prehistory of the Middle East and Near East.

Biography

Perrot was a graduate of the Ecole du Louvre where he studied under two experts in Syrian arc ...

. In 1997–1998, a large scale salvage project was conducted at the site by Yosef Garfinkel

Yosef Garfinkel (hebrew: ◊ô◊ï◊°◊£ ◊í◊®◊§◊ô◊Ý◊ß◊ú; born 1956) is an Israeli archaeologist and academic. He is Professor of Prehistoric Archaeology and of Archaeology of the Biblical Period at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Biography

Yosef (Yo ...

on behalf of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI; he, ◊î÷∑◊ê◊ï÷º◊Ý÷¥◊ô◊ë÷∂◊®÷∞◊°÷¥◊ô◊ò÷∏◊î ◊î÷∑◊¢÷¥◊ë÷∞◊®÷¥◊ô◊™ ◊ë÷¥÷º◊ô◊®◊ï÷º◊©÷∏◊Å◊ú÷∑◊ô÷¥◊ù) is a public research university based in Jerusalem, Israel. Co-founded by Albert Einstein and Dr. Chaim Weiz ...

and nearly were examined. A final excavation report was published in 2008.

In the site over a hundred fireplaces and hearth

A hearth () is the place in a home where a fire is or was traditionally kept for home heating and for cooking, usually constituted by at least a horizontal hearthstone and often enclosed to varying degrees by any combination of reredos (a lo ...

s were found and numerous pits, but no solid architecture, except for one wall. Various phases of occupation were found, one atop the other, with sterile layers of sea sand between them. This indicates that the site was occupied on a seasonal basis.

The main finds were enormous quantities of around 100,000 animal bones and around 20,000

The main finds were enormous quantities of around 100,000 animal bones and around 20,000 flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start fir ...

artifacts. Usually at Neolithic sites flints far outnumber animal bones. The bones belong to domesticated

Domestication is a sustained multi-generational relationship in which humans assume a significant degree of control over the reproduction and care of another group of organisms to secure a more predictable supply of resources from that group. A ...

and non-domesticated animals. When all aspects of this site are taken into account, it appears to have been used by pastoral nomads

Nomadic pastoralism is a form of pastoralism in which livestock are herded in order to seek for fresh pastures on which to graze. True nomads follow an irregular pattern of movement, in contrast with transhumance, where seasonal pastures are fix ...

for meat processing. The nearby sea could supply salt necessary for the conservation

Conservation is the preservation or efficient use of resources, or the conservation of various quantities under physical laws.

Conservation may also refer to:

Environment and natural resources

* Nature conservation, the protection and manageme ...

of meat.

Canaanite settlement

The city was originally built on a

The city was originally built on a sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates) ...

outcropping and has a good underground water supply

Water supply is the provision of water by public utilities, commercial organisations, community endeavors or by individuals, usually via a system of pumps and pipes. Public water supply systems are crucial to properly functioning societies. Thes ...

. It was relatively large as an ancient city with as many as 15,000 people living inside the walls. Ashkelon was a thriving Middle Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

(2000–1550 BCE) city of more than . Its commanding ramparts measured long, high and thick, and even as a ruin they stand two stories high. The thickness of the walls was so great that the mudbrick city gate

A city gate is a gate which is, or was, set within a city wall. It is a type of fortified gateway.

Uses

City gates were traditionally built to provide a point of controlled access to and departure from a walled city for people, vehicles, goods ...

had a stone-lined, tunnel-like barrel vault

A barrel vault, also known as a tunnel vault, wagon vault or wagonhead vault, is an architectural element formed by the extrusion of a single curve (or pair of curves, in the case of a pointed barrel vault) along a given distance. The curves are ...

, coated with white plaster, to support the superstructure: it is the oldest such vault

Vault may refer to:

* Jumping, the act of propelling oneself upwards

Architecture

* Vault (architecture), an arched form above an enclosed space

* Bank vault, a reinforced room or compartment where valuables are stored

* Burial vault (enclosure ...

ever found. Later Roman and Islamic fortifications, faced with stone, followed the same footprint, a vast semicircle protecting Ashkelon on the land side. On the sea it was defended by a high natural bluff. A roadway more than in width ascended the rampart from the harbor and entered a gate at the top.

In 1991 the ruins of a small ceramic tabernacle was found a finely cast bronze statuette of a bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not castrated) adult male of the species ''Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e., cows), bulls have long been an important symbol in many religions,

includin ...

calf, originally silvered, long. Images of calves and bulls were associated with the worship of the Canaanite gods El and Baal

Baal (), or Baal,; phn, , ba øl; hbo, , ba øal, ). ( ''ba øal'') was a title and honorific meaning "owner", "lord" in the Northwest Semitic languages spoken in the Levant during Ancient Near East, antiquity. From its use among people, it cam ...

.

Beginning in the time of Thutmose III

Thutmose III (variously also spelt Tuthmosis or Thothmes), sometimes called Thutmose the Great, was the sixth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Officially, Thutmose III ruled Egypt for almost 54 years and his reign is usually dated from 28 ...

(1479-1425 BC) the city was under Egyptian control, under a local governor. In the Merneptah Stele

The Merneptah Stele, also known as the Israel Stele or the Victory Stele of Merneptah, is an inscription by Merneptah, a pharaoh in ancient Egypt who reigned from 1213–1203 BCE. Discovered by Flinders Petrie at Thebes in 1896, it is now hous ...

that Pharaoh (1213–1203 BC) notes putting down a rebellion in the city. Ashkelon is mentioned in the Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

Execration Texts

Execration texts, also referred to as proscription lists, are ancient Egyptian hieratic texts, listing enemies of the pharaoh, most often enemies of the Egyptian state or troublesome foreign neighbors. The texts were most often written upon stat ...

of the 11th dynasty as "Asqanu." In the Amarna letters

The Amarna letters (; sometimes referred to as the Amarna correspondence or Amarna tablets, and cited with the abbreviation EA, for "El Amarna") are an archive, written on clay tablets, primarily consisting of diplomatic correspondence between t ...

( 1350 BC), there are seven letters to and from Ashkelon's (Ašqaluna) king Yidya Yidya, and also Idiya, was the Canaanite mayor/ruler of ancient Ašqaluna/Ashkelon in the 1350- 1335 BC Amarna letters correspondence.

Yidya is mainly referenced in the Amarna letters corpus, in his own letters: EA 320–326, (EA for 'el Ama ...

, and the Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: ''pr Íú•Íú£''; cop, , P«ùrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Par ø≈ç'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the an ...

. One letter from the pharaoh to Yidya was discovered in the early 1900s.

Philistine settlement

The Philistines conquered Canaanite Ashkelon about 1150 BCE. Their earliest pottery, types of structures and inscriptions are similar to the early Greek urbanised centre atMycenae

Mycenae ( ; grc, Μυκῆναι or , ''Mykē̂nai'' or ''Mykḗnē'') is an archaeological site near Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about south-west of Athens; north of Argos; and south of Corinth. Th ...

in mainland Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, adding weight to the hypothesis that the Philistines were one of the populations among the "Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples are a hypothesized seafaring confederation that attacked ancient Egypt and other regions in the East Mediterranean prior to and during the Late Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BCE).. Quote: "First coined in 1881 by the Fren ...

" that upset cultures throughout the eastern Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

at that time.

Ashkelon became one of the five Philistine cities that were constantly warring with the Israelites

The Israelites (; , , ) were a group of Semitic-speaking tribes in the ancient Near East who, during the Iron Age, inhabited a part of Canaan.

The earliest recorded evidence of a people by the name of Israel appears in the Merneptah Stele o ...

and later the United Kingdom of Israel

The United Monarchy () in the Hebrew Bible refers to Israel and Judah under the reigns of Saul, David, and Solomon. It is traditionally dated to have lasted between and . According to the biblical account, on the succession of Solomon's son Re ...

and successive Kingdom of Judah

The Kingdom of Judah ( he, , ''Y…ôh≈´dƒÅ''; akk, íÖÄíåëíÅïíÄÄíÄÄ ''Ya'√∫d√¢'' 'ia-√∫-da-a-a'' arc, ê§Åê§âê§ïê§Éê§Öê§É ''Bƒìyt DƒÅwƒ´·∏è'', " House of David") was an Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. Ce ...

. According to Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

, its temple of Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never fa ...

was the oldest of its kind, imitated even in Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

, and he mentions that this temple was pillaged by marauding Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved f ...

during the time of their sway over the Medes

The Medes (Old Persian: ; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media between western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, the ...

(653–625 BCE). As it was the last of the Philistine cities to hold out against Babylonian king

The king of Babylon (Akkadian language, Akkadian: ''šakkanakki Bābili'', later also ''šar Bābili'') was the ruler of the ancient Mesopotamian city of Babylon and its kingdom, Babylonia, which existed as an independent realm from the 19th centur ...

Nebuchadnezzar II

Nebuchadnezzar II (Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nab√ª-kudurri-u·π£ur'', meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir"; Biblical Hebrew: ''N…ô·∏á≈´·∏µa·∏ène æ·π£·π£ar''), also spelled Nebuchadrezzar II, was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling ...

. When it fell in 604 BCE, burnt and destroyed and its people taken into exile, the Philistine era was over.

Persian, Hellenistic and Roman periods

Ashkelon was soon rebuilt. Until the conquest of

Ashkelon was soon rebuilt. Until the conquest of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

, Ashkelon's inhabitants were influenced by the dominant Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

n culture. It is in this archaeological layer that excavations have found dog burials. It is believed the dogs may have had a sacred role; however, evidence is not conclusive. After the conquest of Alexander in the 4th century BCE, Ashkelon was an important free city and Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

seaport.

It had mostly friendly relations with the Hasmonean kingdom

The Hasmonean dynasty (; he, ''·∏§a≈°m≈çna 惴m'') was a ruling dynasty of Judea and surrounding regions during classical antiquity, from BCE to 37 BCE. Between and BCE the dynasty ruled Judea semi-autonomously in the Seleucid Empire, an ...

and Herodian kingdom

The Herodian Kingdom of Judea was a client state of the Roman Republic from 37 BCE, when Herod the Great, who had been appointed "King of the Jews" by the Roman Senate in 40/39 BCE, took actual control over the country. When Herod died in 4 BCE, ...

of Judea, in the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE. In a significant case of an early witch-hunt

A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. The Witch trials in the early modern period, classical period of witch-hunts in Early Modern Europe and European Colon ...

, during the reign of the Hasmonean queen Salome Alexandra

Salome Alexandra, or Shlomtzion ( grc-gre, Œ£Œ±ŒªœéŒºŒ∑ ·ºàŒªŒµŒæŒ¨ŒΩŒ¥œÅŒ±; he, , ''≈Ý…ôl≈çm·π£ƒ´yy≈çn''; 141–67 BCE), was one of three women to rule over Judea, the other two being Athaliah and Devora. The wife of Aristobulus I, and a ...

, the court of Simeon ben Shetach

Simeon ben Shetach, or Shimon ben Shetach or Shatach (), ''circa'' 140-60 BCE, was a Pharisee scholar and Nasi of the Sanhedrin during the reigns of Alexander Jannæus (c. 103-76 BCE) and his successor, Queen Salome Alexandra (c. 76-67 BCE), who ...

sentenced to death eighty women in Ashkelon who had been charged with sorcery

Sorcery may refer to:

* Magic (supernatural), the application of beliefs, rituals or actions employed to subdue or manipulate natural or supernatural beings and forces

** Witchcraft, the practice of magical skills and abilities

* Magic in fiction, ...

. Herod the Great

Herod I (; ; grc-gre, ; c. 72 – 4 or 1 BCE), also known as Herod the Great, was a Roman Jewish client king of Judea, referred to as the Herodian kingdom. He is known for his colossal building projects throughout Judea, including his renov ...

, who became a client king of Rome over Judea and its environs in 30 BCE, had not received Ashkelon, yet he built monumental buildings there: bath houses, elaborate fountains and large colonnades. A discredited tradition suggests Ashkelon was his birthplace. In 6 CE, when a Roman imperial province was set in Judea, overseen by a lower-rank governor, Ashkelon was moved directly to the higher jurisdiction of the governor of Syria province.

The city remained loyal to Rome during the Great Revolt, 66–70 CE.

Byzantine period

The city of Ascalon appears on a fragment of the 6th-century Madaba Map. The bishops of Ascalon whose names are known include Sabinus, who was at theFirst Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

in 325, and his immediate successor, Epiphanius. Auxentius took part in the First Council of Constantinople

The First Council of Constantinople ( la, Concilium Constantinopolitanum; grc-gre, Σύνοδος τῆς Κωνσταντινουπόλεως) was a council of Christian bishops convened in Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) in AD 381 b ...

in 381, Jobinus in a synod held in Lydda in 415, Leontius in both the Robber Council of Ephesus

The Second Council of Ephesus was a Christological church synod in 449 AD convened by Emperor Theodosius II under the presidency of Pope Dioscorus I of Alexandria. It was intended to be an ecumenical council, and it is accepted as such by the mi ...

in 449 and the Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; la, Concilium Chalcedonense), ''Synodos tēs Chalkēdonos'' was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bith ...

in 451. Bishop Dionysius, who represented Ascalon at a synod in Jerusalem in 536, was on another occasion called upon to pronounce on the validity of a baptism with sand in waterless desert and sent the person to be baptized in water.

No longer a residential bishopric, Ascalon is today listed by the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

as a titular see

A titular see in various churches is an episcopal see of a former diocese that no longer functions, sometimes called a "dead diocese". The ordinary or hierarch of such a see may be styled a "titular metropolitan" (highest rank), "titular archbish ...

.

Early Islamic period

During the Muslim conquest of Palestine begun in 633–634, Ascalon (called ''Asqalan'' by the Arabs) became one of the last Byzantine cities in the region to fall. It may have been temporarily occupied byAmr ibn al-As

( ar, عمرو بن العاص السهمي; 664) was the Arab commander who led the Muslim conquest of Egypt and served as its governor in 640–646 and 658–664. The son of a wealthy Qurayshite, Amr embraced Islam in and was assigned impor ...

, but definitively surrendered to Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan

Mu'awiya I ( ar, ŸÖÿπÿߟàŸäÿ© ÿ®ŸÜ ÿ£ÿ®Ÿä ÿ≥ŸÅŸäÿߟÜ, Mu øƒÅwiya ibn Abƒ´ SufyƒÅn; ‚ÄìApril 680) was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the deat ...

(who later founded the Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661‚Äì750 CE; , ; ar, Ÿ±ŸÑŸíÿÆŸêŸÑŸéÿߟşéÿ© Ÿ±ŸÑŸíÿ£ŸèŸÖŸéŸàŸêŸäŸéŸëÿ©, al-KhilƒÅfah al- æUmawƒ´yah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

) not long after he captured the Byzantine district capital of Caesarea in 640. The Byzantines reoccupied Asqalan during the Second Muslim Civil War (680–692), but the Umayyad caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, Abd al-Malik () recaptured and fortified it. A son of Caliph Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik, Sulayman (), whose family resided in Jund Filastin, Palestine, was buried in the city. An inscription found in the city indicates that the Abbasid Caliphate, Abbasid caliph al-Mahdi ordered the construction of a mosque with a minaret in Asqalan in 772.

Asqalan prospered under the Fatimid Caliphate and contained a mint and secondary naval base. Along with a few other coastal towns in Palestine, it remained in Fatimid hands when most of Bilad al-Sham, Islamic Syria was conquered by the Seljuq dynasty, Seljuks. However, during this period, Fatimid rule over Asqalan was periodically reduced to nominal authority over the city's governor. In 1091, a couple of years after a campaign by grand vizier Badr al-Jamali to reestablish Fatimid control over the region, the head of Husayn ibn Ali (a grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad) was "rediscovered", prompting Badr to order the construction of a new mosque and ''mashhad'' (shrine or mausoleum) to hold the relic. (According to another source, the shrine was built in 1098 by the Vizier (Fatimid Caliphate), Fatimid vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah.) The mausoleum was described as the most magnificent building in Ashkelon. In the British Mandate period it was a "large ''maqam'' on top of a hill" with no tomb, but a fragment of a pillar showing the place where the head had been buried.Canaan, 1927, p151

/ref> In July 1950, the shrine was destroyed at the instructions of Moshe Dayan in accordance with a 1950s Israeli policy of erasing Muslim historical sites within Israel. Around 2000, a modest marble mosque was constructed on the site by Mohammed Burhanuddin, an Indian Islamic leader of the Dawoodi Bohras.

Crusaders, Ayyubids, and Mamluks

During the Crusades, Asqalan (known to the Crusaders as ''Ascalon'') was an important city due to its location near the coast and between the Crusader states, Crusader States and Egypt. In 1099, shortly after the Siege of Jerusalem (1099), Siege of Jerusalem, a Fatimid army that had been sent to relieve Jerusalem was defeated by a Crusader force at the Battle of Ascalon. The city itself was not captured by the Crusaders because of internal disputes among their leaders. This battle is widely considered to have signified the end of the First Crusade. As a result of military reinforcements from Egypt and a large influx of refugees from areas conquered by the Crusaders, Asqalan became a major Fatimid frontier post. The Fatimids utilized it to launch raids into the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Trade ultimately resumed between Asqalan and Crusader-controlled Jerusalem, though the inhabitants of Asqalan regularly struggled with shortages in food and supplies, necessitating the provision of goods and relief troops to the city from Egypt on several occasions each year. According to William of Tyre, the entire civilian population of the city was included in the Fatimid army registers. The Crusaders' capture of the port city of Tyre, Lebanon, Tyre in 1134 and their construction of a ring of fortresses around the city to neutralize its threat to Jerusalem strategically weakened Asqalan. In 1150 the Fatimids fortified the city with fifty-three towers, as it was their most important frontier fortress. Three years later, after a Siege of Ascalon, seven-month siege, the city was captured by a Crusader army led by King Baldwin III of Jerusalem. The Fatimids secured the head of Husayn from its mausoleum in the city and transported it to their capital Cairo. Ascalon was then added to the County of Jaffa and Ascalon, County of Jaffa to form the County of Jaffa and Ascalon, which became one of the four major seigneuries of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

After the Siege of Jerusalem (1099), Crusader conquest of Jerusalem the six elders of the Karaite Judaism, Karaite Jewish community in Ashkelon contributed to the ransoming of captured Jews and holy relics from Jerusalem's new rulers. The Letter of the Karaite elders of Ascalon, which was sent to the Jewish elders of Alexandria, describes their participation in the ransom effort and the ordeals suffered by many of the freed captives. A few hundred Jews, Karaites and Rabbanites, were living in Ashkelon in the second half of the 12th century, but moved to Jerusalem when the city was destroyed in 1191.

In 1187, Saladin took Ashkelon as part of his conquest of the Crusader states, Crusader States following the Battle of Hattin. In 1191, during the Third Crusade, Saladin demolished the city because of its potential strategic importance to the Christians, but the leader of the Crusade, King Richard I of England, constructed a citadel upon the ruins. Ashkelon subsequently remained part of the diminished territories of Outremer throughout most of the 13th century and Richard, Earl of Cornwall reconstructed and refortified the citadel during 1240–41, as part of the Crusader policy of improving the defences of coastal sites. The Egyptians retook Ashkelon in 1247 during As-Salih Ayyub's conflict with the Crusader States and the city was returned to Muslim rule. The Mamluk dynasty came into power in Egypt in 1250 and the ancient and Middle Ages, medieval history of Ashkelon was brought to an end in 1270, when the Mamluk sultan Baybars ordered the citadel and harbour at the site to be destroyed. As a result of this destruction, the site was abandoned by its inhabitants and fell into disuse.

During the Crusades, Asqalan (known to the Crusaders as ''Ascalon'') was an important city due to its location near the coast and between the Crusader states, Crusader States and Egypt. In 1099, shortly after the Siege of Jerusalem (1099), Siege of Jerusalem, a Fatimid army that had been sent to relieve Jerusalem was defeated by a Crusader force at the Battle of Ascalon. The city itself was not captured by the Crusaders because of internal disputes among their leaders. This battle is widely considered to have signified the end of the First Crusade. As a result of military reinforcements from Egypt and a large influx of refugees from areas conquered by the Crusaders, Asqalan became a major Fatimid frontier post. The Fatimids utilized it to launch raids into the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Trade ultimately resumed between Asqalan and Crusader-controlled Jerusalem, though the inhabitants of Asqalan regularly struggled with shortages in food and supplies, necessitating the provision of goods and relief troops to the city from Egypt on several occasions each year. According to William of Tyre, the entire civilian population of the city was included in the Fatimid army registers. The Crusaders' capture of the port city of Tyre, Lebanon, Tyre in 1134 and their construction of a ring of fortresses around the city to neutralize its threat to Jerusalem strategically weakened Asqalan. In 1150 the Fatimids fortified the city with fifty-three towers, as it was their most important frontier fortress. Three years later, after a Siege of Ascalon, seven-month siege, the city was captured by a Crusader army led by King Baldwin III of Jerusalem. The Fatimids secured the head of Husayn from its mausoleum in the city and transported it to their capital Cairo. Ascalon was then added to the County of Jaffa and Ascalon, County of Jaffa to form the County of Jaffa and Ascalon, which became one of the four major seigneuries of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

After the Siege of Jerusalem (1099), Crusader conquest of Jerusalem the six elders of the Karaite Judaism, Karaite Jewish community in Ashkelon contributed to the ransoming of captured Jews and holy relics from Jerusalem's new rulers. The Letter of the Karaite elders of Ascalon, which was sent to the Jewish elders of Alexandria, describes their participation in the ransom effort and the ordeals suffered by many of the freed captives. A few hundred Jews, Karaites and Rabbanites, were living in Ashkelon in the second half of the 12th century, but moved to Jerusalem when the city was destroyed in 1191.

In 1187, Saladin took Ashkelon as part of his conquest of the Crusader states, Crusader States following the Battle of Hattin. In 1191, during the Third Crusade, Saladin demolished the city because of its potential strategic importance to the Christians, but the leader of the Crusade, King Richard I of England, constructed a citadel upon the ruins. Ashkelon subsequently remained part of the diminished territories of Outremer throughout most of the 13th century and Richard, Earl of Cornwall reconstructed and refortified the citadel during 1240–41, as part of the Crusader policy of improving the defences of coastal sites. The Egyptians retook Ashkelon in 1247 during As-Salih Ayyub's conflict with the Crusader States and the city was returned to Muslim rule. The Mamluk dynasty came into power in Egypt in 1250 and the ancient and Middle Ages, medieval history of Ashkelon was brought to an end in 1270, when the Mamluk sultan Baybars ordered the citadel and harbour at the site to be destroyed. As a result of this destruction, the site was abandoned by its inhabitants and fell into disuse.

Ottoman period

El-Jurah

The Palestinian village of Al-Jura (El-Jurah) stood northeast of and immediately adjacent to Tel Ashkelon and is documented in Ottoman tax registers.Majdal

The Arab village of Majdal was mentioned by historians and tourists at the end of the 15th century. In 1596, Ottoman records showed Majdal to be a large village of 559 Muslim households, making it the 7th-most-populous locality in Palestine after Safed, Safad, Jerusalem, Gaza, Nablus, Hebron and Kafr Kanna.Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 144Petersen, Andrew (2005). ''The Towns of Palestine under Muslim Rule AD 600–1600''. BAR International Series 1381. p. 133. An official Ottoman village list of about 1870 showed that ''Medschdel'' had a total of 420 houses and a population of 1175, though the population count included men only.Mandatory Palestine

El-Jurah

El-Jurah was depopulated during the 1948 war.Majdal

In the 1922 census of Palestine, ''Majdal'' had a population of 5,064; 33 Christians and 5,031 Muslims,Barron, 1923, Table V, Sub-district of Gaza, p

In the 1922 census of Palestine, ''Majdal'' had a population of 5,064; 33 Christians and 5,031 Muslims,Barron, 1923, Table V, Sub-district of Gaza, p8

/ref> increasing in the 1931 census of Palestine, 1931 census to 6,166 Muslims and 41 Christians.Palestine Office of Statistics, Vital Statistical Tables 1922–1945, Table A8. In the Village Statistics, 1945, 1945 statistics Majdal had a population of 9,910; ninety Christians and 9,820 Muslims,Department of Statistics, 1945, p

32

/ref> with a total (urban and rural) of 43,680 dunams of land, according to an official land and population survey. Two thousand two hundred and fifty dunes were public land; all the rest was owned by Arabs.Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. ''Village Statistics, April, 1945.'' Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p

46

/ref> of the dunams, 2,337 were used for citrus and bananas, 2,886 were plantations and irrigable land, 35,442 for cereals, while 1,346 were built-up land. Majdal was especially known for its weaving industry. The town had around 500 looms in 1909. In 1920 a British Government report estimated that there were 550 cotton looms in the town with an annual output worth 30–40 million French franc, francs. But the industry suffered from imports from Europe and by 1927 only 119 weaving establishments remained. The three major fabrics produced were "malak" (silk), 'ikhdari' (bands of red and green) and 'jiljileh' (dark red bands). These were used for festival dresses throughout Southern Palestine. Many other fabrics were produced, some with poetic names such as ''ji'nneh u nar'' ("heaven and hell"), ''nasheq rohoh'' ("breath of the soul") and ''abu mitayn'' ("father of two hundred").

Israel

528

–529. Moshe Dayan and Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion were in favor of expulsion, while Mapam and the Israeli labor union Histadrut objected. The government offered the Palestinians positive inducements to leave, including a favorable currency exchange, but also caused panic through night-time raids. The first group was deported to the

Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip (;The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p.761 "Gaza Strip /'gɑːzə/ a strip of territory under the control of the Palestinian National Authority and Hamas, on the SE Mediterranean coast including the town of Gaza.. ...

by truck on 17 August 1950 after an expulsion order had been served. The deportation was approved by Ben-Gurion and Dayan over the objections of Pinhas Lavon, secretary-general of the Histadrut, who envisioned the town as a productive example of equal opportunity. By October 1950, twenty Palestinian families remained, most of whom later moved to Lod, Lydda or Gaza. According to Israeli records, in total 2,333 Palestinians were transferred to the Gaza Strip, 60 to Jordan, 302 to other towns in Israel, and a small number remained in Ashkelon. Lavon argued that this operation dissipated "the last shred of trust the Arabs had in Israel, the sincerity of the State's declarations on democracy and civil equality, and the last remnant of confidence the Arab workers had in the Histadrut." Acting on an Egyptian complaint, the Egyptian-Israel Mixed Armistice Commission ruled that the Palestinians transferred from Majdal should be returned to Israel, but this was not done.

Ashkelon was formally granted to Israel in the 1949 Armistice Agreements. Re-population of the recently vacated Arab dwellings by Jews had been official policy since at least December 1948, but the process began slowly. The Israeli national plan of June 1949 designated al-Majdal as the site for a regional Urban area, urban center of 20,000 people. From July 1949, new immigrants and demobilization, demobilized soldiers moved to the new town, increasing the Jewish population to 2,500 within six months. These early immigrants were mostly from Yemen, North Africa, and Europe. During 1949, the town was renamed Migdal Gaza, and then Migdal Gad. Soon afterwards it became Migdal Ashkelon. The city began to expand as the population grew. In 1951, the neighborhood of Afridar was established for Jewish immigrants from South Africa, and in 1953 it was incorporated into the city. The current name Ashkelon was adopted and the town was granted Local council (Israel), local council status in 1953. In 1955, Ashkelon had more than 16,000 residents. By 1961, Ashkelon ranked 18th among Israeli urban centers with a population of 24,000. This grew to 43,000 in 1972 and 53,000 in 1983. In 2005, the population was more than 106,000.

On 1–2 March 2008, rockets fired by Hamas from the Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip (;The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p.761 "Gaza Strip /'gɑːzə/ a strip of territory under the control of the Palestinian National Authority and Hamas, on the SE Mediterranean coast including the town of Gaza.. ...

(some of them BM-21#Gaza, Grad rockets) hit Ashkelon, wounding seven, and causing property damage. Mayor Roni Mahatzri stated that "This is a Declaration of war, state of war, I know no other definition for it. If it lasts a week or two, we can handle that, but we have no intention of allowing this to become part of our daily routine." In March 2008, 230 buildings and 30 cars were damaged by rocket fire on Ashkelon.

On 12 May 2008, a rocket fired from the northern Gazan city of Beit Lahia, Beit Lahiya hit a shopping mall in southern Ashkelon, causing significant structural damage. According to ''The Jerusalem Post'', four people were seriously injured and 87 were treated for Post-traumatic stress disorder, shock. Fifteen people suffered minor to moderate injuries as a result of the collapsed structure. Southern District Chief of police, Police chief Uri Bar-Lev believed the Grad-model Katyusha rocket launcher, Katyusha rocket was manufactured in Iran.

In March 2009, a Qassam rocket hit a school, destroying classrooms and injuring two people.

In November 2014, the mayor, Itamar Shimoni, began a policy of discrimination against Arab workers, refusing to allow them to work on city projects to build bomb shelters for children. His discriminatory actions brought criticism from others, including Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Jerusalem mayor Nir Barkat who likened the discrimination to the anti-Semitism experienced by Jews in Europe 70 years earlier.

On May 11, 2021, Hamas fired 137 rockets on Ashkelon killing 2 and injuring many others.

Urban development

Economy

Ashkelon is the northern terminus for the Trans-Israel pipeline, which brings petroleum products from Eilat to an Oil depot, oil terminal at the port. The Ashkelon seawater reverse osmosis (SWRO) desalination plant is the largest in the world. The project was developed as a BOT (build–operate–transfer) by a consortium of three international companies: Veolia water, IDE Technologies Ltd., IDE Technologies and Elran. In March 2006, it was voted "Desalination Plant of the Year" in the Global Water Awards. Since 1992, Israel Beer Breweries has been operating in Ashkelon, brewing Carlsberg Group, Carlsberg and Tuborg Brewery, Tuborg beer for the Israeli market. The brewery is owned by the Central Bottling Company, which has also held the Israeli franchise for Coca-Cola products since 1968. ''Arak Ashkelon'', a local brand of Arak (drink), arak, is operating since 1925 and distributed throughout Israel.Education

The city has 19 elementary schools, and nine junior high and high schools. The Ashkelon Academic College opened in 1998, and now hosts thousands of students. Harvard University operates an archaeological summer school program in Ashkelon.

The city has 19 elementary schools, and nine junior high and high schools. The Ashkelon Academic College opened in 1998, and now hosts thousands of students. Harvard University operates an archaeological summer school program in Ashkelon.

Landmarks

Ashkelon National Park

The ancient site of Ashkelon is now a Ashkelon National Park, national park on the city's southern coast. The walls that encircled the city are still visible, as well as Canaanite earth ramparts. The park contains Byzantine, Crusader and Roman ruins. The largest dog cemetery in the ancient world was discovered in Ashkelon.Bath Houses

In 1986 ruins of 4th- to 6th-century baths were found in Ashkelon. The bath houses are believed to have been used for prostitution. The remains of nearly 100 mostly male infants were found in a sewer under the bathhouse, leading to conjectures that prostitutes had discarded their unwanted newborns there.Religious sites

Places of worship

The remains of a 4th-century Byzantine church (building), church with marble slab flooring and glass mosaic walls can be seen in the Barnea Quarter. Remains of a synagogue from this period have also been found.Maqam al-Imam al-Husayn

An 11th-century mosque, Maqam al-Imam al-Husayn, a site of pilgrimage for both Sunnis and Shiites, which had been built under the Fatimids by Badr al-Jamali and where tradition held that the head of Mohammad's grandson Hussein ibn Ali was buried, was blown up by the Israel Defense Forces, IDF under instructions from Moshe Dayan as part of a broader programme to destroy mosques in July 1950.Brief History of Transfer of the Sacred Head of Hussain ibn Ali, From Damascus to Ashkelon to Qahera By: Qazi Dr. Shaikh Abbas Borhany PhD (USA), NDI, Shahadat al A'alamiyyah (Najaf, Iraq), M.A., LLM (Shariah) Member, Ulama Council of Pakistan. Published in ''Daily News'', Karachi, Pakistan on 3 January 200

An 11th-century mosque, Maqam al-Imam al-Husayn, a site of pilgrimage for both Sunnis and Shiites, which had been built under the Fatimids by Badr al-Jamali and where tradition held that the head of Mohammad's grandson Hussein ibn Ali was buried, was blown up by the Israel Defense Forces, IDF under instructions from Moshe Dayan as part of a broader programme to destroy mosques in July 1950.Brief History of Transfer of the Sacred Head of Hussain ibn Ali, From Damascus to Ashkelon to Qahera By: Qazi Dr. Shaikh Abbas Borhany PhD (USA), NDI, Shahadat al A'alamiyyah (Najaf, Iraq), M.A., LLM (Shariah) Member, Ulama Council of Pakistan. Published in ''Daily News'', Karachi, Pakistan on 3 January 200.Meron Rapoport,

'History Erased,'

''Haaretz'', 5 July 2007. The area was subsequently redeveloped for a local Israeli hospital, Barzilai Medical Center, Barzilai. After the site was re-identified on the hospital grounds, funds from Mohammed Burhanuddin, leader of a Dawoodi Bohra, Shi'a Ismaili sect based in India, were used to construct a marble mosque, which is visited by Shi'ite pilgrims from India and Pakistan.

Shrines