Arthur Balfour on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

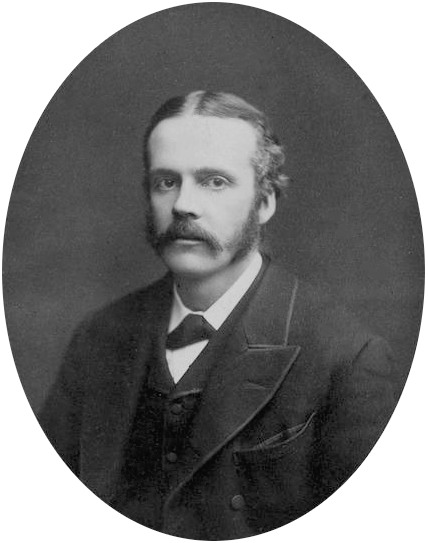

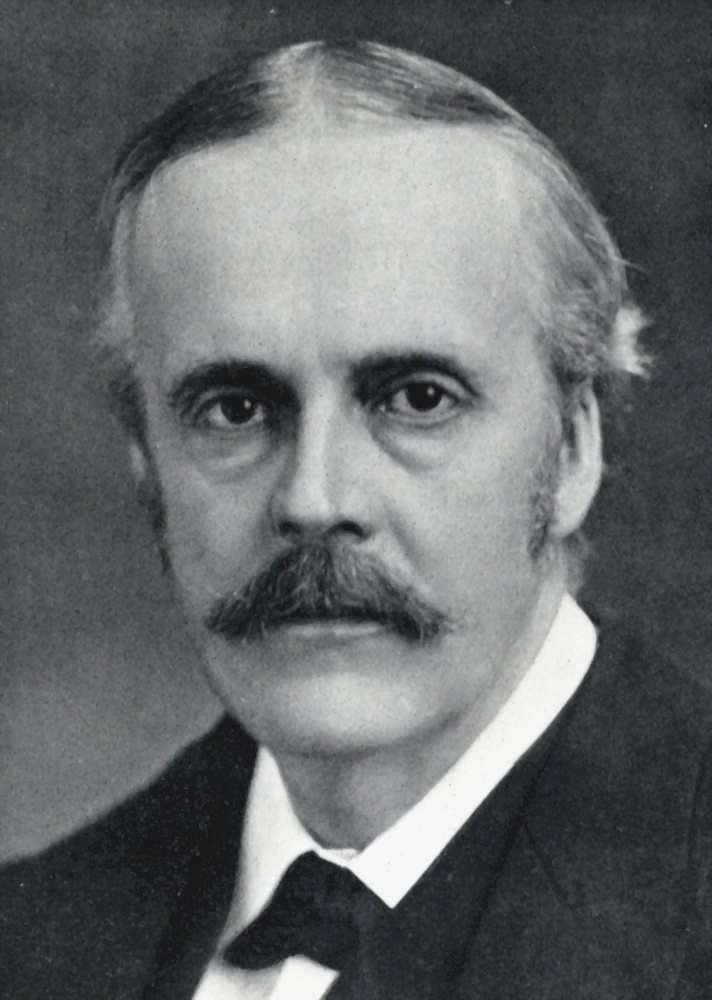

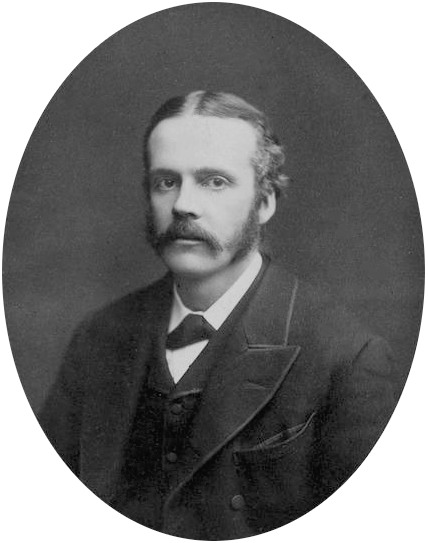

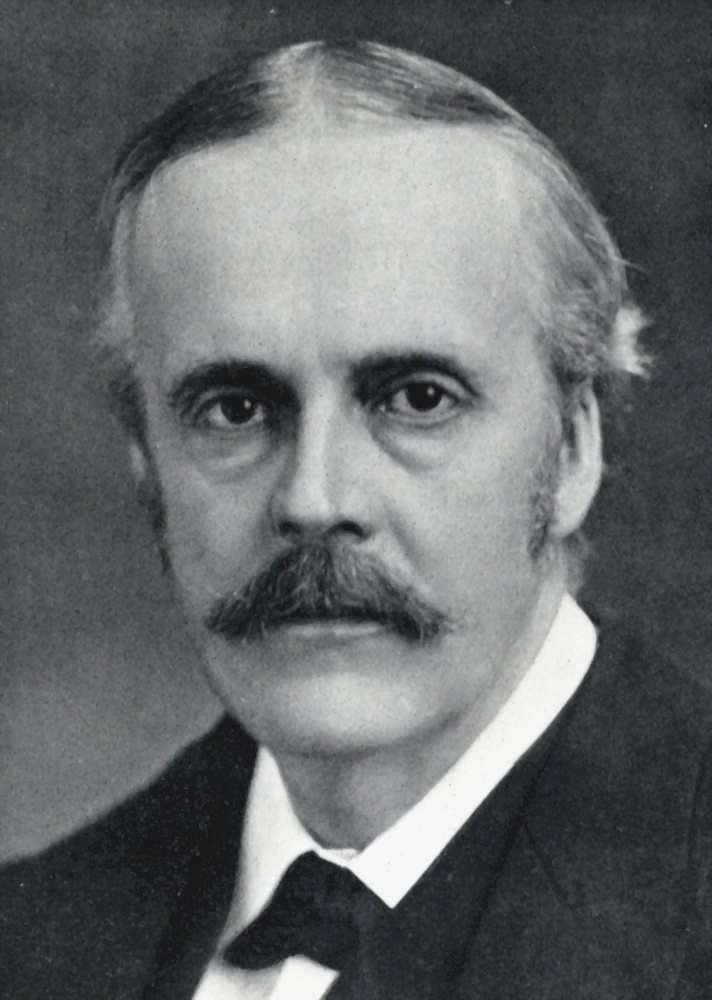

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British

Arthur Balfour was born at

Arthur Balfour was born at

In 1874 Balfour was elected

In 1874 Balfour was elected

After the general election of 1906 Balfour remained party leader, his position strengthened by Joseph Chamberlain's absence from the House of Commons after his stroke in July 1906, but he was unable to make much headway against the huge Liberal majority in the Commons. An early attempt to score a debating triumph over the government, made in Balfour's usual abstruse, theoretical style, saw Campbell-Bannerman respond with: "Enough of this foolery," to the delight of his supporters. Balfour made the controversial decision, with Lord Lansdowne, to use the heavily Unionist

After the general election of 1906 Balfour remained party leader, his position strengthened by Joseph Chamberlain's absence from the House of Commons after his stroke in July 1906, but he was unable to make much headway against the huge Liberal majority in the Commons. An early attempt to score a debating triumph over the government, made in Balfour's usual abstruse, theoretical style, saw Campbell-Bannerman respond with: "Enough of this foolery," to the delight of his supporters. Balfour made the controversial decision, with Lord Lansdowne, to use the heavily Unionist

Balfour's reputation among historians is mixed. There is agreement about his achievements, as represented by

Balfour's reputation among historians is mixed. There is agreement about his achievements, as represented by

excerpt

* Alderson, Bernard. ''Arthur James Balfour, the man and his work'' (1903

online

* Brendon, Piers: ''Eminent Edwardians'' (1980) ch 2 * * Dugdale, Blanche: '' Arthur James Balfour, First Earl of Balfour KG, OM, FRS- Volume 1'', (1936); ''Arthur James Balfour, First Earl of Balfour KG, OM, FRS- Volume 2- 1906–1930'', (1936), official life by his niece

vol 1 and 2 online free

* Egremont, Max: ''A life of Arthur James Balfour'',

online

* Mackay, Ruddock F., and H. C. G. Matthew. "Balfour, Arthur James, first earl of Balfour (1848–1930)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 201

accessed 19 Nov 2016

18,000 word scholarly biography * Pearce, Robert and Graham Goodlad. ''British Prime Ministers From Balfour to Brown'' (2013) pp 1–11. * * Young, Kenneth: '' Arthur James Balfour: The happy life of the Politician, Prime Minister, Statesman and Philosopher- 1848–1930'', G. Bell and Sons, 196

online

* Zebel, Sydney Henry. ''Balfour: a political biography'' (ICON Group International, 1973

online

online

* Davis, Peter. "The Liberal Unionist party and the Irish policy of Lord Salisbury's government, 1886–1892." ''Historical Journal'' 18.1 (1975): 85–104

online

* Dutton, David. ''His Majesty's Loyal Opposition: the Unionist Party in Opposition 1905-1915'' (Liverpool UP, 1992). * Ellenberger, Nancy W. ''Balfour's World: Aristocracy and Political Culture at the Fin de Siècle'' (2015)

excerpt

* Gollin, Alfred M. ''Balfour's burden: Arthur Balfour and imperial preference''(1965). * Green, E.H.H. ''The Crisis of Conservatism: the politics, economics and ideology of the British Conservative Party, 1880-1914'' (Routledge, 1995) * Halévy, Élie (1926) ''Imperialism And The Rise Of Labour'' (1926

online

* Halévy, Élie (1956) ''A History Of The English People: Epilogue vol 1: 1895-1905'' (1929

online

as prime minister pp 131ff,. * Jacyna, Leon Stephen. "Science and social order in the thought of A.J. Balfour." ''Isis'' (1980): 11–34

in JSTOR

* Judd, Denis. ''Balfour and the British Empire: a study in Imperial evolution 1874–1932'' (1968)

online

* Marriott, J. A. R. ''Modern England, 1885–1945'' (1948), pp. 180–99, on Balfour as Prime Minister

online

* Massie, Robert K. '' Dreadnought: Britain, Germany, and the Coming of the Great War'' (1992) pp 310–519, a popular account of Balfour's foreign and naval policies as prime minister. * Mathew, William M. "The Balfour Declaration and the Palestine Mandate, 1917–1923: British Imperialist Imperatives." ''British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies'' 40.3 (2013): 231–250. * O'Callaghan, Margaret. ''British high politics and a nationalist Ireland: criminality, land and the law under Forster and Balfour'' (Cork Univ Pr, 1994). * Ramsden, John. ''A History of the Conservative Party: The age of Balfour and Baldwin, 1902–1940'' (1978); vol 3 of a scholarly history of the Conservative Party. * Rempel, Richard A. ''Unionists Divided; Arthur Balfour, Joseph Chamberlain and the Unionist Free Traders'' (1972). * Rofe, J. Simon, and Alan Tomlinson. "Strenuous competition on the field of play, diplomacy off it: the 1908 London Olympics, Theodore Roosevelt and Arthur Balfour, and transatlantic relations." ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 15.1 (2016): 60–79

online

* Shannon, Catherine B. "The Legacy of Arthur Balfour to Twentieth-Century Ireland." in Peter Collins, ed. ''Nationalism and Unionism'' (1994): 17–34. * Shannon, Catherine B. ''Arthur J. Balfour and Ireland, 1874–1922'' (Catholic Univ of America Press, 1988

online

* Sugawara, Takeshi. "Arthur Balfour and the Japanese Military Assistance during the Great War." ''International Relations'' 2012.168 (2012): pp 44–57

online

* Taylor, Tony. "Arthur Balfour and educational change: The myth revisited." ''British Journal of Educational Studies'' 42#2 (1994): 133–149. * Tomes, Jason. ''Balfour and foreign policy: the international thought of a conservative statesman'' (Cambridge University Press, 2002). * Tuchman, Barbara W.: ''

online

* Cecil, Robert, and Arthur J. Balfour. ''Salisbury-Balfour Correspondence: Letters Exchanged Between the 3. Marquess of Salisbury and His Nephew Arthur James Balfour; 1869-1892'' (Hertfordshire Record Society, 1988). * Ridley, Jane, and Clayre Percy, eds. ''The Letters of Arthur Balfour and Lady Elcho 1885–1917.'' (Hamish Hamilton, 1992). * Short, Wilfrid M., ed. ''Arthur James Balfour as Philosopher and Thinker: A Collection of the More Important and Interesting Passages in His Non-political Writings, Speeches, and Addresses, 1879-1912'' (1912).

online

More about Arthur James Balfour

on the Downing Street website. * * * * Spikily, Samir

Balfour, Arthur James Balfour, Earl of

in

{{DEFAULTSORT:Balfour, Arthur 1848 births 1930 deaths 20th-century prime ministers of the United Kingdom First Lords of the Admiralty People from East Lothian People of the Victorian era People educated at Eton College Leaders of the Conservative Party (UK) British Secretaries of State for Foreign Affairs Secretaries for Scotland Lord Presidents of the Council Lords Privy Seal Chancellors of the University of Cambridge Chancellors of the University of Edinburgh Rectors of the University of St Andrews Rectors of the University of Glasgow Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies UK MPs 1874–1880 UK MPs 1880–1885 UK MPs 1885–1886 UK MPs 1886–1892 UK MPs 1892–1895 UK MPs 1895–1900 UK MPs 1900–1906 UK MPs 1906–1910 UK MPs 1910 UK MPs 1910–1918 UK MPs 1918–1922 UK MPs who were granted peerages Members of the Privy Council of Ireland Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Anglo-Scots Scottish people of English descent Anglican philosophers Deputy Lieutenants of Ross-shire Members of the Order of Merit Scottish Presbyterians British Anglicans Scottish writers Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Knights of the Garter Fellows of the Royal Society Leaders of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom Manchester United F.C. directors and chairmen Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Presidents of the British Academy Members of Parliament of the United Kingdom for the City of London Presidents of the Aristotelian Society Chief Secretaries for Ireland Conservative Party (UK) hereditary peers Conservative Party prime ministers of the United Kingdom Chatham House people Fellows of the British Academy *1 Peers created by George V

Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern pr ...

from 1902 to 1905. As foreign secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Seen as ...

in the Lloyd George ministry

Liberal David Lloyd George formed a coalition government in the United Kingdom in December 1916, and was appointed Prime Minister of the United Kingdom by King George V. It replaced the earlier wartime coalition under H. H. Asquith, which had ...

, he issued the Balfour Declaration of 1917 on behalf of the cabinet, which supported a "home for the Jewish people" in Palestine.

Entering Parliament in 1874

Events

January–March

* January 1 – New York City annexes The Bronx.

* January 2 – Ignacio María González becomes head of state of the Dominican Republic for the first time.

* January 3 – Third Carlist War &ndas ...

, Balfour achieved prominence as Chief Secretary for Ireland

The Chief Secretary for Ireland was a key political office in the British administration in Ireland. Nominally subordinate to the Lord Lieutenant, and officially the "Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant", from the early 19th century un ...

, in which position he suppressed agrarian unrest whilst taking measures against absentee landlords. He opposed Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for Devolution, self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1 ...

, saying there could be no half-way house between Ireland remaining within the United Kingdom or becoming independent. From 1891 he led the Conservative Party in the House of Commons, serving under his uncle, Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

, whose government won large majorities in 1895

Events

January–March

* January 5 – Dreyfus affair: French officer Alfred Dreyfus is stripped of his army rank, and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil's Island.

* January 12 – The National Trust for Places of Histor ...

and 1900

As of March 1 ( O.S. February 17), when the Julian calendar acknowledged a leap day and the Gregorian calendar did not, the Julian calendar fell one day further behind, bringing the difference to 13 days until February 28 ( O.S. February 15), 2 ...

. An esteemed debater, he was bored by the mundane tasks of party management.

In July 1902, he succeeded his uncle as prime minister. In domestic policy he passed the Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903

The Land Acts (officially Land Law (Ireland) Acts) were a series of measures to deal with the question of tenancy contracts and peasant proprietorship of land in Ireland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Five such acts were introduced by ...

, which bought out most of the Anglo-Irish land owners. The Education Act 1902

The Education Act 1902 ( 2 Edw. 7 c. 42), also known as the Balfour Act, was a highly controversial Act of Parliament that set the pattern of elementary education in England and Wales for four decades. It was brought to Parliament by a Conservat ...

had a major long-term impact in modernising the school system in England and Wales and provided financial support for schools operated by the Church of England and by the Catholic Church. Nonconformists were outraged and mobilised their voters, but were unable to reverse it. In foreign and defence policy, he oversaw reform of British defence policy and supported Jackie Fisher's naval innovations. He secured the Entente Cordiale

The Entente Cordiale (; ) comprised a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic which saw a significant improvement in Anglo-French relations. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial de ...

with France, an alliance that ended centuries of intermittent conflict between the two states and their predecessors. He cautiously embraced imperial preference

Imperial Preference was a system of mutual tariff reduction enacted throughout the British Empire following the Ottawa Conference of 1932. As Commonwealth Preference, the proposal was later revived in regard to the members of the Commonwealth of N ...

as championed by Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the Cons ...

, but resignations from the Cabinet over the abandonment of free trade left his party divided. He also suffered from public anger at the later stages of the Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sou ...

(counter-insurgency warfare characterised as "methods of barbarism") and the importation of Chinese labour to South Africa ("Chinese slavery"). He resigned as prime minister in December 1905 and the following month the Conservatives suffered a landslide defeat at the 1906 election, in which he lost his own seat. He soon re-entered Parliament and continued to serve as Leader of the Opposition throughout the crisis over Lloyd George's 1909 budget, the narrow loss of two further General Elections in 1910, and the passage of the Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5 c. 13) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two Houses of Parlia ...

. He resigned as party leader in 1911.

Balfour returned as First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

in Asquith's Coalition Government (1915–16). In December 1916, he became foreign secretary in David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

's coalition. He was frequently left out of the inner workings of foreign policy, although the Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

on a Jewish homeland bore his name. He continued to serve in senior positions throughout the 1920s, and died on 19 March 1930 aged 81, having spent a vast inherited fortune. He never married. Balfour trained as a philosopherhe originated an argument against believing that human reason could determine truthand was seen as having a detached attitude to life, epitomised by a remark attributed to him: "Nothing matters very much and few things matter at all".

Background and early life

Whittingehame House

Whittingehame is a parish with a small village in East Lothian, Scotland, about halfway between Haddington and Dunbar, and near East Linton. The area is on the slopes of the Lammermuir Hills. Whittingehame Tower dates from the 15th century a ...

, East Lothian

East Lothian (; sco, East Lowden; gd, Lodainn an Ear) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland, as well as a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area. The county was called Haddingtonshire until 1921.

In 1975, the histo ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, the eldest son of James Maitland Balfour

James Maitland Balfour (5 January 1820 – 23 February 1856) was a Scottish land-owner and businessman. He made a fortune in the 19th-century railway boom, and inherited a significant portion of his father's great wealth.

He was a Conservative ...

(1820–1856) and Lady Blanche Gascoyne-Cecil (1825–1872). His father was a Scottish MP, as was his grandfather James

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

; his mother, a member of the Cecil family

Cecil may refer to:

People with the name

* Cecil (given name), a given name (including a list of people and fictional characters with the name)

* Cecil (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

Places Canada

*Cecil, Alberta, ...

descended from Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury

Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, (1 June 156324 May 1612), was an English statesman noted for his direction of the government during the Union of the Crowns, as Tudor England gave way to Stuart period, Stuart rule (1603). Lord Salisbury s ...

, was the daughter of the 2nd Marquess of Salisbury and a sister of the 3rd Marquess, the future prime minister. His godfather was the Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish soldier and Tory statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of 19th-century Britain, serving twice as prime minister of ...

, after whom he was named. He was the eldest son, third of eight children, and had four brothers and three sisters. Arthur Balfour was educated at Grange Preparatory School at Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire

Hoddesdon () is a town in the Borough of Broxbourne, Hertfordshire, lying entirely within the London Metropolitan Area and Greater London Urban Area. The area is on the River Lea and the Lee Navigation along with the New River.

Hoddesdon is ...

(1859–1861), and Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

(1861–1866), where he studied with the influential master, William Johnson Cory

William Johnson Cory (9 January 1823 – 11 June 1892), born William Johnson, was an English educator and poet. He was dismissed from his post at Eton for encouraging a culture of intimacy, possibly non-sexual, between teachers and pupils. He is ...

. He then went up to the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, where he read moral sciences

Human science (or human sciences in the plural), also known as humanistic social science and moral science (or moral sciences), studies the philosophical, biological, social, and cultural aspects of human life. Human science aims to expand our ...

at Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

(1866–1869), graduating with a second-class honours

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied (sometimes with significant variati ...

degree. His younger brother was the Cambridge embryologist Francis Maitland Balfour

Francis (Frank) Maitland Balfour, known as F. M. Balfour, (10 November 1851 – 19 July 1882) was a British biologist. He lost his life while attempting the ascent of Mont Blanc. He was regarded by his colleagues as one of the greatest biologists ...

(1851–1882).

Personal life

Balfour met his cousin May Lyttelton in 1870 when she was 19. After her two previous serious suitors had died, Balfour is said to have declared his love for her in December 1874. She died oftyphus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

on Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday is a Christian moveable feast that falls on the Sunday before Easter. The feast commemorates Christ's triumphal entry into Jerusalem, an event mentioned in each of the four canonical Gospels. Palm Sunday marks the first day of Holy ...

, 21 March 1875; Balfour arranged for an emerald ring to be buried in her coffin. Lavinia Talbot, May's older sister, believed that an engagement had been imminent, but her recollections of Balfour's distress (he was "staggered") were not written down until thirty years later.

Historian R. J. Q. Adams

Ralph James Quincy Adams (born September 22, 1943) is an author and historian. He is professor of European and British history at Texas A&M University

Texas A&M University (Texas A&M, A&M, or TAMU) is a public, land-grant, research univer ...

points out that May's letters discuss her love life in detail, but contain no evidence that she was in love with Balfour, nor that he had spoken to her of marriage. He visited her only once during her serious three-month illness, and was soon accepting social invitations again within a month of her death. Adams suggests that, although he may simply have been too shy to express his feelings fully, Balfour may also have encouraged tales of his youthful tragedy as a convenient cover for his disinclination to marry; the matter cannot be conclusively proven.

In later years mediums claimed to pass on messages from hersee the " Cross-Correspondences".

Balfour remained a lifelong bachelor. Margot Tennant

Emma Margaret Asquith, Countess of Oxford and Asquith (' Tennant; 2 February 1864 – 28 July 1945), known as Margot Asquith, was a British socialite, author. She was married to H. H. Asquith, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, from 1894 ...

(later Margot Asquith) wished to marry him, but Balfour said: "No, that is not so. I rather think of having a career of my own." His household was maintained by his unmarried sister, Alice. In middle age, Balfour had a 40-year friendship with Mary Charteris (née Wyndham), Lady Elcho, later Countess of Wemyss and March.

Although one biographer writes that "it is difficult to say how far the relationship went", her letters suggest they may have become lovers in 1887 and may have engaged in sado-masochism

Sadomasochism ( ) is the giving and receiving of pleasure from acts involving the receipt or infliction of pain or humiliation. Practitioners of sadomasochism may seek sexual pleasure from their acts. While the terms sadist and masochist refer ...

, a claim echoed by A. N. Wilson

Andrew Norman Wilson (born 27 October 1950)"A. N. Wilson"

''Encyclopædia Britannica''.

. Another biographer believes they had "no direct physical relationship", although he dismisses as "unlikely" suggestions that Balfour was homosexual, or, in view of a time during the ''Encyclopædia Britannica''.

Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sou ...

when he was seen as he replied to a message while drying himself after his bath, Lord Beaverbrook

William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook (25 May 1879 – 9 June 1964), generally known as Lord Beaverbrook, was a Canadian-British newspaper publisher and backstage politician who was an influential figure in British media and politics o ...

's claim that he was "a hermaphrodite" whom no-one saw naked.

Balfour was a leading member of the social and intellectual group The Souls

The Souls was a small loosely-knit but distinctive elite social and intellectual group in the United Kingdom from 1885 to the turn of the century. Many of the most distinguished British politicians and intellectuals of the time were members. Th ...

.

Early career

In 1874 Balfour was elected

In 1874 Balfour was elected Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

Member of Parliament (MP) for Hertford

Hertford ( ) is the county town of Hertfordshire, England, and is also a civil parish in the East Hertfordshire district of the county. The parish had a population of 26,783 at the 2011 census.

The town grew around a ford on the River Lea, ne ...

until 1885. From 1885 to 1906 he served as the Member of Parliament for Manchester East. In spring 1878, he became private secretary

A private secretary (PS) is a civil servant in a governmental department or ministry, responsible to a secretary of state or minister; or a public servant in a royal household, responsible to a member of the royal family.

The role exists in t ...

to his uncle Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

. He accompanied Salisbury (then foreign secretary) to the Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a diplomatic conference to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which had been won by Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Represented at th ...

and gained his first experience in international politics in connection with the settlement of the Russo-Turkish conflict. At the same time he became known in the world of letters; the academic subtlety and literary achievement of his ''Defence of Philosophic Doubt'' (1879) suggested he might make a reputation as a philosopher.

Balfour divided his time between politics and academic pursuits. Biographer Sydney Zebel suggested that Balfour continued to appear an amateur or dabbler in public affairs, devoid of ambition and indifferent to policy issues. However, in fact he actually made a dramatic transition to a deeply involved politician. His assets, according to Zebel, included a strong ambition that he kept hidden, shrewd political judgment, a knack for negotiation, a taste for intrigue, and care to avoid factionalism. Most importantly, he deepened his close ties with his uncle Lord Salisbury. He also maintained cordial relationships with Disraeli, Gladstone and other national leaders.

Released from his duties as private secretary by the 1880 general election, he began to take more part in parliamentary affairs. He was for a time politically associated with Lord Randolph Churchill

Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill (13 February 1849 – 24 January 1895) was a British statesman. Churchill was a Tory radical and coined the term 'Tory democracy'. He inspired a generation of party managers, created the National Union of ...

, Sir Henry Drummond Wolff and John Gorst. This quartet became known as the "Fourth Party

The Fourth Party was an informal label given to four British MPs, Lord Randolph Churchill, Henry Drummond Wolff, John Gorst and Arthur Balfour, who gained national attention by acting together in the 1880–1885 parliament. They attacked wha ...

" and gained notoriety for leader Lord Randolph Churchill's free criticism of Sir Stafford Northcote

Stafford Henry Northcote, 1st Earl of Iddesleigh (27 October 1818 – 12 January 1887), known as Sir Stafford Northcote, Bt from 1851 to 1885, was a British Conservative politician. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer between 1874 and 18 ...

, Lord Cross and other prominent members of the Conservative "old gang".

Service in Lord Salisbury's governments

Irish Secretary

In 1885, Lord Salisbury appointed BalfourPresident of the Local Government Board The President of the Local Government Board was a ministerial post, frequently a Cabinet position, in the United Kingdom, established in 1871. The Local Government Board itself was established in 1871 and took over supervisory functions from the Bo ...

; the following year he became Secretary for Scotland

The secretary of state for Scotland ( gd, Rùnaire Stàite na h-Alba; sco, Secretar o State fir Scotland), also referred to as the Scottish secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom

ga, Rialtas a Shoi ...

with a seat in the cabinet. These offices, while offering few opportunities for distinction, were an apprenticeship. In early 1887, Sir Michael Hicks Beach, the Chief Secretary for Ireland

The Chief Secretary for Ireland was a key political office in the British administration in Ireland. Nominally subordinate to the Lord Lieutenant, and officially the "Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant", from the early 19th century un ...

, resigned because of illness and Salisbury appointed his nephew in his place. The selection was much criticized. It was received with contemptuous ridicule by the Irish Nationalists

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cu ...

, for none suspected Balfour's immense strength of will, his debating power, his ability in attack and his still greater capacity to disregard criticism. Balfour surprised critics by ruthless enforcement of the Crimes Act

{{Use dmy dates, date=April 2022

Crimes Act (with its variations) is a stock short title used for legislation in Australia, New Zealand and the United States, relating to the criminal law (including both substantive and procedural aspects of that l ...

. The Mitchelstown Massacre

Mitchelstown () is a town in County Cork, Ireland with a population of approximately 3,740. Mitchelstown is situated in the valley to the south of the Galtee Mountains, 12 km south-west of the Mitchelstown Caves, 28 km from Cahir, 50& ...

occurred on 9 September 1887, when Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, Constáblacht Ríoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

(RIC) members fired at a crowd protesting against the conviction under the Act of MP William O'Brien

William O'Brien (2 October 1852 – 25 February 1928) was an Irish nationalist, journalist, agrarian agitator, social revolutionary, politician, party leader, newspaper publisher, author and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of ...

and another man. Three were killed by the RIC's gunfire. When Balfour defended the RIC in the Commons, O'Brien dubbed him "Bloody Balfour". His steady administration did much to dispel his reputation as a political lightweight.

In Parliament he resisted overtures to the Irish Parliamentary Party

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP; commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party) was formed in 1874 by Isaac Butt, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish national ...

on Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

, which he saw as an expression of superficial or false Irish nationalism. Allied with Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the Cons ...

's Liberal Unionist

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political ...

s, he encouraged Unionist activism in Ireland. Balfour also helped the poor by creating the Congested Districts Board for Ireland

The Congested Districts Board for Ireland was established by The Rt. Hon. A.J. Balfour, P.C., M.P., the Chief Secretary, in 1891 to alleviate poverty and congested living conditions in the west and parts of the northwest of Ireland.

William ...

in 1890. Balfour downplayed the factor of Irish nationalism, arguing that the real issues were economic. Regarding ownership and control of the land, he believed that once violence was suppressed and land was sold to the tenants, Irish nationalism would no longer threaten the unity of the United Kingdom. The slogan "to kill home rule with kindness" characterized Balfour's new policy toward Ireland. The Liberals had begun land sales to Irish tenants with the Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881

The Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881 (44 & 45 Vict. c. 49) was the second Irish land act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1881.

Background

The Liberal government of William Ewart Gladstone had previously passed the Landlord and Ten ...

and this was expanded by the Conservatives in the land purchase scheme of 1885. However the depression in agriculture kept prices low. Balfour's solution was to keep selling land and in 1887 lowering rents to match the lower prices, and protected more tenants against eviction by their landlords. Balfour greatly expanded the land sales. They culminated in the final Unionist land purchase programme of 1903, when Balfour was prime minister and George Wyndham

George Wyndham, PC (29 August 1863 – 8 June 1913) was a British Conservative politician, statesman, man of letters, and one of The Souls.

Background and education

Wyndham was the elder son of the Honourable Percy Wyndham, third son of Ge ...

was the Irish secretary. It encouraged landlords the sell by means of a 12% cash bonus. Tenants were encouraged to buy with a low interest rate, and payments drawn out over 68 years. In 1909, Liberal legislation required compulsory sales in certain cases. As the landlords sold out, they relocated to Britain, giving up their political power in Ireland. Tensions in the countryside dramatically declined as some 200,000 peasant proprietors owned about half the land in Ireland. After 1890 violence declined sharply, and as Balfour had hoped, Irish nationalism was a relatively minor factor. The situation suddenly was transformed when the Easter rebellion of 1916 radicalised Ireland.

Leadership roles

In 1886–1892 he became one of the most effective public speakers of the age. Impressive in matter rather than delivery, his speeches were logical and convincing, and delighted an ever-wider audience. On the death ofW. H. Smith

WHSmith (also written WH Smith, and known colloquially as Smith's and formerly as W. H. Smith & Son) is a British retailer, headquartered in Swindon, England, which operates a chain of high street, railway station, airport, port, hospital and ...

in 1891, Balfour became First Lord of the Treasury

The first lord of the Treasury is the head of the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury exercising the ancient office of Lord High Treasurer in the United Kingdom, and is by convention also the prime minister. This office is not equivalent to the ...

the last in British history not to have been concurrently prime minister as welland Leader of the House of Commons

The leader of the House of Commons is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom whose main role is organising government business in the House of Commons. The leader is generally a member or attendee of the cabinet of the ...

. After the fall of the government in 1892 he spent three years in opposition. When the Conservatives returned to power, in coalition with the Liberal Unionists, in 1895, Balfour again became Leader of the House and First Lord of the Treasury. His management of the abortive education proposals of 1896 showed a disinclination for the drudgery of parliamentary management, yet he saw the passage of a bill providing Ireland with improved local government under the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898

The Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 (61 & 62 Vict. c. 37) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that established a system of local government in Ireland similar to that already created for England, ...

and joined in debates on foreign and domestic questions between 1895 and 1900.

During the illness of Lord Salisbury in 1898, and again in Salisbury's absence abroad, Balfour was in charge of the Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* Unit ...

, and he conducted negotiations with Russia on the question of railways in North China. As a member of the cabinet responsible for the Transvaal negotiations in 1899, he bore his share of controversy and, when the war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

began disastrously, he was first to realise the need to use the country's full military strength. His leadership of the House was marked by firmness in the suppression of obstruction, yet there was a slight revival of the criticisms of 1896.

Prime minister

With Lord Salisbury's resignation on 11 July 1902, Balfour succeeded him as prime minister, with the approval of all the Unionist party. The new prime minister came into power practically at the same moment as thecoronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra

The coronation of Edward VII and his wife, Alexandra, as King and Queen of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and as Emperor and Empress of India took place at Westminster Abbey, London, on 9 August 1902. Originally scheduled for 2 ...

and the end of the South African War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

. The Liberal party was still disorganised over the Boers.

In foreign affairs, Balfour and his foreign secretary, Lord Lansdowne, improved relations with France, culminating in the Entente Cordiale

The Entente Cordiale (; ) comprised a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic which saw a significant improvement in Anglo-French relations. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial de ...

of 1904. The period also saw the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

, when Britain, an ally of the Japanese, came close to war with Russia after the Dogger Bank incident

The Dogger Bank incident (also known as the North Sea Incident, the Russian Outrage or the Incident of Hull) occurred on the night of 21/22 October 1904, when the Baltic Fleet of the Imperial Russian Navy mistook a British trawler fleet fro ...

. On the whole, Balfour left the conduct of foreign policy to Lansdowne, being busy himself with domestic problems.

Balfour, who had known Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( he, חיים עזריאל ויצמן ', russian: Хаим Евзорович Вейцман, ''Khaim Evzorovich Veytsman''; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born biochemist, Zionist leader and Israel ...

since 1906, opposed Russian mistreatment of Jews and increasingly supported Zionism as a programme for European Jews to settle in Palestine. However, in 1905 he supported the Aliens Act 1905

The Aliens Act 1905 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.Moving Here The Act introduced immigration controls and registration for the first time, and gave the Home Secretary overall responsibility for ma ...

, one of whose main objectives was to control and restrict Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe.

The budget was certain to show a surplus and taxation could be remitted. Yet as events proved, it was the budget that would sow dissension, override other legislative concerns and signal a new political movement. Charles Thomson Ritchie

Charles Thomson Ritchie, 1st Baron Ritchie of Dundee, (19 November 1838 – 9 January 1906) was a British businessman and Conservative politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1874 until 1905 when he was raised to the peerage. He se ...

's remission of the shilling import-duty on corn led to Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the Cons ...

's crusade in favour of tariff reform. These were taxes on imported goods with trade preference

A trade preference is a preference by one country for buying goods from some other country more than from other countries. It grants special support to one country over another. It is the opposite of a trade prohibition.

For example, the Agreemen ...

given to the Empire, to protect British industry from competition, strengthen the Empire in the face of growing German and American economic power, and provide revenue, other than raising taxes, for the social welfare legislation. As the session proceeded, the rift grew in the Unionist ranks. Tariff reform was popular with Unionist supporters, but the threat of higher prices for food imports made the policy an electoral albatross. Hoping to split the difference between the free traders and tariff reformers in his cabinet and party, Balfour favoured retaliatory tariffs to punish others who had tariffs against the British, in the hope of encouraging global free trade.

This was not sufficient for either the free traders or the extreme tariff reformers in government. With Balfour's agreement, Chamberlain resigned from the Cabinet in late 1903 to campaign for tariff reform. At the same time, Balfour tried to balance the two factions by accepting the resignation of three free-trading ministers, including Chancellor Ritchie, but the almost simultaneous resignation of the free-trader Duke of Devonshire (who as Lord Hartington had been the Liberal Unionist leader of the 1880s) left Balfour's Cabinet weak. By 1905 few Unionist MPs were still free traders (Winston Churchill crossed to the Liberals in 1904 when threatened with deselection at Oldham), but Balfour's act had drained his authority within the government.

Balfour resigned as prime minister in December 1905, hoping the Liberal leader Campbell-Bannerman would be unable to form a strong government. This was dashed when Campbell-Bannerman faced down an attempt ("The Relugas Compact

The Relugas Compact was the plot hatched in 1905 by British Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party politicians H. H. Asquith, Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon, Sir Edward Grey, and Richard Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane, R. B. Haldane to force ...

") to "kick him upstairs" to the House of Lords. The Conservatives were defeated by the Liberals at the general election the following January (in terms of MPs, a Liberal landslide), with Balfour losing his seat at Manchester East to Thomas Gardner Horridge

Sir Thomas Gardner Horridge (12 October 1857 – 25 July 1938) was a British barrister and Liberal Party politician who became a judge of the High Court of England and Wales.

He was the only son of John Horridge, chemist, of Tonge with Haulgh, ...

, a solicitor and King's Counsel

In the United Kingdom and in some Commonwealth countries, a King's Counsel ( post-nominal initials KC) during the reign of a king, or Queen's Counsel (post-nominal initials QC) during the reign of a queen, is a lawyer (usually a barrister or ...

. Only 157 Conservatives were returned to the Commons, at least two-thirds followers of Chamberlain, who chaired the Conservative MPs until Balfour won a safe seat in the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

.

Achievements and mistakes

According to historianRobert Ensor

Sir Robert Charles Kirkwood Ensor (16 October 1877 – 4 December 1958) was a British writer, poet, journalist, liberal intellectual and historian. He is best known for ''England: 1870-1914'' (1936), a volume in the ''Oxford History of England'' ...

, writing in 1936, Balfour can be credited with achievement in five major areas:

# The Education Act 1902

The Education Act 1902 ( 2 Edw. 7 c. 42), also known as the Balfour Act, was a highly controversial Act of Parliament that set the pattern of elementary education in England and Wales for four decades. It was brought to Parliament by a Conservat ...

(and a similar measure for London in 1903);

# The Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903

The Land Acts (officially Land Law (Ireland) Acts) were a series of measures to deal with the question of tenancy contracts and peasant proprietorship of land in Ireland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Five such acts were introduced by ...

, which bought out the Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

land owners;

# The Licensing Act 1904;

# In military policy, the creation of the Committee of Imperial Defence

The Committee of Imperial Defence was an important ''ad hoc'' part of the Government of the United Kingdom and the British Empire from just after the Second Boer War until the start of the Second World War. It was responsible for research, and som ...

(1904) and support for Sir John Fisher's naval reforms.

# In foreign policy, the Anglo-French Convention (1904), which formed the basis of the Entente with France.

The Education Act lasted four decades and eventually was highly praised. Eugene Rasor states, "Balfour was credited and much praised from many perspectives with the success f the 1902 education act

F, or f, is the sixth letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounced ), and the plural is ''efs''.

Hist ...

His commitment to education was fundamental and strong." At the time it hurt Balfour because the Liberal party used it to rally their Noncomformist supporters. Ensor said the Act ranked:

For most of the 19th century, the very powerful political and economic position of the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second ...

(Anglican) landowners blocked the political aspirations of Irish nationalists, who by 1900 included both Catholic and Presbyterian elements. Balfour's solution was to buy them out, not by compulsion, but by offering the owners a full immediate payment and a 12% bonus on the sales price. The British government purchased 13 million acres (53,000 km2) by 1920, and sold farms to the tenants at low payments spread over seven decades. It would cost money, but all sides proved amenable. Starting in 1923 the Irish government bought out most of the remaining landowners, and in 1933 diverted payments being made to the British treasury and used them for local improvements.

Balfour's introduction of Chinese coolie labour in South Africa enabled the Liberals to counterattack, charging that his measures amounted to "Chinese slavery". Likerwise Liberals energized the Nonconformists when they attacked Balfour's Licensing Act 1904 which paid pub owners to close down. In the long run it did reduce the great oversupply of pubs, while in the short run Balfour's party was hurt.

Balfour failed to solve his greatest political challengethe debate over tariffs that ripped his party apart. Chamberlain proposed to turn the Empire into a closed trade bloc

A trade bloc is a type of intergovernmental agreement, often part of a regional intergovernmental organization, where barriers to trade (tariffs and others) are reduced or eliminated among the participating states.

Trade blocs can be stand-alon ...

protected by high tariffs against imports from Germany and the United States. He argued that tariff reform would revive a flagging British economy, strengthen imperial ties with the dominions and the colonies, and produce a positive programme that would facilitate reelection. He was vehemently opposed by Conservative free traders who denounced the proposal as economically fallacious, and open to the charge of raising food prices in Britain. Balfour tried to forestall disruption by removing key ministers on each side, and offering a much narrower tariff programme. It was ingenious, but both sides rejected any compromise, and his party's chances for reelection were ruined.

Balfour may have been personally sympathetic to extending suffrage, with his brother Gerald, Conservative MP for Leeds Central married to women's suffrage activist Constance Lytton

Lady Constance Georgina Bulwer-Lytton (12 February 1869 – 2 May 1923), usually known as Constance Lytton, was an influential British suffragette activist, writer, speaker and campaigner for prison reform, votes for women, and birth control. ...

's sister Betty. But he accepted the strength of the political opposition to women's suffrage, as shown in correspondence with Christabel Pankhurst

Dame Christabel Harriette Pankhurst, (; 22 September 1880 – 13 February 1958) was a British suffragette born in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bord ...

, a leader of the WSPU

The Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) was a women-only political movement and leading militant organisation campaigning for women's suffrage in the United Kingdom from 1903 to 1918. Known from 1906 as the suffragettes, its membership and ...

. Balfour argued that he was "not convinced the majority of women actually wanted the vote", in 1907. A rebuttal which meant extending the activist campaign for women's rights. He was reminded by Lytton of a speech he made in 1892, namely that this question "will arise again, menacing and ripe for resolution", she asked him to meet WSPU leader, Christabel Pankhurst, after a series of hunger strikes and suffering by imprisoned suffragettes in 1907. Balfour refused on the grounds of her militancy. Christabel pleaded direct to meet Balfour as Conservative party leader, on their policy manifesto for the General Election of 1909, but he refused again as women's suffrage was "not a party question and his colleagues were divided on the matter". She tried and failed again to get his open support in parliament for women's cause in the 1910 private member's Conciliation Bill

Conciliation bills were proposed legislation which would extend the right of women to vote in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland to just over a million wealthy, property-owning women. After the January 1910 election, an all-party Con ...

. He voted for the bill in the end but not for its progress to the Grand Committee, preventing it becoming law, and extending the activist campaigns as a result again. The following year Lytton and Annie Kenney in person after another reading of the Bill, but again it was not prioritised as government business. His sister-in-law Lady Betty Balfour spoke to Churchill that her brother was to speak for this policy, and also met the Prime Minister in a 1911 delegation of the women's movements representing the Conservative and Unionist Women's Franchise Association. But it was not until 1918 that (some) women were given the right to vote in elections in the United Kingdom, despite a forty-year campaign.

Historians generally praised Balfour's achievements in military and foreign policy. stress the importance of the Anglo‐French Entente of 1904, and the establishment of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Rasor points to twelve historians who have examined his key role in naval and military reforms. However, there was little political payback at the time. The local Conservative campaigns in 1906 focused mostly on a few domestic issues. Balfour gave strong support for Jackie Fisher's naval reforms.

Balfour created and chaired the Committee of Imperial Defence

The Committee of Imperial Defence was an important ''ad hoc'' part of the Government of the United Kingdom and the British Empire from just after the Second Boer War until the start of the Second World War. It was responsible for research, and som ...

, which provided better long-term coordinated planning between the Army and Navy. Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly ...

said Britain would have been unprepared for the World War without his Committee of Imperial Defence. He wrote, "It is impossible to overrate the services thus rendered by Balfour to the Country and Empire.... ithout the CIDvictory would have been impossible." Historians also praised the Anglo-French Convention (1904), which formed the basis of the Entente Cordiale

The Entente Cordiale (; ) comprised a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic which saw a significant improvement in Anglo-French relations. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial de ...

with France that proved decisive in 1914.

Later career

After the general election of 1906 Balfour remained party leader, his position strengthened by Joseph Chamberlain's absence from the House of Commons after his stroke in July 1906, but he was unable to make much headway against the huge Liberal majority in the Commons. An early attempt to score a debating triumph over the government, made in Balfour's usual abstruse, theoretical style, saw Campbell-Bannerman respond with: "Enough of this foolery," to the delight of his supporters. Balfour made the controversial decision, with Lord Lansdowne, to use the heavily Unionist

After the general election of 1906 Balfour remained party leader, his position strengthened by Joseph Chamberlain's absence from the House of Commons after his stroke in July 1906, but he was unable to make much headway against the huge Liberal majority in the Commons. An early attempt to score a debating triumph over the government, made in Balfour's usual abstruse, theoretical style, saw Campbell-Bannerman respond with: "Enough of this foolery," to the delight of his supporters. Balfour made the controversial decision, with Lord Lansdowne, to use the heavily Unionist House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

as a check on the political programme and legislation of the Liberal party in the Commons. Legislation was vetoed or altered by amendments between 1906 and 1909, leading David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

to remark that the Lords was "the right hon. Gentleman's poodle. It fetches and carries for him. It barks for him. It bites anybody that he sets it on to. And we are told that this is a great revising Chamber, the safeguard of liberty in the country." The issue was forced by the Liberals with Lloyd George's People's Budget

The 1909/1910 People's Budget was a proposal of the Liberal government that introduced unprecedented taxes on the lands and incomes of Britain's wealthy to fund new social welfare programmes. It passed the House of Commons in 1909 but was bloc ...

, provoking the constitutional crisis that led to the Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5 c. 13) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two Houses of Parlia ...

, which limited the Lords to delaying bills for up to two years. After the Unionists lost the general elections of 1910 (despite softening the tariff reform policy with Balfour's promise of a referendum on food taxes), the Unionist peers split to allow the Parliament Act to pass the House of Lords, to prevent mass creation of Liberal peers by the new King, George V. The exhausted Balfour resigned as party leader after the crisis, and was succeeded in late 1911 by Bonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law ( ; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now a ...

.

Balfour remained important in the party, however, and when the Unionists joined Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of ...

's coalition government in May 1915, Balfour succeeded Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

. When Asquith's government collapsed in December 1916, Balfour, who seemed a potential successor to the premiership, became foreign secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Seen as ...

in Lloyd George's new administration, but not in the small War Cabinet, and was frequently left out of inner workings of government. Balfour's service as foreign secretary was notable for the Balfour Mission

The Balfour Mission, also referred to as the Balfour Visit, was a formal diplomatic visit to the United States by the British Government during World War I, shortly after the United States declaration of war on Germany (1917).

The mission's purpo ...

, a crucial alliance-building visit to the US in April 1917, and the Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

of 1917, a letter to Lord Rothschild

Baron Rothschild, of Tring in the County of Hertfordshire, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1885 for Sir Nathan Rothschild, 2nd Baronet, a member of the Rothschild banking family. He was the first Jewish mem ...

affirming the government's support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

, then part of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

.

Balfour resigned as foreign secretary following the Versailles Conference

The Palace of Versailles ( ; french: Château de Versailles ) is a former royal residence built by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, about west of Paris, France. The palace is owned by the French Republic and since 1995 has been managed, u ...

in 1919, but continued in the government (and the Cabinet after normal peacetime political arrangements resumed) as Lord President of the Council

The lord president of the Council is the presiding officer of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom and the fourth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State, ranking below the Lord High Treasurer but above the ...

. In 1921–22 he represented the British Empire at the Washington Naval Conference

The Washington Naval Conference was a disarmament conference called by the United States and held in Washington, DC from November 12, 1921 to February 6, 1922. It was conducted outside the auspices of the League of Nations. It was attended by nine ...

and during summer 1922 stood in for the foreign secretary, Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), styled Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and then Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman ...

, who was ill. He put forward a proposal for the international settlement of war debts and reparations (the Balfour Note), but it was not accepted.

On 5 May 1922, Balfour was created Earl of Balfour

Earl of Balfour is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1922 for Conservative politician Arthur Balfour, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905 and Foreign Secretary from 1916 to 1919.

The earldom wa ...

and Viscount Traprain, of

Whittingehame

Whittingehame is a parish with a small village in East Lothian, Scotland, about halfway between Haddington and Dunbar, and near East Linton. The area is on the slopes of the Lammermuir Hills. Whittingehame Tower dates from the 15th century an ...

, in the county of Haddington. In October 1922 he, with most of the Conservative leadership, resigned with Lloyd George's government following the Carlton Club meeting

The Carlton Club meeting, on 19 October 1922, was a formal meeting of Members of Parliament who belonged to the Conservative Party, called to discuss whether the party should remain in government in coalition with a section of the Liberal Party ...

, a Conservative back-bench revolt against continuance of the coalition. Bonar Law became prime minister. Like many Coalition leaders, he did not hold office in the Conservative governments of 1922–1924, but as an elder statesman, he was consulted by the King in the choice of Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

as Bonar Law's successor as Conservative leader in May 1923. His advice was strongly in favour of Baldwin, ostensibly due to Baldwin's being an MP but in reality motivated by his personal dislike of Curzon. Later that evening, he met a mutual friend who asked 'Will dear George be chosen?' to which he replied with 'feline Balfourian satisfaction,' 'No, dear George will not.' His hostess replied, 'Oh, I am so sorry to hear that. He will be terribly disappointed.' Balfour retorted, 'Oh, I don't know. After all, even if he has lost the hope of glory he still possesses the means of Grace

The means of grace in Christian theology are those things (the ''means'') through which God gives grace. Just what this grace entails is interpreted in various ways: generally speaking, some see it as God blessing humankind so as to sustain and emp ...

.'

Balfour was not initially included in Baldwin's second government in 1924, but in 1925, he returned to the Cabinet, in place of the late Lord Curzon as Lord President of the Council

The lord president of the Council is the presiding officer of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom and the fourth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State, ranking below the Lord High Treasurer but above the ...

, until the government ended in 1929. With 28 years of government service, Balfour had one of the longest ministerial careers in modern British politics, second only to Winston Churchill .

Last years

Lord Balfour had generally good health until 1928 and remained until then a regular tennis player. Four years previously he had been the first president of the International Lawn Tennis Club of Great Britain. At the end of 1928, most of his teeth were removed and he suffered the unremitting circulatory trouble which ended his life. Before that, he had suffered occasionalphlebitis

Phlebitis (or Venitis) is inflammation of a vein, usually in the legs. It most commonly occurs in superficial veins. Phlebitis often occurs in conjunction with thrombosis and is then called thrombophlebitis or superficial thrombophlebitis. Unlike ...

and, by late 1929, he was immobilised by it. Balfour died at his brother Gerald's home, Fishers Hill House in Hook Heath, Woking, on 19 March 1930. At his request a public funeral was declined, and he was buried on 22 March beside members of his family at Whittingehame

Whittingehame is a parish with a small village in East Lothian, Scotland, about halfway between Haddington and Dunbar, and near East Linton. The area is on the slopes of the Lammermuir Hills. Whittingehame Tower dates from the 15th century an ...

in a Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

service although he also belonged to the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

. By special remainder

In property law of the United Kingdom and the United States and other common law countries, a remainder is a future interest given to a person (who is referred to as the transferee or remainderman) that is capable of becoming possessory upon the n ...

, his title passed to his brother Gerald.

His obituaries in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'', ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' and the '' Daily Herald'' did not mention the declaration for which he is most famous outside Britain.

Personality

Early in Balfour's career he was thought to be merely amusing himself with politics, and it was regarded as doubtful whether his health could withstand the severity of English winters. He was considered a dilettante by his colleagues; regardless, Lord Salisbury gave increasingly powerful posts in his government to his nephew.Beatrice Webb

Martha Beatrice Webb, Baroness Passfield, (née Potter; 22 January 1858 – 30 April 1943) was an English sociologist, economist, socialist, labour historian and social reformer. It was Webb who coined the term ''collective bargaining''. She ...

wrote in her diary:

Balfour developed a manner known to friends as the ''Balfourian manner''. Edward Harold Begbie

Edward Harold Begbie (1871 – 8 October 1929), also known as Harold Begbie, was an English journalist and the author of nearly 50 books and poems. Besides studies of the Christian religion, he wrote numerous other books, including political sa ...

, a journalist, attacked him for what Begbie considered Balfour's self-obsession:

However, Graham Goodlad argued to the contrary:

Churchill compared Balfour to H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

: "The difference between Balfour and Asquith is that Arthur is wicked and moral, while Asquith is good and immoral." Balfour said of himself, "I am more or less happy when being praised, not very comfortable when being abused, but I have moments of uneasiness when being explained."

Balfour was interested in the study of dialect

The term dialect (from Latin , , from the Ancient Greek word , 'discourse', from , 'through' and , 'I speak') can refer to either of two distinctly different types of Linguistics, linguistic phenomena:

One usage refers to a variety (linguisti ...

s and donated money to Joseph Wright Joseph Wright may refer to:

*Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797), English painter

*Joseph Wright (American painter) (1756–1793), American portraitist

*Joseph Wright (fl. 1837/1845), whose company, Messrs. Joseph Wright and Sons, became the Metro ...

's work on ''The English Dialect Dictionary

''The English Dialect Dictionary'' (''EDD'') is the most comprehensive dictionary of English dialects ever published, compiled by the Yorkshire dialectologist Joseph Wright (1855–1930), with strong support by a team and his wife Elizabeth Mar ...

''. Wright wrote in the preface to the first volume that the project would have been "in vain" had he not received the donation from Balfour.

Arthur Balfour was a fan of football and supported Manchester City F.C.

Manchester City Football Club are an England, English association football, football club based in Manchester that competes in the Premier League, the English football league system, top flight of Football in England, English football. Fo ...

Writings and academic achievements

As a philosopher, Balfour formulated the basis for theevolutionary argument against naturalism

The evolutionary argument against naturalism (EAAN) is a philosophical argument asserting a problem with believing both evolution and philosophical naturalism simultaneously. The argument was first proposed by Alvin Plantinga in 1993 and "raises is ...

. Balfour argued the Darwinian premise of selection for reproductive fitness cast doubt on scientific naturalism, because human cognitive facilities that would accurately perceive truth could be less advantageous than adaptation for evolutionarily useful illusions.

As he says:

He was a member of the Society for Psychical Research

The Society for Psychical Research (SPR) is a nonprofit organisation in the United Kingdom. Its stated purpose is to understand events and abilities commonly described as psychic or paranormal. It describes itself as the "first society to condu ...

, a society studying psychic

A psychic is a person who claims to use extrasensory perception (ESP) to identify information hidden from the normal senses, particularly involving telepathy or clairvoyance, or who performs acts that are apparently inexplicable by natural laws, ...

and paranormal phenomena

Paranormal events are purported phenomena described in popular culture, Folk culture, folk, and other non-scientific bodies of knowledge, whose existence within these contexts is described as being beyond the scope of normal scientific under ...

, and was its president from 1892 to 1894. In 1914, he delivered the Gifford Lectures

The Gifford Lectures () are an annual series of lectures which were established in 1887 by the will of Adam Gifford, Lord Gifford. Their purpose is to "promote and diffuse the study of natural theology in the widest sense of the term – in o ...

at the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

, which formed the basis for his book ''Theism and Humanism'' (1915).

Artistic

After the First World War, when there was controversy over the style of headstone proposed for use on British war graves being taken on by theImperial War Graves Commission

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) is an intergovernmental organisation of six independent member states whose principal function is to mark, record and maintain the graves and places of commemoration of Commonwealth of Nations mil ...

, Balfour submitted a design for a cruciform headstone. At an exhibition in August 1919, it drew many criticisms; the commission's principal architect, Sir John Burnet said that Balfour's cross, if used in large numbers in cemeteries, would create a criss-cross visual effect, destroying any sense of "restful diginity"; Edwin Lutyens

Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens ( ; 29 March 1869 – 1 January 1944) was an English architect known for imaginatively adapting traditional architectural styles to the requirements of his era. He designed many English country houses, war memori ...

called it "extraordinarily ugly", and its shape was variously described as resembling a shooting target or bottle. His design was not accepted but the Commission offered him a second chance to submit another design which he did not take up, having been refused once. After a further exhibition in the House of Commons, the "Balfour cross" was ultimately rejected in favour of the standard headstone the Commission permanently adopted because the latter offered more space for inscriptions and service emblems.

Popular culture

Balfour occasionally appears in popular culture. * Balfour was the subject of two parody novels based onAlice in Wonderland

''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (commonly ''Alice in Wonderland'') is an 1865 English novel by Lewis Carroll. It details the story of a young girl named Alice who falls through a rabbit hole into a fantasy world of anthropomorphic creatur ...

, ''Clara in Blunderland

''Clara in Blunderland'' is a novel by Caroline Lewis (a pseudonym for Edward Harold Begbie, J. Stafford Ransome, and Michael Henry Temple), written in 1902 and published by William Heinemann of London. It is a political parody of Lewis Carro ...

'' (1902) and ''Lost in Blunderland

''Lost in Blunderland: The Further Adventures of Clara'' is a novel by Caroline Lewis (pseudonym for Edward Harold Begbie, J. Stafford Ransome, and Michael Henry Temple), written in 1903 and published by William Heinemann of London. It is a po ...

'' (1903), which appeared under the pseudonym Caroline Lewis; one of the co-authors was Harold Begbie

Edward Harold Begbie (1871 – 8 October 1929), also known as Harold Begbie, was an English journalist and the author of nearly 50 books and poems. Besides studies of the Christian religion, he wrote numerous other books, including political sa ...